Abstract

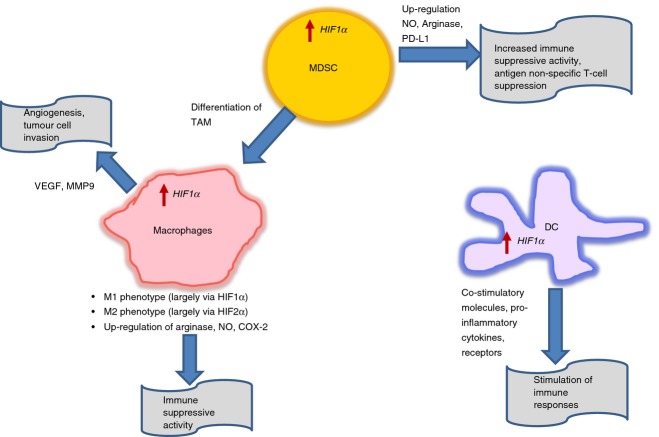

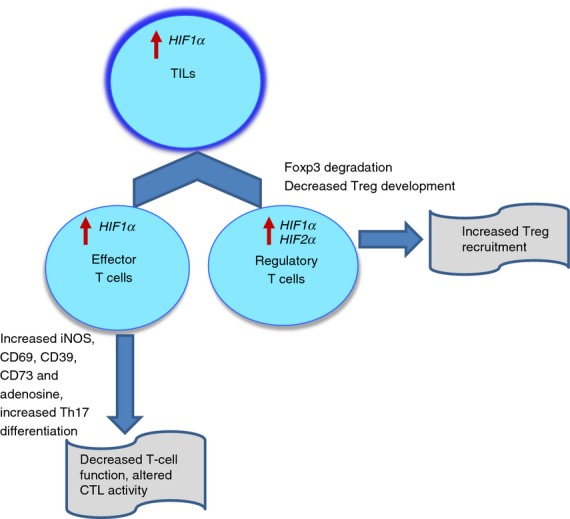

Hypoxia is one of the hallmarks of the tumour microenvironment. It is the result of insufficient blood supply to support proliferating tumour cells. In response to hypoxia, the cellular machinery uses mechanisms whereby the low level of oxygen is sensed and counterbalanced by changing the transcription of numerous genes. Hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF) play a critical role in the regulation of cellular responses to hypoxia. In recent years ample evidence has indicated that HIF play a prominent role in tumour immune responses. Up-regulation of HIF1α promotes immune suppressive activity of myeloid-derived suppressive cells (MDSC) and tumour-associated macrophages (TAM) and rapid differentiation of MDSC to TAM. HIF1α does not affect MDSC differentiation to dendritic cells (DC) but instead causes DC activation. HIF inhibit effector functions of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes. HIF1α inhibits regulatory T (Treg) cell development by switching the balance towards T helper type 17 cells. However, as a major part of Treg cell differentiation does not take place in the tumour site, a functionally more important role of HIF1α is in the promotion of Treg cell recruitment to the tumour site in response to chemokines. As a result, the presence of Treg cells inside tumours is increased. Hence, HIF play a largely negative role in the regulation of immune responses inside tumours. It appears that therapeutic strategies targeting HIF in the immune system could be beneficial for anti-tumour immune responses.

Keywords: hypoxia, hypoxia-inducible factor, macrophages, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, T cells

Introduction

Under physiological conditions, an adequate supply of oxygen is indispensable for the cellular metabolism in eukaryotes. A low level of oxygen, or hypoxia, has been found in many pathological conditions such as myocardial infarction, arthritis, wounds, atherosclerosis and chronic infections. It is attributed to a combination of events, including a high cell proliferation rate, which overwhelms angiogenesis and blood vessel maturation, and blood vessel leakiness.1–4 As a result, the cellular machinery evolves a mechanism whereby the low level of oxygen is sensed and thereafter counterbalanced by an adaptive transcriptional programme, which is largely mediated by hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF). Hypoxia has been known for a long time as an intricate part of the tumour microenvironment. In the process of counterbalancing hypoxic conditions, cancer cells acquire invasive and metastatic properties and become less sensitive to radiation therapy, which requires oxidation in aerobic conditions.5

The details of HIF structure and signalling are described in other reviews.6–8 Here, we will provide only a brief synopsis of the basic biology of HIF. Hypoxia-inducible factors are basic helix-loop-helix-PER-ARNT-SIM (bHLH-PAS) proteins, which form heterodimer complexes comprising an O2-sensitive α-subunit and a stable β-subunit. The α-subunit consists of HIF1α, HIF2α and HIF3α, whereas HIF1β is the only β-subunit known. To regulate the transcription of various genes, all HIF subunits bind to hypoxia-response elements that contain a conserved RCGTG core sequence.6 The activity of HIF is regulated by post-transcriptional modifications, which involve the hydroxylation of their proline and asparagine residues.7 The hydroxylation of proline residues is performed by prolyl hydroxylases PHD1, PHD2 and PHD3. The von Hippel–Lindau tumour suppressor protein binds both to hydroxylated HIF1α and to Elongin-C, which in turn recruits Elongin-B, CUL2 and RBX1 of an E3 ubiquitin ligase, so targeting HIF1α for ubiquitination and degradation by the 26S proteasome. The hydroxylation of asparagine residues is regulated by factor-inhibiting HIF to prevent the binding of p300/CBP co-activator, rendering HIF transcriptionally inactive.9 The hydroxylation and proteasomal degradation of HIFα subunits take place in normoxic conditions, whereas under hypoxic conditions the hydroxylases are no longer active, allowing HIF1α to translocate to the nucleus and bind to HIF1β in order to regulate the transcription.

