Abstract

Lloviu virus (LLOV), a phylogenetically divergent filovirus, is the proposed etiologic agent of die-offs of Schreiber’s long-fingered bats (Miniopterus schreibersii) in western Europe. Studies of LLOV remain limited because the infectious agent has not yet been isolated. Here, we generated a recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus expressing the LLOV spike glycoprotein (GP) and used it to show that LLOV GP resembles other filovirus GP proteins in structure and function. LLOV GP must be cleaved by endosomal cysteine proteases during entry, but is much more protease-sensitive than EBOV GP. The EBOV/MARV receptor, Niemann Pick C1 (NPC1), is also required for LLOV entry, and its second luminal domain is recognized with high affinity by a cleaved form of LLOV GP, suggesting that receptor binding would not impose a barrier to LLOV infection of humans and non-human primates. The use of NPC1 as an intracellular entry receptor may be a universal property of filoviruses.

Keywords: Lloviu virus, Ebola virus, Filovirus, Viral entry, Viral membrane fusion, Viral glycoprotein, Endosomal cysteine proteases, Viral receptor, Niemann-Pick C1, NPC1

Introduction

Members of the family Filoviridae have non-segmented negative-strand RNA genomes and produce filamentous enveloped particles. Until recently, all known filoviruses belonged to one of two genera–Ebolavirus or Marburgvirus (Kuhn and Becker, 2011). Three ebolaviruses [Ebola virus (EBOV), Bundibugyo (BDBV), and Sudan virus (SUDV)], and two marburgviruses [Marburg virus (MARV) and Ravn virus (RAVV)] are associated with highly lethal outbreaks of filovirus disease in humans and non-human primates, and are endemic in equatorial regions of the African continent (recently reviewed in (Feldmann and Geisbert, 2011; Hartman et al., 2010; MacNeil et al., 2011; Paessler and Walker, 2013; Pourrut et al., 2005). One ebolavirus, Reston virus (RESTV), is thought to be avirulent in humans (Morikawa et al., 2007), but has been associated with multiple incidents of filovirus disease in monkeys exported from the Philippines to the US or Europe for research (Miranda et al., 2002; Rollin et al., 1999). More recently, RESTV was shown to circulate in domesticated pigs in the Philippines (Barrette et al., 2009). There are currently no FDA-approved vaccines or therapeutics to prevent or treat filovirus infections.

Bats are long-suspected filovirus reservoirs (Leroy et al., 2009; 2005; Olival and Hayman, 2014; Pourrut et al., 2009; Swanepoel et al., 1996), but conclusive evidence for their role in the ecology of filoviruses was lacking until recently, when infectious MARV and RAVV were found to circulate in healthy Egyptian rousettes (Rousettus aegyptiacus) (Amman et al., 2012; Towner et al., 2009). Infectious EBOV has not yet been isolated from bats. However, EBOV-specific anti-bodies and viral nucleic acids have been detected in African fruit bats belonging to three species (Hypsignathus monstrosus, Epomops franqueti, and Myonycteris torquata) (Leroy et al., 2005).

In the early 2000s, massive bat die-offs of Schreiber’s long-fingered bats (Miniopterus schreibersii) occurred throughout the Iberian peninsula. Investigators working with bat carcasses from Cueva del Lloviu, Spain, were able to detect filovirus-like nucleic acids in the lung and spleen by PCR (Negredo et al., 2011). While attempts to isolate infectious virus from these carcasses were unsuccessful, a near-complete filovirus genome, equally divergent from those of ebolaviruses and marburgviruses (≈50% nucleotide sequence identity) was assembled (Negredo et al., 2011). Because this viral genome was detected only in carcasses of Schreiber’s long-fingered bats and not in healthy Schreiber’s long-fingered or mouse-eared myotis (Myotis myotis), the authors proposed that a new filovirus-like agent, named Lloviu virus (LLOV) after the site of detection, may have been responsible for the bat die-offs (Negredo et al., 2011). The Internal Committee of Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) placed LLOV in a new genus, Cuevavirus, within the family Filoviridae (Adams et al., 2014; Kuhn et al., 2010). LLOV represents the first filovirus discovered in Europe that was not transported there from an endemic area in Africa or Asia.

Since LLOV is phylogenetically divergent from ebolaviruses and marburgviruses, was discovered in a new geographic area, and may be virulent in bats, it is possible that it differs from other known filoviruses with regard to fundamental mechanisms of infection, multiplication, and in vivo pathogenesis. However, the lack of an isolate has severely impeded the study of LLOV. In this study, we exploited a vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)-based surrogate system to investigate the structural and functional properties of the presumptive envelope glycoprotein (GP) of LLOV, and the mechanism by which it mediates viral entry into the cytoplasm of host cells.

While this manuscript was in preparation, a study describing some entry-related properties of LLOV GP was published (Maruyama et al., 2013). That study employed vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) single-cycle pseudotypes bearing LLOV GP. Here, we used reverse genetics to generate a recombinant VSV containing LLOV GP that is capable of multiple rounds of multiplication in tissue culture, thus providing a robust model for early steps in infection by the authentic virus. Our findings are in agreement with those of Maruyama and co-workers, and extend them in several important respects. Most significantly, we demonstrate that the late endosomal membrane protein Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1) is a critical entry receptor for LLOV that binds directly and with high affinity to a cleaved form of LLOV GP.

Materials and Methods

Cells and viruses

Vero African grivet kidney cells, 293T human embryonic kidney cells, and human primary fibroblasts from control individuals (GM05659) or Niemann-Pick disease patients (GM18436) (Coriell Institute for Medical Research) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlanta Biologicals, Flowery Branch, GA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Life Technologies). Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1)-null Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) fibroblasts (M12 line), a kind gift of Dr. Dan Ory, were maintained in DMEM-F-12 media (50-50 mix) (Corning, Manassas, VA), supplemented with 10% FBS, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Human fibroblasts and CHO M12 cells stably expressing human NPC1-FLAG were generated by retroviral transduction, as previously described (Carette et al., 2011; Miller et al., 2012). Furin-deficient CHO cells (FD11), a kind gift of Dr. Margaret Kielian, were maintained in minimal essential medium (MEM)-alpha (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin-streptomycin and 1% glutamine (Life Technologies). All cell lines were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator.

DNA encoding the LLOV GP gene was synthesized according to Genbank accession number JF828358, except that the sequence was optimized for mammalian cell expression and the AAAAAAA sequence at nucleotide positions 910–916 in the GP open reading frame (complementary to the U7 stutter sequence in the viral genome sequence) was mutated to AAGAAGAA. These changes afforded constitutive production of the full-length viral spike glycoprotein (GP1,2; hereafter referred to as GP). Nucleotide and amino acid sequences for the final LLOV GP expression construct are available as supplementary data. A recombinant VSV (rVSV) encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) and LLOV GP in place of VSV G was rescued from cDNA as described previously (Whelan et al., 1995; Wong et al., 2010). Plaque-purified rVSV-LLOV GP clones were amplified in Vero cells, concentrated by pelleting through 10% sucrose cushions, and stored in aliquots at −80°C. rVSVs bearing EBOV and MARV GP were described previously (Miller et al., 2012; Wong et al., 2010). Sequencing the cDNA corresponding to the GP-coding region within the genomes of these viral particles confirmed that no nucleotide changes had occurred during virus recovery and amplification. All experiments with rVSVs were performed using enhanced biosafety level 2 procedures approved by the Einstein Institutional Biosafety Committee. VSV pseudotypes expressing eGFP and bearing VSV G or filovirus GP were generated as described previously (Takada et al., 1997).

Viral infectivity measurements

Single-cycle VSV infectivity measurements were carried out as described previously (Wong et al., 2010). Briefly, confluent monolayers of cells were exposed to a series of dilutions of each virus-containing sample (in DMEM with 2% FBS) for 1 h at 37°C. Ammonium chloride (20 mM final) was then added to inhibit viral spread (for rVSVs only). eGFP-positive infected cells were manually enumerated by fluorescent microscopy at 14–16 h post infection. Fluorescent focus-forming assays were performed, and viral infection foci were quantified, as described previously (Wong et al., 2010).

Retroviral pseudotypes were produced as previously described (Radoshitzky et al., 2011). Briefly, HEK 293T cells were transfected with (1) a plasmid expressing MARV GP; (2) the pQCXIX vector (Clontech) expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) flanked by the Moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMLV) long terminal repeats; and (3) a plasmid encoding the MoMLV gag-pol genes. Virus-containing cell supernatants were collected at 48 h post transfection and filtered to remove cellular debris. Cells were exposed to MoMLV-MARV GP for 5 h, and then washed and replenished with fresh medium. After 48h post transduction, cells were detached and fixed. The percentage of eGFP-positive cells (% of cells transduced) was measured by flow cytometry (10,000 events; BD LSR Fortessa, San Jose, CA). FlowJo software (Tree Star Inc., San Carlos, CA) was used for data analysis.

