Abstract

The NINR Centers of Excellence program is a catalyst enabling institutions to develop infrastructure and administrative support for creating cross-disciplinary teams that bring multiple strategies and expertise to bear on common areas of science. Centers are increasingly collaborative with campus partners and reflect an integrated team approach to advance science and promote the development of scientists in these areas. The purpose of this paper is to present a NINR Logic Model for Center Sustainability. The components of the logic model were derived from the presentations and robust discussions at the 2013 NINR Center Directors’ meeting focused on best practices for leveraging resources and collaboration as methods to promote center sustainability. Collaboration through development and implementation of cross-disciplinary research teams is critical to accelerate the generation of new knowledge for solving fundamental health problems. Sustainability of centers as a long-term outcome beyond the initial funding can be enhanced by thoughtful planning of inputs, activities, and leveraging resources across multiple levels.

INTRODUCTION

The National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) Centers of Excellence program was developed more than 20 years ago to stimulate collaborative scientific efforts through the creation of research teams that incorporate investigators from disparate, yet synergistic, disciplines. The Centers are aligned with the strategic plan of NINR (https://www.ninr.nih.gov/sites/www.ninr.nih.gov/files/ninr-strategic-plan-2011.pdf). Center funding supports strategic areas including symptom science, self-management, wellness and the underserved, and end-of-life care. Input from each discipline composing the team is critical. Since 2006, NINR has funded five developmental (P20) and thirteen core (P30) Centers (Table 1). The Centers provide infrastructure and support for cross- disciplinary collaborations and a team approach to accelerate the science in their specialized areas, while expanding research capacity by providing training opportunities for students, post-doctoral fellows, and junior research faculty (Grady, 2009; Dunbar-Jacob et al., 2014).

Table 1.

NINR Funded Centers 2007-2013

| Center | Grant Number |

Funding Period |

Principal Investigator(s) |

Center Name | Institution | Website |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P30 | NR010676 | 2007-2013 | Moore, Shirley | Center of Excellence to Build the Science of Self-Management: A Systems Approach | Case Western Reserve University | http://fpb.case.edu/SMARTCenter/index.shtm |

| NR010677 | 2007-2013 | Bakken, Suzanne | Center for Evidence-based Practice in the Underserved (CEBP) | Columbia University | http://www.nursing.columbia.edu/ebp/index.html | |

| NR010680 | 2007-2012 | Wilkie, Diana | Center for End-of-Life Transition Research (CEoLTR) | University of Illinois at Chicago | http://www.uic.edu/nursing/CEoLTR/index.shtml | |

| NR011396 | 2009-2014 | Dorsey, Susan G. | University of Maryland Center for Pain Studies | University of Maryland Baltimore | http://ruinpain.org/ | |

| NR011400 | 2009-2014 | Heitkemper, Margaret McLean | Center for Research on Management of Sleep Disturbances | University of Washington | http://nursing.uw.edu/centers/crmsd/center-for-research-on-management-of-sleep-disturbances.html | |

| NR011403 | 2009-2014 | Grap, Mary Jo | Center of Excellence in Biobehavioral Approaches to Symptom Management | Virginia Commonwealth University | http://www.nursing.vcu.edu/research/centers/cbcr/ | |

| NR011409 | 2009-2013 | Han, Hae-Ra T. | Center of Excellence for Cardiovascular Health | Johns Hopkins University | http://www.son.jhmi.edu/faculty_research/research/centers/cardiovasular/index.html | |

| NR011907 | 2009-2013 | Daly, Barbara | Building End-of-Life Science through Positive Human Strengths and Traits (BEST) | Case Western Reserve University | http://fpb.case.edu/centers/BEST/ | |

| NR011934 | 2009-2012 | Miaskowski, Christine A. | Symptom Management Faculty Scholars Program | University of California San Francisco | http://nursing.ucsf.edu/research-center-symptom-management | |

| NR014129 | 2012-2017 | Dorsey, Susan G. Faden, Alan I. Greenspan, Joel | Center for the Genomics of Pain | University of Maryland Baltimore | Under Development | |

| NR014131 | 2012-2016 | Page, Gayle Smith, Michael T. | Center for Sleep-related Symptom Science | Johns Hopkins University | http://nursing.jhu.edu/faculty_research/research/centers/sleep/ | |

| NR014134 | 2012-2017 | Waldrop-Valverde, Drenna | The Center for Neurocognitive Studies (CNS) | Emory University | http://www.nursing.emory.edu/cns/ | |

| NR014139 | 2012-2017 | Anderson, Ruth Docherty, Sharron L. | Center for Adaptive Leadership in Symptom Science | Duke University | http://nursing.duke.edu/centers-and-institutes/adapt-center | |

