Abstract

Significant morbidity and potential mortality following dengue virus infection is a re-emerging global health problem. Due to the limited effectiveness of current disease control methods, mosquito biologists have been searching for new methods of controlling dengue transmission. While much effort has concentrated on determining genetic aspects to vector competence, paratransgenetic approaches could also uncover novel vector control strategies. The interactions of mosquito midgut microflora and pathogens may play significant roles in vector biology. However, little work has been done to see how the microbiome influences the host's fitness and ultimately vector competence. Here we investigated the effects of the midgut microbial environment and dengue infection on several fitness characteristics among three strains of the primary dengue virus vector mosquito Aedes aegypti. This included comparisons of dengue infection rates of females with and without their normal midgut flora. According to our findings, few effects on fitness characteristics were evident following microbial clearance or with dengue virus infection. Adult survivorship significantly varied due to strain and in one strain varied due to antibiotic treatment. Fecundity varied in one strain due to microbial clearance by antibiotics but no variation was observed in fertility due to either treatment. We show here that fitness characteristics of Ae. aegypti vary largely between strains, including varying response to microflora presence or absence, but did not vary in response to dengue virus infection.

Keywords: Aedes aegypti, midgut microflora, fitness, dengue, life history trait, vector competence

1. Introduction

Aedes aegypti is of considerable medical importance, being one of the world's most widely distributed mosquitoes and an influential vector of several deadly arboviruses. The most important of these arboviruses is dengue, with over 2.5 billion people living in high-risk areas and 390 million infections per year (Bhatt et al., 2013). Dengue transmission tends to occur in urban areas where Ae. aegypti is present. Females are commonly found in high numbers in close contact with human dwellings, laying eggs in artificial containers within or around houses (Chadee et al., 2000). Currently there are no licensed vaccines or drugs, and rapid emergence of insecticide resistance can limit vector control effectiveness. Because of the frequent failure of existing dengue control strategies, researchers have been looking into developing novel techniques to control viral transmission. This includes recent interest in exploiting normal mosquito microflora to reduce mosquito vectorial capacity (Ye et al., 2014), including development of paratransgenesis approaches (Blair et al., 2000). Paratransgenesis involves genetically modifying bacteria to express antipathogen molecules that are able to interfere with pathogen infection and replication inside the mosquito host (Coutinho-Abreu et al., 2010).

The symbiotic relationship between gut flora and their host organism is a widely studied topic. While the dynamics and physiology of the digestive tract is complex in itself, the microbial inhabitants of the gut have their own intricate processes. Understanding the interactions and mechanics of internal microbial environments provides insight to nutrient distribution and metabolism, but when considering vectors of infectious diseases, the association becomes more complex with the addition of invading pathogens. Inhabitant bacteria are usually advantageous or benign in fit individuals (Douglas, 2010) and are usually host-specific (Dethlefsen et al., 2007; Ley, 2008). Throughout the development of a host, established bacteria must complement and support the needs of the host as well as its own in order to create an efficient mutualistic relationship. Microflora environments have been found to make significant contributions to the nutrition of the host in many non-hematophagous insects (Dillion and Dillion, 2004). In obligate blood feeders, like the tsetse fly, modified or absent midgut microfloral populations resulted in distorted development and fitness (Nogge et al., 1976). Due to the differences between the digestive and metabolistic tendencies between obligate and opportunistic blood feeders, these extreme effects are not observed in microbial cleansing of occasional blood feeders. However, because of this variable and extremely diverse microbiome, it is understandably difficult to distinguish certain relationships between microorganisms and fitness of the vector hosts.

There is little known about the midgut microbiome's effects on mosquito biology. Only a limited number of studies have been conducted on mosquito midgut microbes, and most of these have concentrated on determining the composition of the microbiome, instead of the influence the microbes have on mosquito biology. A study involving Culex pipiens showed that microflora strongly influence digestion and fecundity of the mosquito and are needed for the completion of embryonic development (Fouda et al., 2001). Evidence that midgut microflora does work with its host to digest blood meals was found in a study with Ae. aegypti. Reduction of microbes with antibiotics resulted in delayed red blood cell lysis, impaired protein digestion and nutrient deprivation (Gaio et al., 2011). Oocyte maturation was also reduced due to microbe reduction.

To date, limited effort has been directed toward understanding the influence of the midgut microfloral environment on vector competence and pathogen transmission. Several recent studies have reported an interaction between the mosquito innate immune response and the midgut microbiome to reduce successful pathogen establishment. In Anopheles gambiae, antibiotic clearance of normal gut bacteria was found to increase susceptibility to the malaria parasite, Plasmodium faciparum, presumably because presence of midgut bacteria evokes a heightened immune response that also has anti-Plasmodium activity (Dong et al., 2009). It has been shown that normal microflora are capable of priming the A. gambiae innate immune system and indirectly enhancing protection against reinfection by malaria parasites (Rodrigues et al., 2010). In addition, a mechanism was uncovered in Plasmodium inhibition in A. gambiae that involved exposure to an Enterobacter bacterium without obvious involvement of the innate immune response, and instead was due to diffusible factors produced by the bacteria (Cirimotich et al., 2011). When observing the effects of microflora in Ae. aegypti, there has been evidence that when it comes to bacterial influence, specific species can have more influence than others. Serratia odorifera was found to significantly enhance viral susceptibility in aseptic females, but females fed solely dengue virus or females co-fed other bacteria did not change (Apte-Deshpande et al., 2012). It was also found that a marked decrease in dengue susceptibility was observed when Proteus sp. or Paenibacillus sp. were incorporated in blood meals in aseptic females (Ramirez, et al., 2012). These examples demonstrate strong interactions between bacterial fauna and the infiltrating pathogens.

