Abstract

Recent studies have proven that skeleton-wide functional assessment is essential to comprehensively understand physiological aspects of the skeletal system. Therefore, in contrast to regional imaging studies utilizing a multiple-animal holder (mouse hotel), we attempted to develop and characterize a multiple-mouse imaging system with micro-PET/CT for high-throughput whole-skeleton assessment. Using items found in a laboratory, a simple mouse hotel that houses four mice linked with gas anesthesia was constructed. A mouse-simulating phantom was used to measure uniformity in a cross sectional area and flatness (Amax/Amin*100) along the axial, radial and tangential directions, where Amax and Amin are maximum and minimum activity concentration in the profile, respectively. Fourteen mice were used for single- or multiple-micro-PET/CT scans. NaF uptake was measured at eight skeletal sites (skull to tibia). Skeletal 18F activities measured with mice in the mouse hotel were within 1.6±4% (mean±standard deviation) of those measured with mice in the single-mouse holder. Single-holder scanning yields slightly better uniformity and flatness over the hotel. Compared to use of the single-mouse holder, scanning with the mouse hotel reduced study time (by 65%), decreased the number of scans (four-fold), reduced cost, required less computer storage space (40%), and maximized 18F usage. The mouse hotel allows high-throughput, quantitatively equivalent scanning compared to the single-mouse holder for micro-PET/CT imaging for whole-skeleton assessment of mice.

Keywords: high-throughput, multiple-animal holder, mouse hotel, micro-PET/CT, bone

Introduction

The role of micro-positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) is becoming more important because of its ability to bridge the gap between preclinical studies and clinical studies. Micro-PET/CT offers non-invasive imaging which paves the way to perform longitudinal studies that suit translational research. Most experimental designs require multiple groups (e.g. controls and treatment arms) and a large number of animals to reach statistically significant results. A multiple-animal scanning technique is a logically approach to minimizing the total number of imaging studies required. Currently, image quality in multiple-animal scanning is characterized in detail using NEMA NU 4 phantom with different reconstruction algorithms [1], and the application of multiple-animal scanning in oncology research has been reported [2]. High-throughput micro-PET/CT imaging would also be a benefit in terms of reducing costs, saving time, and condensing volume of data for storage and processing.

Micro-PET/CT is a particularly powerful tool for the bone research community for quantitative, non-invasive and functional studies and for thus assessing bone morphology and skeletal malignancies. Bone is one of the largest organs in mammals and is distributed throughout the whole body. Diseases of blood or bone marrow (e.g. leukemia) require skeleton-wide monitoring for regional and global skeletal changes in response to treatment. This emphasizes the need to investigate the entire skeletal system in addition to specific regional changes in a single field of view. Newer scanners can encompass the whole body of small animals such as mice, allowing investigation not only of local metabolic changes but also of the changes in the entire skeleton [3]. Previous studies with multiple-animal scanning mostly focused on local regions positioned at the center of the field of view. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first attempt to use a multiple-animal PET imaging technique for whole-skeleton assessment.

The aim of this study was to characterize the multiple-mouse holder (mouse hotel) and increase throughput in micro-PET/CT for local and systemic skeleton assessment research. For this purpose, phantom studies were performed and then mice were imaged with 18F labeled sodium fluoride (NaF).

Material and Methods

Regulatory Compliance

All animal studies were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at University of Minnesota.

Phantom studies

Five cylindrical mouse-simulating phantoms (60 mL plastic syringe, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) were filled with a known activity of 18F solution (16 MBq). One was scanned at the center position while four of them were assembled to simulate the mouse hotel.

Multiple-mouse holder (mouse hotel)

