Abstract

OBJECTIVE

There are known disparities in endometrial cancer survival with black women who experience a greater risk of death compared with white women. The purpose of this investigation was to evaluate the role of comorbid conditions as modifiers of endometrial cancer survival by race.

STUDY DESIGN

Two hundred seventy-one black women and 356 white women who had been diagnosed with endometrial cancer from 1990–2005 were identified from a large urban integrated health center. A retrospective chart review was conducted to gather information on comorbid conditions and other known demographic and clinical predictors of survival.

RESULTS

Black women experienced a higher hazard of death from any cause (hazard ratio [HR] 1.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.22–1.87) and from endometrial cancer (HR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.63–3.60,). After adjustment for known clinical prognostic factors and comorbid conditions, the hazard of death for black women was elevated but no longer statistically significant for overall survival (HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.94–1.57), and the hazard of death from endometrial cancer remained significantly increased (HR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.39–3.68). Both black and white women with a history of hypertension experienced a lower hazard of death from endometrial cancer (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.23–0.98; and HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.19–0.67, respectively).

CONCLUSION

The higher prevalence of comorbid conditions among black women does not explain fully the racial disparities that are seen in endometrial cancer survival. The association between hypertension and a lower hazard of death from endometrial cancer is intriguing, and further investigation into the underlying mechanism is needed.

Keywords: comorbid condition, endometrial cancer, disease-specific survival, hypertension, racial disparity

Endometrial cancer is the most common malignancy of the female genital tract and is the fourth leading cancer diagnosed in women, after breast, lung, and colon cancers.1 Incidence of endometrial cancer in the United States had been decreasing over the past 3 decades, but recent data show a reversal of that trend, with a 3.0% annual percentage increase from 2006–2010, compared with a negative 0.4% annual percentage change from 1997–2006.2 White women are at greater risk of the development of endometrial cancer than black women; however, black women are more likely to die of this disease. The lower survival rate among black women was identified decades ago, and this disparity has persisted over time.3,4 The mortality rate from endometrial cancer from 2006–2010 for black women was nearly twice the mortality rate of white women (7.4 vs 4.0 per 100,000).2 Although black women are diagnosed with less favorable histologic types, at more advanced stages, and with higher grade tumors than white women,5–8 poorer survival rates are still seen in black women for all stages, grades, and histologic types when compared with their white counterparts.8,9

Reasons for these survival differences are likely due to a combination of factors that include differences in socioeconomic resources, environmental and behavioral risk factors, and tumor biology.5,7,10–12 One factor that has not been evaluated fully is the role comorbid conditions play in the racial disparity in endometrial cancer survival. Black women have a higher prevalence of obesity, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension.13 Although these conditions have been associated with poorer survival rates,14 a recent report with the use of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Medicare data illustrated that comorbid conditions do not account fully for the racial disparity that is seen in endometrial cancer survival in a Medicare population.15 We sought to further evaluate the relationship between comorbid conditions and the racial disparity in endometrial cancer survival among women of all ages at a single institution.

Materials and Methods

After institutional review board approval was obtained, a case-only retrospective analysis of incident endometrial cancer cases (International Classification of Diseases [ICD]-O3 codes of C54.0-55.9) was conducted. Black and white women who were diagnosed from 1990–2005 were identified from the Henry Ford Health System (HFHS) tumor registry. The HFHS is a large, integrated health system in Detroit, MI. The HFHS currently consists of 5 hospitals, 36 ambulatory care facilities, and clinics (that offer free or low-cost care and are located throughout the metropolitan Detroit area) and serves patients of varying levels of socioeconomic and insurance status for both races. Clinical, demographic, risk factor, and survival data were obtained from 3 sources: the HFHS database, medical record abstraction, and the Metropolitan Detroit Cancer Surveillance System (MDCSS) registry, which is part of the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program. The MDCSS ascertainment area encompasses the 3 county (Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb) metropolitan Detroit area, where the majority of patients at HFHS reside.

