Abstract

Difficulty inhibiting context-inappropriate behavior is a common deficit in psychotic disorders. The diagnostic specificity of this impairment, its familiality, and its degree of independence from the generalized cognitive deficit associated with psychotic disorders remain to be clarified. Schizophrenia, schizoaffective and bipolar patients with history of psychosis (n=523), their available first-degree biological relatives (n=656), and healthy participants (n=223) from the multi-site B-SNIP study completed a manual Stop Signal task. A nonlinear mixed model was used to fit logistic curves to success rates on Stop trials as a function of parametrically varied Stop Signal Delay. While schizophrenia patients had greater generalized cognitive deficit than bipolar patients, their deficits were similar on the Stop Signal task. Further, only bipolar patients showed impaired inhibitory control relative to healthy individuals after controlling for generalized cognitive deficit. Deficits accounted for by the generalized deficit were seen in relatives of schizophrenia and schizoaffective patients, but not in relatives of bipolar patients. In clinically stable patients with psychotic bipolar disorder, impaired inhibitory behavioral control was a specific cognitive impairment, distinct from the generalized neuropsychological impairment associated with psychotic disorders. Thus, in bipolar disorder with psychosis, a deficit in inhibitory control may contribute to risk for impulsive behavior. Because the deficit was not familial in bipolar families and showed a lack of independence from the generalized cognitive deficit in schizophrenia spectrum disorders, it appears to be a trait related to illness processes rather than one tracking familial risk factors.

Keywords: response inhibition, schizophrenia, psychotic bipolar disorder, family study, stop signal

1. Introduction

Stop Signal paradigms examine the interplay between response activation, triggered by internal plans or orienting toward salient stimuli, and inhibition processes, triggered by top-down control from goal-maintenance networks to stop prepotent responses. They are widely used to assess inhibitory behavioral control (Bissett & Logan, 2011; Logan, 1994; Logan et al., 1984). Participants respond as quickly as possible to Go cues; however, some Go cues are followed after a brief delay (Stop Signal Delay, SSD) by a Stop cue instructing subjects to inhibit their response. Difficulty inhibiting cued Go responses increases with longer delays, putatively because increasing SSD has the effect of delaying initiation of inhibitory processes relative to onset of response activation processes (Logan et al., 1984). Inhibitory control impairments are of clinical interest because of potential relations to substance abuse, impulsive behavior and suicide, particularly in bipolar disorder where disinhibited behavior is a defining characteristic.

Meta-analyses on inhibitory control deficits in schizophrenia (Sitskoorn, et al., 2004) and bipolar disorder (Bora, et al., 2009) and their first-degree relatives, mainly using the Stroop task (Kravariti et al., 2009; Levy & Weiss, 2010; Stroop, 1935; Westerhausen et al., 2011; Besnier et al., 2009), suggest that schizophrenia patients may show milder inhibitory deficits than bipolar patients. In contrast, in the antisaccade task of inhibitory control, greater deficits have been observed in schizophrenia than bipolar disorder (Blackwood, 1996; Martin et al., 2007; Harris et al., 2009; Reilly et al., 2013). Relative to other tasks, the SST does not depend on semantic associations as in the Stroop paradigm, or require simultaneous response suppression and initiation demands as in the antisaccade task, so it is a potentially more direct approach for assessing inhibitory processes that has not yet been used in larger sample studies contrasting psychotic disorders.

Schizophrenia and bipolar patients, especially bipolar with psychosis, typically have generalized cognitive impairments as well as impaired inhibitory control (Bora, et al., 2010; Harvey, et al. 2010; Hill et al., 2013). Generalized neuropsychological deficits are typically greater in schizophrenia than bipolar disorder, with schizoaffective patients showing intermediate deficits (Hill et al., 2013; Woolard et al., 2010). It is unknown whether inhibitory deficits represent a specific cognitive deficit or one manifestation of generalized cognitive deficit across these disorders. Specific deficits can provide independent information for clinical evaluation, tracking treatment outcomes, and gene discovery. Moreover, there is interest in assessing inhibitory control deficits in relatives and whether they are familial endophenotypes (Allen et al., 2009; Christodoulou, et al., 2012; Ferrier, et al., 2004; Giakoumaki et al., 2011).

Stop Signal tasks can assess strategic adjustments made to enhance inhibitory control. Healthy individuals strategically delay reaction times to Go cues, allowing time for inhibitory processes if a Stop cue occurs (Verbruggen & Logan, 2008). Evidence supports reduced strategic latency adjustments in schizophrenia (Vink et al., 2006) but strategic slowing relative to a baseline control task has not been evaluated in psychotic patients (Bissett & Logan, 2011; Verbruggen & Logan, 2008).

We used a SST to evaluate behavioral response inhibition in a large sample of psychotic patients and their first-degree relatives. Familiality and degree of deficit not accounted for by general neuropsychological deficit were examined. We hypothesized that inhibitory control deficits would be distinct from generalized cognitive deficit and familial in psychotic bipolar patients.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

As part of the Bipolar and Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes (B-SNIP), participants were recruited at six sites: University of Chicago/University of Illinois-Chicago (Chicago, Illinois), Yale University/Institute of Living (Hartford, Connecticut), University of Texas Southwestern (Dallas, Texas), University of Maryland (Baltimore, Maryland), Wayne State University (Detroit, Michigan) and Beth Israel Deaconness Medical Center, Harvard University (Boston, Massachusetts). Primary groups were 214 schizophrenia patients (SZ) and 173 bipolar patients with history of psychosis (BPP), their available first-degree relatives (schizophrenia relatives n=224, SZrel; bipolar psychosis relatives n=194, BPrel), and healthy participants (n=223; HP). Patients with schizoaffective disorder depressed-type (n=45; SZA-D) and their first-degree relatives (n=44; SZA-Drel), and patients with schizoaffective disorder bipolar-type (n=91; SZA-BP) and their first-degree relatives (n=105; SZA-BPrel) were also examined (Tamminga et al., 2013 for full cohort description). All participants provided written informed consent. This study was approved by Institutional Review Boards at each site.

