Abstract

Background and Objectives

Dysregulated affect is a hallmark feature of acute episodes of bipolar disorder (BD) and persists during inter-episode periods. Its contribution to course of illness is not yet known. The present report examines the prospective influence of inter-episode affect dysregulation on symptoms and functional impairment in BD.

Methods

Twenty-seven participants diagnosed with inter-episode bipolar I disorder completed daily measures of negative and positive affect for 49 days (± 8 days) while they remained inter-episode. One month following this daily assessment period, symptom severity interviews and a measure of functional impairment were administered by telephone.

Results

More intense negative affect and positive affect during the inter-episode period were associated with higher depressive, but not manic, symptoms at the one-month follow-up assessment. More intense and unstable negative affect, and more unstable positive affect, during the inter-episode period were associated with greater impairment in home and work functioning at the follow-up assessment. All associations remained significant after controlling for concurrent symptom levels.

Limitations

The findings need to be confirmed in larger samples with longer follow-up periods. A more comprehensive assessment of functional impairment is also warranted.

Conclusions

The findings suggest that a persistent affective dysregulation between episodes of BD may be an important predictor of depression and functional impairment. Monitoring daily affect during inter-episode periods could allow for a more timely application of interventions that aim to prevent or reduce depressive symptoms and improve functioning for individuals with BD.

1 Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a seriously disabling and life threatening disorder with a significant public health burden. BD is associated with high rates of recurrence, persistent functional impairment, and low quality of life (Altshuler et al., 2006; Gitlin, Mintz, Sokolski, Hammen, & Altshuler, 2011; Joffe, MacQueen, Marriott, & Young, 2004; Judd et al., 2008; Vieta, Sanchez-Moreno, Lahuerta, & Zaragoza, 2008). Understanding the mechanisms that underlie sustained inter-episode impairment in BD is important to developing more effective interventions that prolong symptom-free periods and improve quality of life.

Acute episodes in BD are defined by affective dysregulation, with abnormally and persistently elevated or irritable mood serving as core criteria for episodes of (hypo)mania, and a distinct period of depressed or irritable mood, or anhedonia, serving as core criteria for depression (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Affective dysregulation has also been shown to persist between acute episodes in BD. Studies using ecological momentary assessment methods document heightened and more variable negative affect among remitted or subsyndromal bipolar samples relative to controls (Gershon et al., 2012; Havermans, Nicolson, Berkhof, & deVries, 2010; Hofmann & Meyer, 2006; Knowles et al., 2007; Lovejoy & Steuerwald, 1995). Increased variability in positive affect has also been documented among remitted or subsyndromal bipolar samples relative to controls (Hofmann & Meyer, 2006; Knowles et al., 2007; Lovejoy & Steuerwald, 1995), but support for group differences in intensity of positive affect is less consistent (Knowles et al., 2007; Lovejoy & Steuerwald, 1995).

The persistence of affective dysregulation during inter-episode periods suggests that it may be an illness maintaining mechanism and a contributor to the high rates of functional impairment in BD (Soreca, Frank, & Kupfer, 2009). It may be the case that dysregulated negative affect is particularly problematic. Long-term naturalistic studies of the presentation of BD have shown that depression predominates the course of the disorder (Judd et al., 2002; Kupka et al., 2007). For example, in a longitudinal study that collected weekly mood ratings in bipolar participants over the course of two years, depressive symptoms were reported 47.7% of the time, manic symptoms 7% of the time, mixed symptoms 8.8% of the time, and euthymia 36.5% of the time (Bopp et al., 2010). Thus, depressive symptoms were present for nearly half the time in these patients' lives, whereas manic symptoms were relatively infrequent. Studies also indicate that depressive symptoms may be particularly impairing. For instance, subsyndromal depressive symptoms have been found to be more strongly related to functional impairments than subsyndromal manic symptoms (e.g., Fagiolini et al., 2005).

