Abstract

Motivation: Insertions play an important role in genome evolution. However, such variants are difficult to detect from short-read sequencing data, especially when they exceed the paired-end insert size. Many approaches have been proposed to call short insertion variants based on paired-end mapping. However, there remains a lack of practical methods to detect and assemble long variants.

Results: We propose here an original method, called MindTheGap, for the integrated detection and assembly of insertion variants from re-sequencing data. Importantly, it is designed to call insertions of any size, whether they are novel or duplicated, homozygous or heterozygous in the donor genome. MindTheGap uses an efficient k-mer-based method to detect insertion sites in a reference genome, and subsequently assemble them from the donor reads. MindTheGap showed high recall and precision on simulated datasets of various genome complexities. When applied to real Caenorhabditis elegans and human NA12878 datasets, MindTheGap detected and correctly assembled insertions >1 kb, using at most 14 GB of memory.

Availability and implementation: http://mindthegap.genouest.org

Contact: guillaume.rizk@inria.fr or claire.lemaitre@inria.fr

1 INTRODUCTION

Structural variants (SVs) are large-scale structural changes in the genome. They have been typically defined in opposition to point mutations, which are single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and short insertions or deletions (indels). SVs therefore include insertions, deletions and inversions of genomic sequences. Recent research has shown that they play an important role in evolution and diseases (1000 Genomes Project Consortium et al., 2010; Stewart et al., 2011). However, SVs are challenging to discover using present-day sequencing approaches, as they generally span genomic regions that are longer than the reads. Computational methods have been designed to extract evidence of SVs from sequencing data using two types of analyses: paired-end mapping of reads to a reference genome and copy number estimation using read depth (Alkan et al., 2011; Medvedev et al., 2009).

1.1 Definition of insertion variants

In this work, we will focus on insertion variants: sequences that are present at one site (position) in the donor genome but are absent from the reference genome at this site. We divide insertions into three mutually exclusive types: (i) novel insertions in the donor genome that have no match in the reference, (ii) duplicated insertions, which are found at two or more sites in the donor and a strict subset of those in the reference and (iii) transpositions, which are sequences in the reference that moved to a different site in the donor. Duplicated insertions include mobile element insertions (MEI), for which databases of known sequences have been created to facilitate discovery (Stewart et al., 2011).

All three types of insertions are difficult to detect using short reads. Different techniques are used to detect insertions that are short (shorter than the reads), medium (of size between read length and insert size) or long (of size exceeding insert size). In the next two sections, we review techniques used to identify insertion sites, and techniques used to reconstruct insertion sequences.

1.2 Identification of insertion sites

As short insertions are likely to be fully contained in several reads, mapping donor reads to a reference genome enables simultaneous discovery of the sites and contents of insertions (Albers et al., 2011; DePristo et al., 2011; Li et al., 2009; Ye et al., 2009). In this context, results are sensitive to mapping parameters and may be degraded in low-coverage or low-complexity regions of the reference. Although the discovery of short indels has been an extensively studied problem, a recent article has observed considerable differences between the results of popular tools (Pabinger et al., 2013).

Sites of medium-sized insertions can be detected by analyzing mapping positions of paired reads. General SV calling tools call insertions sites by clustering neighboring read pairs that have a shorter insert size than expected, e.g. BreakDancer and GASV (Chen et al., 2009; Sindi et al., 2009). NovelSeq (Hajirasouliha et al., 2010) and SOAPindel (Li et al., 2013) detect sites of long, novel insertions by clustering paired reads for which one mate is unmapped.

Alternatively, tools based on read coverage can detect duplicated insertions of any length by finding reference segments that have higher read depth than expected. While insertion sites cannot be determined by this method alone, the Reprever (Kim et al., 2013) software identifies low-copy duplicated insertions by combining paired-end mapping with read depth analysis. Finally, several methods detect sites of mobile element insertions using collections of known transposable element sequences, by searching for read pairs where one mate is mapped to a known element and the other to a unique part of the reference genome (Ewing and Kazazian, 2011; Hormozdiari et al., 2010; Stewart et al., 2011).

1.3 Reconstruction of inserted sequences

While short insertions are easy to reconstruct (as seen in Section 1.2), to the best of our knowledge, only a few methods are capable of handling medium or long insertions. They are based on global or local de novo assembly of reads that are potentially involved in an insertion.

