Abstract

Germ cells of sexually reproducing organisms receive an array of cues from somatic tissues that instruct developmental processes. Although the nature of these signals differs amongst organisms, the importance of germline-soma interactions is a common theme. Recently, peptide hormones from the nervous system have been shown to regulate germ cell development in the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea; thus, we sought to investigate a second class of hormones with a conserved role in reproduction, the lipophilic hormones. In order to study these signals, we identified a set of putative lipophilic hormone receptors, known as nuclear hormone receptors, and analyzed their functions in reproductive development. We found one gene, nhr-1, belonging to a small class of functionally uncharacterized lophotrochozoan-specific receptors, to be essential for the development of differentiated germ cells. Upon nhr-1 knockdown, germ cells in the testes and ovaries fail to mature, and remain as undifferentiated germline stem cells. Further analysis revealed that nhr-1 mRNA is expressed in the accessory reproductive organs and is required for their development, suggesting that this transcription factor functions cell non-autonomously in regulating germ cell development. Our studies identify a role for nuclear hormone receptors in planarian reproductive maturation and reinforce the significance of germline-soma interactions in sexual reproduction across metazoans.

Keywords: Nuclear hormone receptor, Germ cell, Accessory reproductive organ, Lophotrochozoa, Planaria

INTRODUCTION

Maturation and maintenance of germ cells in sexually reproducing animals requires a sophisticated network of systemic cues. In mammals, it has been appreciated for decades that long-range endocrine signals influence germ cells (Neill, 2006); however, the roles of these cues in invertebrate reproductive development have only recently begun to be characterized. The planarian Schmidtea mediterranea has become an excellent model for studying reproductive biology due to its dynamic germline regulation and developmental plasticity (Newmark et al., 2008). Classic experiments have shown that planarians possess the ability to regenerate a complete germline from fragments of adult worms devoid of reproductive tissues, suggesting that germ cells are specified from somatic stem cells (Morgan, 1902). Furthermore, planarians can resorb or regenerate their reproductive organs in response to physiological cues, including nutrient status (Miller and Newmark, 2012), injury (Wang et al., 2007), overall body size, and temperature (Curtis, 1902). This dynamic regulation ensures that reproductive development commences under optimal conditions and must involve communication between a number of organ systems.

Several lines of evidence indicate that signals between somatic tissues and the germline are key for the development of the planarian reproductive system. For example, the neurally derived peptide hormone NPY-8 controls germ cell differentiation and the development of accessory reproductive organs (Collins et al., 2010). Additionally, the planarian homologue of a conserved sex determination factor, dmd-1, is expressed in somatic niche cells of the testes as well as male accessory reproductive organs, and is required for specification, development, and maintenance of male germ cells (Chong et al., 2013). Conversely, signals from the germ cells are also required for the development of accessory reproductive structures. Knockdown of nanos, a key regulator of germ cell development that is expressed in male and female germline stem cells (GSCs)(Handberg-Thorsager and Salo, 2007; Sato et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007)), results in the loss of germ cells and subsequently accessory reproductive organs (Wang et al., 2007). Collectively, these results indicate that long-range signals between the germline and soma are important in planarian reproductive development; however, the identities of most of the signals being sent and received remain unknown.

Nuclear hormone receptors (NHRs) are ligand-binding transcription factors that regulate a diverse array of developmental and physiological processes in metazoans, with sexual development being among the most renowned. In mammals, androgen (Wang et al., 2009), progesterone (Chappell et al., 1997), and estrogen receptors (Walker and Korach, 2004) all have well-established roles in both male and female sex organ development and reproductive functions. Recent studies have shown that endocrine regulation of reproduction by NHRs is not limited to mammals. For example, studies in Drosophila melanogaster females have revealed the steroid hormone, ecdysone, that is structurally similar to mammalian sex steroids, and the ecdysone receptor (EcR) are required for the maintenance and proliferation of GSCs (Ables and Drummond-Barbosa, 2010) as well as the progression of egg chambers beyond mid-oogenesis (Buszczak et al., 1999; Carney and Bender, 2000). Also in Drosophila females, the orphan NHR Hr39 is essential for development of the spermathecae and parovaria glands that produce secretions required for sperm storage and ovulation, respectively (Allen and Spradling, 2008; Sun and Spradling, 2013). Within its massive collection of 284 NHRs, C. elegans requires a subset of receptors for reproduction, including nhr-6 for spermathecal development, proper female germ cell morphology, and ovulation (Gissendanner et al., 2008); nhr-25 for somatic gonad and vulva development (Asahina et al., 2000); nhr-67 for vulva development; and nhr-85 for egg laying (Gissendanner et al., 2004). Even the rotifer, Brachionus manjavacas, an ancient lophotrochozoan, contains a conserved progesterone receptor necessary for reproduction (Stout et al., 2010). Thus, lipophilic hormones and their receptors have critical roles in the reproductive potential of sexual organisms; however, this subject remains unexplored in planarians.