Given that most solid tumours experience hypoxic conditions, HIF activation occurs in almost all types of cancer. Various xenograft tumour models have demonstrated the important role of HIF1α and HIF2α in promoting tumour progression, invasion, inflammatory cell recruitment and metastasis, so making HIF attractive therapeutic targets. HIF regulate the expression of genes involved in angiogenesis, apoptosis, proliferation, cell cycle progression, cancer stem cell self-renewal and metastasis.6 In recent years it became increasingly clear that HIF play a major role in the regulation of immune responses inside tumours. In this review we will discuss the effect of HIF on different immune cells in the tumour microenvironment.

The immune component of the tumour microenvironment is comprised of myeloid cells [tumour-associated macrophages (TAM), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), dendritic cells (DC)] and tumour infiltrating lymphoid cells (TIL). All these cells are greatly affected by the hypoxic stress in the tumour microenvironment. Hypoxia can interfere with the differentiation and function of immune cells by modulating the expression of co-stimulatory receptors and the type of cytokines produced by these cells.10

HIF and tumour-associated macrophages

Tumour-associated macrophages represent a major component of the tumour microenvironment. In recent years, accumulating evidence indicated that the main source of TAM are circulating monocytes rather than proliferating macrophages inside tumours.11,12 Monocytes differentiate in bone marrow from common myeloid progenitors followed by their release to the circulation with subsequent extravasation into tissues with subsequent differentiation into macrophages.13 Under physiological conditions, macrophages are an important component of innate immunity, specializing in defending the host against pathogens. Macrophages are also a critical component of tissue remodelling and repair. In cancer, TAM are associated with tumour progression, strengthening cancer cell survival, proliferation, invasion and metastasis.14

HIF1α, induced by tumour hypoxia, regulates many aspects of macrophage biology. HIF1α enhances the recruitment of bone-marrow-derived CD45+ myeloid cells, which include macrophages and Tie2+ monocytes.15 HIF1α induces vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and stromally derived factor 1α expression, which synergistically recruits CD45+ monocytic cells together with pericytes and endothelial progenitor cells. These monocytic cells express and secrete matrix metallopeptidase 9, which in turn induces the mobilization of VEGF from the extracellular matrix. It makes VEGF bioavailable for its receptor VEGFR2, and so may cause vascular remodelling and neovascularization in glioblastoma. Endothelin-2, a 21-amino acid vasoactive peptide, has also been shown to be a chemoattractant for macrophages at tumour sites. The expression of endothelin-2 is modulated by hypoxia in some tumours.16

In pathological conditions macrophages undergo phenotypic changes and distinct forms of activation depending on the signals. Classically activated macrophages (M1) are stimulated by T helper type 1 (Th1) cytokines (e.g. interferon-γ) and Toll-like receptor ligands (e.g. lipopolysaccharide). M1 macrophages are known to have potent antimicrobial activity, secrete reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitrogen intermediates, and stimulate adaptive immunity.13 In contrast to this, Th2 cytokines [e.g. interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-13] and other cytokines induce alternatively activated macrophages (M2) which are responsible for blocking the Th1 immune response and promoting tumour progression, wound healing and angiogenesis.17,18 Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression is regulated by HIF1α, and arginase expression is controlled by HIF2α. Both, iNOS and arginase induce immune suppression. Hence, by playing an antagonistic role, HIF1α and HIF2α maintain the NO homeostasis in macrophages.

In tumour tissues M1/M2 polarization is not as prominent and stable as in some other conditions. TAM often express a rapidly changing mixed phenotype. Apparently the tumour microenvironment plays a major role in the regulation of functional TAM polarization. Werno et al.19 have further clarified the role of HIF1α and HIF2α in macrophage polarization in tumours. They co-cultured wild-type and HIF1α-deficient macrophages with tumour spheroids. Both groups infiltrated hypoxic regions at equal rates, whereas HIF1α−/− macrophages developed more TAM markers associated with M2 phenotype than their wild-type counterparts. Additionally, HIF1α−/− macrophages were less toxic to tumour cells, indicating the importance of HIF1α in inducing M1 macrophages.

Hypoxia-inducible factors themselves can be differently regulated in the hypoxic microenvironment depending on the cytokine milieu. HIF1α is induced by Th1 cytokines, which are important for M1 macrophage polarization, while HIF2α is induced by Th2 cytokines involved in M2 macrophage polarization20 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The effect of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF) on myeloid cells. See description in the text.