SOAPindel (Li et al., 2013), Scalpel (Narzisi et al., 2013) and TIGRA (Chen et al., 2014) select paired reads for which one of the mates maps nearby an insertion site. The other mates are used to assemble separately each inserted sequence. This approach can only reconstruct insertions that are shorter than twice the insert size. NovelSeq (Hajirasouliha et al., 2010) reconstructs novel insertions (of any size) by assembling all unmapped reads, and then aligning the extremities of assembled sequences to all predicted insertion sites. Parrish et al. (2011) proposed to extend this approach to duplicated insertions by performing a global assembly of all reads that are either unmapped, discordantly paired or mapped to high-coverage regions.

Cortex_var (Iqbal et al., 2012) builds a colored de Bruijn graph from the reference genome and all donor reads. Insertions appear in the graph as bubbles (sets of paths between two nodes), where one short path corresponds to the reference genome, and longer paths correspond to inserted sequences. Theoretically, this approach enables the discovery of insertions regardless of their size and type. However, because of practical limitations, Cortex_var only finds a restricted class of bubbles: those that (i) contain exactly two paths and (ii) all intermediate nodes having exactly one in-neighbor and one out-neighbor.

To summarize, available tools are highly specialized and lack the versatility to detect and assemble insertions of any size and any type. SOAPindel, Scalpel and Cortex_var are practically limited to short insertions, Reprever is limited to low-copy duplicated sequences and Novelseq is limited to novel insertions.

1.4 Our contribution

We propose a new tool, MindTheGap, for detecting and assembling insertions. MindTheGap has several novel features that are not found in other tools. First, a mapping-free site detection algorithm has been designed to detect insertions of any size. Second, an improved method for insertion assembly enables the reconstruction of long insertions of all three types. Third, a memory-efficient data structure enables high scalability.

We evaluated MindTheGap on simulated and real Illumina sequencing data. Among 1 kbp simulated homozygous insertions, a large fraction were found and correctly assembled (recall values between 65–98.4%, precision >97%). Simulated heterozygous 1 kbp insertions proved to be more challenging to assemble (60% recall for Caenorhabditis elegans, 35% for human chromosome 22); however, precision remained high (93% and 89%, respectively). We assembled long insertions using MindTheGap on an actual whole-genome human dataset, which required only 14 GB of memory.

2 METHODS

The input of MindTheGap is a set of reads and a reference genome. The software performs three steps: (i) construction of the de Bruijn graph of the reads, (ii) detection of insertion breakpoints on the reference genome (find module) and (iii) local assembly of inserted sequences (fill module). Both the detection step and the assembly step rely solely on the constructed graph.

The output of the second step is a set of putative insertion positions on the reference genome, whereas the output of the last step is, for each insertion site, one or several assembled sequences.

2.1 de Bruijn graph construction

The de Bruijn graph is a directed graph over all distinct k-mers in the reads. An edge is present when two k-mers share an exact -overlap. The graph is constructed using the algorithms implemented in the Minia assembler (Chikhi and Rizk, 2013; Salikhov et al., 2013). Minia encodes the graph using a Bloom filter and an additional hash table to suppress false-positive results. The data structure supports two operations: (i) membership queries for k-mers that are neighbors of existing k-mers in the graph, and (ii) traversal of the graph from an existing k-mer. These operations are respectively used in Section 2.2 (insertion site detection) and Section 2.3 (local assembly).

2.2 Find module: detection of insertion sites

MindTheGap detects insertion sites by scanning the reference genome and testing membership of reference k-mers in the de Bruijn graph. Homozygous and heterozygous insertions are handled using two different methods.