Here, we exploit the functional genomic tools available for S. mediterranea to characterize the planarian NHR complement. By comparing NHR expression between sexually and asexually reproducing worms we identified a novel two DNA-binding domain hormone receptor, nhr-1, that is required for the development of differentiated germ cells in the testes and ovaries, as well as accessory reproductive organs. Interestingly, this gene is detected exclusively in male and female accessory reproductive organs, suggesting that soma-germline interactions mediated by lipophilic hormones promote sexual maturity in the planarian.

Materials and Methods

Planarian culture

Sexual planarians were maintained in 0.75X Montjuïc salts at 18°C (Cebria and Newmark, 2005). Asexual planarians were maintained in a 1X solution of Instant Ocean Sea Salts at 20°C. Both strains were fed pureed calf liver weekly or once every two weeks. Animals were starved at least one week before all experiments.

Gene identification and cloning

NHR sequences were identified by comparing conserved sequences from other metazoans, such as M. musculus, D. melanogaster, C. elegans, and S. mansoni, to planarian transcriptomic and genomic data. NHR sequence data were retrieved from UniProtKB and compared to S. mediterranea transcriptomic (Rouhana et al., 2012) http://planmine.mpi-cbg.de/planmine/begin.do (Rink, manuscript in preparation) and genomic data (Robb et al., 2008) using BLAST with an e-value of ≤1e-10. Sequences for all predicted NHRs were confirmed by PCR amplification and DNA sequencing. Primer sequences for PCR experiments are listed in Table S2. These genes were each TA cloned in pJC53.2 as described previously (Collins et al., 2010). To compare planarian NHR sequences to those of other organisms, individual DNA-binding and ligand-binding domain sequences were obtained using the Pfam database. NCBI BLASTP was used to infer similarity with previously described NHRs in other organisms of interest. Protein sequences were then aligned using Lasergene MegAlign software with ClustalW analysis.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Relative quantities of each planarian NHR transcript were examined in the sexual vs. asexual strains by extracting RNA from three individuals of each strain using TriZol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). DNase treatment and reverse transcription (iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) were performed to generate cDNAs for each sample. Quantitative PCR was performed using GoTaq 10X PCR Master Mix (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and an Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus real-time PCR system. Each of the three biological replicates was analyzed in triplicate and an expression level of each NHR was normalized to levels of β-tubulin. Primer sequences for qPCR experiments are listed in Table S2.

Riboprobe synthesis and in situ hybridization

For sexual and asexual animals, in situ hybridizations were carried out as previously described (King and Newmark, 2013) with the following modifications. Planarians were killed in 10% N-acetyl cysteine for 10 minutes, fixed in formaldehyde for one hour at room temperature, and permeabilized for one hour in 5 μg/ml proteinase K. Samples were imaged as previously described (Collins et al., 2010).

RNA Interference

Synthesis of dsRNA for nhr-1 and control RNAi treatments was performed as described previously (Collins et al., 2010). For RNAi experiments, juvenile animals were fed 5 μg dsRNA in 45 μL 3:1 liver:water mix once every four days for 8 feedings. Up to six worms were used per sample. Animals were then starved one week before further analyses. Under these feeding conditions all immature worms fed control dsRNA reached sexual maturity based on their size and the presence of a gonopore. The nhr-1(RNAi) phenotype was scored by manually counting the number of regressed versus normal testes lobes and ovaries visualized using DAPI labeling and fluorescence microscopy.

RESULTS

Nuclear hormone receptors are expressed differentially between sexually and asexually reproducing planarians

To investigate potential roles of lipophilic hormone signaling in planarian sexual development, we identified and characterized NHRs in the planarian S. mediterranea. Structurally, NHRs possess two distinct domains: a zinc finger DNA-binding domain and a lipophilic ligand-binding domain. These domains are highly conserved and can be used to identify genes within the superfamily. In comparing known NHR sequences from other metazoan species to planarian transcriptomic data, we generated a list of 23 putative planarian NHRs (Table S1). Although two of these receptors have been studied previously (i.e., planarian homologues of the hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 (Wagner et al., 2011) and the tailless/TLX-1 genes (Raska et al., 2011)) most are uncharacterized in planarians. Among these are genes sharing similarity with the vertebrate retinoid X receptor, thyroid hormone receptor, and COUP transcription factor (Table S1).

With this gene set in hand, we took advantage of the two reproductively distinct strains of S. mediterranea to compare the expression profiles of individual planarian NHR genes. The sexually reproducing strain exists as cross-fertilizing hermaphrodites and possesses both male and female gonads as well as a set of accessory reproductive organs. The asexually reproducing strain undergoes transverse fission and is devoid of accessory reproductive organs, but possesses rudimentary gonads (Chong et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2007). We hypothesized that NHR genes expressed at higher levels in sexual planarians might have important roles in controlling the development of the reproductive system; thus, we analyzed the expression levels of each NHR gene in sexual vs. asexual planarians by quantitative PCR. From these studies, we identified four genes that were expressed at significantly higher levels with a fold change greater than 2 (p < 0.01) in sexual planarians (Table S1).