To standardize data collection, variables were abstracted from the medical record up to 5 years before the endometrial cancer diagnosis. Race information was self-reported and abstracted from the medical record. Comorbid conditions of interest included diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity (body mass index [BMI], ≥30 kg/m2), morbid obesity (BMI, ≥40 kg/m2), and a modified Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). The CCI is a weighed score of comorbid conditions that have been shown to predict death16 and was modified in this analysis to exclude diabetes mellitus (both complicated and uncomplicated), because that condition is an established risk factor for endometrial cancer and thus was evaluated separately. A condition was counted in the CCI if it was diagnosed before the endometrial cancer diagnosis. BMI was calculated from height and weight measurements in the medical record that were documented 2–5 years before diagnosis so that weight measures would not be influenced by any weight loss that was part of the disease process.

Information on known risk factors for endometrial cancer was also abstracted from the medical record. Smoking history was grouped into 3 categories: never smoker, former smoker, and current smoker. Reported parity was evaluated 2 ways: as a dichotomous variable (nulliparous vs parous) and as a categoric variable (nulliparous, 1–3 live births, and ≥4 live births). Histologic classification and grade information were reviewed by the HFHS pathologists (A.R.G. and D.S.) to standardize categorization. All cases were then rereviewed by a Wayne State University gynecologic pathologist (R.A.F.), and any discrepancy was resolved by consensus among the 3 pathologists (A.R.G., D.S., and R.A.F.). Histologic type was grouped into 4 categories: type I, type II, type III, and other. Type I included endometrioid and mucinous adenocarcinoma histologic types; type II included serous, clear cell, and mixed histologic types; type III included malignant mixed Müllerian tumors, and “other” included all other histologic types. Vital status information was obtained from the MDCSS database; follow-up information was obtained through the end of 2012.

Differences in age at diagnosis, International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians stage, grade, histologic type, comorbid conditions, BMI before diagnosis, smoking history, and parity were examined by race. Racial differences in tumor characteristics were examined further, stratified by comorbid conditions. The differences in the distribution of these clinical and demographic variables were assessed with the use of χ2 tests.

Log-rank tests and Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the risk of overall and endometrial cancer– related deaths. Endometrial cancer– related deaths were defined by both the primary and underlying causes of death (ICD-9 codes I79 and I82 and ICD-10 code C54) that were recorded on the death certificate; survival time was calculated from the date of biopsy. Race-specific hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for overall and endometrial cancer–related survival were estimated for each comorbid condition and adjusted for known predictors of survival that were significant in univariate analyses. These predictor variables were age and year at diagnosis, International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians stage, grade, histologic type, and treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy). In addition, an interaction term with race and each comorbid condition was calculated. Overall and disease-specific hazard of death was estimated for black women, as compared with white women, and then estimated after adjustment with the use of 2 different models. Model 1 was adjusted for year and age of diagnosis, receipt of surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and tumor characteristics (stage, grade, and histologic type). Model 2 was adjusted with all the variables listed for model 1 and comorbid conditions (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, and CCI). These analyses were repeated in the subset of women who were treated surgically. All analyses were performed with SAS statistical software (version 9.2; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 627 women, 271 black women (43%) and 356 white women (57%), were identified for inclusion in this study. Compared with their white counterparts, black women were more likely to have aggressive disease phenotypes with higher proportions of type II/ III histologic types and higher grade tumors and were more likely to be diagnosed at a later stage of disease (all P <.001). Black women were less likely to receive surgical treatment (17% vs 4%; P <.001) and more likely to receive chemotherapy (P =.041). Black women were more likely to be diagnosed with hypertension (P <.001) and to be obese (P < .001). CCI (P = .305) and the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (P =.086) were similar in black and white women with endometrial cancer (Table 1). The significant racial differences that were seen in histologic type and grade persisted when they were examined by either the presence or absence of diabetes mellitus, obesity, hypertension, or other comorbid conditions (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Select clinical, demographic, and treatment variables of women diagnosed with endometrial cancer from a single institution by race

| Variable | White (n = 356)

|

Black (n = 271)

|

P valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Age at diagnosis, y | .204 | ||||

|

| |||||

| <50 | 49 | 14 | 32 | 12 | |

|

| |||||

| 50–59 | 71 | 20 | 39 | 14 | |

|

| |||||

| 60–69 | 112 | 31 | 99 | 37 | |

|

| |||||

| 70+ | 124 | 35 | 101 | 37 | |

|

| |||||

| International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians stage | < .001 | ||||

