Abstract

Avoidance coping is consistently linked with negative mental health outcomes among women experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV). This study extended the literature examining the potentially mediating role of avoidance coping strategies on both mental health and substance use problems to a highly generalizable, yet previously unexamined population (i.e., women experiencing bidirectional IPV) and examined multiple forms of IPV (i.e., psychological, physical, and sexual) simultaneously. Among a sample of 362 women experiencing bidirectional IPV, four separate path models were examined, one for each outcome variable. Avoidance coping mediated the relationships between psychological and sexual IPV victimization and the outcomes of PTSD symptom severity, depression severity, and drug use problems. Findings indicate nuanced associations among IPV victimization, avoidance coping, and mental health and substance use outcomes.

Keywords: Intimate partner violence, women’s mental health, traumatic stress, depression, substance abuse, coping

1. Introduction

Avoidance coping strategies are associated with poorer mental health outcomes among women who experience intimate partner violence (IPV) (Calvete et al., 2008; Lilly and Graham-Bermann, 2010; Sullivan et al., 2005). However, the mediating role of avoidance coping in the relationships between IPV victimization and specific mental health and substance use problems has not been examined. A more detailed understanding of the role of avoidance coping is critical to developing and modifying interventions to improve women’s health (Hamby and Gray-Little, 1997; Hamby and Gray-Little, 2000). Therefore, the present study aims to examine avoidance coping as a potential mediator of the relationships between different types of IPV victimization and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, drug and alcohol problems (Lee et al., 2007; Sullivan et al., 2005) among a sample of women who both experience IPV victimization, and use IPV, in their current intimate relationships. Our study will fill three gaps in the existing literature: 1) Examine the association between multiple forms of IPV victimization simultaneously with avoidance coping, 2) examine psychological and sexual IPV victimization in addition to physical IPV victimization, and 3) extending this area of study to the more generalizable, and frequently understudied population of women experiencing bidirectional IPV.

Avoidance coping is often conceptualized as cognitive, emotional, and behavioral efforts aimed at regulating distress and minimizing threat (Roth and Cohen, 1986). Avoidance coping may include efforts to block distressing memories, rationalize one’s distressing experiences, or denial by fantasy. Existing research clearly identifies negative long-term effects of utilizing avoidance coping strategies in response to negative life events such as IPV victimization (i.e., poorer mental health outcomes) (Iverson et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2007; Sullivan et al., 2005). However, avoidance coping strategies also function as a normative and self-reinforcing method of reducing distress associated with IPV victimization (Sullivan et al., 2005). That is, avoidance coping strategies serve an immediate purpose by reducing distress and perception of threat, but may negatively influence one’s daily functioning and treatment response (Leiner et al., 2012).

Some studies have examined the mediating role of women’s coping strategies in the relationship between IPV victimization and mental health outcomes (Calvete et al., 2008; Lilly and Graham-Bermann, 2010; Sullivan et al., 2005). However, three critical gaps in the literature remain. First, there is a paucity of studies examining the mediating role of avoidance coping in the relationship between different types of IPV victimization and different types of mental health and substance use problems. Only three studies to date have examined this topic (Calvete et al., 2008; Sullivan et al., 2010; Weiss et al., 2014). Calvete and colleagues (2008) found that disengagement coping mediated the effect of psychological IPV victimization on anxiety and depression. Sullivan and colleagues (2010) found that IPV victimization as measured by a single construct encompassing both psychological and physical IPV was indirectly related to depression, but not PTSD, through avoidance coping. Weiss and colleagues (2014) found that moderate levels of avoidance coping were associated with fewer drug problems, but low and high avoidance coping were associated with greater drug problems. Only one study examined substance use (e.g., drug) problems (Weiss et al., 2014), which are highly prevalent among this population (Testa et al., 2003).

Second, few studies have examined psychological IPV victimization in relation to avoidance coping and mental health outcomes, and none have examined sexual IPV victimization. Instead, the existing literature has focused primarily on physical IPV victimization (Iverson et al., 2013; Krause et al., 2008). Research that has investigated psychological IPV victimization in relation to coping have blended it into one construct with physical IPV (Krause et al., 2008). Although sexual IPV victimization has not been studied explicitly, Peneles and colleagues (2011) found that among a sample of women with recent sexual assault, those women who were more prone to reminders of their assault and more reliant on avoidance coping strategies were more likely to maintain or increase the severity of their PTSD symptoms over time. It is critical to expand this literature to include psychological and sexual IPV victimization because they often result in unique and particularly detrimental effects on mental health and substance use among women (Pico-Alfonso et al., 2006; Sullivan et al., 2012).