| P20 | NR010671 | 2007-2013 | Inouye, Jillian | Center for Ohana Self-Management of Chronic Illnesses (COSMCI) | University of Hawaii at Manoa | |

| NR010674 | 2007-2012 | Schiffman, Rachel F. | Center for Enhancement of Self-management in Individuals and Families | University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee | http://www4.uwm.edu/smsc/index.cfm | |

| NR010679 | 2007-2012 | Moser, Debra | Center for Biobehavioral Research In Self-management of Cardiopulmonary Disease | University of Kentucky | http://www.mc.uky.edu/P20Center/ | |

| NR011404 | 2009-2014 | Pullen, Carol | Interdisciplinary Healthy Heart Center: Linking Rural Populations by Technology | University of Nebraska Medical Center | https://www.healthyheartcenternebraska.org/ | |

| NR014126 | 2012-2017 | Redeker, Nancy S. Yaggi, Henry | Yale Center for Sleep Disturbance in Acute and Chronic Conditions | Yale University | http://sleep.yale.edu/yale-center-sleep-disturbance |

The purpose of this paper is to present an NINR Logic Model for Center Sustainability. This logic model provides a theoretical framework for developing, implementing, and evaluating the short, medium, and long-term impact of the centers individually and of the NINR Centers program collectively. The NINR Logic Model for Center Sustainability and examples of how centers can or have used model components to maximize growth and sustainability are described. The information may provide guidance for other scientists who wish to develop and sustain a center or plan for the sustainability of a Center program, such as those funded by the NINR.

Logic modeling is a method for identifying the components, processes, and outcomes expected from a program. It is a way to describe a theory of action or a roadmap for how a particular program is developed; identify and define program activities; describe how the parts fit together and the relationships among the components; and most importantly, elaborate on methods of achieving the impact and outcomes (CDC, nd; Frechtling, 2007; University of Wisconsin-Extension, nd). Logic models are supported by evaluation theory including approaches from a practical participatory, values engaged, or emergent realist perspective (Frye & Hemmer, 2012; Hansen, Alkin, & Wallace, 2013). All theoretical approaches include context, activities, consequences/effects, assumptions, and external factors. Logic models incorporate all of the these aspects and when thoughtfully developed, can identify gaps or inconsistencies in one or more of the components, processes, or expected outcomes that could jeopardize the successful implementation, completion, and sustainability of a center. Logic models have been described as appropriate for home health (Bucher, 2010), for practice-based research networks (Hayes, Parchman, & Howard, 2011), and for community engagement in the Clinical and Translation Science Awards Program (Eder, Carter-Edwards, Hurd, Rumala, & Wallerstein, 2013). {Callout 1} The logic model presented in this paper was developed to emphasize the intentionality of the multi-level planning needed to leverage resources in order to achieve sustainability of a center.

METHODS

The writing team, which included representatives of the Center Directors (see Appendix 1), developed the logic model from the content provided at the 2013 Centers Directors Meeting on “Sustainability, Leveraging Resources, and Collaboration in NINR Centers”. The meeting provided a broad perspective from the presentations of invited speakers, interdisciplinary colleagues, NINR scientists and leaders, Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) representatives (http:www.ncats.nih.gov/research/cts/ctsa/ctsa.html), and Center Directors and Center Scientists. Meeting participants engaged in interactive breakout sessions that focused on specific topics germane to establishing center sustainability. The posters and abstracts presented at the meeting provided more details. Some centers provided additional materials, such as publications (Heitkemper et al., 2008; Inouye et al., 2011). The writing team reviewed each of these documents to identify categories and themes and determined that these were consistent with the main components of a logic model: inputs, outputs (activities and participation), outcomes, and impact. Assumptions and external factors, also components of a logic model, were gleaned from the documents. The writing team reviewed multiple drafts of the logic model until consensus was reached. Following this process, center directors who attended the 2013 meeting reviewed and commented on the draft.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

