Abstract

The rate of Mexico-U.S. migration has declined precipitously in recent years. From 25 migrants per thousand in 2005, the annual international migration rate for Mexican men dropped to 7 per thousand by 2012. If sustained, this low migration rate is likely to have a profound effect on the ethnic and national-origin composition of the U.S. population. This study examines the origins of the migration decline using a nationally representative panel survey of Mexican households. The results support an explanation that attributes a large part of the decline to lower labor demand for Mexican immigrants in the United States. Decreases in labor demand in industrial sectors that employ a large percentage of Mexican-born workers, such as construction, are found to be strongly associated with lower rates of migration for Mexican men. Second, changes in migrant selectivity are also consistent with an economic explanation for the decline in international migration. The largest declines in migration occurred precisely among the demographic groups most affected by the Great Recession: namely, economically active young men with low education. Results from the statistical analysis also show that the reduction in labor demand in key sectors of the U.S. economy resulted in a more positive educational selectivity of young migrants.

Keywords: International migration, Migrant selectivity, Great Recession, Mexico

Introduction

Mexican migration to the United States during the final decades of the twentieth century ranks among the largest international population flows in the world. The number of Mexican migrants to the United States since the 1970s even surpasses those from many European countries in the late nineteenth century (Passel et al. 2012). This wave of Mexican migration has had a profound effect on the ethnic and national-origin composition of the United States. In 2010, almost 12 million U.S. residents were born in Mexico, accounting for 29 % of the total foreign-born population (Grieco et al. 2012). Although the rate of Mexico-U.S. migration fluctuated in response to various demographic, economic, and policy-related factors during this time, it showed no signs of stopping (Hanson 2006; Massey and Pren 2012; Massey et al. 2002). Indeed, some researchers argued that the flow of Mexican migrants was self-sustaining because information conveyed back to the communities of origin by successful migrants encouraged others to follow, making migration rates less sensitive to economic downturns and border enforcement policy (Massey 1990; Massey et al. 1994a; Rivero-Fuentes 2004). Yet, the rate of Mexican migration in fact began to fall sharply in the mid-2000s such that by 2012, the net flow of migrants from Mexico to the United States had essentially stopped (Passel et al. 2012).

The dramatic decline in Mexico-U.S. migration since the mid-2000s has been linked to the contraction in the U.S. economy among other factors (Fix et al. 2009; Massey 2012; Passel et al. 2012; Chiquiar and Salcedo 2013). However, previous studies have not been able to properly test the effect of U.S. economic performance against alternative explanations in part because of a lack of suitable data. Specialized demographic and migration surveys carried out in Mexico do not cover the time period with sufficient frequency and are often not nationally representative. Sources in the United States, such as the Current Population Survey (CPS) and the American Community Survey (ACS), substantially undercount the number of undocumented migrants (Genoni et al. 2012). In this article, I use data from the Mexican National Occupation and Employment Survey (ENOE), a nationally representative survey of Mexican households conducted quarterly, to estimate the decline in Mexico-U.S. migration from 2005 to 2013. I also test the effect that the slowdown in economic growth and the reduction in labor demand in sectors of the U.S. economy that employ the largest share of Mexican-born workers had on the rate of international migration from Mexico. Finally, I examine changes in the selectivity of Mexican migrants during this period of rapidly declining migration. In particular, I consider how changing economic conditions in the United States has led to shifts in the educational selectivity of international migrants. Although a large research literature has examined the extent to which Mexican migrants are selected based on their level of education (Chiquiar and Hanson 2005; Hanson 2006; Ibarraran and Lubotsky 2007; McKenzie and Rapoport 2010; Orrenius and Zavodny 2005), few studies have been able to test how changes in U.S. labor markets affect the level of selectivity or how the educational selectivity of migrants changed during the recent U.S. Great Recession.

Economic Conditions in the U.S. and Mexico-U.S. Migration

A well-established theoretical perspective associated with neoclassical economics suggests that individuals' decisions to migrate are based on a calculation of the difference in the economic opportunities available in their place of origin and intended destination (Borjas 1999; Todaro 1969; Todaro and Maruszko 1987). Empirical studies have generally supported the hypothesis that economic opportunities in destination countries, as measured by the overall levels of employment and wages, have a significant effect on the inflow of migrants (Hanson 2006; Hanson and Spilimbergo 1999; Massey et al. 1994b). Given its detrimental effect on employment conditions, we may therefore expect the recent U.S. recession to have contributed to the decline in Mexico-U.S. migration. This is more so the case because the recession reduced labor demand precisely in economic sectors that have traditionally employed Mexican immigrants, such as construction. Before the Great Recession began, 32 % of Mexican-born male workers in the United States were employed in construction, constituting a larger share than in any other sector, including manufacturing (17 %), leisure and hospitality (15 %), and professional and business services (11 %), which were the next largest sectors employing Mexican-born men (U.S. Census Bureau 2007).

However, the relation between the economic recession and the decline in Mexican migration to the United States is not straightforward. Particularly problematic is that the decline in migration preceded the start of the recession. Immigration from Mexico to the United States began to fall as early as 2006, but the U.S. recession did not officially start until the first quarter of 2008 (Business Cycle Dating Committee, NBER 2008). Nevertheless, labor demand in some sectors of the U.S. economy, such as the construction sector, began to decrease well before the onset of the recession (Goodman and Mance 2011; Hadi 2011). Job losses in economic sectors that employ a disproportionate percentage of Mexican workers in the United States, such as construction, may have therefore initiated the decline in migration before the official start of the U.S. recession. Although the unemployment rate for Mexican-born men could in principle be used to track labor market conditions for recent immigrants, unemployment statistics for the foreign-born population in the United States are not available with sufficient frequency. Moreover, the unemployment rate for Mexican-born men cannot strictly be considered an exogenous predictor of migration because a decrease in the migration rate may result in the presence of fewer Mexican-born men seeking jobs, thus contributing to a lower unemployment rate for that group. In the analysis presented in this article, I therefore use changes in the combined number of jobs gained in the top employment sectors for Mexican-born workers as a proxy for the labor demand for Mexican immigrants. Information regarding job gains is available by sector on a quarterly basis and is less affected by the supply of immigrant labor.

Alternative Explanations

Employment conditions in the United States are not the only possible explanation for the decline in Mexican migration in recent years. In this section, I discuss three alternative explanations that have been proposed (Passel et al. 2012) and outline the strategies used to incorporate each of these explanations in the statistical analysis that follows.

Economic Conditions in Mexico

An improvement in the economic conditions in Mexico could have contributed to the decline in international migration since the mid-2000s by expanding the opportunities available for Mexican workers at home, thereby dissuading them from moving abroad. Researchers have generally found a strong connection between the rate of international migration and economic conditions in sending countries (Massey et al. 1994b). Emigration from Mexico, in particular, appears to have increased with the deepening of the economic crisis in that country in the mid-1980s (Cerrutti and Massey 2004; Massey and Espinosa 1997; Massey et al. 2002). Since the late-1990s, Mexico has experienced over a decade of economic stability and modest levels of growth, disrupted only by the recession of 2008–2009. Yet, such economic growth has not resulted in a substantial improvement in the standard of living of most Mexicans. Average household income, when adjusted for inflation, actually decreased slightly from 1998 to 2010 (Passel et al. 2012), and the official poverty rate remains high at 52.1 % (Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social, (CONEVAL) 2012). My analysis of individuals' decisions to migrate will nevertheless account for the effect of economic conditions at both the individual and community levels in Mexico.

