Abstract

Background & Aims

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a neurologic disorder that develops during liver failure. Few studies exist investigating systemic-central signaling during HE outside of inflammatory signaling. The transcription factor Gli1, which can be modulated by hedgehog signaling or transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) signaling, has been shown to be protective in various neuropathies. We measured Gli1 expression in brain tissues from mice and evaluated how circulating TGFβ1 and canonical hedgehog signaling regulate its activation.

Methods

Mice were injected with azoxymethane (AOM) to induce liver failure and HE in the presence of Gli1 Vivo-morpholinos (to mediate knockdown), the hedgehog inhibitor cyclopamine, smoothened Vivo-morpholinos, a smoothened agonist, or TGFβ-neutralizing antibodies. Molecular analyses were used to assess Gli1, hedgehog signaling, and TGFβ1 signaling in the liver and brain of AOM mice and HE patients.

Results

Gli1 expression was increased in brains of AOM mice and in HE patients. Intra-cortical infusion of Gli1 Vivo-morpholinos exacerbated the neurologic deficits of AOM mice. Measures to modulate hedgehog signaling had no effect on HE neurological decline. Levels of TGFβ1 increased in the liver and serum of mice following AOM administration. TGFβ neutralizing antibodies slowed neurologic decline following AOM administration without significantly affecting liver damage. TGFβ1 inhibited Gli1 expression via a SMAD3-dependent mechanism. Conversely, inhibiting TGFβ1 increased Gli1 expression.

Conclusions

Cortical activation of Gli1 protects mice from induction of HE. TGFβ1 suppresses Gli1 in neurons via SMAD3 and promotes neurologic decline. Strategies to activate Gli1 or inhibit TGFβ1 signaling might be developed to treat patients with HE.

Keywords: Sonic hedgehog, acute liver failure, azoxymethane, SMAD3, TGFβ1, hepatic encephalopathy

Introduction

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a neurological complication that can arise following acute or chronic liver damage and is a metabolically-induced, functional disturbance of the brain [1]. The most severe form of HE occurs following acute liver failure, which can be caused by drug-related liver damage, hyperthermic injury, and toxin exposure [2]. The neurological decline observed in HE is caused by toxin accumulation in the blood, which has the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier and generate neurotoxic effects to include swelling of astrocytes, cerebral edema, and dysregulation of water balance [3]. Associated with impairment of astrocyte function is a decrease in neuronal function, which leads to progressive cognitive deficits, motor deficits, and eventually coma [4].

Glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1 (Gli1), a member of the Gli family of transcription factors, is protective in neurological conditions such as ischemic injury, stroke, and Parkinson's disease [5–7]. Activation of Gli1 is a downstream consequence of the hedgehog pathway, via the activation of smoothened [8]. However, signaling outside of the canonical hedgehog pathway can also regulate Gli activity, such as transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFβ1) signaling [9, 10]. The signaling ligand TGFβ1 binds a receptor complex containing TGFβ receptor 2 (TGFβR2) leading to the phosphorylation/activation of SMAD3 which translocates to the nucleus and regulates transcription [11]. Therefore, understanding both canonical hedgehog signaling and non-canonical pathways, such as TGFβ1, is required to elucidate the regulation of Gli transcription factors during disease states.

Currently, studies addressing the circulating factors released during liver failure and their influence on HE brain pathology are lacking. Recent data suggests that hedgehog signaling is involved in expansion of liver progenitor cells after injury, and thus can play a protective role in the liver itself [12]. The hedgehog ligands Sonic hedgehog (Shh) and Indian hedgehog (Ihh) are released from hepatocytes in various models of liver damage, where they act on liver myofibroblasts and activate endothelial cells [13, 14]. Conversely, TGFβ1 signaling has been assessed in chronic liver disease and fibrosis models where it facilitates fibrogenesis while also having anti-inflammatory effects [15]. Necrotic hepatocytes release TGFβ1 into the local microenvironment where they are able to initiate the activation of nearby hepatic stellate cells [16]. Furthermore, studies have found that rats with hepatic failure have elevated levels of serum TGFβ1 [17]. Currently little information exists concerning the roles of either cortical hedgehog or TGFβ1 signaling during HE pathogenesis.

Due to the lack of understanding of neural hedgehog pathway activation during HE, as well as the signaling that occurs between the circulation and brain in this disorder, the current study aims to assess the regulation and effects of neural Gli1 activation during HE and to determine how circulating Shh and TGFβ1 can influence its activation.

Materials and Methods

Materials

See Supplement for the source of materials.

