Abstract

Black widow venom contains α-latrotoxin, infamous for causing intense pain. Combining 33 kb of Latrodectus hesperus genomic DNA with RNA-Seq, we characterized the α-latrotoxin gene and discovered a paralog, 4.5 kb downstream. Both paralogs exhibit venom gland specific transcription, and may be regulated post-transcriptionally via musashi-like proteins. A 4 kb intron interrupts the α-latrotoxin coding sequence, while a 10 kb intron in the 3′ UTR of the paralog may cause nonsense-mediated decay. Phylogenetic analysis confirms these divergent latrotoxins diversified through recent tandem gene duplications. Thus, latrotoxin genes have more complex structures, regulatory controls, and sequence diversity than previously proposed.

Keywords: α-Latrotoxin, venom, neurosecretion, Latrodectus, genomics, molecular evolution

1. Introduction

Venom proteins can evolve rapidly through gene duplication and adaptation in response to selection imposed by diverse and co-evolving prey [1–4]. Venom toxins also have important biomedical applications, including receptor characterization and drug discovery [5,6]. However, few studies have examined the structure and regulation of genes encoding venom proteins [7]. For spiders, one of the largest venomous clades, nearly all sequences come from venom gland cDNAs [8,9]. Thus, the roles of gene duplication, alternative splicing, and regulatory controls in generating venom molecular complexity are poorly understood.

The spider genus Latrodectus includes black widows (multiple species) and the Australian red-back spider (L. hasselti), the venoms of which have potent neurotoxic effects on vertebrates. Latrodectus venom contains latrotoxins, a family of neurotoxic proteins that share a unique N-terminal domain flanked by 11–20 ankyrin motif repeats [6,8,10]. Four latrotoxins have been functionally characterized from L. tredecimguttatus, and while three (α-latroinsectotoxin, α-latrocrustotoxin and δ-latroinsectotoxin) elicit neurotransmitter release in arthropods [11], α-latrotoxin forms calcium channels in vertebrate pre-synaptic neuronal membranes, thereby triggering massive neurotransmitter exocytosis [12–14]. α-Latrotoxin is responsible for the extreme pain resulting from black widow bites [6], and is important for studying neurosecretion, and hence has received considerable scientific attention.

While Latrodectus venom contains multiple latrotoxins, they have only been identified in three genera of the family Theridiidae, suggesting latrotoxins represent a recently expanded protein family [8,15,16]. Evidence from RNA-Seq data indicates ≥20 divergent latrotoxins are expressed in venom glands of the Western black widow (Latrodectus hesperus) and most are phylogenetically distinct from the functionally characterized latrotoxins [16]. We hypothesize these transcripts are encoded by distinct loci that are spatially clustered in the genome and that their transcription and translation is tightly controlled to ensure strong venom gland-specific expression.

We sequenced 33 kb from the L. hesperus genome encompassing the α-latrotoxin gene, which we integrated with venom gland expression data (RNA-Seq and Expressed Sequence Tags (ESTs)) to reveal α-latrotoxin’s gene structure, quantify its expression, and investigate its regulation. This revealed a divergent, highly expressed latrotoxin paralog 4.5 kb downstream of α-latrotoxin, and long introns and putative regulatory elements in both paralogs, providing novel insights into latrotoxin evolution and production.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Genomic Sequencing

A genomic library was constructed from eight L. hesperus females to cover the estimated 1261 Mb genome [17]. Library construction details are in Supplementary Material and Ayoub et al. [18]. α-Latrotoxin primers were used to PCR-screen the genomic library, revealing three positive clones. The clone with the smallest insert (estimated from a BamHI digest) was used to make a shotgun library from three complete, separate digests (EcoRI, PstI and EcoRV). Resulting fragments were ligated into pZErO™-2 plasmids (Invitrogen) and electroporated into TOP10 E. coli. For each digest, a library of 192 clones was screened for insert size. 1–2 kb inserts were sequenced using Sp6 and T7 primers. Sequences were edited and assembled in SEQUENCHER 4.2 (Gene Codes Corp.). Primer walking was employed to complete insert sequencing. The complete sequence was deposited at NCBI (Accession KM382064).

2.2. Genomic Annotation

Open Reading Frames (ORFs) were predicted from the assembled genomic insert sequence using getORF, retaining ORFs encoding ≥30 amino acids. Predicted proteins were subjected to BLASTp searches against NCBI’s non-redundant (nr) protein database. Gene structure and expression were explored using female L. hesperus RNA-Seq data [19] from three tissues: (1) venom gland, (2) total silk gland tissues, and (3) cephalothorax minus venom glands [16,19]. This included 133 million high quality 75–100 bp paired-end sequence reads collectively. Trinity [20] was used to assemble tissue-specific reads, and overlapping sequences across libraries were merged using CAP3 [19]. Tophat 2.0.8b [21] was used to align RNA-Seq reads from tissues to the genomic sequence to map introns, which were visualized with Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) 2.3 [22]. Cufflinks 2.0.2 [23] was used to assemble transcripts from Tophat mappings, filtering out isoforms representing <10% of major isoform abundance. Cuffmerge was used to merge assemblies from tissues, and Cuffdiff was used to produce expression estimates for transcripts in each tissue. OrfPredictor [24] was used to translate proteins from transcripts in the frame of the top nr BLASTx hit. We also mapped L. hesperus venom gland ESTs [25] (NCBI dbEST Accessions JZ577614 - JZ578096) to the genomic sequence.

