Abstract

Objective

To assess the association between energy drink use and hazardous alcohol use among a national sample of adolescents and young adults.

Study design

Cross-sectional analysis of 3,342 youth aged 15-23 years recruited for a national survey about media and alcohol use. Energy drink use was defined as recent use or ever mixed-use with alcohol. Outcomes were ever alcohol use and three hazardous alcohol use outcomes measured with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): ever consuming 6 or more drinks at once (6+ binge drinking) and clinical criteria for hazardous alcohol use as defined for adults (8+AUDIT) and for adolescents (4+AUDIT).

Results

Among 15-17 year olds (n=1,508), 13.3% recently consumed an energy drink, 9.7% ever consumed an energy drink mixed with alcohol, and 47.1% ever drank alcohol. Recent energy drink use predicted ever alcohol use among 15-17 years olds only (OR: 2.58; 95% CI: 1.77-3.77). Of these 15-17 year olds, 17% met the 6+ binge drinking criteria, 7.2% met the 8+AUDIT criteria, and 16.0% met the 4+AUDIT criteria. Rates of energy drink use and all alcohol use outcomes increased with age. Ever mixed-use with alcohol predicted 6+ binge drinking (OR 4.69; 95% CI: 3.70-5.94), 8+AUDIT (OR 3.25; 95% CI: 2.51-4.21), and 4+AUDIT (OR 4.15; 95% CI: 3.27-5.25) criteria in adjusted models among all participants, with no evidence of modification by age.

Conclusions

Positive associations between energy drink use and hazardous alcohol use behaviors are not limited to youth in college settings.

Underage drinking is a major public health problem in the U.S.1 More than 27% of 12-20 year olds drink alcohol in any month, averaging 4.9 drinks per session.2 Binge drinking increases the risk of acute and chronic alcohol-related problems1 including injury, risky sexual behaviors, and driving while intoxicated.1 Those who begin drinking alcohol before the age of 18 are more likely to develop symptoms of alcohol abuse and dependence as an adult than their peers who abstain,3,4 associations that are largely mediated by increased rates of binge drinking.3,5 In 2007 the U.S. Surgeon General's Office issued a Call to Action to reduce underage drinking.1 However, emergency room visits for alcohol-related injuries among 12-20 year olds have been steady since 2007, with estimates from 2009 documenting nearly 200,000 visits.6

Energy drinks are caffeinated beverages, shots, or drops that contain a mix of other energy promoting ingredients (eg, taurine, ginseng, guarana, B-vitamins) and frequently sugar. Caffeine contents of popular energy drinks range from 70 mg per one 8-ounce serving to 200 mg per one 16-ounce serving;7 concentrations similar to that of a strong cup of coffee. Energy drinks are becoming increasingly popular among US adolescents.8-13 The American Academy of Pediatrics discourages adolescents from consuming energy drinks stating such drinks have no therapeutic benefits.15 Even as some have criticized those calls as scaremongering,16 energy drink use among adolescents deserves attention given the common practice of mixing energy drinks with alcohol among young adults.17,18

Many college students consume energy drinks mixed with alcohol19-32 often with the intent to consume excessive amounts of alcohol during one session.22,25 Energy drinks consumed with alcohol result in the user feeling less intoxicated26,33,34 although they do not lessen alcohol's effects on objective measures of impairment.33-35 Consuming energy drinks with alcohol is positively associated with binge drinking and alcohol-related aggressive behaviors, risky sexual behaviors, and the need for medical attention among college students.19-29 One study of adolescents reported a positive association between frequency of energy drink consumption and past 30-day alcohol use.10 Another reported a positive association between ever use of energy drinks mixed with alcohol and binge drinking or alcohol-related fights or injuries.12

We studied the prevalence of energy drink consumption among a national sample of U.S. adolescents and young adults, and assessed whether energy drink consumption is associated with problematic alcohol use.

Methods

Data are from a national cohort study that enrolled youth aged 15-23 years to assess media use, marketing exposures, and alcohol use.36 Participants were recruited via a random-digit dialing protocol using both landline and cell phone numbers during 2010. Households with children aged 15-23 were eligible for the study; one participant per household was selected for enrollment. Of the 60,189 households screened, 6,783 included a family member in the target age range and 3,342 (49.3%) agreed to complete the telephone survey. All U.S. states and the District of Columbia were represented in the final sample. Participants completed a computer-assisted telephone interview conducted by trained study interviewers (Westat, Rockville, MD). Participants ≥18 years gave verbal consent; parental and adolescent assent were required for participants <18. Participants could enter responses to sensitive questions using the touch-tone keypad of their phone for privacy. The Committees for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College and at Westat approved all study activities.

