Abstract

Objective and Method

Timeline Follow-back interviews were conducted with 107 pregnant women enrolling in smoking cessation and relapse prevention clinical trials in the Burlington, VT area between 2006–2009 to examine the time course of changes in smoking between learning of pregnancy and the first prenatal care visit. We know of no systematic studies of this topic.

Results

Women reported learning of pregnancy at 5.1 ± 2.2 weeks gestation and attending a first prenatal care visit at 10.1 ± 3.6 weeks gestation. In the intervening five weeks, 22% of women became abstainers, 62% reduced their smoking, and 16% maintained or increased their smoking. Women who made changes typically reported doing so within the first 2 days after learning of pregnancy, with few changes occurring beyond the first week after learning of pregnancy.

Conclusion

In this first effort to systematically characterize the time course of changes in smoking upon learning of pregnancy, the majority of pregnant smokers who quit or made reductions reported doing so soon after receiving the news. Further research is needed to assess the reliability of these results and to examine whether devising strategies to provide early interventions for women who continue smoking after learning of pregnancy are warranted.

Introduction

Learning of a pregnancy is a major event in a woman’s life. In the average 6-week period between learning of their pregnancy and their first prenatal care visit (Ayoola et al., 2010; Kost et al., 1998; Nettleman et al., 2010; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010), women often make significant changes in health-related behaviors such as cigarette smoking (Crozier et al., 2009; Pirie et al., 2000). By the first prenatal care visit, about 20% of women who were smokers at the time they learned that they were pregnant have quit with little or no intervention (Solomon & Quinn, 2004). Among those still smoking at their first prenatal care visit, studies indicate that as a group they report reducing their smoking by an average of 50% from their pre-pregnancy smoking rate, from 20 to 10 cigarettes per day (Dornelas et al., 2006; Heil et al., 2008; Higgins et al., 2004; Pollak et al., 2007; Rigotti et al., 2006).

However, it is likely that there is significant variability in the “spontaneous” changes made across individual women. In addition, the time course of these changes remains unclear. Both the degree of change and the associated time course have implications for understanding the mechanisms underpinning such changes and for designing better smoking cessation interventions. For example, if spontaneous changes occur shortly after learning of pregnancy and are stable, it may suggest that changes are being driven by behavioral rather than hormonal or other biological mechanisms and that interventions could be initiated earlier in the pregnancy. Despite the important potential implications of such information, we know of no prior studies systematically examining this topic. Thus, the present study aimed to characterize for the first time the degree and time course of changes in smoking between learning of pregnancy and the first prenatal care visit.

Methods

Participants

Data were obtained from 107 women enrolled in a university-based outpatient research clinic for smoking cessation and relapse prevention during pregnancy and postpartum. Participants were recruited through prenatal care providers and the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) clinic in the Burlington, Vermont area. Those who endorsed smoking at the time that they learned they were pregnant were invited to complete a detailed intake assessment evaluating eligibility for ongoing research trials.

Assessment

At the intake assessment, study participants completed questionnaires examining sociodemographics, current smoking status and environment, and smoking history. Relevant to the present study, participants were asked “On average, how many cigarettes per day did you smoke before learning you were pregnant?” to establish the rate of smoking pre-pregnancy. Participants also completed a Timeline Follow-back interview (TLFB) to establish the number of cigarettes smoked each day since learning of their pregnancy. Smoking TLFB interviews have been shown to provide reliable and valid data on patterns of smoking over extended periods of time in non-pregnant smokers (Brown et al., 1998; Toll et al., 2005). Briefly, the interviewer and the participant worked with a calendar to identify events of personal interest for the participant (i.e., day learned of pregnancy, appointments, family events, holidays, illnesses, vacations, etc.) as anchor points to aid recall. The interviewer then led the participant forward from the day she learned she was pregnant, collecting daily reports of cigarette use through the day before the intake assessment. The date of the first prenatal care or WIC visit was collected from the maternal medical record. Attendance at a WIC visit was considered equivalent to attending a prenatal care visit because the smoking cessation counseling provided by WIC staff members is similar to that provided by prenatal care providers (Zapka et al., 2000).