Third, there is an absence of studies focused on coping strategies among women who both experience IPV victimization and use IPV against their partner (i.e., bidirectional IPV). Bidirectional IPV is the most commonly occurring form of IPV in the U.S. (Straus, 2008). With one exception (Sullivan et al., 2005), previous coping studies have focused on women from samples where the primary inclusion criterion was IPV victimization, resulting in limited generalizability of findings. Women who only experience IPV victimization represent a smaller, and possibly more severe subset of U.S. women who experience IPV (Iverson et al., 2013; Johnson and Ferraro, 2000). Thus, it is challenging to characterize the relationships between IPV victimization, coping, and mental health and substance use problems without understanding the context in which IPV occurred (i.e., bidirectional IPV versus IPV victimization only). Examining these relationships among women with bidirectional IPV is an important methodological advancement with clinical implications.

The present study examined the potential mediating effects of avoidance coping on the relationships between psychological, physical, and sexual IPV victimization and the outcomes of PTSD, depression, and alcohol and drug use problems in a sample of women who both experience IPV victimization and use IPV with their current partner. Results of our study may provide a more in-depth understanding of the role of avoidance coping in the relationships between multiple types of IPV victimization and mental health and substance use problems and may highlight the potential benefit of targeting avoidance coping in future treatment development research and clinical efforts. Past research suggests that this avenue of intervention development is promising because coping strategies are highly modifiable with intervention (Iverson et al., 2013). We expected that avoidance coping would mediate the relationships between each type of IPV victimization and PTSD, depression, and alcohol and drug use problem severity, such that greater victimization would be associated with more avoidance coping, which in turn would be related to more negative outcomes.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Community women (N = 412) were recruited via flyers placed throughout the community in locations such as health clinics, salons, libraries, grocery stores, and laundromats. Eligibility was determined by a phone screen. Women were eligible if they reported at least one act of physical IPV against their current male partner in the last six months, at least one instance of physical IPV victimization with a current male partner, engaged in an intimate relationship of at least six months, were at least 18 years of age, lived in the surrounding urban area, identified their ethnicity as African American, Latina, or White, and reported a household income of less than $50,000 annually (determined a priori to control for varying access to resources associated with income). Seven women were excluded from our analyses due to missing data.

The final sample consisted of 362 women (133 African American, 131 Latina, and 98 White). On average, women were 36.62 years old (SD = 8.99), had a high school level education (M = 12.49, SD = 2.23), and had been in their current relationship for approximately eight years (M = 7.89, SD = 6.77). The modal annual household income in this sample was less than $10,000. Approximately 66% of women reported being married to or cohabiting with their partner (n = 240) and 77% had at least one child (n = 278; range= 0–9). Approximately 64% reported being currently unemployed or unable to work (n = 230). Approximately 13% were employed full-time (n = 51) and 19% were employed part-time (n = 76).

2.2. Procedures

Data were collected as part of a larger single-site study conducted via self-report survey and interview with a trained female researcher of the same race/ethnicity. The purpose of the larger study was to develop a theory for women’s use of aggression. Eligible women provided informed consent and completed a 2-hour protocol via a computer-assisted interview in English or Spanish. Approximately half (49%) of the Latina participants elected to have the protocol administered in Spanish. A bilingual/bicultural research associate translated the survey instruments lacking a Spanish version. Materials were back-translated by a bicultural consultant according to standard procedures outlined by Brislin (1970).

Upon completion of the study, participants were debriefed, provided with a list of community resources, and remunerated $50. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the senior author’s home institution.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Avoidance Coping

Strategies for coping with conflict in participants’ current intimate relationship were assessed with the 11-item avoidance subscale of the 33-item Coping Strategy Indicator (CSI; Amirkhan, 1990). Participants were instructed to describe a conflict with their current partner during the past six months that caused them to worry, and to rate the extent to which each coping strategy was used in response to that conflict. Response categories included: 1 (not at all), 2 (a little), and 3 (a lot). Responses were summed with higher scores indicative of greater avoidance coping. Cronbach’s α =0.67.

