Abstract

Objectives

Survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) varies between communities, due in part to variation in the methods of measurement. The Utstein template was disseminated to standardize comparisons of risk factors, quality of care and outcomes in patients with OHCA. We sought to assess whether OHCA registries are able to collate common data using the Utstein template. A subsequent study will assess whether the Utstein factors explain differences in survival between emergency medical services (EMS) systems.

Study design

Retrospective study.

Setting

This retrospective analysis of prospective cohorts included adults treated for OHCA, regardless of the etiology of arrest. Data describing the baseline characteristics of patients, and the process and outcome of their care were grouped by EMS system, de-identified then collated. Included were core Utstein variables and timed event data from each participating registry. This study was classified as exempt from human subjects’ research by a research ethics committee.

Measurements and Main Results

Twelve registries with 265 first-responding EMS agencies in 14 countries contributed data describing 125,840 cases of OHCA. Variation in inclusion criteria, definition, coding, and process of care variables were observed. Contributing registries collected 61.9% of recommended core variables and 42.9% of timed event variables. Among core variables, the proportion of missingness was mean 1.9 ± 2.2%. The proportion of unknown was mean 4.8 ± 6.4%. Among time variables, missingness was mean 9.0 ± 6.3%.

Conclusions

International differences in measurement of care after OHCA persist. Greater consistency would facilitate improved resuscitation care and comparison within and between communities.

Keywords: cardiac arrest, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, Utstein template, resuscitation, epidemiology

Introduction

Survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) varies widely between communities.(1) These differences reflect differences in the distribution of patient risk factors and severity of disease; the structure and function of emergency medical services (EMS); and the method of measuring the process and outcome of care. Experts developed and disseminated the Utstein template to standardize methods of measuring care for patients with OHCA to improve the comparability within and between communities of reports of risk factors, quality of care and outcomes after OHCA.(4, 5)

Some communities change care processes (e.g., changes in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) or use of induced hypothermia), then report improved outcomes after OHCA.(6-11) Whether this relationship is causal is unclear because of potential secular changes in the method of measuring care. Since health care resources are limited, knowledge of which processes contribute to improved survival is essential before dissemination and adoption of these changes. Thus, knowledge of the validity of methods of reporting resuscitation outcomes would enhance understanding of how to improve them within and between communities.

The latest Utstein template has had limited empiric validation. A North American study reported that variation in survival rates between sites participating in a clinical research network were incompletely explained by the Utstein factors.(12) As well, European regions reported a high rate of missingness for key Utstein variables.(13) The objective of this study was to describe international variation in the structure and function of OHCA registries. We hypothesized that there would be no differences in which variables were collected or complete.

Materials and Methods

Design

This study was a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected cohorts of data describing the process and outcome of care for patients with OHCA in catchment areas served by participating OHCA registries.

Population

Included were registries that enrolled adults with OHCA alone, or adults and children with OHCA who received attempted resuscitation by application of chest compressions by EMS personnel or defibrillation by bystanders or EMS personnel regardless of the etiology of arrest.(14) OHCA was defined as the cessation of cardiac mechanical activities as confirmed by the absence of signs of circulation.

Although the Utstein template recommends inclusion of patients assessed but not treated by EMS providers for OHCA, such data were not collated for this study because such patients have a poor prognosis and our ultimate objective was to assess whether the Utstein factors explain differences in survival. Cases with OHCA due to traumatic injury were collated but in-hospital cardiac arrest were not.

Subjects were grouped within each registry by EMS system. This was defined as one-tier or two-tier EMS response under a single administrative structure. For example, two EMS agencies that provide advanced life support response to the same geographic area with separate administrative oversight were considered separate systems. Conversely, EMS providers that serve a large geographic area with a single administrative structure were considered a single system. Single-tier response usually has paramedic, nurse or physician providers capable of advanced life support (ALS) including CPR, defibrillation, advanced airway insertion, intravenous insertion, and drug administration; or intermediate life support (ILS) including CPR, defibrillation, as well as advanced airway insertion or limited intravenous insertion or drug administration. Two-tier response usually has emergency medical technicians (EMTs) capable of CPR or defibrillation as well as ALS-capable providers.

Data Sources

Individuals affiliated with known registries that describe the process and outcome of care for patients with OHCA were invited to contribute de-identified data and participate in the interpretation of the results of the pooled data analysis. Included were registries with pre-existing ‘population-based’ cohorts of patients OHCA, at least one prior peer-reviewed publication, and collected data during at least one year since 2005. This cutoff was selected because it was one year after publication of the last update to the Utstein template.(5) Excluded were registries unable to provide individual patient data, or without survival data, or with self-reported lack of compliance with the 2004 Utstein template. Some of the raw data submitted by registries had previously been published by individual registries.

Data Collection

All core variables and timed event data recommended by the Utstein-style guidelines were sought from each registry.(13) Each registry provided an itemized list of which variables were collected and how these were coded to facilitate pooling. Patient-level data previously abstracted locally were de-identified then transmitted to the analysis center using secure and confidential methods.

