Abstract

Bipolar disorders (BDs) and addictions constitute reciprocal risk factors and are best considered under a unitary perspective. The concepts of allostasis and allostatic load (AL) may contribute to the understanding of the complex relationships between BD and addictive behaviors. Allostasis entails the safeguarding of reward function stability by recruitment of changes in the reward and stress system neurocircuitry and it may help to elucidate neurobiological underpinnings of vulnerability to addiction in BD patients. Conceptualizing BD as an illness involving the cumulative build-up of allostatic states, we hypothesize a progressive dysregulation of reward circuits clinically expressed as negative affective states (i.e., anhedonia). Such negative affective states may render BD patients more vulnerable to drug addiction, fostering a very rapid transition from occasional drug use to addiction, through mechanisms of negative reinforcement. The resulting addictive behavior-related ALs, in turn, may contribute to illness progression. This framework could have a heuristic value to enhance research on pathophysiology and treatment of BD and addiction comorbidity.

Keywords: bipolar disorders, addiction vulnerability, allostasis and allostatic load, comorbidity, hedonic tone and anhedonia, dopaminergic system, reward system, CRF/HPA axis and stress system

Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a severe, often chronic condition with lifetime prevalence rates of up to 6.5% for bipolar spectrum disorders in the general population (1). BD patients frequently report co-occurring substance-use disorders (SUDs) and behavioral addictions (1–5). The rates of alcohol and other SUDs are significantly higher in subjects with BD than in the general population (1, 6). The co-occurrence of BD and addiction has important clinical implications (3, 7). Bipolar patients with comorbid conditions present with a more severe course of illness (8), characterized by an overall worse clinical picture (9), poorer treatment outcome (10–12), higher suicidality (13), and mortality (14).

Several studies have aimed to identify the endophenotypical features predisposing to the development of addiction in the general population, as well as in the context of BD. These studies focused on genetic vulnerability, impulsive traits, and decision-making impairment (15–19).

The aim of this paper is to present the possible contribution of the concept of allostasis as a framework linking BD and addiction. We hypothesize that the concepts of allostasis and allostatic load (AL) may contribute to the understanding of the complex relationships between BD and addictive behaviors (20–22). Allostasis entails the safeguarding of reward function stability by recruitment of changes in the reward and stress system neurocircuitry (21) and it may help to elucidate neurobiological underpinnings of vulnerability to addiction in BD patients.

Methods

Computerized database, i.e., PubMed, Psycinfo, Cochrane Library were searched using the following terms: “allostasis,” “AL,” “reward,” “hedonic tone,” “stress system” cross-referenced with “BD,” “addiction,” and “SUDs.” The results of this search are presented in this article, and examined in light of a unifying hypothesis with a potential heuristic value to inform and provide direction to future research in this intriguing area.

Relevance of Allostasis in BD and Addiction Field

Bipolar disorders

Bipolar disorders is a complex and multifactorial disease, with genetic and environmental factors contributing to its clinical expression (23). BD can also be conceptualized as an illness involving the cumulative build-up of allostatic states, whereas AL progressively increases as stressors and mood episodes occur over time (24). Indeed, it has been postulated that mood episodes function as allostatic states, generating a load that is responsible for illness progression commonly seen in BD (25, 26). AL may contribute to a better understanding of BD, particularly of inter-episodic phenomena such as vulnerability to stress, cognitive symptoms (26), and higher physical comorbidity rates (24). BD patients present with alterations in major mediators of AL. They exhibit for instance, persistent dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis, circadian rhythm disturbances, altered immunity as well as pro-inflammatory and oxidative stress states [please refer to the review Kapczinski et al. (24)]. Neurotrophic factors play an important role in maintaining a physiological brain function. They have been shown to be modulated by environmental events in various psychopathological conditions (27), and their role has been confirmed also in pathophysiology and staging of BD (28–31).

These alterations are greater during the acute stages of the disease, but remain sub-threshold even during remission (24). When mediators of allostasis – essential for brain functioning and protection – are driven by mechanisms of homeostatic dysregulation, they act in excess and damage brain tissue (32, 33), which is particularly vulnerable to the harmful effects of the AL [i.e., oxidative stress (34)]. Impairment in the stress response has been acknowledged as a core feature of BD clinical expression, as well as having a central role in the concept of AL (23). Although the exact mechanisms, by which stress exerts its effect on the brain, remain largely unknown, the HPA axis is one of the main stress response systems activated with the objective to maintain stress adaptation for as long as it is necessary (23). The HPA axis is clearly altered in mood disorders, as well as in BD (35–38). Glucocorticoids play an important role in the process whereby the mediators of allostasis interact with neurotransmitter systems and brain peptides resulting in neuroplastic alterations in the hippocampus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex (39, 40). The role of stress in triggering mood episodes is well established, particularly in the early stages of illness (41, 42). It has been hypothesized that early life stress could affect the endocrine system, producing a stable reprograming of HPA axis (43), leading to an impairment in brain area involved in emotional processing (44). Alterations in emotional processing involving amygdala circuitry and are related to BD symptoms in several ways. Evidence from amygdala-dependent tasks points to a dysregulation of amygdala-related neurocircuitry in BD patients (45). These alterations render BD patients more prone to trigger AL (23), through a greater stress vulnerability.

Addiction

Drug addiction can be conceptualized as a stress-surfeit disorder (46). It is characterized by the occurrence of an allostatic state in the brain reward system, reflected in a chronic deviation of reward thresholds (46–48). An allostatic state reflects a new balance, a state of chronic deviation of the regulatory system from its normal (homeostatic) operating level to a pathological (allostatic) operating level (47). From a drug addiction perspective, repeated compromised activity in the dopaminergic system and sustained activation of the corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) system may lead to an AL that contributes significantly to the transition from occasional drug use to drug addiction (49, 50). This model may be applied to pathological gambling as well (51). The transition from occasional controlled drug use to loss of control is endorsed by the emergence of negative affective states, resulting from the abovementioned allostatic dysregulations (i.e., the AL), with a shift from impulsivity to compulsivity and from positive reinforcement to negative reinforcement (49, 52).

Addiction implies dysregulation of the brain reward system (48, 53). Several studies highlighted that negative affective states are a result of the alteration of neurobiological elements central to reward and stress systems (50, 54, 55), in brain areas such as the ventral striatum and the extended amygdala (56, 57). In addition to the reduction of dopaminergic and opioidergic functioning, dysregulation of reward is also mediated by the activation of brain stress systems (i.e., CRF), in the areas of the extended amygdala (57). Stress system alterations have been observed in both the acute and chronic phases of addiction, and seem to play a role in determining reward dysregulation (48, 54). Acute withdrawal raises the threshold for reward, leads to an increase in dysphoric symptoms as well as an increase of CRF levels in the amygdala (49, 58). These changes result from sensitization of the brain stress system in response to the phenomena of abstinence, and persist for a long period of time following cessation of drug intake [protracted withdrawal (59)]. Protracted withdrawal symptoms are related to the compulsivity characterizing addictive disorders, and are factors involved in determining relapse. In addition to CRF, other mediators (norepinephrine, dynorphin, and neuropeptide Y) have been investigated and found to play a role in the transition from impulsivity to compulsivity (58, 60). As a whole, these elements constitute the brain stress system of the extended amygdala, a counter-adaptive system that interacts with the reward system and determine its reduced function (48).