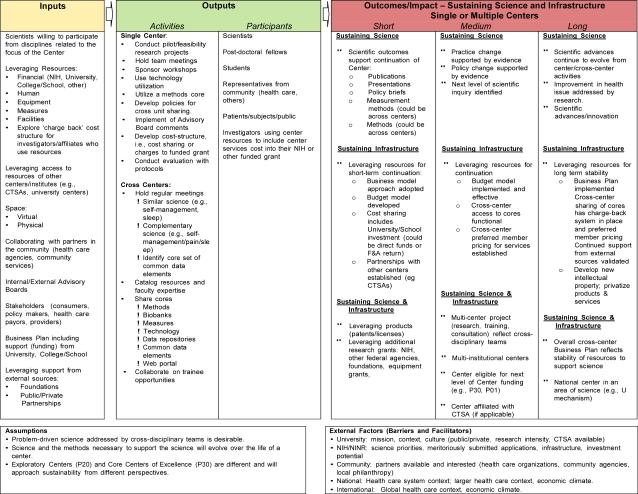

The NINR Logic Model for Center Sustainability (Figure 1) was developed to organize the many suggestions and examples identified throughout the Center Directors’ meeting. Leveraging resources and increasing cross-disciplinary and cross-center collaborations in order to achieve sustainability of infrastructure to support the science were recurrent themes in the various presentations and in the robust discussions from the breakout sessions. The NINR Logic Model for Center Sustainability is a ‘recipe’ for creating, implementing and sustaining centers, with a depiction of the many components to be considered and the relationship among the components in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of a center. Each center or potential center must identify and include the components that are unique to that center's environment. Equally important is the ability to garner the necessary resources available in the environment to support and sustain a center. The logic model incorporates strategies to break down existing barriers, both real and perceived, to foster collaborations across all levels (community to institutional to individual) in order to achieve the NIH mission of turning discovery to health and the NINR mission of promoting and improving the health of individuals, families, communities, and populations. The components of the NINR Logic Model for Center Sustainability-- assumptions, external factors, inputs, outputs, and outcomes/impact--are described in the following sections with exemplars.

Figure 1.

NINR Logic Model for Cent er Sust aina bility

Although the logic model is most clearly depicted as a linear process, the interaction among the components is often recursive. For example, a successful publication from a center project or receipt of additional funding may, in turn, spur a community partner or a foundation to provide additional support. In addition to the core group of scientists who have agreed to participate at the initiation of a center, there is a need to leverage additional and multiple resources and create new internal and external collaborations. Including partners (actual or potential) and stakeholders in the early stages of center planning and development prevents insularity and promotes responsiveness. Initiating and using a business plan that extends beyond the center funding period and considers long term budgeting for sustainability and leverages resources in addition to the initial NINR funding is critical to achieving the long term goal of sustainability. {Callout 2}

Assumptions

The writing team identified the assumptions that form the basis of the model from the themes and narratives of the Center Directors’ meeting. The scientific focus of a center is problem-driven and based on the strategically defined health issues that have been identified as priorities by NINR. Embedded is an understanding of the essential nature of centers and differences between developmental (P20) and core (P30) centers. {Callout 3} Although the elements in the logic model are intended to apply to all centers, expected sustainability outcomes from a developmental P20 center are likely to differ in quality and magnitude from those associated with a larger and more developed P30 center. At the foundation of all centers is the science, which is expected to evolve as new knowledge is generated.

Another major assumption is that team science is expected and will facilitate the development of excellent and relevant science. Team science involves the creation and support of teams composed of members with unique expertise, but who also have common scientific interests (Borner et al., 2010; Fiore, 2008; Salas, Fiore, & Letsky, 2012; Hall et al.,2010; Disis & Slattery, 2010; Hall, Vogel, Stipelman, Stokols, & Gehlert, 2012;). Using this cross-disciplinary approach is critical to answering research questions in a particular center's science focused area as well as to developing successful centers. Cross-disciplinary team members collaborate to accelerate progress toward resolving complex problems (Hall, 2012). For example, Dr. Carol Landis, Professor at University of Washington and Director of the Biobehavioral Core of the UW Center for Research on Management of Sleep Disorders (CRMSD), collaborated with colleagues in the Department of Human Centered Design and Engineering to develop a smartphone sleep diary App for use by researchers. The project was supported by pilot research funds from the School of Nursing and investigators in the CRMSD supported the collaboration, which assisted in obtaining a subsequent grant from the National Science Foundation (J. Kientz, PI) entitled “Supporting Healthy Sleep Behaviors through Ubiquitous Computing” (Carol Landis and Nathaniel Watson, co-investigators).

External factors

External factors are barriers and facilitators to the inception and sustainability of centers. Centers are embedded in and relate to the school/college, the university, and the broader community, locally and globally. In this context, a vision for a center should be in a school's/college's strategic plan and be consistent with the school/college and university mission, culture, and priorities. If the school/college has a vision for a center, the vision must be accompanied with action plans that would include a focused scientific area with a sufficient number of senior scientists (existing or recruited) who would be able to develop a center and mentor junior researchers and students. A specific commitment of school/college resources to support center and core directors beyond that covered in a potential award must be considered. There must be an alignment between the scientists’ individual programs of research and the scientific focal areas of the school/college and the center. There also needs to be a careful assessment of the collaborations/networks in the target science area that exist across the school/college, the university, and in the broader community, and what additional or new collaborations would be needed to support a center. Experience with centers and resources available in the university should be considered as external factors. If centers exist in the institution (irrespective of funding source), there may be existing guidelines on the planning, implementation, and sustainability of a new center. Barriers that may exist in an institution such as disciplinary silos that may create duplication of core services, policies for distribution for indirect cost recovery that foster competition rather than collaboration, or decentralized budget models, should be identified and solutions negotiated in the planning phase.