Production of a polyclonal antibody to LLOV GP1

A polyclonal antiserum was generated in a rabbit by immunization with a peptide corresponding to residues 84–98 of LLOV GP (TKRWGFRSDVIPKIV), conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) (Pacific Immunology, Ramona, CA). A polyclonal antiserum to the corresponding peptide from EBOV GP has been described previously (Misasi et al., 2012).

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting

Virus-containing samples were resolved in 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels, and proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The LLOV GP1 subunit was detected using the polyclonal antibody described above (1:10,000 dilution), followed by incubation with a secondary antibody, donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (1:10,000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). Bands were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Rockford, IL), followed by exposure to X-ray film. In some experiments, viral proteins were deglycosylated using peptide N-glycosidase F (PNGase F, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. NPC1-FLAG expression in CHO M12 cells was assessed by western blotting of cell lysates resolved in 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gels with an HRP-conjugated anti-FLAG antibody conjugate (1:10,000; Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO).

Protease inhibitor treatments

Cysteine protease inhibitors CA074 [N-(L-3-trans-propylcarbamoyloxirane-2-carbonyl)-Ile-Pro-OH] and E-64 [L-trans-epoxysuccinyl-leucyl-amide-(4-guanido)-butane] (Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA) were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and dispensed into culture medium immediately before use. To inhibit protease activity in cells, monolayers were incubated with drug-containing media at 37°C for 4 h prior to virus infection.

Protease digestion reactions

To examine the sensitivity of rVSV-LLOV-GP to proteolysis, aliquots of concentrated virus were incubated with various amounts of thermolysin (THL; 0–200 μg per ml; Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at 37°C. Reactions were carried out in NT buffer (10 mM Tris.Cl [pH 7.5], 135 mM NaCl), and stopped by adding phosphoramidon (0.5 mM; Peptide International, Louisville, KY) and placing on ice for 15 min.

GP-NPC1 binding ELISAs

rVSV-LLOV-GP was modified using a functional-spacer-lipid reagent conjugated with biotin (FSL-biotin, Sigma) at 37°C for 1 h. The biotin-labeled virions were then captured onto high-binding 96-well plates (Corning) previously coated with streptavidin (0.65 μg per mL in PBS) and blocked with PBS containing 3% bovine serum albumin (PBSA). Prior to capture, virions were either left untreated or incubated with thermolysin (12.5 μg per mL at 37°C for 1 h) to generate rVSV-LLOV GPCL. After washing to remove unbound virus, serial dilutions of purified, FLAG-tagged human NPC1 domain C (domain C; 0–40 μg per mL) were added. Bound domain C was detected with an HRP-conjugated anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma-Aldrich), and Ultra-TMB substrate (Thermo Fisher). Half-maximal binding concentrations (EC50) values were calculated by nonlinear regression analysis of normalized binding curves in Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). All ELISA incubation steps were done at 37°C for 1 h or at 4°C overnight. Each dataset for curve fitting included at least two technical replicates per domain C concentration, and EC50 values were computed from at least two independent experiments.

Generation of a purified LLOV Δ-peptide-Fc fusion protein

LLOV or control SUDV Δ-peptide fused to the fragment crystallizable region (Fc) of human IgG1 was produced and purified as described previously (Radoshitzky et al., 2011). Briefly, HEK 293T cells were transfected with expression plasmids encoding LLOV or SUDV Δ-Fc and grown in 293 SFM II medium (Invitrogen). Supernatants were collected 48 h later and proteins were bound to a protein A-sepharose Fast Flow bead matrix (GE Healthcare). After washing, proteins were eluted with 50 mM sodium citrate-50 mM glycine, pH 2, followed by neutralization with NaOH, dialyzed against PBS, concentrated, and quantified.

Transmission electron microscopy

Vero E6 cells were transfected using X-tremeGENE HP DNA Transfection Reagent (Roche) with a PJ603 plasmid expressing LLOV GP and a pCAGGS plasmid expressing FLAG-tagged LLOV VP40 (1:1 ratio), to generate virus-like particles (VLPs). 72 h later, supernatants were removed and cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (E.M. Sciences, Warrington, PA) in Millonig’s sodium phosphate buffer (Tousimis Research, Rockville, MD) for 20 min, scraped, and spun down at 500 xg for 10 min at 4°C. The pellet was fixed for 24 h at 4°C, and then post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide (E.M. Sciences) and staining en bloc with 2% uranyl acetate. Samples were dehydrated with ethanol and embedded into Spurr plastic resin (E.M. Sciences). Two hundred mesh copper grids were used to mount 60–80 nm sample sections, sliced with a Leica UC7 ultramicrotome. Mounted grids were stained with lead citrate before examination on a FEI G2 Tecnai transmission electron microscope.

Results

Generation of an infectious recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus expressing the LLOV transmembrane envelope glycoprotein

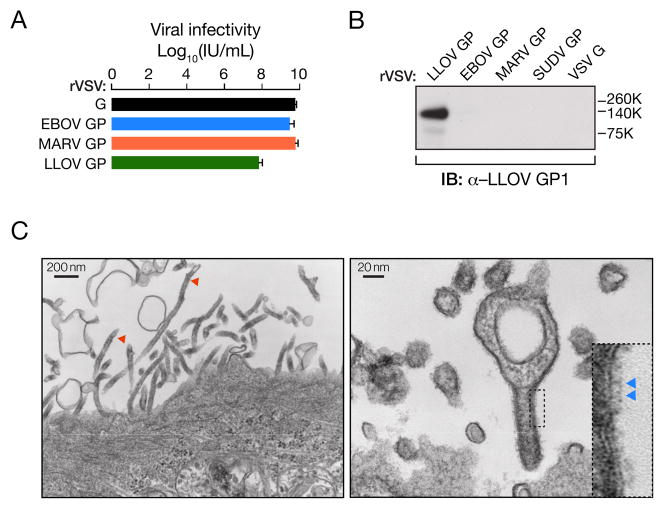

To study the mechanism by which LLOV enters host cells, we focused on the LLOV GP gene, which is predicted to encode a single transmembrane glycoprotein and multiple secreted glycoproteins homologous to their counterparts from African and Asian filoviruses (Figs. 1 and S1) (Negredo et al., 2011). Using reverse genetics, we generated the first recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (rVSV) expressing the LLOV transmembrane glycoprotein GP in place of the orthologous VSV entry glycoprotein, G. The rescued virus was amplified in Vero cells, and the integrity of the LLOV GP gene in multiple viral clones was verified by RT-PCR and sequencing. We found that rVSV-GP-LLOV was competent to form plaques on Vero cell monolayers, and to replicate in these cells at levels comparable to rVSVs bearing other filovirus glycoproteins (Fig. 1A) (Carette et al., 2011; Wong et al., 2010).

Fig. 1. LLOV GP is incorporated into VSV particles and filovirus-like particles, and is competent to mediate cell entry.

(A) Vero cells were exposed to recombinant VSVs (rVSVs) expressing eGFP, and VSV G or different filovirus glycoproteins. Infected cells were visualized by fluorescence microscopy at 12–16 h post-infection. Averages ± SD (n=4) are shown. (B) Incorporation of LLOV GP into rVSVs was determined by SDS-PAGE and western blotting with an LLOV GP1-specific antiserum. (C) Vero E6 cells generating filovirus-like particles (VLPs) consisting of EBOV VP40 and LLOV GP were visualized by transmission electron microscopy. Red arrows, filamentous VLPs released from cells. Blue arrows, spike-like projections from the surface of a VLP, likely corresponding to LLOV glycoprotein spikes.

Because the LLOV glycoprotein in these virus particles was not detected by several EBOV- and MARV GP-specific antibodies, we raised a rabbit polyclonal antiserum against a sequence in the N–terminal region of the LLOV GP1 subunit (residues 83-97; TKRWGFRSDVIPKIV). Western blotting of concentrated rVSV-GP-LLOV particles with this antiserum detected a ≈130K polypeptide that resembles the GP proteins of other filoviruses in molecular weight and presumptively contains the LLOV GP1 subunit (Fig. 1B) (Sanchez et al., 1998; Volchkov et al., 2000).

Finally, to test whether LLOV GP can be incorporated into filovirus-like particles (Martin-Serrano et al., 2001; Noda et al., 2002), we co-transfected 293T human embryonic kidney cells with plasmids encoding GP and the LLOV matrix protein VP40. Examination of thin sections of these cells by transmission electron microscopy revealed both particles with the characteristic filamentous morphology of filovirions and spherical particles. Each type of particle bore a halo of spike-like structures at its surface that was absent in particles produced by cells expressing only VP40 (Fig. 1C), suggesting that these surface spikes are composed of LLOV GP. Taken together, these results indicate that the filovirus-like genomes detected in the Schreiber’s long-fingered bats from Cueva del Lloviu encode a functional viral spike glycoprotein.

