Abstract

Avian influenza viruses rarely infect humans, but the recently emerged avian H7N9 influenza viruses have caused sporadic infections in humans in China, resulting in 440 confirmed cases with 122 fatalities as of May 16, 2014. In addition, epidemiologic surveys suggest that there have been asymptomatic or mild human infections with H7N9 viruses. These viruses replicate efficiently in mammals, show limited transmissibility in ferrets and guinea pigs, and possess mammalian-adapting amino acid changes that likely contribute to their ability to infect mammals. Here, we summarize the characteristic features of the novel H7N9 viruses and assess their pandemic potential.

Keywords: Avian influenza H7N9 viruses, transmission, pandemic potential

Influenza A virus as a zoonotic pathogen

Influenza A viruses are maintained in wild waterfowl, poultry, humans, pigs, and horses; in addition, infection of dogs, marine mammals, and several other mammalian species has been reported (reviewed in 1). Influenza A viruses are divided into subtypes according to the antigenicity of their two viral surface glycoproteins, hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA); to date, 18 HA and 11 NA subtypes have been identified 1–3. In humans, only viruses of three HA subtypes (H1, H2, and H3) and two NA subtypes (N1 and N2) have caused annual epidemics and sporadically occurring pandemics in the last and current centuries. Influenza A viruses of all subtypes (except for viruses of the H17N10 and H18N11 subtypes, whose genomic material has been identified in bats 2, 3) have been detected in waterfowl, which is considered the natural host of influenza A viruses 1. In waterfowl, most influenza A viruses replicate in the intestinal tract and spread to other birds via the fecal-oral route, whereas the respiratory tract is the major site of influenza A virus replication in mammals 1.

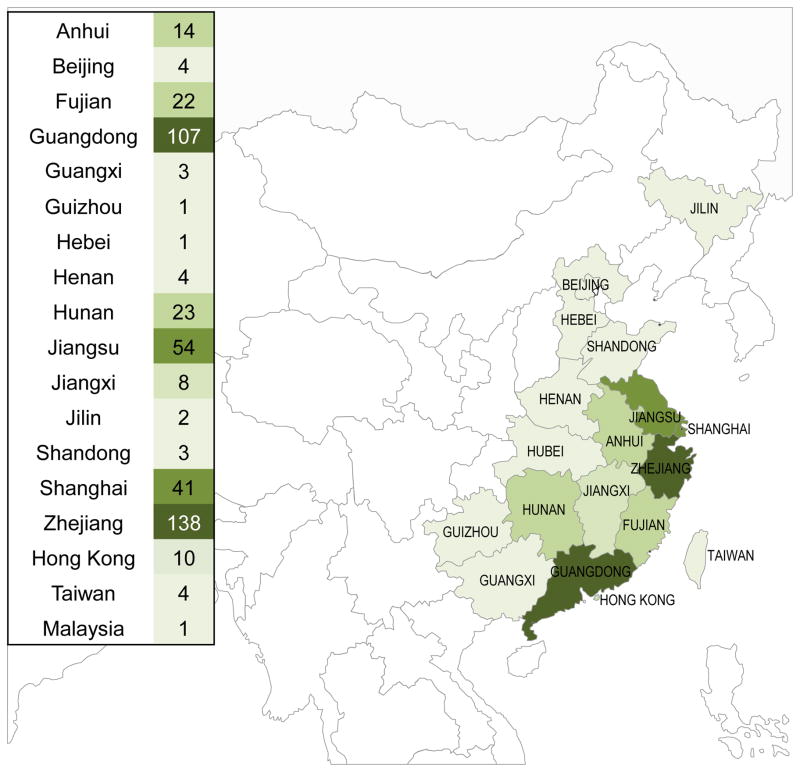

Despite the wide host range of influenza A viruses, their transmission from avian to mammalian species or vice versa is rare due to host range restrictions. Influenza A viruses circulating in avian species (so-called ‘avian influenza viruses’) rarely infects humans, and influenza A viruses circulating in humans (‘human influenza viruses’) rarely infect avian species 4–7. Recently, however, avian influenza A viruses of the H5N1 and H7N9 subtypes have caused hundreds of cases of human infections. So far, sustained human-to-human transmission of these viruses has not been reported. Nonetheless, additional adaptive mutations and/or reassortment with circulating human viruses may enable H5N1 or H7N9 viruses to efficiently infect humans and transmit among them. Because humans lack protective antibodies against these viruses, human-transmitting H5N1 or H7N9 viruses could spread worldwide, resulting in an influenza pandemic. In this review, we focus on the avian H7N9 influenza viruses that recently infected humans in China (Figure 1), describing their biological features and pandemic potential.

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of confirmed human cases of H7N9 influenza virus infection, as of May 16, 2014 (440 total cases). The number of cases in each province is based on data reported by the Centre for Health Protection, Hong Kong PRC SAR (http://www.chp.gov.hk/en/index.html; map revised from a version available at http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/infectious-disease-topics/h7n9-avian-influenza#literature). The darker the green color, the higher the number of cases.