Assessment of energy drink use

Recent energy drink use was assessed as: “During the past seven days, how many times did you drink a can, bottle, or glass of an energy drink like Red Bull or Monster (0, 1 to 3 times in past seven days, 4 to 6 times in past seven days, 1 time per day, 2 times per day, 3 times per day, or 4 or more times per day)?” Participants were also asked about mixed-use of energy drinks with alcohol: “Have you ever consumed an energy drink with or after alcohol (yes, no, I don't drink energy drinks)?”

Alcohol use outcomes

Four alcohol use outcomes were included in this analysis: ever drinking alcohol and hazardous use of alcohol within the past year. Ever drinking alcohol was assessed as: “Have you ever had a whole drink of alcohol more than a sip or taste (yes, no)?” Participants who responded yes were further administered the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT),37 a 10-item scale (total score ranges from 0-40) assessing three domains of alcohol use and abuse: hazardous alcohol use (e.g., see 6+ binge drinking below), dependence symptoms (e.g., How often during the last year have you found that you were not able to stop drinking once you had started?), and harmful alcohol use (e.g., “Have you or someone else been injured as a result of your drinking?”). The AUDIT is a validated scale used worldwide to identify individuals with hazardous alcohol use patterns and is used to identify individuals at risk of alcohol use disorder.38 In this current study, participants were asked to recall behaviors over the past year. One item included in the AUDIT assessed binge drinking (6+ binge drinking): “How often do you consume six or more drinks on one occasion (never, less than monthly, monthly, weekly, daily or almost daily)?” Responses were dichotomized as never versus ever. Several large surveys in the U.S. including the Monitoring the Future study39 define binge drinking among adolescents as 5 or more drinks on one occasion, and even lower age- and sex-specific thresholds have been suggested based on estimated blood alcohol concentrations.40 The use of 6 or more drinks as a binge-drinking criterion is thus conservative for an adolescent population.

The AUDIT total score was used to assess the risk of alcohol use disorder. A score of 8 or more is suggested for identifying hazardous drinking behaviors among adults,38 and a score of 4 or more is suggested for identifying hazardous drinking behaviors among adolescents as young as 13.41,42 Both outcomes (8+AUDIT and 4+AUDIT, respectively) were used to assess hazardous alcohol use.

Additional Measures

Additional measures included demographic characteristics of the child (age, sex, race, ethnicity, and educational or employment status) and measures likely associated with both energy drink and alcohol use (number of friends who drink alcohol, frequency of parental/guardian consumption of alcohol). Sensation seeking was assessed with a six-item sensation seeking score (e.g., I would like to explore strange places: strongly agree, agree, disagree, strongly disagree, and don't know; Cronbach alpha = 0.72) based on the constructs Zuckerman43 and Arnett.44 Responses over the six items were combined into a one, scaled sensation seeking propensity score (range 1-4), where higher scores reflect greater propensity for sensation seeking behaviors. Previous work by our group has demonstrated that the sensation seeking propensity score has moderate predictive ability for 6+ binge drinking (area under the ROC 0.71).45

Statistical Analyses

Bivariate analyses compared the frequency of energy drink use in the past seven days and each of the four alcohol use outcomes by baseline characteristics. Multivariate logistic regression was used to fit each of the four alcohol use outcomes on energy drink use measures; models for the three hazardous alcohol use outcomes were limited to participants who reported ever drinking alcohol. Model covariates were those variables with bivariate-level of associations (p<0.10). Analyses were completed overall and stratified by age, specifically adolescents (15-17 years), underage young-adults (18-20 years), and young adults of legal drinking age (21-23 years). Statistical significance of interactions by age was assessed using likelihood ratio tests comparing two nested models with and without an age/energy drink interaction term. All analyses were completed with the R Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, version 3.0.1.46

Results

Among this sample of youth, most (45.1%) were 15-17 years old, 32.7% were 18-20 years old, and 22.1% were at least 21 years of age; 51% of the subjects were male. Most participants were White, non-Hispanic (66.6%), with 9.4% identifying as Black, non-Hispanic, 13.6% Hispanic, and 2.9% Asian. Seven percent of participants identified as another race, largely attributed to self-identifying as mixed race (n=163). Approximately one-half (52.0%) of participants were in high school, 27.4% in college or a trade school, 13.7% working, and 6.6% unemployed.