The insert sequence was annotated with MAKER [26]. Gene prediction was performed using Augustus under Drosophila melanogaster training parameters and mapping: (1) de novo Trinity assembled transcripts [19] (2) Cufflinks transcripts predicted from the insert, (3) venom gland ESTs [25] and (4) latrotoxins translated from Trinity transcripts. RepeatMasker [27] was used to predict repetitive elements and low complexity regions with the D. melanogaster database. The programs NNPP 2.2, Match 1.0, UTRscan, and PipMaker [28–31] were used to predict regulatory elements (Supplementary Materials).

2.3. Evolutionary Analyses

We obtained latrotoxin proteins from NCBI’s nr and extracted L. tredecimguttatus latrotoxins [8] from the transcriptome shotgun assembly archive using tBLASTn (e-value cutoff 1e-20), with the first 320 amino acids from L. hesperus latrotoxins [16] as queries. L. tredecimguttatus translations were obtained with OrfPredictor [24]. We aligned these sequences with L. hesperus latrotoxins predicted by Cufflinks from the genomic insert and de novo assembled from RNA-Seq data [16,19] with COBALT [32]. Phylogenetic analyses were performed with Mr. Bayes 3.2.2 [33], with a “mixed” amino acid model and gamma distribution, running 5 × 106 generations. Clade posterior probabilities were from a 50% majority-rule tree, excluding the first 25% of trees. We produced a nucleotide alignment with PAL2NAL [34] from the protein alignment (Supplementary Materials). PAML 4 [35] was used to test for positive selection among sites by comparing Model M7 (several dN/dS categories between 0 and 1), and model M8 (adds category with unconstrained dN/dS), and among sites along specific branches by comparing models A and Aω2=1. MEME [36] was also employed to find sites under diversifying selection across the latrotoxin phylogeny with an FDR < 0.05.

3. Results

3. 1. Venom Expressed Tandem Latrotoxins

We sequenced 33,342 bp of L. hesperus DNA from a genomic library clone containing the α-latrotoxin gene. Sanger sequencing and shotgun assembly of 236 subclones resulted in six contigs 968–8347 bp long, and the assembly was finished through primer walking. getORF predicted 129 proteins in both directions, 15 with significant BLASTp hits (Table 1). Two proteins (1401 and 1393 amino acids) had top BLASTp hits to α-latrotoxin. The upstream predicted protein had a top hit to L. hesperus α-latrotoxin with 99% identity and represents the α-latrotoxin locus, while the downstream latrotoxin had a best match to Steatoda grossa α-latrotoxin at 44% identity, and represents an adjacent paralog (Table 1). The translated tandem L. hesperus latrotoxins share 43% protein sequence identity.

Table 1.

BLASTp hits for the proteins predicted by the getORF program from the complete L. hesperus 33 kb 119_P5 genomic insert sequence. Start and end columns indicate position of the ORF in the sequence. The final column indicates whether the best-hit NCBI accession is a transposable element.

| Accession | Description | e-value | start | end | length | TE? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGD80166.1 | Alpha-latrotoxin (Latrodectus hesperus) | 0.0 | 2271 | 6473 | 4203 | N |

| EEZ99596.1 | hypothetical protein TcasGA2_TC002110 [Tribolium castaneum] | 7.00e–30 | 7596 | 7159 | 436 | Y |

| EEZ99596.1 | hypothetical protein TcasGA2_TC002110 [Tribolium castaneum] | 3.00e–17 | 7907 | 7542 | 364 | Y |

| XP_001602535.2 | hypothetical protein LOC100118603 [Nasonia vitripennis] | 1.00e–33 | 15195 | 14575 | 619 | Y |

| AGD80173.1 | Alpha-latrotoxin (Steatoda grossa) | 0.0 | 18794 | 22972 | 4179 | N |

| EJY57592.1 | AAEL017053-PA [Aedes aegypti] | 8.00e–11 | 23965 | 23798 | 166 | N |

| AAN87269.1 | ORF [Drosophila melanogaster] | 4.00e–08 | 24578 | 24465 | 112 | Y |

| EFA02763.1 | hypothetical protein TcasGA2_TC008496 [Tribolium castaneum] | 5.00e–26 | 24917 | 24633 | 283 | Y |

| WP_006706426.1 | Pao retrotransposon peptidase protein, partial [Candidatus Regiella insecticola] | 4.00e–39 | 25890 | 25456 | 433 | Y |

| XP_003245995.1 | hypothetical protein LOC100570266 [Acyrthosiphon pisum] | 2.00e–31 | 26481 | 26002 | 478 | Y |

| EFA13346.1 | hypothetical protein TcasGA2_TC002325 [Tribolium castaneum] | 1.00e–32 | 26956 | 26504 | 451 | Y |

| XP_003699175.1 | uncharacterized protein LOC100874762 [Megachile rotundata] | 1.00e–10 | 27862 | 27305 | 556 | Y |

| XP_002012451.1 | GI14275 [Drosophila mojavensis] | 8.00e–10 | 28257 | 27931 | 325 | N |

| CAA35587.1 | unnamed protein product [Drosophila melanogaster] | 8.00e–59 | 30831 | 29839 | 991 | Y |

| AAX07244.1 | reverse transcriptase [Liobuthus kessleri] | 3.00e–23 | 31174 | 30812 | 361 | Y |