Immigration Law Enforcement

A second alternative explanation attributes the decline in Mexico-U.S. migration to the increase in immigration law enforcement efforts over the past two decades. U.S. government spending on border patrol has increased ninefold since 1992 (U.S. Department of Homeland Security 2012). The total size of the Border Patrol staff also rose by more than 400 %, and the number of person-hours spent by agents patrolling the border—“line-watch hours”—increased almost 700 % during the same period.1 These changes in border enforcement could have potentially reduced U.S.-bound migration from Mexico by increasing both the monetary cost and physical danger of crossing the border without authorization. However, evidence from previous studies suggests that greater border enforcement efforts during the 1990s did not affect the flow of undocumented migrants (Cornelius 2001; Espenshade 1994; Massey et al. 2002). Most importantly, the timing is once again not right. The increase in border enforcement precedes the onset of the decline in migration by well over a decade. Border patrol expenditures began increasing notably in the early 1990s, but Mexican migration to the United States did not fall until the mid-2000s. Nevertheless, following previous studies that used Border Patrol staffing as a measure of immigration law enforcement (e.g., Donato et al. 2008; Massey and Riosmena 2010; Orrenius and Zavodny 2005), I control for the total number of agents assigned to the border region in the models predicting Mexican men's odds of migrating.2

Demographic Changes and Declining Fertility

A third explanation attributes the decline in Mexico-U.S. migration to the changing demographic characteristics of the Mexican population and, in particular, to declining fertility rates over the past several decades (Passel et al. 2012). The total fertility rate in Mexico dropped from approximately 6 children per woman in 1974 to 2.08 children per woman in 2009 (Romo Viramontes and Sánchez Castillo 2009). A decline in fertility of this magnitude could affect the rate of international migration in several ways. First, the fertility decline could result in a reduction in the size of the Mexican population entering the labor market each year, which may put upward pressure on Mexican wages and thereby make migration less attractive (Hanson and McIntosh 2009, 2010, 2012). In other words, the effect of lower fertility rates on migration may be mediated by its effect on local economic conditions discussed earlier. Second, declining fertility may also lower the rate of international migration from Mexico more directly by simply reducing the size of the working-age male population that is typically at greater risk of migrating. Finally, the decline in fertility could affect international migration rates from Mexico by reducing the size of Mexican families. Previous studies have found that the odds of migration for Mexican men increase with the number of dependent children at home (Kanaiaupuni 2000; Massey and Espinosa 1997; Massey et al. 1987). With fewer children to sustain economically, Mexican men may be less likely to make the arduous journey north. My statistical analysis will account for changes in demographic characteristics that are tied to the long-term fertility decline, including men's age and the number of household residents and dependent children.

To summarize, in the first part of the analysis, I will test models that examine the effect of economic conditions in the United States on individuals' decisions to migrate internationally from Mexico. Job gains in sectors of the U.S. economy employing the largest share of Mexican-born workers will be used as a proxy for labor demand for Mexican immigrants. The models will also control for three alternative explanations for the decline in migration during this time period. Individual- and community-level economic indicators will be introduced as predictors to account for the effect of local economic conditions in Mexico. The number of Border Patrol agents assigned to the Southwest sector will be used to control for the effect of border enforcement efforts. Finally, the models will also account for the effect of changes in the demographic characteristics of the Mexican population associated with the long-term fertility decline.

Changes in Migrant Selectivity With Decreasing Migration

A second objective of this study is to examine how the selectivity of Mexican migrants has changed during the period of declining migration. Changes in the profile of individuals that are more likely to migrate from Mexico are important, among other reasons, because they may affect U.S. and Mexican labor markets. Changes in migrant selectivity may also inform us about the reasons for the overall decline in migration. For example, if the decline in Mexican migration is due to lower labor demand in the United States during the recent recession, then we should observe a disproportionate reduction in the odds of migrating precisely among those most affected by the recession: namely, working-age men with relatively low skill levels (Bell and Blanchflower 2011; Elsby et al. 2010; Pew Economic Mobility Project 2013).

Studies conducted using data from the high-migration period that preceded the recent decline suggest a general decrease in selectivity over time. The decrease in selectivity with increasing migration rates is consistent with cumulative causation theory of international migration (Fussell and Massey 2004; Massey 1990; Massey et al. 1994a; Rivero-Fuentes 2004). According to this theory, information transmitted back to the communities of origin by former residents who have successfully migrated lowers the risk and costs of moving abroad, thus making migration accessible to new categories of individuals for whom migration was previously too costly. Massey et al. (1994a) found that as migration became more prevalent in 19 sending communities in Mexico during the second half of the twentieth century, the migration stream became more diverse (less selective) with regard to age, education, and occupation, among other characteristics (see also Cerrutti and Massey 2004).

Reversing the logic of cumulative causation theory, one might expect an overall increase in migrant selectivity during the period of decreasing migration that began in 2005. However, the profile of migrants will not necessarily revert back to what it was during the early period of migration in the mid-twentieth century, when young married men first migrated in search of work. Instead, the change in selectivity will be driven by changes in labor demand in the United States. Young men with relatively low levels of education are expected to be the first to stop migrating because their employment prospects have worsened disproportionately (Bell and Blanchflower 2011; Elsby et al. 2010; Pew Economic Mobility Project 2013). Thus, if the decline in migration is indeed driven by changes in U.S. labor demand, the decrease in the rate of migration should be larger for younger and less-educated men during this time.

To examine how migrant selectivity changed after the U.S. recession, in the analysis that follows, I will compare the relative odds of migration for men of different age, education, and employment status, before and after the onset of the recession in the first quarter of 2008. The analysis is limited to men because they are much more likely to migrate independently in search of work than for other reasons, such as family reunification (Cerrutti and Massey 2001; Donato 1993; Donato and Patterson 2004).3 Finally, in separate models, I also test the specific effect that changes in the labor demand in key sectors of the U.S. economy had on the educational selectivity of migrants from 2005 to 2012. I expect the decline in labor demand in top employment sectors for Mexican-born workers to be most strongly associated with a decrease in the relative odds of migration of less-educated Mexican men.

Data and Measurements

Data for this study are drawn from the Mexican National Occupation and Employment Survey (Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo (ENOE)), which is the primary employment survey in Mexico (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI) 2010). The ENOE collects information from all individuals residing in a large nationally representative sample of Mexican households. The sample of households is not only nationally representative but is also representative of each of the 31 Mexican states and the Federal District, four levels of urbanization, and 32 major cities. Like employment surveys in other countries, the ENOE has a rotating panel structure in which individuals are interviewed five times in consecutive quarters. Panels are staggered such that 20 % of the respondents are in their first, second, third, fourth, and fifth interview, respectively. After the initial interview, each time a household is sampled, the roster of household members is compared against that from the previous interview. Any losses or additions to the household roster are noted. For every household member who is no longer present, a reason is given. One reason is international migration; others are internal migration within the state, internal migration to another state, and death.

In the analysis that follows, I define an international migrant as any individual who was living in the household in the first interview but who migrated abroad during the course of the following year (four additional quarters). Observing migration over a one-year period rather than over a single quarter makes the migration estimates more stable and eliminates the need to adjust for seasonal variations. I use data from all panels of the ENOE that are observed for four full quarters (five interviews) from the first quarter of 2005 (when the ENOE series began) to the third quarter of 2013 (the most recent available wave). This period spans 35 quarters and includes 31 complete panels (those that are observed for a full year). Because I am interested in examining the effect of U.S. labor market conditions on the odds of emigration, I limit the sample to individuals of working age (15 to 55 years). As discussed in the previous section, I limit the sample to men because they are much more likely to migrate independently in search of work.4

In the first part of the analysis, I use random-effects logit models to test the effect of employment conditions in the United States on individuals' odds of migrating abroad. Quarter-specific error terms are used to capture unmodeled heterogeneity for each time point. Aggregate measures of economic performance are lagged because it will take some time for individuals residing in Mexico to receive and react to information about economic conditions in the United States. Specifically, all economic measures are calculated by taking the corresponding average for the four quarters preceding the first interview for each respondent.5 To make the coefficients for the baseline category easier to interpret in the selectivity models, all economic variables are centered on their means for the entire period considered.

Economic Conditions in the United States

To test the effect of the overall growth in the U.S. economy on individuals' odds of migrating, I first introduce as a predictor the average seasonally adjusted gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate in the United States over the previous four quarters. Second, because the overall growth rate does not necessarily reflect the labor market conditions for Mexican immigrants in the United States, I also include as a predictors several different proxy measures of employment opportunities for Mexican immigrants. I begin with the unemployment rate for Mexican-born men. As discussed earlier, this measure has several disadvantages. First, the unemployment rate for Mexican-born men is available only on an annual basis, leading to a loss of information regarding short-term fluctuations. Second, estimates of the unemployment rate for Mexican-born men obtained from the March CPS are limited by the substantial underrepresentation of undocumented migrants in U.S. data sources (Genoni et al. 2012). Finally, using the unemployment rate for Mexican-born men as a predictor of immigration also introduces the potential for reverse causation because a decrease in migration may result in the presence of fewer Mexican-born men seeking jobs, thus contributing to a lower unemployment rate.

