Abstract

In India, “non-notified” slums are not officially recognized by city governments; they suffer from insecure tenure and poorer access to basic services than “notified” (government-recognized) slums. We conducted a study in a non-notified slum of about 12,000 people in Mumbai to determine the prevalence of individuals at high risk for having a common mental disorder (i.e., depression and anxiety), to ascertain the impact of mental health on the burden of functional impairment, and to assess the influence of the slum environment on mental health. We gathered qualitative data (six focus group discussions and 40 individual interviews in July-November 2011), with purposively sampled participants, and quantitative data (521 structured surveys in February 2012), with respondents selected using community-level random sampling. For the surveys, we administered the General Health Questionnaire-12 (GHQ) to screen for common mental disorders (CMDs), the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHO DAS) to screen for functional impairment, and a slum adversity questionnaire, which we used to create a composite Slum Adversity Index (SAI) score. Twenty-three percent of individuals have a GHQ score ≥5, suggesting they are at high risk for having a CMD. Psychological distress is a major contributor to the slum’s overall burden of functional impairment. In a multivariable logistic regression model, household income, poverty-related factors, and the SAI score all have strong independent associations with CMD risk. The qualitative findings suggest that non-notified status plays a central role in creating psychological distress—by creating and exacerbating deprivations that serve as sources of stress, by placing slum residents in an inherently antagonistic relationship with the government through the criminalization of basic needs, and by shaping a community identity built on a feeling of social exclusion from the rest of the city.

Keywords: mental health, common mental disorders, depression, poverty, slums, informal settlements, urban, India

Introduction

In India, an estimated 44 to 105 million people live in urban slums (Millennium Development Goals database, 2009; Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, 2013). While both the United Nations (UN) and the Government of India have official slum definitions (Appendix A), these definitions conceal substantial differences in deprivation both between settlements (inter-slum variation) and within settlements (intra-slum variation). One of the major causes of inter-slum variation is a legal divide between notified (government-recognized) slums and non-notified (unrecognized) slums. Thirty-seven percent of slum households in India and 39% of slum households in Maharashtra, the state in which Mumbai is located, are non-notified (Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, 2013). Across India, non-notified slums suffer from substantially poorer access than notified slums to latrines, piped water, electricity, and housing materials; they also receive much less assistance from government slum improvement schemes (Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, 2013).

In this paper, we investigate mental health in Kaula Bandar (KB), a non-notified slum with a population of about 12,000 people situated on a wharf on Mumbai’s eastern waterfront. Originally settled decades ago by migrants from Tamil Nadu, KB has recently witnessed a wave of migrants from the poorer north Indian states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. KB is located on land held by the Mumbai Port Trust (MbPT), a central (federal) government agency that has no official slum policy. As a result, KB residents live in a state of legal exclusion. Although the slum is located only six kilometers from the country’s stock exchange, its occupation of a legal “no man’s land” offers no clear possibility for securing land and housing tenure or formal access to municipal water and sanitation infrastructure (Subbaraman et al., 2013). We have previously shown that the disparity in access to resources between KB and other Mumbai slums results in dramatically poorer health and educational outcomes in KB (Subbaraman et al., 2012). This study of mental health in KB is therefore partly an investigation of the psychological consequences of legal exclusion; it is also undertaken in the context of a paucity of studies globally on the impact of the slum environment on mental health, despite the fact that an estimated one billion people worldwide live in slums (UN-HABITAT, 2006).

We first estimate the burden of common mental disorders (i.e., major depression and generalized anxiety) in KB using quantitative data and also examine the adverse impact of psychological distress by assessing its relative contribution to the overall burden of functional impairment in the slum. We then investigate the impact of the slum environment on the risk of having a common mental disorder (CMD) in multiple multivariable analyses, using a “Slum Adversity Index” to capture meaningful intra-slum variation in cumulative exposure to slum-related stressors.

We subsequently use findings from in-depth qualitative interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) with KB residents to understand how each slum adversity causes psychological distress. The qualitative findings suggest that KB’s condition of legal exclusion plays a central role in creating psychological distress—by creating or exacerbating deprivations that serve as sources of stress, by placing residents in an inherently antagonistic relationship with the government through the criminalization of activities required for basic survival, and by shaping a community identity built on a feeling of social exclusion from the rest of the city.

Methods

The qualitative interview phase

We collected the qualitative data with three purposes: to provide an empirical basis for creating a “slum adversity” survey questionnaire for the quantitative phase, to collect narrative data that illuminate how specific adversities lead to psychological distress, and to situate these adversities in KB’s larger context of non-notified status. The interviews were collected by four PUKAR researchers who had three years of prior field research experience in KB. The qualitative questionnaire was translated into Hindi, Marathi, and Tamil and began with an open-ended free-listing exercise to allow respondents to identify important life adversities without influence from the interviewer. Since some adversities may not be freely volunteered, interviewees were then read a list of possible slum adversities and asked whether and how these had negatively impacted them. After obtaining informed consent, interviews were audio-recorded in Hindi, Tamil, or Marathi. Each interview or FGD took 40–60 minutes and was transcribed and translated into English for analysis.

In July 2011, six focus group discussions (FGDs) were performed in Hindi (three male-only and three female-only groups), with approximately six to nine individuals in each group. All FGD participants, including those of Tamil origin, were fluent in Hindi. The FGDs included 21 men with ages ranging from 19–70 (median 30) years and 25 women with ages ranging from 22–65 (median 35) years. In November 2011, individual interviews were collected with one transgender person, 19 men, and 20 women. We purposively sampled individuals using a framework that ensured representation of major ethnic and religious groups in KB. The ethnic composition of the 40 individual interviewees included 17 (43%) North Indians, 17 (43%) South Indians, and 6 (15%) Maharashtrians. With regard to religious composition, the interviewees included 20 (50%) Muslims, 15 (38%) Hindus, 3 (8%) Christians, and 2 (5%) Buddhists. Fourteen (35%) report being illiterate or having never enrolled in school. The men had ages ranging from 25–72 (median 38) years; the women had ages ranging from 21–55 (median 33.5) years.

The quantitative survey phase

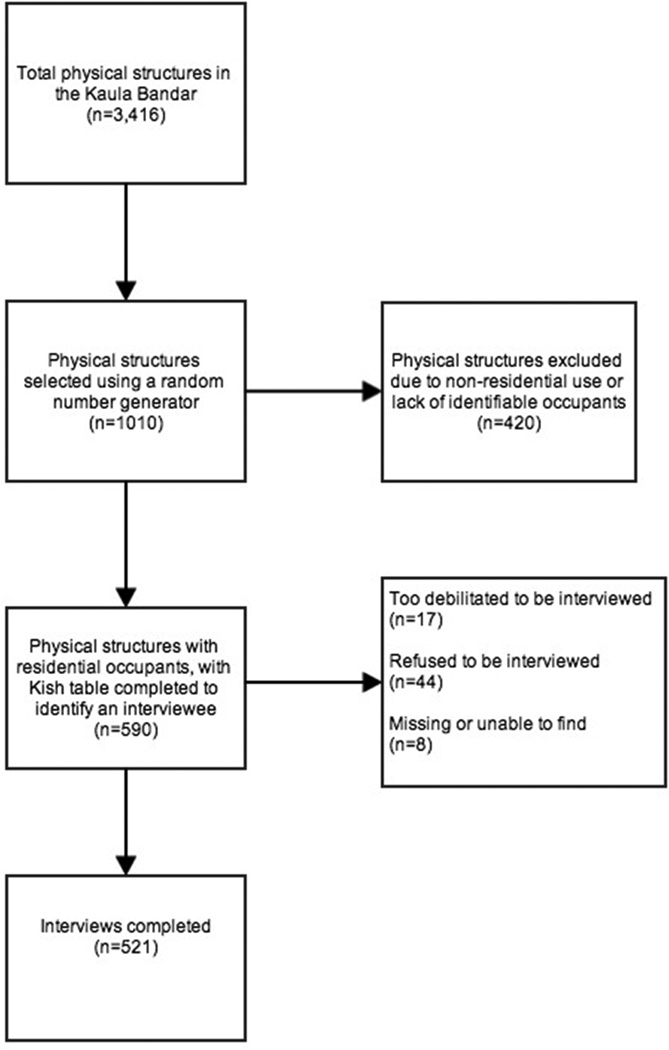

In January 2012, we performed a census in which we enumerated a total of 3,416 potential living spaces in KB (Thomson et al., 2014). We then used a random number generator to select 1010 potential living structures from this comprehensive database, of which 420 structures were found to be used for exclusively non-residential purposes or were locked with no identifiable occupants (Figure 1). In KB, physical structures serve different purposes at different times, including housing, a business workshop, religious space, or storage. Structures were deemed to be unoccupied only after a minimum of three visits on separate days (including one nighttime visit), as well as confirmation from neighbors. For the remaining 590 occupied structures, we interviewed only one adult in each household so as not to introduce intra-household clustering effects and to enhance the variability of the sample. A Kish table was used to ensure random selection of an adult over 18 years of age to whom the survey was administered after obtaining informed consent (Kish, 1949). So as not to violate the random selection process, substitution of another adult in the household was not allowed.