There are several potential pathways by which affective dysregulation may contribute to symptoms and impairment in BD. For instance, individuals with BD may utilize maladaptive coping styles, such as rumination, in response to negative affect (Johnson, McKenzie, & McMurrich, 2008). Rumination may, in turn, act to perpetuate negative affect, thereby increasing vulnerability to depression (Alloy et al., 2009; Pavlickova et al., 2013) and interfering with occupational and social functioning (Kuehner & Huffziger, 2012; Lam, Schuck, Smith, Farmer, & Checkley, 2003). Maladaptive coping responses to dysregulated positive affect, including increased risk-taking behavior, may similarly increase vulnerability to mania symptoms and impairment (Thomas & Bentall, 2002; Pavlickova, et al., 2013). The possibility that affective dysregulation contributes to a poorer course of illness in BD has been supported by findings that affective lability and intensity during the inter-episode period are associated with a more severe illness history, including earlier onset, greater comorbidity, and an increased number of past illness episodes (Henry et al., 2008). Accruing evidence from epidemiological and clinical studies has also highlighted the importance of affective dysregulation in understanding the phenomenology of bipolar depression, calling for a careful consideration of this feature in clinical evaluations of bipolar patients (Akiskal, 2005). Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge the influence of daily affect dysregulation, as experienced during inter-episode period, on future symptoms and functioning in BD has not yet been directly examined.

The goal of the present study is to use longitudinal data to examine the influence of inter-episode affect intensity and instability on symptoms and functional impairment in BD. Affective intensity and instability were measured using daily reports of positive and negative affect collected over a 7-week inter-episode period. We hypothesized that more intense and unstable affect during the inter-episode period of BD would predict more severe symptoms and greater functional impairment at a one-month follow-up assessment.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

This study uses a sub-sample from a larger study examining the relationship between sleep and affect in participants with inter-episode bipolar I disorder and healthy controls (Gershon et al., 2012). The current report focuses on twenty-seven inter-episode bipolar I participants who completed the 7-week daily assessment of affect and also completed a symptom and functioning follow-up assessment one month later. All participants met criteria for BD I and remained inter-episode throughout the 7-week daily assessment period. Inter-episode status was defined as: (a) the absence of a current mood episode based on DSM-IV TR criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000); and (b) no more than mild symptom severity scores on the Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Clinician Rated (IDS-C; score ≤ 23; Rush, Gullion, Basco, Jarrett, & Trivedi, 1996) and the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS; score ≤ 11; Young, Biggs, Ziegler, & Meyer, 1978). Participants were not excluded on the basis of psychiatric comorbidities.

2.2 Procedure

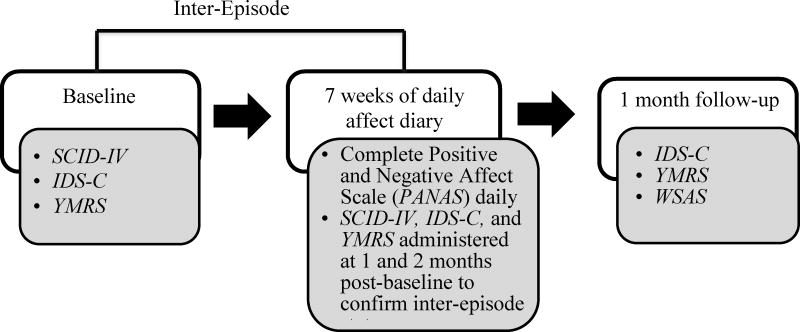

All procedures were approved by the University of California's Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects. As illustrated in Figure 1, at baseline participants provided informed consent and were interviewed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV (SCID; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002), the IDS-C, and the YMRS to ascertain psychiatric disorder history and confirm current inter-episode status. Eligible participants were given daily affect diaries and were asked to complete these each evening approximately 2 hours prior to bedtime. Participants were asked to leave a voicemail with their diary responses each evening in order to obtain a time-stamped record of completion.

Figure 1.

Flow chart demonstrating measures used to assess participants at each assessment point. SCID-IV = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV; IDS-C = Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Clinician Rating; YMRS = Young Mania Rating Scale; WSAS = Work and Social Adjustment Scale.