All subjects were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV diagnosis (First, 1997) and the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS) (Keefe et al., 2004) to index generalized neuropsychological deficit. BACS subtest deficit patterns were similar across patient groups in the B-SNIP sample (Hill et al., 2013), so total score was used in analyses. Exclusion criteria included: significant neurological or systemic medical illness, head trauma with >10 minutes unconsciousness, positive urine drug screen on testing day, and substance abuse within 3 months or dependence within 6 months.

2.1.1 Patients

Because acute illness may disrupt inhibitory control in bipolar disorder (Strakowski et al., 2010) and schizophrenia (Harris et al., 2006; Hill et al., 2009), patients were clinically stable and on consistent psychopharmacological treatment for at least one month. Symptom severity and functioning were rated using the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (Lancon et al., 2000), Young Mania Rating Scale (Young et al., 2000), Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (Montgomery & Asberg, 1979), Birchwood Social Functioning Scale (Birchwood et al., 1990), Schizo-bipolar Scale (Keshavan et al., 2011) and Barratt Impulsiveness Scale 11 (Patton et al., 1995). All but 37 patients were taking psychotropic medications (Table 1). Dosing of antipsychotic medication was standardized across drugs following Andreasen et al., (2010).

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Data for Each Patient and Relative Group.

| Patients | Healthy Participants (HP) | Schizophrenia (SZ) | Bipolar Psychosis (BPP) | Schizoaffective Depressed (SZA-D) | Schizoaffective Bipolar (SZA-BP) | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| n=223 | n=214 | n=173 | n=45 | n=91 | ||

| Age in years Mean (SD) | 38 (13) | 35 (13) | 36 (13) | 38 (11) | 36 (13) | F=1.87 ns |

| Sex: Male | 42% | 66% | 33% | 49% | 33% | χ2=16.05† a |

| Female | 58% | 34% | 66% | 51% | 66% | |

| Education (years) | 15 (3) | 13 (2) | 14 (2) | 12 (2) | 13 (2) | F=27.99§ b |

| WRAT-III Reading Standard Score | 103 (14) | 95 (16) | 102 (14) | 93 (16) | 100 (15) | F=12.58§ c |

| Clinical Variables | ||||||

| PANSS Total | 63 (17) | 53 (14) | 67 (18) | 68(16) | F=25.44§ d | |

| PANSS Pos | 16 (6) | 12 (4) | 17 (6) | 18 (5) | F=31.19§ e | |

| PANSS Neg | 16 (6) | 12 (4) | 16 (5) | 15 (5) | F=21.87§ f | |

| YMRS | 8 (6) | 7 (6) | 8 (6) | 9 (6) | F=2.46ns | |

| MADRS | 10 (8) | 12 (9) | 16 (9) | 15 (10) | F=9.48§ g | |

| Medication Class | ||||||

| Antipsychotic | 86% | 67% | 82% | 79% | ||

| Mood stabilizer | 13% | 45% | 31% | 51% | ||

| Lithium | 5% | 28% | 7% | 9% | ||

| Antidepressant | 39% | 43% | 49% | 52% | ||

| Sedative/anxiolytic | 17% | 22% | 13% | 27% | ||

| Stimulant | 4% | 6% | 0% | 5% | ||

| Anticholinergic | 14% | 6% | 9% | 10% | ||

|

| ||||||

| Relatives | Healthy Participants (HP) | Relatives of Schizophrenia (R-SZ) | Relatives of Bipolar Psychosis (R-BP) | Relatives of Schizoaffective Depressed (R-SZA-D) | Relatives of Schizoaffective Bipolar (R-SZA-BP) | Findings |

|

| ||||||

| n=223 | n=224 | n=194 | n=44 | n=105 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Age (years) | 38 (13) | 43 (15) | 40 (16) | 39 (16) | 40 (17) | F=3.57†,h |

| Sex: Male | 42% | 31% | 35% | 29% | 32% | χ2=2.96 |

| Female | 58% | 69% | 65% | 71% | 68% | |

| Education (years) | 15 (3) | 14 (3) | 15 (3) | 14 (3) | 14 (3) | F=4.48†i |

| WRAT-III Reading Standard Score | 103 (14) | 98 (15) | 104 (14) | 97 (16) | 102 (15) | F=7.89§j |

| Cluster A Diagnosis | 20% | 10% | 15% | 14% | ||

| Cluster B Diagnosis | 6% | 8% | 12% | 12% | ||

Note. PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; WRAT-III: Wide Range Achievement Test – Third Edition; YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale; MADRS: Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale

SZ: Higher proportion of males

HC > BPP > SZ, SZA-D, SZA-BP

HP, SZA-BP > SZ, SZA-D; BPP > SZ,SZA-D

BPP < SZ, SZA-D, SZA-BP; SZ < SZA-BP

BPP < SZ, SZA-D < SZA-BP

BPP < SZ, SZA-D, SZA-BP

SZA-BP, SZA-D > BPP > SZ

HP < R-SZ

HP > R-SZ, R-SZA-D, R-SZA-BP; R-BP > R-SZ, R-SZA-BP

R-SZ, R-SZA-D < HP, R-SZA-BP R-BP

p < .05

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .001

2.1.2 Relatives

Personality traits in first-degree relatives were assessed using the Structured Interview for DSM-IV Personality (Pfohol et al., 1997). Individuals within one criterion of diagnostic threshold for a Cluster A (psychosis spectrum) or Cluster B (emotional lability) DSM-IV Axis II disorder were identified as in our prior studies (Hill et al., 2013; Reilly et al., 2013). Relatives were not excluded for Axis I diagnoses, although for group comparisons, relatives with lifetime history of psychosis (N=64) were excluded from statistical modeling to characterize risk without confounding illness-related factors. All relatives were included in familiality estimates and clinical correlations to maintain representation of all population variation.

2.1.3 Healthy Comparison Sample

Healthy participants were excluded for lifetime psychotic or bipolar disorder or recurrent depression, or family history of psychotic or bipolar disorder in first-degree relatives.

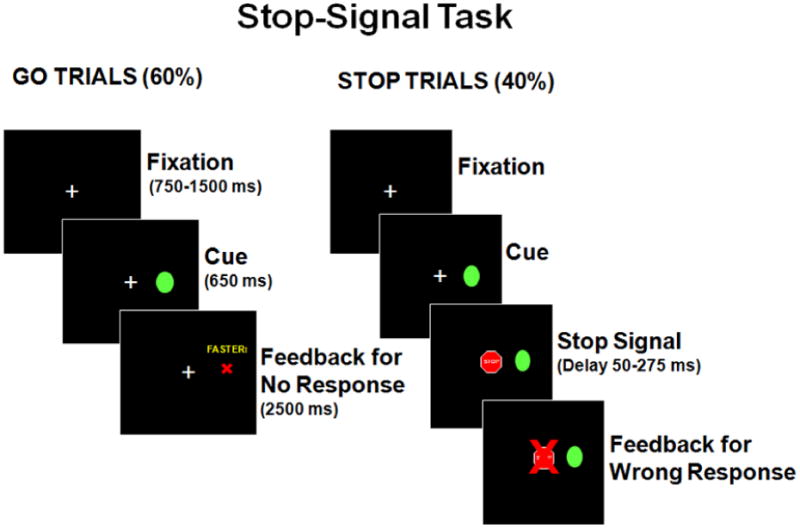

2.2 Procedure

All trials began with presentation of a white central-fixation crosshair (1.5 degrees in size) for a random interval between 750-1500 ms. On Go trials, a green circle (Go cue, 1.75 degrees in size) appeared 12 degrees right or left of center for 650 ms. On Stop trials, a Stop Signal (red stop sign; 1.75 degrees in size) was presented at central-fixation (Figure 1) at variable delays (SSD) after the Go stimulus appeared. Participants responded as quickly and accurately as possible by pressing a left or right button for stimuli appearing on the left or right side of the screen, respectively. Responses were recorded using a button box sampling at 125 Hz. Equipment and procedures were identical across testing sites.

Figure 1.

Stop Signal task parameters. In Go trials, participants pressed the corresponding left or right button when a green circle appeared to the right or left of center. During Stop trials, they were to refrain from pushing the buttons. When participants did not respond within 650 ms on Go trials, a red ‘X’ and the word ‘faster’ were presented for 2500ms indicating that the participant failed a trial. On Stop trials in which the participants pressed a button, a red ‘X’ appeared over the stop sign to provide performance feedback indicating the failure to inhibit a response.

Participants first performed practice trials to verify comprehension of task instructions. Then, a baseline task of 50 consecutive Go trials was given, followed by the SST with four blocks of pseudorandomly interleaved Go and Stop trials (40% Stop). SSD were blocked into fourteen 16.6ms intervals (reflecting 60 Hz monitor refresh rate) between 50-282 ms to model group performance differences across a range of SSDs from relatively easy to very difficult to stop responses. To maintain a prepotent Go response tendency, lack of response within 650 ms on Go trials resulted in trial termination with a red ‘X’ and the word “faster”. For every third Go trial without a timely response, a Go trial was added later. A red ‘X’ over the stop sign gave performance feedback for incorrect Stop trials.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

A nonlinear mixed model implemented with PROC NLMIXED in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) was used to fit logistic curves, modeling success rate on Stop trials as a function of SSD interval for each group (the inhibition function). Two fixed-effects parameters of the logistic function were b1, the SSD interval at which a group's success rate equaled 50% (higher b1 equates to better performance), and b2, the maximum change in success rate. Our primary focus was group differences in b1. Approximate omnibus F tests were used to contrast maximum likelihood estimates of b1 between groups, including age and sex as covariates if significant. False Discovery Rate controlled for multiple comparisons (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995). Two SZ participants were dropped from analyses for excessive lack of responding (>60% non-response to Go cues). To assess independence of SST performance from generalized cognitive deficit, models were re-run including BACS total score as a covariate. Extreme b1 values were derived in a small number of cases who were removed from group comparisons (N=8).

Strategic slowing of response latencies was analyzed by comparing increases in Go trial response latency from baseline (100% Go) to SST trials (60% Go) across participant groups in a repeated measures ANOVA. Analyses were then rerun covarying for BACS scores.

