Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study was to evaluate in vitro the effect of photodynamic therapy (PDT) using LASER or light emitting diode (LED) on cariogenic bacteria (Streptococcus mutans [SM] and Lactobacillus casei [LC]) in bovine dentin.

Materials and Methods:

Twenty five fragments of dentin were contaminated with SM and LC strands and divided into five experimental groups according to the therapy they received (n = 5): C – control (no treatment), SCLED – no dye/LED application (94 J/cm2), SCLASER – no dye/LASER application (94 J/cm2), CCLED – dye/LED application (94 J/cm2) and CCLASER – dye/LASER application (94 J/cm2). The dye used was methylene blue at 10 mM. Dentin scrapes were harvested from each fragment and prepared for counts of colony forming units (CFU)/mL. The data were analyzed using Kruskal–Wallis, followed by Student–Newman–Keuls (α =0.05).

Results:

Regarding SM, groups CCLASER and CCLED showed a significant reduction in CFU/mL, which was statistically superior to the SCLASER, SCLED and C groups. Regarding LC, the groups CCLASER and CCLED caused a significant reduction in CFU/mL when compared with SCLASER, which showed intermediate values. SCLED and C had a lesser effect on reducing CFU/mL, where the former showed values similar to those of SCLASER.

Conclusions:

In conclusion, PDT combined with LASER or LED and methylene blue had a significant antimicrobial effect on cariogenic bacteria in the dentin.

Keywords: Lactobacillus casei, photodynamic therapy, semi-conductor lasers, Streptococcus mutans

INTRODUCTION

Photodynamic therapy, also known as PDT, combines the use of nontoxic photosensitizing dyes with a visible light of the appropriate wavelength.[1] Photosensitive substances absorb energy from light and become activated, producing highly reactive oxygen species, which results in cell damage and cell death.[2] PDT has been used in many situations, including cutaneous lesions, burns, skin cancer, leishmaniosis, etc.[3,4,5,6,7]

In dentistry, PDT has been investigated for the treatment of oral infections, such as caries, pulpitis, periodontal disease, mucosal and endodontic infections.[8,9,10,11,12,13] In the specific case of caries, PDT has shown promising results in inactivating cariogenic microorganisms[14] in the biofilm[9,15,16] or carious dentine.[17,18] Due to PDT-induced decontamination, one may speculate that post-PDT caries removal may be performed conservatively.[19] In addition, PDT can be regarded as selective that is, neither the photosensitizer nor the light shows bactericidal properties when used separately. Consequently, antimicrobial activity is achieved by combining the dye with light simultaneously, thus not disturbing the flora at distant sites.[20,21] Another important aspect of this approach is its atraumatic nature, which could be indicated especially for patients with special needs and children.[1,16]

There are several types of photosensitizing agents, light sources and protocols, which are currently been investigated in terms of compositions, light-absorbing properties, etc. Such vast array of options tends to hinder the establishment of defined parameters for the use of PDT to eliminate cariogenic bacteria. Light source devices can be equipped with a halogen light,[11,22,23] light emitting diode (LED),[1,9,17,18,24] laser diode[15,19,25] and HeNe.[9]

Light emitting diode devices have the advantage of their applicability on PDT, since when compared with low-intensity lasers, they also produce light at a specific wavelength, however, within a wider electromagnetic spectrum range and at a lower cost, which makes it accessible.[1,9,16] Nevertheless, despite numerous reports on either technique, comparisons between the two light sources are scarce in the literature. Therefore, the aim of this study was to compare the antimicrobial effect of PDT using diode laser and LED combined with methylene blue dye.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical issues

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee in Animal Research (CEUA) of the Sao Leopoldo Mandic Dental School and Postgraduate Research Center, registration number 2012/0378.

Study design

The method used in this study was based on Lima et al.[17] This in vitro investigation was composed of 25 experimental units randomly divided into five experimental groups, according to the therapy used on bovine dentin (n = 5): C – control (no treatment); SCLED – LED application (94 J/cm2) without a dye; SCLASER – LASER application (94 J/cm2) without a dye; CCLED – LED application (94 J/cm2) with the dye; CCLASER – LED application (94 J/cm2) with the dye.

The quantitative response variable to treatment was the count of colony forming units (CFU)/mL.

