Abstract

Humans cross-culturally find infant faces both cute and highly likeable. Their so called “baby schema” features have clear adaptive value by likely serving as an innate releasing mechanism which elicits caretaking behaviors from adults. However, we do not know whether experience with young children during social development might act to further facilitate this. Here we investigated the potential impact of having siblings on adult likeability judgments of children’s faces. In this study, 73 adult males and females (40 with siblings and 33 without) were shown 148 different face pictures of young children (1 month to 6.5 years) and judged them for likeability. Results showed that both groups found faces of infants (<7 months) as equally likeable. However, for faces greater than 7 months of age, while the no-sibling group showed a reduced liking for faces with increasing age, the sibling group found faces of all ages as equally likeable. Further, for adults with siblings, the closer in age they were to their siblings, the stronger their likeability for young children’s faces. Our results are the first to show that having siblings can extend the influence of baby schema to children as well as infants.

Keywords: baby schema, infant faces, children’s faces, siblings, likeability, rearing experience

Introduction

Among all the social stimuli we encounter in our environment, some have special privileged status in that they particularly engage the attention of other conspecifics due to their adaptive significance (Öhman & Mineka, 2001; Taylor, 1999). The faces of young children are an example of this. Lorenz first proposed the concept of Kindchenschema (or baby schema), a set of specific visual features common to babies which adults find attractive and elicit strong protective responses (Lorenz, 1943). These features include a large head, round face, big eyes, small nose and mouth, and high, prominent forehead, which act as an innate releasing mechanism to evoke positive emotional reactions and caretaking behaviors (Glocker, Langleben, Ruparel, Loughead, Gur, & Sachser, 2009; Lobmaier, Sprengelmeyer, Wiffen, & Perrett, 2010; Lorenz, 1943; Luo, Lee, & Li, 2011), and thereby aid a young child’s survival (Parsons, Young, Murray, Stein, & Kringelbach, 2010).

Many studies have established the positive effects of facial baby schema with infants displaying these features rated to be cuter, healthier, friendlier, and more attractive and adoptable (Chin, Wade, & French, 2006; Karraker & Stern, 1990; Ritter, Casey, & Langlois, 1991). Few studies worked on child faces with these effects. Recent evidence then suggests that this baby schema effect can extend beyond infant faces to those of children up to 4.5 years of age (Luo, et al., 2011). After 4.5 years, however, we treat faces of children similarly to those of adults, suggesting that by middle preschool years, baby schema features eliciting innate responses may have become less prominent due to facio-cranial growth (Luo, et al., 2011). In the present study, we also focused on the effects of baby schema as well as its extending to child faces.

Moreover, to date no research has investigated whether early social experience plays any role in the extent to which we find young children’s faces likeable and therefore display protective and caretaking responses towards them. Our face processing ability is generally known to be highly susceptible to the influence of early experience (Pascalis, de Haan, & Nelson, 2002; Lee, Quinn, Pascalis, & Slater, 2013). Additionally, a study examining experiential effects on perceptions of resemblance showed that actively caring for one’s infant (via infant massage) increases paternal perceptions of parent-infant resemblance when compared to a control group (Volk, Darrell-Cheng, Marini, 2010). More relevant to the present study, several studies found that the experience of being raised together with a sibling would influence face recognition expertise (Macchi Cassia, Kuefner, Picozzi, & Vescovo, 2009; Macchi Cassia, 2011). For example, new mothers who had siblings showed expert recognition for infant faces, whereas those without siblings did not. These findings suggest that experience gained with sibling faces as children resulted in long-lasting effects which could be revived in adulthood (Macchi Cassia, et al., 2009). Additionally, evidence suggests that being raised together with a sibling in childhood has other advantages in terms of improved social cognition (McAlister & Peterson, 2013) and maturity (Hasnain & Adlakha, 2012). On the other hand, parents’ judgments of their own children are influenced by the birth-order. For example, they significantly underestimated their youngest children’s heights, whereas their estimates of the elder siblings were generally accurate (Kaufman, Tarasuik, Dafner, Russell, Marshall, & Meyer, 2014). The number of siblings also has influence on such measures as IQ, educational attainment, status of current job, and current earnings (Heer, 1985). Recent studies have further revealed a number of sibling effects, such as the influence of birth order on gender identity (VanderLaan, Blanchard, Wood, & Zucker, 2014), sibling age and age difference on social understanding (Taumoepeau, & Reese, 2014), and sibling influence on status attainment (Zhang, 2014).

