Abstract

We found recently that controlled progressive challenge with subthreshold levels of E.coli can confer progressively stronger resistance to future reinfection-induced sickness behavior to the host. We have termed this type of inflammation “euflammation”. In this study, we further characterized the kinetic changes in the behavior, immunological, and neuroendocrine aspects of euflammation. Results show euflammatory animals only display transient and subtle sickness behaviors of anorexia, adipsia, and anhedonia upon a later infectious challenge which would have caused much more severe and longer lasting sickness behavior if given without prior euflammatory challenges. Similarly, infectious challenge-induced corticosterone secretion was greatly ameliorated in euflammatory animals. At the site of E.coli priming injections, which we termed euflammation induction locus (EIL), innate immune cells displayed a partial endotoxin tolerant phenotype with reduced expression of innate activation markers and muted inflammatory cytokine expression upon ex vivo LPS stimulation, whereas innate immune cells outside EIL displayed largely opposite characteristics. Bacterial clearance function, however, was enhanced both inside and outside EIL. Finally, sickness induction by an infectious challenge placed outside the EIL was also abrogated. These results suggest euflammation could be used as an efficient method to “train” the innate immune system to resist the consequences of future infectious/inflammatory challenges.

Keywords: Neural-Immune, E.coli, Sickness Behavior, Inflammation, Innate Immunity, Euflammation

1. INTRODUCTION

Peripheral inflammation and the resultant release of cytokines have long been realized to be one of the main culprits in the pathogenesis of many CNS related disorders including, fatigue (Arnett and Clark, 2012), hyperalgesia (Sommer and Kress, 2004), anorexia (Langhans, 2007), and anhedonia (Salazar et al., 2012). Collectively these have been termed “sickness behavior” (Kelley et al., 2003). These centrally mediated sequelae are consistent features of systemic inflammation and are often associated with the presence of inflammagens or increased inflammatory cytokines in the blood. However, depending upon the level of the inflammatory challenge, sickness behavior may or may not manifest after localized peripheral inflammation. For example, well contained localized inflammation, such as those that occur during the healing of minor wounds, do not cause sickness behavior, but exhibit apparent local inflammatory histopathology including the infiltration of leukocytes and increased expression of inflammatory cytokines at the site of inflammation (Horan et al., 2005). We have recently simulated the type of inflammation that is unaccompanied with overt concomitant sickness behaviors by local administration of subthreshold levels of LPS or live E.coli. Interestingly, the kinetic responses to consecutive daily administration of subthreshold levels of LPS and E.coli differed dramatically. We found prior exposure to subthreshold levels of LPS sensitized mice to display a greater sickness behavior response upon subsequent LPS challenges (Tarr et al., 2012). However, following repeated E.coli administration, increased host resistance to the induction of sickness behavior by E.coli was evident if mice received prior challenges with subthreshold levels of E.coli (Chen et al., 2013). We have thus termed a peripheral inflammation that does not cause overt sickness behavior, yet primes the immune system to provide more resistance to a subsequent inflammatory stimulation as “euflammation.” By using this definition we have restricted the training of innate immune activity within the boundary of “absence of overt sickness behavior”, thereby preventing changes in the innate immunity from reaching hyper-inflammation. Additionally, we define the highest level of inflammagen that causes euflammation at a given time point without inducing decreased movement in the open field as maximal euflammatory potential (MEP).

Further investigation of euflammation needs to consider the dynamic characteristics of inflammatory response. Depending on the dose level of the bacterial challenge, the time point of maximal sickness behavioral responses may vary. In addition, cells that express receptors important in the recognition of pathogens and the propagation of the immune response (e.g., MHCII, TLR4, and CD86) are recruited to the site of infection (Albiger et al., 2007). Higher expression of these receptors is indicative of an “activated” cellular phenotype. Associated with the activated immune phenotype, inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), and interleukin-10 (IL-10) that are important in innate immune function and communication are also increased through NF-κB signaling mechanisms (Lawrence, 2009). Upon TLR4 activation, these cytokines are released and bactericidal mechanisms are activated (e.g., nitric oxide) to help eradicate the pathogen (Wei et al., 1995). Furthermore, once the opsonization of bacteria and the subsequent antibody binding has occurred, activated macrophages phagocytize the bacteria as an additional mechanism of host defense (Aderem and Underhill, 1999). In addition, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis are activated upon bacterial challenge (Zimomra et al., 2011) that is well known to play critical a role in inflammatory-induced immunological and behavioral effects.

