Abstract

Background

Immunosuppressive (IS) therapy is indicated to treat progressive sarcoidosis, but randomized controlled trials to guide physicians in the use of steroid sparing agents are lacking. The aim of this retrospective study was to examine the role of Mycophenolate Mofetil (MMF) as an alternative therapy in the treatment of sarcoidosis.

Methods

A retrospective chart review of all patients who had been prescribed MMF between January 2008 and October 2011 was conducted. Patients with insufficient data or who had another IS therapyinitiated concomitantly with MMF, including prednisone, were excluded. Physiological data obtained at the time MMF therapy was initiated as well as six and twelve months before and after therapy was extracted. Longitudinal analyses of the effect of MMF on changes in pulmonary function at MMF start, 6 months, 12 months pre and post MMF therapy were conducted.

Results

37/76 patients met our inclusion/exclusion criteria. There were no statistically significant changes in PFT measurements pre and post MMF therapy. We did find a trend (p=0.07) towards improvement in DLCO 12 months pre and post MMF in patients who were started on MMF due to intolerance to previous IS therapy compared to those who were unresponsive to their previous IS therapy. We also noted a reduction in prednisone dose in those treated with MMF.

Conclusion

MMF appears to offer no extra benefit to sarcoidosis patients unresponsive to previous steroid-sparing agents, but may be beneficial in patients intolerant to their previous steroid-sparing agent. Additional studies investigating the efficacy of MMF as the initial steroid-sparing agent are needed to further clarify the role of MMF in sarcoidosis.

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a multi-system granulomatous disorder with lung involvement in over 90% of cases1. Immunosuppressive therapy is indicated when there is evidence of disease progression and/or when organ dysfunction is present1. A Cochrane review investigating the role of immunosuppressive therapy in sarcoidosis reported that there is a paucity of studies on the role of steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents in sarcoidosis2. Corticosteroids are generally the first line therapy in sarcoidosis and are often effective in the short term management of pulmonary sarcoidosis. In addition, there is little evidence that corticosteroids modify long term disease progression3,4 and they are fraught with numerous and debilitating side effects5.

Steroid sparing agents are used in sarcoidosis patients who require long term therapy to control their disease and to minimize the side effects and complications of corticosteroid therapy6. Methotrexate is the most commonly chosen steroid-sparing drug in sarcoidosis,7 with an estimated efficacy of about 47% for improvement in lung disease8. Patients occasionally do not tolerate methotrexate due to various side effects8. Two case series suggested a beneficial effect for leflunomide, another steroid-sparing agent, in sarcoidosis9,10. Azathioprine is less commonly used in the management of sarcoidosis.7 A retrospective study that compared outcomes between patients treated with methotrexate versus azathioprine showed similar physiological responses but a higher risk of infection with azathioprine11. Biological agents, specifically anti-tumor necrosis alpha (TNF-α) agents, are considered third line therapeutic agents to manage sarcoidosis after patients have failed first and second line agents6.

There is only one small study of n=10 subjects published evaluating the efficacy of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) in sarcoidosis, suggesting that MMF might be used as a steroid-sparing agent12. Based on other studies, MMF appears to be a safe and effective treatment for connective tissue disease associated interstitial lung diseases (CTD-ILD) and is becoming first line therapy for these diseases13,14. As a result of this experience, our clinical sarcoidosis group has used MMF an alternative steroid sparing agent in sarcoidosis patients who are intolerant to or have failed to respond to methotrexate or other immunosuppressive agents. The goal of our study was to retrospectively evaluate the efficacy of MMF in the management of sarcoidosis patients failing or intolerant to their previous immunosuppressive regimen.