The nuclear hormone receptor, nhr-1, belongs to a unique class of receptors containing two DNA-binding domains

Based on our qPCR experiments, we focused on nhr-1 because it was expressed more than 20 times higher in sexual planarians and belonged to a unique class of NHRs with unknown function. In contrast to most NHRs that possess a single DNA-binding domain, nhr-1 encodes a predicted protein containing a pair of adjacent DNA-binding motifs followed by a single ligand-binding domain (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, this unique NHR domain structure is found in three other planarian proteins, nhr-2, nhr-3, and nhr-6, (Table S1) and in orthologous proteins found in other Lophotrochozoans, including mollusks and parasitic flatworms (Wu et al., 2007). Previously, a similar NHR with two DNA-binding domains was predicted from the genome of the Ecdysozoan Daphnia pulex (Wu et al., 2007). However, closer analysis of more recent sets of genomic data failed to confirm the presence of this gene in the assembled Daphnia pulex genome (Colbourne et al., 2011) or in available transcriptomic data. Since proteins with similar domain structures were not found in other Ecdysozoan or Deuterostome genomes (Wu et al., 2007), it is likely this family of receptors is unique to Lophotrochozoans.

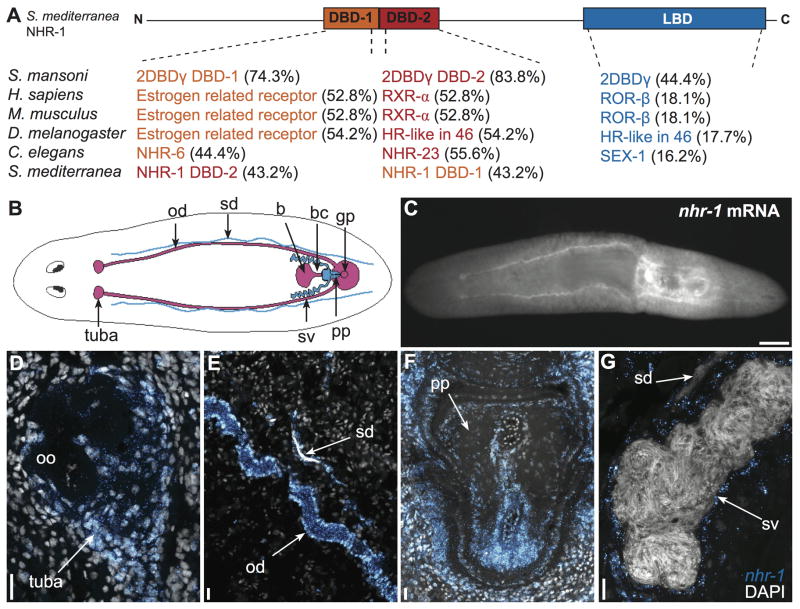

Fig. 1. nhr-1 is a two DNA-binding domain nuclear hormone receptor that is expressed in accessory reproductive tissues.

(A) Comparison of individual nhr-1 domains to homologues in other organisms with percent identities. Accession numbers are provided in Table S3.

(B) Cartoon depicting the accessory reproductive organs in sexual planarians including oviducts (od), sperm ducts (sd), tuba, bursa (b), bursal canal (bc), gonopore (gp), seminal vesicles (sv), and penis papilla (pp). (C) Whole mount fluorescence in situ hybridization detecting nhr-1 mRNA in the accessory reproductive organs. Ventral view is shown. (D–G) Maximum intensity projections of confocal Z-stacks of tuba (D), single confocal sections of sperm duct and oviduct (E), penis papilla (F), and seminal vesicle (G) containing nhr-1 mRNA. nhr-1 signal is colored orange and DAPI colored blue. Scale bars: (C) 500 μm. (D–G) 20 μm.

Consistent with previous studies, sequence analysis of the individual NHR-1 DNA-binding domains indicates that they share more similarity with DNA-binding domains from other organisms than to one another (Fig. 1A)(Wu et al., 2007). In particular, the individual DNA-binding domains of NHR-1 were closely related to the cognate domains from an orthologous protein of unknown function from the human parasitic flatworm Schistosoma mansoni (Fig. 1A).

nhr-1 mRNA is expressed in male and female accessory reproductive organs

To visualize nhr-1 mRNA expression in S. mediterranea, we performed whole-mount and fluorescence in situ hybridization experiments on sexual and asexual planarians. Consistent with our qPCR results, we did not detect nhr-1 above background levels in asexual worms, and observed nhr-1 expression in the accessory reproductive tissues of sexual planarians. Specifically, expression was observed in the tuba (the sperm storage organ just below the ovaries in the anterior region of the worm), oviducts, sperm ducts, copulatory bursa, seminal vesicles, and penis papilla (Fig. 1C–G). We did not detect nhr-1 mRNA in male or female gonads.

