Abstract

Signaling through the G protein-coupled kinin receptors B1 (kB1R) and B2 (kB2R) plays a critical role in inflammatory responses mediated by activation of the kallikrein-kinin system. The kB2R is constitutively expressed and rapidly desensitized in response to agonist whereas kB1R expression is upregulated by inflammatory stimuli and it is resistant to internalization and desensitization. Here we show that the kB1R heterodimerizes with kB2Rs in co-transfected HEK293 cells and natively expressing endothelial cells, resulting in significant internalization and desensitization of the kB1R response in cells pre-treated with kB2R agonist. However, pre-treatment of cells with kB1R agonist did not affect subsequent kB2R responses. Agonists of other G protein-coupled receptors (thrombin, lysophosphatidic acid) had no effect on a subsequent kB1R response. The loss of kB1R response after pretreatment with kB2R agonist was partially reversed with kB2R mutant Y129S, which blocks kB2R signaling without affecting endocytosis, or T342A, which signals like wild type but is not endocytosed. Co-endocytosis of the kB1R with kB2R was dependent on β-arrestin and clathrin-coated pits but not caveolae. The sorting pathway of kB1R and kB2R after endocytosis differed as recycling of kB1R to the cell surface was much slower than that of kB2R. In cytokine-treated human lung microvascular endothelial cells, pre-treatment with kB2R agonist inhibited kB1R-mediated increase in transendothelial electrical resistance (TER) caused by kB1R stimulation (to generate nitric oxide) and blocked the profound drop in TER caused by kB1R activation in the presence of pyrogallol (a superoxide generator).

Thus, kB1R function can be downregulated by kB2R co-endocytosis and signaling, suggesting new approaches to control kB1R signaling in pathological conditions.

Keywords: Kinin B1 and B2 receptor, G protein-coupled receptor, endocytosis, heterologous desensitization, heterodimer, clathrin-coated pit, caveolae

1. Introduction

The kinin B1 (kB1R) and B2 (kB2R) G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are primary mediators of the wide variety of physiological and pathological responses attributed to the kallikrein-kinin system (1, 2). The kB2R is selectively activated by the peptides bradykinin (BK) or kallidin (KD; Lys-BK) cleaved from kininogen precursors by plasma or tissue kallikrein (1, 2). BK or KD are inactivated as kB2R agonists by removal of their C-terminal Arg by plasma carboxypeptidase (CP) N (3, 4) or membrane CPM (5–7) but the metabolites generated, des-Arg9-BK (DABK) or des-Arg10-KD (DAKD), are instead specific agonists of the kB1R (2, 8, 9). Typically, the kB2R is constitutively expressed in a variety of cell types in contrast to the kB1R whose expression is induced by injury or inflammation (1, 2). However, kB1Rs are constitutively expressed in some cells (2, 10) and kB2R expression can be enhanced by inflammatory cytokines (2, 11). Thus, under inflammatory conditions typically required to activate the kallikrein-kinin system, both receptors would likely be coexpressed in cells to generate downstream responses.

A large body of evidence shows that the kB1R and kB2R play important roles in the cardiovascular system, including regulation of blood pressure, ischemic pre- and postconditioning, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and diabetic cardiomyopathy (12). Although signaling from the kB1R or kB2R predominates in some conditions, in many cases both receptors stimulate the same responses. For example, both the kB1R and kB2R are involved in the hypotensive response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide injection as blood pressure decreased markedly in wild-type and kB2R−/− mice and moderately in kB1R−/− mice, but was unaffected in kB1R/kB2R double knockout mice (13). kB1R and kB2R are both important for heart development as kB2R knockout led to cardiac hypertrophy, left ventricular (LV) remodeling and microvascular deficits (14, 15), while kB1R knockout resulted in greater LV diastolic chamber dimension, LV mass and myocyte size (16). kB1R or kB2R knockout led to a reduction or loss of myocardial ischemic postconditioning (17) and kB1R or kB2R activation caused vasodilation in conductance and resistance coronary vessels of conscious dogs (18). Both kB1R and kB2R signaling enhanced arteriogenesis after femoral artery occlusion in mice and rats, with the role of kB1Rs being more pronounced (19). kB1Rs and kB2Rs are also protective in renal ischemia/reperfusion injury (20) and kB1R/kB2R double knockout increased nephropathy, neuropathy and bone mineral loss in Akita diabetic mice (21). Finally, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, drugs extensively used to treat hypertension and various cardiovascular and renal diseases exert many of their therapeutic effects by activating kB1Rs and kB2Rs via a variety of mechanisms (22–24).

Functional studies have shown that that there is crosstalk between kB1R and kB2R signaling, consistent with possible formation of heterodimers. For example, in a prostate cancer cell line, both kB1R and kB2R agonists enhanced ERK activation and cell growth and a kB1R antagonist blocked the effect of a kB2R agonist and vice versa (25). Furthermore, in a hypoxic mouse heart model, kB1R agonist-induced angiogenic sprout formation was abolished in kB2R−/− mice (24). The first cellular and biochemical studies supporting direct kB1R/kB2R interactions showed that kB1R expression induced proteolysis of the kB2R and loss of kB2R binding sites on the cell surface, resulting in heterodimers of intact kB1R and proteolytic fragments of kB2R. This interaction increased basal and agonist-stimulated kB1R signaling (26). In contrast, a recent paper, published after completion of most of our studies, provided evidence for cell surface kB1R/kB2R heterodimers that reduced agonist-induced kB1R signaling by stabilizing kB1R expression on the cell surface (27).

In the present study, we show that kB1R and kB2R heterodimerization plays an important functional role in regulating kB1R desensitization and internalization. Typically, the kB2R is rapidly desensitized, which depends on its phosphorylation (28) and endocytosis (29), but kB1Rs do not undergo significant desensitization or internalization (2, 30). We found that, when co-expressed with the kB2R, kB1Rs undergo rapid, kB2R-dependent heterologous desensitization that depends upon both kB2R endocytosis and functional kB2R signaling. This resulted in almost complete loss of kB1R-mediated effects on barrier function when human endothelial cells were pre-treated with kB2R agonist for 10 min. These findings uncover an important mechanism to regulate proinflammatory kB1R signaling, which could be more pronounced and prolonged in the absence of the kB2R.

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Materials

Low-glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), HAM’s F-12 medium (F12) and DMEM/F12 were obtained from GIBCO/Life Technologies. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was from Atlanta Biologicals. Methyl-β-cyclodextrin (M-β-CD), bradykinin (BK), des-Arg9-bradykinin (DABK), des-Arg10-kallidin (DAKD), HOE-140 (HOE), des-Arg9 -HOE-140 (DAHOE), carbachol, 4-Amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine (PP2), thrombin and polylysine were from Sigma. Kallidin (KD) was from Bachem. DL-2-mercaptomethyl-3-guanidinoethylthiopropanoic acid (MGTA) was from Calbiochem. Fura-2/AM was from Molecular Probes. Anti-caveolin-1 monoclonal antibody was from BD Biosciences. Anti-kB2R goat polyclonal antibody (sc-15050) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Rabbit anti-goat IgG, and goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG conjugated-HRP were from Sigma and Pierce respectively. [3H]-BK was from Amersham Biosciences. [3H]-DAKD was from PerkinElmer. [3H]-Arachidonic acid ([3H] AA) and myo-[3H]inositol were from American Radiolabeled Chemicals, Inc. Common chemicals were from Fisher Scientific.

2.2. Cells

Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells and Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were from the American Type Culture Collection and bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells (BPAEC) were from Genlantis. HEK293 cells and BPAEC were maintained in DMEM containing 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 10% (HEK293) or 15% (BPAEC) FBS. CHO cells were maintained in F-12 medium containing 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 10% FBS. Primary human lung microvascular endothelial cells (HLMVEC) from Lonza were cultured in T-25 or T-75 Flasks coated with 0.1% gelatin in Endothelial Cell Basal Medium (EBM®-2, Lonza) supplemented with EGM®-2 SingleQuots® kit (Lonza) and 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals). Cells between passage 3 and 6 were used for assay.

2.3. Generation of receptor constructs

The cDNA for human kinin kB1R was a gift from Dr. Fredrik Leeb-Lundberg (University of Lund, Sweden) and kB2R cDNA was from Syntex Co. Wild type (wt) kB1R and kB2R were cloned into pcDNA3 or pcDNA6 (Invitrogen) for expression in mammalian cells. kB1R was also cloned into pIRES (Clontech) at the Nhe I/Xho I sites, together with EGFP at the Sal I/Not I sites, for coexpression of kB1R and green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the same cells (9). C-terminally tagged kB1Rs or kB2Rs were generated by amplifying kB1R or kB2R cDNA using PCR and then cloned into pEGFP-N1and pECFP-C1 (Clontech) for kB1R-GFP and kB1R-cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) or cloned into pcDNA6 for kB2R-DsRed, both at the Nhe I/Bam HI restriction sites. kB2R-yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) was generated as described (31). kB2R-T342A and kB2R-Y129S were generated by site-directed mutagenesis using pcDNA6 plasmids with the kB2R cDNA sequence. Dominant-negative β-arrestin-2 (residues 284–409) was generated using an approach similar to that described by Orsini and Benovic (32) using human β-arrestin-2 cDNA. All the PCR fragments used were amplified using high fidelity Taq DNA polymerase. Constructs were verified by DNA sequencing performed by the DNA Services Facility of the Research Resources Center, University of Illinois at Chicago.

2.4. Transfection and establishment of stable cell lines

HEK293 cells, at 70–80% confluence in 6-well plates, were transfected with SuperFect (Invitrogen) reagent containing 5 μg DNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 48 h, cells were transferred to selective medium containing G418 (500 μg/ml) or blasticidin (5 μg/ml) based on the resistance gene in the vector. The cells were cultured for 15–30 days in selective medium, and then diluted for single clone selection. For kB1R and kB2R selection, the increase in intracellular calcium stimulated by their specific agonist (DAKD or BK, respectively) was evaluated for each clone (8, 9). HEK293 cells stably expressing kB1R were transfected with wtkB2R, kB2R-T342A, kB2R-Y129S or kB2R-DsRed, cultured for 15–30 days and then diluted for kB2R selection. Each clone was evaluated by stimulating with agonists as above except for kB2R-Y129S, which was selected by ligand binding and Western blotting. The cDNA of kB2R-YFP was transfected into CHO cells, and the appropriate clones were selected in HAM’s F-12 medium supplemented with blasticidin (5μg/ml). Cells that highly expressed YFP were separated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting with an Elite ESP cell sorter (Coulter Corp.). The function of kB2R-YFP was confirmed by measuring the arachidonic acid generation after stimulation with BK (31). CHO cells stably expressing kB2R-YFP were transfected with kB1R-CFP, and cultured in appropriate selective media. Highly expressing YFP and CFP cells were sorted for kB2R-YFP and then kB1R expression and function were determined by ligand binding assay and arachidonic acid release respectively.

