Abstract

Objective

To model morphologic assessments of embryo quality predictive of live birth

Design

Longitudinal cohort using cycles reported in the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Clinic Outcomes Reporting System between 2007 and 2011.

Setting

Clinic-based data

Patients

Fresh autologous ART cycles with embryo transfers on day 3 or day 5 and morphologic assessments reported (25,409 cycles with one embryo transferred and 96,093 cycles with two embryos transferred). Live birth rates were modeled by morphological assessments using backward-stepping logistic regression for cycle 1 and over five cycles, separately for day 3 and day 5 transfers and number of embryos transferred (1 or 2). Additional models for each day of transfer also included number of oocytes retrieved and number of embryos cryopreserved.

Interventions

None

Main Outcome Measures

Live births

Results

Morphologic assessments of grade, stage, fragmentation, and symmetry were significant for the day 3 models; grade, stage and trophectoderm were significant in the day 5 model; inner cell mass was significant in the models when two embryos were transferred. Number of oocytes retrieved and number of embryos cryopreserved were significant for both day 3 and day 5 models.

Conclusions

These findings confirm the significant association between embryo quality parameters reported to SART CORS and live birth rate following ART.

Keywords: embryo morphology, embryo symmetry, embryo fragmentation, trophoblast, live birth rate

Introduction

Accurate prediction of live birth rates with assisted reproductive technology (ART) has important value for both the patients and their clinicians. Morphology of the embryos in the cohort, and particularly of the transferred embryos, is an important factor associated with live birth rates in ART (1–3). Different systems have been developed to assess embryo morphology (4, 5) including assessing the developmental stage of the embryo as well as parameters specific to the number of days in culture, such as symmetry of the blastomeres on day 3 or quality of the inner cell mass for day 5 embryos. More recent time-lapse imaging systems to assess the association between developmental kinetics and implantation potential are being developed (6) but evaluation of the embryos shortly before transfer remains routine in many clinics.

Although embryo quality, as assessed by morphologic parameters recorded before transfer, is significantly related to implantation potential and subsequent live birth, a standardized system for collecting morphology fields into the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Clinic Outcome System (SART CORS) was only developed recently (7, 8). Data on morphologic assessments has been reported to SART CORS since 2007; reporting of these data became mandatory in 2010. The grading system records embryo stage (1 cell through hatching blastocyst), overall grade (good, fair, poor), symmetry and range of percent fragmentation for transfers on days 2 and 3; morula compaction and fragmentation on day 4, and inner cell mass and trophectoderm quality on days 5–7. Additional morphologic features such as vacuolization and granularity are not recorded separately but can be included in the overall grade assessment. The SART CORS grading system showed validity in terms of predicting live birth in early studies evaluating day 3 embryos (9, 10). The present analysis expands this evaluation to day 3 and day 5 embryos using additional years of data and more comprehensive models. The goal of the present study, which is part of a series of studies, was to evaluate the contribution of embryo morphology to a comprehensive prediction model for live birth and multiple birth that will ultimately be able to be used by clinicians to help guide clinical and patient decision making.

Materials and Methods

The data source for this study was the SART CORS, which contains comprehensive data from more than 90% of all clinics performing ART in the US. The data in the SART CORS are reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in compliance with the Fertility Clinic Success Rate and Certification Act of 1992 (Public Law 102–493) and validated annually (11, 12) with some clinics having on site visits for chart review based on an algorithm for clinic selection. During each visit, data reported by the clinic were compared with information recorded in patients’ charts. In 2010, records for 2,070 cycles at 35 clinics were randomly selected for full validation, along with 135 embryo banking cycles (10). The full validation included review of 1,352 cycles for which a pregnancy was reported; of which 446 were multiple-fetus pregnancies. Nine out of 10 data fields selected for validation were found to have discrepancy rates of ≤5%. Morphology fields were not among the fields chosen for validation. The data for this study included cycles reported to the SART CORS between 2007 and 2011, and was limited to fresh autologous cycles with morphologic assessments, with 1 or 2 embryos transferred on day 3 or day 5. Due to small numbers, models for day 2, 4, and 6 were not included. Excluded were cycles which were cancelled or designated as research, and those with embryo banking or which used gestational carriers. Cycle 1 refers to the first cycle for women who did not have prior ART treatment. Cycles 2–5 were numbered sequentially following the first cycle; therefore, cycle 2 with a day 5 transfer will be the second cycle for the subject, but may not be her second cycle with a day 5 transfer.