Neurobiological Issues of BD-SUD Comorbidity

A complete review of neurobiological features in BD-SUD comorbidity is beyond the purpose of this paper. Familial and illness course characteristics of BD and addictive disorders, as well as shared underlying mechanisms suggest potentially important genetic overlap (19, 61, 62). Preliminary findings hint at the existence of a shared genetic vulnerability for BD and SUDs (15). Johnson et al. (63) found convergent genome-wide association results for BD and SUDs. Products of one group of these genes are likely to play substantial roles in the initial and/or plasticity-related “wiring” of the brain (63). A second group of genes is the family of clock genes, implicated in the regulation of behavioral and physiological periodicity (19). Recently, a significant genetic overlap between candidate genes for both alcoholism and BD was found (64, 65), by using the d-box binding protein knockout mouse, a stress-reactive animal model developed consistently with allostasis and stress-surfeit theory of addiction (46).

To date, no studies have specifically investigated neuroimaging correlates in comorbid BD–SUD patients. Several studies describe putative mechanisms involved in BD vulnerability to addiction. Structural imaging studies in BD patients found volume reductions in prefrontal cortex [PFC (66)], which is involved in encoding incentive information (67). During Iowa gambling task (IGT), BD patients showed abnormalities in the dorsal and ventral PFC, while lateral temporal and polar regions displayed increased activation (68). Jogia et al. (69) confirmed these observations and also reported a greater activation in the anterior cingulate cortex of BD patients performing the IGT and in the insula during the n-back working memory task. Reduced functioning of the dopamine transporter (DAT) has been linked to BD (70–72). Animal models may provide insight into the role of the dopaminergic system in risk-taking behavior. Mice with reduced DAT functioning exhibit a behavioral profile consistent with manic patients and increased risk-taking behavior during a mouse version of the IGT (70). Evidence from these animal model studies and translational human research in BD subjects (73, 74), allows us to hypothesize that system-related change involving functioning of the dopamine system play a role in impulsive choice, risk-taking behavior, and reward, thus help guiding future studies in BD–SUD subjects.

Allostatic Dysregulation of Reward Might Underpin Bipolar Vulnerability to Addiction

Dopaminergic mechanisms are likely to play a key role in the understanding of the pathophysiology of BD and the clinical phenomena of mania and depression have previously been conceptualized in terms of an increase or a decrease in dopaminergic function, respectively (75, 76). Also, converging lines of evidence suggest that dopamine is a key neurotransmitter mediating hedonic allostasis in drug and behavioral addictions (49, 77). From a neurobiological perspective, a central dopaminergic dysfunction has been widely proposed as a neurobiological correlate of anhedonia (78). Different studies suggest anhedonia as a key symptom in addictive disorders, both as part of a withdrawal syndrome and as a relevant factor involved in relapses (51, 59, 79). In addition to dopamine, other neurotransmitters are believed to encode the hedonic experience [endogenous opioids, serotonin (80)], while long-lasting alterations involving cue-induced craving and relapse are thought to result from neuroplastic changes in glutamatergic circuitry (81–83).

Several studies provide support for reward dysregulation accounts in BD (16, 18, 45, 69, 84–95) (Table 1), characterizing neural dynamics underlying inter-temporal reward processing (90). Possibly emotional dysregulation present in BD is related to hypersensitivity to reward-relevant stimuli (93). Impulsive and unsafe decision-making in BD is linked to decreased sensitivity to emotional contexts involving rewards or punishments, possibly reflecting altered appraisal of prospective gains and losses associated with certain behaviors (89). It has been proposed that anhedonia could be mediated by a change in reward sensitivity (78), which has different behavioral consequences involving either stress-related and dopaminergic processes (96). In BD, sustained allostatic states and the consequent cumulative brain damage resulting from increased AL may play a part in the occurrence of negative affective states (i.e., anhedonia) that persist even during periods of remission (84). Counter-adaptive processes, such as opponent process that are part of the normal homeostatic limitation of reward function (55) fail to return within the normal homeostatic range and are hypothesized to repeatedly drive the allostatic state [decreased dopamine and opioid peptide function, increased CRF activity (49)]. This allostatic state is hypothesized to be reflected in a chronic deviation of reward set point that is fueled, not only by dysregulation of reward circuits per se but also by recruitment of brain and hormonal stress responses.

Table 1.

Reward-system alterations and vulnerability to addiction in euthymic bipolar patients.

| Aim | Methods | Sample | Results | Comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait-related decision-making impairment | IGT, sensitivity-to-punishment index | 167 BD (45 mania, 32 depressed, 90 euthymic), 150 HC | Manic, depressed, and euthymic BPs selected significantly more cards from the risky decks than HC. BD preferred decks that yielded infrequent penalties over those yielding frequent penalties. | BD have a trait-related impairment in decision-making that does not vary across illness phase, predicted by high depressive scores | (16) |

| Decision-making deficits; temporal discounting of reward | Delay discounting task | 22 BD, 21 SZ, 30 HC | BD and SZ groups discounted delayed rewards more steeply than did the healthy group (even after controlling for current substance use). Working memory or intelligence scores negatively correlated with discounting rate. | BD patients value smaller, immediate rewards more than larger, delayed rewards | (18) |

| Neural mechanisms related to motivation | fMRI, probabilistic reversal learning task | 19 BD, 19 HC, 22 relatives, 22 HC | Increased activation in response to reward and reward reversal contingencies in the left medial orbitofrontal cortex in BD. Activation of the amygdala in response to reward reversal was increased. | Increased activity of OFC and amygdala, related to heightened sensitivity to reward and deficient prediction error signal | (45) |

| Functional brain abnormalities during reward and working memory processing | fMRI, IGT, n-back task | 36 BD, 37 HC | BD showed inefficient engagement within the ventral frontopolar prefrontal cortex with segregation along the medial–lateral dimension for reward and working memory processing, respectively. Greater activation in the anterior cingulate cortex during the IGT and in the insula during the n-back task. | Over-activation in regions involved in emotional arousal is present even in tasks that do not typically engage emotional systems | (69) |

| Hedonic capacity | SHAPS, SANS-An, VAS-HC | 107 BD, 86 MDD, 106 HC | SHAPS, SANS-An, and VAS scores significantly higher in affective disorder patients. 20.5% of BDs showed significant reduction in hedonic capacity | Reduced hedonic capacity persists irrespective of mood state | (84) |

| Relationship between SUD and overweight-obesity | Data from CCHS, BMI | 36,984 individuals | Overweight/obese bipolar individuals had a lower rate of SUD than the normal weight sample (13 vs. 21%). BD + SUD had a lower rate of overweight/obesity when compared with BD non-SUD (39 vs. 54%) | Comorbid addictive disorders may compete for the same brain reward systems | (85) |

| Neural correlates of reward and decision-making | IGT, RDMUR, ERP-assessed RDGT | 13 BD, 12 ADHD, 25 HC | BD group showed a pattern of enhanced ‘learning by feedback’ and ‘sensitivity to reward magnitude’ regardless of valence. This ERP pattern was associated with mood and inhibitory control. Reduced responses of the cingulate cortex to the valence and magnitude of rewards in BD. | Altered decision-making process in BD with the involvement of cingulate cortex | (86) |