Methods

Utilizing a retrospective chart review method, all sarcoidosis patients who were prescribed MMF between January 2008 and October 2011 were identified through a search of the ICD-9 codes for sarcoidosis using the National Jewish Health (NJH) electronic medical record database and our sarcoidosis research database. Subjects had to meet the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) diagnostic criteria for sarcoidosis1 requiring biopsy confirmation of granulomatous inflammation and exclusion of other potential causes of sarcoidosis; cases of Lofgren's were an exception as diagnosis is based on clinical criteria. In addition, all cases were required to have been treated with MMF therapy for a minimum of 6 months and previously with another steroid sparing immunosuppressive agent with or without corticosteroids for a minimum of six months. MMF was started at the discretion of the treating physician and not based on specific protocols or criteria. Those subjects who were started on another immunosuppressive therapy, including prednisone, at the time that MMF was initiated or whose dose of another immunosuppressant was escalated at the time that MMF was started were excluded from this study. Subjects were also excluded if they were on MMF therapy for less than 6 months or lacked medical record documentation of treatment for at least 6 months.

Once subjects met the above inclusion and exclusion criteria, the following data was extracted from the medical record for each subject: demographics (age, gender, race and smoking status); corticosteroid dose at MMF initiation, 3 and 6 months after MMF initiation; immunosuppressive (IS) regimen from six months before and up to the time MMF was administered; indication for initiation of MMF, including target organ(s) that necessitated treatment with MMF; duration of disease; organ involvement based on the assessment of the treating physician; and side effects attributed to the immunosuppressive therapy. In addition, physiologic data was abstracted including pulmonary function test (PFT) data (forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), ratio of forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC), total lung capacity (TLC), diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO), and diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide adjusted for alveolar volume (DLCO/VA) absolute values) at 12 and 6 months pre and post therapy with MMF and at time of MMF initiation, allowing a one month window for obtaining lung function data. All PFTs were performed according to ATS standard criteria15. The side effect profile of MMF in the study population was extracted from the clinic notes. This protocol was approved by the NJH Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was waivered due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Statistical Analysis

The effect of MMF on lung function was the primary outcome of this study, and was assessed by comparing the changes in FVC and DLCO from pre MMF treatment to the most recent post MMF treatment. We focused our analysis on FVC and DLCO as these two measurements are frequently used to assess functionally important pulmonary changes in sarcoidosis16. A paired t-test was used to assess the mean changes in FVC and DLCO pre and post MMF therapy. Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank tests were used to compare changes in corticosteroid dose from MMF start to 6 months and to 12 months post MMF start.

In addition, as we had longitudinal data for analysis, linear mixed models (LMMs) were used to account for the longitudinal nature of this study. The outcomes of interest were the following PFT parameters: FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC, TLC, DLCO, and DLCO/VA using absolute values. The predictors of interest were visit (12 months pre-MMF therapy (-2), 6 months pre-MMF therapy (-1), MMF start (0), 6 months post-MMF therapy (1) and 12 months post-MMF therapy (2)), group (methotrexate intolerance due to side effects vs. treatment failure based on the assessment of the treating physician), and the interaction between visit and group. Also included in the model was a spline term at the time of MMF administration (visit=0), and an interaction between the spline term and group. The spline term allowed the slope before and after the time of MMF administration to differ. Visit was treated as a continuous variable in order to include the spline term in the model. The following covariates were included in all models: age, gender, race (Caucasian, Not Caucasian), smoking (former, never), and indication for IS therapy (lung, other organ system involvement with sarcoidosis). In order to account for repeated measures in this study, different covariance structures were considered, such as Compound Symmetric (CS) and First-order Autoregressive (AR-1), and the covariance structure that led to the best model fit was chosen. As such, all the LMMs contained the CS covariance matrix. Random intercepts were included in all models where possible (some models did not converge on a solution with the random intercept). All analyses were run using SAS version 9.2.

Results

Patient Characteristics

We identified a total of 76 sarcoidosis patients who were prescribed MMF between January 2008 and October 2011 at NJH. Of these, 39 patients were excluded from analysis; of these 19 had another immunosuppressive (IS) agent started at the same time MMF was started, six did not tolerate MMF and stopped it within one month and 14 had inadequate PFT data for analysis. The final population used in this study consisted of 37 sarcoidosis patients (Table 1). The main difference between the cohorts was the baseline immunosuppressive therapy, as the subjects who were excluded were more likely to be on no therapy prior to starting MMF (23.1% vs 0.05%) and to be started on MMF and prednisone simultaneously as initial therapy.