Human infections with avian H7N9 influenza viruses in China in 2013–2014

To date, two sizable waves of human infection with H7N9 viruses have been documented (Figure 2A). The first wave started with a human case of H7N9 influenza virus infection in Shanghai on February 19, 2013 (this case was officially reported on March 31, 2013) 8. In April 2013, the number of human cases of H7N9 virus infections increased significantly, reaching 125 confirmed cases in China by the end of April. Most cases were reported from the provinces of Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Shanghai, which are all located in the eastern part of China (Figures 1 and 2B). The detection of H7N9 viruses in live poultry markets 9–13, and epidemiological data suggesting that contact with poultry or contaminated environments in live bird markets was the likely source of many (although not all) human cases (see ‘Epidemiology of human H7N9 virus infections’) prompted the Chinese government to close live poultry markets in several provinces in mid-April, 2013 14, 15. This measure most likely led to the rapid decline in new human H7N9 cases during the following two weeks 16, 17. The second wave of human infections with H7N9 viruses started in the fall of 2013 18 (Figure 2A), perhaps spurred by the lower fall temperatures and/or the reopening of poultry markets. The number of confirmed human H7N9 virus infections spiked in January and February of 2014, with more than 30 new cases over several consecutive weeks (http://www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/influenza_h7n9/17_ReportWebH7N9Number_20140408.pdf?ua=1). Since February 2014, the number of new human cases has declined, although new infections continue to be reported (Figure 2A). The second, ongoing wave is characterized by a larger number of human H7N9 virus infections, and by more extensive geographic spread. While most human cases during the first wave were reported in Eastern China, the majority of human H7N9 virus infections during the second wave occurred in the southern province of Guangdong (Figure 2B). As of May 16, 2014, a total of 440 human infections with H7N9 viruses have been confirmed with 122 associated deaths (unofficial statement; http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/sites/default/files/public/downloads/topics/cidrap_h7n9_update_051614_0.pdf); 425 of the cases occurred in China (http://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/201405/17/P201405170325.htm), whereas the remaining 15 were exported cases (http://www.chp.gov.hk/files/pdf/2014_avian_influenza_report_vol10_wk19.pdf).

Figure 2.

Number of confirmed human cases of H7N9 influenza virus infection in 2013–2014. Number of laboratory-confirmed cases of human infection with H7N9 influenza virus by week of onset of illness (A) and by Chinese provinces by wave (B). Blue and red bars indicate the number of human cases of H7N9 virus infection detected in the first and second waves, respectively. Provinces are categorized into two groups: northern and southern regions of China. (C) Human cases of H7N9 influenza virus infection by age- and gender-groups. Data for graphs (A) and (C) are based on FluTrackers 2013/14 Human Case List of Provincial/Ministry of Health/Government Confirmed Influenza A (H7N9) Cases with Links (http://www.flutrackers.com/forum/showthread.php?t=202713). Number of cases per province in (B) is based on the data shown at the CIDRAP website (http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/sites/default/files/public/downloads/topics/cidrap_h7n9_update_051614_0.pdf).

Epidemiology of human H7N9 virus infections

Epidemiological studies have shown that H7N9 virus infections have affected mainly middle-aged or older individuals (Figure 2C; i.e., the median age at infection is 63 years) 19–29. Interestingly, two-thirds of the infected individuals have been male 19, 20, 22–24, 27–29 (Figure 2C). The high number of cases among elderly men may reflect socio-economical differences among age groups and genders since elderly men may have frequent work-related or non-job-related contact with poultry. Most H7N9 influenza patients exhibit general influenza-like symptoms, including fever and cough, and more than half of the infections typically progress to severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and multi-organ failure 8, 11, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27, 30–38. Most H7N9 virus-infected patients possessed at least one underlying medical condition, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and/or chronic lung and heart disease 19, 21–23, 25, 26, 28, 31, 39, 40, suggesting that these comorbidities may increase the risk of severe H7N9 virus infection.

The following lines of evidence suggest that contact with live poultry is the source of human H7N9 virus infection: (i) most H7N9 patients had been exposed to live poultry prior to the onset of illness 10, 11, 19–21, 27–29, 31–33, 37–43; (ii) surveillance in live bird markets resulted in the isolation of H7N9 viruses with close homology to the H7N9 viruses isolated from humans in the same area 9–13, 41; (iii) a worker who had culled H7N9 virus-infected poultry developed a mild illness that was traced to a confirmed H7N9 virus infection 44; and (iv) serological surveillance of poultry workers in areas where human cases had been reported revealed antibodies to H7N9 viruses in >6% of the individuals tested, whereas no antibodies to H7N9 viruses were detected in the general population 45. Collectively, these findings suggest an association between human H7N9 infections and poultry, likely in live bird markets, as underscored by the rapid decline in human H7N9 infections upon closure of these markets in mid-April, 2013 15–17.

The finding of H7N9-seropositive poultry workers 45 indicates that subclinical human H7N9 infections occurred. Several sentinel surveillance studies identified H7N9 virus-positive individuals who exhibited only mild-to-moderate influenza virus symptoms and recovered quickly 27, 46, 47. In fact, several studies suggested that a significant number of unidentified, mild cases of human H7N9 infections may have occurred 48, 49.

Although sustained H7N9 virus transmission among humans has not been reported, the potential for human-to-human transmission cannot be ruled out in several family clusters 13, 27, 50, 51. In some of these clusters, H7N9 infections occurred in blood-related family members, implying that close contacts in household settings, and perhaps also genetic factors, may be risk factors for infection with H7N9 viruses.