The LLOV GP precursor is processed into GP1 and GP2 subunits by the proprotein convertase furin

Filovirus GP proteins are synthesized as a precursor polypeptide, preGP, which trimerizes in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Feldmann et al., 1991; Jeffers et al., 2002; Sanchez et al., 1998; Volchkov et al., 2000; 1998) reviewed in (Feldmann et al., 2001)). Following its transport to the trans-Golgi network (TGN), preGP is post-translationally cleaved to GP1+GP2 subunits by the proprotein convertase furin (Fig. S1) (Sanchez et al., 1998; Volchkov et al., 1998). GP1 and GP2 remain associated through extensive non-covalent interactions and an inter-subunit disulfide bond, and perform distinct functions during cellular entry (Jeffers et al., 2002; J. E. Lee et al., 2008). While GP1 mediates viral attachment to the host cell, binds to the endosomal filovirus receptor NPC1, and regulates the conformation of GP2, GP2 catalyzes the fusion of viral and cellular membranes (see (Miller and Chandran, 2012) for a recent review).

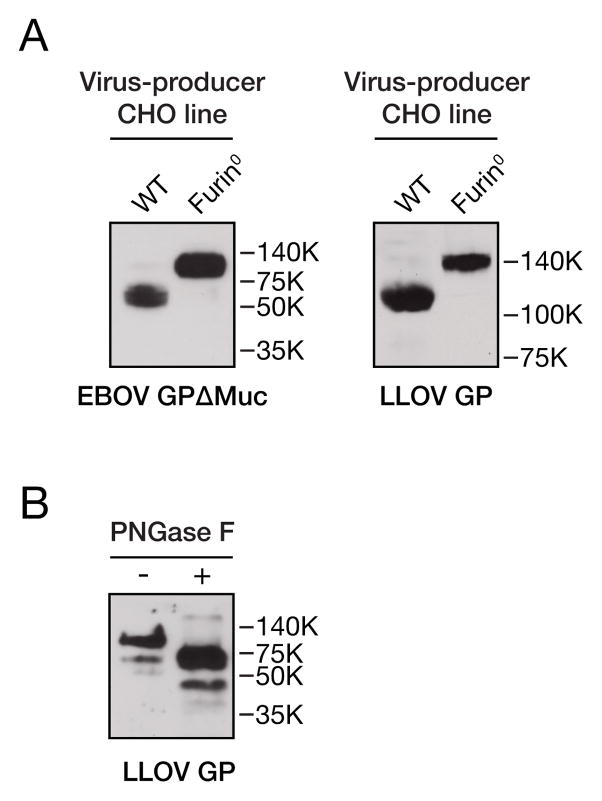

Furin, a ubiquitous subtilisin-like endoprotease, cleaves its target proteins immediately after polybasic sites (consensus: R-X-K/R-R↓) (reviewed in (Seidah et al., 2013)). We identified a single candidate cleavage site for furin in the predicted amino acid sequence of LLOV GP (residues 505-508; RRRR). To experimentally assess whether LLOV GP undergoes furin cleavage, we exposed control or furin-deficient Chinese hamster ovary cell lines to rVSVs containing EBOV or LLOV GP. Virus-containing supernatants from control or furin-deficient FD11 CHO cells (Gordon et al., 1995) were harvested at 48 and 72 h post infection, respectively, and the GP1 subunit in progeny virus particles was detected by immunoblot (Fig. 2A). EBOV GP1 produced by furin-deficient FD11 cells migrated as a larger species than that produced by control cells, indicating that it underwent furin-dependent preGP →GP1+GP2 cleavage, as shown previously (Volchkov et al., 1998). Similarly, LLOV GP1 produced by furin-deficient and control cells migrated at ≈140 and ≈110 kDa, respectively (Fig. 2A), providing evidence that the LLOV GP precursor, like the GP proteins of all other known filoviruses, is a substrate for furin cleavage.

Fig. 2. The LLOV GP precursor is cleaved by furin into GP1 and GP2 subunits, and is extensively N-glycosylated.

(A) rVSV-LLOV GP and rVSV-EBOV GPΔMuc produced in WT CHO cells or the FD11 CHO cell line lacking furin (Furin0) were subjected to reducing SDS-PAGE, and their GP1 subunits were visualized by western blotting with peptide-specific antisera. (B) rVSV-LLOV GP was incubated with protein N–glycosidase F (PNGase F) to remove N–linked glycans, and GP1 was visualized by western blotting.

LLOV GP is subject to extensive N–linked glycosylation and is predicted to contain a central mucin-like domain

Nascent filovirus glycoproteins undergo extensive N–linked and O–linked glycosylation within the secretory pathway of infected cells (Feldmann et al., 1991; Jeffers et al., 2002; J. E. Lee et al., 2008; Sanchez et al., 1998); reviewed in (Feldmann et al., 2001)). Sequence-based analyses of likely glycosylation sites suggested that LLOV GP resembles other filovirus GP proteins in this regard (Fig. S1). First, LLOV GP was predicted to contain a number of N–linked sites distributed throughout the protein. Alignments with EBOV and MARV GP sequences identified sequons conserved among all three proteins; these were located within the regions of GP showing the highest degree of overall sequence (and likely, structural) conservation (N–terminal region of GP1, C–terminal region of GP2). Second, like EBOV and MARV GP, LLOV GP was predicted to undergo O–linked glycosylation at a large number of contiguous sites within a central region of the protein that is also the least conserved among filoviruses in amino acid sequence. These shared features–extensive O–linked glycosylation concentrated within a central, highly variable region of GP–strongly argue that LLOV GP, like the GP proteins of all known African and Asian filoviruses, contains a mucin-like domain (Muc). Muc is proposed to shield GP from host immune detection, and may also promote viral adhesion to specific host cells (Alvarez et al., 2002; Francica et al., 2010; J. E. Lee and Saphire, 2009; Marzi et al., 2007; Reynard et al., 2009).

To experimentally examine N–linked glycosylation in LLOV GP, we exposed concentrated rVSV particles containing EBOV or LLOV GP to protein N–glycosidase F (PNGase F), which enzymatically removes most N–linked glycans (see Materials and Methods for details). Virus particles treated with PNGase F increased the electrophoretic mobility of LLOV GP1 from ≈130 kDa to ≈70 kDa (Fig. 2B). These findings provide evidence that LLOV GP resembles other filovirus GP proteins in the number and distribution of N–linked glycosylated sites, and in presumptively containing a highly O–glycosylated central mucin-like (Muc) domain.

LLOV GP requires endosomal acid pH to mediate viral entry

Filoviruses enter host cells through a macropinocytosis-like pathway, and are then trafficked to late endosomes (Mulherkar et al., 2011; Nanbo et al., 2010; Saeed et al., 2010) (Mulherkar and Chandran, unpublished). These endocytic compartments provide acidic conditions that are proposed to play multiple crucial roles in filovirus entry. First, endosomal cysteine cathepsins, which cleave filovirus glycoproteins to expose the NPC1 receptor-binding site in GP1 (Chandran et al., 2005; Côté et al., 2011; Miller et al., 2012), require endo/lysosomal acid pH for their maturation and activity (reviewed in (Turk et al., 2012)). Second, endosomal acid pH is proposed to be necessary for multiple steps in the GP-catalyzed membrane fusion reaction that effects viral escape into the cytoplasm (reviewed in (Miller and Chandran, 2012; White et al., 2008)).

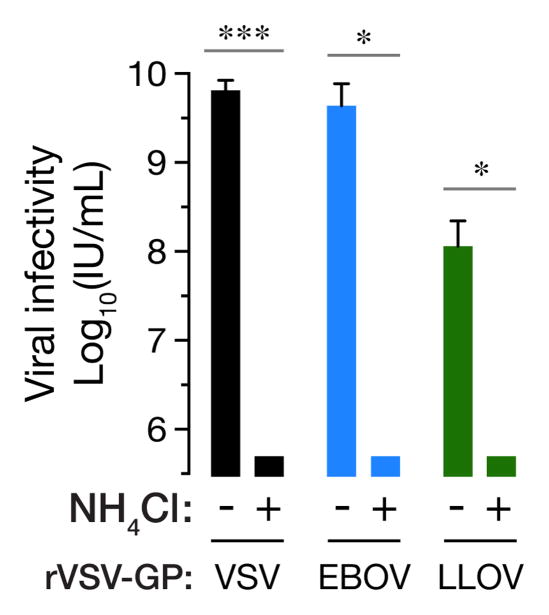

To examine the requirement of endosomal acid pH for LLOV GP-dependent entry, Vero cells were pretreated with ammonium chloride (NH4Cl), which neutralizes endo/lysosomal acid pH, and exposed to rVSV-LLOV-GP. No infection was observed in cells pretreated with NH4Cl, compared to the untreated control (Fig. 3). Therefore, the entry requirement for endo/lysosomal acid pH remains a shared feature of all known filoviruses.

Fig. 3. LLOV GP-mediated entry requires endosomal acid pH.

