Abstract

A global HSV-1 gene repression occurs during latency in sensory neurons where most viral gene transcriptions are suppressed. The molecular mechanisms of gene silencing and how stress factors trigger the reactivation are not well understood. Thyroid hormones are known to be altered due to stress, and with its nuclear receptor impart transcriptional repression or activation depending upon the hormone level. Therefore we hypothesized that triiodothyronine (T3) treatment of infected differentiated neuron like cells would reduce the ability of HSV-1 to produce viral progeny compared to untreated infected cells. Previously we identified putative thyroid hormone receptor elements (TREs) within the promoter regions of HSV-1 thymidine kinase (TK) and other key genes. Searching for a human cell line that can model neuronal HSV-1 infection, we performed HSV-1 infection experiments on differentiated human neuroendocrine cells, LNCaP. Upon androgen deprivation these cells undergo complete differentiation and exhibit neuronal-like morphology and physiology. These cells were readily infected by our HSV-1 recombinant virus, expressing GFP and maintaining many processes iconic of dendritic morphology. Our results demonstrated that differentiated LNCaP cells produced suppressive effects on HSV-1 gene expression and replication compared to its undifferentiated counterpart and T3 treatment have further decreased the viral plaque counts compared to untreated cells. Upon washout of the T3 viral plaque counts were restored, indicating an increase of viral replication. The qRT-PCR experiments using primers for TK showed reduced expression under T3 treatment. ChIP assays using a panel of antibodies for H3 lysine 9 epigenetic marks showed increased repressive marks on the promoter regions of TK. In conclusion we have demonstrated a T3 mediated quiescent infection in differentiated LNCaP cells that has potential to mimic latent infection. In this HSV-1 infection model thyroid hormone treatment caused decreased viral replication, repressed TK expression and increased repressive histone tail marks on the TK promoter.

Keywords: gene regulation, herpes simplex virus type-1, histone methylation, neuronal cell, thymidine kinase, thyroid hormone receptor, neuronal differentiation

Introduction

HSV-1 has been found in 80% of US adults through serological testing (1). A number of studies have identified HSV-1 DNA in over 90% of adults that are 60 years of age and above (2-4). Interestingly many carry the virus yet the unsightly and painful oral lesions are not equally as prevalent. This phenomenon can be attributed to certain characteristics of the virus and complex host immune system virus interactions. One particular characteristic that herpes viruses including the ones that cause chicken pox, shingles, mono and several cancers, have developed methods persisting within its host undetected yet still able to spread to new hosts from time to time. For example, HSV establishes latency in sensory neurons and is characterized by the lack of viral replication and gene expression. Throughout the life of an infected host, events such as stress, local trauma, and surgery may trigger viral replication (5). Hormone fluctuations have been suggested to play a role in HSV reactivation (5) and is known to oscillate due to stress and regulates many cellular functions in neurons, we hypothesized that thyroid hormone may play a role to regulate HSV-1 replication and gene expression in differentiated neuronal environment.

Thyroxine (T4) and its physiologically active metabolite 3,5,3-triiodothyronine (T3) are collectively called thyroid hormones (TH). They are involved in a myriad of biological functions ranging from brain development and function to metabolism, immune system activation and cardiac rhythm (6). The mechanisms that drive these TH mediated biological events are extensively described, including the transcriptional regulation via nuclear TH receptor (TR) as well as the non-genomic TR effects modulating signaling pathways (7). The most well investigated transcriptional regulation by TR involves genes that are down regulated in the absence of TH and activated when TH is bound to TR, which binds to the promoter region of the regulated gene. In this type of regulation, TR binds promoter regions, as a homodimer or as a heterodimer with retinoid-X-receptor (RXR), at specific DNA sequences known as positive TR elements (pTREs) (8, 9). The most common form of pTREs is composed of a pair of six-nucleotide sequence AGGT(G/C)A with a four nucleotide long spacer, which is known as a direct repeat four (DR4) (10). In the absence of TH a TR dimer bound to a DR4 is in the appropriate conformation to interact with co-repressor complex, SMRT or NCoR and further recruit histone modifying enzymes that can remove active transcriptional marks, add repressive modifications to histone tails associated to the regulated gene and its promoter for transcriptional repression. Following TH binding to TR, TR undergoes a conformational change that ejects corepressor complexes and recruits co-activator complexes that include histone modifying enzymes that reverse the effects of the repressor complexes (11).

Like many biomolecules THs exhibit a feedback inhibition mechanism at several key steps within the TH synthetic signaling pathway. These mechanisms have also been shown to be mostly TH dependent negative regulation (11). The exact mechanisms involved in the negative regulation for the handful of genes during the feedback events have been studied for many years without much conclusion or consensus (12). For example, thyroid stimulating hormone gene α (TSHα) exhibits TH dependent transcription repression but the correlated negative TRE (nTRE) was poorly defined and showed different regulation pattern in different cellular environments (13-15). It has been shown that T3 can either positively or negatively regulate viral gene promoters such as Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) LTR (16-18) and Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV-1) Thymidine kinase (13, 19).

In the present study we focused on a key HSV-1 gene thymidine kinase (TK) since TK have been previously reported to be important during HSV-1 reactivation (20-23) and novel TREs were identified within the TK promoter region between TATA box and transcription initiation site (13, 19, 24). We postulate that under neuronal cell conditions thyroid hormone can suppress HSV replication and removal of thyroid hormone can rescue viral replication, through a thymidine kinase regulation. In order to test this hypothesis in vitro, experiments in neuron like differentiated LNCaP cells treated with various thyroid hormone conditions were analyzed to investigate the effects on viral replication, regulation of TK transcription, and epigenetic modification of the TK promoter.

Results

Neuronal characterization of differentiated LNCaP cells

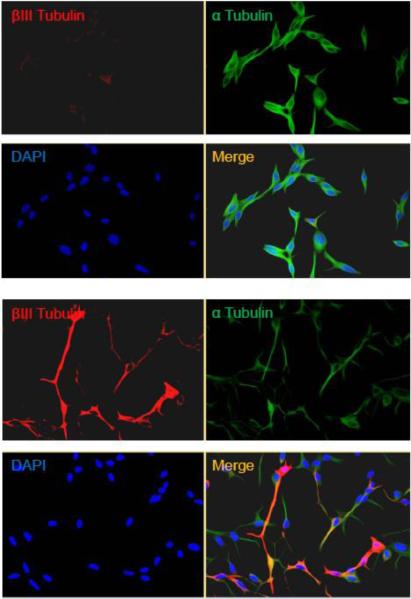

Upon androgen deprivation, LNCaP cells undergo differentiation and exhibited long neurite-like morphology and neuronal physiology such as differentiation-specific ionic conductances, neuron-specific marker enolase (NSE), and the secretion of mitogenic neuropeptides neurotensin (25-28). To confirm this observation, immunofluorescent assays using neuron specific anti- β III Tubulin antibody were performed to compare the presence of neuronal marker (29, 30) in undifferentiated and differentiated LNCaP cells. The results clearly demonstrated that β III Tubulin was abundantly present in differentiated condition coexisted with α-Tubulin, which was present in both undifferentiated and differentiated states (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Differentiation of LNCaP cells and viral infection.