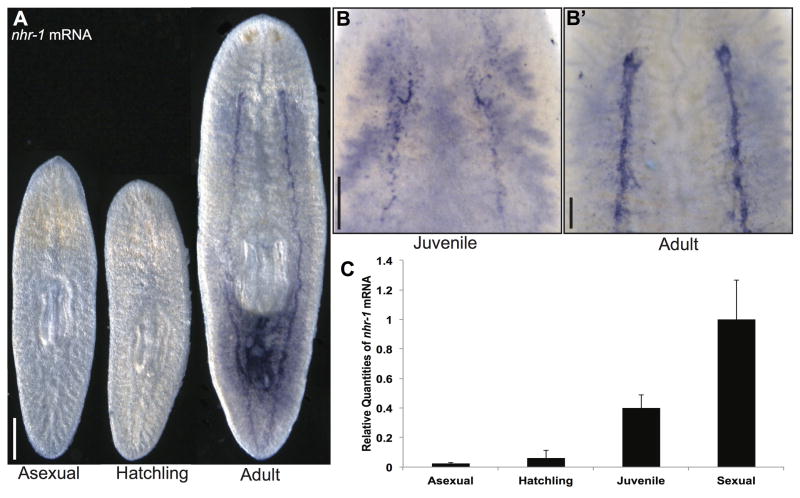

Further analyses of nhr-1 expression during development were performed in sexual worms shortly after hatching from the egg capsule and during juvenile stages of sexual development (Fig. 2A–C). Consistent with our observations in asexual and mature sexual worms, we observed no expression of nhr-1 in newly hatched planarians that lack reproductive tissues (Fig. 2A). However, during the process of sexual maturation in juvenile worms, we observed varying levels of nhr-1 expression depending on the stage of development. In many cases, we observed nhr-1-positive cells coalescing in the regions where the mature organs will be formed in the adult planarian (Fig. 2B and B′). Occasionally, we detected weak signal in the intestine; however, this signal was not affected following nhr-1 RNAi treatment, indicating this intestinal signal is non-specific. Interestingly, an nhr-1 paralog containing two DNA-binding domains, nhr-2, was also expressed at higher levels in sexual planarians (Figure S1A). In situ hybridization detected nhr-2 expression in the cells of the penis papilla (Figure S1B).

Fig. 2. nhr-1 expression increases with sexual maturation.

(A) Whole-mount, colorimetric in situ hybridization of nhr-1 on asexual, newly hatched sexual, and adult sexual worms. Ventral view shown for all animals. (B–B′) Whole-mount, colorimetric in situ hybridization on juvenile sexual and adult sexual worms to detect nhr-1+ cells in anterior ventral areas. (C) Quantitative PCR showing nhr-1 expression levels at different stages of sexual maturity. Three biological replicates were analyzed for the sexual, asexual, and newly hatched stages. Six biological replicates were analyzed for the juvenile stage due to their variability in sexual maturation. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals. mRNA levels for asexual, hatchling, and juvenile worms are normalized to sexual worms, all differences are statistically significant (p < 0.01, t-test). Scale bars: (A) 500 μm. (B, B′) 200 μm.