Vero cells were pre-treated with ammonium chloride (20 mM), and then exposed to rVSVs bearing VSV G or filovirus glycoproteins. Infected cells were visualized by fluorescence microscopy at 12–16 h post-infection. Averages ± SD (n=4) are shown. *, p<0.05. ***, p<0.001.

Endosomal cysteine proteases are essential host factors for LLOV GP-dependent entry

Cysteine cathepsins, a class of endosome/lysosome-resident host cysteine proteases (Turk et al., 2012), are broadly required for filovirus entry and infection, and cathepsin B (CatB) plays a specific viral isolate-dependent role (Chandran et al., 2005; Misasi et al., 2012; Schornberg et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2010). Cleavage of GP by cysteine cathepsins removes the Muc domain and glycan cap (Bale et al., 2011; Chandran et al., 2005; Dube et al., 2009; Hood et al., 2010; J. E. Lee et al., 2008), generating an intermediate that can now recognize the intracellular entry receptor, NPC1 (Miller et al., 2012) and is presumed to be fusion-competent (Brecher et al., 2012) (Wong, Miller, and Chandran, unpublished). In addition to carrying out this priming step, endosomal cysteine cathepsins are proposed to play a role in the fusion triggering process itself (Chandran et al., 2005).

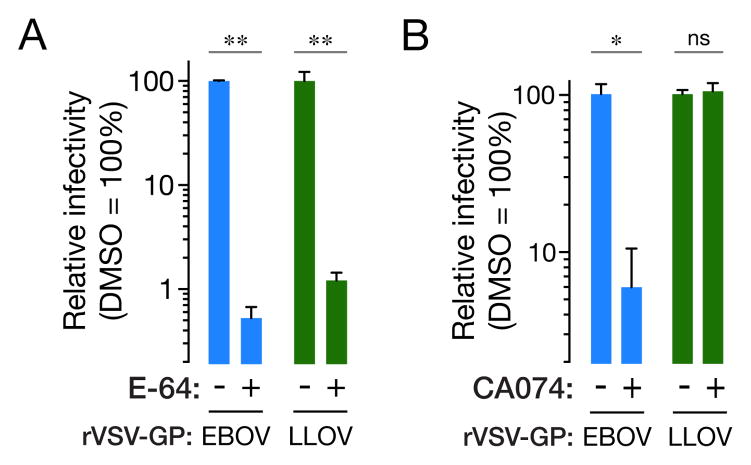

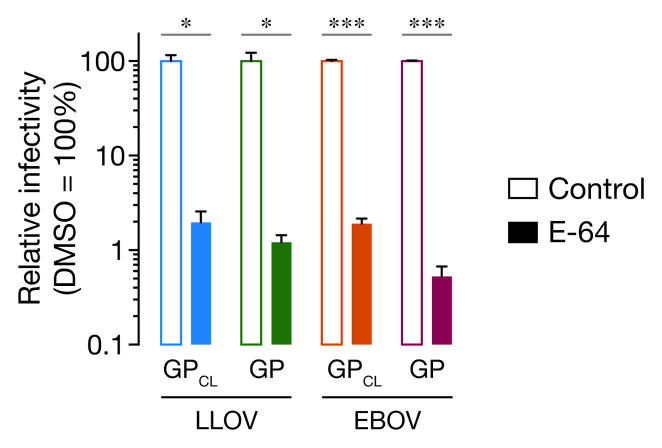

Previous work illustrated this cysteine cathepsin requirement through the use of the Clan CA cysteine protease inhibitor E-64, which effected a >99% reduction in infection mediated by glycoproteins from EBOV, Taï forest virus (TAFV), Sudan virus (SUDV), Reston virus (RESTV), and Marburg virus (MARV) (Chandran et al., 2005; Misasi et al., 2012). Accordingly, we pretreated Vero cells with either E-64 or the vehicle DMSO, and exposed them to rVSV-EBOV-GP and rVSV-LLOV-GP (Fig. 4A). Both viruses were similarly sensitive to E-64 treatment, providing evidence that LLOV GP, like all other known filovirus glycoproteins, requires endosomal cysteine cathepsin activity to mediate viral entry.

Fig. 4. Cysteine cathepsin activity is required for LLOV GP-dependent entry, but cathepsin B (CatB) is dispensable.

(A–B) Vero cells were pre-treated with 1% DMSO (vehicle control), the broad-spectrum cysteine cathepsin inhibitor E-64 (300 μM) (A), or the CatB-selective inhibitor CA074 (B) for 4 h at 37°C, and then exposed to rVSVs bearing EBOV or LLOV GP. Infected cells were visualized by fluorescence microscopy at 12–16 h post-infection. Averages ± SD (n=4) are shown. *, p<0.05. **, p<0.01. ***, p<0.001. ns, not significant.

Cathepsin B is dispensable for LLOV GP-dependent entry

Although all known filoviruses (including LLOV) require host cysteine cathepsins for entry as shown above, the requirement for CatB varies by isolate. In general, CatB activity plays an important role in entry by EBOV, BDBV, and TAFV, but not by SUDV, RESTV, and MARV (Misasi et al., 2012). The molecular bases of these differences in protease dependence remain incompletely defined, but relate at least in part to sequence polymorphisms that modulate GP1-GP2 interactions and the stability of the trimeric GP pre-fusion spike (Wong et al., 2010) (also see Fig. S2). The requirements for specific cysteine cathepsins in viral multiplication in vivo may be more complex, however, since EBOV can infect and kill CatB-knockout mice (Marzi et al., 2012). Whether this is due to the use of alternative proteases or generation of CatB-independent GP variants through mutation (as observed in vitro (Wong et al., 2010)), remains to be determined.

To determine if LLOV GP requires CatB to mediate viral entry, at least in tissue culture, we pretreated Vero cells with the Clan CA protease inhibitor CA074 under conditions that afford selective inhibition of CatB, as described previously (Chandran et al., 2005; Wong et al., 2010). We then challenged these cells with rVSV-EBOV GP and rVSV-LLOV GP. As expected, CA074 reduced EBOV GP-dependent infection by ≈90%; however, little or no reduction was observed in LLOV GP-dependent infection (Fig. 4B). Therefore, CatB is dispensable for viral entry mediated by LLOV GP.

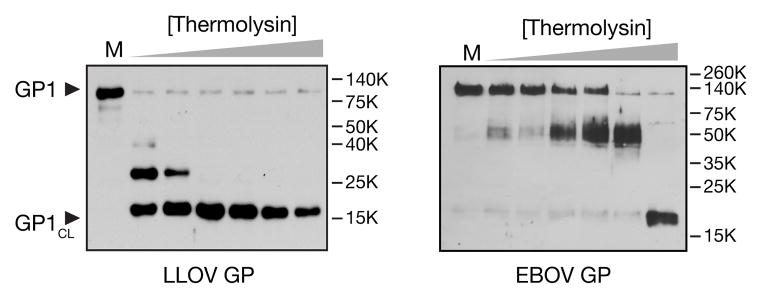

Proteolytic cleavage of LLOV GP in vitro generates a primed entry intermediate

In vitro cleavage of the trimeric GP spike derived from both ebolaviruses and marburgviruses by endosomal cysteine cathepsins, or by surrogate enzymes such as thermolysin, results in the generation of a GP trimer lacking GP1 sequences corresponding to the Muc domain and the glycan cap (Chandran et al., 2005; Dube et al., 2009; Hood et al., 2010; J. E. Lee et al., 2008; Schornberg et al., 2006). This cleaved GP intermediate (GPCL), which is competent to bind to the filovirus receptor NPC1 (Côté et al., 2011; Miller et al., 2012), is proposed to resemble one or more GP species generated within the endocytic pathway during viral entry. The requirement of endosomal cysteine protease activity for LLOV GP-dependent entry suggested that LLOV GP also undergoes cleavage to generate such an entry intermediate.

To test this hypothesis directly, we incubated rVSV-LLOV-GP particles with increasing concentrations of the bacterial metalloprotease thermolysin, which mimics the action of CatB+CatL on EBOV GP (Schornberg et al., 2006). Like EBOV GP1, LLOV GP1 was cleaved by thermolysin to generate an ≈17 kDa intermediate containing its N–terminal ≈190 amino acid residues. This sequence, highly conserved among filoviruses, constitutes the ‘base’ subdomain of GP1, which is covalently and non-covalently associated with GP2, and the ‘head’ subdomain, which contains the NPC1-binding site (Dias et al., 2011; J. E. Lee et al., 2008). Strikingly, the LLOV GPCL intermediate was generated at substantially lower protease concentrations than its EBOV counterpart, indicating that LLOV GP is much more sensitive to proteolytic cleavage than EBOV GP (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. LLOV GP1 is rapidly cleaved to a primed ≈17 kDa species (GP1CL) in vitro.

rVSVs bearing LLOV GP or EBOV GP were exposed to thermolysin (0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200 μg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C. Enzyme digestion was stopped with phosphoramidon (0.5 mM) and GP1 was were visualized by western blotting with peptide-specific antisera that detect an N–terminal region of GP1 (residues 83–97).