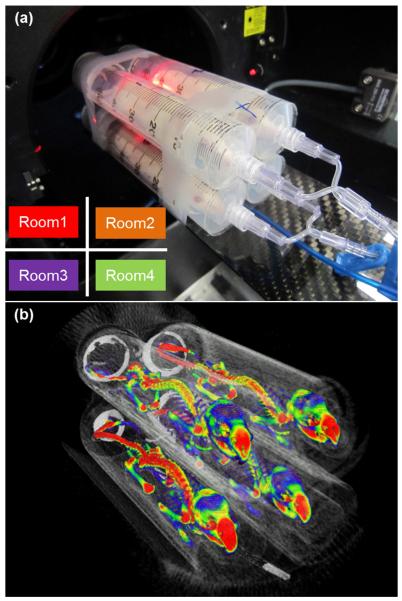

An in-house multiple-mouse holder (mouse hotel) was constructed with the same plastic syringes as used in the phantom studies (Figure 1a) according to a previously published paper [4]. In this study, each holder in the mouse hotel was referred to as a “Room”. The mouse hotel contains 4 rooms, aiming to scan the whole-skeleton of multiple mice at the same time. To distinguish the position of each phantom, the room is numbered with 1 for upper left, 2 for upper right, 3 for lower right and 4 for lower right as viewed from the front of the scanner (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) Four mice are in a multiple-mouse holder, “mouse hotel,” and ready to be positioned for scan. Diagram on the lower left shows room number definition. (b) Volume-rendered image of micro-PET/CT with NaF using mouse hotel. Approximately 18.5 MBq of NaF in a 100-μl solution was injected intravenously via the tail vein. The list-mode data from 50 to 60 minutes after injection was used for the PET image reconstruction.

Animal studies

Fourteen similarly aged BALB/c female mice (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Inc., Indianapolis, IN, USA) were used for this study. All rodents were kept in a standard vivarium and were fed a regular diet and water ad libitum. All mice were fasted for at least 1.5 hours before the injection of the radiotracer.

Venous blood was collected in pre-weighed heparinized capillary tubes following the end of the scan. The activity was then counted with a well counter (CAPRAC-R, Capintec, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA, USA), which had been cross calibrated with the scanner.

PET data acquisition

PET acquisition was performed with bone-localizing NaF. The Inveon™ micro-PET/CT (Siemens Medical Solutions, Knoxville, TN, USA) was used to scan all regions from the skull to tibia. Approximately 18.5 MBq of NaF in a 100-μl solution was injected intravenously via the tail vein. Activity was measured with a dose calibrator, Atomlab 100 (Biodex Medical, Shirley, NY, USA), that had been cross-calibrated with the scanner. The scan (utilizing list-mode data acquisition) was started at 30 minutes post-injection under anesthesia with the manufacturer’s default acquisition settings (i.e. energy window and timing window). Anesthesia was maintained by inhalation of approximately 1.5% isoflurane/O2 at 1 l/min for individual scans and 2 l/min for mouse hotel scans administered via nose cone. During the individual scan, the mouse was monitored with a dedicated respiration monitor (BioVet, Spin Systems Pty Ltd., Brisbane, Australia). For multiple-mouse scans, one of the four mice was monitored. A dedicated warming pad, one for each mouse, was also used to maintain body temperature.

The Inveon acquisition workplace (IAW, version 1.5.0.28, Siemens Medical Solutions) was used for the PET image reconstruction. The 30-minute acquisition was separated into three frames, each 600 seconds, with a 128 × 128 × 159 matrix (pixel size: 0.776 mm; plane thickness: 0.796 mm). After identifying the plateau region of time-dependent skeletal activity, the last 10 minutes of the list-mode data (i.e. 50-60 minutes after injection) was used. A OSEM3D (ordered subset expectation maximization)/MAP (maximum a posteriori) algorithm with default parameters was employed for image reconstruction. Scatter and attenuation corrections were applied. The PET image and the CT image were fused through a spatial transformation matrix for the registration.

Calibration factors (CFs) for each scan method were calculated using the five cylindrical mouse-simulating phantoms and the same method as reported by Habte [4], in which the same VOIs (volume of interest) were drawn on images acquired in single and multiple scans. The CF for the multiple scans was calculated by averaging the respective CFs for each of the four rooms of the mouse hotel, with the multiple-scan CF being higher than the single-scan CF. Image quality control was performed with the NEMA NU 4 phantom for both holding methods; the single- and multiple-scan images of the phantom were comparable in quality [1, 2].

Data analysis

Data analyses of the scans were performed using PMOD software version 3.4, build 6 (PMOD Technologies, Ltd., Zurich, Switzerland). For the phantom study, a 20-mm-diameter cylindrical VOI spanning the radioactive regions was created to generate the axial activity concentration profile. A 10-mm × 75-mm VOI was created to generate the radial and tangential activity concentration profiles. The profile was normalized using the activity in the phantom measured in the dose calibrator. Uniformity in the profile was evaluated with the NEMA NU 4-2008 protocol [5]. The uniformity is reported as the average activity concentration, the maximum and minimum values in the VOI, and the percentage standard deviation (%STD). Flatness was defined as;

| (1) |

where Amax and Amin are the maximum and minimum activity concentrations in the profile, respectively.

