Abstract

Objective

Opportunistic brief in-person Emergency Department (ED) interventions can be effective at reducing hazardous alcohol use in young adult drinkers, but require resources frequently unavailable. Mobile phone text messaging (SMS) could sustainably deliver behavioral support to young adult patients, but efficacy remains unknown. We report 3-month outcome data of a randomized controlled trial testing a novel SMS-delivered intervention in hazardous drinking young adults.

Methods

We randomized 765 young adult ED patients who screened positive for past hazardous alcohol use to one of three groups: SMS Assessments + Feedback (SA+F) intervention who were asked to respond to drinking-related queries and received realtime feedback through SMS each Thursday and Sunday for 12 weeks (n=384); SMS Assessments (SA) who were asked to respond to alcohol consumption queries each Sunday but did not receive any feedback (N=196); and a control group who did not participate in any SMS (n=185). Primary outcomes were number of binge drinking days and number of drinks per drinking day in the past 30 days collected by web-based Timeline Follow-Back method and analyzed with regression models. Secondary outcomes were the proportion of participants with weekend binge episodes and most drinks consumed per drinking occasion over 12 weekends collected by SMS.

Results

Using web-based data, there were decreases in the number of binge drinking days from baseline to 3 months in the SA+F group (-.51 [95% confidence interval {CI} -.10 to -.95]), whereas there were increases in the SA group (.90 [95% CI .23 to 1.6]) and the control group (.41 [95% CI -.20 to 1.0]). There were also decreases in the number of drinks per drinking day from baseline to 3 months in the SA+F group (-.31 [95% CI -.07 to -.55]), whereas there were increases in the SA group (.10 [95% CI -.27 to .47]) and the control group (.39 [95% CI .06 to .72]). Using SMS data, there was a lower mean proportion of SA+F participants reporting a weekend binge over 12 weeks (30.5% [95% CI 25% to 36%) compared to the SA participants (47.7% [95% CI 40% to 56%]). There was also a lower mean drinks consumed per weekend over 12 weeks in the SA+F group (3.2 [95%CI 2.6 to 3.7]) compared to the SA group (4.8 [95% CI 4.0 to 5.6]).

Conclusion

A text message intervention can produce small reductions in binge drinking and the number of drinks consumed per drinking day in hazardous drinking young adults after ED discharge.

Introduction

Background

Each day in the US, over 50,000 young adults 18-24 years of age visit an emergency department (ED).1 A quarter of young adults use the ED for primary care2 and up to a half have hazardous alcohol use patterns3. For these reasons, the ED provides an opportunity to identify young adults with hazardous alcohol use and intervene to prevent associated risks.4 Routine screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT) for hazardous alcohol use is promoted by the American College of Emergency Physicians5 and mandated in Level I trauma centers by the American College of Surgeons6. Despite this recommendation, only around 15% of Level I trauma center EDs incorporate routine SBIRT.7 Numerous barriers exist to widespread implementation8, and brief interventions delivered in the ED setting have produced mixed findings9.

One promising modality that could assist effective delivery of brief interventions for alcohol use, especially among young adult ED patients, is mobile phone text messaging (short message service: SMS). Ninety five percent of young adults own a mobile phone and 97% of these use SMS, either sending or receiving an average of 50 texts per day.10 SMS has been used to promote health in a wide range of young adult health issues, including diabetes11, asthma12, and cigarette smoking13. In theory, SMS-delivered alcohol interventions could reduce the need for training providers to deliver alcohol interventions, provide uniform protocols, reach large numbers of persons, and do so in a cost-efficient manner. Furthermore, a text-message based intervention can reach young adults in the natural environment where they are making drinking choices, potentially increasing saliency. No adequately powered trial published to date has studied the effect of an SMS intervention to reduce alcohol use in young adults.

Goals of this Investigation

We conducted the Texting to Reduce Alcohol Consumption (TRAC) Trial to evaluate the efficacy of a 12-week SMS intervention that encourage lower alcohol consumption, specifically binge drinking (≥5 drinks per occasion for men and ≥4 drinks per occasion for women) among young adults. We focused on reducing binge drinking because of its association with 80,000 deaths in the U.S. each year14 and a range of social problems, such as motor vehicle crashes and interpersonal violence15. We hypothesized that in young adults who screen positive for hazardous drinking, there would be greater reductions in both binge drinking and drinks consumed per drinking episode after exposure to an SMS intervention incorporating weekly SMS drinking Assessments with real-time Feedback (SA+F) compared to SMS drinking Assessments without feedback (SA) or a control condition.

Importance

A text message-delivered intervention that effectively reduces binge drinking could provide a scalable option for EDs to incorporate into SBIRT for hazardous drinking young adults.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

The TRAC trial was a three-arm randomized controlled trial that took place at four urban teaching hospitals in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania including two Level I trauma centers (UPMC Mercy & Presbyterian Hospital) and two non-trauma centers (UPMC Shadyside & Magee Women's Hospital). The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved study procedures. The trial was registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov:NCT01688245 and the protocol is described in detail in a prior publication16.