2.3.2 Psychological IPV Victimization

Psychological IPV victimization during the past six months was assessed using 22 items. In order to obtain the most comprehensive assessment of psychological IPV, we used 14 items from the Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory-Short version (PMSI-S; Tolman, 1999) in combination with 6 items were from the verbal aggression subscale of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS-2; Straus et al., 2003). The six items from the CTS-2 verbal aggression subscale assessed different aspects of verbal aggression that were not assessed by the PMWI-S. Two additional items were developed for this study: “Has your partner followed you out of the house to check on what you were doing?,” a stalking tactic experienced by victims of IPV (Basile et al., 2004; Basile and Hall, 2011) and “Did your partner try to keep you from seeing or talking to your family”. The psychological IPV score was a sum of these 22 items, with higher scores indicative of greater psychological IPV victimization, Cronbach’s α = 0.88.

2.3.3 Physical IPV victimization

Twelve items comprising the physical assault subscale from the CTS-2 (Straus et al., 2003) assessed physical IPV during the past six months. Response options on the CTS-2 included: never, once, twice, 3–5 times, 6–10 times, and more than 10 times in the past 6 months. Responses were recoded according to procedures outlined by Straus and colleagues (2003; i.e., 3–5 times [recoded to 4], 6–10 times [recoded to 8], and more than 10 times [recoded to 11]), then summed to obtain a total score. Higher scores are indicative of greater physical IPV victimization, Cronbach’s α = 0.85.

2.3.4 Sexual IPV victimization

The 10-item Sexual Experiences Survey assessed sexual IPV during the past six months (SES; Koss and Gidycz, 1985). The original SES response options are yes/no. For the purposes of this study, the response options and scoring system from the CTS-2 (Straus et al., 2003) were used. Items were summed with higher scores indicative of greater sexual IPV victimization, Cronbach’s α = 0.88.

2.3.5 Posttraumatic Stress

Posttraumatic stress symptom severity was assessed using the 49-item self-report Posttraumatic Stress Diagnostic Scale (PDS; Foa, 1995). To the extent possible, PTSD symptoms consistent with DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnostic criteria were assessed in relation to participants’ IPV victimization in their current intimate relationship during the past six months. Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all or only one time) to 3 (five or more times a week/almost always). The 17 items that assessed re-experiencing, avoidance and numbing, and arousal symptoms were summed to yield an index of PTSD symptom severity, Cronbach’s α = 0.91.

2.3.6 Depression

Depression was assessed using the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Participants reported the frequency with which they experienced 20 depressive symptoms over the past six months. Response options range from 1 (rarely or none of the time) to 4 (most or all of the time). Scores between 16 and 26 are indicative of mild depressive symptoms and scores above 27 are indicative of major depressive symptoms. Items were summed to obtain a total score with higher scores indicative of greater severity of depression symptoms, Cronbach’s α = 0.82.

2.3.7 Alcohol Use Problems

Alcohol use problems were assessed using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor et al., 2001). This 10-item self-report measure assesses participants’ alcohol consumption, drinking behavior, adverse reactions, and problems related to alcohol use. Items are rated on a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (more than 4 times per week). Items were summed to obtain a total score, Cronbach’s α = 0.90. Scores of six or more are indicative of harmful alcohol use and possible alcohol dependence among community women (Selin, 2003).

2.3.8 Drug Use Problems

Drug use problems were assessed using the 20-item Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST; Skinner, 1982). Items assess the presence of problems related to participants’ drug use, such as occupational or relational problems, illegal activities, or regret. Responses to each item have 1 (yes) and 0 (no) options. A total severity score was obtained by summing all items, Cronbach’s α = 0.97. For this study, a cutoff of six or above indicated a positive screen for drug use problems (Skinner, 1982).