2.2.1 Homozygous insertions

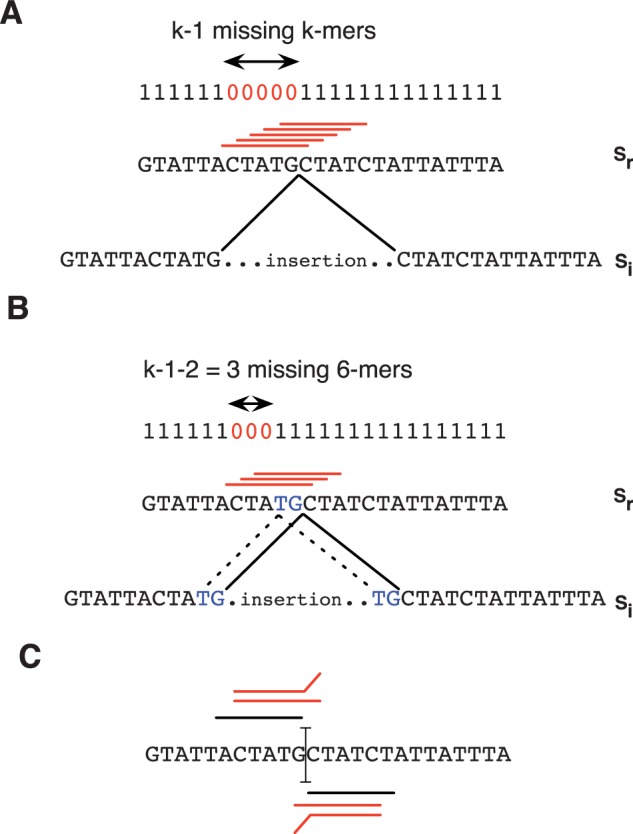

The general case for detecting homozygous insertions can be modeled as follows. Let Sr be a sequence (the reference). For a position j in the reference, the k-mer at position (resp. j + 1) is called the left (resp. right) flanking k-mer. Let Sd (the donor) be a copy of Sr where a sequence I has been inserted between the nucleotides at position i and i + 1 (the insertion site, see Fig. 1). For each position in the reference genome, a binary character records whether the k-mer starting at this position is present (‘1’) or absent (‘0’) in the donor reads. Depending on the context, the reference genome will correspond to the string of nucleotides or to the string of binary characters. Let a gap be a substring in the reference genome equal to (formed by repeating ‘0’ n times), for n > 0, that is immediately flanked by ‘1’ characters. In most cases, a homozygous insertion site at position i has a gap of size k − 1 starting at position (all k − 1 k-mers overlapping the insertion site are absent in Sd). We refer to this situation as a canonical insertion site (see Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

(A) Canonical insertion site. The site is detected by its specific signature: the (k − 1) k-mers spanning the insertion site are missing in the sequence with the insertion (here k = 6), these k-mers are represented as red segments. (B) Fuzzy insertion site. Insertion ends with the same nucleotides (TG) present on the left of the site. In dashed lines, an alternative insertion site. (C) Heterozygous insertion site. Flanking k-mers (in black) surrounding a heterozygous site respectively have two right branching k-mers (for the k-mer on the left of the site) and two left-branching k-mers (for the right k-mer)

A gap may be shorter than k − 1, for instance, when the prefix of the inserted sequence I exactly matches the prefix of the sequence to the right of the insertion site (see Fig. 1B). More generally, if the longest common prefix of I and is of size r1 and the longest common suffix of I and is of size r2, then the size of the gap is . It is important to note that when r1 or r2 is greater than 0, with only sequences Sd and Sr at hand, it is not possible to localize precisely the insertion site, as it can be at any location in . We refer to such sites as fuzzy sites. Homozygous insertion sites are called when gaps of size in the range are detected, with r being a user-defined parameter indicating the largest allowed repeat at the insertion.

The size of the gap is an important criterion to detect homozygous insertion sites, as other types of variants also yield gaps. SNPs create gaps of size exactly k and deletions of length d yield gaps of size . Variants that are separated by less than k nucleotides yield longer gaps. In fact, only new junctions between existing sequences can yield gaps of size , which is the case for insertion events, but also for inversion or translocation sites. Finally, gaps of various sizes may also appear due to insufficient read coverage or non-uniqueness of k-mers inside the reference genome. These effects are controlled by the value of k, which is a parameter of our method.

2.2.2 Heterozygous insertions

While heterozygous insertions sites do not yield gaps, flanking k-mers at these sites still exhibit features that can be detected. The left flanking k-mer of a heterozygous insertion site has at least two out-neighbors in the de Bruijn graph: one neighbor in the reference sequence and at least one other neighbor that is a prefix of the inserted sequence. Similarly, the right flanking k-mer has at least two in-neighbors with similar properties (see Fig. 1C). As in the homozygous case, small repetitions at the extremities of inserted sequences slightly alter the pattern. The left flanking k-mer may overlap the right flanking k-mer in the reference genome. MindTheGap detects heterozygous insertion sites by scanning the reference genome and testing neighborhoods of putative left and right flanking k-mers whose distance from one another is comprised between k – r and k, r being the same user-defined parameter as for homozygous insertions, indicating the largest allowed repeat at the insertion.

Heterozygous SNPs and deletions yield similar patterns, but the left and right flanking k-mers are further separated from each other (k + 1 nucleotides apart for SNPs and 1-bp deletions, nucleotides apart for deletions of size d). However, heterozygous inversions and translocations do exhibit identical patterns. Also, inexact repetitions in the reference genome create branching k-mers, which may yield by chance the same pattern as a heterozygous insertion. To reduce this effect, we apply an additional filter: the k − 1 suffix (resp. prefix) of the right (resp. left) flanking k-mer must have less than h occurrences in the reference genome. When h is set to 1, this prevents the detection of patterns that may be generated by repetitions in the reference genome alone, in absence of any sequence variants.