There were eight skeletal regions investigated in the mouse images: skull, mandible, humerus, cervical spine, thoracic spine (5th-10th), lumbar spine (1st-3rd), femur and tibia (40 slices, 7.6 mm, from knee joint). Contouring was performed by one investigator (M.Y.) and VOIs were identified semi-automatically using the segmentation feature of the PMOD software based on a 3D region-growing algorithm and manual modification to minimize variations of the VOIs. PET-derived tissue activity concentrations and ex vivo counting derived blood activity concentrations were corrected for physical decay (half-life = 109.77 minutes) to the time of injection and tissue-to-blood activity concentration ratios was calculated; no correction for partial-volume averaging was applied to the PET-derived values [6].

Statistical analysis

For each region, means and standard deviations of activity concentration were computed, and confidence intervals (CI) for the mean difference between corresponding regions of the different mice imaged in single- and imaged in multiple-mouse scans were calculated using unpooled variance. The F-Test for equality of variance was computed for each region.

Results and Discussion

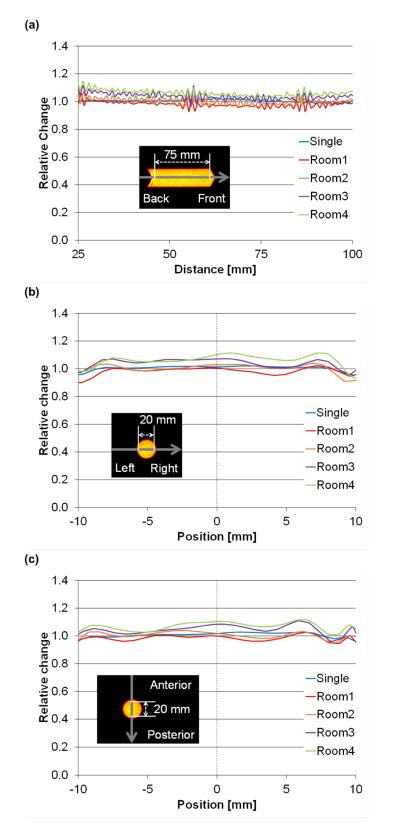

Average activity concentrations of 18F measured in the mouse hotel was within 1.6% (± 4%) of that of a single scan. This is similar to results reported by Habte et al. [4], showing a 4.5% relative difference. Thus, the mouse hotel provides acceptable accuracy in absolute activity measurement. Whole-skeleton micro-PET/CT imaging requires minimum variation in quantitative response in three-dimension because the skeleton is widely distributed in all directions while a solid tumor, for example, is usually more localized. In addition, recent studies have proven skeletal-wide functional assessment is essential to comprehensively understand physiological aspects of the skeletal system [7]. Figure 2 shows the axial, radial and tangential activity concentration profiles of the phantoms. The axial, radial and tangential lengths of the profile were large enough to cover the entire mouse skeleton within the mouse hotel. The profiles were slightly flatter in the individual scan than in the mouse hotel. Table 1 shows the evaluation results of the activity concentration uniformity in the profiles. The variation of the activity concentration (measured by %STD) in the mouse hotel was slightly larger (i.e. had higher noise) than the individual scan. A similar noise pattern was reported in phantom studies [1]. While our study showed activity concentrations profiles in all directions, Visser et al also showed that the spatial resolution in both the radial and tangential directions worsened with increasing distance from the gantry axis due to the depth-of-interaction (DOI) effect [8]. The relation between noise and spatial resolution is a trade-off [9]. The presence of multiple subjects decreases the total number of detected true coincidences per animal and, as a result, noise increases in the image. The peak of the noise equivalent count rate in this scanner system is at 131.4 MBq with a 6-cm diameter phantom [10]. The total mouse hotel activity in this study is well below that peak.

Figure 2.

Axial (a), radial (b) and tangential (c) profiles of a mouse-simulating phantom of individual and mouse hotel scans. Average activities of 18F measured in the mouse hotel were within 1.6% (± 4%) of those obtained with the single-mouse holder.

Table 1.

