Abstract

Older individuals with emotional distress and a history of psychologic trauma are at risk for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and major depression. This study was an exploratory, secondary analysis of data from the study “Prevention of Depression in Older African Americans”. It examined whether Problem Solving Therapy - Primary Care (PST-PC) would lead to improvement in PTSD symptoms in patients with subsyndromal depression and a history of psychologic trauma. The control condition was dietary education (DIET). Participants (n = 60) were age 50 or older with scores on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies -Depression scale of 11 or greater and history of psychologic trauma. Exclusions stipulated no major depression and substance dependence within a year. Participants were randomized to 6–8 sessions of either PST-PC or DIET and followed 2 years with booster sessions every 6 months; 29 participants were in the PST-PC group and 31 were in the DIET group. Mixed effects models showed that improvement of PTSD Check List scores was significantly greater in the DIET group over two years than in the PST-PC group (based on a group*time interaction). We observed no intervention*time interactions in Beck Depression Inventory or Brief Symptom Inventory-Anxiety subscale scores.

Keywords: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, Dietary Education, Problem Solving Therapy

1. Introduction

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is prevalent and associated with psychiatric comorbidity (Kessler et al., 2005), psychiatric impairment (Schnurr et al., 2000) and increased use of both medical and psychiatric services (Walker et al., 2003). In individuals ≥ 65 years of age, rates of PTSD in primary care clinics have been reported to be approximately 6.3% (Freuh et al., 2007). Thus, assessment for PTSD is important and relevant to clinical practice (Kulka et al., 1990).

Syndromal PTSD appears to represent the upper tail-end of a stress-response continuum (Ruscio et al., 2002). The concept of partial or subthreshold PTSD has emerged from these observations and has been shown to have significant clinical consequences. Subthreshold PTSD (Grubaugh et al., 2005) is associated with intermediate levels of psychosocial impairment and health related quality of life relative to individuals without PTSD and those with full syndromal PTSD.

Subsyndromal depressive disorders are common in primary care settings (Oslin et al., 2006; Ross et al., 2008) and generally include various disorders such as dysthymia, minor depression, adjustment disorder with depression, and mixed anxiety depression. Although no single approach to defining subjects with ‘less than Major Depression’ has been universally accepted (Lyness et al., 2007), understanding this spectrum is important since already symptomatic individuals with subsyndromal depression are at high risk for developing episodes of major depression and PTSD (Lyness et al., 2007; Ross et al., 2008). How much subsyndromal depression is due to PTSD symptoms is not clear.

We undertook an exploratory, secondary analysis of a subgroup of data from the study “Prevention of Depression in Older African Americans,” which randomized 247 individuals with subsyndromal depression to a preventive intervention consisting of Problem Solving Therapy-Primary Care and to an attention only intervention providing education in healthy nutritional practices (DIET). Since the trial was intended to be an indicated depression prevention intervention, we recruited individuals having subsyndromal depression. Our operational definition of subsyndromal depression was defined as a score of 11 or greater on the Centers for Epidemiologic Studies –Depression (CES-D) scale, a scale which assesses emotional distress (Radloff et al., 1977; Reynolds et al., 2014). The CES-D scale has been used to screen for depressed individuals in other studies (Bruce et al., 2004). Both PST-PC and DIET encouraged and reinforced active coping to tackle a problem (in the case of DIET, a health issue). Dietary Education was chosen since it was 1) a culturally acceptable active control condition that facilitates enrollment and retention of participants; 2) more than a face to face contact, it is an active intervention in its own right, coaching people to address the challenges of implementing healthy dietary practices (an active coping component); 3) had no issues of safety, stigma, or financial burden; and 4) many individuals reporting high levels of life stress also reported being overweight or obese.

We focused on the subgroup of individuals with symptoms of emotional distress and a history of psychologic trauma. The trial is described in Sriwattanakomen et al., (2008, 2010), Kasckow et al., (2010, 2012, 2013) and Reynolds et al., (2014). The individuals with a history of psychologic trauma (n = 60) were a subset of the total sample of individuals with subsyndromal depression (n = 247). As a treatment, Problem Solving Therapy focuses on improving problem solving skills and depressive symptoms. The ability of depressed older individuals to use important components of Problem Solving Therapy (such as setting goals, generating alternative solutions, decision making and solution implementation) is what accounts for improvements in depression in older individuals (Alexopoulos et al., 2003).

Depressive symptoms are negatively associated with problem solving skills (Kasckow et al., 2010) and individuals with symptoms of PTSD also have deficient problem solving skills (Nezu and Carneville, 1987; Sutherland and Bryant, 2008 ). Furthermore, higher PTSD scores are known to predict poorer problem solving skills in subsyndromally depressed individuals (Kasckow et al., 2012), which suggests that Problem Solving Therapy may be an appropriate treatment or preventive intervention for this population.