Figure 1.

Sample selection flow chart for the quantitative survey

The surveys were administered in February 2012 by PUKAR’s “barefoot researchers” (an allusion to “barefoot doctors”), who are local youth, many of whom live in KB and all of whom have at least a high school education. The barefoot researchers (BRs) are the core of PUKAR’s community-based participatory research model, which views the research process as an opportunity for empowerment and self-transformation of the BRs themselves. Given KB’s non-notified status, some residents are suspicious of researchers from outside the community. The knowledge that most BRs live in KB put many interviewees at ease; the understanding that BRs face the same slum adversities on a daily basis likely reduced social desirability bias for questions about sensitive topics (e.g., open defecation). Prior to the survey, a clinical psychologist and two physicians led six training sessions to educate BRs about CMDs, non-judgmental interviewing techniques, research ethics, and administration of the quantitative survey. Given low literacy levels in KB, BRs verbally administered all of the instruments to respondents. Initial surveys collected by each BR were observed. All questionnaires were monitored to minimize missing responses.

BRs had to go to some households several times to find interviewees, as some men work all days of the week and only return home at night. BRs living in KB were able to go to these households late at night or early in the morning to interview 27 respondents who would otherwise have been unavailable. Seventeen individuals were unable to answer the survey due to severe illness or disability; 44 individuals refused to enroll in the study; and eight individuals were not found despite the study team’s best efforts (including a minimum of three daytime and two nighttime visits). Excluding those who were too debilitated to answer the survey, the non-response rate was 9%.

Measurement of predictors and outcomes for the quantitative survey

CMDs

We use the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) to screen for CMDs, as a literature review suggests that it is the most rigorously validated screening tool in India (Goldberg et al., 1997; V. Patel et al., 2008). The instrument has excellent reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha and test-retest reliability scores consistently >0.8. Based on these validation studies, we use a GHQ cut-off score of ≥5 for performing the multivariable logistic regression analyses to identify predictors of high CMD risk. In prior validation studies in clinic settings in India, this cut-off had a sensitivity of 73–87%, a specificity of 89–90%, and an accuracy of 87% for identifying CMDs (Goldberg et al., 1997; V. Patel et al., 2008).

The GHQ is not designed to screen for serious mental disorders (e.g., psychotic disorders), and the 12-item version does not assess for somatoform symptoms of CMDs, which may be common in India. Also, since the GHQ is only a screening instrument, it identifies individuals who are at high risk for having a CMD. It does not confirm a diagnosis of depression or generalized anxiety, which would require a formal evaluation by a health professional. In addition, the GHQ has primarily been validated as a screening tool in primary care settings; as such, its operating characteristics in community settings are less clear.

Despite these limitations, the GHQ and similar screening instruments are being used widely in population-based studies to provide rough estimates of disease burden (Fernandes, Hayes, & Patel, 2013; Poongothai, Pradeepa, Ganesan, & Mohan, 2009). We use the GHQ in this study because of its well-described operating characteristics in the Indian context, ease of administration by lay researchers to respondents with low literacy levels, and comparability with other studies, even as we acknowledge its limitations as an instrument for assessing the prevalence of CMDs in community settings.

Functional status

The World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHO DAS) is a 12-item questionnaire that serves as a cross-cultural measure of functional status in six domains: cognition, mobility, self-care, social interaction, life activities, and participation in the community. This instrument is broadly useful for measuring functional impairment from acute and chronic illnesses, physical disabilities, cognitive disorders, and mental illness (Sosa et al., 2012). It has been validated in 19 countries, including three sites in India. Reliability scores are high; both Cronbach’s alpha and test-retest reliability coefficients are 0.98 (Ustun, Kostanjsek, Chatterji, & Rehm, 2010). For our analyses, we converted raw WHO DAS scores into item response theory (IRT)-based scores ranging from 0–100 using statistical coding from the WHO. IRT-based scoring differentially weights answers to WHO DAS items based on level of difficulty (Ustun et al., 2010). We define “some” functional impairment as any WHO DAS score greater than 0 and “severe” functional impairment as any score greater than 17, which corresponds to functional impairment greater than the 75th percentile for the WHO DAS’s international population norms. While the WHO DAS provides a global assessment of functional status, we also collected data on specific physical disabilities, including deficits of vision, hearing, speech, paralysis, and loss of limb. For comparability, these questions were worded using language similar to that used in the Census of India and India’s National Sample Survey.

Slum adversities

The qualitative data provided the empirical basis for developing the slum adversity quantitative survey, based on an exploratory sequential mixed-methods design (Creswell, Klassen, Plano Clark, & Smith, 2012). After the qualitative interviews were completed, researchers collectively reviewed and discussed the findings in order to identify key adversities faced by KB residents. These adversities were placed into categories based on their relation to characteristics of the UN Operational Definition of a slum (Appendix A). Questions were then created that assess the nature and severity of exposure to each adversity.

Analysis of quantitative data

We used STATA version 13 for all analyses and R version 3.0.3 to produce graphs. To identify predictors of functional status, we built a multivariable linear regression model with the WHO DAS score as the outcome. Sets of independent variables were serially added to the model in the following order: demographics, income, specific physical impairments, and GHQ score. We report the amount of variability in the WHO DAS score accounted for by each set of variables using the serial changes in the adjusted R2 for the model. In addition, separate bivariate analyses were performed to investigate the association between GHQ score and the WHO DAS score and between physical impairments and the WHO DAS score.

To identify predictors associated with the outcome of high CMD risk (GHQ score ≥5), we built two multivariable logistic regression models. The first model has the goal of identifying specific slum adversities that might be associated with high CMD risk, after controlling for all other predictors; as such, this first model includes each slum adversity as a separate predictor (see Appendix B for the individual slum adversities included in this analysis). The second multivariable logistic regression model has the goal of identifying the association of the overall slum environment, as represented by a composite Slum Adversity Index (SAI) score, with the outcome of high CMD risk. Finally, to identify predictors associated with GHQ score as a continuous outcome, we built a multivariable linear regression model. This third model also included the composite SAI score as a predictor representing exposure to the overall slum environment.

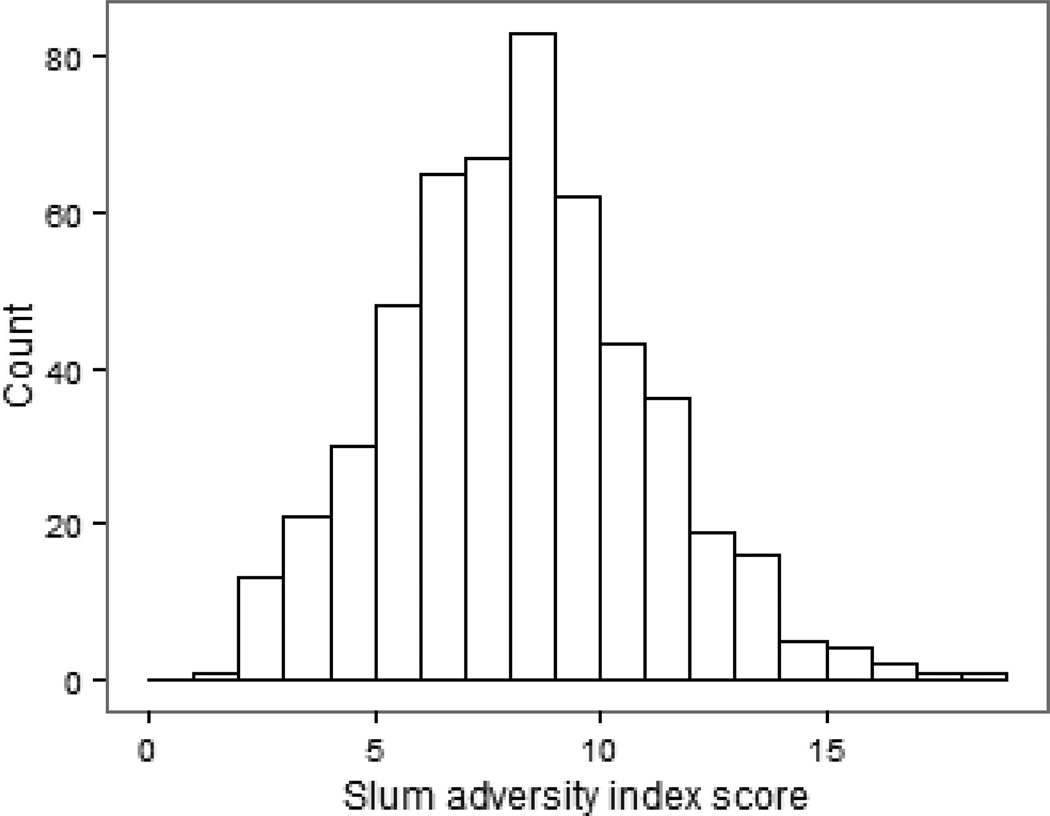

The SAI is comprised of a linear combination of dichotomous variables, each representing a respondent’s exposure to a particular slum adversity, coded as 1 if the respondent was exposed and 0 if not. These adversities are summed for each respondent to produce his or her SAI score (ranging from 0 to 18), which did not require normalization given the index’s natural relatively normal distribution in the population (Figure 2) and the relative difficulty of interpretation after normalization. The SAI’s association can be easily interpreted as the “effect” of each additional slum deprivation on the outcome of high CMD risk.