Approximately one in six participants (16.2%) had used an energy drink at least once in the past seven days (Table I), with most of those participants (n=428, 79.0%) having consumed between 1-3 energy drinks. At the bivariate level, older participants, males, those working or unemployed compared with those in school, and those with a higher propensity for sensation seeking were more likely to have recently consumed energy drinks (each p<0.001). Recent energy drink use remained significantly independently associated with older age, male sex, and higher propensity for sensation seeking in an adjusted logistic regression model that included all measures related to recent energy drink use at the bivariate level (data not shown).

Table 1.

Energy drink use in past seven days by baseline characteristics among a sample of adolescents and young adults.1

| Energy drink use in past 7 days | p-value2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| None N (%) |

Any N (%) |

||

| Overall | 2800 (83.8%) | 542 (16.2%) | -- |

| Energy drink frequency | |||

| 1-3 times in past 7 days | -- | 428 (12.8%) | -- |

| 4-6 times in past 7 days | -- | 42 (1.3%) | |

| Daily in past 7 days | -- | 47 (1.4%) | |

| More than daily in past 7 days | -- | 25 (0.7%) | |

| Age, years | |||

| 15-17 | 1308 (86.7%) | 200 (13.3%) | <0.001 |

| 18-20 | 895 (81.8%) | 199 (18.2%) | |

| 21-23 | 597 (80.7%) | 143 (19.3%) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1433 (87.4%) | 206 (12.6%) | <0.001 |

| Male | 1367 (80.3%) | 336 (19.7%) | |

| Race, ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1856 (83.4%) | 370 (16.6%) | 0.169 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 277 (88.2%) | 37 (11.8%) | |

| Asian | 79 (82.3%) | 17 (17.8%) | |

| Hispanic | 379 (83.1%) | 77 (16.9%) | |

| Other3 | 209 (83.6%) | 41 (16.4%) | |

| Education/employment status | |||

| High school student | 1493 (85.9%) | 245 (14.1%) | <0.001 |

| College or trade school student | 764 (83.4%) | 152 (16.6%) | |

| Working, non-student | 356 (77.7%) | 102 (22.3%) | |

| Unemployed, non-student | 178 (81.3%) | 41 (18.7%) | |

| Sensation seeking3 | |||

| Below median | 1381 (90.4%) | 146 (9.6%) | <0.001 |

| Above median | 1419 (78.2%) | 396 (21.8%) | |

Among N=3,342 participants who completed a telephone based survey.

p-value from Chi-Square tests for categorical measures or Student T-test for continuous measures.

Other includes American Indian/Alaska Native (N=14), Native Hawaiian / Pacific Islander (N=9), more than one race (N=163), other (N=13), or refused to answer (N=51).

Sensation seeking dichotomized at the median of 2.3, range 1-4.

Overall, 63.1% (n=2,110) of participants had ever consumed alcohol (Table II). Bivariate analyses showed that age, sensation seeking, the number of friends who drink alcohol, and the frequency of parental alcohol drinking were each positively associated with ever drinking alcohol (data not shown, all p<0.001). Rates of ever drinking alcohol were also statistically different by race and ethnicity, with rates highest among Hispanic (69.3%) and non-Hispanic White participants (63.8%; p<0.001). Alcohol use was more common among those who reported any energy drink use in the past seven days (80.1%) compared with those who did not (59.9%; p<0.001; Table II). In a logistic regression adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, number of friends who drink, parental drinking frequency, and sensation seeking, recent energy drink use remained significantly, positively associated with the likelihood of ever drinking alcohol among 15-17 year olds only (OR 2.58; 95% CI: 1.77-3.77) as judged with a likelihood ratio test comparing two nested models: one with an interaction term of age and recent energy drink use and one without such an interaction term (p=0.007).

Table 2.