2.5. Measurement of intracellular Ca2+

Increases in intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) were measured using fura-2/AM (8, 9). HEK293 cells stably expressing kB1R and kB2R or BPAEC were grown on polylysine-coated glass coverslips to 80% confluence, and then loaded with 2 μM fura-2/AM for 60 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed and then stimulated with kB1R or kB2R agonists as indicated and the fluorescence emission at 510 nm was monitored after excitation at 340 and 380 nm using a PTI Deltascan microspectrofluorometer. Area under the calcium response curve was integrated using Origin 8.0 software (OriginLab Corporation). Dose-response curves were generated by plotting the log of the dose versus the area under the calcium response curve using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software.

2.6. Density gradient centrifugation

Cells stably expressing kB1R-GFP and kB2R-DsRed were scraped into PBS and then centrifuged at 1000 g for 5 min at 4 °C. The cell pellets were lysed and used to make a detergent-free lipid raft preparation by OptiPrep density gradient centrifugation as described (9). Fractions of 0.7 ml (17 total) were collected from the gradient and kB1R-GFP and kB2R-DsRed were measured by fluoresce spectroscopy with excitation/emission wavelengths of 395/510 and 558/583 nm respectively. The data are expressed as percent of total fluorescence. To determine caveolin-1 distribution in the gradient fractions, aliquots were mixed with 10x concentrated RIPA buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% protease inhibitor cocktail) in a 9:1 ratio, sonicated for 15 s and then analyzed by Western blotting.

2.7. Western blotting

Cell lysates or aliquots of gradient fractions in RIPA buffer were sonicated for 30 s on ice. After centrifugation at 14,000 g for 10 min, the supernatant was collected and boiled with 2x concentrated loading buffer for 5 min. The protein samples were separated on an 8% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane. The blots were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS with 0.5% Tween-20 (PBST) for 2 h at room temperature. The membranes were washed with PBST and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Anti-rabbit, anti-goat or anti-mouse peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were added to the membranes at a dilution of 1:3000 and incubation was continued for 1.5 h at room temperature. The bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce).

2.8. Phosphoinositide turnover assay

Phosphoinositide (PI) turnover was determined as previously described (33, 34) with slight modification. Cells at ~ 80% confluence in 12-well plates were labeled for 18 – 24 h with 1 μCi/ml of myo-[3H]inositol in DMEM with 2% dialyzed FBS. After loading, the cells were preconditioned with 15 mM LiCl for 60 min at 37 °C, then stimulated with kinin agonists for the indicated times at 37 °C followed by termination with 0.5 ml of ice-cold 20 mM formic acid. After 30 min on ice, the supernatant was combined with another 0.5 ml of 20 mM formic acid, alkalinized with 0.2 ml of 3% NH4OH solution and then applied to an AG 1-X8 anion exchange column. The column was washed with 2 ml of 20 mM formic acid, 4 ml of 50 mM NH4OH solution, and then 4 ml of 40 mM ammonium formate containing 0.1 M formic acid. After washing, inositol triphosphate (IP3) was eluted using 5 ml of buffer containing 2 M ammonium formate and 0.1 M formic acid. The radioactivity of IP3 was determined in Beckman liquid scintillation counter after adding 10 ml of scintillation fluid.

2.9. Determination of arachidonic acid release

Arachidonic acid release was measured according to a protocol previously described with modifications (29, 33). Briefly, cells at ~80% confluence were cultured for 18–24 h in growth medium containing 0.1% FBS and 1 μCi/ml [3H]arachidonic acid. After loading, cells were washed three times with HAM’s/F12 buffer (10.6 g/L HAM’s/F12, 6 g/L HEPES, 1.6 g/L NaHCO3 and 0.1% (w/v) fat-free BSA), and then incubated in HAM’s/F12 buffer containing receptor agonist as indicated at 37 °C. The medium was collected and [3H]arachidonic acid released was measured in a Beckman liquid scintillation counter.

2.10. Binding and endocytosis assay

kB2R internalization was determined as previously described by Prado et al. with slight modification (33, 35). Briefly, confluent monolayers of HEK293 cells stably expressing kB1Rs and kB2Rs in 24-well plates were rinsed three times with warm PBS and incubated with 1 μM BK or KD or DAKD for 10 min at 37 °C. The cells were washed once with acidified DMEM (pH 2.0) for 5 min, and then washed twice with ice cold PBS. After washing, cells were incubated with 1 nM [3H]BK or 4 nM [3H]DAKD for 90 min on ice, then washed three times with ice cold PBS. Cells were lysed in 0.4 ml of 0.2 M NaOH and transferred to a scintillation vial and counted in a Beckman liquid scintillation counter. The internalization of kB1R or kB2R was calculated as: Fractional endocytosis = (Total binding − residual binding)/Total binding. Total binding = [3H]BK or [3H]DAKD bound to cells incubated with PBS alone. Residual binding = [3H]BK or [3H]DAKD bound to cells pre-treated with cold agonists and then washed by acidified medium.

For binding assays, the cells were incubated with 1 nM [3H]BK or 4 nM [3H]DAKD for 90 min on ice without pretreatment with cold agonists.

2.11. Disruption of caveolae or clathrin-coated pits

Caveolae were disrupted using cholesterol depletion by incubating cells with 10 or 20 mM methyl-β-cyclodextrin, a cholesterol chelator, for 30 min at 37 °C. Clathrin-coated pits were disrupted using by hypertonic medium, potassium depletion or acidification of the cytosol. For hypertonic medium, cells were incubated with HBSS containing 0.45 M sucrose or 0.225 M NaCl for 15 min at 37 °C (36, 37). For potassium depletion, cells were incubated with diluted DMEM (1:1 dilution in H2O) for 5 min, then incubated in potassium-free buffer (1 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, pH 7.3) for 20 min (38). For acidification of cytosol, cells were incubated with HEPES-buffered DMEM (pH 7.2) containing 30 mM NH4Cl for 30 min at 37 °C followed by 5 min (37 °C) in potassium-amiloride buffer (0.14 M KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM amiloride HCl, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.2) (36, 37).

2.12. Confocal microscopy and measurement of fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)

Fluorescence imaging and FRET analysis were performed using an LSM 510 confocal microscope as previously described (9). Cells were grown on polylysine-coated glass coverslips, and fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde. For fluorescence imaging, excitation/emission wavelengths were 458/ 485 ± 30 nm for CFP, 514 nm/545 ± 30 for YFP, 488/510 ± 15 nm for GFP and 543/605 ± 30 nm for DsRed. For FRET, selective photobleaching of YFP was performed by repeatedly scanning a region of the specimen with the 514 nm wavelength set at the maximum intensity to photo bleach at least 85% of the original acceptor fluorescence. For determination of FRET efficiency in the selected bleach area, the average pixel intensity (I) of the CFP signal was determined from the unmixed pre- and post-bleach images using Zeiss software. Relative FRET efficiency was calculated as (1 − [CFP Ipre-bleach/CFP Ipost-bleach]) ×100%.

2.13. Determination of transendothelial electrical resistance

Endothelial monolayer permeability was assessed by measuring transendothelial electrical resistance (TER) as described (8, 39). Briefly, HLMVEC grown to confluence on 10 μg/ml fibronectin-coated gold electrodes (ECIS cultureware 8W10E) were cytokine-treated (5 ng/ml IL-1β, 100 U/ml IFN-γ for 16 h) and then placed in fresh EBM-2 medium supplemented with 1 % fetal bovine serum for 1 h. Electrodes were mounted in the Electric Cell-substrate Impedance Sensing Module 1600R (ECIS, Applied Biophysics) and baseline TER was allowed to stabilize. For experiments using BK, HLMVEC were pretreated for 10 min with 40 μM MGTA to block carboxypeptidase conversion of BK to des-Arg9-BK. Cells were pretreated without or with 100 nM BK for 10 min and then stimulated with 100 nM DAKD or vehicle, alone or combined with 200 μM pyrogallol (superoxide generator) and TER was recorded.

2.14. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SE. For two group comparison, Student’s t-test was used. The ANOVA was used for more than two group comparisons, which was followed by Tukey’s Test to identify the difference between groups (GraphPad Prism 5.0). Values of p< 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Heterodimerization of kinin B1 and B2 receptors

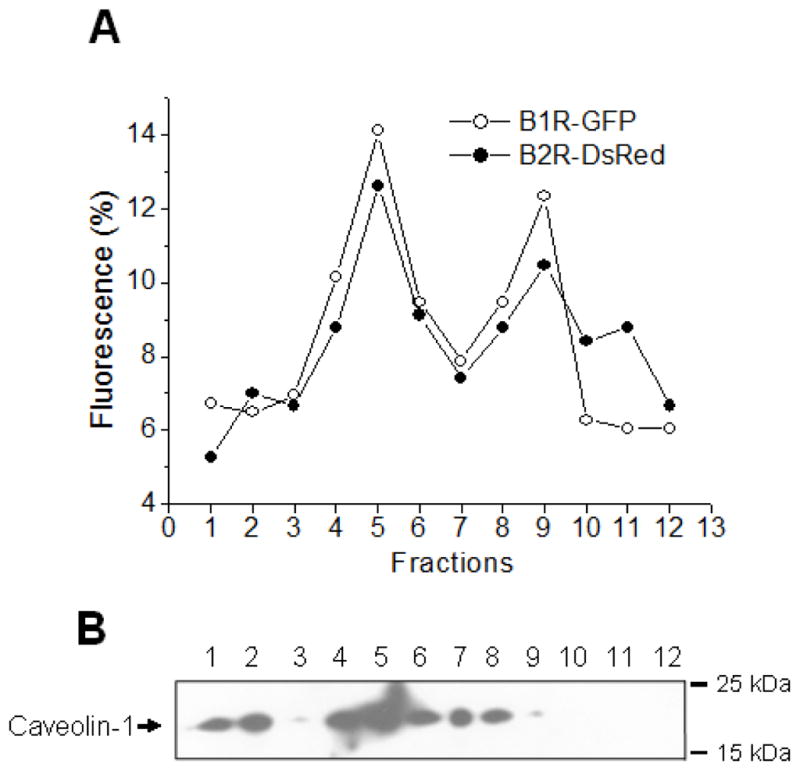

It is well accepted that G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) can form homo- or hetero- dimers/oligomers. To address whether kB1R and kB2R heterodimerize, we first investigated the co-localization of the receptors. As shown in Fig. 1A, we found that kB1R-GFP and kB2R-DsRed exhibited the same distribution on OptiPrep density gradients of membranes prepared by a detergent-free procedure. Both kB1R and kB2R distributed into two peaks (Fig. 1A); one corresponding to fractions enriched in caveolin-1, representing caveolae and lipid raft domains (Fig. 1B) and one in higher density fractions that likely represents non-lipid raft membranes (Fig. 1B). This distribution of kB1Rs and kB2Rs is consistent with our and other previous investigations (9, 40).

Figure 1. Interaction between kB1R and kB2R.

A. The subcellular distribution of kB1R and kB2R was assessed in HEK cells stably expressing kB1R-GFP and kB2R-DsRed. Cells were lysed under detergent-free conditions and lysates were used for OptiPrep density gradient centrifugation. kB1R-GFP and kB2R-DsRed in collected fractions were quantified by fluorescence as described in Methods. B. The distribution of caveolin-1 in the gradient fractions was determined by Western blotting. The data are representative of three experiments in A and B. C. FRET was determined in CHO cells stably expressing kB1R-CFP and kB2R-YFP using acceptor photobleaching as described in Methods. The insets show a 4X magnification of the photobleached areas. The pictures are representative examples from 9 experiments. D. FRET between kB1R-CFP and kB2R-YFP was detected in a florescence spectrophotometer. CFP was excited at 430 nm and the emission from 490 to 600 nm was recorded in CHO cells stably expressing kB1R-CFP and kB2R-YFP or in control cells expressing kB1R-CFP alone. The traces are representative of three experiments.

