Abstract

Immunoglobulin A is an important mucosal antibody that can neutralize mucosal pathogens by either preventing attachment to epithelia (immune exclusion) or alternatively inhibit intra-epithelial replication following transcytosis by the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR). Chlamydia trachomatis is a major human pathogen that initially targets the endocervical or urethral epithelium in women and men, respectively. As both tissues contain abundant secretory IgA (SIgA) we assessed the protection afforded by IgA targeting different chlamydial antigens expressed during the extra- and intra-epithelial stages of infection. We developed an in vitro model using polarizing cells expressing the murine pIgR together with antigen-specific mouse IgA, and an in vivo model using pIgR−/− mice. Secretory IgA targeting the extra-epithelial chlamydial antigen, the major outer membrane protein, significantly reduced infection in vitro by 24% and in vivo by 44%. Conversely, pIgR-mediated delivery of IgA targeting the intra-epithelial inclusion membrane protein A bound to the inclusion but did not reduce infection in vitro or in vivo. Similarly, intra-epithelial IgA targeting the secreted protease Chlamydia protease-like activity factor also failed to reduce infection. Together, these data suggest the importance of pIgR-mediated delivery of IgA targeting extra-epithelial, but not intra-epithelial, chlamydial antigens for protection against a genital tract infection.

Keywords: antibodies, Chlamydia, polymeric immunoglobulin receptor, vaccination

Introduction

Urogenital chlamydial infections globally affect an estimated 106 million people annually.1 Infection can cause tissue inflammation, scarring, decreased fertility and can lead to infertility. Infections are often asymptomatic (40–60% of males and 70–90% of females) facilitating continued spread throughout the community.2 In addition to the high incidence of subclinical infections in males, risk of sexual transmission is also greatest from infected male to uninfected female, occurring in approximately 40% of encounters.3 Although antibiotic intervention is widely accepted to eliminate infection, it can arrest the development of adaptive immunity – limiting the appropriate responses to subsequent infections.4 For these reasons, it is widely accepted that there is a requirement for a chlamydial vaccine.5–7

Chlamydial vaccine research is focused primarily on protecting against the chlamydial burden and immunopathology associated with infections in females, and has identified a crucial role for CD4+ T cells secreting interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α).7 There is considerably less research devoted to developing a male vaccine,6,8 despite males arguably being the reservoir of infection and susceptible to infertility.8 A vaccine eliciting IFN-γ and TNF-α secretion in response to infection may prove efficacious in females, but a similar response may be immunopathological in males.8 The presence of Chlamydia-specific CD4+ T cells in male mice is associated with greater clearance of infection,9 yet CD4+ T cells secreting large amounts of IFN-γ and TNF-α are also associated with breakdown of immune privilege in the testes leading to infertility.10 This suggests that a vaccine aimed at eliciting a cell-mediated response to defend against infection could facilitate the development of male infertility. Antibodies, however, play a non-essential but supportive role during a natural chlamydial infection7 and considerably improve protection against infection following vaccination.11 Hence, antibodies may be a safer alternative to potentially damaging CD4+ T-cell responses in the context of a male vaccine.

The role for IgA in chlamydial infections is controversial. Naive IgA−/− female mice show no significant difference to wild-type (WT) mice in their ability to resolve primary or secondary Chlamydia muridarum infections.12 However, the concentration of IgA in the human endocervix inversely correlates with Chlamydia trachomatis burden,13 and males secrete significantly more secretory IgA (SIgA) in urethral mucosal secretions during C. trachomatis infection, indicating that SIgA may play an important role in human infection and transmission.14 Passive immunization of mice with monoclonal anti-major outer membrane protein (anti-MOMP) IgA can also significantly reduce the magnitude of an infection in female mice.15,16 Similarly, protection against tissue burden conferred following immunization of male mice with MOMP was dependent on secretion of IgA.11 Hence, the protective role of IgA depends on the titre, which can be greatly enhanced with immunization and the accessibility of the target antigen.

The polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR) is an integral membrane protein responsible for mucosal transport of dimeric IgA produced locally by plasma cells in the lamina propria. The pIgR is basolaterally expressed on epithelial cells where it binds dimeric IgA around the joining chain, internalizes and traffics it to the apical surface (i.e. the lumen) where pIgR is proteolytically cleaved releasing secretory component covalently bound to IgA, termed SIgA. Secretory IgA is the dominant immunoglobulin at most mucosal surfaces and plays important roles in immune tolerance, mucosal homeostasis, commensal symbiosis and immunity. In addition to epithelial trafficking of IgA to the mucosal lumen, pIgR transcytosis of IgA can also bind and neutralize already internalized viruses.17–19

Chlamydia spp. are obligate intracellular bacteria with a biphasic lifecycle consisting of an infectious extracellular metabolically inert elementary body (EB), and an intracellular metabolically active and replicating reticulate body (RB) phase. The chlamydial EB is highly resistant to physical and environmental disruption, primarily because of highly cross-linked and disulphide-bonded membrane proteins, principally the MOMP.20 Following attachment and endocytosis of the EB by the host cell, chlamydiae escape the normal endocytic pathway and differentiate within a parasitophorous vacuole, termed the inclusion. The inclusion allows the pathogen to replicate and absorb nutrients without being subjected to/attacked by innate intracellular defences such as lysosomal fusion. Some chlamydial inclusion membrane proteins, including the inclusion membrane protein A (IncA), face the host cytoplasm and directly interact/interfere with host vesicle fusion.21 Within the inclusion, replicating RBs also produce proteases, such as chlamydial protease activity factor (CPAF), some of which are secreted into the host cell cytoplasm and interferes with host cell processes.22,23

Chlamydia spp. express a variety of IgA-accessible epitopes. Therefore, we addressed the potential of SIgA to prevent attachment to and infection of host cells by targeting an extra-epithelial chlamydial antigen presented on the surface of the EB and the ability of SIgA raised against intra-epithelial chlamydial antigens expressed during the RB phase to internalize and neutralize an already established infection. To address these questions we chose three widely studied antigens representing the EB (e.g. MOMP), inclusion membrane (e.g. IncA) and secreted chlamydial proteases (e.g. CPAF) groups. To determine the role of pIgR and antigen-specific IgA against intra- and extra-epitheilal chlamydial antigens, we developed and used an in vitro Transwell® model, and confirmed the results in vivo using pIgR-deficient mice. We demonstrate that pIgR-mediated delivery of IgA targeting extra-epithelial (MOMP), but not intracellular (IncA, CPAF) proteins, can significantly reduce chlamydial infection. These findings confirm the important role of pIgR and SIgA in chlamydial infections, and have implications for subunit chlamydial vaccines.