Unadjusted prevalence rates for hazardous alcohol use outcomes by energy drink use in past seven days among a sample of adolescents and young adults.1,2,3

| Ever Alcohol Use N (%) |

Hazardous Alcohol Use Outcomes2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6+ Binge Drinking N (%) |

8+AUDIT N (%) |

4+AUDIT N (%) |

||

| Overall | ||||

| Age 15-23 years | ||||

| Overall (N=3,342) | 2110 (63.1%) | 1067 (31.9%) | 473 (14.2%) | 1022 (30.6%) |

| By energy drink use in past seven days | ||||

| None (N=2800) | 1676 (59.9%) | 795 (28.4%) | 329 (11.8%) | 769 (27.5%) |

| Any (N=542) | 434 (80.1%) | 269 (49.6%) | 144 (26.6%) | 253 (46.7%) |

| Chi-Square test p-value: | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 |

| Stratified by Age | ||||

| Age 15-17 years | ||||

| Overall (N=1508) | 711 (47.1%) | 258 (17.1%) | 108 (7.2%) | 241 (16.0%) |

| By energy drink use in past seven days | ||||

| None (N=1308) | 567 (43.3%) | 190 (14.5%) | 74 (14.1%) | 179 (13.7%) |

| Any (N=200) | 144 (72.0%) | 68 (34.0%) | 34 (26.8%) | 62 (31.0%) |

| Chi-Square test p-value: | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 |

| Age 18-20 years | ||||

| Overall (N=1094) | 745 (68.1%) | 419 (38.3%) | 185 (16.9%) | 392 (35.8%) |

| By energy drink use in past seven days | ||||

| None (N=895) | 592 (43.3%) | 316 (35.3%) | 126 (14.1%) | 295 (33.0%) |

| Any (N=199) | 153 (76.9%) | 103 (51.8%) | 59 (29.6%) | 97 (48.7%) |

| Chi-Square test p-value: | p=0.004 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 |

| Age 21-23 years | ||||

| Overall (N=740) | 654 (88.4%) | 387 (52.3%) | 180 (24.3%) | 389 (52.6%) |

| By energy drink use in past seven days | ||||

| None (N=597) | 517 (86.6%) | 289 (48.4%) | 129 (21.6%) | 295 (49.4%) |

| Any (N=143) | 137 (95.8%) | 98 (68.5%) | 51 (35.7%) | 94 (65.7%) |

| Chi-Square test p-value: | p=0.00 3 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 | p<0.001 |

Among N=3,342 participants who completed telephone based survey.

Alcohol use outcomes include ever consuming alcohol, ever consuming 6 or more alcohol drinks in one setting (6+ binge drinking), scoring an 8 or greater (8+AUDIT) or scoring a 4 or greater (4+AUDIT) on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

Chi-square p-values presented for comparison of distribution of each specific alcohol outcome within age group.

Rates for each of the three hazardous alcohol outcomes overall and stratified by age are also presented in Table II. Among adolescents aged 15-17 years old, 7.2% met the 8+AUDIT criterion for hazardous alcohol use, and 16.0% met the 4+AUDIT criterion. Notably, 866 (84.7%) of participants who met the 4+AUDIT criteria also met the 6+ binge drinking criterion. Rates of each hazardous alcohol outcome increased with age, with 24.3% of 21-23 year olds meeting the 8+AUDIT criteria and 52.6% meeting the 4+AUDIT criteria. The rates of 6+ binge drinking also increased with age. Energy drink use in the past seven days was significantly positively associated with each of the three hazardous alcohol use outcomes (Table II) overall and within each age group.