Table 1.

Study Population Characteristics.

| Eligible study cohort n=37 | Ineligible study cohort n=39 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age, years ±SD | 54 ± 11 | 53 ± 12(* missing data n=4) | ns |

|

| |||

| Male % | 56.8 | 56.4 | ns |

|

| |||

| Race % | |||

| - Caucasian | 73.0 | 69.2 | ns |

| - African American | 21.6 | 18 | |

| - Other | 5.4 | 12.8 | |

|

| |||

| Smokers % (A/F/N) | 0 / 32.4 / 67.6 | 0 / 25.6 / 74.4 | ns |

|

| |||

| Pre-MMF immunosuppressive therapy* %(n) | Prednisone 75.7 (28) | Prednisone 61.5 (24) | <0.05 |

| Methotrexate 70.3 (26) | Methotrexate 33.3 (13) | ||

| No therapy 0.05 (2) | No therapy 23.1 (9) | ||

| Hydroxychloroquine 0.05 (2) | Hydroxychloroquine 0.05 (2) | ||

| Azathioprine 0.03 (1) | Leflunomide 0.03 (1) | ||

Abbreviations: ns: not significant, SD: Standard deviation, A/F/N: Active/Former/Never. N/A: Not applicable, IS: Immunosuppressive, MMF: Mycophenolate Mofetil

most patients were on combination therapy

The study cohort (n=37) was predominantly male, Caucasian and never smokers. Pulmonary involvement was the main indication for IS therapy (75.7% for the study cohort, 71.4% in the treatment failure group and 81.3% in the treatment intolerant group). The treating physician's assessment of lack of efficacy of the previous IS regimen was the main reason patients were started on MMF (56.8%). There was no difference in the mean duration of disease from time of initial diagnosis to time of MMF treatment between the intolerant group and the treatment failure group (mean 69.63±66.43 vs 53.25±31.99 months respectively, p=0.33). The majority of patients were on combined therapy; 75.7% of patients were on prednisone, 70.3% were on methotrexate initially, two patients were on hydroxychloroquine, and one patient was on azathioprine. The average MMF dose used was 2,236 mg in twice-daily divided doses (32.4% were on 3000 mg daily, 59.5% were on 2000 mg daily, and 8.1% were on 1500 mg or less daily).

MMF may impact lung function in those intolerant to methotrexate

We initially compared the difference in mean change in absolute values of FVC and DLCO at 6 months before and after starting MMF therapy and at 12 months before and after starting MMF therapy. There were no statistically significant changes in absolute FVC and/or DLCO at either time point. However, change in DLCO 12 months after starting MMF therapy compared to 12 months before starting MMF therapy showed a trend towards an increase in the entire cohort (p=0.07) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Changes in pulmonary physiology before and after therapy with MMF:

| Cohort | FVC (L) Δ pre-MMF, Δ post-MMF Diff (SD), p value | DLCO (L) Δ pre-MMF, Δ post-MMF Diff (SD), p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire cohort | 6 months -0.047,-0.118 0.071 (0.53), 0.47 n=29 | 12 months -0.057,-0.015 0.042 (0.45), 0.62 n=29 | 6 months 0.30,-0.02 -0.32(3.15), 0.72 n= 13 | 12 months -1.65,0.08 1.74 (3.33), 0.07 n=14 |

| Pulmonary Indication for IS Therapy | 6 months -0.07,-0.10 -0.02 (0.52), 0.86 n=19 | 12 months -0.10,-0.04 0.07 (0.51), 0.59 n=18 | 6 months 0.39,0.15 -0.24 (2.97), 0.79 n=11 | 12 months -1.60,-0.21 1.39 (3.23), 0.21 n=10 |

| Treatment Failure | 6 months 0.01,-0.18 -0.19 (0.52), 0.28 n=17 | 12 months -0.02,-0.04 -0.02 (0.34), 0.84 n=18 | 6 months 0.02,0.63 0.61 (3.28), 0.61 n=8 | 12 months -1.51,0.41 1.1 (3.34), 0.35 n=9 |

| Intolerance to Current Therapy | 6 months -0.15,-0.02 0.12 (0.49), 0.43 n=11 | 12 months -0.12,0.02 0.14 (0.6), 0.47 n=11 | 6 months 0.75,-1.06 -1.82 (2.54), 0.18 n=5 | 12 months -1.92,0.96 2.87 (3.35), 0.13 n=5 |