Preparation of the dentin specimens

Fragments of dentin measuring 5 × 5 × 2 mm were prepared from bovine incisors using a flexible high concentration diamond disk (104 mm diameter × 0.3 mm thick), series 15 HC (Buehler Ltd., Lake Bluff, Illinois, USA) mounted on a precision saw (Isomet 1000 Precision Diamond Saw, Buehler Ltd., Lake Bluff, Illinois, USA). Two sections were carried out 5 mm apart to standardize the fragments. All 50 fragments were polished under water cooling (Politriz Aropol 2V, Arotec, São Paulo, SP, Brazil) using a sequential grains of aluminum oxide sandpaper (Imperial Wetordry, 3M, Sumaré, SP, Brazil) – number 400, number 600 and number 1200 - so that the final depth of the specimen was standardized at 2 mm.

Protocol of contamination

Activation of the strands of Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus casei

Streptococcus mutans (SM) and Lactobacillus casei (LC) strands were cultured in brain heart infusion (BHI) for 24 h and 48 h at 36 ± 1°C, following activation. The microorganisms were then gram tested, suspended in 2 mL sterile saline to obtain quantities of viable colonies.

Strand activation was performed according to the following procedure:

Hydration of the primary culture: Standard strands were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), with a certificate of origin obtained from the André Tosello Foundation. From the lyophilized ATCC or the collection cultures, stationary-phase cultures were prepared following the instructions provided with the certificate: Disinfection of the upper aspect of the ampoule, identification of the mid-point of the cotton plug using a file or a diamond-tip pen, removal of the upper aspect of the broken ampoule using a sterile forceps, disposal of the fragments in disinfectant solution. Using a sterile Pasteur pipette, 1 mL of the recommended medium was added to the culture, the suspension was gently homogenized, left to rest for a few minutes and transferred into tubes containing the specific medium for each microorganism. The samples were then incubated for the recommended amount of time for each microorganism. Whenever growth was not detected, the suspensions were left to incubate for up to twice the recommended time, before assuming that the culture was not viable. The primary culture was preserved so as to maintain its morphological, physiological and genetic features, as well as its viability during the storage period

Preparation of the secondary culture: A tube was removed from the frozen primary culture stock for reactivation. It was defrosted in ice and subsequently transferred to a test tube containing 5 mL of growth medium (specific for each microorganism), which was incubated and activated.

Bacterial inoculation

The teeth were autoclaved for 15 min at 121°C, dried using absorbent paper and divided into two groups (n = 5), according to the type of bacteria to be inoculated:

The teeth were placed in receptacles containing 1.5 × 108 CFU/mL of SM suspension (BHI medium)

The remaining teeth were placed in receptacles containing 10 μL of 1.4 × 107 CFU/mL of LC suspension (MRS medium), followed by incubation at 37°C and CO2.

Photosensitizing agent and light

The photosensitizing agent used was methylene blue at 10 mM, filtered through a sterile 20-μm mesh membrane filter and stored in the dark. For the experiments, 100 μM (100 × dilution) aliquots were prepared using distilled water (Batista, accepted in 2011).

Irradiation protocol

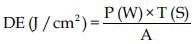

According to the method proposed by Lima et al.[17] 94 J/cm2 of energy was the most effective parameter in PDT for carious dentin. Therefore, the calculation of the irradiation needed to achieve 94 J/cm2 for LASER and LED was performed using the following formula:

Where: DE = Energy density; P = Power; T = Irradiation time, A = Area of the device tip.

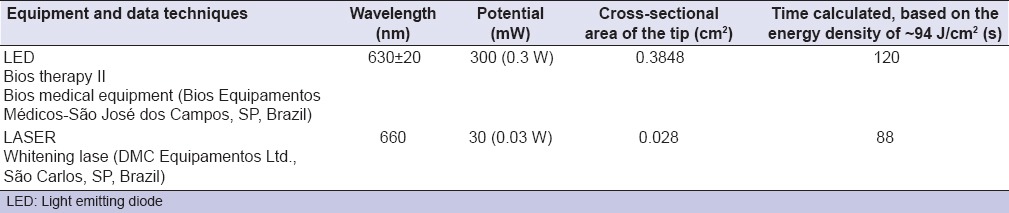

Table 1 shows the data used to calculate irradiation time. Irradiation was carried out from a distance of 2 cm.

Table 1.

Data relating to the equipment tested and the time calculated for irradiation

Microbiological analysis

Dentin samples were collected from the fragments using a microbrush embedded in saline solution. The material collected was placed in Eppendorf tubes containing 1000 μL of BHI. Two dilutions were made from the original suspension to place the samples in. Ten microliter from each dilution was inoculated into a specific medium in duplicates. SM and LC growth was determined by counts of colony forming units in viable plates of medium:

SM: MSB agar (Mitis salivarius agar);

LC: MRS agar (de Man, Rogosa, Sharpe).

