Abstract

Background

Bile duct injury (BDI) after cholecystectomy is a serious complication. In a small subset of patients with BDI, failure of surgical or non-surgical management might lead to acute or chronic liver failure. The aim of this study was to review the indications and outcome of liver transplantation (LT) for BDI after open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Methods

Patients with BDI after cholecystectomy who were on the waiting list for LT between January 1987 and December 2010 were identified from LT centres in Spain. A standardized questionnaire was sent to each unit for extraction of data on diagnosis, previous treatments, indication and outcome of LT for BDI.

Results

Some 27 patients with BDI after cholecystectomy in whom surgical and non-surgical management for BDI failed were scheduled for LT over the 24-year interval. Emergency LT for acute liver failure was indicated in seven patients, all after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Two patients died while on the waiting list and only one patient survived more than 30 days after LT. Elective LT for secondary biliary cirrhosis after a failed hepaticojejunostomy was performed in 13 patients after open and seven after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. One patient from the elective transplantation group died within 30 days of LT. The estimated 5-year overall survival rate was 68 per cent.

Conclusion

Emergency LT for acute liver failure was more common in patients with BDI after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and associated with a poor outcome.

Introduction

The incidence of bile duct injury (BDI) during open cholecystectomy is between 0·1 and 0·3 per cent1. With the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the incidence rose to 1–2 per cent before stabilizing at 0·3–0·6 per cent2–4. BDI is a severe and potentially life-threatening complication of cholecystectomy. Liver transplantation (LT) is the final treatment option for patients who develop acute liver failure or secondary biliary cirrhosis resulting in chronic liver failure.

Most studies on LT for BDI after cholecystectomy have reported on a small number of patients. The largest study5 included only 13 patients. Although these publications provide important insights, controversy still exists regarding the indications for LT in patients with acute liver failure. In addition, no study has compared LT for BDI after open versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This study aimed to review indications and outcome of LT for BDI after open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy in Spain.

Methods

This was a retrospective multicentre study. In June 2011, all 24 LT units in Spain were invited to participate in a nationwide study on LT for BDI after cholecystectomy. Units that agreed to participate were asked to identify all patients who were on the waiting list or underwent LT for BDI after open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy between January 1987 (the year of the first LT in Spain for BDI after cholecystectomy) and December 2010 from their local database. A questionnaire was sent to each unit for extraction of data in a standardized format (Table S1, supporting information). Data extraction was done by a surgeon from each unit and data from the participating units were combined in a single database for the purpose of this study. The study was approved by the ethics committees of all participating hospitals.

Patient demographics, location of the biliary injury, associated vascular injury, surgical and non-surgical treatments, indication for LT, and perioperative morbidity and mortality (including patients on the waiting list and in the 2 months after LT) were analysed and compared between patients with BDI after open versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The Bismuth–Strasberg classification6,7 was used to locate the injuries. Vascular injuries were evaluated by Doppler ultrasonography, computed tomography-angiography and/or arteriography before LT when clinically indicated and in all patients during LT. Emergency LT was defined as transplantation in patients who were registered on the high-urgency list (code zero) to be the first on the list for LT in Spain. These patients were diagnosed with acute liver failure according to the criteria of King's College London8.

An electronic search was undertaken using the PubMed database from January 1990 to December 2012. The search used the following combinations of terms: liver transplantation AND bile duct injuries, liver transplantation AND open cholecystectomy, liver transplantation AND laparoscopic cholecystectomy, liver transplantation AND acute liver failure AND laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Further potential references were sought by review of the bibliographies of selected articles. Studies were excluded if they did not report on the surgical approach (open versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy), identification of vascular injuries, indication for LT (emergency versus elective) or when data on mortality were missing.