The dependent variable of live birth was defined as a live birth with at least 300 grams birthweight and length of gestation of at least 154 days (22 weeks). Live birth rates were modeled by morphological assessments using backward-stepping logistic regression, separately for each day of transfer (3 and 5) and number of embryos transferred (1 or 2). The independent variables of day-specific morphologic assessments included grade and stage for all embryos, fragmentation and symmetry for day 3 models; and inner cell mass and trophectoderm for day 5 models. With two embryos, the morphologic measures of the embryo with the more advanced stage was used for modeling; when the two embryos had the same stage, the better morphologic measure (i.e., Good>Fair>Poor) was used. Additional models of live birth were also developed by day of transfer and number of embryos transferred to evaluate the effect of number of oocytes retrieved (1–5, 6–10, 11–15, and ≥16) and number of embryos cryopreserved (0, 1, ≥2). Model results are presented as adjusted odds ratios (AOR, <1 signifies worse outcome) and 95% confidence intervals. The study was approved by the Committees for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College, and Michigan State University, respectively, and was analyzed using SAS 9.2 software (Cary, NC).

Results

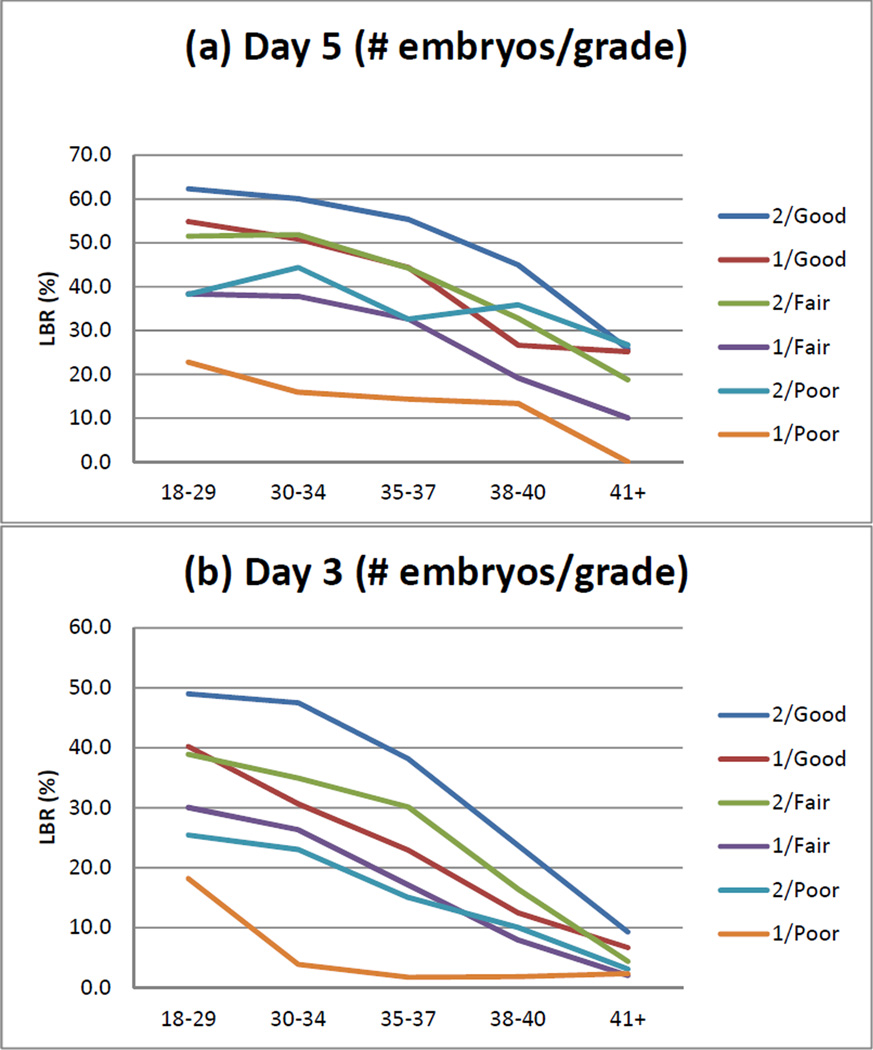

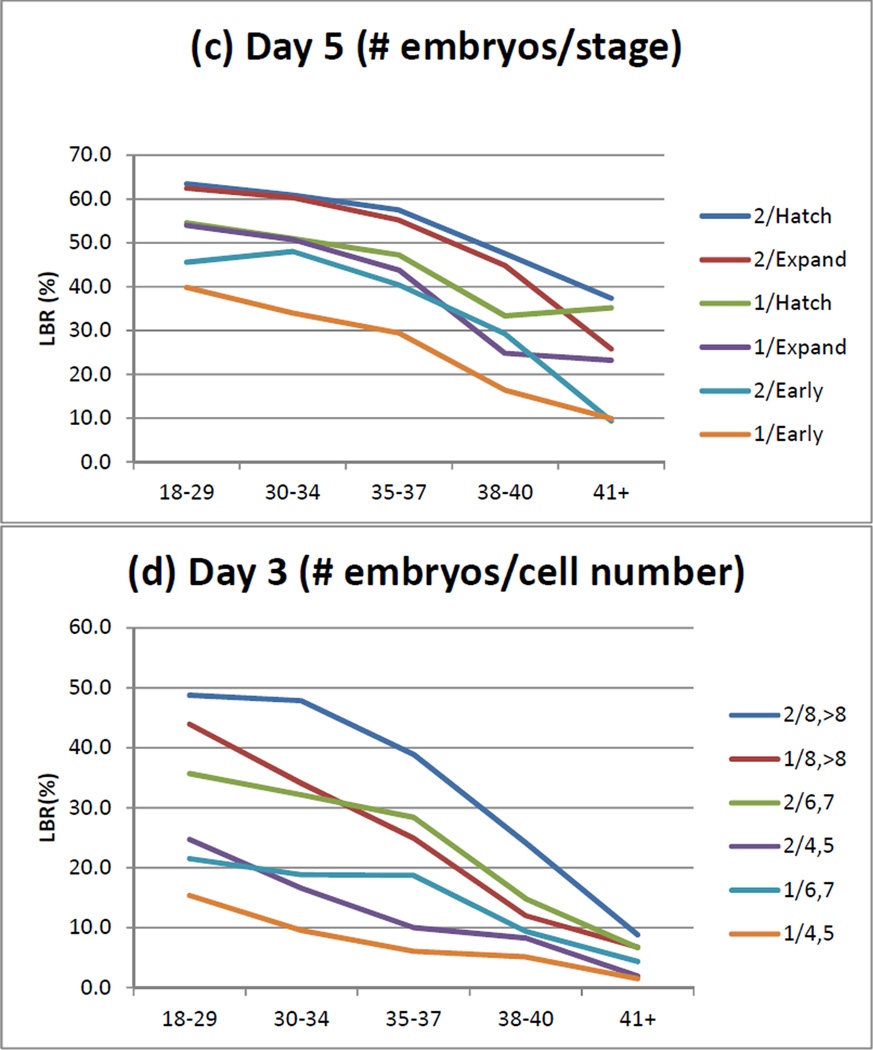