Figure 2.

Histogram depicting the distribution of Slum Adversity Index scores

Analysis of the qualitative data

We performed an in-depth analysis of the qualitative data using the immersion/crystallization method, in which excerpts related to key themes of interest (e.g., specific slum adversities) were systematically extracted through a full reading of all FGD and interview transcripts. We then analyzed the narrative data for each adversity to better understand precisely how the adversity causes distress (i.e., “mechanisms” of distress), the coping strategies used to minimize the adverse impacts of the adversity, and the connection between the adversity and KB’s larger context of legal exclusion. Representative quotations were selected that illustrate key findings for particular slum adversities.

Ethical approval

The PUKAR Institutional Ethics Committee (FWA00016911) approved the study protocol in February 2011. Participants with a GHQ score ≥5 were referred to the psychiatry clinic at King Edward Memorial Hospital, one of Mumbai’s few public sector mental health centers.

Quantitative results

Prevalence of individuals with high CMD risk and prevalence of slum adversities

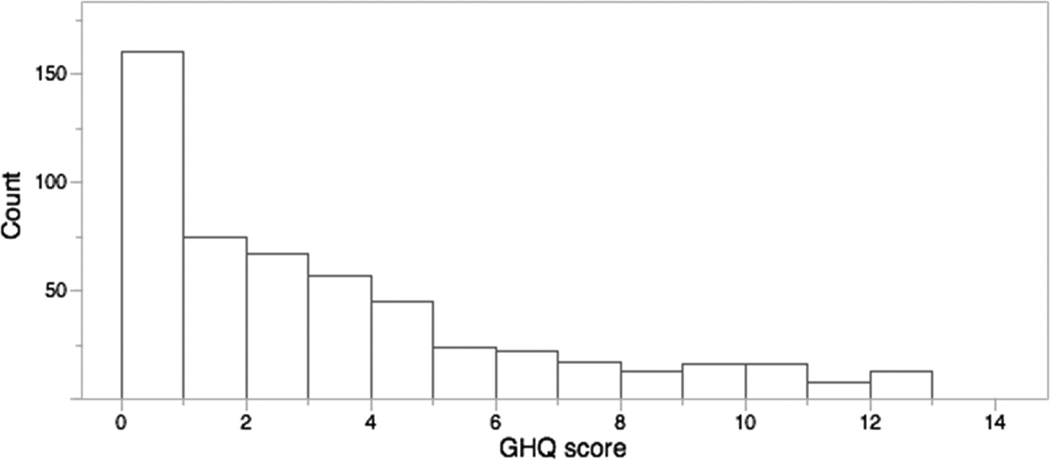

Using a GHQ cut-off of ≥5, 23.2% (95% CI: 19.8–27.0%) of individuals are high-risk for having a CMD. The distribution of GHQ scores in the population ranges from 160 individuals (30.7%) having the lowest score of 0 to 12 individuals (2.3%) having the highest score of 12 (Figure 3). Appendix B presents KB’s demographic characteristics (column 2), the prevalence of each slum adversity (column 2), and the proportion of various demographic groups who are at high risk for having a CMD (column 3). Commonly experienced slum adversities include not having an electricity meter (52.8%) and being very adversely affected by rats (51.4%), while relatively uncommonly experienced slum adversities include loss of one’s home in a slum fire (7.9%) and having experienced home demolition by the government (4.4%). Notably, while the quantitative findings suggest that home demolition is relatively infrequent in KB, the qualitative findings suggest that most residents are concerned about the eventual possibility of home demolition, as threats of displacement are pervasive.

Figures 3.

Histogram depicting the distribution of GHQ scores

Prevalence and predictors of functional impairment

Using WHO DAS IRT-based scoring, 73% of individuals meet criteria for having some functional impairment; 25% have severe functional impairment. By comparison, in the 19-country WHO DAS global validation study, 50% of individuals had some functional impairment and 10% had severe functional impairment (Ustun et al., 2010). Of those in KB with a GHQ score ≥5, the mean WHO DAS score is 22.9 (standard deviation 22.8); 91% have some functional impairment; and 41% have severe functional impairment. Of those with a GHQ score <5, the mean WHO DAS score is 8.2 (standard deviation 9.4); 67% have some functional impairment; and 12% have severe functional impairment. Table 1 reports the prevalence estimates of specific physical disabilities; 17% of people in KB have at least one self-reported physical disability that is permanent and severe enough to restrict daily activities.

Table 1.

Prevalence of self-reported physical disabilities and a comparison with national data from urban areas in India

| Physical disability | Prevalence in Kaula Bandar |

Prevalence in urban areas of India from the 2001 Census (Walia, 2010) |

Prevalence in urban areas of India from the 2002 National Sample Survey (NSS) (Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, 2003) |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | % | % | |

| Visual disability | 81 (15.5) | 0.97 | 0.2a |

| Hearing disability | 24 (4.6) | 0.08 | 0.2 |

| Speech disability | 4 (0.8) | 0.14 | 0.2 |

| Locomotor disability | 13 (2.5)b | 0.50 | 0.9 |

| Any physical disability | 87 (16.7) | 1.93c | 1.49c |

Includes categories of “low vision” and “blindness” from the NSS

Includes categories of “permanent paralysis of any part of the body” and “loss of leg, arm, hand, foot, or thumb” from the Kaula Bandar survey

Includes “severe mental disability” in addition to physical impairments noted above

In separate bivariate analyses, GHQ score alone accounts for 22.4% of the variation in WHO DAS score; physical disabilities alone account for 19.2% of the variation in WHO DAS score. In the multivariable linear regression model with WHO DAS score as the outcome built using a step-wise approach, demographic factors (gender, age, education, religion, region of origin) alone account for 14.2% of the variation in WHO DAS score, prior to adding other variables to the model. Adding income to the model did not account for any additional proportion of the variation in WHO DAS score. Adding specific physical disabilities accounts for an additional 12.5% of the variation. The addition of GHQ score accounts for an additional 8.7% of the variation, after controlling for all other covariates. The final model accounts for 35.4% of the variation in WHO DAS score. Female gender, increasing age, visual impairment, speech impairment, paralysis or loss of limb, and increasing GHQ score are all statistically significantly associated with functional impairment as measured by the WHO DAS score (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable linear regression model for the outcome of functional impairment, assessed using the WHO DAS score (adjusted R2=0.35, N=507)

| β-coefficient (CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| DEMOGRAPHICS | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | − | − |

| Female | 3.08 (0.801, 5.360) | 0.008* |

|

Age (per each year increase in age) |

0.16 (0.055, 0.262) | 0.003* |

|

Educational

attainment (per each year increase in educational attainment) |

−0.25 (−0.538, 0.048) | 0.090 |

| Religion | ||

| Muslim | − | − |

| Hindu | −0.53 (−3.105, 2.048) | 0.687 |

| Other (Christian or Buddhist) | 1.26 (−4.230, 6.760) | 0.651 |

| Region of origin | ||

| North Indian | − | − |

| South Indian | −2.93 (−5.913, 0.061) | 0.055 |

| Maharashtrian | 1.06 (−2.239, 4.351) | 0.529 |

| Nepali | 0.78 (−4.024, 5.580) | 0.750 |

|

Household income in the last

montha (per each increase in income category) |

−3.40 (−13.097, 6.289) | 0.490 |

| PHYSICAL IMPAIRMENTS | ||

| Trouble seeing | 4.50 (1.115, 7.915) | 0.010* |

| Trouble hearing | 1.51 (−4.458, 7.472) | 0.620 |

| Difficulty with speech | 19.48 (6.170, 32.794) | 0.004* |

|

Paralysis of any part of the body or

loss of leg, arm, hand, foot,

or thumb |

21.45 (14.430, 28.474) | <0.001* |

| PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTRESS | ||

|

GHQ score (per each point increase in GHQ score) |

1.56 (1.186, 1.931) | <0.001* |

| Constant | 0.64 (−3.491, 4.778) | 0.760 |

Income ranges from Indian rupees (INR) <3000 (lowest category) to ≥12,000 (highest category); all other categories are in INR 1000 increments (e.g., INR 3000–3999)

Factors associated with high risk for having a CMD

In the first multivariable logistic regression model, in which each slum adversity is included as a separate predictor, the only slum adversities independently associated with GHQ score ≥5 are: paying a high price for water (Indian rupees ≥200 per 1000 liters), having to sleep sitting up or outside the home due to lack of home space, and lacking a Permanent Account Number (PAN) card (Appendix B). A PAN card is a government-issued identity card that facilitates opening bank accounts and enrolling in formal employment; KB residents are often unable to obtain PAN cards due to lack of a formal address as a result of the slum’s non-notified status.