As a second measure of employment opportunities for Mexican immigrants, I use the unemployment rate for Mexican-American men. Although this measure is available quarterly, it is limited in that it not only captures the employment status of Mexican men who have recently migrated but also that of Mexican American men whose families have been in the United States for several generations. The labor market opportunities for second- and third-generation Mexican-American men will generally differ from the opportunities available to new immigrants.

Finally, I derive an alternative set of measures of the labor demand for Mexican immigrant men from reports of the gross job gains in industrial sectors that employ the largest share of Mexican-born male workers. Table 1 shows the percentage of Mexican-born male workers employed in the top five industrial sectors according to results from the March CPS for 2006 and 2011.6 As discussed in previous sections, the construction sector employs by far the largest share of Mexican-born men, followed by manufacturing, leisure and hospitality, professional business services, and wholesale and retail trade. Together, these five sectors employed over 80 % of Mexican-born male workers in 2006.7 In the regression models, I use as a predictor the average number of jobs gained in these top five sectors combined. I also use as alternative predictors the number of jobs gained in the top three sectors as well as in the top overall sector: namely, construction. The number of jobs gained in each sector is obtained from the Business Employment Dynamics (BDM) series compiled by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) (measured in hundreds of thousands of workers). BDM statistics are generated from a census of all establishments whose workers are covered by state unemployment insurance programs.8

Table 1.

Percentage of Mexican-born male workers employed in the top five major industrial sectors

| 2006 | 2011 | % Change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Construction | 31.6 | 25.3 | −19.9 |

| Manufacturing | 16.6 | 14.7 | −11.4 |

| Leisure and Hospitality | 15.2 | 13.7 | −9.9 |

| Professional and Business Services | 10.9 | 12.5 | 14.7 |

| Wholesale and Retail Trade | 8.7 | 11.0 | 26.4 |

Notes: Includes only civilian men aged 16 years and older. Estimates were obtained from published reports for the foreign-born population from the March CPS.

Economic Conditions in Mexico

I control for the economic conditions in Mexico by using the local unemployment rate and average wages (measured in pesos per hour worked). Because the ENOE contains representative samples of 32 major cities, I am able to obtain accurate estimates for these cities for each quarter. The unemployment rate and mean wages for other locations are approximated by the corresponding state-level values. As explained later in the article, the regression models also control for the economic conditions at the individual and household levels, including individuals' employment status and household income. Together, all these measures should capture the effect that the improving economic situation in Mexico may have had on the decline in international migration.

Immigration Law Enforcement

I control for the effect of border enforcement on individuals' odds of migrating, using the total number of Border Patrol agents assigned to the Southwest sector.9 The number of Border Patrol agents assigned to the Southwest sector is a better measure than the total number of agents in the country because this sector covers the border with Mexico. Although line-watch hours would be a preferable measure given that they capture the time actually spent by agents patrolling the border, line-watch hours are available only until 2009. However, line-watch hours were found to be strongly correlated with staffing in the Southwestern sector between 1993 and 2009 (r = .99). To check the robustness of my findings, I tested models using three alternative measures of immigration law enforcement: (1) the number of deportations of Mexican citizens; (2) the size of the population in jurisdictions that signed a 287(g) agreement with the federal government to aid in the identification and processing of undocumented migrants; and (3) the total number of employers using the E-Verify system to check employees' work eligibility. The results of models using these alternative measures (presented in Online Resource 1) are consistent with those presented herein.

Changes Associated With Fertility Decline

As discussed previously, declining fertility rates in Mexico over the past several decades are expected to alter the age and family structure of the Mexican population— and, consequently, the overall rate of international migration among Mexican men. Because older men are less likely to migrate, an increase in men's age could contribute to a reduction in the international migration rate. Similarly, men from larger families and those with more dependent children are expected to migrate more frequently to sustain their families. A reduction in the size of households and the number of dependent children as a result of the fertility decline could therefore also reduce the rate of migration. The statistical models account for these demographic changes associated with the long-term fertility decline by controlling for men's age and the total number of residents and children living in the household. Finally, the regression models also control for the mean age of men in the community of origin to account for the gradual aging of the local population. An aging of the local population may lead to lower odds of migration among Mexican men (net of individual men's own age) by altering the age-specific labor supply. For example, if individuals of different ages are not perfectly substitutable in the labor market, a smaller cohort size may lead to lower labor supply and higher wages for young men.

Individual Characteristics

In addition to the age of men and their household structure, the statistical models also control for the educational attainment, marital status, and employment condition of respondents, as well as whether they were born in another state. Changes in migrant selectivity will be measured by comparing the corresponding coefficients for all these variables before and after the onset of the recession. In subsequent models, the measures of economic conditions in the United States are also interacted with respondents' education in order to test their effect on the educational selectivity of Mexican migrants. Educational attainment is controlled using dummy variables for five categories: less than a primary education (used as the baseline category), complete primary school, complete middle school (secundaria), complete high school or technical degree, and complete college or more. Marital status is controlled using dummy variables for four categories: single (used as the baseline category); married; cohabiting; and separated, widowed, or divorced. Married and cohabiting men are expected to migrate at higher rates given their need to support families at home. I control for whether an individual was born out of his current state of residence in order to account for step migration. Individuals who previously migrated from another part of Mexico are thought to be predisposed to migrate to the United States (Fussell 2004).

Men's employment status at the time of the first interview is entered as a predictor in all the regression models. Four employment categories are distinguished: not economically active; employed in the informal sector; employed in the formal sector; and unemployed. Non-economically active men are expected to have the lowest odds of migrating because they will be less inclined to move in search of work. Among those who are economically active, unemployed men will be most likely to migrate given their need to find work. Following Villarreal and Blanchard (2013), I expect men employed in the informal sector to have significantly higher odds of migrating than those in the formal sector because they face generally worse employment conditions in their communities of origin. The regression models also control for the total household income in thousands of pesos per month at the time of the first interview (i.e., before migration). A greater household income will generally reduce the incentive to migrate because there will be less need to generate additional income by sending family members abroad.

A large research literature on international migration has found that greater ties to former community members who have migrated increase the odds of migration (e.g., Curran and Rivero-Fuentes 2003; Davis et al. 2002). I control for the effect of international migrant networks by including as a predictor the proportion of the municipal residents who were return migrants in 2000 according to the population census.10 The regression models also control for the level of urbanization of the communities of origin. Four levels of urbanization are distinguished: cities or towns with less than 2,500 residents (used as the baseline category); 2,500 to 14,999 residents; 15,000 to 99,999 residents; and 100,000 residents or more (including the 32 oversampled cities). Individuals living in more rural areas are expected to have higher odds of migration (Fussell and Massey 2004; Massey et al. 1987). Finally, research on international migration has also documented significant differences in emigration rates across regions of Mexico (Durand et al. 2001). In particular, migration rates are much higher from the historic migration region in central Mexico as well as from states located along the northern border with the United States. I control for these regional differences using dummy variables for the historic migration region as defined by Durand et al. (2001), and the border states. Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for all individual and household variables included in the analysis.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for Mexican men according to their migration status

| All | Nonmigrants | Migrants | |

|---|---|---|---|

| International Migration (per 1,000) | |||

| Age | |||

| 15 to 25 years | 36.0 | 35.9 | 45.2 |

| 26 to 35 years | 24.1 | 24.0 | 28.0 |

| 36 to 45 years | 22.6 | 22.6 | 19.2 |

| 46 to 55 years | 17.3 | 17.5 | 7.6 |

| Education | |||

| Less than primary | 12.4 | 12.4 | 15.8 |

| Complete primary | 21.5 | 21.4 | 30.0 |

| Complete middle school | 34.7 | 34.7 | 36.6 |

| Complete high school or technical degree | 20.0 | 20.1 | 12.9 |

| Complete college or more | 11.4 | 11.5 | 4.7 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 40.7 | 40.6 | 45.2 |

| Married | 43.2 | 43.3 | 40.7 |

| Cohabiting | 13.2 | 13.2 | 12.7 |

| Separated, divorced, or widowed | 2.9 | 2.9 | 1.5 |

| Born Out of State | 19.1 | 19.1 | 13.9 |

| Employment | |||

| Not economically active | 16.1 | 16.2 | 14.6 |

| Employed informal sector | 49.8 | 49.6 | 65.5 |

| Employed formal sector | 30.1 | 30.4 | 13.8 |

| Unemployed | 3.9 | 3.9 | 6.2 |

| Household Variables | |||

| Ave. number of household members | 4.9 | 4.9 | 5.5 |

| Ave. number of children in household | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.3 |

| Ave. household income (thousand pesos per month) | 8.1 | 8.1 | 5.8 |

| Contextual Variables | |||

| Mean wages (pesos per hour) | 29.4 | 29.4 | 26.8 |

| Unemployment rate | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.1 |

| Ave. age of men | 32.2 | 32.2 | 31.9 |

| Int. migrant networks | 4.5 | 4.4 | 7.4 |

| Urbanization | |||

| Population <2,500 | 21.7 | 21.5 | 42.9 |

| Population 2,500 to 14,999 | 12.2 | 12.2 | 15.8 |

| Population 15,000 to 99,999 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 11.8 |

| Populations ≥ 100,000 | 54.9 | 55.3 | 29.5 |

| Region | |||

| Historic region | 22.0 | 21.7 | 40.7 |

| Border region | 18.4 | 18.4 | 13.6 |

Notes: The sample is weighted. All values are percentages of the corresponding group unless otherwise noted.