|

| |||||

| I | 246 | 69 | 142 | 52 | |

|

| |||||

| II | 40 | 11 | 32 | 12 | |

|

| |||||

| III | 40 | 11 | 37 | 14 | |

|

| |||||

| IV | 19 | 5 | 45 | 17 | |

|

| |||||

| Unknown | 11 | 3 | 15 | 6 | |

|

| |||||

| Grade | < .001 | ||||

|

| |||||

| I | 189 | 53 | 79 | 29 | |

|

| |||||

| II | 67 | 19 | 35 | 13 | |

|

| |||||

| III | 91 | 26 | 135 | 50 | |

|

| |||||

| Unknown | 9 | 3 | 22 | 8 | |

|

| |||||

| Histologic group | < .001 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Type I | 260 | 73 | 148 | 55 | |

|

| |||||

| Type II | 67 | 19 | 84 | 31 | |

|

| |||||

| Type III | 24 | 7 | 33 | 12 | |

|

| |||||

| Other | 5 | 1 | 6 | 2 | |

|

| |||||

| Modified Charlson comorbidity score | .305 | ||||

|

| |||||

| None | 208 | 58 | 140 | 52 | |

|

| |||||

| 1 | 64 | 18 | 55 | 20 | |

|

| |||||

| ≥2 | 84 | 24 | 73 | 27 | |

|

| |||||

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | |

|

| |||||

| Hypertension | < .001 | ||||

|

| |||||

| No | 151 | 42 | 65 | 24 | |

|

| |||||

| Yes | 205 | 58 | 206 | 76 | |

|

| |||||

| Diabetes mellitus | .086 | ||||

|

| |||||

| No | 275 | 77 | 193 | 71 | |

|

| |||||

| Yes | 81 | 23 | 78 | 29 | |

|

| |||||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | < .001 | ||||

|

| |||||

| <25 | 66 | 19 | 31 | 11 | |

|

| |||||

| 25–29.9 | 91 | 26 | 38 | 14 | |

|

| |||||

| 30–39.9 | 108 | 30 | 119 | 44 | |

|

| |||||

| ≥40 | 76 | 21 | 74 | 27 | |

|

| |||||

| Unknown | 15 | 4 | 9 | 3 | |

|

| |||||

| Smoking history | .590 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Nonsmoker | 223 | 63 | 182 | 67 | |

|

| |||||

| Current | 47 | 13 | 30 | 11 | |

|

| |||||

| Former | 75 | 21 | 55 | 20 | |

|

| |||||

| Unknown | 11 | 3 | 4 | 1 | |

|

| |||||

| Nulliparity | .004 | ||||

|

| |||||

| No | 264 | 74 | 218 | 80 | |

|

| |||||

| Yes | 85 | 24 | 38 | 14 | |

|

| |||||

| Unknown | 7 | 2 | 15 | 6 | |

|

| |||||

| Parity | < .001 | ||||

|

| |||||

| None | 85 | 24 | 38 | 14 | |

|

| |||||

| 1–3 | 186 | 52 | 126 | 46 | |

|

| |||||

| ≥4 | 77 | 22 | 92 | 34 | |

|

| |||||

| Unknown | 8 | 2 | 15 | 6 | |

|

| |||||

| Surgery | < .001 | ||||

|

| |||||

| No | 14 | 4 | 45 | 17 | |

|

| |||||

| Yes | 342 | 96 | 226 | 83 | |

|

| |||||

| Radiation therapy | .686 | ||||

|

| |||||

| No | 225 | 63 | 167 | 62 | |

|

| |||||

| Yes | 131 | 37 | 104 | 38 | |

|

| |||||

| Chemotherapy | .041 | ||||

|

| |||||

| No | 286 | 80 | 199 | 73 | |

|

| |||||

| Yes | 70 | 20 | 72 | 27 | |

|

| |||||

| Vital Status | < .001 | ||||

|

| |||||

| Alive | 164 | 46 | 100 | 37 | |

|

| |||||

| Deceased | |||||

|

| |||||

| Endometrial cancer | 43 | 12 | 66 | 24 | |

|

| |||||

| Other reason | 149 | 42 | 105 | 39 | |

Calculation does not include unknown values.

Ruterbusch. Race, comorbidities, and endometrial cancer survival. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014.

TABLE 2.