Variables

Utstein core variables included: age (in years), sex, location of arrest, witnessed status, presumed cause of arrest, resuscitation attempt by EMS personnel, bystander CPR, chest compression, first recorded rhythm (shockable or non-shockable), defibrillation attempt (before or after EMS arrival), assisted ventilation, resuscitation drug use, return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) before ED arrival, or ROSC sustained to ED arrival, hospital admission, vital status at discharge or one month after index arrest, and neurological status at discharge. Although the last Utstein template did not indicate which resuscitation drug to evaluate, we characterized use of epinephrine as it is the drug most commonly used during attempted resuscitation.(15)

Time variables included: dates of arrest, discharge or death; as well as time of witnessed/monitored arrest, call receipt, first rhythm analysis/assessment of need for CPR, first CPR attempts, and first defibrillation attempt if shockable rhythm.

We sought to distinguish between “unknown” and missing data. For example, if providers did not record whether bystander CPR was performed, some registries interpret the patient as not having received CPR. Others combine “not observed” and “unknown” into a single response.

We sought limited information not included in the template but known to be important. First, erroneous time documentation of emergency treatment caused by variation in the accuracy of timepieces is common, of large magnitude, and limits reconstruction of events for quality improvement and research.(16) Although the template does not recommend synchronization of monitor/defibrillators with atomic clocks, we elicited whether participating EMS agencies periodically did so.

We were aware from prior work related to an acute coronary syndrome registry that patients not enrolled in a registry had higher risk, receive poorer quality of care and have a higher mortality than those who were enrolled.(17) Therefore we elicited whether each registry periodically monitored for missing cases, and whether remediation was performed if missing cases were identified.

Statistical Analysis

The availability of each variable and its proportion of unknown as well as missingness in each registry were summarized descriptively. Mean rates were calculated within each registry as a unit. Overall means were calculated across all registries.

Ethical Approval

All personal health information was removed by each registry’s staff before transmission of data to the analytic center. The University of Washington Institutional Review Board classified this study as exempt from human subject research.

Results

Of 28 registries invited to participate, four did not respond to the invitation, one lacked data beyond 2005, five lacked survival outcomes, and five declined to participate. Twelve registries (42.9% of invited) contributed data. These represented 265 EMS agencies in 14 countries (Figure 1). In total, 125,840 cases of OHCA were included (Table 1). Some participating regions could not provide data from throughout the study enrollment period of interest because of ethical, administrative, or technical issues (Table 1).

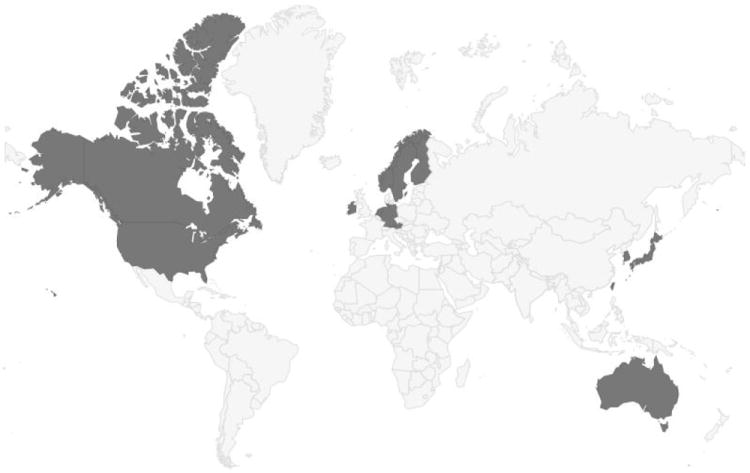

Figure 1.

Countries of Origin of Included Registries

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Included Utstein-Style Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Registries

| Registry | SJA-WA Cardiac Arrest Registry |

Victorian Ambulance Cardiac Arrest Registry |

CAVAS Project | Taipei OHCA Registry | Utstein Osaka Project | ROC | Irish OHCAR | ARREST | Oslo and Akershus Registry |

Swedish Register of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation |

Helsinki Cardiac Arrest Registry |

VICAR | German Resuscitation Registry |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Australia | Australia | Korea | Taiwan | Japan | US | Canada | Republic of Ireland | Netherlands | Norway | Sweden | Finland | Austria | Germany |

| Region | Perth, WA | Victoria | Seoul | Taipei | Osaka | Portland, OR San Diego, CA Dallas, TX Birmingham, AL Pittsburgh, PA Milwaukee, WI | Vancouver, BC Toronto, ON Ottawa, ON | Republic of Ireland | Noord-Holland | Oslo | Sweden | Helsinki | Vienna | Worms Sigmaringen Lübeck Göppingen Lüneburg Gütersloh Dortmund Münster |

| EMS Agency (No.) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 33 | 210a | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8b | |

| Catchment Population | 1.7 million | 5.6 million | 9.8 million | 2.7 million | 8.8 million | 21.0 million | 4.6 million | 2.4 million | 0.6 million | 9.4 million | 0.6 million | 1.7 million | 2.1 million | |

| Year Registry Started | 1996 | 1999 | 2007 | 2004 | 1998 | 2005 | 2007 | 2005 | 2003 | 1990 | 1994 | 2009 | 1998 | |