Florescence (Förster) resonance energy transfer (FRET) has been extensively used to investigate the dimerization/oligomerization of GPCRs. We used acceptor photobleaching (41) to measure FRET in CHO cells stably expressing kB1R-CFP and kB2R-YFP. CFP emission fluorescence was increased after photobleaching the YFP acceptor at 514 nm (Fig. 1C) with a calculated FRET efficiency of 33.2 ± 4.3% (n=9). Also, when measured in a spectrofluorometer, excitation of CFP at 430 nm resulted in a peak of emission fluorescence at 530 nm (corresponding to YFP emission) in CHO cells stably expressing kB1R-CFP and kB2R-YFP, but not in CHO cells expressing equal amounts of kB2R-CFP alone (Fig. 1D). These data indicate that kB1R and kB2R are close enough to exhibit FRET, consistent with heterodimer formation when they are coexpressed.

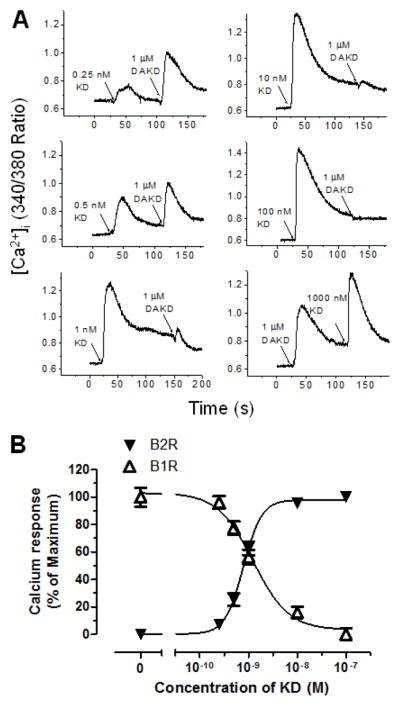

3.2. kB2R activation downregulates the kB1R response

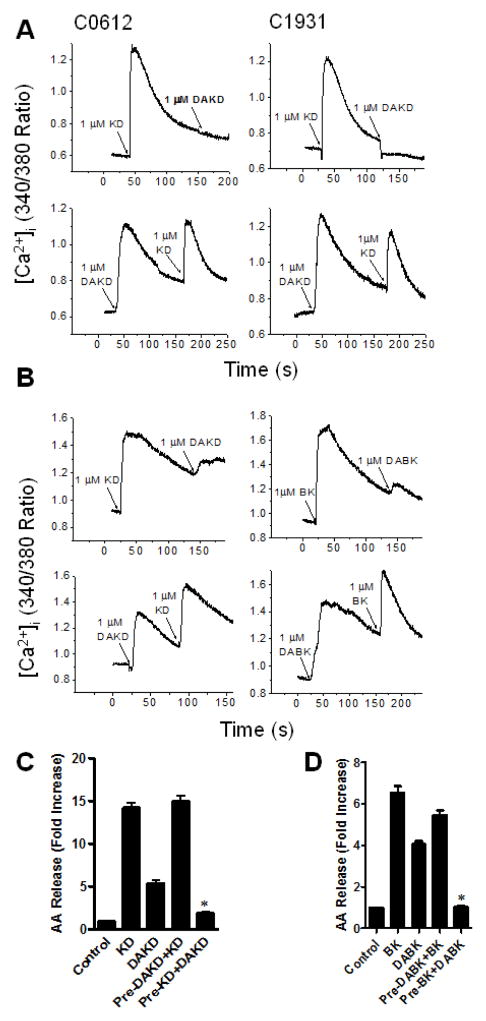

HEK cells stably expressing kB1R and kB2R exhibited a robust calcium response after stimulation with either kB2R agonist KD or kB1R agonist DAKD (Fig. 2A). However, after first stimulating an increase in [Ca2+]i with 1 μM KD, addition of 1 μM DAKD gave no response (Fig. 2A). In contrast, when cells were stimulated first with 1 μM DAKD, addition of 1 μM KD caused a second robust increase in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 2A). Similar results were obtained in two different clones stably expressing kB1R and kB2R (Fig. 2A). To prove that this was not an over-expression artifact, we carried out similar experiments in primary bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells (BPAEC) that natively express both kB1R and kB2R (10). As in the transfected HEK cells, initial stimulation with kB2R agonists BK or KD almost completely inhibited the increase in [Ca2+]i induced by a second stimulation with kB1R agonists DABK or DAKD in BPAEC, but stimulation with kB1R agonists first did not inhibit the calcium response triggered by subsequent addition of kB2R agonists (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. kB1R signaling is downregulated after pre-treatment with kB2R agonist.

A. HEK cells stably expressing kB1R and kB2R were stimulated with kB1R agonist DAKD or kB2R agonist KD followed by addition of KD or DAKD and the increase in [Ca2+]i was measured as described. The data from two typical clones (C0612 and C1931) are shown and are representative of 3 experiments. B. Bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells that natively co-express kB1R and kB2R were stimulated with kB2R agonists (KD or BK) followed by kB1R agonists (DAKD or DABK) (upper panel) and vice versa (lower panel) and the increase in [Ca2+]i was measured. Results shown are representative of at least 3 experiments. C and D. CHO cell stably expressing kB1R-CFP and kB2R-YFP were preincubated with 1 μM kB2R agonists KD (C) or BK (D), or 1μM kB1R agonists DAKD (C) or DABK (D) for 10 min, and then were stimulated with an equal dose of kB2R agonists or kB1R agonists for 30 min. The arachdonic acid (AA) release was measured as described in Methods. The data are expressed as mean ± SE (n=3). *P<0.05 vs DAKD (C) or DABK (D) (Student’s t test).

To determine if this heterologous desensitization was specific to the downstream signaling pathway being stimulated, arachidonic acid (AA) release was measured. In CHO cells stably expressing kB1Rs and kB2Rs, agonists of both receptors stimulated a significant increase in AA release (Figs. 2C and 2D). However, in cells pretreated with kB2R agonists KD or BK, subsequent responses to DAKD or DABK were greatly reduced (Figs. 2C and 2D). In contrast, pretreatment with kB1R agonists DAKD or DABK did not reduce AA generation caused by a second stimulation with kB2R agonists KD or BK (Figs. 2C and 2D).

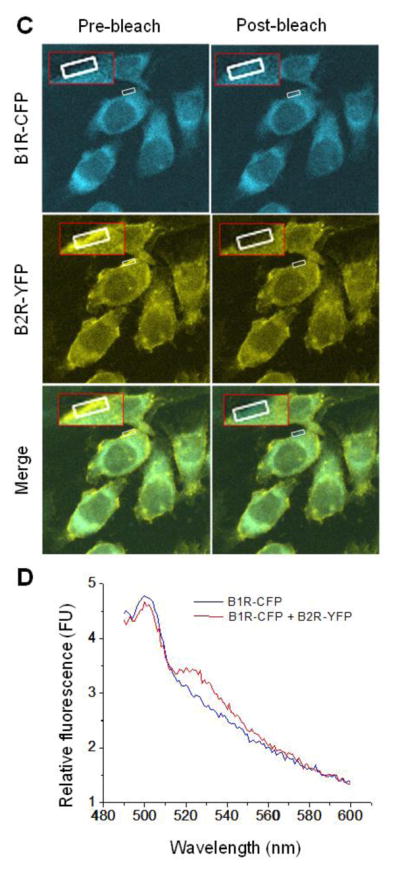

3.3. Downregulation of the kB1R response is dependent on kB2R expression and agonist dose

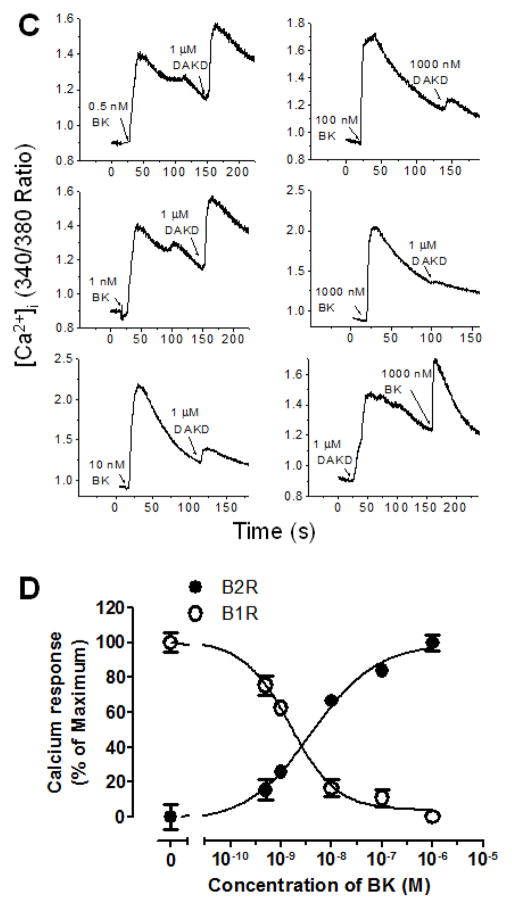

Increasing doses of KD were used to stimulate the kB2R before stimulating a second calcium response with kB1R agonist DAKD. As shown in Fig. 3A, 0.25 nM KD stimulated a small kB2R-dependent calcium response and a subsequent 1 μM dose of DAKD resulted in a large kB1R-dependent increase in [Ca2+]i, but further increases in KD concentration (from 0.5 to 100 nM) resulted in a diminishing subsequent kB1R response until it disappeared after 100 nM KD pretreatment (Fig. 3A). The kB1R-dependent increase in [Ca2+]i was inversely correlated with the calcium response mediated by kB2R agonist (Fig. 3B). The EC50 (half maximal effective concentration) of kB2R agonist KD for activating the kB2R-mediated calcium response was 7.8 × 10−10 M while its IC50 (half maximal inhibitory concentration) for the subsequent kB1R response was 1.2 × 10−9 M in these cells. The ratio of EC50 to IC50 was about 0.6. Similar results were obtained in primary BPAEC as shown in Figs. 3C and 3D. In these cells, the kB2R agonist BK also dose-dependently decreased the calcium response induced by a succeeding addition of kB1R agonist DAKD (Fig. 3C) and there was an inverse correlation of the inhibition with the initial kB2R response (Fig. 3D). The EC50 of kB2R agonist BK for activating the kB2R-mediated calcium response was 4.0 × 10−9 M whereas its IC50 for the subsequent kB1R response was 1.5 × 10−9 M in endothelial cells. The ratio of EC50 to IC50 was 2.7, even greater than that in the HEK cells stably expressing kB1R and kB2R. To prove that the downregulation of kB1R responses by BK and KD depended on kB2R expression, HEK cells stably expressing only kB1Rs were tested. In these cells, kB2R agonists KD (1 μM) and BK (1 μM) neither stimulated an increase in [Ca2+]i nor affected the subsequent calcium response stimulated by kB1R agonist DAKD (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, pre-treatment with kB2R agonist BK (1 μM) did not alter the dose-response curve of DAKD in the same cells (Fig. 4B) and the kB2R agonist BK did not induce an increase in [Ca2+]i at very high doses (up to 100 μM; Fig. 4B). Moreover, various concentrations (333–3000 nM) of kB2R agonist BK also did not interfere with the increase in [Ca2+]i mediated by different concentrations (10–300 nM) of kB1R agonist DAKD (Fig. 4C). Thus, alteration of kB1R responses by BK or KD requires co-expression of kB2Rs.