ED patients aged 18-25 years who presented between 7 am and 1 am, 7 days per week (November 2012-November 2013) identified from the electronic triage log were eligible for screening. Young adults who were medically stable, not seeking treatment for drugs or alcohol, and who gave permission to their emergency physician were approached by research assistants in treatment spaces. Interested patients who speak English and had not been enrolled in any alcohol-related study in the prior year self-administered a 5-minute computerized survey. Patients reporting hazardous alcohol consumption (Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test for Consumption: AUDIT-C scores of ≥3 for women or ≥4 for men)17 were eligible to participate in the trial. Exclusion criteria included the following: past treatment for drug use or psychiatric disorders, no cell phone ownership with text messaging. Patients who met enrollment criteria and who were interested underwent written informed consent. Any patient who screened positive on the AUDIT-C, regardless of eligibility or interest, was offered a list of local alcohol treatment resources.

After providing written informed consent, participants self-administered computerized baseline assessments in the ED, which took an average of 10 minutes to complete ($10 remuneration). Prior to randomization, the research associates checked completion of the baseline survey. Those reporting current high school enrollment were excluded, due to concerns about parental influence on outcomes18. Eligible participants who completed the baseline survey were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 groups: an intervention incorporating weekly SMS drinking-related Assessments with real-time Feedback (SA+F); SMS drinking Assessments (SA); or control. Randomization sequences were allocated in a 2 SA+F: 1 SA: 1 control ratio to allow for more observations in the intervention group to allow for later analysis of mechanisms of change. Randomization was generated in blocks of 8 for each recruitment site by a computer-generated algorithm and allocated electronically. Research associates were blinded to treatment allocation to minimize bias. Participants were told that they could either receive no texts, Sunday texts for 12 weeks or both Thursday and Sunday texts for 12 weeks. Three months after randomization, all participants received text messages and emails with a hyperlink to a web-based follow-up questionnaire ($20 remuneration).

Baseline & Follow-up Assessments

The baseline assessment collected demographic information (e.g., age, sex, race, ethnicity, current school enrollment, living arrangement, and employment status) and substance use severity in the past 3 months using the NIDA Modified Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (NM ASSIST). The NM ASSIST was adapted from the World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST), Version 3.0 (http://www.drugabuse.gov/nmassist/)19. Reasons for ED visits (chief complaint) were taken from the electronic triage dashboard and treating physicians were asked whether ED visits were related to alcohol use.

At baseline and at 3-month follow-up, the Timeline Follow Back (TLFB) procedure20 was used to collect self-report of alcohol use frequency, quantity (on a drinking day), and binge drinking (≥5 drinks for men and ≥4 drinks for women). Using a web-based TLFB calendar21, participants provided retrospective estimates of their daily drinking in the 30 days prior to the assessment. Memory aids were used to enhance recall (e.g., visual calendar with key dates and holidays serve as anchors for reporting drinking; a visual chart of standard drink sizes reduces variability in quantity).

SMS Intervention

The SMS Assessments + Feedback (SA+F) intervention is based on that used in our prior pilot trial22, further developed by a multi-disciplinary team of emergency physicians (BS, CC) and alcohol treatment specialists (DC, PM) using feedback from young adult drinkers. In brief, SA+F aims to increase awareness of drinking intentions and behavior and increase goal-striving and goal-attainment toward reduced alcohol consumption. The SA+F uses elements of the Health Belief Model23, the Information Motivation Behavior model24, and the Theory of Reasoned Action25 and targets the following key determinants of drinking behavior: intention to binge drink, knowledge of health risks associated with binge drinking, norms of drinking by participant age group, skills to reduce binge drinking and goal commitment to avoid a binge day. The style and tone of messages attempted to reflect those used in motivational interviewing26. SMS queries were delivered on Thursday (proximal to typical binge drinking days)27 and on Sunday (to reduce recall bias in recall of weekend drinking behavior)28.

SA+F participants received a series of welcome text messages within 1 hour of enrollment describing what to expect over the course of intervention exposure. Each Thursday, for 12-weeks, they were sent a text asking them to report their weekend drinking plans. If they reported anticipating a heavy drinking day, they were then asked whether they were willing to set a low-risk drinking goal (<5 drinks per occasion for men or <4 drinks per occasion for women). Depending on the response to each query, participants were provided with real-time text feedback to either strengthen their low-risk drinking plan or goal, or alternately, to promote reflection on their drinking plan or decision not to set a low risk goal. Then, on Sunday, participants were sent a text asking them to report the most drinks they had during a single occasion over the weekend. Depending on their response, they were provided with text feedback to either support their low-risk drinking behavior or to promote reflection on their binge-drinking behavior. (For detailed flow chart of the SMS intervention and sample messages, see Appendix).

Participants in the SMS Assessments (SA) group did not receive any pre-weekend text message assessments but received identical text drinking assessments each Sunday for 12-weeks without receiving any alcohol-related feedback. The SA group is critical to separate the effect of the intervention from that associated with potential drinking assessment reactivity from asking participants to report their alcohol consumption each week for 12 weeks.29 Any text message received outside the range of expected responses resulted in an email sent to the investigators to review. Participants in the control condition did not participate in any SMS.