Materials and methods

Ethics

All experiments were performed with approval from the university animal ethics committee (UAEC) of the Queensland University of Technology (QUT), (UAEC #0800000824).

Mice

Adolescent (> 6 weeks) male C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Animal Resource Centre (Perth, Australia) and C57BL/6 pIgR−/− mice were provided by Odilia Wijburg (University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia). Mice were fed ad libitum with procedures performed under physical containment level 2 (PC2) conditions following NHMRC guidelines.

Cell lines

Chlamydia murdiarum (ATCC VR-123) and McCoy B fibroblasts (ATCC CRL-1626) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Chlamydia muridarum was propagated in McCoy B cells and purified as previously described.24 Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) high glucose (Invitrogen, Melbourne, Vic., Australia) was supplemented with 10% (volume/volume) heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 2 μg/ml gentamycin sulphate (Invitrogen), 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulphate (Sigma Aldrich, Castle Hill, NSW, Australia), and 2 mm l-glutamine (Invitrogen) was used to grow cells unless otherwise stated. The human endometrial epithelial cell line HEC-1A (ATCC: HTB-112) and human colonic epithelium C2Bbe1 (ATCC: CRL-2102) cells were purchased from the ATCC. C2Bbe1 cells had 10 μg/ml of human transferrin (Invitrogen) added to the growth medium. Human endometrial epithelial cells ECC-1 (ATCC: CRL-2923) were a gift from Charles Wira (Dartmouth Medical College, Lebanon, NH). Madin-Darby canine kidney epithelial cell subclone MDCK I (ATCC: CCL-34) were a gift from Russell Simmons (Queensland Health Scientific Services, Brisbane, Australia), and subclone MDCK II cells (ATCC: CRL-2936) were a gift from Finn-Erik Johansen (University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway). Human bronchial epithelial cells BEAS-2B (ATCC: CRL-9609) were a gift from Phillip Hansboro (University of Newcastle, Newcastle, Australia) and were grown in RPMI-1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented as for DMEM. The GK1.5 (ATCC: TIB-207) hybridoma was a gift from Graham Le Gros (Malaghan Institute of Medical Research, Wellington, New Zealand) and was maintained in supplemented RPMI-1640. Vero E6 (ATCC: CRL-1586) green African monkey kidney epithelial cells were a gift from John Aaskov (Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia) and were grown in supplemented RPMI-1640. All cells were grown in a humidified incubator at 37° and 5% CO2. Cells were periodically determined as free of Mycoplasma spp. by PCR.

Transwell culture

Epithelial cells were seeded onto 0·4-μm pore Transwell® inserts (BD Falcon, North Ryde, NSW, Australia) at 105 cells/6·5-mm insert (24-well format). Media in the apical (200 μl) and basolateral (600 μl) chambers was changed every second day. Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) was monitored daily with an EVOM electrode (Millipore, Kilsyth, Vic., Australia). TEERs were determined with the formula; TEERs (ohms.cm2) = (resistance of test (Ω) − resistance of blank insert (Ω)) × surface area of insert (cm2). Expression of zona occludens 1 (ZO-1) was determined following 5 days of growth on transwells, followed by 24 hr of C. muridarum infection. Cells were fixed with 100% methanol, blocked with 5% fetal calf serum in PBS + 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST), and then stained with primary antibodies sheep anti-MOMP and rabbit anti-ZO-1 (N-terminal) (Invitrogen) for 1 hr at room temperature. Inserts were then washed with PBS and then incubated with secondary antibodies donkey anti-sheep IgG-Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen), and goat anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen) for 1 hr at room temperature. Cells were then incubated with DAPI for 20 min and mounted with Prolong Gold (Invitrogen) overnight. Cells were then imaged using an SP5 confocal microscope (Leica, North Ryde, NSW, Australia).

Quantitative real-time PCR

BEAS-2B, C2Bbe1, ECC-1 and HEC-1A cells were grown in culture, lysed and mRNA extracted with Trizol (Invitrogen), and cDNA was synthesized with a First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Exon-spanning primers were designed from human mRNA sequences and Primer 3 software. Primers for the amplification of human pIgR (200 bp, forward: 5′-TGGCGGTCTTCCCAGCCATC -3′; reverse: 5′-GCTGGAGACGTAGCCCTCCGT-3′) and GAPDH (69 bp,forward: 5′-CCACCCATG GCAAATTCC-3′, reverse: 5′-TGGGATT-TCCATTGATGACAA-3′) were synthesized by Sigma Aldrich. Transcription of pIgR and GAPDH was quantified by PCR performed using a rotorgene thermocycler (Qiagen, Doncaster, Vic., Australia) with the conditions; 35 cycles of denaturing at 95° for 20 seconds, annealing at 60° for 20 seconds, and amplification at 72° for 20 seconds.

Recombinant protein production

Recombinant C. muridarum MOMP was a generous gift from Harlan Caldwell (Rocky Mountain Labs, Hamilton, MT) and was expressed and purified as previously described.23 Lyophilized control antigen ovalbumin (OVA) was purchased (Sigma Aldrich) and resuspended in PBS. Full-length recombinant C. muridarum IncA (NP_296774) and CPAF (NP_296627) were produced by amplifying full-length coding sequences with primers; IncA (845 bp: Forward with BamHI 5′- CGGGATCCATGACATCACCTACTCTAG -3′, Reverse with EcoRI 5′-CCGGAATTCTTAGGCGGAAGAATCAG -3′), and CPAF (1806 bp: Forward with BamHI 5′- CGGGATCCATGAAAATGAATAGGATTTTGCTACTGC -3′, Reverse with KpnI 5′- CCGGTACCTTAAAAACTTCCATCCTCTGAGAGAATAATTACAC -3′). Hot-start PCR was performed with conditions of 95° for 2 min, addition of Pfu polymerase (Promega, Alexandria, NSW, Australia), then 35 cycles of 95° for 1 min, 60° for 1 min, and 74° for 5 min. Amplicons were purified using Purelink PCR purification columns (Invitrogen) and restriction digested with BamHI/EcoRI (IncA) or BamHI/KpnI (CPAF) for 1 hr at 37°. Digested amplicons were ligated using T4 DNA Ligase (Promega) into the N’-terminal his-tag vector pRSET-A (Invitrogen) previously restriction digested with corresponding restriction enzymes. Vectors were transformed into BL21 (DE3) pLysS Escherichia coli (Invitrogen), grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 0·4 in LB broth (10 g tryptone, 10 g NaCl, 5 g Yeast extract in 1 L H2O), and then induced with 0·5 μm IPTG for 3 hr at 30°. Escherichia coli was lysed and His-tagged protein was purified using Talon affinity resin (Clontech, Clayton, Vic., Australia) as per the manufacturers’ instructions. Proteins were eluted with 150 mm imidazole (Sigma Aldrich), dialysed into PBS and stored at −80°.