A. Undifferentiated LNCaP cells were compared to differentiated ones by immuno-fluorescent microscopy using neuronal maker β-Tubulin (red) and control α-Tubulin (green). It is noted that differentiated LNCaP cells undergo morphological changes with expression of β-Tubulin.

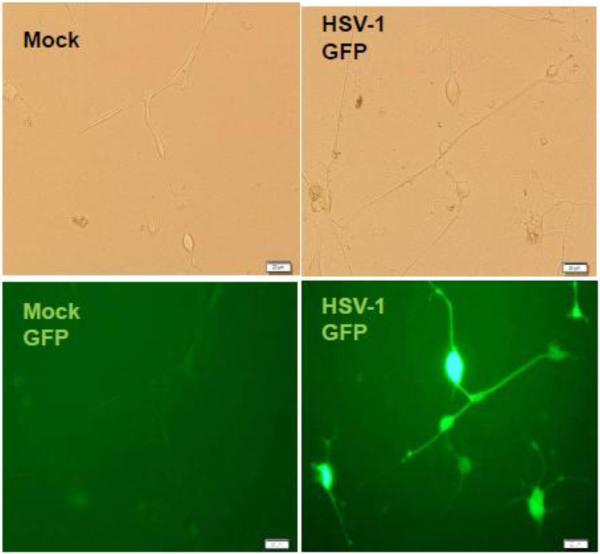

B. Differentiated cells were infected by recombinant HSV-1 expression GFP. It can be seen that infected cells expressed fluorescence and can survive a week at moi of 1.

Differentiated LNCaP can be infected by HSV-1

The infectivity of the differentiated LNCaP cells was tested by HSV-1/GFP monitored by fluorescent microscopy. The moi was determined empirically and the results showed that the infected differentiated cells can survive a week at moi of 1 (Fig. 1B). In the presence of T3, the infected cells can survive as long as three weeks with fluorescence expression. At this moi, the undifferentiated cells died in 24 hpi regardless the status of T3 (data not shown), indicating the importance of differentiation.

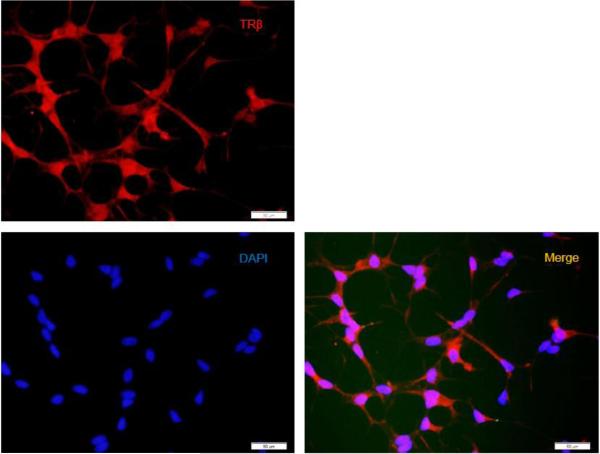

TRβ1 is present in differentiated LNCaP cells

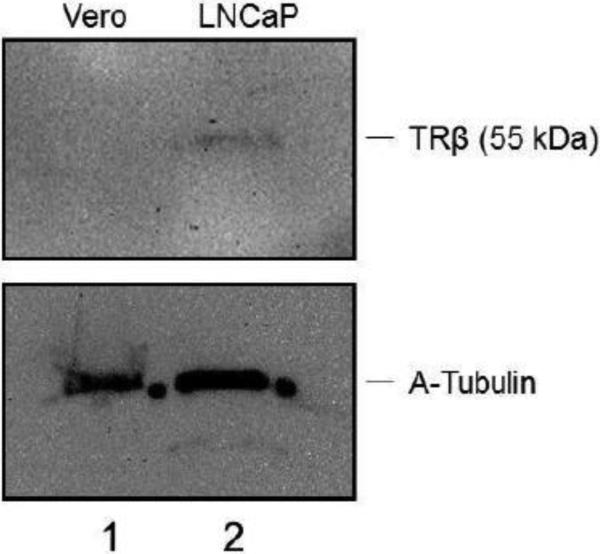

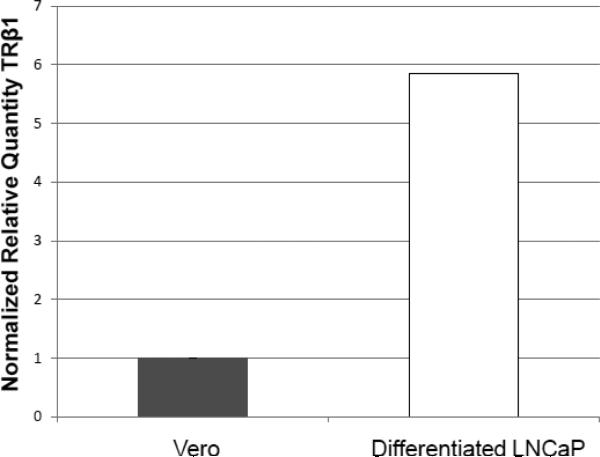

The presence of TRβ1 was examined by Western blot and qRT-PCR analyses. It can be seen that TRβ is expressed in differentiated LNCaP cells but not in Vero cells (Fig. 2A). The quantitative RT-PCR assays indicated that the TRβ level in LNCaP cells exhibited approximately a 6-fold increase compared to Vero cells (Fig. 2B). In addition, the immuno-fluorescent microscopy indicated that TRβ was expressed throughout the differentiated cells both in nuclei and the cytoplasm (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2. Expression of TRβ1 1 in LNCaP cells.

A. Western blot analyses were performed to investigate the expression of TRβ1 in Vero (Lane 1) and LNCaP cells (Lane 2). TRβ1 was detected in LNCaP but not Vero cells.

B. The level of TRβ1 expression was compared by qRT-PCR analyses. It was shown that LNCaP had approximately 6-fold more expression of TRβ compared to Vero cells.