LLOV GPCL cannot bypass the entry requirement for endosomal cysteine protease activity

While in vitro-generated EBOV and MARV GPCL can recognize the endosomal receptor NPC1, and bypass requirements for specific endosomal cysteine proteases (e.g., CatB for EBOV), they remain susceptible to a broad-spectrum inhibitor of clan CA cysteine proteases, such as E-64 (Fig. 6) (Chandran et al., 2005; Schornberg et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2010). These findings suggest that additional proteolytic cleavage events, possibly coupled to a late step in the entry process, are required for ebolavirus and marburgvirus entry. To determine if LLOV GPCL also requires these additional cleavage events, or if it can instead fully bypass the requirement for endosomal cysteine proteases, we exposed cleaved rVSV-LLOV GPCL particles to cells pre-treated with E-64 (Fig. 6). Like its EBOV counterpart, rVSV-LLOV GPCL remained susceptible to E-64, indicating that all known filovirus entry mechanisms must undergo one or more additional cysteine-protease dependent steps that remain to be defined.

Fig. 6. Cleaved LLOV GP cannot overcome the entry requirement for endosomal cysteine cathepsins.

Vero cells were pre-treated with 1% DMSO (control) or E-64 (300 μM) for 4 h at 37°C, and then exposed to rVSVs bearing uncleaved (GP) or thermolysin-cleaved GP proteins (GPCL). Infected cells were visualized by fluorescence microscopy at 12–16 h post-infection. Averages ± SD (n=2) from a representative experiment are shown. *, p<0.05. ***, p<0.001.

LLOV GP-dependent entry requires the filovirus receptor, Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1)

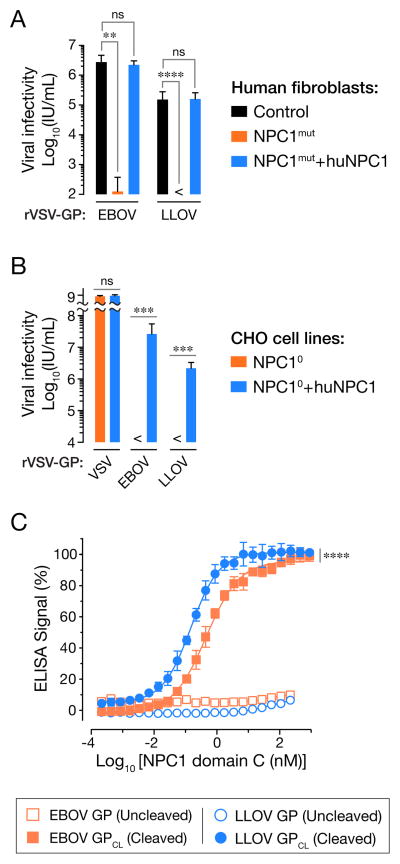

NPC1, a multipass membrane protein localized to late endosomes and involved in endosomal cholesterol trafficking (Carstea et al., 1997; Cruz et al., 2000; Davies et al., 2000), is a critical host factor for entry, infection, and pathogenesis by ebolaviruses and marburgviruses (Carette et al., 2011; Côté et al., 2011; Krishnan et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2012). Genetic loss of NPC1 function causes Niemann-Pick type C (NPC) disease in humans (Patterson et al., 2001; Walkley and Suzuki, 2004). To test if LLOV resembles other filoviruses in its requirement for NPC1, we exposed primary skin fibroblasts derived from NPC patients to rVSV-EBOV GP and rVSV-LLOV GP (Fig. 7A). We observed little or no infection with either virus in these NPC1-hypomorphic cells, whereas fibroblasts derived from a healthy individual were highly susceptible. Ectopic expression of WT human NPC1 in the NPC fibroblasts could confer full levels of EBOV GP- and LLOV GP-dependent infection (Fig. 7A). Similar results were obtained in a Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell line fully deficient for NPC1 (Fig. 7B). These findings provide evidence that LLOV, like all other known filoviruses, requires NPC1 for cell entry and infection.

Fig. 7. Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1) is an essential entry receptor for LLOV.

(A) Primary NPC1-mutant human fibroblasts from Niemann-Pick type C disease patients (NPC1mut), NPC1mut fibroblasts engineered to express WT human NPC1 (NPC1mut+huNPC1), and fibroblasts from control individuals were exposed to rVSVs bearing LLOV or EBOV GP. Infected cells were visualized by fluorescence microscopy at 12–16 h post-infection. Averages ± SD (n=4) are shown. (B) NPC1-deficient Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells and NPC10 cells engineered to express human NPC1 (NPC10+huNPC1) were exposed to rVSVs bearing LLOV or EBOV GP. Infected cells were visualized by fluorescence microscopy at 12–16 h post-infection. Averages ± SD (n=4) are shown. (A–B) Asterisks indicate measurements below the limit of detection. (C) Cleaved LLOV GP recognizes the second luminal domain (C) of NPC1. Biotin-labeled rVSVs bearing uncleaved or cleaved filovirus glycoproteins were captured onto streptavidin-coated plates, and binding of purified FLAG-tagged NPC1 domain C was detected by ELISA with an anti-FLAG antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. **, p<0.01. ***, p<0.001. ****, p<0.0001. ns, not significant. <, measurement below the threshold of detection.

Cleaved LLOV GP binds with high affinity to the second luminal domain of NPC1

Current evidence indicates that NPC1 is an endosomal receptor for filoviruses and marburgviruses that specifically and directly recognizes cleaved forms of ebolavirus and marburgvirus GP (GPCL) (Krishnan et al., 2012; K. Lee et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2012) (Ndungo and Chandran, unpublished). Moreover, we showed that this virus-receptor interaction is mediated by the second luminal domain of NPC1, domain C (Krishnan et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2012). To determine if LLOV GP can also directly recognize NPC1, we tested its capacity to capture purified human NPC1 domain C in an ELISA (Fig. 7C). As reported previously for uncleaved EBOV GP, un-cleaved LLOV GP did not appear to interact with NPC1 domain C. In contrast, LLOV GPCL, like its EBOV GPCL counterpart, could specifically capture NPC1 domain C (Fig. 7C). Interestingly, LLOV GPCL bound to human NPC1 with a higher apparent affinity than did EBOV GPCL (binding EC50 of 0.14±0.04 nM vs. 0.50±0.1 nM, respectively). These results show that NPC1 is a critical entry receptor for LLOV, and raise the possibility that it is a universal filovirus receptor.

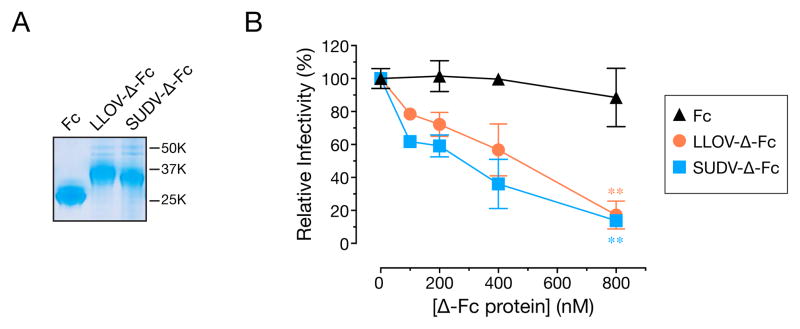

Properties of LLOV secreted glycoproteins: LLOV Δ-peptide blocks filovirus GP-dependent entry

In addition to the viral spike glycoprotein, the genomes of ebolaviruses, but not marburgviruses, encode two secreted glycoproteins that are not incorporated into viral particles–sGP and Δ-peptide (Sanchez et al., 1998; Volchkova et al., 1998; 1999). EBOV sGP shares its first 295 amino acid residues with the viral spike GP, but possesses a unique, highly O–glycosylated, C–terminal sequence. It is synthesized as a precursor, pre-sGP, which is translocated into the ER and transported to the Golgi apparatus, where it undergoes cleavage by furin. This cleavage step generates the mature sGP monomer and a small secreted peptide, Δ-peptide. Recent work suggests that sGP may serve as an immunologic decoy that redirects the host immune system away from neutralizing epitopes in the viral spike glycoprotein (Mohan et al., 2012). We previously found that the Δ-peptide could inhibit filovirus entry in tissue culture (Radoshitzky et al., 2011). However, the mechanism by which Δ-peptide inhibits viral entry and the physiological significance of this activity remain unknown.