Stop signal reaction time (SSRT) has been used in several prior SST studies. SSRT analyses are included in supplementary materials, with findings similar to our primary results. We preferred our nonlinear modeling approach for primary analyses because we had a wide range of SSDs to parametrically model SSD effects, and did not want to presuppose that models of task parameter effects would be similar across groups.

2.4 Clinical Correlations

Clinical correlations were examined with b1, reaction time difference between the baseline task and SST (strategic slowing), and SSRT using Spearman's rho. These correlations were conducted for exploratory/descriptive purposes and are presented without correction for multiple comparisons.

2.5 Familiality

Familiality for b1, strategic slowing and SSRT was computed for the two primary patients groups (SZ and BPP) using Sequential Oligogenic Linkage Analysis Routines (SOLAR) (Almasy & Blangero, 1998). Because the input variable for parameter b1 was non-normally distributed, model maximization was adjusted using tdist in SOLAR.

3. Results

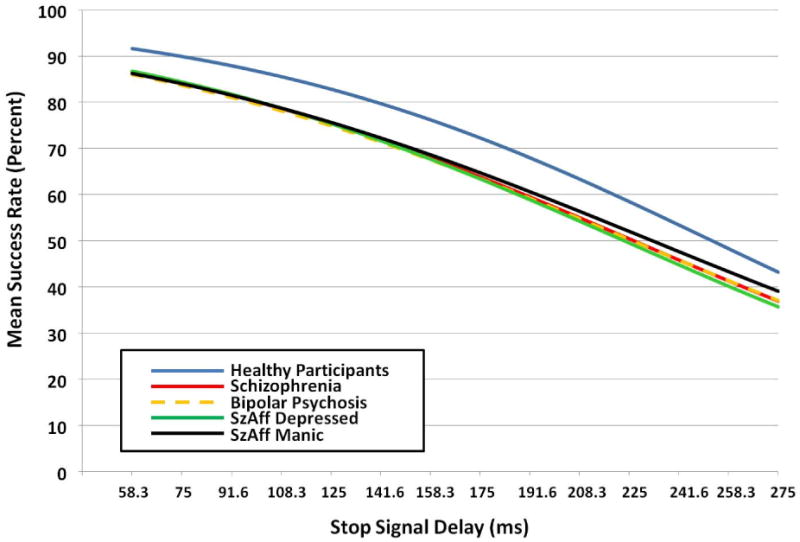

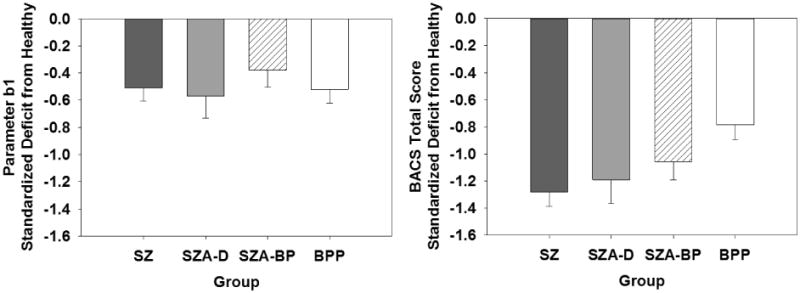

An omnibus test on parameter b1 revealed significant differences among patient and HP groups F(4,1311) = 9.99, p<0001 (Figure 2). All patient groups performed significantly worse than HP (unadjusted p's <002, FDR-adjusted p's < .01). Patient groups did not differ significantly from each other (unadjusted p's > .30). This contrasts with significant group differences in BACS performance, where SZ showed more deficit than SZA-BP, t(288) = 2.49, FDR-adjusted p=03) and BPP, t(368) = 5.23, FDR-adjusted p=.006), and SZA-D showed more deficit than BPP t(208) = 2.35, FDR-adjusted p=04) as reported previously (Hill et al., 2013).

Figure 2.

Nonlinear mixed model curves for patient groups and healthy participants, without the inclusion of the BACS covariate. Values for Stop Signal Delay on the X axis represent median Stop Signal delays for each of 14 time bins.

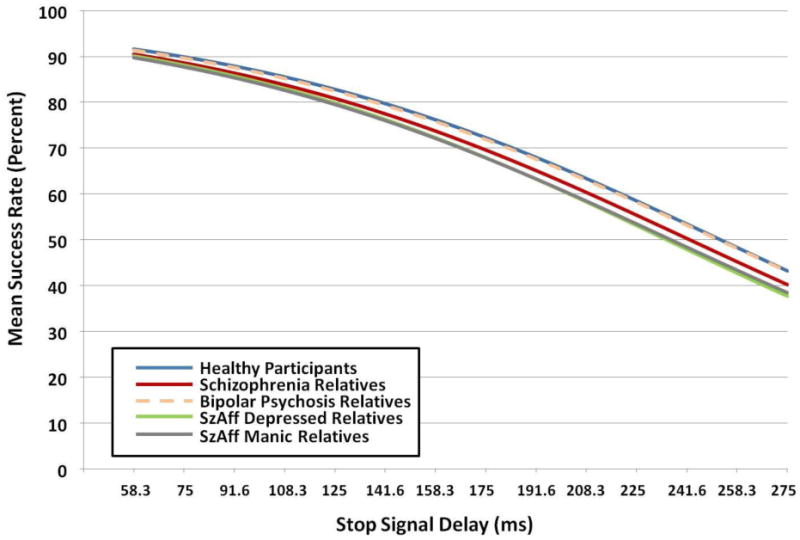

First-degree relatives without history of psychosis and HP also differed significantly on parameter b1, F(4, 1311) = 3.10, p=015 (Figure 3). This was driven by trend and significant differences in relative groups compared to HP: SZrel (raw p=.04, FDR-adjusted p=.11), SZA-Drel (raw p=.05, FDR-adjusted p=.11), and SZA-BPrel (raw p=.01, FDR-adjusted p=04). Performance of BPPrel was virtually indistinguishable from HP (raw p=90). There were no effects of age, sex or testing site for patients or relatives.

