Abstract

Physical function and functional recovery are important aspects of the acute pain experience in children and adolescents in hospitalized settings. Measures of function related to pediatric acute pain do not exist currently, limiting understanding of recovery in youth undergoing acute and procedural pain. To address this gap, we developed and assessed the clinical utility and preliminary validity of the Youth Acute Pain Functional Ability Questionnaire (YAPFAQ). We evaluated psychometric properties of this measure in 159 patients with sickle cell disease, ages 7–21 years who were hospitalized for vasoocclusive episodes at four urban children’s hospitals. The YAPFAQ demonstrated strong internal reliability and test-retest reliability. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to examine the preliminary factor structure, and to help reduce the number of items for the final scale. Evidence for moderate construct validity was demonstrated among validated measures of pain burden, motor function, functional ability and quality of life. The YAPFAQ is a new measure of youth functional ability in the acute pain setting. Further evaluation of this measure in additional pediatric populations is needed to understand applicability across a spectrum of youth experiencing acute pain related to illness, trauma, and medical/surgical procedures.

PERSPECTIVE

Measures of function in response to acute pain are needed in order to more comprehensively evaluate acute pain interventions in pediatrics; however, no specific measures are available. Our preliminary psychometric evaluation of an acute pain functional ability measure for youth indicates that it may be a promising tool for further refinement in additional pediatric acute pain populations.

Keywords: sickle cell disease, pain, functional assessment, adolescents

Introduction

For the child and adolescent in acute pain, the goals of pain assessment are to quantify and observe pain status so that appropriate interventions can be administered and their efficacy evaluated. Guidelines are available for the management of acute pain in general that recommend the use of standard pain measures, and advocate for frequent, repeated documentation of pain assessment as an essential piece of pain management.1, 2, 16, 19 Currently, the standard for pain assessment is a rating of pain intensity, as determined by observation (for younger children) or self-report (for older children and adolescents).

However, the complexity and multidimensional nature of pain requires additional assessment, beyond pain intensity, to better understand affective and emotional factors associated with pain, and physical and functional recovery.8, 9, 15 The suggested core outcome domains recommended by the Pediatric Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (Ped-IMMPACT) include the assessment of physical recovery in pediatric acute pain management trials. Recognizing that a gap currently exists in this aspect of pediatric pain measurement, the group identified the need for development of new measures of physical function and recovery for children experiencing acute pain.14

Measures of function associated with acute pain and hospitalization would allow for the 1) examination of the impact of acute pain on usual function in the immediate recovery period, 2) investigation of the extent to which acute pain symptoms create a burden for caretakers, 3) description of changes in children’s functioning as the result of acute pain interventions, and 4) study of individual differences in functioning within specific patient groups experiencing acute pain in the hospital.3, 25 Available measures of functional disability in youth assess areas such as impairment in sleep, activity, and communication, as well as mood and well-being due to chronic or recurrent pain experienced at home.8, 9, 15 There are several well-validated functional assessment and quality of life scales that are routinely used in pain assessment in youth with chronic and recurrent pain, including the Functional Disability Inventory (FDI),25 the Child Activities Limitations Interview (CALI),17 and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL).22 These tools are valid in the outpatient setting and are useful to evaluate functional change in patients with chronic and recurrent pain over weeks to months in the ambulatory setting. These measures are not, however, appropriate to use in the inpatient hospital setting, because the items represent aspects of function that are not pertinent in this setting (e.g., going to school, playing with friends).

Unfortunately, functional assessment tools suitable for youth experiencing acute pain in the hospitalized setting do not exist. This represents a significant gap in scientific knowledge and has limited our ability to comprehensively measure response to therapeutic interventions and to evaluate functional recovery occurring during hospitalization or shortly after hospital discharge. The purpose of this study was to develop and then assess preliminary psychometric properties of the Youth Acute Pain Functional Ability Questionnaire (YAPFAQ) for children and adolescents experiencing acute pain in the hospital. We conceptualized functional ability as those routine activities required for daily tasks (physical, social, activities of daily living), either in the inpatient medical setting or in the immediate recovery period at home. We hypothesized that the YAPFAQ would demonstrate strong reliability as defined by adequate internal consistency and test-retest reliability. We also hypothesized a multidimensional factor structure of the YAPFAQ, given the multiple domains that are represented by functional recovery. We expected construct validity to be demonstrated by moderate associations between YAPFAQ scores and other related constructs, specifically quality of life, functional ability, and motor function.

