Abstract

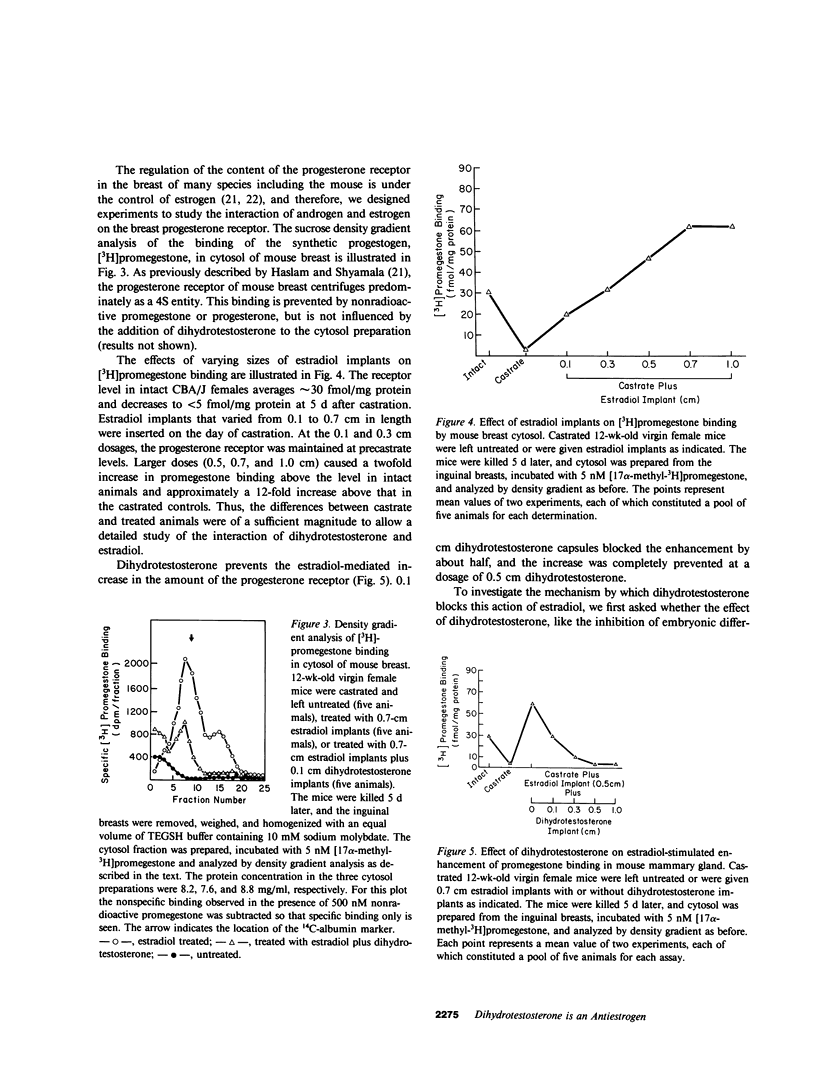

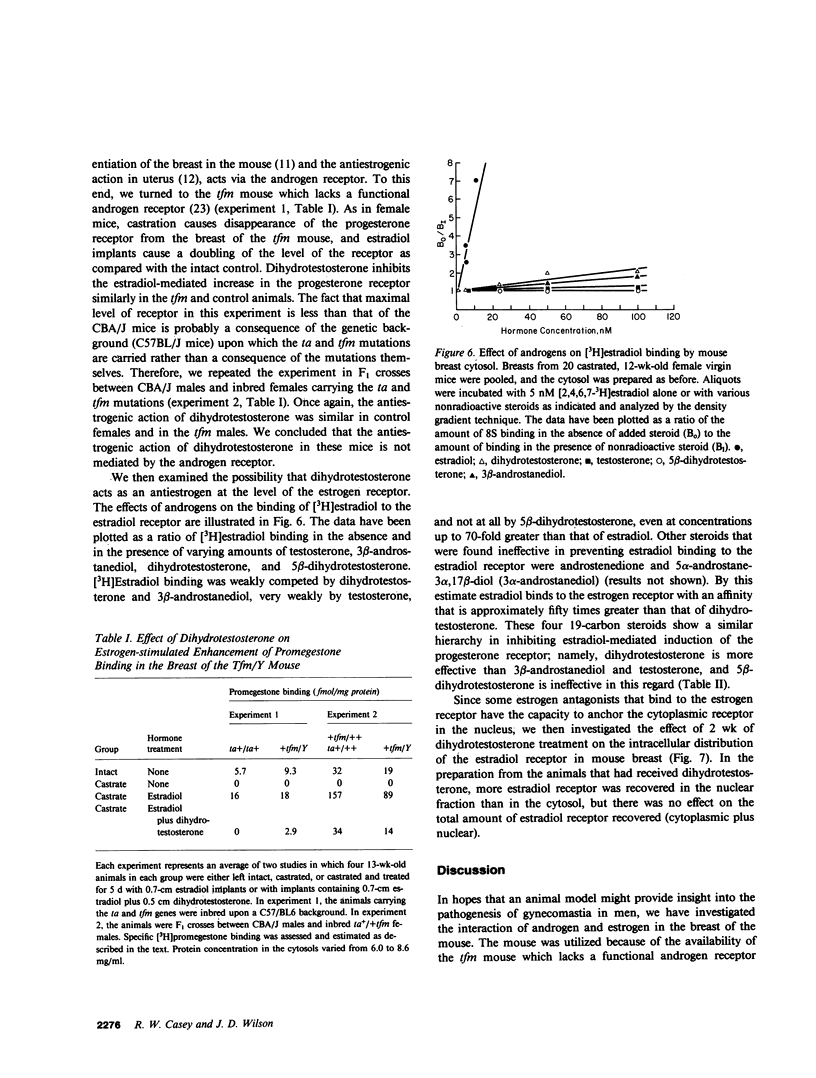

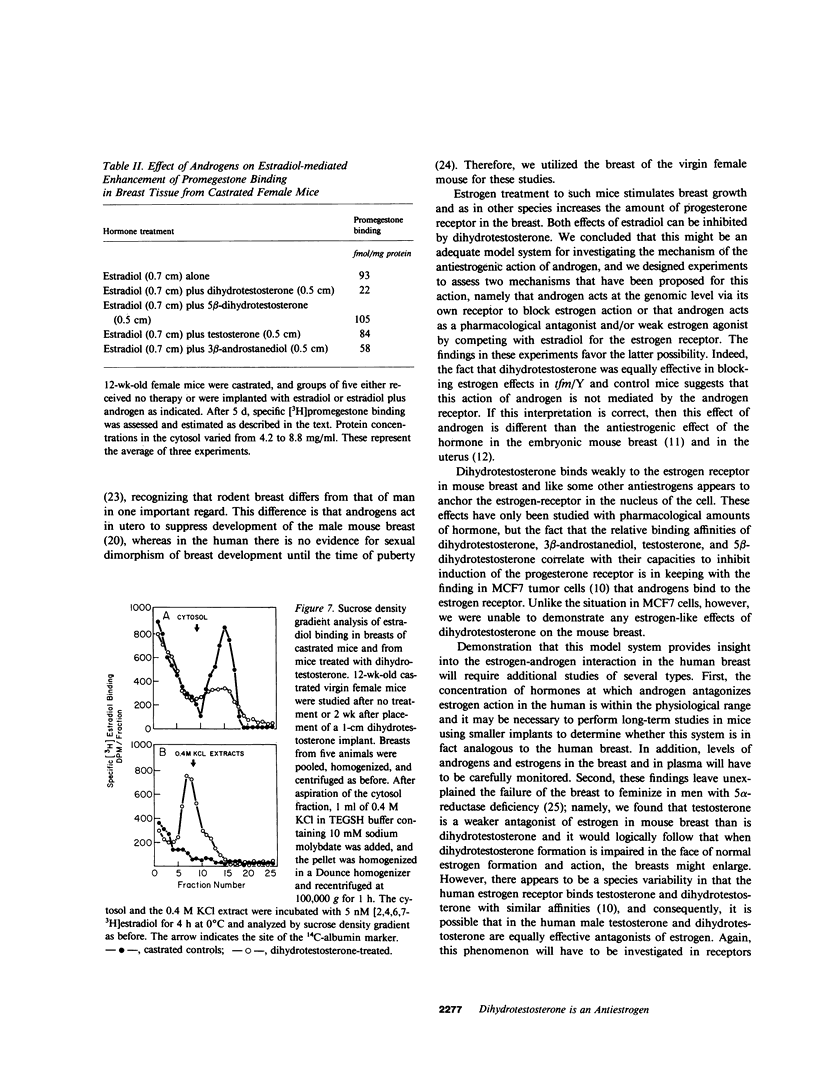

Feminization in men occurs when the effective ratio of androgen to estrogen is lowered. Since sufficient estrogen is produced in normal men to induce breast enlargement in the absence of adequate amounts of circulating androgens, it has been generally assumed that androgens exert an antiestrogenic action to prevent feminization in normal men. We examined the mechanisms of this effect of androgens in the mouse breast. Administration of estradiol via silastic implants to castrated virgin CBA/J female mice results in a doubling in dry weight and DNA content of the breast. The effect of estradiol can be inhibited by implantation of 17 beta-hydroxy-5 alpha-androstan-3-one (dihydrotestosterone), whereas dihydrotestosterone alone had no effect on breast growth. Estradiol administration also enhances the level of progesterone receptor in mouse breast. Within 4 d of castration, the progesterone receptor virtually disappears and estradiol treatment causes a twofold increase above the level in intact animals. Dihydrotestosterone does not compete for binding to the progesterone receptor, but it does inhibit estrogen-mediated increases of progesterone receptor content of breast tissue cytosol from both control mice and mice with X-linked testicular feminization (tfm)/Y. Since tfm/Y mice lack a functional androgen receptor, we conclude that this antiestrogenic action of androgen is not mediated by the androgen receptor. Dihydrotestosterone competes with estradiol for binding to the cytosolic estrogen receptor of mouse breast, whereas 17 beta-hydroxy-5 beta-androstan-3-one (5 beta-dihydrotestosterone) neither competes for binding nor inhibits estradiol-mediated induction of the progesterone receptor. Dihydrotestosterone also promotes the translocation of estrogen receptor from cytoplasm to nucleus; the ratio of cytoplasmic-to-nuclear receptor changes from 3:1 in the castrate to 1:2 in dihydrotestosterone-treated mice. Thus, the antiestrogenic effect of androgen in mouse breast may be the result of effects of dihydrotestosterone on the estrogen receptor. If so, dihydrotestosterone performs one of its major actions independent of the androgen receptor.