Abstract

Wnt signaling plays important roles in normal development as well as pathophysiological conditions. The Dapper antagonist of β-catenin (Dact) proteins are modulators of both canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling via direct interactions with Dishevelled (Dvl) and Van Gogh like-2 (Vangl2). Here, we report the dynamic expression patterns of two zebrafish dact3 paralogs during early embryonic development. Our whole mount in situ hybridization (WISH) analysis indicates that specific dact3a expression starts by the tailbud stage in adaxial cells. Later, it is expressed in the anterior lateral plate mesoderm, somites, migrating cranial neural crest, and hindbrain neurons. By comparison, dact3b expression initiates on the dorsal side at the dome stage and soon after is expressed in the dorsal forerunner cells (DFCs) during gastrulation. At later stages, dact3b expression becomes restricted to the branchial neurons of the hindbrain and to the 2nd pharyngeal arch. To investigate how zebrafish dact3 gene expression is regulated, we manipulated retinoic acid (RA) signaling during development and found it negatively regulates dact3b in the hindbrain. Our study is the first to document the expression of the paralogous zebrafish dact3 genes during early development and demonstrate dact3b can be regulated by RA signaling. Therefore, our study opens up new avenues to study Dact3 function in the development of multiple tissues and suggests a previously unappreciated cross regulation of Wnt signaling by RA signaling in the developing vertebrate hindbrain.

Keywords: Dact, Dishevelled, Wnt signaling, retinoic acid signaling, vertebrate development

1. Introduction

Wnt signaling regulates animal development and homeostasis through directing numerous fundamental cellular processes including cell specification, proliferation, differentiation, migration, and stem cell self-renewal (Clevers and Nusse, 2012; Logan and Nusse, 2004; MacDonald et al., 2009). The Dapper antagonist of β-catenin (Dact) protein family was initially isolated from yeast-two hybrid screens with the Dishevelled (Dvl) PDZ domain as bait (Cheyette et al., 2002; Gloy et al., 2002). Since then, three Dact family members Dact1, Dact2, and Dact3 have been reported in vertebrates. All three have been reported in humans and mice, Dact1 and Dact2 have been reported in zebrafish and chicken (Alvares et al., 2009), and Dact1 has been reported in Xenopus (Cheyette et al., 2002; Gloy et al., 2002). Structurally, the Dact proteins share a number of conserved domains (Waxman et al., 2004). However, it is the conserved N-terminal leucine zipper domain (LZD) and C-terminal PDZ-binding (PDZB) domain that have been implicated in different Wnt-related functions (Brott and Sokol, 2005; Cheyette et al., 2002; Gloy et al., 2002; Waxman et al., 2004). The N-terminal LZD of Dact1 has been shown to interact with LEF/TCF proteins and is involved in homo- and heterodimerization of Dact proteins (Hikasa and Sokol, 2004; Kivimäe et al., 2011). While the PDZ-binding domain is necessary and sufficient for interaction with Dvl (Gloy et al., 2002), more recent studies have indicated that this domain is important for facilitating interactions with several other proteins, including Vangl2, PKA, PKC, CK1δ/ε, and p120ctn (Kivimäe et al., 2011). Thus, from the many interactions with regulators of Wnt signaling, in particular Dvl, Dact function in cellular signaling and proper embryonic development is likely very much dependent on the nature of the proteins it interacts with in a given context.

Dact1 orthologs have been the best studied of this protein family. In Xenopus, Dact1 can inhibit both β-catenin (canonical branch) and JNK (non-canonical branch) downstream of Dvl with a requirement in proper notochord and head development (Cheyette et al., 2002; Gloy et al., 2002). Additionally, dact1 was shown to mediate lysosome-inhibitor regulated Dvl degradation (Zhang et al., 2006). With respect to regulation of canonical Wnt signaling, Dact1 can also act more downstream of Dvl. Dact1 associates with TCF3 independent of β-catenin in Xenopus (Hikasa and Sokol, 2004), inhibits β-cat/LEF interactions in the nucleus, and promotes HDAC recruitment to LEF promoters (Gao et al., 2008). Interestingly, Dact1 can also act as a positive regulator of canonical Wnt signaling (Gloy et al., 2002; Park et al., 2006; Suriben et al., 2009; Waxman, 2005; Yang et al., 2013). Gain-of-function studies have found that co-injection of Dvl and Dact1 can promote canonical Wnt signaling. In zebrafish, depletion of Dact1 can enhance anteriorization due to the loss of canonical Wnt signaling in a wnt8 hypomorphic background. While the molecular mechanism behind this context dependent switch in function of Dact proteins in canonical Wnt signaling remains elusive, phosphorylation status of Dact1 has been suggested to be a decisive factor (Teran et al., 2009). Although studies in non-mammalian vertebrates primarily suggested that Dact1 proteins function to regulate canonical Wnt signaling, Dact1 knockout (KO) mice show severe urogenital defects and posterior body malformations, which has been associated with impaired Wnt-PCP signaling (Suriben et al., 2009; Wen et al., 2010). In humans, Dact1 mutations have been found in patients with neural tube defects (NTD) (Shi et al., 2012) and altered expression is found in many types of cancers (Astolfi et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2010; Yau et al., 2005; Yin et al., 2013; Yuan et al., 2012). Therefore, Dact1 has a multitude of functions regulating different types of Wnt signaling in developmental and disease contexts.