Materials and Methods

Tool Development

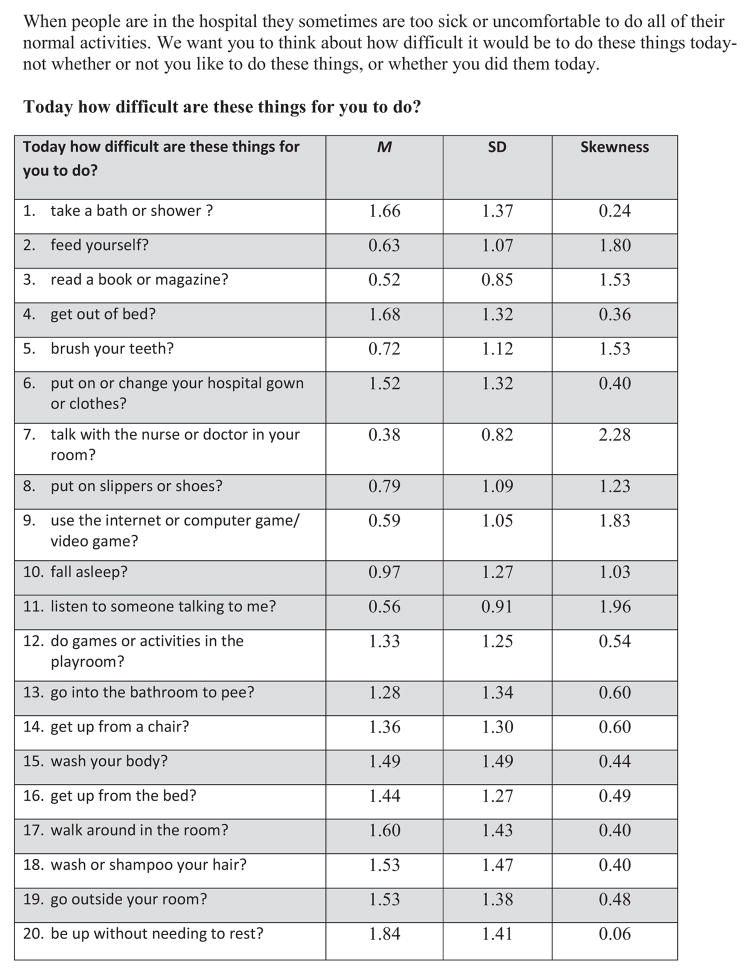

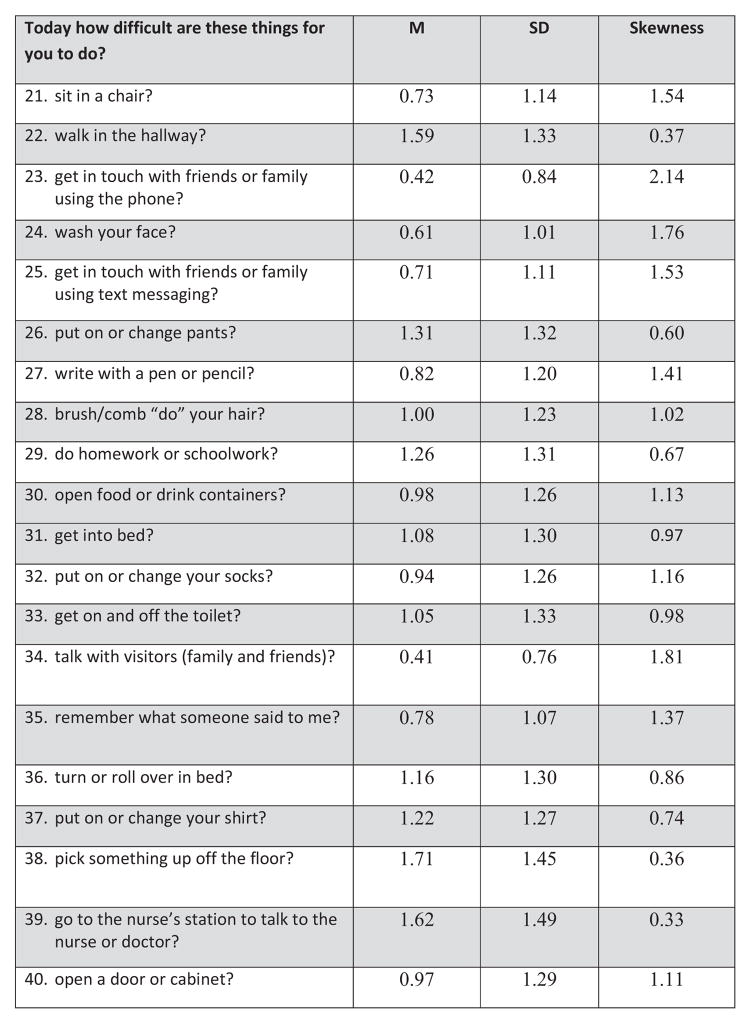

The YAPFAQ was developed as a self-report measure of physical function in youth experiencing acute pain. An initial draft of the YAPFAQ was devised from review of the literature on functional assessment in pediatric pain, input from an interdisciplinary group (hematology and rehabilitation nurse, physicians from hematology rehabilitation and pain, child psychologist, child life specialist, physical therapist) of experts in pain and functional assessment, and review of potential items by youth hospitalized with acute pain. As a result of this review, the items were revised and then tested among 15 hospitalized youth experiencing acute pain to evaluate their understanding of the instructions, question stems, and individual items. Youth at each stage of scale development recommended changes in wording, clarifications, and removal of certain items that were not appropriate. Readability was maintained under the 3rd grade reading level. From this field testing, a preliminary version of the YAPFAQ was established. The initial instrument consisted of 40 items for which subjects were asked to rate their perception of difficulty of various functional and self-care activities on a scale ranging from “not difficult” to “extremely difficult” to perform each activity. These 40 items are shown in Figure 1. A self-report scale (rather than an observational scale) was desired to increase flexibility and ease of use in the clinical setting.