Figure 3. kB2R agonist pre-treatment dose-dependently attenuates the subsequent kB1R calcium response.

HEK cells stably expressing kB1R and kB2R (A and B) or bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells (C and D) were first stimulated with increasing concentrations of kB2R agonist, followed by kB1R agonist DAKD as indicated. The increase in [Ca2+]i was recorded as described in Methods. C and D, The increase in [Ca2+]i was quantified as described in Methods using the area under the curve. The dose-response curves were generated using GraphPad Prism 5.0. The data are shown as mean ± SE (n=3).

Figure 4. kB2R agonist downregulation of the kB1R calcium response requires the expression of kB2R.

A. HEK cells stably expressing only kB1R were first stimulated with kB2R agonists BK or KD, followed by kB1R agonists DABK or DAKD and the increase in [Ca2+]i was recorded. The traces are representative from at least three experiments. B. HEK cells stably expressing only kB1R were pretreated for 10 min with vehicle (△) or 1μM BK (▲), followed by various concentrations of kB1R agonist DAKD, or stimulated only with various concentrations of kB2R agonist BK (●). The increase in [Ca2+]i was recorded and quantified using the area under the curve as in Fig. 3. The data are representative of three experiments. C. HEK cells only stably expressing kB1R were pretreated with various concentrations of kB2R agonist BK for 10 min, and then stimulated with different concentrations of kB1R agonist DAKD and the increase in [Ca2+]i was recorded and quantified as in B. The data shown are mean ± SE (n=3).

3.4. kB2R endocytosis and signaling are involved in downregulating kB1R responses

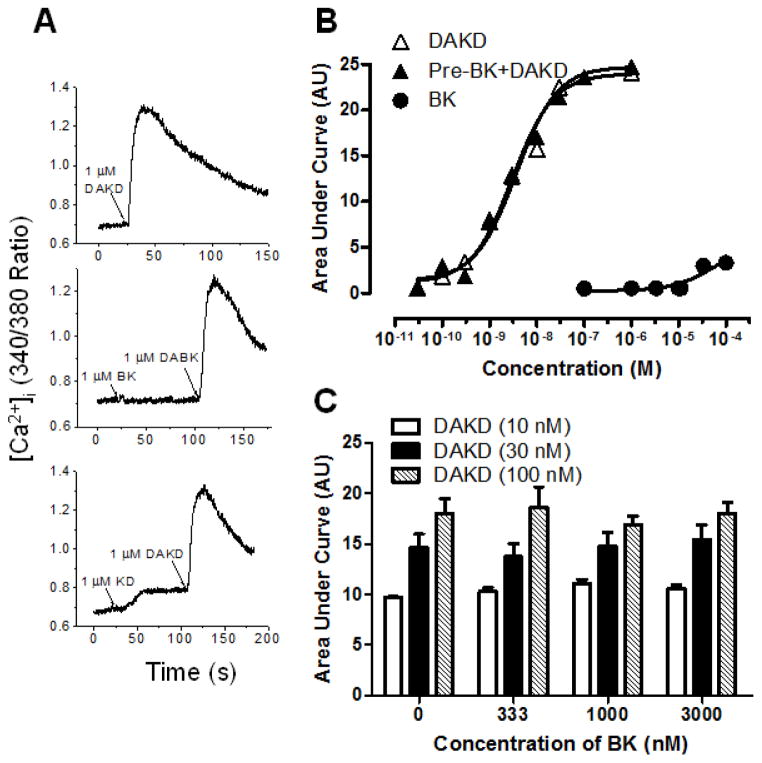

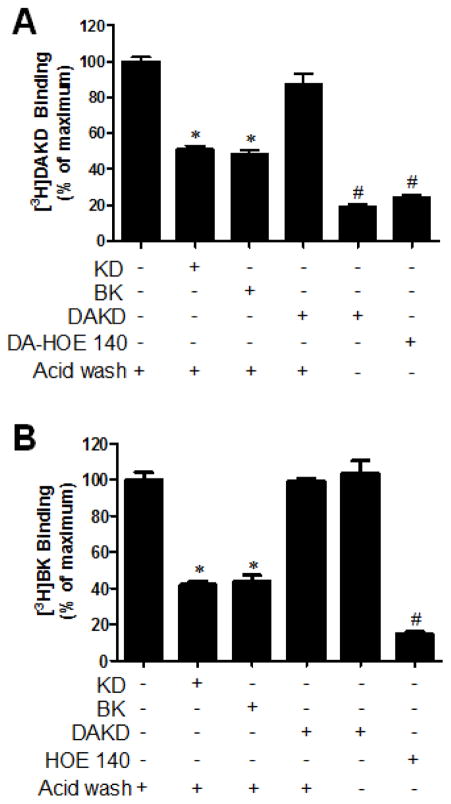

The kB2R is rapidly internalized in response to agonist stimulation whereas the kB1R is relatively resistant to endocytosis (2, 30, 42). In HEK cells stably expressing kB1R and kB2R, cell surface kB1R expression (as detected by [3H]-DAKD binding) was not decreased by pretreatment of cells with 1 μM DAKD for 10 min at 37°C, followed by acid washing to remove bound cold DAKD (Fig. 5A), consistent with previous reports (2, 30, 42). In contrast, pre-treatment of cells with 1 μM BK or KD significantly reduced cell surface kB1Rs (by ~50%) as measured by [3H]-DAKD binding after acid washing to remove BK or KD (Fig. 5A). kB1R antagonist des-Arg-HOE140 or 1 μM DAKD, without acid washing, inhibited [3H]-DAKD binding by ~80% (Fig. 5A). Pretreatment of the cells with 1 μM kB2R agonists KD or BK reduced cell surface kB2Rs to a similar extent as kB1Rs, as detected by [3H]-BK binding after acid washing, but pretreatment with kB1R agonist DAKD (1 μM) had no effect (Fig. 5B). kB2R antagonist HOE140 almost completely inhibited [3H]-BK binding as expected (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. kB2R agonists induced co-endocytosis of kB2R and kB1R.

HEK cells stably expressing kB1R and kB2R were incubated with 1 μM kB2R agonists KD or BK, kB1R agonist 1 μM DAKD or kB1R antagonist des-Arg10-HOE 140 (DA-HOE 140) for 10 min at 37 °C. After acid washing (or not, as indicated), the cells were further incubated with 4 nM [3H]DAKD (A) or [3H]BK (B) for 90 min on ice and radiolabel binding to kB1R or kB2R was determined as described in Methods. The data in A and B were calculated as percent of total binding compared with the cells which were not treated with agonist or antagonist, and shown as mean ± SE (n=3). *P<0.05 vs control not treated by agonist or antagonist; #P<0.05 vs KD or BK (ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test).

Activation of kB2Rs could downregulate kB1R signaling by co-endocytosis via protein-protein interaction and/or by effects of kB2R signaling on the kB1R response. To investigate these possibilities, we made use of two previously reported kB2R mutations; kB2R-Y129S (human numbering) is deficient in stimulating IP3 production and arachidonic acid release but is normally endocytosed whereas kB2R-T342A has normal signaling but is not internalized (28, 35). In HEK cells stably expressing kB2R-Y129S and kB1R, KD stimulated kB2R-Y129S internalization similar to that of wild type kB2R, as detected by [3H]-BK binding, but did not increase IP3 production over background levels (Figs. 6A and B), consistent with previous reports (29). Cell surface kB1R (as detected by [3H]-DAKD binding) was significantly decreased after stimulation of kB2R-Y129S with KD, similar to the decrease mediated by stimulation of wtkB2R (Fig. 6C). Pre-stimulation of kB2R-Y129S also significantly decreased IP3 production mediated by kB1R activation, although the decrease was less than that mediated by wtkB2R (Fig. 6D). These data indicate that part of the reduction in kB1R response is caused by its co-endocytosis with kB2Rs after their activation.

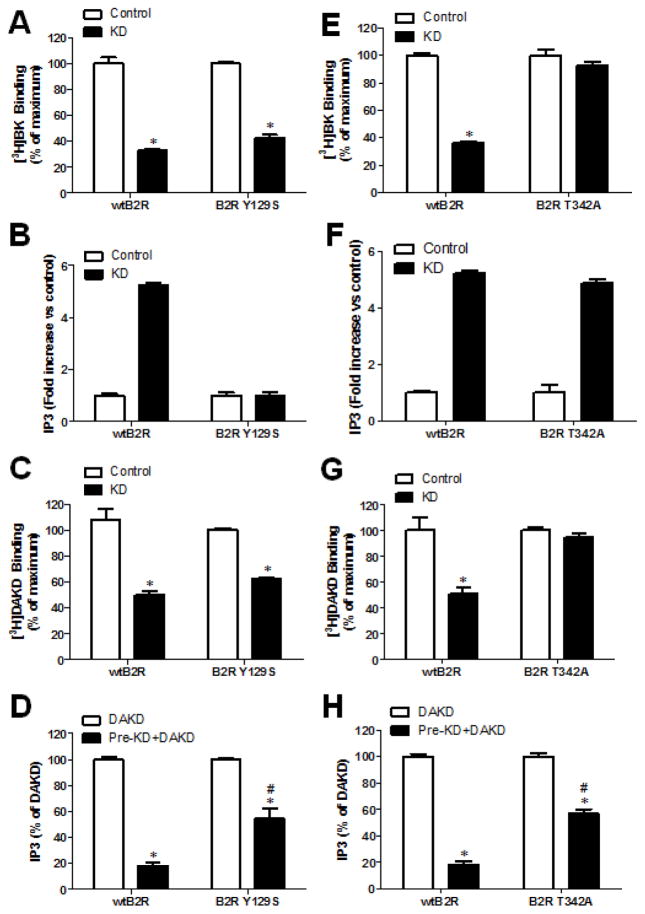

Figure 6. kB2R endocytosis and signaling are both required to downregulate kB1R signaling.