Racial differences in the distribution of clinical characteristics by the presence of comorbid conditions

| Variable | Comorbid condition

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absent

|

Present

|

|||||

| White women, % | Black women, % | P value | White women, % | Black women, % | P value | |

| Diabetes mellitus | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Total, n | 275 | 193 | 81 | 78 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Histologic group | < .001 | .051 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Type I | 75 | 56 | 73 | 56 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Type II | 20 | 31 | 16 | 32 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Type III | 6 | 13 | 11 | 12 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Grade | < .001 | .007 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| I | 55 | 31 | 53 | 33 | ||

|

| ||||||

| II | 19 | 14 | 19 | 13 | ||

|

| ||||||

| III | 26 | 55 | 28 | 53 | ||

|

| ||||||

| International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians stage | < .001 | .040 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| I | 71 | 57 | 71 | 51 | ||

|

| ||||||

| II | 13 | 12 | 8 | 14 | ||

|

| ||||||

| III | 11 | 14 | 13 | 15 | ||

|

| ||||||

| IV | 5 | 16 | 8 | 21 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Obesity | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Total, n | 157 | 69 | 184 | 193 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Histologic group | .001 | .006 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Type I | 74 | 50 | 73 | 58 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Type II | 20 | 32 | 19 | 32 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Type III | 6 | 18 | 8 | 10 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Grade | < .001 | < .001 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| I | 54 | 22 | 58 | 36 | ||

|

| ||||||

| II | 19 | 13 | 19 | 15 | ||

|

| ||||||

| III | 27 | 65 | 24 | 49 | ||

|

| ||||||

| International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians stage | .012 | .004 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| I | 74 | 52 | 69 | 60 | ||

|

| ||||||

| II | 8 | 15 | 15 | 12 | ||

|

| ||||||

| III | 12 | 21 | 12 | 11 | ||

|

| ||||||

| IV | 6 | 12 | 5 | 17 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Hypertension | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Total, n | 151 | 65 | 205 | 206 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Histologic group | .116 | .001 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Type I | 77 | 63 | 72 | 54 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Type II | 16 | 26 | 22 | 34 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Type III | 7 | 11 | 6 | 13 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Grade | .004 | < .001 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| I | 53 | 31 | 56 | 32 | ||

|

| ||||||

| II | 21 | 19 | 18 | 13 | ||

|

| ||||||

| III | 26 | 50 | 26 | 56 | ||

|

| ||||||

| International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians stage | .001 | .003 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| I | 72 | 54 | 71 | 56 | ||

|

| ||||||

| II | 12 | 10 | 12 | 13 | ||

|

| ||||||

| III | 10 | 10 | 13 | 16 | ||

|

| ||||||

| IV | 6 | 26 | 5 | 15 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Other comorbid conditions | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Total, n | 208 | 140 | 148 | 128 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Histologic group | .003 | .001 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Type I | 75 | 58 | 73 | 52 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Type II | 19 | 36 | 19 | 28 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Type III | 6 | 7 | 8 | 19 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Grade | .003 | < .001 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| I | 48 | 35 | 64 | 28 | ||

|

| ||||||

| II | 21 | 16 | 16 | 12 | ||

|

| ||||||

| III | 31 | 49 | 20 | 60 | ||

|

| ||||||

| International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians stage | .196 | < .001 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| I | 71 | 64 | 72 | 47 | ||

|

| ||||||

| II | 12 | 12 | 10 | 14 | ||

|

| ||||||

| III | 10 | 11 | 13 | 19 | ||

|

| ||||||

| IV | 6 | 13 | 5 | 21 | ||

The percentages may not total to 100 because of rounding.

Ruterbusch. Race, comorbidities, and endometrial cancer survival. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014.