Genesis of H7N9 influenza viruses

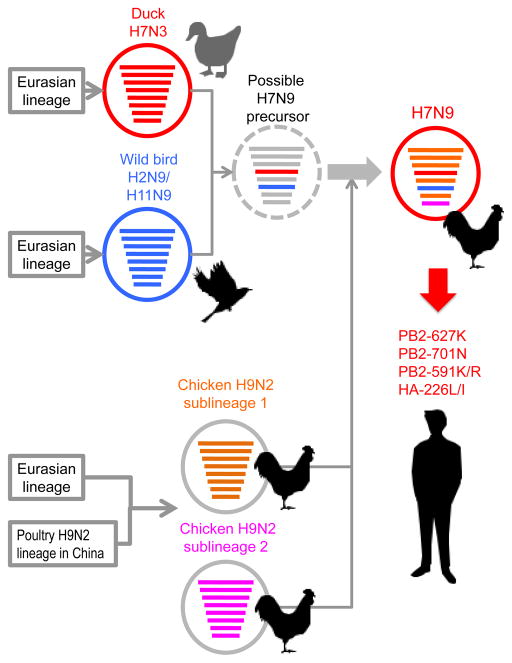

Phylogenetic analyses have revealed that the novel H7N9 viruses likely emerged via reassortment of at least four avian influenza A virus strains (Figure 3). The HA gene of the H7N9 viruses belongs to the Eurasian lineage of avian influenza viruses and is closely related to that of avian H7N3 viruses isolated from ducks in Eastern China in 2010–2011 8, 9, 11, 33, 52–55. The NA gene of the novel H7N9 viruses is closely related to that of avian H2N9 and/or H11N9 influenza viruses isolated from wild migratory birds along the East Asian flyway 8, 9, 11, 33, 52–55. The remaining six viral genes likely originated from two distinct subgroups of an H9N2 sub-lineage (formed by the reassortment of a major H9N2 lineage in China with a Eurasian wild bird virus) circulating in Eastern China 8, 9, 11, 33, 52–55. This genetic heterogeneity suggests that several reassortment events occurred during the generation and ongoing evolution of H7N9 viruses 38, 52, 53, 55–62.

Figure 3.

Genesis of H7N9 influenza virus. The novel H7N9 viruses likely resulted from the reassortment of at least four avian influenza A virus strains. The HA gene of the H7N9 viruses is closely related to the Eurasian lineage of avian influenza viruses and to that of the avian H7N3 viruses recently isolated from ducks in Eastern China. The NA gene of the novel H7N9 viruses is closely related to that of avian H2N9 and/or H11N9 influenza viruses isolated from wild migratory birds along the East Asian flyway. The remaining six viral genes likely originated from two distinct subgroups of an H9N2 sub-lineage circulating in poultry in Eastern China. The virus encircled by the dashed line represents a possible precursor of H7N9 avian influenza viruses. Although the H7N9 viruses currently circulating in birds do not encode determinants of mammalian adaptation (i.e., PB2-627K, PB2-701N, or PB2-591K/R and HA-226L/I), such mutations can arise during H7N9 virus replication in humans. This figure was created by modification of a figure in 53.

Viral determinants of influenza virus host range

A key question stemming from the H7N9 incident is: how was this avian influenza virus able to overcome the host restriction barrier so easily and infect humans? Two viral proteins are known to play a major role in the host range of influenza viruses: the surface glycoprotein, HA, and the polymerase subunit, PB2, which determine host-specific receptor-binding and replicative ability, respectively.

HA determines viral receptor-binding specificity

Influenza virus infections are initiated by the binding of HA to receptors on host cells. Human influenza viruses preferentially bind to sialic acid-α2,6-galactose (SAα2,6Gal), which is the predominant sialyloligosaccharide species expressed on epithelial cells in the upper respiratory tract of humans (reviewed in 63). In contrast, avian influenza viruses preferentially recognize sialic acid-α2,3-galactose (SAα2,3Gal), which is the major sialyloligosaccharide species expressed in the intestinal tract of waterfowl 63, where avian viruses replicate efficiently. Typically, avian influenza viruses exhibit low affinity for SAα2,6Gal (i.e., ‘human-type’ receptors) and therefore, a shift of HA receptor-binding specificity from SAα2,3Gal to SAα2,6Gal is thought to be critical for avian influenza viruses to replicate and transmit efficiently in humans.

Previous studies revealed that the amino acid at position 226 (HA numbers in this article refer to the amino acid position in H3 HA after the removal of the signal peptide) of H3 HAs affects binding to human-type receptors 64. Although sequence analyses of most H7N9 viruses revealed leucine or isoleucine residues at HA position 226 (i.e., the human virus-type residue) (Table 1) 9, 33, 52, 54, purified H7N9 HAs bearing these human virus-type residues at position 226 still preferentially bound to SAα2,3Gal in studies using soluble recombinant trimeric HAs expressed in mammalian cells 65. Therefore, the H7N9 viruses may require additional adaptive mutations in HA, such as a Gly-to-Ser mutation at position 228 of HA 66, to efficiently bind to the human-type receptors. Nonetheless, several groups have demonstrated that whole H7N9 viruses possessing leucine or isoleucine at position 226 of HA bind to both SAα2,3Gal and SAα2,6Gal 65–74, whereas an H7N9 virus encoding glutamine (i.e., the avian virus-type residue) preferentially bound to SAα2,3Gal 75, suggesting that the binding of H7N9 virions to human-type receptors might be affected by other viral components (i.e., the neuraminidase).

Table 1.

Selected amino acids of human-infecting H7N9 viruses

| Viral protein | Amino acid position | Human virus | Avian virus | A/Anhui/1/2013 | A/Shanghai/1/2013 | A/Chicken/Shanghai/S1053/2013 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB2 | 627 | K | E | K | K | E |

|

| ||||||

| HA | 128 (138)a | A | Ab | A | S | A |

| 151 (160)a | K | Ab | A | A | A | |

| 177 (186)a | G | Gb | V | G | V | |

| 217 (226)a | I | Qb | L | Q | L | |

|

| ||||||

| NA | 69–73c | No deletion | No deletion | Deletion | Deletion | Deletion |

| 289 (294)d | R | R | R | K | R | |

Amino acid positions of HA are based on H7 HA numbering (H3 HA numbering is shown in parentheses).

Amino acids characteristic of H7 avian influenza virus.

Amino acid positions of NA are based on N9 NA numbering.

Amino acid positions of NA are based on NA numbering of human-infecting H7N9 viruses (avian N9 NA numbering is shown in parentheses).

In addition, although the leucine residue at position 226 of HA is characteristic of human influenza viruses, it is encoded by most avian H7N9 virus isolates, indicating that it did not arise during H7N9 virus replication in humans. Therefore, the leucine or isoleucine residue at position 226 of HA in H7N9 viruses likely emerged during virus replication in poultry, and may now facilitate the infection of mammalian cells.