C. TRβ expression was analyzed by immuno-fluorescent microscopy. The protein can be seen in nuclei as well as cytoplasm.

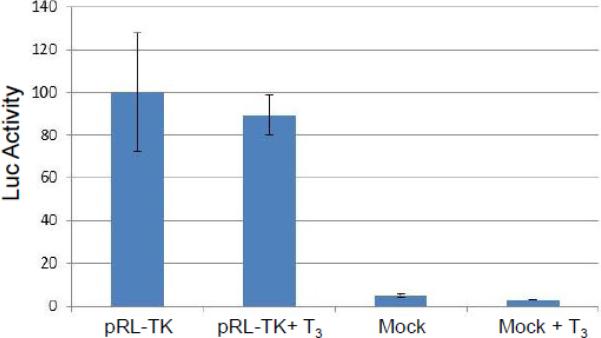

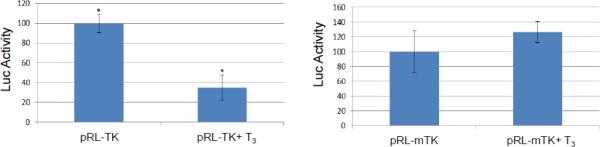

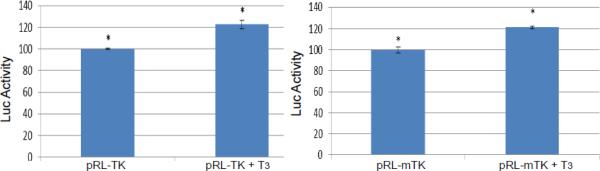

HSV-1 TK is repressed by T3 only when the cells were differentiated

Transient transfection was performed to examine the T3-mediated regulation in different cells. A control experiment showed that TK transcription was not affected by T3 in Vero cells (Fig. 3A). In differentiated LNCaP cells, TK promoter activity was decreased to 40% by T3 and this repression required intact TRE since TK TRE mutation abolished this regulation (Fig. 3B). In addition, there is no T3-mediated repression on TK if the cells were undifferentiated (Fig. 3C). Together these results indicated that T3-dependent TK repression requires the binding of TR to the TK TRE and an environment of differentiation is necessary.

Fig. 3. Regulation profile of TK by T3 in Vero, undifferentiated, and differentiated LNCaP cells.

A. Transient transfection of Vero cells with pRL-TK showed no regulation mediated by T3.

B. TK promoter activity was reduced to 40% by T3. Promoter with mutated TRE was not affected in differentiated LNCaP cells.

C. TK promoter activity was not repressed by T3 if the LNCaP cells were undifferentiated.

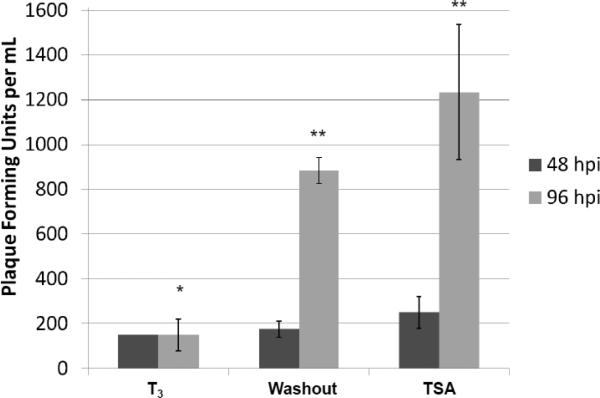

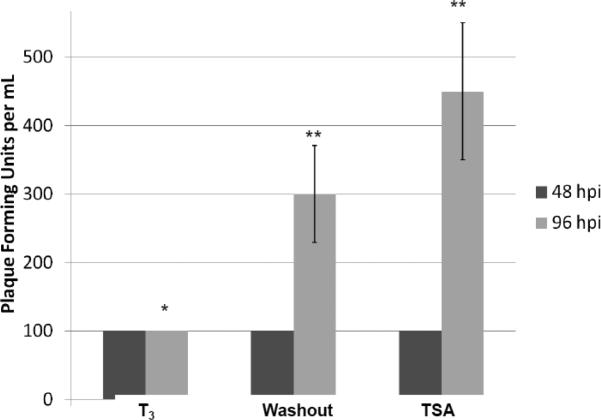

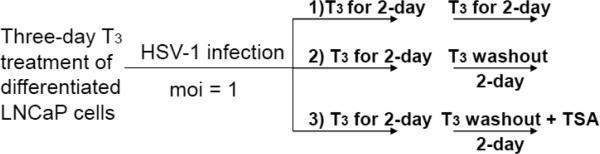

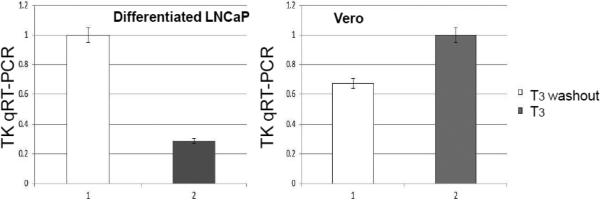

In vitro differentiated cell culture reactivation model to test the effects of T3 on viral replication

We have developed a cell culture model in which the cells can be differentiated, infected, and maintained under the described culture situation for as long as two weeks (Materials and Methods). In summary, the differentiated cells were treated with T3 for two days followed by infection at moi of 1 in the presence of T3 for 48 hours. At the end of 48 hpi, the T3 was either removed from the culture (Condition 2) or continued to be added to the media of infected cells (Condition 1) for another 48 hours. At the 96 hpi media were collected for plaque assays and the infected cells were subjected to RNA purification and qRT-PCR to assess the viral gene expression (Fig. 4A). Trichostatin A (TSA), a histone deacetylase inhibitor, was used as a positive control of viral reactivation (Condition 3).

Fig. 4. T3 mediated HSV-1 replication in differentiated cells.

A. Scheme of in vitro reactivation model mediated by T3. In short, differentiated cells were pretreated with T3 followed by infection in the presence of T3 for two days. At the end of the 2-day treatment the infected cells were either treated with T3 or cultured in media without T3 (Washout). Trichostatin A (TSA) was used as a reactivation control.

B. The media of infected cells were collected 48 and 96 h p.i. followed by plaque assays using Vero cells to investigate the release of infectious viruses. * denotes significant statistical difference with p value <0.005. ** no significant statistical difference.