Murine azoxymethane model of hepatic encephalopathy

Male C57Bl/6 mice (25–30 g; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) received a single intraperitoneal injection of 100 μg/g of azoxymethane (AOM) to induce acute liver failure and HE. Following injection, mice were monitored every two hours (starting at eight hours post AOM) for body temperature, weight and neurological decline. In parallel, mice were pretreated with various agents aimed at targeting smoothened, TGFβ1 or Gli1 expression prior to AOM injection. The endpoint for AOM studies was coma, which was defined as a loss of righting and corneal reflexes (for further methodological details, see Supplement). All experiments performed complied with the Scott & White Memorial Hospital IACUC regulations on animal experiments (protocol #2012-019-R).

Neuron Isolation

Primary neurons were isolated from P1 rat pups and used in molecular analyses. Full details of isolation and treatments are outlined in the Supplement.

Human samples

Brain tissue from patients who had HE following liver cirrhosis or aged-matched controls without liver disease were supplied through either the autopsy service from Scott & White Memorial Hospital Department of Pathology (Temple, TX) or the New South Wales Tissue Resource Centre at the University of Sydney. Patient information and cause of death can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of patient treatment groups

| Control (n=7) | Cirrhotic with HE (n=8) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male/Female ratio | 6/1 | 6/2 |

| Age (avg ± SEM) | 51.1 ± 2.51976 | 59.6 ± 3.93171 |

| Median age (range) | 50 (37–61 yr) | 58 (40–75 yr) |

| Cause of death | Cardiac (n=7) | HE (n=8) |

Liver Biochemistry

Plasma alanine aminotransferasase and bilirubin were assessed using commercially available kits. Alanine aminotransferase measurement was performed using a fluoremetric activity assay (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Total bilirubin was assayed using a total bilirubin ELISA (CusaBio, Wuha, China). All assays and subsequent analyses were performed according to manufacturers instructions.

Molecular analyses

Expression and subcellular localization of the described target genes were assessed by real-time PCR (RT-PCR), immunoblotting, immunohistochemistry or immunofluorescence as previously described [18, 19]. Phospho-SMAD3 (pSMAD3) and TGFβ1 analyses were performed using Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (for specific details, see Supplement).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism software (Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA). Results were expressed as mean ± SEM. For data that passed normality tests, the Student t test was used when differences between two groups were analyzed, and analysis of variance when differences between three or more groups were compared followed by the appropriate ad hoc test. If tests for normality failed, two groups were compared with a Mann-Whitney U test or a Kruskal-Wallis ranked analysis when more than two groups were analyzed. Differences were considered significant when the p value was less than 0.05.

Results

Gli1 was activated in the cortex during HE

The AOM model of HE is characterized by consistent neurological decline towards coma. To better understand disease progression, we performed molecular analyses at times prior to neurological symptom onset, where minor neurological deficits were evident, and at coma (Fig. 1A). In order to validate liver damage, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains and liver biochemistry were assessed at various stages in AOM-treated and vehicle-treated mice. AOM-treated mice displayed progressive liver damage with mice at coma having severe parenchymal damage including diffuse necrosis of hepatocytes and steatosis of surviving hepatocytes (Fig. 1B). Serum enzyme assays for bilirubin and ALT supports these liver damage assessments (Table 2).

Fig. 1. Acute liver insult led to cortical Gli1 activation.

(A) Time course of neurological decline present in the AOM HE model. Neurological score is a measure of 6 reflexes scored between 0 and 2 with a lower score indicating greater neurological decline. The time points of specific stages of neurological decline are identified on the graph. (B) H&E histochemistry in vehicle and AOM-treated livers at the indicated timepoints. (C) Cortical Gli1 mRNA expression after AOM treatment at the indicated stages of neurological decline. (D) Gli1 immunostaining in the cortex at the various neurological stages following AOM injection. Subcellular location of immunoreactivity is indicated by a black arrow (cytoplasmic staining) or red arrow (nuclear staining). Quantitation of Gli1 immunohistochemistry including relative field staining intensity (left axis) and percentage of Gli1-positive cells that undergo nuclear translocation (right axis). (E) Gli1 expression in vehicle and AOM cortex at coma was assessed by immunofluorescence and counterstained with the neuron marker NeuN or the astrocyte marker GFAP. (F) Gli1 immunohistochemistry in patients from controls or HE patients. Quantification of Gli1 staining intensity and percent of nuclear translocated Gli1 positive cells are indicated. For mRNA analyses and quantitative IHC, data were reported as mean±SEM (n=4). *p<0.05 compared to vehicle cortex.

Table 2.