Furthermore, we focused the parent trial: “Prevention of Depression in Older African Americans” on recruiting disadvantaged participants, many of whom inhabit neighborhoods perceived to be dangerous. Because PST-PC teaches the practice of active coping and confronting difficulties in one’s life, we thought it would benefit participants not only with respect to protecting them from depression but also in respect to navigating the challenges of living in disadvantaged, low-resource neighborhoods. PST-PC teaches people to see the connection between active coping/problem solving/learning from problems and feeling better. This is important from a public health perspective since effective interventions are needed to reduce rates of new onset anxiety disorders in individuals with subsyndromal depressive symptoms. Thus, we hypothesized that in those individuals presenting with emotional distress and a history of traumatic exposure, Problem Solving Therapy would lead to a greater improvement in PTSD symptoms than in those receiving dietary education (DIET).

2.0 Methods

All participants were subjects in an NIH- sponsored trial to determine the ability of Problem Solving Therapy in Primary Care vs a dietary education control to prevent or delay episodes of major depression in individuals with subsyndromal depression, as described previously (Sriwattanakomen, 2008; 2010; Kasckow et al., 2010, 2012, 2013; Reynolds et al., 2014). “Prevention of Depression in Older African Americans,” aimed to explore whether race could moderate Problem Solving Therapy’s hypothesized depression preventive efficacy. The analysis presented here used intervention data acquired during the period 3/2007 until 8/2012.

Individuals were recruited at community and primary care clinics in the Pittsburgh metropolitan area. If interested individuals contacted a research team member, they would then be screened with the Centers for Epidemiological Studies–Depression scale (CES-D scale; Radloff, 1977) under the authority of a University of Pittsburgh IRB approved ‘Waiver of Informed Consent’ and ‘Waiver of Documentation of Informed Consent’. Participants ≥ 50 years of age with ≥ 11 scores on the CES-D scale were then asked to come in to consider signing informed consent. The age to enter was 50 or greater on the advice of our Community Advisory Board in the Graduate School of Public Health. These colleagues advised that since we were oversampling African Americans, enrolling somewhat younger participants would facilitate intake of those of greater medical comorbidity still in their 50’s. There were 247 individuals who were randomized in the parent trial.

We assessed whether individuals had experienced a traumatic event sometime in their lifetime. This was obtained during administration of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis 1 disorders (SCID; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). A traumatic event was defined as exposure to 1) actual or threatened death or serious injury, 2) a threat to one’s physical integrity; 3) witnessing an event that involves death, injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of another person; or 4) learning about an unexpected or violent death, serious harm, threat of death or injury experienced by a family member or other close associate. The diagnosis of PTSD depends on the presence of intense fear, helplessness, or horror in response to the event (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Any individual who met criteria for exposure to a significant psychological traumatic event sometime in their life were included in this secondary analysis.

Demographic information was collected and included age, gender, self-reported race, employment status and marital status. Clinical assessments included the civilian version of the PTSD Checklist (PCL-C; Weathers et al 1993), the Social Problem Solving Inventory (SPSI; D’Zurilla and Nezu, 1990), the 17 item Hamilton Rating Scale (HSRD; Hamilton, 1960), the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale – Geriatrics (Miller et al., 1992), the anxiety subscale of the Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis and Melisaratos, 1983), health-related quality of life (SF 12; Ware, 1997) and social and physical functioning (Late Life Function and Disability Instrument, LL-FDI; Sayers et al., 2004).

2.1 Interventions

The experimental group received manualized problem solving therapy for primary care (PST-PC; Arean et al., 1999). The first session lasted an hour and each subsequent session lasted 30 minutes each. Participants in the DIET group received coaching in healthy eating practices. Using a manualized educational intervention, interventionists reviewed general nutrition guidelines, including the US Department of Agriculture Food Pyramid, helped with preparing weekly menus and grocery lists, saving food coupons, and reviewed food intake since last visit. The topics discussed included access to healthy food, cost of food, meal preparation, culturally specific and acceptable foods, and specific topics raised by participants.

PST-PC and DIET had similar numbers of sessions (6–8 sessions each) and semi-annual boosters (30–45 minutes at 3, 9, and 15 months). Both interventions included homework assignments, monitoring of adherence, and both focused on concerns identified by each participant. Both interventionists were provided by staff trained at the NIMH-sponsored Advanced Center for Late Life Depression Prevention and Treatment at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and Graduate School of Public Health. Interventionists were 6 non-Latino White social workers and mental health nurses. The same interventionists delivered both PST-PC and DIET, in order to avoid confounding intervention with clinician effects. The protocol was overseen by a Data Safety Monitoring Board and reviewed and approved annually by the University of Pittsburgh’s Institutional Review Board.