Statistical analysis

Comparison of categorical variables between open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed with the χ2 test and Fisher's exact test. Differences in age were assessed using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test. P < 0·050 was considered statistically significant. Actuarial survival after LT was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. The date of last follow-up was 31 December 2010. Statistical analysis was done with SPSS® version 17.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

All 24 LT units in Spain agreed to participate in the study. Data from 27 patients who were scheduled for LT were entered into the database (Table 1). Two patients with acute liver failure died while on the waiting list. Eleven LTs (7 after open and 4 after laparoscopic cholecystectomy) were performed between 1987 and 1998, and 14 (6 after open and 8 after laparoscopic cholecystectomy) from 1999 to 2010. Open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy was undertaken in all patients for biliary lithiasis. BDI was more severe and vascular injuries more prevalent after laparoscopic cholecystectomy (Table 2). In eight patients, initial treatment of BDI took place in one of the LT units and in 19 patients a surgical repair was attempted (one or more times) at the hospital of origin, which was not a reference centre.

Table 1.

Characteristics, treatment and outcome of patients with bile duct injury after laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy

| All patients (n = 27) | Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (n = 14) | Open cholecystectomy (n = 13) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 57 (35–65) | 48 (35–65) | 58 (42–63) |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 10 : 17 | 6 : 8 | 4 : 9 |

| Diagnosis of BDI | |||

| Intraoperative | 15 | 8 | 7 |

| Postoperative | 12 | 6 | 6 |

| Bismuth–Strasberg classification of biliary injury | |||

| E2 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| E3 | 11 | 3 | 8 |

| E4 | 12 | 10 | 2 |

| Vascular injury | |||

| RHA | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| CHA | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| CHA + PV | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Treatment of BDI | |||

| Surgical† | 24 | 13 | 11 |

| Conservative‡ | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| No. of interventions before LT | |||

| Surgical | 2 (1–5) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–5) |

| Radiological and/or endoscopic | 17 (2–6) | 7 (2–6) | 10 (2–5) |

| Time from BDI to LT (months)* | 36 (0·02–276) | 21 (0·02–232) | 60 (24–276) |

Values are median (range). Bismuth–Strasberg classification: E2, stricture less than 2 cm from confluence and less than 2 cm of common hepatic duct present; E3, no common hepatic duct but confluence patent, and right and left systems communicating; E4, confluence strictured and the two systems isolated.

Total hepatectomy (1 patient), Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy (24) and/or hepatic resection (6).

Radiological and/or endoscopic procedures. BDI, bile duct injury; RHA, right hepatic artery; CHA common hepatic artery; PV, portal vein; LT, liver transplantation.

Table 2.

Liver transplantation for bile duct injury after laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy

| Present study (n = 27) | Studies from literature review (n = 38) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDI after laparoscopic cholecystectomy (n =14) | BDI after open cholecystectomy (n = 13) | P§ | BDI after laparoscopic cholecystectomy (n = 22) | BDI after open cholecystectomy (n = 16) | P§ | |

| Classification of biliary injury | E2: 1 | E2: 3 | 0·014 | n.a. | n.a. | – |

| E3: 3 | E3: 8 | |||||

| E4: 10 | E4: 2 | |||||

| Associated vascular injury | 7* | 0 | 0·006 | 14 | 3 | 0·007 |

| Indication for LT | 0·006 | 0·014 | ||||

| Acute liver failure | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | ||

| Secondary biliary cirrhosis | 7 | 13 | 15 | 16 | ||

| Death | 6† | 1 | 0·048 | 4‡ | 3 | 0·641 |

Of seven patients with associated vascular injury, five were transplanted for acute liver failure and two for secondary biliary cirrhosis.

All with acute liver failure; two patients died while on the waiting list and four within 30 days after liver transplantation (LT).

All with acute liver failure; three patients died while on the waiting list and one died 24 days after LT. BDI, bile duct injury; n.a., not available.

Fisher's exact test.