C. The crude lysates of infected cells collected at 48 and 96 h p.i. were subjected to plaque assays to analyze the amount of virion produced within the cells but not released. * denotes significant statistical difference with p value <0.005. ** no significant statistical difference.

Our plaque assays results using media indicated that the release of the infectious viruses was low and similar across these three conditions at the 48 hpi while the T3 is present. At 96 hpi, T3 treatment continued to repress the replication but hormone washout significantly reversed the T3-mediated inhibition by at least 6-fold (Fig. 4B). TSA exhibited very strong reactivation by increasing the infectious virus release (8-fold) (Fig. 4B). Plaque assays using crude cell lysate showed similar results that T3 washout and TSA relieved the T3-mediated suppression by 3-fold and 4.5-fold, respectively (Fig. 4C). This T3-dependent regulation of viral replication was not observed in undifferentiated cells (data not shown). These observations collectively indicated that T3 is suppressive to HSV-1 replication when the cells were differentiated and this repression was reversible.

T3-mediated repression of HSV-1 TK can be reversed after T3 washout during infection of differentiated cells

The HSV-1 TK regulation by T3 was tested by this in vitro cell culture model. After collecting the media for plaque assays, the cells were subjected to RNA isolation followed by qRTPCR. It is shown that in differentiated condition, T3 washout exhibited a 3.4-fold increase of TK activity compared to the T3 treated group (Fig. 5A). This T3-mediated repression was not seen in Vero cells (Fig. 5A) and undifferentiated LNCaP (data not shown), indicating that T3- mediated TK regulation required differentiation.

Fig. 5. Effects of T3 and recruitment of TR on TK regulation during infection.

A. Cells (undifferentiated Vero and differentiated LNCaP) were treated and infected as described in Fig. 4. The RNA of infected cells was subjected to qRTPCR analyses using primers against HSV-1 TK. The GFP specific primers were used as internal control.

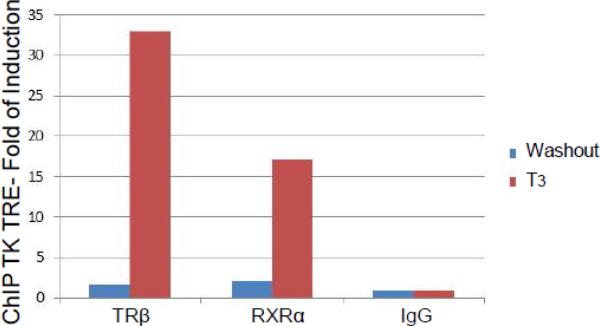

B. Chromatin immuno-precipitation (ChIP) was performed using TRβ and RXRα Ab in the presence of T3 or washout under the same condition described in Fig. 5A. A non-immune IgG was used as negative control.

The presence of T3 facilitated the recruitment of TRβ/RXRαto the TK TRE

The occupancy of TRβ/RXRα was first investigated by chromatin immuno-precipitation (ChIP) using antibodies against TRβ and RXRα in the presence of T3 or washout condition. The results indicated that the occupancy of both TRβ and RXRα decreased drastically after the T3 washout (Fig. 5B), suggesting that TRβ and RXRα were recruited at the TK TRE when T3 was available and the removal of T3 abolished the enrichment of nuclear receptor.

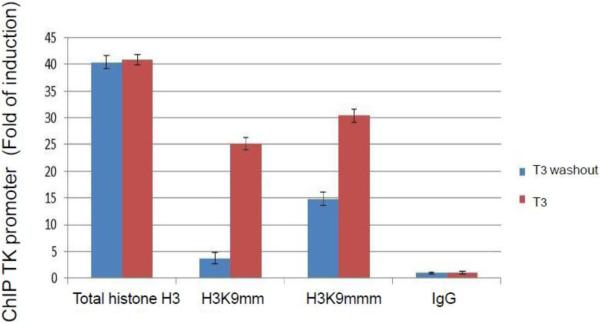

Participation of histone methylation in the T3-mediated regulation of HSV-1 gene expression and replication in differentiated cells

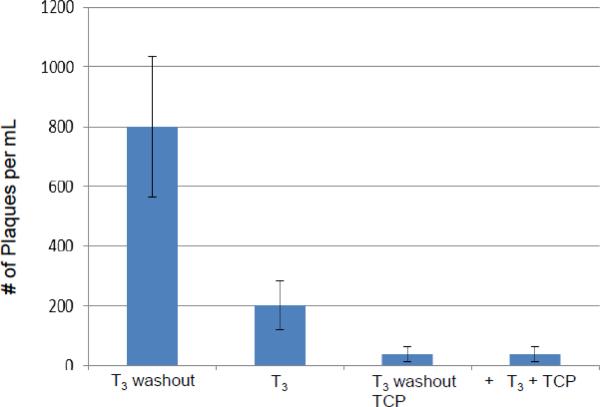

Histone methylation was suggested to play a role in regulating HSV-1 latency and reactivation (31, 32). In addition, T3 has been reported to exert gene regulation via negative TRE in neuroblastoma cells through modulating histone methylation (15, 33). Therefore we hypothesized histone methylation played a role in the T3-mediated regulation of viral replication and gene expression. To test the hypothesis, we performed the experiments using our in vitro differentiated cell culture reactivation model with trans-2-phenyl-Cyclopropylamine hydrochloride (TCP), a histone demethylase inhibitor (34). Under the treatment of TCP, the histones inside the cells remained hypermethylated. Our results showed that TCP abolished the reactivation mediated by T3 washout (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6. Role of histone methylation on HSV-1 replication and gene regulation in differentiated cells upon T3 treatment.

A. Infections were performed as described in Fig. 4A with treatment of TCP followed by plaque assays. It can be seen that TCP exerted additional repression on the viral replication and eliminated the activation upon T3 washout.

B. Histone methylation profile was analyzed at the HSV-1 TK promoter by ChIP using Ab against H3K9me2 and H3K9me3, both are repressive chromatin. It appears that T3 washout decreased the enrichment. Pre-immune IgG was used as negative control.

ChIP was performed to investigate the histone methylation profile at the HSV-1 TK promoter during the changes of hormonal status. At first we focused on two repressive methylated chromatins, di-methyl histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me2) and tri-methyl histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9me3), since they are enriched at the silent domains of euchromatin or recruited within the pericentric heterochromatin, respectively (35, 36). Our results indicated that they were both detected at the TK TRE in the presence of T3 and the washout decreased the enrichment (Fig. 6B), suggesting that histone methylation contributed, at least in part, to this hormone dependent regulation.