Understanding the role that normal midgut microbes play in basic mosquito biology as well as their potential impact on virulence of pathogens is vital to our overall understanding of factors driving vectorial capacity. With the limited success with dengue vaccine development to date, and recognized problems with vector control, other more intrinsic disease control methods need to be explored. In this study, we examined the effects of midgut microbial environment and dengue virus infection on life history traits across Ae. aegypti strains differing in vector competence to dengue virus and explored dengue virus infection rates of females with and without their normal midgut flora.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Mosquito rearing and bacterial clearance

Mosquitoes were reared and maintained in environmental chambers following our standard conditions (Clemons et al., 2010). Environmental chambers were held at 26°C, 85% relative humidity, with a 16 h light: 8 h dark cycle, which included a 1-h crepuscular period to simulate dawn and dusk. Three strains of Ae. aegypti were used: Moyo-S, Moyo-R and the D2S3 strain. Moyo-S and Moyo-R are substrains selected for high and low susceptibility, respectively, to the avain malaria parasite, Plasmodium gallinaceum, from the Moyo-In-Dry strain (Thathy et al., 1994). They were subsequently determined to show high and low susceptibility to dengue virus as well (Schneider et al., 2007). The D2S3 strain is an unrelated strain that was selected for high susceptibility to dengue serotype 2 (DENV-2) strain JAM1409 (Bennett et al., 2005).

For each replicate of each strain (n=3), pupae were separated into two cages pre-adult emergence. Post-adult emergence, the two cages were provided with different sugar solution treatments. One cage was provided a control sterilized 8% sugar solution, while the other cage was provided an 8% sterilized sugar solution containing 2% penicillin-streptomycin and 0.8% gentamicin sulfate (Touré et al., 2000). Both sugar treatments were provided ad libitum using saturated sterilized cotton balls. Mosquitoes were allowed 8 days of sugar feeding to assure optimal clearance of midgut microbial populations among the antibiotic treatment. To verify microbial clearance, midguts were dissected from 20 random females for each treatment and homogenized in sterilized PBS (Pidiyar et al., 2004). Thereafter, 1.5 μl aliquots of the midgut solutions were prepared and spread on blood agar plates under sterile conditions. After 72 hrs, plates were examined for microbial growth. Effectiveness of bacterial clearance treatment efforts was also validated using a culture-independent method utilizing 16S rRNA amplification. Regions of the 16S rRNA gene (about 375 bp) from the microflora were amplified with universal primers 16s27F (5’- CCAGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG -3’) and 16s343R (5’-ACTGCTGCCTCCCGTA -3’) (GenBank: KF672364.1). The PCR was run at 95°C for 5 minutes followed by 30 cycles of 1 minute of 94°C, 1 minute at 60°C, and 2 minutes at 72°C, followed by an extension step of 72°C for 10 minutes.

2.2 Mosquito blood feeding and infection with dengue-2 virus

Septic and aseptic mosquitoes were each separated into two blood meal treatments, a control normal blood meal and a dengue infected blood meal. Females were starved for 24 hours and then provided an artificial blood meal, prepared using defibrinated sheep blood (Colorado Serum Company, Denver, CO, USA) mixed with equal volumes of either a control cell culture suspension or a dengue virus infection cell culture suspension. DENV-2 strain JAM1409 was cultured using Aedes albopictus C6/36 cells until 80-90% confluence. Cell culture and dengue virus infections were performed following Gaines et al. (1996), with slight modifications (Schneider et al., 2007). Cells were grown at 28°C without CO2 and infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1. Maintenance media with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) was added post inoculation with virus. Flasks were incubated at 28°C for 7 days after which the viral suspension was harvested. Blood feeding was performed with the use of an artificial blood feeding apparatus and sausage casing was used as an artificial membrane. Blood was kept warmed 37°C by using a circulating water bath (Rutledge et al., 1964). Females were allowed ~20 min to feed and fully engorged individuals were each placed into an oviposition vial. Each of the four treatments, non-antibiotic treated control blood meal (NAC), non-antibiotic treated dengue blood meal (NAD), antibiotic treated control blood meal (AC) and antibiotic treated dengue blood meal (AD), consisted of 35 females per replicate (n=3).

2.3. Determination of life history traits

Individual females were scored for life span, fecundity and fertility in three independent replicates. After the eight days of bacterial clearance, females were starved for 24 hours. Then females were blood fed and placed in an oviposition vial for observation and then scored for life span by each day they survived in each respective vial. Each vial was provided with an oviposition paper and water post-blood feeding to allow for egg laying. Females were allotted three days post-blood feeding to oviposit, and eggs were counted for each individual female to determine fecundity. Thereafter, each egg paper was allowed to dry for 48 hours. The dried eggs were then reintroduced to water and larval counts were determined 24 hours afterwards for each individual female to determine fertility.