Studies in mammary and lung carcinomas have shown the distinct localization of M1 and M2 macrophages in the tumour microenvironment. The majority of M2 macrophages with pro-angiogenic properties were enriched in hypoxic regions, whereas M1 macrophages were found to be localized in the normoxic area.21 As hypoxic regions dominate the tumour microenvironment, it can be suggested that the population of HIF2α-induced M2 macrophages are prevalent in solid tumours. These TAM display high levels of arginase 1, VEGF, osteopontin, matrix metallopeptidase, IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β and low levels of IL-12, ROS and MHC class II complex.14,21–23 The strong correlation of HIF2α expression with TAM was reported in bladder, brain, breast, colon, ovarian, pancreatic, prostate, renal and cervical carcinomas.24,25 However, various studies have also emphasized the role of HIF1α in tumour progression and angiogenesis by macrophages. Doedens et al.26 have shown that the targeted deletion of HIF1α in macrophages resulted in reduced breast tumour growth, although the VEGF-A expression and vascularization remained unchanged. They have also reported that the macrophage-mediated T-cell suppression was dependent on HIF1α. Chai et al.27 have demonstrated the positive correlation between high TAM infiltration and HIF1α, VEGF over-expression, and angiogenesis in urothelial carcinoma. In another study, the anti-tumour and anti-angiogenic properties of HIF2α have been described using mice with a monocyte/macrophage selective deletion of HIF1α or HIF2α in a murine melanoma model. The hypoxic TAM stimulated with granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor secreted HIF2α-driven soluble VEGF receptor (sVEGFR-1), which neutralized VEGF and so controlled its biological activities.28,29 HIF1α was specifically associated with production of VEGF. Moreover, using primary human peripheral blood monocytes, Staples et al.30 have shown that the differentiation of monocytes to macrophages in hypoxic conditions resulted in up-regulation of HIF1α mRNA, and this increase was not due to the increased mRNA stability.

The expression of HIF1α in human TAM has been reported to be positively associated with c-myc and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression.31,32 Various stimuli, which are responsible for sustained M2-like phenotype induced c-myc expression, its translocation to nucleus, and regulation of the subsets of genes involved in alternative activation of M2 macrophages. The inhibition of c-myc resulted in the blockade of genes associated with tumour progression such as HIF1α, VEGF, matrix metalloproteinase-9 and transforming growth factor-β.31 In urothelial carcinoma, high expression of COX-2 was strongly correlated with high HIF1α levels, high TAM infiltration and enhanced angiogenesis32 (Fig. 1).

HIF and dendritic cells

Dendritic cells are professional antigen-presenting cells functioning as an important link between innate and adaptive immunity. Dendritic cells are terminally differentiated myeloid cells that specialize in antigen processing and presentation. They differentiate in the bone marrow from various progenitors.33–36 Monocytes are the major precursors of DC in humans.37 In mice, DC can also differentiate from monocytes under certain conditions, although most DC in mouse lymphoid organs are not monocyte-derived.33,38

The effect of hypoxia on DC in the tumour microenvironment is not well described. Nevertheless, available reports suggest that hypoxia may favour the ability of DC to induce immune responses. Human mature DC under hypoxic conditions have been shown to up-regulate the expression of pattern recognition receptors (e.g. CD180), components of complement receptor (e.g. Toll-like receptor-1/2 and C-type lectin receptors), and immunoregulatory receptors (e.g. immunoglobulin-Fc receptors, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1, CD69 and CD141).39,40 Hypoxia combined with lipopolysaccharide led to a significant increase in the expression of co-stimulatory molecules, synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines and induction of allogeneic lymphocyte proliferation.41 This effect of hypoxia was mediated by HIF1α expression. In mice with HIF1α-deficient myeloid cells, the antigen-presenting cells expressed lower levels of MHC-II and the co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86. These antigen-presenting cells had reduced capability to induce T-cell proliferation. Moreover, increased stability of HIF1α in wild-type mice caused by prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor had resulted in induced expression of MHC and co-stimulatory molecules, and increased stimulation of T-cell proliferation.42 Dendritic cells treated with glioma tumour cell lysates under hypoxic conditions were better able to present antigens to CD8+ T cells than DC cultured under normoxic conditions.43 HIF1α has also been found to positively regulate the migratory capability of human monocyte-derived DC44,45 (Fig. 1).