2.2 Statistical Analysis

Prior to all analyses, we examined data for normality and used transformations where necessary. Our analysis was based on an intent to treat approach and utilized hierarchical linear models. Comparisons were made according to the assigned intervention group regardless of study completion. Descriptive statistics were generated (means, standard deviations and %, n) to characterize demographics and baseline clinical characteristics of subjects randomized to PST-PC and DIET. Differences between the 2 intervention groups were tested using t tests or Wilcoxon exact tests for continuous measures and chi-square or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables.

We tested for group, time and group by time differences by employing a mixed models approach. This was accomplished with the SAS PROC MIXED procedure which uses all available data regardless of the number of follow-up assessments available. Models first considered a quadratic effect to test for nonlinear trajectories. When the quadratic component was not significant, we moved to a linear model. A best fit model was determined comparing Bayesian information criterion (BIC) values between models. Time was treated as continuous with actual visit date used to model time. Variables that differed between the 2 intervention groups at baseline or had other clinical relevance were considered as possible covariates in the mixed models. We examined PCL-C scores as main outcome and SPSI, BDI and BSI anxiety scores as secondary outcome measures. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 statistical software (SAS Institute, INC, Cary, North Carolina).

3.0 Results

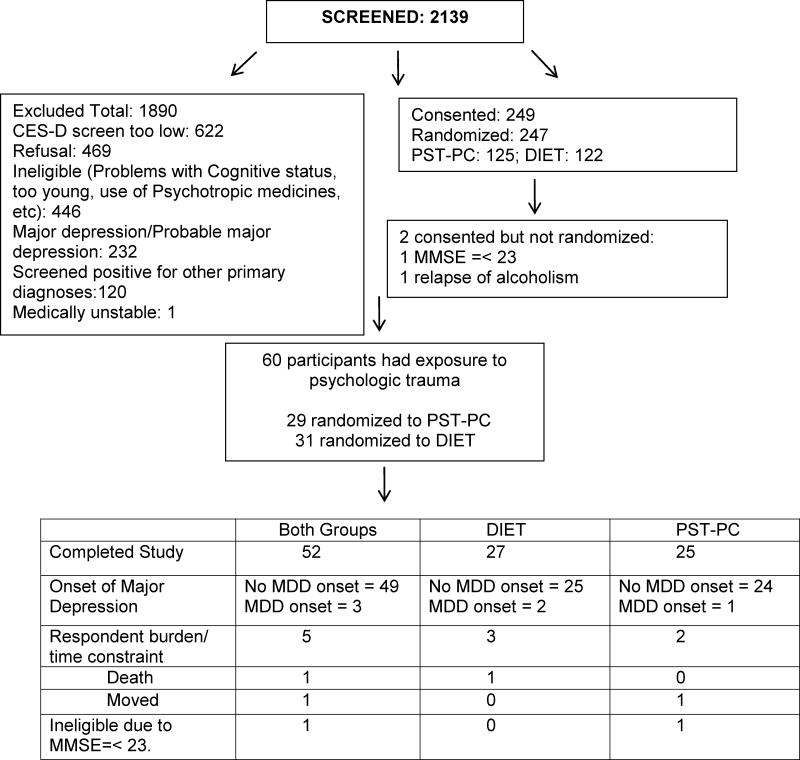

Demographic and clinical characteristics of our study group are displayed in Table 1. A recruitment flow chart is displayed in Figure 1. In summary, of the 60 reporting a traumatic event, 52 completed the study (49 completed without onset of MDD and 3 experienced onset of MDD which was study endpoint); 5 withdrew consent due to respondent burden or time constraint, 1 participant died, one participant moved and one participant was determined ineligible due to Mini-mental state score of 23 when study criteria required a score of 24 or higher. Also, there were 5 participants who had missing baseline data but had data at later time points.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical measures.

| DIET N=31 Mean (STD) or % [n if reduced sample] |

PST-PC N=29 Mean (STD) or % [n if reduced sample] |

Effect Sizea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 62.74 (9.64) | 65.66 (10.14) | t(58)=−1.14, p=0.26 | 0.30 |

| %Female | 77.42 (n=24) | 72.41 (n=21) | χ2(1) = 0.20, p=0.66 | 0.06 |

| %Caucasian | 51.61 (n=16) | 62.07 (n=18) | χ2(1) = 0.67, p=0.41 | 0.11 |

| Education | 14.03 (2.12) | 13.52 (2.64) | t(58)=0.84, p=0.41 | 0.22 |

| Marital

Status %Married/Co-habitating |

45.16 (n=14) |

37.93 (n=11) |

Fisher Exact p=0.08 |

0.34 |

| %Divorced/Separated | 25.81 (n=8) | 13.79 (n=4) | ||

| %Never Married | 16.13 (n=5) | 6.90 (n=2) | ||

| %Widowed | 12.90 (n=4) | 41.38 (n=12) | ||

| % Employed | 35.48 (n=11) | 37.93 (n=11) | χ2(1) = 0.04, p=0.84 | 0.03 |

| Cumulative Illness Rating Scale-Geriatrics | 8.23 (5.21) | 7.34 (3.51) | t(58)=0.76, p=0.45 | 0.20 |