The issue of indirect cost recovery as a potential barrier is significant. This is especially true if multiple PIs across two or more schools collaborate on submission. Then questions regarding which school receives the indirect dollars become important and can affect the ability of MPI center grants to move forward. There are currently three centers funded with MPI teams from at least two schools. There was no consensus across the MPI teams as to how indirect cost recovery is handled. In some cases, indirect dollars follow effort and thus each school benefits. In other cases, the indirect dollars flow to the lead school handling administration of the grant activities. Thus, this issue should be carefully considered.

Major changes in funding at the university or events that affect a segment of or the entire community are likely to have consequences for a center. At a national or international level, priorities, policies, and economic conditions influence states, communities, and the universities in which they reside. Similarly, policy-relevant science generated by centers may contribute to local, regional, national, or international health status and policy. One example of external factors brought to bear is the formation of the first campus-wide Organized Research Center (ORC), the University of Maryland Center to Advance Chronic Pain Research, at the University of Maryland, Baltimore. Traditionally, ORCs have been open to membership campus-wide, but are administratively housed within a single school. When the P30 Center for the Genomics of Pain (P30NR014129) was submitted, three schools on campus and the President's office provided support and cost share dollars towards the submission of the application. Once funded, the President agreed to the formation of a new ORC in chronic pain research with two schools taking administrative lead, Dentistry and Nursing. This new ORC demonstrates the commitment of the UMB campus in this research arena, and leverages existing NIH support and new campus support to accelerate high impact science in the area that will sustain pain research on campus beyond NINR P30 funding.

Inputs

There are many components that are vital to creating a center focused on an area of science. Advancing science in the focal area of a center requires scientists from multiple disciplines. The scientists may come from existing collaborations or new collaborations may be essential to strengthen and transform knowledge in the science the center is studying and building. It is through these collaborations that new and creative directions are developed. Many of the currently funded NINR Centers include projects co-led or mentored by scientists whose primary appointment is not in a school or college of nursing. {Callout 4} This cross-fertilization of ideas, approaches, and analyses resulting from shared resources and facilities has long been the hallmark of successful research Centers. The level and depth of existing and expected collaborations may vary between P20 and P30 centers. For example, P20 Centers may focus on the early stages of development of collaborations, while P30 Centers are built on established collaborations. The foci of the currently funded NINR Centers address topics that are inherently cross-disciplinary, such as sleep disturbance, pain, self-management, and health disparities and, therefore, provide fertile ground for team science and collaboration. Many of these centers were successfully launched because collaborations were well established and, therefore, these schools and scientists were poised to respond to a call for centers in the target scientific area.

Internal advisory boards may be comprised of school and university administrative leaders and center leaders (center and core directors). This structure provides oversight since the center exists in an administrative structure with lines of authority and responsibility and that then positions the center director within the existing structure of the school/college. External advisory boards create a different oversight by providing expertise and consultation from those individuals who have breadth and depth of experiences relevant to the center or who are in positions to assist the center to meet sustainability goals. Having external board members from other centers should facilitate cross-center collaborations and boards should include members from various disciplines, as well as from the broader community.

Other collaborations with partners in the community including health care agencies or community services may be sources of leveraging resources for access to patient populations, staff who could be research associates, or meeting spaces. Other centers in the university, particularly if there is a Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA), should be evaluated and considered as a means of access to services or science specific expertise that may be needed episodically, perhaps for specific projects. Involving stakeholders early in the planning process and including stakeholders periodically through the life of the center may provide a source of future support. It is additionally important to develop a strategy early in the planning of a center to engage philanthropic organizations and foundations, as these might be alternate sources of resources and extramural funding in the future.

Leveraging access to shared or common space is also essential to the work of a center. A physical, central space, in which center scientists, pre- and post-doctoral trainees, and other interested members can meet and share ideas and engage in the work of the center, should be designated in the planning of the center so that members can be co-located. Technology should be used to enhance communication among team members and to extend the reach of the center to collaborators who are not geographically close. This would create a virtual space for a center. Therefore, the university's computer/information technology department should be included in the planning phase to ensure that the necessary IT infrastructure is available to support the work of the center and determine whether there is a separate cost for the support. For example, web based technology can be use for webinars and meetings among center investigators within the university, especially when there may be some physical distance between schools and departments. This technology can also be used to partner with other centers. For example, four centers are using web-technology to share “work in progress” sessions around their shared interests.