Liver transplantation

The median time between cholecystectomy and inclusion on the waiting list for LT was 36 months (range 16 h to 276 months). Emergency LT was indicated in seven patients for acute liver failure after laparoscopic cholecystectomy (Table 2). Two patients died while awaiting LT; one was anhepatic after hepatectomy for massive liver necrosis owing to occlusion of both the common hepatic artery and portal vein, and the other because of multiple organ failure secondary to sepsis related to biliary injury. In all seven patients one or more attempts to repair the BDI had been made in the referring hospital.

Elective LT was indicated for secondary biliary cirrhosis in 20 patients (13 after open and 7 after laparoscopic cholecystectomy) (Table 2). Secondary biliary cirrhosis developed owing to stenosis of the bilioenteric anastomosis. Cirrhosis was confirmed on a liver biopsy by histopathology. Some 13 patients had Child–Pugh grade B cirrhosis and 7 Child–Pugh grade C cirrhosis. Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) criteria were used from 2006 (8 patients).

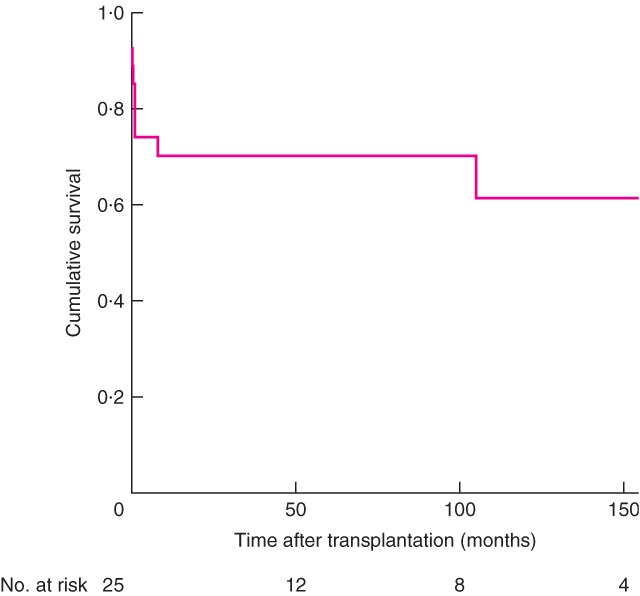

Five patients died within 30 days after LT: 4 patients after LT for acute liver failure and one after transplantation for secondary biliary cirrhosis (P < 0·001). Median follow-up was 98 (range 7–288) months. The estimated overall 5-year survival rate was 68 per cent (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Actuarial survival of patients after liver transplantation for bile duct injury

Review of the literature

The literature search identified 25 publications on LT for BDI. Thirteen studies were excluded: five because they did not report on the predefined variables, seven that reported on the same patients in several papers, and one in which BDI was not caused by cholecystectomy. Some 38 patients were included: 16 after open cholecystectomy and 22 after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Table 3 shows the prevalence of vascular injuries, indications for LT and mortality9–20.

Table 3.

Overview of published studies on liver transplantation for bile duct injury after cholecystectomy

| Reference | Year | No. of patients | Open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy | No. with vascular injury | Interval between BDI and LT (months) | Indication for LT | Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacha et al.9 | 1994 | 1 | Laparoscopic | 1 | 3 | ALF | 0 |

| Robertson et al.10 | 1998 | 1 | Laparoscopic | 1 | 20 | SBC | 0 |

| Buell et al.11 | 2002 | 2 | Laparoscopic | 1 | n.a. | ALF | 1 patient died awaiting LT |

| Nordin et al.12 | 2002 | 4 | Laparoscopic | 1 | 8, 72, 72, 36 | SBC | 0 |

| Schmidt et al.13 | 2004 | 2 | Laparoscopic | 2 | 12, 36 | SBC | 0 |

| Frilling et al.14 | 2004 | 1 | Laparoscopic | 1 | n.a. | ALF | Patient died awaiting LT |

| Thomson et al.15 | 2007 | 1 | Laparoscopic | 1 | n.a. | ALF | Patient died awaiting LT |