| Rand12 Mental Component |

41.73 (9.48) [n=29] |

44.04 (8.86) [n=25] |

t(52)=−0.92, p=0.36 |

0.25 |

| Physical Component | 41.07

(13.73) [n=29] |

43.60

(10.92) [n=25] |

t(52)=−0.74, p=0.46 | 0.21 |

| Mini Mental Status Exam | 28.48 (1.21) | 27.83 (1.85) | t(58)=1.64, p=0.11 | 0.43 |

| LL-FDI Scaled

Scores Frequency |

49.71 (7.22) [n=28] |

55.38 (6.92) [n=26] |

t(52)=−2.94, p=0.005 |

0.82 |

| Limitation | 66.21

(16.02) [n=28] |

65.92

(11.85) [n=26) |

t(52)=0.08, p=0.94 | 0.02 |

| Instrumental | 65.36

(16.94) [n=28] |

66.27

(13.25) [n=26] |

t(52) = −0.22, p=0.83 | 0.06 |

| Management | 77.64 (20.36) [n = 24] |

74.92 (18.02) [n = 26] |

t(52) = 0.52, p= 0.61 | 0.14 |

| Personal | 62.04 (16.37) [n = 28] |

73.69 (13.58) [n = 26] |

t (52) = −2.84, p = 0.007 | 0.79 |

| Social | 62.04 (16.37) [n = 28] |

49.08 (9.40) [n = 26] |

t(52) = −2.34, p = 0.02 | 0.65 |

| Hamilton Depression Rating Scale | 11.39 (3.03) | 12.17 (4.32) | t(58)=−0.82, p=0.42 | 0.22 |

| Beck Depression InventoryI | 10.74 (5.78) | 10.45 (4.76) | t(58)=0.21, p=0.83 | 0.06 |

| Brief Symptom Inventory- anxiety | 0.52 (0.49) | 0.64 (0.47) | t(58)=−0.94, p=0.35 | 0.25 |

| Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist | 31.89

(10.11) [n=28] |

28.59

(6.37) [n=27] |

t(53)=1.44, p=0.16 | 0.40 |

| Social Problem Solving Inventory Total | 99.79

(11.69) [n=29] |

97.92

(14.07) [n=25] |

t(52)=0.53, p=0.60 | 0.15 |

| Number of sessions | 6.06 (1.18) Range = 1–8 |

5.97

(1.66) Range=1–8 |

Wilcoxon exact p=0.74 | -- |

| Number of boosters | 2.42 (1.09) Range = 0–3 |

2.45 (1.09) Range = 0–3 |

Wilcoxon exact p=0.92 | -- |

Values represent Means (standard deviation) or % (n) [n included if reduced sample]; PST-PC: Problem Solving Therapy - Primary Care; DIET: dietary education; LL-FDI: Late Life Function and Disability Instrument. Statistical methods included student’s t, chi-square, Fisher’s exact test or Wilcoxon exact test.

Cohen’s d effect size reported for the continuous variables and Cramer’s V for the categorical variables.

Figure 1. Recruitment Flow Chart.

This recruitment flow chart indicates that 60 of the randomized 247 individuals were exposed to psychologic trauma. The text box at the bottom describes reasons why some of the 60 participants did not complete. Abbreviations are as follows: PST-PC: Problem Solving Therapy in Primary Care; DIET: dietary education; MMSE: mini mental status examination; CES-D: Centers for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression scale: MDD – major depressive disorder.

The 2 interventions differed on the Late Life Function and Disability Instrument. Specifically, participants randomized to the DIET condition had greater disability in the frequency dimension which includes the LL-FDI frequency personal and social subscales. The personal subscale assesses how well individuals take care of their own personal care needs. The social subscale assesses how well individuals are able to take part in organized social activities (Sayers et al., 2004). There were no other significant baseline or clinical differences between PST-PC and DIET. During the intervention, the number of treatment sessions and booster sessions also did not differ between intervention groups.