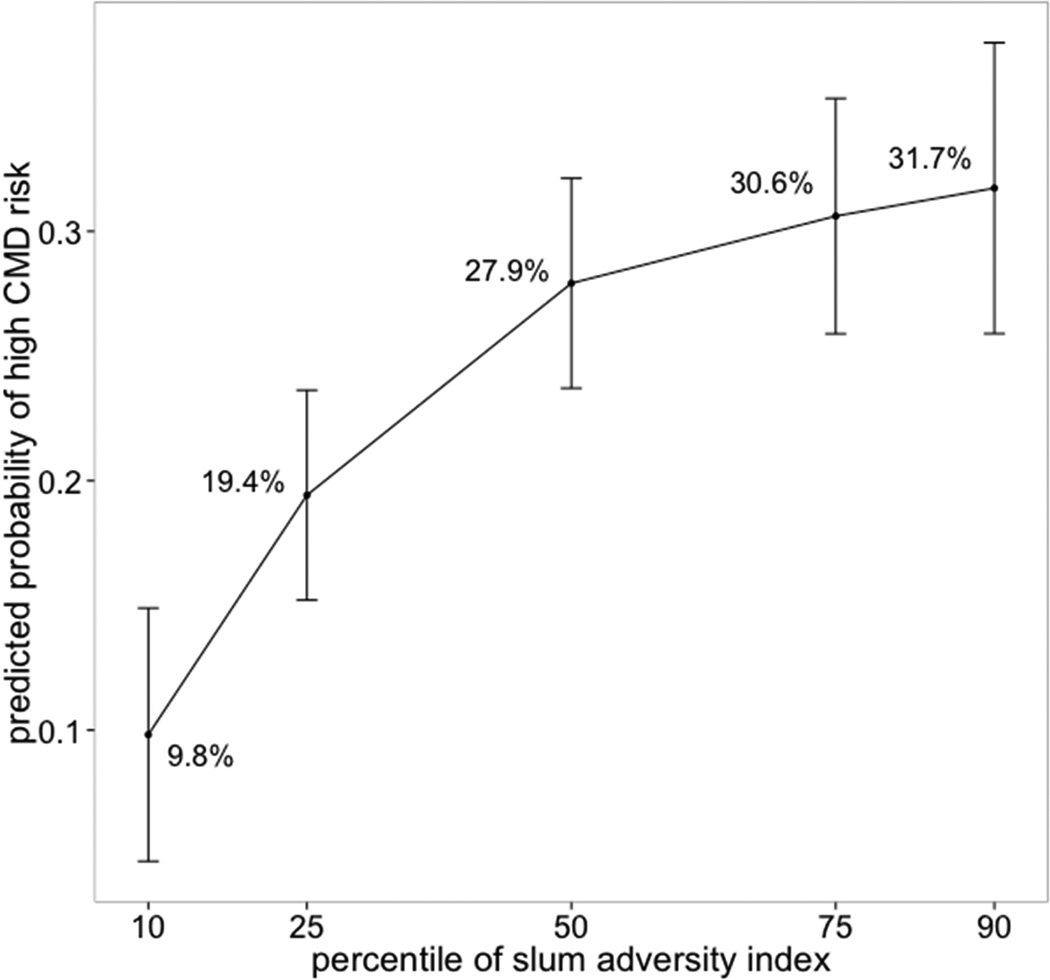

In the second multivariable logistic regression model for the outcome of GHQ score ≥5, in which all slum adversities were combined into a single Slum Adversity Index (SAI) score, female gender, age ≥45 years, being of Maharashtrian or Nepali ethnic origin, having any physical disability, having a loan, and moderate or severe food insecurity are associated with high CMD risk, while having 5–9 years of education and increasing income are protective (Table 3). After controlling for all other variables, including income, the SAI has a strong independent association with GHQ score ≥5; notably, a quadratic term was also significant in the model, suggesting that the relationship between the SAI and high CMD risk is non-linear. Based on this model, the predicted probability of having a GHQ score ≥5, after controlling for all other variables including income, are 9.8%, 19.4%, 27.9%, 30.6%, and 31.7% for individuals at the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles of the SAI respectively (Figure 4). As suggested by the significant quadratic term for the SAI, the changes in the probability of having a GHQ score ≥5 for a given change in SAI score are more substantial at lower percentiles than at higher percentiles of the SAI.

Table 3.

Multivariable logistic regression model identifying factors associated with a GHQ score ≥5, including slum adversities as a single Slum Adversity Index score

| Descriptive statistics | Regression model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion of sample (N=521) |

High risk for CMDs (GHQ score ≥5) |

Univariate Findings |

Multivariable findings (R2 = 0.32, N=485) |

p-value | |

| N(%) | N(%) |

Odds

Ratio (p-value) |

Odds

Ratio (CI) |

||

| DEMOGRAPHICS | |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 251(48.2) | 49(19.5) | − | − | − |

| Female | 270(51.8) | 72(26.7) | 1.50 (0.054) | 2.12(1.049, 4.663) | 0.037* |

| Age | |||||

| 18–24 | 128(24.6) | 19(14.8) | − | − | − |

| 25–34 | 183(35.1) | 33(18.0) | 1.26(0.459) | 1.06(0.466, 2.408) | 0.890 |

| 35–44 | 130(25.0) | 35(26.9) | 2.11(0.018) | 1.60(0.661, 3.865) | 0.661 |

| 45+ | 80(15.4) | 34(42.5) | 4.24(<0.001) | 2.80(1.064, 7.344) | 0.037* |

| Education | |||||

| No education | 213(41.9) | 70(32.9) | − | − | − |

| <5 years education | 50(9.8) | 12(24.0) | 0.64(0.226) | 0.91(0.358, 2.304) | 0.840 |

| 5–9 years education | 183(36.0) | 27(14.8) | 0.35(<0.001) | 0.45(0.226, 0.899) | 0.024* |

| 10+ years education | 62(12.2) | 9(14.5) | 0.35(0.006) | 0.70(0.259, 1.880) | 0.476 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Yes | 408(78.3) | 88(21.6) | − | − | − |

| No | 113(21.7) | 33(29.2) | 1.50(0.09) | 1.59(0.775, 3.254) | 0.207 |

| Employment | |||||

| Currently employed | 299(57.4) | 66(22.1) | − | − | − |

| Unemployed | 222(42.6) | 55(24.8) | 1.16(0.470) | 1.08(0.537, 2.184) | 0.825 |

| Religion | |||||

| Muslim | 255(48.9) | 51(20.0) | − | − | − |

| Hindu | 241(46.3) | 60(24.9) | 1.32(0.192) | 1.06(0.555, 2.030) | 0.856 |

| Christian or Buddhist | 25(4.8) | 10(40.0) | 2.67(0.025) | 2.24(0.627, 7.986) | 0.215 |

| Region of origin | |||||

| North Indian | 246(47.2) | 38(15.5) | − | − | − |

| South Indian | 164(31.5) | 46(28.0) | 2.13(0.002) | 1.09(0.501, 2.393) | 0.821 |

| Maharashtrian | 80(15.4) | 25(31.25) | 2.49(0.002) | 2.65(1.116, 6.266) | 0.027* |

| Nepali | 31(6.0) | 12(38.7) | 3.46(0.002) | 3.19(1.039, 9.792) | 0.043* |

| Migration status | |||||

| Born in KB or migrated

to KB from urban area |

223(42.8) | 53(23.8) | − | − | − |

| Migrated from a rural area | 298(57.2) | 68(22.8) | 0.95(0.800) | 1.30(0.701, 2.398) | 0.408 |

| Physical Disability | |||||

| No disability | 430(82.5) | 82(67.8) | − | − | − |

| One or more disabilitiesa | 91(17.5) | 39(32.2) | 3.18(<0.001) | 2.62(1.358, 5.060) | 0.004* |

|

INCOME AND POVERTY- RELATED VARIABLES |

|||||

|

Household income in

the last month |

|||||

| INRb <3000 | 37(7.2) | 18(48.6) | − | − | − |

| INR 3000–4999 | 148(28.8) | 43(29.0) | 0.43(0.025) | 0.40(0.159, 0.994) | 0.048* |

| INR 5000–6999 | 169(32.9) | 34(20.1) | 0.26(0.001) | 0.28(0.109, 0.700) | 0.007* |

| INR 7000–9999 | 102(19.9) | 14(13.7) | 0.17(<0.001) | 0.27(0.098, 0.772) | 0.014* |

| INR 10000+ | 57(11.1) | 10(17.5) | 0.22(0.002) | 0.31(0.099, 0.967) | 0.044* |

| Actively has a loan | |||||

| No | 213(59.1) | 40(13.0) | − | − | − |

| Yes | 213(40.9) | 81(38.0) | 4.11(<0.001) | 3.71(2.033, 6.758) | <0.001* |

| Food insecurityc | |||||

| 0 | 382(74.9) | 60(15.7) | − | − | − |

| 1–4 | 92(18.0) | 32(34.8) | 2.86(<0.001) | 1.94(1.008, 3.733) | 0.047* |

| ≥5 | 36(7.1) | 27(75.0) | 16.1(<0.001) | 10.02(3.598, 27.931) | <0.001 |

| SLUM ADVERSITIES | |||||

|

Slum adversity index

– linear term |

mean = 7.72 | mean = 8.92 | 1.22(<0.001) | 2.91(1.723, 4.928) | <0.001* |

|

Slum adversity –

quadratic term |

− | − | − | 0.95(0.923, 0.977) | <0.001* |

| Constant | − | − | − | 0.00(0.000, 0.010) | <0.001* |

Includes individuals who had any of the following: visual disability, hearing disability, speech disability, permanent and severe paralysis of any part of the body, or loss of leg, arm, hand, foot, or thumb

INR=Indian rupees

Number of times household was unable to buy enough food in the last month

Figure 4.