Similar to Dact1, Dact2 regulates different Wnt signals and has been proposed to also regulate TGF-β signaling (Su et al., 2007). During early zebrafish development, Dact2 regulates proper convergent extension movements. However, in mice, Dact2 functions as a negative regulator of canonical Wnt signaling in tooth development via interacting with and repressing pitx2 expression (Li et al., 2013). Dact2 has also been shown to attenuate TGF-β/Nodal signaling by facilitating lysosomal degradation of type I receptors ALK4 and ALK5 during mesoderm induction (Lee et al., 2010; Su et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2004). Although Dact2 null mice are viable, they exhibit accelerated wound healing due to enhanced TGF-β signaling (Meng et al., 2008).

To this point, Dact3 has been the least studied Dact member. Its expression has only been described for mice and it had been suggested that it may only be specific to mammals (Fisher et al., 2006). Epigenetic repression of Dact3 has been shown to be associated with increased canonical Wnt signaling in colorectal cancer, suggesting in this context Dact3 acts as a negative regulator of canonical Wnt signaling (Jiang et al., 2008). Dact3 null mice did not display any obvious morphological abnormalities, but they have a slightly smaller body weight than wild type (WT) siblings indicating Dact3 has a role in postnatal development in mice (Xue et al., 2013). Furthermore, unilateral ureteral obstruction in Dact3 knockout mice produced noticeable kidney fibrosis along with increased Dvl2 and β-catenin, expression of several Wntresponsive fibrotic, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition marker genes (Xue et al., 2013). Together with a previous report, these observations support that Dact3 can act as a canonical Wnt signaling antagonist (Jiang et al., 2008).

We wanted to better understand the evolution of the Dact family of proteins in vertebrates. Although the expression and function of dact1 and dact2 have been previously reported in zebrafish (Waxman, 2005), the identity and putative expression pattern of any zebrafish Dact3 orthologs has not been determined. Here, we report the expression of two zebrafish Dact3 paralogs, dact3a and dact3b, during early development. Our finding also indicates that retinoic acid (RA) signaling negatively regulates dact3b expression in the zebrafish hindbrain, suggesting a previously unexplored regulation of Wnt signaling by RA signaling in the vertebrate hindbrain.

2. Results and discussions

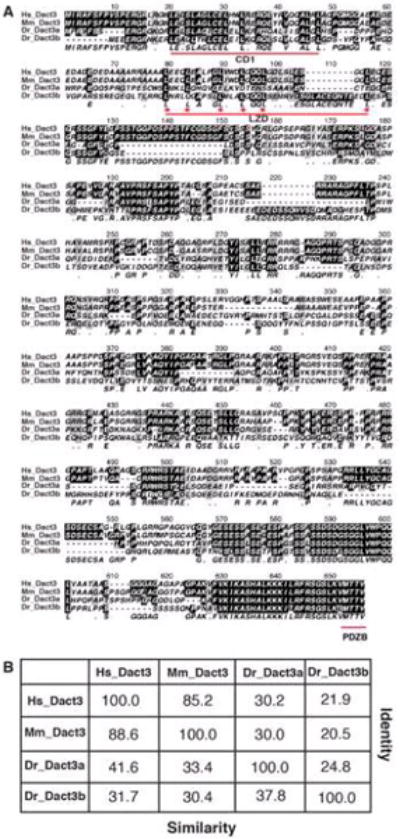

2.1 Comparison of Dact protein sequences

Examining the current zebrafish genome (Zv9; ensemble.org), we found that there are two predicted zebrafish dact3-like paralogs. The first predicted zebrafish dact3-like gene (XM_005172584) is located on Chromosome (Chr) 10, has 4 exons, and encodes a 586 amino acid protein. The second dact3-like gene (XM_001340960) has 5 exons encoding a 533 amino acid protein. In order to determine the level of conservation of zebrafish dact3-like genes with the mammalian dact3 orthologs, we performed sequence alignments using Clustal W for human (Hs), mice (Mm) and zebrafish (Dr) Dact3s. The zebrafish dact3-like gene on Chr 10 shares greater homology with both human and mice Dact3s compared to the dact3-like gene on Chr 18, so we now refer to them as dact3a and dact3b, respectively (Fig. 1A, B). While the overall amount of conservation is not high among the Dact3 proteins, there was greater conservation of an N-terminal coiled domain (CD1) and leucine zipper domains (LZD) (Waxman et al., 2004). Despite the overall higher conservation of dact3a with the mammalian Dact3 genes, its LZD was actually less conserved than dact3b. The C-terminal PDZ-binding (PDZB) domain for Dact3 homologs is completely conserved (Fig. 1A). Comparing the four zebrafish Dact homologs, we found greater conservation of sequence between zebrafish Dact1 and Dact2 than between either zebrafish Dact3 paralog (Fig 2A, B). The alignments between the four zebrafish Dact proteins indicate a strongly conserved PDZ-binding domain, except for a threonine (T) to leucine (L) change in Dact2 sequence. Interestingly, the N-terminal CD1 domain again is more highly conserved than the, LZD domain, which is not as easily identifiable (Fig. 2A) in the alignments of the zebrafish Dact proteins. The high conservation of the PDZ-binding domain is understandable, as deletion studies have reported that it is essential for interactions with multiple proteins (Cheyette et al., 2002). Therefore, this analysis of zebrafish Dact3a and Dact3b shows that Dact3 proteins are conserved in non-mammalian vertebrates.

Figure 1. Sequence alignments of vertebrate Dact3 proteins.