| Estimated Annual Cases (no.) | 1,600 | 4,500 | 3,500 | 3,000 | 6,000 | 11,000 | 1,700 | 1,300 | 250 | 4,900 | 360 | 3,500 | 1,100 | |

| Tiered Response | One-tier ALS | Two-tier BLS-D and ALS | One-tier intermediate life support | Two-tier BLS-D and ALS | One-tier intermediate life support | Two-tier BLS-D and ALS | Two-tier BLS-D and ALS, or two-tier BLS-D and BLS-D | Two-tier BLS-D and ALS | One-tier ALS | One-tier ALS | One-tier ALS | Two-tier BLS-D and ALS | Two-tier ALS | Two-tier ALS |

| Include | OHCA assessed or treated by EMS or defibrillated by laypersons | OHCA assessed or treated by EMS or defibrillated by laypersons | OHCA assessed or treated by EMS or defibrillated by lay persons | OHCA assessed or treated by EMS | OHCA treated by EMS or defibrillated by laypersons | OHCA assessed or treated by EMS or defibrillated by lay persons | OHCA assessed or treated by EMS or deifbrillated by lay persons | OHCA assessed or treated by EMS or defibrillated by laypersons, or figher fighter/police | Adults with OHCA treated by EMS or defibrillated by laypersons | OHCA treated with chest compression or defibrillation by EMS or laypersons | OHCA assessed or treated by EMS or defibrillated by lay persons | OHCA assessed or treated by EMS or defibrillated by lay personsc | OHCA treated by EMS or defibrillated by laypersons | |

| Exclude Traumatic Arrests | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Periodically Synchronize Time Clocks | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Periodically Audit for Missing Cases | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Remediate if Missing Cases Identified | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cases Included in Analysis (no.) | 2,330 | 8,873 | 8,522 | 2,996 | 37,569 | 40,263 | 2,000 | 5,631 | 775 | 9,345 | 1,367 | 1,448 | 4,721 | |

| Year(s) of Episodes Included | 2006-2010 | 2007-2010 | 2008-2010 | June, 2010-2011 | 2005-2010 | 2005-2010 | 2007-2011 | 2006-2010 | 2005-April, 2008 | 2010-2011 | 2005-2010 | 2009-2010 | 2005-2010 | |

OHCA denotes out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; EMS, emergency medical services; ALS, advanced life support; BLS, basic life support; BLS-D, basic life support plus defibrillation.

Among 264 EMS agencies, 210 agencies were included in this study.

Among 139 EMS agencies, 8 agencies were included in this study.

Inclusion Criteria

Variation in inclusion criteria was reported (Table 1). Seven (58.3%) registries enrolled patients with OHCA assessed or treated by EMS personnel or defibrillated by laypersons. Five (41.7%) only included patients with OHCA treated by EMS personnel. Eleven (91.7%) included those treated with an automated external defibrillator (AED) by laypersons before arrival of EMS personnel on scene. One (8.3%) collated such cases separately. One (8.3%) did not collect such data because of the small number of AEDs in a public place within the registry’s catchment area.

Core Variables

All registries collected the following core variables (Table 2): age, gender, location of arrest, witnessed status, cause of arrest, bystander CPR status, performance of chest compressions, first monitored rhythm, attempted defibrillation, survival to hospital discharge or one month survival, and neurological status at discharge from hospital. Three (25%) described EMS and bystander witnessed status using separate variables. Ten (83.3%) collected EMS and bystander witnessed status as a single variable with multiple allowable responses. Three (25%) did not collect data on attempted ventilation, one (8.3%) did not collect data on defibrillation attempt before EMS arrival, and one (8.3%) did not collect data on epinephrine use. One (8.3%) did not characterize the occurrence of ROSC before ED, three (25%) ROSC at ED arrival, and three (25%) hospital admission. One (8.3%) collected etiology of arrest but did not transmit it because of a technical issue. Two (16.7%) collected neurological status at discharge but reported that they could not transmit it because of ethical issues.

TABLE 2.

Patient Characteristics, Care Process and Outcome Variables Collected

| Variable | Coding | SJA-WA Cardiac Arrest Registry |

Victorian Ambulance Cardiac Arrest Registry |

CAVAS project | Taipei OHCA Registry |

Utstein Osaka Project |

ROC | Irish OHCAR | ARREST | Oslo and Akershus Registry |

Swedish Register of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation |

Helsinki Cardiac Arrest Registry |

VICAR | German Resuscitation Registry |

Average Missingness or Unknown (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | |||

| Age | Missing, % | 0 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.7 | 2.2 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 5.2 | 0 | 1.1 | 0.1 | 1.0 | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Sex | 1=Male / 2=Female / 9=Unknown | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | ||

| Missing, % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.3 | 0.3 | ||

| Unknown, % | n/a | 0.05 | 0 | 0.1 | n/a | 0.1 | n/a | 0.12 | n/a | 0 | 0 | n/a | 0.02 | 0.0 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Location of arrest | 1=Home / 2=Public places 3=Other / 9=Unknown | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | ||