Outputs

The ‘work’ of the center occurs in this component. The activities and those who lead and participate in the activities are what will determine whether the center is able to meet the identified goals and outcomes. Centers provide the infrastructure within which the science will occur and will facilitate the synergistic collaboration between the outstanding scientists and their research teams. Collaborative team leadership is a critical factor in the success of organizational teams. Leadership enables the maintenance and growth of teams and team members; it promotes coordinated, adaptive team performance and study outcomes (Fiore, 2008). The center team leaders include, for example, Center Principal Investigator/Center Directors, Executive Committee members, Core Directors and Pilot Project Directors. Center leaders not only promote task performance, but they also foster PIs engagement in educational, scientific, and other types of learning opportunities for center members and others in the environment. The organization of a center and the activities needed for that center may vary by the focus of the center and whether the center is a P20 or a P30. A P20 center may have only one core in addition to the administrative core, whereas a P30 center may have additional cores focused on specific aspects of the center, for example, a core focused on measurement or intervention development.

To promote team learning, center leaders explain the rationale for decisions, help members gain self-efficacy, serve as models for teamwork, create a supportive climate for teamwork, and provide task feedback. The authors recommend that team leaders within NINR Centers, and through the center's leadership (center director and core directors), understand that they have complementary responsibilities in supporting task work and team development. On-going monitoring of individual projects and cores includes recruitment challenges, human subjects review progress, changes in methods/protocol and personnel, supplement grant opportunities, and budget reports. Assignment of a mentor from the executive team for each of the projects may enhance team learning. Laying the groundwork for effective leadership and teamwork during the center's NIH funding period may lead to greater likelihood of sustainability through commitment to the common scientific area. Involving students at all levels, post-doctoral fellows, community members at large who might be patients or subjects, and other center core/service ‘users’ provides scientists and emerging scientists with the skills and abilities that will be needed in the future. {Callout 5}

These activities and participants may focus on one center; however, there is the possibility of cross center activities when the common, unique but complementary expertise of scientists and the potential for sharing cores and other resources has been planned as one of the center inputs. If there is cross-center collaboration, the leadership (center and core directors) of both centers must be willing to share, engage, and invest if the collaboration is to be successful.

Outcomes/Impact

The majority of the work of a center leads to outcomes that are expected to have an impact across multiple sectors and over time. The logic model accounts for short, medium, and long-term outcomes and identifies outcomes that are expected to sustain the scientific focus of the center, as well as the infrastructure, to support continued development as the science evolves. Short-term scientific outcomes, those that could be expected by the end of the funding, include traditional products of dissemination (e.g., manuscripts, scientific meeting presentations, new grants). In order for a center to be sustainable over a longer time, there must be a vision for the science to advance beyond the initial focus of the center. The evolution of the science including aspects of design, populations, measurement, and analysis is expected.

Short-term outcomes for sustaining infrastructure include the resources to keep the activities of the center functioning in order to reach the outcomes expected in the longer term. These early outcomes may include commitments for cost sharing or revenue sharing from internal or external sources. Some short-term outcomes, such as licenses or additional research grants, serve to sustain both the science and the infrastructure. The short term outcomes can also be used to develop the evaluation plan and generate the milestones that need to be accomplished across the funding life of the center.

Short-term outcomes may be linked to only one center, but medium or longer term outcomes may depend on leveraging resources in the home institution or perhaps a neighboring institution, within a community, or across centers in one or more institutions, including those where there is a CTSA. Multi-center collaboration and planning ahead to develop a budget model and a strong business plan could be advantageous in garnering cost efficiencies.

A strategic long-term vision at the outset is essential in order for the center to continue beyond the initial grant funding period. Creating and marketing products and services has the potential to infuse additional revenue through “charge back” mechanisms, patents, licenses, and other products. Knowledge about technology transfer is critical to ensure these types of outcomes are met. Collaboration with other scientists and centers outside of ones own university, and with other clinical enterprises such as health care system-based programs, could help ensure that long-term sustainability and outcome goals are met by providing access to additional resources. Collaboration involves identifying and leveraging opportunities within the university and potentially across other NIH-funded Centers of Excellence (P30s, P50s) and CTSAs within that university or another university. The short and long-term goals of these collaborations include improved networking, enhanced access to and sharing of resources, and expanded interdisciplinary collaborations. {Callout 6} An illustration of collaborations between Centers is the work conducted through the P30 Centers at Duke University and Emory University that are focused on cognitive-affective symptoms. The Emory University Center for Neurocognitive Studies has a core focused on the bio-behavioral aspects of the science, and Duke University Center for Adaptive Leadership in Symptom Science developed the concept of how individuals with chronic illness and cognitive/affective symptoms interface with the health care system using the Adaptive Leadership Framework (http://nursing.duke.edu/centers-and-institutes/adapt-center). Concrete examples of this growing collaboration include a total of 19 shared seminars between the two schools within the first year of the awards. In addition, Emory center members have joined with the T32 directors to promote regular, overlapping research roundtables bi-weekly. These are well attended by both groups (average of 25-30 attendees) including all of the pre- and post- doctoral fellows supported by the training grant.