| Zaydfudim et al.16 | 2009 | 1 | Laparoscopic | 1 | 20 h; patient anhepatic until LT | ALF | 0 |

| Yan et al.17 | 2011 | 1 | Laparoscopic | 1 | 24 | SBC | 0 |

| Ardiles et al.18 | 2011 | 6 | Laparoscopic | 4 | 113, 157, 57, 67, 71, 75 | ALF 1 SBC 5 | Patient with ALF died 24 days after LT |

| Lubikowski et al.19 | 2012 | 2 | Laparoscopic | 0 | 132, 36 | SBC | 0 |

| Öncel et al.20 | 2006 | 1 | Open | 0 | 84 | SBC | 0 |

| Thomson et al.15 | 2007 | 2 | Open | 0 | 245, 237 | SBC | 1 patient died after LT |

| Ardiles et al.18 | 2011 | 10 | Open | 3 | Median 57 (range 0·7–153) | SBC | 2 patients died after LT |

| Lubikowski et al.19 | 2012 | 3 | Open | 0 | 42, 156, 168 | SBC | 0 |

BDI, bile duct injury; LT, liver transplantation; ALF, acute liver failure; SBC, secondary biliary cirrhosis; n.a., not applicable.

Discussion

BDI during cholecystectomy is still an infrequent but serious complication that can lead to high morbidity rates and even death21. It also affects quality of life22, and leads to increased costs and high rates of litigation claims23,24. The present study confirms previous findings that BDI after laparoscopic cholecystectomy tends to be more severe than that after open cholecystectomy4,11,14,17. Injuries after open cholecystectomy are usually extrahepatic and less often associated with vascular damage. In laparoscopic cholecystectomy the injury extends towards the hilum of the liver, possibly owing to thermal spread of the diathermy, resulting in larger bile duct defects and vascular damage. The observed negative impact of the laparoscopic approach could also be influenced by lack of experience of the surgeon rather than surgical approach alone. The present study does not provide information on the level of experience of the surgeons who performed the cholecystectomies.

Despite advances in the knowledge and treatment of BDI after cholecystectomy over the past 20 years, LT is the only therapeutic option for prevention of a fatal outcome after failed operative and non-operative management of BDI. The importance of early referral of patients with BDI to a tertiary centre with experienced hepatobiliary surgeons and a multidisciplinary team has been stressed previously25,26. All seven patients with acute liver failure in the present study were initially treated in non-specialized centres and referred for liver transplantation in the acute setting. The authors have no information on patients with BDI who died before being transferred to a specialized centre. Hence the incidence of severe BDI after open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy for which LT is indicated might be underestimated. Under-reporting of BDI might happen because of a fear of litigation claims. Unfamiliarity with the indication for LT or perceived poor outcomes of LT for BDI is another possible explanation.

At the same time, the number of patients with severe BDI who were managed successfully in specialized and non-specialized units in Spain is unknown, and the present study might overemphasize the burden of LT for BDI after cholecystectomy.

Associated vascular injuries increase the incidence of postoperative complications11,27. Such injury may lead to (partial) ischaemia of the liver, stricturing of the bilioenteric anastomosis, liver abscesses and, as a consequence, the need for hepatic resection. In the present study, five of seven patients with acute liver failure had associated vascular injuries. However, the clinical significance of an isolated right hepatic artery injury, the most frequent vascular lesion, is debated. Alves and colleagues28 reported that isolated right hepatic artery injury had no impact on the clinical presentation of BDI or on the difficulty or risk of failure of the biliary repair.

The indication for LT after BDI can be associated with three different clinical scenarios. The first is acute liver failure (within 24–48 h), due to massive ischaemic liver necrosis as a result of occlusion of the hepatic artery and portal vein11,18. Only four patients have been documented, including two in the present study. In all patients the sequence of events is the same: an attempt is made to control bleeding laparoscopically with multiple clips, and when this fails haemostasis is achieved with stitches in the hepatic hilum after conversion. Signs of multiple organ failure appear in the first 24–48 h after surgery and patients are sent to a reference hospital. Although death is common before a donor liver becomes available, LT offers the only chance of survival, as shown here.