nhr-1 is required for the development of accessory reproductive organs

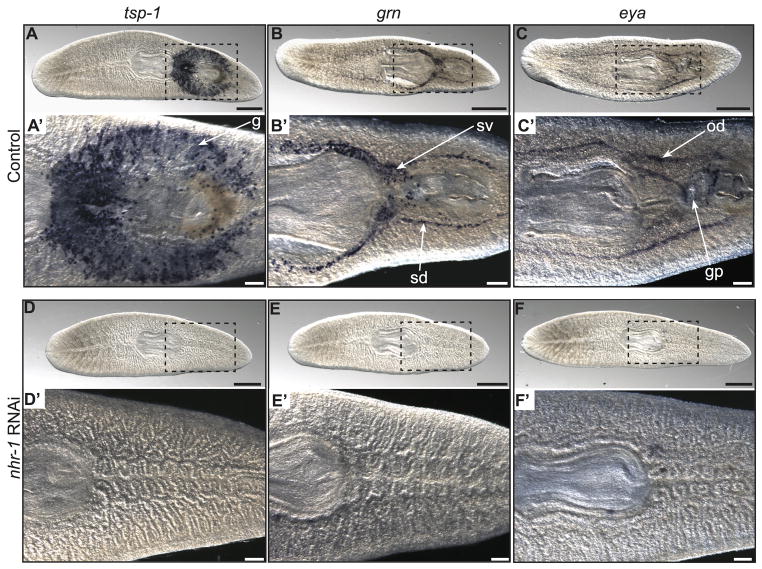

Given its broad expression in the reproductive system, we hypothesized that nhr-1 plays a role in regulating planarian sexual development or function. To test this hypothesis, we used RNA interference (RNAi) to disrupt nhr-1 expression and examined the consequences on the reproductive system. For these experiments, we fed juvenile planarians nhr-1 or control double-stranded RNA every four days for approximately one month, which resulted in a 94% reduction in nhr-1 mRNA levels in nhr-1(RNAi) animals compared to controls (Fig. S2A). Since nhr-1 was detected exclusively in accessory reproductive tissues of the planarian, we examined if nhr-1 loss disrupted the development of these organs using previously reported markers (Chong et al., 2011). Consistent with a role for nhr-1 in the development of the accessory reproductive organs, we found that nhr-1(RNAi) planarians had reduced expression of markers for the oviducts (eya), sperm ducts (grn), seminal vesicles (grn), and cement glands (tsp-1) (3/3 nhr-1(RNAi) animals vs. 0/3 control(RNAi) animals) (Fig. 3A–F′). Additionally, reduction of nhr-1 prevented development of the gonopore (Fig. 3C′ and F′). The relative quantity of each accessory reproductive organ marker is shown by qRT-PCR in control and nhr-1(RNAi) worms (Fig. S2A). Taken together, these data suggest that nhr-1 is required for the development of accessory reproductive tissues, including structures that lack high levels of nhr-1 expression, such as the gonopore and cement glands.

Fig. 3. Disruption of nhr-1 prevents development of accessory reproductive organs.

(A–C′) Whole-mount, colorimetric in situ hybridization to detect tsp-1 in the cement glands (g), grn in the sperm ducts (sd) and seminal vesicles (sv), and eya in the oviducts (od) in adult sexual animals after being fed a control double-stranded RNA. (D–F′) In situ hybridization for tsp-1, grn, and eya after being fed nhr-1 double-stranded RNA. Expression of these genes is not detected. The gonopore (gp) is also missing from nhr-1 knockdown animals. Ventral view shown for all animals. Data are representative of three individual planarians. Scale bars: (A–F) 500 μm. (A′–F′) 200 μm.

nhr-1 is required for male and female germ cell development

Since nhr-1 functions in the development of somatic reproductive tissues, we next wanted to test whether this gene plays a role in the development of the male and female germ cells. The male germ cells reside in numerous testis lobes that occupy the dorsolateral region of the adult worm. In reproductively mature animals, each testis lobe contains the different stages of germ cell development: the outermost spermatogonial layer possesses the nanos+ GSCs that divide to produce spermatogonia, and differentiate to produce spermatocytes, spermatids, and finally mature sperm (Wang et al., 2010). The germ cells are ensheathed by somatic cells (Chong et al., 2013).