Examination of the LLOV genome sequence indicated that it resembles ebolaviruses in encoding sGP and Δ-peptide. Accordingly, we expressed and purified a recombinant form of LLOV Δ-peptide fused to the fragment crystallizable region (Fc) of a human IgG1 (LLOV-Δ-Fc) (Fig. 8A), and examined its capacity to inhibit filovirus entry (Fig. 8B). Vero cells were pre-incubated with increasing concentrations of LLOV-Δ-Fc, and then exposed to Moloney murine leukemia virus pseudotypes bearing MARV GP. LLOV-Δ-Fc efficiently inhibited MARV GP-dependent entry, as described previously for its counterpart derived from an ebolavirus (SUDV-Δ-Fc) (Fig. 8B). Thus, LLOV resembles ebolaviruses not only in the organization of its GP gene, but also in the functional activity of one of the secreted glycoproteins that these viruses share with each other, but not with marburgviruses.

Fig. 8. Secreted LLOV glycoprotein, Δ peptide, inhibits LLOV GP-mediated entry.

(A) Recombinant LLOV and SUDV Δ-peptides fused to the Fc sequence of an immunoglobulin G were expressed and purified by protein A affinity chromatography, and visualized by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining. (B) Vero cells were treated with LLOV or SUDV Δ-Fc in increasing concentrations in the presence of eGFP-expressing Moloney murine leukemia virus particles bearing MARV GP. Cells were detached at 48 h post transduction, and the percentage of eGFP-positive cells was measured by flow cytometry. Averages ± SD (n=3) are shown. **, p<0.01.

Discussion

Lloviu virus (LLOV) is the founding member of the Cuevavirus genus in the family Filoviridae. Described in 2011, it is the first filovirus known that may be virulent in bats, and possibly the first known filovirus endemic to Europe (Negredo et al., 2011). Here, we demonstrate that the viral spike glycoprotein and small secreted glycoprotein (Δ-peptide) of LLOV, while divergent from those of other filoviruses in sequence and antigenicity, nevertheless closely resemble them in both structure and function.

The position of the polybasic recognition site for furin, which post-translationally cleaves the GP0 precursor to GP1+GP2 subunits, differs among filovirus GP proteins. While it is located at the C–terminal end of the mucin-like (Muc) domain in ebolaviruses, the furin site is positioned within this domain in marburgviruses (Fig. S1). Thus, Muc is contained entirely within GP1 in ebolaviruses, but is divided between GP1 and GP2 in marburgviruses. Interestingly, like MARV GP, LLOV GP is predicted to undergo furin cleavage within Muc (Fig. S1). The portion of Muc at the N–terminus of LLOV GP2 may play a role in stabilizing the GP1-GP2 trimer interface and and/or protecting it from antibody neutralization, as proposed for MARV GP (Erica O. Saphire, personal communication).

As shown previously for ebolaviruses and marburgviruses, and by Maruyama and coworkers for LLOV, LLOV GP-dependent entry requires both endosomal acid pH and the activity of cysteine cathepsins, a group of papain-superfamily proteases active in endo/lysosomal compartments (Figs. 3 and Fig. 4A) (Chandran et al., 2005; Misasi et al., 2012; Takada et al., 1997; Wool-Lewis and Bates, 1998). However, like RESTV and MARV (Misasi et al., 2012), LLOV does not require the activity of a specific enzyme, cathepsin B (CatB), implicated in entry by EBOV, BDBV, and TAFV (Fig. 4B). We previously showed that changes in amino acid residues near the N–terminus of GP1, and at or near the GP1-GP2 intersubunit interface afford CatB-independent entry by EBOV (Wong et al., 2010). One such residue is amino acid 47 in GP1, which is Asp in CatB-dependent GP proteins, and Glu or Val in CatB-independent GP proteins (Glu in SUDV, RESTV, and MARV; Val in LLOV) (Fig. S2). Both Asp 47→Glu and Asp 47→Val render EBOV CatB-independent, strongly suggesting that this sequence polymorphism is at least partly responsible for CatB-independent entry mediated by LLOV GP.

Cysteine cathepsins are required for filovirus entry at least in part because they cleave GP1 to remove surface-exposed C–terminal sequences (Muc and glycan cap) (Chandran et al., 2005; Dube et al., 2009; J. E. Lee et al., 2008; Schornberg et al., 2006). GP cleavage unmasks the receptor-binding site in GP1 (see below) (J. E. Lee et al., 2008; Miller et al., 2012), and likely alleviates both covalent and non-covalent constraints on GP rearrangement during viral membrane fusion (Brecher et al., 2012; Dube et al., 2009; Wong et al., 2010). We found that LLOV GP also undergoes cleavage in vitro to generate an intermediate (GPCL) comprising the conserved structural core of the GP1–GP2 trimer. Interestingly, however, LLOV GP resembled MARV GP in being much more protease-sensitive than EBOV GP (Fig. 5) (Miller et al., 2012) (Wec and Chandran, unpublished). LLOV GP thus exemplifies the tendency for CatB-independent filovirus glycoproteins to be more susceptible to proteolytic cleavage than their CatB-dependent counterparts, suggesting that protease requirements during filovirus entry are linked to the conformational flexibility of the GP pre-fusion spike. While the selective forces that set the balance between GP-dependent viral stability and infectivity remain undefined, these findings raise the possibility that LLOV (and MARV) might be able to enter and infect tissues with low levels of cysteine protease activity more efficiently than can EBOV. Alternatively, the variations in host protease dependence and sensitivity observed among filovirus glycoproteins may simply be collateral effects of other adaptive changes in GP (driven by host immune pressure, for example).

Previous work showed that in vitro GP→GPCL cleavage does not bypass the entry requirement for cysteine cathepsin activity, at least for ebolaviruses and marburgviruses (Chandran et al., 2005; Schornberg et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2010). Here, we demonstrate that LLOV GP fully resembles other filovirus glycoproteins in this respect (Fig. 6). Because VSVs containing EBOV GPCL arrest in late endosomal compartments in cells bereft of cysteine cathepsin activity (Chandran, data not shown), current evidence suggests the existence of at least one cysteine protease-dependent step in filovirus entry downstream of GP→GPCL cleavage. This enigmatic protease-dependent late step in entry thus appears to be shared by all known filoviruses.