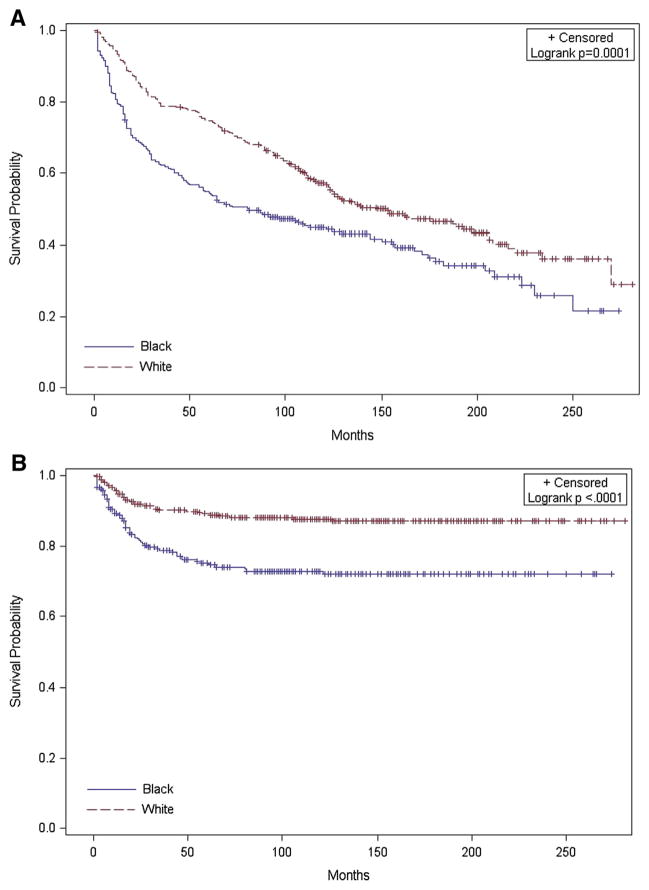

Black women experienced lower overall and disease-specific survival compared with white women (P =.0001 and < .0001, respectively; Figure). The median overall survival for black women was 81 months, compared with 148 months for white women. White women who were diagnosed with diabetes mellitus had a higher hazard of overall death (HR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.13–2.35); black women did not (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.80–1.71). Diabetes mellitus was not associated with an increased risk of death from endometrial cancer for either racial group (Table 3). Black women with hypertension had a lower hazard of overall death (HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.34–0.79); white women with hypertension did not (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.70–1.32; Pinteraction = .008). Both black and white women who were diagnosed with hypertension had a lower hazard of death from endometrial cancer (white women: HR, 0.47; 95% CI 0.23–0.98; black women: HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.19–0.67). Obesity or morbid obesity was not associated with the overall or disease-specific hazard of death for either racial group. For both white and black women, a score of ≥2 on the CCI was associated with a higher hazard of overall death (HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.17–2.50; HR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.46–3.56, respectively), but not for death from endometrial cancer. The hazard of overall death was 51% higher for black women compared with white women and nearly 2.5 times as high for endometrial cancer–related deaths. As seen in Table 4, adjustment for aggressive disease features attenuated the HRs, but the hazard for overall and disease-specific survival remained significantly elevated for black women. After further adjustment for comorbid conditions, the hazard for overall survival remained elevated but was no longer statistically significant, and the hazard of endometrial cancer death remained significantly elevated. When this analysis was limited to women who received surgical treatment (Table 4), the unadjusted hazard for overall and endometrial cancer–related death for black women remained significantly elevated yet appeared to be slightly smaller in magnitude. The same pattern persisted in this subgroup after adjustment for aggressive disease features and comorbid conditions.

FIGURE. Endometrial cancer survival by race.

A, Overall survival; B, disease-specific survival.

Ruterbusch. Race, comorbidities, and endometrial cancer survival. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014.

TABLE 3.

Impact of comorbid conditions on survival in women who were diagnosed with endometrial cancer

| Variable | White women

|

Black women

|

P interaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratioa | 95% confidence interval | P value | Hazard ratioa | 95% confidence interval | P value | ||

| Death from any cause | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.63 | 1.13–2.35 | .009 | 1.17 | 0.80–1.71 | .429 | .302 |

|

| |||||||

| Hypertension | 0.96 | 0.70–1.32 | .817 | 0.52 | 0.34–0.79 | .003 | .008 |

|

| |||||||

| Obesity (body mass index, ≥30 kg/m2) | 1.04 | 0.75–1.43 | .820 | 1.04 | 0.69–1.56 | .865 | .670 |

|

| |||||||

| Morbid obesity (body mass index, ≥40 kg/m2) | 1.33 | 0.86–2.06 | .198 | 1.07 | 0.70–1.63 | .771 | .901 |

|

| |||||||

| Charlson comorbidity score | .991 | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| 1 | 1.89 | 1.24–2.90 | .003 | 1.07 | 0.66–1.72 | .795 | |

|

| |||||||

| ≥2 | 1.71 | 1.17–2.50 | .006 | 2.28 | 1.46–3.56 | < .001 | |

|

| |||||||

| Death from endometrial cancer | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.00 | 0.40–2.49 | .999 | 0.71 | 0.36–1.37 | .302 | .978 |