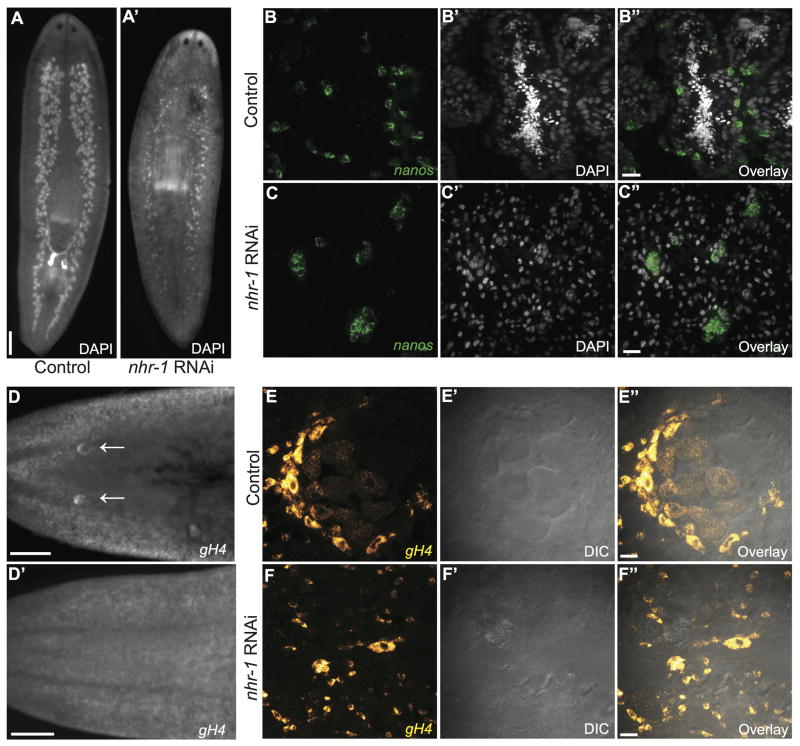

To test whether nhr-1 is required for germ cell development, we disrupted nhr-1 expression using RNAi and analyzed the planarian testes using nanos mRNA to label the GSCs and DAPI to label nuclei. Consistent with a role of nhr-1 in testis development, the majority of testis lobes in nhr-1 knockdown animals lost all sperm, spermatids, and spermatocytes (96%, n=3745 testis lobes from 20 nhr-1(RNAi) animals vs. 5%, n=4861 testis lobes from 20 control (RNAi) animals)(Fig. 4 A–C″). As a result, the testes clusters of nhr-1(RNAi) planarians were almost entirely composed of nanos+ cells (6/7 nhr-1(RNAi) animals vs. 0/2 control (RNAi) animals) (Fig. 4B–C″). Even in the most severe nhr-1 knockdown animals, we still observed clusters of GSCs expressing nanos, and unchanged nanos mRNA levels compared to control(RNAi) animals (measured by qRT-PCR, Fig. S2B), indicating that nhr-1 is not required for the maintenance of GSCs, but for the maturation and/or differentiation of male germ cells.

Fig. 4. nhr-1 is required for the development of male and female germ cells.

(A, A′) Dorsal view of DAPI stained adult sexual planarians after (left) control and (right) nhr-1 dsRNA treatment. (B–C″) Fluorescence in situ hybridization showing nanos expression (green) and DAPI staining (grey) in the testes of (B–B″) control and (C–C″) nhr-1(RNAi) animals. Images are maximum intensity projections of confocal Z-stacks. (D, D′) Ventral, anterior view of gH4-labeled cells in control (top) and nhr-1 RNAi (bottom) treated worms seen by fluorescence in situ hybridization. (E–F″) A single ovary from (E–E″) control and (F–F″) nhr-1(RNAi) animals showing gH4 mRNA in yellow and DIC. Scale bars: (A, A′, D, D′) 500 μm; (B–C″, E–F″) 20 μm.

We also examined the ovaries of nhr-1 knockdown animals using germinal histone 4 (gH4), a marker for undifferentiated germ cells and neoblasts (Wang et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2007)(Fig. 4D–F″). The planarian ovaries are located at the base of the cephalic ganglia where oocytes differentiate from GSCs before being deposited into the tuba for fertilization (Chong et al., 2011; Newmark et al., 2008). Using fluorescent in situ hybridization for gH4 mRNA and Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) microscopy, we observed well-organized mature ovaries producing oocytes in control double-stranded RNA-treated planarians (Fig. 4D, E–E″; n= 4/4). By contrast, inhibition of nhr-1 resulted in loss of ooctyes and irregular ovary morphology (Fig. 4D′, F–F″; n=10/10). In these nhr-1(RNAi) planarians we only observed scattered gH4-positive cells in the region in which the ovaries should reside (Fig. 4F–F″). Together, these data indicate that nhr-1 is required for normal male and female germ cell development.

DISCUSSION

By comparing the expression of NHR mRNAs in sexual and asexual planarians, we identified nhr-1 as a key regulator of planarian sexual development. We found that nhr-1 is essential for the development of accessory reproductive structures, and further, required for the differentiation and maturation of male and female germ cells. Robust nhr-1 expression was detected in the accessory reproductive organs; by contrast, it was not detected in germ cells. Based on these observations, we suggest that nhr-1 is acting cell non-autonomously to regulate germ cell development from the accessory reproductive organs. Interestingly, our results parallel those of Drosophila Hr39 that is required for spermathecae and parovaria gland development. Since these reproductive glands produce secretions that are required for germ cell viability, Hr39, like nhr-1, acts cell non-autonomously in germ cells by maintaining somatic reproductive structures (Sun and Spradling, 2013). Collectively, these findings reinforce the idea that long-range hormonal signals between the soma and germline are a critical driver of planarian sexual development, as well as support an essential role for NHR signaling in regulating sexual reproduction in a diverse array of metazoans.

Planarian germline-soma dynamics

Based on our data, the development of planarian germ cells and somatic reproductive organs is interconnected, ensuring that one system does not grow and differentiate prematurely, before the other system is ready. For example, sperm should not mature before the seminal vesicles, required for sperm storage, have developed. We suggest that signaling between the germline and soma allows for the coordinated development and maturation of both the planarian germ cells and the accessory reproductive organs as follows: (1) a lipophilic hormone is produced and activates nhr-1 in accessory reproductive tissues. (2) In turn, nhr-1 regulates the transcription of genes responsible for the development and maturation of accessory reproductive organs. (3) As these accessory organs mature, they send uncharacterized signals back to the germ cells, instructing them to develop in tandem with the accessory reproductive structures. Our model is consistent with phenotypes in which the loss of accessory reproductive structures (i.e. nhr-1 RNAi) leads to germline regression. In the case of planarian dmd-1, which is expressed in the somatic testes cells and male accessory reproductive organs, loss of male germ cells is observed while the female accessory reproductive organs and germ cells remain (Chong et al., 2013). Conversely, it is known that loss of germ cells (e.g., in nanos RNAi) leads to regression of the accessory reproductive structures upon amputation and regeneration of head fragments (Wang et al., 2007). Clearly, communication between the accessory reproductive tissues and gonads is critical for the maturation, maintenance, and plasticity of these organ systems.