2.4. Data analytic approach

All study variables were assessed for assumptions of normality. To produce normal distributions as recommended by Tabachnick and Fidell (2007), variables were transformed using the most conservative transformation. Physical IPV victimization, alcohol and drug use problems were log10 transformed to correct excessive skew and sexual IPV was recoded into an ordinal variable (0 = no victimization, 1 = moderate sexual victimization, and 2 = sexual victimization with penetration) as suggested by Gidycz and colleagues (2007) and Rich (2005). Transformed scores were used in all statistical analyses. Study variables were also tested for potential singularity. The correlation between avoidance coping and PTSD avoidance and numbing symptom severity were acceptable (r = .56).

Hypothesized models were analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM) techniques (Kline, 2011) in AMOS® 19.0 (Arbuckle, 2010). One model was run for each of the four outcome varibles including PTSD, depression, and alcohol and drug use problems. A complete model comprising all structural paths was first tested for each of the outcome variables (i.e., PTSD, depression, and alcohol and drug use problems). Structural paths were tested, and non-significant (p > 0.05) paths were trimmed to produce more parsimonious models as recommended by Kenny (1999). Standard measures were used to assess model fit [i.e., chi-square, Normed fit index (NFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)]. Adequate model fit was assessed by a nonsignificant χ2, values of NFI, TLI, and CFI ≥ .90, and lower RMSEA values (particularly those<.05) (Browne and Cudeck, 1992; Hu, 1999; Lei and Wu, 2007). Standardized coefficients are presented.

Bootstrapping procedures in AMOS® were used to estimate the significance of indirect effects. Bootstrapping is a preferred method for estimating and testing hypotheses related to mediation compared to other methods (e.g., the Sobel test) as it does not rely on the assumption that the indirect effect is normally distributed (Kline, 2011; Preacher and Hayes, 2008). Bootstrapping was done with 2,000 random samples generated from the observed covariance matrix to estimate bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals and significance values for the standardized direct, indirect, and total effects in the final model as suggested by Cheung and Lau (2008).

