Abstract

Hydrogen/deuterium exchange coupled with mass spectrometry (HDX-MS or DXMS) has emerged as an important tool for the development of small molecule therapeutics and biopharmaceuticals. Central to these advances have been improvements to automated HDX-MS platforms and software that allow for the rapid acquisition and processing of experimental data. Correlating the HDX-MS profile of large numbers of ligands with their functional outputs has enabled the development of structure activity relationships (SAR) and delineation of ligand classes based on functional selectivity. HDX-MS has also been applied to address many of the unique challenges posed by the continued emergence of biopharmaceuticals. Here we review the latest applications of HDX-MS to drug discovery, recent advances in technology and software, and provide perspective on future outlook.

Keywords: HDX, HDX-MS, DXMS, Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange, Drug Discovery, Therapeutics, Small Molecule, SAR, Large Molecule, Biopharmaceutical, Nuclear Receptor, GPCR, PPARG, Functional Selective, Ligand Bias, Biosimilar

HDX-MS Introduction

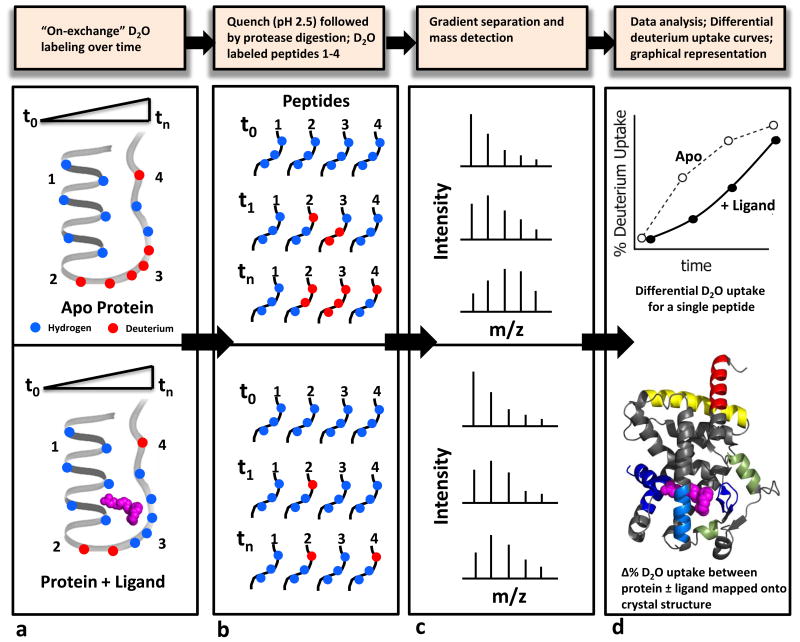

Hydrogen/deuterium exchange is an acid-base catalyzed reaction used to label proteins and report on the local environments of amide hydrogens. Coupling this approach with modern high-resolution mass spectrometry to monitor deuterium incorporation enables precise and sensitive data collection (<1ug/experiment at low μM concentration), and interrogation of large proteins and complexes [1-3]. Differential HDX-MS analysis of a protein under different conditions (e.g apo vs. holo protein) has emerged as an important tool to probe the effects of chemical modifications, mutations, and binding events on protein stability and conformational dynamics (Figure 1). The development of fully automated HDX platforms with improved software has enabled the rapid collection and near real-time processing of data with statistical analysis, a critical advancement for the integration of HDX-MS into drug discovery programs [4-9]. Correlating deuterium incorporation patterns from several small molecule ligands with functional assays has proven to be an effective approach to develop structure activity relationship and delineate functional selectivity between closely related compounds [10-13]. HDX-MS also provides a means to identify allosteric small molecule binding sites [2, 14, 15], which are often challenging to locate but desirable for the development of agents with improved selectivity.

Figure 1. Schematic of a typical HDX-MS workflow.

a. A protein sample in the absence or presence of a ligand (shown in magenta) is incubated at 4°C in D2O containing buffers for various time intervals b. After “on-exchange”, the protein is denatured and the deuterium uptake is quenched under acidic conditions (pH 2.5) at 0° C followed by proteolytic digestion using an on-line pepsin column c. Proteolytic peptides are then separated using a gradient column and subjected to mass determination using a high resolution mass spectrometer d. Average deuterium incorporation for each peptide over time is calculated from their mass shifts (top) and the differential HDX data (apo versus ligand bound) is overlaid onto an available three-dimensional structure (bottom). Regions that are differentially protected are color coded according to the HDX WorkBench software scheme.