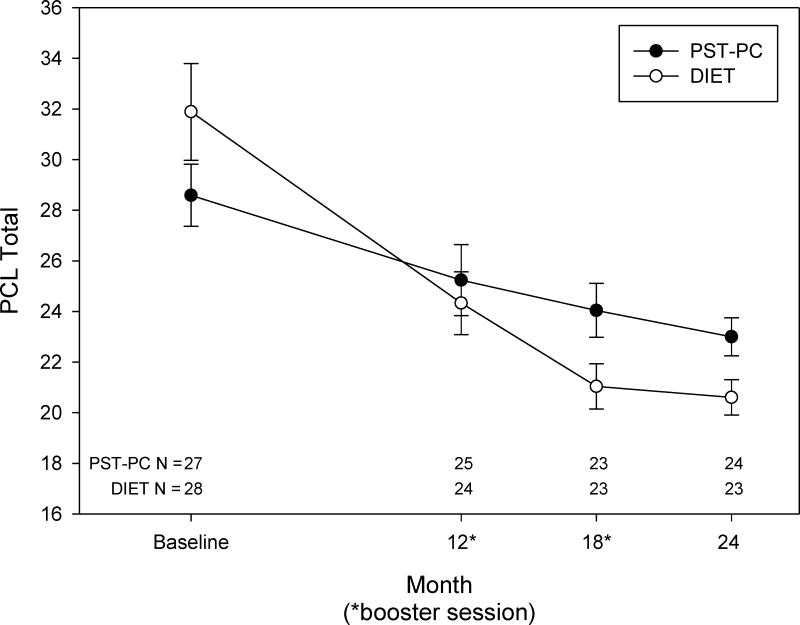

Figure 2 shows the PCL-C scores of the 2 groups over time. When modeling this data, we included LL-FDI frequency scaled scores as a covariate since it differed between groups in the initial univariate analyses. We chose this in lieu of the personal and social role scores since both personal and social role scores contribute to the frequency score. In addition, we included depressive symptom scores as a time varying covariate given that depressive symptoms have been reported to be significantly associated with problem solving skills (Kasckow et al., 2010). We found a significant time effect [linear time: F(1, 131) = 12.42; p < .001] and linear * time intervention interaction [F(1,131) = 6.86; p = 0.01]. Both groups had improvement over time; however participants in the DIET intervention improved more (beta (standard error) = −0.02 (0.02) and −0.05 (0.02), respectively). Over the two year period, we found that, on average, there was an improvement of 6.95 points in the PCL-C score in the DIET group whereas there was only a 1.92 point improvement in the predicted PST-PC group. Depression symptom scores were also a significant covariate. Every one unit increase in Hamilton 17 item depression inventory was associated with a 0.60 point decrease in PCL-C. In addition, the frequency scaled score from the Functional Disability Assessment was also a significant covariate and lead to PCL-C scores decreasing by 0.15 points for every unit increase in that covariate.

Figure 2.

This figure shows the Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Check List scores – Civilian version (PCL-C; mean ± standard error) over time for Problem Solving Therapy in Primary Care (PST-PC) and dietary education (DIET) interventions. The number of participants at each time point is indicated in the bottom portion of the graph. Time was treated as continuous with actual visit date used to model time. The graph shows data plotted at study designed time points for convenience. We found a significant time effect [linear time: F(1, 131) = 12.42, p <.001] and linear time*intervention interaction [ F(1, 131) = 6.86; p = 0.01]. Both interventions showed improvement over time with the DIET intervention decreasing by more. The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (17 Items) and the ‘frequency’ scaled score from the Late Life Function and Disability Instrument were significant covariates. Decreases in PCL scores were associated with decreases in the depression scale scores and increases in the Functional Disability frequency scores.

The VA National Center for PTSD recommends using 5 points as a minimum threshold for determining whether an individual has responded to treatment and 10 points as a minimum threshold for determining whether the improvement is clinically meaningful (http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/pages/assessments/ptsd-checklist.asp). Generally, a 5–10 point difference in PCL-C scores is considered reliable, i.e., not due to chance and a 10–20 point change is clinically meaningful (Monson et al., 2008). Although not statistically significant, the DIET group had more participants meeting definition of clinically meaningful change (52% [95% CI: 14–53%], n = 12/23 vs 30% [95% CI: 31–73%], n = 7/23). The ‘Number needed to Treat’ was 5, i.e., 5 more patients need to be treated with DIET than with PST in order to effect a clinically meaningful level of symptomatic improvement.