Descriptive Results

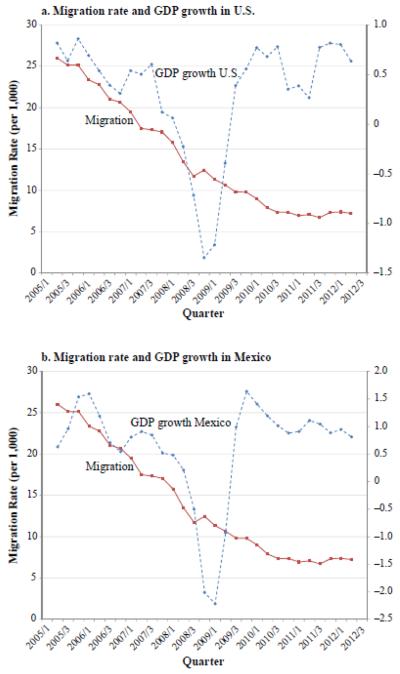

Panel a of Fig. 1 shows the annual rate of international migration for Mexican men along with the GDP growth rate in the United States from 2005 to 2012. Each data point in the migration series (scaled on the left axis) represents the total number of migrants per thousand residents for the year that begins in each quarter, rather than the quarterly rate, to avoid seasonal fluctuations. A three-quarter moving average is also used to further smooth short-term fluctuations. The international migration rate indeed declined dramatically from 26.2 to 6.3 migrants per thousand between the first quarter of 2005 and the third quarter of 2012, the most recent quarter for which information is available (a decrease of 76 % in less than seven years).11 In addition, no clear relation is evident between the decline in economic growth during the U.S. recession and the international migration rate from Mexico. The migration rate began to fall before the recession officially started in 2008 and continued its downward trend even after the economy began to recover in 2009 (the correlation between the two series is 0.13). Panel b of Fig. 1 superimposes the international migration rate with the overall GDP growth in Mexico. Again, no simple relation is detectable between aggregate growth in Mexico and international migration (r = .11). The migration rate seems to be unaffected by the Mexican recession, which began slightly after the U.S. recession and ended earlier.

Fig. 1.

International migration rate from Mexico and GDP growth in the United States (panel a) and Mexico (panel b)

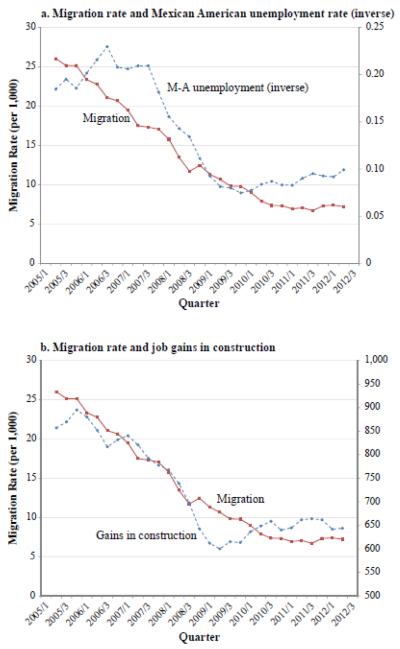

Figure 2 compares trends in employment in the United States (scaled on the right axis) with the international migration rate (scaled on the left axis). In contrast to the lack of association between the overall growth of the U.S. economy and international migration, these figures generally indicate a strong relation between the specific labor market conditions and the rate of migration. First, panel a of Fig. 2 shows the international migration rate along with the inverse of the unemployment rate for Mexican American men. The association between these two variables is very strong (r = .90). Although the decline in migration seems to predate the increase in unemployment in late 2007, the annual migration rate is a leading indicator because it measures migration over the year that begins in each quarter (economic indicators are not lagged in these graphs). Panel b shows an even stronger association between job gains in the construction sector in the United States and the international migration rate from Mexico (r = .94).

Fig. 2.

International migration rate as it relates to the Mexican-American unemployment rate (inverse) (panel a) and job gains in construction (panel b)

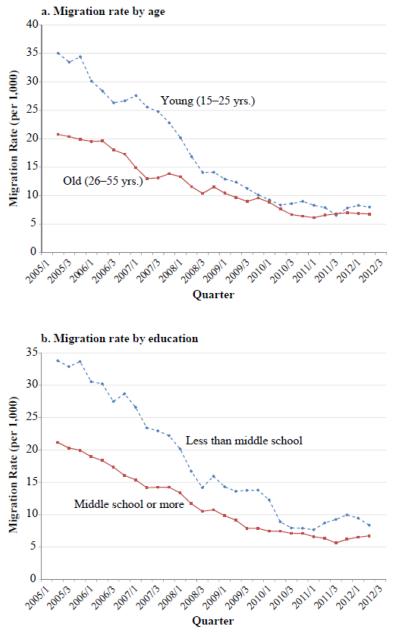

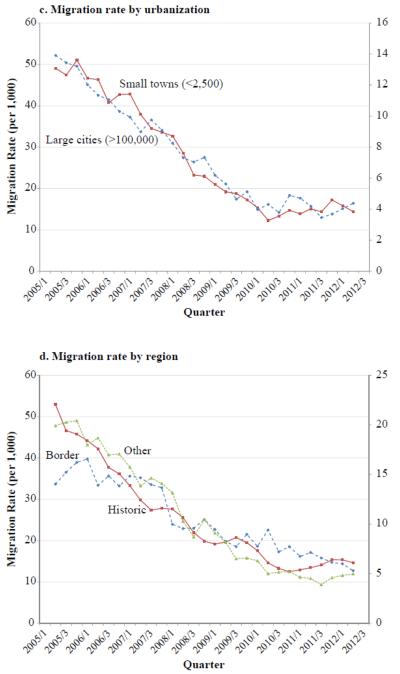

The second part of the multivariate analysis examines changes in the selectivity of migrants over time. To illustrate these changes, Fig. 3 shows the rate of migration for Mexican men according to their age, education, and level of urbanization, and the region of the country in which they reside. Panel a shows a clear shift in the selectivity of migrants by age. Although young men (ages 15 to 25) were 69 % more likely to migrate than older men (ages 26 to 55) in early 2005, the migration rates for men in the two age groups were nearly identical by late 2009. A similar but less dramatic change in the selectivity of migrants by educational attainment is observed in panel b of Fig. 3. Men with less than a middle school education were more likely to migrate than those with a middle school education or more throughout the period considered. However, the decline in the annual migration rate for the less-educated group was larger than that for the more-educated group. By contrast, no changes in selectivity are visible by level of urbanization or region of the country. To highlight the similarity in the selectivity changes over time, the migration rates for men from small towns and for men from the historic region are scaled on a different axis in panels c and d, respectively. These two groups have much higher migration rates overall, but they experienced a nearly identical proportional decrease in migration during this period than men from the other groups.

Fig. 3.