Predicted probabilities of having a GHQ score ≥5, at different percentiles of the Slum Adversity Index, after adjusting for income and other covariates in a multivariable logistic regression model

The third model, a multivariable linear regression analysis with GHQ score as a continuous outcome, yields similar results. The SAI has a statistically significant and non-linear association with GHQ score, after controlling for all other predictors, including income (Appendix C). Notably, in this model, income no longer has a significant association with GHQ score, possibly due to the strong association of the SAI and other poverty-related variables with the outcome or to the inclusion of income as a continuous (rather than a categorical) variable in the model.

Qualitative results

Mechanisms by which slum adversities cause psychological distress

The qualitative findings clarify how specific adversities can cause severe stress (i.e., what we are calling “mechanisms of distress”), while also highlighting unique coping strategies used by KB residents to minimize the adverse impacts of these stressors. While we are only able to touch upon a few key adversities in depth below, details of all the slum adversities that emerged from the qualitative interviews are summarized in Table 4; notably, all of the listed mechanisms of distress and coping strategies are drawn directly from specific statements found in the individual interviews. The narrative data suggest that many of these adversities arise from, or are exacerbated by, the slum’s situation of legal exclusion.

Table 4.

Features of slum adversities based on findings of the qualitative interviews

| Slum adversity | Mechanisms by which the adversity causes distressa | Coping strategiesa | Relationship of the adversity with legal exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| OVERCROWDING | |||

|

Lack of space

within the home |

Shortage of space for all family members to sleep inside | Adults sleep sitting up or contorted in

uncomfortable positions; adults sleep outside when possible; women sleep while children are at school; men take night shifts at work to open up space for others to sleep |

Aggressive policing and

home demolitions in the remaining open spaces in KB limit space for laterally expanding homes, widening lanes, and building new homes. The police request bribes from people wishing to expand their homes upward. These costs are often prohibitive and prevent home expansion. |

| Inability to find space for guests or

relatives when they visit, especially from native villages |

Guests and relatives are rarely invited to

visit; adults sleep outside when guests visit or have guests sleep in communal religious spaces (temple, madrassas) |

||

| Individuals with illness have difficulty

finding space to rest in the home |

Children are often shifted to sleep in

neighbors’ homes when an adult is sick; other adults sleep outside |

||

| Inability to eat meals collectively as a family | Family members eat food in shifts | ||

| Chronic pain from sleeping in contorted positions | |||

| Use of the same drainage space in the home for

washing dishes, bathing, and sometimes urination |

|||

| Narrow slum lanes | Difficulty navigating large (300 liter) water

drums through lanes, often precipitating conflicts with neighbors whose possessions get knocked over |

Large drums are rolled to lane entrances, and

water is transported to the home through numerous trips using smaller containers |

|

| Trauma from falls and shocks from open

electric wires while traveling in lanes at night |

Trips through lanes at night are minimized,

even to fulfill calls of nature |

||

| Difficulty using cooking stoves outdoors due

to lack of lane space |

Women travel to open grounds to cook | ||

| Difficulty queuing up in the lane during water

delivery times |

Women rotate turns being first in the queue

for water on different days of the week |

||

| Entrapment of individuals from stampedes in

lanes during emergencies, especially fires |

|||

| INSECURE RESIDENTIAL STATUS | |||

|

Difficulty

accessing official documents, especially ration cards, permanent account number (PAN) cards, and voting cards due to lack of home ownership documents or formal electricity bills |

Recurrent, often fruitless, attempts to

negotiate with government officials to get official documents |

Payment of expensive bribes to government

officials to try to access these documents, often without success |

Lack of property deeds

or official addresses for homes, both resulting from KB’s non- notified status, serve as prohibitive obstacles during the application process for most other official documents |

| Even if documents are issued, names are

often misspelled or left off the ration cards, resulting in decreased kerosene and rice quotas |

Correction of these costly bureaucratic

mistakes is often deferred, as the absence of home ownership documents makes accountability difficult without payment of further bribes |

||

| Inability to access subsidized goods,

especially kerosene, from the local ration shop |

Kerosene is purchased on the black market at

great expense |

||

| Difficulties enrolling children in school,

opening a bank account, and voting in elections |

|||

|

Eviction and

home demolition, or fear of mass displacement |

Loss of shelter | Unstable shelters are often rebuilt

immediately using plastic tarp and scraps from demolished homes |

Non-notified status

precludes security of tenure for KB residents. The lack of any official slum policy by the Mumbai Port Trust means that it is unclear whether restitution will be provided in the case of mass displacement. |

| Confiscation of possessions within homes

during evictions, as authorities often claim all items as belonging to the Mumbai Port Trust |

Residents sometimes pay officials to reclaim

confiscated possessions |

||

| Fear of future eviction en mass expressed by

nearly all residents; concerns heightened by uncertainty around government policies with regard to restitution |

Residents protect official documents in the

hope that these may allow claims for restitution the future; however, the value of these documents for claiming restitution is unclear, and protecting documents is difficult due to home flooding and fires |

||

| Home expansions draw the attention of local

authorities, who threaten demolition of these home expansions |

During home expansion, bribes must be paid to

officials to stave off demolition |

||

| KB residents develop a feeling of being

socially ostracized as they witness residents of notified slums getting resettled in formal buildings in cases of displacement |

|||

| POOR STRUCTURAL QUALITY OF HOUSING / POOR HOUSING LOCATION | |||

|

Poor quality

housing materials (wood, mud, tarp) |

Houses sometimes collapse, especially during

the monsoon |

Long-term residents in locations at a low risk

for demolition upgrade their homes with cement foundations as soon as monetarily feasible |

Fear of demolition

prevents residents from investing in upgrading their homes; bribes requested by local authorities to allow home upgrading prevent further investments in creating structurally sound homes |

| Plastic tarps or metal sheets forming the

roofs of homes often fly off during the windy monsoon season |

|||

| Thieves have an easy time getting into homes

through vulnerable spots in the metal and wood roofs |

Homes are rarely left completely unoccupied

for fear of robbery. People take turns returning to rural areas, so the home is always partly occupied |

||

|

Loss of home due to

a slum fire or fear of future loss due to a fire |

Loss of official documents and all possessions | Official documents often kept in a bag that

can be easily accessed while evacuating the home during a fire |

Prohibition against issuing

new electricity meters has resulted in overloaded electricity boxes. These boxes sometimes explode; fire risk is also increased due to combustible housing materials and lack of a water supply |

| Renters left without any place to stay in the

aftermath of fires, as owners are usually camping out in the remnants of their destroyed homes |

Renters often have to leave the community after fires | ||

|

Flooding of

homes during the monsoon |

Flooding occurs from leaky roofs during the

monsoon, occlusion of home drainage systems, and direct flooding by ocean water during high tide for homes adjacent to the ocean |

Owners move to the loft of the home during

the monsoon, to avoid flooding in the lower floor. Renters end up living in flood-prone lower floors |

|

| Water damage to critical documents, such as

ration cards, voting cards, and PAN cards |

|||

| Adults sleep sitting up in flooded homes,

keeping children on their laps to protect them from water |

|||

|

Exposure to rats

and insects |

Consumption of household food and products

made by small-scale industries, preventing medium or long term storage of these items |

Food items are purchased on a daily basis and

cooked immediately. Products made in industries are shipped out by nightfall before rats can destroy them; industry owners stay up all night fending off rats |

Lack of solid waste removal

by the government for decades has resulted in a massive garbage agglomeration in the ocean and that dump provides an underlying ecosystem for rats and insects. Homes made of poor quality materials have the least barrier protection against rats and insects; some residents have poor quality homes due to prior home demolition. |

| Bites causing pain and infection | Medical care for rat bites; cotton stuffed

into ears to prevent insects from entering during sleep |

||

| Electric failures because wires are chewed up | Poison used to control rat populations around the home | ||

| Destruction of official documents, schoolwork,

and clothes |

|||

| Clay foundation of homes sometimes undermined

by rat burrows, occasionally resulting in wall collapse | |||

| Noxious odors result from dead rat carcasses

that are difficult to find (usually from use of rat poison) | |||

| INADEQUATE WATER ACCESS | |||

|

Obtaining water

via informal water distributors |

Unpredictability of delivery results in

prolonged water storage, occasionally with growth of bugs in stored water |

Drinking water is stored separately in small

containers inside the home to keep it protected; large water drums are stored outside the home |