Discussion

Immense efforts have been attempted to develop a cell culture model for studies of HSV latency. An ideal model using human cell lines should have two traits: a quiescent state of viral infection and a fully differentiated status with neuronal physiological aspects. A good cell culture-based model would provide a readily available platform to address important questions at the molecular level and it is easy to control the parameter by adding it into media. It is helpful to propose evidence-based hypothesis before moving into the animal models for physiological investigation.

Previously we demonstrated that HSV-1 gene expression and replication were controlled by TR and T3 using mouse neuroblastoma cell lines N2a. It exhibited good TR/T3-meidated regulation. In short, we demonstrated that T3 exerted positive regulation on LAT but negative regulation on TK using various epigenetic mechanisms. However these mouse cells were partially differentiated. The present investigation is focusing on using fully-differentiated human LNCaP cells as a platform for studying the effects of T3 on HSV-1 latency and reactivation. Differentiation of LNCaP cells express nuclear receptor TRβ1 and feature typical neuronal morphology, for example, the development of long neurite-like processes, rounding of the cell body, the presence of secretory granules. In addition, physiological markers were also observed including the expression of chromogranin-A, differentiation-specific ionic conductances and markers like neuron-specific enolase (NSE), and the secretion of mitogenic neuropeptides such as neurotensin and parathyroid hormone-related peptide (27, 28, 37, 38). Using this model, we showed that HSV-1 infection in undifferentiated LNCaP was very efficient and differentiation somehow decelerated the viral replication. Additional studies indicated that a combination of differentiation and T3 was effectively suppressing, if not completely inhibiting, the viral gene expression and replication for as many as three weeks. T3 was shown to interact with αVβ3 integrin (39) and this integrin was known to influence HSV-1 entry (40, 41). Our control experiments demonstrated that T3 did not affect entry (supplemental Fig. 1) and T3 alone was not sufficient to repress the viral replication if cells were undifferentiated (unpublished data), suggesting the importance of neuronal differentiation in the regulation of viral latency and reactivation.

The roles of TK in neurons during HSV-1 reactivation are debatable. Literature signpost TK expression occurred after α genes during lytic infection. In the midst of reactivation, TK transcription was initiated around the same time as the other α genes using TG explant assays so it is not a prerequisite for during reactivation (42). However, other studies showed that TK is necessary for viral replication in resting cells such as neurons since TK provides dNTP and viral replication is crucial for efficient α and β expressions during reactivation (20). Independent observation revealed TK was critical to instigate α transcription and ensuing replication during reactivation, quite different in comparison to lytic infection (43). In addition, TK was one of the first genes to be expressed during in vivo reactivation in TG (21) and TK-mutant displayed significantly decreased α and β expression during reactivation (22). According to these results, TK appeared to play an important role during viral reactivation.

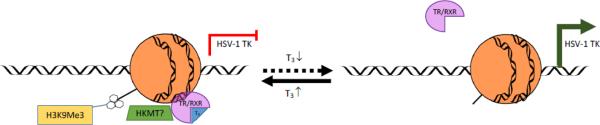

TK TREs exhibited novel characteristics (19). The promoter comprises TRE palindrome repeats with six-nucleotide in the middle separating them. These TREs are positioned between the TK TATA box and the transcription initiation site, a context was suggested to behave in negative manner, as ligand-bound TR exerted repression and unbound TR reversed the inhibition, in neural cells (13, 19). In neural cells without differentiation, the TK promoter activity was increased by the addition of T3 during transfection (44). Our results also showed that TK transcription was slightly increased in the presence of T3 and TR even when one of the TRE had single-nucleotide mutation in undifferentiated cells (Fig. 3C). Infection studies indicated that TK transcription was up-regulated in the presence of T3 and TR when the cells were undifferentiated (Fig. 5A). These observations suggested that in undifferentiated condition the TR/T3 exerted a positive regulation at the TK TRE. On the other hand, fully differentiated neuroendocrine cells exhibited significant repression on TK in the presence of T3 by transfection and infection (Fig. 3B and 5A, respectively). Collectively these observations suggested this novel T3-mediated repression required neuronal differentiation and the presence of TR. Host factors expressed during differentiation as well as neuronal chromatin configuration may participate in this TR/T3-dependent regulation. A schematic representation depicting the proposed mechanism was shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. Proposed model for T3/TR-mediated TK regulation.

In the presence of T3, ligand-bound TR/RXR bound to the TK TREs and induced the enrichment of repressive chromatin H3K9me3 and H3K9me2, leading to transcription repression. When the T3 level dropped, TR/RXR was released from the TREs and the repressive chromatin was switched to active chromatin. This conversion allowed the access of transcription complex to the promoter for transcription activation.

The occupancy of TR and/or RXR at the TK TRE was analyzed by different methods. In vitro electro-mobility shift assays (EMSA) using purified proteins showed that TR or TR/RXR bound to the TK TREs regardless the status of T3 (Supplemental Fig. 2). In addition, RXR alone did not have the capacity to interact with the TK TREs. Our in vivo ChIP assays, on the contrary, indicated that TR and RXR were enriched at the TK promoter while T3 was available and T3 washout abolished their occupancy (Fig. 5B). This is in agreement with our previous findings that only ligand-bound TR/RXR was recruited to the TK TREs using a partially differentiated mouse neuroblastoma cell line (19). It is of interest to learn that unbound TR lost its binding capacity to negative TREs probably due to involvement of host factors and this may participate in the regulation of viral gene expression as well as replication.

Present study provided results supporting our hypotheses that T3 participated in the regulation of HSV-1 TK gene expression and viral replication in differentiated LNCaP, a human neuroendocrine cell culture model. T3-mediated regulation was also investigated on other viral genes such as Latency Associate Transcript (LAT) and ICP0 since positive TREs were found at the regulatory regions of (45). Our observation revealed that during infection LAT was significantly increased and ICP0 was decreased by T3, supporting the bioinformatics prediction and the status similar to latency. The molecular mechanisms are being investigated. The importance of TR during T3-dependent viral reactivation was further addressed in other human differentiated neuroblastoma cell lines. Our observation was that LNCaP cells, while differentiated, was very suppressive, if not completely inhibitory, compared to other differentiated neuroblastoma cell lines in the presence of T3. These findings, although not fully understood, emphasized the uniqueness of LNCaP and its future value as a tool for latency studies. It is noted that this cell line, under current condition without acyclovir treatment, does not represent a bona fide viral latency state since we can still detect small amount of viral replication. However, it still represents an effective and convenient model to investigate T3/TR regulatory effects in differentiated condition.