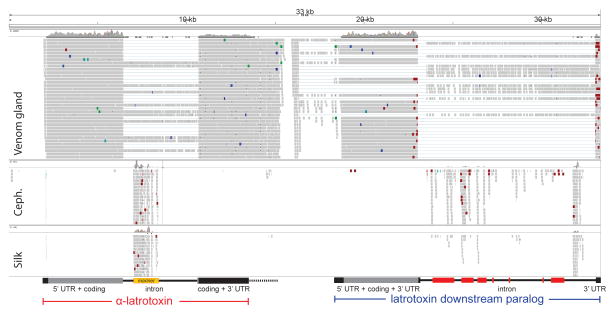

Mapping of L. hesperus RNA-Seq data [19] with Tophat to the insert indicated that both latrotoxin genes are highly transcribed in venom glands (Figure 1), with Cufflinks venom gland FPKM (fragments per kilobase per million library reads) of 80157 for α-latrotoxin and 81563 for the downstream paralog. FPKM in cephalothorax and silk glands was far lower for both latrotoxins (α-latrotoxin: cephalothorax=1318, silk glands=1442; downstream paralog: cephalothorax=76, silk glands=0).

Figure 1.

Mapping of RNA-Seq data to the 33 kb L. hesperus genomic reference sequence showing strong venom gland specific expression of tandem latrotoxin paralogs. Top ruler shows location in the reference sequence. Representative reads from the L. hesperus venom gland (top panel), cephalothorax (middle) and silk gland (bottom) RNA-seq libraries are shown mapped to the reference using Tophat with visualization in IGV. Reads mapping across intron boundaries are connected by thin lines and show location of splice junctions. At the bottom the gene structure of the two latrotoxins encoded by the fosmid sequence as determined by Cufflinks is diagrammed. In exonic regions, coding sequences are in gray, UTRs in black. The dashed line indicates the extended 3′ UTR region predicted by the Trinity assembled transcript. The position of the mariner element is indicated in the α-latrotoxin intron, and the RepeatMasker predicted retrotransposon positions are indicated in red in the intron of the downstream paralog.

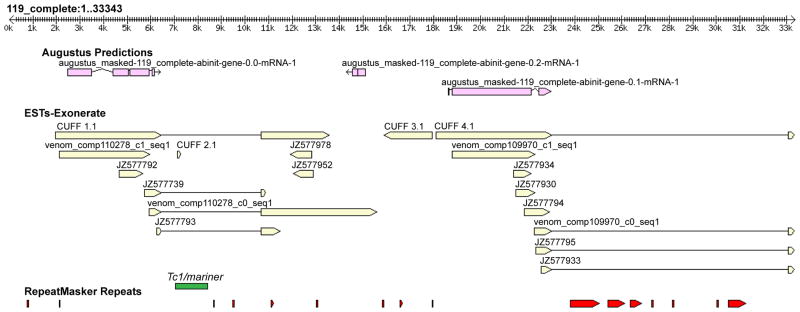

Venom gland RNA-Seq and EST evidence revealed one 4241 bp phase 1 intron in α-latrotoxin’s 25th codon from the stop codon and a 10,005 bp intron in the 3′ UTR of the adjacent latrotoxin (Figures 1–2, Table 2). The Cufflinks α-latrotoxin transcript had a 4257 bp coding region, a 316 bp 5′ UTR and a 2805 bp 3′UTR (Table 2). The Trinity α-latrotoxin transcripts consisted of two overlapping (by 25 bp) fragments, one with a 150 bp 5′UTR and the other with a 4828 bp 3′UTR. The downstream paralog’s Cufflinks transcript contained a 4182 bp coding region, which was collinear with the genomic sequence, indicating no intron interrupting the coding region. The Cufflinks transcript for this locus had a 675 bp 5′ UTR and a 341 bp 3′ UTR flanking the 10,005 bp intron located 57 bp into the 3′UTR. The Trinity transcripts comprised two overlapping (by 25 bp) fragments, which lacked the first 10 bp of coding sequence, and with the downstream transcript 6 bp shorter than the Cufflinks transcript, but agreeing in intron position. A single bp insertion in the Trinity transcript produced a frameshift and premature truncation, but mapped reads suggested its incorrect assembly. The end of α-latrotoxin’s 3′ UTR and the putative transcription start site of the adjacent latrotoxin were separated by 4545 or 2522 bp, depending if the Cufflinks or Trinity α-latrotoxin was considered. The MAKER annotation also supported two tandem latrotoxin paralogs, but Augustus gene predictions suggested multiple introns in both paralogs, disagreeing with the transcript evidence (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

MAKER-annotated L. hesperus genomic sequence illustrating latrotoxin introns containing transposable elements. The top annotation track shows Augustus predicted gene structure. The middle track shows alignments of RNA-Seq assembled transcripts and ESTs to the fosmid (Cufflinks assembled transcripts labeled with prefix “CUFF”, Trinity assembled transcripts labeled with prefix “venom_comp”, all other sequences are L. hesperus venom gland ESTs labeled with their GenBank Accession numbers), while the bottom section shows repeat regions identified by RepeatMasker (all features annotated in this track from 0–19 kb are simple repeat/low complexity regions; features between 22 kb–32 kb are retrotransposon fragments). The position of the putative Tc1/mariner family transposon not predicted by RepeatMasker is shown in green.