The study population included 121,502 fresh autologous cycles with morphologic assessments reported, 51,783 of which had transfers on day 3 and 69,719 with transfers on day 5. The description of the study population is shown in Table 1. The models of live birth by day of transfer and number of embryos transferred are shown in Table 2. For day 3 transfers, embryo grade, stage (i.e., cell number) and fragmentation were consistently significant factors with both one and two embryos transferred, for cycle 1 and over all five cycles; symmetry was significant for two embryos in cycle 1 and for both one and two embryos over all five cycles. For day 5 transfers, embryo grade was significant for one embryo in cycle 1 and both one and two embryos over all five cycles; inner cell mass was significant with two embryos for cycle 1 and over five cycles; and embryo stage and trophectoderm were consistently significant factors with both one and two embryos transferred, for cycle 1 and over five cycles. The probability of a live birth decreased with advancing cycle number for both day 3 and day 5 transfers up to and including five cycles (AORs of 0.54–0.78 and 0.67–0.79, respectively, for one and two embryos). The models of live birth by day of transfer, number of embryos transferred, and oocytes retrieved and embryos cryopreserved are shown in Table 3. More oocytes retrieved and more embryos cryopreserved were each associated with an improved live birth rate for cycles having either a day 3 or a day 5 transfer. The effects of grade and stage on live birth rate are consistent across age (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Description of the Study Population by Day of Transfer and Number of Embryos Transferred

| Day of Transfer | Day 3 | Day 5 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Embryos Transferred | One | Two | One | Two | |