Materials and Methods

Viruses, cell lines, and culture conditions

HSV-1 EGFP virus based on strain 17-Syn+ was used for infection (19, 46). This recombinant HSV-1 strain 17Syn+ expresses engineered enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the human cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene promoter inserted in the place of the gK gene (46). LNCaP is a human prostate cancer cell line purchased from ATCC (Cat#: CRL-1740) and were grown in RPMI -1640 supplemented with 10% FBS. Vero cells (ATCC Cat#: CCL-81) were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were grown and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a cell culture incubator.

Neuroendocrine differentiation (NED) induction

Proliferating LNCaP cells were harvested from culture flasks using phenol red-free 0.025% Trypsin-EDTA. The cells were then pelleted and re-suspended with phenol red-free RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% charcoal dextran treated FBS. The cells were seeded onto culture dishes at 4.0×103 cells per cm2 of culture dish growth area. These conditions were maintained for at least 5 days before being treated further.

Western Blotting

The protocol was described previously (19, 47). In short, cell extract was subjected to gel electrophoresis and transferred by iBlot® Gel Transfer Device (Life Technology, Cat#: IB1001). Anti-TRβ1 mouse monoclonal antibody (Cat#: MA1-215, Thermo-Fisher) was used at a dilution of 1:1,000 for detection. Anti-α-Tubulin mouse antibody (Calbiochem, Cat#: CP06, San Diego, CA) was added at a dilution of 1:10,000 as control. The chemiluminescent signal from the membranes was subjected to detection by Bio-Rad Chemi-docl XRS imaging systems (Hercules, CA).

Transfection and plasmids

Plasmids pRL-TK (Cat#: E2241, Promega) and the generation of pRL-mTK used in this study were essentially described previously (19). Plasmid pFL-VP16, a gift from Dr. David Davido (University of Kansas Lawrence), contains a firefly luciferase reporter under the control of HSV-1 VP16 promoter (48). The transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Cat#: 11668-027, Life Technology) following the protocol provided by the manufacturer.

Reporter assays

The cell lysate was collected for the luciferase assay after 48 hr of transfection essentially described by the manufacturer. Luciferase activity was measured by a luminometer using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega). Luminescence was measured over a 10-sec interval with a 2-sec delay on the 20/20n Luminometer (Turner Biosystem, Sunnyvale, CA). The renilla luciferase activities were normalized against the internal firefly luciferase control driven by VP16 to correct for transfection efficiency. The results were presented as the percent induction of the reporter plasmid in the presence or absence of T3 (100 nM).

T3 removal assays

On Day 7 post NED of LNCaP cells, 2 portions of the cells were treated with 100 nM T3 (+T3) and the T3 washout condition (w/o). A third portion served as the –T3 control. At 48 hours after T3 treatment the cells were exposed to EGFP HSV-1 at moi of 1 for 1 hour. The inoculum was then removed and the cells were washed twice with 1 ml of PBS followed by the addition of 1 ml of fresh media containing the respective amounts of T3. Every 24 hours post infection (hpi) fluorescent microscopy observations were made and supernatant samples were collected for plaque assays. At 48 hpi the media of the w/o condition were removed and the cells were washed with PBS and treated with T3 free differentiation media. At 96 hpi the conditions were prepared for analysis via chromatin imunooprecipitation-quantitative PCR and/or quantitative reverse transcription PCR. The scheme was described in Fig. 4A.

Plaque Assay

Vero cells were plated using 24 well plates at 2.0×105cells/ml twenty four hours before the experiment. Growth medium was removed, and supernatant collected from LNCaP infection experiments were serially diluted in growth medium that had been added to the plate. Plates were incubated for 48 hours then were fixed with methanol followed by staining with crystal violet and plaques were counted. Data in triplicates were analyzed by ANOVA and differences were found to be statistically different were marked with p<0.05.

Fluorescent Microscopy

Cells approximately 20,000/plate were placed in a multi-chamber slide (Cat# 354104, BD Falcon) a day before infection. Infected cells were washed once with 2 ml PBS for 5 min and fixed with 100% methanol at −20°C. Slides were incubated with 2% normal blocking serum followed by incubation with primary antibody for β Tubulin (Cat#: ab18267, Abcam), α Tubulin (Cat#: CP06, Calbiochem) overnight at 4°C. The slides were then incubated with fluorescent conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen cat# A21424) at RT for 1 hr. The slides were last mounted with fluorescent mounting medium containing DAPI. The expression of enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP), red fluorescence, and DAPI staining were accessed by an Olympus fluorescence microscope (IX71) coupled with an Olympus digital camera photo apparatus (DP71). Imaging analysis was performed by using Olympus DP controller software. Exposure time between treatments was equivalent among different samples.

ChIP

The ChIP was performed using ChromaFlash High-Sensitivity ChIP Kit (Cat#: P-2027-48, Epigentek, Farmingdale, NY). The protocol was essentially described according to the manufacturer. In short, Test antibodies were first bound to Assay Strip Wells as well as Anti-RNA polymerase II (positive control) and non-immune IgG (negative control). The cells were subjected to cross-linking by adding media containing formaldehyde to a final concentration of 1% with incubation at room temperature (20-25°C) for 10 min on a rocking platform (50-100 rpm). Glycine (1.25 M) was to the cross-link solution (1:10). After appropriate mixing and ice-cold PBS washing and centrifuging, Working Lysis Buffer was added to re-suspend the cell pellet and incubate on ice for 10 min. After carefully removing the supernatant, ChIP Buffer CB was added to re-suspend the chromatin pellet. Shear chromatin using Waterbath Sonication (EpiSonic 1100 Station, Cat No. EQC-1100, Epigentek). The program was set up at 20 cycles of shearing under cooling condition with 15 seconds On and 30 seconds Off, each at 170-190 watts. ChIP samples were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4°C for 10 min after shearing and transferred supernatant to a new vial. Next Set up the reactions by adding the ChIP samples to the wells that are bound with test antibodies, positive control, or negative control. The reaction incubation condition was 4°C overnight. ChIP samples then were washed according to the protocol and subjected to reverse cross-linking at at 60°C for 45 min. Finally the DNA samples were purified by spin column for quantitative PCR (qPCR). The antibodies used were: anti-TRβ1 (Cat#: MA1-215, Thermo-Fisher), anti-RXRα (Cat#: ab41934, Abcam), anti-Histone H3 di-methylated K9 (Cat#: ab1220, Abcam), anti-Histone h3 tri-mehylated K9 ( Cat#: ab8898, Abcam).