3. Results

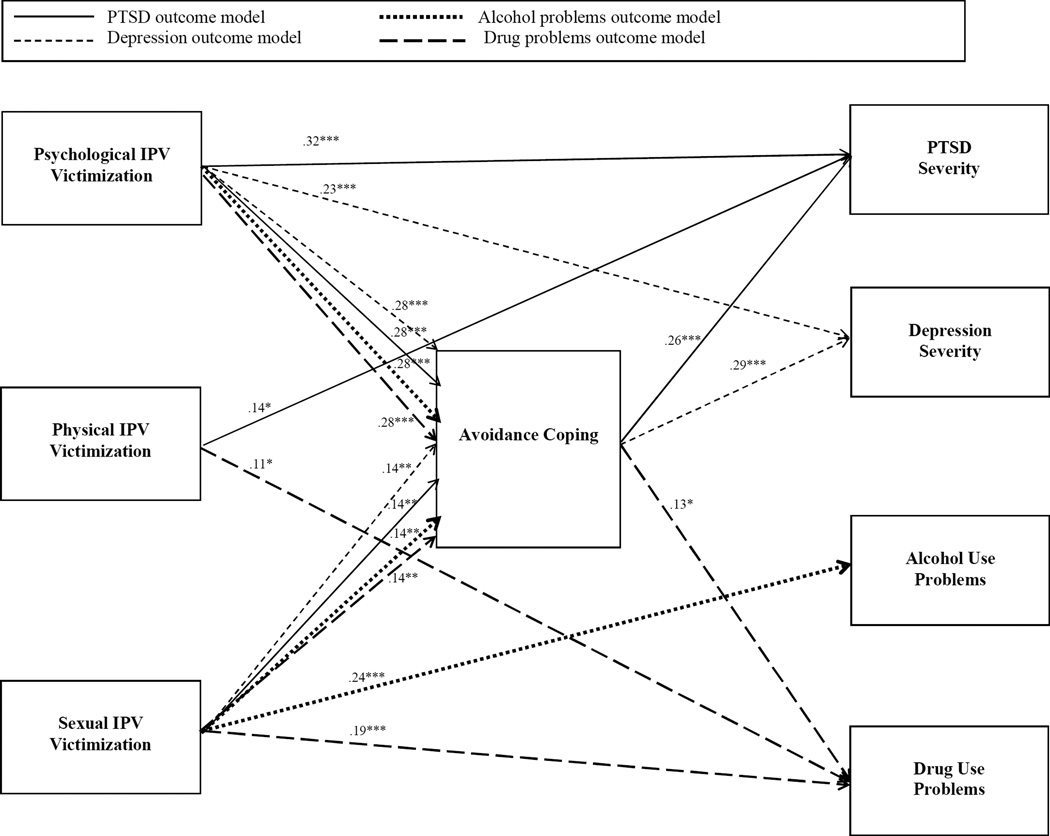

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations are presented in Table 1. Participants reported average psychological, physical, and sexual IPV perpetration scores of 69.90 (SD = 32.64; range = 7–185); 18.91 (SD = 19.82; range = 1–104); 2.67 (SD = 6.99; range = 0–50), respectively. The direct and indirect relationships resulting from the four trimmed models are depicted in Figure 1. The first trimmed model, which examined PTSD severity as the outcome variable, provided adequate fit to the data, χ2(2) = 4.35, p = 0.11, χ2/df = 2.17, NFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.97; CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.06 [CI = 0.00–0.13]. In this model, which accounted for 31% of the variance, avoidance coping mediated the relationships between psychological and sexual IPV victimization and PTSD severity (β = 0.07, CI = 0.04.–0.12, p = 0.001; β = 0.04, CI = 0.01–0.08, p = 0.01). Psychological and physical IPV victimization were directly related to PTSD severity (β = 0.32, p < 0.001; β = 0.14, p < 0.05).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations Among all Study Variables

| Observed Range |

Mean | Standard Deviation |

1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Avoidance Coping | 12–33 | 23.30 | 4.36 | |||||||

| 2. Psychological IPV Victimization | 8–219 | 84.05 | 45.00 | 0.27** | ||||||

| 3. Physical IPV Victimization | 1–111 | 20.35 | 23.55 | 0.29** | 0.58** | |||||

| 4. Sexual IPV Victimization | 0–96 | 8.39 | 15.71 | 0.33** | 0.43** | 0.36** | ||||

| 5. Posttraumatic Stress Severity | 0–49 | 18.80 | 10.75 | 0.40** | 0.46** | 0.41** | 0.39** | |||

| 6. Depression Severity | 0–53 | 23.55 | 10.65 | 0.36** | 0.28** | 0.22** | 0.28** | 0.67** | ||

| 7. Alcohol Use Problems | 0–36 | 4.65 | 6.91 | 0.12* | 0.08 | 0.14** | 0.25** | 0.06 | −0.01 | |

| 8. Drug Use Problems | 0–18 | 2.48 | 4.06 | 0.20** | 0.11* | 0.21** | 0.22** | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.49** |

Note. Log transformed scores were used for physical IPV victimization, alcohol and drug use problems. Means and standard deviations are untransformed scores; correlations are based on transformed scores. IPV = Intimate partner violence.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Figure 1.

Depicted is an integrated figure of all four separately conducted path models: one for each outcome variable. As noted in the legend, solid lines represent results from the model examining PTSD severity as the outcome. Short dashed lines represent results from the model examining depression severity as the outcome. Dotted lines represent results from the model examining alcohol use problems as the outcome. Long dash lines represent results from the model examining drug use problems as the outcome. Paths not retained in the final model are not depicted in the figure. *p < .05 **p < .01 *** p ≤ .001.

The second trimmed model, which examined depression severity as the outcome provided excellent fit to the data, χ2(1) = 0.17, p = 0.68, χ2/df = 0.17, NFI = 0.99, TLI = 1.03; CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00 [CI =0.00–0.10]. In this model, which accounted for 18% of the variance, physical IPV victimization was not associated with depression severity and therefore was trimmed from the model. Avoidance coping mediated the relationship between psychological and sexual IPV victimization (β = 0.08, CI = 0.05–0.13, p = 0.001; β =0.04, CI = 0.01–0.08, p = 0.01) and depression severity. Psychological IPV victimization also was directly (β = 0.23, p < 0.001) related to depression severity.

The third trimmed model examined alcohol use problems as the outcome and also provided good fit to the data, χ2(2) = 1.37, p = 0.50, χ2/df = 0.69, NFI = 0.99, TLI = 1.02; CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00 [CI = 0.00–0.09]. In this model, avoidance coping, psychological and physical IPV victimization were unrelated to alcohol use problems. Psychological IPV was retained in the model as it was directly (β = 0.28, p < 0.001) related to avoidance coping. Sexual IPV was directly (β = 0.24, p < 0.001) related to alcohol use problems and avoidance coping (β = 0.14, p < 0.01).