2.4 Determination of disseminated dengue infections

Following an infectious blood meal, females were returned to their respective cages and sugar water treatments, maintained for twelve days, and then stored in RNAlater (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX, USA) at −80°C. Three independent replicates of RNA extractions were performed on legs from each female. RT-PCR was used to determine dengue infection. The ACCESS RT-PCR (reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction) kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) was used to identify disseminated infections following the manufacturer's protocol. Reactions were performed with the following conditions: 48°C for 45 min, 94°C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing and extension at 60°C for 30 s followed by 72°C for 2 min. Each of the two primer sets, RPL8 (F: TGGGGCGTGTTATTCGTGCACAG, R: GGTATCCGTGACGTTCGGCA) and DENV-2 344 bp (F: CAGGGACGAGGACCACTAAAA, R: ATGGCCATGAGGGTACACAT) were diluted to 10 ug/ul for the reactions. Primers for the 60s ribosomal protein L8 (RpL8) (AAEL000987-RA) were used to test quality of RNA, while the DENV-2 344 bp primers were specific for dengue-2 serotype (NCBI Reference Sequence: NC_001474.1).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Fecundity and fertility were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism 5 package within individual strains using a two way ANOVA and longevity was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier survival curves. For dengue disseminated infections, proportions of infected individuals (p) were transformed using arcsin √p and analyzed with a paired t-test.

3. Results

3.1 Bacterial Clearance

Plates were scored based on presence or absence of microbial colonies. The midguts from septic females displayed consistent microbial colony presence, characterized by mucoid texture on discolored agar, indicative with normal flora alpha hemolysis. Females with antibiotic treated midguts had no expression of alpha hemolysis and showed 95% clearance of bacterial growth as observed previously (Touré et al., 2000; Na'was et al., 1987). PCR results showed that non-treated midguts showed substantial bacterial 16S rRNA gene amplification whereas treated females had minimal or no 16S rRNA gene amplification.

3.2 Survivorship

We initially compared the survivorship of the strains under control conditions as a previous study (Yan et al., 1997) had shown that longevity of Moyo-S females was significantly longer than Moyo-R females. Our results were consistent with this as the mean survival time between strains was significantly different (p<0.0001), wherein mean survival time with Moyo-S (13.7 days) was significantly longer than that observed in Moyo-R (8.5 days) or D2S3 (7.3 days). Survival times of Moyo-R and D2S3 were not significantly different. When comparing the three strains, Moyo-S was significantly different from both of the other strains, while the Moyo-R and D2S3 strains were not significantly different from each other. Untreated Moyo-S females survived about twice as long as untreated Moyo-R or D2S3 females. Because of this, we did not make statistical comparisons across strains of potential interactions among treatment effects.

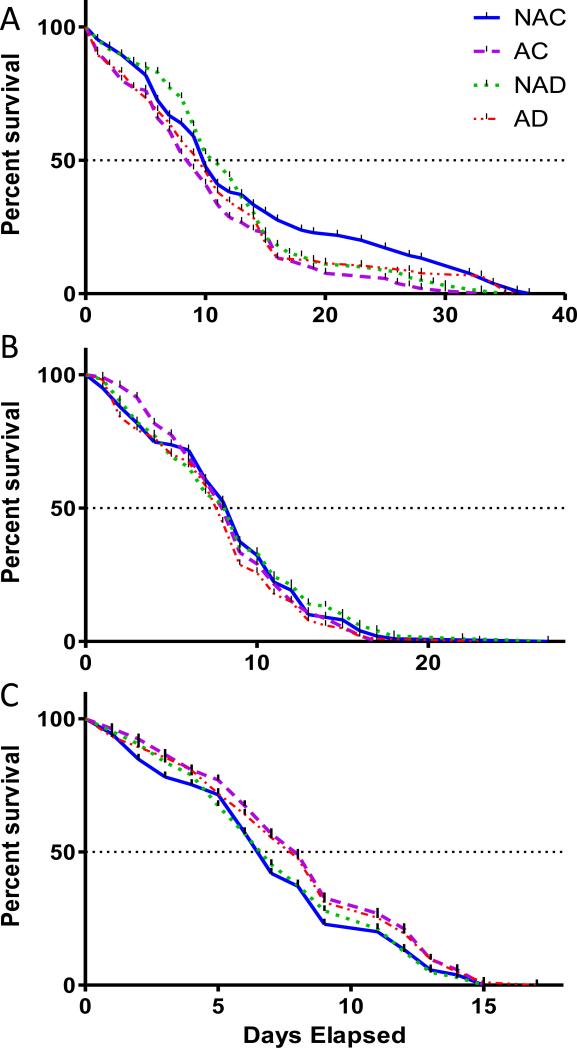

There was not a trend observed throughout the three strains in respect to treatment. Within strain comparisons of Kaplan-Meier plots between treatments using the log-rank test showed that only the Moyo-S strain expressed significant differences between treatments (p=0.047, Table S1). The treatment group that had the shortest overall lifespan was the microbially cleansed group that was fed a control blood meal (AC) (Figure 1A). The percentage of survival was lower for the AC treatment group roughly throughout the full time frame, while the untreated control group (NAC) showed generally higher survival over time. No effect of treatment on survivorship was observed in the Moyo-R strain (Figure 1B). An interesting but not significant trend was observed between treatments in the D2S3 strain survivorship. By the 50% survival point, the two microbial cleansed treatments (AC and AD) showed greater survival, reflecting more than a day's difference between the antibiotic treated and control treated females (Figure 1C). This is different than expected, considering the reliance other vectors have shown on their native fauna for fitness (Nogge et al., 1976).

Figure 1.