Another example of collaboration and partnership that can aid in the success and sustainability of a center, and have many nurses in leadership roles, are the National Institutes of Health (NIH) CTSA programs. Although the CTSA programs are substantially larger than the NINR-funded centers, there are best practices related to sustainability that can be gleaned from them. Examples from Centers of best practices that can be leveraged include: 1) joint support by other centers/cores to establish new or consolidate redundant translational cores; 2) strategic division of responsibility to support complementary resources, shared leadership and support; 3) adoption of resources created by other centers; and 4) use of a business model and the development of a charge back system for the use of center resources.

Long-term sustainability is ultimately aimed at improvement in health while continuing to advance an area of science. Leveraging resources across centers will be critical to achieve this impact. If a desired outcome is a national center in an area of science, then the infrastructure to support such a center is identified including an intranet to foster collaboration and increase center members’ awareness of resources, core facilities, measures, and expertise; core set of common data elements; a central bio-bank (to enter genomic, genome-wide association studies (GWAS), proteomic, metabolomics, microbiome and tissue sample data in a digestible format); a process that would allow for and encourage shared data across centers, as well as the extramural community; and a mechanism to support cross-Center research projects.

Thus, the NINR-funded centers provide a natural laboratory for building team science and disseminating information about ways to navigate barriers to moving the science forward, developing successful research collaborations, and identifying strategies for dissemination of the science and for long-term sustainability of both science and infrastructure.

A Recipe for Success

The NINR Logic Model for Center Sustainability provides a high level view of the many components that must be considered in order to plan a center. Each of these components requires a ground-level view that is focused on the operationalization of the inputs and outputs that must be considered. For example, in order to start-up a center, the center and core director and the operational staff (whether included in the funding or part of the school/college infrastructure) must be mobilized to procure space and equipment, adjust workloads for participating scientists, hire and train personnel, establish communication processes and informatics/technology support, form the internal and external committees/boards, and prepare to launch the first set of projects (including obtaining institutional review board approvals, providing for secure data storage and retrieval, establishing data safety and monitoring boards, if applicable).

In order to be successful, centers need to align with the school's strategic plan and, therefore, the school/college should move toward that scientific direction. Over time, successful centers establish a track record of science that is funded with new and established interdisciplinary investigative teams. Appendix 2 provides a summary of best practices that successful centers strive to achieve for sustainability, resource leveraging, and collaborative efforts. These best practices have led to many accomplishments from the funded centers. For example, substantial institutional support has been reported by many of the NINR centers including percent effort for faculty, support staff, cost sharing, space, and pilot funds. Many of the NINR centers are at CTSA funded institutions and are sharing resources to avoid duplication of effort and leveraging pilot funds to supplement existing center projects or new projects. Sustainability efforts are evident as centers are reporting additional NIH funding.

SUMMARY

It is clear that the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) Centers of Excellence Program, now supported for more than 20 years, has led to collaborative scientific efforts that are diverse across a number of focused science and thematic areas. The Centers Program has resulted in the creation of research teams that have incorporated investigators from disparate, yet synergistic, disciplines. A number of centers have had a focus on a specific science, such as symptom science, but have focused on different themes within that science. For example, there are three sleep centers, each having a different focus or perspective on sleep research. Each center was in a different stage of development and was able to provide a different perspective, yet the centers share common goals and value. The activities and strategies identified by the Center Directors formed the basis for the development of the logic model. The NINR Logic Model for Center Sustainability incorporates strategies that can be used when considering how to leverage resources to provide for the long-term sustainability of an existing center, but most importantly the components to consider when planning a center. As centers evolve and new centers emerge, other elements will be identified that will enhance and modify the logic model in the future.

Callouts.

Logic models have components and processes developed from and consistent with evaluation theory approaches including practical participatory, value-engaged, or emergent realistic perspectives. Centers must include planned inputs and activities that are aimed at leveraging resources and achieving sustainability.