The fourth and final model examined drug use problems as the outcome and provided good fit to the data, χ2(2) = 5.97, p = 0.05, χ2/df = 2.99, NFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.94; CFI =0.99, RMSEA = 0.07 [CI = 0.00–0.15]. In this model, avoidance coping mediated the relationships between psychological and sexual IPV victimization and drug use problems (β = 0.04, CI = 0.01–0.07, p = 0.015; β = 0.02, CI = 0.003–0.05, p = 0.014). Physical and sexual IPV victimization were directly (β = 0.11, p < 0.05; β = 0.19, p < 0.001) related to drug use problems.

4. Discussion

This study adds to the literature by examining the mediating effects of avoidance coping on the relationships between psychological, physical, and sexual IPV victimization and PTSD symptom severity, depression severity, and substance use problems. This study addresses three critical gaps in the literature by 1) examining three different types of IPV simultaneously, 2) examining psychological, physical, and sexual IPV victimization and 3) extending the examination of avoidance coping to women experiencing bidirectional IPV. Avoidance coping mediated the relationships between psychological and sexual IPV victimization and a) PTSD, b) depression, and c) drug use problems, respectively. These findings contribute to the literature by emphasizing the differential relationships that each type of IPV victimization has with avoidance coping, and the differential effects that IPV victimization and avoidance coping together have on mental health and substance use problems in this population. In this sample, avoidance coping substantially influenced women’s mental health and drug use problems, particularly when they are used in the context of psychological and sexual IPV victimization.

Psychological and sexual IPV victimization are known to have particularly detrimental effects on women’s health (Pico-Alfonso et al., 2006). Perhaps these more pervasive and detrimental forms of IPV victimization are more likely to elicit the use of avoidance coping strategies, which is in turn related to a greater severity of mental health problems. Some researchers have hypothesized that women may be particularly vulnerable to IPV victimization in the context of intoxication, which may also account for the unique associations between sexual IPV and alcohol problems. Further, findings from the literature regarding the association between substance use and women’s IPV victimization have yielded mixed findings. For example, Coker and colleagues (2002) found that women’s IPV victimization was associated with alcohol and painkiller use, but not other substances. Our findings suggest that clinicians should include assessments of all types of IPV, as victimization may influence treatment response. Because substance use may be conceptualized as an avoidance coping behavior, women’s motivations for substance use should be thoroughly assessed in treatment settings.

The existing literature among other populations suggests that coping skills and strategies are highly modifiable (Badour et al., 2012; Sikkema et al., 2013). However, when coping strategies are taught and implemented in response to other problems such as HIV risk and substance use, they are implemented in response to one’s own behaviors. In contrast, more adaptive coping strategies typically implemented in response to other problems may not be safe or accessible for women who are experiencing severe forms of IPV, or may be more challenging to implement in response to one’s partner’s behaviors. Therefore, future research should focus on developing and testing interventions to determine which adaptive coping strategies are safest and most accessible for women to use under the unique circumstances of psychological and sexual IPV victimization. Specifically, research and clinical endeavors would benefit from exploring motivational interviewing techniques to facilitate providers’ efforts at engaging clients in safety planning strategies and resolving ambivalence regarding clients’ relationships and ongoing conflict resolution strategies.

Our findings also suggest that effects of physical IPV victimization on mental health and substance use problems are not significantly influenced by avoidance coping. Physical IPV victimization was retained in only two models – those examining PTSD severity and drug use problems; in those models, no indirect pathways were found through avoidance coping. Perhaps limiting our sample to those women who experienced bidirectional IPV, or not having sufficient power to include IPV perpetration in our analyses influenced these outcomes. For example, recent studies found that shame, guilt, and fear of retaliation are associated with women’s IPV perpetration (Leisring, 2009; Sippel and Marshall, 2011). Thus, while we cannot make attributions about the association between bidirectional IPV and avoidance coping in this sample, women might use avoidance in response to both victimization and perpetration. Future research and should explore the moderating role of women’s use of IPV on the relationship between physical IPV victimization and mental health and substance use problems.