| Missing, % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.2 | ||

| Unknown, % | n/a | n/a | 5.9 | 0.07 | n/a | 0 | n/a | 0.02 | n/a | 0 | 0 | n/a | 0.8 | 1.0 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Arrest, Witnessed | 1=Witnessed/0=Not witnessed / 9=Unknown | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | ||

| Missing, % | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | ||

| Unknown, % | 0 | 0.4 | 10.1 | 0.2 | n/a | 5.5 | 5.1 | 1.4 | n/a | 4.9 | 0 | n/a | n/a | 3.1 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Type of Witness | 1=Witnessed by laypersons /2=Witnessed by EMS / 3=Others / 4=Not witness / 9=Unknown | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | ||

| Missing, % | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.1 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | ||

| Unknown, % | 0 | 0.4 | 12.8 | 5.3 | n/a | 5.5 | 7.2 | 1.8 | n/a | 21.9 | 0 | n/a | n/a | 6.1 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Etiology of Arrest | 1=Presumed cardiac etiology / 2=Trauma / 3=Respiratory / 4=Drowning / 5=Other / 9=Unknown | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected but not collated | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | ||

| Missing, % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.3 | 0 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20.8 | 2.3 | ||

| Unknown, % | 0 | 0 | 1.0 | 57.9 | 0.7 | 0 | n/a | 0.6 | n/a | 10.8 | 17.6 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 8.6 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Bystander CPR | 1=Yes / 0=No / 9=Unknown | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | ||

| Missing, % | 55.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.3 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.1 | 5.0 | ||

| Unknown, % | n/a | 3.5 | n/a | 1.4 | n/a | 7 | n/a | 2.3 | n/a | 46.5 | 0.7 | n/a | 0.1 | 8.8 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Chest compressions | 1=Yes / 0=No / 9=Unknown | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Not collected (All cases received compressions) | Collected | Collected | Not collected (All cases received compressions) | Not collected (All cases received compressions) | ||

| Missing, % | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | |||||

| Unknown, % | n/a | 0 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 0 | n/a | n/a | 0.2 | 0 | 0.1 | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| First monitored shockable/Non shockable rhythm | 1=VF or VT / 2=PEA / 3=Asystole / 4=Other / 9=Unknown | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | ||

| Missing, % | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.9 | 12.9 | 2.8 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 11.7 | 4.0 | 2.6 | ||

| Unknown, % | n/a | 0.9 | 16.2 | 16.6 | n/a | 2.2 | n/a | 3.2 | n/a | 12.8 | 0.7 | 3.7 | 1.2 | 6.4 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Defibrillation attempt before EMS arrival | 1=Yes / 0=No / 9=Unknown | Collected | Collected | Collected | Not collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | ||

| Missing, % | 99.0 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.5 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8.7 | |||

| Unknown, % | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 7.2 | n/a | 0.01 | n/a | 49.8 | 0 | n/a | 54.8 | 22.4 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Attempted Defibrillation | 1=Attempted defibrillation by layperson and/or EMS / 0=Not attempted defibrillation by layperson and EMS / 9=Unknown | Collected | Collected | Collected | EMS only | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | ||

| Missing, % | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 4.5 | 0.02 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | ||

| Unknown, % | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1.5 | n/a | 5.1 | n/a | 1.0 | n/a | 4.7 | 0.4 | n/a | n/a | 2.5 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Assisted Ventilation | 1=Assisted ventilations by EMS / 0=Not assisted ventilations by EMS / 9=Unknown | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Not collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Not collected | Not collected | ||

| Missing, % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 3.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | |||||

| Unknown, % | 0.6 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 0 | n/a | n/a | 0.2 | 1.8 | 0.7 | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Drugs | 1=Epinephrine / 2=Other drugs / 0=No drug / 9=Unknown | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Not collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | ||

| Missing, % | 0 | 0.09 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | |||

| Unknown, % | 0.6 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 0 | n/a | n/a | 0.7 | 0 | n/a | 0.1 | 0.3 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| ROSC before ED | 1=Yes / 0=No / 9=Unknown | Collected | ROSC at any time | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Not collected | Collected | ROSC at any time | Collected | ||

| Missing, % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 6.3 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | |||

| Unknown, % | 0 | 0 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 0 | n/a | 0.6 | n/a | 0 | n/a | 2.5 | 0.5 | |||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| ROSC sustained to ED arrival | 1=Yes / 0=No / 9=Unknown | Collected | Collected | Collected | Not collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Not collected | Collected | Not collected | Collected | ||

| Missing, % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.8 | 7.5 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 20.5 | 3.6 | |||||

| Unknown, % | 0 | 0 | n/a | n/a | 0.9 | n/a | 1.3 | n/a | 0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Hospital Admission | 1=Yes / 0=No / 9=Unknown | Collected | Not collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected (only from Jun 2007 to Nov 2009) | Not collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Not collected | Collected | ||

| Missing, % | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20.5 | 2.1 | |||||

| Unknown, % | n/a | n/a | 6.0 | n/a | 0 | 1.3 | n/a | 1.9 | 0 | 0.1 | 1.6 | |||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Survival to Hospital Discharge | 1=Discharged alive / 0=Not discharged alive / 9=Unknown | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected (30 days) | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | ||