A: Comparison of human (Hs), mouse (Mm), and zebrafish (Dr) Dact3 protein sequences revealed conservation of the N-terminal CD1 and LZD domains and the C-terminal PDZ-binding domain. Conserved domains are underlined in red. 6 conserved leucines of the LZD are indicated with red stars. B: Table with the amino acid identity (Y-axis) and similarity scores (X-axis) of Hs, Mm and Dr Dact3 homologs.

Figure 2. Sequence alignments of zebrafish Dact proteins.

A: Comparison of zebrafish (Dr) Dact1, Dact2, and Dact3a and Dact3b protein sequences revealed greater conservation of the N-terminal CD1 and C-terminal PDZ-binding domains, with less conservation of the LZD domain. Conserved domains are underlined in red. 5 conserved leucines of the LZD are indicated with red stars. B: Table with the amino acid identity (Y-axis) and similarity scores (X-axis) of Dr Dact proteins.

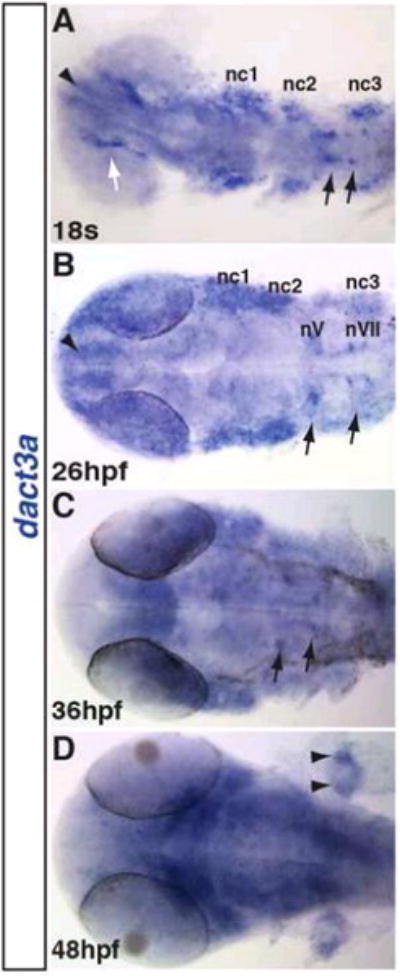

2.3 Dact3a is expressed in the somites, neural crest cells and hindbrain neurons

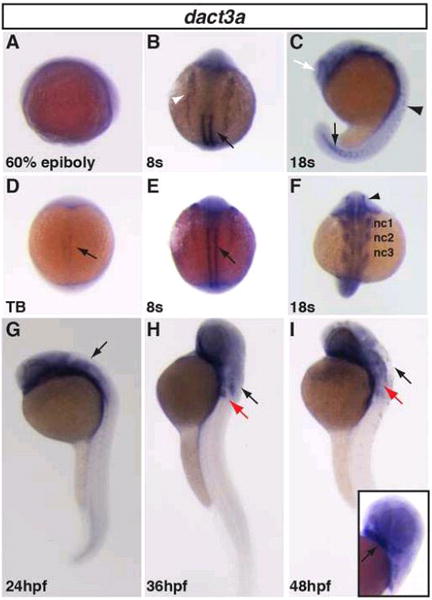

To analyze the spatio-temporal expression patterns of dact3a and dact3b, we performed whole mount in situ hybridization (WISH) and reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) at stages of zebrafish development starting from the dome stage until 48 hours post fertilization (hpf). Although we could detect dact3a expression with RT-PCR by the shield (SH) stage (Fig. 3), with WISH we were not able to detect specific dact3a expression until the tailbud (TB) stage, when it appeared in adaxial mesodermal cells (Fig. 4D). Initial expression of dact3a is seen much later than dact1 and dact2, which appears to be present as early as the high stage with dorsal-specific expression (Waxman, 2005). At the 8 somite (s) stage, dact3a expression is observed in the anterior lateral plate mesoderm (ALPM) and prominently in the adaxial cells of the somites (Fig. 4B, E). By the 18s stage, dact3a is expressed in the posterior, newly forming somites, the 3 (mandibular, hyoid and branchial) streams of migrating cranial neural crest cells (Diogo et al., 2007; Schilling and Kimmel, 1997; Sperber et al., 2008), the anterior brain, hindbrain neurons, and spinal cord neurons (Fig. 4C, F). Flat mounting of the probed embryos at 18s revealed that dact3a is expressed in the telencephalon and lines the inner periphery of eye. At this stage, dact3a is also expressed in the precursors to the cranial branchiomotor neurons (Fig 5A) and by 26 hpf in the trigeminal (V) the facial (VII) neurons (Fig 5B) (Auclair et al., 1996; Chandrasekhar, 2003; Studer et al., 1995). The expression in the hindbrain persists through 48 hpf (Fig. 4H, I and Fig. 5C, D), while the dact3a expression in the cranial cartilage is consistent with it being derived from the cranial neural crest (Fig 4J) (Schilling and Kimmel, 1997). By 36hpf, dact3a expression also initiated in the pectoral fin bud (Fig. 4H). At 48 hpf, it is also interesting to notice that the pectoral fin bud expression of dact3a is present in two separate domains, consistent with expression in the pectoral muscle (Fig 5D) (Ahn and Ho, 2008; Thorsen and Hale, 2005). By comparison, zebrafish dact2 is also expressed in the pectoral fin bud (Waxman et al., 2004)

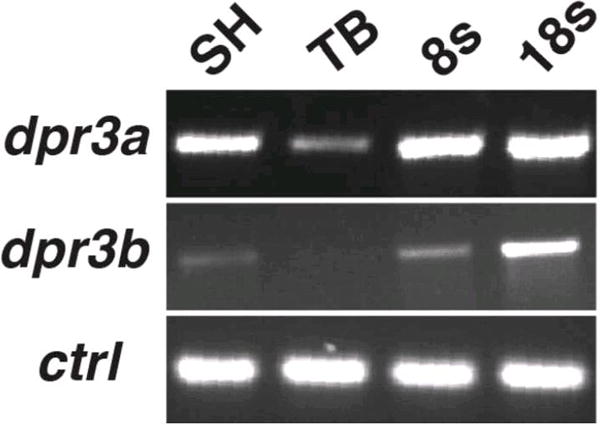

Figure 3. RT-PCR analysis of dact3a and dact3b gene expression.