Figure 1. Youth Acute Pain Functional Ability Questionnaire—40 original items.

When people are in the hospital they sometimes are too sick or uncomfortable to do all of their normal activities. We want you to think about how difficult it would be to do these things today- not whether or not you like to do these things, or whether you did them today.

Given the potential difficulty that youth may have in discriminating whether functional limitations occur specifically due to pain (versus for other reasons), we used a generic stem to ask youth to report their perceived difficulty performing each activity. We expect that many of the perceived limitations in activities are directly due to pain itself. However, in medical populations, we recognize that hospitalization for pain involves a variety of experiences that may also impact functional recovery. Thus, the interpretation of the YAPFAQ should also be broad in encapsulating functional recovery.

Participants

For the initial validation of this measure, subjects with sickle cell disease (SCD) experiencing an acute vasoocclusive pain episode (VOE), ages 7–21 years, were recruited from inpatient units at four different urban children’s hospitals located on the eastern coast of the United States. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to subject recruitment for each of these centers including Connecticut Children’s Medical Center (CCMC), Johns Hopkins Hospital, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), and Children’s Hospital of Atlanta (CHOA). Inclusion criteria included documented history of SCD, English-speaking, primary diagnosis of vasoocclusive episode, and parental consent if necessary. Patients were excluded who had significant cognitive impairments that limited ability to consent and/or complete study measures.

Of the 171 patients approached for the study, 12 patients were excluded from enrollment due to the following: an acute chest episode (N=5), outside the age criteria (N=2), incomplete data collection (N=4), and previously enrolled (N=1). As a result, 159 youth were included in the final sample (93%). Of our sample, 48 were recruited from CCMC, 21 from John Hopkins Hospital, 49 from CHOA, and 41 from CHOP. Specific demographic information can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Information on Study Sample (n = 159)

| Age M (SD) R | 15.73 (3.63) 7.26 – 21.82 |

| Gender % (N) | |

| Male | 44.7% (71) |

| Female | 55.3% (88) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Black or African-American | 86.0% (135) |

| Hispanic | 5.7% (9) |

| SCD type | |

| HbSS | 67.7% (107) |

| HbSC | 21.5% (34) |

| HbSBeta+−thalassemia | 7.0% (11) |

| HbSBeta0−-thalassemia | 3.8% (6) |

| Long-term Therapy | |

| Hydroxyurea | 42.7% (67) |

| Chronic Transfusion | 13.3% (21) |

M-mean, SD-standard deviation, N-number, R-range

Procedure

Participants with SCD who were admitted into the hospital for VOE were approached within 72 hours of admission for possible study participation. Written consent was obtained for all study participants. When a legal guardian was not physically present, verbal consent was obtained via phone prior to written consent. After consent was obtained, the participant was asked to complete measures of physical activity, pain impact, pain location, and quality of life. All measures were administered between 3 pm and 5 pm on the day of study entry. A subset of participants (10%) was randomly assigned to complete the CAPFAQ two hours later to examine test-retest reliability. Given the nature of acute pain, we chose to assess test-retest reliability again two hours after initial administration of the measure. While patients may have had recall of their initial responses over this short time period, the potential for actual functional change over longer time periods led us to choose this reassessment time period. When reading assistance was required, research personnel assisted in the completion of study measures with participants.

Measures

General Information Form

Participants completed a general information form that included information regarding disease symptoms (i.e., days of pain over the past month), and current medications (i.e., pain, sleep, and psychotropic medication) and treatment interventions (i.e., physical therapy, occupational therapy).

Average Pain Intensity

Inpatient nurses collected the patient’s self-report of pain intensity on an 11-point numeric rating scale (NRS) throughout the patient’s hospitalization. The average pain score within 24 hours of completing baseline measures was computed and used to represent the average pain intensity score in the subsequent analyses. Scores range between 0–10.