2.3 Fill module: assembly of inserted sequences

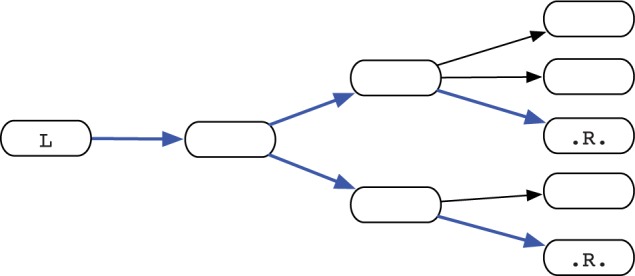

The third step of MindTheGap is called the fill module. Starting from a known insertion site represented by flanking k-mers (L, R), the module performs de novo assembly to attempt to reconstruct the inserted sequence between L and R. In a nutshell, a graph of contigs is constructed by performing breadth-first traversal of k-mers, starting from L. The traversal is halted when graph becomes too complex. Then, all the contigs in the graph are searched for the presence of R. All paths between L and the contigs containing R are enumerated, and one or more putative insertion sequences are returned (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fill module. A graph of contig is constructed from the left flanking kmer L, in a breadth-first search order. Construction stops when a maximum number of nodes is reached, or when a branch becomes too deep. The right flanking kmer R is searched within all nodes, finally all paths (in blue) between L and R are outputted as putative insertions

More specifically, insertions are assembled using the algorithm of Minia (Chikhi and Rizk, 2013; Salikhov et al., 2013). Assembly is performed by traversing the graph from a given starting k-mer in a breadth-first fashion. A consensus sequence (contig) is generated by skipping over certain motifs, such as bubbles (putative short variants) and tips (putative errors). This Minia assembly procedure stops whenever a contig cannot be unambiguously extended.

A graph of contigs is constructed for each insertion site (L, R) as follows. First, an initial contig cL is constructed by calling the Minia assembly procedure from the L k-mer. Given a contig c (initially c = cL), the four putative neighbors of the last k-mer of c are examined. If no neighbor is present, indicating that c could not be extended, then no further action is performed for this contig. Otherwise, if two or more neighbors are present in the data structure, new contigs will be constructed starting from each of these neighbors. Directed edges will be inserted from c to these new contigs. This process goes on to construct the contig graph in breadth-first order until a maximum number of contigs (parameter n, usually set to 100) is reached, or a maximal depth (parameter i, usually set to 10 kb and computed by counting nucleotides in contigs) is reached.

An exhaustive search is performed to find occurrences of R within all contigs in graph, as an exact match (default behavior) or up to a constant number of mismatches. All possible paths between L and R are exhaustively enumerated (i.e. putative insertions). If all paths spell pair-wise identical sequences (minimum identity of 80%), then one of them is returned. Otherwise, the insertion site is considered to be unsuccessfully assembled and all paths are returned. The fill module is performed bi-directionally, i.e. should the (L, R) insertion site yield no path, then the module attemps to assemble the insertion, where denotes the reverse-complement operation.

2.4 Evaluation protocol

2.4.1 Simulated datasets

To evaluate MindTheGap, we generated artificial read datasets and reference genomes based on real genomes. First, we simulated sequencing reads for a real genome (the donor). Then, another genome (the reference) was obtained by simulating non-overlapping deletions from a copy of the donor genome. Deletion locations were sampled uniformly along the sequence. These deletions correspond to homozygous insertions in the donor. To simulate heterozygous insertions, reads were sampled in equal numbers from the donor and the reference genomes. Sequencing was simulated with Wgsim from the Samtools package (Li et al., 2009) using the following parameters: paired-end mode with 2 × 100 bp reads, an insert size of 300 bp (std = 50) and a base error rate of 0.01. Coverage was set to 40× for homozygous datasets and 60× for heterozygous datasets.

Three different genomes were used: Escherichia coli K12 (4.6 Mb), C.elegans (100.3 Mb) and the human chromosome 22 (35 Mb without N bases). For each of them, simulated datasets were generated with homozygous or heterozygous deletions of varying sizes.