Abbreviations: MMF: Mycophonelate Mofetil, Δ pre-MMF: change in value from time point before starting MMF to start of MMF, Δ post-MMF: change in value from starting MMF to time point after starting MMF. Diff: Difference, SD: standard deviation.

We subsequently divided and analyzed the cohort by subgroups. First, we divided the cohort based on the organ system indication for IS therapy (pulmonary vs non-pulmonary indication for therapy). We also divided the cohort according to the indication for changing to MMF therapy (perceived lack of efficacy of baseline therapy by the treating physician vs intolerance to baseline therapy). For both of these analyses, we found no statistically significant change in the change in the mean FVC and DLCO before and after MMF therapy between any of the two time points (Table 2).

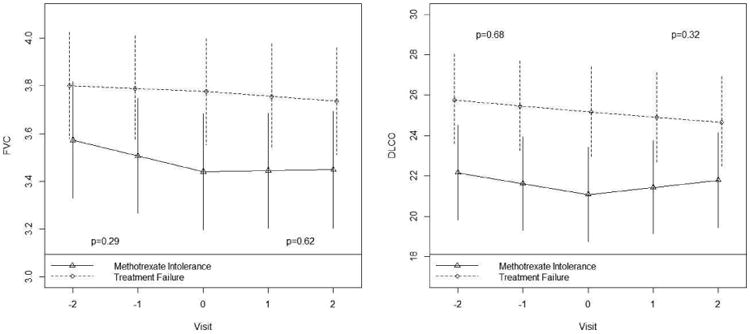

We then analyzed the data using a linear mixed models approach to account for the longitudinal nature of the study. The effects of MMF on changes in PFT were consistent for the absolute value of FEV1, FVC, DLCO and DLCO/VA, where baseline therapy intolerant subjects showed a trend towards improvement in PFT measurements after starting MMF (Figure 1,Table 1S). In contrast, the baseline treatment failure patients continued to show a decline in PFT measurements even after starting MMF (Figure 1,Table 1S).

Figure 1.

FVC and DLCO by group, spline at visit=0. Plotted values are estimates obtained from linear mixed models. Results apply to no prior smoking Caucasian male subjects of average age 54 years with active or progressive pulmonary sarcoidosis as the indication for IS therapy.

MMF is effective as a steroid sparing agent

We had available data from 32 patients regarding corticosteroid (CS) dosing. 11/32 (34%) patients were not on CS at the time MMF was started and 21 were on at least 5mg or higher (mean dose 14.2±12.4; range 5-60mg). After 6 months and 12 months of MMF therapy, the mean CS dose was 8.6 (±9.6) mg and 8.9 (±8.1) mg with a statistically significant decline in dose noted between the MMF start and 6 month follow up (p=0.004). Of note, 16/21 (76.2%) were on a prednisone dose of 5mg per day or higher at MMF start and 6/16 (37.5%) and 4/16 (25%) were on a prednisone of 5mg per day or higher at 6 and 12 months respectively. In addition, 5/21 (23.8%) and 8/21 (38.1%) subjects were able to discontinue prednisone after 6 and 12 months of therapy with MMF. This suggests that treating physicians are likely to successfully taper CS doses in patients with sarcoidosis who have been treated with MMF.

MMF is tolerated by the majority

Of all of the subjects treated with MMF, 6/76 (8%) could not tolerate MMF and stopped the drug within 1-2 months of starting it. Two patients complained of headaches, one of fatigue, one developed pneumonia and refused to continue MMF, and the reason for stopping MMF for 2 patients was not specified in their medical records. For patients who remained on therapy with MMF (n=37), four developed upper respiratory tract infections, two had urinary tract infections, one developed leukopenia, one thrombocytopenia, one cold sores, one skin sores and one gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, loose stools and diarrhea) yielding a total side effect rate of 16/76 (21.1%).