Figure 3.

Nonlinear mixed model curves for relative groups and healthy participants, without the inclusion of the BACS covariate. Values for Stop Signal Delay on the X axis represent median Stop Signal delays for each of 14 time bins.

3.1 Relation to Generalized Cognitive Deficit

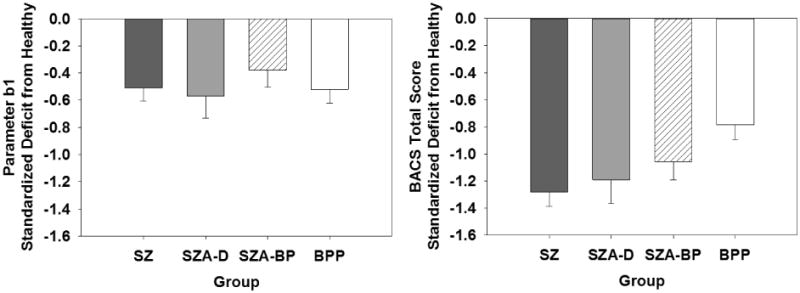

Covarying for BACS scores eliminated all group differences except between BPP and HP (FDR–adjusted p=02) (Table 2).Thus, in SZ and SZA, impaired performance on the SST represented a component of generalized deficit (Figure 4), while in BPP deficits in inhibitory control were independent from generalized deficit. Deficits in all relative groups were eliminated after controlling for BACS scores.

Table 2. Effect Sizes for pair-wise comparisons on Stop Signal task performance (Parameter b1) without and with (in parentheses) correction for generalized neuropsychological deficit (BACS score).

| Patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HP | SZ | SZA-D | SZA-BP | |

| SZ | .51 +/-.19* (.20 +/-.19) | - | - | - |

| SZA-D | .57+/-.32* (.31+/-.33) | .06 +/-.32 (.09+/-.33) | - | - |

| SZA-BP | .38+/-.25* (.21+/-.25) | .12+/-.25 (.01+/-.25) | .18+/-.36 (.09+/-.37) | - |

| BPP | .52+/-.20* (.34+/-.19)* | .01+/-.20 (.12+/-.21) | .05+/-.33 (.03+/-.34) | .12+/-.25 (.12+/-.26) |

| Relatives | ||||

| HP | SZrel | SZA-Drel | SZA-BPrel | |

| SZrel | .19+/-.18 (.10+/-.19) | - | - | - |

| SZA-Drel | .33+/-.32 (.23+/-.33) | .14+/-.32 (.13+/-.33) | - | - |

| SZA-BPrel | .31+/-.23* (.27+/-.24) | .11+/-.23 (.17+/-.24) | .03+/-.35 (.04+/-.36) | - |

| BPPrel | .01+/-.19 (.01+/-.19) | .18+/-.19 (.11+/-.19) | .32+/-.33 (.24+/-.34) | .29+/-.24 (.28+/-.24) |

Note. Effect sizes (Hedges'g) for pair-wise comparisons without BACS (Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia) as a covariate, and in parentheses, with the addition of BACS scores as a covariate in the model. 95% confidence intervals were calculated with a standard distribution. HP=healthy participants; SZ=schizophrenia; SZA-D=schizoaffective depressed type; SZA-BP schizoaffective bipolar type; BPP=bipolar disorder with history of psychosis

p<.05 FDR corrected for multiple comparisons

Figure 4.

Comparison of standardized relative deficit (Hedges' g) in parameter b1 (the Stop Signal Delay yielding a 50% error rate) in the SST (left plot) versus general cognitive deficit as measured by the BACS (right plot). All patient groups show significant deficit relative to healthy participants for both SST parameter b1 and BACS, but while SST b1 does not differ across patient groups, BACS deficits decrease across the spectrum of nonaffective and affective psychotic disorders from SZ to BPP.

3.2 Strategic Response Slowing

For strategic slowing, a significant task by group interaction F(4,734)=9.99, p<001 was observed. In the baseline task, HP had significantly faster Go latencies than SZ, t(430)=4.41, FDR-adjusted p=.008) and SZA-BP, t(308)=2.34, FDR-adjusted p=05). During the SST, HP had significantly longer Go latencies than SZA-D, t(264)=2.53, FDR-adjusted p=04) and SZA-BP, t(308)=2.41, FDR-adjusted p=05). All patient groups showed significantly less slowing relative to baseline than HP (FDR-adjusted p's<02) (Figure 5). After covarying for BACS scores, reduced strategic slowing was no longer significant in any patient group. No relative group differed from HP on baseline or SST task latencies, nor was there a task by group interaction.

Figure 5.