2.4.2 Assessment of results

Positions of found breakpoints are compared with positions of introduced deletions in the genome. A breakpoint is considered as true positive (TP) if its location is at most 10 bp from a generated deletion position. This margin is meant to take into account fuzzy sites, for which breakpoints are not necessarily found at the exact position of the corresponding deletions (see Section 2). For each TP breakpoint, a global alignment between the assembled inserted sequence and the real sequence of the deletion is then performed with needle from the EMBOSS tool suite. We consider the filled sequence as TP if the alignment shows >90% of identity. Finally, the recall is the number of TP filled sequences over the number of simulated insertions, and the precision is the number of TP filled sequences over the number of filled insertions.

2.4.3 Real sequencing data

Paired-end sequencing data from C.elegans strain N2 were downloaded from SRA (accession SRX026594). This dataset is composed of 33.8 M Illumina 2 × 100 bp read pairs (insert size of 350 bp), representing roughly 70× of coverage on the 100.3 Mb reference sequence of C.elegans (downloaded from NCBI version WBcel235). As we did not find any validated dataset of known large insertions for this genome, we simulated insertion variants following the protocol of simulated data: 1000 regions of a given size (here 1–100 bp or 1 kb) were deleted in the reference genome, corresponding to homozygous insertion variants in the N2 donor genome.

Sequencing data of human individual NA12878 from DePristo et al., 2011, consisting of 2.8 G Illumina 2 × 101 bp read pairs, was downloaded from EBI (ftp://ftp-trace.ncbi.nih.gov/1000genomes/ftp/technical/working/20101201_cg_NA12878/NA12878.hiseq.wgs.bwa.raw.bam). The human genome reference assembly (NCBI36 hg18) was downloaded from UCSC Genome Browser. A set of predicted or validated large insertions were obtained from Supplementary Material of Kim et al., 2013. This set contained 30 validated insertions from the study of Kidd et al. (2010) and 44 which were predicted by Kim et al. (2013) based on the alignments of 40 kb sequenced fosmids from this individual to the hg18 reference genome. These are long insertions (median size of 5 kb); 68 are >1 kb and 4 are >10 kb. Among these, 61 are predicted as novel insertions, 7 as duplicated and the remaining ones have an unknown status.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Results on simulated datasets

MindTheGap was applied on several simulated datasets to precisely estimate its recall and precision. This enabled to quantify the impact of different levels of genome complexity, to independently evaluate each module and modes (detection versus assembly, homozygous versus heterozygous) and to analyze the range of insertion sizes MindTheGap is able to detect and assemble.

3.1.1 High recall and precision in homozygous mode

For insertions of 1 kb, MindTheGap recovered between 65 and 98.4% of the simulated insertions, depending mainly on the complexity of the studied genome (Table 1). Almost all predicted homozygous insertions are true-positive results, resulting in high precision (consistently above 97%). Table 1 shows that almost all insertion sites were detected by the find module in homozygous mode. However, 19–35% of detected insertions could not be assembled by the fill module.

Table 1.

Precision and recall results for MindTheGap in homozygous mode on simulated and real datasets

| Dataset | Recall (%) | Precision (%) | N sim. | Find module |

Fill module |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP | FP | TP | FP | ||||

| E.coli simulated dataset | 98.4 | 99.8 | 500 | 499 | 0 | 492 | 1 |

| C.elegans simulated dataset | 79.5 | 97.3 | 1000 | 992 | 0 | 795 | 22 |

| C.elegans real reads, simulated insertions | 81.1 | – | 1000 | 980 | – | 811 | – |

| Human chromosme 22 simulated dataset | 64.6 | 99.4 | 1000 | 1000 | 0 | 646 | 4 |

Note. Simulated insertions of size 1000 (homozygous). The number of deletions simulated in the reference genome appears in the column ‘N sim.’

3.1.2 Varying insertion lengths

Figure 3 shows that MindTheGap can detect and assemble insertions of any size. We observed that the performance of the find module is independent of the size of the insertions: recall of the find module never fell below 98.5% (data not shown), without any false positive, even for the human chromosome 22 dataset. However, lower recalls are due to the fill module failing to assemble longer insertions. For small insertions (<100 bp), MindTheGap obtained high recall and precision for all simulated datasets.

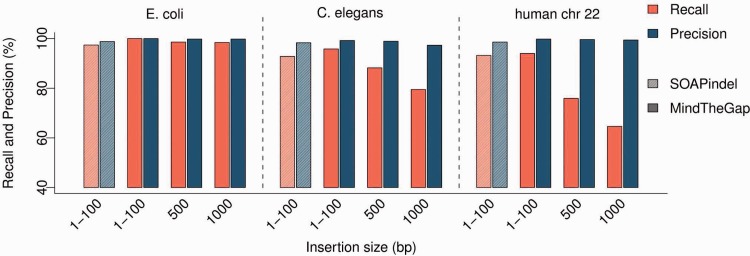

Fig. 3.