Effect of MMF on extra-pulmonary sarcoidosis

A number of our patients had non-pulmonary involvement in addition to pulmonary involvement,, as follows: 10/37 patients had cardiac involvement, 5/37 hypercalcuria, 4/37 hepatic, 3/37 ophthalmic and 2/37 cutaneous. Unfortunately, 3/10 of the cardiac sarcoidosis patients had inadequate clinical data to assess impact of MMF on cardiac sarcoidosis, while 6/7 of the remaining cardiac sarcoidosis subjects with available clinical data had a cardiac 18-fluorodeoxy-glucose positron emission test (cFDG-PET) prior to initiation of MMF. All 6 of these patients showed either a patchy or patchy on diffuse pattern of uptake in the myocardium. At 6 months, all had repeat cFDG-PET and demonstrated improvement or resolution of their myocardial hypermetabolic activity. Furthermore, 7/10 cardiac patients had echocardiograms prior to initiation of MMF, with 4/7 demonstrating normal left ventricular (LV) function that was unchanged on follow up testing. Two had moderate reduction in LV function (ejection fraction 35%) and one demonstrated slight improvement in LV ejection fraction from 34% to 40-45% and the other showed no change, while the last patient had a slightly reduced LV function (EF 45-50%) that normalized after 6 months of therapy. Because of the small numbers of other organ involvement, we were unable to assess the response in treatment with MMF.

Discussion

There are currently no Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved steroid sparing agents for the management of sarcoidosis. Corticosteroids have been considered first line therapy for active sarcoidosis, but are fraught with side effects5. While methotrexate is the most commonly use steroid sparing agent used in sarcoidosis, other therapies including leflunomide, azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) used as second line therapies for sarcoidosis7 have not been studied in randomized controlled trials and have only been evaluated in a few clinical studies except for one small study evaluating methotrexate as a steroid sparing agent in acute sarcoidosis17. We retrospectively investigated the efficacy of MMF in sarcoidosis, focusing on the use of MMF to treat pulmonary involvement. Our findings suggest that MMF may not offer an additional advantage in pulmonary sarcoidosis patients who have failed other steroid-sparing agents (with or without corticosteroid therapy). However, in subjects who are intolerant to other IS, MMF may result in some improvement in lung function. In addition, we found that MMF may be useful in enabling a reduction in prednisone dose. For the majority of treated sarcoidosis patients, MMF was well tolerated. Thus, MMF appears to have potential as a second line agent for some pulmonary sarcoidosis subjects. However, its use as the initial steroid-sparing agent in pulmonary sarcoidosis as a second line agent will require additional investigation.

Methotrexate remains the preferred choice as a steroid sparing agent amongst sarcoidosis experts7 but due to intolerance or lack of efficacy of methotrexate by some patients, investigators have looked at the role of other steroid sparing agents in sarcoidosis9-12,18. Lower et al reported a 10-15% improvement in FVC after 6 months of therapy with methotrexate in 12% of their cohort whereas in our cohort 9% showed at least a 10% improvement in their FVC after 6 months19. Sahoo et al investigated the potential role of leflunomide in pulmonary sarcoidosis9 and showed a statistically significant (190ml) absolute change in FVC from 6 months prior to initiating leflunomide to 6 month post leflunomide therapy9. Vorselaars et al also reported a statistically significant (97ml) absolute change in vital capacity between one year before and after therapy with methotrexate or azathioprine11. Our findings with MMF in the group intolerant to their current IS therapy showed a 120ml absolute improvement in FVC from 6 months prior to MMF to 6 months post MMF therapy and a 140ml absolute improvement in FVC from 12 months prior to MMF to 12 months post MMF therapy. However, we did not show a statistically significant change, possibly due to lack of power with small numbers. In a recent report on the use of MMF in 10 patients with chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis, Brill et al. demonstrated the ability of MMF to maintain lung function while reducing the dose of corticosteroids 12. However, in this study MMF was not used as a third line agent. This study and ours support the potential role of MMF as a steroid-sparing agent in sarcoidosis while maintaining or possibly improving lung function.