Initially, pre-pregnancy smoking rate and the mean number of cigarettes smoked in the 7 days prior to their first prenatal care visit were compared for each participant. The first prenatal care visit took place an average of five weeks after participants learned of their pregnancy. Women who did not report smoking in the 7 days prior to their first prenatal care visit were labeled abstainers. Women who were still smoking, but smoked at a reduced level for each of the 7 days prior to their first prenatal care visit, were labeled reducers. All other women were labeled maintainers.

Once these three groups were identified, the time course associated with changes during the first 7 days after learning of their pregnancy was examined. This period was selected because reports suggest that smoking status early in a quit attempt predicts short- and longer-term success or failure (Higgins et al., 2006; Kenford et al., 1994; Yudkin et al., 1996).

Statistical Analysis

Sociodemographic and smoking characteristics from participants’ intake assessments were compared between participants classified as abstainers, reducers, and maintainers using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and chi-square tests.

Repeated-measures ANOVA was used to examine differences between groups (abstainers, reducers, or maintainers) and changes over time (pre-pregnancy and first 7 days after learning of pregnancy) on self-reported cigarettes per day. Additionally, a mixed model 4th order polynomial regression using random intercepts with group represented by a fixed factor was fit to the data. Analyses were performed using SAS software Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary NC). Statistical significance was determined based on α = 0.05.

Results

Categorization of Smoking Status

Among these 107 women who were smoking upon learning of their pregnancy, 24 (22%) were classified as abstainers, 66 (62%) reducers, and 17 (16%) maintainers.

Sociodemographics and Other Characteristics

Across groups, participants averaged 25 years of age, had a high school education, and had been smoking for 10 years (Table 1). Participants learned of their pregnancy at 5.1 (± 2.2) weeks gestational age and had their first prenatal care visit at 10.1 (± 3.6) weeks gestational age. There were significant differences between groups on five sociodemographic and other characteristics (Table 1). Abstainers started smoking later and smoked fewer cigarettes pre-pregnancy relative to reducers and maintainers and abstainers and reducers were better educated, more likely to be pregnant for the first time, and more likely not to have smoking friends/family compared to maintainers.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics at the Trial Intake Assessment

| Abstainers (n=24) | Reducers (n=66) | Maintainers (n=17) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Mean (± SD) age (years) | 26.6 ± 5.2 | 25.0 ± 5.6 | 24.8 ± 3.7 | .39 |

| % Caucasian | 100 | 91 | 100 | .13 |

| Education | ||||

| % < 12 years of education | 16 | 14 | 41 | .03 |

| % = 12 years of education | 42 | 57 | 53 | |

| % > 12 years education | 42 | 29 | 6 | |

| % Married | 21 | 21 | 12 | .68 |

| % With private insurance | 33 | 32 | 24 | .77 |

| % Working for pay outside of home | 71 | 55 | 35 | .08 |

| % Primagravida | 75 | 67 | 31 | .01 |

| Mean (± SD) weeks pregnant when learning of pregnancy | 5.3 ± 3.0 | 4.9 ± 1.8 | 5.4 ± 2.5 | .69 |

| Mean (± SD) weeks pregnant at 1st prenatal care visit | 11.6 ± 4.0 | 9.7 ± 3.1 | 9.9 ± 4.2 | .08 |

| Smoking Characteristics | ||||

| Mean (± SD) age first started smoking cigarettes (years) | 17.1 ± 3.1 | 15.5 ± 3.2 | 14.2 ± 3.6 | .01 |

| Mean (± SD) cigarettes per day pre-pregnancy | 12.3 ± 6.8 | 18.8 ± 8.2 | 16.7 ± 4.8 | .002 |