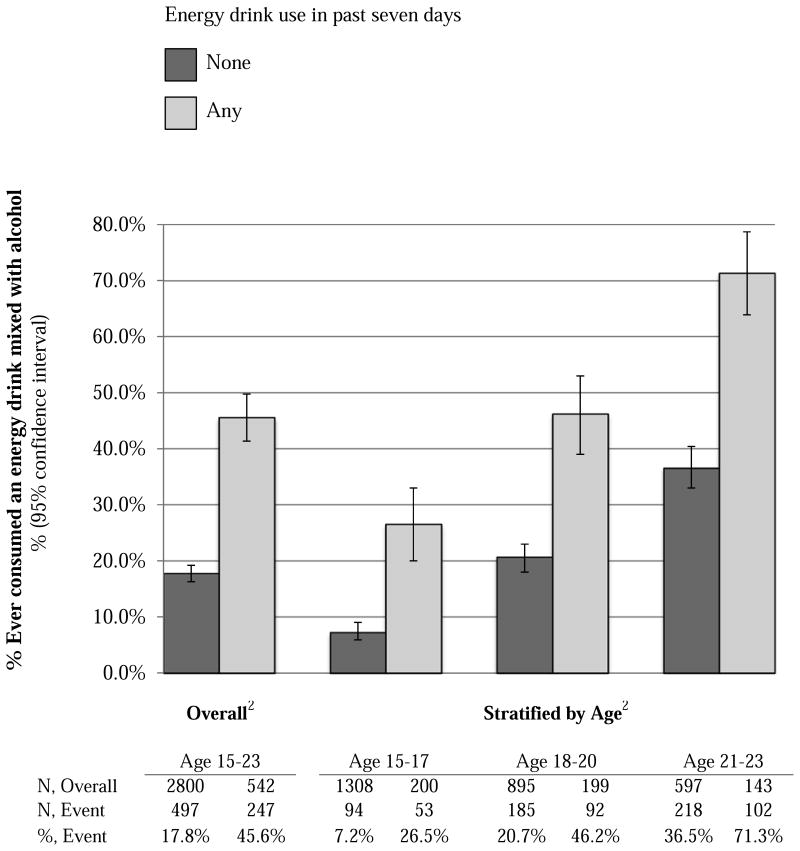

Energy drink use in the past seven days was significantly and positively associated with ever mixed-use of an energy drink with alcohol for all age groups (Figure), and the positive associations between recent energy drink use and each of the three hazardous alcohol outcomes as reported in Table II appeared mediated by ever mixed-use of an energy drink with alcohol (Table III). Among all participants who ever reported drinking alcohol, ever mixed-use of an energy drink with alcohol was strongly associated with the likelihood of each of the three hazardous alcohol outcomes adjusted for relevant covariates, and inclusion of ever mixed-use of an energy drink with alcohol attenuated the positive associations between recent energy drink use and each of the three hazardous alcohol outcomes (Table III). Importantly, those positive associations did not differ with age (all likelihood ratio test p-values >0.300).

Figure 1.

Unadjusted prevalence rates of ever mixed-use of an energy drink with alcohol by energy drink use in the past seven days, overall and stratified by age among a sample of adolescents and young adults.1,2

1 Among N=3,342 participants who completed a telephone based survey.

2 Rates of ever mixed-use of an energy drink with alcohol by recent energy drink use significantly different overall or within each age strata (all p<0.001).

Table 3.

Adjusted likelihood of alcohol use outcomes by energy drink use among a sample a sample of adolescents and young adults, limited to those who ever drank alcohol.1,2,3

| 6+ Binge Drinking | 8+AUDIT | 4+AUDIT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Base model3 | ||||||

| Energy drink use in past seven days | 1.34 (1.05-1.71) | 0.020 | 1.41 (1.08-1.84) | 0.010 | 1.18 (0.91-1.52) | 0.207 |

| Further adjusted for mixed-use3 | ||||||

| Energy drink use in past seven days | 1.01 (0.77-1.32) | 0.960 | 1.07 (0.81-1.42) | 0.635 | 0.85 (0.65-1.13) | 0.268 |

| Ever mixed-use of energy drink with alcohol | 4.69 (3.70-5.94) | <0.001 | 3.25 (2.51-4.21) | <0.001 | 4.15 (3.27-5.25) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Likelihood ratio test for interaction between mixed-use and age on alcohol outcome: | p=0.487 | p=0.308 | p=0.89 4 | |||

Subset of N=2,110 from full sample of N=3,342 participants who completed a telephone based survey.

Hazardous alcohol use outcomes include ever consuming 6 or more alcohol drinks in one setting (6+ binge drinking), scoring an 8 or greater (8+AUDIT) or scoring a 4 or greater (4+AUDIT) on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

All models adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, number of friends who drink, parental drinking frequency, and sensation seeking.