Table 2.

Locations of latrotoxin gene features in the L. hesperus genomic insert sequence. In cases where the predicted length of a feature varies when measured using the Trinity predicted transcript or the Cufflinks predicted transcript, both values are shown. The shaded portion gives values for the upstream α-latrotoxin locus, the unshaded for the downstream latrotoxin paralog.

| Feature | Start | End | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5′ UTR exon (Cufflinks) | 1955 | 2270 | 316 |

| 5′ UTR exon (Trinity) | 2121 | 2270 | 150 |

| Coding exon | 2271 | 6450 | 4180 |

| Intron | 6451 | 10691 | 4241 |

| Coding exon | 10692 | 10768 | 77 |

| 3′ UTR exon (Cufflinks) | 10769 | 13573 | 2805 |

| 3′ UTR exon (Trinity) | 10769 | 15596 | 4828 |

| 5′ UTR exon | 18119 | 18793 | 675 |

| Coding exon | 18794 | 22975 | 4182 |

| 3′ UTR exon | 22976 | 23032 | 57 |

| Intron | 23033 | 33037 | 10005 |

| 3′ UTR exon (Cufflinks) | 33038 | 33321 | 284 |

| 3′ UTR exon (Trinity) | 33038 | 33315 | 278 |

3.2. Latrotoxin Transposable Elements

RepeatMasker identified seven transposable elements (TEs) from 68 to 1215 bp in the 3′ UTR intron of the downstream latrotoxin. Five belong to the Pao retrotransposon family and two were long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs) in the Jockey retrotransposon family (Figure 2, Table 3). Most getORF proteins had significant BLAST hits to TEs (Tables 1, 3). These elements, or closely related copies, showed high expression in silk and cephalothorax tissues, but not in venom glands (Supplementary Materials, Table 2).

Table 3.

Repeats found in the L. hesperus genomic insert sequence. For simple repeats the repeat motif is shown. All repeats were identified by RepeatMasker with the exception of the putative Tc1/mariner superfamily DNA transposon (shaded row) identified as discussed in the text.

| Repeat Class/Family | Position in insert sequence | Matching repeat | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Begin | End | ||

| Simple Repeat/ Low complexity | 765 | 806 | (ATTTA)n |

| 2102 | 2143 | (A)n | |

| 8662 | 8691 | (AG)n | |

| 9476 | 9532 | (ATTTT)n | |

| 11119 | 11213 | (TATTAAT)n | |

| 13027 | 13076 | A-rich | |

| 15841 | 15890 | (TTA)n | |

| 16588 | 16656 | A-rich | |

| 17928 | 17978 | (TAATTTT)n | |

| LTR/Pao/BEL | 23817 | 25031 | |

| 25415 | 26100 | ||

| 26331 | 26839 | ||

| 27242 | 27324 | ||

| 28119 | 28193 | ||

| LINE/Jockey | 30008 | 30075 | |

| 30515 | 31256 | ||

| Tc1/mariner | 7011 | 8435 | |

A putative TE not detected by RepeatMasker was located within the α-latrotoxin intron. BLASTn of this intron found significant hits to L. hesperus genomic sequences surrounding the dragline silk MaSp1 and MaSp2 encoding genes. The top BLASTn hit was to two different regions (1304 or 1429 bp at 92% identity) of a MaSp2 containing clone (EF595245) from the library used in this study [18]. A 652 bp BLASTn match was found to a different L. hesperus genomic region from a MaSp1 containing clone (EF595246). A Cufflinks transcript for this TE in α-latrotoxin’s intron (positions 7014–8433), or closely related copies, had much higher expression in silk glands and cephalothorax than in venom glands (FPKM: venom gland=1447, cephalothorax=304868, silk gland=838794). BLASTx of this transcript to NCBI revealed homology to transposases of the Tc1/mariner DNA transposon superfamily [37], in agreement with getORF predictions (Table 1). EMBOSS einverted found 41 bp inverted repeats flanking coordinates 7011–8435, indicating the mariner-like transposon in the intron in α-latrotoxin is 1425 bp.

3.3. Latrotoxin Regulatory Elements

Twenty-nine promoters were predicted in the 33 kb insert (Supplementary Materials, Table 3), with a score ≥ 0.95. None were within 600 bp of a TSS (defined by transcript termini). When run on 5′ UTRs, 3′ UTRs, or putative promoters upstream of TSS, Pipmaker found no conserved regions between latrotoxin paralogs. Several TF binding sites were predicted by Match 1.0 in the introns of both paralogs, but their orientation was opposite of latrotoxin genes, and functions of the TFs binding these sites had no obvious connection to venom production (Table 4).

Table 4.