| % Living with another smoker | 67 | 82 | 76 | .31 |

| % With no smoking allowed in home | 79 | 62 | 59 | .27 |

| % With none or few friends/family who smoke | 50 | 30 | 12 | .03 |

| % Attempted to quit pre-pregnancy | 88 | 79 | 65 | .13 |

Note: Significance based on chi-square tests for categorical measures and t-tests for continuous variables. Data were obtained from questionnaires and Timeline Follow-back interviews conducted with pregnant women enrolling in smoking cessation and relapse prevention trials in the greater Burlington, VT area between 2006–2009.

Comparison of the Time Course of Changes in Smoking Among Abstainers, Reducers, and Maintainers

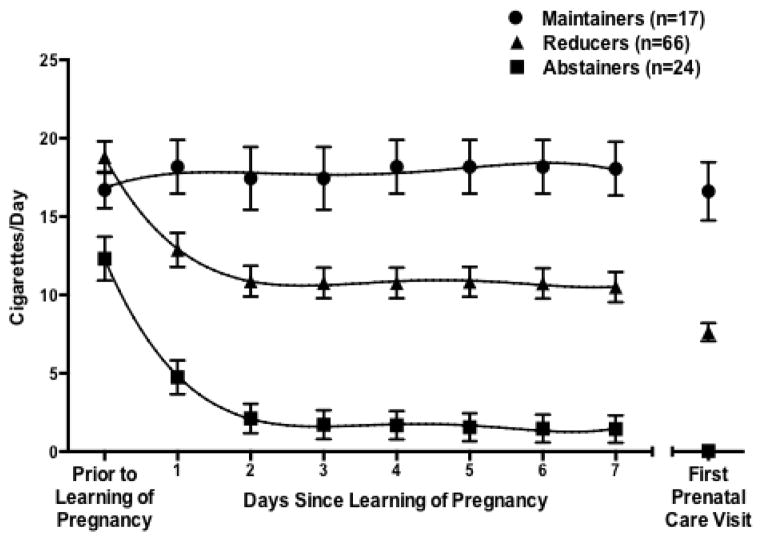

Significant differences between groups in the temporal changes in reported smoking were discernible in the first week after learning of pregnancy (F14, 728 = 11.6, p < .0001). Abstainers and reducers substantially decreased their cigarettes per day (F7,728 = 41.3, p <.0001 and F7,728 = 64.4, p <.0001, respectively), while maintainers showed no evidence of altering their smoking behavior (F7,728 = 0.61, p = .74) (Fig. 1). Abstainers and reducers changed in a parallel fashion (F 7, 704 = 0.29, p=.96 for group by time interaction), with the vast majority of changes initiated within two days of learning of pregnancy. Following two-day reductions of 10.1 and 8.9 cigarettes per day for abstainers and reducers, respectively, there was no evidence of additional decreases during the first week for either group. The decreases observed after two days represented 83% (abstainers) and 72% (reducers) of the total reduction in cigarettes per day observed during the approximate five-week interval between learning of pregnancy and the first prenatal care visit. Additionally, mixed model polynomial regression revealed no significant differences in the quantitative pattern of change between abstainers and reducers although the abstainers’ curve was uniformly lower relative to the curve of the reducers (t321 = 3.6, p = .0003).

Figure 1.

Mean (± SEM) number of self-reported cigarettes per day among pregnant women classified as maintainers, reducers, or abstainers. Group classifications were based on mean smoking rate for the 7 days prior to attending the first prenatal care visit as compared to smoking rate prior to learning of pregnancy. Curves are results of mixed model polynomial regression. The symbols on the far right represent average smoking rate for each group on the 7 days prior to attending their first prenatal care visit and are included as a point of reference. Data were obtained from questionnaires and Timeline Follow-back interviews conducted with pregnant women enrolling in smoking cessation and relapse prevention trials in the greater Burlington, VT area between 2006–2009.