HIF and myeloid-derived suppressor cells

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells are now established as a critical factor that regulates immune responses in cancer. These cells are characterized by common myeloid origin, immature state and immune suppressive activity.46 Immature myeloid cells with the same phenotype as MDSC are constantly generated in the bone marrow of healthy individuals, and differentiate into mature myeloid cells without causing detectable immunosuppression. However, in cancer, normal myeloid cell differentiation is diverted from its intrinsic pathway of terminal differentiation into macrophages, DC, or polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN), and instead favours differentiation of pathological MDSC. In tumour-bearing mice, the total population of MDSC is identified as Gr-1+ CD11b+ cells. It consists of immature myeloid cells that can be divided into three groups: the most abundant (> 70%) population of immature, pathologically activated neutrophils – polymorphonuclear MDSC (PMN-MDSC); the less abundant (> 20%) population of pathologically activated monocytes – monocytic MDSC (M-MDSC); and a small (< 5%) population of various myeloid precursors. PMN-MDSC have granulocytic-type morphology, CD11b+ Ly6Clo Ly6G+ phenotype, and suppress antigen-specific CD8+ T cells predominantly by producing arginase and ROS.47–49 M-MDSC have monocyte-like morphology, CD11b+ Ly6Chi Ly6G− phenotype, and suppress T cells predominantly by producing reactive nitrogen species, arginase and suppressive cytokines.47–49 In humans, MDSC with phenotype LIN− HLA-DR− CD33+ CD11b+ have been found in most types of cancer.50–54 These cells share features of pro-granulocytes, express CD66b or CD15 markers of granulocytes, and are defined as PMN-MDSC. Monocytic MDSC in patients with cancer are defined as CD14+ CD11b+ HLA-DRlow/neg cells. They are present in small proportions in many types of cancer, except for melanoma and prostate cancer where these cells represent the majority of MDSC.55–59

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α has been implicated in regulating the function and differentiation of MDSC in the tumour microenvironment. Corzo et al.60 have demonstrated that MDSC from spleen are primarily responsible for antigen-specific T-cell suppression mediated by ROS. In contrast, within the tumour microenvironment, MDSC with the same morphology and phenotype suppressed T-cell proliferation in an antigen non-specific manner by up-regulating NO production and arginase-I activity and down-regulating ROS production. Interestingly, exposure of splenic MDSC to hypoxia or treatment with iron-chelator desferrioxamine DFO (HIF1α stabilizer) led to antigen non-specific T-cell suppression, reproducing the effect of the tumour microenvironment. HIF1α induced by hypoxia in the tumour microenvironment, diverted the MDSC differentiation into immune suppressive TAM. MDSC lacking HIF1α did not differentiate into TAM within the tumour microenvironment, but instead acquired markers of DC (Fig. 1).

The role of HIF1α in regulating the differentiation of MDSC to macrophages was also demonstrated by Liu et al.61 The mammalian target of rapamycin/HIF1α pathway induced glycolytic metabolic reprogramming in MDSC, which is required for their differentiation to M1 phenotype, to confer the protection against tumour. SIRT-1 was found to be the main driver of this phenomenon as its deficiency led to the impairment of MDSC differentiation to TAM with M2 phenotype, in line with diminished glycolytic activity. HIF1α has also been reported to influence MDSC function by regulating PD-L1 expression, a ligand for immune checkpoint receptor PD-1.62 Tumour MDSC had a higher surface expression of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) than splenic MDSC. Hypoxia-induced PD-L1 expression on splenic MDSC. This effect was mediated by HIF1α, but not HIF2α. HIF1α was found to bind to a transcriptionally active hypoxia-response element in the PD-L1 promoter directly. However, up-regulation of PD-L1 expression was not limited to MDSC only, but was also observed in macrophages, DC and tumour cells. More importantly, blockage of PD-L1 in hypoxia decreased MDSC-mediated T-cell suppression by down-regulating IL-6 and IL-10 (Fig. 1).

HIF and tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes

Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes can be divided into two categories of cells with opposing functions: effector T cells and regulatory T (Treg) cells. Effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are known to have strong anti-tumour properties. In contrast, Treg cells (CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+) play an important role in immune suppression. These cells are able to suppress the functions of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, natural killer cells and DC. Both circulating and tumour-associated Treg cells have been reported to accumulate in patients with cancers.63–65 Hence, the balance between effector T cells and Treg cells could have prognostic significance in immunotherapeutic approaches.66,67

Hypoxia has been reported to regulate T-cell functions. Atkuri et al.68,69 have shown that in vitro culture of T cells in hypoxic conditions leads to suppression of their non-antigen-specific proliferation, primarily because of increased levels of iNOS and CD69, which are known to down-regulate T-cell responses. The constitutive activation of HIF1α negatively regulates T-cell receptor signal transduction, whereas its targeted deletion provides the functional advantage to T cells leading to higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, stronger anti-bacterial effects and better survival of septic mice, partially because of increased NF-κB activation.70,71 The deletion of 1·1 isoform of HIF1α, which represents < 30% of total HIF1α mRNA in activated T cells, had also been shown to enhance T-cell responses.72 Moreover, the cooperative induction of HIF1α and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 activity has been implicated in the altered target cell killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes.73 This hypoxia-induced resistance to cytotoxic T lymphocyte-dependent killing was mediated by a transcription factor, NANOG74 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The effect of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF) on tumour infiltrating lymphocytes. See description in the text.