In this study, we demonstrated that LLOV GP-dependent entry also requires the ebolavirus and marburgvirus receptor NPC1, and can utilize the human ortholog of this protein (Fig. 7A–B). Moreover, like all other filoviruses examined to date (Krishnan et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2012), LLOV GPCL, but not uncleaved GP, bound directly to the second luminal domain of NPC1, domain C. Unexpectedly, the affinity of LLOV GPCL for human NPC1 appeared to be greater than that of the corresponding interaction between EBOV GPCL and NPC1 (Fig. 7C). These findings suggest that the virus-NPC1 interaction would not impose a barrier to infection of humans and non-human primates by LLOV. Finally, we note that while we have examined only human NPC1 in this report, studies of the interaction between Schreiber’s long-fingered bat NPC1 and the glycoproteins of LLOV and other filoviruses are also warranted, because they may reveal host species- and viral isolate-dependent differences in the nature and strength of the filovirus-receptor interaction, with potential implications for LLOV’s virulence in a bat host. Indeed, such a difference might explain the intriguing observation that LLOV GP-dependent entry is relatively more efficient in a Schreiber’s long-fingered bat cell (Maruyama et al., 2013). Taken together, our work supports the hypothesis that NPC1 is a universal receptor for filoviruses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rohini G. Sandesara and Tyler Krause for excellent technical support, and Jiro Wada (Integrated Research Facility at Fort Detrick) for help with creating supplementary figures. We also thank Margaret C. Kielian (Einstein) and Dan S. Ory (Washington University School of Medicine) for their gift of the FD11 and M12 cell lines, respectively. This work was supported by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and by NIH grant R01 AI088027 (to K.C.). K.C. and R.K.J. were additionally supported by a fellowship from the Irma T. Hirschl/Monique Weill-Caulier Trust (to K.C.). J.M.D. was supported by JSTO-CBD Defense Threat Reduction Agency project CB3947. A.N. was supported by a RICET Network on Tropical Diseases-ISCIII. E.R.A. was supported by a Sara Borrel programme FIS-Spain. G.P. was supported by Defense Threat Reduction Agency Project 1881290. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the US Department of the Army, the US Department of Defense, or the US Department of Health and Human Services, or of the institutions and companies affiliated with the authors. YC, EP, and JHK performed this work as employees of Tunnell Government Services, Inc., a subcontractor to Battelle Memorial Institute, under Battelle’s prime contract with NIAID, under Contract No. HHSN272200700016I.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams MJ, Lefkowitz EJ, King AMQ, Carstens EB. Ratification vote on taxonomic proposals to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Arch Virol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00705-014-2114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez CP, Lasala F, Carrillo J, Muñiz O, Corbí AL, Delgado R. C-type lectins DC-SIGN and L-SIGN mediate cellular entry by Ebola virus in cis and in trans. Journal of Virology. 2002;76:6841–6844. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6841-6844.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amman BR, Carroll SA, Reed ZD, Sealy TK, Balinandi S, Swanepoel R, Kemp A, Erickson BR, Comer JA, Campbell S, Cannon DL, Khristova ML, Atimnedi P, Paddock CD, Kent Crockett RJ, Flietstra TD, Warfield KL, Unfer R, Katongole-Mbidde E, Downing R, Tappero JW, Zaki SR, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG, Nichol ST, Towner JS. Seasonal Pulses of Marburg Virus Circulation in Juvenile Rousettus aegyptiacus Bats Coincide with Periods of Increased Risk of Human Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002877. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale S, Liu T, Li S, Wang Y, Abelson D, Fusco M, Woods VL, Saphire EO. Ebola virus glycoprotein needs an additional trigger, beyond proteolytic priming for membrane fusion. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrette RW, Metwally SA, Rowland JM, Xu L, Zaki SR, Nichol ST, Rollin PE, Towner JS, Shieh WJ, Batten B, Sealy TK, Carrillo C, Moran KE, Bracht AJ, Mayr GA, Sirios-Cruz M, Catbagan DP, Lautner EA, Ksiazek TG, White WR, McIntosh MT. Discovery of swine as a host for the Reston ebolavirus. Science. 2009;325:204–206. doi: 10.1126/science.1172705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecher M, Schornberg KL, Delos SE, Fusco ML, Saphire EO, White JM. Cathepsin cleavage potentiates the Ebola virus glycoprotein to undergo a subsequent fusion-relevant conformational change. Journal of Virology. 2012;86:364–372. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05708-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carette JE, Raaben M, Wong AC, Herbert AS, Obernosterer G, Mulherkar N, Kuehne AI, Kranzusch PJ, Griffin AM, Ruthel G, Dal Cin P, Dye JM, Whelan SP, Chandran K, Brummelkamp TR. Ebola virus entry requires the cholesterol transporter Niemann-Pick C1. Nature. 2011;477:340–343. doi: 10.1038/nature10348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstea ED, Morris JA, Coleman KG, Loftus SK, Zhang D, Cummings C, Gu J, Rosenfeld MA, Pavan WJ, Krizman DB, Nagle J, Polymeropoulos MH, Sturley SL, Ioannou YA, Higgins ME, Comly M, Cooney A, Brown A, Kaneski CR, Blanchette-Mackie EJ, Dwyer NK, Neufeld EB, Chang TY, Liscum L, Strauss JF, Ohno K, Zeigler M, Carmi R, Sokol J, Markie D, O’Neill RR, van Diggelen OP, Elleder M, Patterson MC, Brady RO, Vanier MT, Pentchev PG, Tagle DA. Niemann-Pick C1 disease gene: homology to mediators of cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 1997;277:228–231. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran K, Sullivan NJ, Felbor U, Whelan SP, Cunningham JM. Endosomal proteolysis of the Ebola virus glycoprotein is necessary for infection. Science. 2005;308:1643–1645. doi: 10.1126/science.1110656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté M, Misasi J, Ren T, Bruchez A, Lee K, Filone CM, Hensley L, Li Q, Ory D, Chandran K, Cunningham J. Small molecule inhibitors reveal Niemann-Pick C1 is essential for Ebola virus infection. Nature. 2011;477:344–348. doi: 10.1038/nature10380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz JC, Sugii S, Yu C, Chang TY. Role of Niemann-Pick type C1 protein in intracellular trafficking of low density lipoprotein-derived cholesterol. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4013–4021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies JP, Chen FW, Ioannou YA. Transmembrane molecular pump activity of Niemann-Pick C1 protein. Science. 2000;290:2295–2298. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5500.2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias JM, Kuehne AI, Abelson DM, Bale S, Wong AC, Halfmann P, Muhammad MA, Fusco ML, Zak SE, Kang E, Kawaoka Y, Chandran K, Dye JM, Saphire EO. A shared structural solution for neutralizing ebolaviruses. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1424–1427. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube D, Brecher MB, Delos SE, Rose SC, Park EW, Schornberg KL, Kuhn JH, White JM. The primed ebolavirus glycoprotein (19-kilodalton GP1,2): sequence and residues critical for host cell binding. Journal of Virology. 2009;83:2883–2891. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01956-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann H, Geisbert TW. Ebola haemorrhagic fever. Lancet. 2011;377:849–862. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60667-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann H, Volchkov VE, Volchkova VA, Ströher U, Klenk H-D. Biosynthesis and role of filoviral glycoproteins. 2001;82:2839–2848. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-12-2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann H, Will C, Schikore M, Slenczka W, Klenk HD. Glycosylation and oligomerization of the spike protein of Marburg virus. Virology. 1991;182:353–356. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90680-A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francica JR, Varela-Rohena A, Medvec A, Plesa G, Riley JL, Bates P. Steric shielding of surface epitopes and impaired immune recognition induced by the ebola virus glycoprotein. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001098. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon VM, Klimpel KR, Arora N, Henderson MA, Leppla SH. Proteolytic activation of bacterial toxins by eukaryotic cells is performed by furin and by additional cellular proteases. Infect Immun. 1995;63:82–87. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.82-87.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman AL, Towner JS, Nichol ST. Ebola and marburg hemorrhagic fever. Clin Lab Med. 2010;30:161–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood CL, Abraham J, Boyington JC, Leung K, Kwong PD, Nabel GJ. Biochemical and structural characterization of cathepsin L-processed Ebola virus glycoprotein: implications for viral entry and immunogenicity. Journal of Virology. 2010;84:2972–2982. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02151-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffers SA, Sanders DA, Sanchez A. Covalent modifications of the ebola virus glycoprotein. Journal of Virology. 2002;76:12463–12472. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12463-12472.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan A, Miller EH, Herbert AS, Ng M, Ndungo E, Whelan SP, Dye JM, Chandran K. Niemann-Pick C1 (NPC1)/NPC1-like1 chimeras define sequences critical for NPC1’s function as a flovirus entry receptor. Viruses. 2012;4:2471–2484. doi: 10.3390/v4112471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn JH, Becker S. FAMILY FILOVIRIDAE. In: King AM, Lefkowitz E, Adams MJ, Carstens EB, editors. Virus Taxonomy - Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier/Academic Press; London: 2011. pp. 665–671. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn JH, Becker S, Ebihara H, Geisbert TW, Johnson KM, Kawaoka Y, Lipkin WI, Negredo AI, Netesov SV, Nichol ST, Palacios G, Peters CJ, Tenorio A, Volchkov VE, Jahrling PB. Proposal for a revised taxonomy of the family Filoviridae: classification, names of taxa and viruses, and virus abbreviations. Arch Virol. 2010;155:2083–2103. doi: 10.1007/s00705-010-0814-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JE, Fusco ML, Hessell AJ, Oswald WB, Burton DR, Saphire EO. Structure of the Ebola virus glycoprotein bound to an antibody from a human survivor. Nature. 2008;454:177–182. doi: 10.1038/nature07082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JE, Saphire EO. Neutralizing ebolavirus: structural insights into the envelope glycoprotein and antibodies targeted against it. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:408–417. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Ren T, Côté M, Gholamreza B, Misasi J, Bruchez A, Cunningham J. Inhibition of Ebola Virus Infection: Identification of Niemann-Pick C1 as the Target by Optimization of a Chemical Probe. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2013;4:239–243. doi: 10.1021/ml300370k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy EM, Epelboin A, Mondonge V, Pourrut X, Gonzalez J-P, Muyembe-Tamfum J-J, Formenty P. Human Ebola outbreak resulting from direct exposure to fruit bats in Luebo, Democratic Republic of Congo, 2007. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2009;9:723–728. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2008.0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy EM, Kumulungui B, Pourrut X, Rouquet P, Hassanin A, Yaba P, Délicat A, Paweska JT, Gonzalez JP, Swanepoel R. Fruit bats as reservoirs of Ebola virus. Nature. 2005;438:575–576. doi: 10.1038/438575a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacNeil A, Farnon EC, Morgan OW, Gould P, Boehmer TK, Blaney DD, Wiersma P, Tappero JW, Nichol ST, Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE. Filovirus outbreak detection and surveillance: lessons from Bundibugyo. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(Suppl 3):S761–7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Serrano J, Zang T, Bieniasz PD. HIV-1 and Ebola virus encode small peptide motifs that recruit Tsg101 to sites of particle assembly to facilitate egress. Nat Med. 2001;7:1313–1319. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama J, Miyamoto H, Kajihara M, Ogawa H, Maeda K, Sakoda Y, Yoshida R, Takada A. Characterization of the Envelope Glycoprotein of a Novel Filovirus, Lloviu Virus. Journal of Virology. 2013;88:99–109. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02265-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzi A, Möller P, Hanna SL, Harrer T, Eisemann J, Steinkasserer A, Becker S, Baribaud F, Pöhlmann S. Analysis of the interaction of Ebola virus glycoprotein with DC-SIGN (dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule 3-grabbing nonintegrin) and its homologue DC-SIGNR. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(Suppl 2):S237–46. doi: 10.1086/520607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzi A, Reinheckel T, Feldmann H. Cathepsin B & L are not required for ebola virus replication. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EH, Chandran K. Filovirus entry into cells - new insights. Curr Opin Virol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller EH, Obernosterer G, Raaben M, Herbert AS, Deffieu MS, Krishnan A, Ndungo E, Sandesara RG, Carette JE, Kuehne AI, Ruthel G, Pfeffer SR, Dye JM, Whelan SP, Brummelkamp TR, Chandran K. Ebola virus entry requires the host-programmed recognition of an intracellular receptor. EMBO J. 2012;31:1947–1960. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda MEG, Yoshikawa Y, Manalo DL, Calaor AB, Miranda NLJ, Cho F, Ikegami T, Ksiazek TG. Chronological and spatial analysis of the 1996 Ebola Reston virus outbreak in a monkey breeding facility in the Philippines. Exp Anim. 2002;51:173–179. doi: 10.1538/expanim.51.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misasi J, Chandran K, Yang J-Y, Considine B, Filone CM, Côté M, Sullivan N, Fabozzi G, Hensley L, Cunningham J. Filoviruses Require Endosomal Cysteine Proteases for Entry But Exhibit Distinct Protease Preferences. Journal of Virology. 2012 doi: 10.1128/JVI.06346-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan GS, Li W, Ye L, Compans RW, Yang C. Antigenic subversion: a novel mechanism of host immune evasion by Ebola virus. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1003065. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa S, Saijo M, Kurane I. Current knowledge on lower virulence of Reston Ebola virus (in French: Connaissances actuelles sur la moindre virulence du virus Ebola Reston) Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;30:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulherkar N, Raaben M, de la Torre J-C, Whelan SP, Chandran K. The Ebola virus glycoprotein mediates entry via a non-classical dynamin-dependent macropinocytic pathway. Virology. 2011;419:72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanbo A, Imai M, Watanabe S, Noda T, Takahashi K, Neumann G, Halfmann P, Kawaoka Y. Ebolavirus is internalized into host cells via macropinocytosis in a viral glycoprotein-dependent manner. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001121. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negredo A, Palacios G, Vázquez-Morón S, González F, Dopazo H, Molero F, Juste J, Quetglas J, Savji N, de la Cruz Martínez M, Herrera JE, Pizarro M, Hutchison SK, Echevarría JE, Lipkin WI, Tenorio A. Discovery of an ebolavirus-like filovirus in europe. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002304. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda T, Sagara H, Suzuki E, Takada A, Kida H, Kawaoka Y. Ebola virus VP40 drives the formation of virus-like filamentous particles along with GP. Journal of Virology. 2002;76:4855–4865. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.10.4855-4865.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olival KJ, Hayman DTS. Filoviruses in bats: current knowledge and future directions. Viruses. 2014;6:1759–1788. doi: 10.3390/v6041759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paessler S, Walker DH. Pathogenesis of the viral hemorrhagic fevers. Annu Rev Pathol. 2013;8:411–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-164041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson MC, Vanier MT, Suzuki K, Morris JA, Carstea ED, Neufeld EB, Blanchette-Mackie EJ, Pentchev PG. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. New York: 2001. Niemann-Pick Disease type C: A lipid trafficking disorder. [Google Scholar]