Given the importance of sibling experience outlined above, our hypothesis here was that experience with a sibling may influence how the baby schema was manifested and therefore adults raised together with a sibling would show not only the typical baby schema effect, but also extending effect to child faces. More specifically, we hypothesized that those with siblings may like baby faces the same as those without, but for young children’s faces they may show higher likeability regardless of the normal gradual decrease with face age.

To test this hypothesis we gave adults with and without siblings a large number of face pictures of different aged infants and young children, and asked them to judge their likeability. To test this hypothesis further, we examined the effects of the age difference between the adults and their siblings, the number of siblings, and sibling sex on their likeability judgments of young children’s faces. Meanwhile, studies showed perceived age could influence peoples’ judgments on faces. For example, the more attractive faces were, the younger they were perceived as (Tatarunaite, Playle, Hood, Shaw & Richmond, 2005). To test whether this hypothesis of difference between those with siblings and without siblings on likeability judgments was related to perceived age, we then asked them to judge the age of the faces as well.

Method

Participants

Seventy-three single Chinese undergraduate students (35 males, M = 21.26 years, SD = 1.44, range = 18–25) participated. None had children of their own or worked with infants and children. Forty participants (18 males, M = 21.45, SD = 1.48) had siblings (22 males, 32 females; M = 21.63, SD = 14.65, range = 11–32), of whom thirty-one had one sibling, six had two, one had three and two had four. Eighteen of those participants had older siblings, eighteen of those had younger siblings, and four of those had both older and younger siblings. Their siblings did not participate in the study. The age difference between participants and siblings ranged from 1 to 10 years (M = 3.80, SD = 2.16). All participants with siblings reported that they had been raised together with them in the same household until their entry to the university, whereas the no-sibling participants were all raised in households where they were the only child.

Face stimuli

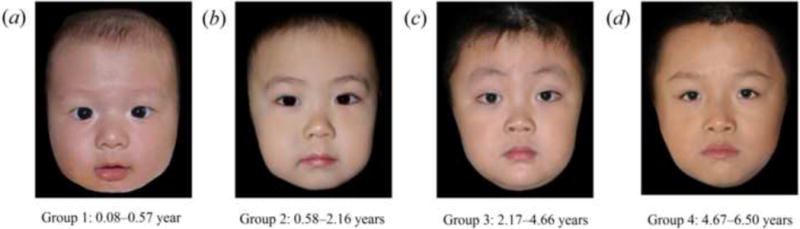

Face pictures were 148 images (pixel size: 210×300) of male and female Chinese children ranging from 1 month to 6.5 years old from an existing database. Faces were presented in color and centered on a black background (Fig. 1). All faces had neutral emotional expressions, confirmed by an additional group of 36 adult raters (for details, see Luo, et al., 2011).

Fig. 1.

Examples of children’s faces in four different age groups: (a) Face Age Group 1 (M=0.30 years, SD=0.09, age range=0.08–0.57 year), (b) Face Age Group 2 (M=1.57 years, SD=0.52, age range=0.58–2.16 years), (c) Face Age Group 3 (M=3.67 years, SD=0.83, age range=2.17–4.66 years), to (d) Face Age Group 4 (M=5.48 years, SD=0.55, age range=4.67–6.50 years).

Experimental procedures

Participants completed two sessions. In the first session, participants judged likeability of all the faces (“How do you like the face?”) on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (dislike it very much) to 4 (not sure) to 7 (like it very much). In the second session, they judged the age of the faces (“How old is the face?”) in years and months. In each session, participants sat 60cm away from a 17-inch LCD screen and viewed faces individually in a random order. For each trial, a fixation was first shown for 1000ms, followed by the face image for a maximum of 3000 ms. Face presentation was terminated when participants pressed the rating key and so could be <3000 ms. Participants were asked to judge as quickly and accurately as possible. Each session consisted of two blocks with a one-minute break between them.