| N, women | 4,519 | 17,518 | 7,688 | 28,796 | |

| Total number of cycles, cycle 1–5 | 11,823 | 39,960 | 13,586 | 56,133 | |

| Live Birth Rate (%), 1st cycle | 19.7 | 37.8 | 46.4 | 55.3 | |

| Live birth rate per cycle – cycles 1–5 (%) | 16.6 | 35.1 | 45.0 | 53.3 | |

| Woman’s Age (%) | <30 | 12.4 | 19.1 | 24.9 | 24.1 |

| 30–34 | 31.0 | 40.4 | 48.5 | 41.9 | |

| 35–37 | 19.7 | 22.5 | 18.0 | 21.1 | |

| 38–40 | 19.3 | 12.0 | 6.2 | 11.0 | |

| 41–43 | 13.9 | 4.9 | 2.0 | 1.8 | |

| ≥44 | 3.7 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |

| Race/Ethnicity (%, excl. unknown) | White | 68.0 | 74.5 | 72.0 | 70.6 |

| Hispanic | 8.6 | 6.3 | 5.6 | 8.4 | |

| Asian | 12.8 | 10.4 | 13.6 | 11.3 | |

| Black | 8.9 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 7.6 | |

| Mixed | 1.3 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.4 | |

| Other | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | |

| Unknown | 33.6 | 33.5 | 35.0 | 31.3 | |

| Diagnosis (%) | Male factor | 39.2 | 44.4 | 40.0 | 44.5 |

| Endometriosis | 10.2 | 11.7 | 8.5 | 10.7 | |

| Ovulation disorders | 9.0 | 11.9 | 17.8 | 17.8 | |

| Diminished ovarian reserve | 30.0 | 15.3 | 6.9 | 9.4 | |

| Tubal Ligation | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 4.2 | |

| Tubal Hydrosalpinx | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.6 | |

| Tubal Other | 13.6 | 14.6 | 13.7 | 14.5 | |

| Uterine | 5.1 | 3.8 | 5.0 | 3.9 | |

| Unexplained | 12.0 | 14.2 | 14.4 | 12.3 | |

| Other | 9.9 | 8.7 | 15.7 | 11.7 | |

| Cycles (%) | 1 | 55.7 | 62.6 | 75.7 | 70.8 |

| 2 | 23.6 | 20.8 | 12.9 | 15.9 | |

| 3 | 11.7 | 9.9 | 6.3 | 7.8 | |

| 4 | 5.9 | 4.5 | 3.3 | 3.7 | |

| 5 | 3.1 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 1.8 | |

Table 2.

Models of Live Birth by Day of Transfer and Number of Embryos Transferred

| Cycle 1 | Over Five Cycles | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAY 3 | One Embryo | Two Embryos | One Embryo | Two Embryos | |||||||||

| AOR | 95% CI | P Value | AOR | 95% CI | P Value | AOR | 95% CI | P Value | AOR | 95% CI | P Value | ||

| Grade | Good | 1.00 | Reference | 0.02 | 1.00 | Reference | 0.006 | 1.00 | Reference | 0.009 | 1.00 | Reference | 0.0001 |

| Fair | 1.06 | 0.88,1.27 | 0.88 | 0.80,0.97 | 1.17 | 1.02,1.34 | 0.92 | 0.86,0.97 | |||||

| Poor | 0.45 | 0.25,0.82 | 0.72 | 0.55,0.95 | 0.78 | 0.55,1.11 | 0.72 | 0.61,0.85 | |||||

| Stage | 4 cells | 0.22 | 0.15, 0.33 | <0.0001 | 0.18 | 0.12, 0.26 | <0.0001 | 0.21 | 0.17, 0.28 | <0.0001 | 0.18 | 0.14, 0.23 | <0.0001 |

| (i.e., Cell Number) | 5 cells | 0.23 | 0.14, 0.36 | 0.30 | 0.23, 0.39 | 0.20 | 0.15, 0.27 | 0.29 | 0.24, 0.34 | ||||

| 6 cells | 0.45 | 0.34, 0.58 | 0.45 | 0.39, 0.52 | 0.40 | 0.33, 0.47 | 0.39 | 0.35, 0.43 | |||||

| 7 cells | 0.54 | 0.42, 0.69 | 0.70 | 0.63, 0.79 | 0.60 | 0.51, 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.66, 0.77 | |||||

| 8 cells | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | |||||

| >8 cells | 0.64 | 0.48, 0.85 | 0.95 | 0.87, 1.03 | 0.64 | 0.53, 0.77 | 0.98 | 0.92, 1.04 | |||||

| Fragmentation | 0% | 1.00 | Reference | 0.0007 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 |

| 1–10% | 0.85 | 0.73,1.00 | 1.11 | 1.02,1.20 | 0.86 | 0.77,0.96 | 1.22 | 1.15,1.29 | |||||