Key business plan activities will help shape center sustainability. Successful centers establish a business plan from the inception that incorporates shared resources with other institutional entities to avoid duplicative services. Successful centers establish a service menu and cost of those services for investigators to include in their budgets for grant. The complexity of university business processes, seeking areas for efficiencies, for example avoiding the creation of a biostatistics core if others already exist, and providing cores or services that would be of value to others, are elements to be considered for writing a business plan that goes beyond the immediate functions of the center. The business plan should include public relations and a marketing plan.

P20 centers are to enhance of research capacity at institutions with emerging research programs. These centers are expected to lead to: improved capabilities at institutions with nascent research programs; an increased number of investigators involved in interdisciplinary research of importance to NINR; and larger scale research projects capable of competing for R21 or R01 levels of support. P30 centers are Centers of Excellence for institutions with several years of demonstrated research success and are organized around shared resources and research infrastructure. The individual projects supported by the P30 center focus on similar topics or research themes of strategic interest to NINR, while enjoying the benefits of a highly collaborative, interdisciplinary research environment. By leveraging common resources, it is expected that the individual projects will demonstrate greater productivity and will develop into independent research projects, i.e. R01 projects, more quickly than they would as separate projects without a central infrastructure.

- Centers with Cross-Disciplinary Principal Investigators

- Yale Center for Sleep Disturbance in Acute and Chronic Conditions (P20) (Nancy S. Redeker, PhD, RN, FAHA, FAAN, School of Nursing; Henry Klar Yaggi, MD, MPH, Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, School of Medicine).

- Center for Sleep-related Symptom Science Johns Hopkins University (P30) (Gayle Page, DNSc, RN, FAAN, School of Nursing; Michael T. Smith, PhD, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Science, School of Medicine). Center for Genomics of Pain, University of Maryland- Baltimore (P30) (Susan G. Dorsey, PhD, RN, FAAN, School of Nursing; Joel Greenspan, PhD, Department of Neural & Pain Sciences, School of Dentistry; Alan I Faden, MD, Department of Anesthesiology, School of Medicine).

Successful Centers establish a team science approach for collaboration within their institutions and externally across institutions.

Successful centers leverage resources through either external or internal institutional funding. Leveraging would include successful grant applications, in-kind space from the institution, public relations and communications to attract attention for the use of the center and talent, and in-kind support or cost-sharing for administrative and human resources.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health (P30NR014129 and P30NR011396 to SGD; P20NR010674 to RFS; P20NR014126 to NR and P30NR011400 to MH).

APPENDIX 1

NINR CENTER DIRECTORS (Center Directors listed in alphabetical order)

Drs. Ruth Anderson and Sharron Docherty, Duke University

Dr. Suzanne Bakken, Columbia University

*Dr. Susan G. Dorsey, University of Maryland

Drs. Susan G. Dorsey and Joel Greenspan, University of Maryland

Dr. Mary Jo Grap, Virginia Commonwealth University

*Drs. Margaret Heitkemper, School of Nursing, University of Washington (UW)

Dr. Jillian Inouye, University of Hawaii

Dr. Shirley Moore, Case Western Reserve University

Drs. Gayle Page and Michael T Smith, Johns Hopkins University

Dr. Carol Pullen, University of Nebraska

*Dr. Nancy S. Redeker, Yale University

*Dr. Rachel Schiffman, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Dr. Drenna Waldrop-Valverde, Emory University

*Center Directors who participated in the writing team.

Appendix 2

Key ingredients for Center success

Critical to leveraging resources is understanding:

The environment within the school and university;

The context, including the examination of how the university's overall mission and goal can be used to identify what resources should or could be leveraged;

How resources can be leveraged through good public relations and work with development officers in their school and university;

How to improve efficiencies. For example, avoid the creation of a biostatistics core when others already exist, e.g., CTSA or other entity;

How to leverage new talent and sustain and engage existing talent. In particular, create a supportive research environment for early-stage investigators and postdoctoral trainees;

How a registry can be used to catalog details about individual faculty skills and talents to encourage the utilization of young investigators;

How to create networking opportunities at social events that bring together investigators from across disciplines and career stages; and

How technology can be used to enhance communication among team members; design research projects; conduct data collection and subject recruitment and disseminate research findings.

Successful Centers foster and sustain personnel, resources, special expertise and skills, collaborations, core resources and mentorship. Identified strategies for sustainability include:

Articulate a sustainability plan with internal and external advisory board members;

Develop and evaluate both short and long-term goals related to sustainability;

Establish a clear research agenda to ensure that significant advances in the science can be made in a focused, parsimonious manner;

Involve key stakeholders and those who have purview over resources in all stages of planning, starting with grant submission;

Develop a marketing plan, perhaps in concert with the school's development officer;

Document lessons learned to share with future Centers and also, how and where to seek other sources of funding besides NIH;

Consider developing a strategy to engage philanthropic organizations and foundations as alternate sources of extramural funding;

Develop new intellectual property and increase revenue by creating and privatizing products (e.g., new instrument development); and

Actively collaborate both within and importantly, outside the home institution. This could include partnering with clinical enterprises.