Serum liver enzymes for treated mice

| Bilirubin (nmol/ml) | ALT (U/L) | |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 4.60 ± 0.42 | 10.09 ±3.82 |

| AOM | 68.39 ± 5.29 * | 108.62 ± 20.51 * |

| AOM + Cyclopamine | 53.01 ± 1.20 * | 107.45 ± 16.45 * |

| Cyclopamine | 4.93 ± 0.10 # | 16.75 ± 6.30 # |

| AOM + anti TGFβ | 79.95 ± 12.33 * | 139.07 ± 6.30 * |

| anti TGFβ | 5.02 ± 0.13 # | 9.84 ±1.31 # |

| Mismatched-VM Vehicle | 1.56 ± 0.32 # | 10.41 + 1.43 # |

| Mismatched-VM AOM | 57.27 ± 3.22 * | 144.24 + 4.11 * |

| GM1-VM Vehicle | 1.82 ± 0.19 # | 9.03 + 2.50 # |

| GM1-VM AOM | 55.59 ± 4.65 * | 151.22 + 10.73 * |

= p<0.05 compared to vehicle,

= p<0.05 compared to AOM

The expression of Gli transcription factors was assessed at various time points after AOM injection. Cortical Gli1 mRNA was significantly upregulated in AOM mice after development of neurological symptoms and showed greatest elevation at coma (Fig. 1C). This elevation was not observed in the cerebellum of AOM mice (Supplement Fig. 1A). In addition, there was increased Gli1 immunoreactivity and nuclear translocation in the cortex as an early event after AOM injection that was significantly elevated in later stages of neurological decline (Fig. 1D). Moreover, Gli1 expression was found to co-localize with the neuronal marker NeuN, but not the astrocyte marker GFAP, in vehicle and AOM-treated mice at coma, suggesting that Gli1 upregulation occurs primarily in neurons (Fig. 1E). The upregulation of Gli1 was also observed in cortex from HE patients, with significant increases of Gli1 staining intensity and nuclear translocation compared to normal patients (Fig. 1F). In AOM mice, there were no significant changes in cortical Gli2 and Gli3 mRNA expression (Supplement Fig. 1B and 1C), immunoreactivity, or subcellular localization (Supplement Fig. 1D and 1E). Together, this suggests that Gli1 is the primary Gli transcription factor that responds to the neural changes that take place during HE. As Gli1 upregulation occurs to the greatest degree at coma, the remaining experiments were performed using tissue from mice at this time point.

Cortical Gli1 inhibition worsened neurological decline

Gli1 protein expression was knocked down via intracortical infusion of Gli1-VM sequences adjacent to the infusion site in the cortex (Fig. 2A). The Gli1-VM-mediated knockdown occurred approximately 2mm from the infusion site, which was centered in the frontal cortex, one of the areas most affected during HE. This leads to ablation of Gli1 protein in 9.27±0.81% of the total cortex area based on total volume measurements made by other researchers [20]. Diagrams of the affected regions of the brain indicate Gli1 protein knockdown (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, intracortical Gli1-VM infusion significantly exacerbated neurological decline observed after AOM injection (Fig. 2C) and shortened time to coma (Fig. 2D) compared to mice pretreated with mismatched-VM. Interestingly, there were no observable differences in liver damage between these treatment groups as demonstrated by H&E staining (Fig. 2E) and biochemical analyses (Table 2). Together, these data support Gli1 as a neuroprotective protein upregulated as a protective mechanism during HE.

Fig. 2. Suppression of Gli1 expression exacerbated neurological decline.

Mice were infused with Gli1-VM or mismatched-VM into the cortex 3 days prior to AOM injection. (A) Cortical Gli1 knockdown was validated by Gli1 immunofluorescence (red) near the infusion site (white arrow) with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue) used as a counterstain. (B) Diagram of Gli1-VM knockdown area from coronal and horizontal views of whole mouse brain. Diffusion of morpholino was 1.5 mm and is indicated by green circle. (C) Neurological decline was assessed using neurological score as previously described. Gli1-VM treatment significantly worsened neurological decline in AOM mice compared to mismatched-VM mice (p=.0435). (D) Gli1-VM infused AOM-treated mice entered coma significantly earlier than mismatched-VM infused, AOM-treated mice. (E) Liver damage was assessed in Gli1-VM and mismatched-VM mice by H&E histochemistry. Data were reported as mean±SEM (n=8). *p<0.05 compared to mismatched-VM cortex.