| Impulsivity | BIS-11, stop signal task, delayed reward task, continuous performance task | 108 BD1 (1-year FU), 48 HC | At baseline (manic/mixed state), BD demonstrated significant deficits on all three tasks. Performance on the three behavioral tasks normalized upon switching to depression or developing euthymia. Elevated BIS-11 scores persist across phases of illness. | Impulsivity has both affective-state dependent and trait components in BD. | (87) |

| Dysfunctional reward processing | Probabilistic reward task | 18 BD, 25 HC | BD showed a reduced and delayed acquisition of response bias toward the more frequently rewarded stimulus | Dysfunctional reward learning in situations requiring integration of reinforcement information in BD | (88) |

| Risky decision-making (rewards vs punishments) | Risky decision-making task | 20 BD-2, DF, 20 HC | The BD participants overestimated the number of bad outcomes arising out of positively framed dilemmas. Risky choice in BD is associated with reduced sensitivity to emotional contexts that highlight rewards or punishments. | In BD, altered valuations of prospective gains and losses associated with behavioral options. | (89) |

| Neural correlates of hypersensitivity to immediate reward | (1) Two choice impulsivity paradigm (2) Delay discounting task, EEG | 1) 32 subjects 2) 32 subjects | (1) The hypomania-prone group made significantly more immediate choices than the control group. (2) The hypomania-prone group evidenced greater differentiation between delayed and immediate outcomes in early attention-sensitive (N1) and later reward-sensitive (feedback-related negativity) components. | Provide support for reward dysregulation accounts of BD, characterizing neural dynamics underlying inter-temporal reward processing | (90) |

| Substance sensitivity and sensation seeking | SCID-I, SCI-SUBS | 57 BD1-SUD, 47 BD1, 35 SUD, 50 HC | BD + SUD and SUD have higher scores on self-medication, substance sensitivity and sensation seeking. No differences in reasons for substance use between BD + SUD and SUD (improving mood; relieving tension; alleviating boredom; achieving/maintaining euphoria; increasing energy). | In BD patients, substance sensitivity and sensation seeking traits are possible factors associated with SUD development | (91) |

| Reward sensitivity and positive affect | RPA; RRI; BQL-BD | 90 BD1, 72 HC | The majority of BD-1 reported avoiding at least one rewarding activity as a means of preventing mania. Lower quality of life related to dampening positive emotions. | People with BD-1 report avoiding rewarding activities and dampening positive emotion | (92) |

| Neural correlates of hypersensitivity to reward | fMRI, anticipation and outcome reward task | 21 BD1, 20 HC | BD displayed greater ventral striatal and right-sided OFC (BA 11) activity during anticipation, but not outcome, of monetary reward. BD also displayed elevated left-lateral OFC (BA 47) activity during reward anticipation | Elevated ventral striatal and OFC activity during reward anticipation as a mechanism underlying predisposition to hypo/mania in response to reward-relevant cues. | (93) |

| Sensitivity to positive and negative feedback | Learning task (positive/negative feedback) | 23 BD1, 19 MD, 19 HC | The quality of the last affective episode was the only significant predictor. BD1 patients who last experienced a manic episode learned well from positive but not negative feedback, whereas BD1 patients who last experienced a depressive episode showed the opposite pattern | Differences in response to positive and negative consequences carrying over into the euthymic state are related to the polarity of the preceding episode | (94) |

| Motivational aspects of decision-making in relation to reward and punishment | IGT | 28 BD (14 acute and 14 remitted) 25 HC | Acute BD were characterized by the tendency to make erratic choices. Low choice consistency improved the prediction of acute BD beyond that provided by cognitive functioning and self-report measures of personality and temperament. | Low choice consistency in BD patients | (95) |

BD, bipolar disorder; SZ, schizophrenia; HC, healthy controls; SUD, substance-use disorder; SCID-I, structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders; SCI-SUBS, structured clinical interview for the spectrum of substance use; DF, drug-free; SHAPS, Snaith–Hamilton pleasure scale; SANS-An, scale for the assessment of negative symptoms, subscale for anhedonia/asociality; VAS-HC, visual analog scale for hedonic capacity; BIS-11, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale; RPA, responses to positive affect measure; BQL-BD, brief quality of life in bipolar disorder scale; RRI, reward responses inventory; IGT, Iowa gambling task; RDMUR, task of rational decision-making under risk; RDGT, rapid-decision gambling task; ERP, event-related potentials; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; EEG, electroencephalography; CCHS, Canadian Community Health Survey-Mental Health and Well-Being; OFC, orbitofrontal cortex; BA, Brodmann area; FU, follow-up.

Altered functioning of the HPA axis may hold clues to the nature of the motivational changes accompanying addiction and vulnerability to addiction (97). Pre-existing alterations in frontal–limbic interactions with the HPA may reflect addiction-proneness, as shown in studies of offspring of alcohol- and drug-abusing parents (98). Alterations in the CRF/HPA axis may exert effects on the corticostriatal-limbic motivational, learning, and adaptation systems that include mesolimbic dopamine, glutamate, and gamma-amino-butyric acid (GABA) pathways (97), representing the underlying pathophysiology associated with stress-related risk of addiction.

The effects of these allostatic changes in the mesocorticolimbic brain system and in CRF/HPA axis contribute to the underlying pathophysiology associated with stress-related risk of addiction in BD (99). In BD patients, we hypothesize that the hedonic response to an acute drug administration occurs on a pre-existing allostatic dysregulation of the dopamine and CRF system. BD-related allostatic alterations in reward and stress systems thereby constitute vulnerability factors to the development of addiction in subjects exposed to occasional drug use. The failure to self-regulate these systems, determined by the collective contribution of endogenous factors linked to BD and of exogenous substances, results in an AL leading to a facilitated transition to drug addiction.

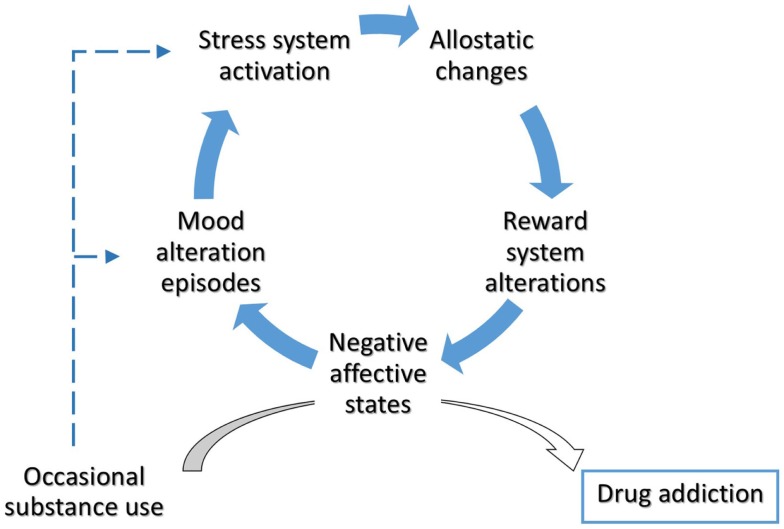

Dysphoria triggers drug intake, accompanied by an intense activity of the dopaminergic system and followed by a compensatory decrease in the dopaminergic system and increase in the CRF system to re-establish the allostatic set point. Such negative affective states may render BD patients more vulnerable to drug addiction, favoring a very rapid transition from occasional, recreational drug use to compulsive, pathological, drug dependence. The resulting addictive behavior-related ALs, in turn, may contribute to illness progression (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Allostatic alterations in bipolar disorder and vulnerability to addiction. Throughout the involvement of enduring alterations in stress- and reward-system, BD patients could experience a rapid transition from occasional drug use to drug addiction. The occurrence of negative affective states mediate the switch from impulsivity to compulsivity in bipolar patients. Cumulative effects of mood episodes and substance use on stress system have been hypothesized.