The reported changes initiated by abstainers and reducers shortly after learning of pregnancy tended to be sustained through the weeks leading up to the first prenatal care appointment. Among the 24 abstainers, 17 (71%) initiated abstinence within the first two days after learning of pregnancy that was sustained uninterrupted through the first prenatal care visit. Among the 66 reducers, only 11 (17%) reported ever abstaining for one full day or more. Most of these reported only one quit attempt and these quit attempts had a median duration of four days (range, 1–37 days).

Discussion

The results of the present study reveal for the first time the time course of changes in smoking when women learn of pregnancy. The vast majority (84%) reported making substantive changes, usually within the first two days after learning of pregnancy, and largely sustaining these changes through their first prenatal care visit.

The results among abstainers are consistent with studies of professionally assisted quit attempts in pregnant and non-pregnant smokers where successful quitters usually initiate abstinence early in the quit attempt (Higgins et al., 2006; Kenford et al., 1994; Yudkin et al., 1996). The present results suggest that a similar pattern occurs among pregnant women who reduce their smoking. The similarities in the pattern of change among the abstainers and reducers is striking, with both groups reporting comparable, large reductions the first day after learning of pregnancy (7.5 and 5.9 cigarettes per day, respectively) and similar smaller reductions the second day (2.6 and 2.0 cigarettes per day, respectively). However, large differences in their pre-pregnancy smoking rate (12.3 vs. 18.8 cigarettes per day, respectively) mean that, despite parallel reductions shortly after learning of pregnancy, those who only reduced are still smoking an average of 7.6 cigarettes per day at their first prenatal care visit.

It is important to underscore the relationship between degree of change and socioeconomic status, with 58% of abstainers, 71% of reducers, and 94% of maintainers having completed 12 or fewer years of education. This observation further confirms the well-established relationship between low educational attainment and failure to quit smoking during pregnancy (e.g., Higgins et al., 2009; Solomon & Quinn, 2004) and extends it to whether women reduce or make no change in smoking upon learning of pregnancy. The relationship between maternal smoking and educational attainment is so pervasive and robust that it has been argued that tobacco control policies should be expanded to include efforts to impact more distal determinants of smoking like educational attainment in addition to more conventional and proximal determinants like tax rates, worksite smoking bans, and Medicaid coverage of smoking cessation services (Adams et al., 2012, 2013; Graham, 2009; Graham et al., 2006; Higgins et al., 2009; Kandel et al., 2009).

The time course of changes in smoking after learning of pregnancy characterized in the present study has implications for understanding possible mechanisms underpinning such change as well as the timing of smoking cessation interventions. The rapidity of the changes after learning of pregnancy suggests a behavioral or psychosocial mechanism likely involving a desire to protect the fetus and sensitivity to social expectations around smoking during pregnancy. Regarding implications for interventions, the present data indicate that women learned of pregnancy at 5 weeks gestation, the overwhelming majority of spontaneous changes that occurred took place by 6 weeks gestation, and the average first prenatal care visits occurred at 10 weeks gestation, meaning that on average 4 weeks passed without any additional change. It is possible that this initial motivation and momentum to change smoking could begin to wane during this delay. Smoking in the first trimester also impacts short and longer-term outcomes of the offspring including risk of congenital heart defects and orofacial clefts in infants (Alverson et al., 2011; Little et al., 2004; Malik et al., 2008) and adverse neurobehavioral outcomes (e.g., increased impulsivity, and delinquent, aggressive, and externalizing behaviors) and overweight in children (Cornelius et al., 2011; Mendez et al., 2008). Considered together, these data underscore the importance of intervening as early as possible with pregnant women who continue to smoke after learning of pregnancy.

The present study identified a group of women (16%) who failed to report making any positive changes in their smoking after learning of pregnancy. Whether 16% represents the prevalence of this group in the general population of smokers is unclear as the data were collected from a relatively small clinical sample. Determining the prevalence of this subsample in the general population and devising strategies to reach them earlier and to assist them with their smoking seems prudent.