International migration rate for men by (a) age, (b) education, (c) urbanization, and (d) region

Multivariate Results

Table 3 shows the results of the random-effects logit models predicting Mexican men's odds of migrating internationally. The coefficients for the time-varying measures of economic performance in the United States support the hypothesis that employment conditions in the United States contributed to the decline in migration. Job gains in the industries that employ the largest share of Mexican workers are significantly associated with increases in the odds of international migration. Conversely, and more reflective of the changes that actually took place during this time, declines in employment in these industries are associated with decreases in the odds of migration. The effect of job losses in the top employment sector is particularly large. Based on the coefficient from Model 6, a decrease in employment gains in construction of the magnitude observed between 2005 and 2012 is associated with a 28.9 % decline in the odds of migration. Not surprisingly, given the limitations of the annual unemployment rate for Mexican-born men, it is not found to be a significant predictor of international migration, although the sign of the coefficient is in the expected direction. By contrast, an increase in the quarterly unemployment rate for Mexican American men is significantly associated with a decline in Mexican men's odds of migrating internationally.

Table 3.

Results of random effects logistic regression models predicting Mexican men's international migration

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (baseline 15 to 25 years) | ||||||

| 26 to 35 years | −0.027 (0.035) | −0.027 (0.035) | −0.027 (0.035) | −0.027 (0.035) | −0.027 (0.035) | −0.027 (0.035) |

| 36 to 45 years | −0.359** (0.040) | −0.359** (0.040) | −0.359** (0.040) | −0.360** (0.040) | −0.359** (0.040) | −0.359** (0.040) |

| 46 to 55 years | −0.939** (0.052) | −0.939** (0.052) | −0.939** (0.052) | −0.939** (0.052) | −0.939** (0.052) | −0.939** (0.052) |

| Education (baseline less than primary) | ||||||

| Complete primary | 0.205** (0.039) | 0.205** (0.039) | 0.205** (0.039) | 0.205** (0.039) | 0.205** (0.039) | 0.205** (0.039) |

| Complete middle school | 0.187** (0.039) | 0.187** (0.039) | 0.187** (0.039) | 0.187** (0.039) | 0.187** (0.039) | 0.187** (0.039) |

| Complete high school or technical degree | 0.014 (0.047) | 0.014 (0.047) | 0.014 (0.047) | 0.014 (0.047) | 0.014 (0.047) | 0.014 (0.047) |

| Complete college or more | −0.207** (0.063) | −0.207** (0.063) | −0.207** (0.063) | −0.208** (0.063) | −0.207** (0.063) | −0.207** (0.063) |

| Marital Status (baseline single) | ||||||

| Married | 0.228** (0.036) | 0.228** (0.036) | 0.228** (0.036) | 0.228** (0.036) | 0.228** (0.036) | 0.228** (0.036) |

| Cohabiting | 0.135** (0.043) | 0.135** (0.043) | 0.135** (0.043) | 0.135** (0.043) | 0.135** (0.043) | 0.135** (0.043) |

| Separated, divorced, or widowed | −0.077 (0.094) | −0.077 (0.094) | −0.077 (0.094) | −0.077 (0.094) | −0.077 (0.094) | −0.077 (0.094) |

| Born out of State | 0.168** (0.034) | 0.169** (0.034) | 0.169** (0.034) | 0.169** (0.034) | 0.169** (0.034) | 0.169** (0.034) |

| Employment (baseline not econ. active) | ||||||

| Employed informal sector | 0.309** (0.036) | 0.309** (0.036) | 0.309** (0.036) | 0.309** (0.036) | 0.309** (0.036) | 0.309** (0.036) |

| Employed formal sector | −0.354** (0.046) | −0.355** (0.046) | −0.355** (0.046) | −0.355** (0.046) | −0.355** (0.046) | −0.354** (0.046) |

| Unemployed | 0.759** (0.055) | 0.758** (0.055) | 0.758** (0.055) | 0.758** (0.055) | 0.758** (0.055) | 0.758** (0.055) |

| Household Variables | ||||||

| Number of household members | 0.091** (0.007) | 0.091** (0.007) | 0.091** (0.007) | 0.091** (0.007) | 0.091** (0.007) | 0.091** (0.007) |

| Number of children in household | −0.067** (0.013) | −0.067** (0.013) | −0.067** (0.013) | −0.067** (0.013) | −0.067** (0.013) | −0.067** (0.013) |

| Household income | −0.019** (0.002) | −0.019** (0.002) | −0.019** (0.002) | −0.019** (0.002) | −0.019** (0.002) | −0.019** (0.002) |

| Contextual Variables | ||||||

| Mean wages | −0.043** (0.003) | −0.043** (0.003) | −0.044** (0.003) | −0.043** (0.003) | −0.043** (0.003) | −0.044** (0.003) |

| Unemployment rate | 0.060** (0.010) | 0.061** (0.010) | 0.063** (0.010) | 0.062** (0.010) | 0.062** (0.010) | 0.062** (0.010) |

| Ave. age of men | −0.124** (0.033) | −0.127** (0.033) | −0.130** (0.033) | −0.130** (0.033) | −0.129** (0.033) | −0.130** (0.033) |

| Int. migrant networks | 0.039** (0.002) | 0.039** (0.002) | 0.039** (0.002) | 0.039** (0.002) | 0.039** (0.002) | 0.039** (0.002) |

| Urbanization (baseline <2,500) | ||||||

| Population 2,500 to 14,999 | −0.259** (0.036) | −0.260** (0.036) | −0.260** (0.036) | −0.259** (0.036) | −0.259** (0.036) | −0.259** (0.036) |

| Population 15,000 to 99,999 | −0.468** (0.044) | −0.467** (0.044) | −0.467** (0.044) | −0.467** (0.044) | −0.467** (0.044) | −0.467** (0.044) |

| Population ≥ 100,000 | −0.755** (0.033) | −0.754** (0.033) | −0.754** (0.033) | −0.754** (0.033) | −0.754** (0.033) | −0.753** (0.033) |

| Region | ||||||

| Historic region | 0.519** (0.031) | 0.518** (0.031) | 0.517** (0.031) | 0.517** (0.031) | 0.518** (0.031) | 0.518** (0.031) |

| Border region | 0.347** (0.044) | 0.349** (0.044) | 0.351** (0.044) | 0.351** (0.044) | 0.351** (0.044) | 0.352** (0.044) |

| Economic Conditions | ||||||

| GDP growth rate in United States | 0.059 (0.043) | 0.100* (0.049) | 0.079* (0.040) | −0.041 (0.053) | −0.020 (0.050) | 0.001 (0.045) |

| Mexican-born unemployment rate (annual) | −0.025 (0.016) | |||||

| Mexican-American unemployment rate | −0.039** (0.015) | |||||

| Employment gains in top 5 sectors | 0.040** (0.014) | |||||

| Employment gains in top 3 sectors | 0.079** (0.030) | |||||

| Employment gains in top sector (construction) | 0.192** (0.069) | |||||

| Border Enforcement | ||||||

| Staffing in Southwest sector | −0.125** (0.007) | −0.103** (0.016) | −0.093** (0.014) | −0.087** (0.015) | −0.086** (0.016) | −0.076** (0.019) |

| Constant | 1.819 (1.018) | 1.811 (1.018) | 1.547 (1.024) | 1.466 (1.026) | 1.447 (1.028) | 1.315 (1.035) |

| N | 622,869 | 622,869 | 622,869 | 622,869 | 622,869 | 622,869 |

p < .05;

p < .01 (two-tailed tests)

Interestingly, the overall growth in GDP is not significantly associated with changes in the odds of migration, suggesting that such changes are driven specifically by labor demand, particularly in sectors of the U.S. economy employing the largest share of Mexican immigrants. The effect of employment gains is also net of the local economic conditions in Mexico. The coefficients for the unemployment rate and mean wages in Mexican communities nevertheless suggest that improving economic conditions at home decrease the odds of migration: a lower unemployment rate and higher average wages are both significantly associated with lower migration rates. The effect of job gains in the top industries employing Mexican-born workers is also net of changes in border enforcement. A greater number of Border Patrol agents assigned to the Southwest sector is generally associated with lower odds of international migration, but does not account for the effect of lower labor demand. Based on the coefficient from Model 6, an increase in border enforcement staff of the magnitude observed between 2005 and 2012 is associated with a 49.5 % decline in the odds of migration.