Results of MindTheGap and SOAPindel for several insertion sizes and several genome complexities. SOAPindel results are shown only for insertions of 1–100 bp (first two shaded bars in of each genome section), as it could detect only insertions <189 bp. Best results of SOAPindel were obtained with k parameter set to 31 (shown here) rather than 51. MindTheGap best results were obtained with k set to 31 for E.coli datasets and 51 for C.elegans and human chromosome 22

Only 650 over 1000 insertions of 1 kb could be assembled in the chromosome 22, and among these, 646 showed >90% identity with the original deleted sequences. This was likely because of the high repeat content of this chromosome. We observed that the insertions MindTheGap fails to assemble generally correspond to complex graph of contigs, containing many exact repeats longer than .

3.1.3 Heterozygous mode

To evaluate the heterozygous mode of MindTheGap, we simulated datasets with only heterozygous insertions (see Section 2.4). Our analysis in Methods showed that heterozygous insertion sites were likely to be more difficult to detect and distinguish from genomic repetitions than heterozygous insertions sites. Table 2 shows that for the human and C.elegans simulated datasets, both recall and precision are significantly below those in homozygous mode. Further investigation showed that the low recall is owing to poor performance of the find module. We found that the results in this module were sensitive to the values of parameters k, r (maximal repeat size at fuzzy sites) and h (maximal number of occurrences of flanking kmers in the reference genome). Setting k to a higher value and r and h to smaller values (here: k = 51, r = 2, h = 1) enabled to reach a precision ∼97%, at the cost of a noticeably lower recall. However, using a high k is detrimental to the fill module, due to read coverage being halved in heterozygous insertions. Table 2 shows that on these datasets, the fill module assembles significantly more insertions with k = 31.

Table 2.

Precision and recall results for MindTheGap in heterozygous mode on simulated datasets, containing each 1000 simulated heterozygous insertions of size 1000 bp

| Dataset | Recall (%) | Precision (%) | N sim. | Find module |

Fill module k = 51 |

Fill module k = 31 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP | FP | TP | FP | TP | FP | ||||

| C.elegans dataset | 59.9 | 93.4 | 1000 | 807 | 11 | 310 | 80 | 599 | 42 |

| Human chromosome 22 dataset | 35.5 | 89.0 | 1000 | 816 | 28 | 226 | 8 | 355 | 44 |

Note. Parameter r was set to 2, and assembled insertions smaller than 5 bp were filtered out.

3.1.4 Comparison with SOAPindel

On insertions of size 1–100 bp, SOAPindel shows similar recall and precision to MindTheGap (Fig. 3). However, SOAPindel is limited in the size of detectable insertions, depending on the insert size of the reads: given our simulation parameters, we observed that SOAPindel recall decreased for insertions larger than 175 bp, and the largest insertion detected was of length 189 bp. Noticeably, the performance of SOAPindel was independent of the genotype of insertions.

3.2 Evaluation on a real sequencing dataset of C.elegans

To evaluate the impact of real reads and a real donor genome with some degree of polymorphism in the reference genome, MindTheGap was run on a C.elegans strain N2 read dataset against the reference genome containing simulated deletions. This is to simulate homozygous insertion variants in the donor genome. Additional insertions variants are likely to exist C.elegans strain. Thus, the number of FP could not be evaluated, as the true set of insertions present in these reads is unknown.

For 1 kb insertion variants, 81.1% were correctly predicted and assembled by MindTheGap (Table 1). Compared with the fully simulated dataset on the same simulated insertions, the find module missed more insertion sites, whereas the fill module had a better recall of inserted sequences. The first observation could be explained by small polymorphism near the insertion breakpoints that generated longer gaps (see Section 2), whereas the second by a higher read coverage in this dataset.

Additionally, we compared MindTheGap and SOAPindel on this dataset with 1–100 bp simulated insertions. Recall values were similar for both tools: 89% and 91%, respectively.

3.3 Application on real insertions of human individual NA12878

To evaluate the ability of MindTheGap to recover real insertions in real data, we executed it on a human individual NA12878 dataset containing 2.8 G 100 bp reads. As the coverage was high, parameter k was empirically set to 63 and t to 5 (k-mers with less than five occurrences were discarded). Predictions were then compared with a set of 74 large insertions predicted by alignment of fosmid sequences to the reference hg18 genome (see Section 2.4).