Immunization schedule of mice to obtain antigen-specific IgA

Mice were immunized intranasally with 20 μg of antigen and 0·5 μg of cholera toxin on days 0, 7, 14 and 25. Mice were killed by overdose of sodium pentobarbitone on day 35 and blood was collected via cardiac puncture.

Purification of murine total IgA from sera

Sera from immunized groups (n = 10) were pooled and poorly solubilizing proteins were precipitated by slow addition of half the serum volume of saturated ammonium sulphate, bringing the final volume of ammonium sulphate to approximately 30%. The serum was incubated at 4° on a rotating wheel for 6 hr. Weakly soluble proteins were precipitated by centrifugation at 4000 g for 30 min at 4°. The supernatant was collected and half the initial volume of saturated ammonium sulphate was added to bring the final concentration to 50%. The sera were incubated on a rotating wheel overnight at 4°. Immunoglobulin was precipitated at 4000 g for 30 min at 4°. The supernatant was discarded, and the immunoglobulin was resuspended in PBS to 10 times the initial volume of sera. Immunoglobulin was pooled and depleted of IgG by passing over Protein G resin (Genscript, Piscataway, NJ) and collecting the flow-through. Immunoglobulin G-depleted ammonium sulphate-fractionated antibody was further purified with a Mouse IgA Purification Resin Kit (# MIKA-FF Kit; Affiland SA, Ans-Liege, Belgium) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, immunoglobulin was diluted in 15 ml PBS, and IgA was precipitated with 35 ml of precipitation buffer (Affiland SA) for 15 min at room temperature. Protein was allowed to rest at 4° for 30 min, and then centrifuged at 4000 g for 15 min. The supernatant was collected (containing IgG, IgD, IgE and other highly soluble proteins), and the precipitate (containing polymeric IgA and IgM) was resuspended in 10 ml of binding buffer (Affiland SA). The soluble IgA/IgM in binding buffer was run over an equilibrated mouse IgA resin bed by gravity flow, washed with PBS, and eluted using elution buffer (Affiland SA). Protein-containing fractions were pooled and concentrated using a 30 000 molecular weight (MW) cut-off centrifuge filter (Millipore). To confirm purification of IgA, eluates were separated on non-reducing/non-denaturing SDS–PAGE, and Western immunoblotting and was determined to be > 90% IgA with no detectable IgM or IgG by sandwich ELISA. A typical yield following purification was 3–4 mg of IgA per ml of pIgR−/− serum. Immunoglobulin A was stored in aliquots at −80° until required.

Transfection and evaluation of murine pIgR transfectants

C2Bbe1 cells were transfected with a vector encoding murine pIgR (mpIgR) with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and Plus Reagent (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, Lipofectamine complexed with pcDNA3.1 mpIgR (pcDNA_mpIgR) generously donated by Finn-Erik Johansen (University of Oslo, Norway) was transfected into equilibrated C2Bbe1 cells, and positive cells were selected for in DMEM supplemented with 550 μg/ml of G418 (Invitrogen). This plasmid has previously been shown to express functional mpIgR in MDCK cells.25 Transfected clones were obtained by limiting dilution for monoclonal cell populations. Clones were evaluated on their ability to bind mouse IgA by incubating them with pIgR−/− sera (which pools IgA), fixing with 100% methanol, probed with goat anti-mouse IgA-horseradish peroxidase (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL), and detecting with DAB precipitation (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Scoresby, Vic., Australia) and counterstained with Mayer’s haematoxylin (Sigma Aldrich). Clone 1 of 8 was found to bind the most IgA and was used thereafter.

Male immunization and challenge

Mice were housed for 1 week before the initial immunization and immunized on days 0, 14 and 25 via the intranasal route. Mice were anaesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg), placed on their backs, and received intranasal immunizations, in a total volume of 5 μl, 2·5 μl per nare. On days 0, 7 and 14, 20 μg of antigen and 0·5 μg of cholera toxin was administered intranasally, and on day 25 mice received a boost of 50 μg of antigen, 1 μg of cholera toxin and 10 μg of CpG (5′-TCC ATG ACG TTC CTG ACG TT-3′) (Sigma Aldrich). Mice were depleted of CD4+ cells by intraperitoneal injection of 200 μg of GK1.5 2 days before penile challenge, and received continuous depletion with intraperitoneal injection of 100 μg of GK1.5 every week until euthanasia. Mice were infected with 106 inclusion-forming units of C. muridarum (Weiss) in 5 μl via the penile urethra to ensure that 100% of mice were infected, as previously described.26 At time of killing, cardiac blood was taken for ELISA, which was performed as previously described.24 Caudal and lumbar lymph nodes and spleens were taken for flow cytometry as previously described.27 The testes, bladder and penis were collected and homogenized in sucrose phosphate glutamate (219 mm sucrose, 10 mm sodium phosphate, 5 mm l-glutamine) on the lowest speed (5000 × rpm) with a 220V generator probe (OMNI International, Kennesaw, GA) for 10 seconds, and stored at −80° until inclusion-forming units were determined by culture on McCoy cells for 24 hr and quantified by fluorescence microscopy as described elsewhere.27

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of data was performed using Graphpad Prism version 5 (Graphpad Prism, La Jolla, CA). Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests and one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc tests were performed where indicated. All mouse work was performed using five animals per group as this was determined to have > 80% statistical power. Significance was determined as *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001. Graphs with error bars represent the mean ± SEM.