A potential limitation of the present study is the reliability and validity of retrospective self-report, but use of TLFB has been shown in other populations to enhance the reliability and validity of self-reports of smoking and other substance use (Brown et al., 1998; Ehrman & Robbins, 1994; Sobell & Sobell, 1978; Toll et al., 2005). To avoid this potential limitation, a large prospective longitudinal observational study of non-pregnant female smokers of reproductive age could be conducted to see how smoking changes in the subset of women who become pregnant, but it does not seem likely that such a study will be conducted given the time, effort, and costs such a study would require. Another potential limitation of our use of self-report is stigma and other social pressures related to smoking during pregnancy can be expected to contribute to some extent of under-reporting of smoking rates, although these clearly did not prevent the majority of participants in the present study from reporting continued smoking and a sizeable percentage from reporting that they had not changed their smoking at all since learning of pregnancy. The possibility that stigma and social pressures may have also led women to report that they quit or reduced their smoking more quickly or more significantly than they actually did cannot be ruled out based on the present results.

In summary, to our knowledge, this is the first report examining the time course of changes in smoking in the interval between initially learning of pregnancy and beginning prenatal care. The majority of pregnant smokers who quit or made reductions in smoking after learning of pregnancy reported doing so soon after receiving the news. Further research is needed to replicate these findings and to determine whether devising strategies to identify and provide early interventions for women who continue smoking after learning of pregnancy are warranted.

Highlights.

The time course of changes in smoking upon learning of pregnancy are unclear.

Most women reported making changes in the first 2 days after learning of pregnancy.

The rapidity of the changes suggests a behavioral or psychosocial mechanism.

These results may suggest the need for earlier intervention among smoking women.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joan M. Skelly, M.S. for assistance with data analyses.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA14028, R01DA22491, and T32DA07242), National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD075669), National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20GM103644), and the Food and Drug Administration/National Institute on Drug Abuse (P50DA036114). None of the funding agencies had any involvement in the study design; in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict Of Interest