Discussion

In this national study of 15-23 year olds, recent use of energy drinks was associated with ever drinking alcohol among adolescents, suggesting recent energy drink use may identify those with an early-onset of alcohol use. Ever mixed-use of energy drinks with alcohol strongly predicted hazardous alcohol use among all age groups after adjusting for a number of established risk factors for alcohol problem drinking. Specifically, those who ever consumed energy drinks with alcohol were more than four times as likely to have ever engaged in hazardous binge drinking of 6 more drinks, three times as likely to meet the AUDIT criterion for hazardous alcohol use as defined for an adult population (8+AUDIT), and four times as likely to meet the AUDIT criterion as defined for an adolescent population (4+AUDIT) 41,42 as compared with their peers who had never consumed an energy drink mixed with alcohol.

Our findings are consistent with the many studies reporting positive associations between mixed-use of energy drinks with alcohol and alcohol abuse among college students, and also two studies among adolescents and young adults. Specifically, one national survey reported that regular energy drink use strongly predicted past 30-day alcohol use among 8th graders (adjusted odds ratio 3.3) and 10th and 12th graders (adjusted odds ratios 2.1) 10. Another study of 13-20 year olds who consume alcohol reported a 6-fold increase in the likelihood of binge drinking among participants who consumed energy drinks, shots, or caffeine pills with alcohol in the past 30 days compared with their peers who did not report such mixed-use12. Our study reports a positive association between mixed-use of energy drinks with alcohol and an increased risk of alcohol use disorder as defined by a clinically valid scale (ie, AUDIT) among adolescents and young adults. Our results further highlight that the problematic associations between energy drink use and alcohol abuse are not limited to youth in a college setting.

Pairing energy drinks with alcohol may increase the risk of binge drinking due to a high intake of caffeine, which lowers the subjective level of impairment due to alcohol and reduces one's perception of intoxication.18,26 Caffeine may also counter the depressant effects of alcohol, increasing alertness and leading to a longer time frame of drinking.18,26 Although the caffeine content of one energy drink may be similar to that of a cup of strong coffee, many adolescents and young adults are likely to consume more than one energy drink when drinking alcohol. Malinauskas et al surveyed 496 undergraduate college students and found that of those who consumed energy drinks with alcohol in the past month (n=139), 49% consumed three or more energy drinks with alcohol at any one occasion; 73% consumed two or more22.

Other mechanisms may be in play. Caffeine is generally a rewarding stimulant and caffeine use during adolescence may prime the brain to the additional rewarding effects of other stimulants.47 Alcoholic beverages consumed with caffeine may also result in an increased desire for continued consumption of alcohol as compared with alcoholic beverages not consumed with caffeine.48 It is also likely that energy drink consumption is associated with a general risk-taking profile that is independently associated with hazardous alcohol use.31 Such associations have been reported among college students.24,31 Among a national sample of adolescents in middle and high school from the Monitoring the Future study, it was reported that not only did any energy drink use on a typical day predict past 30-day alcohol use, but past 30-day use of cigarettes, marijuana, and amphetamines.10 These findings are consistent with those reported for a college population.48 Although this current study tried to control for general risk taking propensity (sensation seeking), continued studies are needed to specifically address how energy drinks may affect hazardous drinking49.

In this study, recent energy drink use predicted hazardous alcohol use (6+ binge drinking and 8+AUDIT), associations largely mediated by ever mixed-use of an energy drink with alcohol. Thus, recent energy drink use may positively identify adolescents and young adults at risk for hazardous alcohol use. If prospective studies confirm such associations, recent energy drink use and the mixed-use of energy drinks with alcohol may be useful additions to alcohol screeners for a clinical setting to enhance the identification of adolescents and young adults at risk for hazardous alcohol use50. For the individual clinician, asking adolescents about recent energy drink use may be a non-confrontational way to begin conversations about alcohol use.