Experiments were conducted on HEK cells stably expressing kB1R and either wtkB2R, the signaling-defective mutant kB2R-Y129S (A–D) or the endocytosis-defective mutant kB2R-T342A (E–H). A, E. Cells were pretreated with kB2R agonist 1 μM KD for 10 min at 37 °C, and then [3H]BK binding to wtkB2R, kB2R-Y129S or kB2R-T342A on the cell surface were measured as described in Methods. The data were calculated as percent of total binding in cells not pre-treated with KD and are shown as mean ± SE (n=3). *p<0.05 vs Control (Student’s t test). B, F. Cells were incubated without (control) or with 1 μM KD for 30 min and IP3 production was determined as described in Methods. The fold-increase in IP3 over control is shown as mean ± SE (n=3). C, G. Cells were pretreated with kB2R agonist 1 μM KD for 10 min at 37 °C, and then cell surface [3H]DAKD binding to kB1R was determined as described in Methods. The data were calculated as percent of total binding in cells not pre-treated with KD and are shown as mean ± SE (n=3). *p<0.05 vs Control (Student’s t test). D, H. Cells were pretreated without or with 1 μM kB2R agonist KD, then incubated with 1 μM kB1R agonist DAKD for 30 min and the IP3 generation was determined. The IP3 production due to kB1R was calculated as total IP3 from the cells stimulated with KD and DAKD, minus IP3 generation from the cells treated only with KD. The data are shown as percent of IP3 generated in cells after stimulation with DAKD alone and shown as mean ± SE (n=3). *p<0.05 vs DAKD; #p<0.05 vs wtkB2R (Student’s t test).

The mutant kB2R-T342A was endocytosis-defective as expected (28), as there was no decrease in [3H]-BK binding after 10 min treatment with KD (Fig. 6E) but it generated IP3 levels the same as the wtkB2R (Fig. 6F). Interestingly, although pre-stimulation of kB2R-T342A with KD did not cause a decrease in membrane kB1Rs (Fig. 6G), it did significantly decrease kB1R-dependent IP3 production, although not as much as the wtkB2R (Fig. 6H). Taken together, the above data indicate that both kB2R signaling and co-endocytosis contribute to the downregulation of kB1R signaling after kB2R activation.

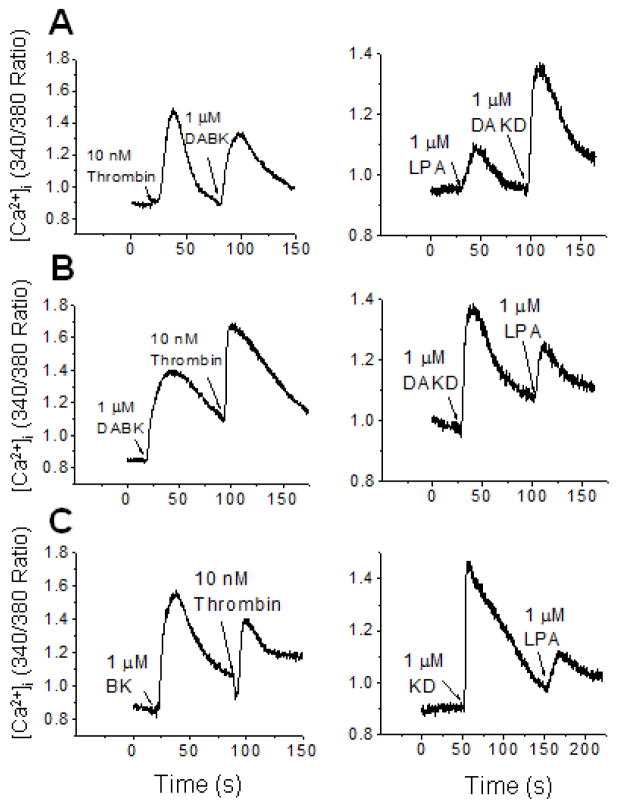

Heterologous GPCR desensitization via signaling can involve the depletion of calcium stores in the endoplasmic reticulum, Gαq phosphorylation or activation of other inhibitory signaling pathways (43, 44). To determine if signaling from other GPCRs might downregulate kB1R responses, we investigated the effects of thrombin, which stimulates protease activated receptor signaling via coupling with Gαq, Gαi and Gα12 (45), and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) which can activate GPCRs coupled with Gαq (46). In HEK cells stably expressing kB1R, thrombin caused a large increase in [Ca2+]i (Fig. 7A), similar to that stimulated by BK or KD in cells coexpressing kB1Rs and kB2Rs (Fig. 2). However, thrombin did not cause kB1R desensitization because it did not inhibit the increase in [Ca2+]i induced by subsequent addition of kB1R agonist DABK (1 μM) (Fig. 7A). Conversely, stimulation with kB1R agonist also did not heterologously desensitize the response to a subsequent dose of thrombin (Fig. 7A). LPA induced a relatively lower calcium response than thrombin in HEK cells expressing kB1R (Fig. 7B) and also did not decrease the kB1R response to a subsequent dose of kB1R agonist DAKD (Fig. 7B). Stimulation with DAKD also did not reduce the calcium response to a subsequent dose of LPA (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7. Lack of cross-desensitization between kB1R, kB2R and GPCR agonists thrombin or lysophosphaditic acid.

A. The calcium response in HEK cells stably expressing kB1R was measured after stimulation with thrombin (left panel) or LPA (right panel) followed by kB1R agonist. B. HEK cells stably expressing kB1R were first stimulated with kB1R agonist and then thrombin (left panel) or LPA (right panel) and the calcium response recorded. C. The calcium response was measured in HEK cells stably expressing kB2R after initial stimulation by kB2R agonist followed by thrombin (left panel) or LPA (right panel). The traces are representative examples from three experiments.

3.5 Differential recycling of kB1R and kB2R after co-internalization

When expressed alone, kB2Rs are endocytosed after agonist stimulation and rapidly recycle to the membrane whereas kB1Rs are resistant to agonist-dependent endocytosis and when taken up by the cells are targeted to lysosomes (47). To determine if the co-endocytosed kB1Rs would recycle with the kB2Rs, we investigated the reappearance of kB1R and kB2R signaling after 10 min pre-treatment with 1 μM KD after washing and incubation in agonist-free media. As shown in Fig. 8A, a calcium response to activation of either kB1R or kB2R reappeared after incubation in the agonist free media (Fig. 8A). However, the rate of recovery of the kB1R response was much slower and less complete than that of the kB2R (Fig. 8A and B). After 60 min, the kB2R calcium response had recovered to 92% of the level achieved in control cells not pretreated with KD, whereas that induced by kB1R only partially recovered (41%), even after 90 min (Fig. 8B). The recovery of the kB2R and kB1R response after KD pretreatment was also tested in primary BPAEC (Fig. 8C). As found in transfected HEK cells, the kB2R calcium response recovered more rapidly than that stimulated by the kB1R, however the recovery was more rapid in BPAEC; at 40 min, 41% and 82% of the kB1R and kB2R response had returned (Fig. 8C).

Figure 8. Recycling kinetics of kB1R and kB2R after co-internalization.

A. HEK cells stably expressing kB1R and kB2R were stimulated with either 1 μM DAKD (left panel) or 1 μM KD (right panel) to establish the control kB1R or kB2R calcium response. B. HEK cells stably expressing kB1R and kB2R were pre-incubated with 1 μM kB2R agonist KD for 10 min. Cells were then stimulated with 1 μM kB1R agonist DAKD followed by 1 μM kB2R agonist KD at the indicated times and the increase in [Ca2+]i was recorded and quantified using Origin 8.0 to integrate the area under the curve (C). D. Bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells were treated as in B, and the increase [Ca2+]i recorded and quantified as in C. The traces in A and B are representative from three experiments. The data in C and D were calculated as percent of area from the control response (A) and shown as mean ± SE (n=3).

3.6. Role of clathrin-coated pits in kB2R- mediated kB1R internalization

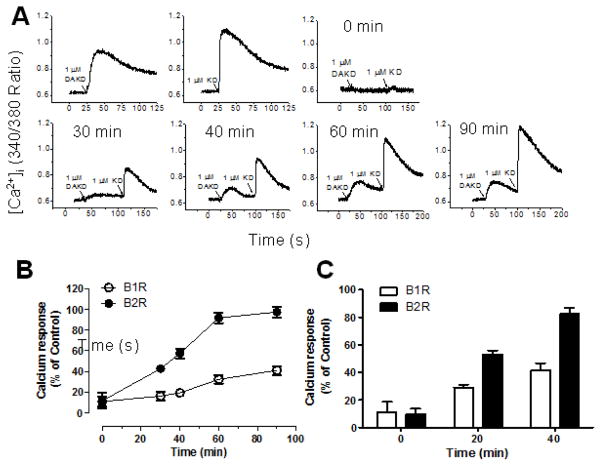

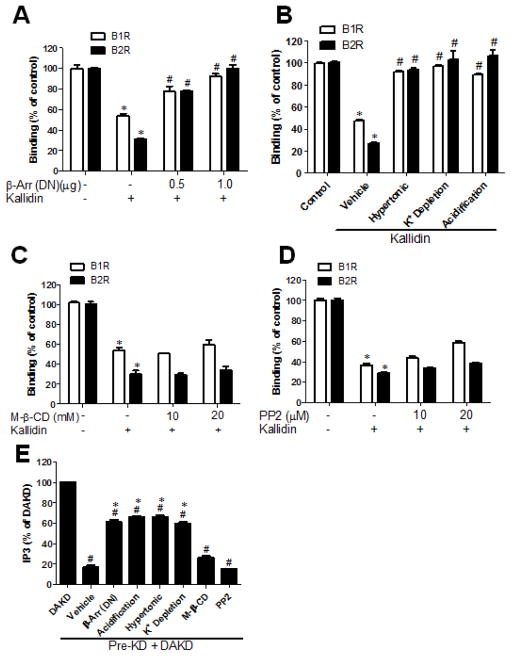

GPCRs are internalized after stimulation with agonists through endocytic pathways associated with clathrin-coated pits or caveolae (48, 49). β-arrestins- 1 and 2 play key roles in clathrin-dependent endocytosis of many GPCRs, as they are recruited to bind activated receptors and also bind to β2-adaptin and clathrin via homologous sequences in their C-terminal ends. The C-terminal regions of β-arrestins- 1and 2, containing the clathrin binding domain, act as a dominant negative mutants, inhibiting clathrin-dependent endocytosis of GPCRs (32, 50). Because the activated kB2R primarily interacts with β-arrestin-2 (51), we utilized the dominant negative mutant of β-arrestin-2 (284-409) (32). HEK cells stably expressing kB1R and kB2R were transfected with β-arrestin-2 (284-409) and then pretreated with 1 μM KD for 10 min to stimulate kB2R endocytosis. As shown in Fig. 9A, dominant negative β-arrestin-2 inhibited the endocytosis of both kB2R and kB1R as reflected by a reduction in the loss of [3H]-BK or [3H]-DAKD binding caused by KD. Furthermore, treatments known to interfere with clathrin-mediated endocytosis i.e., hypertonic treatment, depletion of intracellular potassium and acidification of the cytosol, also blocked the reduction in [3H]-BK or [3H]-DAKD binding caused by KD pretreatment (Fig. 9B).

Figure 9. Co-endocytosis of kB1R with kB2R requires the clathrin pathway.