Survivorship curves of female Aedes aegypti comparing impact of antibiotic clearance of midgut bacteria and dengue virus infection. Significance was determined using Kaplan Meier statistics combining each of the three replicates (n=35 per replicate). Using the log rank test to compare the treatment curves, significance was only found with the Moyo-S strain (p=.047) and not with the Moyo-R or D2S3 strain (p=581; p=.250). NAC=Non-antibiotic treated control blood fed; NAD=Non-antibiotic dengue blood feed; AC=Antibiotic treated control blood fed; AD=Antibiotic treated dengue blood fed. A. Moyo-S, B. Moyo-R, C. D2S3.

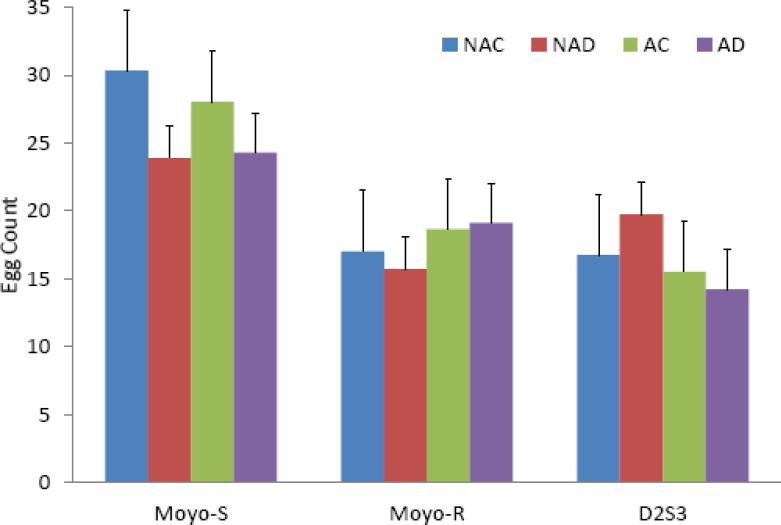

3.3 Fecundity

Treatment effects within strains were limited, and again, the only obvious difference was between strains with Moyo-S females producing more eggs on average (Figure 2). The data were analyzed using a two way ANOVA, considering the effects of antibiotic treatment and dengue infection on the individual strains (Table 1). No effects of either treatment were observed in the Moyo-S and Moyo-R strains. A significant effect of antibiotic treatment (p=0.03) was observed in the D2S3 strain, with antibiotic treated females producing fewer eggs (mean = 14.9) than control females (mean = 18.2). No significant effect of a dengue-infected blood meal was evident in any of the three strains.

Figure 2.

Influence of antibiotic clearance of midgut bacteria and dengue virus infection on fecundity (mean and standard deviation) in Aedes aegypti strains. Results are presented as mean and standard deviation. Three replicates were observed of each treatment and strain. Counts represent the number of eggs laid by each female. NAC=Non-antibiotic treated control blood fed; NAD=Non-antibiotic dengue blood feed; AC=Antibiotic treated control blood fed; AD=Antibiotic treated dengue blood fed.

Table 1.

Two way ANOVA statistics for fecundity.

| Strains | Moyo-S | Moyo-R | D2S3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | Sum of Squares | p value | df | Sum of Squares | p value | df | Sum of Squares | p value | |

| Antibiotic | 1 | 0.08 | 0.98 | 1 | 44.2 | 0.416 | 1 | 33.06 | 0.03 |

| Dengue | 1 | 77.3 | 0.47 | 1 | 6.39 | 0.753 | 1 | 2.223 | 0.51 |

| Interaction | 1 | 1.44 | 0.92 | 1 | 2.80 | 0.835 | 1 | 13.84 | 0.13 |

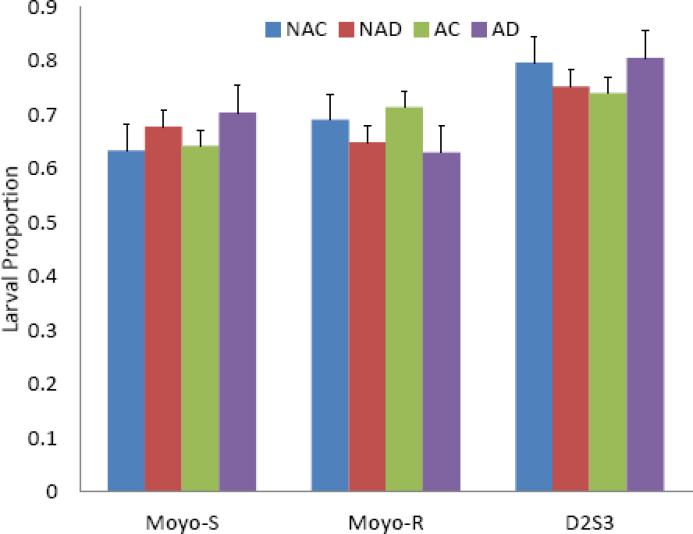

3.4 Fertility

Little variation was seen in fertility in response to the treatments within each strain (Figure 3). The data were analyzed using a two way ANOVA, considering the effects of antibiotic treatment and dengue infection on the individual strains (Table 2). No effects of either treatment were observed in any of the strains. Between strains, larval hatch proportions were slightly higher among D2S3 strain females.

Figure 3.

Influence of antibiotic clearance of midgut bacteria and dengue virus infection on fertility (mean and standard deviation) in Aedes aegypti strains. Results are presented as mean and standard deviation. Three replicates were observed of each treatment and strain. Counts were obtained by counting larvae that hatched from each female's egg paper. NAC=Non-antibiotic treated control blood fed; NAD=Non-antibiotic dengue blood feed; AC=Antibiotic treated control blood fed; AD=Antibiotic treated dengue blood fed.