ChIP-qPCR and q-RT-PCR

Quantitative analyses of ChIP and gene expression were performed by qPCR and qRTPCR respectively using myiQ SYBR green supermix and iScript One-Step RT-PCR kits (BIO-RAD). Experiments were performed in triplicate with one set of primers per reaction. The primer sequences for RTPCR are as follows: GFP: 5′-GCA GAA GAA CGG CAT CAA GGT G-3′ and 5′-TGG GTG CTC AGG TAG TGG TTG TC-3′; PGK1: 5′-ACC TGC TGG CTGG ATG GGC TT-3′ and 5′-GCT TAG CCC GAG TGA CAG CCT C-3′; PPIA: 5′-AGC ATA CGG GTC CTG GCA TCT-3′ and 5′-CAT GCT TGC CAT CCA ACC ACT CA-3′ (49); TRβ1: 5’-TTC CAA ACG GAG GAG AAG AA-3’ and 5’-TAG TGA TAC CCG GTG GCT TT-3’; TK: 5’-GCA CGT CTT TAT CCT GGA TTA CG-3’ and 5’-TGG ACC ATC CCG GAG GTA AG-3’ and the Taqman probe sequence is 5’- /56-FAM/CCG GGA CGC CCT GCT GCA /3BHQ_1/-3’. The ChIP primer sequences for TK TRE are 5’-ATG GCT TCG TAC CCC TGC CAT-3’ and 5’-GGT ATC GCG CGG CCG GGT A’3’. The qPCR reactions were carried out at 94°C for 3min, followed by 35 repeats of 94°C for 15s, 69°C for 15s, and 72°C for 15s. The qRTPCR reactions were carried out at 45°C for 10 minutes, 94°C for 2min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 15s, 69°C for 15s, and 72°C for 15s.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHT.

A neuronal maker was detected in differentiated LNCaP cells but not in undifferentiated cells.

Differentiated cells are infected by HSV-1 but the replication is reduced in the presence of T3.

Transfection and infection assays confirmed the T3/TR-mediated regulation on HSV-1 TK promoter.

Repressive chromatins were enriched at the promoter when T3 is present and washout released them.