Results

Purification of antigen-specific IgA

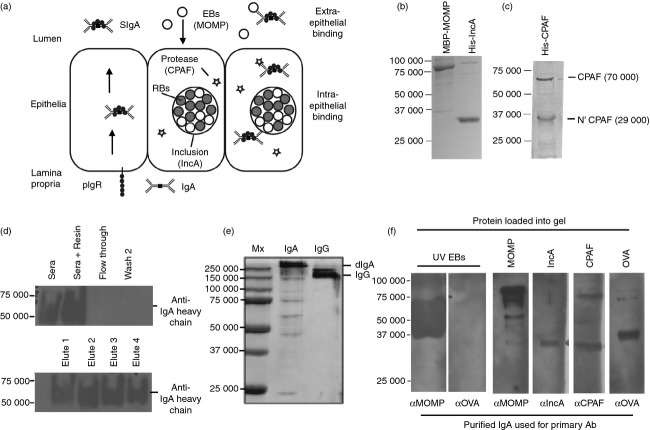

The ability of IgA targeting extra- and intra-cellular chlamydial antigens to prevent infection or to neutralize an established infection, respectively, was determined by targeting three chlamydial proteins potentially accessible to IgA binding (Fig. 1a). To obtain antigens from the extra- and intra-cellular stages of the chlamydial life cycle, recombinant MOMP, IncA and CPAF were produced and purified (Fig. 1b,c). Purified CPAF contained the full-length protein, as well as the cleaved 6×His tagged N’ terminal of CPAF, consistent with recombinant CPAF’s ability to be self-cleaved.28 Both IncA and CPAF contained 6×His tags confirmed by Western blot; and MOMP, IncA and CPAF were all recognized by sera from C. muridarum-infected female mice (not shown). To obtain a high yield of purified IgA we immunized pIgR−/− mice as IgA pools in their plasma.29 Because the proteins Jacalin or staphylococcal superantigen-like protein 7 (SSL7) bind human IgA but not mouse IgA,30 we used Affiland® mouse IgA purification resin to purify polyclonal mouse IgA from the sera of immunized mice. To ensure minimal IgG was co-purified, serum was first depleted of IgG with Protein G resin. Immunoglobulin G-depleted serum was bound to Affiland® resin and eluted and samples from various stages of purification were evaluated by Western blot for IgA (Fig. 1d). Immunoglobulin A was found to be bound to washed resin and in eluted fractions, with no detectable IgM or IgG in the elutions, as determined by sandwich ELISA (not shown). To confirm that IgA was dimeric and not monomeric, non-reduced and non-denatured IgA and IgG were run on PAGE (Fig. 1e). To confirm that purified IgA was able to bind its corresponding antigens, IgA was used to probe chlamydial antigen separated by Western blot (Fig. 1f). Together, these data demonstrate that the Affiland® mouse IgA purification resin can be used to purify polyclonal antigen-specific IgA from immunized pIgR−/− mouse sera and that purified IgA retains antigen-binding specificity.

Figure 1.

Purification of antigen-specific dimeric mouse IgA. (a) Potential chlamydial antigen targets for intra- and extra-epithelial IgA. SDS–PAGE gels of purified recombinant Chlamydia muridarum antigens major outer membrane protein (MOMP), inclusion membrane protein A (IncA) (b), and chlamydial protease-like activity factor (CPAF) (c). (d) Serum from MOMP/IncA/CPAF or ovalbumin (OVA) -immunized mice was pooled (n = 10), depleted of IgG and purified with Affiland® Mouse IgA Purification Resin. Samples were separated on SDS–PAGE, blocked and probed with anti-mouse IgA (α chain) horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies. (e) Non-reducing/non-denaturing SDS–PAGE of IgA and IgG elutions. (f) Protein antigens were separated by SDS–PAGE, and Western blotted with corresponding purified IgA. Bound IgA was detected with anti-mouse IgA (α heavy chain)-horseradish peroxidase IgG.

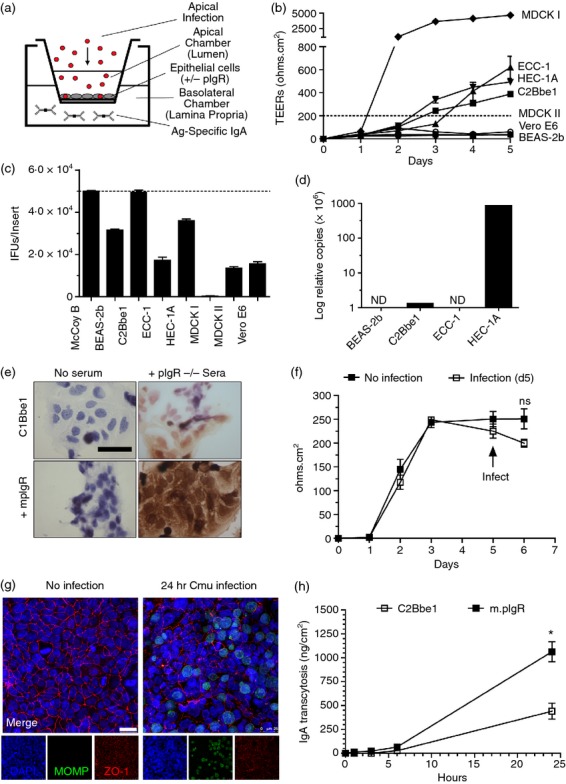

Establishment of an in vitro model to access the protection afforded from intra- and extra-cellular IgA in chlamydial infections

To determine the neutralizing potential of IgA targeting intra- and extra-epithelial chlamydial antigens, a Transwell model using polarized epithelial cells expressing mpIgR was used (Fig. 2a). As we were unable to locate a mouse cell line that constitutively expresses mpIgR and forms tight cell–cell junctions (i.e. polarizes), we screened a variety of epithelial cell lines known to polarize in a Transwell® model, determined their susceptibility to infection once polarized, and transfected them with a plasmid constitutively expressing mpIgR. The TEER of the cell lines in transwells was determined over 1 week and human HEC1A, ECC-1 and C2Bbe1 cells, as well as canine MDCK I cells, were found to strongly polarize (Fig. 2b). However, upon polarization only C2Bbe1 cells remained susceptible to chlamydial infection (Fig. 2c), consistent with other findings.31 Expression of human pIgR mRNA was also determined by quantitative RT-PCR in BEAS-2B, C2Bbe1, ECC-1 and HEC-1A cell lines with BEAS-2B and ECC-1 lacking expression, C2Bbe1 with a small amount (1·5 × 10−6 relative copies), and HEC-1A with the largest amount (9 × 10−4 relative copies; Fig. 2d). As C2Bbe1 cells strongly polarized, remained susceptible to infection, and had low expression of human pIgR, these were selected for transfection with mpIgR and used in subsequent experiments.

Figure 2.

A model to evaluate efficacy of intra- and extra-epithelial IgA against chlamydial infection. (a) Schematic showing the in vitro model used to determine intra- and extra-epithelial neutralization. (b) MDCK I-II, HEC-1A, ECC-1, C2Bbe1, Vero E6 and BEAS-2b cells were grown on Transwell® inserts and the transepithelial electrical resistance (TEERs) were recorded. (c) Susceptibility of cell lines to apical infection following 5 days of polarization on Transwell® inserts. (d) Quantitative expression of human polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR) mRNA in BEAS2b, ECC-1, C2Bbe1, and HEC-1A cells was determined by quantitative RT-PCR. (e) C2Bbe1 cells (± murine pIgR) were fixed and incubated with pIgR−/− mouse sera, and bound IgA was detected with goat anti-mouse IgA-horseradish peroxidase antibody. (f, g) C2Bbe1 cells were grown on Transwell® inserts for 5 days then apically infected with Chlamydia muridarum for 24 hr. (f) TEER of C2Bbe1 cells following 24 hr of infection. (g) Confocal microscopy demonstrating tight junction (ZO-1) expression in mock and C. muridarum-infected C2Bbe1 cells. (h) C2Bbe1 cells (± murine pIgR) were grown on Transwell® inserts for 5 days and then purified mouse IgA was basolaterally loaded. Apical samples were taken and quantified by sandwich ELISA at 1, 3, 6 and 24 hr post inoculation. Error bars represent mean ± SEM (n = 3 or n = 4). Scale = 25 μm. ND = none detected.