Table 2.

Two way ANOVA statistics for fertility.

| Strains | Moyo-S | Moyo-R | D2S3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| df | Sum of Squares | p value | df | Sum of Squares | p value | df | Sum of Squares | p value | |

| Antibiotic | 1 | 0 | 0.93 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.75 | 1 | 0 | 0.94 |

| Dengue | 1 | 0.01 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 0.92 | 1 | 0 | 0.79 |

| Interaction | 1 | 0 | 0.73 | 1 | 0 | 0.95 | 1 | 0.02 | 0.26 |

3.5 Dengue dissemination

Infection comparisons were conducted only using the Moyo-S strain in three independent replicates. Proportions of infected individuals were transformed and analyzed with a paired t-test. The means of the non-antibiotic (mean=0.45; SD=0.18) and antibiotic-treated (mean=0.38; SD=0.12) groups were found to not be significantly different (t=0.83, df=2, p=0.49). Despite the lack of significance, there was a trend showing that non-antibiotic treated females had slightly higher infection rates, suggesting that absence of a microbial environment in the midgut can possibly decrease the likelihood of viral transmission.

4. Discussion

There have been various individual aspects investigated while studying vector microbiota, but there have been few studies that explore how midgut microfloral dynamics influence both fitness and pathogenesis, specifically viral, simultaneously. In this study, we were able to assess the effects of midgut microbial presence and dengue infection on fitness characteristics across three different strains of Ae. aegypti. We were also able to examine dengue infection rates of septic and aseptic females from a highly susceptible strain. According to our findings, changes in fitness characteristics were minimal due to microbial clearance and no significant effects were associated with viral infection. Survivorship significantly varied due to strain and in one strain varied due to microbial clearance. Fecundity varied in one strain also due to microbial clearance, but no effects were observed in fertility due to either microbial clearance or dengue infection. We show here that fitness characteristics of vectors vary primarily due to strain, and may be influenced by microbial presence, but do not appear to be affected by exposure to dengue virus. The microbiome of the Moyo-S and Moyo-R strains has been examined (Charan et al., 2013), revealing that certain microbes are exclusive to one strain or the other. It was also observed that bacterial abundance of the Moyo-R strain was at least 10-100 fold greater than observed in the Moyo-S strain. Thus, in addition to inherent variability in genetic backgrounds of mosquito populations, differences in their respective gut microbiota might influence their development or influence their susceptibility to dengue infection.

The availability of the draft genome sequence for Ae. aegypti provides an opportunity to identify genic factors that are required for dengue virus infection and subsequent transmission to humans (Nene et al., 2007). Gene interactions have been identified with the help of microarray analysis and RNAi screening, leading to the identification of cellular factors that can determine the susceptible or refractory nature of Ae. aegypti to host dengue virus (Xi et al., 2008; Sessions et al., 2009; Behura et al, 2011; Chauhan et al., 2012). This work offers great potential for detailed examinations of interactions between mosquito and virus, but there has been little work investigating the interactions that can occur between the mosquito and its normal midgut microbiome, and especially with respect to potential impact on vector competence. A recent study revealed that extensive transcriptional networks of mosquito genes are expressed in modular manners in response to DENV infection (Behura et al., 2011). It was also found that successfully defending against viral infection requires more elaborate gene networks than hosting the virus.

Pathogen's influence on fitness

Due to the nature of pathogens to extract nutrients from their respective hosts, it is easy to see how the biology of the host can be affected. While it is in the pathogen's best interest to keep its host healthy, there are still bound to be changes in the mosquito vector's homeostasis. These changes can be negligible or can cause shifts in the life history traits of the vector. In the case of Plasmodium relictum infections, Culex pipiens longevity increased while fecundity decreased (Vézilier et al., 2012). Additionally, insecticide resistant C. pipiens strains suffered a higher cost of infection, with a decrease in longevity. Fitness costs also afflict vectors with viral infections. In contrast with our results, results of another study of Ae. aegypti infected with DENV-2, indicated that exposed females had lower survival rates and decreases in longevity and in fecundity (Maciel-de-Freitas et al., 2011). That study utilized a field population along with a lab population, both of which were highly susceptible to dengue virus. The genetic background of these different mosquito strains as well as that of the virus isolates used could account for the variations observed between studies, along with the varied combinations of altered sugar water treatment throughout the early stages of adulthood. DENV-2 significantly decreased the mosquitoes’ motivation to feed, but increased their avidity, which likely impacts the vectorial capacity Ae. aegypti for dengue transmission (Maciel-de-Freitas et al., 2013). Western equine encephalomyelitis virus infection has been shown to affect the life history characteristics of its vector, Culex tarsalis, where longevity and reproduction rates were again decreased due to viral infection (Mahmood, et al., 2004). These studies are examples of how pathogen interactions interfere with the normal life history traits of vectors. It is understandable how the heightened immune response resulting from infection can shift nutrients and energy more towards defenses, leaving a deficit in survivorship and egg production.