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aiman J., Brenner P. F., MacDonald P. C. Androgen and estrogen production in elderly men with gynecomastia and testicular atrophy after mumps orchitis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1980 Feb;50(2):380–386. doi: 10.1210/jcem-50-2-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURTON K. A study of the conditions and mechanism of the diphenylamine reaction for the colorimetric estimation of deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochem J. 1956 Feb;62(2):315–323. doi: 10.1042/bj0620315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edman C. D., Winters A. J., Porter J. C., Wilson J., MacDonald P. C. Embryonic testicular regression. A clinical spectrum of XY agonadal individuals. Obstet Gynecol. 1977 Feb;49(2):208–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrilove J. L., Freiberg E. K., Leiter E., Nicolis G. L. Feminizing and non-feminizing Sertoli cell tumors. J Urol. 1980 Dec;124(6):757–767. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)55652-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrilove J. L., Nicolis G. L., Mitty H. A., Sohval A. R. Feminizing interstitial cell tumor of the testis: personal observations and a review of the literature. Cancer. 1975 Apr;35(4):1184–1202. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197504)35:4<1184::aid-cncr2820350425>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrilove J. L. Some recent advances in virilizing and feminizing syndromes and hirsutism. Mt Sinai J Med. 1974 Sep-Oct;41(5):636–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein J. L., Wilson J. D. Studies on the pathogenesis of the pseudohermaphroditism in the mouse with testicular feminization. J Clin Invest. 1972 Jul;51(7):1647–1658. doi: 10.1172/JCI106966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon G. G., Olivo J., Rafil F., Southren A. L. Conversion of androgens to estrogens in cirrhosis of the liver. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1975 Jun;40(6):1018–1026. doi: 10.1210/jcem-40-6-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene W. A., Foote R. H. Release rate of testosterone and estrogens from polydimethylsiloxane implants for extended periods in vivo compared with loss in vitro. Int J Fertil. 1978;23(2):128–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam S. Z., Shyamala G. Relative distribution of estrogen and progesterone receptors among the epithelial, adipose, and connective tissue components of the normal mammary gland. Endocrinology. 