Circulating TGFβ1, but not Shh, was involved in neurological decline

Following AOM treatment, Shh mRNA and protein were elevated in the liver, (Supplement Fig. 2A and 2B) present in the serum, (Supplement Fig. 2C) though unchanged in the brain (Supplement Fig. 2D). Ihh expression was also assessed in the liver and brain with no significant differences between treatment groups (data not shown). Pretreatment with cyclopamine, a smoothened antagonist, prior to AOM did not significantly change neurological decline (Supplement Fig. 3A), time to coma (Supplement Fig. 3B), or liver damage (Table 2 and Supplement Fig. 3C). However, cyclopamine was able to slightly reduce Shh mRNA expression in the liver (Supplement Fig. 3D), reduce circulating Shh (Supplement Fig. 3E) and slightly dampen cortical Gli1 mRNA expression although it is still elevated above vehicle (Supplement Fig. 3F). To ensure that direct neural modulation of hedgehog signaling did not effect HE, smoothened agonist (SAG) or smoothened-VM were infused intracortically. Treatment with smoothened-VM generated no effect on time to coma and Gli1 immunoreactivity was still upregulated in the cortex of AOM mice (Supplement Fig. 4A and 4B). Also, SAG treatment had no effect on time to coma but did slightly increase Gli1 immunoreactivity (Supplement Fig. 4C and 4D).

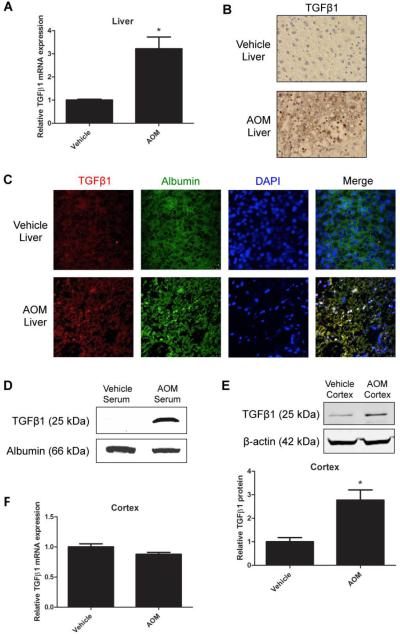

Since modulation of smoothened had little effect on HE pathogenesis, we assessed the effects of TGFβ1 signaling on Gli1 activation and neurological decline. Liver TGFβ1 mRNA expression was significantly elevated following AOM injection compared to controls (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, increased hepatic TGFβ1 immunoreactivity was found in AOM-treated mice versus controls (Fig. 3B). TGFβ1 immunoreactivity was found predominantly in albumin-positive cells in AOM mice, giving support that this protein is localized to hepatocytes during injury (Fig. 3C). In addition to this, active TGFβ1 was present in serum of AOM-injected mice, but at undetectable levels in control serum (Fig. 3D). In the brain, cortical TGFβ1 protein expression was significantly elevated in AOM-injected mice compared to controls (Fig. 3E and Supplement Fig. 5A). This increase in protein did not coincide with increased cortical TGFβ1 mRNA expression (Fig. 3F), suggesting that increased cortical TGFβ1 protein may not be derived from local increases in TGFβ1 gene expression but rather systemic increases in TGFβ1.

Fig. 3. TGFβ1 expression was upregulated in the liver and increased in the brain following HE.

(A) Liver TGFβ1 expression was assessed at coma in vehicle and AOM-treated mice by RT-PCR (B) and immunohistochemistry. (C) TGFβ1 (red) and albumin (green) colocalization in vehicle and AOM livers at coma. DAPI (blue) was used as a nuclear stain. (D) Serum TGFβ1 in vehicle and AOM-treated mice at coma by immunoblotting with albumin used as a loading control. (E) Cortical TGFβ1 protein expression at coma in vehicle and AOM-treated mice. (F) Cortical TGFβ1 mRNA expression in vehicle and AOM-treated mice at coma. For protein and mRNA analyses, data were reported as mean±SEM (n=4).

TGFβ1 modulation in primary neurons directly effected Gli1 expression via SMAD3

As TGFβR2 was found to colocalize with the neuron marker NeuN in the cortex of vehicle and AOM mice (Supplement Fig. 5B), we limited our in vitro studies to primary neuronal cultures. Treatment of neurons with rTGFβ1 for 24 hours suppressed Gli1 mRNA expression in a dose-dependent manner (Supplement Fig. 5C). Furthermore, treatment of neurons with rTGFβ1 (0.5 ng/ml) suppressed Gli1 mRNA from 3 hours to 24 hours (Supplement Fig. 5D). Conversely, treatment of neurons with neutralizing antibodies against TGFβ upregulated Gli1 mRNA expression at the 24-hour time point (Supplement Fig. 5E). Finally, treatment of neurons with specific inhibitor of SMAD3 (SIS3) was able to reverse Gli1 suppression by rTGFβ1 demonstrating that SMAD3 is required to propagate the suppressive effect of TGFβ1 on Gli1 expression (Supplement Fig. 5F).