Transcriptional regulatory protein binding sites identified in latrotoxin introns using Match 1.0. Shown are position within intron sequence, orientation, name and functional information.

| Position | Strand | Name | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| 563 | - | CF2-II | Late activator in follicle cells during chorion formation |

| 2463 | - | BR-C Z1 | Ecdysone response during metamorphosis |

| 2842 | - | BR-C Z4 | Ecdysone response during metamorphosis |

| 3930 | - | BR-C Z4 | Ecdysone response during metamorphosis |

| 895 | - | Elf-1 | Epidermal differentiation |

| 4447 | - | Croc | Head development |

| 4664 | - | BR-C Z1 | Ecdysone response during metamorphosis |

UTRscan predicted upstream open reading frames (uORFs) in the 5′ UTRs of both latrotoxin transcripts, an internal ribsosome entry site (IRES) in the 5′ UTR of α-latrotoxin, and musashi binding elements (MBEs) in the 5′ UTR of the downstream latrotoxin (Supplementary Materials, Table 4). The 3′ UTR from the Cufflinks α-latrotoxin contained multiple MBEs, with additional MBEs and a Brd-Box motif in the longer 3′ UTR from the Trinity transcript. Both α-latrotoxin transcript 3′ UTRs terminated in a predicted polyadenylation signal, suggesting possible alternative transcripts with different 3′ UTRs. The Cufflinks 3′ UTR of the downstream latrotoxin gene had one predicted terminal polyadenylation site.

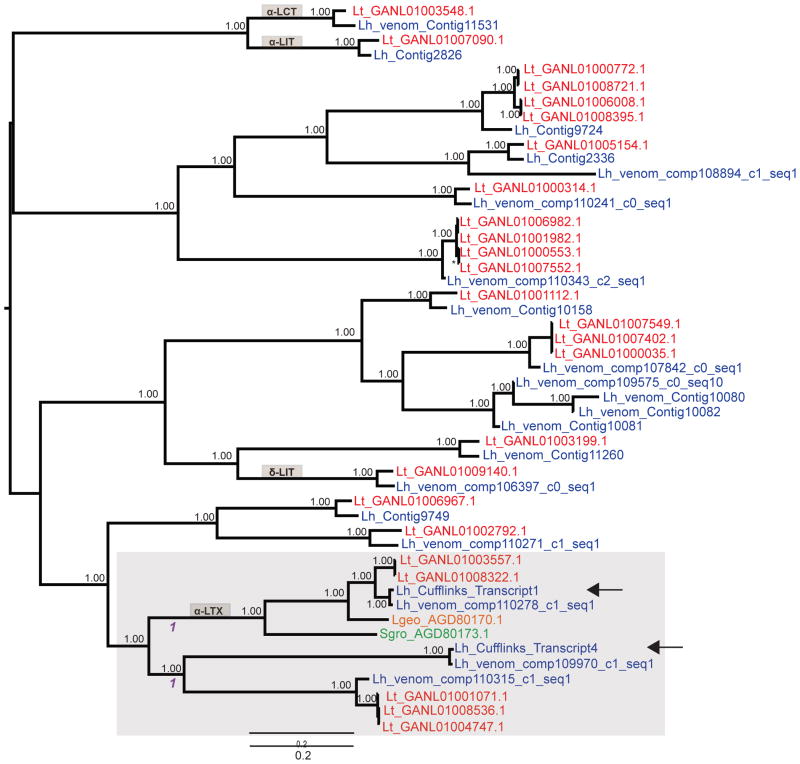

3.4. Latrotoxin Family Evolution

Most latrotoxins from L. hesperus group in highly supported clades with orthologs from L. tredecimguttatus, with five exceptions, including the paralog adjacent to α-latrotoxin (Figure 3). The adjacent latrotoxin genes are closely related, but not sister paralogs, with α-latrotoxin’s downstream paralog being more closely related to another paralog. The Cufflinks-translated L. hesperus α-latrotoxin falls within a clade of orthologs. A test for sites evolving under positive selection using all latrotoxins (M7 vs. M8: 2 Δ lnL=9.113; df=2; p=0.0104) was significant, with an additional M8 category of sites with an average dN/dS of 1.618. However, no sites had a posterior probability > 0.592 in the site class under positive selection. A branch-site test was applied specifically to two branches subsequent to the duplication event separating α-latrotoxin from the downstream paralog (Figure 3), and a model allowing for positive selection on these branches was a better fit to the data (MA vs. MAω2=1: 2 Δ lnL=14.219; df=1; p= 0.0001), with two codons (389 and 886) having a posterior probability > 0.95 of dN/dS > 1. MEME indicated 9 codons under positive selection, with most clustered towards the C-terminus of the latrotoxin protein (Supplementary Material).

Figure 3.

Evolutionary relationships of latrotoxin paralogs indicating the relatively recent duplication of tandem latrotoxins. Shown is a midpoint rooted Bayesian phylogenetic tree of latrotoxin proteins. Numbers at nodes indicate clade posterior probabilities (PP). The node marked by an asterisk has a PP of 1.00. Sequences from L. tredecimguttatus are in red and L. hesperus in blue; sequences from L. geometricus and S. grossa are in orange or green, respectively. Arrows indicate the tandem sequences assembled by Cufflinks from this study. All other L. hesperus and L. tredecimguttatus sequences were from de novo assembly of RNA-Seq reads. Shaded beige boxes label clades that contain a functionally characterized paralog. The larger gray shaded clade contains the two genomic insert latrotoxins and more closely related sequences, including all α-latrotoxins. Branches tested for sites under positive selection are indicated by the number 1 in purple text.