Uniformity evaluation in axial, radial and tangential profiles. The directions and their plots can be seen in Figure 2. Average, maximum and minimum indicate average activity concentration and the maximum and minimum values in the VOI, respectively. The percentage standard deviation (%STD) is a radio of standard deviation of activity concentration to average activity in the VOI.

| Scan method | Single | Multiple | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direction | Room1 | Room2 | Room3 | Room4 | ||

| Axial | Average | 1.01 | 0.982 | 1.00 | 1.04 | 1.06 |

| Maximum | 1.03 | 1.06 | 1.07 | 1.12 | 1.15 | |

| Minimum | 0.976 | 0.928 | 0.955 | 0.962 | 0.993 | |

| %STD | 0.955 | 1.89 | 1.98 | 2.09 | 2.02 | |

| Flatness % | 105 | 114 | 112 | 116 | 115 | |

|

| ||||||

| Radial | Average | 1.01 | 0.984 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 1.06 |

| Maximum | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.04 | 1.07 | 1.11 | |

| Minimum | 0.955 | 0.900 | 0.910 | 0.959 | 0.933 | |

| %STD | 1.60 | 2.57 | 2.90 | 2.82 | 3.63 | |

| Flatness % | 107 | 114 | 114 | 112 | 119 | |

|

| ||||||

| Tangential | Average | 1.01 | 0.986 | 1.01 | 1.05 | 1.07 |

| Maximum | 1.03 | 1.03 | 1.04 | 1.11 | 1.12 | |

| Minimum | 0.961 | 0.946 | 0.951 | 0.961 | 1.01 | |

| %STD | 1.55 | 1.88 | 2.12 | 3.00 | 2.67 | |

| Flatness % | 107 | 109 | 109 | 115 | 111 | |

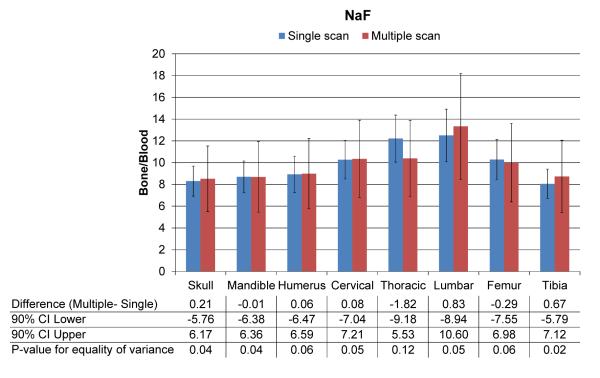

Figure 1b is a sample volume-rendered image of four mice that were scanned in the mouse hotel. Figure 3 shows results of a quantitative comparison between a single scan and a mouse hotel scan among several bony regions for NaF. One of the eight mice images had motion artifact and was excluded from the analysis. The scanning methods resulted with similar NaF uptake at all skeletal regions; no mean differences were significantly different from zero, indicating that the mouse hotel may be used without losing quantitative accuracy. Mean NaF uptake using the multiple-mouse scan was within 3% of that in the single scan for five of the eight regions, and no higher than 15% for any region. Confidence limits in Figure 3 show the bounds of our estimate of the maximum absolute mean difference. Standard deviations were approximately twice as high in the mouse hotel group and F-tests suggested unequal group variances. It is important to note that fluorinated hydrocarbon-based anesthetics such as isoflurane could compete with fluoride ion from NaF because the anesthetics also produce fluoride ion [11], which has the potential to alter the NaF uptake. Our experiment used the same anesthesia conditions and is assumed not to alter NaF uptake between individual and mouse hotel scans. Similar to phantom studies, mouse hotel scans with animals also showed higher variation, suggesting that it would be better not to combine individual holding with the mouse hotel method during a longitudinal study. We anticipate this mouse hotel methodology would be useful for studying cancer treatment effects on the skeleton and bone metastasis by monitoring longitudinal changes in multiple mice in specific skeletal regions (local changes) as well as the overall skeletal system (systemic changes).

Figure 3.

Quantitative comparison of NaF uptake between individual-mouse and multiple-mouse scans among several bony regions. Mean NaF uptake between the two scanning methods was very close throughout the entire skeleton.

Use of the mouse hotel is also more economical than single-animal scanning, as detailed in Table 2. Compared to a single scan, a mouse hotel increases the number of scanned mice fourfold and reduces total study time (from injection to blood collection time) by approximately 65%. This time reduction reduces cost to investigators by approximately 57% in our institute and maximized utilization of 18F isotope (approximately 50% reduction in needed volume for 18.5 MBq of prescribed activity). Maximizing utilization of 18F isotope would further reduce cost. Furthermore, data storage space was decreased by approximately 40%. List mode file (.lst) size, which is ~85% of the data volume per PET scan, with the mouse hotel is less than the combined size of four individual list-mode files.