PB2 determines viral replicative ability

The PB2 protein is one of the three subunits of the viral polymerase complex, which catalyzes viral replication and transcription in the nucleus of infected cells. A lysine residue at position 627 of PB2 (as found in most human influenza viruses) confers efficient replication to avian influenza viruses in mammals 76. By contrast, glutamic acid at this position, as is found in most avian influenza viruses, significantly restricts avian influenza virus replication in mammals. Currently, the mechanism through which the amino acid at position 627 of PB2 directs viral replicative ability is thought to involve interactions with other viral and/or host proteins 77–81, most likely in a temperature-sensitive manner. Avian body temperature is 41°C 82, whereas the temperatures in the human lung and upper respiratory tract are generally considered to be 37°C and 33°C, respectively. Consequently, most avian influenza viruses replicate more efficiently at 41°C than at 33°C 83. Having a lysine at position 627 of PB2 confers efficient replication to avian influenza viruses at 33°C and 37°C 83, 84, enabling them to establish robust infections in mammals. Additionally, the PB2-627K mutation has recently been shown to increase the transmissibility of avian influenza viruses 85–87.

Sequence analyses have shown that H7N9 viruses isolated from avian hosts possess glutamic acid at position 627 of PB2, whereas many human H7N9 viruses encode lysine at this position (Table 1); this finding suggests that the PB2-627K mutation likely emerges during virus replication in humans, as occurred in the human cases of infection with H7N7 avian influenza viruses in the Netherlands in 2003 88.

Interestingly, some human H7N9 virus isolates that lack PB2-627K possess other potentially mammalian-adapting amino acid changes in PB2 that may compensate for the lack of the mammalian-adapting lysine residue at position 627. Some of the human H7N9 virus isolates that encode PB2-627E possess an aspartic acid-to-asparagine mutation at position 701 of PB2 11, a mutation known to improve avian virus replication in mammalian cells 89. Moreover, a PB2-D701N mutation has been shown to increase the replicative ability and virulence in mice of an H7N9 virus encoding PB2-627E 90. Another human H7N9 isolate lacking PB2-627K acquired a glutamine-to-lysine mutation at position 591 of PB2. A basic amino acid at this position was shown to compensate for the lack of PB2-627K in pandemic 2009 H1N1 viruses 91, 92. A comparison of viruses encoding PB2-627E or PB2-627E/591K showed higher virus titers and virulence in mice for the latter virus 90.

Together, these findings demonstrate that the H7N9 viruses currently circulating in birds do not encode strong determinants of mammalian adaptation in PB2 (namely, PB2-627K, PB2-701N, or PB2-591K/R), but that such mutations arise easily during H7N9 virus replication in humans.

Contribution of amino acids in PA to H7N9 virulence

Viral proteins other than HA and PB2 also contribute to H7N9 virulence, albeit to a lesser extent than these major virulence determinants. Previous studies have suggested a potential role for PA in the adaptation and pathogenicity of avian influenza viruses in a mammalian host 93–95. Several computational and phylogenetic analyses have identified amino acid mutations in the H7N9 PA protein (another subunit of the viral polymerase complex) that are typically found in human-, but not in avian-influenza viruses 58, 96–98. Indeed, experimental testing revealed that some of these amino acids (i.e., A100V, R356K, and N409S) affect H7N9 replicative ability and virulence 96. Interestingly, however, replacement of human-type amino acids in PA with the amino acids commonly found in avian influenza viruses slightly increased their replicative ability in human cells and their virulence in mice, contrary to the expected attenuating effect 96. Although the exact reason for this unexpected finding is unknown, it may be that these mutations are introduced to optimize virus replication in different environments.

Risk assessment of human-to-human transmission of H7N9 viruses in animal models

The primary concern with H7N9 viruses is that they may gain efficient human-to-human transmissibility and cause a pandemic. Influenza viruses transmit from human to human through direct and indirect contact via aerosols, respiratory droplets, and fomites. Several research groups have evaluated the transmissibility of H7N9 viruses in two animal models, namely ferrets and guinea pigs 68, 72, 73, 99–103. These studies were carried out with patient-derived H7N9 viruses encoding HA-226L/PB2-627K (i.e., possessing the mammalian-adapting markers in both proteins) or HA-226Q/PB2-627K (i.e., possessing the mammalian-adapting marker in PB2, but not in HA). Efficient transmission of both human H7N9 viruses through direct contact (i.e., pair-housing an infected and a naïve animal) was observed in the ferret and guinea pig models (i.e., viruses were recovered from all contact animals – naïve animals that were housed in a cage adjacent to each of the infected animals) 72, 99, 101. In contrast, transmission via respiratory droplets was limited in ferrets and guinea pigs (i.e., viruses were recovered only from a few contact animals) 68, 72, 99, 100, 102, 103, except in one study in which efficient respiratory droplet transmission was reported for one of two human H7N9 isolates tested in ferrets73, whereas no transmission was detected for avian H7N9 isolates tested under the same conditions68, 73.

Sequence analyses of viruses obtained from infected and contact animals revealed several mutations in the latter group (Table 2), except for one study that did not detect amino acid changes in viruses recovered from contact animals73. Three non-synonymous mutations, T71I, R131K, and A135T, in HA (H3 numbering), and one non-synonymous mutation, A27T, in NA (N9 numbering) were identified in viruses collected from contact ferrets 68. Positions 131 and 135 are located near the receptor-binding pocket (Figure 4). At position 71, both threonine and isoleucine are commonly found among H7 HAs, and the location of this position ‘underneath’ the receptor-binding pocket suggests a possible effect on HA stability (note that a stabilizing mutation played a critical role in the selection of a ferret-transmissible H5 virus104). Another study detected the double substitution of N133D/N158-159D in HA (H3 numbering) [note that these mutations correspond to N124D/N149D (H7 numbering) described in 100; however, since H7 HA possesses amino acid insertions relative to H3 HA, there is no amino acid in the H3 HA corresponding to that at position 149 of the H7 HA] together with an M523I mutation in the PB1 polymerase protein 100. Interestingly, the N133D/N158-159D double mutation reduced the thermostability of HA and increased HA binding to avian-type – but not human-type – receptors, contrary to what may have been expected for a ferret-transmissible virus 100. In this context, it is worth noting that the N133D/N158-159D double mutation was also detected after replication of a human H7N9 virus isolate in avian species 105. The R140M or R140K mutation detected in viruses isolated from contact ferrets in two independent studies 72, 103 localize to the rim of the HA receptor-binding pocket, and it is thus conceivable that they affect HA receptor-binding properties. In addition to the R140K mutation in HA, this transmissible virus also possessed a D678Y mutation in PB2, an I109T mutation in the nucleoprotein NP, and a T10I mutation in NA 103. Collectively, these data demonstrate the inherent capability of H7N9 viruses to transmit among mammals, although the efficiency of transmission is lower than that of human influenza viruses.