Ae. aegypti life history traits and microfloral dynamics

Ae. aegypti is an unusually efficient vector of human disease, biting humans frequently and resulting in a high reproductive rate and high transmission rate, making females that feed on humans have a fitness advantage (Scott et al., 1997). Because of the high vector competence, efforts toward understanding the genic basis for refractoriness of the mosquito to pathogens have been a focus of many studies. Directional selection of P. gallinaceum refractory (Moyo-R) and susceptible (Moyo-S) substrains from the Moyo-In-Dry strain of Ae. aegypti provided insights into how vector competence status can influence fitness (Thathy et al., 1994). Our present results are similar to the previous comparisons of Moyo-S and Moyo-R life history characteristics. Both studies determined that Moyo-S females were found to live longer than Moyo-R when fed either control blood meals and when fed blood meals infected with a pathogen. That is, no significant effect of a pathogen-infected blood meal on life span was observed in either study. This suggests that although pathogens do affect mosquito immunity (Cirimotich et al., 2010), they don't necessarily manipulate the overall life span of infected females.

Our results for fecundity were generally consistent with those of Yan et al. (1997), wherein females of the Moyo-S strain had higher egg counts than the Moyo-R strain when provided a normal blood meal. However, when exposed to a Plasmodium- infected blood meal, egg counts were similar between the two strains. In our study, we found a similar trend in egg counts of the uninfected females, but saw less differentiation with the dengue-infected females. Egg production of microbially cleansed Ae. aegypti has been explored among females allowed to blood feed on mice (Gaio et al., 2011). After females were cleansed using single antibiotic treatments, oocytes and laid eggs were enumerated. Significant reductions were observed for the majority of antibiotics for both oocytes and eggs counts, but when a mixed antibiotic meal was introduced, no reduction was noticed for the oocytes. Additionally, there was also no fluctuation in fertility, consistent with our findings. Interestingly, fecundity was decreased in Culex tarsalis females infected with WNV (Styer et al., 2007), showing that viral infection can in some instances alter fitness.

Mosquito midgut bacteria have been found to contribute to digestion, reproduction, and fecundity (Pumpuni et al., 1996; Fouda et al., 2001; Mourya et al., 2002 ). In the case of Anopheles stephensi, gut sanitized mosquitoes were found to have reduced longevity and fecundity (Sharma et al., 2013). In the case of Ae. aegypti, the reduction of bacteria affected RBC lysis, subsequently retarded protein digestion, depleted nutrients availability and reduced fecundity (Gaio et al., 2011). Evidence for commensal specificity and coadaptation in Ae. aegypti has been explored by rechallenging females following midgut cleansing with original and novel bacteria. Pantoea stewartii isolated from Ae. aegypti induced a longer survivorship and reached higher numbers than P. stewartii isolated from A. gambiae and introduced to Ae. aegypti (Terenius et al., 2012). The evidence that microorganisms can truly be so environmentally selective is an important idea to consider when designing vector control strategies. Not much work has been done exploring the relationships between arboviruses and the microbiome and host fitness. Dengue infection has been compared before with the Rockefeller/UGAL strain of Ae. aegypti, and results showed that antibiotic treatment induced greater virus infection (Xi et al., 2008). These adverse results can again be explained by the strain-specific nature of these fauna. Very few bacteria have been investigated for their direct influence on pathogenesis. Virulent strains of the intracellular endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis have been found to hinder replication of many pathogens, like dengue virus, Chikungunya virus, and P. gallinaceum in Ae. aegypti (Moreira, et al., 2009). Certain bacterial species have been found to have significant influences on dengue infection in field isolates. A marked decrease in dengue susceptibility was observed when female Ae. aegypti were introduced to Proteus sp. or Paenibacillus sp. individually in a blood meal after the native bacterial fauna were cleansed (Ramirez, et al., 2012).

Conclusions

Research on microbe-pathogen interactions thus far shows potential for interfering with vector-borne disease transmission, but little has been done looking at the effects on vector fitness and viral pathogenesis. Our research confirms that fitness characteristics of Ae. aegypti vary largely between strains, but also can in some instances vary due to microflora presence or absence. Variations were not observed in response to dengue virus infection. When the mechanics and pathogenesis of the interactions between host, microbes and pathogens are better understood, novel vector-control strategies may be identified. Dissecting the complex network of these interactions will add an important component to our understanding of vector biology.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

We examined effects of midgut microbiota and dengue infection on Ae. aegypti fitness traits

Survivorship varied due to strain while one strain varied due to antibiotics

No effects on fertility in any strain

Fecundity varied in one strain due to antibiotics

No effects on fitness due to dengue infection

Overall, few effects were evident following microbial clearance or with dengue infection