Following transfection with pcDNA-mpIgR, antibiotic selection, and cloning, the ability of transfected C2Bbe1 clones to bind murine IgA was determined by immunocytochemistry (Fig. 2e). In the presence of 1% pIgR−/− sera (high in IgA), C2Bbe1 cells bound a small amount of mIgA consistent with the weak binding of mouse IgA by hpIgR, but when transfected with mpIgR bound considerably more IgA.

To determine if monolayer integrity was affected by chlamydial infection, electrical resistance, passive flux and tight junction protein expression were investigated. Following 24 hr of infection TEERs were non-significantly reduced (P = 0·15) in infected cells when compared with uninfected cells (Fig. 2f). Interestingly, passive transport of FITC-dextran (4000 MW) was slightly but significantly reduced (P = 0·03) in C. muridarum-infected C2Bbe1 cells (0·3 ± 0·4 μm/hr) compared with mock-treated C2Bbe1 cells (1·25 ± 0·3 μm/hr; not shown). Additionally, tight junction protein ZO-1 expression was observable following C. muridarum infection (Fig. 2g). The ability of polarized C2Bbe1 cells to transcytose mouse IgA was also significantly greater following mpIgR transfection compared with untransfected WT C2Bbe1 cells (P < 0·05; Fig. 2h). Taken together, these data confirm that C2Bbe1 cells can be infected when polarized, remain polarized when infected, and following transfection with murine pIgR bind and traffic murine IgA from the basolateral to the luminal compartment.

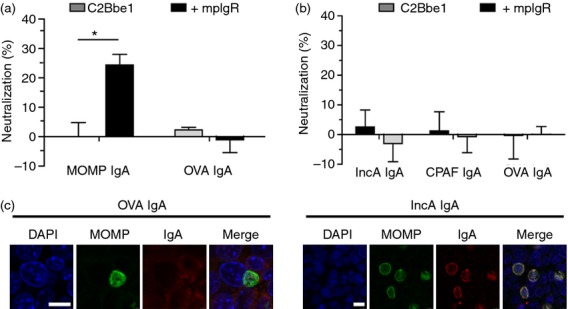

Secretory IgA specific for extra- but not intra-epithelial chlamydial antigens, reduces infection in vitro

Using the purified antigen specific IgA and the in vitro Transwell cell model, we evaluated the ability of pIgR-transported SIgA to neutralize the extra-epithelial chlamydial EB and intra-epithelial replicating chlamydial RB. When anti-MOMP and control anti-OVA IgA were added to polarized cells basolaterally before the addition of EBs to the apical chamber, only MOMP-IgA added to cells expressing mpIgR caused a significant reduction in apical infection (24%; P < 0·05; Fig. 3a). When IgA targeting the chlamydial inclusion membrane protein (IncA) or secreted protease (CPAF) was added to infected cells basolaterally, no significant protection was afforded relative to OVA-IgA controls, regardless of pIgR expression (Fig. 3b). There was also no significant reduction in viability of replicating C. muridarum in subsequent infections (not shown). To confirm that IgA in the process of transcytosis could interact with the chlamydial inclusion, confocal microscopy was also performed (Fig. 3c). IgA targeting IncA was found to co-localize with the inclusion but did not induce aberrant morphology, which has been observed from microinjection of anti-IncA IgG, or neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) delivery of IgG.21,32 Addition of anti-CPAF IgA showed diffuse staining consistent with negative controls (not shown). Taken together, these data demonstrate that IgA targeting extra-epithelial chlamydial antigen (MOMP) prevents infection in a pIgR-dependent manner but IgA targeting intra-epithelial chlamydial antigens is unable to neutralize an established infection when targeting secreted protease CPAF or inclusion membrane protein IncA, despite co-localizing with the chlamydial inclusion.

Figure 3.

The polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR) mediates delivery of neutralizing IgA to extra- but not intra-epithelial chlamydial antigens. C2Bbe1 cells (± murine pIgR) were seeded on Transwell® inserts for 5 days. One hundred micrograms of purified IgA was loaded basolaterally and allowed to transport for 24 hr. Cells were then apically infected with 105 inclusion-forming units of Chlamydia muridarum for 24 hr. Inclusion-forming units were quantified by fluorescence microscopy. (a) Neutralization of chlamydial infection in polarized epithelia loaded basolaterally with polyclonal IgA from mice immunized with major outer membrane protein (MOMP) or ovalbumin (OVA). (b) Neutralization of chlamydial infection in polarized epithelia loaded basolaterally with polyclonal IgA from mice immunized with inclusion membrane protein A (IncA), chlamydial protease-like activity factor (CPAF) or OVA. (c) Confocal microscopy of OVA and IncA-IgA treated cells staining for DNA (DAPI), Chlamydia (anti-MOMP), and mouse IgA (IgA). Results representative of three individual experiments (n = 4 inserts per group). Error bars showing mean ± SEM. Scale = 10 μm. * = P < 0.05.

Secretory IgA specific for extra- but not intra-epithelial chlamydial antigens, reduces infection in vivo