| 11–25% | 0.59 | 0.44,0.79 | 0.86 | 0.76,0.97 | 0.56 | 0.46,0.67 | 1.00 | 0.92,1.09 | |||||

| >25% | 0.34 | 0.14,0.82 | 0.94 | 0.70,1.27 | 0.38 | 0.22,0.66 | 0.94 | 0.77,1.16 | |||||

| Symmetry | Perfect Symmetry | --- | --- | NS | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 | 1.00 | Reference | 0.001 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 |

| Moderate Asymmetry | --- | --- | 0.84 | 0.78,0.90 | 0.87 | 0.77,0.98 | 0.84 | 0.80,0.88 | |||||

| Severe Asymmetry | --- | --- | 0.58 | 0.45,0.75 | 0.52 | 0.35,0.77 | 0.66 | 0.56,0.78 | |||||

| Cycle Number | 1 | NA | NA | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 | ||||

| 2 | 0.73 | 0.64,0.83 | 0.84 | 0.79,0.88 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.67 | 0.56,0.80 | 0.81 | 0.75,0.87 | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.68 | 0.54,0.85 | 0.79 | 0.71,0.88 | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.54 | 0.38,0.77 | 0.67 | 0.57,0.78 | |||||||||

| DAY 5 | |||||||||||||

| Grade | Good | 1.00 | Reference | 0.0003 | --- | --- | NS | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 | 1.00 | Reference | 0.01 |

| Fair | 0.80 | 0.68,0.95 | --- | --- | 0.78 | 0.69,0.87 | 0.98 | 0.92,1.05 | |||||

| Poor | 0.37 | 0.22,0.64 | --- | --- | 0.39 | 0.27,0.56 | 0.77 | 0.64,0.92 | |||||

| Stage | Early blastocyst | 0.56 | 0.48, 0.65 | <0.0001 | 0.61 | 0.57, 0.65 | <0.0001 | 0.58 | 0.52, 0.64 | <0.0001 | 0.63 | 0.60, 0.66 | <0.0001 |

| Expanded blastocyst | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | 1.00 | Reference | |||||

| Hatched blastocyst | 1.03 | 0.92, 1.15 | 1.04 | 0.98, 1.11 | 1.02 | 0.94, 1.11 | 1.05 | 1.01, 1.10 | |||||

| Inner Cell Mass | Good | --- | --- | NS | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 | --- | --- | NS | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 |

| Fair | --- | --- | 0.87 | 0.81,0.94 | --- | --- | 0.89 | 0.84,0.94 | |||||

| Poor | --- | --- | 0.73 | 0.61,0.89 | --- | --- | 0.77 | 0.65,0.91 | |||||

| Trophectoderm | Good | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 |

| Fair | 0.72 | 0.64,0.82 | 0.84 | 0.78,0.89 | 0.76 | 0.70,0.83 | 0.83 | 0.79,0.87 | |||||

| Poor | 0.57 | 0.43,0.75 | 0.72 | 0.64,0.81 | 0.56 | 0.46,0.68 | 0.72 | 0.66,0.78 | |||||

| Cycle Number | 1 | NA | NA | 1.00 | Reference | 0.0007 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 | ||||

| 2 | 0.84 | 0.76, 0.94 | 0.85 | 0.81, 0.89 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.81 | 0.70, 0.94 | 0.82 | 0.77, 0.88 | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.90 | 0.74, 1.10 | 0.78 | 0.71, 0.85 | |||||||||

| 5 | 0.78 | 0.59, 1.02 | 0.79 | 0.69, 0.90 | |||||||||

--- = factors not significant (NS) in the final model; NA is not applicable

Table 3.

Models of Live Birth by Day of Transfer, Number of Embryos Transferred, And Number of Oocytes Retrieved and Embryos Cryopreserved*

| Cycle 1 | Over All Five Cycles | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One Embryo | Two Embryos | One Embryo | Two Embryos | ||||||||||

| DAY 3 | AOR | 95% CI | P Value | AOR | 95% CI | P Value | AOR | 95% CI | P Value | AOR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Number of oocytes retrieved |