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH FIRCA Grant R03 TW008138-01A1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Apte-Deshpande A, Paingankar M, Gokhale MD, Deobagkar DN. Serratia odorifera a midgut inhabitant of Aedes aegypti mosquito enhances its susceptibility to dengue-2 virus. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behura SK, Gomez-Machorro C, Harker BW, deBruyn B, Lovin DD. Global Cross-Talk of Genes of the Mosquito Aedes aegypti in Response to Dengue Virus Infection. PLoS Neglected Tropical Disease. 2011;5:e1385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett KE, Beaty BJ, Black WC. Selection of D2S3, an A. aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) strain with high oral susceptibility to Dengue 2 virus and D2MEB, a strain with a midgut barrier to Dengue 2 escape. Journal of Medical Entomology. 2005;42:110–119. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2005)042[0110:SODAAA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt S, Gething PW, Brady OJ, Messina JP, Farlow AW, Moyes CL, Drake JM, Brownstein JS, Hoen AG, Sankoh O, Myers MF, George DB, Jaenisch T, Wint GR, Simmons CP, Scott TW, Farrar JJ, Hay SI. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013;496:504–507. doi: 10.1038/nature12060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair CD, Adelman ZN, Olson KE. Molecular strategies for interrupting arthropod-borne virus transmission by mosquitoes. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2000;13:651–661. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.4.651-661.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadee DD, Rahaman A. Use of water drums by humans and Aedes aegypti in Trinidad. Journal of Vector Ecology. 2000;25:28–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charan SS, Pawar KD, Severson DW, Patole MS, Shouche YS. Comparative analysis of midgut bacterial communities of Aedes aegypti mosquito strains varying in vector competence to dengue virus. Parasitology Research. 2013;112:2627–2637. doi: 10.1007/s00436-013-3428-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan C, Behura SK, Debruyn B, Lovin DD, Harker BW, Gomez-Machorro C, Mori A, Romero-Severson J, Severson DW. Comparative expression profiles of midgut genes in dengue virus refractory and susceptible Aedes aegypti across critical period for virus infection. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirimotich CM, Dong Y, Garver LS, Dimopoulos G. Mosquito immune defenses against Plasmodium infection. Developmental and Comparative Immunology. 2010;34:387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirimotich CM, Dong Y, Clayton AM, Sandiford SL, Souza-Neto JA, Mulenga M, Dimopoulos G. Natural Microbe-Mediated Refractoriness to Plasmodium Infection in Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2011;332:855–858. doi: 10.1126/science.1201618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemons A, Mori A, Haugen M, Severson DW, Duman-Scheel M. Culturing and egg collection of Aedes aegypti. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2010;10 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5507. pdb.prot5507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho-Abreu IV, Zhu KY, Ramalho-Ortigao M. Transgenesis and paratransgenesis to control insect-borne diseases: current status and future challenges. Parasitology International. 2010;59:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dethlefsen L, McFall-Ngai M, Relman DA. An ecological and evolutionary perspective on human-microbe mutualism and disease. Nature. 2007;449:811–818. doi: 10.1038/nature06245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon RJ, Dillon VM. The gut bacteria of insects: nonpathogenic interactions. Annual Review of Entomology. 2004;49:71–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.49.061802.123416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Manfredini F, Dimopoulos G. Implication of the mosquito midgut microbiota in the defense against malaria parasites. PLoS Pathogens. 2009;5:e1000423. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas AE. The Symbiotic Habit. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ, USA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fouda MA, Hassan MI, Al-Daly AG, Hammad KM. Effect of midgut bacteria of Culex pipiens L. on digestion and reproduction. Journal of the Egyptian Society of Parasitology. 2001;3:767–780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaines PJ, Olson KE, Higgs S, Powers AM, Beaty BJ, Blair CD. Pathogen-derived resistance to dengue type 2 virus in mosquito cells by expression of the premembrane coding region of the viral genome. Journal of Virology. 1996;70:2132–2137. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2132-2137.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaio A, Gusmao DS, Santos AV, Berbert-Molina MA, Pimenta P, Lemos F. Contribution of midgut bacteria to blood digestion and egg production in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasites & Vectors. 2011;4:105. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley RE, Lozupone CA, Hamady M, Knight R, Gordon JI. Worlds within worlds: evolution of the vertebrate gut microbiota. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2008;6:776–788. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciel-de-Freitas R, Koella JC, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R. Lower survival rate, longevity and fecundity of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) females orally challenged with dengue virus serotype 2. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2011;105:452–8. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciel-de-Freitas R, Marques WA, Peres RC, Cunha SP, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R. Variation in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) container productivity in a slum and a suburban district in Rio de Janeiro during dry and wet seasons. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102:489–496. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762007005000056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciel-de-Freitas R, Sylvestre G, Gandini M, Koella JC. The Influence of Dengue Virus Serotype-2 Infection on Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) Motivation and Avidity to Blood Feed. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood F, Reisen WK, Chiles RE, Fang Y. Western equine encephalomyelitis virus infection affects the life table characteristics of Culex tarsalis (Diptera: Culicidae). Journal of Medical Entomology. 2004;41:982–986. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.5.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Jeffery JA, Lu G, Pyke AT, Hedges LM, Rocha BC, Hall-Mendelin S, Day A, Riegler M, Hugo LE, Johnson KN, Kay BH, McGraw EA, van den Hurk AF, Ryan PA, O'Neill SL. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, Chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell. 2009;139:1268–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourya DT, Gokhale MD, Pidiyar V, Barde PV, Patole M, Mishra AC, Shouche Y. Study of the effect of the midgut bacterial flora of Culex quinquefasciatus on the susceptibility of mosquitoes to Japanese encephalitis virus. Acta Virologica. 2002;46:257–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na'was TE, Hollis DG, Moss CW, Weaver RE. Comparison of biochemical, morphologic, and chemical characteristics of Centers for Disease Control fermentative coryneform groups 1, 2 and A-4. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1987;25:1354–1358. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.8.1354-1358.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nene V, Wortman JR, Lawson D, Haas B, Kodira C, Tu ZJ, Loftus B, Xi Z, Megy K, Grabherr M, Ren Q, Zdobnov EM, Lobo NF, Campbell KS, Brown SE, Bonaldo MF, Zhu J, Sinkins SP, Hogenkamp DG, Amedeo P, Arensburger P, Atkinson PW, Bidwell S, Biedler J, Birney E, Bruggner RV, Costas J, Coy MR, Crabtree J, Crawford M, Debruyn B, Decaprio D, Eiglmeier K, Eisenstadt E, El-Dorry H, Gelbart WM, Gomes SL, Hammond M, Hannick LI, Hogan JR, Holmes MH, Jaffe D, Johnston JS, Kennedy RC, Koo H, Kravitz S, Kriventseva EV, Kulp D, Labutti K, Lee E, Li S, Lovin DD, Mao C, Mauceli E, Menck CF, Miller JR, Montgomery P, Mori A, Nascimento AL, Naveira HF, Nusbaum C, O'leary S, Orvis J, Pertea M, Quesneville H, Reidenbach KR, Rogers YH, Roth CW, Schneider JR, Schatz M, Shumway M, Stanke M, Stinson EO, Tubio JM, Vanzee JP, Verjovski-Almeida S, Werner D, White O, Wyder S, Zeng Q, Zhao Q, Zhao Y, Hill CA, Raikhel AS, Soares MB, Knudson DL, Lee NH, Galagan J, Salzberg SL, Paulsen IT, Dimopoulos G, Collins FH, Birren B, Fraser-Liggett CM, Severson DW. Genome sequence of Aedes aegypti, a major arbovirus vector. Science. 2007;316:1718–23. doi: 10.1126/science.1138878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogge G. Sterility in tsetse flies (Glossina morsitans Westwood) caused by loss of symbionts. Experientia. 1976;32:995–996. doi: 10.1007/BF01933932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidiyar VJ, Jangid K, Patole MS, Shouche YS. Studies on cultured and uncultured microbiota of wild Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito midgut based on 16s ribosomal RNA gene analysis. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2004;70:597–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pumpuni CB, Demaio J, Kent M, Davis JR, Beier JC. Bacterial population dynamics in three anopheline species: the impact on Plasmodium sporogonic development. Amateur Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1996;54:214–218. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez JL, Souza-Neto J, Cosme RT, Rovira J, Ortiz A, Pascale JM, Dimopoulos G. Reciprocal Tripartite Interactions between the Aedes aegypti Midgut Microbiota, Innate Immune System and Dengue Virus Influences Vector Competence. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2012;6:e1561. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues J, Brayner FA, Alves LC, Dixit R, Barillas-Mury C. Hemocyte differentiation mediates innate immune memory in Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. Science. 2010;329:1353–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.1190689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutledge JC, Ward RA, Gould DJ. Studies on the feeding response of mosquitoes to nutritive solutions in a new membrane feeder. Mosquito News. 1964;24:407–419. [Google Scholar]