Expression of dact3a and dact3b analyzed by RT-PCR at the indicated stages. Solo served as a positive control.

Figure 4. Zebrafish dact3a expression from 60% epiboly through 48hpf.

A: Specific dact3a expression was not observed at 60% epiboly, even though it is detectable by RT-PCR (Fig. 3). D: Dact3a expression in the adaxial mesoderm at the TB stage (black arrow). B,E: Dact3a expression in the somites (black arrows) and anterior lateral plate mesoderm (white arrowhead) at the 8s stage. C: Expression at the telencephalon (white arrow), spinal cord neurons (black arrowhead), and the forming somites (black arrow) at the 18s stage. F: Mandibular (nc1), hyoid (nc2), and branchial (nc3) neural crest expression and medial eye expression (black arrowhead) at the 18s stage. G–I: Hindbrain expression at 24, 36 and 48hpf (black arrow). At 36 and 48 hpf, dact3a expression is visible in the pectoral fin bud (red arrow). Inset: Cartilage expression (black arrow) at 48hpf. A, C, G, H, I are lateral views. B, D, E, F are dorsal views. Anterior up in all the images.

Figure 5. Dact3a expression in the brain.

A: Dact3a expression in the telencephalon (black arrowhead), medial eye (white arrow), neural crest (nc1, 2, 3) and hindbrain neurons (black arrows). B: Expression in the nV (trigeminal) and nVII (facial) cranial branchiomotor neurons (black arrows). C: Expression in the branchiomotor neurons (black arrows). D: Pectoral fin bud expression in two distinct domains (black arrowheads). All the images are dorsal with anterior right.

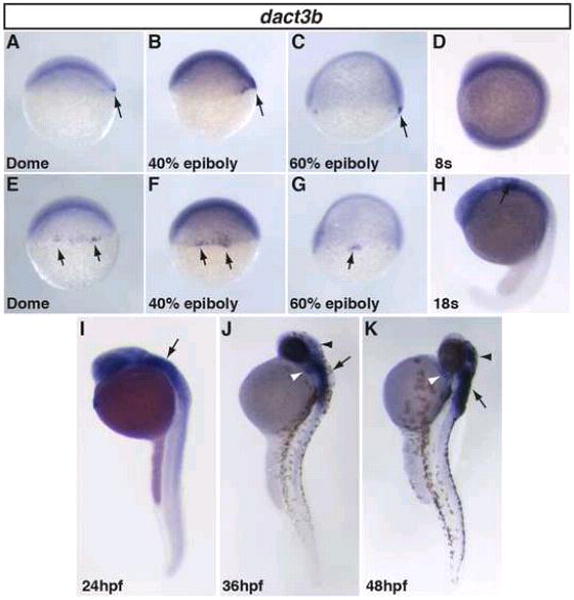

2.4 Dact3b is expressed in the dorsal forerunner cells and brain

In contrast to dact3a, which did not have specific expression until the TB stage, localized dact3b expression begins at the dome stage in a cluster of cells at the dorsal blastoderm (Fig. 6A, E), very similar to what has been reported for zebrafish dact1 (Waxman, 2005). The dorsal dact3b expression maintained through 40% epiboly (Fig. 6B, F). Compared to zebrafish dact1 and dact2 at the same developmental stages, the dorsal region expressing dact3b is narrower and the onset of expression is delayed (Waxman, 2005). By 60% epiboly, this scattered dorsal expressing cell population starts to reduce and become concentrated in only a few cells at the dorsal blastoderm margin (Fig. 6C, G). These dorsal expressing cells appear to be the dorsal forerunner cell population (DFC), because they are located below the blastoderm margin (Fig. 6C, G). Although the DFCs give rise to Kupffer’s vesicle (Cooper and D’Amico, 1996), we did not observe dact3b expression in the Kupffer’s vesicle (data not shown), suggesting the DFC expression is not maintained in these cells after gastrulation. By the end of gastrulation at the TB stage, dact3b expression waned, as we did not detect specific expression via WISH or significant transcripts via RT-PCR (Fig. 3 and data not shown). Furthermore, even though dact3b expression increased by the 8s stage, we did not detect noticeable specific dact3b expression until late somitogenesis stages (Figs. 3 and 6D, H). The lack of expression from the end of gastrulation through early somitogenesis contrasts with zebrafish dact1, dact2, and dact3a, which are all expressed throughout these stages in the somites, tailbud, brain, and spinal cord (Figs. 4 and 5) (Gillhouse et al., 2004).

Figure 6. Zebrafish dact3b expression from dome through 48hpf.