Sample Size

For power consideration, we focused on detecting the difference between SA+F and control groups in binge drinking days at up to 9-months follow-up. Using 3-month outcome data from our pilot trial22, and assuming a 35% reduction in intervention effect at 9-months, we estimated a mean reduction in the number of binge drinking days of 2.0 (SD 5.4) in the intervention group and a reduction of 0 (SD 4.1) in the control group. Assuming an attrition of 35% at 9-months, 750 total participants (375 SA+F: 187 SA: 187 control) were needed to have 80% power to show a difference at significant level = 0.05 based on two-sided two sample test with repeated measures. We included an assessment only (SA) group to allow us to separate the effect of text message feedback from frequent drinking assessments. We allocated participants in a 2 SA+F:1:SA:1 control ratio to allow more observations in the intervention group to allow for future examination of mediators and moderators of effect. Given the automated nature of the intervention, we considered any reduction in binge drinking clinically significant.

Statistical analysis

All analysis was conducted using STATA statistical software, version 13.1. Web-based TLFB data were analyzed as primary outcomes. Number of binge drinking episodes in the past 30 days were analyzed using Zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) regressions due to the data being left skewed with many zero-counts, where the variance is greater than the mean (over-dispersion). Using a mixture distribution method such as a ZIP model solves the problem of zero-count inflation and prevents the zero-counts from dominating the distribution30. Drinks per drinking day over the past 30 days using web-based TLFB data were analyzed using negative binomial regression analysis to handle over-dispersion (where observed variance is larger than expected variance of the count (drinks per drinking day) data.

In each model, we adjusted for covariates shown to be associated with drinking outcomes, including baseline (past 30-day) alcohol consumption31, sex (male; female)32, age (in years)33, race (white; black; other)34, and college enrolled (yes; no)35. We also included site of enrollment (UPMC Mercy; Presbyterian; Shadyside; Magee) as a covariate to control for site differences in patient characteristics. Model fit was determined through Pearson goodness-of-fit tests.

The data were examined for outliers and influential diagnostics. Sensitivity analyses were performed by comparing the results of the regression analyses with bootstrapping (1000 replications using bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals). Similar results were found for regression analyses and bootstrapping, hence, regular regression analyses are reported.

To determine the potential effect of attrition bias, a multiple imputation was performed using fully conditional specification. Both ZIP and negative binomial regressions were performed with an additional predictor (complete or incomplete case). A summary of negative binomial regression through MI ESTIMATE command in STATA generated an average result of 10 imputations. The primary outcomes are presented using listwise deletion and imputation procedures.

Differences in number of binge drinking episodes in the past 30 days between treatment conditions are presented as means and from multivariable models as incident rate ratios (IRRs). IRRs are the incidence for the intervention divided by the incidence rate for the control. An incidence rate ratio is interpreted in a similar fashion to an odds ratio, but is over a discrete time interval of a month (30 days). Differences in class membership for any past 30-day binge episode are presented as odds rate ratios (ORs).

SMS-based weekly data were analyzed as secondary outcomes. The proportions of participants with a weekend binge episode over 12 weekends were analyzed using chi-squared tests and the mean of maximum drinks consumed per drinking occasion over 12 weekends were analyzed using Student's t-tests. All primary and secondary outcomes are presented with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Results

Screening and Randomization

Participant flow is presented in Figure 1. Among 4141 potentially eligible patients presenting during recruitment, 3879 were approached and 3061 completed screening. Patients who completed the screen did not differ in age or sex from those who did not complete it. Of those patients screened, 1103 (36%) scored positive for hazardous drinking. Among those with hazardous drinking, an additional 82 were excluded due to prior treatment for drug or psychiatric disease and no mobile phone ownership. 1021 patients were eligible and 858 (84%) were interested in trial participation and completed informed consent. Females were less likely to refuse participation in the RCT (male, 20.9%; female, 12.8%). Furthermore, African Americans were less likely to refuse than other races/ethnicities (African American, 8.8%; other, 20.5%). Post-enrollment but prior to randomization, an additional 93 were excluded due to incomplete baseline assessments (n=78) or reporting current high school enrollment (n=14). This left 765 patients randomized to the SA+F (n=384) group, SA group (n=196), or control group (n=185). As shown in Table 1, there were no baseline differences between groups on any of the demographic, substance use, and medical variables examined.

Figure 1. CONSORT diagram of patient screening and recruitment.

Abbreviation: MD, medical doctor (Emergency Attending physician); AUDIT-C, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption; SA+F, SMS Assessments with Feedback; SA, SMS Assessments without Feedback.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristics | SA+F (n=384) | SA (n=196) | Control (n=185) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 22.0 (2.0) | 22.0 (2.0) | 21.8 (2.1) |

| Female | 251 (65.4) | 125 (63.8) | 124 (67.0) |

| Race | |||

| African American | 158 (41.2) | 88 (44.9) | 83 (44.9) |

| White | 190 (49.5) | 98 (50.0) | 88 (47.6) |

| Other | 36 (9.4) | 10 (5.1) | 14 (7.6) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 22 (5.7) | 10 (5.1) | 15 (8.1) |