Strategic slowing. Slowing of Go trial latencies by group, showing that all patient groups had significantly less strategic slowing during the SST relative to the baseline Go task than did healthy participants. HP: Healthy; SZ: Schizophrenia; SZA-D: Schizoaffective depressed type; SZA-BP: Schizoaffective bipolar type; BPP: Bipolar psychosis, * p<.05. all differences from BPP, ** p<.01, all differences from healthy participants

3.3. Correlations

Performance parameter b1 significantly correlated with strategic slowing in all groups except SZA-D (Spearman's rho range .32 to .51, p's<01, SZA-D rho=.11), demonstrating the performance benefit of strategic slowing. In BPP patients only, Parameter b1 correlated with Birchwood total score (rho=.16, p=04) and reduced strategic slowing correlated with Barratt Motor Impulsiveness scores (rho=-.16, p=04) (Supplementary Table S1). There was no significant correlation between b1 or strategic slowing and antipsychotic dose, clinical state-of-illness ratings or history of substance abuse/dependence. Across all patients, Schizo-Bipolar Scale scores correlated modestly with strategic slowing (rho=-.09, p=03), but not with b1. Relatives with Cluster A or B personality traits did not differ from HP in b1 or strategic slowing.

3.4 Familiality

Parameter b1 was not familial in SZ (h2=.14, p=.16) or BPP (h2=08, p=29), nor was strategic slowing in SZ (h2=.15, p=10) or BPP (h2=0, p=50).

4. Discussion

This study yielded three main findings: 1) in contrast to robust and differential generalized cognitive deficit across psychotic disorders, patients groups were equally impaired in SST performance; 2) SST performance was primarily a manifestation of generalized cognitive deficit in schizophrenia spectrum disorders, while in BPP inhibitory behavioral control impairments appeared to represent a specific cognitive deficit; and 3) first-degree relatives of SZ and BPP did not demonstrate specific impairments on the SST and familiality/heritability estimates were not significant, so the SST did not appear promising as a cognitive endophenotype for psychotic disorders. Test performance was unrelated to history of substance use, current psychopharmacological treatment, and most clinical ratings in the clinically stable patients or their relatives. Thus they appear to be trait-like deficits.

4.1 Effects in Patients

Stop Signal deficit was similar across patient groups while generalized cognitive deficit (BACS scores) was much more pronounced in SZ/SZA than BPP, indicating greater deficit in inhibitory behavioral control relative to other cognitive deficits in BPP. It should be noted however that effect sizes for generalized cognitive deficit were much greater than SST deficit for all patient groups. Only in BPP was the behavioral control deficit independent from the generalized deficit. In most neuropsychological abilities, the profile of cognitive deficits in BPP is similar to that in schizophrenia spectrum disorders, only less severe (Hill et al., 2013). Thus, observations with the SST are novel in showing a specific difference in cognitive profile for BPP compared to schizophrenia. This pattern in performance accuracy was not seen for strategic slowing, where generalized cognitive deficit accounted for the reduced ability to delay responding in all patient groups. Because the BACS does not have a subtest dependent on behavioral inhibition, elimination of significant patient vs. healthy differences on SST performance in SZ and SZA after controlling for BACS scores is particularly noteworthy.

Consistent with past findings (Shakow, 1977), patients had slower baseline response latencies than HP. Patients also showed reduced proactive slowing of Go trial responses from baseline to SST. Reduced slowing may have contributed to patients' poorer performance on Stop trials as greater slowing was related to higher performance accuracy on Stop trials. Similar results have been found in SZ using an oculomotor SST (Thakkar et al., 2011).

In addition to the apparently specific inhibitory control deficit in BPP, it is noteworthy that clinical correlations with social adjustment and impulsive behavior were significant only in BPP. A reduced ability to utilize top-down strategic processes together with reduced inhibitory control may contribute to clinical problems of behavioral impulsivity in BPP. This abnormality may be a useful target for clinical trials, as it is believed to be most abnormal during acute illness (Strakowski et al., 2010).

4.2 Effects in First-degree Relatives

After correction for generalized cognitive impairment, no relative group showed a performance deficit. Similar to Vink et al. (2006), all first-degree relatives showed normal response latencies during baseline and SST. Previous studies demonstrated substantial and familial cognitive impairments in first-degree relatives of patients with psychosis (Becker et al., 2008; Bora et al., 2009; Dickinson et al., 2011; Gur et al., 2007; Hill et al., 2013; Zalla et al., 2004). Our findings suggest less deficit in relatives and familiality of inhibitory behavioral control assessed by SST than in other cognitive domains. Thus, our findings suggest that SST performance is not a promising endophenotype for psychotic disorders.

4.3 Limitations and Conclusions

As with most large-scale studies of stable patients with history of psychosis, patients were treated with psychiatric medications. Although antipsychotic dose and anticonvulsant medication were not related to performance measures, their potential impact cannot be fully excluded. Second, while the SSD range was large, some patients failed the easiest trials and others could perform the most difficult trials. While reasonable performance models were derived for almost all subjects, future studies might benefit from an extended range of SSDs. Third, the degree to which deficits in BPP extend to bipolar patients with no history of psychosis is unknown. Nonpsychotic bipolar patients may show an even greater dissociation between inhibitory control and general cognitive deficit as they have less generalized cognitive impairment (Glahn et al., 2007).

The results of the present study indicate that inhibitory behavioral control deficits in BPP are of particular interest because of their independence from generalized cognitive deficit and their potential clinical relevance. These deficits may represent a promising treatment target in BPP (Pavuluri et al., 2010).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part by NIMH grants MH078113, MH077945, MH077852, MH077851, MH077862, MH072767, and MH083888. We thank Dr. Gunvant Thaker for his input and collaboration on this project.