≥16 | 1.00 | Reference | 0.0025 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 |

| 11–15 | 1.27 | 0.95,1.70 | 1.08 | 0.98,1.18 | 1.06 | 0.87,1.30 | 1.02 | 0.96,1.09 | |||||

| 6–10 | 1.22 | 0.91,1.63 | 0.96 | 0.88,1.05 | 0.88 | 0.73,1.07 | 0.93 | 0.88,0.99 | |||||

| 1–5 | 0.88 | 0.65,1.18 | 0.66 | 0.59,0.73 | 0.64 | 0.53,0.78 | 0.61 | 0.57,0.66 | |||||

| Number of embryos cryopreserved |

≥11 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 |

| 6–10 | 0.91 | 0.50,1.66 | 1.12 | 0.85,1.48 | 0.92 | 0.59,1.43 | 0.98 | 0.80,1.20 | |||||

| 2–5 | 0.85 | 0.48,1.52 | 1.24 | 0.96,1.60 | 0.82 | 0.54,1.26 | 1.12 | 0.93,1.36 | |||||

| 1 | 0.94 | 0.50,1.76 | 1.23 | 0.94,1.62 | 0.91 | 0.58,1.44 | 1.14 | 0.93,1.38 | |||||

| 0 | 0.40 | 0.22,0.72 | 0.86 | 0.67,1.11 | 0.43 | 0.28,0.66 | 0.72 | 0.60,0.87 | |||||

| DAY 5 | |||||||||||||

| Number of oocytes retrieved |

≥16 | 1.00 | Reference | 0.0035 | 1.00 | Reference | 0.022 | 1.00 | Reference | 0.0024 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 |

| 11–15 | 1.13 | 1.01,1.27 | 1.06 | 1.00,1.12 | 1.08 | 0.99,1.17 | 1.08 | 1.04,1.13 | |||||

| 6–10 | 1.02 | 0.89,1.18 | 1.07 | 1.00,1.14 | 0.96 | 0.87,1.07 | 1.05 | 1.00,1.10 | |||||

| 1–5 | 0.73 | 0.57,0.94 | 0.88 | 0.75,1.04 | 0.79 | 0.67,0.93 | 0.86 | 0.77,0.97 | |||||

| Number of embryos cryopreserved |

≥11 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 | 1.00 | Reference | <0.0001 |

| 6–10 | 1.04 | 0.84,1.28 | 0.92 | 0.80,1.07 | 1.09 | 0.92,1.28 | 0.98 | 0.88,1.10 | |||||

| 2–5 | 0.97 | 0.79,1.19 | 0.85 | 0.74,0.97 | 1.03 | 0.88,1.21 | 0.90 | 0.81,1.00 | |||||

| 1 | 0.79 | 0.61,1.02 | 0.83 | 0.71,0.97 | 0.89 | 0.73,1.08 | 0.85 | 0.76,0.96 | |||||

| 0 | 0.72 | 0.57,0.91 | 0.64 | 0.55,0.74 | 0.70 | 0.59,0.84 | 0.70 | 0.63,0.78 | |||||

Models adjusted for grade, stage, fragmentation, symmetry, and cycle (day 3), and grade, stage, inner cell mass, and trophectoderm and cycle (day 5)

Figure 1.

The effects of grade and stage on live birth rate as a function of age, number of embryos transferred and day of transfer. (a) transfer day 5: grade; (b): day 3: grade; (c) day 5: stage; (d) day 3: stage. 1 and 2 are the number of embryos transferred.

Discussion

These results demonstrate the validity of the SART CORS standardized morphology parameters for predicting live birth. More advanced development (more cells at day 3 or later stage at day 5) was associated with a greater chance of live birth (1) and declining grade with a lesser chance for the day 3 and day 5 models. Stage-specific parameters which were significant included fragmentation and symmetry for day 3, and inner cell mass, and trophectoderm for day 5. The number of oocytes retrieved and number of embryos cryopreserved, which are surrogates for embryo quality, were each significant in the day 3 and day 5 models.

Morphology of transferred embryos has been a consistently reliable predictor of live birth following ART (1–3) although whether this also correlates with progressive development of healthy embryos is less clear. Development of methods to improve embryo selection such as Preimplantation Genetic Screening (13, 14) and evaluation of the metabolic products of embryo culture (15) reveals that good morphologic progression does not always predict embryo health or subsequent live birth. Another recent methodology builds on our understanding of morphological kinetics during early development using time-lapse photography to understand the developmental sequence associated with successful implantation and development (6, 16). Despite new advances, the long successful history of using standard light microscopic assessments of embryos led SART to add the embryo morphology fields to the national database. Although more sophisticated methods have shown promise as a means for determining which embryo to transfer, they have not replaced standard morphology assessments with light microscopy for choosing the transferred embryo. Because of this, and the fact that embryo morphology is currently an available parameter collected from all laboratories that report to SART CORS, we determined that it was important to evaluate the contribution of this parameter to the live birth rate for use in future models of ART success.