Statistical analysis

In order to check for data distribution error, exploratory analysis was performed on SPSS 20.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL, EUA), which demonstrated that the data did not conform to a normal distribution, thus not fulfilling the requirements for analysis of variance. No transformation was possible to adjust the Gauss curve, consequently; nonparametric tests were selected, namely Kruskal–Wallis for two variables (CFU/mL of SM and of LC), followed by Student–Newman–Keuls for multiple comparisons. The significance level adopted was 5%.

RESULTS

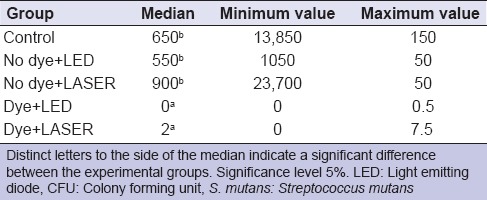

Kruskal–Wallis test demonstrated no significant difference (P < 0.05) between the SM groups in terms of CFU/mL [Table 2]. The Student–Newman–Keuls test revealed that the use of methylene blue alone, that is, without LED or LASER, led to a significant reduction in CFU/mL of SM when compared to the control group.

Table 2.

Median, minimum and maximum values of CFU/mL for the group contaminated with S. mutans

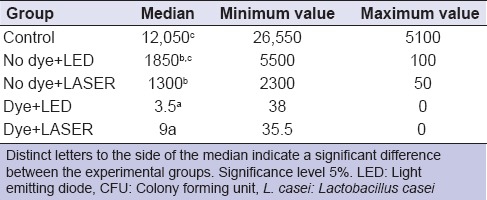

Kruskal–Wallis test demonstrated a significant difference between the LC groups (P < 0.05) [Table 3]. The Student–Newman–Keuls test revealed that the use of methylene blue alone, that is, without LED or LASER, significantly reduced the CFU/mL of LC when compared with the control and the remaining groups. The control group had the highest CFU/mL of LC, which was statistically similar to the no dye/LED (SCLED) group. The group where LASER alone was used without the dye showed intermediate CFU/mL values, which were significantly lower than the control group and similar to the group where LED was used alone without the dye (SCLED).

Table 3.

Median, minimum and maximum values for the CFU/mL for the group contaminated with L. casei

DISCUSSION

Photodynamic therapy is characterized by the use of light to activate a photosensitive agent in the presence of oxygen, resulting in reactive species in situ, the oxygen singlet, which can induce cell death.[26] It has been considered a promising alternative to the classic treatment of dental caries. In vitro[9,11,16,23,24,25] and in situ[16,17] studies have demonstrated the sensitivity of bacteria such as SM and LC to this treatment. Although studies have demonstrated that the combination of light and a dye is an effective approach to inactivate microbials, some variables still influence the outcome, such as the nature and concentration of the dye, the cariogenic microorganism species, the light source, as well as the duration and dose of exposure to light. The effect of these factors on the success of PDT has been the target of much investigation that seeks to make it a feasible method to control various infections in clinical practice.[14,15,17,23,24,25,27,28]

The results of this study have demonstrated a significant reduction in SM and LC bacteria when the dentin was treated with methylene blue and irradiated either with a laser diode or LED. These results corroborate those by Zanin et al.,[9] who evaluated the antimicrobial effect of toluidine blue (TBO) combined with HeNe and LED on biofilm-organized SM. In their study, a 99% reduction in microorganisms was achieved with combined HeNe laser and LED. Similarly, Paulino et al.[22] stated that any source of light with appropriate spectral characteristic could be used in PDT, such as tungsten or halogen bulbs, laser or LED.

This study was based on the method by Lima et al.,[17] which evaluated two energy densities and demonstrated that 94 J/cm2 was the most efficient at significantly reducing bacterial count. They evaluated two energy levels (47 and 94 J/cm2) and found a significant reduction in the bacterial count for SM (3.08 and 4.16, respectively), whilst for LC counts, 3.24 and 4.66, respectively. The control, which was treated with 94 J/cm2, was also effective in eliminating all oral bacteria studied. Similarly, Baptista et al.[1] reported an in vivo study, in which they created dental carious lesions in an animal model and evaluated the reduction in microaerophilic bacterial count using PDT combined with methylene blue at 100 μM and red LED (λ = 640 ± 30 nm), at 240 mW and 86 J/cm2 for 3 min.

It is likely that the statistical similarity between the LED and LASER groups when combined with methylene blue may have been due to the energy level used, which was the same for both (approximately 94 J/cm2). In order to achieve that level, 88 s of laser diode and 120 of LED were used, since the devices are different in terms of tip size and power. Such values are important, since the use of laser diode reduces the amount of bacteria effectively with reduction of the clinical time needed for bacterial inactivation. Nevertheless, the cost of laser diode devices is higher than that of LED, which would make the latter more popular.