Participants returned to the lab one month and two months following their baseline visit. During each of these visits, continued inter-episode status was confirmed using the SCID, the IDS-C, and the YMRS. Participants who met criteria for a current mood episode at either visit, and/or who exceeded symptom severity thresholds, were excluded from further evaluation, assessed for safety, and (with permission) re-contacted in two weeks for reassessment. Thus, in total we required that participants be inter-episode for three months (approximately 12 weeks) in order to be included in the study. There is evidence to suggest that roughly 40% of individuals with bipolar I disorder experience a mood episode within one year of a euthymic period (Perlis et al., 2006; Judd et al., 2008). Additionally, a recent naturalistic longitudinal study of individuals with bipolar I and II disorder who were enrolled in the study during a hospitalization found that 68% had a relapse during the 4-year follow-up period. For those participants who relapsed, the average time to relapse was 208 days (or approximately 29 weeks) (Simhandl, Konig, & Amann, 2014). Given these previous findings, our inclusion of participants who were in the inter-episode period for 3 months is representative of the natural course of bipolar disorder. The study duration also allowed us to prospectively gather data on symptoms and impairment present during the inter-episode period.

At 3 months following the baseline assessment, the IDS-C, YMRS, and a questionnaire measuring functional impairment were administered to participants by telephone.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 Psychiatric disorders

The SCID (First et al., 2002) was used to assess Axis I psychiatric disorders. Diagnostic inter-rater reliability was established for a randomly selected sample of audio taped interviews (n = 17). Primary diagnoses (bipolar) matched those made by the original interviewer in all cases (k = 1.00).

2.3.2 Symptom severity

The IDS-C (Rush et al., 1996) and the YMRS (Young et al., 1978) were used to assess current mood symptoms. The IDS-C is a 30-item interview measure of depression severity. Scores range from 0 to 84, with higher scores indicating greater severity. Scores less than 24 indicate asymptomatic to mild symptom severity (Rush et al., 1996). The YMRS is an 11-item interview measure of mania severity. Scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity. Scores less than 12 indicate asymptomatic to mild symptom severity (e.g., Suppes et al., 2005). Intra-class correlations (Shrout & Fleiss, 1979) between the original interviewer and an independent rater for a randomly chosen subset of study participants (n = 22) were strong for the IDS-C (r = .85) and YMRS (r = .83).

2.3.3 Daily affect

Positive and negative affect levels were measured using the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Carey, 1988). The PANAS lists ten negative adjectives (distressed, upset, hostile, irritable, scared, afraid, ashamed, guilty, nervous, jittery) and ten positive adjectives (attentive, interested, alert, excited, enthusiastic, inspired, proud, determined, strong, active). Subjects were asked to rate each of these adjectives on a 5-point scale (1 = very slightly or not at all and 5 = extremely) each evening, reflecting on their affective experience over the course of the day.

2.3.4 Functional impairment

The Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS; Mundt, Marks, Shear, & Greist, 2002) is a 5-item measure with good internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and sensitivity to disorder severity (Mundt et al., 2002). Individual items measure impairment in work, home, and social functioning. Items are rated on a 0 to 8 metric, with higher scores representing more functional impairment.

2.4 Data Analysis

Mean levels and instability of negative and positive affect was calculated across all study days. Instability was calculated by the mean squared successive differences (MSSD; Jahng, Wood, & Trull, 2008) based on recommendations for its use in ecological momentary assessment studies of affect (Ebner-Priemer, Eid, Kleindienst, Stabenow, & Trull, 2009).

To accurately estimate the potential influence of affect on illness course, we controlled for concurrent symptom levels in our analysis (Kraemer, Stice, Kazdin, Offord, & Kupfer, 2001). Partial correlations controlling for concurrent symptom severity were used to examine whether average negative affect intensity, negative affect instability (MSSD), positive affect intensity, or positive affect instability (MSSD) predicted changes in depressive (IDS-C) or manic (YMRS) symptoms. Partial correlations controlling for concurrent symptoms were also used to examine whether affective variables predicted functional impairment (WSAS) in work, home, or social functioning at a one-month follow-up assessment.