Table 2.

Estimated economic benefit of using mouse hotel (based on experiences at our institute).

| Single scan | Mouse hotel | Reduction (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of mice | 4 | - | |

| Number of scans | 4 | 1 | −75.0 |

| Time (minutes) * | 255 | 88 | −65.4 |

| Cost (US$)† | 1,477 | 642 | −56.5 |

| 18F isotope (μl/18.5 MBq) | 19.5 | 10.1 | −48.4 |

| Storage (GB) ‡ | 32.7 | 19.0 | −41.9 |

Accounts for time interval from radiotracer injection to blood collection.

Charges in our institute; $250/hour for scan, $50/hour for technician, $200/vial (740 MBq) for 18F.

Data volume includes all files created during process to reconstruct PET image.

In conclusion, micro-PET/CT scans of whole-mouse skeletons acquired using our multiple-mouse holder, or “mouse hotel,” are equivalent in terms of image quality and quantitative accuracy as skeletal scans of single mouse. Such a high-throughput system reduces not only imaging time but also the cost of the radioisotope and the computer memory required, allowing cost-effective imaging of larger numbers of animals and thus improving overall statistical reliability of experimental results.

Highlights.

A multiple-mouse holder was studied for high-throughput whole-skeleton assessment.

A holder housing four mice was constructed using items found in a laboratory.

Micro-PET/CT scans with the holder are quantitatively accurate to single-mouse.

The holder reduces imaging time, cost of radioisotope and computer memory required.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R01CA154491-01, 1R03AR055333-01A1 and 1K12-HD055887-01) and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Core to Core Program (23003). The authors acknowledge and thank Dr. Kihak Lee (Siemens Medical Solutions, USA) for advice and fruitful discussion pertaining to this experiment and report and Timothy C. Doyle for providing information on potential mouse holder system.

Financial supports: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R01CA154491-01, 1R03AR055333-01A1 and 1K12-HD055887-01) and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Core to Core Program (23003).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Siepel FJ, Van Lier MG, Chen M, Disselhorst JA, Meeuwis AP, Oyen WJ, et al. Scanning multiple mice in a small-animal PET scanner: influence on image quality. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res, Sect A. 2010;621:605–10. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Aide N, Desmonts C, Briand M, Meryet-Figuiere M, Poulain L. High-throughput small animal PET imaging in cancer research: evaluation of the capability of the Inveon scanner to image four mice simultaneously. Nucl Med Commun. 2010;31:851–8. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e32833dc61d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Yagi M, Arentsen L, Shanley RM, Rosen CJ, Kidder LS, Sharkey LC, et al. A Dual-Radioisotope Hybrid Whole-Body Micro-Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography System Reveals Functional Heterogeneity and Early Local and Systemic Changes Following Targeted Radiation to the Murine Caudal Skeleton. Calcif Tissue Int. 2014;94:544–52. doi: 10.1007/s00223-014-9839-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Habte F, Ren G, Doyle TC, Liu H, Cheng Z, Paik DS. Impact of a Multiple Mice Holder on Quantitation of High-Throughput MicroPET Imaging With and Without Ct Attenuation Correction. Mol Imaging Biol. 2013:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11307-012-0602-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Association NEM NEMA Standards Publication NU 4-2008. Performance Measurements of Small Animal Positron Emission Tomographs. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- [6].Strategies for Clinical Implementation and Quality Management of PET Tracers. International Atomic Energy Agency; Austria: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Karsenty G, Oury F. Biology without walls: the novel endocrinology of bone. Annu Rev Physiol. 2012;74:87–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Visser EP, Disselhorst JA, Brom M, Laverman P, Gotthardt M, Oyen WJ, et al. Spatial resolution and sensitivity of the Inveon small-animal PET scanner. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:139–47. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.055152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Lodge MA, Rahmim A, Wahl RL. Simultaneous measurement of noise and spatial resolution in PET phantom images. Phys Med Biol. 2010;55:1069. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/4/011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Constantinescu CC, Mukherjee J. Performance evaluation of an Inveon PET preclinical scanner. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54:2885–99. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/9/020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Currie GM, Kiat H, Wheat JM. Potential Iatrogenic Alteration to 18F-Fluoride Biodistribution. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:823. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.071092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]