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams EK, Markowitz S, Kannan V, Dietz PM, Tong VT, Malarcher AM. Reducing prenatal smoking: the role of state policies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;43:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams EK, Markowitz S, Dietz PM, Tong VT. Expansion of Medicaid covered smoking cessation services: maternal smoking and birth outcomes. Medicare & Medicaid Research Review. 2013;3:E1–E22. doi: 10.5600/mmrr.003.03.a02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alverson CJ, Strickland MJ, Gilboa SM, Correa A. Maternal smoking and congenital heart defects in the Baltimore-Washington Infant Study. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e647–e653. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoola AB, Nettleman MD, Stommel M, Canady RB. Time of pregnancy recognition and prenatal care use: a population-based study in the United States. Birth. 2010;37:37–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2009.00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Burgess ES, Sales SD, Whiteley JA, Evans DM, Miller IW. Reliability and validity of a smoking timeline follow-back interview. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1998;12:101–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius MD, De Genna NM, Leech SL, Willford JA, Goldschmidt L, Day NL. Effects of prenatal cigarette smoke exposure on neurobehavioral outcomes in 10-year-old children of adolescent mothers. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2011;33:137–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crozier SR, Robinson SM, Borland SE, Godfrey KM, Cooper C, Inskip HM, SWS Study Group. Do women change their health behaviours in pregnancy? Findings from the Southampton Women’s Survey. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2009;23:446–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2009.01036.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dornelas EA, Magnavita J, Beazoglou T, Fischer EH, Oncken C, Lando H, Greene J, Barbagallo J, Stepnowski R, Gregonis E. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of a clinic-based counseling intervention tested in an ethnically diverse sample of pregnant smokers. Patient Education and Counseling. 2006;64:342–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrman RN, Robbins SJ. Reliability and validity of 6-month timeline reports of cocaine and heroin use in a methadone program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:843–850. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.4.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham H, Inskip HM, Francis B, Harman J. Pathways of disadvantage and smoking careers: evidence and policy implications. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2006;60(S2):7–12. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.045583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham H. Women and smoking: understanding socioeconomic influences. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;104(S1):S11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil SH, Higgins ST, Bernstein IM, Solomon LJ, Rogers RE, Thomas CS, Badger GJ, Lynch ME. Effects of voucher-based incentives on abstinence from cigarette smoking and fetal growth among pregnant women. Addiction. 2008;103:1009–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02237.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Heil SH, Solomon L, Plebani Lussier J, Abel R, Lynch ML, Badger GJ. A pilot study on voucher-based incentives to promote abstinence from cigarette smoking during pregnancy and postpartum. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:1015–20. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331324910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Heil SH, Dumeer AM, Thomas CS, Solomon LJ, Bernstein IM. Smoking status in the initial weeks of quitting as a predictor of smoking-cessation outcomes in pregnant women. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;85:138–41. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Heil SH, Badger GJ, Skelly JM, Solomon LJ, Bernstein IM. Educational disadvantage and cigarette smoking during pregnancy. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;104(S1):S100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Griesler PC, Schaffran C. Educational attainment and smoking among women: risk factors and consequences for offspring. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;104(S1):S24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenford SL, Fiore MC, Jorenby DE, Smith SS, Wetter D, Baker TB. Predicting smoking cessation. Who will quit with and without the nicotine patch. JAMA. 1994;271:589–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.8.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kost K, Landry DJ, Darroch JE. Predicting maternal behaviors during pregnancy: does intention status matter? Family Planning Perspectives. 1998;30:79–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little J, Cardy A, Arslan MT, Gilmour M, Mossey PA. Smoking and orofacial clefts: a United Kingdom-based case-control study. The Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal. 2004;41:381–386. doi: 10.1597/02-142.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik S, Cleves MA, Honein MA, Romitti PA, Botto LD, Yang S, Hobbs CA National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Maternal smoking and congenital heart defects. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e810–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez MA, Torrent M, Ferrer C, Ribas-Fitó N, Sunyer J. Maternal smoking very early in pregnancy is related to child overweight at age 5–7 y. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2008;87:1906–13. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nettleman MD, Brewer J, Stafford M. Scheduling the first prenatal care visit: office-based delays. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2010;203:e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirie PL, Lando H, Curry SJ, McBride CM, Grothaus LC. Tobacco, alcohol, and caffeine use and cessation in early pregnancy. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;18:54–61. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak KI, Oncken CA, Lipkus IM, Lyna P, Swamy GK, Petsch PK, Peterson BL, Heine RP, Brouwer RJ, Fish L, Myers ER. Nicotine replacement and behavioral therapy for smoking cessation in pregnancy. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigotti NA, Park ER, Regan S, Chang Y, Perry K, Loudin B, Quinn V. Efficacy of telephone counseling for pregnant smokers: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006;108:83–92. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000218100.05601.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Validity of self-reports in three populations of alcoholics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1978;46:901–907. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.5.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon L, Quinn V. Spontaneous quitting: self-initiated smoking cessation in early pregnancy. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6(Suppl 2):S203–S216. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001669132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toll BA, Cooney NL, McKee SA, O’Malley SS. Do daily interactive voice response reports of smoking behavior correspond with retrospective reports? Psychology Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:291–5. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Child Health USA 2010. Rockville, Maryland: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yudkin PL, Jones L, Lancaster T, Fowler GH. Which smokers are helped to give up smoking using transdermal nicotine patches? Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. British Journal of General Practice. 1996;46:145–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapka JG, Pbert L, Stoddard AM, Ockene JK, Goins KV, Bonollo D. Smoking cessation counseling with pregnant and postpartum women: a survey of community health center providers. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:78–84. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]