Table 2.

Amino acid changes found in H7N9 viruses isolated from contact ferrets in transmission studiesa

| Viral protein | Amino acid position | Reference virus | Xu et al.103 | Watanabe et al.68 | Richard et al.100 | Belser et al.72 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB2 | 678 | D | Y | |||

|

| ||||||

| PB1 | 523 | M | I | |||

| 678 | S | N | ||||

|

| ||||||

| PA | 349 | E | G | |||

| 531 | R | K | ||||

|

| ||||||

| HAb | 61 (71) | T | I | |||

| 121 (131) | R | K | ||||

| 123 (133) | N | D | ||||

| 125 (135) | A | T | ||||

| 130 (140) | R | Kc | M | |||

| 149 (158–159)d | N | D | ||||

| 210 (219) | A | E | ||||

|

| ||||||

| NA | 10 | T | I | I | ||

| 27 | A | T | ||||

|

| ||||||

| NP | 109 | I | T | |||

| 225 | I | L | ||||

Viruses isolated from the nasal washes of contact ferrets in the human-infecting H7N9 virus (A/Anhui/1/2013) group were sequenced. Zhang et al. found no amino acid substitutions in viruses recovered from the contact ferrets 73. No sequence data were presented in Zhu et al. 99.

Amino acid positions of HA are based on H7 HA numbering. H3 HA numbering is shown in parentheses.

The HA R140K mutation (H3 numbering) corresponds to the HA R148K mutation (H7 numbering) described by Xu et al. 103 because they counted the signal peptides of HA.

The H7 HA possesses amino acid insertions corresponding to the position between residues 158 and 159 in the H3 HA.

Figure 4.

Amino acid changes in the HA of viruses recovered from contact ferrets in the human-infecting H7N9 virus groups. Shown is the three-dimensional structure of A/Anhui/1/2003 (H7N9) HA (PDB ID: 4BSE) in complex with human receptor analogues and a close-up view of the globular head. Mutations shown in cyan (i.e., A138S, G186V, and Q226L/I) are known to increase the binding of avian H5 and H7 viruses to human-type receptors. Mutations that emerged in HA of human-infecting H7N9 viruses during replication and/or transmission in ferrets are shown in green (see also Table 2). The human receptor analogue is shown in orange. Images were created with MacPymol [http://www.pymol.org/].

In patients treated with NA inhibitors, resistant H7N9 variants have been detected encoding the R292K mutation in NA that confers resistance to oseltamivir 106–110. Oseltamivir-resistance mutations frequently reduce viral fitness (reviewed in 111), although compensatory amino acid changes can restore it 112. The NA-R292K mutation was found to reduce H7N9 viral fitness in cultured cells in one study 106; however, another study did not detect an effect of the NA-R292K mutation in an H7N9 virus on virulence in mice or transmissibility in guinea pigs 102, suggesting that oseltamivir-resistant H7N9 viruses may be competitive in nature.

Natural isolates of highly pathogenic avian H5N1 viruses do not transmit among ferrets (reviewed in 113), whereas novel H7N9 have limited transmissibility in mammalian models. Thus, the pandemic potential of novel H7N9 viruses appears to be greater than that of highly pathogenic H5N1 viruses. Combined with the emergence of already partially adapted phenotypes and the relatively high fitness of oseltamivir-resistant H7N9 viruses, these novel viruses pose a significant pandemic threat.

Concluding remarks

To date, the novel H7N9 influenza viruses have not caused a pandemic in humans due to their inability to support sustained human-to-human transmission. However, these viruses exhibit high replicative ability and limited transmissibility in mammals, have acquired mammalian-adapting amino acid changes, may reassort with circulating human viruses (based on the reported coinfection of a patient with H7N9 and human H3N2 viruses) 114, and readily acquire resistance to the NA inhibitor oseltamivir 68, 72, 73, 99, 100. Moreover, humans lack protective immunity to H7N9 infection 68 and frequently show relatively weak antibody responses when infected with these viruses 45, 115. Therefore, a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms of pathogenicity, transmissibility, and immunogenicity of the novel H7N9 influenza viruses, combined with continued surveillance in avian and human populations, will be vital to develop countermeasures against H7N9 infections in humans.

Highlights.

Human cases of avian influenza H7N9 virus infection have been reported in China.

The avian influenza H7N9 viruses possess several mammalian-adapting amino acid changes.

H7N9 viruses isolated from humans transmit among subsets of ferrets or guinea pigs.