Role of the Funding Source. This research was funded in part by NIMH grants MH078113, MH077945, MH077852, MH077851, MH077862, MH072767, and MH083888. The NIMH had no further role in development of the paradigm or interpretation of experimental findings.

Footnotes

Contributions. LEE and MS contributed to data analysis and manuscript preparation. PAN contributed statistical design and analyses. JLR, SKH, RSEK, ESG, GDP, CAT, and MSK contributed to study design, data collection and interpretation. JAS contributed to study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, and manuscript preparation. All authors have seen and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest. Author RSEK currently or in the past has received investigator-initiated research funding support from the Allon, AstraZeneca, Department of Veteran's Affair, Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, GlaxoSmithKline, National Institute of Mental Health, Novartis, Psychogenics, Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene, Inc., and the Singapore National Medical Research Council. He currently or in the past has received honoraria, served as a consultant, or advisory board member for Abbott, Abbvie, Akebia, Amgen, Astellas, Asubio, BiolineRx, Biomarin, Boehringer-Ingelheim, BrainCells, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CHDI, Eli Lilly, EnVivo, Helicon, Lundbeck, Memory Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Mitsubishi, NeuroSearch, Novartis, Orion, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, Shire, Solvay, Sunovion, Takeda, Targacept, and Wyeth. RSEK also receives royalties from the BACS testing battery and the MATRICS Battery (BACS Symbol Coding). He is also a shareholder in NeuroCog Trials, Inc. Author GDP- consulted for Bristol-Myers Squibb. Author CAT discloses the following financial interests and associations: Intracellular Therapies (ITI, Inc.) - Advisory Board, drug development; PureTech Ventures- Ad Hoc Consultant; Eli Lilly Pharmaceuticles – Ad Hoc Consultant; Sunovion – Ad Hoc Consultant; Astellas – Ad Hoc Consultant; Merck – Ad Hoc Consultant; International Congress on Schizophrenia Research - Organizer; Unpaid volunteer; NAMI – Council Member; Unpaid Volunteer; American Psychiatric Association - Deputy Editor; Finnegan Henderson Farabow Garrett & Dunner, LLP – Expert Witness. Author MSK has received a grant from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals Inc. Author JAS has served as a consultant for Takeda, Inc., Eli Lilly Pharmaceuticals, BMS, and Roche and has received grant funding from Janssen, Inc. The remaining authors (LEE, MS, PAN, JLR, SKH, ESG) report no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen AJ, Griss ME, Folley BS, Hawkins KA, Pearlson GD. Endophenotypes in schizophrenia: a selective review. Schizophr Res. 2009;109(1-3):24–37. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almasy L, Blangero J. Multipoint quantitative-trait linkage analysis in general pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62(5):1198–1211. doi: 10.1086/301844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Pressler M, Nopoulos P, Miller D, Ho BC. Antipsychotic dose equivalents and dose-years: a standardized method for comparing exposure to different drugs. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker TM, Kerns JG, Macdonald AW, 3rd, Carter CS. Prefrontal dysfunction in first-degree relatives of schizophrenia patients during a Stroop task. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(11):2619–2625. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: a Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1995;57(B):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Besnier N, Richard F, Zendjidjian X, Kaladjian A, Mazzola-Pomietto P, Adida M, Azorin JM. Stroop and emotional Stroop interference in unaffected relatives of patients with schizophrenic and bipolar disorders: distinct markers of vulnerability? World J Biol Psychiatry. 2009;10(4 Pt 3):809–818. doi: 10.1080/15622970903131589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchwood M, Smith J, Cochrane R, Wetton S, Copestake S. The Social Functioning Scale. The development and validation of a new scale of social adjustment for use in family intervention programmes with schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:853–859. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.6.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissett PG, Logan GD. Balancing cognitive demands: control adjustments in the stop-signal paradigm. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2011;37(2):392–404. doi: 10.1037/a0021800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwood DH, Sharp CW, Walker MT, Doody GA, Glabus MF, Muir WJ. Implications of comorbidity for genetic studies of bipolar disorder: P300 and eye tracking as biological markers for illness. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1996 Jun;(30):85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Yucel M, Pantelis C. Cognitive endophenotypes of bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis of neuropsychological deficits in euthymic patients and their first-degree relatives. J Affect Disord. 2009;113(1-2):1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Yucel M, Pantelis C. Neurocognitive markers of psychosis in bipolar disorder: a meta-analytic study. J Affect Disord. 2010;127(1-3):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.02.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou T, Messinis L, Papathanasopoulos P, Frangou S. Dissociable and common deficits in inhibitory control in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(2):125–130. doi: 10.1007/s00406-011-0213-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson D, Goldberg TE, Gold JM, Elvevag B, Weinberger DR. Cognitive factor structure and invariance in people with schizophrenia, their unaffected siblings, and controls. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(6):1157–1167. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrier IN, Chowdhury R, Thompson JM, Watson S, Young AH. Neurocognitive function in unaffected first-degree relatives of patients with bipolar disorder: a preliminary report. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6(4):319–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV–Clinical Version (SCID-CV) American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Giakoumaki SG, Roussos P, Pallis EG, Bitsios P. Sustained attention and working memory deficits follow a familial pattern in schizophrenia. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2011;26(7):687–695. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acr060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gur RE, Nimgaonkar VL, Almasy L, Calkins ME, Ragland JD, Pogue-Geile MF, Kanes S, Blangero J, Gur RC. Neurocognitive endophenotypes in a multiplex multigenerational family study of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(5):813–819. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.5.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MS, Reilly JL, Keshavan MS, Sweeney JA. Longitudinal studies of antisaccades in antipsychotic-naive first-episode schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2006;36(4):485–494. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705006756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris MS, Reilly JL, Thase ME, Keshavan MS, Sweeney JA. Response suppression deficits in treatment-naive first-episode patients with schizophrenia, psychotic bipolar disorder and psychotic major depression. Psychiatry Res. 2009;170(2-3):150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey PD, Wingo AP, Burdick KE, Baldessarini RJ. Cognition and disability in bipolar disorder: lessons from schizophrenia research. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(4):364–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SK, Reilly JL, Harris MS, Rosen C, Marvin RW, Deleon O, Sweeney JA. A comparison of neuropsychological dysfunction in first-episode psychosis patients with unipolar depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2009;113(2-3):167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SK, Reilly JL, Keefe RS, Gold JM, Bishop JR, Gershon ES, Tamminga CA, Pearlson GD, Keshavan MS, Sweeney JA. Neuropsychological Impairments in Schizophrenia and Psychotic Bipolar Disorder: Findings from the Bipolar and Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes (B-SNIP) Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12101298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe RS, Goldberg TE, Harvey PD, Gold JM, Poe MP, Coughenour L. The Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia: reliability, sensitivity, and comparison with a standard neurocognitive battery. Schizophr Res. 2004;68(2-3):283–297. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavan MS, Morris DW, Sweeney JA, Pearlson G, Thaker G, Seidman LJ, Eack SM, Tamminga C. A dimensional approach to the psychosis spectrum between bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: the Schizo-bipolar Scale. Schizophr Res. 2011;133(1-3):250–254. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravariti E, Schulze K, Kane F, Kalidindi S, Bramon E, Walshe M, Marshall N, Hall MH, Georgiades A, McDonald C, Murray RM. Stroop-test interference in bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(3):285–286. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.052639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancon C, Auquier P, Nayt G, Reine G. Stability of the five-factor structure of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) Schizophr Res. 2000;42(3):231–9. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy B, Weiss RD. Neurocognitive impairment and psychosis in bipolar I disorder during early remission from an acute episode of mood disturbance. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(2):201–206. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04663yel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan GD. On the ability to inhibit thought and action: A users' guide to the stop signal paradigm. In: Carr DDTH, editor. Inhibitory processes in attention, memory, and language. San Diego: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 189–239. [Google Scholar]