Clinical Implications and Future Perspectives

Converging data from addiction and BD studies suggest that these disorders involve similar allostatic processes, and allostasis can contribute to unify these disorders under a unitary perspective. In this context, the concepts of allostasis and AL provide both a pathophysiological model for the understanding of BD-addiction comorbidity and a new perspective for the development of novel therapeutic strategies for the treatment of comorbid patients (100, 101).

Allostatic alterations in brain reward system could render BD patients more vulnerable to drug addiction, favoring a very rapid transition from occasional, recreational drug use to compulsive, pathological, and drug dependence. This framework allows us to explain the high comorbidity rate between these disorders (2), as well as its relevance in early-onset patients (8, 102). Furthermore, it enables us to identify the factors of vulnerability to addiction in inter-episode periods as well (i.e., sub-threshold reward-system dysfunctions) (84). A more accurate monitoring of comorbidity-risk (103), coupled with the inclusion of specific tools for the assessment of hedonic tone, may contribute to early intervention on addiction-vulnerability factors and to initiate primary prophylaxis for substance misuse in youth suffering from BD with high-risk for addiction (104–106).

Currently, accruing evidence suggests that mood alteration episodes increase the risk of substance use (107, 108). Patients with dual disorders are more likely to use substances to self-regulate perceived internal factors (109, 110). SUD comorbidity in BD patients was preceded by greater manic symptoms in the previous period (104), as well as the persistence of depressive symptoms was associated with higher craving and increased risk to develop substance dependence (104, 108). Moreover, in gambling disorder (GD) patients depressive symptoms predicted gambling urges and duration (111). Allostasis framework enables us to extend the self-medication theory (112) beyond the established clinical domains, increasing the understanding of the interactions between BD symptoms and substance use. For instance, euthymic bipolar patients are more likely to experience cognitive impairment (deficits in measures of executive functions, verbal learning, immediate and delayed verbal memory, abstraction, sustained attention) (113). Cannabis abuse seems to positively affect cognitive function in a BD sample (114), and it may represent an attempt to counterbalance these alterations, even though causing an increased risk of rapid cycling and an earlier onset of manic episodes (114, 115).

Practitioners should be particularly vigilant in monitoring for substance misuse early after the onset of mood disorders, as well as they should be aware of personality traits related to the risk of addiction, in particular antisocial and schizotypal personality disorder (11, 116). The existence of additional risk factors [i.e., ADHD (117)] for the development of a BD-SUD comorbidity is controversial (105, 118). Combined with a specific role of traumatic stress as independent vulnerability-factor (99, 119), these elements contribute to the build-up of a cumulative AL. Clinicians can therefore incorporate specific therapy approaches for dual disorders (120–122) to target adherence weaknesses (123) and to enhance the effects of existing treatments.

Given the notion that exposure to stress or drugs leads to enduring changes in gene expression or activation of transcription factors, determining long-term neuroadaptation of brain functions, a promising field of future research could involve the detection of valuable markers of AL (124). In fact, markers of AL could contribute to prevention strategy (105, 116, 125); moreover, they could improve clinical monitoring and prognostic assessment of comorbid patients.

The clinical management of BD-SUD subjects requires a careful distinction between mood and withdrawal/intoxication symptoms (126, 127). Neuroimaging studies indicate that brain regions involved in mood regulation lie in close proximity to regions involved in motivation and craving (128). The complex interplay between addiction and BD domains, mediated by the involvement of similar neurobiological systems, requires further studies to better delineate how BD and SUD operate as reciprocal risk factors (105, 129). Recently, it has been proposed to focus on some clinical domain by using strategies aimed to treat both disorders simultaneously (101, 130). Besides reducing the recurrence of affective episodes, and exerting neuroprotective, mood stabilizers have been recently shown to have anti-anhedonic properties (131–134) with potential utility in the treatment of comorbid conditions (135–141). In addition, glutamatergic agents have been demonstrated to be effective in the treatment of both mood (142) and addictive disorders (82, 143); furthermore, they have been recently proposed as a valuable therapeutic option in the treatment of comorbid patients (139).

Future studies aimed at assessing brain AL in patients with BD and addiction comorbidity may help to shed light on the complex interactions underlying neurobiological vulnerability to these disorders and to improve their treatment options. Early effective treatment strategies specifically devised for comorbid patients (104, 125) could prevent, or possibly reverse, some of the neurobiological abnormalities and indicators of AL, thus potentially leading to numerous benefits for these patients.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

AL, allostatic load; BD, bipolar disorder; CRF, corticotropin-releasing factor; GD, gambling disorder; HPA, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (axis); SUD, substance-use disorder.