| Current College enrollment | 162 (42.2) | 85 (43.4) | 87 (47.0) |

| Living arrangements | |||

| Live alone | 88 (22.9) | 41 (20.9) | 29 (15.7) |

| Friends, same sex | 116 (30.2) | 44 (22.4) | 49 (26.5) |

| Friends, other sex | 42 (10.9) | 29 (14.8) | 22 (11.9) |

| Parents or family | 138 (35.9) | 82 (41.8) | 85 (46.0) |

| Employment | |||

| None | 120 (31.2) | 62 (31.6) | 61 (33.0) |

| Part-time | 110 (28.7) | 59 (30.1) | 62 (33.5) |

| Full-time | 154 (40.1) | 75 (38.3) | 62 (33.5) |

| AUDIT-C score, mean (SD) | 6.3 (2.2) | 6.3 (2.2) | 6.2 (2.1) |

| Other Substance Use last 3 months | |||

| Daily or almost daily tobacco | 145 (37.8) | 72 (36.7) | 64 (34.6) |

| Any cannabis | 197 (51.3) | 94 (50.0) | 95 (51.4) |

| ED Chief Complaint | |||

| Minor trauma/ Musculoskeletal | 88 (22.9) | 43 (21.9) | 38 (20.5) |

| Neuro/Syncope | 18 (4.7) | 9 (4.6) | 14 (7.6) |

| Abdominal pain/ Urogenital | 96 (25.0) | 43 (21.9) | 54 (29.2) |

| Eye/ENT/Dental | 29 (7.6) | 11 (5.6) | 11 (6.0) |

| Cardiac/ Respiratory | 20 (5.2) | 17 (8.7) | 14 (7.6) |

| Other | 133 (34.6) | 73 (37.2) | 53 (29.2) |

| ED Visit Due to Alcohol | 12 (3.1) | 3 (1.5) | 4 (2.2) |

Abbreviation: SA+F, SMS Assessments with Feedback; SA, SMS Assessments without Feedback; AUDIT-C, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption; ENT, Ear, Nose & Throat. Data are expressed as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Text Message Response Rates

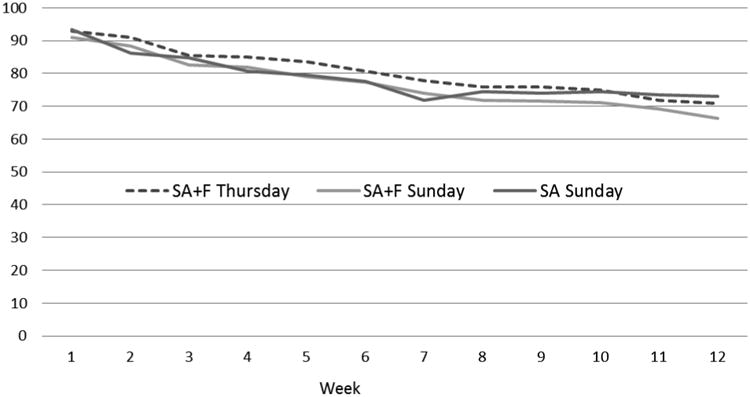

Overall, the mean percentage of SA+F participants responding to Thursday SMS queries was 81% (95% CI 77% to 85%), with the responses decreasing from 93% (95% CI 90% to 95%) on week 1 to 71% (95% CI 66% to 76%) on week 12 (Figure 2). The mean percentage of SA+F participants responding to Sunday SMS queries was 77% (95% CI 73% to 81%), with the responses decreasing from 91% (95% CI 88% to 94%) on week 1 to 66% (95% CI 61% to 71%) on week 12. Overall, the mean percentage of SA participants responding to Sunday SMS queries was 79%, with responses decreasing from 93% on week 1 to 73% on week 12, with no differences in attrition from the SA+F group.

Figure 2. Percentage of Participants Responding to SMS Queries.

Abbreviation: SA+F, SMS Assessments with Feedback; SA, SMS Assessments without Feedback.

Web-based Follow-up Assessment

Follow-up data were obtained through web-based surveys from 598 participants (78%) at 3-months. There were no differences in attrition among treatment conditions, with follow-up in SA+F at 76% (95% CI 71%-80%), SA at 82% (95% CI 75%-87%) and control at 80% (95% CI 74%-86%). Compared to participants who completed follow-up, those lost-to-follow-up were more likely to be African American (54% vs. 40%), not currently enrolled in college (72% vs. 50%), and with baseline higher number of binge days (mean (SD): 5.1 (6.2) vs. 3.5 (2.9)).

Web-Based TLFB Binge Drinking

Using web-based data, there were decreases in the number of binge drinking days from baseline to 3 months in the SA+F group (-.51 [95% confidence interval {CI} -.10 to -.95]), whereas there were increases in the SA group (.90 [95% CI .23 to 1.6]) and the control group (.41 [95% CI -.20 to 1.0]). There were also decreases in the number of drinks per drinking day from baseline to 3 months in the SA+F group (-.31 [95% CI -.07 to -.55]), whereas there were increases in the SA group (.10 [95% CI -.27 to .47]) and the control group (.39 [95% CI .06 to .72]).