Successful Centers Strive for Collaborations across Centers. These collaborations might include

Establish increased cross-institutional Center collaborations to enhance scientific discovery. This could be accomplished by using technology, (e.g., web-streaming seminar series, monthly data meetings and journal clubs to foster relationships, to reduce the distance barrier);

Leverage centers as areas of regional expertise and promote cooperation with other schools of nursing and with cross-disciplinary colleagues to foster team science, which is critical for sustainability;

Recognize that collaboration can either be emergent, arising from collaborative efforts already in place or planned, or deliberate and purposeful—having a balance between the two is important.

Collaboration can be enhanced by:

An intranet to foster collaboration and increase Center members’ awareness of resources, core facilities, measures, and expertise;

A core set of common data elements;

A central bio-bank (to enter genomic, genome-wide association studies (GWAS), proteomic, metabolomics, microbiome and tissue sample data in a digestible format (an acknowledged caveat is that this may be cost prohibitive);

A process that would allow for and encourage shared data across centers as well as the extramural community;

A mechanism to support cross-center research projects, which should specifically speak to how the funding would be used to develop and enhance collaborations (for example, centers might provide the initial seed money as proof of principle that could lead to additional calls and collaborative mechanisms such as multiple-investigator R01s); and

A national coordinating center in which multiple centers build partnerships.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Developing an effective evaluation plan. [October 21, 2013];Office of the Associate Director for Program Evaluation. http://www.cdc.gov/eval/resources/index.htmes.

- Borner K, Contractor N, Falk-Krzesinski H, Fiore S, Hall K, Keyton J, Spring B, Stokels D, Trochim B. A multi-level systems perspective for the science of team science. Science Translational Medicine. 2010;2(49):1–5. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucher JA. Using the logic model for planning and evaluation: Examples for new users. Home Health Care Management & Practice. 2010;22(5):325–333. [Google Scholar]

- Disis M, Slattery J. The road we must take: Multidisciplinary team science. Science Translational Medicine. 2010;2(22cm9):1–4. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar-Jacob J, McCloskey DJ, Weglicki LS, Grady PA. The contributions and challenges of NINR Centers: Perspectives of Directors. Research in Nursing and Health. 2014;37:174–181. doi: 10.1002/nur.21598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eder M, Carter-Edwards L, Hurd TC, Rumala BB, Wallerstein N. A logic model for community engagement within the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium: Can we measure what we model? Academic Medicine. 2013;88(10):1–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829b54ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore SM. Interdisciplinary as Teamwork: How the Science of Teams Can Inform Team Science. Small Group Research. 2008;39:251–277. [Google Scholar]

- Frechtling JA. Logic modeling methods in program evaluation. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Grady PA. The NINR research centers program. Nursing Outlook. 2009;57:113–115. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall K, Stokols D, Stipelman B, Vogel A, Feng A, Masimore B, Morgan G, Moser R, Marcus S, Berrigan D. Assessing the value of team science: A study comparing center- and investigator-initiated grants. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2012;42(2):157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall K, Vogel A, Stipelman B, Stokols D, Morgan G, Gehlert S. A four-phase model of transdisciplinary team-based research: goals, team processes, and strategies. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2012;2(4):415–430. doi: 10.1007/s13142-012-0167-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M, Alkin MC, Wallace TL. Depicting the logic of three evaluation theories. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2013;38:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes H, Parchman ML, Howard R. A logic model framework for evaluation and planning in a primary care practice-based research network (PBRN). Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2011;24(5):576–582. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.05.110043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitkemper M, McGrath B, Killien M, Jarrett M, Landis C, Lentz M, Woods N, Hayward K. The role of centers in fostering interdisciplinary research. Nursing Outlook. 2008;56:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inouye J, Boland M, Nigg CR, Sullivan K, Leake A, Mark D, Albright C. A Center for Self-Management of Chronic Illnesses in Diverse Groups. Hawaii Medical Journal. 2011;70:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokols D, Misra S, Moser R, Hall K, Taylor B. The ecology of team science: Understanding contextual influences on transdisciplinary collaboration. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;35(2S):S96–S115. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas E, Fiore SM, Letsky MP, editors. The science of team cognition: Cross-disciplinary perspectives. Routledge; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- University of Wisconsin-Extension [October 21, 2013];Program development and evaluation. http://www.uwex.edu/ces/pdande/evaluation/evallogicmodel.html.