Changes in the age structure and household size, which could be attributed to the long-term decline in fertility, were small. Older men, as well as men living in small households and in households with fewer children, were less likely to migrate.12 However, changes in both the age of men and the household size during this eight-year period were small. The average age of men increased by 0.62 years, and the average number of household members and children per household declined by only 0.23 and 0.13, respectively. Taken together, changes in these three variables account for only a 3.2 % decrease in the odds of migration between 2005 and 2012. The effect of changes in the mean age of men in the communities of origin is also small, accounting for an 8.1 % decrease in the odds of migration.

The coefficients for the remaining variables are generally consistent with expectations. Men's odds of international migration generally decline with education. However, the decline is not quite linear. Men who have completed primary or middle school have the highest odds of migrating abroad. Married and cohabiting men, who have a greater need to support a family at home, had significantly higher odds of migrating internationally. Men employed in the informal sector were significantly more likely to migrate than those employed in the formal sector, while those who were unemployed were the most likely to migrate. Men living in households with higher income levels were significantly less likely to migrate. Finally, the odds of international migration were significantly lower for men from more urban areas as well as for those living outside the historic migration region and the border states.

Changes in Selectivity

The second objective of this study is to examine changes in the selectivity of international migrants from Mexico during the period of declining migration, and to test specifically how changes in selectivity are tied to worsening economic conditions in the United States. To this end, Table 4 compares the results of the same random-effects logit models estimated separately for the period before and after the onset of the recession that began in the first quarter of 2008.13 The last column in Table 4 tests the statistical significance of the difference in coefficients between the two periods. The results indicate some clear changes in migrant selectivity in the years following the recession. First, migrants became less negatively selected by age. Older men were still significantly less likely to migrate than younger men after the onset of the recession, but the difference in the odds of migration between older and younger men became smaller. For example, whereas men ages 36 to 45 before the recession had 40.1 % lower odds of migrating than those ages 15 to 25, the odds of migrating for the former were only 13.1 % lower after the recession. Second, migrants also became more positively selected by education. The odds of migrating increased significantly for men with completed middle school, high school, and college or more, relative to those with less than a primary school education. These changes in the age and educational selectivity of Mexican migrants are consistent with an explanation that attributes the decline in migration to worsening economic conditions in the United States because the U.S. economic recession disproportionately affected the employment prospects for young men with low education (Bell and Blanchflower 2011; Elsby et al. 2010; Pew Economic Mobility Project 2013). Similarly, the results of the regression models in Table 3 show a significant decrease in the odds of migration for men who were economically active compared with those who were not active, which is also consistent with an economic explanation for the overall decline in international migration.

Table 4.

Results of random effects logistic regression models predicting Mexican men's international migration before and after the onset of U.S. recession

| Before | After | difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (baseline 15 to 25 years) | |||

| 26 to 35 years | −0.127** (0.045) | 0.119* (0.054) | ** |

| 36 to 45 years | −0.513** (0.052) | −0.140* (0.062) | ** |

| 46 to 55 years | −1.174** (0.071) | −0.637** (0.078) | ** |

| Education (baseline less than primary) | |||

| Complete primary | 0.185** (0.049) | 0.244** (0.065) | |

| Complete middle school | 0.119* (0.050) | 0.302** (0.064) | * |

| Complete high school or technical degree | −0.085 (0.061) | 0.170* (0.075) | ** |

| Complete college or more | −0.496** (0.087) | 0.143 (0.092) | ** |

| Marital status (baseline single) | |||

| Married | 0.255** (0.047) | 0.203** (0.056) | |

| Cohabiting | 0.248** (0.057) | 0.002 (0.067) | ** |

| Separated, divorced, or widowed | −0.046 (0.129) | −0.123 (0.139) | |

| Born out of state | 0.087 (0.045) | 0.278** (0.051) | * |

| Employment (baseline not econ. active) | |||

| Employed informal sector | 0.381** (0.048) | 0.206** (0.055) | * |

| Employed formal sector | −0.221** (0.059) | −0.551** (0.071) | ** |

| Unemployed | 0.937** (0.075) | 0.551** (0.080) | ** |

| Household Variables | |||

| Number of household members | 0.080** (0.009) | 0.105** (0.011) | |

| Number of children in household | −0.037* (0.017) | −0.116** (0.021) | ** |

| Household income | −0.014** (0.003) | −0.025** (0.003) | * |

| Contextual Variables | |||

| Mean wages | −0.049** (0.005) | −0.036** (0.005) | |

| Unemployment rate | 0.052** (0.014) | 0.067** (0.014) | |

| Ave. age of men | −0.077 (0.043) | −0.209** (0.050) | * |

| Int. migrant networks | 0.040** (0.002) | 0.039** (0.003) | |

| Urbanization (baseline <2,500) | |||

| Population 2,500 to 14,999 | −0.194** (0.047) | −0.354** (0.057) | * |

| Population 15,000 to 99,999 | −0.435** (0.058) | −0.522** (0.068) | |

| Population ≥ 100,000 | −0.718** (0.044) | −0.801** (0.051) | |

| Region | |||

| Historic region | 0.549** (0.040) | 0.479** (0.048) | |

| Border region | 0.342** (0.058) | 0.364** (0.069) | |

| Border Enforcement | |||

| Staffing in Southwest sector | −0.085* (0.039) | −0.120** (0.018) | |

| Constant | 0.113 (1.382) | 4.162** (1.598) | |

| N | 243,136 | 379,733 |

p < .05;

p < .01 (two-tailed tests)

Changes in Educational Selectivity with Worsening Economic Conditions in the United States

Overall, the differences in migrant selectivity before and after the onset of the recession are consistent with what we would expect as a result of worsening economic conditions in the United States: the largest declines in migration took place among younger and less-educated men, whose employment prospects worsened the most during the recession. However, the foregoing analysis relied simply on the timing of the recession. As discussed previously, declines in labor demand in various sectors of the U.S. economy did not always coincide with the onset of the recession. To more explicitly examine the effect of changes in economic conditions on migrant selectivity, I therefore tested models in which the educational attainment of Mexican men is interacted with the measures of labor demand in different sectors of the U.S. economy. Table 5 presents the results of these random-coefficient models in which a quarterly error term is also introduced for education. Because educational attainment is likely to be a more important predictor of the employment prospects of younger men, separate models are tested for Mexican men in the youngest age category (15 to 25 years). This is also the age group with the highest migration rate, accounting for 43.5 % of all international migrants during this period. To simplify the interpretation of the results of the regression models, men's educational attainment is introduced as a binary variable indicating whether an individual has completed a middle school education (secundaria). However, results for models including multiple educational categories were consistent with those presented in Table 5. To conserve space, only the coefficients for the baseline and interaction terms for education are shown in Table 5. All aggregate economic measures are centered such that the baseline coefficients may be interpreted as the effect of having a middle school education or more, evaluated at the mean of the corresponding economic measure for the entire period.

Table 5.

Results of random effects logistic regression models interacting U.S. labor market conditions with educational attainment of Mexican men

| All Men |

Young Men |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Education | ||||||

| Completed middle school or more | −0.004 (0.029) | −0.003 (0.029) | 0.000 (0.029) | 0.111* (0.053) | 0.114* (0.053) | 0.119* (0.053) |

| Economic Conditions | ||||||

| Employment gains in top 5 sectors | 0.053** (0.015) | 0.067** (0.024) | ||||

| Employment gains in top 3 sectors | 0.105** (0.031) | 0.132** (0.049) | ||||

| Employment gains in top sector (construction) | 0.251** (0.071) | 0.307** (0.113) | ||||

| Interactions with Education | ||||||

| Complete middle school × Emp. gains in top 5 sectors | −0.016* (0.007) | −0.028* (0.012) | ||||

| Complete middle school × Emp. gains in top 3 sectors | −0.033* (0.013) | −0.059* (0.025) | ||||

| Complete middle school × Emp. gains in top sector | −0.075** (0.027) | −0.131* (0.052) | ||||

| N | 622,869 | 622,869 | 622,869 | 228,360 | 228,360 | 228,360 |

Notes: Models include all predictors shown in the baseline models in Table 3. Other coefficients are not shown to conserve space.

p < .05;

p < .01 (two-tailed tests)

The results of the models for men of all ages show significant changes in educational selectivity with changing labor market demand. The changes in educational selectivity are even larger when the sample is restricted to only young men. The significant negative interaction between job gains in the top employment sectors and men's educational attainment indicate that employment gains led to a more negative educational selectivity. Conversely, a decline in employment, such as that observed since the mid-2000s, led to a more positive educational selectivity of Mexican migrants (i.e., the odds of migrating for more-educated Mexican men increased relative to the odds of the less-educated). This last finding makes sense because the top industrial sectors employ a disproportionate number of low-skilled immigrant workers.