Non-notified status

precludes KB residents from accessing the formal municipal water supply, resulting in the creation of an informal water distribution system run by vendors who pump water out of municipal pipes using motors. Bribes are paid to local authorities to prevent raids on the motors. Periodic government raids on water motors and odd water timings make water access through this system highly unpredictable. KB residents who cannot afford to buy water from the informal water vendors have to roll drums up to two kilometers to access water from taps in other slums. |

| Government raids on motors used by informal

water distributors to provide water to KB residents result in periodic crises of water access |

Informal water distributors pay regular bribes

to local authorities to prevent raids on motors. These costs are passed on to KB residents, increasing water prices. |

||

| Residents stay up all night due to irregular

water timings, so they do not miss water flows that happen at odd times (e.g., 2am) |

Water tankers periodically ordered at great

expense to provide extra water; tanker water perceived to be of very low quality |

||

| Water spending comprises a major proportion

of household spending |

|||

| Resentment against informal water distributors

for charging exorbitant rates, engaging in discriminatory pricing, collecting monthly charges without delivering the expected quota of water, hurling abuses at residents who have trouble paying, and destroying remaining water infrastructure with their motors |

|||

|

Obtaining water

by fetching water from taps in other communities |

Physical strain of rolling drums up to two

kilometers to fill with water, and difficulty navigating these drums through narrow slum lanes. Most of this burden falls on women and children, when men are at work |

Large drums are rolled to lane entrances, and

water is transported to the home through numerous trips using smaller containers |

|

| Two or three hours required daily for water

collection by some children cuts into time for schoolwork, resulting in poor school performance. For men especially, water collection time cuts into work, which can be detrimental for casual laborers |

|||

| Water spending comprises 10% or more

of monthly income for ~50% of households that fetch water; women often face daily trade-offs between purchasing water or purchasing food |

|||

|

Shared

water-related stressors, regardless of mode of water access |

Inability to bathe regularly from lack of

water results in missed days of school for children and missed days of work for men in high end jobs, due to concerns over body odor |

Women prioritize bathing their children, at

the cost of their own hygiene |

|

| Difficulty managing the household for women,

as they often lack enough water to wash their children, clothes, dishes, home spaces, and lanes. Inadequate hygiene in these domains causes women constant distress |

Women save and reuse the same water for

different purposes; for example, water used for bathing is reused for cleaning the inside of the house. |

||

| Occasional need to order very expensive

private water tankers to ensure water access for communal events, such as weddings |

|||

| Relatives who visit from villages usually

leave quickly, as water strain on the family is increased |

Guests and relatives are rarely invited to visit | ||

| During severe water shortages, some residents

have to beg others for water; most neighbors will freely share food but are hesitant to share water |

|||

| Prior to elections, politicians often place

water pipes along KB’s main road as a political spectacle aimed at showing they are addressing the water crisis. None of these pipes have actually delivered any water to the slum, heightening a sense of cynicism and social ostracism |

Younger residents still manage to feel hopeful

and continue to work with local corporators (alderman) to try to bring a functional water supply to KB |

||

| INADEQUATE ACCESS TO SANITATION AND OTHER INFRASTRUCTURE | |||

| Open defecation | Residents who engage in open defecation,

especially men, are threatened and sometimes arrested by police |

Bribes are sometimes paid to the police to prevent arrest | Non-notified status

precludes construction of sewers and subsidized community block toilets by the government. As a result, there are only 8 functioning community toilet seats in the entire slum; most residents engage in open defecation or use toilet blocks outside KB. Even as sanitation infrastructure is not provided, local authorities simultaneously criminalize open defecation. |

| Women who engage in open defecation at night

fear harassment by men, especially substance users |

Women go to the seaside in groups for

protection when engaging in open defecation |

||

| Residents engaging in defecation by the sea

sometimes suffer physical trauma, including cuts from solid waste in the ocean side dump, bites from dogs, and bruises from slipping into the ocean |

|||

| Residents living next to the sea hesitate to

go outside in the morning, as many people are defecating outside |

|||

|

Defecation at

pay-per- use block toilets |

Queues at private block toilets outside of KB

have waiting times up to 60 minutes at peak hours, which makes men late for work, imposes child care issues for women, and creates discomfort for those needing urgent relief, especially women. Fights often break out in the queue. These toilets are >15 minutes walk for many residents, which adds additional lost time. |

Most children and men engage in open

defecation so as not to be late for school and work, even at the risk of harassment or arrest by the police. Women engage in open defecation at night when absolutely needed. Children and men use the toilet at school and work when possible. |

|

| Block toilets charge residents on a

pay-per-use basis (INRb 2–4 per use) or through a monthly fee (usually INR 30 per month). Costs for large families accumulate quickly, especially during episodes of diarrheal illness affecting multiple household members. |

Women budget some household income for

toileting, often prioritizing this line item over the food budget |

||

| Lack of adequate piped water for maintaining

the cleanliness of private block toilets results in rapid deterioration of toilet seats, such that they are unusable or unpleasant to use, especially for women. |

Residents bring their own water for cleaning

after defecation and to clean the toilet seat; ocean water is often piped in by the managers of block toilets for cleaning |

||

| Use of seawater provided for cleaning at block

toilets results in discomfort from skin rashes and itching |

|||

| Women’s toilet seats often occluded with hygiene cloths / tampons | |||

| One of the only block toilets in KB uses a

septic tank, which sometimes breaks down, spilling fecal matter onto the road |

|||

|

Electricity

accessed through a government sanctioned meter |

Irregular supply because other residents

without legal meters steal electricity from these legal connections |

Residents with meters must engage in

constant surveillance to identify illegal connections |

For unclear reasons,

the government provided some legal electricity meters to KB residents who applied up until about 10–15 years ago. Subsequently, the municipal government refused to provide new residents with meters citing KB’s non-notified status. A small number of residents have obtained meters in recent years by paying heavy bribes, but most new residents have no choice but to access electricity by stealing it or obtaining through informal agreement from those with meters. |

| Legal electricity connections sometimes get

cut by government officials, as they are hard to differentiate from illegal connections |

|||

| Electric bills are often much higher than

expected for residents with legal meters, as others are illegally connecting into these meters. The exorbitant bills cause great stress; in addition, inability to pay the bill results in disconnection and difficulty regaining a legal meter. |

|||

|

Electricity obtained

by stealing it from other individuals with legal meters |

Government officials and residents with legal

meters aggressively try to cut any illegal connections, resulting in many homes periodically going without electricity access |

Many residents without legal meters pay

exorbitant bribes to try to get a meter, usually without success. Those without a meter pay regular bribes to government officials to keep illegal connections from being cut. Many informally pay residents with legal connections for electricity access. |

|

| Renters have to pay the

“owners” of their home for electricity, leading to stress over possible price discrimination |

|||

|

Shared

electricity supply-related stressors, regardless of mode of access |

Open electrical wires result in occasional

deaths from electrocution, especially of children |

||

| Irregular supply results in difficulty

sleeping due to heat and dehydration, as ceiling fans cannot work and homes have minimal ventilation |

Residents sleep outside, weather permitting | ||

| Children are unable to study after dark due to

irregular electricity, leading to poor school performance |

Kerosene lanterns or candles provide some

light, though use is limited due to risk of fire |

||

| Failures of the electricity supply results in

inability to run water motors, limiting water access |

|||

| OTHER SLUM-RELATED STRESSORS | |||

|

Solicitation of

bribes by the police from shop owners |

Police collect bribes every week from all shop

owners in KB, otherwise threatening to shut down their shops |

Non-notified status results

in the criminalization of housing construction, water access, and electricity access in KB. As a result, police can easily earn income by regularly seeking bribes to allow ongoing home construction, water access through motors, and illegal electricity connections. Such behavior by the police alienates them from KB residents. |

|

|

Lack of

police presence in the community or fear of seeking help from the police |

Robberies occur frequently. Fear of

mistreatment by the police means that residents rarely seek their help in catching thieves. Police often seek bribes to allow official registration of a request for investigation. |

Residents rarely leave their primarily homes

completely unoccupied for fear of robbery. People in a household take turns returning to villages, so that the home is always occupied. Some adults sleep outside their front door whenever possible to prevent robbery. |

|

| Sense of disillusionment and exclusion from

the overall justice and legal system because of difficulties in accessing help from the police |

|||

All “mechanisms by which an adversity causes distress” and associated “coping strategies” are pulled directly from statements made by KB residents in the qualitative interviews

INR=Indian rupees

For example, the city government has not collected solid waste from KB in decades due to its non-notified status (Subbaraman et al., 2012). As a result, residents dispose of garbage in the surrounding ocean, where a massive agglomeration of solid waste has now formed that extends several meters out into the ocean and around the entire wharf in low tide. The interviews suggest that rat exposure is especially problematic for those living next to this massive garbage dump, which provides an ecosystem for rats and insects.

A 30 year old Tamilian Hindu man, who ironically is himself employed as a sanitation worker by the city government to collect garbage in other parts of the city, describes the challenges of living next to this oceanside dump, especially during high tide:

When the ocean level rises up, the rats run out of the ditches and invade the community. You can’t leave any food outside during those times. They eat up everything. Where can we store food in this house? Even if we put it up on shelves, the rats knock the containers over … All these things that come and bite us are big problems: the rats, the cockroaches, the mosquitos … All the bugs also come from the trash heaps … Everyone throws their trash [in the ocean], and we can’t say anything about it.