There were decreases in the number of binge drinking days from baseline to 3 months in the SA+F group (-.51 [95% confidence interval {CI} -.10 to -.95]), whereas there were increases in the SA group (.90 [95% CI .23 to 1.6]) and the control group (.41 [95% CI -.20 to 1.0]). (Table 2). The ZIP regression model predicting number of binge drinking days at 3-months indicated a significant difference among the 3 study conditions. Using listwise deletion, participants in SA+F had no reductions (IRR 0.91 (95% CI 0.82 to 1.02) in binge drinking days in the past 30 days at follow-up compared to control participants. Using multiple imputation, participants in SA+F also showed no reductions (IRR 0.99 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.05) in binge drinking days in the past 30 days at follow-up compared to control participants.

Table 2. Changes in Mean Binge Drinking Days and Drinks per Drinking Day; Baseline to 3-Month Follow-up.

| Baseline | 3-Months | Change | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | 95% CI | mean | 95% CI | mean | 95% CI | ||

| No. binge drinking days | |||||||

| SA+F | 3.7 | 3.2, 4.2 | 3.1 | 2.6, 3.6 | -.51 | -.95, -.10 | |

| SA | 3.3 | 2.6, 4.0 | 4.2 | 3.3, 5.1 | .90 | .23, 1.6 | |

| Control | 3.2 | 2.6, 3.8 | 3.6 | 2.9, 4.3 | .41 | -.20, 1.0 | |

| No. drinks per drinking day | |||||||

| SA+F | 3.8 | 3.6, 4.0 | 3.5 | 3.3, 3.7 | -.31 | -.55, -.07 | |

| SA | 4.0 | 3.6, 4.4 | 4.2 | 3.8, 4.6 | .10 | -.27, .47 | |

| Control | 3.6 | 3.3, 3.9 | 4.0 | 3.6, 4.4 | .39 | .06, .72 | |

Abbreviation SA+F, SMS Assessments with Feedback; SA, SMS Assessments without Feedback; No., number; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

There were greater reductions in the proportion of participants with any binge drinking in the last 30 days from baseline to 3 months in the SA+F group (-14.5% [95% CI -11% to -19%]) compared to the SA group (-3.1% [95% CI -1% to -7%]) and the control group (-2.0% [95% CI -1% to 6%]) (Table 3). For the model predicting no binge drinking in the last 30 days at 3-months, there was a significant difference among the 3 study conditions. Using listwise deletion, participants in SA+F were 2.4 (95% CI 1.39 to 4.14) times more likely to not report any binge drinking in the last 30 days at follow-up than the control participants. Using multiple imputation, participants in SA+F were 2.09 (95% CI 1.28 to 3.40) times more likely to not report any binge drinking in the last 30 days at follow-up than the control participants.

Table 3. Changes in Percent of Participants Reporting Any Binge Drinking; Baseline to 3-Month Follow-up.

| Baseline | 3-Months | Change | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | ||

| Participants with any binge drinking day | SA+F | 79.3 | .74, .84 | 64.8 | .59, .70 | 14.5 | .11, .19 |

| SA | 78.1 | .78, .81 | 75.0 | .68, .81 | 3.1 | .01, .07 | |

| Control | 79.7 | .72, .86 | 77.7 | .70, .84 | 2.0 | .01, .06 | |

Abbreviation SA+F, SMS Assessments with Feedback; SA, SMS Assessments without Feedback; No., number; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

There were several covariates associated with binge drinking outcomes at 3-months. As may be expected, a higher number of binge drinking days at baseline was associated with a higher number of binge days at 3-months (IRR 1.09 [95% CI 1.08 to 1.10]) and lower odds of reporting no binge drinking days (OR 0.71 [95% CI 0.65 to 0.78]). Compared to whites, African Americans had fewer binge drinking days (IRR 0.85 [95% CI 0.77 to 0.95]) and were more likely to report having no binge drinking days (OR 2.42 [95% CI 1.53 to 3.82]) at follow-up. Those enrolled in college were less likely to report no binge drinking days at follow-up compared to those not in college (OR=0.48 [95% CI 0.30 to 0.76]).

Web-Based TLFB Drinks per Drinking Day

There were also decreases in the number of drinks per drinking day from baseline to 3 months in the SA+F group (from 3.8 [95%CI 3.6 to 4.0] to 3.5 [95% CI 3.3 to 3.7]), whereas there were increases in the SA group (from 4.0 [95% CI 3.6 to 4.4] to 4.2 [95% CI 3.8 to 4.6]) and the control group (from 3.6 [95% CI 3.3 to 3.9] to 4.0 [95% CI 3.6 to 4.4]). (Table 2). For the model predicting number of drinks per drinking day, there was a significant difference across the 3 study conditions. Using listwise deletion, participants in SA+F had fewer drinks per drinking day at 3-months than control (IRR 0.86 [95% CI 0.79 to 0.94]). Using multiple imputation, the reductions in drinks per drinking day became non-significant (IRR 0.91 [95% CI 0.79 to 1.05]).

SMS-Based Weekend Binge Drinking & Max Drinks

On average, there were fewer SA+F participants reporting a weekend binge over 12 weeks (30.5% [95% CI 25% to 36%) compared to the SA participants (47.7% [95% CI 40% to 56%]). The differences reached statistical significance by week 3, and remained different through week 12, as shown in Figure 3. There were also less drinks consumed per weekend in the SA+F group over 12 weeks (3.2 [95%CI 2.6 to 3.7]) compared to the SA group (4.8 [95% CI 4.0 to 5.6]). The differences reached statistical significance by week 3, and remained different through week 12, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3. Percentage of Participants Reporting Weekend Binge Drinking through SMS.