|

| |||||||

| Hypertension | 0.47 | 0.23–0.98 | .044 | 0.35 | 0.19–0.67 | .001 | .740 |

|

| |||||||

| Obesity (body mass index, ≥30 kg/m2) | 0.89 | 0.44–1.79 | .739 | 0.81 | 0.44–1.51 | .510 | .723 |

|

| |||||||

| Morbid obesity (body mass index, ≥40 kg/m2) | 0.72 | 0.24–2.15 | .557 | 1.04 | 0.53–2.02 | .913 | .760 |

|

| |||||||

| Charlson comorbidity score | .312 | ||||||

|

| |||||||

| 1 | 2.74 | 1.16–6.48 | .022 | 1.10 | 0.51–2.36 | .806 | |

|

| |||||||

| ≥2 | 0.92 | 0.35–2.41 | .864 | 1.97 | 0.98–3.98 | .059 | |

Adjusted for year and age at diagnosis, Federation of International Gynecologists and Obstetricians stage, grade, histologic type, receipt of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy.

Ruterbusch. Race, comorbidities, and endometrial cancer survival. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014.

TABLE 4.

Hazard of death for black women who were diagnosed with endometrial cancera

| Variable | Unadjusted

|

Adjusted

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1b

|

Model 2c

|

|||||

| Hazard ratio for black race (95% confidence interval) | P value | Hazard ratio for black race (95% confidence interval) | P value | Hazard ratio for black race (95% confidence interval) | P value | |

| All cases | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Overall | 1.51 (1.22–1.87) | < .001 | 1.29 (1.02–1.63) | .036 | 1.22 (0.94–1.57) | .134 |

|

| ||||||

| Disease-specific | 2.42 (1.63–3.60) | < .001 | 2.11 (1.35–3.30) | .001 | 2.27 (1.39–3.68) | .001 |

|

| ||||||

| Surgically treated cases | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Overall | 1.39 (1.11–1.75) | .005 | 1.28 (1.00–1.64) | .051 | 1.26 (0.97–1.64) | .082 |

|

| ||||||

| Disease-specific | 2.15 (1.39–3.32) | < .001 | 2.03 (1.27–3.24) | .003 | 2.19 (1.32–3.64) | .002 |

Compared with white women at a single institution;

Adjusted for year and age at diagnosis, Federation of International Gynecologists and Obstetricians stage, grade, histologic type, receipt of chemotherapy, radiation therapy and, in “all cases,” surgery;

Adjusted for year and age at diagnosis, Federation of International Gynecologists and Obstetricians stage, grade, histologic type, receipt of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, obesity, Charlson comorbidity index, and, in “all cases,” surgery.

Ruterbusch. Race, comorbidities, and endometrial cancer survival. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014.

Comment

In this single institution study, racial differences in survival were seen for both overall and endometrial cancer–related survival, with black women having a higher risk of death. Although black women had greater proportions of high-grade tumors with aggressive histologic types, adjustment for these differences did not explain fully all of the racial differences that were seen in survival, nor did adjustment for the presence of comorbid conditions.

Our findings suggest that excess co-morbid conditions do not explain the racial differences that are seen in endometrial cancer survival. This finding supports those findings that were seen in an older population-based sample using SEER/Medicare data.15 When the impact of individual conditions is compared, interesting similarities and differences were found. Like Olson et al, 15 we observed that black women who were diagnosed with hypertension had improved disease-specific and overall survival. White women with hypertension also had improved disease-specific survival, but not improved overall survival. The confirmation of this finding is intriguing. There were no differences seen in stage, grade, or histologic type between normotensive and hypertensive women.

One possible explanation for the association between hypertension and improved survival is the purported beneficial role of drugs that commonly are used in the treatment of hypertension and cancer survival. A recent review by McMenamin et al17 concluded that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers may be associated with improved outcomes in cancer patients. However, there were inconsistent results across studies, and none of the studies that were included in the review were of endometrial cancer. There have been some smaller studies that suggest these drugs may have a role in survival among other gynecologic cancers. In particular, the use of statins and beta-blockers has been shown to be independent prognostic factors in survival of women with epithelial ovarian cancer.18,19

The higher proportion of aggressive tumors among black women persisted when examined by the presence or absence of comorbid conditions. Unlike other cancer sites, for which it has been suggested that comorbid conditions are associated with aggressive tumor types,20–22 it is unlikely that the higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or obesity that is seen among black women accounts for higher proportion of aggressive endometrial tumors.