A variety of models have been proposed for assessing the morphology of embryos (4, 5). Some methods concentrate on embryo quality on the day of transfer while others incorporate information on earlier developmental stages as well (17). Some have developed complex systems. Holte (18), for example, developed an integrated morphology score consisting of 5 parameters including blastomere number, fragmentation, blastomere size variation (i.e. symmetry), synchrony of division (i.e. even versus odd number of cells), and mononuclearity. The fields included in the SART database, though less complex than some other systems, result in collection of parameters consistent with most published systems and include the stage, overall grade, and a limited number of stage-specific parameters.

This study, confirms the validity of the parameters that SART is collecting and confirms prior results using SART data. Particularly important was overall embryo grade. For day 3 single embryo transfers the grades of good and fair gave comparable results while poor quality embryos did less well. This is consistent with the work of Vernon, et al (9). Our study adds information on day 5 embryos transferred singly, and shows that success with embryos graded as good is superior to those graded fair or poor. Also important is embryo stage. As expected, slower growing embryos are significantly less likely to implant than those at an appropriate stage for the culture day (7–8 cells for day 3 and expanded blastocyst on day 5). The day 3 results are consistent with those previously reported (10).

Our study also confirms the significant influence of symmetry and fragmentation of day 3 embryos on live birth results. We found that fragmentation of more than 10% of the embryo was particularly associated with reduced live birth rates. This is consistent with Racowsky et al (10) using SART data, and confirms the results of prior studies based on other data (19, 20). Symmetry was also a significant predictor in all four models in this study which is also consistent with prior work (21, 22).

There has been considerable debate about the relative importance of the inner cell mass and the trophectoderm as predictors of live birth in day 5 transfers. Several recent studies suggest that trophectoderm is the more important of the two (23–26). By contrast, a study by Van den Abbdeel et al, (27), found that blastocyst expansion, and both trophectoderm and inner cell mass are important for predicting pregnancy but that poor quality inner cell mass also predicts an increase in miscarriage rate. Our study similarly demonstrates that trophectoderm is significantly associated with live birth outcome in both a one-embryo and two-embryo model. However, inner cell mass was significant in a two-embryo model. The significance of this finding is unknown and will require further investigation.

Limitations

This study has several imitations. Morphology is provided only for transferred embryos and not all embryos in a cohort; it may be that an overall assessment of all the embryos may also contribute information. When two embryos were transferred, we chose to use the morphologic assessment of the embryo with the more advanced stage and we defined a live birth as at least a singleton live birth; it may be that the quality of the second embryo which may or may not result in the presence of a second fetus may have an effect on the live birth rate. It is likely that the treating physician may change the treatment paradigm based on results of prior cycles; therefore, the results for cycles 2–5 may be biased by these changes. In addition, cycles 2–5 are sequentially numbered and do not represent the number of times transfers occurred on the same day or with the same number of embryos. Because the number of cycles for transfer days 2, 4 and 6 were small we did not include these in this paper. We propose to repeat the analysis using these additional days when sufficient sample size is available.

Conclusions

These findings confirm the significant association between embryo quality parameters reported to SART CORS and live birth following ART.

Acknowledgement

SART wishes to thank all of its members for providing clinical information to the SART CORS database for use by patients and researchers. Without the efforts of the SART members, this research would not have been possible.

Financial support: SART

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented at the 69th annual meeting, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts, October 12–17, 2013.