4. Discussion

Characterization of 33 kb of the Western black widow (L. hesperus) genome revealed the complete α-latrotoxin gene and a divergent closely related paralogous locus, and both are highly expressed in venom glands at similar levels. These loci represent two of ≥ 20 potential L. hesperus latrotoxin genes with venom-gland specific expression [16]. These adjacent paralogs occur 4.5 kb apart, providing evidence of a tandem gene duplication. Both latrotoxin loci encode large proteins, but contrary to previous findings in L. tredecimguttatus [38], introns are present in their coding sequence or 3′ UTR. The latrotoxin coding and 3′ UTR introns are approximately 5x and 7.5x the average length of introns from corresponding regions in Drosophila melanogaster [39]. However, these introns are similar to average lengths recently reported from spider genomes [40]. While energetically costly to transcribe [41], introns can increase gene expression when they contain regulatory enhancers, or by direct interaction of the transcriptional and spliceosomal machinery [42].

Latrotoxin UTRs have several predicted regulatory sequences that may function in post-transcriptional regulation. The musashi mRNA binding protein exerts translational control and modulates cell division and cell cycle progression [43], and the multiple UTR musashi binding elements predicted in both latrotoxins may regulate their expression. Haney et al. [16] reported a protein with a significant BLAST hit to a putative RNA-binding musashi protein among 695 L. hesperus venom gland specifically expressed transcripts, with venom gland biased expected read counts per million reads among tissues (cephalothorax=54.64; silk=5.9; venom=2647.02), supporting the role of MBEs in latrotoxin regulation. Upstream ORFs were also predicted in the 5′ UTRs of both paralogs, which may modulate expression through effects on translation efficiency [44]. Furthermore, the presence of a 3′UTR intron may target the downstream latrotoxin’s transcript to the nonsense mediated decay (NMD) pathway, greatly reducing translation [45]. In mammals, this typically occurs when the 3′ most exon-exon junction is >50–55 bp downstream of the stop codon [46], and the splice junction in the 3′ UTR of the downstream latrotoxin is 57 bp beyond the stop codon. Despite both genes being expressed at similar levels in venom glands, the downstream latrotoxin paralog was not identified in venom by mass spectrometry [16], consistent with its transcripts being targeted to the NMD pathway. While NMD has not been studied in arachnids, BLASTp of three components of this pathway (UPF1-3) from Homo sapiens to the L. hesperus transcriptome identified expressed homologs in spiders (e-values of best hits: UPF1 = 0.0; UPF2 = 0.0; UPF3 = 7e-58).

The latrotoxin paralogs have been subject to several transposable element (TE) insertions, mostly LTR retrotransposons belonging to the BEL/Pao family, and nonLTR retrotransposons of the Jockey family, both widespread in eukaryotic genomes and occurring within the downstream paralog’s 3′ UTR intron [47,48]. The identified TEs also exhibit tissue-specific expression, with much lower expression in the venom gland, relative to silk and cephalothorax tissues. A large TE was found in α-latrotoxin’s intron, with homology to the Tc1/mariner DNA transposon superfamily, which is amenable to interspecific horizontal transfer [37]. This transposon may have recently proliferated in the L. hesperus genome, as closely related sequences (up to 92% identity over 1400 bp) were identified in two other sequenced clones from this same genomic library, representing different loci [18]. Moreover, the mariner-like TE composes 33% of the length of α-latrotoxin’s intron, and its recent insertion may be linked to this intron’s origin [49,50]. Although a complete transposase ORF was not present in this TE, BLASTp of this sequence to the L. hesperus transcriptome reveals expressed transcripts encoding complete transposase, suggesting these mariner-like elements are actively transposing. While the intronless nature of other latrotoxins [38,51] is consistent with a recent origin of introns in L. hesperus latrotoxins, the methods used to identify introns in L. tredecimguttatus latrotoxins (PCR-RFLP [38]) may have missed small introns, or those outside coding regions.

Nearly all latrotoxin transcripts assembled from RNA-Seq data in L. hesperus had a closely related ortholog in L. tredecimguttatus (also assembled from RNA-Seq data), implying the latrotoxin gene family had diversified through numerous gene duplications in the most recent common ancestor of these two species or in an earlier ancestor. Yet the paralog downstream of α-latrotoxin did not appear to have an L. tredecimguttatus ortholog, suggesting it is either not evolutionarily conserved, is a recent duplicate for which the closely related paralog in L. hesperus was not sampled, or lacks or exhibits variable expression in L. tredecimguttatus. The adjacent latrotoxins are not sister paralogs, but occur in the same sub-clade, supporting recent duplication events via non-homologous crossing-over, and we expect that many other latrotoxins are clustered in the Latrodectus genome. While latrotoxins largely appear to be evolving under purifying selection, our analyses found limited evidence of positive selection on a few codons, suggesting the possible adaptive evolution of latrotoxins. Clearly, functional assays are needed to test the toxin activity of these recently described paralogs, which is currently unknown. The high level of sequence divergence between α-latrotoxin and its mostly closely related paralogs would suggest functional variability. While gene duplication and selection are implicated as important processes in venom evolution, as has been shown in spiders and other venomous taxa [52–55], functional data will add to our understanding of how these processes impact venom phenotypes.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