A–D. HEK cells stably expressing kB1R and kB2R were pre-treated as described below, then incubated without (control) or with kB2R agonist 1 μM kallidin for 10 min followed by assessment of [3H]BK binding to kB2R or [3H]DAKD binding to kB1R as described in Methods. A. Cells were first transfected (or not) with the dominant-negative mutant of β-arrestin-2-(284-409) (β-Arr) for 24 h as indicated. B. Cells were subjected to hypertonic treatment, cytosol acidification or depletion of intracellular K+ before treatment with kallidin C. Cells were first treated with methyl-β-cyclodextrin for 30 min to disrupt caveolae. D. Cells were first treated with Src inhibitor PP2 for 10 min. The data were calculated as percent binding in control cells which were not treated and shown as mean ± SE (n=3). *p<0.05 vs control (ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test). E. HEK cells stably expressing kB1R and kB2R were treated as in A–D to interfere with the endocytic pathways related to clathrin-coated pits and caveolae. After the treatments, cells were pre-incubated with 1 μM KD kB2R agonist (Pre-KD) for 10 min, followed by incubation with 1 μM kB1R agonist DAKD for 30 min and IP3 production was measured as described in Methods. The IP3 production due to kB1R was calculated as total IP3 from the cells stimulated with KD and DAKD, minus IP3 generation from cells treated only with KD. The data are shown as percent of IP3 generated in cells after stimulation with DAKD alone and shown as mean ± SE (n=3). *p<0.05 vs. DAKD; # p<0.05 vs. vehicle (ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test).

Because it has been reported that kB2R is at least partly endocytosed via caveolae (40, 42), we used methyl-β-cyclodextrin to sequester cholesterol and disrupt caveolae. In HEK cells stably expressing kB1R and kB2R, pre-treatment with 10 or 20 mM methyl-β-cyclodextrin for 30 min did not affect the reduction in [3H]-BK or [3H]-DAKD binding caused by 1 μM KD (Fig. 9C). This indicates that caveolae are not involved in the co-internalization of kB1Rs and kB2Rs induced by kB2R agonist. To confirm this finding, we used PP2 to inhibit Src kinase activity, as phosphorylation of Tyr14 of caveolin by Src is required for caveolae endocytosis (52). In the same cells, pre-treatment with PP2 did not inhibit the loss of [3H]-BK or [3H]-DAKD binding caused by 1 μM KD (Fig. 9D).

We next determined the effect of endocytosis inhibitors on the decrease in kB1R signaling caused by KD pre-treatment. Inhibitors of clathrin-mediated endocytosis (dominant negative β-arrestin-2, hypertonic treatment, cytosol acidification and depletion of K+) significantly inhibited the decrease in kB1R-dependent IP3 caused by KD pretreatment (1 μM, 10 min) (Fig. 9E). However, kB1R-dependent IP3 generation was still less than that in the cells not pre-treated with kB2R agonist (Fig. 9E). In contrast, inhibition of caveolae endocytosis with methyl-β-cyclodextrin or PP2 did not reverse the inhibition of kB1R-dependent IP3 generation after kB2R agonist stimulation (Fig. 9E). None of the endocytosis inhibitors had a direct effect on IP3 production mediated by kB2R agonist KD itself (data not shown).

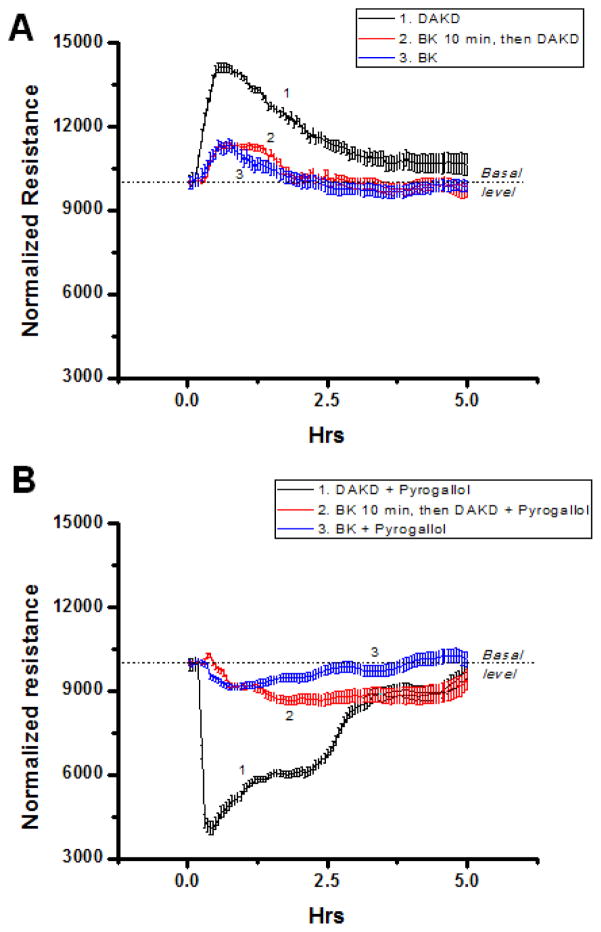

3.7. Functional effect of kB2R-mediated kB1R desensitization

To determine whether kB2R-mediated desensitization of kB1R signaling was functionally significant, we used cytokine-treated HLMVEC and measured changes in transendothelial electrical resistance (TER) (8, 39)in response to kB1R stimulation. We previously showed that these cells under inflammatory conditions generate high output NO from both kB2R – mediated stimulation of eNOS (53) and kB1R-dependent acute activation of iNOS (54, 55). Although iNOS-derived high output NO has been associated with loss of lung endothelial barrier function (56), NO itself is unlikely to be the primary mediator because it is not highly reactive and is rapidly removed by reaction with hemoglobin (57). However, reaction of NO with superoxide generates peroxynitrite (ONOO−), a reactive diffusible oxidant that can disrupt the endothelial barrier by protein nitration or oxidation of signaling proteins at sensitive thiol residues (56, 57). kB1R stimulation of cytokine-pretreated HLMVEC with 100 nM DAKD produced a substantial and prolonged (~5 h) increase in TER whereas 100 nM BK (in the presence of MGTA to block conversion to des-Arg9-BK) produced a modest and more transient (~1.5 h) increase (Fig. 10A). Interestingly, when cells were pre-treated for 10 min with 100 nM BK (in the presence of MGTA) and then 100 nM DAKD was added, the kB1R response was almost completely abolished and the change in TER was similar to that seen with BK alone (Fig. 10 A). To assess the effect of kB1R stimulation on potential disruption of the endothelial barrier in the presence of oxidants, we co-administered DAKD or BK with pyrogallol (which auto-oxidizes to produce O2. −) to generate ONOO−. Activation of the kB1R in cytokine-treated HLMVEC with 100 nM DAKD in the presence of pyrogallol caused a profound drop in resistance that returned to baseline in ~5h, consistent with the generation of ONOO− mediating an increase in endothelial permeability (Fig. 10B). Stimulation of HLMVEC with 100 nM BK (in the presence of MGTA) and pyrogallol, caused a slower and much smaller drop in resistance that recovered in within ~4h (Fig. 10B). Importantly, in cytokine-treated HLMVEC pre-treated for 10 min with 100 nM BK (in the presence of MGTA), addition of 100 nM DAKD caused a much smaller drop in TER (~23% of that with DAKD alone), part of which could be attributed to the effect of BK on the kB2R (Fig. 10B). These data show that kB2R-mediated desensitization of the kB1R response can have a profound effect on kB1R signaling in inflamed endothelial cells expressing both receptors at native levels.

Figure 10. kB2R agonist pre-treatment inhibits kB1R-mediated effects on endothelial permeability.

HLMVEC, grown to confluence on gold electrodes coated with 10 μg/ml fibronectin, were cytokine pre-treated (10ng/ml IL-1β + 100u/ml IFN-γ, 16 h). Medium was changed, cells were allowed to stabilize, and all samples to be treated with BK were pretreated for 20 min with 40 μM MGTA to inhibit carboxypeptidase conversion to DABK. A. Cells were treated with 1) 1 μM DAKD; 2) 1 μM BK for 10 min, then 1 μM DAKD; 3) 1 μM BK and TER was measured. B. Cells were treated with 1) 1 μM DAKD + 200 μM pyrogallol; 2) 1 μM BK for 10 min, then 1 μM DAKD + 200 μM pyrogallol; 3) 1 μM BK + 200 μM pyrogallol and then TER was measured. Results show mean values ± S.E. for n = 4.

4. Discussion

GPCR signaling is mediated and regulated by protein-protein interactions, most often by receptor interaction with cytosolic proteins such as G proteins, kinases, β-arrestins, etc. (58). However, membrane proteins can affect GPCR signaling as well, the most notable examples being the formation of GPCR homo- or hetero-dimers (58). The kinin receptors can also be regulated by interaction with other membrane proteins. For example, the kB2R was reported to form functional heterodimers with angiotensin AT1 or AT2 receptors (59, 60). The kB2R also heterodimerizes with ACE in cell membranes and this interaction allows ACE inhibitors to potentiate kB2R signaling independent of blocking kinin degradation via allosteric effects (22, 31, 61) and increases ACE activity in mouse endothelial cells and transfected cells (62). The kB1R was recently found to heterodimerizes with the apelin receptor, leading to enhanced signaling of the complex compared with either receptor alone (63). Our studies have identified a critical complex in lipid raft microdomains between kB1R and CPM, the enzyme that generates its agonist (8, 9). This kB1R/CPM heterodimer facilitates kB1R signaling in three ways (8, 9, 64, 65): 1) Basal CPM binding allosterically enhances kB1R affinity for agonist; 2) Kinin substrate (i.e., BK or KD) binding to CPM’s active site causes a conformational change that is transmitted via protein-protein interaction to activate the kB1R without agonist. 3) CPM cleaves the C-terminal Arg of KD (or BK) to generate kB1R agonist that further activates kB1R. The kB1R/CPM complex also promoted kB1R-mediated activation of high output nitric oxide by inducible nitric oxide synthase in inflamed endothelial cells and altered endothelial barrier permeability (8, 64).

Here we found that the kB1R and kB2R form heterodimers, resulting in heterologous desensitization of kB1R responses after pre-treatment with kB2R agonist. The first study to provide evidence of kB1R/kB2R interactions showed that co-expression of kB1R and kB2R in HEK cells induced proteolysis and loss of kB2R binding sites on the cell surface, resulting in heterodimers of intact kB1R and proteolytic fragments of kB2R which significantly increased basal and agonist-stimulated kB1R signaling (26). This appears to contradict a recent study showing cell surface kB1R/kB2R heterodimer formation in transfected HEK cells results in almost complete (80%) inhibition of agonist-induced kB1R signaling by stabilizing kB1R expression on the cell surface (27). The reason for this discrepancy is not clear and was not addressed in the recent publication. Although we did not directly compare kB1R signaling in cells expressing kB1R with those expressing both kB1R and kB2R, our stably co-expressing HEK cells responded robustly to 1 μM DAKD in stimulating calcium signaling, IP3 turnover and arachidonic acid release. Inhibition of the kB1R response was only seen after pretreatment of cells with kB2R agonists BK or KD.