T3 removal increased viral replication in differentiated cells, not if cells undifferentiated.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. David Davido for the VP16 reporter plasmid. This project is supported by R01NS081109 to SVH from NIH and the content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NINDS/NIH. The authors appreciate the assistance of the editorial staff at UMES.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Whitley RJ, Kimberlin DW, Roizman B. Herpes simplex viruses. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:541–53. doi: 10.1086/514600. quiz 54-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liedtke W, Opalka B, Zimmermann CW, Lignitz E. Age distribution of latent herpes simplex virus 1 and varicella-zoster virus genome in human nervous tissue. J Neurol Sci. 1993;116:6–11. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(93)90082-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker Y. HSV-1 brain infection by the olfactory nerve route and virus latency and reactivation may cause learning and behavioral deficiencies and violence in children and adults: a point of view. Virus Genes. 1995;10:217–26. doi: 10.1007/BF01701811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill JM, Ball MJ, Neumann DM, Azcuy AM, Bhattacharjee PS, Bouhanik S, Clement C, Lukiw WJ, Foster TP, Kumar M, Kaufman HE, Thompson HW. The high prevalence of herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA in human trigeminal ganglia is not a function of age or gender. J Virol. 2008;82:8230–4. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00686-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsia SC, Bedadala GR, Balish MD. Effects of thyroid hormone on HSV-1 gene regulation: implications in the control of viral latency and reactivation. Cell Biosci. 2011;1:24. doi: 10.1186/2045-3701-1-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lazar MA. Thyroid hormone action: a binding contract. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:497–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI19479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis PJ, Lin HY, Mousa SA, Luidens MK, Hercbergs AA, Wehling M, Davis FB. Overlapping nongenomic and genomic actions of thyroid hormone and steroids. Steroids. 2011;76:829–33. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazar MA. Thyroid hormone receptors: multiple forms, multiple possibilities. Endocr Rev. 1993;14:184–93. doi: 10.1210/edrv-14-2-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lazar MA, Chin WW. Nuclear thyroid hormone receptors. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:1777–82. doi: 10.1172/JCI114906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Velasco LF, Togashi M, Walfish PG, Pessanha RP, Moura FN, Barra GB, Nguyen P, Rebong R, Yuan C, Simeoni LA, Ribeiro RC, Baxter JD, Webb P, Neves FA. Thyroid hormone response element organization dictates the composition of active receptor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12458–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610700200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramadoss P, Abraham BJ, Tsai L, Zhou Y, Costa ESRH, Ye F, Bilban M, Zhao K, Hollenberg AN. Novel mechanism of positive versus negative regulation by thyroid hormone receptor beta 1 (TRbeta1) identified by genome-wide profiling of binding sites in mouse liver. J Biol Chem. 2013 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.521450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yap CS, Sinha RA, Ota S, Katsuki M, Yen PM. Thyroid hormone negatively regulates CDX2 and SOAT2 mRNA expression via induction of miRNA-181d in hepatic cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;440:635–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.09.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park HY, Davidson D, Raaka BM, Samuels HH. The herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene promoter contains a novel thyroid hormone response element. Molecular Endocrinology. 1993;7:319–30. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.3.8387156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatterjee VK, Lee JK, Rentoumis A, Jameson JL. Negative regulation of the thyroid-stimulating hormone alpha gene by thyroid hormone: receptor interaction adjacent to the TATA box. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:9114–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong W, Li J, Wang B, Chen L, Niu W, Yao Z, Baniahmad A. Epigenetic involvement of Alien/ESET complex in thyroid hormone-mediated repression of E2F1 gene expression and cell proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;415:650–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.10.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsia SC, Shi YB. Chromatin disruption and histone acetylation in regulation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat by thyroid hormone receptor. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:4043–52. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.12.4043-4052.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahman A, Esmaili A, Saatcioglu F. A unique thyroid hormone response element in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat that overlaps the Sp1 binding sites. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:31059–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desai-Yajnik V, Hadzic E, Modlinger P, Malhotra S, Gechlik G, Samuels HH. Interactions of thyroid hormone receptor with the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) long terminal repeat and the HIV-1 Tat transactivator. J Virol. 1995;69:5103–12. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.5103-5112.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsia SC, Pinnoji RC, Bedadala GR, Hill JM, Palem JR. Regulation of herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase gene expression by thyroid hormone receptor in cultured neuronal cells. J Neurovirol. 2010;16:13–24. doi: 10.3109/13550280903552412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nichol PF, Chang JY, Johnson EM, Jr., Olivo PD. Herpes simplex virus gene expression in neurons: viral DNA synthesis is a critical regulatory event in the branch point between the lytic and latent pathways. Journal of Virology. 1996;70:5476–86. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5476-5486.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tal-Singer R, Lasner TM, Podrzucki W, Skokotas A, Leary JJ, Berger SL, Fraser NW. Gene expression during reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 from latency in the peripheral nervous system is different from that during lytic infection of tissue cultures. J Virol. 1997;71:5268–76. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5268-5276.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kosz-Vnenchak M, Jacobson J, Coen DM, Knipe DM. Evidence for a novel regulatory pathway for herpes simplex virus gene expression in trigeminal ganglion neurons. J Virol. 1993;67:5383–93. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5383-5393.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coen DM, Kosz-Vnenchak M, Jacobson JG, Leib DA, Bogard CL, Schaffer PA, Tyler KL, Knipe DM. Thymidine kinase-negative herpes simplex virus mutants establish latency in mouse trigeminal ganglia but do not reactivate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:4736–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.12.4736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wagner MJ, Sharp JA, Summers WC. Nucleotide sequence of the thymidine kinase gene of herpes simplex virus type 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:1441–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.3.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bang YJ, Pirnia F, Fang WG, Kang WK, Sartor O, Whitesell L, Ha MJ, Tsokos M, Sheahan MD, Nguyen P, Niklinski WT, Myers CE, Trepel JB. Terminal neuroendocrine differentiation of human prostate carcinoma cells in response to increased intracellular cyclic AMP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:5330–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cox ME, Deeble PD, Lakhani S, Parsons SJ. Acquisition of neuroendocrine characteristics by prostate tumor cells is reversible: implications for prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3821–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mariot P, Vanoverberghe K, Lalevee N, Rossier MF, Prevarskaya N. Overexpression of an alpha 1H (Cav3.2) T-type calcium channel during neuroendocrine differentiation of human prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10824–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108754200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prevarskaya N, Skryma R, Bidaux G, Flourakis M, Shuba Y. Ion channels in death and differentiation of prostate cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1295–304. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheikh MA, Malik YS, Yu H, Lai M, Wang X, Zhu X. Epigenetic regulation of Dpp6 expression by Dnmt3b and its novel role in the inhibition of RA induced neuronal differentiation of P19 cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pedroni SM, Gonzalez JM, Wade J, Jansen MA, Serio A, Marshall I, Lennen RJ, Girardi G. Complement inhibition and statins prevent fetal brain cortical abnormalities in a mouse model of preterm birth. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:107–15. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang Y, Quenelle D, Vogel JL, Mascaro C, Ortega A, Kristie TM. A novel selective LSD1/KDM1A inhibitor epigenetically blocks herpes simplex virus lytic replication and reactivation from latency. MBio. 2013;4:e00558–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00558-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liang Y, Vogel JL, Narayanan A, Peng H, Kristie TM. Inhibition of the histone demethylase LSD1 blocks alpha-herpesvirus lytic replication and reactivation from latency. Nat Med. 2009;15:1312–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belakavadi M, Dell J, Grover GJ, Fondell JD. Thyroid hormone suppression of beta-amyloid precursor protein gene expression in the brain involves multiple epigenetic regulatory events. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;339:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raciti M, Granzotto M, Duc MD, Fimiani C, Cellot G, Cherubini E, Mallamaci A. Reprogramming fibroblasts to neural-precursor-like cells by structured overexpression of pallial patterning genes. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2013;57:42–53. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rice JC, Briggs SD, Ueberheide B, Barber CM, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Shinkai Y, Allis CD. Histone methyltransferases direct different degrees of methylation to define distinct chromatin domains. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1591–8. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00479-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mori S, Murakami-Mori K, Bonavida B. Oncostatin M (OM) promotes the growth of DU 145 human prostate cancer cells, but not PC-3 or LNCaP, through the signaling of the OM specific receptor. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:1011–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mori S, Murakami-Mori K, Bonavida B. Interleukin-6 induces G1 arrest through induction of p27(Kip1), a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, and neuron-like morphology in LNCaP prostate tumor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257:609–14. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cody V, Davis PJ, Davis FB. Molecular modeling of the thyroid hormone interactions with alpha v beta 3 integrin. Steroids. 2007;72:165–70. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gianni T, Gatta V, Campadelli-Fiume G. {alpha}V{beta}3-integrin routes herpes simplex virus to an entry pathway dependent on cholesterol-rich lipid rafts and dynamin2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:22260–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014923108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parry C, Bell S, Minson T, Browne H. Herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein H binds to alphavbeta3 integrins. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:7–10. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.80567-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pesola JM, Zhu J, Knipe DM, Coen DM. Herpes simplex virus 1 immediate-early and early gene expression during reactivation from latency under conditions that prevent infectious virus production. J Virol. 2005;79:14516–25. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14516-14525.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tal-Singer R, Peng C, Ponce De Leon M, Abrams WR, Banfield BW, Tufaro F, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ. Interaction of herpes simplex virus glycoprotein gC with mammalian cell surface molecules. J Virol. 1995;69:4471–83. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4471-4483.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park HY, Davidson D, Raaka BM, Samuels HH. The herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene promoter contains a novel thyroid hormone response element. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7:319–30. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.3.8387156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bedadala GR, Pinnoji RC, Palem JR, Hsia SC. Thyroid hormone controls the gene expression of HSV-1 LAT and ICP0 in neuronal cells. Cell Res. 2010;20:587–98. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Foster TP, Rybachuk GV, Kousoulas KG. Expression of the enhanced green fluorescent protein by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) as an in vitro or in vivo marker for virus entry and replication. J Virol Methods. 1998;75:151–60. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(98)00107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bedadala GR, Palem JR, Graham L, Hill JM, McFerrin HE, Hsia SC. Lytic HSV-1 infection induces the multifunctional transcription factor Early Growth Response-1 (EGR-1) in rabbit corneal cells. Virol J. 2011;8:262. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mostafa HH, Thompson TW, Davido DJ. N-terminal phosphorylation sites of herpes simplex virus 1 ICP0 differentially regulate its activities and enhance viral replication. J Virol. 2013;87:2109–19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02588-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Watson S, Mercier S, Bye C, Wilkinson J, Cunningham AL, Harman AN. Determination of suitable housekeeping genes for normalisation of quantitative real time PCR analysis of cells infected with human immunodeficiency virus and herpes viruses. Virol J. 2007;4:130. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.