α-latrotoxin is a black widow venom toxin causing massive neurotransmitter release

Genomic and RNA-Seq data reveal α-latrotoxin’s gene and a tandem divergent paralog

Tandem latrotoxin paralogs are highly and specifically transcribed in venom glands

Latrotoxins have 4–10 kb introns containing multiple transposable elements

Latrotoxins are divergent in sequence and may be post-transcriptionally regulated

Acknowledgments

Rujuta Gadgil, Cheryl Hayashi, Caryn McCowan, and Alex Lancaster helped in data collection. This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health from grants 1F32GM83661-01 and 1R15GM097714-01 to JEG, and F32 GM78875-1A to NAA, and by the National Science Foundation (IOS-0951886 to NAA).

Abbreviations

- FPKM

fragments per kilobase per million library reads

- TE

transposable element

- LINE

long interspersed nuclear element

- MaSp

major ampullate silk protein

- TSS

transcription start site

- TF

transcription factor

- MBE

musashi binding element

- LTR

long terminal repeat

- NMD

nonsense mediated decay

- FDR

false discovery rate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Duda TF, Palumbi SR. Molecular genetics of ecological diversification: duplication and rapid evolution of toxin genes of the venomous gastropod Conus. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:6820–6823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fry BG. From genome to “venome”: molecular origin and evolution of the snake venom proteome inferred from phylogenetic analysis of toxin sequences and related body proteins. Genome Res. 2005;15:403–420. doi: 10.1101/gr.3228405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moura-da-Silva A, Paine MI, Diniz MV, Theakston RD, Crampton J. The molecular cloning of a phospholipase A2 from Bothrops jararacussu snake venom: evolution of venom group II phospholipase A2’s may imply gene duplications. [Accessed 4 April 2014];J Mol Evol. 1995 41:174–179. doi: 10.1007/BF00170670. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/BF00170670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whittington CM, Papenfuss AT, Locke DP, Mardis ER, Wilson RK, et al. Novel venom gene discovery in the platypus. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R95. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-9-r95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Escoubas P, Quinton L, Nicholson GM. Venomics: unravelling the complexity of animal venoms with mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2008;43:279–295. doi: 10.1002/jms.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ushkaryov YA, Volynski KE, Ashton AC. The multiple actions of black widow spider toxins and their selective use in neurosecretion studies. Toxicon. 2004;43:527–542. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pineda SS, Wilson D, Mattick JS, King GF. The lethal toxin from Australian funnel-web spiders is encoded by an intronless gene. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e43699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He Q, Duan Z, Yu Y, Liu Z, Liu Z, et al. The venom gland transcriptome of Latrodectus tredecimguttatus revealed by deep sequencing and cDNA library analysis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e81357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y, Chen J, Tang X, Wang F, Jiang L, et al. Transcriptome analysis of the venom glands of the Chinese wolf spider Lycosa singoriensis. Zoology. 2010;113:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.zool.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiyatkin NI, Dulubova IE, Chekhovskaya IA, Grishin EV. Cloning and structure of cDNA encoding α-latrotoxin from black widow spider venom. FEBS Lett. 1990;270:127–131. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81250-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krasnoperov VG, Shamotienko OG, Grishin EV. Isolation and properties of insect-specific neurotoxins from venoms of the spider Latrodectus mactans tredecimguttatus. Bioorg Khim. 1990;16:1138–1140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashton AC. alpha-Latrotoxin, acting via two Ca2+-dependent pathways, triggers exocytosis of two pools of synaptic vesicles. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44695–44703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108088200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orlova EV, Rahman MA, Gowen B, Volynski KE, Ashton AC, et al. Structure of alpha-latrotoxin oligomers reveals that divalent cation-dependent tetramers form membrane pores. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:48–53. doi: 10.1038/71247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ushkaryov YA, Petrenko AG, Geppert M, Sühof TC. Neurexins: synaptic cell surface proteins related to the alpha-latrotoxin receptor and laminin. Science. 1992;257:50–56. doi: 10.1126/science.1621094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garb JE, Hayashi CY. Molecular evolution of alpha-Latrotoxin, the exceptionally potent vertebrate neurotoxin in black widow spider venom. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:999–1014. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haney RA, Ayoub N, Clarke TH, Hayashi CY, Garb JE. Dramatic expansion of the black widow toxin arsenal uncovered by multi-tissue transcriptomics and venom proteomics. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:366. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gregory TR, Shorthouse DP. Genome sizes of spiders. J Hered. 2003;94:285–290. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esg070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ayoub NA, Garb JE, Tinghitella RM, Collin MA, Hayashi CY. Blueprint for a high-performance biomaterial: full-length spider dragline silk genes. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clarke TH, Garb JE, Hayashi CY, Haney RA, Lancaster AK, et al. Multi-tissue transcriptomics of the black widow spider reveals expansions, co-options, and functional processes of the silk gland gene toolkit. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:365. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, Levin JZ, Thompson DA, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorvaldsdottir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform. 2013;14:178–192. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Min XJ, Butler G, Storms R, Tsang A. OrfPredictor: predicting protein-coding regions in EST-derived sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W677–W680. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCowan C, Garb JE. Recruitment and diversification of an ecdysozoan family of neuropeptide hormones for black widow spider venom expression. Gene. 2014;536:366–375. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.11.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cantarel BL, Korf I, Robb SMC, Parra G, Ross E, et al. MAKER: an easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed for emerging model organism genomes. Genome Res. 2008;18:188–196. doi: 10.1101/gr.6743907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smit AFA, Hubley R, Green P. RepeatMasker Open-3.0. 2010 Available: http://www.repeatmasker.org.