Results

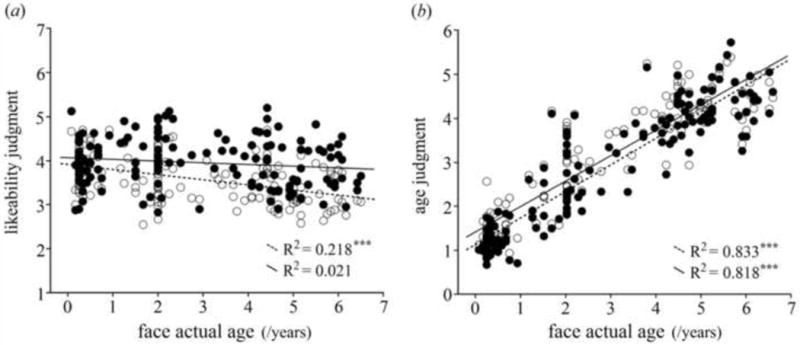

We first averaged the likeability and age judgments of all participants with or without siblings for a particular face to obtain a mean likeability score and a mean perceived age score for each face. Using these scores, we conducted linear regression analyses using the actual age of the faces as the predictor, and the likeability scores and perceived ages as the predicted variables, respectively. We did the regression analyses separately on the data from the participants with and without siblings to examine whether participants’ experience with siblings would affect their judgments of the children’s faces (Fig. 2a: likeability; Fig. 2b: perceived age). We found that the actual face age of children significantly and negatively predicted likeability judgments of participants without siblings (t = −6.37, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.22). The older the face age, the less likeable the participants judged the faces, confirming previous findings (Luo, et al., 2011). However, no significant face age effect was found for participants with siblings (t = −1.75, p = 0.082, R2 = 0.02) who failed to show a face age related decline in likeability judgments (Fig. 2a), suggesting a sibling effect on likeability judgments.

Fig. 2.

Scatter plots and regression of (a) likeability and (b) age judgments as a function of the actual ages of faces presented. Participants with siblings are represented by filled dots and a solid line with its regression value, while those without siblings are represented by unfilled dots and a dotted line. ***p < 0.001.

Additionally, the actual face age of children could significantly and positively predict the age judgments of participants (with siblings, t = 26.99, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.83; without siblings, t = 25.61, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.82). Thus, regardless of experience with siblings, the participants’ face age judgments corresponded closely with the actual age of the children’s faces, although both groups of participants tended to perceive ages of the faces as slightly older than their actual ones for infants and younger children (Fig. 2b). Thus, the sibling effect on likeability judgments may not be due to different age judgments by participants with versus without siblings.