This study includes some limitations. Excluding other types of coping strategies from our analyses prevents us from drawing conclusions about the potential effectiveness of helping women learn more adaptive coping strategies. Similar to Iverson and colleagues (2013), future intervention-focused research should explore the benefits of minimizing the use of avoidance coping strategies. Despite the relatively large sample, we did not have enough power to include all outcome variables in one model simultaneously. This approach may result in an incomplete understanding of the complex associations among variables in this study. Future research would benefit from utilizing a large enough sample size to effectively conduct these analyses. This study is also limited by its cross-sectional design. Examining the relationships explored in this study and their evolution over time may provide important information about the circumstances under which women use avoidance coping and the longitudinal effects it may have. Finally, the reliability of the avoidance coping subscale fell slightly under the traditional cutoff of .70.

Findings from this study indicate that avoidance coping exacerbates the negative impact of IPV victimization on women’s mental health and substance abuse problems. If replicated, our findings provide a platform to transition of the existing literature from exploration and information gathering to intervention development. Future research and clinical efforts should explore women’s motivations for choosing the coping strategies they employ to enhance our knowledge on this topic and tailor interventions to better meet the treatment needs of women experiencing IPV. Future research and clinical efforts should also aim to build knowledge about the efficacy of interventions to improve women’s coping strategies among those currently experiencing IPV compared to those who have experienced IPV in past relationships.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript is the result of work supported, in part, by resources from the National Institute of Justice (NIJ2001-WT-BX 0502), National Institute on Drug Abuse (T32DA019426), the National Institute on Child Health and Human Development and the Office of Research on Women’s Health (K12HD055885), the National Institute of Mental Health (T32MH020031), the Swiss National Science Foundation (PBLAP1-140055 and PBLAP1-145873), and the University of South Carolina Research Foundation.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Amirkhan JH. A factor analytically derived measure of coping: The Coping Strategy Indicator. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1990;59:1066. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Amos. 19.0 ed. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc.; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The alcohol use disorders identification test. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Badour CL, Blonigen DM, Boden MT, Feldner MT, Bonn-Miller MO. A longitudinal test of the bi-directional relations between avoidance coping and PTSD severity during and after PTSD treatment. Behaviour research and therapy. 2012;50:610–616. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basile KC, Arias I, Desai S, Thompson MP. The Differential Association of Intimate Partner Physical, Sexual, Psychological, and Stalking Violence and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in a Nationally Representative Sample of Women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17:413–421. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000048954.50232.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basile KC, Hall JE. Intimate Partner Violence Perpetration by Court-Ordered Men: Distinctions and Intersections Among Physical Violence, Sexual Violence, Psychological Abuse, and Stalking. J Interpers Violence. 2011;26:230–253. doi: 10.1177/0886260510362896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brislin RW. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of cross-cultural psychology. 1970;1:185–216. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sociological Methods & Research. 1992;21:230–258. [Google Scholar]

- Calvete E, Corral S, Estévez A. Coping as a Mediator and Moderator Between Intimate Partner Violence and Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression. Violence Against Women. 2008;14:886–904. doi: 10.1177/1077801208320907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Lau RS. Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organizational Research Methods. 2008;11:296–325. [Google Scholar]

- Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt HM, Smith PH. Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23:260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB. Posttraumatic stress diagnostic scale manual. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems Pearson, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Loh C, Lobo T, Rich C, Lynn SJ, Pashdag J. Reciprocal relationships among alcohol use, risk perception, and sexual victimization: A prospective analysis. Journal of American College Health. 2007;56:5–14. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.1.5-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby SL, Gray-Little B. Responses to partner violence: Moving away from deficit models. Journal of Family Psychology. 1997;11:339–350. [Google Scholar]