TGFβ1 exacerbated neurological decline in AOM-treated mice

AOM mice that were pretreated with TGFβ neutralizing antibodies displayed significantly delayed neurological decline (Fig. 4A) and increased time taken to reach coma (Fig. 4B) compared to mice treated with AOM alone. Furthermore, total brain water was increased in AOM mice and was significantly reduced following treatment with TGFβ neutralizing antibodies (Fig. 4C). H&E stains and liver biochemistry analyses found no definitive differences in liver damage of AOM-treated mice and those pretreated with TGFβ neutralizing antibodies (Supplement Fig. 5G and Table 2). AOM-treated mice had increased phosphorylated SMAD3 protein in the cortex as assessed by EIA (Fig 4D), immunofluorescence (Supplements Fig 6A) and immunoblotting (Supplement Fig 6B) compared to mice pretreated with TGFβ neutralizing antibodies or vehicle controls, an effect that was also observed in cirrhotic patients with HE compared to normal patients (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, pretreatment of mice with TGFβ neutralizing antibodies prior to AOM injection increased cortical Gli1 mRNA expression to a greater degree than mice treated with AOM alone (Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4. Treatment of AOM mice with TGFβ neutralizing antibodies was neuroprotective.

A) Mice pretreated with TGFβ neutralizing antibodies (anti-TGFβ) prior to AOM injection had significantly lessened neurological decline (p=.0140). Neurological decline was assessed using the neurological score as previously described. (B) Time to coma for AOM and AOM + anti-TGFβ mice. (C) Percent of total brain water in cortex from vehicle, AOM, AOM + anti-TGFβ, or anti-TGFβ mice at coma. (D) Relative fluorescence of phospho-SMAD3 in vehicle, AOM, AOM + anti-TGFβ, or anti-TGFβ cortex at coma (E) and control or HE patient cortex. (F) Cortical Gli1 mRNA expression in vehicle, AOM, AOM + anti-TGFβ, or anti-TGFβ mice at coma. For ELISA and mRNA analyses, data were reported as mean±SEM (n=4). For time to coma and neurological decline analyses, data were reported as mean±SEM (n=12). *p<0.05 compared to vehicle liver or vehicle cortex. #p<0.05 compare to AOM cortex.

Discussion

Hepatic encephalopathy is a serious neurological complication that arises following liver disease [1]. Currently, HE has few effective treatments and thus the need to identify targets for potential therapeutics is very important. Here we demonstrated that i) Gli1 is upregulated in the cortex in the mouse AOM model of HE and is neuroprotective and ii) circulating TGFβ1 exacerbates HE neurological decline via suppression of Gli1 expression through a SMAD3-dependent pathway. Taken together, our data suggest that strategies to increase cortical Gli1 expression and/or inhibit TGFβ1 signaling may prove beneficial for the treatment of HE.

The data presented demonstrate that cortical Gli1 was activated in mice and patients with HE. Furthermore, inhibiting Gli1 expression in mice using VM technology exacerbated neurological decline, suggesting that Gli1 exerts a neuroprotective effect during HE. Similar upregulation of Gli1 has been observed in other pathological brain states. For example, following cortical freeze injury or intracortical lipopolysaccharide injection, Gli1 induction was present and dependent on the inflammatory process generated by the injury [21]. In addition, inhibition of Gli1 expression led to significant increases in infarct volume following ischemia [6]. The use of polydatin, an anti-inflammatory agent, to treat stroke induced Gli1 expression and was able to reduce acute brain injury damage [7]. These studies demonstrate that Gli1 is upregulated during brain pathologies and is neuroprotective, which supports the findings of the current study on HE.