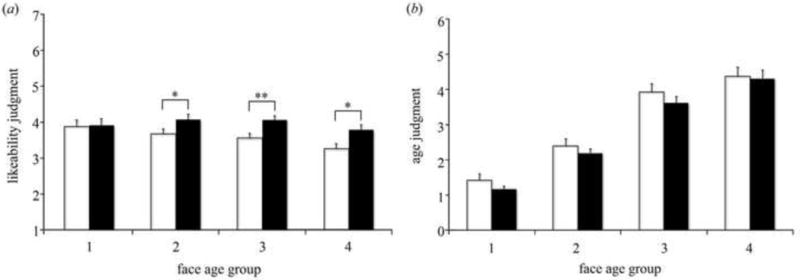

To explore the sibling effect further, we divided the children’s faces into four face age groups according to whether their actual ages fell in one of the four quartiles of the entire age range of the faces. Thus, approximately equal numbers of face images were included in each of the following four face age groups: (a) Face Age Group 1 (M=0.30, SD=0.09, age range=0.08–0.57 year) consisting of 36 faces, (b) Face Age Group 2 (M=1.57, SD=0.52, age range=0.58–2.16 years) consisting of 37 faces, (c) Face Age Group 3 (M=3.67, SD=0.83, age range=2.17–4.66 years) consisting of 37 faces, and (d) Face Age Group 4 (M=5.48, SD=0.55, age range=4.67–6.50 years) consisting of 38 faces. We used repeated measure ANOVAs with both judgments on four different face age groups as within-subject factor separately, and sibling experience as between-subjects factors. As independent sample t-test showed no significant difference between males and females (all p>0.3), we combined the data from both sexes. For likeability judgments, we found two significant main effects (age group, F(3, 213)= 8.52, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.11; sibling, F(1, 71) = 4.06, p = 0.048, η2 = 0.05), as well as a significant interaction between them, F(3, 213)=3.65, p = 0.014, η2 = 0.05. Post hoc analyses revealed that this significant effect was due to the fact that participants with siblings had significantly higher judgments of likeability than participants without siblings in each age group except for the youngest one (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

(a) Likeability and (b) age judgments of participants with (filled bars) and without siblings (unfilled bars) in each face age group from (a) Face Age Group 1 (M=0.30 years, SD=0.09, age range=0.08–0.57 year), (b) Face Age Group 2 (M=1.57 years, SD=0.52, age range=0.58–2.16 years), (c) Face Age Group 3 (M=3.67 years, SD=0.83, age range=2.17–4.66 years), to (d) Face Age Group 4 (M=5.48 years, SD=0.55, age range=4.67–6.50 years). **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, Error bars: SE.

For age judgments, we found a significant main effect of face age group, F(3, 213) = 390.70, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.85. Post hoc analysis showed that adults regardless of whether they had siblings judged the ages of the youngest group the youngest, followed by the second, the third, and the fourth face age group, consistent with the regression findings (Fig. 3b). Adults with and without siblings made age judgments similarly in each face age group (group 1: t1 = −1.42, p1 = 0.161; group 2: t2 = −0.90, p2 = 0.372; group 3: t3 = −1.06, p3 = 0.291; group 4: t4 = −0.19, p4 = 0.847).

We also conducted repeated measure ANOVAs on response time of both judgments with the same factors. No significant effects were found on likeability judgments (all p>0.05). But on age judgments, there is a significant main effect of face age group, F(3, 213)= 16.32, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.19. Post hoc analysis showed that participants found it was more difficult to recognize the ages in the third group than others (p<0.001). No gender differences were found.