Conclusions

The rate of Mexican migration to the United States has declined dramatically over the past decade. From a high of 25 migrants per thousand residents in 2005, the annual international migration rate from Mexico dropped to 7 per thousand by 2012. If sustained, this low migration rate is likely to have a profound effect on the ethnic and national-origin composition of the U.S. population. The lower migration rate may also have significant implications for labor markets on both sides of the border. It is therefore critically important to understand the origins of this decline in migration. The results of the statistical analysis presented in this article indicate that worsening employment opportunities for Mexican immigrants in the United States contributed significantly to the decline in migration. The recent recession resulted in a severe contraction in key sectors of the U.S. economy that employ a disproportionate number of migrants. Decreases in labor demand in these sectors were found to be strongly associated with lower rates of migration for Mexican men. In addition, the changes in migrant selectivity during this period are also consistent with an economic explanation for the decline in international migration. The largest declines in migration occurred precisely among the demographic groups most affected by the recession: namely, economically active young men with low levels of educational attainment.

Lower labor demand in the United States is not the only possible explanation for the decline in Mexican migration. I also found particularly strong support for the explanation that attributes lower migration rates to increases in border enforcement. To a lesser extent, I also found supporting evidence for explanations that attribute the decline in migration to improvements in the Mexican economy and to changes in the demographic structure of the Mexican population resulting from the long-term decline in fertility. None of these explanations by themselves are able to account for the timing and severity of the decline in Mexico-U.S. migration since the mid-2000s. Although increasing border enforcement is significantly associated with lower migration rates, the increase in border enforcement staffing predates the onset of the decline in migration by more than a decade. Economic conditions in Mexico simply did not improve sufficiently to warrant such a large decrease in international migration. Finally, the direct effect of changes in the age and household structure of the Mexican population over the period considered is too small to explain the sharp migration decline over a relatively short period.

My analysis of the effect of U.S. economic conditions on Mexican migration was made possible by a unique survey, the ENOE. No other survey has such detailed information regarding Mexican men's migration decisions since the mid-2000s, gathered on a quarterly basis from a nationally representative sample of households. One limitation of the ENOE, however, is that it does not distinguish the legal status of migrants. Because the economic recession is likely to have had an even larger effect on individuals migrating without legal documentation, the statistical models provide a lower-bound estimate of the effect of employment conditions on undocumented migration. This problem is partly mitigated by this study's exclusive focus on men, who are much more likely to migrate without documentation (Cerrutti and Massey 2004). Evidence from other sources suggest that although documented migration has increased relative to undocumented migration, a vast majority of Mexican men who migrate to the United States continue to do so without legal documentation. Results from the National Survey of Demographic Dynamics (Encuesta Nacional de la Dinámica Demográfica, ENADID) indicate that 89.1 % of men who migrated to the United States from 2001 to 2006 did so without legal documentation, compared with 86.8 % of men migrating in the period from 2004–2009.14

Understanding the causal origins of the decline in migration from Mexico is important because it may tell us something about future trends. If the decline is primarily a result of worse employment prospects for migrants as a consequence of the U.S. recession, then Mexican migration may be expected to pick up again as the economy recovers. If, on the contrary, the decline is due to more permanent changes in the Mexican economy or demographic changes that are not easily reversible (such as fertility changes), then the migration rate may be expected to remain low. So far, migration rates do not appear to be bouncing back with improvements in the U.S. labor market. The descriptive figures continue to show low levels of migration despite a modest recovery in employment levels in the top employment sectors for Mexican-born men after 2009. It is possible that the improvements in the employment prospects for migrants in the wake of the recession are still too small, or that it may take some time for information about better labor market conditions to travel back to communities of origin. Alternatively, the divergence between the trends in employment and migration for later quarters might suggest that there are other factors counteracting the effect of improving labor market conditions. In particular, immigration law enforcement efforts may be playing a critical role in maintaining low migration levels from Mexico. Other factors not considered in this study may have also contributed to the discrepancy between employment conditions and migration observed in the most recent quarters. For example, the growth of anti-immigrant sentiment in the United States as well as the enactment of state and local-level ordinances restricting immigrants' rights (Steil and Vasi 2014) could have dissuaded Mexican men from migrating. Similarly, the increasing danger of crossing the border due to extortion and kidnappings at the hands of Mexican criminal organizations could also have inhibited migration (Amnesty International 2010; CNDH 2011).

However, migration trends tend to be sticky. Even if the decline in migration was due to lower employment opportunities, Mexican migration could remain low even after the demand for immigrant labor recovers if social mechanisms have been put into place that reinforce a low migration regime. This is one of the fundamental insights of cumulative causation theory, now applied in reverse. Social norms that made migration a rite of passage for young rural men in traditional sending communities in Mexico could weaken and be replaced by norms discouraging migration, but only if migration rates remain low for an extended period.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (1 R03-HD080774). A version of this article was presented at the Population Association of America 2014 Annual Meeting, in Boston, MA.

Footnotes

Line-watch hours are obtained from the Mexican Migration Project National Level Supplementary Files (retrieved from http://mmp.opr.princeton.edu/databases/supplementaldataen.aspx).

I also tested models using three alternative measures of immigration law enforcement. See the supplemental Online Resource 1 for a discussion of these alternative measures.

See footnote 4 for results of regression models for Mexican women.

During the period considered, women accounted for 21.1 % of all international migrants but only 12.6 % of migrants moving for work reasons. I tested the models presented in Table 3 using the sample of women in the ENOE. Women's odds of migrating increased significantly with the overall rate of growth in GDP. However, women's migration decisions were unaffected by specific labor market conditions in the United States.

The association between the economic indicators and the odds of migrating was found to be even stronger when shorter lags were used. For example, models that used the average employment levels during the previous year resulted in larger and more significant coefficients than those using average employment levels from two years before, suggesting that potential migrants are reacting rather quickly to changes in employment conditions.

Information for earlier and later years is not currently available from the U.S. Census Bureau (2007).

Although the percentage of workers employed in the top three sectors declined slightly between 2006 and 2011, the relative ranking of the top five employment sectors remained unchanged. Moreover, a further examination of the raw number of Mexican-born male workers employed in all sectors does not indicate that a decrease in employment in these top sectors was being compensated by increases in employment in other sectors. Changes in job gains in the top five sectors is therefore a good proxy for labor demand for Mexican immigrants.

Details of the BDM series are available online (http://www.bls.gov/bdm/).

Information on Border Patrol staffing was retrieved online from the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (http://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/documents/U.S.%20Border%20Patrol%20Fiscal%20Year%20Staffing%20Statistics%201992–2013.pdf).

See Lindstrom and Lauster (2001), Hamilton and Villarreal (2011), and Villarreal and Blanchard (2013) for the use of this type of measure. Return migrants are all those who were living abroad five years prior to the census.

This decline in migration is roughly consistent with previous estimates by Passel et al. (2012: Table A2). Combining data from various sources, they estimated a decline in the total number of migrants form 550,000 in 2005 to 140,000 in 2010. This is equivalent to a decline of 76.6 % when adjusted for the slight increase in the size of the Mexican population during the same time period.

The effect of an additional child is given by the sum of the coefficient for the number of household members and the coefficient for the number of children.

I also tested alternative models comparing the three years before the recession (2005–2007) to the three years during the recession (2008–2010). The results were consistent with those presented in Table 4, specifically with respect to the changes in selectivity of migrants by age, education, and employment status.

Author's calculations using the two samples.