A–C, E–G: Dact3b expression in the dorsal blastoderm margin from dome through 60% epiboly stage (black arrow). D: Specific dact3b is not expressed at the 8s stage, even though we could detect it with RT-PCR (Fig. 3). H,I: Dact3b expression in the hindbrain starts at 18s and is maintained through 24 hpf embryos (arrow). J,K: Dact3b expression initiates in the 2nd pharyngeal arch (white arrowheads) and the dorsal region of the midbrain/tectum (black arrowheads) at 36hpf and is maintained through 48 hpf. Dact3b continues to be expressed in the hindbrain at 36 and 48hpf (black arrows). A–D and H–K are lateral views with dorsal rightward. E–G are dorsal views. In all images, anterior is up.

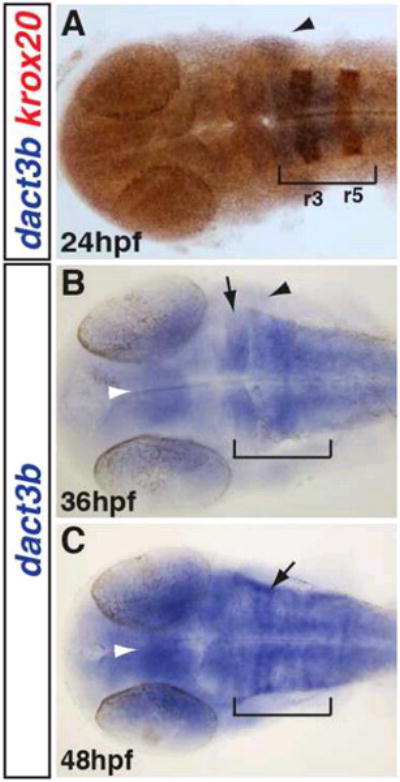

Beginning at the 18s stage, specific dact3b expression initiates in the hindbrain (Fig. 6H). As development proceeds, this expression persists and expands posteriorly by 24hpf (Fig. 6I). To examine the relative location of dact3b in the hindbrain, we performed double WISH at 24hpf with krox-20. This revealed dact3b expression resided in r2 through r6, with more medial expression in r3–r6 (Fig. 7A). At this stage, dact3b is also found in the 2nd pharyngeal arch (Fig. 7A). By 36hpf, we found expression begins in the anterior tectum/midbrain region (Fig. 6I and Fig. 7B) and extended up to the midbrain-hindbrain boundary. As development proceeds, the intensity of dact3b expression in these neural tissues becomes stronger through 48 hpf (Fig. 6K and 7C), with hindbrain expression in a striped pattern consistent with cranial branchiomotor neurons (Chandrasekhar et al., 1997) (Fig. 7C). Interestingly, the hindbrain expression patterns for dact3b is more anterior compared to dact3a at the comparable stages (Fig. 5).

Figure 7. Dact3b expression in the hindbrain.

A: Double WISH for dact3b and krox-20 at 24 hpf. Krox-20 (orange) is expressed in r3 and r5. Dact3b expression is from r2 through r6 (brackets). dact3b is expressed in the adjacent 2nd pharyngeal arch (black arrowhead). B: Dact3b expression extends more anteriorly past the midbrain-hindbrain boundary (black arrow) and is expressed in the tectum by 36 hpf (white arrowhead). 2nd pharyngeal arch expression is maintained (black arrowhead). C: By 48 hpf, dact3b expression is increased and is in stripes consistent with anterior branchiomotor neuron expression (black arrow) (Chandrasekhar et al., 1997). Embryos in images were flat mounted. Images are dorsal views with anterior to the left.

Comparing the previously reported expression patterns of zebrafish dact1 and dact2 to dact3a and dact3b, respectively, revealed that prior to gastrulation, dact3b is more similar to zebrafish dact1 and dact2 as they all share dorsally localized expression. After gastrulation, dact3a expression is more similar to dact1 and dact2 expression than its paralog dact3b, as dact3a shares broader expression in the somites, brain, and lateral plate mesoderm (Waxman et al., 2004). Although all four dact genes are expressed in the brain during development, dact1 and dact2 brain specific expression begins as early as the TB stage, while both dact3a and dact3b expression initiates after mid-somitogenesis stages.

In comparing zebrafish dact3 paralog expression to the expression of the single mouse Dact3 gene, dact3a expression is more similar to the mouse Dact3 than dact3b. The_mouse Dact3 is expressed in the somites, fore- and hind limb buds, otic vesicle, aortic arches, craniofacial mesenchyme, tail bud and central nervous system (Fisher et al., 2006). Likewise, dact3a is expressed in the somites, pectoral fin bud, cranial neural crest cells, and hindbrain neurons. Zebrafish dact3b, however, is not as broadly expressed as the mouse Dact3. While zebrafish dact3b is expressed only in the 2nd pharyngeal arch, mouse Dact3 and zebrafish dact3a are both expressed throughout all the pharyngeal arches. Interestingly, although the mouse Dact3 was not reported in the brain during development, it is prominently expressed in the adult brain and specifically in the cerebral cortex. We find specific regional expression of both dact3a and dact3b in the zebrafish brain during development that is reminiscent of the expression in the adult mouse.