20 insertion sites were recovered by the find module. No heterozygous insertions were predicted. We set r = 15, which enabled to find twice more sites than with r = 5. This suggests that real insertions contain longer repeated sequences at their breakpoints than expected in a random simulation. By analyzing paired-end reads that mapped near each fosmid-predicted breakpoint, we could infer the genotypes: only 23 breakpoints could be confidently assigned to a homozygous genotype (i.e. with less than five read pairs spanning the breakpoint). The find module recovered 11 of them. Of the remaining 12 likely homozygous sites, the breakpoints of 8 of them were included in a large gap () in the reference binary string. This suggests that these sites were close to other form of polymorphism, which would explain why MindTheGap did not detect them.

Among the 20 detected insertions by the find module, the fill module succeeded in reconstructing correctly two inserted sequences of sizes 4137 bp and 6729 bp, with respectively 99.9 and 99.8% identity to the fosmid sequences. This corresponds to a recall of 18%, when comparing with the 11 true homozygous insertions that were detected by the find module. This recall value is similar to one obtained on simulated insertions of 5 kb with the same read dataset (22%, data not shown).

3.4 Time and memory performance

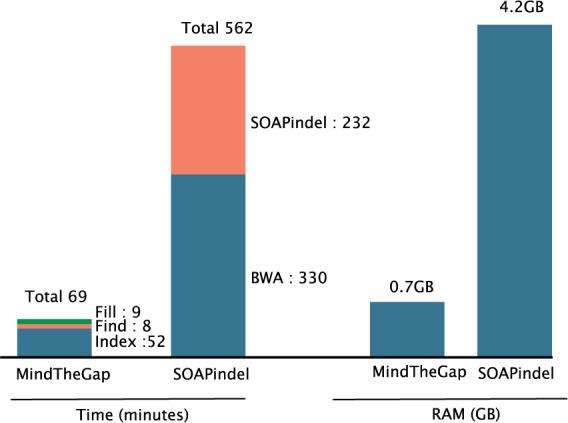

Figure 4 shows the total runtime and maximal memory used by MindTheGap and SOAPindel on the real C.elegans dataset. The machine used for all tests is a 12-core Intel E5-2640 @ 2.50 GHz with 192 GB of memory. For MindTheGap, the breakdown of the three steps index, find and fill shows that the major part of running time is spent on the index step. For SOAPindel, the time required to map the reads to the reference with bwa is included in the total time; however, SOAPindel alone remains slower than MindTheGap as a whole. SOAPindel used eight threads and MindTheGap only one.

Fig. 4.

Time (real time in minutes reported by the unix command time) and peak of memory used by MindTheGap (with k = 51) and SOAPindel (parameter k = 51) on the C.elegans real sequencing dataset (SRX026594). Peak of memory of SOAPindel approach was reached by the SOAPindel software itself (not bwa)

Importantly, even though MindTheGap stores in memory the whole de Bruijn graph of the C.elegans read dataset, its memory peak (0.7 GB) is six times lower than SOAPindel. On the NA12878 dataset with 2.8 billion reads, MindTheGap also proved to scale efficiently: the index/find/fill steps respectively took 32/6/7 h, with peak memory usage of 6/14/6 GB.

4 DISCUSSION

MindTheGap is the first integrated method to detect and assemble insertion variants of any size and any type, using modest computing resources. The find module of MindTheGap differs from most other existing methods by not relying on read mapping. Instead, the de Bruijn graph of reads is compared against the reference sequence, which enables fast and low-memory analysis. However, one current limitation of the find module is that it fails to detect insertions when other polymorphism occurs near the insertion site. Improvements to waive this limitation are under development, based on a more detailed analysis of gaps longer than k. Furthermore, the method could also be used to output SNPs and other types of structural variants.

Long insertion variants are challenging to detect and assemble; thus, there is a shortage of tools to compare MindTheGap with. We compared our results with SOAPindel, which is a popular indel detection software limited to short insertions. The NovelSeq software (Hajirasouliha et al., 2010) is designed to find and assemble large insertions, and therefore would have been another candidate for comparison. However, despite several attempts and reaching out to the author, we were unable to run the software successfully on any of our datasets (the novelseq_cluster step ran indefinitely). NovelSeq relies on a complex pipeline, and we conjecture that it may be tailored to specific data types. While most other insertion detection methods require to run external software, MindTheGap is stand-alone and is therefore easy to use. If needed, the modular organization of MindTheGap allows users to replace the find module with the results of a classical insertion detection based on paired-end mapping. The fill module could also be used as a de novo assembly finishing step, i.e. gap-filling between adjacent contigs in scaffolds, although we did not evaluate its performance for this task.