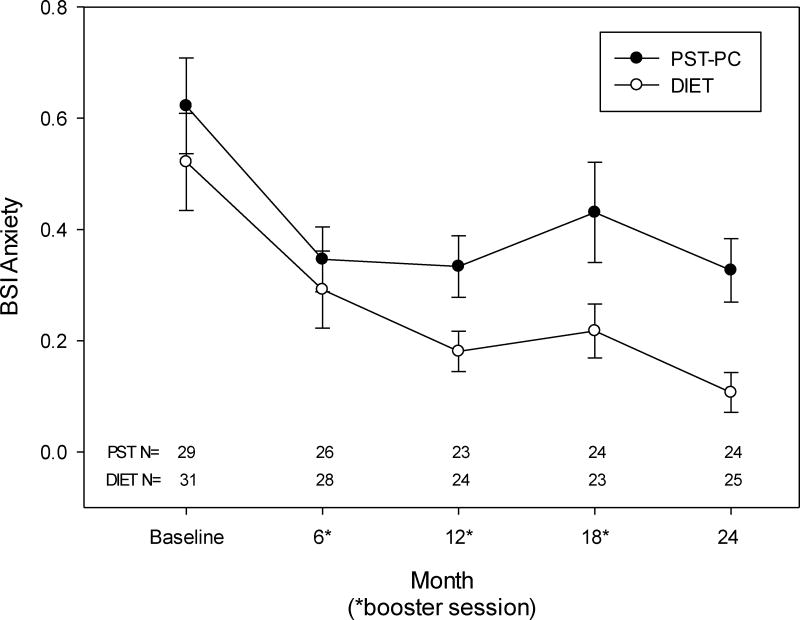

There were no significant differences between groups with respect to SPSI, BDI or BSI-anxiety scores [SPSI treatment*time interaction: F (1,188) = 0.52, p = 0.47; BDI treatment*time interaction: F (1,170) = 0.22, p = 0.64; BSI-anxiety treatment*time interaction: F (1,194) =1.36, p = 0.25); see Figure 3]. However, both groups overall improved in all 3 of these outcomes with an initial improvement that was sustained over the 2 years [SPSI linear time: F(1,188) = 13.89, p <0.001 and quadratic time: F(1,188) = 5.58, p=0.02; BDI linear time: F (1,170 ) = 41.01, p<0.001 and quadratic time: F(1,170) = 17.49, p<0.001; BSI-anxiety linear time: F (1,194) = 19.15, p < 0.001 and quadratic time: F(1, 194) = 8.35, p=0.004]. On average both groups improved approximately 7.1 points in SPSI total, 5.6 points in BDI and 0.29 in BSI-anxiety. Furthermore, the mean (standard deviation) baseline Body Mass Index (BMI) for the participants receiving DIET was 31.4 (7.7) vs 31.8 (7.8) for those receiving PST-PC which was not significantly different [t(58) = −0.19, p=0.85]. There were also no time X treatment interactions when examining BMI as an outcome variable F(1,84 = 0.01, p=0.93).

Figure 3.

This figure shows the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) anxiety scores (mean ± standard error) over time for Problem Solving Therapy in Primary Care (PST-PC) and dietary education (DIET) interventions. The number of participants at each time point is indicated in the bottom portion of the graph. Time was treated as continuous with actual visit date used to model time. The graph shows data plotted at study designed time points for convenience. We found a significant time effect [linear time: F (1, 194) = 19.15, p <.001 and quadratic time: F(1, 194) = 8.35; p = 0.004]. Thus, both interventions showed improvement over time. However, there were no differences in anxiety scores between groups: [F (1, 194) = 1.36; p = .25].

4.0 Discussion

We previously reported that of the 247 individuals who participated in the Depression Prevention trial, 64 (26.2%) experienced a traumatic event; 6 (2.6%) had syndromal PTSD and 14 (6.0%) had subthreshold PTSD (Kasckow et al., 2012). Thus, approximately one in four of our participants had been exposed to a traumatic event and one in 12 of the total sample had either syndromal PTSD or subthreshold PTSD. Our definition of subthreshold PTSD was based on Blanchard et al (1994). Our analysis suggests that PTSD symptoms in participants with subsyndromal depression and a history of psychologic trauma improve more with a dietary education intervention compared to Problem Solving Therapy in Primary Care. Our analysis was based on an intent to treat approach and utilized hierarchical linear models. The effects appear to be specific since there were no significant time by treatment interactions with respect to depressive symptoms, general anxiety symptoms or social problem solving skills. The scale we used to assess anxiety, i.e., the Brief Symptom Inventory scale, mainly assesses symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder.

Treatments for PTSD have been reviewed by Foa et al (2009). Evidence based treatments include prolonged exposure therapy (Joseph and Gray, 2008) in which the therapist guides the client to recall traumatic memories in a controlled fashion. In this way, patients eventually regain mastery of their thoughts and feelings around the incident. Another approach is Cognitive-processing therapy. This is a form of cognitive behavioral therapy that includes an exposure component but places greater emphasis on cognitive strategies to help people alter erroneous thinking which has emerged because of the event (Monson et al., 2006). Another form of cognitive behavioral therapy used to treat PTSD is Stress-inoculation training where practitioners teach clients techniques to manage and reduce anxiety, such as breathing, muscle relaxation and positive self-talk (Lee et al., 2002; Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 2007). There are no current treatments available for subsyndromally depressed individuals with a history of psychologic trauma.