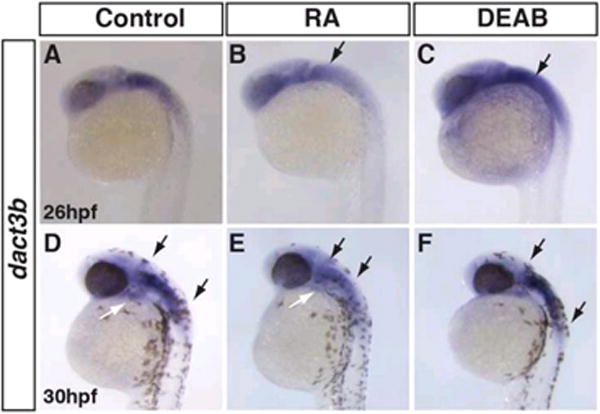

2.5 RA signaling negatively regulates dact3 expression in the hindbrain

We next wanted to understand if any of the major developmental signaling pathways, including canonical Wnt, FGF, BMP, and RA signaling regulate either dact3a and dact3b expression in the zebrafish hindbrain. To modulate RA signaling, we treated the embryos beginning at the 16s stage and 24 hpf with RA and diethylaminobenzaldehyde (DEAB), a retinaldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitor that inhibits RA synthesis (Russo et al., 1988). Following treatment, embryos were fixed at 24hpf and 30hpf, respectively, and analyzed for dact3b expression. Examination of the embryos treated with exogenous RA revealed that at both stages RA induced a significant decrease in dact3b expression (Fig. 8A, B). Conversely, treatment with DEAB resulted in expansion of dact3b expression within the hindbrain and extension posteriorly into the spinal cord (Fig. 8A, C). In the 30hpf embryos, treatment with RA also diminished the pharyngeal expression (Fig. 8D. E). Similar effects were not seen on the dact3a hindbrain expression when RA signaling was manipulated at these stages nor did we find that RA signaling affected dact3a expression at earlier stages (data not shown). Manipulation of Wnt, FGF, and BMP signaling pathways utilizing heat-shock inducible transgenic fish lines at similar stages did not affect dact3b expression in the hindbrain (data not shown). Together, our data suggest that RA signaling negatively regulates dact3b expression in the anterior hindbrain, but not dact3a in the posterior hindbrain, in zebrafish. Cross talk between Wnt and RA signaling has been studied in a variety of developmental contexts, including hematopoietic stem cell development, chondrocyte formation, and adipogenesis (Chanda et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013; Yasuhara et al., 2010). Our present findings suggest a previously unappreciated access point for the cross-regulation of Wnt signaling by RA signaling and provide a basis of future investigations targeting how Dact3 proteins function within the hindbrain to integrate the Wnt and RA signaling networks.

Figure 8. RA signaling negatively regulates dact3b expression.

A, D: Control embryos B, E: Treatment with exogenous RA extinguishes dact3b expression in the hindbrain (black arrows) and 2nd pharyngeal arch (white arrow in E). C, F: Inhibition of RA signaling lead to an expansion of dact3b expression domain with the hindbrain (compare the length between arrows in D and F). Images are lateral views with anterior to upward.

Experimental procedures

Zebrafish husbandry and maintenance

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) were raised and maintained following standardized laboratory conditions (Westerfield, 2000). Embryos were collected from crosses between WT strains and raised at 28.5°C in an incubator before fixing at desired stages for analysis. Staging was done as reported previously (Kimmel et al., 1995).

Generation of dact3a and dact3b probes

629 bp of dact3a and 759 bp of dact3b sequence were amplified from mixed stage cDNA using the following primers: Forward dact3a: 5′-TGAAGGTGGACACAGAGAACAGC. Reverse dact3a: 5′- ATAGGTCGTGGGTCTTGCTTGG. Forward dact3b: 5′-ATTTTCTGCCCCATACCCCC Reverse dact3b: 5′-ACGCAACTGTCCTCTGAACGAG. The amplified products were cloned into pGemT-Easy (Promega), sequenced, and anti-sense probe was synthesized using standard methods. Probe used for krox-20 was previously reported (ZDB-GENE-980526-283).

Phylogenetic analysis

Full-length sequence for all Dact members of human, mice and zebrafish was obtained from NCBI website. Sequence alignments were performed using Clustal W in MacVector.

RT-PCR analysis

30 embryos at the designated stages were homogenization in TRIzol reagent (Ambion). RNA was prepared using Pure link RNA Micro Kit (In Vitrogen). cDNA was synthesized using the ThermoScript Reverse Transcriptase kit (Invitrogen). RT-PCR was performed using the primers that were used to make probe for the respective genes. Control for expression is solo a ubiquitously expressed gene at the stages mentioned.

Wholemount in situ hybridization (WISH)

WISH was performed as described previously (Waxman et al., 2008). Images were taken using a Zeiss M2BioV12 stereomicroscope and Zeiss AxioImager 2. Pigmentation was prevented at later stages using 0.003% 1-phenyl-2-thiouera (PTU) treatment starting at 24 hpf.

Drug treatment

WT embryos were treated with 1 μm RA and 1μm DEAB and placed on a Nutator at 28.5°C. Treatment was performed beginning at 16hpf and 24hpf followed by fixation at 24hpf and 30hpf, respectively.

Highlights.

We investigated dact3a and dact3b expression during early zebrafish development.

Sequence alignments show strongest conservation in the PDZ-binding domains.

dact3a is expressed in the lateral plate mesoderm, somites, and neural crest.

dact3b is expressed in the dorsal forerunner cells (DFC) and hindbrain.