Youth Acute Pain Functional Ability Questionnaire (YAPFAQ)

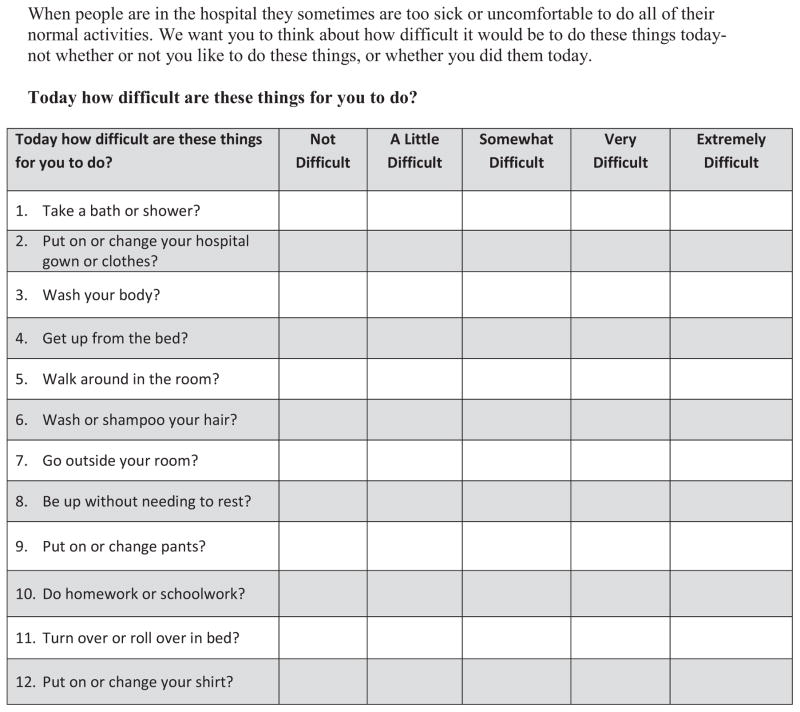

The YAPFAQ was developed for the current study. The instrument consisted of a stem, “today how difficult are these things for you to do?”, and the patient rated his or her level of difficulty performing each activity during the day using a 5-point Likert scale (0 = Not difficult, 1 = A little difficult, 2 = Somewhat difficult, 3 = Very difficult, 4 = Extremely difficult). Example items include getting up from the bed, taking a shower or bath, and turning in bed. Scores range between 0–48 for the final 12 items. Higher scores indicate greater difficulty performing functional activities. The original 40 items are shown in Figure 1 and the final version of the measure is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Youth Acute Pain Functional Ability Questionnaire-Final 12 items.

When people are in the hospital they sometimes are too sick or uncomfortable to do all of their normal activities. We want you to think about how difficult it would be to do these things today- not whether or not you like to do these things, or whether you did them today.

Functional Independence Measure (FIM) (motor domain only)

The FIM is an 18-item measure that assesses motor and cognitive capacity. The motor domain consists of 13 items that assess self-care, sphincter control, transfers, and locomotion. Each item was given a score between 1 and 7, where “1” indicated that the patient needed “total assistance” to perform the particular activity and “7” indicated that the patient had “complete independence” with that activity.6 Total scores range between 7 and 91. The FIM has been validated and utilized among many different populations within a variety of settings.7, 24 In a previous study by our group, physical function as measured by the motor component of the FIM improved over the course of hospital stay in 25 youth with SCD.29

Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool (APPT)

The APPT is a multidimensional tool used to assess location and surface area of body pain as reported by the patient. It has been validated in youth ages 8 to 18 years. The participant colored areas of his or her body on a picture of a body outline to indicate location and surface area of pain.20 APPT was scored by counting the number of body locations that were colored in at least 25% using the body outline diagram as described in Jacob et al.,12 with scores ranging from 0–43. This measure has been used previously in youth with SCD pain and body surface area colored in has been shown to decrease over the course of hospitalization.10, 12 Concurrent validity and test-retest reliability have been supported within pediatric pain populations.21

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL), Acute version

The PedsQL, acute version is a 23-item measure of health-related quality of life within the domains of physical, emotional, social and school functioning within the past seven days.2, 22, 23 Scores range from 0–100, with higher scores representing better quality of life. We used the child and teen version of the assessment, which has been validated among children 8–18 years of age. This scale has been widely used among SCD populations.

Sickle Cell Pain Burden Interview Youth (SCPBI-Y)

The SCPBI-Y is a seven-item interview evaluating level of burden due to pain over the last month in various areas of physical and psychosocial function.28 Responses are obtained on a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater difficulty or pain burden and ranging between 0–28. Each participant was asked these questions in an interview format. The SCPBI was developed and validated within inpatient and outpatient pediatric SCD populations ages 7–21 years.28

Child Activity Limitations Interview (CALI)

The CALI is a 21-item assessment of children’s function in the context of recurrent or chronic pain.16 Participants were asked to rate how difficult or bothersome certain activities (i.e. going to school, gym, playing with friends, housework) were because of pain over the past month on a 5-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicate greater difficulty performing functional activities and scores range from 0–84. The CALI has been validated in 8–18 year old individuals and has demonstrated strong psychometric properties in various pediatric health conditions, including SCD.17

Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 20 and STATA 12.0. We examined item properties of the 40 original items on the YAPFAQ. Nineteen items with limited distributions were removed from further analyses. On the remaining 21 items, we conducted exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to explore whether an item was strongly and differentially correlated with latent subscales (factors). EFAs were conducted using iterated principal axis factoring, as this method allows factors to correlate, thereby producing a more accurate, reproducible solution.5 In selecting a factor structure, we used criteria that eigenvalues were ≥ 1.0 4 and approximately 60% of variance was explained (Yang, 2005).26 In addition, the initial scree plot was used to determine the initial number of factors to retain. Based on this, EFAs were conducted on different model variants to test the superiority of each and inform selection of a final model. Given that factors demonstrated weak correlations, orthogonal (varimax) rotation was deemed to be the most appropriate rotation method.