The choice of DIET was endorsed by our Community Research Advisory Board at the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health as one that would be credible and acceptable to potential participants. There was a strong pragmatic rationale for the selection of DIET. It was chosen to be a culturally acceptable active control condition that would facilitate enrollment and retention of participants and was an active intervention in its own right. In this study, it is not known why DIET was associated with a better outcome relative to PST-PC. We are unaware of any studies that have addressed whether dietary education could help improve PTSD symptoms in a similar population of individuals. We wondered whether the DIET group exhibited weight loss and thus had improvements in anxiety symptoms as a consequence; however, there were no differences in Body Mass Index between groups at baseline nor at the end of the intervention. Furthermore, we wondered whether the list of problems examined in individuals receiving PST-PC could have activated traumatic memories and caused increased distress. However, none of the sessions of problem solving involved discussing themes that focused on potential past traumatic events. With the participants involved in dietary education, it is possible that a greater sense of control over a specific health issue led to improvement in PCL-C scores specifically. Furthermore, it is not known whether PST-PC would have been associated with greater improvement in PTSD symptoms if the treatment sessions were specifically focused on PTSD related symptoms rather than depressive symptoms. Finally, there were 4 participants who also received psychotherapy (3 DIET; 1 PST-PC) and there were 11 who were taking antidepressants (5 DIET; 6 PST-PC). We re-ran the regression without those individuals and the results did not change.

There were no differences in overall scores of social problem solving based on the SPSI. The SPSI is a 25-item multidimensional, self-report measure with two major scales which rate problem-solving orientation and problem-solving skills; these skills are addressed and improved through teaching individuals the process of Problem Solving Therapy. Specifically the skills assessed include problem definition and formulation, generation of alternative solutions, decision-making, and solution implementation/verification. The SPSI scores reflect individuals’ positive problem orientation, negative problem orientation, rational problem solving, impulsivity/carelessness style and avoidance style. Potential changes in these various skills can be quantitated by the various subscales of the SPSI. However, we noted no differences at baseline between groups; nor were there any group differences noted in any of the subscales.

The absolute percentages of psychologic trauma and PTSD observable in our sample are lower than that present in primary care clinics (Freuh et al., 2007). However, our group of participants represent a unique subsample of subsyndromally depressed individuals who are seeking treatment and who prefer psychosocial treatment. When one takes into account the large numbers of individuals age ≥ 50 years who present to primary care settings, this sample of subsyndromally depressed individuals represents a significant number of individuals with traumatic exposure. Thus, our findings have important public health implications. Overall, the data are pertinent to integration of primary care and behavioral health services in older adults whose medical comorbidity places them at high risk to the emergence of common mental disorders (depression, anxiety, stress related, such as PTSD).

Our study was limited by sample size. In addition, the narrow range of depressive symptom scores of individuals with subsyndromal depression may have limited the interpretation of the regression results. Another limitation is that the study was designed as a prevention study for people with low levels of depression and not for individuals with PTSD; thus, the PST-PC treatment sessions were not necessarily targeted towards problems related to PTSD symptoms. It is also possible that our significant findings could be a result of performing multiple comparisons; thus the chance of finding a significant finding is higher. The use of a self report measure to index PTSD symptom severity as the primary outcome measure is a limitation of the study as well as the fact that the secondary outcome measures were also all self report measures. Future studies will address potential mechanisms which could possibly account for the improvements in PTSD symptoms that were associated with dietary education.

Acknowledgments

Supported primarily by NIH grants P30 MH090333 (ACISR), P60 MD000207, UL1 TR000005 (CTSI) and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Endowment in Geriatric Psychiatry and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. This trial was registered on Clinical Trials.gov as ID: NCT00326677. Dr. Reynolds has received pharmaceutical supplies from Forest Laboratories, Pfizer, Lilly, and BMS for his NIH sponsored research. Dr. Kasckow has received research grant support from Bosch Health Care.

References

- Alexopoulos GS, Raue P, Arean P. Problem-solving therapy versus supportive therapy in geriatric major depression with executive dysfunction. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2003;11:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Text Revision. 4. American Psychiatric Press; Washington D.C: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Areán P, Hegel M, Unützer J. Problem-Solving Therapy for Older Primary Care Patients: Maintenance Group Manual for Project IMPACT. University of California, Los Angeles; Los Angeles: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Hickling EJ, Barton KA, Taylor AE, Loos WR, Jones-Alexander J. One year prospective follow up of motor vehicle accident victims. Behavior Research and Behavior Therapy. 1994;34:775–786. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, Tenhave TR, Reynolds CF, III, Katz II, Schulberg HC, Mulsant BH, Brown GR, McAvay GJ, Pearson JL, Alexopoulos GS. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Associaton. 2004;291:1081–1091. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.9.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychological Medicine. 1983;13:595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla TJ, Nezu AM. Development and preliminary evaluation of the Social Problem-Solving Inventory. Psychological Assesment. 1990;2:156–163. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, Cohen J. Effective treatments for PTSD. 2. Guilford Press; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Frueh C, Anouk L, Grubaugh A, Acierno R, Elhai J, Cain G, Magruder K. Age differences in posttraumatic stress disorder, psychiatric disorders, and healthcare service use among veterans in veterans affairs primary care clinics. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;15:660–672. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3180487cc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubaugh AL, Magruder K, Waldrop A, Elhai J, Knapp R, Frueh B. Subthreshold PTSD in primary care: prevalence, psychiatric disorders, healthcare use, and functional status. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases. 2005;193:658–664. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000180740.02644.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2007/Treatment-of-PTSD-An-Assessment-of-the-Evidence.aspx.