References

- 1.Racowsky C, Ohno-Machado L, Kim J, Biggers JD. Is there an advantage in scoring early embryos on more than one day? Hum Reprod. 2009;24:2104–2113. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tesarik J, Junca AM, Hazout A, Aubriot FX, Nathan C, Cohen-Bacrie P, et al. Embryos with high implantation potential after intracytoplasmic sperm injection can be recognized by a simple, noninvasive examination of pronuclear morphology. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:1396–1399. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.6.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Royen E, Mangelschots K, De Neubourg D, Laureys I, Ryckaert G, Gerris J. Calculating the implantation potential of day 3 embryos in women younger than 38 years of age: a new model. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:326–332. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.2.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boiso I, Veiga A, Edwards RG. Fundamentals of human embryonic growth in vitro and the selection of high-quality embryos for transfer. Reprod Biomed Online. 2002;5:328–350. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61841-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardner DK, Sakkas D. Assessment of embryo viability: the ability to select a single embryo for transfer--a review. Placenta. 2003;24(Suppl B):S5–S12. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4004(03)00136-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirkegaard K, Agerholm IE, Ingerslev HJ. Time-lapse monitoring as a tool for clinical embryo assessment. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1277–1285. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Racowsky C, Vernon M, Mayer J, Ball GD, Behr B, Pomeroy KO, et al. Standardization of grading embryo morphology. Fertility & Sterility. 2010;94:1152–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Racowsky C, Vernon M, Mayer J, Ball GD, Behr B, Pomeroy KO, et al. Standardization of grading embryo morphology. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010;27:437–439. doi: 10.1007/s10815-010-9443-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vernon M, Stern JE, Ball GD, Wininger D, Mayer J, Racowsky C. Utility of the national embryo morphology data collection by SART: Correlation between day 3 morphology grade and live birth outcome. Fertility & Sterility. 2011;95:2761, 2761–2763. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Racowsky C, Stern JE, Gibbons W, Behr B, Pomeroy KO, Biggers JD. National collection of embryo morphology data into SART CORS: Associations among day 3 cell number, fragmentation and blastomere asymmetry and live birth rate. Fertility & Sterility. 2011;95:1985, 1985–1989. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Center for Disease Control and Prevention, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, and Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. 2010 Assisted Reproductive Technology Success Rates: National Summary and Fertility Clinic Reports. Washington, DC: US Dept. of Health and Human Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Center for Disease Control and Prevention, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, and Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. 2011 Assisted Reproductive Technology Success Rates: National Summary and Fertility Clinic Reports. Washington, DC: US Dept. of Health and Human Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munne S, Fischer J, Warner A, Chen S, Zouves C, Cohen J, et al. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis significantly reduces pregnancy loss in infertile couples: a multicenter study. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:326–332. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forman EJ, Hong KH, Treff NR, Scott RT. Comprehensive chromosome screening and embryo selection: moving toward single euploid blastocyst transfer. Semin Reprod Med. 2012;30:236–242. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1311526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bromer JG, Seli E. Assessment of embryo viability in assisted reproductive technology: shortcomings of current approaches and the emerging role of metabolomics. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;20:234–241. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3282fe723d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemmen JG, Agerholm I, Ziebe S. Kinetic markers of human embryo quality using time-lapse recordings of IVF/ICSI-fertilized oocytes. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008;17:385–391. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qian Y, Ye Y, Xu C, Jin F, Huang H. Accuracy of a combined score of zygote and embryo morphology for selecting the best embryos for IVF. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2008;9:649–655. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B0820003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holte J, Berglund L, Milton K, Garello C, Gennarelli G, Revelli A, et al. Construction of an evidencebased integrated morphology cleavage embryo score for implantation potential of embryos scored and transferred on day 2 after oocyte retrieval. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:548–557. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paternot G, Debrock S, D'Hooghe T, Spiessens C. Computer-assisted embryo selection: a benefit in the evaluation of embryo quality? . Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;23:347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keltz MD, Skorupski JC, Bradley K, Stein D. Predictors of embryo fragmentation and outcome after fragment removal in in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:321–324. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sole M, Santalo J, Rodriguez I, Boada M, Coroleu B, Barri PN, et al. Correlation between embryological factors and pregnancy rate: development of an embryo score in a cryopreservation programme. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2011;28:129–136. doi: 10.1007/s10815-010-9498-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rienzi L, Ubaldi F, Iacobelli M, Romano S, Minasi MG, Ferrero S, et al. Significance of morphological attributes of the early embryo. Reprod Biomed Online. 2005;10:669–681. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61676-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahlstrom A, Westin C, Reismer E, Wikland M, Hardarson T. Trophectoderm morphology: an important parameter for predicting live birth after single blastocyst transfer. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:3289–3296. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hill MJ, Richter KS, Heitmann RJ, Lewis TD, DeCherney AH, Graham JR, et al. Number of supernumerary vitrified blastocysts is positively correlated with implantation and live birth in singleblastocyst embryo transfers. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:1631–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.01.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahlstrom A, Westin C, Wikland M, Hardarson T. Prediction of live birth in frozen-thawed single blastocyst transfer cycles by pre-freeze and post-thaw morphology. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:1199–1209. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marshall TS, Onwubalili N, Brown K, Jindal SK, McGovern PG. Blastocyst expansion score and trophectoderm morphology strongly predict successful clinical pregnancy and live birth following elective single blastocyst transfer (SET): A national study. J Assist Reprod Genetics. 2013;30:1577–1581. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0100-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van den Abbeel E, Balaban B, Ziebe S, Lundin K, Cuesta MJ, Klein BM, et al. Association between blastocyst morphology and outcome of single-blastocyst transfer. Reprod Biomed Online. 2013;27:353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]