This study has strengths and limitations. Strengths include the large sample size recruited nationally, and the rates of energy drink use in the past 7 days among 15-17 year olds (13.3%) were similar to the rates among 815 12-17 year olds14 from a 2011 cross-sectional study (8.5% reported any use in the past 7 days) and among 2,793 adolescents in 6th to 12th grade (14.7% consumed at least one energy drink per week).48 However, our current study is cross-sectional we cannot prove causality between energy drink use and alcohol outcomes. Further, we cannot confirm that mixed-use of an energy drink with alcohol occurred during the same occasion as any binge or hazardous drinking. This study underestimates the rates of binge drinking in our adolescent population by defining binge drinking with a conservative criterion of 6 or more drinks in one session. Thus, our effect size estimates of energy drink use on binge drinking are conservative given the young age of the sample population. Particularly, important differences related to energy drink use and alcohol misuse by age may have been obscured. Also, this study assessed hazardous alcohol outcomes in reference to the past year, yet measured ever use of an energy drink mixed with alcohol. Finally, we measured recent energy drink use as any use in the past 7 days, and recent use was positively associated with alcohol use outcomes in unadjusted models. Several previous studies have measured recent energy drink use as use in the past 30 days, and it is worthwhile to consider how a longer time frame for recent use may associate with hazardous alcohol use independently of mixed use with alcohol.

Footnotes

Study design; conduct of the study; data collection, management, and analysis; and manuscript preparation, review, and approval were provided by <> (CA077026, AA015591 and AA021347). Data analysis, and manuscript preparation, review, and approval was provided by the Norris Cotton Cancer Center.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; [Google Scholar]

- 2.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: The NSDUH Report - - Quantity and Frequency of Alcohol Use among Underage Drinkers. http://www.samhsa.gov/ Available from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k8/underage/underage.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Grant BF. Age at first drink and the first incidence of adult-onset DSM-IV alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:2149–2160. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Rockville, MD: The DAWN Report: Trends in Emergency Department Visits Involving Underage Alcohol Use: 2005 to 2009. http://www.samhsa.gov/ Available from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k11/WEB_DAWN_020/WEB_DAWN_020_HTML.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Center for Science in the Pulic Interest. Caffeine content of food and drugs. https://www.cspinet.org. Available from http://www.cspinet.org/new/cafchart.htm.

- 8.Blankson KL, Thompson AM, Ahrendt DM, Patrick V. Energy drinks: what teenagers (and their doctors) should know. Pediatr Rev. 2013;34:55–62. doi: 10.1542/pir.34-2-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pomeranz JL, Munsell CR, Harris JL. Energy drinks: an emerging public health hazard for youth. J Public Health Policy. 2013;34:254–271. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2013.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terry-McElrath YM, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Energy drinks, soft drinks, and substance use among United States secondary school students. J Addict Med. 2014;8:6–13. doi: 10.1097/01.ADM.0000435322.07020.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Branum AM, Rossen LM, Schoendorf KC. Trends in Caffeine Intake Among US Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;133:386–393. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kponee KZ, Siegel M, Jernigan DH. The use of caffeinated alcoholic beverages among underage drinkers: Results of a national survey. Addict Behav. 2014;39:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park S, Blanck HM, Sherry B, Brener N, O'Toole T. Factors associated with sugar-sweetened beverage intake among United States high school students. J Nutr. 2012;142:306–312. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.148536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar GS, Park S, Onufrak S. Association between reported screening and counseling about energy drinks and energy drink intake among U.S. adolescents. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94:250–254. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seifert SM, Schaechter JL, Hershorin ER, Lipshultz SE. Health effects of energy drinks on children, adolescents, and young adults. Pediatrics. 2011;127:511–528. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roehr B. Energy drinks: cause for concern of scaremongering? BMJ. 2013;347:1–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marin Institute. Alcohol, energy drinks, and youth: a dangerous mix. 2008 www.odmhsas.org. Available from http://www.odmhsas.org/resourcecenter/%28S%28gajpvtjds12beveqawchnw45%29%29/ResourceCenter/Publications/Current/330.pdf.