One of the major mechanisms of the inhibition of anti-tumour T cells in hypoxic conditions is the accumulation of extracellular adenosine in the local tumour microenvironment. Hypoxia inhibits the activities of adenosine kinase and adenosine deaminase, while at the same time increasing the activity of 5′-nucleotidases, CD39 and CD73, resulting in enhanced conversion of ATP and ADP to adenosine.75 Hypoxia can also down-regulate the expression of equilibrative nucleoside transporters, leading to reduced adenosine uptake and accumulation of extracellular adenosine.76 The adenosine can function through A2A receptors, leading to an increase of cAMP, which is known to inhibit T-cell receptor-triggered proliferation, expansion and secretion of cytokines such as interferon-γ and tumour necrosis factor-α.77 Other mechanisms by which HIF1α controls T-cell responses involve the up-regulation of PD-L1 on tumour cells and tumour necrosis factor receptor family member CD137 on TIL.62,78,79

The role of HIF1α has also been implicated in regulating the differentiation of Treg cells. Dang et al.80 have demonstrated that HIF1α enhances the differentiation of pro-inflammatory Th17 cells through the direct transcriptional activation of RORγt (ROR: retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor), which, upon forming the tertiary complex with p300, is recruited to the IL-17 promoter to induce its expression. Interestingly, HIF1α down-regulated Treg cell development by binding Foxp3, leading to its proteasomal degradation. Mice deficient in HIF1α in CD4+ T cells lacked IL-17 production, had an increased population of Foxp3 Treg cells and were more resistant to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Hence, HIF1α regulates the balance between Treg cells and Th17 differentiation. These findings were supported clinically by a recent study in patients with mycosis fungoides, a variant of primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, where a negative correlation between HIF1α and Foxp3 expression was established.81 The role of HIF1α has also been identified in promoting the recruitment of Treg cells to the tumour microenvironment via over-expression of chemokine CCL28 by tumour cells. This promoted tumour tolerance and angiogenesis in human ovarian cancer.82 In prostate cancer, a significant association between accumulation of Treg cells and expression of HIF2α but not HIF1α in tumour cells has been found.83 Hence, depending on tumour type and specific signals received, HIF1α can play a dual role favouring the differentiation of Th17 from naive T cells, or suppressing effector T-cell function by recruiting Treg cells in the tumour microenvironment (Fig. 2).

Summary

Accumulated evidence strongly suggests that HIF (primarily HIF1α and HIF2α) play a major role in the regulation of the function of immune cells in the tumour microenvironment. In the myeloid compartment it appears that up-regulation of HIF1α promotes the MDSC–TAM axis by enhancing the immune suppressive activity of MDSC and TAM and by promoting rapid differentiation of MDSC (M-MDSC) to TAM. HIF1α also plays an important role in the the conversion of MDSC to antigen non-specific suppressor cells. This axis is critical for the maintenance of the immune suppressive environment in tumour sites. Although mechanisms of immune suppression promoted by HIF1α are reasonably well understood, the mechanisms regulating M-MDSC differentiation to TAM are less clear. More studies are needed to clarify this issue. The effect of HIF1α on DC appears to be rather different. Up-regulation of HIF1α does not affect M-MDSC differentiation to DC. Moreover, it results in the activation of DC and the promotion of their ability to stimulate T cells. On the other hand, it is known that tumour-associated DC are not functionally competent. Moreover, there is evidence of accumulation of immunosuppressive, regulatory DC. How those observations can be reconciled remains unclear. It is possible that HIF1α up-regulation under real conditions in tumour sites may affect only a small proportion of DC, and its effect is neutralized by various suppressive factors present in the tumour microenvironment.

Hypoxia-inducible factors have potent effects on TIL. Effector function of TIL is inhibited via multiple mechanisms involving increased adenosine-mediated signalling and iNOS. At the same time, HIF1α apparently inhibited Treg cell development by switching the balance towards Th17 cells. However, as a major part of Treg cell differentiation does not take place in the tumour site, a functionally more important role of HIF1α is in the promotion of Treg cell recruitment to the tumour site in response to chemokines. As a result, the presence of Treg cells inside tumours is increased.

Hence, HIF play a largely negative role in the regulation of immune responses inside tumours. It appears that therapeutic strategies targeting HIF in the immune system could be beneficial for anti-tumour immune responses.