The application of HDX-MS to the development and manufacturing of biological therapeutics reflects the unique challenges that face this class of drugs. HDX-MS has long been used to map the conformational epitopes of antibody-antigen complexes; however recent applications have focused on monitoring protein stability in response to chemical modifications, protein engineering, and alternative manufacturing processes [16]. These issues have emerged along with the rise of biopharmaceuticals and reflect the expanding focus on manufacturing quality control and defining standards for off-patent biosimilars [17]. Several in depth reviews have been published on the fundamentals of HDX-MS and its application to a range of biological systems [18-23]. Here we review the latest applications of HDX-MS to small molecule and biopharmaceutical drug discovery, the state of the art platform and software technologies, and directions for future development.

HDX-MS for Small Molecule Drug Discovery

Differential HDX-MS is a well-suited approach for interrogating the alterations in protein conformation induced by small molecule ligand binding [24]. The pharmacology of ligands have traditionally been categorized as agonists, partial agonists, antagonists, and inverse agonists depending on whether they fully or partially activate, block, or repress a protein's activity. While these classifications are informative, it has become clear that there is significantly more underlying complexity, and ligand classes can be further delineated. A comprehensive review of differential HDX-MS analysis of protein-ligand interactions has previously been published [22]. Here we focus on the most recent applications of HDX-MS to small molecules targeting the nuclear receptor (NR) and G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) protein families.

Nuclear receptors

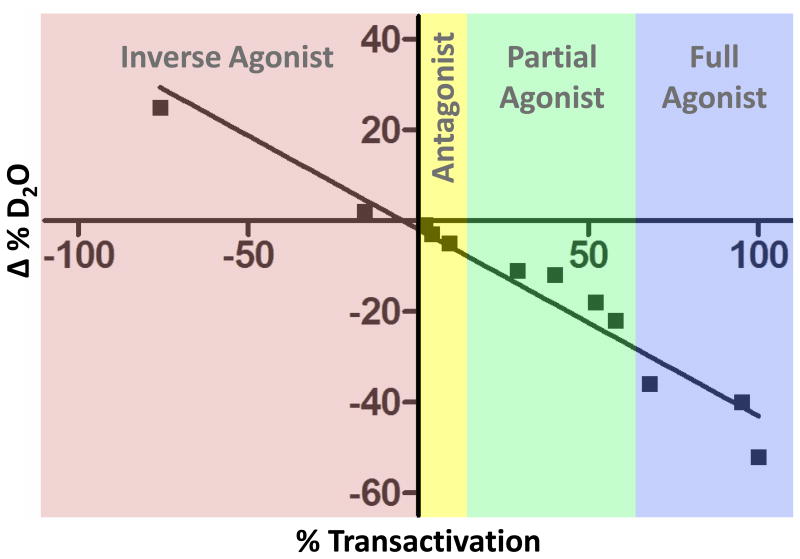

NRs are the pharmacological target of ∼10% of FDA approved drugs, a consequence of their implication in human disease and tractability for drug discovery [25]. The challenge of pharmacologically targeting NRs is achieving functional selectivity, a strategy to limit adverse effects due to the complex gene networks controlled by these ligand regulated transcription factors [26]. To that end, differential HDX-MS has been applied to characterize the effects of ligand binding on the isolated ligand binding domains (LBDs) of several NRs [11, 12, 27, 28], and was extended to identify intra-domain allosteric effects in a comprehensive analysis of the full length vitamin-D receptor (VDR) bound to DNA [29]. HDX-MS has been applied extensively to drug discovery efforts targeting the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), initially providing structural insights to delineate the thiazolidinedione and SPPARM (selective PPARγ modulator) ligand classes of PPARγ modulators [10, 30, 31]. More recently HDX-MS guided drug design was used to develop SR1664, a representative molecule from the novel class of Functional Selective PPARγ Modulators (FSPPARMs) that act as classical antagonists while modulating the obesity-induced phosphorylation of the receptor and a subset of target genes [32]. HDX-MS was also applied recently to support the finding that multiple ligand copies can bind concurrently to the PPARγ LBD, with the second lower affinity site having functional consequence at physiological concentrations that were previously unappreciated [33]. Together, these studies highlight the power of correlating subtle but statistically significant perturbations in receptor deuterium exchange with a range of functional assays to better define ligand classes, and to help guide improvement of their functional selectivity and ultimately their therapeutic index (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Correlating HDX-MS with functional output.