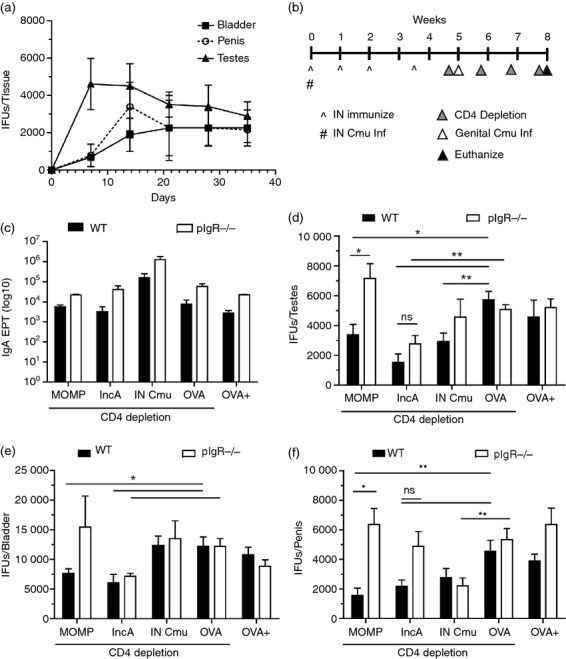

Unlike C. muridarum infection of female C57BL/6 mice, which is generally resolved within 3–5 weeks,33 infected male C57BL/6 mice continued to have a viable infection in the testes, bladder and penis for at least 7 weeks (Fig. 4a). To access the ability of vaccination to reduce infection, 3 weeks post-infection was chosen as this was found experimentally to be the point where infection plateaued in mice. To determine if the in vitro results could be replicated in vivo, we initially attempted intraperitoneal and systemic retro-orbital passive immunization of 0·2 mg of biotinylated purified IgA, and quantified the amount of IgA delivered to the bladder (in urine) and prostate (prostatic fluid). Passive immunization of mice supplied minimal concentrations of biotinylated IgA to the reproductive tract and this rapidly declined to the limit of detection by ELISA (< 10 ng/ml) within 48 hr (see Supporting information, Fig. S1a,b). To overcome the limitations observed from passive immunization, we followed the same immunization schedule used to produce polyclonal IgA against MOMP and IncA for in vitro experiments, but depleted mice of CD4+ T cells before and throughout the infection to isolate the effects of antibodies (Fig. 4b). Previous studies have also identified that live respiratory infection can provide some degree of protection against a genital challenge34; therefore, we included this group to determine if protection was mediated by SIgA/CD4+ T cells. There was no significant change in cachexia between WT and pIgR−/− mice following respiratory challenge, suggesting a limited role for IgA in resolution of respiratory infection (see Supporting information, Fig. S2a). Following 3 weeks of infection or immunization and 23 days of CD4+ depletion, immunized and intranasally infected mice developed a robust antigen-specific IgA (Fig. 4c) and IgG responses (Fig. S2b) and responses were equivalent between both WT and pIgR−/− mice. All groups receiving αCD4 treatment showed > 95% depletion of CD3+ CD4+ T cells in the spleen and draining lymph nodes (Fig. S2c,d).

Figure 4.

Secretory IgA (SIgA) targeting extra- but not intra-epithelial chlamydial antigen reduces burden in the male reproductive tract. (a) Chlamydial burden in the male mouse testes, bladder and penis over 7 weeks was quantified by cell culture (n = 5 per time-point). (b) Schematic representing immunization schedule, CD4 depletion and urogenital chlamydial challenge. (c) Antigen-specific serum IgA titres in wild-type (WT) and pIgR−/− mice following immunization were determined by ELISA with corresponding immunized antigen (intranasal Cmu mouse sera was screened using UV-inactivated elementary bodies). Following 3 weeks of infection, chlamydial burden in the testes (d), bladder (e), and penis (f) of immunized mice was quantified by cell culture. Statistics determined by one-way analysis of variance. Error bars represent mean ± SEM. * = P < 0.05, ** = P < 0.01.

To determine the chlamydial burden across the urogenital tract, we measured infectious load in the testes (Fig. 4d), bladder (Fig. 4e) and penis (Fig. 4f). MOMP-immunization of WT mice afforded a significant reduction in total chlamydial burden in the testes (73%; P < 0·01), bladder (50%; P < 0·05) and penis (73%; P < 0·01), relative to OVA-immunized controls. Importantly, the protection provided by MOMP immunization was entirely abrogated in pIgR−/− (and hence SIgA−/−) mice. Interestingly, previous intranasal infection and CD4 depletion of WT or pIgR−/− produced no significant protection suggesting a limited role of SIgA in immunity acquired from natural infection. Both WT and pIgR−/− mice immunized with IncA had significant reductions of infectious burden in the testes (73% in WT, 46% in pIgR−/−; P < 0·01) and bladder (50% in WT, 41% in pIgR−/−; P < 0·05) when compared with control OVA-immunized mice, suggesting that the observed protection was not dependent on SIgA. Taken together, these findings suggest that pIgR-mediated transport of IgA specific for MOMP provides significant protection in the male reproductive tract. Conversely, targeting intra-epithelial antigen IncA with transcytosing IgA has little effect on reducing infectious burden.

Discussion

Both SIgA and the pIgR play pivotal roles in mucosal homeostasis and immunity.35 During infectious challenge, the pIgR-mediated delivery of secretory component (non-specific innate defence) and more importantly SIgA to the mucosal lumen provides protection from tissue invasion. All Chlamydia spp. infect via the mucosa of either the ocular, respiratory, anorectal or urogenital tracts and so come into direct contact with lumenal SIgA, but also potentially transcytosing dimeric IgA during intra-epithelial chlamydial replication. As pIgR is expressed in both the male and female lower reproductive tracts,36 it probably plays an important protective role in preventing initial infection, but also can prevent ascending infection to the gonads.

To address the potential for antigen-specific IgA to interact with intra- and extra-epithelial chlamydiae, we established a method to purify dimeric IgA from immunized pIgR−/− mice, and apply it to polarized epithelia in the presence or absence of murine pIgR. Apically delivered MOMP-SIgA afforded 24% neutralization of 105 inclusion-forming units, and protection was dependent on transcytosis by pIgR. The rate of transcytosis in this model was calculated in mpIgR transfectants to be approximately 1 μg/cm2 per day (equivalent to 0·35 μg/well or 1·75 μg/ml of polyclonal total IgA transcytosed into the apical compartment). Additionally, the concentration is lower than total polymeric IgA levels observed in rodent vaginal washes (5·29 ± 5·81 μg/ml),37 and much lower than human vaginal fluid (21–118 μg/ml), uterine cervical fluid (3–330 μg/ml) and ejaculate (11–23 μg/ml).36 This suggests that improving anti-MOMP IgA production in the reproductive tract via mucosal immunizations is an attractive target for future vaccine development.

In MOMP-immunized mice the expression of pIgR, and hence transport of SIgA, significantly reduced chlamydial burden in the testes, bladder and penis. In the absence of pIgR (and CD4+ T cells) there was no protection, revealing a limited role for other antigen-specific effectors in the male genital tract (e.g. IgG, CD8+). In fact, we have previously shown that the presence and transcytosis of anti-MOMP IgG provides no protection in the context of infectious burden or pathology.32,38 This inability of MOMP-IgG to neutralize EBs outside the defined in vitro conditions is due to Fcγ receptor or FcRn-mediated uptake of IgG-opsonized EBs, and subsequent EB escape from lysosomal degradation.39 Interestingly, despite minimal pIgR expression in the upper reproductive tract,36 we also observed a significant reduction in chlamydial infection in the testes of MOMP-immunized WT mice, but not pIgR−/− mice, suggesting that SIgA is important in preventing ascending infection. Conversely in previously infected mice, there was no significant pIgR/SIgA-mediated protection on secondary challenge, consistent with the knockout of IgA in previous studies.12 Interestingly, in control groups (OVA immunized +/– CD4-depletion) there was no significant protection in any tissues screened revealing the limited ability of CD4+ T cells to control infection in naive males within the first 3 weeks. A limitation of this in vivo model is that pIgR can also transports pentameric IgM; however, the concentration of IgM in mucosal secretions is 10-fold to 100-fold lower than of IgA or IgG.36 Together, this suggests that vaccines that induce SIgA targeting extra-epithelial chlamydial antigens may significantly reduce infection in males and may also reduce the transmission of infection to females.