References

- 1.Vornik LA, Brown ES. Management of comorbid bipolar disorder and substance abuse. J Clin Psychiatry (2006) 67(Suppl 7):24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Hasin DS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of bipolar I disorder and axis I and II disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. J Clin Psychiatry (2005) 66(10):1205–15 10.4088/JCP.v66n1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altamura AC. Bipolar spectrum and drug addiction. J Affect Disord (2007) 99(1–3):285. 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Nicola M, Tedeschi D, Mazza M, Martinotti G, Harnic D, Catalano V, et al. Behavioural addictions in bipolar disorder patients: role of impulsivity and personality dimensions. J Affect Disord (2010) 125(1–3):82–8. 10.1016/j.jad.2009.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pettorruso M, Di Nicola M, De Risio L, Fasano A, Martinotti G, Conte G, et al. Punding behavior in bipolar disorder type 1: a case report. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci (2014) 26(4):E8–9 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13090217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. Results from the epidemiologic catchment area (ECA) study. JAMA (1990) 264(19):2511–8. 10.1001/jama.1990.03450190043026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagiolini A, Forgione R, Maccari M, Cuomo A, Morana B, Dell’Osso MC, et al. Prevalence, chronicity, burden and borders of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord (2013) 148(2–3):161–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai HC, Lu MK, Yang YK, Huang MC, Yeh TL, Chen WJ, et al. Empirically derived subgroups of bipolar I patients with different comorbidity patterns of anxiety and substance use disorders in Han Chinese population. J Affect Disord (2012) 136(1–2):81–9. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frye MA, Salloum IM. Bipolar disorder and comorbid alcoholism: prevalence rate and treatment considerations. Bipolar Disord (2006) 8(6):677–85. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00370.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazza M, Mandelli L, Di Nicola M, Harnic D, Catalano V, Tedeschi D, et al. Clinical features, response to treatment and functional outcome of bipolar disorder patients with and without co-occurring substance use disorder: 1-year follow-up. J Affect Disord (2009) 115(1–2):27–35. 10.1016/j.jad.2008.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mandelli L, Mazza M, Di Nicola M, Zaninotto L, Harnic D, Catalano V, et al. Role of substance abuse comorbidity and personality on the outcome of depression in bipolar disorder: harm avoidance influences medium-term treatment outcome. Psychopathology (2012) 45(3):174–8. 10.1159/000330364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McIntyre RS, Nguyen HT, Soczynska JK, Lourenco MT, Woldeyohannes HO, Konarski JZ. Medical and substance-related comorbidity in bipolar disorder: translational research and treatment opportunities. Dialogues Clin Neurosci (2008) 10(2):203–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carrà G, Bartoli F, Crocamo C, Brady KT, Clerici M. Attempted suicide in people with co-occurring bipolar and substance use disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord (2014) 167:125–35. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon YH, Chen CM, Yi HY, Moss HB. Effect of comorbid alcohol and drug use disorders on premature death among unipolar and bipolar disorder decedents in the United States, 1999 to 2006. Compr Psychiatry (2011) 52(5):453–64. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uhl GR, Drgon T, Johnson C, Li CY, Contoreggi C, Hess J, et al. Molecular genetics of addiction and related heritable phenotypes: genome-wide association approaches identify “connectivity constellation” and drug target genes with pleiotropic effects. Ann N Y Acad Sci (2008) 1141:318–81 10.1196/annals.1441.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adida M, Jollant F, Clark L, Besnier N, Guillaume S, Kaladjian A, et al. Trait-related decision-making impairment in the three phases of bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry (2011) 70(4):357–65. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adinoff B, Rilling LM, Williams MJ, Schreffler E, Schepis TS, Rosvall T, et al. Impulsivity, neural deficits, and the addictions: the “oops” factor in relapse. J Addict Dis (2007) 26(Suppl 1):25–39. 10.1300/J069v26S01_04 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahn WY, Rass O, Fridberg DJ, Bishara AJ, Forsyth JK, Breier A, et al. Temporal discounting of rewards in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol (2011) 120(4):911–21 10.1037/a0023333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swann AC. The strong relationship between bipolar and substance-use disorder. Ann N Y Acad Sci (2010) 1187:276–93. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05146.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sterling P, Eyer J. Allostasis: a new paradigm to explain arousal pathology. In: Fisher S, Reason J, editors. Handbook of Life Stress, Cognition and Health. Chichester: John Wiley; (1988). p. 629–49. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McEwen BS. Stress, adaptation, and disease. Allostasis and allostatic load. Ann N Y Acad Sci (1998) 840:33–44. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McEwen BS. Allostasis and allostatic load: implications for neuropsychopharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology (2000) 22(2):108–24 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00129-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brietzke E, Mansur RB, Soczynska J, Powell AM, McIntyre RS. A theoretical framework informing research about the role of stress in the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry (2012) 39(1):1–8. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapczinski F, Vieta E, Andreazza AC, Frey BN, Gomes FA, Tramontina J, et al. Allostatic load in bipolar disorder: implications for pathophysiology and treatment. Neurosci Biobehav Rev (2008) 32(4):675–92. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grande I, Magalhães PV, Kunz M, Vieta E, Kapczinski F. Mediators of allostasis and systemic toxicity in bipolar disorder. Physiol Behav (2012) 106(1):46–50. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vieta E, Popovic D, Rosa AR, Solé B, Grande I, Frey BN, et al. The clinical implications of cognitive impairment and allostatic load in bipolar disorder. Eur Psychiatry (2013) 28(1):21–9. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2011.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Angelucci F, Ricci V, Gelfo F, Martinotti G, Brunetti M, Sepede G, et al. BDNF serum levels in subjects developing or not post-traumatic stress disorder after trauma exposure. Brain Cogn (2014) 84(1):118–22. 10.1016/j.bandc.2013.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kapczinski F, Frey BN, Kauer-Sant’Anna M, Grassi-Oliveira R. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and neuroplasticity in bipolar disorder. Expert Rev Neurother (2008) 8(7):1101–13. 10.1586/14737175.8.7.1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mandelli L, Mazza M, Martinotti G, Tavian D, Colombo E, Missaglia S, et al. Further evidence supporting the influence of brain-derived neurotrophic factor on the outcome of bipolar depression: independent effect of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and harm avoidance. J Psychopharmacol (2010) 24(12):1747–54. 10.1177/0269881109353463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berk M, Kapczinski F, Andreazza AC, Dean OM, Giorlando F, Maes M, et al. Pathways underlying neuroprogression in bipolar disorder: focus on inflammation, oxidative stress and neurotrophic factors. Neurosci Biobehav Rev (2011) 35(3):804–17. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grande I, Magalhães PV, Chendo I, Stertz L, Panizutti B, Colpo GD, et al. Staging systems in bipolar disorder: an International society for bipolar disorders task force report. Acta Psychiatr Scand (2014) 130(5):354–63. 10.1111/acps.12268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schulkin J. Allostasis: a neural behavioral perspective. Horm Behav (2003) 43(1):21–7 10.1016/S0018-506X(02)00035-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swaab DF, Bao AM, Lucassen PJ. The stress system in the human brain in depression and neurodegeneration. Ageing Res Rev (2005) 4(2):141–94. 10.1016/j.arr.2005.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andreazza AC, Kauer-Sant’anna M, Frey BN, Bond DJ, Kapczinski F, Young LT, et al. Oxidative stress markers in bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord (2008) 111(2–3):135–44. 10.1016/j.jad.2008.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steen NE, Methlie P, Lorentzen S, Hope S, Barrett EA, Larsson S, et al. Increased systemic cortisol metabolism in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a mechanism for increased stress vulnerability? J Clin Psychiatry (2011) 72(11):1515–21. 10.4088/JCP.10m06068yel [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steen NE, Methlie P, Lorentzen S, Dieset I, Aas M, Nerhus M, et al. Altered systemic cortisol metabolism in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia spectrum disorders. J Psychiatr Res (2014) 52:57–62. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daban C, Vieta E, Mackin P, Young AH. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am (2005) 28(2):469–80. 10.1016/j.psc.2005.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watson S, Gallagher P, Ritchie JC, Ferrier IN, Young AH. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in patients with bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry (2004) 184:496–502. 10.1192/bjp.184.6.496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McEwen BS. Structural plasticity of the adult brain: how animal models help us understand brain changes in depression and systemic disorders related to depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci (2004) 6(2):119–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McEwen BS. Central effects of stress hormones in health and disease: understanding the protective and damaging effects of stress and stress mediators. Eur J Pharmacol (2008) 583(2–3):174–85. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altman S, Haeri S, Cohen LJ, Ten A, Barron E, Galynker II, et al. Predictors of relapse in bipolar disorder: a review. J Psychiatr Pract (2006) 12(5):269–82. 10.1097/00131746-200609000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horesh N, Apter A, Zalsman G. Timing, quantity and quality of stressful life events in childhood and preceding the first episode of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord (2011) 134(1–3):434–7. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lai MC, Huang LT. Effects of early life stress on neuroendocrine and neurobehavior: mechanisms and implications. Pediatr Neonatol (2011) 52(3):122–9. 10.1016/j.pedneo.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baker LM, Williams LM, Korgaonkar MS, Cohen RA, Heaps JM, Paul RH. Impact of early vs. late childhood early life stress on brain morphometrics. Brain Imaging Behav (2013) 7(2):196–203. 10.1007/s11682-012-9215-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Linke J, King AV, Rietschel M, Strohmaier J, Hennerici M, Gass A, et al. Increased medial orbitofrontal and amygdala activation: evidence for a systems-level endophenotype of bipolar I disorder. Am J Psychiatry (2012) 169(3):316–25. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11050711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koob GF, Buck CL, Cohen A, Edwards S, Park PE, Schlosburg JE, et al. Addiction as a stress surfeit disorder. Neuropharmacology (2014) 76(Pt B):370–82 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.05.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koob GF, Le Moal M. Drug addiction, dysregulation of reward, and allostasis. Neuropsychopharmacology (2001) 24(2):97–129. 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00195-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koob GF. Addiction is a reward deficit and stress surfeit disorder. Front Psychiatry (2013) 4:72. 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.George O, Le Moal M, Koob GF. Allostasis and addiction: role of the dopamine and corticotropin-releasing factor systems. Physiol Behav (2012) 106(1):58–64. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koob G, Kreek MJ. Stress, dysregulation of drug reward pathways, and the transition to drug dependence. Am J Psychiatry (2007) 164(8):1149–59. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.05030503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pettorruso M, Martinotti G, Fasano A, Loria G, Di Nicola M, De Risio L, et al. Anhedonia in Parkinson’s disease patients with and without pathological gambling: a case-control study. Psychiatry Res (2014) 215(2):448–52. 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koob GF. Neurobiological substrates for the dark side of compulsivity in addiction. Neuropharmacology (2009) 56(Suppl 1):18–31. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gilpin NW. Brain reward and stress systems in addiction. Front Psychiatry (2014) 5:79. 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koob GF. A role for brain stress systems in addiction. Neuron (2008) 59(1):11–34 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koob GF, Le Moal M. Addiction and the brain antireward system. Annu Rev Psychol (2008) 59:29–53. 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koob GF. Hedonic homeostatic dysregulation as a driver of drug-seeking behavior. Drug Discov Today Dis Models (2008) 5(4):207–15. 10.1016/j.ddmod.2009.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koob GF. Neuroadaptive mechanisms of addiction: studies on the extended amygdala. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol (2003) 13(6):442–52. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2003.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koob GF. The role of CRF and CRF-related peptides in the dark side of addiction. Brain Res (2010) 1314:3–14. 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Martinotti G, Nicola MD, Reina D, Andreoli S, Focà F, Cunniff A, et al. Alcohol protracted withdrawal syndrome: the role of anhedonia. Subst Use Misuse (2008) 43(3–4):271–84. 10.1080/10826080701202429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Valdez GR, Koob GF. Allostasis and dysregulation of and neuropeptide Y systems: implications for the development of alcoholism. Pharmacol Biochem Behav (2004) 79(4):671–89. 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carmiol N, Peralta JM, Almasy L, Contreras J, Pacheco A, Escamilla MA, et al. Shared genetic factors influence risk for bipolar disorder and alcohol use disorders. Eur Psychiatry (2014) 29(5):282–7. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2013.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mandelli L, Mazza M, Marangoni C, Di Nicola M, Martinotti G, Tavian D, et al. Preliminary analysis of genes involved in inflammatory, oxidative processes and CA2+signaling in bipolar disorder and comorbidity for substance use disorder. Clin Neuropsychiatry (2011) 8(6):347–53. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Johnson C, Drgon T, McMahon FJ, Uhl GR. Convergent genome wide association results for bipolar disorder and substance dependence. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet (2009) 150B(2):182–90. 10.1002/ajmg.b.30900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Levey DF, Le-Niculescu H, Frank J, Ayalew M, Jain N, Kirlin B, et al. Genetic risk prediction and neurobiological understanding of alcoholism. Transl Psychiatry (2014) 4:e391. 10.1038/tp.2014.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patel SD, Le-Niculescu H, Koller DL, Green SD, Lahiri DK, McMahon FJ, et al. Coming to grips with complex disorders: genetic risk prediction in bipolar disorder using panels of genes identified through convergent functional genomics. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet (2010) 153B(4):850–77 10.1002/ajmg.b.31087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haldane M, Frangou S. New insights help define the pathophysiology of bipolar affective disorder: neuroimaging and neuropathology findings. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry (2004) 28(6):943–60. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wallis JD, Miller EK. Neuronal activity in primate dorsolateral and orbital prefrontal cortex during performance of a reward preference task. Eur J Neurosci (2003) 18(7):2069–81. 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02922.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Frangou S, Kington J, Raymont V, Shergill SS. Examining ventral and dorsal prefrontal function in bipolar disorder: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Eur Psychiatry (2008) 23(4):300–8. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jogia J, Dima D, Kumari V, Frangou S. Frontopolar cortical inefficiency may underpin reward and working memory dysfunction in bipolar disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry (2012) 13(8):605–15. 10.3109/15622975.2011.585662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Young JW, van Enkhuizen J, Winstanley CA, Geyer MA. Increased risk-taking behavior in dopamine transporter knockdown mice: further support for a mouse model of mania. J Psychopharmacol (2011) 25(7):934–43. 10.1177/0269881111400646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Camardese G, Di Giuda D, Di Nicola M, Cocciolillo F, Giordano A, Janiri L, et al. Imaging studies on dopamine transporter and depression: a review of literature and suggestions for future research. J Psychiatr Res (2014) 51:7–18. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Comings DE, Rosenthal RJ, Lesieur HR, Rugle LJ, Muhleman D, Chiu C, et al. A study of the dopamine D2 receptor gene in pathological gambling. Pharmacogenetics (1996) 6(3):223–34. 10.1097/00008571-199606000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.van Enkhuizen J, Geyer MA, Young JW. Differential effects of dopamine transporter inhibitors in the rodent Iowa gambling task: relevance to mania. Psychopharmacology (Berl) (2013) 225(3):661–74. 