Analysis of pharmacologically distinct PPARγ ligands for both cellular transactivation and HDX demonstrates a strong correlation between helix 12 peptide (SLHPLLQEIYKDLY) protection and receptor activity. Thus, HDX can be used as a predictive assay to support lead optimization of functional selective PPARγ modulators (FSPPARMs).

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs)

GPCRs constitute the largest family of cell surface signaling proteins, relaying extracellular signals into intracellular responses to maintain cellular homeostasis. This transduction is achieved through ligand-induced alterations to the equilibrium of conformational ensembles, and is typically accompanied by allosteric changes to distal regions of the receptor. Activation of GPCRs by endogenous ligands or synthetic pharmacophores drives downstream signaling events that are mediated by G proteins, β-Arrestins, and GPCR kinases (GRKs). Dysregulation of GPCR function is the underlying cause of many human diseases; a primary reason GPCRs are targeted by nearly half of currently approved drugs [34, 35]. Similar to NRs, recent advances have revealed the complexity of GPCR function as more than a binary on/off switch modulated by agonists and antagonists, with modern pharmacology paradigms of allosteric modulation and ligand bias providing strategies to fine-tune receptor signaling [36-39].

HDX-MS has emerged as an important tool for probing the conformational ensembles and allosteric changes of GPCRs, complementing what can be garnered from other structural techniques such as NMR and crystallography. The primary hurdle for the initial application of HDX-MS to interrogate GPCRs was identifying mass spectrometry compatible detergents that would maintain protein solubility. These conditions were first reported in a study profiling the ligand-dependent perturbations to β2-adrenergic receptor (β2-AR) in response to the inverse agonist carazolol [40]. This study enabled a more rigorous HDX-MS analysis of β2-AR in the presence of a range of ligands from full agonist to inverse agonist [41]. Together, these findings illustrate that the intra- and extracellular loop regions of β2-AR, previously unresolved or truncated in crystal structures, exhibit unique HDX perturbations in response to functionally-distinct ligands and provide a strategy to distinguish novel β2-AR modulators with desired physiological response. To further study the molecular underpinnings of G protein activation by agonist-bound β2-AR, HDX-MS was applied to identify structural links between the receptor-binding surface and nucleotide-binding pocket of the G protein, providing a rationale for the mechanism of activation [42]. While this study provided critical insights into G protein signal transduction and function, β2-AR coverage was not obtained, likely the result of ion suppression due to the poor digestion efficiency of GPCRs relative to soluble proteins. This limitation highlights the technical challenge of improving GPCR digestion efficiency, which may be aided by recent additions to the repertoire of HDX compatible proteases [43, 44], or by applying affinity capture to remove the cytosolic G proteins prior to proteolytic digestion [45]. An alternative strategy to improve digestion efficiency may be to utilize more native-like nanodiscs to reconstitute β2-AR in the absence of detergent micelles as recently demonstrated with transmembrane protein Gamma-glutamyl carboxylase (GGCX) [46].

HDX-MS and Biopharmaceuticals

Biopharmaceuticals have had continued success and are projected to account for the majority of newly FDA approved drugs in the near future [47]. Biopharmaceuticals such as monoclonal antibodies, synthetic peptides and recombinant proteins have their own unique development challenges, but can be exquisitely selective relative to small molecules contributing to their generally excellent safety profiles (excluding mechanism based side effects). Previous reviews have focused on the expanding role of HDX-MS to process related aspects of biopharmaceuticals such as manufacturing quality control of recombinant molecules [16], as well as defining ‘similarity’ guidelines for off-patent biosimilars [48]. Here we present a focused review of recent HDX-MS applications to protein therapeutic discovery.