Intra-epithelial IgA has been shown to neutralize internalized HIV and influenza viruses and the intracellular niche that Chlamydia establishes during infections may also be vulnerable to trafficking IgA. We demonstrate that pIgR-dependent transcytosis of anti-IncA IgA is able to co-localize with the chlamydial inclusion but does not significantly reduce infection in vitro. We demonstrated that IncA-immunization conferred protection in vivo; however, this was not dependent on SIgA as there were negligible differences between infectious burden in WT and pIgR−/− mice. The in vivo reduction in burden afforded from IncA-immunization was probably due to intra-epithelial IgG transported by FcRn, which we have previously demonstrated in vitro and in vivo.32 Unlike intra-epithelial IgA, which can neutralize pathogens through recycling endosomes,18 intra-epithelial IgG bound to antigen can mediate lysosomal degradation,40 as well as the recruitment of sequestomes providing a neutralizing mechanism beyond steric blocking.32 Vaccines targeting other cytoplasmic-facing Incs (e.g. CT813 or CT229) may produce more promising results as they are expressed earlier during the infectious cycle and may have the potential to arrest chlamydial escape from the endocytic pathway. Intra-epithelial IgA targeting other chlamydial antigens within the inclusion (proteins associated with the replicating RBs) is unlikely to neutralize because SIgA is a large heterodimeric protein (405 000 MW) and the permeability of the inclusion membrane excludes molecules larger than 500 MW.41 The IgA targeting the secreted protease CPAF provided no protection, consistent with other findings.42 Targeting other inclusion-secreted chlamydial proteases; e.g. high temperature requirement A (HtrA) or tail-specific protease (Tsp), with trafficking IgA may also provide little protection as these proteases are also secreted into the host cytoplasm but are unlikely to interact with the microtubule network unilaterally trafficking IgA. Recently, we have demonstrated that FcRn-mediated (bi-directional) trafficking of IgG targeting CPAF also fails to neutralize infection and together with these data demonstrate that neither intra-epithelial CPAF-IgA nor IgG is likely to play a significant role in reducing infectious burden.

Taken together, we demonstrate the pIgR-mediated delivery of SIgA targeting extra-epithelial chlamydial antigens significantly reduces infectious burden in vitro and in vivo whereas IgA targeting prominent intra-epithelial chlamydial antigens provides no significant protection in vitro or in vivo. We confirm that in addition to IgG, transcytosing IgA can also interact with the inclusion revealing the potential to target chlamydial proteins necessary for growth, viability, nutrient acquisition, or escape from host endosomal degradation or antigen-processing/presenting pathways. In the context of a male vaccine, SIgA targeting EB surface-exposed proteins are attractive vaccine candidates to reduce infectious burden throughout the reproductive tract, and will probably also reduce the transmission dose to sexual partners. The converse protection afforded from extra-epithelial IgA but not IgG, and intra-epithelial IgG but not IgA may explain why antibodies have such contradictory roles in many vaccine studies. These data reveal that SIgA targeting surface-exposed EB antigens is indeed important in protective chlamydial immunity, but also that intra-epithelial binding of prominent chlamydial antigens IncA and CPAF by trafficking IgA provides no protection.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Harlan Caldwell, Dr Finn Erik Johansen, Dr Charles Wira, Dr Russell Simmons, Dr Phillip Hansboro, Dr Graham Le Gros and Dr John Aaskov for graciously supplying us with the vectors and cell lines used in this study. We would also like to thank Dean Andrew, Dr Samantha Dando, and Dr Melanie Barnes for their technical assistance.

Glossary

- CPAF

chlamydial protease-like activity factor

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- EB

elementary body

- IFN

interferon

- IncA

inclusion membrane protein A

- MOMP

major outer membrane protein

- OVA

ovalbumin

- pIgR

Polymeric immunoglobulin receptor

- RB

reticulate body

- SIgA

secretory IgA

- TEER

transepithelial electrical resistance

- TNF

tumour necrosis factor

- WT

wild-type

- ZO-1

zona occludens 1

Disclosures

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1. Immunoglobulin A in reproductive secretions following passive immunization.

Figure S2. Antigen-specific immunoglobulin responses and CD4+ T-cell numbers at time of euthanasia.