Abbreviation: SA+F, SMS Assessments with Feedback; SA, SMS Assessments without Feedback. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 4. Maximum Drinks Consumed per Weekend reported through SMS.

Abbreviation: SA+F, SMS Assessments with Feedback; SA, SMS Assessments without Feedback. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals of mean drinks.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is that it is not possible for participants to be blinded to the intervention condition. We attempted to minimize this effect by concealing condition allocation from participants in the ED. Findings may not generalize to patient groups not included in this single-city study, such as young adults presenting with a history of treatment for drugs or psychiatric disease or those who present to the ED with an alcohol-related visit. The self-report data are a potential limitation; however, reviews support the reliability and validity of self-report of risk behaviors when privacy/confidentiality is ensured36 and when using self-administered computerized assessments37. Our use of weekly (weekend) SMS in addition to web-based 30-day recall for recording self-reported drinking outcomes makes the possibility of reporting bias less likely.

The follow-up rate of 78% at 3-months and differential loss-to-follow-up among heavier drinkers may introduce attrition bias. We note, however, that less than half of all published ED-based brief intervention studies for alcohol achieve 80% follow-up, with dropout rates as high as 40% at comparable follow-up time periods.9 Further, we included relevant covariates in our primary analyses and performed sensitivity analyses using imputation procedures to help mitigate possible effects of attrition. When imputation for loss to follow-up and missing data was performed, the reduction in binge drinking days and drinks per drinking day became non-significant. We did not examine alcohol-related harm (i.e. drunk driving) as an outcome, given that our intervention did not directly attempt to modify alcohol-related risk behavior. Finally, we did not examine the potential degradation of effects over time.

Discussion

A text message intervention for young adults who screened positive for hazardous drinking produced small reductions in binge drinking and the drinks consumed per drinking episode up to 3-months after ED discharge. These results were consistent across outcomes measured through web-based calendar recall and weekly SMS reports, but were smaller than those found in our pilot trial, and vulnerable to attrition bias.

There are few ED-based studies that have examined effects of interventions targeting young adults40. In 2008, Monti et al.41, demonstrated that an in-person motivational interview with 87 young adults who present with a positive blood alcohol content can result in alcohol consumption reductions at 6-months post ED discharge. In 2012, D'Onofrio et al.42 showed that a brief negotiated interview with hazardous drinkers can reduce alcohol consumption at 6- and 12-months post ED discharge, but that these effects were not significant in young adults. The effect size of the text message intervention on binge drinking (Cohen's d= 0.22; 95% CI .02 to .42) was smaller than those found in a meta-analysis of in-person brief interventions for alcohol consumption at ≤3 months (Cohen's d=.67; 95% CI 0.39 to 0.95)38, but comparable to those found in a meta-analysis of interventions to reduce binge drinking among first-year college students (Cohen's d=.13; 95% CI .05 to .21)39. Although the effect sizes of the text message program are relatively small, achieving even modest reductions among a large group of drinkers could result in greater gains relative to more expensive efforts among a smaller number of drinkers43.

Still, we recognize that the SMS intervention may not be optimized. Although the participation rates were fairly high, and comparable to other SMS intervention44, 45, they decreased significantly over 12 weeks. Future mobile interventions may need to incorporate additional components to keep young adults engaged at higher rates. To improve efficacy, future SMS interventions may need to incorporate other behavioral techniques found to be useful for alcohol prevention and/or provide them with greater intensity or longer periods. Finally, given that 50% of enrolled young adults had used cannabis in the past 3 months suggests that SMS interventions may need to address multiple drug use.

We did not show a significant reduction in drinking variables in the non-intervention groups (SA, control) from baseline to 3-month follow-up. This finding is contrary to prior research showing that drinking assessments alone can result in reductions in drinking behavior29, but consistent with our pilot trial22. For the control condition, this suggests that the self-awareness of being a hazardous drinker and being asked to report alcohol use at baseline does reduce alcohol use. For the SA condition, this supports prior ecological momentary assessment research suggesting that awareness of behavior alone may not result in significant “assessment reactivity” or behavior change46. Our observation of potential increases in alcohol use in the control conditions is consistent with the natural developmental escalation of alcohol use for some drinkers in this age range47.

We identified some patient characteristics that were associated with 3-month binge drinking outcome. For example, similar to prior studies48,49, greater baseline alcohol severity was associated with worse outcome. Being African American was associated with better binge drinking outcomes at 3-months than being white. This finding warrants further study of race being a possible moderator of intervention effects on alcohol outcomes.