10.1007/s00213-012-2854-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.van Enkhuizen J, Henry BL, Minassian A, Perry W, Milienne-Petiot M, Higa KK, et al. Reduced dopamine transporter functioning induces high-reward risk-preference consistent with bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology (2014) 39(13):3112–22. 10.1038/npp.2014.170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Berk M, Dodd S, Kauer-Sant’anna M, Malhi GS, Bourin M, Kapczinski F, et al. Dopamine dysregulation syndrome: implications for a dopamine hypothesis of bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl (2007) 434:41–9. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01058.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cousins DA, Butts K, Young AH. The role of dopamine in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord (2009) 11(8):787–806. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00760.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Diana M. The dopamine hypothesis of drug addiction and its potential therapeutic value. Front Psychiatry (2011) 2:64. 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Der-Avakian A, Markou A. The neurobiology of anhedonia and other reward-related deficits. Trends Neurosci (2012) 35(1):68–77. 10.1016/j.tins.2011.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hatzigiakoumis DS, Martinotti G, Giannantonio MD, Janiri L. Anhedonia and substance dependence: clinical correlates and treatment options. Front Psychiatry (2011) 2:10. 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kirby LG, Zeeb FD, Winstanley CA. Contributions of serotonin in addiction vulnerability. Neuropharmacology (2011) 61(3):421–32 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Van den Oever MC, Spijker S, Smit AB. The synaptic pathology of drug addiction. Adv Exp Med Biol (2012) 970:469–91 10.1007/978-3-7091-0932-8_21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pettorruso M, De Risio L, Martinotti G, Di Nicola M, Ruggeri F, Conte G, et al. Targeting the glutamatergic system to treat pathological gambling: current evidence and future perspectives. Biomed Res Int (2014) 2014:109786. 10.1155/2014/109786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pettorruso M, Martinotti G, Di Nicola M, Onofrj M, Di Giannantonio M, Conte G, et al. Amantadine in the treatment of pathological gambling: a case report. Front Psychiatry (2012) 3:102. 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Di Nicola M, De Risio L, Battaglia C, Camardese G, Tedeschi D, Mazza M, et al. Reduced hedonic capacity in euthymic bipolar subjects: a trait-like feature? J Affect Disord (2013) 147(1–3):446–50. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McIntyre RS, McElroy SL, Konarski JZ, Soczynska JK, Bottas A, Castel S, et al. Substance use disorders and overweight/obesity in bipolar I disorder: preliminary evidence for competing addictions. J Clin Psychiatry (2007) 68(9):1352–7. 10.4088/JCP.v68n0905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ibanez A, Cetkovich M, Petroni A, Urquina H, Baez S, Gonzalez-Gadea ML, et al. The neural basis of decision-making and reward processing in adults with euthymic bipolar disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). PLoS One (2012) 7(5):e37306. 10.1371/journal.pone.0037306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Strakowski SM, Fleck DE, DelBello MP, Adler CM, Shear PK, Kotwal R, et al. Impulsivity across the course of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord (2010) 12(3):285–97. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00806.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pizzagalli DA, Goetz E, Ostacher M, Iosifescu DV, Perlis RH. Euthymic patients with bipolar disorder show decreased reward learning in a probabilistic reward task. Biol Psychiatry (2008) 64(2):162–8. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chandler RA, Wakeley J, Goodwin GM, Rogers RD. Altered risk-aversion and risk-seeking behavior in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry (2009) 66(9):840–6. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mason L, O’Sullivan N, Blackburn M, Bentall R, El-Deredy W. I want it now! neural correlates of hypersensitivity to immediate reward in hypomania. Biol Psychiatry (2012) 71(6):530–7. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bizzarri JV, Sbrana A, Rucci P, Ravani L, Massei GJ, Gonnelli C, et al. The spectrum of substance abuse in bipolar disorder: reasons for use, sensation seeking and substance sensitivity. Bipolar Disord (2007) 9(3):213–20. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00383.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Edge MD, Miller CJ, Muhtadie L, Johnson SL, Carver CS, Marquinez N, et al. People with bipolar I disorder report avoiding rewarding activities and dampening positive emotion. J Affect Disord (2013) 146(3):407–13. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.07.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nusslock R, Almeida JR, Forbes EE, Versace A, Frank E, Labarbara EJ, et al. Waiting to win: elevated striatal and orbitofrontal cortical activity during reward anticipation in euthymic bipolar disorder adults. Bipolar Disord (2012) 14(3):249–60. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.01012.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Linke J, Sonnekes C, Wessa M. Sensitivity to positive and negative feedback in euthymic patients with bipolar I disorder: the last episode makes the difference. Bipolar Disord (2011) 13(7–8):638–50. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00956.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yechiam E, Hayden EP, Bodkins M, O’Donnell BF, Hetrick WP. Decision making in bipolar disorder: a cognitive modeling approach. Psychiatry Res (2008) 161(2):142–52. 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Pizzagalli DA. Depression, stress, and anhedonia: toward a synthesis and integrated model. Annu Rev Clin Psychol (2014) 10:393–423. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sinha R. Chronic stress, drug use, and vulnerability to addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci (2008) 1141:105–30. 10.1196/annals.1441.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lovallo WR. Cortisol secretion patterns in addiction and addiction risk. Int J Psychophysiol (2006) 59(3):195–202. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lijffijt M, Hu K, Swann AC. Stress modulates illness-course of substance use disorders: a translational review. Front Psychiatry (2014) 5:83. 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Levy YZ, Levy DJ, Barto AG, Meyer JS. A computational hypothesis for allostasis: delineation of substance dependence, conventional therapies, and alternative treatments. Front Psychiatry (2013) 4:167. 10.3389/fpsyt.2013.00167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Post RM, Kalivas P. Bipolar disorder and substance misuse: pathological and therapeutic implications of their comorbidity and cross-sensitisation. Br J Psychiatry (2013) 202(3):172–6. 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.116855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Azorin JM, Bellivier F, Kaladjian A, Adida M, Belzeaux R, Fakra E, et al. Characteristics and profiles of bipolar I patients according to age-at-onset: findings from an admixture analysis. J Affect Disord (2013) 150(3):993–1000. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pope MA, Joober R, Malla AK. Diagnostic stability of first-episode psychotic disorders and persistence of comorbid psychiatric disorders over 1 year. Can J Psychiatry (2013) 58(10):588–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Goldstein BI, Strober M, Axelson D, Goldstein TR, Gill MK, Hower H, et al. Predictors of first-onset substance use disorders during the prospective course of bipolar spectrum disorders in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry (2013) 52(10):1026–37. 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kenneson A, Funderburk JS, Maisto SA. Risk factors for secondary substance use disorders in people with childhood and adolescent-onset bipolar disorder: opportunities for prevention. Compr Psychiatry (2013) 54(5):439–46. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Duffy A, Horrocks J, Milin R, Doucette S, Persson G, Grof P. Adolescent substance use disorder during the early stages of bipolar disorder: a prospective high-risk study. J Affect Disord (2012) 142(1–3):57–64. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Do EK, Mezuk B. Comorbidity between hypomania and substance use disorders. J Affect Disord (2013) 150(3):974–80. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Prisciandaro JJ, DeSantis SM, Chiuzan C, Brown DG, Brady KT, Tolliver BK. Impact of depressive symptoms on future alcohol use in patients with co-occurring bipolar disorder and alcohol dependence: a prospective analysis in an 8-week randomized controlled trial of acamprosate. Alcohol Clin Exp Res (2012) 36(3):490–6 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01645.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Saddichha S, Prakash R, Sinha BN, Khess CR. Perceived reasons for and consequences of substance abuse among patients with psychosis. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry (2010) 12(5):e1–7. 