| Missing, % | 0.6 | 2.4 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20.0 | 2.0 | ||

| Unknown, % | n/a | 0 | 0 | 6.8 | n/a | 0 | n/a | 0.4 | n/a | 6.8 | 0 | n/a | 0.0 | 1.8 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Neurological Status at Discharge | 1=CPC1 and CPC2, 0=CPC3, CPC4, and CPC5 / 9=Unknown | Collected but not collated | Collected but not collated (12 months) | Collected | Collected | Collected (30 days) | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | ||

| Missing, % | n/a | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 5.8 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8.0 | 19.7 | 3.3 | ||

| Unknown, % | n/a | n/a | n/a | 7.7 | n/a | 0 | n/a | 1.4 | n/a | 94.0 | 0 | n/a | 1.4 | 17.4 | ||

There was variation in how missing information was handled by each registry. Some combined “not done” and “unknown” into a single response. Among all contributed cases, the proportion of unknown was mean 4.8 ± 6.4%, and the proportion of missingness was mean 1.9 ± 2.2%.

Timed Event Variables

Four (33%) registries collected all recommended time variables (Table 3). All registries collected date of arrest, date of discharge/death, and time when call was received. Two (16.7%) did not transmit date of discharge/death because of regulatory issues; one (8.3%) did not because of a technical problem. Five (41.7%) did not collect time of witnessed/monitored arrest but one of these used time when call was received for witnessed arrest or rhythm analyzed for monitored arrest as surrogates for time of witnessed arrest. Four (33%) collected data on time of witnessed collapse by either bystander or EMS personnel, and one (8.3%) collected such data only when witnessed by EMS personnel. Five (41.7%) did not collect time of first rhythm analysis or assessment of need for CPR, but one of these substituted data on arrival at patient side. Four (33%) did not collect time of first CPR attempt. Among registries that did collect time of first CPR attempt, 4 (33%) collected data on time of first CPR attempt by either bystander or EMS personnel, 3 (25%) collected time of CPR attempt only for EMS personnel, and one (8.3%) collected time of CPR attempt by both bystander and EMS personnel. Five (41.7%) did not collect time of first defibrillation attempt if shockable rhythm. Three (25%) collected data on time of first defibrillation attempt if shockable rhythm by either bystander or EMS personnel, four (33%) collected data related only to EMS personnel, and one (8.3%) collected data related to either bystander and EMS personnel.

TABLE 3.

Time Variables Collected by Participating Utstein-Style Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Registries

| Variable | Coding | SJA-WA Cardiac Arrest Registry |

Victorian Ambulance Cardiac Arrest Registry |

CAVAS Project | Taipei OHCA Registry |

Utstein Osaka Project |

ROC | Irish OHCAR | ARREST | Oslo and Akershus Registry |

Helsinki Cardiac Arrest Registry |

Swedish

Register of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation |

VICAR | German Resuscitation Registry |

Average Missingness (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Date of arrest | DD/MM/YYYY | Collected not collated | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected not collated | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | |

| Missing, % | n/a | 0 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Date of discharge/death | DD/MM/YYYY | Collected not collated | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected not collated | Collected | Collected | Collected not collated | Collected | |

| Missing, % | n/a | 0.7 | 0.8 | 7.0 | 3.7 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.8 | n/a | 0.4 | 10.7 | n/a | 41.3 | 6.7 | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Time of witnessed/monitored arrest | DD/MM/YYYY | Not collected | Collected not collated | Not collected | Not collected | Collected if bystander or EMS witnessed | Collected if EMS-witnessed arrest | Collected | Not collected | Collected if bystander or EMS witnessed | Use time when call received or time of first rhythm analysis as surrogate | Collected if bystander or EMS witnessed | Collected not collated | Collected if bystander or EMS witnessed | |

| Missing, % | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 0 | 18.6 | 17.5 | n/a | 8.0 | 7.3 | n/a | 43.0 | 15.7 | ||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Time when call received | HH/MM/SS | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | Collected | |

| Missing, % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.21 | 4.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 7.1 | 0.4 | 11.1 | 1.8 | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Time of first rhythm analysis/assessment of need for CPR | HH/MM/SS | Not collected | Use time of EMS arrival at patient side as surrogate | Not collected | Collected for EMS only | Collected for bystander or EMS | Collected | Collected | Collected for bystander use of AED or EMS | Not collected | Collected | Collected | Collected for EMS only | Not collected | |

| Missing, % | n/a | n/a | 1.0 | 0.7 | 19.2 | 19.2 | 7.0 | n/a | 0.2 | 30.0 | 4.0 | n/a | 10.2 | ||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Time of first CPR attempts | HH/MM/SS | Not collected | Collected if EMS-witnessed arrest | Not collected | Collected for bystander or EMS | Collected for bystander and EMS | Collected for EMS only | Collected for bystander or EMS | Not collected | Not collected | Collected if EMS-witnessed arrest | Collected for bystander or EMS | Collected not collated | Collected for bystander or EMS | |