Individuals living in poor quality “kaccha” homes (made of only mud, wood, or tarp) also reported greater rat exposure in the interviews. The quantitative data support this finding, with 78% of people living in kaccha homes reporting being “very affected” by rats as compared to 41% of those living in higher quality homes.

Given that they are generally responsible for procuring food, cooking, and managing the household domain, women suffer disproportionate adverse impacts from rats, as illustrated by this dialogue from a FGD:

Woman 1: [Rats] eat everything, even wooden cupboards.

Woman 2: They eat matchboxes, money, everything. [All talking excitedly at once]

Woman 3: When we're making rotis they steal them from under our noses.

Woman 4: On the bed we find left-over apples and other things they’ve eaten.

Woman 2: They’ve even damaged vessels made of German steel. [Group laughs]

Woman 5: They eat our clothes …

Woman 1: They've even eaten our electrical wires in several places.

The pervasive presence of rats in some areas of KB precludes storage of food overnight, even in cupboards or vessels. Women cope by purchasing small quantities of food on a daily basis and cooking it immediately; similarly, men running small-scale industries describe the stress of rushing to ship products out of KB by nightfall, lest they spend sleepless nights fending off rats to keep them from destroying their products.

Extreme household density is another adversity that reorganizes daily life for many families, as they struggle to find places for people to rest. Parents suffer a physical toll from sleeping sitting up, in contorted positions, or outside of the home to open up space for children. This 50 year old Muslim man from Uttar Pradesh describes his strategy for dealing with lack of space:

My home is too small so I always have tension … there are ten people in my family … To find a big home in Kaula Bandar is very difficult. We always adjust our lives because we don’t have enough space for sleeping. I always work the night shift so I don’t have to come home to sleep at night. But the rest of my family has a lot of problems … You see my home, and you can imagine: how could nine people sleep in this small space? When someone gets sick then there is not enough space for him to rest … If guests come from my village, we face more problems because of lack of space. So we never ask our relatives to visit.

Daily life for many residents is not simply “adjusted”, but transformed, by lack of space. Normal work-leisure timings are inverted; social relationships with rural relatives are estranged; household rituals such as eating together as a family are fractured into shift-based eating.

Some natural coping strategies for extreme density—home expansion or building a new living space—are very difficult in KB due to the slum’s legal status. MbPT officials aggressively police the few remaining open grounds in KB, demolishing any encroachments. As a result, space for building new homes or for laterally expanding old homes is extremely limited. Moreover, the police extort exorbitant bribes before allowing second story loft construction, which limits vertical expansion.

Sanitation infrastructure has never been extended to KB due to its non-notified status. As a result, virtually no households have in-home toilets, and the slum has 19 pay-for-use community block toilet seats for the entire population, of which only eight seats were actually functional at the time of our study. The mechanisms by which this deprivation causes distress differ partly based on gender. Women primarily use the pay-for-use toilets in KB, or travel up to a kilometer to use pay-for-use toilet blocks outside of the slum. A 28 year old Hindu woman from Maharashtra describes some of the challenges associated with using pay-for-use toilets, which often have 30–60 minute queues in the morning:

There are very few toilets here, and they charge two rupees per use. The toilets are crowded. Sometimes I face problems because of my health, but people don’t allow me to go first, so I always wait for a long time in the queue … [People] say, “We have also been waiting here for a long time” … Sometimes I am late for work because of waiting in line for the toilet … Those community toilets are not clean … They only provide seawater … women throw away their hygiene cloths there. It smells awful.

Men primarily (though not solely) defecate in the open and describe different challenges: loss of dignity, fear of falling into the ocean while defecating, accidental trauma from disintegrated refuse when defecating next to garbage dumps, getting attacked by dogs while defecating, and fear of being arrested by the police, as open defecation is considered a crime. For example, this 30 year old Hindu man from Tamil Nadu says:

To make it to work on time, we can’t wait in line, so people defecate [in an open space] by the sea. Sometimes the police hover by the place where people go to the toilet and threaten them … The people who they threaten, say, “We don’t have a bathroom anywhere, so how can you tell us not to go here? … If we don’t make it to work on time, we lose our daily wages, so why do you stand here and prevent us from going to the toilet?”

The qualitative interviews highlight a complex interplay between legal exclusion and the slum’s social landscape. While most slum adversities are at least partly rooted in KB’s overall situation of legal exclusion, there is still individual-level variability with regard to the likelihood of being exposed to a particular slum adversity, the severity of that exposure, and the mechanisms by which the adversity causes psychological distress. As noted above, women, business owners, and households next to garbage dumps suffer greater stress from rat exposure; larger-sized families more acutely feel stress from lack of space; and both men and women experience stress from lack of sanitation infrastructure, but they do so for different reasons.

Legal exclusion and social identity

Legal exclusion has a psychological impact not only by creating and exacerbating slum adversities that cause stress, but also by shaping the identities of KB residents. Authorities enforce legal exclusion through particular acts—such as cutting illegal electricity wires, demolishing homes, and issuing threats against residents engaging in open defecation—which reinforce a feeling of social exclusion.

For example, since KB residents cannot legally access the municipal water supply, most residents buy water from informal vendors who use motorized pumps to tap into nearby underground pipes and then to funnel water to homes using long hoses. Every three or four months, government officials raid and confiscate these motors en masse, completely shutting off water access for most residents, which throws KB into a state of crisis. Residents view such acts as part of a long-term goal of depopulating KB, as noted by this 32 year old Tamilian Hindu woman:

I feel like they periodically shut down our water because they eventually want us to leave this land.

Some residents therefore perceive these periodic, almost ritualistic water raids as acts of collective punishment against the community for its very existence—or rather, for its official non-existence.

Many residents’ sense of social exclusion is also shaped by the perception that the slum is already being treated like a depopulated space by the city government. For example, this 36 year old Tamilian Hindu man says:

The [city government] vans frequently come here with dogs that they have picked up from elsewhere in the city. They release these stray dogs in Kaula Bandar … Yes, this happens! One time, I stopped them and asked them, “Why are you releasing these stray dogs in our area? People live here also! Why are you not thinking about our welfare? We are not animals.” He never replied to me.

This man’s rejoinder that “people live here also” reflects his belief that authorities view KB as an uninhabited space, or a space populated by people unworthy of being treated in the same way as other city residents; the fact that stray dogs collected from other parts of Mumbai are released in the slum confirms the man’s sense that KB is a devalued part of the city.

Over time, these features that characterize KB’s relationship with government authorities—the criminalization of access to basic needs, the periodic acts of collective punishment, and the perception of KB as a devalued and even depopulated space—take a psychological toll by shaping an identity based on a feeling of social exclusion, as articulated by this 35 year old Maharashtrian Hindu woman:

We have our name on the voting card. We always go to vote, but look at the condition of our area. It does not look like the rest of Mumbai. I feel like people treat us differently. I don’t feel like I live in Mumbai. They don’t consider us a part of Mumbai. We live in garbage.

Discussion

This study of a non-notified Mumbai slum illuminates key findings regarding the mental health disease burden and the role of the slum environment in contributing to psychological distress.

First, the prevalence of individuals at high risk for having a CMD in KB is higher than rates found in other population-based studies in India, even when our data are disaggregated by age and gender to allow for more precise comparisons to the populations sampled in those studies (Table 5). By contrast, the only other population-based study that is similar to KB, with regard to the prevalence of individuals at high risk for having a CMD, is also from a slum in Mumbai (Jain & Aras, 2007). While these findings suggest that slums, and particularly non-notified slums, may suffer from a higher burden of CMDs than non-slum communities do, future population-based studies that compare a variety of non-slum and slum populations (including both non-notified and notified settlements) in the same urban location, as well as adjacent rural locations, would be required to more definitively understand disease burden in different environments.

Table 5.

Prevalence of common mental disorders (CMDs) in Kaula Bandar (KB) as compared to other population-based samples in India

| Study | Location | Sample size |

Sex and age range of study participants |

Screening instrument used |

Prevalence estimate of individuals with high CMD risk |

Prevalence estimate of high CMD risk for a comparable demographic in KB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % |

% (N=denominator of comparable individuals from the KB dataset) |

|||||

| (V. Patel et al., 2006) | Goa | 2,494 | Women, ages 18–45 |

Revised Clinical Interview Schedule |

6.6 | 22.4 (N=241) |

| (Fernandes, Hayes, & Patel, 2013) | Goa | 3,649 | Men and women, ages 16–24 |

GHQ-12 | 7.9 | 14.8 (N=128) |

| (Prina, Ferri, Guerra, Brayne, & Prince, 2011) | Chennai and Vellore, Tamil Nadu |

2,002 | Men and women, ages ≥65 |

GMS/AGECATa | 10.5 | 50.0 (N=14) |

| (Sosa et al., 2012) | Chennai and Vellore, Tamil Nadu |

1,802 | Men and women, age ≥65 |

GMS/AGECATa | 12b | 50.0 (N=14) |

| (Poongothai, Pradeepa, Ganesan, & Mohan, 2009) | Chennai, Tamil Nadu |

25,455 | Randomized sampling of Chennai’s population, all adults ages ≥20 |

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 |

15.9 | 23.8 (N=487) |

| (Jain & Aras, 2007) | Mumbai, Maharashtra |

196 | Men and women from a slum population, ages ≥60 |

Geriatric Depression Scale |

45.9 | 57.1 (N=28) |

The Geriatric Mental State Examination (GMS) and the Automated Geriatric Examination for Computer Assisted Taxonomy (AGECAT)

Calculated by adding prevalence estimates for anxiety and depression. As both disorders usually have overlap, the overall CMD prevalence is likely lower than this value.