3 Results

The sample's descriptive characteristics including demographic, clinical, and affective variables are depicted in Table 1. Eleven of 27 bipolar participants (40.7%) had at least one comorbid Axis I disorder, including specific phobia (n = 6), generalized anxiety disorder (n = 4), social phobia (n = 3), panic disorder (n = 2), binge eating disorder (n = 1), and posttraumatic stress disorder (n = 1). All but two participants (n = 25) were being treated with pharmacological agents; including antidepressants (n = 13), lamotrigine (n = 11), lithium (n = 5), hypnotics (n = 5), and valproic acid (n = 3). Eighteen of 27 (66.7%) bipolar participants were being treated with more than one medication.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the sample's demographic, clinical, and affective characteristics (N=27).

| Demographic characteristics | |

| % Female | 66.7% |

| % Caucasian | 63.0% |

| Age, Mean (SD) | 35.0 (10.4) |

| % Employed | 66.6% |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Onset Age in years, Mean (SD) | 19.4 (9.5) |

| Lifetime manic episodes, Mean (SD) | 8.0 (11.8) |

| Lifetime depressive episodes, Mean (SD) | 10.9 (14.6) |

| Lifetime psychiatric hospitalizations, Mean (SD) | 1.9 (3.3) |

| IDS-C | |

| Inter-episode period, Mean (SD) | 10.9 (4.2) |

| One month follow-up, Mean (SD) | 10.5 (6.3) |

| YMRS | |

| Inter-episode period, Mean (SD) | 4.1 (4.0) |

| One month follow-up, Mean (SD) | 3.9 (4.4) |

| Affective functioning | |

| Negative affect intensity, inter-episode period, Mean (SD) | 19.7 (3.9) |

| Positive affect intensity, inter-episode period, Mean (SD) | 24.3 (8.2) |

| Negative affect instability, inter-episode period, MSSD (SE) | 30.6 (11.6) |

| Positive affect instability, inter-episode period, MSSD (SE) | 55.7 (9.0) |

Note: IDS-C = Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Clinician Rating; YMRS = Young Mania Rating Scale

As depicted in Table 2, after controlling for concurrent depressive and hypomanic/manic symptoms, more intense negative and positive affect during the inter-episode period were both significantly correlated with higher depressive, but not manic, symptoms at the one-month follow-up assessment. After controlling for concurrent depressive and hypomanic/manic symptoms, more intense or unstable negative affect, and more unstable positive affect, were significantly correlated with greater impairment in participants' work and home functioning at the one-month follow-up assessment.

Table 2. Partial correlations of affective intensity and instability with follow-up symptoms and functional impairment, controlling for concurrent symptoms (N=27).

| IDS-C total score |

YMRS total score |

Work functioning |

Home functioning |

Social functioning |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Affect | |||||

| Intensity | .526** | -.040 | .447* | .270 | .099 |

| Instability | .326 | .047 | .451* | .485* | .089 |

| Positive Affect | |||||

| Intensity | .408* | .150 | .123 | .131 | .112 |

| Instability | .167 | .219 | .491* | .486* | .157 |

Note:

p<.05,

p<.01.

IDS-C = Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Clinician Rating; YMRS = Young Mania Rating Scale; WSAS = Work and Social Adjustment Scale

4 Discussion

The focus of this longitudinal study was to investigate the prospective influence of inter-episode affective dysregulation on symptoms and functional impairment in BD. After controlling for concurrent symptom levels, more intense negative or positive affect during the inter-episode period predicted higher depressive, but not manic, symptoms. More intense negative affect, and more unstable negative or positive affect, predicted greater impairment in participants' home and work functioning. These results are consistent with a growing literature indicating that affective intensity and instability are important features of the inter-episode period in BD (e.g., Henry et al., 2008) and extend this literature by demonstrating the prognostic value of monitoring affective dimensions during inter-episode periods. Notably, we found that affective intensity and instability appear to be prognostic indicators of symptoms and impairment beyond the predictive value of inter-episode symptoms. This result is consistent with the proposal that affective dyregulation represents an illness maintaining mechanism in BD, and is also consistent with the idea that individuals with BD may respond to affective dyregulation with maladaptive coping styles that increase vulnerability to depression (Alloy et al., 2009; Pavlickova et al., 2013).