- 18.Arria AM, O'Brien MC. The “high” risk of energy drinks. JAMA. 2011;305:600–601. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Kasperski SJ, et al. Increased alcohol consumption, nonmedical prescription drug use, and illicit drug use are associated with energy drink consumption among college students. J Addict Med. 2010;4:74–80. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181aa8dd4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arria AM, Caldeira KM, Kasperski SJ, Vincent KB, Griffiths RR, O'Grady KE. Energy drink consumption and increased risk for alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:365–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01352.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brache K, Stockwell T. Drinking patterns and risk behaviors associated with combined alcohol and energy drink consumption in college drinkers. Addict Behav. 2011;36:1133–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malinauskas BM, Aeby VG, Overton RF, Carpenter-Aeby T, Barber-Heidal K. A survey of energy drink consumption patterns among college students. Nutr J. 2007;6:35. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-6-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marczinski CA. Commentary on Rossheim and Thombs (2011): artificial sweeteners, caffeine, and alcohol intoxication in bar patrons. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:1729–1731. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01603.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller KE. Energy drinks, race, and problem behaviors among college students. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43:490–497. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Brien MC, McCoy TP, Rhodes SD, Wagoner A, Wolfson M. Caffeinated cocktails: energy drink consumption, high-risk drinking, and alcohol-related consequences among college students. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:453–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patrick ME, Maggs JL. Energy Drinks and Alcohol: Links to Alcohol Behaviors and Consequences Across 56 Days. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54:454–459. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snipes DJ, Benotsch EG. High-risk cocktails and high-risk sex: examining the relation between alcohol mixed with energy drink consumption, sexual behavior, and drug use in college students. Addict Behav. 2013;38:1418–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thombs DL, O'Mara RJ, Tsukamoto M, et al. Event-level analyses of energy drink consumption and alcohol intoxication in bar patrons. Addict Behav. 2010;35:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Velazquez CE, Poulos NS, Latimer LA, Pasch KE. Associations between energy drink consumption and alcohol use behaviors among college students. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marczinski CA. Alcohol mixed with energy drinks: consumptions patterns and motivations for use in U.S. college students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8:3232–3245. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8083232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller KE. Wired: energy drinks, jock identity, masculine norms, and risk taking. J Am Coll Health. 2008;56:481–489. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.5.481-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wells BE, Kelly BC, Pawson M, Leclair A, Parsons JT, Golub SA. Correlates of concurrent energy drink and alcohol use among socially active adults. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2013;39:8–15. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.720320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferreira SE, de Mello MT, Pompeia S, de Souza-Formigoni ML. Effects of energy drink ingestion on alcohol intoxication. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:598–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT. Clubgoers and their trendy cocktails: implications of mixing caffeine into alcohol on information processing and subjective reports of intoxication. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;14:450–458. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.4.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT, Henges AL, Ramsey MA, Young CR. Effects of energy drinks mixed with alcohol on information processing, motor coordination and subjective reports of intoxication. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;20:129–138. doi: 10.1037/a0026136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McClure AC, Stoolmiller M, Tanski SE, Engels RC, Sargent JD. Alcohol marketing receptivity, marketing-specific cognitions, and underage binge drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:E404–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01932.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Babor TF, H-B J, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. 2nd. Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence, World Health Organization; 2011. [Accessed February 2014]. AUDIT The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in primary care. Available at http://www.talkingalcohol.com/files/pdfs/WHO_audit.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE, Martz ME, Maggs JL, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Extreme binge drinking among 12th-grade students in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:1019–1025. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Donovan JE. Estimated blood alcohol concentrations for child and adolescent drinking and their implications for screening instruments. Pediatrics. 2009;123:e975–981. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chung T, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Rohsenow DJ, Spirito A, Monti PM. Screening adolescents for problem drinking: performance of brief screens against DSM-IV alcohol diagnoses. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:579–587. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chung T, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Monti PM. Alcohol use disorders identification test: factor structure in an adolescent emergency department sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:223–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zuckerman M. Behavioral expressions and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arnett J. Sensation seeking: A new conceptualization and a new scale. Person Indiv Diff. 1994;16:289–296. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sargent JD, Tanski S, Stoolmiller M, Hanewinkel R. Using sensation seeking to target adolescents for substance use interventions. Addiction. 2010;105:506–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02782.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.R Core Team. R A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna A: RFfSC; [Google Scholar]

- 47.Temple JL. Caffeine use in children: what we know, what we have left to learn, and why we should worry. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:793–806. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woolsey CL, Barnes LB, Jacobson BH, Kensinger WS, Barry AE, Beck NC, et al. Frequency of energy drink use predicts illicit prescription stimulant use. Subst Abus. 2014;35:96–103. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2013.810561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marczinski CA, Fillmore MT, Henges AL, Ramsey MA, Young CR. Mixing an energy drink with an alcoholic beverage increases motivation for more alcohol in college students. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:276–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01868.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Knight JR, Sherritt L, Shrier LA, Harris SK, Chang G. Validity of the CRAFFT substance abuse screening test among adolescent clinic patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:607–614. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.6.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]