Co-endocytosis of kB1R by kB2R activation could be an important mechanism for regulation of kB1R responses because, by itself, the receptor is resistant to internalization and desensitization, leading to prolonged signaling (2, 30). The desensitization was partly due to co-endocytosis of kB1R with kB2Rs and reduction of cell surface kB1Rs, because it could be partially blocked by a kB2R mutation (T342A) that renders it deficient in endocytosis while retaining wild type signaling (28, 35). This is consistent with a recent report showing that treatment of HEK cells co-expressing kB1R and kB2R with BK resulted in co-internalization of the receptors (27), but effects on kB1R signaling after BK treatment were not studied. We found the sorting of kB1R and kB2R to differ after endocytosis as reflected in different recycling kinetics, although the detailed mechanism is still to be determined. There are several examples of GPCR heterodimers that are co-endocytosed, including CCR5/C5aR and TPα/TPβ (66, 67), but sorting of the receptors after co-internalization was not studied. The co-internalization of kB1R and kB2R depended on the endocytic pathway associated with β-arrestin and clathrin-coated pits. Although the β arrestin-2 dominant negative construct inhibited co-endocytosis in our studies, it does not prove that only β arrestin-2 was involved as both arrestin isoforms interact with clathrin and β2-adaptin through homologous sequences in their C-terminal domains (48). Thus, the dominant negative β arrestin-2 construct could also inhibit β arrestin-1 binding to clathrin or β2-adaptin. Nevertheless, it is likely that β arrestin-2 was responsible as it was previously shown that the kB2R primarily interacts with this isoform (51). Both kB1R and kB2R are partially localized in lipid rafts/caveolae (9, 40) and the kB2R alone was reported to endocytose through both pathways (42, 68). Thus, our finding that kB1R and kB2R co-endocytosis is exclusively through clathrin coated pits raises the possibility that kB1R affects the kB2R endocytic pathway via heterodimerization, although further studies need to be done to identify the mechanism.

Pre-treatment of cells with kB2R agonist almost completely abolished subsequent kB1R signaling, although only ~50% of the cell surface kB1R was co-endocytosed. In addition, although the endocytosis-deficient kB2R mutant (T342A) resulted in no kB1R endocytosis, it only partially restored kB1R signaling. These data indicate that activation of kB2Rs inhibits kB1R signaling by a second mechanism, likely due to kB2R signaling, to cause full desensitization of the kB1R. Indeed, after kB2R agonist addition, the signaling-deficient kB2R mutant (Y129S) was endocytosed similar to wild type and cause kB1R endocytosis, but only partially restored kB1R signaling. Thus the full effect of kB2R activation on reduction of kB1R signaling is a combination of reduction of cell surface kB1R by co-endocytosis and attenuation of the remaining kB1R response by kB2R signaling.

The details of kB2R signaling involved in desensitization of kB1R still need to be explored, but two potential possibilities reported previously for heterologous desensitization are unlikely. Namely, that kB2R activation leads to the depletion of calcium stores in endoplasmic reticulum as was described for progesterone-mediated desensitization of the oxytocin, bradykinin and acetylcholine responses (43) or that BK induced Gαq/11 phosphorylation, which was reported for 5-HT2A-mediated heterologous desensitization of the kB2R (44). Thus, pre-stimulation of kB1R expressing cells with thrombin or LPA, which both activate Gαq-dependent calcium signaling, did not reduce the kB1R response in the same cells. Other possibilities worth exploring include phosphorylation of kB1R mediated by kinases activated kB2R signaling such as PKA, PKC or p90 ribosomal S6 kinase 2, which have all been shown to mediate heterologous desensitization of GPCRs (69, 70). Alternatively, kB2R activation could inhibit G protein coupling to the bound kB1R thus inhibiting signaling. This possibility is supported by the finding that GPCR dimers typically bind only one G protein, as with the leukotriene B4 or 5-hydroxytryptamine 2C receptor homodimers (71, 72), and G protein coupling to GPCR heterodimers can differ from that of respective homodimers, as found with the dopamine D1/D2 heterodimer (73).

In general, the kB1R and kB2R stimulate similar downstream signaling pathways, for example increasing intracellular Ca2+, PI turnover, arachidonic acid release, NO production and activation of MAP kinase cascades (2, 74, 75). However, there are also differences. For example, in normal endothelial cells, kB2R activates eNOS resulting in a short burst of Ca2+-dependent NO production that also depends on the level of phosphorylation at key sites (75), but in inflamed HLMVEC kB2R activation leads to prolonged high output NO by eNOS that is mediated by a novel Gαi/o- and MEK1/2 → JNK1/2- dependent pathway (53). In contrast, kB1R stimulation in cytokine-treated HLMVEC does not activate eNOS, but instead activates iNOS resulting from signaling through a Gαi/o-, βγ- and β-arrestin-2- dependent pathway activating Src → Ras → Raf → MEK1/2 → ERK1/2 which phosphorylates iNOS at Ser745 to generate even higher and prolonged NO than kB2R (55, 75, 76). In addition, the kB2R is typically associated with acute responses and the kB1R with more prolonged and chronic reactions as discussed above. Thus our finding of the downregulation of kB1R signaling by kB2R activation may be a control mechanism to dampen prolonged kB1R signaling under conditions where both receptors are co-expressed.

Under normal conditions, the kB1R is found in only a few cell types whereas the kB2R is widely expressed (2, 10). However, under inflammatory conditions favorable for activation of the kallikrein-kinin system, kB1R expression is induced in a variety of cell types and kB2R expression can also be enhanced (2, 11) indicating that both receptors would be likely co-expressed in cells to generate downstream responses. For example, retinal pigment and intestine epithelial cells express both kB1R and kB2R (77, 78) and both receptors are also coexpressed in various leukocytes, dendritic cells and mast cells, under normal, inflammatory or autoimmune disease conditions (2, 79–81). kB1R and kB2R also can be coexpressed in endothelial and heart cells where the expression of kB1R (and in some cases even kB2R) is induced by angiotensin II, laminar shear stress, high glucose, heart failure, tissue damage, myocardial infarction, diabetic cardiomyopathy and ischemia-reperfusion injury (82–88). kB1R and kB2R are also coexpressed in some types of cancer including lung cancer, esophageal squamous carcinoma and prostate cancer (25, 89, 90).

Cross-talk between kB1R and kB2R leading to desensitization of kB1R responses might be important for kinin signaling in the cardiovascular system. kB2R signaling has generally beneficial effects in myocardial infarction, heart failure, hypertension and coronary diseases, whereas kB1R activation can have both beneficial and deleterious effects. For instance, knockout of the kB2R in mice resulted in dilated and failing cardiomyopathy (12) whereas kB1R knockout attenuated diabetic cardiomyopathy, reduced cardiac fibrosis and improved systolic and diastolic function (91). Thus, taken together with our findings, kB2R activation could have beneficial effects mediated both by kB2R signaling as well as by reducing kB1R signaling via co-endocytosis coupled with the slower recovery of kB1R cell surface expression compared with kB2R. Interestingly, we found that in cytokine-treated HLMVEC, stimulation of the kB1R to activate iNOS caused a large increase in TER whereas when stimulated in the presence of pyrogallol (to form peroxynitrite), kB1R activation caused as profound disruption of the endothelial barrier. Importantly, both of these responses could be essentially abolished by pre-treating the cells with 100 nM BK for 10 min before the addition of kB1R agonist, showing the ability of kB2R signaling and co-endocytosis to downregulate kB1R signaling in endothelial cells expressing native levels of both receptors.

5. Conclusion

In summary, we found that kB1R heterodimerization with kB2R results in desensitization of kB1R signaling after stimulation with kB2R agonists. kB1R/kB2R co-endocytosis associated with β-arrestin and clathrin-coated pits as well as kB2R signaling were involved in the kB1R desensitization. This cross-talk between kB1R and kB2R signaling results in attenuation of kB1R-mediated effects on human endothelial cell permeability under inflammatory conditions and might be critical for regulating kinin effects in cardiovascular homeostasis and disease.

Highlights.

G protein-coupled kinin receptors B1(B1R) and B2 (B2R) heterodimerized.

B2R agonist pretreatment resulted in co-internalization and desensitization of B1R.

B2R-mediated loss of B1R signaling depended on both B2R endocytosis and signaling.

B2R activation attenuated B1R-mediated effects on endothelial permeability.

These results indicate a new approach to control pathological B1R signaling.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK41431 and HL60678. Xianming Zhang was the recipient of an American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Abbreviations

- kB1R

kinin B1 receptor

- kB2R

bradykinin B2 receptor

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- BK

bradykinin

- KD

kallidin

- DABK

des-Arg9-bradykinin

- DAKD

des-Arg10-kallidin

- BK

bradykinin

- KD

kallidin

- DABK

des-Arg9-bradykinin

- DAKD

des-Arg10-kallidin

- LV

left ventricular

- ACE

angiotensin I converting enzyme

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium

- CP

carboxypeptidase

- NO

nitric oxide

- F12

HAM’s F-12 medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- M-β-CD

Methyl-β-cyclodextrin

- HOE

HOE-140

- DAHOE

des-Arg9 -HOE-140

- PP2

4-Amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine

- MGTA

DL-2-mercaptomethyl-3-guanidinoethylthiopropanoic acid

- AA

arachidonic acid

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- BPAEC

bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells

- HLMVEC

human lung microvascular endothelial cells

- wt

wild type

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular calcium concentration

- RIPA buffer

20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% protease inhibitor cocktail