Glossary

- DC

dendritic cells

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- IL-4

interleukin-4

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- MDSC

myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- PMN

polymorphonuclear neutrophils

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TAM

tumour-associated macrophages

- Th1

T helper type 1

- TIL

tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes

- Treg

regulatory T

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Disclosures

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Eberhard A, Kahlert S, Goede V, Hemmerlein B, Plate KH, Augustin HG. Heterogeneity of angiogenesis and blood vessel maturation in human tumors: implications for antiangiogenic tumor therapies. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1388–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamlouk S, Wielockx B. Hypoxia-inducible factors as key regulators of tumor inflammation. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:2721–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald DM, Baluk P. Significance of blood vessel leakiness in cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5381–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CT, Colgan SP. Hypoxia and gastrointestinal disease. J Mol Med (Berl) 2007;85:1295–300. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0277-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewhirst MW, Cao Y, Moeller B. Cycling hypoxia and free radicals regulate angiogenesis and radiotherapy response. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:425–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith B, Johnson RS, Simon MC. HIF1α and HIF2α: sibling rivalry in hypoxic tumour growth and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz CC, Taylor CT. Targeting the HIF pathway in inflammation and immunity. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2013;13:646–53. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YV, Semenza GL. RACK1 vs. HSP90: competition for HIF-1α degradation vs. stabilization. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:656–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.6.3981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Fu Z, Linke S, et al. The asparaginyl hydroxylase factor inhibiting HIF-1α is an essential regulator of metabolism. Cell Metab. 2010;11:364–78. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazon A, Aragones J, Morales-Kastresana A, de Landazuri MO, Melero I. Molecular pathways: hypoxia response in immune cells fighting or promoting cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1207–13. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Movahedi K, Laoui D, Gysemans C, et al. Different tumor microenvironments contain functionally distinct subsets of macrophages derived from Ly6Chigh monocytes. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5728–39. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin RA, Liao W, Sarkar A, Kim MV, Bivona MR, Liu K, Pamer EG, Li MO. The cellular and molecular origin of tumor-associated macrophages. Science. 2014;344:921–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1252510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch C, Giannoudis A, Lewis CE. Mechanisms regulating the recruitment of macrophages into hypoxic areas of tumors and other ischemic tissues. Blood. 2004;104:2224–34. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allavena P, Mantovani A. Immunology in the clinic review series; focus on cancer: tumour-associated macrophages: undisputed stars of the inflammatory tumour microenvironment. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;167:195–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04515.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du R, Lu KV, Petritsch C, et al. HIF1α induces the recruitment of bone marrow-derived vascular modulatory cells to regulate tumor angiogenesis and invasion. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:206–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw MJ, Wilson JL, Balkwill FR. Endothelin-2 is a macrophage chemoattractant: implications for macrophage distribution in tumors. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:2393–400. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200209)32:9<2393::AID-IMMU2393>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sica A, Larghi P, Mancino A, et al. Macrophage polarization in tumour progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18:349–55. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez FO, Sica A, Mantovani A, Locati M. Macrophage activation and polarization. Front Biosci. 2008;13:453–61. doi: 10.2741/2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werno C, Menrad H, Weigert A, Dehne N, Goerdt S, Schledzewski K, Brune B. Knockout of HIF-1α in tumor-associated macrophages enhances M2 polarization and attenuates their pro-angiogenic responses. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1863–72. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda N, O’Dea EL, Doedens A, et al. Differential activation and antagonistic function of HIF-α isoforms in macrophages are essential for NO homeostasis. Genes Dev. 2010;24:491–501. doi: 10.1101/gad.1881410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Movahedi K, Laoui D, Gysemans C, et al. Different tumor microenvironments contain functionally distinct subsets of macrophages derived from Ly6Chigh monocytes. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5728–39. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas SK, Gangi L, Paul S, et al. A distinct and unique transcriptional program expressed by tumor-associated macrophages (defective NF-κB and enhanced IRF-3/STAT1 activation) Blood. 2006;107:2112–22. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allavena P, Chieppa M, Bianchi G, Solinas G, Fabbri M, Laskarin G, Mantovani A. Engagement of the mannose receptor by tumoral mucins activates an immune suppressive phenotype in human tumor-associated macrophages. Clin Dev Immunol. 2010;2010:547179. doi: 10.1155/2010/547179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talks KL, Turley H, Gatter KC, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Harris AL. The expression and distribution of the hypoxia-inducible factors HIF-1α and HIF-2α in normal human tissues, cancers, and tumor-associated macrophages. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:411–21. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64554-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawanaka T, Kubo A, Ikushima H, Sano T, Takegawa Y, Nishitani H. Prognostic significance of HIF-2α expression on tumor infiltrating macrophages in patients with uterine cervical cancer undergoing radiotherapy. J Med Invest. 2008;55:78–86. doi: 10.2152/jmi.55.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doedens AL, Stockmann C, Rubinstein MP, et al. Macrophage expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α suppresses T-cell function and promotes tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7465–75. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai CY, Chen WT, Hung WC, Kang WY, Huang YC, Su YC, Yang CH. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α expression correlates with focal macrophage infiltration, angiogenesis and unfavourable prognosis in urothelial carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2008;61:658–64. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2007.050666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roda JM, Wang Y, Sumner LA, Phillips GS, Marsh CB, Eubank TD. Stabilization of HIF-2α induces sVEGFR-1 production from tumor-associated macrophages and decreases tumor growth in a murine melanoma model. J Immunol. 2012;189:3168–77. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roda JM, Sumner LA, Evans R, Phillips GS, Marsh CB, Eubank TD. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2α regulates GM-CSF-derived soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 production from macrophages and inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis. J Immunol. 2011;187:1970–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staples KJ, Sotoodehnejadnematalahi F, Pearson H, Frankenberger M, Francescut L, Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Burke B. Monocyte-derived macrophages matured under prolonged hypoxia transcriptionally up-regulate HIF-1α mRNA. Immunobiology. 2011;216:832–9. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pello OM, De Pizzol M, Mirolo M, et al. Role of c-MYC in alternative activation of human macrophages and tumor-associated macrophage biology. Blood. 2012;119:411–21. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-339911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WT, Hung WC, Kang WY, Huang YC, Su YC, Yang CH, Chai CY. Overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 in urothelial carcinoma in conjunction with tumor-associated-macrophage infiltration, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α expression, and tumor angiogenesis. APMIS. 2009;117:176–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2008.00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Nussenzweig MC. Origin and development of dendritic cells. Immunol Rev. 2010;234:45–54. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogg DK, Sibon C, Miled C, Jung S, Aucouturier P, Littman DR, Cumano A, Geissmann F. A clonogenic bone marrow progenitor specific for macrophages and dendritic cells. Science. 2006;311:83–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1117729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onai N, Obata-Onai A, Schmid MA, Ohteki T, Jarrossay D, Manz MG. Identification of clonogenic common Flt3+ M-CSFR+ plasmacytoid and conventional dendritic cell progenitors in mouse bone marrow. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1207–16. doi: 10.1038/ni1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik SH, Sathe P, Park HY, et al. Development of plasmacytoid and conventional dendritic cell subtypes from single precursor cells derived in vitro and in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1217–26. doi: 10.1038/ni1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idoyaga J, Steinman RM. SnapShot: dendritic cells. Cell. 2011;146:660. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortman K, Heath WR. The CD8+ dendritic cell subset. Immunol Rev. 2010;234:18–31. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco MC, Pierobon D, Blengio F, et al. Hypoxia modulates the gene expression profile of immunoregulatory receptors in human mature dendritic cells: identification of TREM-1 as a novel hypoxic marker in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2011;117:2625–39. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-292136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierobon D, Bosco MC, Blengio F, et al. Chronic hypoxia reprograms human immature dendritic cells by inducing a proinflammatory phenotype and TREM-1 expression. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:949–66. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jantsch J, Chakravortty D, Turza N, et al. Hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α modulate lipopolysaccharide-induced dendritic cell activation and function. J Immunol. 2008;180:4697–705. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari T, Olson J, Johnson RS, Nizet V. HIF-1α influences myeloid cell antigen presentation and response to subcutaneous OVA vaccination. J Mol Med (Berl) 2013;91:1199–205. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1052-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olin MR, Andersen BM, Litterman AJ, et al. Oxygen is a master regulator of the immunogenicity of primary human glioma cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6583–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippi I, Morena E, Aldinucci C, Carraro F, Sozzani S, Naldini A. Short-term hypoxia enhances the migratory capability of dendritic cell through HIF-1α and PI3K/Akt pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2014;229:2067–76. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler T, Reizis B, Johnson RS, Weighardt H, Forster I. Influence of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α on dendritic cell differentiation and migration. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:1226–36. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:253–68. doi: 10.1038/nri3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolcetti L, Peranzoni E, Ugel S, et al. Hierarchy of immunosuppressive strength among myeloid-derived suppressor cell subsets is determined by GM-CSF. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:22–35. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn JI, Nagaraj S, Collazo M, Gabrilovich DI. Subsets of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol. 2008;181:5791–802. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Movahedi K, Guilliams M, Van den Bossche J, Van den Bergh R, Gysemans C, Beschin A, Van Ginderachter JA. Identification of discrete tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cell subpopulations with distinct T cell-suppressive activity. Blood. 2008;111:4233–44. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-099226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greten TF, Manns MP, Korangy F. Myeloid derived suppressor cells in human diseases. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:802–7. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusmartsev S, Su Z, Heiser A, et al. Reversal of myeloid cell-mediated immunosuppression in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:8270–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Montero CM, Salem ML, Nishimura MI, Garrett-Mayer E, Cole DJ, Montero AJ. Increased circulating myeloid-derived suppressor cells correlate with clinical cancer stage, metastatic tumor burden, and doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide chemotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:49–59. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0523-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solito S, Falisi E, Diaz-Montero CM, et al. A human promyelocytic-like population is responsible for the immune suppression mediated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Blood. 2011;118:2254–65. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-325753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corzo CA, Cotter MJ, Cheng P, et al. Mechanism regulating reactive oxygen species in tumor-induced myeloid-derived suppressor cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:5693–701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuk-Pavlovic S, Bulur PA, Lin Y, Qin R, Szumlanski CL, Zhao X, Dietz AB. Immunosuppressive CD14+ HLA-DRlow/– monocytes in prostate cancer. Prostate. 2010;70:443–55. doi: 10.1002/pros.21078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoechst B, Ormandy LA, Ballmaier M, Lehner F, Kruger C, Manns MP, Greten TF, Korangy F. A new population of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma patients induces CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ T cells. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:234–43. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipazzi P, Valenti R, Huber V, et al. Identification of a new subset of myeloid suppressor cells in peripheral blood of melanoma patients with modulation by a granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulation factor-based antitumor vaccine. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2546–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandruzzato S, Solito S, Falisi E, et al. IL4Rα+ myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion in cancer patients. J Immunol. 2009;182:6562–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini P, Meckel K, Kelso M, et al. Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition augments endogenous antitumor immunity by reducing myeloid-derived suppressor cell function. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2691–702. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corzo CA, Condamine T, Lu L, et al. HIF-1α regulates function and differentiation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2439–53. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Bi Y, Shen B, et al. SIRT1 limits the function and fate of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumors by orchestrating HIF-1α-dependent glycolysis. Cancer Res. 2014;74:727–37. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noman MZ, Desantis G, Janji B, Hasmim M, Karray S, Dessen P, Bronte V, Chouaib S. PD-L1 is a novel direct target of HIF-1α, and its blockade under hypoxia enhanced MDSC-mediated T cell activation. J Exp Med. 2014;211:781–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo EY, Chu CS, Goletz TJ, et al. Regulatory CD4+ CD25+ T cells in tumors from patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer and late-stage ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4766–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo EY, Yeh H, Chu CS, Schlienger K, Carroll RG, Riley JL, Kaiser LR, June CH. Cutting edge: regulatory T cells from lung cancer patients directly inhibit autologous T cell proliferation. J Immunol. 2002;168:4272–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.9.4272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liyanage UK, Moore TT, Joo HG, et al. Prevalence of regulatory T cells is increased in peripheral blood and tumor microenvironment of patients with pancreas or breast adenocarcinoma. J Immunol. 2002;169:2756–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, et al. Histopathologic-based prognostic factors of colorectal cancers are associated with the state of the local immune reaction. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:610–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher K, Haensch W, Roefzaad C, Schlag PM. Prognostic significance of activated CD8+ T cell infiltrations within esophageal carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3932–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkuri KR, Herzenberg LA, Herzenberg LA. Culturing at atmospheric oxygen levels impacts lymphocyte function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3756–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409910102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkuri KR, Herzenberg LA, Niemi AK, Cowan T, Herzenberg LA. Importance of culturing primary lymphocytes at physiological oxygen levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4547–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611732104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann AK, Yang J, Biju MP, Joseph SK, Johnson RS, Haase VH, Freedman BD, Turka LA. Hypoxia inducible factor 1α regulates T cell receptor signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:17071–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506070102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel M, Caldwell CC, Kreth S, et al. Targeted deletion of HIF-1α gene in T cells prevents their inhibition in hypoxic inflamed tissues and improves septic mice survival. PLoS One. 2007;2:e853. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukashev D, Klebanov B, Kojima H, et al. Cutting edge: hypoxia-inducible factor 1α and its activation-inducible short isoform I.1 negatively regulate functions of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2006;177:4962–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.4962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noman MZ, Buart S, Van Pelt J, et al. The cooperative induction of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and STAT3 during hypoxia induced an impairment of tumor susceptibility to CTL-mediated cell lysis. J Immunol. 2009;182:3510–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0800854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasmim M, Noman MZ, Lauriol J, et al. Hypoxia-dependent inhibition of tumor cell susceptibility to CTL-mediated lysis involves NANOG induction in target cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:4031–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukashev D, Ohta A, Sitkovsky M. Hypoxia-dependent anti-inflammatory pathways in protection of cancerous tissues. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:273–9. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanello P, Torres A, Sanhueza F, et al. Equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 expression is downregulated by hypoxia in human umbilical vein endothelium. Circ Res. 2005;97:16–24. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000172568.49367.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitkovsky MV, Kjaergaard J, Lukashev D, Ohta A. Hypoxia-adenosinergic immunosuppression: tumor protection by T regulatory cells and cancerous tissue hypoxia. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5947–52. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsoum IB, Smallwood CA, Siemens DR, Graham CH. A mechanism of hypoxia-mediated escape from adaptive immunity in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2014;74:665–74. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazon A, Martinez-Forero I, Teijeira A, et al. The HIF-1α hypoxia response in tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes induces functional CD137 (4-1BB) for immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:608–23. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang EV, Barbi J, Yang HY, et al. Control of TH17/Treg balance by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cell. 2011;146:772–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcantara-Hernandez M, Torres-Zarate C, Perez-Montesinos G, et al. Overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α impacts FoxP3 levels in mycosis fungoides–cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: clinical implications. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:2136–45. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facciabene A, Peng X, Hagemann IS, et al. Tumour hypoxia promotes tolerance and angiogenesis via CCL28 and Treg cells. Nature. 2011;475:226–30. doi: 10.1038/nature10169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox SB, Launchbury R, Bates GJ, Han C, Shaida N, Malone PR, Harris AL, Banham AH. The number of regulatory T cells in prostate cancer is associated with the androgen receptor and hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-2α but not HIF-1α. Prostate. 2007;67:623–9. doi: 10.1002/pros.20538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]