- 28.Reese MG. Application of a time-delay neural network to promoter annotation in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Comput Chem. 2001;26:51–56. doi: 10.1016/s0097-8485(01)00099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matys V, Kel-Margoulis OV, Fricke E, Liebich I, Land S, et al. TRANSFAC(R) and its module TRANSCompel(R): transcriptional gene regulation in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D108–D110. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grillo G, Turi A, Licciulli F, Mignone F, Liuni S, et al. UTRdb and UTRsite (RELEASE 2010): a collection of sequences and regulatory motifs of the untranslated regions of eukaryotic mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D75–D80. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwartz S, Zhang Z, Frazer KA, Smit A, Riemer C, et al. PipMaker-a web server for aligning two genomic DNA sequences. Genome Res. 2000;10:577–586. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.4.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papadopoulos JS, Agarwala R. COBALT: constraint-based alignment tool for multiple protein sequences. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1073–1079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suyama M, Torrents D, Bork P. PAL2NAL: robust conversion of protein sequence alignments into the corresponding codon alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W609–612. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murrell B, Wertheim JO, Moola S, Weighill T, Scheffler K, et al. Detecting individual sites subject to episodic diversifying selection. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plasterk RH, Izsvák Z, Ivics Z. Resident aliens: the Tc1/mariner superfamily of transposable elements. Trends Genet TIG. 1999;15:326–332. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01777-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Danilevich VN, Grishin EV. The chromosomal genes for black widow spider neurotoxins do not contain introns. Bioorg Khim. 2000;26:933–939. doi: 10.1023/a:1026666606311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hong X, Scofield DG, Lynch M. Intron size, abundance, and distribution within untranslated regions of genes. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:2392–2404. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanggaard KW, Bechsgaard JS, Fang X, Duan J, Dyrlund TF, et al. Spider genomes provide insight into composition and evolution of venom and silk. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3765. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castillo-Davis CI, Mekhedov SL, Hartl DL, Koonin EV, Kondrashov FA. Selection for short introns in highly expressed genes. Nat Genet. 2002;31:415–418. doi: 10.1038/ng940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Le Hir H, Nott A, Moore MJ. How introns influence and enhance eukaryotic gene expression. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:215–220. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MacNicol MC, Cragle CE, MacNicol A. Context-dependent regulation of Musashi-mediated mRNA translation and cell cycle regulation. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:39–44. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.1.14388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mignone F, Gissi C, Liuni S, Pesole G. Untranslated regions of mRNAs. Genome Biol. 2002;3:REVIEWS0004. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-3-reviews0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baker KE, Parker R. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: terminating erroneous gene expression. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bicknell AA, Cenik C, Chua HN, Roth FP, Moore MJ. Introns in UTRs: why we should stop ignoring them. BioEssays. 2012;34:1025–1034. doi: 10.1002/bies.201200073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De la Chaux N, Wagner A. BEL/Pao retrotransposons in metazoan genomes. BMC Evol Biol. 2011;11:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Glushkov S, Novikova O, Blinov A, Fet V. Divergent non-LTR retrotransposon lineages from the genomes of scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpiones) Mol Genet Genomics. 2006;275:288–296. doi: 10.1007/s00438-005-0079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Purugganan MD. Transposable elements as introns: evolutionary connections. Trends Ecol Evol. 1993;8:239–243. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(93)90198-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roy SW. The origin of recent introns: transposons? Genome Biol. 2004;5:251. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-12-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Danilevich VN, Luk’ianov SA, Grishin EV. Cloning and structure of gene encoded alpha-latrocrustoxin from the black widow spider venom. Bioorg Khim. 1999;25:537–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Casewell NR, Wagstaff SC, Harrison RA, Renjifo C, Wuster W. Domain loss facilitates accelerated evolution and neofunctionalization of duplicate snake venom metalloproteinase toxin genes. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2637–2649. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chang D, Duda TF. Extensive and continuous duplication facilitates rapid evolution and diversification of gene families. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:2019–2029. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vonk FJ, Casewell NR, Henkel CV, Heimberg AM, Jansen HJ, et al. The king cobra genome reveals dynamic gene evolution and adaptation in the snake venom system. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:20651–20656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314702110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Binford GJ, Bodner MR, Cordes MHJ, Baldwin KL, Rynerson MR, et al. Molecular evolution, functional variation, and proposed nomenclature of the gene family that includes sphingomyelinase D in sicariid spider venoms. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:547–566. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.