- Hamby SL, Gray-Little B. Labeling partner violence: when do victims differentiate among acts? Violence & Victims. 2000;15:173–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Iverson KM, Litwack SD, Pineles SL, Suvak MK, Vaughn RA, Resick PA. Predictors of Intimate Partner Violence Revictimization: The Relative Impact of Distinct PTSD Symptoms, Dissociation, and Coping Strategies. Journal of traumatic stress. 2013;26:102–110. doi: 10.1002/jts.21781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, Ferraro KJ. Research on domestic violence in the 1990s: The discovery of difference. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;57 [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. Respecification of latent variable models. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA. The Sexual Experiences Survey: Reliability and validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:442–443. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.3.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause ED, Kaltman S, Goodman LA, Dutton MA. Avoidant coping and PTSD symptoms related to domestic violence exposure: a longitudinal study. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21:83–90. doi: 10.1002/jts.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AM, Lam S, Lau S, Chong C, Chui HW, Fong D. Prevalence, course, and risk factors for antenatal anxiety and depression. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2007;110:1102–1112. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000287065.59491.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei P, Wu Q. Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling: Issues and Practical Considerations. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice. 2007;26:33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Leiner AS, Kearns MC, Jackson JL, Astin MC, Rothbaum BO. Avoidant coping and treatment outcome in rape-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2012;80:317. doi: 10.1037/a0026814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leisring PA. What will happen if I punch him? Expected consequences of female violence against male dating partners. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2009;18:739–751. [Google Scholar]

- Lilly MM, Graham-Bermann SA. Intimate partner violence and PTSD: The moderating role of emotion-focused coping. Violence Vict. 2010;25:604–616. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.5.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pico-Alfonso MA, Garcia-Linares MI, Celda-Navarro N, Blasco-Ros C, Echeburúa E, Martinez M. The impact of physical, psychological, and sexual intimate male partner violence on women's mental health: depressive symptoms, posttraumatic stress disorder, state anxiety, and suicide. Journal of women's health. 2006;15:599–611. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineles SL, Mostoufi SM, Ready CB, Street AE, Griffin MG, Resick PA. Trauma reactivity, avoidant coping, and PTSD symptoms: A moderating relationship? Journal of abnormal psychology. 2011;120:240. doi: 10.1037/a0022123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rich CL, Gidycz CA, Warkentin JB, Loh C, Weiland P. Child and adolescent abuse and subsequent victimization: A prospective study. Child abuse & neglect. 2005;29:1373–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth S, Cohen LJ. Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. American Psychologist. 1986;41:813–819. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.41.7.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selin KH. Test-Retest Reliability of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test in a General Population Sample. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27:1428–1435. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000085633.23230.4A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikkema KJ, Ranby KW, Meade CS, Hansen NB, Wilson PA, Kochman A. Reductions in traumatic stress following a coping intervention were mediated by decreases in avoidant coping for people living with HIV/AIDS and childhood sexual abuse. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2013;81:274. doi: 10.1037/a0030144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sippel LM, Marshall AD. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, intimate partner violence perpetration, and the mediating role of shame processing bias. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25:903–910. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addictive Behaviors. Addictive Behaviors. 1982;7:363–371. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Dominance and symmetry in partner violence by male and female university students in 32 nations. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30:252–275. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Warren WL. The Conflict Tactics Scales Handbook: Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2) and CTS: Parent-Child Version (CTSPC) Los Angeles, CA, USA: Western Psychological Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TP, McPartland TS, Armeli S, Jaquier V, Tennen H. Is it the Exception or the Rule? Daily Co-Occurrence of Physical, Sexual, and Psychological Partner Violence in a 90-Day Study of Substance-Using, Community Women. Psychology of Violence. 2012;2:154–164. doi: 10.1037/a0027106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TP, Meese KJ, Swan SC, Mazure CM, Snow DL. Precursors and correlates of women's violence: Child abuse Traumatization, victimization of women, avoidance coping, and psychological symptoms. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;29:290–301. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan TP, Schroeder JA, Dudley DN, Dixon JM. Do Differing Types of Victimization and Coping Strategies Influence the Type of Social Reactions Experienced by Current Victims of Intimate Partner Violence? Violence Against Women. 2010;16:638–657. doi: 10.1177/1077801210370027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. New York: Harper Collins College Publishers; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA, Leonard KE. Women's substance use and experiences of intimate partner violence: A longitudinal investigation among a community sample. Addict Behav. 2003;28:1649–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman RM. The validation of the psychological maltreatment of women inventory. Violence and Victims. 1999;14:25–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Duke AA, Sullivan TP. Evidence for a curvilinear dose-response relationship between avoidance coping and drug use problems among women who experience intimate partner violence. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping. 20141999:1–11. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2014.899586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]