Recent research shows following repeated administration of bacteria or bacterial components (i.e., LPS), endotoxin tolerance (ET) can emerge (Biswas and Lopez-Collazo, 2009) or a short-term innate memory (trained immunity) which might last for days to months (Netea, 2013) can be generated. However, the majority of the studies examining these phenomena has used high levels of inflammagen and/or has used intravenous administration that causes a systemic response. In our euflammation model we give progressive subthreshold doses of bacteria in the peritoneal cavity (i.e., euflammatory induction locus [EIL]) which could yield substantially different results. We refer to the peritoneal cavity as the EIL because repeated exposure of E.coli in the present study occurred only at this location during euflammation induction as opposed to ET models which cause systemic inflammation.

In light of our previous report describing the beneficial effects of progressive euflammatory injections on sickness behavior (Chen et al., 2013), this report sought to further characterize the immunological, behavioral, and neuroendocrine changes during the kinetic induction of euflammation. Specifically, studies were designed to: 1) assess the kinetic nature of our euflammatory paradigm, 2) evaluate the extrapolation potential of euflammation to additional sickness behaviors, 3) determine if innate immune activity and function inside and outside the EIL in euflammatory animals follow the pattern of ET and/or trained immunity, and 4) assess the ability of euflammation to regulate neuroendocrine responses.

2. METHODS

2.1. Subjects

Subjects were 6-8 week-old male FVB mice purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Upon arrival, animals were separated according to experimental design and allowed to acclimate in the animal facility for ~1 week prior to the start of experimental procedures. Mice were kept in standard polycarbonate mouse cages and maintained on a 12 hr light/dark cycle with lights being turned on at 0600 in an AAALAC (American Association of Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care) facility. Food and water was available ad libitum unless experimental manipulations were being conducted. Animals were treated in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 1996), and experiments were carried out in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee (ILACUC) at The Ohio State University.

2.2. Euflammation Induction

To obtain a robust euflammatory induction, E.coli cultures, strain, and injections were similar to procedures previously described by our laboratory (Chen et al., 2013). Briefly, animals were given intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of GPF labeled E.coli (LT004; kindly provided by Dr Monica Rydén Aulin of the Karolinska Institute, Solna, Sweden). Animals that received an E.coli injection(s) on the first day, second day, and/or third day (i.e., 2.0×107 on day 1, 25×107 on day 2, and 100×107 CFUs of E.coli on day 3) were designated as 1d-EU, 2d-EU, or 3d-EU groups, respectively. These progressive doses have reliably been shown to not cause overt sickness behavior in the open field box (Chen et al., 2013). 2.0×107 on day 1, 25×107 on day 2, and 100×107 CFUs of E.coli on day 3.

2.3. Experimental Designs

2.3.1. Experiment 1: Time-course assessment of open field locomoter activity following a single bolus injection of E.coli or 3d-EU

To determine what time following injection with E.coli caused the maximal behavioral sickness response, three groups of animals (n=10 per group) were tested in the open field for locomoter activity 1, 3, and 6 hrs following a single i.p. 25×107 E.coli injection. In addition, to assess if progressive euflammatory doses caused a shift in locomotor deficits another three groups of animals were given 3d-EU injections (n=8-9/group). On day 3, each one of the groups was tested for locomoter activity in the open field 1, 3, or 6 hrs following the last injection.