Canonical hedgehog signaling has been shown to be upregulated during liver injury, liver regeneration and in a number of liver diseases [22]. Following liver damage, there is increased production of growth factors such as epidermal growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor and TGFβ1, which induce liver cells to produce hedgehog ligands [23, 24]. This leads to increased paracrine hedgehog signaling in the liver, which has been shown to be protective in cholestatic liver injury and facilitate liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy [23, 25]. Interestingly, reducing smoothened activity via cyclopamine has been shown to have differing effects during liver injury. Cyclopamine treatment following bile duct ligation and ischemia/reperfusion injury is hepatoprotective [26]. However, other studies show that cyclopamine disrupts liver regeneration, causes apoptosis of myofibroblasts and decreases cell survival of hepatic stellate cells [25, 27, 28]. The data presented in the current study shows that while Shh expression was increased in the liver and blood stream following AOM injection, inhibiting canonical hedgehog signaling did not significantly affect liver damage across all metrics measured, though bilirubin levels did drop slightly. This may be due to the acute and severe nature of the AOM model. Furthermore, cyclopamine had no effect on neurological decline even though the route and dose has previously been shown to inhibit brain hedgehog signaling [29]. Treatment of AOM mice with SAG or with smoothened-VM validated the results from cyclopamine-treated mice. Together, this indicates that the increase in cortical Gli1 expression during HE, and subsequent neuroprotection, may be due to other unidentified signaling factors, rather than canonical hedgehog signaling. Our understanding of the mechanisms by which Gli1 is activated in the brain is currently still not well understood and warrants further investigation.

Another interesting finding was that TGFβ1 was upregulated in the liver and present in the serum following liver damage. Interestingly, inhibition of circulating TGFβ1 via TGFβ-specific neutralizing antibodies delayed neurological decline in AOM mice. It should be noted that the larger molecular weight of neutralizing antibodies generally limits their passage across the blood-brain barrier and thus, this treatment would have little effect on neural TGFβ1 alone. In support of this, we have recently generated preliminary data using floxed TGFβ1/albumin-Cre mice, which demonstrate that gene ablation of TGFβ1 specifically in hepatocytes reduces neurological decline following AOM injection (data not shown). The deleterious role of TGFβ1 in the brain of AOM-treated mice might be related to its role of promoting inflammation [30]. In support of this concept, the pathogenic inflammation present in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis was dependent on TGFβ1 production in the CNS [31]. It is becoming evident that HE is dependent on a neuroinflammatory response. Recent studies show that microglia become activated in experimental hyperammonemia in rats and in patients who have HE [32]. Furthermore, it has been shown that liver failure due to hepatic devascularization leads to an increase of proinflammatory cytokines that correlates to microglia activation [33]. Additionally, mice that have an interleukin-1β or tumor necrosis factor alpha gene deletion have slower HE progression compared to wildtype [34]. Since TGFβ1 can regulate neuroinflammation seen in other neurological disorders, TGFβ1 may play a role in neuroinflammation observed following acute liver failure.

Here we demonstrated that TGFβ1 has an inhibitory effect on cortical Gli1 expression via a SMAD3-dependent mechanism. In contrast, previous studies show that TGFβ1 positively regulates Gli1 in pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells [9, 10]. The differences in response of Gli1 expression to TGFβ1 may lie in the cell type (i.e. neuronal versus pancreas) and/or the transformation status of the cell(i.e. non-malignant versus cancerous). For example, Gli1 regulates the cell cycle through cyclin D2 expression, which is more evident in cancer cells than in mature neurons that do not proliferate [35]. Also, the result that neurons elevate Gli1 mRNA expression when treated with neutralizing antibodies against TGFβ suggests that TGFβ1 is expressed endogenously in neurons. That being said, astrocytes and microglia also express TGFβ1 indicating that studies investigating the interactions between neurons and other neural cells may better explain neural TGFβ1 regulation [36]. However, our findings that cortical TGFβ1 mRNA expression is not significantly changed in AOM mice gives evidence that circulating TGFβ1 plays a more prominent role in Gli1 suppression. However our data does not rule out a role for posttranslational mechanisms in the expression of TGFβ1 in the cortex and thus, studies to answer this definitively are warranted.

In conclusion, the data presented demonstrate that Gli1 upregulation in cortical neurons occurred during HE and was protective against neurological decline seen during HE. In addition, there was release of hedgehog and TGFβ1 ligands from the liver, with TGFβ1 contributing to increased HE pathogenesis through neuronal suppression of Gli1. A working model of the liver-brain signaling axis as determined in this study is displayed in Supplement Fig. 7. This study demonstrates that suppressing circulating TGFβ1, or increasing cortical Gli1 activation, could serve as a potential therapeutic strategy for HE treatment. Furthermore, our findings suggest targeting the TGFβ1/Gli1 signaling axis could lend itself as a treatment strategy for other neurological disorders where inflammation and metabolic disturbances contribute to pathology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Central Texas Veterans Health Care System, Temple, Texas. Tissues were received from the New South Wales Tissue Resource Centre at the University of Sydney supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Schizophrenia Research Institute and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIH R24AA012725). The New South Wales Tissue Resource Centre has ethics approval from the Sydney Local Health Network Ethics Review Committee protocol number X011- 0107. The authors would also like to acknowledge Leticia Fuentes and Amber Jacobs for their technical assistance on this project.