- Schlein Y, Polacheck I, Yuval B. Mycoses, bacterial infections and antibacterial activity in sandflies (Psychodidae) and their possible role in the transmission of leishmaniasis. Parasitology. 1985;90:57–66. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000049015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott TW, Naksathit A, Day JF, Kittayapong P, Edman JD. A fitness advantage for Aedes aegypti and the viruses it transmits when females feed only on human blood. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1997;57:235–239. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Dhayal D, Singh OP, Adak T, Bhatnagar RK. Gut microbes influence fitness and malaria transmission potential of Asian malaria vector Anopheles stephensi. Acta Tropica. 2013;128:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider JR, Mori A, Romero-Severson J, Chadee DD, Severson DW. Investigations of dengue-2 susceptibility and body size among Aedes aegypti populations. Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 2007;21:370–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2007.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessions OM, Barrows NJ, Souza-Neto JA, Robinson TJ, Hershey CL, Rodgers MA, Ramirez JL, Dimopoulos G, Yang PL, Pearson JL. Discovery of insect and human dengue virus host factors. Nature. 2009;458:1047–1050. doi: 10.1038/nature07967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styer LM, Meola MA, Kramer LD. West Nile virus infection decreases fecundity of Culex tarsalis females. Journal of Medical Entomology. 2007;44:1074–1085. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2007)44[1074:wnvidf]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terenius O, Lindh JM, Eriksson-Gonzales K, Bussiere L, Laugen AT, Bergquist H, Titanji K, Faye I. Midgut bacterial dynamics in Aedes aegypti. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 2012;80:556–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2012.01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thathy V, Severson DW, Christensen BM. Reinterpretation of the genetics of susceptibility of Aedes aegypti to Plasmodium gallinaceum. Journal of Parasitology. 1994;80:705–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touré AM, Mackey AJ, Wang ZX, Beier JC. Bactericidal effects of sugar-fed antibiotics on resident midgut bacteria of newly emerged anopheline mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). Journal of Medical Entomology. 2000;37:246–249. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/37.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vézilier J, Nicot A, Gandon S, Rivero A. Plasmodium infection decreases fecundity and increases survival of mosquitoes. The Proceedings of the Royal Society Biological Sciences. 2012;279:4033–4041. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welburn SC, Maudlin I. Tsetse–trypanosome interactions: rites of passage. Parasitology Today. 1999;15:399–403. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(99)01512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Z, Ramirez JL, Dimopoulos G. The Aedes aegypti toll pathway controls dengue virus infection. PLoS Pathogens. 2008;4:e1000098. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan G, Severson DW, Christensen BM. Costs and benefits of mosquito refractoriness to malaria parasites. Evolution. 1997;51:441–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb02431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye YH, Woolfit M, Rances E, O'Neill SL, McGraw EA. Wolbachia-associated bacterial protection in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2014;7:e2362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.