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the current results. First, the study is based on a small sample followed for a brief period of time, which may have limited our ability to detect changes in manic symptoms or functional impairment in the social domain. Given that depression tends to predominate the course of this illness (Bopp, Miklowitz, Goodwin, Stevens, Rendell, Geddes, 2010) it is possible that the relatively brief (3 month) time period of the study did not allow us to capture sufficiently high levels of mania symptoms such that effects of dysregulated affect could be observed. In addition, power to detect effects on mania outcomes was limited by our small sample size. Second, the study's focus on the inter-episode period of BD, by definition, restricted the sample's symptom levels, thus precluding examination of dysregulated affect on acute episode onsets. It will be important for the present results to be replicated with a larger sample and with a longer follow-up period.

Third, although the Work and Social Adjustment Scale is a widely used and reliable scale (Mundt et al., 2002), functional impairment in each domain is assessed by one item only. A more detailed assessment of the precise difficulties experienced by patients within each of the domains of functioning would be useful. Fourth, though the PANAS was completed successfully by our sample over the course of 7 weeks, it is a cumbersome measure for use over the long term. Briefer measures (e.g., the short-form of the PANAS (Thompson, 2007) or another subset of PANAS items) may be more suitable for long-term data collection. Investigators are often faced with a need for both brevity and breadth in clinical assessment measures. The number of items and frequency of data collection necessary to accurately assess constructs like affect intensity and stability must be weighed against the burden on patients, especially when data are collected over the period of weeks or months. Fifth, we did not apply a correction for multiple statistical tests due to the relatively small sample size. Applying a conservative statistical control such as the Bonferonni correction would substantially reduce statistical power, while also increasing the possibility of Type II error. In this initial study we were more concerned about possible Type II error, which would hinder our ability to detect potentially important effects in a relatively unique dataset (Nakagawa, 2004). Finally, though we used a carefully developed coding system for measuring medication adequacy, our study did not assess for current psychotherapy treatment. Investigation of the relation between psychotherapy and intensity and/or instability of affect is an important direction for future research.

Despite these limitations, the current findings highlight the importance of affective intensity and instability during inter-episode periods of BD and suggest that affective dysregulations may contribute to sustained symptoms and to the high rates of functional impairment associated with BD. Specifically, our findings show that greater intensity in negative or positive affect, occurring during inter-episode periods, may be an early sign of depressive symptoms. Instability in affect, either positive or negative, appears to be related to increased impairment in work and home functioning. Impairments in work functioning may be particularly important, as these have been shown to predict relapse in remitted bipolar patients, beyond inter-episode symptoms (Gitlin, Swendsen, Heller, & Hammen, 1995).

Our study provides evidence that detailed daily affect monitoring can be successfully implemented in a bipolar adult sample over a 7-week period, and that increased awareness and monitoring of both positive and negative affective states may aid in earlier detection of emerging depressive symptoms and difficulties in functioning. Empirically supported psychotherapeutic interventions for BD, including cognitive behavior therapy, interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, and family focused therapy for BD all integrate the use of a daily log to monitor for possible emerging symptoms during the inter-episode period (Miklowitz, 2006). These logs typically require the patient to rate their mood on a numerical scale ranging from extremely low to euphoric mood. Our findings suggest that it may be beneficial to incorporate more detailed monitoring of both positive and negative affect (e.g., by using the PANAS, or a subset of affect rating items) into the daily logs used in treatments of individuals with BD. Monitoring both positive and negative affect would likely create a more sensitive assessment of mood that would allow for earlier intervention intended to mitigate emerging depressive symptoms and functional impairment. Daily monitoring of affect could also provide an opportunity to review treatment progress with patients who are working on regulating affect (e.g., reducing affective intensity, stabilizing affect). Increasing awareness of daily affective fluctuations in both positive and negative affect may allow for more timely applications of interventions designed to stabilize emotions and reduce maladaptive coping responses such as rumination and increased risk-taking behaviors. Applying such interventions during the inter-episode period could, in turn, help prevent symptom increase and improve inter-episode functioning.