1981 Mar;108(3):825–830. doi: 10.1210/endo-108-3-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz K. B., McGuire W. L. Progesterone and progesterone receptors in experimental breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1977 Jun;37(6):1733–1738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratochwil K. Development and loss of androgen responsiveness in the embryonic rudiment of the mouse mammary gland. Dev Biol. 1977 Dec;61(2):358–365. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratochwil K., Schwartz P. Tissue interaction in androgen response of embryonic mammary rudiment of mouse: identification of target tissue for testosterone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976 Nov;73(11):4041–4044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.11.4041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O. H., ROSEBROUGH N. J., FARR A. L., RANDALL R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARTIN R. G., AMES B. N. A method for determining the sedimentation behavior of enzymes: application to protein mixtures. J Biol Chem. 1961 May;236:1372–1379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald P. C., Madden J. D., Brenner P. F., Wilson J. D., Siiteri P. K. Origin of estrogen in normal men and in women with testicular feminization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1979 Dec;49(6):905–916. doi: 10.1210/jcem-49-6-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montelaro R. C., Rueckert R. R. Radiolabeling of proteins and viruses in vitro by acetylation with radioactive acetic anhydride. J Biol Chem. 1975 Feb 25;250(4):1413–1421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PFALTZ C. R. Das embryonale und postnatale Verhalten der männliche Brustdrüse beim Menschen; das Mammarorgan im Kindes-, Jüglings-, Mannes- und Greisenalter. Acta Anat (Basel) 1949;8(4):293–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochefort H., Garcia M. The estrogenic and antiestrogenic activities of androgens in female target tissues. Pharmacol Ther. 1983;23(2):193–216. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(83)90013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. D., Aiman J., MacDonald P. C. The pathogenesis of gynecomastia. Adv Intern Med. 1980;25:1–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zava D. T., McGuire W. L. Androgen action through estrogen receptor in a human breast cancer cell line. Endocrinology. 1978 Aug;103(2):624–631. doi: 10.1210/endo-103-2-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]