Our study also demonstrates the potential role of MMF as a steroid-reducing agent in sarcoidosis. 76.2% of our cohort was on prednisone at a dose of 5mg or higher at the time MMF was initiated and only 37.5% and 25% were on 5mg a day or higher at 6 and 12 months respectively. Vorselaars et al showed a mean decrease of daily prednisone dose of 6.32mg over 1 year11 with methotrexate or azathioprine therapy, while our cohort demonstrated a similar 5.9mg decrease in prednisone dose over one year. Sahoo et al reported that 31/41 (31.7%) of their cohort was able to wean off prednisone entirely after 6 months of therapy9 while in our cohort 23.8% and 38.1% of patients were able to wean off CS after 6 and 12 months of therapy respectively. In addition, MMF overall was well tolerated. Specifically, we found that the overall side effect rate of MMF in our entire cohort of 76 subjects was 21.1%. This rate is lower than that reported for azathioprine (34.6%)11 and leflunomide (34%)9 but similar to that reported for methotrexate (18.1%)11.

A retrospective study such as this is subject to several limitations including the lack of a systematic method for collecting the data, lack of standardization of indications for therapy, dosing regimens and management of concomitant therapies and a control or placebo group. We excluded patients who were started on corticosteroids or had their corticosteroid dose increased at the time of initiating MMF to avoid attributing any potential improvement from corticosteroid therapy to the use of MMF. Our cohort had two main indications for initiation of MMF: lack of perceived benefit by the treating physician or development of side effects on the current IS regimen. We analyzed both subgroups separately and found no statistically significant differences in FVC or DLCO in either subgroup. However, the methotrexate intolerant group tended to show a positive increase in FVC and DLCO at the 12 month follow-up, whereas the treatment failure cohort tended to show a persistent decline in FVC and DLCO at 12 months after initiation of MMF. The relatively small cohort size probably limited our power to detect a true difference in the sub-group analyses. These limitations may explain why we failed to find an effect of MMF in sarcoidosis, in contrast to the CTD-ILDs or it may be that MMF is not as an effective treatment once individuals with sarcoidosis have failed other IS.

In summary, our study does not show a significant benefit from MMF in patients already failing another second line agent but a trend towards improvement in DLCO in those intolerant to methotrexate. This may suggest a potential role of MMF in a selected group of patients but these findings will need to be confirmed and validated in a prospective study. Our study does suggest that MMF is effective as a steroid-sparing agent in sarcoidosis, as our subjects on MMF were able to reduce or wean off corticosteroids. Finally, our study did not address whether MMF is useful as a first-line steroid sparing agent in the management of pulmonary sarcoidosis; this will need to be addressed by larger randomized controlled clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Table 1S. Linear Mixed Model Slopes Estimates for Change in PFT Measurements for Pre-MMF versus Post-MMF for Baseline Therapy Intolerant versus Baseline Treatment Failure Group.

The role of mycophenolate mofetil in sarcoidosis is investigated in this manuscript.

Sarcoidosis patients already tolerating but not responding to methotrexate are unlikely to benefit from changing over to mycophenolate.

Mycophenolate is effective as a steroid sparing agent in sarcoidosis.

The side effect profile of mycophenolate is comparable to other steroid-sparing agents such as methotrexate, leflunomide and azathioprine.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the following grants:

NIH grant 1U01HL112695-01. Genomic Research in AAT-Deficiency and Sarcoidosis Study (GRADS) awarded to Lisa A. Maier.