Additional adaptive mutations in H7N9 viruses may lead to a pandemic.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Susan Watson for editing the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Public Health Service research grants, by RO1 AI080598 and R56 AI099275, by ERATO (Japan Science and Technology Agency), by the Strategic Basic Research Programs of the Japan Science and Technology Agency, Japan, and by J-GRID (Japan Initiative for Global Research Network on Infectious Diseases).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wright PF, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y, editors. Orthomyxoviruses. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tong S, et al. A distinct lineage of influenza A virus from bats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:4269–4274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116200109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tong S, et al. New world bats harbor diverse influenza a viruses. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003657. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beare AS, Webster RG. Replication of avian influenza viruses in humans. Arch Virol. 1991;119:37–42. doi: 10.1007/BF01314321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hinshaw VS, et al. Are seals frequently infected with avian influenza viruses? J Virol. 1984;51:863–865. doi: 10.1128/jvi.51.3.863-865.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy BR, et al. Avian-human reassortant influenza A viruses derived by mating avian and human influenza A viruses. J Infect Dis. 1984;150:841–850. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.6.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webster RG, et al. Intestinal influenza: replication and characterization of influenza viruses in ducks. Virology. 1978;84:268–278. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(78)90247-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prevention., C.f.D.C.a. Emergence of Avian Influenza A(H7N9) Virus Causing Severe Human Illness - China, February–April 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013:366–371. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi JZ, et al. Isolation and characterization of H7N9 viruses from live poultry markets-Implication of the source of current H7N9 infection in humans. Chinese Sci Bull. 2013;58:1857–1863. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han J, et al. Epidemiological link between exposure to poultry and all influenza A(H7N9) confirmed cases in Huzhou city, China, March to May 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18 pii=20481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y, et al. Human infections with the emerging avian influenza A H7N9 virus from wet market poultry: clinical analysis and characterisation of viral genome. Lancet. 2013;381:1916–1925. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60903-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang C, et al. Relationship between domestic and wild birds in live poultry market and a novel human H7N9 virus in China. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:34–37. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu T, et al. One family cluster of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus infection in Shandong, China. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murhekar M, et al. Avian influenza A(H7N9) and the closure of live bird markets. Western Pac Surveill Response J. 2013;4:4–7. doi: 10.5365/WPSAR.2013.4.2.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu J, et al. Reducing exposure to avian influenza H7N9. Lancet. 2013;381:1815–1816. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60950-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu H, et al. Effect of closure of live poultry markets on poultry-to-person transmission of avian influenza A H7N9 virus: an ecological study. Lancet. 2014;383:541–548. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61904-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chowell G, et al. Transmission potential of influenza A/H7N9, February to May 2013, China. BMC Med. 2013;11:214. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen E, et al. Human infection with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus re-emerges in China in winter 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.43.20616. pii: 20616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu S, et al. Prognosis of 18 H7N9 avian influenza patients in Shanghai. PLoS One. 2014;9:e88728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding H, et al. Epidemiologic characterization of 30 confirmed cases of human infection with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus in Hangzhou, China. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:175. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang XF, et al. Clinical features of three avian influenza H7N9 virus-infected patients in Shanghai. Clin Respir J. 2013 doi: 10.1111/crj.12087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang C, et al. Comparison of patients hospitalized with influenza A subtypes H7N9, H5N1, and 2009 pandemic H1N1. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1095–1103. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao HN, et al. Clinical findings in 111 cases of influenza A (H7N9) virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2277–2285. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dudley JP, Mackay IM. Age-specific and sex-specific morbidity and mortality from avian influenza A(H7N9) J Clin Virol. 2013;58:568–570. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu S, et al. Epidemiological, clinical and viral characteristics of fatal cases of human avian influenza A (H7N9) virus in Zhejiang Province, China. J Infect. 2013;67:595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ji H, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics and risk factors for death of patients with avian influenza A H7N9 virus infection from Jiangsu Province, Eastern China. PLoS One. 2014;9:e89581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Q, et al. Epidemiology of human infections with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus in China. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:520–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang W, et al. Epidemiologic characteristics of cases for influenza A(H7N9) virus infections in China. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:619–620. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cowling BJ, et al. Comparative epidemiology of human infections with avian influenza A H7N9 and H5N1 viruses in China: a population-based study of laboratory-confirmed cases. Lancet. 2013;382:129–137. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61171-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang X, et al. ARDS associated with pneumonia caused by avian influenza A H7N9 virus treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Clin Respir J. 2014 doi: 10.1111/crj.12140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen E, et al. The first avian influenza A (H7N9) viral infection in humans in Zhejiang Province, China: a death report. Front Med. 2013;7:333–344. doi: 10.1007/s11684-013-0275-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xie L, et al. Clinical and epidemiological survey and analysis of the first case of human infection with avian influenza A(H7N9) virus in Hangzhou, China. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32:1617–1620. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-1922-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao R, et al. Human infection with a novel avian-origin influenza A (H7N9) virus. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1888–1897. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Q, et al. Emerging H7N9 influenza A (novel reassortant avian-origin) pneumonia: radiologic findings. Radiology. 2013;268:882–889. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu L, et al. Clinical, virological, and histopathological manifestations of fatal human infections by avian influenza A(H7N9) virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1449–1457. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li J, et al. Environmental connections of novel avian-origin H7N9 influenza virus infection and virus adaptation to the human. Sci China Life Sci. 2013;56:485–492. doi: 10.1007/s11427-013-4491-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mei Z, et al. Avian influenza A(H7N9) virus infections, Shanghai, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1179–1181. doi: 10.3201/eid1907.130523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.To KK, et al. Unique reassortant of influenza A(H7N9) virus associated with severe disease emerging in Hong Kong. J Infect. 