Retinoic acid signaling negatively regulates dact3b expression in the hindbrain.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R01 HL112893-A1 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to JSW.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahn D, Ho RK. Tri-phasic expression of posterior Hox genes during development of pectoral fins in zebrafish: implications for the evolution of vertebrate paired appendages. Developmental biology. 2008;322:220–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvares L, Winterbottom F, Jorge E, Rodrigues Sobreira D, Xavier-Neto J, Schubert F, Dietrich S. Chicken dapper genes are versatile markers for mesodermal tissues, embryonic muscle stem cells, neural crest cells, and neurogenic placodes. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2009;238:1166–1178. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astolfi A, Nannini M, Pantaleo M, Di Battista M, Heinrich M, Santini D, Catena F, Corless C, Maleddu A, Saponara M, Lolli C, Di Scioscio V, Formica S, Biasco G. A molecular portrait of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an integrative analysis of gene expression profiling and high-resolution genomic copy number. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 2010;90:1285–1294. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auclair F, Vald√©s N, Marchand R. Rhombomere-specific origin of branchial and visceral motoneurons of the facial nerve in the rat embryo. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1996;369:451–461. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960603)369:3<451::AID-CNE9>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brott B, Sokol S. Frodo proteins: modulators of Wnt signaling in vertebrate development. Differentiation; research in biological diversity. 2005;73:323–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2005.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanda B, Ditadi A, Iscove N, Keller G. Retinoic acid signaling is essential for embryonic hematopoietic stem cell development. Cell. 2013;155:215–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar A. Turning heads: development of vertebrate branchiomotor neurons. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2003;229:143–161. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar A, Moens CB, Warren JT, Jr, Kimmel CB, Kuwada JY. Development of branchiomotor neurons in zebrafish. Development. 1997;124:2633–2644. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.13.2633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheyette BN, Waxman JS, Miller JR, Takemaru KI, Sheldahl LC, Khlebtsova N, Fox EP, Earnest T, Moon RT. Dapper, a Dishevelled-associated antagonist of beta-catenin and JNK signaling, is required for notochord formation. Developmental cell. 2002;2:449–461. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012;149:1192–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper MS, D’Amico LA. A cluster of noninvoluting endocytic cells at the margin of the zebrafish blastoderm marks the site of embryonic shield formation. Developmental biology. 1996;180:184–198. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diogo R, Hinits Y, Hughes SM. Development of mandibular, hyoid and hypobranchial muscles in the zebrafish: homologies and evolution of these muscles within bony fishes and tetrapods. BMC developmental biology. 2007;8:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DA, Kivim√§e S, Hoshino J, Suriben R, Martin P-MM, Baxter N, Cheyette BN. Three Dact gene family members are expressed during embryonic development and in the adult brains of mice. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2006;235:2620–2630. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Wen J, Zhang L, Li X, Ning Y, Meng A, Chen YG. Dapper1 is a nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein that negatively modulates Wnt signaling in the nucleus. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:35679–35688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804088200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillhouse M, Wagner Nyholm M, Hikasa H, Sokol S, Grinblat Y. Two Frodo/Dapper homologs are expressed in the developing brain and mesoderm of zebrafish. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2004;230:403–409. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloy J, Hikasa H, Sokol SY. Frodo interacts with Dishevelled to transduce Wnt signals. Nature cell biology. 2002;4:351–357. doi: 10.1038/ncb784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikasa H, Sokol S. The involvement of Frodo in TCF-dependent signaling and neural tissue development. Development (Cambridge, England) 2004;131:4725–4734. doi: 10.1242/dev.01369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Tan J, Li J, Kivimäe S, Yang X, Zhuang L, Lee P, Chan M, Stanton L, Liu E, Cheyette B, Yu Q. DACT3 is an epigenetic regulator of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in colorectal cancer and is a therapeutic target of histone modifications. Cancer cell. 2008;13:529–541. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Choi HR, Park A, Shin SM, Bae KH, Lee S, Kim IC, Kim W. Retinoic acid inhibits adipogenesis via activation of Wnt signaling pathway in 3T3–L1 preadipocytes. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2013;434:455–459. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.03.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel C, Ballard W, Kimmel S, Ullmann B, Schilling T. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivimäe S, Yang X, Cheyette B. All Dact (Dapper/Frodo) scaffold proteins dimerize and exhibit conserved interactions with Vangl, Dvl, and serine/threonine kinases. BMC biochemistry. 2011;12:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-12-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WC, Hough M, Liu W, Ekiert R, Lindström N, Hohenstein P, Davies J. Dact2 is expressed in the developing ureteric bud/collecting duct system of the kidney and controls morphogenetic behavior of collecting duct cells. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology. 2010;299:51. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00148.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Florez S, Wang J, Cao H, Amendt B. Dact2 represses PITX2 transcriptional activation and cell proliferation through Wnt/beta-catenin signaling during odontogenesis. PloS one. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan C, Nusse R. The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2004;20:781–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.113126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald B, Tamai K, He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Developmental cell. 2009;17:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng F, Cheng X, Yang L, Hou N, Yang X, Meng A. Accelerated re-epithelialization in Dpr2-deficient mice is associated with enhanced response to TGFbeta signaling. Journal of cell science. 