A second important contribution of this study is its evaluation of functional status, which provides a unique and valuable perspective on the toll of mental illness in this community. The prevalence of functional impairment in KB greatly exceeds international norms, and psychological distress (as measured by the GHQ) contributes substantially to the overall burden of functional impairment, independent of physical disability (e.g., visual, hearing, speech, and locomotor disability). Functional impairment may affect the ability to hold a job, go to school, provide for one’s family, and even obtain necessities such as water in a slum such as KB. In addition, the much higher WHO DAS scores among individuals with high CMD risk, as compared to those with low CMD risk, helps to address concerns about the cross-cultural applicability of instruments such as the GHQ. Since clinically meaningful mental illness “impairs a person in a highly contextual manner” (Hollifield et al., 2002), the loss of function associated with high GHQ scores suggests that the GHQ is a clinically relevant measure of psychological distress in this social context.

Third, we found household income in the last month is a strong independent predictor of having a high CMD risk, and other variables sometimes considered surrogate markers for income—such as educational attainment, having a loan, and food insecurity—also exhibit strong independent associations. Recent articles have come to conflicting conclusions about the association between poverty and mental illness in low-income countries, with one review suggesting a strong association (V. Patel & Kleinman, 2003) and another multi-country analysis suggesting no association (Das, Do, Friedman, McKenzie, & Scott, 2007). The latter article suggests that social and economic “shocks” may be more relevant to mental health than consumption poverty. While our findings largely support an association between poverty and mental health, it is important to note that we measure poverty using income (rather than consumption). Income can vary substantially from month to month, making this measure more sensitive to acute shocks than measures of consumption poverty.

Fourth, even as we recognize the importance of income, our finding of an independent and significant relationship between the SAI and CMD risk highlights the possible contribution of the slum environment to poor mental health and the limitations of using income alone to predict disease risk. Other studies have come to similar conclusions regarding the importance of slum characteristics, independent of income, specifically with regard to understanding environmental living standards (Swaminathan, 1995), maternal and child health outcomes (Osrin et al., 2011), and self-rated well-being (Gruebner et al., 2012) in slums. Collectively, these studies, combined with the findings in this paper, support the use of broad definitions of poverty, such as the capabilities approach, which attempt to define poverty using a wide variety of indicators of deprivation, of which income is but one (Sen, 1999).

The qualitative findings shed light on the fact that many of these deprivations and slum adversities are rooted in KB’s condition of legal exclusion; even so, exposure to a given slum adversity may affect individuals differently, leading to psychological distress through diverse “mechanisms” (Table 4). This finding resonates with a prior study of mental health in another Mumbai slum, which emphasizes in particular the gendered nature of the stressors faced by slum residents (Parkar, Fernandes, & Weiss, 2003). We further argue that the psychological toll of legal exclusion can also be seen in the way it creates a feeling of social exclusion that shapes the identity of KB residents and their relationship to the city as a whole. As such, our study highlights the importance of not simply viewing mental health through a medical lens, as a set of psychiatric illnesses or disorders affecting individuals; rather, it is equally important to conceptualize mental health as being the product of social conditions that may result in the collective suffering of entire communities.

KB’s condition may seem at odds with recent literature on Mumbai, which has highlighted novel forms of community organizing and the use of tactics such as self-enumeration by slum dwellers to assert their right to recognition, secure tenure, and basic services—a process that has been called “deep democracy” (Appadurai, 2001; S. Patel, Baptist, & D’Cruz, 2012). Even with their obvious successes, the scope of these movements understandably has not been able to encompass the entirety of Mumbai’s massive slum population. Also, KB’s position on central government land, which unlike state government land has no slum policy whatsoever, leaves very unclear options for negotiating even the most basic rights. As such, KB’s situation resonates with another recent account of life in a slum on central government land in Mumbai, which emphasizes the extreme marginalization of these communities (Boo, 2012).

This study has implications for future interventions and research. Our key findings, especially the association of slum adversity and poverty with a very high burden of CMDs, suggest that priority should be placed on addressing the underlying condition of legal exclusion that exacerbates slum-related stress in non-notified settlements. In addition, community-level interventions aimed at ameliorating poverty and slum adversity may have a role in preventing CMDs and functional impairment. In the context of a severe shortage of trained psychiatric personnel in India, the high prevalence of individuals with high CMD risk highlights a need to explore community-based expansion of lay health worker-driven psychiatric interventions, as has been studied in clinic settings in India (V. Patel et al., 2011). In addition, future research should aim to better understand protective factors (i.e., resilience), the qualities that make some stressors likely to precipitate CMDs while others do not, culturally-specific ways in which psychological distress is expressed clinically (e.g., somatoform presentations), and the prevalence and risk factors for serious mental disorders in this population (e.g., psychotic disorders).

This study has a few limitations. First, while the GHQ’s operating characteristics as an instrument are superior to most other screening tools for CMDs in India, it still has a small error rate and in particular may have underestimated the true prevalence of CMDs. The GHQ was also designed as a screening tool for outpatient clinics; as such, its operating characteristics in community settings are less clear. Notably, however, the studies to which we compare our findings also used the GHQ or similar screening instruments in community settings (Table 5). Second, while we feel that data collection by BRs enhances the rigor and validity of our findings, further research will be required to clarify the comparability of this community-based participatory research model to the research methods of other studies. Third, since 17 individuals were too debilitated to participate in the quantitative survey, our estimate of the prevalence of disability is probably a slight underestimate.

Finally, while the cross-sectional nature of the study makes drawing conclusions about causality difficult, the qualitative findings are supportive of a “social causation” model, in which slum adversities and income poverty lead to poor mental health, which in turn leads to functional impairment. Alternative hypotheses for KB’s high burden of CMDs might include a “social drift” model, in which deterioration in mental health may be the primary process causing worsening income poverty and migration to slum settlements. Future longitudinal studies investigating incident episodes of CMDs in slums might provide more insight into these causal relationships.

In this study of a slum in Mumbai, we identify a very high prevalence of CMDs and functional impairment. We also highlight the potential role of income poverty and slum adversities in contributing to this burden of mental illness. Although this issue garners little attention from policymakers and the general public, the adverse psychological impacts of slum living are very evident to KB’s residents, as noted by this 30 year old Tamilian Hindu man:

There is so much tension in this community; I hope you are able to do something about it … Many people have died because of tension. After all, no one will admit that a person in her family died because of tension. It’s common for people to silently drink poison or hang themselves. It’s a big problem.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

We examine mental health in a slum not legally recognized by the city government.

We identify a high burden of individuals at risk for common mental disorders (CMDs).

A Slum Adversity Index score is associated with CMD risk independent of income.

Psychological distress contributes greatly to the burden of functional impairment.

Legal exclusion shapes a community identity based on a feeling of social exclusion.

Acknowledgments

RS was funded by the Fogarty International Clinical Research Fellows Program at Vanderbilt University (R24 TW007988) and a Harvard T32 post-doctoral clinical research fellowship (NIAID AI007433). LN received support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (5R24HD047879) and the National Institutes of Health (5T32HD007163). The Rockefeller Foundation and the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs at Harvard University provided additional funding.

Arjun Appadurai served as a co-principal investigator for a larger initiative studying the KB community. Somnath Chatterji, Albert Ko, Vikram Patel, Jennifer O’Brien, Marija Ozolins, and Tharani Sivananthan provided feedback on initial research protocol drafts. We are grateful to the four anonymous journal reviewers, whose detailed feedback substantially improved the quality of the manuscript. Devorah Klein Lev-Tov transcribed hours of interviews. Kalyani Monteiro Jayasankar helped with FGDs. Shadi Gholizadeh performed a literature search to identify psychiatric survey instruments validated in India. Survey data collection was performed by PUKAR’s barefoot researchers. We are grateful to the residents of KB. While this paper sheds light on their tribulations, it fails to capture the joy and resilience that also constitute their lived reality.

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

None of the funders had any role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in article writing; or in the decision to submit for publication.

References

- Appadurai A. Deep democracy: urban governmentality and the horizon of politics. Environ Urban. 2001;13(2):23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Boo K. Beyond the beautiful forevers: life, death, and hope in a Mumbai undercity. New York: Random House; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J, Klassen A, Plano Clark V, Smith K. Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences. Bethesda, MD: Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research; 2012. [Google Scholar]