Potential roles in flatworm parasite biology

The parasitic flatworm Schistosoma mansoni infects more than 200 million people worldwide, causing disease-associated disability comparable with that of global killers including malaria, tuberculosis, or HIV/AIDS (Chitsulo et al., 2000; Collins and Newmark, 2013; Hotez and Fenwick, 2009; King and Dangerfield-Cha, 2008). The primary driver of the pathology associated with Schistosoma infection is attributed to the host immune response against the massive egg output of the parasite. In fact, schistosomes incapable of egg production cause virtually no pathology in their mammalian host (Basch, 1991; Collins and Newmark, 2013). Thus, blunting schistosome reproduction represents an appealing means by which to control pathology while simultaneously preventing the spread of the disease. NHR-1 belongs to a novel family of hormone receptors that is conserved among lophotrochozoans, including planarians and schistosomes. Since this family of receptors does not appear to be present in mammals, and is essential for planarian reproduction, understanding the function of this group of receptors in schistosomes could illuminate novel avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Planarians contain a lophotrochozoan-specific class of two DNA-binding domain nuclear hormone receptors

nhr-1 is expressed solely in the sexually reproducing strain of S. mediterranea

nhr-1 expression is detected in male and female accessory reproductive structures

Development of the accessory reproductive organs and germ cells requires nhr-1

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Melanie Issigonis and Amir Saberi for their comments on the manuscript, as well as the members of the Newmark lab for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH R21AI099642 and R01HD043403 (P.A.N.). P.A.N. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ables ET, Drummond-Barbosa D. The steroid hormone ecdysone functions with intrinsic chromatin remodeling factors to control female germline stem cells in Drosophila. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:581–592. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen AK, Spradling AC. The Sf1-related nuclear hormone receptor Hr39 regulates Drosophila female reproductive tract development and function. Development. 2008;135:311–321. doi: 10.1242/dev.015156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asahina M, Ishihara T, Jindra M, Kohara Y, Katsura I, Hirose S. The conserved nuclear receptor Ftz-F1 is required for embryogenesis, moulting and reproduction in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Cells. 2000;5:711–723. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basch PF. Schistosomes: development, reproduction, and host relations. Oxford University Press; New York: 1991. p. 248. [Google Scholar]

- Buszczak M, Freeman MR, Carlson JR, Bender M, Cooley L, Segraves WA. Ecdysone response genes govern egg chamber development during mid-oogenesis in Drosophila. Development. 1999;126:4581–4589. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney GE, Bender M. The Drosophila ecdysone receptor (EcR) gene is required maternally for normal oogenesis. Genetics. 2000;154:1203–1211. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.3.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cebria F, Newmark PA. Planarian homologs of netrin and netrin receptor are required for proper regeneration of the central nervous system and the maintenance of nervous system architecture. Development. 2005;132:3691–3703. doi: 10.1242/dev.01941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell PE, Lydon JP, Conneely OM, O’Malley BW, Levine JE. Endocrine defects in mice carrying a null mutation for the progesterone receptor gene. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4147–4152. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.10.5456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitsulo L, Engels D, Montresor A, Savioli L. The global status of schistosomiasis and its control. Acta Trop. 2000;77:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(00)00122-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong T, Collins JJ, 3rd, Brubacher JL, Zarkower D, Newmark PA. A sex-specific transcription factor controls male identity in a simultaneous hermaphrodite. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1814. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong T, Stary JM, Wang Y, Newmark PA. Molecular markers to characterize the hermaphroditic reproductive system of the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. BMC Dev Biol. 2011;11:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-11-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbourne JK, Pfrender ME, Gilbert D, Thomas WK, Tucker A, Oakley TH, Tokishita S, Aerts A, Arnold GJ, Basu MK, Bauer DJ, Caceres CE, Carmel L, Casola C, Choi JH, Detter JC, Dong Q, Dusheyko S, Eads BD, Frohlich T, Geiler-Samerotte KA, Gerlach D, Hatcher P, Jogdeo S, Krijgsveld J, Kriventseva EV, Kultz D, Laforsch C, Lindquist E, Lopez J, Manak JR, Muller J, Pangilinan J, Patwardhan RP, Pitluck S, Pritham EJ, Rechtsteiner A, Rho M, Rogozin IB, Sakarya O, Salamov A, Schaack S, Shapiro H, Shiga Y, Skalitzky C, Smith Z, Souvorov A, Sung W, Tang Z, Tsuchiya D, Tu H, Vos H, Wang M, Wolf YI, Yamagata H, Yamada T, Ye Y, Shaw JR, Andrews J, Crease TJ, Tang H, Lucas SM, Robertson HM, Bork P, Koonin EV, Zdobnov EM, Grigoriev IV, Lynch M, Boore JL. The ecoresponsive genome of Daphnia pulex. Science. 2011;331:555–561. doi: 10.1126/science.1197761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JJ, 3rd, Hou X, Romanova EV, Lambrus BG, Miller CM, Saberi A, Sweedler JV, Newmark PA. Genome-wide analyses reveal a role for peptide hormones in planarian germline development. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JJ, 3rd, Newmark PA. It’s no fluke: the planarian as a model for understanding schistosomes. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003396. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis WC. The life history, the normal fission, and the reproductive organs of Planaria maculata. Proc Boston Soc Nat Hist. 1902;30:515–559. [Google Scholar]