Financial Support: The following study was funded by an NIH R01 award (DK082435), an NIH K01 award (DK078532) and a Scott & White Intramural grant award (No: 050339) to Dr. DeMorrow.

List of Abbreviations

- HE

hepatic encephalopathy

- AOM

azoxymethane

- TGFβ1

transforming growth factor beta 1

- Gli1

Glioma-associated oncogene homolog 1

- TGFβR2

TGFβ receptor 2

- Shh

Sonic hedgehog

- Ihh

Indian hedgehog

- HBC

(2-hydropropyl)-β-cyclodextrin

- VM

Vivo-morpholino

- SAG

smoothened agonist

- RT-PCR

reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- SIS3

specific inhibitor of SMAD3

- CNS

central nervous system

- DAPI

4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Cash WJ, McConville P, McDermott E, McCormick PA, Callender ME, McDougall NI. Current concepts in the assessment and treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. QJM. 2010;103:9–16. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcp152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bernal W, Auzinger G, Dhawan A, Wendon J. Acute liver failure. Lancet. 2010;376:190–201. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hazell AS, Butterworth RF. Hepatic encephalopathy: An update of pathophysiologic mechanisms. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1999;222:99–112. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.1999.d01-120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cauli O, Rodrigo R, Llansola M, Montoliu C, Monfort P, Piedrafita B, et al. Glutamatergic and gabaergic neurotransmission and neuronal circuits in hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis. 2009;24:69–80. doi: 10.1007/s11011-008-9115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Suwelack D, Hurtado-Lorenzo A, Millan E, Gonzalez-Nicolini V, Wawrowsky K, Lowenstein PR, et al. Neuronal expression of the transcription factor Gli1 using the Talpha1 alpha-tubulin promoter is neuroprotective in an experimental model of Parkinson's disease. Gene therapy. 2004;11:1742–1752. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ji H, Miao J, Zhang X, Du Y, Liu H, Li S, et al. Inhibition of sonic hedgehog signaling aggravates brain damage associated with the down-regulation of Gli1, Ptch1 and SOD1 expression in acute ischemic stroke. Neurosci Lett. 2012;506:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ji H, Zhang X, Du Y, Liu H, Li S, Li L. Polydatin modulates inflammation by decreasing NF-kappaB activation and oxidative stress by increasing Gli1, Ptch1, SOD1 expression and ameliorates blood-brain barrier permeability for its neuroprotective effect in pMCAO rat brain. Brain Res Bull. 2012;87:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Matise MP, Joyner AL. Gli genes in development and cancer. Oncogene. 1999;18:7852–7859. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Katoh Y, Katoh M. Integrative genomic analyses on GLI1: positive regulation of GLI1 by Hedgehog-GLI, TGFbeta-Smads, and RTK-PI3K-AKT signals, and negative regulation of GLI1 by Notch-CSL-HES/HEY, and GPCRGs-PKA signals. Int J Oncol. 2009;35:187–192. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Dennler S, Andre J, Alexaki I, Li A, Magnaldo T, ten Dijke P, et al. Induction of sonic hedgehog mediators by transforming growth factor-beta: Smad3-dependent activation of Gli2 and Gli1 expression in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6981–6986. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–584. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Omenetti A, Choi S, Michelotti G, Diehl AM. Hedgehog signaling in the liver. J Hepatol. 2011;54:366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Pereira Tde A, Witek RP, Syn WK, Choi SS, Bradrick S, Karaca GF, et al. Viral factors induce Hedgehog pathway activation in humans with viral hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Lab Invest. 2010;90:1690–1703. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Witek RP, Yang L, Liu R, Jung Y, Omenetti A, Syn WK, et al. Liver cell-derived microparticles activate hedgehog signaling and alter gene expression in hepatic endothelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:320–330. e322. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gressner AM, Weiskirchen R, Breitkopf K, Dooley S. Roles of TGF-beta in hepatic fibrosis. Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library. 2002;7:d793–807. doi: 10.2741/A812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Roth S, Michel K, Gressner AM. (Latent) transforming growth factor beta in liver parenchymal cells, its injury-dependent release, and paracrine effects on rat hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 1998;27:1003–1012. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Eguchi S, Kamlot A, Ljubimova J, Hewitt WR, Lebow LT, Demetriou AA, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure in rats: survival and effect on blood chemistry and liver regeneration. Hepatology. 1996;24:1452–1459. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Frampton G, Invernizzi P, Bernuzzi F, Pae HY, Quinn M, Horvat D, et al. Interleukin-6-driven progranulin expression increases cholangiocarcinoma growth by an Akt-dependent mechanism. Gut. 2012;61:268–277. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Quinn M, Ueno Y, Pae HY, Huang L, Frampton G, Galindo C, et al. Suppression of the HPA axis during extrahepatic biliary obstruction induces cholangiocyte proliferation in the rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G182–193. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00205.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lyck L, Kroigard T, Finsen B. Unbiased cell quantification reveals a continued increase in the number of neocortical neurones during early post-natal development in mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:1749–1764. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Amankulor NM, Hambardzumyan D, Pyonteck SM, Becher OJ, Joyce JA, Holland EC. Sonic hedgehog pathway activation is induced by acute brain injury and regulated by injury-related inflammation. J Neurosci. 2009;29:10299–10308. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2500-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Omenetti A, Diehl AM. The adventures of sonic hedgehog in development and repair. II. Sonic hedgehog and liver development, inflammation, and cancer. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G595–598. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00543.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Omenetti A, Yang L, Li YX, McCall SJ, Jung Y, Sicklick JK, et al. Hedgehog-mediated mesenchymal-epithelial interactions modulate hepatic response to bile duct ligation. Lab Invest. 2007;87:499–514. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yang L, Wang Y, Mao H, Fleig S, Omenetti A, Brown KD, et al. Sonic hedgehog is an autocrine viability factor for myofibroblastic hepatic stellate cells. J Hepatol. 2008;48:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ochoa B, Syn WK, Delgado I, Karaca GF, Jung Y, Wang J, et al. Hedgehog signaling is critical for normal liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in mice. Hepatology. 2010;51:1712–1723. doi: 10.1002/hep.23525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Pratap A, Panakanti R, Yang N, Lakshmi R, Modanlou KA, Eason JD, et al. Cyclopamine attenuates acute warm ischemia reperfusion injury in cholestatic rat liver: hope for marginal livers. Mol Pharm. 2011;8:958–968. doi: 10.1021/mp200115v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Seth D, Haber PS, Syn WK, Diehl AM, Day CP. Pathogenesis of alcohol-induced liver disease: classical concepts and recent advances. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1089–1105. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Sicklick JK, Li YX, Choi SS, Qi Y, Chen W, Bustamante M, et al. Role for hedgehog signaling in hepatic stellate cell activation and viability. Lab Invest. 2005;85:1368–1380. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lipinski RJ, Hutson PR, Hannam PW, Nydza RJ, Washington IM, Moore RW, et al. Dose- and route-dependent teratogenicity, toxicity, and pharmacokinetic profiles of the hedgehog signaling antagonist cyclopamine in the mouse. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2008;104:189–197. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lanz TV, Ding Z, Ho PP, Luo J, Agrawal AN, Srinagesh H, et al. Angiotensin II sustains brain inflammation in mice via TGF-beta. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2782–2794. doi: 10.1172/JCI41709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Luo J, Ho PP, Buckwalter MS, Hsu T, Lee LY, Zhang H, et al. Glia-dependent TGF-beta signaling, acting independently of the TH17 pathway, is critical for initiation of murine autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3306–3315. doi: 10.1172/JCI31763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zemtsova I, Gorg B, Keitel V, Bidmon HJ, Schror K, Haussinger D. Microglia activation in hepatic encephalopathy in rats and humans. Hepatology. 2011;54:204–215. doi: 10.1002/hep.24326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Jiang W, Desjardins P, Butterworth RF. Direct evidence for central proinflammatory mechanisms in rats with experimental acute liver failure: protective effect of hypothermia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:944–952. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bemeur C, Qu H, Desjardins P, Butterworth RF. IL-1 or TNF receptor gene deletion delays onset of encephalopathy and attenuates brain edema in experimental acute liver failure. Neurochem Int. 2010;56:213–215. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Shahi MH, Afzal M, Sinha S, Eberhart CG, Rey JA, Fan X, et al. Regulation of sonic hedgehog-GLI1 downstream target genes PTCH1, Cyclin D2, Plakoglobin, PAX6 and NKX2.2 and their epigenetic status in medulloblastoma and astrocytoma. BMC cancer. 2010;10:614. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Doyle KP, Cekanaviciute E, Mamer LE, Buckwalter MS. TGFbeta signaling in the brain increases with aging and signals to astrocytes and innate immune cells in the weeks after stroke. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:62. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.