Therapeutic Antibody Development

HDX-MS has proven a robust contributor in the development of monoclonal antibody therapeutics, as a reliable method for conformational epitope mapping of antibody-antigen interactions in their native solution state [16, 49, 50]. Mapping of conformational epitopes has traditionally been accomplished by alanine scanning mutagenesis, protease-protection experiments, or x-ray crystallography, which can be labor intensive with each approach having unique limitations [50]. Recent studies have utilized improvements in instrumentation to probe antibody-antigen epitopes of larger, more biologically relevant protein complexes [51-56]. Furthering these studies has demonstrated the role of chemical modifications on the global conformation of monoclonal antibodies and the potential impact on therapeutic efficacy and safety [57]. The stability of monoclonal antibodies engineered with alternative domain substitutions has been measured with HDX-MS, highlighting the potential for novel therapeutic motifs and improved pharmacokinetics [58]. The specificity of monoclonal antibodies has been harnessed for targeted delivery of Antibody-Drug conjugates (ADCs) with a particular focus on chemotherapeutic agents in the current pipeline [59]. HDX-MS has been applied to interrogate the higher-order structure of ADCs to evaluate how the process of drug conjugation impacts the conformation and dynamics of the monoclonal antibody [60].

Recombinant Protein Therapeutics

Protein based therapeutic development, which dates back 30 years to the introduction of recombinant insulin, has also benefited from the application of HDX-MS [61]. The oligomeric state and stability of insulin analogs were monitored with HDX-MS in back to back reports, and demonstrated to be predictive of pharmacokinetic properties such as onset and duration [62, 63]. β-glucocerebrosidase (GCase) is an essential metabolic enzyme whose dysfunction due to naturally occurring mutations results in the most prevalent lysosomal storage disorder Type 1 Gaucher's disease. Enzyme replacement therapy consists of intravenous infusion of recombinant GCase and HDX-MS has been applied to characterize the effect of oxidation on protein stability and dynamics [64]. This series of reports demonstrates the varied applications of HDX-MS to biopharmaceutical discovery and development, an area that is likely to see continued expansion in the coming years.

HDX-MS Technologies and Future Directions

The sophistication of HDX-MS technology has matured considerably over the past decade, evolving from labor-intensive manual bench top experiments to fully automated experimental platforms. Improvements to HDX-MS spatial resolution, from peptide level to single residue have been demonstrated by several groups in recent years with the application of electron-capture and electron-transfer dissociation fragmentation [65-69]. While the requirements for these approaches suggest that they are unlikely to become routine in the near future, combining newly developed HDX-MS compatible proteases may provide a feasible strategy to improve spatial resolution through subtractive analysis. Efforts to advance the detection limits of HDX-MS to sub-second time scales for the purpose of interrogating rapidly exchanging systems have been achieved through the development of micro-fluidic chips [70-72], as well as simulated approaches compatible with automated platforms [73].

The impact that several research groups have had on the field over the past decade has led to instrument manufacturers now selling fully automated HDX-MS systems. This has made HDX-MS more accessible with reduced cost per experiment and significantly higher sample throughput For drug discovery efforts, the application of HDX-MS to high-throughput screening appears to be a natural progression for which the principles have been described previously [74, 75]. From a broader perspective, HDX-MS will continue to be used in parallel with the repertoire of available structural approaches such as crystallography [10], NMR [31, 76, 77], SAXS [78-80], and Cryo-EM [81-84] to tackle challenging biological questions that require multiple approaches. Protein structural plasticity is directly linked to protein function, and as such HDX will continue to play a significant role in understanding the link between protein structure and activity. These are exciting times for HDX-MS and we expect the field to continue growing, as the barrier for entry has been lowered and the diversity of applications expanded.

Highlights.

HDX-MS has been applied to develop both small and large molecule therapeutics.

Recent improvements to experimental platforms and software have increased throughput.

Correlating HDX-MS with functional assays enables small molecule SAR development.