- Pourrut X, Kumulungui B, Wittmann T, Moussavou G, Délicat A, Yaba P, Nkoghe D, Gonzalez J-P, Leroy EM. The natural history of Ebola virus in Africa. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:1005–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourrut X, Souris M, Towner JS, Rollin PE, Nichol ST, Gonzalez J-P, Leroy E. Large serological survey showing cocirculation of Ebola and Marburg viruses in Gabonese bat populations, and a high seroprevalence of both viruses in Rousettus aegyptiacus. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:159. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radoshitzky SR, Warfield KL, Chi X, Dong L, Kota K, Bradfute SB, Gearhart JD, Retterer C, Kranzusch PJ, Misasi JN, Hogenbirk MA, Wahl-Jensen V, Volchkov VE, Cunningham JM, Jahrling PB, Aman MJ, Bavari S, Farzan M, Kuhn JH. Ebolavirus delta-peptide immunoadhesins inhibit marburgvirus and ebolavirus cell entry. Journal of Virology. 2011;85:8502–8513. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02600-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynard O, Borowiak M, Volchkova VA, Delpeut S, Mateo M, Volchkov VE. Ebolavirus glycoprotein GP masks both its own epitopes and the presence of cellular surface proteins. Journal of Virology. 2009;83:9596–9601. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00784-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollin PE, Williams RJ, Bressler DS, Pearson S, Cottingham M, Pucak G, Sanchez A, Trappier SG, Peters RL, Greer PW, Zaki S, Demarcus T, Hendricks K, Kelley M, Simpson D, Geisbert TW, Jahrling PB, Peters CJ, Ksiazek TG. Ebola (subtype Reston) virus among quarantined nonhuman primates recently imported from the Philippines to the United States. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(Suppl 1):S108–14. doi: 10.1086/514303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed MF, Kolokoltsov AA, Albrecht T, Davey RA. Cellular entry of ebola virus involves uptake by a macropinocytosis-like mechanism and subsequent trafficking through early and late endosomes. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001110. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez A, Yang ZY, Xu L, Nabel GJ, Crews T, Peters CJ. Biochemical analysis of the secreted and virion glycoproteins of Ebola virus. Journal of Virology. 1998;72:6442–6447. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6442-6447.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schornberg K, Matsuyama S, Kabsch K, Delos S, Bouton A, White J. Role of endosomal cathepsins in entry mediated by the Ebola virus glycoprotein. Journal of Virology. 2006;80:4174–4178. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.8.4174-4178.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidah NG, Sadr MS, Chrétien M, Mbikay M. The multifaceted proprotein convertases: their unique, redundant, complementary, and opposite functions. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288:21473–21481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.481549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanepoel R, Leman PA, Burt FJ, Zachariades NA, Braack LE, Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, Zaki SR, Peters CJ. Experimental inoculation of plants and animals with Ebola virus. Emerging Infect Dis. 1996;2:321–325. doi: 10.3201/eid0204.960407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada A, Robison C, Goto H, Sanchez A, Murti KG, Whitt MA, Kawaoka Y. A system for functional analysis of Ebola virus glycoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14764–14769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towner JS, Amman BR, Sealy TK, Carroll SAR, Comer JA, Kemp A, Swanepoel R, Paddock CD, Balinandi S, Khristova ML, Formenty PBH, Albarino CG, Miller DM, Reed ZD, Kayiwa JT, Mills JN, Cannon DL, Greer PW, Byaruhanga E, Farnon EC, Atimnedi P, Okware S, Katongole-Mbidde E, Downing R, Tappero JW, Zaki SR, Ksiazek TG, Nichol ST, Rollin PE. Isolation of genetically diverse Marburg viruses from Egyptian fruit bats. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000536. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk V, Stoka V, Vasiljeva O, Renko M, Sun T, Turk B, Turk D. Cysteine cathepsins: from structure, function and regulation to new frontiers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1824:68–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volchkov VE, Feldmann H, Volchkova VA, Klenk HD. Processing of the Ebola virus glycoprotein by the proprotein convertase furin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5762–5767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volchkov VE, Volchkova VA, Ströher U, Becker S, Dolnik O, Cieplik M, Garten W, Klenk HD, Feldmann H. Proteolytic processing of Marburg virus glycoprotein. Virology. 2000;268:1–6. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volchkova VA, Feldmann H, Klenk HD, Volchkov VE. The nonstructural small glycoprotein sGP of Ebola virus is secreted as an antiparallel-orientated homodimer. Virology. 1998;250:408–414. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volchkova VA, Klenk HD, Volchkov VE. Delta-peptide is the carboxyterminal cleavage fragment of the nonstructural small glycoprotein sGP of Ebola virus. Virology. 1999;265:164–171. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkley SU, Suzuki K. Consequences of NPC1 and NPC2 loss of function in mammalian neurons. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1685:48–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan SP, Ball LA, Barr JN, Wertz GT. Efficient recovery of infectious vesicular stomatitis virus entirely from cDNA clones. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:8388–8392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JM, Delos SE, Brecher M, Schornberg K. Structures and mechanisms of viral membrane fusion proteins: multiple variations on a common theme. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;43:189–219. doi: 10.1080/10409230802058320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong AC, Sandesara RG, Mulherkar N, Whelan SP, Chandran K. A forward genetic strategy reveals destabilizing mutations in the Ebolavirus glycoprotein that alter its protease dependence during cell entry. Journal of Virology. 2010;84:163–175. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01832-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wool-Lewis RJ, Bates P. Characterization of Ebola virus entry by using pseudotyped viruses: identification of receptor-deficient cell lines. Journal of Virology. 1998;72:3155–3160. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.3155-3160.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.