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PBST

PBS with 0.5% Tween-20

- PI

phosphoinositide

- IP3

inositol triphosphate

- CFP

cyan fluorescent protein

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- YFP

yellow fluorescent protein

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- TER

transendothelial electrical resistance

- LPA

lysophosphatidic acid

- peroxynitrite

ONOO−

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bhoola KD, Figueroa CD, Worthy K. Bioregulation of kinins: kallikreins, kininogens, and kininases. Pharmacol Rev. 1992;44:1–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leeb-Lundberg LM, Marceau F, Muller-Esterl W, Pettibone DJ, Zuraw BL. International union of pharmacology. XLV. Classification of the kinin receptor family: from molecular mechanisms to pathophysiological consequences. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:27–77. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erdös EG, Sloane EM. An enzyme in human blood plasma that inactivates bradykinin and kallidins. Biochem Pharmacol. 1962;11:582–592. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(62)90119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skidgel RA, Erdös EG. Structure and function of human plasma carboxypeptidase N, the anaphylatoxin inactivator. Int Immunopharmacol. 2007;7:1888–1899. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skidgel RA, Davis RM, Tan F. Human carboxypeptidase M. Purification and characterization of a membrane-bound carboxypeptidase that cleaves peptide hormones. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:2236–2241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang XM, Skidgel RA. Carboxypeptidase M. In: Rawlings ND, Salvesen G, editors. Handbook of Proteolytic Enzymes. Elsevier; 2013. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skidgel RA, Erdös EG. Cellular carboxypeptidases. Immunol Rev. 1998;161:129–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang X, Tan F, Brovkovych V, Zhang Y, Skidgel RA. Cross-talk between carboxypeptidase M and the kinin B1 receptor mediates a new mode of G protein-coupled receptor signaling. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:18547–18561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.214940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang X, Tan F, Zhang Y, Skidgel RA. Carboxypeptidase M and kinin B1 receptors interact to facilitate efficient b1 signaling from B2 agonists. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:7994–8004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709837200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith JA, Webb C, Holford J, Burgess GM. Signal transduction pathways for B1 and B2 bradykinin receptors in bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;47:525–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brechter AB, Persson E, Lundgren I, Lerner UH. Kinin B1 and B2 receptor expression in osteoblasts and fibroblasts is enhanced by interleukin-1 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Effects dependent on activation of NF-kappaB and MAP kinases. Bone. 2008;43:72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su JB. Kinins and cardiovascular diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:3423–3435. doi: 10.2174/138161206778194051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cayla C, Todiras M, Iliescu R, Saul VV, Gross V, Pilz B, Chai G, Merino VF, Pesquero JB, Baltatu OC, Bader M. Mice deficient for both kinin receptors are normotensive and protected from endotoxin-induced hypotension. FASEB J. 2007;21:1689–1698. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7175com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maestri R, Milia AF, Salis MB, Graiani G, Lagrasta C, Monica M, Corradi D, Emanueli C, Madeddu P. Cardiac hypertrophy and microvascular deficit in kinin B2 receptor knockout mice. Hypertension. 2003;41:1151–1155. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000064180.55222.DF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madeddu P, Varoni MV, Palomba D, Emanueli C, Demontis MP, Glorioso N, Dessi-Fulgheri P, Sarzani R, Anania V. Cardiovascular phenotype of a mouse strain with disruption of bradykinin B2-receptor gene. Circulation. 1997;96:3570–3578. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu J, Carretero OA, Sun Y, Shesely EG, Rhaleb NE, Liu YH, Liao TD, Yang JJ, Bader M, Yang XP. Role of the B1 kinin receptor in the regulation of cardiac function and remodeling after myocardial infarction. Hypertension. 2005;45:747–753. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000153322.04859.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xi L, Das A, Zhao ZQ, Merino VF, Bader M, Kukreja RC. Loss of myocardial ischemic postconditioning in adenosine A1 and bradykinin B2 receptors gene knockout mice. Circulation. 2008;118:S32–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.752865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su JB, Houel R, Heloire F, Barbe F, Beverelli F, Sambin L, Castaigne A, Berdeaux A, Crozatier B, Hittinger L. Stimulation of bradykinin B(1) receptors induces vasodilation in conductance and resistance coronary vessels in conscious dogs: comparison with B(2) receptor stimulation. Circulation. 2000;101:1848–1853. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.15.1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillmeister P, Gatzke N, Dulsner A, Bader M, Schadock I, Hoefer I, Hamann I, Infante-Duarte C, Jung G, Troidl K, Urban D, Stawowy P, Frentsch M, Li M, Nagorka S, Wang H, Shi Y, le Noble F, Buschmann I. Arteriogenesis is modulated by bradykinin receptor signaling. Circ Res. 2011;109:524–533. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.240986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kakoki M, McGarrah RW, Kim HS, Smithies O. Bradykinin B1 and B2 receptors both have protective roles in renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7576–7581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701617104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kakoki M, Sullivan KA, Backus C, Hayes JM, Oh SS, Hua K, Gasim AM, Tomita H, Grant R, Nossov SB, Kim HS, Jennette JC, Feldman EL, Smithies O. Lack of both bradykinin B1 and B2 receptors enhances nephropathy, neuropathy, and bone mineral loss in Akita diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:10190–10195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005144107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erdös EG, Tan F, Skidgel RA. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitors are allosteric enhancers of kinin B1 and B2 receptor function. Hypertension. 2010;55:214–220. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.144600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfeffer MA, Frohlich ED. Improvements in clinical outcomes with the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: cross-fertilization between clinical and basic investigation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H2021–2025. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00647.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanchez de Miguel L, Neysari S, Jakob S, Petrimpol M, Butz N, Banfi A, Zaugg CE, Humar R, Battegay EJ. B2-kinin receptor plays a key role in B1-, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor-, and vascular endothelial growth factor-stimulated in vitro angiogenesis in the hypoxic mouse heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;80:106–113. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barki-Harrington L, Bookout AL, Wang G, Lamb ME, Leeb-Lundberg LM, Daaka Y. Requirement for direct cross-talk between B1 and B2 kinin receptors for the proliferation of androgen-insensitive prostate cancer PC3 cells. Biochem J. 2003;371:581–587. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang DS, Ryberg K, Morgelin M, Leeb-Lundberg LM. Spontaneous formation of a proteolytic B1 and B2 bradykinin receptor complex with enhanced signaling capacity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22102–22107. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402572200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Enquist J, Sanden C, Skroder C, Mathis SA, Leeb-Lundberg LM. Kinin-stimulated B1 receptor signaling depends on receptor endocytosis whereas B2 receptor signaling does not. Neurochem Res. 2014;39:1037–1047. doi: 10.1007/s11064-013-1126-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pizard A, Blaukat A, Muller-Esterl W, Alhenc-Gelas F, Rajerison RM. Bradykinin-induced internalization of the human B2 receptor requires phosphorylation of three serine and two threonine residues at its carboxyl tail. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12738–12747. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prado GN, Mierke DF, Pellegrini M, Taylor L, Polgar P. Motif mutation of bradykinin B2 receptor second intracellular loop and proximal C terminus is critical for signal transduction, internalization, and resensitization. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33548–33555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prado GN, Taylor L, Zhou X, Ricupero D, Mierke DF, Polgar P. Mechanisms regulating the expression, self-maintenance, and signaling-function of the bradykinin B2 and B1 receptors. J Cell Physiol. 2002;193:275–286. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Z, Deddish PA, Minshall RD, Becker RP, Erdös EG, Tan F. Human ACE and bradykinin B2 receptors form a complex at the plasma membrane. FASEB J. 2006;20:2261–2270. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6113com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orsini MJ, Benovic JL. Characterization of dominant negative arrestins that inhibit beta2-adrenergic receptor internalization by distinct mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34616–34622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.34616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang X, Lowry JL, Brovkovych V, Skidgel RA. Characterization of dual agonists for kinin B1 and B2 receptors and their biased activation of B2 receptors. Cell Signal. 2012;24:1619–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalatskaya I, Schussler S, Blaukat A, Muller-Esterl W, Jochum M, Proud D, Faussner A. Mutation of tyrosine in the conserved NPXXY sequence leads to constitutive phosphorylation and internalization, but not signaling, of the human B2 bradykinin receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31268–31276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401796200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prado GN, Taylor L, Polgar P. Effects of intracellular tyrosine residue mutation and carboxyl terminus truncation on signal transduction and internalization of the rat bradykinin B2 receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14638–14642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fire E, Gutman O, Roth MG, Henis YI. Dynamic or stable interactions of influenza hemagglutinin mutants with coated pits. Dependence on the internalization signal but not on aggregation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21075–21081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.36.21075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yao D, Ehrlich M, Henis YI, Leof EB. Transforming growth factor-beta receptors interact with AP2 by direct binding to beta2 subunit. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:4001–4012. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-07-0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu X, Zhao X, Puertollano R, Bonifacino JS, Eisenberg E, Greene LE. Adaptor and clathrin exchange at the plasma membrane and trans-Golgi network. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:516–528. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-06-0353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tiruppathi C, Malik A, Vecchio P, Keese C, Giaever I. Electrical Method for Detection of Endothelial Cell Shape Change in Real Time: Assessment of Endothelial Barrier Function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:7919–7923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.7919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lamb ME, Zhang C, Shea T, Kyle DJ, Leeb-Lundberg LM. Human B1 and B2 bradykinin receptors and their agonists target caveolae-related lipid rafts to different degrees in HEK293 cells. Biochemistry. 2002;41:14340–14347. doi: 10.1021/bi020231d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaczor AA, Selent J. Oligomerization of G Protein-Coupled Receptors: Biochemical and Biophysical Methods. Curr Med Chem. 2011 doi: 10.2174/092986711797379285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lamb ME, De Weerd WF, Leeb-Lundberg LM. Agonist-promoted trafficking of human bradykinin receptors: arrestin- and dynamin-independent sequestration of the B2 receptor and bradykinin in HEK293 cells. Biochem J. 2001;355:741–750. doi: 10.1042/bj3550741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gehrig-Burger K, Slaninova J, Gimpl G. Depletion of calcium stores contributes to progesterone-induced attenuation of calcium signaling of G protein-coupled receptors. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:2815–2824. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0360-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi J, Zemaitaitis B, Muma NA. Phosphorylation of Galpha11 protein contributes to agonist-induced desensitization of 5-HT2A receptor signaling. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:303–313. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.028241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hollenberg MD, Compton SJ. International Union of Pharmacology. XXVIII. Proteinase-activated receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:203–217. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chun J, Hla T, Lynch KR, Spiegel S, Moolenaar WH. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXVIII. Lysophospholipid receptor nomenclature. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:579–587. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Enquist J, Skroder C, Whistler JL, Leeb-Lundberg LM. Kinins promote B2 receptor endocytosis and delay constitutive B1 receptor endocytosis. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:494–507. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.030858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolfe BL, Trejo J. Clathrin-dependent mechanisms of G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis. Traffic. 2007;8:462–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chini B, Parenti M. G-protein coupled receptors in lipid rafts and caveolae: how, when and why do they go there? J Mol Endocrinol. 2004;32:325–338. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0320325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krupnick JG, Santini F, Gagnon AW, Keen JH, Benovic JL. Modulation of the arrestin-clathrin interaction in cells. Characterization of beta-arrestin dominant-negative mutants. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32507–32512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zimmerman B, Simaan M, Akoume MY, Houri N, Chevallier S, Seguela P, Laporte SA. Role of β arrestins in bradykinin B2 receptor-mediated signalling. Cell Signal. 2011;23:648–659. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun Y, Hu G, Zhang X, Minshall RD. Phosphorylation of caveolin-1 regulates oxidant-induced pulmonary vascular permeability via paracellular and transcellular pathways. Circ Res. 2009;105:676–685. 615. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.201673. following 685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lowry JL, Brovkovych V, Zhang Y, Skidgel RA. Endothelial Nitric-oxide Synthase Activation Generates an Inducible Nitric-oxide Synthase-like Output of Nitric Oxide in Inflamed Endothelium. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:4174–4193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.436022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brovkovych V, Zhang Y, Brovkovych S, Minshall RD, Skidgel RA. A novel pathway for receptor-mediated post-translational activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase. J Cell Mol Med. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00992.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang Y, Brovkovych V, Brovkovych S, Tan F, Lee B-S, Sharma T, Skidgel RA. Dynamic receptor-dependent activation of inducible nitric-oxide synthase by ERK-mediated phosphorylation of Ser745. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32453–32461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706242200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sittipunt C, Steinberg KP, Ruzinski JT, Myles C, Zhu SHA, Goodman RB, Hudson LD, Matalon S, Martin TR. Nitric Oxide and Nitrotyrosine in the Lungs of Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:503–510. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.2004187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:315–424. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ritter SL, Hall RA. Fine-tuning of GPCR activity by receptor-interacting proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:819–830. doi: 10.1038/nrm2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abadir PM, Periasamy A, Carey RM, Siragy HM. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor-bradykinin B2 receptor functional heterodimerization. Hypertension. 2006;48:316–322. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000228997.88162.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.AbdAlla S, Abdel-Baset A, Lother H, el Massiery A, Quitterer U. Mesangial AT1/B2 receptor heterodimers contribute to angiotensin II hyperresponsiveness in experimental hypertension. J Mol Neurosci. 2005;26:185–192. doi: 10.1385/JMN:26:2-3:185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Erdös EG, Deddish PA, Marcic BM. Potentiation of Bradykinin Actions by ACE Inhibitors. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 1999;10:223–229. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(99)00156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]