In summary, although a replication that includes longer follow-up is required, findings of this large RCT support the short-term efficacy of a text message intervention in producing small reductions in binge drinking and alcohol consumption among young adult hazardous drinkers. Text message approaches could be integrated into current SBIRT for young adults, with potential applicability across other risk behaviors (e.g., drug use, unprotected sex, interpersonal violence).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The study was supported by an Emergency Medicine Foundation Grant. T. Chung is supported by K02 AA018195.D. Clark is supported by R01AA016482 and P50DA05605. Dr. Monti is supported by K05 AA019681 and P01 AA019072. D. Clark is supported by R01AA016482 and P50DA05605 and PA-HEAL SPH00010.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov:NCT01688245

Meetings: Preliminary findings were presented at the American Public Health Association's 141st Annual Meeting and Exposition; Nov 6, 2013.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: No conflicts of interest are reported.

Author contributions: BS conceived the study, designed the trial, and obtained research funding. BS, JK, CWC, and DBC supervised the conduct of the trial and data collection. BS and JK undertook recruitment of participating centers and patients and managed the data, including quality control. KHK, TC and PMM provided statistical advice on study design and analyzed the data; CWC chaired the data oversight committee. BS drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. BS takes responsibility for the paper as a whole

Additional Contributions: We express deep gratitude to Jack Doman at the Office of Academic Computing at Western Psychiatric Hospital for his elegant programming of the web-based and text-message software. We thank the research associates, especially Sandra Truong and Sydney Huerbin. We thank all the physicians and nurses from the emergency departments of all participating centers and Department Directors Mike Turturro, Charissa Pacella and Maria Guyette. We also thank Maureen Morgan and Beth Wesoloski for their administrative support.

Citations

- 1.Schappert SM, Rechtsteiner EA. Ambulatory medical care utilization estimates for 2006. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008;(8):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fortuna RJ, Robbins BW, Mani N, Halterman JS. Dependence on emergency care among young adults in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2010 Jul;25(7):663–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1313-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly TM, Donovan JE, Chung T, Bukstein OG, Cornelius JR. Brief screens for detecting alcohol use disorder among 18-20 year old young adults in emergency departments: Comparing AUDIT-C, CRAFFT, RAPS4-QF, FAST, RUFT-Cut, and DSM-IV 2-Item Scale. Addict Behav. 2009 Aug;34(8):668–74. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernstein E, Bernstein JA, Stein JB, Saitz R. SBIRT in emergency care settings: are we ready to take it to scale? Acad Emerg Med. 2009 Nov;16(11):1072–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alcohol Screening in the Emergency Department. [Accessed 11/01/12]; Approved April 2011. Revised and approved by the ACEP Board of Directors April 2011. http://www.acep.org/Clinical---Practice-Management/Alcohol-Screening-in-the-Emergency-Department/

- 6.Gentilello LM. Alcohol and injury: American College of Surgeons Committee on trauma requirements for trauma center intervention. J Trauma. 2007 Jun;62(6 Suppl):S44–5. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3180654678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham RM, Harrison SR, McKay MP, Mello MJ, Sochor M, Shandro JR, Walton MA, D'Onofrio G. National survey of emergency department alcohol screening and intervention practices. Ann Emerg Med. 2010 Jun;55(6):556–62. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark DB, Moss HB. Providing alcohol-related screening and brief interventions to adolescents through health care systems: obstacles and solutions. PLoS Med. 2010 Mar 9;7(3):e1000214. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Havard A, Shakeshaft A, Sanson-Fisher R. Systematic review and meta-analyses of strategies targeting alcohol problems in emergency departments: interventions reduce alcohol-related injuries. Addiction. 2008 Mar;103(3):368–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02072.x. discussion 377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith A. Americans and Text messaging. Pew Research Center; Washington, D.C: 2011. [Accessed 11/1/2012]. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/Cell-Phone-Texting-2011.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franklin VL, Waller A, Pagliari C, Greene SA. A randomized controlled trial of Sweet Talk, a text-messaging system to support young people with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2006 Dec;23(12):1332–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prabhakaran L, Chee WY, Chua KC, Abisheganaden J, Wong WM. The use of text messaging to improve asthma control: a pilot study using the mobile phone short messaging service (SMS) J Telemed Telecare. 2010 Jul;16(5):286–90. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.090809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodgers A, Corbett T, Bramley D, Riddell T, Wills M, Lin RB, Jones M. Do u smoke after txt? Results of a randomised trial of smoking cessation using mobile phone text messaging. Tob Control. 2005 Aug;14(4):255–61. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.011577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CDC. Alcohol-related disease impact (ARDI) [Accessed 11/01/12]; www.cdc.gov/alcohol/ardi.htm.