2.3.2. Experiment 2: Food/water intake and sucrose preference following 3d-EU and single bolus E.coli administrations

To evaluate if euflammation caused alterations in sickness behaviors other than locomoter deficits, three groups of animals were given PBS, 3d-EU, or a single dose of 100×107 E.coli on day 3 following PBS on days 1 and 2 which served as a positive control (designated PC in Figs. 2&3; cage n=3 with 3 animals/cage). Following injections, both food and water intake was measured 5 and 24 hrs following the last corresponding injection time point. In addition, additional signs of sickness behavior (i.e., anhedonia) were evaluated in 3 separate groups of animals (groups were the same as they were for food and water intake) for their preference of a sucrose solution 5 and 24 hrs following the last corresponding injection time point (cage n=4-5 with 2 animals/cage).

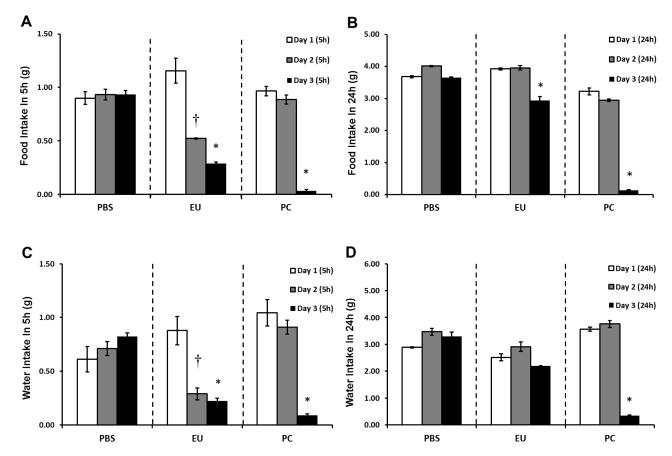

Figure 2. Food/water intake following euflammation and single bolus E.coli administrations.

Mice were treated with PBS all days, 3d-EU, or PBS on days 1 and 2 followed by a single bolus injection of 100×107 E.coli on day 3. Food (A&B) and water (C&D) intake was measured 5 (A&C) and 24 (B&D) hours following each days injection time point. Bars represent group means ± SEM. † represents significant food and water intake differences on day 2 compared to day 1 (p’s≤0.05). * represents significant food and water intake differences on day 3 compared to day 1 (p’s≤0.05).

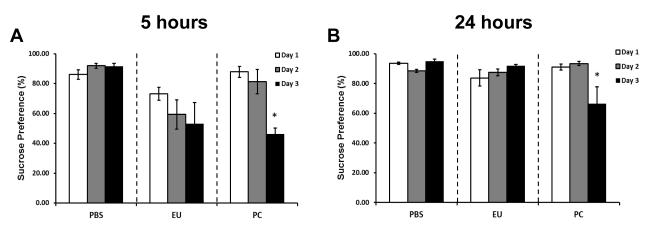

Figure 3. Sucrose preference following euflammation and single bolus E.coli administrations.

Mice were treated with PBS all days, 3d-EU, or PBS on days 1 and 2 followed by a single bolus injection of 100×107 E.coli on day 3. Sucrose preference was measured 5 (A) and 24 (B) hours following each day’s injection time point. Bars represent group means ± SEM. * represents significant sucrose preference differences on day 3 compared to day 1 and 2 for each time point (p’s≤0.05).

2.3.3. Experiment 3: Phenotypic alterations in CD11b+ cells inside and outside of the EIL

To examine changes in the activation phenotype of myeloid cells that euflammation may cause, CD11b+ cells inside and outside of the EIL were examined by flow cytometry for their activation status in 2 groups animals given PBS or 3d-EU (n=6-7/group). Peritoneal cells inside the EIL, and blood and spleens outside the EIL, were harvested 24 hours following the last round of injections. Cells were first identified for their CD11b positivity, then activation status was further determined based on MHCII, TLR4, and CD86 expression.