- Joseph JS, Gray MJ. Exposure therapy for post traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Behavior Analysis of Offender and Victim. Treatment and Prevention. 2008;1:69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Kasckow JW, Brown C, Morse J, Begley A, Bensasi S, Reynolds CF., 3rd PTSD Symptoms in emotionally distressed individuals referred for a depression prevention intervention: Relationship to problem solving skills. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2012;27:1106–1111. doi: 10.1002/gps.2826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasckow JW, Brown C, Morse J, Karpov I, Bensasi S, Thomas S, Ford A, Reynolds C., 3rd Racial preferences for participation in depression prevention in a depression prevention trial involving problem solving therapy. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61:722–724. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.7.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasckow JW, Karp JF, Whyte E, Butters M, Brown C, Begley A, Bensasi S, Reynolds CF., 3rd Subsyndromal depression and anxiety in older adults: health related, functional, cognitive and diagnostic implication. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2013;47:599–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulka R, Schlenger W, Fairbank J, Hough R, Jordan B, Marmar C, Weiss D. Readjustment Study. Brunner/Mazzel; New York: 1990. Trauma and the Vietnam War Generation: Findings From the Nat’l Vietnam Vet. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Gavriel H, Drummond P, Richards J, Greenwald R. Treatment of PTSD: Stress inoculation training with prolonged exposure compared to EMDR. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;58:1071–1089. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyness JM, Kim J, Tang W, Tu X, Conwell Y, King D, Caine E. The clinical significance of subsyndromal depression in older primary care patients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;15:214–23. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000235763.50230.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MD, Paradis CF, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Stack JA, Rifai AH, Mulsant B, Reynolds CF., 3rd Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research. 1992;41:237–248. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90005-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson CM, Gradus JL, Young-Xu Y, Schnurr PP, Price JL, Schumm JA. Change in post traumatic stress disorder symptoms: Do clinicians and patients agree? Psychological Assessment. 2008;20:131–138. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.20.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson CM, Schnurr PP, Resick PA, Friedman MJ, Young-Xu Y, Stevens SP. Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:898–907. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezu A, Carneville G. Interpersonal problem solving and coping reactions of Vietnam veterans with post traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1987;96:155–157. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.96.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oslin DW, Ross J, Sayers S, Murphy J, Kane V, Katz IR. Screening, assessment, and management of depression in VA primary care clinics. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:46–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CF, 3rd, Thomas SB, Morse J, Anderson SJ, Albert SM, Dew MA, Begley AE, Karp JF, Gildengers A, Butters MA, Stack JA, Kasckow JW, Quinn S. Early intervention to preempt major depression in older blacks and whites. Psychiatric Services. 2014;65:765–773. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J, TenHave T, Eakin A, Difilippo S, Oslin D. A randomized controlled trial of a close monitoring program for minor depression and distress. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23:1379–1385. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0663-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscio AM, Ruscio J, Keane TM. The latent structure of posttraumatic stress disorder: a taxometric investigation of reactions to extreme stress. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:290– 301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers S, Jette AM, Haley SM, Heeren TC, Guralnik JM, Fielding RA. Validation of the late-life function and disability instrument. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2004;52:1554–1559. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr P, Spiro A, Paris AH. Physician-diagnosed medical disorders in relation to PTSD symptoms in older male military veterans. Health Psychology. 2000;19:91–97. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland K, Bryant R. Social problem solving and autobiographical posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriwattanakomen R, Ford A, Thomas S, Miller M, Stack J, Morse J, Kasckow JW, Brown C, Reynolds CF., 3rd Preventing depression in later life: Translation from concept to experimental design and pilot implementation. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2008;16:460– 468. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318165db95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriwattanakomen R, McPherron J, Chatman J, Morse JQ, Martire LM, Karp JF, Houck PR, Bensasi S, Houle J, Stack JA, Woods M, Block B, Thomas SB, Quinn S, Reynolds CF., 3rd A comparison of the frequencies of risk factors for depression in older black and white participants in a study of indicated prevention. International Psychogeriatrics. 2010;22:1240–1247. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210001523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EA, Katon W, Russo J, Ciechanowski P, Newman E, Wagner AW. Health care costs associated with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:369– 374. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.4.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J. SF36 Health Survey Boston. The Health Institute; New England Medical Center. Nimrod Press; Boston: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F, Litz B, Herman D, Huska J, Keane T. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, Validity, and Diagnostic Utility. Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; San Antonio, TX. 1993. Oct, [Google Scholar]