| Missing, % | n/a | 0.8 | n/a | 11.0 | 0.1 | 13.6 | 25.6 | n/a | n/a | 0.2 | 7.0 | n/a | 58.4 | 14.6 | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Time of first defibrillation attempt if shockable rhythm | HH/MM/SS | Not collected | Collected for EMS only | Not collected | Collected for EMS only | Collected for bystander and EMS | Collected for EMS only | Collected for bystander or EMS | Collected for bystander or EMS | Not collected | Collected for bystander or EMS | Collected for bystander or EMS | Not collected | Collected for bystander or EMS | |

| Missing, % | n/a | 2.8 | n/a | 14.2 | 0 | 10.7 | 38.1 | 2.5 | n/a | 4.8 | 11.1 | n/a | 42.1 | 14.0 | |

Among all registries, missingness was mean 9.0 ± 6.3%.

Quality Control

10 (83.3%) registries were reported to use periodic synchronization of monitor/defibrillators with atomic clocks to reduce uncertainty and variability in response time intervals. 10 (83.3%) were reported to periodically monitor for missing cases. Of those, nine (90%) remediated if missing cases were identified.

Discussion

This large, multicenter, international retrospective cohort study demonstrated differences in the measurement of the process and outcome of care after OHCA.(18) Accurate measurement is a key step towards improvement of resuscitation care. The Utstein template is a recognized standard for measuring resuscitation process, but there is variation in how the template is interpreted or implemented and in the magnitude of missingness. Estimates of the independent effect of resuscitation treatments could be modified by incomplete adjustment for risk factors that are not measured or that are not adjusted for because of a high degree of missingness. An EMS agency that identifies and reports all key risk factors or processes of care in patients treated for OHCA including those who die in the field may falsely appear to have poor performance when compared to one that collates less complete information.

The Utstein template was intended to increase the comparability of assessments of the process and outcome of care within and between EMS systems.(4) It has contributed to a greater understanding of the elements of effective resuscitation practice. While use of the template provides a mechanism for EMS agencies to measure and improve performance, doing so requires some human resources. Others previously demonstrated that some Utstein variables are not routinely collected.(19) The prior study used published summary data whereas we used individual patient data. The present study confirmed that not all recommended variables are collected, and that ongoing effort is necessary to achieve greater comparability between communities.

The original template focused on a comparator population of adults with bystander-witnessed ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia.(4) The revised template focused on a comparator population of adults with OHCA treated by EMS.(5) The rationale for this change included the secular decrease in proportion of OHCA with a first-recorded rhythm of VF.(20) As well, the proportion of OHCA with a first-recorded rhythm that is shockable declines as the response time interval increases, so it is a process measure rather than a baseline characteristic for some assessments.(21) Thus changes in survival among patients with VF over time may reflect the effect of interventions to improve survival, or secular changes in the epidemiology of OHCA in the community, or changes in the response time interval of the EMS agency that serves it.

Some registries included patients treated with an AED by laypersons before EMS arrival. As AED placement in public locations for use by laypersons increases, the proportion of patients who receive a shock with an AED before EMS arrival increases year by year.(22, 23) Inclusion of patients who are treated by laypersons allows evaluation of performance of the system of care as a whole, including the community as well as EMS response.

All registries included in this analysis collect survival to hospital discharge and neurological status at discharge with the exception of the Osaka, Japan registry and Victoria Ambulance Cardiac Arrest registry, Australia. Both of these collect outcomes after discharge. The latter may have some heterogeneity because of variation in length of stay due to patient morbidity as well as to practice patterns. Importantly, neurologic outcome and functional status often improve in this population after discharge from hospital.(24) However assessment of long-term outcome is resource intensive, technically challenging and subject to bias because of lack of consent or lack of response.(25)

We observed differences in coding and missingness between registries. Differences in coding of whether a procedure was not done vs. of unknown status are a challenge to comparisons between regions. Missing data arise in most clinical studies and can bias inferences, if data are not missing completely at random.(26) For example, comparison of outcomes between EMS systems that are restricted to cases with complete covariate information have reduced validity. In the future, use of methods to standardize coding and reduce missingness would facilitate valid comparisons

There was variation in use of time synchronization of monitor/defibrillators. Lack of such synchronization increases uncertainty in response time intervals.(27) Some time intervals are estimated form interrogating witnesses. Increased uncertainty attenuates assessments of the relationship between time-dependent factors and outcome.(28, 29) Future iterations of Utstein methodology should specify use of time synchronization to increase the comparability of reports within and between centers.

There was variation in use of audit and remediation of missing cases. The observation that the incidence of OHCA reported by ROC has increased by about 20% over time among its US sites while using routine monitoring for missing cases suggests this bias may not be small.(1, 30) Future iterations of Utstein methodology should specify methods of ascertaining data quality to increase the comparability of reports.