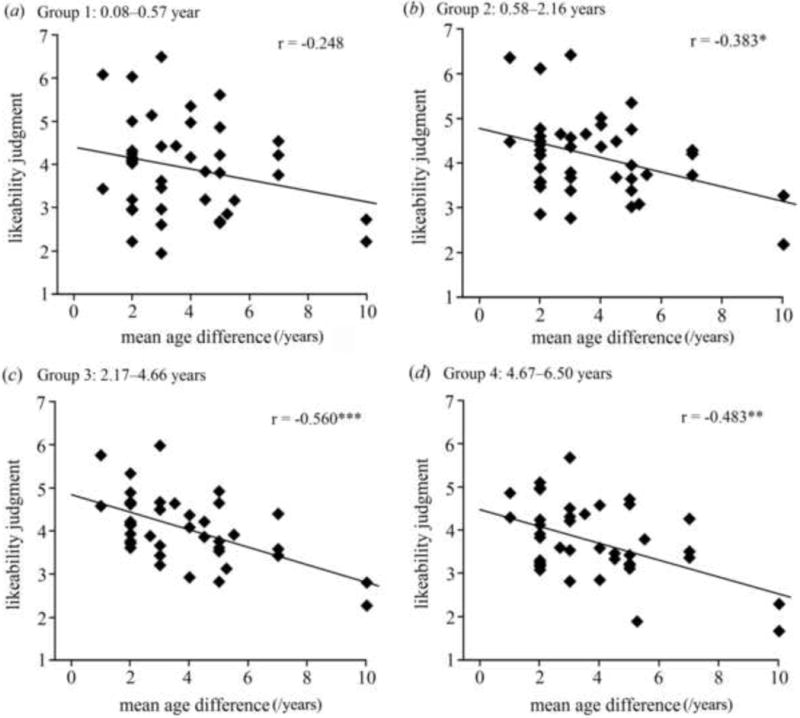

Based on the existing finding of the age difference between siblings and to better understand the sibling effect, we then focused on the data from the 40 participants with siblings by calculating the absolute values of mean age differences between them and each of their siblings. If a participant had more than one sibling, we averaged the age differences between the participants and all their siblings. We conducted Pearson Correlation Analyses to examine whether participants’ likeability judgments were significantly related to the age differences. Also, we used independent sample t-tests to examine the effects of the number of siblings, whether the siblings were older or younger, and sibling gender on participants’ likeability judgments.

Correlation analysis on judgments of likeability and mean age differences between participants and their siblings showed a significantly negative correlation in each face age group except for the youngest one (Fig. 4): the smaller the mean age difference, the greater the likeability judgments. We used the absolute values of the mean age differences in this analysis, because there was no significant difference in each face age group observed for participants who had older as opposed to younger siblings (group 1: t1 = 1.75, p1 = 0.088; group 2: t2 = 1.89, p2 = 0.067; group 3: t3 = 0.56, p3 = 0.578; group 4: t4 = 0.64, p4 = 0.523). There was also no significant influence of the number of siblings (1 vs. >1) (group 1: t1 = 0.36, p1 = 0.723; group 2: t2 = 0.86, p2 = 0.401; group 3: t3 = 1.19, p3 = 0.250; group 4: t4 = 1.26, p4 = 0.227) or the gender of the nearest sibling (same vs. different)(group 1: t1 = −0.64, p1 = 0.530; group 2: t2 = 0.30, p2 = 0.767; group 3: t3 = 1.42, p3 = 0.164; group 4: t4 = 1.79, p4 = 0.081) on participants’ likeability judgments of the male and female children’s faces across the age groups. Further, among the participants with siblings, the mean age differences between them and their siblings were not significantly correlated with their age judgments (group 1: r1 = 0.23, p1 = 0.149; group 2: r2 = 0.16, p2 = 0.330; group 3: r3 = −0.02, p3 = 0.886; group 4: r4 = −0.06, p4 = 0.705).

Fig. 4.

Scatter plots and Pearson correlations of likeability judgments with absolute mean age differences between participants and their siblings in each face age group from (a) Face Age Group 1 (M=0.30 years, SD=0.09, age range=0.08–0.57 year), (b) Face Age Group 2 (M=1.57 years, SD=0.52, age range=0.58–2.16 years), (c) Face Age Group 3 (M=3.67 years, SD=0.83, age range=2.17–4.66 years), to (d) Face Age Group 4 (M=5.48 years, SD=0.55, age range=4.67–6.50 years). ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Discussion

The presence of a cross-cultural preference for visual cues from infant faces has been known for more than a century. Various studies have demonstrated the robust effect of baby schema features proposed by Lorenz on positive adult responses to human infants (Hildebrandt & Fitzgerald, 1978; Langlois, Ritter, Casey, & Sawin, 1995; Sprengelmeyer, et al., 2009). Our results showing high likeability judgments in both sibling and no-sibling groups for the faces of infants under 7 months also replicated this general finding. This effect of baby schema extends to own-race child faces (Glocker, et al., 2009; Lobmaier, et al., 2010), other-race human infant faces with which adults are not familiar (Volk, 2009), as well as faces of other species such as kittens, puppies and monkeys (Brosch, Sander, & Scherer, 2007; Koda, Sato, & Kato, 2013). There is also evidence for species-specificity as the human brain responds more strongly to human baby faces than other animal infants (Caria, et al., 2012). This effect even extends to young children at the age of 3–6 years old. For example, children’s viewing time on adult faces with high baby schema features was significantly longer than those with low features (Borgi, Cogliati-Dezza, Brelsford, Meints, & Cirulli, 2014). However, all the existing studies have focused on the innate releasing mechanism of the baby schema itself, including its decrease with facial age (Luo, et al., 2011; Volk, Lukjanczuk, & Quinsey, 2007); but no study to date has examined how experience might modulate the manifestation of the mechanisms.