For each EFA, items were only retained if they had a primary factor loading of >.40. Items cross-loading on more than one factor but that had factor loading values that were twice the other were retained. Based on these criteria, we systematically removed items one at a time and repeated the analysis. Each prior analysis informed decisions about which items to subsequently remove. Items were removed until clean solutions were attained, defined as primary factor loadings that were >.40 and primary loadings that were at least double secondary loadings. Final clean solutions for all tested models were then examined to determine the superiority of each based on interpretability and overall accounted variance.

Construct validity was evaluated through Pearson correlations assessing the relationship between YAPFAQ scores and measures of pain burden, HRQOL, motor activity, and activity limitations. We set a liberal criterion for construct validity of only moderate-sized correlations (r’s > .30) because the function measures available (with the exception of the FIM) were primarily developed and validated in samples of youth with pain in the outpatient setting and have very different response timeframes (e.g., one month) in comparison to the CAPFAQ. Because there are no available measures of function in the inpatient setting for use in validation of the CAPFAQ we were restricted in our examination of construct validity. In addition, we examined the relationship between pain (intensity and surface area) and functional recovery given its relevance to interpretation of the measure.

In order to assess internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha was computed on the final retained items of the YAPFAQ. Test-retest reliability was assessed via Pearson’s correlation coefficient between baseline testing and repeated testing two hours later among the random sample completing this assessment. Last, to explore individual differences in YAPFAQ scores by patient demographics, we examined age and gender differences using t-tests and Pearson correlations.

Results

Factor Analysis

We conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using a varimax rotation to assess preliminary factor structure of the YAPFAQ and to produce a shortened scale with higher clinical utility. The EFA with iterated principal component extraction method resulted in 4 factors with eigenvalues above 1.0 and 73% variance explained. The scree plot was suggestive of a 2-factor model. Thus, 4-, 3-, and 2-factor models were tested and contrasted based on interpretability. Based on examination of KMO/Bartlett’s communalities, total variance accounted for, and interpretability, the cleanest solution was achieved with a 2-factor solution. Next, we removed items one-by-one that had significant cross loadings and removed conceptually redundant items to achieve a shortened scale. The final solution contained 12 items on two conceptually-meaningful factors: 1) Activities of daily living (n = 8 items), and Movement (n= 4 items). This final solution explained 65% of the variance, with the following distribution of percentage of variance explained by each factor: 1) 40.67%, 2) 24.30%. The final solution did not contain any cross-loading items and all items had primary factor loadings of ≥ .50. Factor loadings from the final model are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Factor loadings for final YAPFAQ item solution.

| YAPFAQ item | Factor 1 (activities of daily living) | Factor 2 (movement) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Take a shower or bath | 0.830 | 0.176 |

| 2. Put on or change your hospital gown or clothes | 0.813 | 0.258 |

| 3. Wash your body | 0.837 | 0.242 |

| 4. Get up from bed | 0.465 | 0.760 |

| 5. Walk around in the room | 0.378 | 0.774 |

| 6. Wash or shampoo your hair | 0.646 | 0.358 |

| 7. Go outside your room | 0.411 | 0.761 |

| 8. Be up without needing to rest | 0.014 | 0.751 |

| 9. Put on or change pants | 0.704 | 0.419 |

| 10. Do homework or schoolwork | 0.581 | 0.150 |

| 11. Turn or roll over in bed | 0.652 | 0.258 |

| 12. Put on or change your shirt | 0.790 | 0.217 |

Reliability

Internal consistency for each of the factor-derived scales was excellent/good (Factor 1: α = .91; Factor 2: α = .84). Internal consistency for the YAPFAQ full scale was excellent at α = .92.

Test-retest reliability was assessed using a subset of participants (N=20) who repeated the CAPFAQ two hours after initial administration. Strong test-retest reliability was found using a Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r = 0.82, p < 0.001).

Validity

Preliminary construct validity was determined by assessing the relationships between YAPFAQ scores and other measures of functional limitations used in the outpatient setting, including the PedsQL, CALI-21, SCPBI-Y, and FIM. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 3 and correlations are presented in Table 4. As hypothesized, moderate relationships were found (r’s > .30), indicating that higher scores on the YAPFAQ total score (greater functional limitations) were associated with greater difficulty in activities, lower motor function, and lower quality of life. YAPFAQ factor scores showed a similar pattern of findings with most relationships also meeting criterion (r’s > .30) for demonstrating construct validity. Average pain intensity and pain body surface area were associated with YAPFAQ total and factor scores although the correlations were small (r’s < .30).