References

- Amnesty International . Invisible victims: Migrants on the move in Mexico. Amnesty International Publications; London, UK: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bell DNF, Blanchflower DG. Young people and the great recession. Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 2011;27:241–267. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas GJ. The economic analysis of immigration. In: Ashenfelter OC, Card D, editors. Handbook of labor economics. Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 1999. pp. 1697–1760. [Google Scholar]

- Business Cycle Dating Committee, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Determination of the December 2007 peak in economic activity. NBER; Cambridge, MA: 2008. Report. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/cycles/dec2008.html. [Google Scholar]

- Cerrutti M, Massey DS. On the auspices of female migration from Mexico to the United States. Demography. 2001;38:187–200. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerrutti M, Massey DS. Trends in Mexican migration to the United States, 1965 to 1995. In: Durand J, Massey DS, editors. Crossing the border: Research from the Mexican Migration Project. Russell Sage; New York, NY: 2004. pp. 17–44. [Google Scholar]

- Chiquiar D, Hanson GH. International migration, self-selection, and the distribution of wages: Evidence from Mexico and the United States. Journal of Political Economy. 2005;113:239–281. [Google Scholar]

- Chiquiar D, Salcedo A. Mexican migration to the United States: Underlying economic factors and possible scenarios for future growth. Migration Policy Institute; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social (CONEVAL) Informe de pobreza de México: El país, los estados y sus municipios [Report of poverty in Mexico: The country, the states and their municipalities] CONEVAL; Mexico: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo Nacional de los Derechos Humanos (CNDH) Informe especial sobre secuestro de migrantes en México [Special report on kidnapping of migrants in Mexico] CNDH; Mexico: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius WA. Efficacy and unintended consequences of US immigration control policy. Population and Development Review. 2001;27:661–685. [Google Scholar]

- Curran SR, Rivero-Fuentes E. Engendering migrant networks: The case of Mexican migration. Demography. 2003;40:289–307. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis B, Stecklov G, Winters P. Domestic and international migration from rural Mexico: Disaggregating the effects of network structure and composition. Population Studies. 2002;56:291–309. [Google Scholar]

- Donato KM. Current trends in and patterns of female migration: Evidence from Mexico. International Migration Review. 1993;27:748–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato KM, Patterson E. Women and men on the move: Undocumented border crossing. In: Durand J, Massey DS, editors. Crossing the border: Research from the Mexican Migration Project. Russell Sage; New York, NY: 2004. pp. 111–130. [Google Scholar]

- Donato KM, Wagner B, Patterson E. The cat and mouse game at the Mexico-U.S. border: Gendered patterns and recent shifts. International Migration Review. 2008;42:330–359. [Google Scholar]

- Durand J, Massey DS, Zenteno RM. Mexican immigration to the United States: Continuities and changes. Latin American Research Review. 2001;36:107–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsby MW, Hobijn B, Şahin A. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. Spring. 2010. The labor market in the Great Recession; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Espenshade TJ. Does the threat of border apprehension deter undocumented US immigration? Population and Development Review. 1994;20:871–892. [Google Scholar]

- Fix M, Papademetriou DG, Batalova J, Terrazas A, Lin SY, Mittelstadt M. Migration and the global recession. Migration Policy Institute; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fussell E. Sources of Mexico's migration stream: Rural, urban, and border migrants to the United States. Social Forces. 2004;82:937–967. [Google Scholar]

- Fussell E, Massey DS. The limits to cumulative causation: International migration from Mexican urban areas. Demography. 2004;41:151–171. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genoni M, Rubalcava L, Teruel G, Thomas D. Mexicans in America. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Population Association of America; San Francisco, CA. May, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman CJ, Mance SM. Monthly Labor Review. Apr, 2011. Employment loss and the 2007–09 recession: An overview; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Grieco EM, Acosta YD, de la Cruz GP, Gambino C, Gryn T, Larsen LJ, Walters NP. The foreign-born population in the United States: 2010 (American Community Survey Reports ACS-19) U.S. Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2012. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2012pubs/acs-19.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi A. Monthly Labor Review. Apr, 2011. Construction employment peaks before the recession and falls sharply throughout it; pp. 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton EH, Villarreal A. Development and the urban and rural geography of Mexican emigration to the United States. Social Forces. 2011;90:661–683. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson GH. Illegal migration from Mexico to the United States. Journal of Economic Literature. 2006;44:869–924. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson GH, McIntosh C. Demography of Mexican migration to the United States. American Economic Review. 2009;99:22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson GH, McIntosh C. The great Mexican emigration. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2010;92:798–810. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson GH, McIntosh C. Birth rates and border crossings: Latin American migration to the US, Canada, Spain and the UK. The Economic Journal. 2012;122:707–726. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson GH, Spilimbergo A. Illegal immigration, border enforcement, and relative wages: Evidence from apprehensions at the U.S.-Mexico border. American Economic Review. 1999;89:1337–1357. [Google Scholar]

- Ibarraran P, Lubotsky D. Mexican immigration and self-selection: New evidence from the 2000 Mexican census. In: Borjas GJ, editor. Mexican migration to the United States. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 2007. pp. 159–192. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI) Encuesta nacional de ocupación y empleo, ENOE 2009 [National occupation and employment survey, ENOE 2009] INEGI; Aguascalientes, Mexico: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kanaiaupuni SM. Reframing the migration question: An analysis of men, women, and gender in Mexico. Social Forces. 2000;78:1311–1347. [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom DP, Lauster N. Local economic opportunity and the competing risks of internal and U.S. migration in Zacatecas, Mexico. International Migration Review. 2001;35:1232–1256. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS. Social structure, household strategies, and the cumulative causation of migration. Population Index. 1990;56:3–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS. Pathways. Fall. 2012. The great decline in American immigration? pp. 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Alarcón R, Durand J, González H. Return to Aztlán: The social process of international migration from western Mexico. University of California Press; Berkeley: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Arango J, Hugo G, Kouaouci A, Pellegrino A, Taylor JE. An evaluation of international migration theory: The North American case. Population and Development Review. 1994b;20:699–751. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Durand J, Malone NJ. Beyond smoke and mirrors: Mexican migration in an era of economic integration. Russell Sage; New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Espinosa KE. What's driving Mexico-U.S. migration? A theoretical, empirical, and policy analysis. American Journal of Sociology. 1997;102:939–999. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Goldring L, Durand J. Continuities in transnational migration: an analysis of nineteen Mexican communities. American Journal of Sociology. 1994a;99:1492–1533. [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Pren KA. Unintended consequences of US immigration policy: Explaining the post-1965 surge from Latin America. Population and Development Review. 2012;38:1–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2012.00470.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS, Riosmena F. Undocumented migration from Latin America in an era of rising U.S. enforcement. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2010;630:294–321. doi: 10.1177/0002716210368114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie D, Rapoport H. Self-selection patterns in Mexico-U.S. migration: The role of migration networks. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2010;92:811–821. [Google Scholar]

- Orrenius PM, Zavodny M. Self-selection among undocumented migrants from Mexico. Journal of Development Economics. 2005;78:215–240. [Google Scholar]

- Passel J, D'Vera C, Gonzalez-Barrera A. Net migration from Mexico falls to zero— and perhaps less. Pew Hispanic Center Report; Washington, DC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Economic Mobility Project . How much protection does a college degree afford? The impact of the recession on recent college graduates. Pew Charitable Trust; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rivero-Fuentes E. Cumulative causation among internal and international Mexican migrants. In: Durand J, Massey DS, editors. Crossing the border: Research from the Mexican Migration Project. Russell Sage; New York, NY: 2004. pp. 201–231. [Google Scholar]

- Romo Viramontes R, Sánchez Castillo M. [The decrease in fertility in Mexico, 1974–2009: 35 years after the start of the new population policy] In La situación demográfica de México 2009 [The demographic situation in Mexico] Consejo Nacional de Población; Mexico: 2009. El descenso de la fecundidad en México, 1974–2009: A 35 años de la puesta en marcha de la nueva política de población; pp. 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Steil JP, Vasi IB. The new immigration contestation: Social movements and local immigration policy making in the United States, 2000–2011. American Journal of Sociology. 2014;119:1104–1155. doi: 10.1086/675301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todaro MP. A model of labor migration and urban unemployment in less developed countries. American Economic Review. 1969;59:138–148. [Google Scholar]

- Todaro MP, Maruszko L. Illegal migration and us immigration reform: A conceptual framework. Population and Development Review. 1987;13:101–114. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau . Current Population Survey data on the foreign-born population. U.S. Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2007. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/population/foreign/data/cps.html. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Homeland Security . U.S. Border Patrol Program budget fiscal year 1990–2012. Washington, DC: 2012. Retrieved from http://www.cbp.gov/xp/cgov/border_security/border_patrol/usbp_statistics/usbp_fy12_stats/ [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal A, Blanchard S. How job characteristics affect international migration: The role of informality in Mexico. Demography. 2013;50:751–775. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0153-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.