The present study provides the first empirical evidence to suggest that experience with siblings plays a significant role in our positive responses to young children’s faces, notwithstanding a limitation of a relatively small number of face stimuli used in the study. In contrast to adults without siblings whose liking of young children’s faces declined with increased face age, adults with siblings maintained their likeability for young children’s faces to at least as old as 6.5 years of age. Our finding could not be attributed to differences between the two groups in perceiving the baby schema facial features as both groups performed equally well in judging the ages of young children’s faces. Because neither of the two groups had work-related experience with young children it is also unlikely that the group differences were attributable to no-sibling related experiences of children, although we cannot rule out a contribution being exposed to additional children in the home environment (i.e., playmates of siblings etc). Our finding that the age difference between siblings influences the strength of likeability for children’s faces also cannot be simply explained as a familiarity effect due to differential length of time participants were exposed to siblings. This is because the effect occurred irrespective of whether the siblings were older or younger. Participants with older siblings would have been exposed to faces of other children for longer than children with younger siblings.

A more likely explanation for this effect of the age-difference between siblings may be how much social interaction they had with their siblings and possibly the strength of the bond between them. The results of the correlation analyses in the present study supported this explanation. We found that the larger the age difference between siblings, the less they are likely to be involved in mutual activities such as play, and also the bonds with them might not be so strong.

Our finding provides a new way to understand the mechanism of baby schema, shifting from the standard understanding which historically has been described as bottom-up perceptual processes to top-down processes tied to prior experience with infants and infant-like animals (Borgi & Cirulli, 2013; Kaufman, et al., 2014). Additionally, the current findings are also consistent with those of Volk and his colleagues (2007). They found differences in the extent of baby schema between older community members and undergraduate students, suggesting the role of individual differences. Our results suggested that one of the possible contributors to individual differences in response to infantile facial cues may be the experience with siblings during childhood. Such experience may serve as a facilitator to enhance and maintain baby schema.

Our finding suggests that having siblings might have adaptive advantages in the evolution of human societies. A combination of life history theory (e.g., Belsky, Steinberg, & Draper, 1991) and kin recognition (e.g., Lieberman, Tooby, & Cosmides, 2007) may explain how and why evolution would evolve the observed behaviors. The presence of siblings suggests an environment with enough resources to sustain multiple offspring, encouraging prolonged investment in one’s future children. The mechanism is the proximity of a sibling that is based on the same mechanisms that determine resemblance (and incest avoidance).

Additionally, in the past, humans usually lived together in large social groups which facilitated caretaking of all children irrespective of direct familial relationships. This allowed more flexibility for parents to work for obtaining resources or to raise group members without parents to help further strengthen the group. In these groups, older children would often have been involved in caretaking duties; indeed in modern families older children are often more involved with taking care of younger siblings. It is therefore interesting that our results do not support a conclusion that older siblings have a greater likeability towards young children in adulthood because of their greater experience of having to carry out caretaking duties for younger siblings. Instead, what appears to be more important is having a sibling close to your own age irrespective of whether they are older or younger. Thus, experience of social interactions and bonds with a similar aged sibling would appear to be one of the most influential factors of the likeability judgment of children’s faces.

An important question is whether adults with siblings find both infants’ and children’s faces equally likeable because they are more responsive to the classical ‘baby schema’ features, or whether additional ‘child schema’ are also being used. The classical ‘baby schema’ features clearly decline with age (see Fig. 1 for example), and if these are the primary visual cues influencing likeability judgments there should be a decline in judgments with age, as we observed in the no-sibling group and in our previous study (Luo, et al., 2011). It is possible that the effect of having a sibling is to enhance general sensitivity to ‘baby schema’ features, but this should have resulted in higher judgments in response to infant faces and a decline with age. Neither of these changes was found. Thus adults with siblings may find additional facial features which distinguish young children from infants or adults as likeable, and switch from using ‘baby schema’ to ‘child schema’ thereby resulting in no age-related decline in their judgments. This possibility clearly requires further investigation.