2008;121:2904–2912. doi: 10.1242/jcs.032417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J-i, Ji H, Jun S, Gu D, Hikasa H, Li L, Sokol S, McCrea P. Frodo links Dishevelled to the p120-catenin/Kaiso pathway: distinct catenin subfamilies promote Wnt signals. Developmental cell. 2006;11:683–695. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo JE, Hauguitz D, Hilton J. Inhibition of mouse cytosolic aldehyde dehydrogenase by 4-(diethylamino)benzaldehyde. Biochemical pharmacology. 1988;37:1639–1642. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling TF, Kimmel CB. Musculoskeletal patterning in the pharyngeal segments of the zebrafish embryo. Development (Cambridge, England) 1997;124:2945–2960. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.15.2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Ding Y, Lei YP, Yang XY, Xie GM, Wen J, Cai CQ, Li H, Chen Y, Zhang T, Wu BL, Jin L, Chen YG, Wang HY. Identification of novel rare mutations of DACT1 in human neural tube defects. Human mutation. 2012;33:1450–1455. doi: 10.1002/humu.22121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperber SM, Saxena V, Hatch G, Ekker M. Zebrafish dlx2a contributes to hindbrain neural crest survival, is necessary for differentiation of sensory ganglia and functions with dl×1a in maturation of the arch cartilage elements. Developmental biology. 2008;314:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer M, Lumsden A, Ariza-McNaughton L, Bradley A, Krumlauf R. Altered segmental identity and abnormal migration of motor neurons in mice lacking Hoxb-1. Nature. 1995;384:630–634. doi: 10.1038/384630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y, Zhang L, Gao X, Meng F, Wen J, Zhou H, Meng A, Chen YG. The evolutionally conserved activity of Dapper2 in antagonizing TGF-beta signaling. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2007;21:682–690. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6246com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suriben R, Kivimäe S, Fisher D, Moon R, Cheyette B. Posterior malformations in Dact1 mutant mice arise through misregulated Vangl2 at the primitive streak. Nature genetics. 2009;41:977–985. doi: 10.1038/ng.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teran E, Branscomb A, Seeling J. Dpr Acts as a molecular switch, inhibiting Wnt signaling when unphosphorylated, but promoting Wnt signaling when phosphorylated by casein kinase Idelta/epsilon. PloS one. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorsen DH, Hale ME. Development of zebrafish (Danio rerio) pectoral fin musculature. J Morphol. 2005;266:241–255. doi: 10.1002/jmor.10374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman J, Keegan B, Roberts R, Poss K, Yelon D. Hoxb5b acts downstream of retinoic acid signaling in the forelimb field to restrict heart field potential in zebrafish. Developmental cell. 2008;15:923–934. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman JS. Regulation of the early expression patterns of the zebrafish Dishevelled-interacting proteins Dapper1 and Dapper2. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2005;233:194–200. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman JS, Hocking AM, Stoick CL, Moon RT. Zebrafish Dapper1 and Dapper2 play distinct roles in Wnt-mediated developmental processes. Development (Cambridge, England) 2004;131:5909–5921. doi: 10.1242/dev.01520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J, Chiang Y, Gao C, Xue H, Xu J, Ning Y, Hodes R, Gao X, Chen YG. Loss of Dact1 disrupts planar cell polarity signaling by altering dishevelled activity and leads to posterior malformation in mice. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:11023–11030. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.085381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. The Zebrafish book. A guide for the laboratory use of zebrafish (Danio rerio) 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Xue H, Xiao Z, Zhang J, Wen J, Wang Y, Chang Z, Zhao J, Gao X, Du J, Chen YG. Disruption of the Dapper3 gene aggravates ureteral obstruction-mediated renal fibrosis by amplifying Wnt/β-catenin signaling. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:15006–15014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.458448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Fisher D, Cheyette B. SEC14 and Spectrin Domains 1 (Sestd1), Dishevelled 2 (Dvl2) and Dapper Antagonist of Catenin-1 (Dact1) co-regulate the Wnt/Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) pathway during mammalian development. Communicative & integrative biology. 2013;6 doi: 10.4161/cib.26834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang ZQ, Zhao Y, Liu Y, Zhang JY, Zhang S, Jiang GY, Zhang PX, Yang LH, Liu D, Li QC, Wang EH. Downregulation of HDPR1 is associated with poor prognosis and affects expression levels of p120-catenin and beta-catenin in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Molecular carcinogenesis. 2010;49:508–519. doi: 10.1002/mc.20622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuhara R, Yuasa T, Williams J, Byers S, Shah S, Pacifici M, Iwamoto M, Enomoto-Iwamoto M. Wnt/beta-catenin and retinoic acid receptor signaling pathways interact to regulate chondrocyte function and matrix turnover. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:317–327. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.053926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau TO, Chan CY, Chan KL, Lee MF, Wong CM, Fan ST, Ng I. HDPR1, a novel inhibitor of the WNT/beta-catenin signaling, is frequently downregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma: involvement of methylation-mediated gene silencing. Oncogene. 2005;24:1607–1614. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, Xiang T, Li L, Su X, Shu X, Luo X, Huang J, Yuan Y, Peng W, Oberst M, Kelly K, Ren G, Tao Q. DACT1, an antagonist to Wnt/β-catenin signaling, suppresses tumor cell growth and is frequently silenced in breast cancer. Breast cancer research: BCR. 2013;15 doi: 10.1186/bcr3399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan G, Wang C, Ma C, Chen N, Tian Q, Zhang T, Fu W. Oncogenic function of DACT1 in colon cancer through the regulation of β-catenin. PloS one. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Gao X, Wen J, Ning Y, Chen YG. Dapper 1 antagonizes Wnt signaling by promoting dishevelled degradation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:8607–8612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600274200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Zhou H, Su Y, Sun Z, Zhang H, Zhang L, Zhang Y, Ning Y, Chen YG, Meng A. Zebrafish Dpr2 inhibits mesoderm induction by promoting degradation of nodal receptors. Science (New York, NY) 2004;306:114–117. doi: 10.1126/science.1100569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]