One important design choice for the fill module is to perform assembly with all the k-mers in the read dataset. This enables to assemble not only novel insertions, but also duplicated insertions and transposition events. Classification of assembled insertions into the different event types is not done by MindTheGap, but can be done by re-mapping insertions to the reference genome. One drawback of considering all reads during insertion assembly is that the de Bruijn graph becomes more complex to analyze. An important future work will be to improve the recall of the fill module by using paired-end reads information to guide traversal of contig graphs. As repeated regions are notoriously difficult to assemble, we anticipate that our approach might not be effective for mobile element insertions. However, there exist methods tailored to the assembly of MEI, based on local assembly with recruitment of mate reads.

Our tests on the NA12878 dataset showed there is room for improvement: only two long homozygous insertions were successfully assembled out of 23 predicted ones. We postulate that (i) polymorphism or repetitions near the insertion sites hinder detection by the find module, and (ii) the complexity of the human genome makes de novo assembly of large contigs difficult. As no other tool was able to assemble long insertions, we could not assess whether our results were owing to weaknesses in our method, or to specificities of this particular dataset (complex insertion sequences or mispredicted insertions).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Raluca Uricaru for her help and advice.

Funding: This work was supported by the ANR (French National Research Agency), ANR-12-BS02-0008 Colib’read project, ANR-12-EMMA-0019-01 GATB project and ANR-11-BSV7-005-01 SPECIAPHID.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- 1000 Genomes Project Consortium, et al. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albers CA, et al. Dindel: Accurate indel calls from short-read data. Genome Res. 2011;21:961–973. doi: 10.1101/gr.112326.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkan C, et al. Genome structural variation discovery and genotyping. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011;12:363–376. doi: 10.1038/nrg2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, et al. Breakdancer: an algorithm for high-resolution mapping of genomic structural variation. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:677–681. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, et al. Tigra: a targeted iterative graph routing assembler for breakpoint assembly. Genome Res. 2014;24:310–317. doi: 10.1101/gr.162883.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikhi R, Rizk G. Space-efficient and exact de bruijn graph representation based on a bloom filter. Algorithms Mol. Biol. 2013;8:22. doi: 10.1186/1748-7188-8-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePristo MA, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation dna sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing AD, Kazazian HH., Jr. Whole-genome resequencing allows detection of many rare line-1 insertion alleles in humans. Genome Res. 2011;21:985–990. doi: 10.1101/gr.114777.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajirasouliha I, et al. Detection and characterization of novel sequence insertions using paired-end next-generation sequencing. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1277–1283. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hormozdiari F, et al. Next-generation variationhunter: combinatorial algorithms for transposon insertion discovery. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:i350–i357. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal Z, et al. De novo assembly and genotyping of variants using colored de bruijn graphs. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:226–232. doi: 10.1038/ng.1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd JM, et al. A human genome structural variation sequencing resource reveals insights into mutational mechanisms. Cell. 2010;143:837–847. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, et al. Reprever: resolving low-copy duplicated sequences using template driven assembly. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e128. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and samtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, et al. Soapindel: efficient identification of indels from short paired reads. Genome Res. 2013;23:195–200. doi: 10.1101/gr.132480.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvedev P, et al. Computational methods for discovering structural variation with next-generation sequencing. Nat. Methods. 2009;6(11 Suppl.):S13–S20. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narzisi G, et al. Accurate de novo and transmitted indel detection in exome-capture data using microassembly. Nat. Methods. 2014;11:1033–1036. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabinger S, et al. A survey of tools for variant analysis of next-generation genome sequencing data. Brief. Bioinform. 2013;15:256–278. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish N, et al. Assembly of non-unique insertion content using next-generation sequencing. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12(Suppl. 6):S3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-S6-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salikhov K, et al. Using cascading bloom filters to improve the memory usage for de brujin graphs. Algorithms Bioinformatics. 2013;9:364–376. doi: 10.1186/1748-7188-9-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindi S, et al. A geometric approach for classification and comparison of structural variants. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:i222–i230. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C, et al. A comprehensive map of mobile element insertion polymorphisms in humans. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye K, et al. Pindel: a pattern growth approach to detect break points of large deletions and medium sized insertions from paired-end short reads. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2865–2871. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]