HDX-MS can address many of the unique challenges of biopharmaceutical development.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge funding from NIH (MH0845412 PI: H. Rosen) and GM103368-02 (PI: A. Olsen).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

* of interest

** of considerable interest

- 1.Zhang J, et al. DNA binding alters coactivator interaction surfaces of the intact VDR-RXR complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18(5):556–63. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2*.Landgraf RR, et al. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase revealed by hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. Structure. 2013;21(11):1942–53. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.08.023. HDX-MS characterization of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) reveals an allosteric binding site and alternative mechanism of activation. AMPK is a 140kD protein that approaches the current upper limits of HDX-MS and this reports demonstrates the mechanistic insights that can be garnered from differential HDX studies with small molecules. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goswami D, et al. Influence of domain interactions on conformational mobility of the progesterone receptor detected by hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. Structure. 2014;22(7):961–73. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4**.Pascal BD, et al. HDX workbench: software for the analysis of H/D exchange MS data. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23(9):1512–21. doi: 10.1007/s13361-012-0419-6. HDX Workbench is open source software designed to rapidly process data with statistical analysis and is compatible with multiple mass spectrometer outputs. This development has significantly improved the throughput of HDX-MS enabling drug discovery application. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Z, Zhang A, Xiao G. Improved protein hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry platform with fully automated data processing. Anal Chem. 2012;84(11):4942–9. doi: 10.1021/ac300535r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Venable JD, Scuba W, Brock A. Feature based retention time alignment for improved HDX MS analysis. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2013;24(4):642–5. doi: 10.1007/s13361-012-0566-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chalmers MJ, et al. Methods for the Analysis of High Precision Differential Hydrogen Deuterium Exchange Data. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2011;302(1-3):59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chalmers MJ, et al. Probing protein ligand interactions by automated hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2006;78(4):1005–14. doi: 10.1021/ac051294f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindner R, et al. Hexicon 2: automated processing of hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry data with improved deuteration distribution estimation. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2014;25(6):1018–28. doi: 10.1007/s13361-014-0850-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruning JB, et al. Partial agonists activate PPARgamma using a helix 12 independent mechanism. Structure. 2007;15(10):1258–71. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chalmers MJ, et al. Hydrophobic Interactions Improve Selectivity to ERalpha for Benzothiophene SERMs. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2012;3(3):207–210. doi: 10.1021/ml2002532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dai SY, et al. Unique ligand binding patterns between estrogen receptor alpha and beta revealed by hydrogen-deuterium exchange. Biochemistry. 2009;48(40):9668–76. doi: 10.1021/bi901149t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dai SY, et al. Prediction of the tissue-specificity of selective estrogen receptor modulators by using a single biochemical method. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(20):7171–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710802105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewallen DM, et al. Inhibiting AMPylation: a novel screen to identify the first small molecule inhibitors of protein AMPylation. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9(2):433–42. doi: 10.1021/cb4006886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huzil JT, et al. A unique mode of microtubule stabilization induced by peloruside A. J Mol Biol. 2008;378(5):1016–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wei H, et al. Hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry for probing higher order structure of protein therapeutics: methodology and applications. Drug Discov Today. 2014;19(1):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17*.Visser J, et al. Physicochemical and functional comparability between the proposed biosimilar rituximab GP2013 and originator rituximab. BioDrugs. 2013;27(5):495–507. doi: 10.1007/s40259-013-0036-3. Application of a range of strucutral and biophysical approaches including HDX-MS to compare biosimilar GP2013 and originator rituximab. This report highlights the emerging role of HDX-MS to characterize biopharmaceuticals and address many of their unique developmental challenges. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Englander SW. Hydrogen exchange and mass spectrometry: A historical perspective. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2006;17(11):1481–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaltashov IA, Bobst CE, Abzalimov RR. H/D exchange and mass spectrometry in the studies of protein conformation and dynamics: is there a need for a top-down approach? Anal Chem. 2009;81(19):7892–9. doi: 10.1021/ac901366n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woods VL, Jr, Hamuro Y. High resolution, high-throughput amide deuterium exchange-mass spectrometry (DXMS) determination of protein binding site structure and dynamics: utility in pharmaceutical design. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 2001;(Suppl 37):89–98. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engen JR. Analysis of protein conformation and dynamics by hydrogen/deuterium exchange MS. Anal Chem. 2009;81(19):7870–5. doi: 10.1021/ac901154s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chalmers MJ, et al. Differential hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry analysis of protein-ligand interactions. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2011;8(1):43–59. doi: 10.1586/epr.10.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang RY, Chen G. Higher order structure characterization of protein therapeutics by hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-7924-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24**.Sowole MA, Konermann L. Effects of protein-ligand interactions on hydrogen/deuterium exchange kinetics: canonical and noncanonical scenarios. Anal Chem. 2014;86(13):6715–22. doi: 10.1021/ac501849n. Protein-ligand interactions are typically characterized by increased protection from deuterium exchange. This study is the first to demonstrate and rationalize increased exchange as a viable outcome for ligand binding events. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rask-Andersen M, Masuram S, Schioth HB. The druggable genome: Evaluation of drug targets in clinical trials suggests major shifts in molecular class and indication. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;54:9–26. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011613-135943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marciano DP, et al. The therapeutic potential of nuclear receptor modulators for treatment of metabolic disorders: PPARgamma, RORs, and Rev-erbs. Cell Metab. 2014;19(2):193–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar N, et al. Probe Reports from the NIH Molecular Libraries Program. Bethesda (MD): 2010. Identification of a novel selective inverse agonist probe and analogs for the Retinoic acid receptor-related Orphan Receptor Gamma (RORgamma) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang L, et al. Conformational dynamics of human FXR-LBD ligand interactions studied by hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry: Insights into the antagonism of the hypolipidemic agent Z-guggulsterone. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1844(9):1684–1693. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J, et al. Hydrogen/deuterium exchange reveals distinct agonist/partial agonist receptor dynamics within vitamin D receptor/retinoid X receptor heterodimer. Structure. 2010;18(10):1332–41. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamuro Y, et al. Hydrogen/deuterium-exchange (H/D-Ex) of PPARgamma LBD in the presence of various modulators. Protein Sci. 2006;15(8):1883–92. doi: 10.1110/ps.062103006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hughes TS, et al. Ligand and receptor dynamics contribute to the mechanism of graded PPARgamma agonism. Structure. 2012;20(1):139–50. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi JH, et al. Antidiabetic actions of a non-agonist PPARgamma ligand blocking Cdk5-mediated phosphorylation. Nature. 2011;477(7365):477–81. doi: 10.1038/nature10383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hughes TS, et al. An alternate binding site for PPARgamma ligands. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3571. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stevens RC, et al. The GPCR Network: a large-scale collaboration to determine human GPCR structure and function. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(1):25–34. doi: 10.1038/nrd3859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wise A, Gearing K, Rees S. Target validation of G-protein coupled receptors. Drug Discov Today. 2002;7(4):235–46. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(01)02131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luttrell LM. Minireview: more than just a hammer: ligand “bias” and pharmaceutical discovery. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28(3):281–94. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kenakin T, Christopoulos A. Signalling bias in new drug discovery: detection, quantification and therapeutic impact. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(3):205–16. doi: 10.1038/nrd3954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valant C, et al. The best of both worlds? Bitopic orthosteric/allosteric ligands of g protein-coupled receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:153–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marti-Solano M, et al. Novel insights into biased agonism at G protein-coupled receptors and their potential for drug design. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19(28):5156–66. doi: 10.2174/1381612811319280014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang X, et al. Dynamics of the beta2-adrenergic G-protein coupled receptor revealed by hydrogen-deuterium exchange. Anal Chem. 2010;82(3):1100–8. doi: 10.1021/ac902484p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41*.West GM, et al. Ligand-dependent perturbation of the conformational ensemble for the GPCR beta2 adrenergic receptor revealed by HDX. Structure. 2011;19(10):1424–32. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.08.001. HDX-MS profiling of a range of ligands on native β2AR identifying perturbations in regions of the receptor not resolved in the crystal structure. This study required the use of HDX compatible detergents broadly applicable to GPCRs and demonstrates the utility of correlating HDX with fucntional assays. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42*.Chung KY, et al. Conformational changes in the G protein Gs induced by the beta2 adrenergic receptor. Nature. 2011;477(7366):611–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10488. HDX-MS monitoring of G protein conformational changes induced by β2AR activation. This study profiled the effects of various guanosine nucleotides on the intact β2AR/G protein complex and provides insights into the structural mechanism for GPCR signal transduction. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rey M, et al. Nepenthesin from monkey cups for hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12(2):464–72. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.025221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kadek A, et al. Aspartic protease nepenthesin-1 as a tool for digestion in hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2014;86(9):4287–94. doi: 10.1021/ac404076j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jensen PF, et al. Affinity capture of biotinylated proteins at acidic conditions to facilitate hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry analysis of multimeric protein complexes. Anal Chem. 2013;85(15):7052–9. doi: 10.1021/ac303442y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hebling CM, et al. Conformational analysis of membrane proteins in phospholipid bilayer nanodiscs by hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2010;82(13):5415–9. doi: 10.1021/ac100962c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reichert JM. Which are the antibodies to watch in 2013? MAbs. 2013;5(1):1–4. doi: 10.4161/mabs.22976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berkowitz SA, et al. Analytical tools for characterizing biopharmaceuticals and the implications for biosimilars. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11(7):527–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd3746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang H, Cui W, Gross ML. Mass spectrometry for the biophysical characterization of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. FEBS Lett. 2014;588(2):308–17. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abbott WM, Damschroder MM, Lowe DC. Current approaches to fine mapping of antigen antibody interactions. Immunology. 2014 doi: 10.1111/imm.12284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Q, et al. Epitope mapping of a 95 kDa antigen in complex with antibody by solution-phase amide backbone hydrogen/deuterium exchange monitored by Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2011;83(18):7129–36. doi: 10.1021/ac201501z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sevy AM, et al. Epitope mapping of inhibitory antibodies targeting the C2 domain of coagulation factor VIII by hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(12):2128–36. doi: 10.1111/jth.12433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bereszczak JZ, et al. Epitope-distal effects accompany the binding of two distinct antibodies to hepatitis B virus capsids. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135(17):6504–12. doi: 10.1021/ja402023x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pandit D, et al. Mapping of discontinuous conformational epitopes by amide hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry and computational docking. J Mol Recognit. 2012;25(3):114–24. doi: 10.1002/jmr.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Serruto D, et al. The new multicomponent vaccine against meningococcal serogroup B, 4CMenB: immunological, functional and structural characterization of the antigens. Vaccine. 2012;30(Suppl 2):B87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Willison LN, et al. Conformational epitope mapping of Pru du 6, a major allergen from almond nut. Mol Immunol. 2013;55(3-4):253–63. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang A, et al. Understanding the Conformational Impact of Chemical Modifications on Monoclonal Antibodies with Diverse Sequence Variations Using HDX-MS and Structural Modeling. Anal Chem. 2014 doi: 10.1021/ac404130a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Y, et al. An antibody with a variable-region coiled-coil “knob” domain. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53(1):132–5. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zolot RS, Basu S, Million RP. Antibody-drug conjugates. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(4):259–60. doi: 10.1038/nrd3980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pan LY, Salas-Solano O, Valliere-Douglass JF. Conformation and dynamics of interchain cysteine-linked antibody-drug conjugates as revealed by hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2014;86(5):2657–64. doi: 10.1021/ac404003q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Qiang G, et al. Identification of a small molecular insulin receptor agonist with potent antidiabetes activity. Diabetes. 2014;63(4):1394–409. doi: 10.2337/db13-0334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62*.Nakazawa S, et al. Analysis of oligomeric stability of insulin analogs using hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2012;420(1):61–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.09.002. Analysis of the oligomeric states of therapeutic insulin analogs and correlation with their pharmacokinetics using HDX-MS. This report demonstrates the ability to interogate large complexes with HDX-MS and the technique's application to large molecule therapeutics development. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakazawa S, et al. Analysis of the local dynamics of human insulin and a rapid-acting insulin analog by hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1834(6):1210–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bobst CE, et al. Impact of oxidation on protein therapeutics: conformational dynamics of intact and oxidized acid-beta-glucocerebrosidase at near-physiological pH. Protein Sci. 2010;19(12):2366–78. doi: 10.1002/pro.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rand KD, Jorgensen TJ. Development of a peptide probe for the occurrence of hydrogen (1H/2H) scrambling upon gas-phase fragmentation. Anal Chem. 2007;79(22):8686–93. doi: 10.1021/ac0710782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Abzalimov RR, Bobst CE, Kaltashov IA. A new approach to measuring protein backbone protection with high spatial resolution using H/D exchange and electron capture dissociation. Anal Chem. 2013;85(19):9173–80. doi: 10.1021/ac401868b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rand KD, et al. Site-specific analysis of gas-phase hydrogen/deuterium exchange of peptides and proteins by electron transfer dissociation. Anal Chem. 2012;84(4):1931–40. doi: 10.1021/ac202918j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Landgraf RR, Chalmers MJ, Griffin PR. Automated hydrogen/deuterium exchange electron transfer dissociation high resolution mass spectrometry measured at single-amide resolution. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23(2):301–9. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0298-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pan J, et al. Structural interrogation of electrosprayed peptide ions by gas-phase H/D exchange and electron capture dissociation mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2012;84(1):373–8. doi: 10.1021/ac202730d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rob T, et al. An electrospray ms-coupled microfluidic device for sub-second hydrogen/deuterium exchange pulse-labelling reveals allosteric effects in enzyme inhibition. Lab Chip. 2013;13(13):2528–32. doi: 10.1039/c3lc00007a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rob T, et al. Measuring dynamics in weakly structured regions of proteins using microfluidics-enabled subsecond H/D exchange mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2012;84(8):3771–9. doi: 10.1021/ac300365u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Resetca D, Wilson DJ. Characterizing rapid, activity-linked conformational transitions in proteins via sub-second hydrogen deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. FEBS J. 2013;280(22):5616–25. doi: 10.1111/febs.12332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Goswami D, et al. Time window expansion for HDX analysis of an intrinsically disordered protein. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2013;24(10):1584–92. doi: 10.1007/s13361-013-0669-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chalmers MJ, et al. A two-stage differential hydrogen deuterium exchange method for the rapid characterization of protein/ligand interactions. J Biomol Tech. 2007;18(4):194–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75*.Carson MW, et al. HDX reveals unique fragment ligands for the vitamin D receptor. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014;24(15):3459–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.05.070. Structure-guided fragment-based drug design is an important tool for therapeutic development that has previously been coupled with protein crystallography and NMR. This is the first report applying HDX-MS to screen fragment hits as starting points for synthetic expansion. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wilderman PR, Halpert JR. Plasticity of CYP2B enzymes: structural and solution biophysical methods. Curr Drug Metab. 2012;13(2):167–76. doi: 10.2174/138920012798918417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cierpicki T, et al. The solution structure and dynamics of the DH-PH module of PDZRhoGEF in isolation and in complex with nucleotide-free RhoA. Protein Sci. 2009;18(10):2067–79. doi: 10.1002/pro.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Davenport TM, et al. Isolate-specific differences in the conformational dynamics and antigenicity of HIV-1 gp120. J Virol. 2013;87(19):10855–73. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01535-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Walters BT, et al. Folding of a large protein at high structural resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(47):18898–903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319482110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Winkler A, et al. Characterization of elements involved in allosteric light regulation of phosphodiesterase activity by comparison of different functional BlrP1 states. J Mol Biol. 2014;426(4):853–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aiyegbo MS, et al. Differential accessibility of a rotavirus VP6 epitope in trimers comprising type I, II, or III channels as revealed by binding of a human rotavirus VP6-specific antibody. J Virol. 2014;88(1):469–76. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01665-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Noble AJ, et al. A pseudoatomic model of the COPII cage obtained from cryo-electron microscopy and mass spectrometry. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20(2):167–73. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Domitrovic T, et al. Virus assembly and maturation: auto-regulation through allosteric molecular switches. J Mol Biol. 2013;425(9):1488–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kirschke E, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor function regulated by coordinated action of the hsp90 and hsp70 chaperone cycles. Cell. 2014;157(7):1685–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]