There are limitations to consider when the results of this analysis are interpreted. All of the data sources were retrospective; although our medical record review lends confidence to the presence of the comorbid conditions, we did not capture information on disease severity or medication use. These factors are likely to be important confounders of the effect of comorbidity and survival. This single-institution study may not represent the larger population but does include a substantial population of black women from a diverse metropolitan region.

The results of this study are supported by data that were gathered from multiple sources. We leveraged the strengths of existing registry data and supplemented known data gaps with medical record abstraction and expert pathologic review. These results add to the body of literature that illustrates racial disparities in endometrial cancer survival between white and black women that are not explained fully by known risk factors. Further work is needed to elucidate the underlying factors of this disparity and to explore the potential mechanisms between hypertension and endometrial cancer survival.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the Institute for Population Studies in Health Assessment, Administration, Services, and Economics, a partnership of the Henry Ford Health System and Wayne State University.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al., editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2010. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: [Accessed April 1, 2013]. Based on November 2012 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill HA, Eley JW, Harlan LC, Greenberg RS, Barrett RJ, 2nd, Chen VW. Racial differences in endometrial cancer survival: the black/white cancer survival study. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:919–26. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(96)00341-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yap OW, Matthews RP. Racial and ethnic disparities in cancers of the uterine corpus. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:1930–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Long B, Liu FW, Bristow RE. Disparities in uterine cancer epidemiology, treatment, and survival among African Americans in the United States. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;130:652–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Setiawan VW, Pike MC, Kolonel LN, Nomura AM, Goodman MT, Henderson BE. Racial/ethnic differences in endometrial cancer risk: the multiethnic cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:262–70. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Randall TC, Armstrong K. Differences in treatment and outcome between African-American and white women with endometrial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4200–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hicks ML, Phillips JL, Parham G, et al. The National Cancer Data Base report on endometrial carcinoma in African-American women. Cancer. 1998;83:2629–37. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19981215)83:12<2629::AID-CNCR30>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright JD, Fiorelli J, Schiff PB, et al. Racial disparities for uterine corpus tumors: changes in clinical characteristics and treatment over time. Cancer. 2009;115:1276–85. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madison T, Schottenfeld D, James SA, Schwartz AG, Gruber SB. Endometrial cancer: socioeconomic status and racial/ethnic differences in stage at diagnosis, treatment, and survival. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2104–11. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherman ME, Devesa SS. Analysis of racial differences in incidence, survival, and mortality for malignant tumors of the uterine corpus. Cancer. 2003;98:176–86. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allard JE, Maxwell GL. Race disparities between black and white women in the incidence, treatment, and prognosis of endometrial cancer. Cancer control. 2009;16:53–6. doi: 10.1177/107327480901600108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fryar CD, Hirsch R, Eberhardt MS, Yoon SS, Wright JD. Hypertension, high serum total cholesterol, and diabetes: racial and ethnic prevalence differences in U.S. adults, 1999–2006. NCHS Data Brief. 2010;36:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicholas Z, Hu N, Ying J, Soisson P, Dodson M, Gaffney DK. Impact of comorbid conditions on survival in endometrial cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2014;37:131–4. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318277d5f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olson SH, Atoria CL, Cote ML, et al. The impact of race and comorbidity on survival in endometrial cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Bio-markers Prev. 2012;21:753–60. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMenamin UC, Murray LJ, Cantwell MM, Hughes CM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers in cancer progression and survival: a systematic review. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:221–30. doi: 10.1007/s10552-011-9881-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diaz ES, Karlan BY, Li AJ. Impact of beta blockers on epithelial ovarian cancer survival. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127:375–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.07.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elmore RG, Ioffe Y, Scoles DR, Karlan BY, Li AJ. Impact of statin therapy on survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:102–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maiti B, Kundranda MN, Spiro TP, Daw HA. The association of metabolic syndrome with triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;121:479–83. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0591-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kheterpal E, Sammon JD, Diaz M, et al. Effect of metabolic syndrome on pathologic features of prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2013;31:1054–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moses KA, Utuama OA, Goodman M, Issa MM. The association of diabetes and positive prostate biopsy in a US veteran population. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2012;15:70–4. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2011.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]