Highlights.

We examine the influence of inter-episode affect on symptoms in bipolar disorder.

Affect was measured daily for 7 weeks while participants remained inter-episode.

More intense inter-episode negative and positive affect predicts depression.

More unstable negative and positive affect predicts impaired functioning.

Daily affect monitoring may aid earlier detection of symptoms in bipolar disorder.

Acknowledgments

We thank Allison Harvey for providing the resources necessary for conducting this research and for valuable feedback on this manuscript. We thank Drs. Katherine Kaplan and Eleanor McGlinchey for their help in conducting this study.

Role of Funding Source: This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Postdoctoral Fellowship F32MH76339. Preparation of the manuscript was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment and by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Research Scientist Development Award K01MH100433 awarded to AG.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Neither of the authors has any potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akiskal HS. The dark side of bipolarity: detecting bipolar depression in its pleomorphic expressions. J Affect Disord. 2005;84:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Flynn M, Liu RT, Grant DA, Jager-Hyman S, Whitehouse WG. Self-focused Cognitive Styles and Bipolar Spectrum Disorders: Concurrent and Prospective Associations. Int J Cogn Ther. 2009;2:354. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2009.2.4.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altshuler LL, Post RM, Black DO, Keck PE, Jr, Nolen WA, Frye MA, Suppes T, Grunze H, Kupka RW, Leverich GS, McElroy SL, Walden J, Mintz J. Subsyndromal depressive symptoms are associated with functional impairment in patients with bipolar disorder: results of a large, multisite study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1551–1560. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th, Text Revision. Washington DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bopp JM, Miklowitz DJ, Goodwin GM, Stevens W, Rendell JM, Geddes JR. The longitudinal course of bipolar disorder as revealed through weekly text messaging: a feasibility study. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:327–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00807.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner-Priemer UW, Eid M, Kleindienst N, Stabenow S, Trull TJ. Analytic strategies for understanding affective (in)stability and other dynamic processes in psychopathology. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118:195–202. doi: 10.1037/a0014868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagiolini A, Kupfer DJ, Masalehdan A, Scott JA, Houck PR, Frank E. Functional impairment in the remission phase of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:281–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. New York State: Psychiatric Institute, New York: Biometrics Research; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gershon A, Thompson WK, Eidelman P, McGlinchey EL, Kaplan KA, Harvey AG. Restless pillow, ruffled mind: sleep and affect coupling in interepisode bipolar disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2012;121:863–873. doi: 10.1037/a0028233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin MJ, Mintz J, Sokolski K, Hammen C, Altshuler LL. Subsyndromal depressive symptoms after symptomatic recovery from mania are associated with delayed functional recovery. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:692–697. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05291gre. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin MJ, Swendsen J, Heller TL, Hammen C. Relapse and impairment in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1635–1640. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.11.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havermans R, Nicolson NA, Berkhof J, deVries MW. Mood reactivity to daily events in patients with remitted bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2010;179:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry C, Van den Bulke D, Bellivier F, Roy I, Swendsen J, M'Bailara K, Siever LJ, Leboyer M. Affective lability and affect intensity as core dimensions of bipolar disorders during euthymic period. Psychiatry Res. 2008;159:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann BU, Meyer TD. Mood fluctuations in people putatively at risk for bipolar disorders. Br J Clin Psychol. 2006;45:105–110. doi: 10.1348/014466505X35317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahng S, Wood PK, Trull TJ. Analysis of affective instability in ecological momentary assessment: Indices using successive difference and group comparison via multilevel modeling. Psychol Methods. 2008;13:354–375. doi: 10.1037/a0014173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joffe RT, MacQueen GM, Marriott M, Young L. A prospective, longitudinal study of percentage of time spent ill in patients with bipolar I or bipolar II disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:62–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1399-5618.2003.00091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, McKenzie G, McMurrich S. Ruminative Responses to Negative and Positive Affect Among Students Diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder. Cognit Ther Res. 2008;32:702–713. doi: 10.1007/s10608-007-9158-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, Endicott J, Maser J, Solomon DA, Leon AC, Rice JA, Keller MB. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:530–537. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Akiskal HS, Coryell W, Leon AC, Maser JD, Solomon DA. Residual symptom recovery from major affective episodes in bipolar disorders and rapid episode relapse/recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:386–394. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.4.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles R, Tai S, Jones SH, Highfield J, Morriss R, Bentall RP. Stability of self-esteem in bipolar disorder: comparisons among remitted bipolar patients, remitted unipolar patients and healthy controls. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:490–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Stice E, Kazdin A, Offord D, Kupfer D. How do risk factors work together? Mediators, moderators, and independent, overlapping, and proxy risk factors. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:848–856. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehner C, Huffziger S. Response styles to depressed mood affect the long-term course of psychosocial functioning in depressed patients. J Affect Disord. 2012;136:627–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupka RW, Altshuler LL, Nolen WA, Suppes T, Luckenbaugh DA, Leverich GS, Frye MA, Keck PE, Jr, McElroy SL, Grunze H, Post RM. Three times more days depressed than manic or hypomanic in both bipolar I and bipolar II disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:531–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam D, Schuck N, Smith N, Farmer A, Checkley S. Response style, interpersonal difficulties and social functioning in major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2003;75:279–283. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Steuerwald BL. Subsyndromal unipolar and bipolar disorders: comparisons on positive and negative affect. J Abnorm Psychol. 1995;104:381–384. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.2.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ. A review of evidence-based psychosocial interventions for bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 11):28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear MK, Greist JH. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:461–464. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa S. A farewell to Bonferroni: The problems of low statistical power and publication bias. Behav Ecol. 2004;15:1044–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlickova H, Varese F, Smith A, Myin-Germeys I, Turnbull OH, Emsley R, Bentall RP. The dynamics of mood and coping in bipolar disorder: longitudinal investigations of the inter-relationship between affect, self-esteem and response styles. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis RH, Ostacher MJ, Patel JK, Marangell LB, Zhang H, Wisniewski SR, et al. Predictors of recurrence in bipolar disorder: primary outcomes from the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) Am J Psychiat. 2006;163:217–224. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, Jarrett RB, Trivedi MH. The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychol Med. 1996;26:477–486. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700035558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simhandl C, Konig B, Amann BL. A prospective 4-year naturalistic follow-up of treatment and outcome of 300 bipolar I and II patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75:254–262. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soreca I, Frank E, Kupfer DJ. The phenomenology of bipolar disorder: what drives the high rate of medical burden and determines long-term prognosis? Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:73–82. doi: 10.1002/da.20521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suppes T, Mintz J, McElroy SL, Altshuler LL, Kupka RW, Frye MA, Keck PE, Jr, Nolen WA, Leverich GS, Grunze H, Rush AJ, Post RM. Mixed hypomania in 908 patients with bipolar disorder evaluated prospectively in the Stanley Foundation Bipolar Treatment Network: a sex-specific phenomenon. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1089–1096. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, Bentall RP. Hypomanic traits and response styles to depression. Br J Clin Psychol. 2002;41:309–313. doi: 10.1348/014466502760379154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson ER. Development and Validation of an Internationally Reliable Short-Form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) J Cross Cult Psychol. 2007;38:227–242. [Google Scholar]

- Vieta E, Sanchez-Moreno J, Lahuerta J, Zaragoza S. Subsyndromal depressive symptoms in patients with bipolar and unipolar disorder during clinical remission. J Affect Disord. 2008;107:169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Carey G. Positive and negative affectivity and their relation to anxiety and depressive disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 1988;97:346–353. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.3.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]