References

- World Health Organization. Global Prevalence and Incidence of Selected Curable Sexually Transmitted Infections. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stamm WE. Chlamydia trachomatis infections: progress and problems. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(Suppl. 2):S380–3. doi: 10.1086/513844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz BP. Estimating transmission probabilities for chlamydial infection. Stat Med. 1992;11:565–77. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780110502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunham RC, Rekart ML. The arrested immunity hypothesis and the epidemiology of chlamydia control. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:53–4. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31815e41a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Meara CP, Andrew DW, Beagley KW. The mouse model of Chlamydia genital tract infection: a review of infection, disease, immunity and vaccine development. Curr Mol Med. 2013;8:8. doi: 10.2174/15665240113136660078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane M, Armitage CW, O’Meara CP, Beagley KW. Towards a Chlamydia trachomatis vaccine: how close are we? Future Microbiol. 2010;5:1833–56. doi: 10.2217/fmb.10.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunham RC, Rey-Ladino J. Immunology of Chlamydia infection: implications for a Chlamydia trachomatis vaccine. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:149–61. doi: 10.1038/nri1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham KA, Beagley KW. Male genital tract chlamydial infection: implications for pathology and infertility. Biol Reprod. 2008;79:180–9. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.067835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham KA, Carey AJ, Timms P, Beagley KW. CD4+ T cells reduce the tissue burden of Chlamydia muridarum in male BALB/c mice. Vaccine. 2010;28:4861–3. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yule TD, Tung KS. Experimental autoimmune orchitis induced by testis and sperm antigen-specific T cell clones: an important pathogenic cytokine is tumor necrosis factor. Endocrinology. 1993;133:1098–107. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.3.8103448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham KA, Carey AJ, Finnie JM, et al. Poly-immunoglobulin receptor-mediated transport of IgA into the male genital tract is important for clearance of Chlamydia muridarum infection. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;60:405–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2008.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SG, Morrison RP. The protective effect of antibody in immunity to murine chlamydial genital tract reinfection is independent of immunoglobulin A. Infect Immun. 2005;73:6183–6. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.6183-6186.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunham RC, Kuo CC, Cles L, Holmes KK. Correlation of host immune response with quantitative recovery of Chlamydia trachomatis from the human endocervix. Infect Immun. 1983;39:1491–4. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.3.1491-1494.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pate MS, Hedges SR, Sibley DA, Russell MW, Hook EW, III, Mestecky J. Urethral cytokine and immune responses in Chlamydia trachomatis-infected males. Infect Immun. 2001;69:7178–81. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.11.7178-7181.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter T, Meng Q, Shen Z, Zhang Y, Su H, Caldwell H. Protective efficacy of major outer membrane protein-specific immunoglobulin A (IgA) and IgG monoclonal antibodies in a murine model of Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract infection. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4704–14. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4704-4714.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal S, Theodor I, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. Monoclonal immunoglobulin A antibody to the major outer membrane protein of the Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis biovar protects mice against a chlamydial genital challenge. Vaccine. 1997;15:575–82. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00206-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomsel M, Heyman M, Hocini H, Lagaye S, Belec L, Dupont C, Desgranges C. Intracellular neutralization of HIV transcytosis across tight epithelial barriers by anti-HIV envelope protein dIgA or IgM. Immunity. 1998;9:277–87. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80610-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YT, Wright A, Gao X, Kulick L, Yan H, Lamm ME. Intraepithelial cell neutralization of HIV-1 replication by IgA. J Immunol. 2005;174:4828–35. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazanec MB, Coudret CL, Fletcher DR. Intracellular neutralization of influenza virus by immunoglobulin A anti-hemagglutinin monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 1995;69:1339–43. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.1339-1343.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell HD, Kromhout J, Schachter J. Purification and partial characterization of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1981;31:1161–76. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.3.1161-1176.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackstadt T, Scidmore-Carlson MA, Shaw EI, Fischer ER. The Chlamydia trachomatis IncA protein is required for homotypic vesicle fusion. Cell Microbiol. 1999;1:119–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.1999.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AL, Johnson KA, Lee JK, Sutterlin C, Tan M. CPAF: a Chlamydial protease in search of an authentic substrate. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002842. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Meara CP, Armitage CW, Harvie MC, Timms P, Lycke NY, Beagley KW. Immunization with a MOMP-based vaccine protects mice against a pulmonary Chlamydia challenge and identifies a disconnection between infection and pathology. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snarvely EA, Kokes M, Dunn JD, Saka HA, Nguyen BD, Bastidas RJ, McCafferty DG, Valdivia RH. Reassessing the role of the secreted protease CPAF in Chlamydia trachomatis infection through genetic approaches. Pathog Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12179. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12179. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roe M, Norderhaug IN, Brandtzaeg P, Johansen FE. Fine specificity of ligand-binding domain 1 in the polymeric Ig receptor: importance of the CDR2-containing region for IgM interaction. J Immunol. 1999;162:6046–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal S, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. New murine model for the study of Chlamydia trachomatis genitourinary tract infections in males. Infect Immun. 2004;72:4210–6. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.4210-4216.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Meara CP, Armitage CW, Harvie MC, Andrew DW, Timms P, Lycke NY, Beagley KW. Immunity against a Chlamydia infection and disease may be determined by a balance of IL-17 signaling. Immunol Cell Biol. 2013;24:92. doi: 10.1038/icb.2013.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Chai J, Hart PJ, Zhong G. Identifying catalytic residues in CPAF, a Chlamydia-secreted protease. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;485:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen FE, Pekna M, Norderhaug IN, Haneberg B, Hietala MA, Krajci P, Betsholtz C, Brandtzaeg P. Absence of epithelial immunoglobulin A transport, with increased mucosal leakiness, in polymeric immunoglobulin receptor/secretory component-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1999;190:915–22. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.7.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley R, Wines B, Willoughby N, Basu I, Proft T, Fraser JD. The staphylococcal superantigen-like protein 7 binds IgA and complement C5 and inhibits IgA-Fc alpha RI binding and serum killing of bacteria. J Immunol. 2005;174:2926–33. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore ER, Fischer ER, Mead DJ, Hackstadt T. The chlamydial inclusion preferentially intercepts basolaterally directed sphingomyelin-containing exocytic vacuoles. Traffic. 2008;9:2130–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00828.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage CW, O’Meara CP, Harvie MCG, Timms P, Blumberg RS, Beagley KW. Divergent outcomes following transcytosis of IgG targeting intracellular and extracellular chlamydial antigens. Immunol Cell Biol. 2014;92:417–26. doi: 10.1038/icb.2013.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su H, Feilzer K, Caldwell H, Morrison R. Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract infection of antibody-deficient gene knockout mice. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1993–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.1993-1999.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Zeng H, Li Z, Lei L, Yeh IT, Wu Y, Zhong G. Protective immunity against mouse upper genital tract pathology correlates with high IFNγ but low IL-17 T cell and anti-secretion protein antibody responses induced by replicating chlamydial organisms in the airway. Vaccine. 2012;30:475–85. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen FE, Kaetzel CS. Regulation of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor and IgA transport: new advances in environmental factors that stimulate pIgR expression and its role in mucosal immunity. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:598–602. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PD, MacDonald TT, Blumberg RS. Principles of Mucosal Immunology. New York City: Garland Science; 2012. pp. 121–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wu HY, Abdu S, Stinson D, Russell MW. Generation of female genital tract antibody responses by local or central (common) mucosal immunization. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5539–45. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.10.5539-5545.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham KA, Carey AJ, Hafner L, Timms P, Beagley KW. Chlamydia muridarum major outer membrane protein-specific antibodies inhibit in vitro infection but enhance pathology in vivo. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;4:4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scidmore MA, Rockey DD, Fischer ER, Heinzen RA, Hackstadt T. Vesicular interactions of the Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion are determined by chlamydial early protein synthesis rather than route of entry. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5366–72. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5366-5372.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Ye L, Tesar DB, Song H, Zhao D, Bjorkman PJ, Roopenian DC, Zhu X. Intracellular neutralization of viral infection in polarized epithelial cells by neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn)-mediated IgG transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:18406–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115348108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieshaber S, Swanson JA, Hackstadt T. Determination of the physical environment within the Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion using ion-selective ratiometric probes. Cell Microbiol. 2002;4:273–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy AK, Chaganty BK, Li W, Guentzel MN, Chambers JP, Seshu J, Zhong G, Arulanandam BP. A limited role for antibody in protective immunity induced by rCPAF and CpG vaccination against primary genital Chlamydia muridarum challenge. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2009;55:271–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00517.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Immunoglobulin A in reproductive secretions following passive immunization.

Figure S2. Antigen-specific immunoglobulin responses and CD4+ T-cell numbers at time of euthanasia.