Abbreviations

- MMF

Mycophenolate Mofetil

- NJH

National Jewish Health

- ATS

American Thoracic Society

- ERS

European Respiratory Society

- IS

Immunosuppressive therapy

- PFT

Pulmonary function test

- FEV1

Forced expiratory volume in the first second

- FVC

Forced vital capacity

- FEV1/FVC

Ratio of forced expiratory volume in the first second to forced vital capacity

- TLC

Total lung capacity

- DLCO

Diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide

- DLCO/VA

Diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide adjusted for alveolar volume

- LMM

Linear mixed models

- CS

Corticosteroids

Footnotes

We wish to confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors and that there are no other persons who satisfied the criteria for authorship but are not listed. We further confirm that the order of authors listed in the manuscript has been approved by all of us.

We confirm that we have given due consideration to the protection of intellectual property associated with this work and that there are no impediments to publication, including the timing of publication, with respect to intellectual property. In so doing we confirm that we have followed the regulations of our institutions concerning intellectual property.

We understand that the Corresponding Author is the sole contact for the Editorial process (including Editorial Manager and direct communications with the office). He is responsible for communicating with the other authors about progress, submissions of revisions and final approval of proofs. We confirm that we have provided a current, correct email address which is accessible by the Corresponding Author and which has been configured to accept email from hamzehn@njhealth.org

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Statement on Sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:736–55. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.2.ats4-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paramothayan S, Lasserson TJ, Walters EH. Immunosuppressive and cytotoxic therapy for pulmonary sarcoidosis. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) 2006;3:CD003536. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003536.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paramothayan SP, MRCP, Jones PaulW., PhD, FRCP Corticosteroid Therapy in Pulmonary Sarcoidosis : A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2002;287:1301–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.10.1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paramothayan NS, Lasserson TJ, Jones PW. Corticosteroids for pulmonary sarcoidosis. Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) 2005:CD001114. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001114.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keenan CR, Salem S, Fietz ER, Gualano RC, Stewart AG. Glucocorticoid-resistant asthma and novel anti-inflammatory drugs. Drug Discovery Today. 2012;17:1031–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baughman RP, Nunes H, Sweiss NJ, Lower EE. Established and experimental medical therapy of pulmonary sarcoidosis. European Respiratory Journal. 2013;41:1424–38. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00060612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schutt AC, Bullington WM, Judson MA. Pharmacotherapy for pulmonary sarcoidosis: a Delphi consensus study. Respir Med. 2010;104:717–23. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baughman RP, Lower EE. A clinical approach to the use of methotrexate for sarcoidosis. Thorax. 1999;54:742–6. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.8.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sahoo DH, Bandyopadhyay D, Xu M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of leflunomide for pulmonary and extrapulmonary sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:1145–50. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00195010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baughman RP, Lower EE. Leflunomide for chronic sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2004;21:43–8. doi: 10.1007/s11083-004-5178-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vorselaars AD, Wuyts WA, Vorselaars VM, et al. Methotrexate vs azathioprine in second-line therapy of sarcoidosis. Chest. 2013;144:805–12. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brill AK, Ott SR, Geiser T. Effect and safety of mycophenolate mofetil in chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis: a retrospective study. Respiration. 2013;86:376–83. doi: 10.1159/000345596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer A, Brown KK, Du Bois RM, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil improves lung function in connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. J Rheumatol. 2013;40:640–6. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.121043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swigris JJ, Olson AL, Fischer A, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil is safe, well tolerated, and preserves lung function in patients with connective tissue disease-related interstitial lung disease. Chest. 2006;130:30–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller MR, Crapo R, Hankinson J, et al. General considerations for lung function testing. European Respiratory Journal. 2005;26:153–61. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baughman RP, Drent M, Culver DA, et al. Endpoints for clinical trials of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2012;29:90–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baughman RP, Winget DB, Lower EE. Methotrexate is steroid sparing in acute sarcoidosis: results of a double blind, randomized trial. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2000;17:60–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baughman RP, Lower EE. Infliximab for refractory sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2001;18:70–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lower EE, Baughman RP. Prolonged use of methotrexate for sarcoidosis. Archives of internal medicine. 1995;155:846–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table 1S. Linear Mixed Model Slopes Estimates for Change in PFT Measurements for Pre-MMF versus Post-MMF for Baseline Therapy Intolerant versus Baseline Treatment Failure Group.