In agreement with our previous study (Luo, et al., 2011), we found no evidence for gender differences in likeability judgments of infants’ and children’s faces. Some other behavioral as well as neural imaging studies have however reported higher responses given by female than male subjects (Berman, 1980; Glocker, et al., 2009; Proverbio, Brignone, Matarazzo, Del Zotto, & Zani, 2006). We also found no evidence of effects for whether siblings were the same or opposite sex to the participants. Further, it did not seem to matter how many siblings a participant had, although in the current study the majority of participants only had a single sibling.

There are some limitations in the present study. First, the number of face images was relatively small that the effect might be stronger with more faces presented. Regarding the sibling effect we found, we cannot exclude the influence of their parents who might have some influences on those participants with siblings in terms of their affinity for children. Furthermore, it is unclear whether people who just love the very idea of children will tend to have more children. If so, growing up with a sibling could lead one to share this affinity because their family is fond of children. Finally, future studies should consider examining ratings of a child’s face as a function of whether or not that participants ever had a sibling whose age matches the age of the to-be-rated face. By comparing the ratings of participants with siblings who do or do not have a specific aged sibling, one should be able to pinpoint the specificity of the sibling effect in likeability judgments. These limitations need to be addressed in future studies so as to elucidate the role of early social experience on the emergence, formation, and development of the baby schema.

Conclusions

Our findings revealed that, consistent with Lorenz’s proposal, human adults have a universal affinity towards infant faces. Furthermore, we for the first time revealed that experience with siblings could extend this affinity from infants’ to children’s faces as old as 6.5 years of age. Our findings thus demonstrate an interaction between innate releasing mechanisms and postnatal experience in our protective and caretaking responses towards infants and children.

Highlights.

We examine the likeability towards infant and child faces by adults with vs. without siblings

Having siblings extend the influence of the baby schema from infants to children

Having siblings leads adults to like child faces more than those without siblings.

Adults with siblings show stronger likeability for children’s faces when their ages are closer to their siblings.

Innate releasing mechanisms and postnatal experience affect protective and caretaking responses towards infants and children.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC30770727, NSFC81171289, and NSFC91132720), and Development of face expertise (NIH HD 46526). The authors thank Zhan Xu & Yongping Zhao from Southwest University, Chongqing, China for help in programming and conducting the experiments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Belsky J, Steinberg L, Draper P. Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: An evolutionary theory of socialization. Child development. 1991;62:647–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman PW. Are women more responsive than men to the young? A review of developmental and situational variables. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:668–695. [Google Scholar]

- Borgi M, Cogliati-Dezza I, Brelsford V, Meints K, Cirulli F. Baby schema in human and animal faces induces cuteness perception and gaze allocation in children. Frontiers in Psychology. 2014;5:411. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgi M, Cirulli F. Children’s preferences for infantile features in dogs and cats. Human-Animal Interaction Bulletin. 2013;1:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Brosch T, Sander D, Scherer KR. That baby caught my eye…attention capture by infant faces. Emotion. 2007;7:685–689. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.3.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caria A, de Falco S, Venuti P, Lee S, Esposito G, Rigo P, Bornstein MH. Species-specific response to human infant faces in the premotor cortex. NeuroImage. 2012;60:884–893. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin SF, Wade TJ, French K. Race and facial attractiveness: Individual differences in perceived adoptability of children. Journal of Cultural and Evolutionary Psychology. 2006;4:215–229. [Google Scholar]