- Gissendanner CR, Crossgrove K, Kraus KA, Maina CV, Sluder AE. Expression and function of conserved nuclear receptor genes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 2004;266:399–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gissendanner CR, Kelley K, Nguyen TQ, Hoener MC, Sluder AE, Maina CV. The Caenorhabditis elegans NR4A nuclear receptor is required for spermatheca morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2008;313:767–786. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handberg-Thorsager M, Salo E. The planarian nanos-like gene Smednos is expressed in germline and eye precursor cells during development and regeneration. Dev Genes Evol. 2007;217:403–411. doi: 10.1007/s00427-007-0146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotez PJ, Fenwick A. Schistosomiasis in Africa: an emerging tragedy in our new global health decade. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CH, Dangerfield-Cha M. The unacknowledged impact of chronic schistosomiasis. Chronic Illn. 2008;4:65–79. doi: 10.1177/1742395307084407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RS, Newmark PA. In situ hybridization protocol for enhanced detection of gene expression in the planarian Schmidtea mediterranea. BMC Dev Biol. 2013;13:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-13-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CM, Newmark PA. An insulin-like peptide regulates size and adult stem cells in planarians. Int J Dev Biol. 2012;56:75–82. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.113443cm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan TH. Growth and regeneration in Planaria lugubris. Arch Ent Mech Org. 1902;13:179–212. [Google Scholar]

- Neill JD. Knobil and Neill’s Physiology of Reproduction. 3. Elsevier Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Newmark PA, Wang Y, Chong T. Germ cell specification and regeneration in planarians. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2008;73:573–581. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2008.73.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raska O, Kostrouchova V, Behensky F, Yilma P, Saudek V, Kostrouch Z, Kostrouchova M. SMED-TLX-1 (NR2E1) is critical for tissue and body plan maintenance in Schmidtea mediterranea in fasting/feeding cycles. Folia Biol (Praha) 2011;57:223–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb SM, Ross E, Sanchez Alvarado A. SmedGD: the Schmidtea mediterranea genome database. Nucl Acids Res. 2008;36:D599–606. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouhana L, Vieira AP, Roberts-Galbraith RH, Newmark PA. PRMT5 and the role of symmetrical dimethylarginine in chromatoid bodies of planarian stem cells. Development. 2012;139:1083–1094. doi: 10.1242/dev.076182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K, Shibata N, Orii H, Amikura R, Sakurai T, Agata K, Kobayashi S, Watanabe K. Identification and origin of the germline stem cells as revealed by the expression of nanos-related gene in planarians. Dev Growth Diff. 2006;48:615–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2006.00897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout EP, La Clair JJ, Snell TW, Shearer TL, Kubanek J. Conservation of progesterone hormone function in invertebrate reproduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11859–11864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006074107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Spradling AC. Ovulation in Drosophila is controlled by secretory cells of the female reproductive tract. eLife. 2013;2:e00415. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner DE, Wang IE, Reddien PW. Clonogenic neoblasts are pluripotent adult stem cells that underlie planarian regeneration. Science. 2011;332:811–816. doi: 10.1126/science.1203983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker VR, Korach KS. Estrogen receptor knockout mice as a model for endocrine research. Ilar j. 2004;45:455–461. doi: 10.1093/ilar.45.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Stary JM, Wilhelm JE, Newmark PA. A functional genomic screen in planarians identifies novel regulators of germ cell development. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2081–2092. doi: 10.1101/gad.1951010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zayas RM, Guo T, Newmark PA. nanos function is essential for development and regeneration of planarian germ cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5901–5906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609708104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Niles EG, Hirai H, LoVerde PT. Evolution of a novel subfamily of nuclear receptors with members that each contain two DNA binding domains. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.