This study also showed that when light was applied without a photosensitizer (groups SCLED and SCLASER), bacterial reduction was significantly lower than in the groups for which both light and photosensitizer were combined (groups CCLED and CCLASER). This occurred because oral bacteria generally do not absorb visible light at a certain wavelength range as observed by Zanin et al.[9]

Other photosensitizers have been used in research, such as erythrosine,[11,23,29] TBO[9,16,18,29] and methylene blue.[19,29,30] The photosensitizer methylene blue belongs to the phenothiazine family, for which the light absorption range oscillates between 610 and 670 nm.[20] Longo and Azevedo[31] also demonstrated that PDT combined with methylene blue using laser significantly decreased bacterial load in samples of carious dentin. According to Rolim et al.[29] the use of methylene blue promotes the formation of oxygen singlet, which is the reactive species responsible for bacterial death, at a rate 1.3 times higher than TBO.

In this study, fragments of dentin were irradiated directly with the light source (LED). Further in vivo studies are needed, since cariogenic oral bacteria are present in cavities of different depths. Zanin et al.[10] have reported that the bacteria present in tooth decay may be less susceptible to PDT due to the limited penetration of the photosensitizing agent or even the difficulty of light propagation through dentin. Teixeira et al.[16] reported that the higher thickness of the cariogenic biofilm in situ may have been responsible for reduced effectiveness of PDT. Guglielmi Cde et al.[19] however, obtained positive results in an in vivo study in deep caries. Similarly to the present study, most in vitro investigations evaluate caries-related bacteria isolatedly that is, not growing together within the biofilm. It is known that in a natural oral ecosystem, SM, LC and other bacteria can interact in such a way as to influence each other's metabolism.[32] It seems that biofilm-grown bacteria are less susceptible to antimicrobial agents than their planktonic counterparts.[33] Therefore, in vitro results must be interpreted with caution. It is paramount that results obtained from in vitro studies are confirmed clinically and hence that this therapy can become an alternative to conventional treatment of carious lesions.