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics on study measures

| M (SD) | Observed Range | |

|---|---|---|

| YAPFAQ | 17.56 (11.95) | 0–46.23 |

| Average Pain | 5.86 (2.14) | 0–9.80 |

| CALI-21 | 23.96 (17.56) | 0–70.41 |

| PedsQL (Total) | 61.65 (17.05) | 14.13–100.00 |

| SCPBI-Y | 10.53 (5.53) | 0–23.00 |

| APPT | 6.40 (7.24) | 0–39.00 |

| FIM | 56.65 (15.23) | 21.00–91.00 |

Table 4.

Correlations between YAPFAQ and Average Pain, PedsQL, CALI-21, SCPBI-Y, APPT, and FIM.

| Average Pain | APPT | PedsQL | CALI-21 | SCPBI- Y | FIM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YAPFAQ - Total | .18 | .27 | −.41 | .30 | .36 | −.35 |

| YAPFAQ – Factor 1 | .13 | .23 | −.39 | .24 | .33 | −.36 |

| YAPFAQ – Factor 2 | .24 | .28 | −.36 | .36 | .32 | −.24 |

Note. Validity criterion r > .30

Individual differences

Analyses demonstrated that age was significantly related to the total YAPFAQ score (r=−.28, p<0.001) and Factor 1 (Activities of daily living) score (r=−.35, p < .0001), with increasing age being associated with fewer functional limitations. Age was not related to Factor 2 (Movement) scores. There were no sex differences on total YAPFAQ or factor scores.

Discussion

Multidimensional pain assessment is important in order to provide optimal care to children and adolescents with acute pain. The PedIMMPACT statement recommends the consideration of six outcome domains in acute pain clinical trials in children and adolescents.14 These domains include not only evaluation of pain intensity, but also patient satisfaction, physical recovery, emotional response, adverse events, and economic factors.14 Currently, there are no available measures to evaluate physical recovery in youth with acute pain, nor is there a large body of research to understand the functional recovery of youth experiencing acute pain.

There are, however, physical function measures that have been validated across a number of chronic pain conditions, namely the Functional Disability Inventory (FDI),25 and the Child Activities Limitation Interview (CALI-21).16, 17 However, while these measures are useful in understanding functioning in youth with chronic and recurrent pain conditions, they were not developed to consider the range of functional activities likely impacted during acute pain events in the hospital setting. In addition, these measures require a reporting time frame of four weeks, which is not appropriate for assessment of acute pain in the hospital setting.

This study presents the development and preliminary validation of the YAPFAQ; the first self-report questionnaire designed to assess physical function in children and adolescents with acute pain in the hospital setting. In an exploratory factor analysis we found that a two-factor solution yielded the best fit with factors representing movement and self-care. The YAPFAQ also demonstrated strong internal and test-retest reliability, supporting our hypotheses. Future studies are needed that provide multiple pain assessments during the day and in response to pain interventions in order to understand the course of physical recovery and responsiveness of the YAPFAQ in youth with acute pain.

Preliminary empirical support for construct validity was also examined. Because there were no available measures of function in the inpatient setting for use in validation of the YAPFAQ we were restricted in our examination of construct validity to using measures that were developed in outpatient samples with longer response periods (e.g., 4 weeks). This is in contrast to the daily functional assessment obtained by the YAPFAQ during acute hospitalization for pain. However, YAPFAQ scores were associated in the expected direction with measures of motor function, activity limitations, pain burden, and quality of life.

There were only small correlations found between YAPFAQ scores and measures of pain. Our findings regarding pain intensity and function are similar to our previous work where low level associations were also identified between pain and function in hospitalized patients.29 That said, prior studies have shown that pain intensity and pain body surface area decrease over the course of hospitalization in youth with SCD (e.g., Jacob and colleagues12; Zempsky and colleagues29). However, there has been limited understanding of the relationship between functional change and pain during acute inpatient hospitalization. In the ambulatory setting, others have demonstrated the lack of direct correspondence between functional disability and pain in pediatric pain populations.8, 15 In patients with SCD, in particular, clinicians have noted discrepancies between patient behavior and pain scores 11, 18, 19 Our findings build on this literature and demonstrate the importance of evaluating functional outcomes in addition to pain intensity in the acute setting. We also wish to highlight that the YAPFAQ should be interpreted broadly as a measure of functional recovery that is appropriate to use in populations experiencing acute pain but that the measure does not try to isolate function specifically due to pain itself. Hospitalization for acute pain involves a variety of experiences in different medical populations and thus functional recovery is also impacted by multiple factors in addition to pain.