Evidence of the effectiveness of resuscitation processes of care has increased recently. Elements of care associated with greater survival include better manual compressions by EMS,(31-34) dispatcher assisted CPR,(35) early coronary angiography,(36) early therapeutic hypothermia after hospital arrival,(37) as well as deferred prognosis assessment and withdrawal of care.(38). Augmenting the Utstein template to include limited assessment of CPR at the scene and interventions in hospital could enhance the opportunity to assess and improve performance of the system as a whole

This study has several limitations. First, registries that participated were not selected at random. The number of episodes contributed by each registry was variable. Regions that were willing or able to participate may have been more likely to comply with the Utstein template whereas compliance might be worse in non-participating regions. Therefore, the present study might underestimate the current state of incompleteness of Utstein data variables.

Second, grouping by EMS system and use of tiered response was sometimes challenging. In some settings, multiple EMS agencies cover a region like a patchwork, with a variable degree of overlap. As well, some municipal EMS systems use a private EMS agency for non-urgent transportation. Other agencies occasionally dispatch a paramedic supervisor to the scene. Most experts would not classify either of these as three-tier services. Although it is convenient to group prehospital emergency care by site or as either a one or two-tier system, additional granularity about how services are provided may yield additional insight into regional differences in process and outcome.

Third, the date of arrests included in this study varied between regions. Guidelines for CPR and emergency cardiovascular care were updated twice during this time period.(39, 40) It takes time to implement new resuscitation guidelines.(41, 42) The increased emphasis on measurement and quality improvement in sequential resuscitation guidelines may be associated with greater completeness in contemporary datasets. Future comparisons of the process and outcome of care should adjust for secular trends.

Fourth, we were unable to obtain all Utstein core variables from all participating regions even though we sought de-identified data. It is difficult to collect all Utstein variables even within a single region since real or perceived legal constraints limit sharing of information between EMS agencies and hospitals.(13) Classifying OHCA as a reportable public health condition worldwide could help permit more open sharing of data, so long as such efforts are consistent with regulations that govern human subject research.(CFR 45)

Others have highlighted difficulties inherent in reliable and valid measurement of restoration of circulation(43) or neurologic status at discharge.(44) We did not obtain detailed descriptions of how these outcomes were assessed in each registry.

Conclusions

There are international differences in measurement of the process and outcome of care for patients with OHCA. Greater consistency would facilitate improved resuscitation care and comparison within and between communities.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to all of the Emergency Medical System personnel and concerned physicians in participant registries, as well as of other members of the registries’ for their contribution to the organization, coordination, and oversight of this study as well as their willingness to collaborate and share their data.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflict of Interest and Source of Funding:

None to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nichol G, Thomas E, Callaway CW, et al. Regional variation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest incidence and outcome. JAMA. 2008;300:1423–31. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.12.1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunne RB, Compton S, Zalenski RJ, Swor R, Welch R, Bock BF. Outcomes from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Detroit. Resuscitation. 2007;72:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rea TD, Helbock M, Perry S, et al. Increasing use of cardiopulmonary resuscitation during out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation arrest: survival implications of guideline changes. Circulation. 2006;114:2760–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.654715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cummins RO, Chamberlain DA, Abramson NS, et al. Recommended guidelines for uniform reporting of data from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: the Utstein Style. A statement for health professionals from a task force of the American Heart Association, the European Resuscitation Council, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, and the Australian Resuscitation Council. Circulation. 1991;84:960–75. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.2.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobs I, Nadkarni V, Bahr J, et al. Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports: update and simplification of the Utstein templates for resuscitation registries: a statement for healthcare professionals from a task force of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association, European Resuscitation Council, Australian Resuscitation Council, New Zealand Resuscitation Council, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Councils of Southern Africa) Circulation. 2004;110:3385–97. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147236.85306.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bobrow BJ, Clark LL, Ewy GA, et al. Minimally interrupted cardiac resuscitation by emergency medical services for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2008;299:1158–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bobrow BJ, Spaite DW, Berg RA, et al. Chest compression-only CPR by lay rescuers and survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA. 2010;304:1447–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lund-Kordahl I, Olasveengen TM, Lorem T, Samdal M, Wik L, Sunde K. Improving outcome after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest by strengthening weak links of the local Chain of Survival; quality of advanced life support and post-resuscitation care. Resuscitation. 2010;81:422–6. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinchey PR, Myers JB, Lewis R, et al. Improved out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival after the sequential implementation of 2005 AHA guidelines for compressions, ventilations, and induced hypothermia: the Wake County experience. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:348–57. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kellum MJ, Kennedy KW, Barney R, et al. Cardiocerebral resuscitation improves neurologically intact survival of patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:244–52. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kellum MJ, Kennedy KW, Ewy GA. Cardiocerebral resuscitation improves survival of patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Am J Med. 2006;119:335–40. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rea TD, Cook AJ, Stiell IG, et al. Predicting survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: role of the Utstein data elements. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:249–57. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grasner JT, Herlitz J, Koster RW, Rosell-Ortiz F, Stamatakis L, Bossaert L. Quality management in resuscitation--towards a European cardiac arrest registry (EuReCa) Resuscitation. 2011;82:989–94. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrison LJ, Nichol G, Rea TD, et al. Rationale, development and implementation of the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium Epistry-Cardiac Arrest. Resuscitation. 2008;78:161–9. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glover BM, Brown SP, Morrison L, et al. Wide variability in drug use in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A report from the resuscitation outcomes consortium. Resuscitation. 2012;83:1324–30. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ornato JP, Doctor ML, Harbour LF, et al. Synchronization of timepieces to the atomic clock in an urban emergency medical services system. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31:483–7. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferreira-Gonzalez I, Marsal JR, Mitjavila F, et al. Patient registries of acute coronary syndrome: assessing or biasing the clinical real world data? Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:540–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.844399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neumar RW, Barnhart JM, Berg RA, et al. Implementation strategies for improving survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the United States: consensus recommendations from the 2009 American Heart Association Cardiac Arrest Survival Summit. Circulation. 2011;123:2898–910. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31821d79f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fredriksson M, Herlitz J, Nichol G. Variation in outcome in studies of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a review of studies conforming to the Utstein guidelines. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:276–81. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(03)00082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cobb LA, Fahrenbruch CE, Olsufka M, Copass MK. Changing incidence of out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation, 1980-2000. JAMA. 2002;288:3008–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.3008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holmberg M, Holmberg S, Herlitz J. An alternative estimate of the disappearance rate of ventricular fibrillation in our-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Sweden. Resuscitation. 2001;49:219–20. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(00)00376-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kitamura T, Iwami T, Kawamura T, Nagao K, Tanaka H, Hiraide A. Nationwide public-access defibrillation in Japan. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:994–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weisfeldt ML, Sitlani CM, Ornato JP, et al. Survival after application of automatic external defibrillators before arrival of the emergency medical system: evaluation in the resuscitation outcomes consortium population of 21 million. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1713–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roine RO, Kajaste S, Kaste M. Neuropsychological sequelae of cardiac arrest. JAMA. 1993;269:237–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nichol G, Powell J, van Ottingham L, et al. Consent in resuscitation trials: benefit or harm for patients and society? Resuscitation. 2006;70:360–8. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2006.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He Y. Primer on Statistical Interpretation or Methods. Missing Data Analysis Using Multiple Imputation. Getting to the Heart of the Matter. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:98–105. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.875658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neukamm J, Grasner JT, Schewe JC, et al. The impact of response time reliability on CPR incidence and resuscitation success: a benchmark study from the German Resuscitation Registry. Crit Care. 2011;15:R282. doi: 10.1186/cc10566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spaite DW, Stiell IG, Bobrow BJ, et al. Effect of transport interval on out-of-hospital cardiac arrest survival in the OPALS study: implications for triaging patients to specialized cardiac arrest centers. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:248–55. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shy BD, Rea TD, Becker LJ, Eisenberg MS. Time to intubation and survival in prehospital cardiac arrest. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2004;8:394–9. doi: 10.1016/j.prehos.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6–e245. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christenson J, Andrusiek D, Everson-Stewart S, et al. Chest compression fraction determines survival in patients with out-of-hospital ventricular fibrillation. Circulation. 2009;120:1241–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.852202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vaillancourt C, Everson-Stewart S, Christenson J, et al. The impact of increased chest compression fraction on return of spontaneous circulation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients not in ventricular fibrillation. Resuscitation. 2011;82:1501–7. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheskes S, Schmicker RH, Christenson J, et al. Perishock pause: an independent predictor of survival from out-of-hospital shockable cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2011;124:58–66. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.010736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stiell IG, Brown SP, Christenson J, et al. What is the role of chest compression depth during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest resuscitation? Critical care medicine. 2012;40:1192–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31823bc8bb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rea TD, Fahrenbruch C, Culley L, et al. CPR with chest compression alone or with rescue breathing. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:423–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strote JA, Maynard C, Olsufka M, et al. Comparison of Role of Early (Less Than Six Hours) to Later (More Than Six Hours) or No Cardiac Catheterization After Resuscitation From Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Am J Cardiol. 2011;109:451–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mooney MR, Unger BT, Boland LL, et al. Therapeutic Hypothermia After Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: Evaluation of a Regional System to Increase Access to Cooling. Circulation. 2011;124:206–14. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.986257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nielsen N, Wetterslev J, Cronberg T, et al. Targeted temperature management at 33 degrees C versus 36 degrees C after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2197–206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anonymous. 2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2005;112(IV):19–34. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.166550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Field JM, Hazinski MF, Sayre MR, et al. Part 1: executive summary: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122(18 Suppl 3):S640–56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berdowski J, Schmohl A, Tijssen JG, Koster RW. Time needed for a regional emergency medical system to implement resuscitation Guidelines 2005--The Netherlands experience. Resuscitation. 2009;80:1336–41. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bigham BL, Koprowicz K, Aufderheide TP, et al. Delayed prehospital implementation of the 2005 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiac care. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2010;14:355–60. doi: 10.3109/10903121003770639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.A randomized clinical study of cardiopulmonary-cerebral resuscitation: design, methods, and patient characteristics. Brain Resuscitation Clinical Trial I Study Group. Am J Emerg Med. 1986;4:72–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsu JW, Madsen CD, Callaham ML. Quality-of-life and formal functional testing of survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest correlates poorly with traditional neurologic outcome scales. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:597–605. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70080-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]