Acute liver failure can also present later (after days, weeks or even months) owing to sepsis of hepatic origin related to stenosis of the Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy, with or without partial liver necrosis due to vascular (arterial) injury. The indication for LT in these patients is questionable and must be assessed carefully in each patient. Clearly, LT should be avoided in patients with generalized sepsis as well, when the patient, despite fulfilling the criteria for acute liver failure, can still be treated with restorative surgery or other interventions (abscess drainage, necrotic liver segment resections and repair of the hepaticojejunostomy). In the present analysis (including literative review), three patients with acute liver failure died while on the waiting list and seven were transplanted, with a successful outcome in three including one from the present series9,11.

Finally, secondary biliary cirrhosis owing to cholestasis caused by a stricture of the hepaticojejunostomy is the most frequent indication of LT for BDI after cholecystectomy29. The histopathological confirmation of diffuse secondary biliary cirrhosis is mandatory and the patients should be included on the waiting list based on Child–Pugh and MELD criteria. The outcome after LT in these patients is similar to that of patients transplanted for other indications30.

Collaborators

Other members of the Spanish Liver Transplantation Study Group are: J. Fabregat (University Hospital of Bellvitge, Barcelona), V. Sánchez-Turrión (University Hospital Puerta de Hierro, Madrid), A. Valdivieso (University Hospital Cruces, Bilbao), L. Vazquez (Central University Hospital of Asturias, Oviedo), L. F. Martínez-de Haro, F. Sánchez-Bueno and P. Ramírez (Virgen de la Arrixaca University Hospital, Murcia).

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Questionnaire sent to liver transplant units (Word document)