Our preliminary validation focused exclusively on youth with SCD hospitalized with vasoocclusive pain. Given that pain intensity scores often remain elevated during hospitalization in youth with SCD,27 use of multidimensional pain measures to understand the pain experience in this patient population is essential. One of our previous studies demonstrated that physical function improves over the course of hospital stay in youth with SCD.29 However, the functional measure used in this study, the FIM was developed for youth in rehabilitation settings and is cumbersome, requiring specialized training to administer. The YAPFAQ was developed with the goal of increased clinical utility in mind and we believe we have achieved this in a brief 12-item self-report tool.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Our sample consisted of an older adolescent and ethnically homogeneous sample, and thus, these results may not generalize to younger children with SCD, more ethnically diverse samples, or other pain populations. Moreover, additional validation studies are needed to determine the applicability of the YAPFAQ to other populations of youth hospitalized for acute pain (i.e. post-operative pain). Specifically, further validation of the instrument is necessary in other populations (e.g., postsurgical) to examine how the measure performs (e.g., whether or not similar factor structures emerge) and whether the measure is sensitive to change. Although the mean score of the YAPFAQ is in the bottom 1/3 of the range, it is unclear whether other pediatric pain populations would achieve a similar or different range of scores. However, issues related to potential floor effects will need to be carefully considered in further psychometric evaluation of the measure. In addition, we have thus far only examined the YAPFAQ at a single point in time and thus do not know if the measure is sensitive to change. Last, we performed both item selection and preliminary validation within the same sample and thus there was increased bias in our psychometric evaluation of the YAPFAQ.

As mentioned, a key issue to address in future studies of the YAPFAQ is the sensitivity to change over time in addition to change related to pain intervention. In addition, the ideal reporting time frame for evaluating function in the acute pain setting is unknown. Given the potentially fluid nature of acute pain, the appropriate time period to assess function in this clinical setting likely extends from “right now” up to no more than 24 to 48 hours. In our study, we asked patients to assess their functional difficulty “today” and timed the assessment to occur in the afternoon. This procedure allowed the patient a reasonable time period to consider completion of the various functional activities so that the measure could be administered at a standard time once daily. However, the optimal frequency of functional assessment during hospitalization remains an important empirical question. While the YAPFAQ was designed as a self-report measure, observation could also be used to evaluate functional status in hospitalized patients with pain. Moreover, a parent report version of the instrument would also increase flexibility in potentially using proxy reporting. There may be patient populations for which self-report will not be appropriate during hospitalization such as populations that are too ill to respond or youth who have cognitive limitations. Establishing correlations between patient self reports and staff observations may also be important.

While there are a number of clinical assessments that are available for medical personnel to assess acute pain intensity in children, there are none that specifically address function. The YAPFAQ has demonstrated utility as a brief measure that clinicians can use to assess the impact of acute pain on physical function, broadening understanding of the pain experience of youth with acute pain. Although it will require further study, our preliminary findings suggest that functional ability in the hospitalized patient with vasoocclusive pain can be measured by the YAPFAQ. In the future, such an assessment could be built into care plans to guide clinical practice for youth hospitalized with vasoocclusive pain.

Linking function with interventions, be they pharmacologic, behavioral or physical, may lead to better care of youth hospitalized with pain. Future research should examine the YAPFAQ in youth with other acute pain conditions and evaluate its longitudinal sensitivity as well as extend its use to the outpatient environment and home.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was made possible through funding from the National Institute of Health (K-23 HL090832) and the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation awarded to WZ. Dr. Casella has received an honorarium and travel expenses in the past and presently receives salary support through Johns Hopkins for providing consultative advice to Mast Pharmaceuticals (previously Adventrx Pharmaceuticals) regarding a proposed clinical trial of an agent for treating vasoocclusive crisis in sickle cell disease. He is also an inventor and a named party on a patent and licensing agreement to ImmunArray for a panel of brain biomarkers for the detection of brain injury.

Footnotes

Disclosures

While no conflict with the current study is perceived, this information is presented in the spirit of full disclosure.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.American Academy of Pediatrics, American Pain Society. The assessment and management of acute pain in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatr. 2001;108:793–797. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandow AM, Brousseau DC, Pajewski NM, Panepinto JA. Vaso-occlusive painful events in sickle cell disease: Impact on child well-being. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;54:92–97. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Claar RL, Walker LS. Functional assessment of pediatric pain patients: Psychometric properties of the Functional Disability Inventory. Pain. 2006;121:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costello AB, Osborne JW. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2005;10:7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox BJ, Swinson RP, Parker JDA, Kuch K, Reichman JT. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Fear Questionnaire in panic disorder with agoraphobia. Psychol Assessment. 1993;5:235–237. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deutsch A, Braun R, Granger C. The Functional Independence Measure (FIM Instrument) and the Functional Independence Measure for Children (WeeFIM Instrument): Ten years of development. Crit Rev Physical Rehabil Res. 1996;8:267–281. [Google Scholar]