10.4088/PCC.09m00926gry [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pettersen H, Ruud T, Ravndal E, Landheim A. Walking the fine line: self-reported reasons for substance use in persons with severe mental illness. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being (2013) 8:21968. 10.3402/qhw.v8i0.21968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rømer Thomsen K, Callesen MB, Linnet J, Kringelbach ML, Møller A. Severity of gambling is associated with severity of depressive symptoms in pathological gamblers. Behav Pharmacol (2009) 20(5–6):527–36. 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283305e7a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. Am J Psychiatry (1985) 142(11):1259–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Robinson LJ, Thompson JM, Gallagher P, Goswami U, Young AH, Ferrier IN, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive deficits in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord (2006) 93(1–3):105–15. 10.1016/j.jad.2006.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Bally N, Zullino D, Aubry JM. Cannabis use and first manic episode. J Affect Disord (2014) 165:103–8. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lev-Ran S, Le Foll B, McKenzie K, George TP, Rehm J. Bipolar disorder and co-occurring cannabis use disorders: characteristics, co-morbidities and clinical correlates. Psychiatry Res (2013) 209(3):459–65. 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Baigent M. Managing patients with dual diagnosis in psychiatric practice. Curr Opin Psychiatry (2012) 25(3):201–5. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283523d3d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Di Nicola M, Sala L, Romo L, Catalano V, Even C, Dubertret C, et al. Adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in major depressed and bipolar subjects: role of personality traits and clinical implications. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci (2014) 264(5):391–400. 10.1007/s00406-013-0456-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Perugi G, Ceraudo G, Vannucchi G, Rizzato S, Toni C, Dell’Osso L. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in Italian bipolar adult patients: a preliminary report. J Affect Disord (2013) 149(1–3):430–4. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sala R, Goldstein BI, Wang S, Blanco C. Childhood maltreatment and the course of bipolar disorders among adults: epidemiologic evidence of dose-response effects. J Affect Disord (2014) 165:74–80. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jones SH, Barrowclough C, Allott R, Day C, Earnshaw P, Wilson I. Integrated motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioural therapy for bipolar disorder with comorbid substance use. Clin Psychol Psychother (2011) 18(5):426–37. 10.1002/cpp.783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gaudiano BA, Weinstock LM, Miller IW. Improving treatment adherence in patients with bipolar disorder and substance abuse: rationale and initial development of a novel psychosocial approach. J Psychiatr Pract (2011) 17(1):5–20. 10.1097/01.pra.0000393840.18099.d6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Horsfall J, Cleary M, Hunt GE, Walter G. Psychosocial treatments for people with co-occurring severe mental illnesses and substance use disorders (dual diagnosis): a review of empirical evidence. Harv Rev Psychiatry (2009) 17(1):24–34. 10.1080/10673220902724599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Murru A, Pacchiarotti I, Amann BL, Nivoli AM, Vieta E, Colom F. Treatment adherence in bipolar I and schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. J Affect Disord (2013) 151(3):1003–8. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Juster RP, McEwen BS, Lupien SJ. Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev (2010) 35(1):2–16. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Goldstein BI, Bukstein OG. Comorbid substance use disorders among youth with bipolar disorder: opportunities for early identification and prevention. J Clin Psychiatry (2010) 71(3):348–58. 10.4088/JCP.09r05222gry [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Langas AM, Malt UF, Opjordsmoen S. Independent versus substance-induced major depressive disorders in first-admission patients with substance use disorders: an exploratory study. J Affect Disord (2013) 144(3):279–83. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Quello SB, Brady KT, Sonne SC. Mood disorders and substance use disorder: a complex comorbidity. Sci Pract Perspect (2005) 3(1):13–21 10.1151/spp053113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Li CS, Sinha R. Inhibitory control and emotional stress regulation: neuroimaging evidence for frontal-limbic dysfunction in psycho-stimulant addiction. Neurosci Biobehav Rev (2008) 32(3):581–97. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kenneson A, Funderburk JS, Maisto SA. Substance use disorders increase the odds of subsequent mood disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend (2013) 133(2):338–43. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Pettinati HM, O’Brien CP, Dundon WD. Current status of co-occurring mood and substance use disorders: a new therapeutic target. Am J Psychiatry (2013) 170(1):23–30. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12010112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Marchese G, Scheggi S, Secci ME, De Montis MG, Gambarana C. Anti-anhedonic activity of long-term lithium treatment in rats exposed to repeated unavoidable stress. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol (2013) 16(7):1611–21. 10.1017/S1461145712001654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Orsetti M, Canonico PL, Dellarole A, Colella L, Di Brisco F, Ghi P. Quetiapine prevents anhedonia induced by acute or chronic stress. Neuropsychopharmacology (2007) 32(8):1783–90 10.1038/sj.npp.1301291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Marston HM, Martin FD, Papp M, Gold L, Wong EH, Shahid M. Attenuation of chronic mild stress-induced ‘anhedonia’ by asenapine is not associated with a ‘hedonic’ profile in intracranial self-stimulation. J Psychopharmacol (2011) 25(10):1388–98. 10.1177/0269881110376684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Mazza M, Squillacioti MR, Pecora RD, Janiri L, Bria P. Effect of aripiprazole on self-reported anhedonia in bipolar depressed patients. Psychiatry Res (2009) 165(1–2):193–6. 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Martinotti G, Andreoli S, Di Nicola M, Di Giannantonio M, Sarchiapone M, Janiri L. Quetiapine decreases alcohol consumption, craving, and psychiatric symptoms in dually diagnosed alcoholics. Hum Psychopharmacol (2008) 23(5):417–24. 10.1002/hup.944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Prisciandaro JJ, Brown DG, Brady KT, Tolliver BK. Comorbid anxiety disorders and baseline medication regimens predict clinical outcomes in individuals with co-occurring bipolar disorder and alcohol dependence: results of a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Res (2011) 188(3):361–5. 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.04.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Di Nicola M, Martinotti G, Mazza M, Tedeschi D, Pozzi G, Janiri L. Quetiapine as add-on treatment for bipolar I disorder with comorbid compulsive buying and physical exercise addiction. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry (2010) 34(4):713–4 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Janiri L, Martinotti G, Di Nicola M. Aripiprazole for relapse prevention and craving in alcohol-dependent subjects: results from a pilot study. J Clin Psychopharmacol (2007) 27(5):519–20 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318150c841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Di Nicola M, De Risio L, Pettorruso M, Caselli G, De Crescenzo F, Swierkosz-Lenart K, et al. Bipolar disorder and gambling disorder comorbidity: current evidence and implications for pharmacological treatment. J Affect Disord (2014) 167:285–98. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Beaulieu S, Saury S, Sareen J, Tremblay J, Schütz CG, McIntyre RS, et al. The canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) task force recommendations for the management of patients with mood disorders and comorbid substance use disorders. Ann Clin Psychiatry (2012) 24(1):38–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Sani G, Kotzalidis GD, Vöhringer P, Pucci D, Simonetti A, Manfredi G, et al. Effectiveness of short-term olanzapine in patients with bipolar I disorder, with or without comorbidity with substance use disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol (2013) 33(2):231–5. 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318287019c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Machado-Vieira R, Ibrahim L, Henter ID, Zarate CA, Jr. Novel glutamatergic agents for major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. Pharmacol Biochem Behav (2012) 100(4):678–87. 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Olive MF, Cleva RM, Kalivas PW, Malcolm RJ. Glutamatergic medications for the treatment of drug and behavioral addictions. Pharmacol Biochem Behav (2012) 100(4):801–10. 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]