2014;69:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu S, et al. Clinical findings for early human cases of influenza A(H7N9) virus infection, Shanghai, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1142–1146. doi: 10.3201/eid1907.130612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ai J, et al. Case-control study of risk factors for human infection with influenza A(H7N9) virus in Jiangsu Province, China, 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:20510. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.26.20510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bao CJ, et al. Live-animal markets and influenza A (H7N9) virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2337–2339. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1306100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun J, et al. Comparison of characteristics between patients with H7N9 living in rural and urban areas of Zhejiang Province, China: a preliminary report. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93775. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang P, et al. A case of avian influenza A (H7N9) virus occurring in the summer season, China. J Infect. 2013;67:624–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lv H, et al. Mild illness in avian influenza A(H7N9) virus-infected poultry worker, Huzhou, China, April 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1885–1888. doi: 10.3201/eid1911.130717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang S, et al. Avian-origin influenza A(H7N9) infection in influenza A(H7N9)-affected areas of China: a serological study. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:265–269. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ip DK, et al. Detection of mild to moderate influenza A/H7N9 infection by China’s national sentinel surveillance system for influenza-like illness: case series. BMJ. 2013;346:f3693. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang P, et al. Surveillance for avian influenza A(H7N9), Beijing, China, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:2041–2043. doi: 10.3201/eid1912.130983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu H, et al. Human infection with avian influenza A H7N9 virus: an assessment of clinical severity. Lancet. 2013;382:138–145. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61207-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cowling BJ, et al. Preliminary inferences on the age-specific seriousness of human disease caused by avian influenza A(H7N9) infections in China, March to April 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:20475. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jie Z, et al. Family outbreak of severe pneumonia induced by H7N9 infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:114–115. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201304-0797LE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qi X, et al. Probable person to person transmission of novel avian influenza A (H7N9) virus in Eastern China, 2013: epidemiological investigation. BMJ. 2013;347:f4752. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu D, et al. Origin and diversity of novel avian influenza A H7N9 viruses causing human infection: phylogenetic, structural, and coalescent analyses. Lancet. 2013;381:1926–1932. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60938-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lam TT, et al. The genesis and source of the H7N9 influenza viruses causing human infections in China. Nature. 2013;502:241–244. doi: 10.1038/nature12515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kageyama T, et al. Genetic analysis of novel avian A(H7N9) influenza viruses isolated from patients in China, February to April 2013. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:20453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu A, et al. Sequential reassortments underlie diverse influenza H7N9 genotypes in China. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:446–452. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cui L, et al. Dynamic reassortments and genetic heterogeneity of the human-infecting influenza A (H7N9) virus. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3142. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang L, et al. Rapid reassortment of internal genes in avian influenza A(H7N9) virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1059–1061. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Neumann G, et al. Identification of Amino Acid Changes That May Have Been Critical for the Genesis of A(H7N9) Influenza Viruses. J Virol. 2014;88:4877–4896. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00107-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Meng Z, et al. Possible pandemic threat from new reassortment of influenza A(H7N9) virus in China. Euro Surveill. 2014;19 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2014.19.6.20699. pii: 20699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu X, et al. Influenza H7N9 and H9N2 viruses: coexistence in poultry linked to human H7N9 infection and genome characteristics. J Virol. 2014;88:3423–3431. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02059-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Han J, et al. Cocirculation of Three Hemagglutinin and Two Neuraminidase Subtypes of Avian Influenza Viruses in Huzhou, China, April 2013: Implication for the Origin of the Novel H7N9 Virus. J Virol. 2014;88:6506–6511. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03319-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu J, et al. Complex reassortment of polymerase genes in Asian influenza A virus H7 and H9 subtypes. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;23:203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.de Graaf M, Fouchier RA. Role of receptor binding specificity in influenza A virus transmission and pathogenesis. EMBO J. 2014;33:823–841. doi: 10.1002/embj.201387442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rogers GN, et al. Single amino acid substitutions in influenza haemagglutinin change receptor binding specificity. Nature. 1983;304:76–78. doi: 10.1038/304076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xu R, et al. Preferential recognition of avian-like receptors in human influenza A H7N9 viruses. Science. 2013;342:1230–1235. doi: 10.1126/science.1243761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tharakaraman K, et al. Glycan receptor binding of the influenza A virus H7N9 hemagglutinin. Cell. 2013;153:1486–1493. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou J, et al. Biological features of novel avian influenza A (H7N9) virus. Nature. 2013;499:500–503. doi: 10.1038/nature12379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Watanabe T, et al. Characterization of H7N9 influenza A viruses isolated from humans. Nature. 2013;501:551–555. doi: 10.1038/nature12392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dortmans JC, et al. Adaptation of novel H7N9 influenza A virus to human receptors. Sci Rep. 2013;3:3058. doi: 10.1038/srep03058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang H, et al. Structural analysis of the hemagglutinin from the recent 2013 H7N9 influenza virus. J Virol. 2013;87:12433–12446. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01854-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ramos I, et al. H7N9 influenza viruses interact preferentially with alpha2,3-linked sialic acids and bind weakly to alpha2,6-linked sialic acids. J Gen Virol. 2013;94:2417–2423. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.056184-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Belser JA, et al. Pathogenesis and transmission of avian influenza A (H7N9) virus in ferrets and mice. Nature. 2013;501:556–559. doi: 10.1038/nature12391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang Q, et al. H7N9 influenza viruses are transmissible in ferrets by respiratory droplet. Science. 2013;341:410–414. doi: 10.1126/science.1240532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xiong X, et al. Receptor binding by an H7N9 influenza virus from humans. Nature. 2013;499:496–499. doi: 10.1038/nature12372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shi Y, et al. Structures and receptor binding of hemagglutinins from human-infecting H7N9 influenza viruses. Science. 2013;342:243–247. doi: 10.1126/science.1242917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hatta M, et al. Molecular basis for high virulence of Hong Kong H5N1 influenza A viruses. Science. 2001;293:1840–1842. doi: 10.1126/science.1062882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Labadie K, et al. Host-range determinants on the PB2 protein of influenza A viruses control the interaction between the viral polymerase and nucleoprotein in human cells. Virology. 2007;362:271–282. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rameix-Welti MA, et al. Avian Influenza A virus polymerase association with nucleoprotein, but not polymerase assembly, is impaired in human cells during the course of infection. J Virol. 2009;83:1320–1331. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00977-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Moncorge O, et al. Evidence for avian and human host cell factors that affect the activity of influenza virus polymerase. J Virol. 2010;84:9978–9986. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01134-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mehle A, Doudna JA. An inhibitory activity in human cells restricts the function of an avian-like influenza virus polymerase. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Foeglein A, et al. Influence of PB2 host-range determinants on the intranuclear mobility of the influenza A virus polymerase. J Gen Virol. 2011;92:1650–1661. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.031492-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Prinzinger R, et al. Body-Temperature in Birds. Comp Biochem Phys A. 1991;99:499–506. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hatta M, et al. Growth of H5N1 influenza A viruses in the upper respiratory tracts of mice. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:1374–1379. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Massin P, et al. Residue 627 of PB2 is a determinant of cold sensitivity in RNA replication of avian influenza viruses. J Virol. 2001;75:5398–5404. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.5398-5404.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Van Hoeven N, et al. Human HA and polymerase subunit PB2 proteins confer transmission of an avian influenza virus through the air. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3366–3371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813172106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Steel J, et al. Transmission of influenza virus in a mammalian host is increased by PB2 amino acids 627K or 627E/701N. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000252. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Watanabe T, et al. Circulating avian influenza viruses closely related to the 1918 virus have pandemic potential. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:692–705. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jonges M, et al. Emergence of the virulence-associated PB2 E627K substitution in a fatal human case of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus A(H7N7) infection as determined by Illumina ultra-deep sequencing. J Virol. 2014;88:1694–1702. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02044-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li Z, et al. Molecular basis of replication of duck H5N1 influenza viruses in a mammalian mouse model. J Virol. 2005;79:12058–12064. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.12058-12064.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mok CK, et al. Amino acid substitutions in polymerase basic protein 2 gene contribute to the pathogenicity of the novel A/H7N9 influenza virus in mammalian hosts. J Virol. 2014;88:3568–3576. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02740-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yamada S, et al. Biological and structural characterization of a host-adapting amino acid in influenza virus. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001034. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mehle A, Doudna JA. Adaptive strategies of the influenza virus polymerase for replication in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21312–21316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911915106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kim JH, et al. Role of host-specific amino acids in the pathogenicity of avian H5N1 influenza viruses in mice. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:1284–1289. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.018143-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bussey KA, et al. PA residues in the 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza virus enhance avian influenza virus polymerase activity in mammalian cells. J Virol. 2011;85:7020–7028. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00522-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mehle A, et al. Reassortment and mutation of the avian influenza virus polymerase PA subunit overcome species barriers. J Virol. 2012;86:1750–1757. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06203-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yamayoshi S, et al. Virulence-affecting amino acid changes in the PA protein of H7N9 influenza A viruses. J Virol. 2014;88:3127–3134. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03155-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liu Q, et al. Genomic signature and protein sequence analysis of a novel influenza A (H7N9) virus that causes an outbreak in humans in China. Microbes Infect. 2013;15:432–439. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Xu W, et al. PA-356R is a unique signature of the avian influenza A (H7N9) viruses with bird-to-human transmissibility: potential implication for animal surveillances. J Infect. 2013;67:490–494. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhu H, et al. Infectivity, transmission, and pathology of human-isolated H7N9 influenza virus in ferrets and pigs. Science. 2013;341:183–186. doi: 10.1126/science.1239844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Richard M, et al. Limited airborne transmission of H7N9 influenza A virus between ferrets. Nature. 2013;501:560–563. doi: 10.1038/nature12476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gabbard JD, et al. Novel H7N9 influenza virus shows low infectious dose, high growth rate, and efficient contact transmission in the guinea pig model. J Virol. 2014;88:1502–1512. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02959-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hai R, et al. Influenza A(H7N9) virus gains neuraminidase inhibitor resistance without loss of in vivo virulence or transmissibility. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2854. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Xu L, et al. Novel avian-origin human influenza A(H7N9) can be transmitted between ferrets via respiratory droplets. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:551–556. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Imai M, et al. Experimental adaptation of an influenza H5 HA confers respiratory droplet transmission to a reassortant H5 HA/H1N1 virus in ferrets. Nature. 2012;486:420–428. doi: 10.1038/nature10831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pantin-Jackwood MJ, et al. Role of Poultry in the Spread of Novel H7N9 Influenza Virus in China. J Virol. 2014;88:5381–5390. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03689-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wu Y, et al. Characterization of two distinct neuraminidases from avian-origin human-infecting H7N9 influenza viruses. Cell Res. 2013;23:1347–1355. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hu Y, et al. Association between adverse clinical outcome in human disease caused by novel influenza A H7N9 virus and sustained viral shedding and emergence of antiviral resistance. Lancet. 2013;381:2273–2279. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yen HL, et al. Resistance to neuraminidase inhibitors conferred by an R292K mutation in a human influenza virus H7N9 isolate can be masked by a mixed R/K viral population. MBio. 2013;4:e00396–13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00396-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lin PH, et al. Virological, serological, and antiviral studies in an imported human case of avian influenza A(H7N9) virus in Taiwan. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:242–246. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Shen Z, et al. Host immunological response and factors associated with clinical outcome in patients with the novel influenza A H7N9 infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;20:O493–500. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Govorkova EA. Consequences of resistance: in vitro fitness, in vivo infectivity, and transmissibility of oseltamivir-resistant influenza A viruses. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7(Suppl 1):50–57. doi: 10.1111/irv.12044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bloom JD, et al. Permissive secondary mutations enable the evolution of influenza oseltamivir resistance. Science. 2010;328:1272–1275. doi: 10.1126/science.1187816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Imai M, et al. Transmission of influenza A/H5N1 viruses in mammals. Virus Res. 2013;178:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhu Y, et al. Human co-infection with novel avian influenza A H7N9 and influenza A H3N2 viruses in Jiangsu province, China. Lancet. 2013;381:2134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Guo L, et al. Human antibody responses to avian influenza A(H7N9) virus, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:192–200. doi: 10.3201/eid2002.131094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]