- 7.DiScala C, Grant CC, Brooke MM, Gans BM. Functional outcome in children with traumatic brain injury: Agreement between clinical judgment and the Functional Independence Measure. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;71:145–148. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199206000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eccleston C, Jordan AL, Crombez G. The impact of chronic pain on adolescents: A review of previously used measures. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31:684–697. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eccleston C, Jordan A, McCracken LM, Sleed M, Connell H, Clinch J. The Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire (BAPQ): Development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of an instrument to assess the impact of chronic pain on adolescents. Pain. 2005;118:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franck LS, Treadwell M, Jacob E, Vichinsky E. Assessment of sickle cell pain in children and young adults using the Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23:114–120. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benjamin LJ, Dampier CD, Jacox AK, Odesina V, Phoenix D, Shapiro BS, Strafford M, Treadwell M. Guideline for the Management of Acute and Chronic Pain in Sickle Cell Disease. American Pain Society; Glenview, IL: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacob E, Miaskowski C, Savedra M, Beyer JE, Treadwell M, Styles L. Changes in intensity, location, and quality of vaso-occlusive pain in children with sickle cell disease. Pain. 2003;102:187–193. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00374-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laurent J, Catanzaro S, Joiner TE, Rudolph KD, Potter KI, Lambert S, Osborne L, Gathright T. A measure of positive and negative affect for children: Scale development and preliminary validation. Psychol Assessment. 1999;11:326–338. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGrath PJ, Walco GA, Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Brown MT, Davidson K, Eccleston C, Finley GA, Goldschneider K, Haverkos L, Hertz SH, Ljungman G, Palermo T, Rappaport BA, Rhodes T, Schechter N, Scott J, Sethna N, Svensson OK, Stinson J, von Baeyer CL, Walker L, Weisman S, White RE, Zajicek A, Zeltzer L. Consensus statement: Core outcomes domains and measures for pediatric acute and chronic/recurrent pain clinical trials: PedIMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9:771–783. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palermo TM. Impact of recurrent and chronic pain on child and family daily functioning: A critical review of the literature. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2000;21:58–69. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200002000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palermo TM, Lewandowski AS, Long AC, Burant CJ. Validation of a self-report questionnaire version of the Child Activity Limitations Interview (CALI): The CALI-21. Pain. 2008;31:644–652. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palermo TM, Witherspoon D, Valenzuela D, Drotar D. Development and validation of the Child Activity Limitations Interview: A measure of pain-related functional impairment. Pain. 2004;109:461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Platt A, Eckman JR, Beasley J, Miller G. Treating sickle cell pain: An update from the Georgia Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center. J Emerg Nurs. 2002;28:297–303. doi: 10.1067/men.2002.125268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rees DC, Olujohungbe AD, Parker NE, Stephens AD, Telfer P, Wright J. Guidelines for the management of the acute painful crisis in sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2003;120:744–752. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Savedra MC, Holzemer WL, Tesler MD, Wilkie DJ. Assessment of postoperation pain in children and adolescents using the Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool. Nursing Res. 1993;42:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tesler MD, Savedra MC, Holzemer WL, Wilkie DJ, Ward JA, Paul SM. The word-graphic rating scale as a measure of children’s and adolescents’ pain intensity. Res Nurs Health. 1991;14:361–371. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770140507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varni JW, Seid M, Rode CA. The PedsQL™: Measurement model for the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory. Med Care. 1999;37:126–139. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199902000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL™ 4.0: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ Version 4.0 Genetic Core Scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001;39:800–812. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voll R, Krumm B, Schweisthal B. Functional Independence Measure (FIM) assessing outcome in medical rehabilitation of neurologically ill adolescents. Int J Rehabil Res. 2001;24:123–131. doi: 10.1097/00004356-200106000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walker LS, Greene JW. The Functional Disability Inventory: Measuring a neglected dimension of child health status. J Pediatr Psychol. 1991;16:39–58. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/16.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang B. Factor Analysis Methods. In: Swanson RA, Holton EF III, editors. Research in Organizations: Foundations and Methods in Inquiry. Berrett-Koehler Publishers; San Francisco: 2005. pp. 181–199. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zempsky WT, Loiselle KA, McKay K, Blake GL, Hagstrom NJ, Schechter NL, Kain ZN. Retrospective evaluation of pain Assessment and treatment for acute vasoocclusive episodes in children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:265–268. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zempsky WT, O’Hara EA, Santanelli JP, Palermo TM, New T, Smith-Whitley K, Casella JF. Validation of the Sickle Cell Pain Burden Interview- Youth. J Pain. 2013;14:975–982. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zempsky WT, Palermo TM, Corsi JM, Lewandowski AS, Zhou C, Casella JF. Daily changes in pain, mood, and physical function in children hospitalized for sickle cell pain. Pain Res Manag. 2012;18:33–38. doi: 10.1155/2013/487060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]