- 15.Hingson RW, Edwards EM, Heeren T, Rosenbloom D. Age of drinking onset and injuries, motor vehicle crashes, and physical fights after drinking and when not drinking. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009 May;33(5):783–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00896.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suffoletto B, Callaway CW, Kristan J, Monti P, Clark DB. Mobile phone text message intervention to reduce binge drinking among young adults: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013 Apr 3;14:93. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Frank D, Kivlahan DR. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007 Jul;31(7):1208–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van der Vorst H, Engels RCME, Meeus W, Deković M. The impact of alcohol-specific rules, parental norms about early drinking and parental alcohol use on adolescents' drinking behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:1299–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor TF, Farrell M, Formigoni ML, Jittiwutikarn J, de Lacerda RB, Ling W, Marsden J, Monteiro M, Nhiwatiwa S, Pal H, Poznyak V, Simon S. Validation of the Alcohol, Smoking And Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) Addiction. 2008 Jun;103(6):1039–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline followback: A technique for assessing self reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen J, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. New Jersey: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rueger SY, Trela CJ, Palmeri M, King AC. Self-administered web-based timeline followback procedure for drinking and smoking behaviors in young adults. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012 Sep;73(5):829–33. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suffoletto B, Callaway CW, Kraemer K, Clark DB. Text-Message-Based Drinking Assessments and Brief Interventions for Young Adults Discharged from the Emergency Department. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012 Mar;36(3):552–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. Social learning theory and the Health Belief Model. Health Educ Q. 1988 Summer;15(2):175–83. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:455–474. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller WR. Motivational interviewing: research, practice, and puzzles. Addict Behav. 1996 Nov-Dec;21(6):835–42. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(96)00044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Del Boca FK, Darkes J, Greenbaum PE, Goldman MS. Up close and personal: temporal variability in the drinking of individual college students during their first year. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004 Apr;72(2):155–64. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Searles JS, Helzer JE, Walter DE. Comparison of drinking patterns measured by daily reports and timeline follow back. Psychol Addict Behav. 2000 Sep;14(3):277–86. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.3.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCambridge J, Kypri K. Can simply answering research questions change behaviour? Systematic review and meta analyses of brief alcohol intervention trials. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e23748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu H, Powers DA. Growth curve models for zero-inflated count data: an application to smoking behavior. Struct Equat Model. 2007;14:247–279. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spirito A, Monti PM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Sindelar H, Rohsenow DJ, Lewander W, Myers M. A randomized clinical trial of a brief motivational intervention for alcohol-positive adolescents treated in an emergency department. J Pediatr. 2004 Sep;145(3):396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blow FC, Barry KL, Walton MA, Maio RF, Chermack ST, Bingham CR, Ignacio RV, Strecher VJ. The efficacy of two brief intervention strategies among injured, at-risk drinkers in the emergency department: impact of tailored messaging and brief advice. J Stud Alcohol. 2006 Jul;67(4):568–78. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masten AS, Faden VB, Zucker RA, Spear LP. Underage drinking: a developmental framework. Pediatrics. 2008 Apr;121(Suppl 4):S235–51. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen CM, Dufour MC, Yi H. Alcohol consumption among young adults ages 18–24 in the United States: Results from the 2001–2002 NESARC survey. Alcohol Research and Health. 2004/2005;28(4):269–280. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slutske WS. Alcohol use disorders among US college students and their non-college-attending peers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Mar;62(3):321–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brener ND, Billy JO, Grady WR. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health-risk behavior among adolescents: evidence from the scientific literature. J Adolesc Health. 2003 Dec;33(6):436–57. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rueger SY, Trela CJ, Palmeri M, King AC. Self-administered web-based timeline followback procedure for drinking and smoking behaviors in young adults. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012 Sep;73(5):829–3. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moyer A, Finney JW, Swearingen CE, Vergun P. Brief interventions for alcohol problems: a meta-analytic review of controlled investigations in treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking populations. Addiction. 2002;97:279–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey KB, Elliott JC, Garey L, Carey MP. Efficacy of alcohol interventions for first-year college students: a meta-analytic review of randomized controlled trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014 Apr;82(2):177–88. doi: 10.1037/a0035192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taggart IH, Ranney ML, Howland J, Mello MJ. A systematic review of emergency department interventions for college drinkers. J Emerg Med. 2013 Dec;45(6):962–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monti PM, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Gwaltney CJ, Spirito A, Rohsenow DJ, Woolard R. Motivational interviewing versus feedback only in emergency care for young adult problem drinking. Addiction. 2007 Aug;102(8):1234–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.D'Onofrio G, Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Owens PH, Degutis LC, Busch SH, Bernstein SL, O'Connor PG. A brief intervention reduces hazardous and harmful drinking in emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2012 Aug;60(2):181–92. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rose G. Strategy of prevention: lessons from cardiovascular disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981 Jun 6;282(6279):1847–51. doi: 10.1136/bmj.282.6279.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weitzel JA, Bernhardt JM, Usdan S, Mays D, Glanz K. Using wireless handheld computers and tailored text messaging to reduce negative consequences of drinking alcohol. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007 Jul;68(4):534–7. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Irvine L, Falconer DW, Jones C, Ricketts IW, Williams B, Crombie IK. Can text messages reach the parts other process measures cannot reach: an evaluation of a behavior change intervention delivered by mobile phone? PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e52621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hufford MR, Shields AL, Shiffman S, Paty J, Balabanis M. Reactivity to ecological momentary assessment: an example using undergraduate problem drinkers. Psychol Addict Behav. 2002 Sep;16(3):205–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jackson KM, Sher KJ, Schulenberg JE. Conjoint developmental trajectories of young adult substance use. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008 May;32(5):723–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00643.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vasilaki EI, Hosier SG, Cox WM. The efficacy of motivational interviewing as a brief intervention for excessive drinking: a metaanalytic review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:328–35. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adamson SJ, Sellman JD, Frampton CM. Patient predictors of alcohol treatment outcome: a systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009 Jan;36(1):75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.