CONCLUSION

Regardless of the light source used, either LED or LASER, PDT was effective in reducing SM and LC in dentin.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Baptista A, Kato IT, Prates RA, Suzuki LC, Raele MP, Freitas AZ, et al. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy as a strategy to arrest enamel demineralization: A short-term study on incipient caries in a rat model. Photochem Photobiol. 2012;88:584–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2011.01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson BC, Patterson MS. The physics, biophysics and technology of photodynamic therapy. Phys Med Biol. 2008;53:R61–109. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/9/R01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biel MA. Photodynamic therapy in head and neck cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2002;4:87–96. doi: 10.1007/s11912-002-0053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Plaetzer K, Krammer B, Berlanda J, Berr F, Kiesslich T. Photophysics and photochemistry of photodynamic therapy: Fundamental aspects. Lasers Med Sci. 2009;24:259–68. doi: 10.1007/s10103-008-0539-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamblin MR, Hasan T. Photodynamic therapy: A new antimicrobial approach to infectious disease? Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2004;3:436–50. doi: 10.1039/b311900a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kubler AC. Photodynamic therapy. Med Laser Appl. 2005;20:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konopka K, Goslinski T. Photodynamic therapy in dentistry. J Dent Res. 2007;86:694–707. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Komerik N, MacRobert AJ. Photodynamic therapy as an alternative antimicrobial modality for oral infections. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2006;25:487–504. doi: 10.1615/jenvironpatholtoxicoloncol.v25.i1-2.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zanin IC, Gonçalves RB, Junior AB, Hope CK, Pratten J. Susceptibility of Streptococcus mutans biofilms to photodynamic therapy: An in vitro study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:324–30. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zanin IC, Lobo MM, Rodrigues LK, Pimenta LA, Höfling JF, Gonçalves RB. Photosensitization of in vitro biofilms by toluidine blue O combined with a light-emitting diode. Eur J Oral Sci. 2006;114:64–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2006.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wood S, Metcalf D, Devine D, Robinson C. Erythrosine is a potential photosensitizer for the photodynamic therapy of oral plaque biofilms. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:680–4. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Oliveira BP, Aguiar CM, Camara AC. Photodynamic therapy in combating the causative microorganisms from endodontic infections. Eur J Dent. 2014;8:424–30. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.137662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yildirim C, Karaarslan ES, Ozsevik S, Zer Y, Sari T, Usumez A. Antimicrobial efficiency of photodynamic therapy with different irradiation durations. Eur J Dent. 2013;7:469–73. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.120677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagata JY, Hioka N, Kimura E, Batistela VR, Terada RS, Graciano AX, et al. Antibacterial photodynamic therapy for dental caries: Evaluation of the photosensitizers used and light source properties. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2012;9:122–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mang TS, Tayal DP, Baier R. Photodynamic therapy as an alternative treatment for disinfection of bacteria in oral biofilms. Lasers Surg Med. 2012;44:588–96. doi: 10.1002/lsm.22050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teixeira AH, Pereira ES, Rodrigues LK, Saxena D, Duarte S, Zanin IC. Effect of photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy on in vitro and in situ biofilms. Caries Res. 2012;46:549–54. doi: 10.1159/000341190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lima JP, Sampaio de Melo MA, Borges FM, Teixeira AH, Steiner-Oliveira C, Nobre Dos Santos M, et al. Evaluation of the antimicrobial effect of photodynamic antimicrobial therapy in an in situ model of dentine caries. Eur J Oral Sci. 2009;117:568–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2009.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Melo MA, Rolim JP, Zanin IC, Barros EB, da-Costa EF, Rodrigues LK. Characterization of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy-treated Streptococci mutans: An atomic force microscopy study. Photomed Laser Surg. 2013;31:105–9. doi: 10.1089/pho.2012.3377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guglielmi Cde A, Simionato MR, Ramalho KM, Imparato JC, Pinheiro SL, Luz MA. Clinical use of photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy for the treatment of deep carious lesions. J Biomed Opt. 2011;16:088003. doi: 10.1117/1.3611009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dobson J, Wilson M. Sensitization of oral bacteria in biofilms to killing by light from a low-power laser. Arch Oral Biol. 1992;37:883–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(92)90058-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okamoto H, Iwase T, Morioka T. Dye-mediated bactericidal effect of He-Ne laser irradiation on oral microorganisms. Lasers Surg Med. 1992;12:450–8. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1900120415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paulino TP, Magalhães PP, Thedei G, Jr, Tedesco AC, Ciancaglini P. Use of visible light-based photodynamic therapy to bacterial photoinactivation. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2005;33:46–9. doi: 10.1002/bmb.2005.494033010424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee YH, Park HW, Lee JH, Seo HW, Lee SY. The photodynamic therapy on Streptococcus mutans biofilms using erythrosine and dental halogen curing unit. Int J Oral Sci. 2012;4:196–201. doi: 10.1038/ijos.2012.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Araújo NC, Fontana CR, Bagnato VS, Gerbi ME. Photodynamic antimicrobial therapy of curcumin in biofilms and carious dentine. Lasers Med Sci. 2014;29:629–35. doi: 10.1007/s10103-013-1369-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vahabi S, Fekrazad R, Ayremlou S, Taheri S, Zangeneh N. The effect of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy with radachlorin and toluidine blue on Streptococcus mutans: An in vitro study. J Dent (Tehran) 2011;8:48–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nogueira AC, Graciano AX, Nagata JY, Fujimaki M, Terada RS, Bento AC, et al. Photosensitizer and light diffusion through dentin in photodynamic therapy. J Biomed Opt. 2013;18:55004. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.18.5.055004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gursoy H, Ozcakir-Tomruk C, Tanalp J, Yilmaz S. Photodynamic therapy in dentistry: A literature review. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17:1113–25. doi: 10.1007/s00784-012-0845-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pereira CA, Costa AC, Carreira CM, Junqueira JC, Jorge AO. Photodynamic inactivation of Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguinis biofilms in vitro. Lasers Med Sci. 2013;28:859–64. doi: 10.1007/s10103-012-1175-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rolim JP, de-Melo MA, Guedes SF, Albuquerque-Filho FB, de Souza JR, Nogueira NA, et al. The antimicrobial activity of photodynamic therapy against Streptococcus mutans using different photosensitizers. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2012;106:40–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcez AS, Núñez SC, Azambuja N, Jr, Fregnani ER, Rodriguez HM, Hamblin MR, et al. Effects of photodynamic therapy on Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial biofilms by bioluminescence imaging and scanning electron microscopic analysis. Photomed Laser Surg. 2013;31:519–25. doi: 10.1089/pho.2012.3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Longo JP, Azevedo RB. Effect of photodynamic therapy mediated by methylene blue in cariogenic bacteria. J Dent Clin Res. 2010;6:249–57. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowden GH, Hamilton IR. Competition between Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus casei in mixed continuous culture. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1989;4:57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1989.tb00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson M. Susceptibility of oral bacterial biofilms to antimicrobial agents. J Med Microbiol. 1996;44:79–87. doi: 10.1099/00222615-44-2-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]