References

- 1.Roslyn JJ, Binns GS, Hughes EF, Saunders-Kirkwood K, Zinner MJ, Cates JA. Open cholecystectomy. A contemporary analysis of 42 474 patients. Ann Surg. 1993;218:129–137. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199308000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deziel DJ, Millikan KW, Economou SG, Doolas A, Ko ST, Airan MC. Complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a national survey of 4292 hospitals and an analysis of 77 704 cases. Am J Surg. 1993;165:9–14. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richardson MC, Bell G, Fullarton GM. Incidence and nature of bile duct injuries following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an audit of 5 913 cases. West of Scotland Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Audit Group. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1356–1360. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800831009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gigot J, Etienne J, Aerts R, Wibin E, Dallemagne B, Deweer F, et al. The dramatic reality of biliary tract injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. An anonymous multicenter Belgian survey of 65 patients. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:1171–1178. doi: 10.1007/s004649900563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Santibañes E, Ardiles V, Gadano A, Palavecino M, Pekolj J, Ciardullo M. Liver transplantation: the last measure in the treatment of bile duct injuries. World J Surg. 2008;32:1714–1721. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9650-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bismuth H. Postoperative strictures of the bile duct. In: Blumgart LH, editor. The Biliary Tract. V. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1982. pp. 209–218. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:101–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Grady JG, Alexander GJ, Haillar KM, Williams R. Early indicators of prognosis in fulminant hepatic failure. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:439–435. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bacha EA, Stieber AC, Galloway JR, Hunter JG. Non-biliary complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Lancet. 1994;344:896–897. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robertson AJ, Rela M, Karani J, Steger C, Benjamin IS, Heaton ND. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy injury: an unusual indication for liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 1998;11:449–451. doi: 10.1007/s001470050173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buell JF, Cronin DC, Funaki B, Koffron A, Yoshida A, Lo A, et al. Devastating and fatal complications associated with combined vascular and bile duct injuries during cholecystectomy. Arch Surg. 2002;137:703–708. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.6.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nordin A, Halme L, Mäkisalo H, Isoniemi H, Höckerstedt K. Management and outcome of major bile duct injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: from therapeutic endoscopy to liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:1036–1043. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.35557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt SC, Settmacher U, Langrehr JM, Neuhaus P. Management and outcome of patients with combined bile duct and hepatic arterial injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgery. 2004;135:613–618. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2003.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frilling A, Li J, Weber F, Fruhaüs NR, Engel J, Beckebaum S, et al. Major bile duct injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a tertiary center experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:679–685. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomson BN, Parks RW, Madhavan KK, Garden OJ. Liver resection and transplantation in the management of iatrogenic biliary injury. World J Surg. 2007;31:2363–2369. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaydfudim V, Wright JK, Pinson CW. Liver transplantation for iatrogenic porta hepatic transection. Am Surg. 2009;75:313–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan JQ, Peng CH, Shen B-Y, Zhou GW, Yan WP, Chen YJ, et al. Liver tranplantation as a treatment for complicated bile duct injury. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ardiles V, McCormack L, Quiñónez E, Goldaracena N, Mattera J, Pekoli J, et al. Experience using liver transplantation for the treatment of severe bile duct injuries over 20 years in Argentina: results from a National Survey. HBP. 2011;13:544–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00322.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lubikowski J, Chmurowicz T, Post M, Jarosz K, Bialek A, Milkiewicz P, et al. Liver transplantation as an ultimate step in the management of iatrogenic bile duct injury complicated by secondary biliary cirrhosis. Ann Transplant. 2012;17:38–44. doi: 10.12659/aot.883221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Öncel D, Özden I, Bilge O, Tekant Y, Acarli K, Alper A, et al. Bile duct injury during cholecystectomy requiring delayed liver transplant: a case report and literature review. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2006;209:355–359. doi: 10.1620/tjem.209.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmidt SC, Langrehr JM, Hintze RE, Neuhaus P. Long-term results and risk factors influencing outcome of major bile duct injuries following cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2005;92:76–82. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore DE, Feurer ID, Holzman MD, Wudel LJ, Strickland C, Gorden DL, et al. Long-term detrimental effect of bile duct injury on health-related quality of life. Arch Surg. 2004;139:476–481. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.5.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savader SJ, Lillemoe KD, Prescott CA, Winick AB, Venbrux AC, Lund GB, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy-related bile duct injuries: a health and financial disaster. Ann Surg. 1997;225:268–273. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199703000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kern KA. Malpractice litigation involving laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cost, cause and consequences. Arch Surg. 1997;132:392–397. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430280066009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Reuver PR, Rauws EA, Bruno MJ, Lameris JS, Busch OR, Van Gulick TM, et al. Survival in bile duct injury patients after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a multidisciplinary approach of gastroenterologists, radiologists, and surgeons. Surgery. 2007;142:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nuzzo G, Giuliante F, Giovannini I, Murazio M, D'Acapito F, Ardito F, et al. Advantages of multidisciplinary management of bile duct injuries occurring during cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 2008;195:763–769. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koffron A, Ferrario M, Parsons W, Nemcek A, Saker M, Abecassis M. Failed primary management of iatrogenic biliary injury: incidence and significance of concomitant hepatic arterial disruption. Surgery. 2001;130:722–728. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.116682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alves A, Farges O, Nicolet J, Watrin T, Sauvanet A, Belghiti J. Incidence and consequence of an hepatic artery injury in patients with postcholecystectomy bile duct strictures. Ann Surg. 2003;238:93–96. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000074983.39297.c5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Negi SS, Sakhuja P, Malhotra V, Chaudhary A. Factors predicting advanced hepatic fibrosis in patients with post-cholecystectomy bile duct strictures. Arch Surg. 2004;139:299–303. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Memoria del Registro Español de Trasplante Hepático 2011 http://www.sethepatico.org [accessed 1 July 2013]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Questionnaire sent to liver transplant units (Word document)