- Glocker ML, Langleben DD, Ruparel K, Loughead JW, Gur RC, Sachser N. Baby schema in infant faces induces cuteness perception and motivation for caretaking in adults. Ethology. 2009;115:257–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2008.01603.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasnain N, Adlakha P. Self-esteem, social maturity and well-being among adolescents with and without siblings. IOSR J Humanities Soc Sci. 2012;1:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Heer DM. Effects of sibling number on child outcome. Annual Review of Sociology. 1985:27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt KA, Fitzgerald HE. Adults’ responses to infants varying in perceived cuteness. Behavioural Processes. 1978;3:159–172. doi: 10.1016/0376-6357(78)90042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karraker KH, Stern M. Infant physical attractiveness and facial expression: Effects on adult perceptions. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1990;11:371–385. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Tarasuik JC, Dafner L, Russell J, Marshall S, Meyer D. Parental misperception of youngest child size. Current Biology. 2014;23:1085–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koda H, Sato A, Kato A. Is attentional prioritisation of infant faces unique in humans?: Comparative demonstrations by modified dot-probe task in monkeys. Behavioural Processes. 2013;98:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2013.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois JH, Ritter JM, Casey RJ, Sawin DB. Infant attractiveness predicts maternal behaviors and attitudes. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:464–472. [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Quinn PC, Pascalis O, Slater A. Development of face processing abilities. In: Zelazo Ph., editor. Oxford handbook of developmental psychology. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 338–370. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman D, Tooby J, Cosmides L. The architecture of human kin detection. Nature. 2007;445:727–731. doi: 10.1038/nature05510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobmaier JS, Sprengelmeyer R, Wiffen B, Perrett DI. Female and male responses to cuteness, age and emotion in infant faces. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2010;31:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz K. Die angeborenen Formen möglicher Erfahrung. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. 1943;5:235–409. [Google Scholar]

- Luo LZ, Li H, Lee K. Are children’s faces really more appealing than those of adults? Testing the baby schema hypothesis beyond infancy. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2011;110:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macchi Cassia V, Kuefner D, Picozzi M, Vescovo E. Early experience predicts later plasticity for face processing: evidence for the reactivation of dormant effects. Psychological science. 2009;20:853–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macchi Cassia V. Age biases in face processing: The effects of experience across development. British Journal of Psychology. 2011;102:816–829. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.2011.02046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlister AR, Peterson CC. Siblings, theory of mind, and executive functioning in children aged 3–6 years: new longitudinal evidence. Child Development. 2013;84:1442–1458. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhman A, Mineka S. Fears, phobias, and preparedness: Toward an evolved module of fear and fear learning. Psychological Review. 2001;108:483–522. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons CE, Young KS, Murray L, Stein A, Kringelbach ML. The functional neuroanatomy of the evolving parent-infant relationship. Progress in Neurobiology. 2010;91:220–241. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascalis O, de Haan M, Nelson CA. Is face processing species-specific during the first year of life? Science. 2002;296:1321–1323. doi: 10.1126/science.1070223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proverbio AM, Brignone V, Matarazzo S, Del Zotto M, Zani A. Gender and parental status affect the visual cortical response to infant facial expression. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:2987–2999. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter JM, Casey RJ, Langlois JH. Adults’ responses to infants varying in appearance of age and attractiveness. Child Development. 1991;62:68–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprengelmeyer R, Perrett DI, Fagan EC, Cornwell RE, Lobmaier JS, Sprengelmeyer A, Young AW. The cutest little baby face: a hormonal link to sensitivity to cuteness in infant faces. Psychological Science. 2009;20:149–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatarunaite E, Playle R, Hood K, Shaw W, Richmond S. Facial attractiveness: A longitudinal study. American Journal of Orthodontics and Den tofacial Orthopedics. 2005;127:676–682. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2004.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taumoepeau M, Reese E. Understanding the self through siblings: Self-awareness mediates the sibling Effect on social understanding. Social Development. 2014;23:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE. Asymmetrical effects of positive and negative events: The mobilization-minimization hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:67–85. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderLaan DP, Blanchard R, Wood H, Zucker KJ. Birth order and sibling sex ratio of children and adolescents referred to a Gender Identity Service. PloS one. 2014;9:e90257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk AA, Darrell-Cheng C, Marini ZA. Paternal care may influence perceptions of paternal resemblance. Evolutionary Psychology. 2010;8:516–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk AA, Lukjanczuk JL, Quinsey VL. Perceptions of child facial cues as a function of child age. Evolutionary Psychology. 2007;5:801–814. [Google Scholar]

- Volk AA. Chinese infant facial cues. Journal of Evolutionary Psychology. 2009;7:225–240. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang QF. The strength of sibling ties: Sibling influence on status attainment in a Chinese family. Sociology. 2014;48:75–91. [Google Scholar]