- Logan GD, Cowan WB, Davis KA. On the ability to inhibit simple and choice reaction time responses: a model and a method. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 1984;10(2):276–291. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.10.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LF, Hall MH, Ross RG, Zerbe G, Freedman R, Olincy A. Physiology of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(12):1900–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06010017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psychol. 1995;51(6):768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavuluri MN, Passarotti AM, Harral EM, Sweeney JA. Enhanced prefrontal function with pharacotherapy on a response inhibiton task in adolescent bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(11):1526–1534. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05504yel. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfohl B, Blum N, Zimmerman M. Structured Interview for DSMIV Personality: SIDP-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly JL, Frankovich K, Hill SK, Gershon ES, Keefe RSE, Keshavan MS, Pearlson G, Tamminga CA, Sweeney JA. Elevated antisaccade error rate as an intermediate phenotype for psychosis across diagnostic categories. Schiz Bull. 2013 Sep 13; doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt132. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakow D. Psychological deficit in schizophrenia. Psychol Issues. 1977;10(2):96–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitskoorn MM, Aleman A, Ebisch SJ, Appels MC, Kahn RS. Cognitive deficits in relatives of patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2004;71(2-3):285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strakowski SM, Fleck DE, DelBello MP, Adler CM, Shear PK, Kotwal R, Arndt S. Impulsivity across the course of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(3):285–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroop JR. Studies of Interference in Serial Verbal Reactions. J Exp Psych. 1935;18:643–662. [Google Scholar]

- Tamminga CA, Ivleva E, Keshavan M, Pearlson G, Clementz B, Witte B, Morris DW, Bishop J, Thaker GK, Sweeney JA. Clinical Phenotypes of Psychosis in the Bipolar and Schizophrenia Network on Intermediate Phenotypes(B-SNIP) Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(11):1263–1274. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12101339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar KN, Schall JD, Boucher L, Logan GD, Park S. Response inhibition and response monitoring in a saccadic countermanding task in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69(1):55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbruggen F, Logan GD. Response inhibition in the stop-signal paradigm. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12(11):418–424. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vink M, Ramsey NF, Raemaekers M, Kahn RS. Striatal dysfunction in schizophrenia and unaffected relatives. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(1):32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerhausen R, Kompus K, Hugdahl K. Impaired cognitive inhibition in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of the Stroop interference effect. Schizophr Res. 2011;133(1-3):172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolard AA, Kose S, Woodward ND, Verbruggen F, Logan GD, Heckers S. Intact associative learning in patients with schizophrenia: evidence from a Go/NoGo paradigm. Schizophr Res. 2010;122(1-3):131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.02.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zalla T, Joyce C, Szoke A, Schurhoff F, Pillon B, Komano O, Perez-Diaz F, Bellivier F, Alter C, Dubois B, Rouillon F, Houde O, Leboyer M. Executive dysfunctions as potential markers of familial vulnerability to bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2004;121(3):207–217. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(03)00252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.