2.3.4. Experiment 4: qRT-PCR analyses of IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα, and IL-10 mRNA levels in leukocytes, inside and outside of the EIL

To examine if differential cytokine mRNA expression was apparent between leukocytes inside and outside EIL, leukocytes from the peritoneal cavity and blood were harvested and isolated from 3d-EU and PBS-treated control animals (n=5-7/group). Following extraction, cells were stimulated ex vivo with 10 ng/ml of LPS or endotoxin-free media and subsequently analyzed for mRNA expression of IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα, and IL-10. These experiments were conducted to support flow cytometric data.

2.3.5. Experiment 5: Peritoneal macrophage phagocytic potential following 1d-EU and 3d-EU

To determine possible functional changes that euflammation may have on macrophage phagocytic capabilities inside the EIL, 1d-EU, 3d-EU, and PBS-treated control mice (n=5/group) peritoneal macrophages were assessed for the number of total cells per condition, and their ability to phagocytize GFP+ E. coli. The number of bacteria engulfed by each peritoneal macrophage and their phagocytic index was calculated.

2.3.6. Experiment 6: Open field activity and airpouch bactericidal activity following 3d-EU and bolus subcutaneous air pouch E.coli administration

Further in vivo experiments were conducted to examine additional possible functional consequences of euflammation outside the EIL. Two groups of animals were given either 3d-EU or PBS. Twenty-four hrs after the last i.p. injection (i.e., day 4), each group was split into two additional groups (total of 4) and were given 50×107 (n=9-10/group), or 100×107 (n=6/group) airpouch E.coli injections. An additional control group was injected with PBS both in i.p. and intra-airpouch (n=8). Six hrs later, animals were tested for locomoter activity in open field. In addition, air pouches from PBS and 3d-EU animals injected with 100×107 airpouch E.coli were lavaged following behavior and exudates were plated to determine bactericidal activity outside the EIL (n=3/group).

2.3.7. Experiment 7: Serum levels of corticosterone following 3d-EU induction and single bolus E.coli administration

To examine potential alterations in HPA-axis reactivity due to euflammation, four groups of animals received PBS, 3d-EU animals, a single injection of 25×107, or 100×107 of E.coli (n=4/group). Two and eight hrs following the final injection, serum corticosterone levels were examined in all mice by ELISA.

2.4. Open Field

Sickness/motor deficits were determined by using open field apparatus as previously described (Chen et al., 2013; Tarr et al., 2012). The open field apparatus consisted of an opaque 40×40×25 cm Plexiglas® box divided into a grid pattern. Following experimental treatment, subjects were transported to a separate room where they were placed individually facing the corner of the open field and tested for 5 min. Following testing, the open field boxes were cleaned with H2O and diluted ETOH to reduce odor cues. Experimental subject’s activities were monitored using an automated digital beam break system attached to computer containing an open field software template (Omnitech Electronics, Columbus, OH). Mice were assessed for total distance traveled as a measure of sickness behavior. Mice that display sickness behavior or motor deficits travel less and usually stay in one corner of the open field (i.e., secure location).

2.5. Food/Water Intake and Sucrose Preference Test

To assess potential alterations in dietary and fluid consumption, and anhedonia, food and water intake and the sucrose preference test was measured. These methodologies have been extensively described; however, our adapted versions are as follows.

On day 1, food and water intake analyses began by obtaining an initial weight measurement of both food (g) and water (weight of water bottle plus water in g) at 1200 hrs. In addition, animals were given the first 3d-EU i.p. injection of E.coli. At 1700 hrs both food and water bottles were weighed and recorded. On days 2 and 3 of assessment, the same methodology was used, but instead the second and third 3d-EU injection was administered at 1200 hrs respectively. Control animals received a volume equivalent i.p. injection of 100 μl PBS at each corresponding E.coli injection and positive controls received PBS on day 1 and 2 and 100×107 E.coli the 3rd day. An additional time point was added to assess food and water intake 24 hr following injections (i.e., 1200 hrs the following day) to evaluate any lingering effects that euflammation or acute administration of E.coli had.

In a separate group of animals, a sucrose preference test was administered. Briefly, 2 days prior to sucrose preference data collection (sipper tube acclimation), animals were removed from the vivarium’s automatic watering system and were given 2 sipper tubes attached to 50 ml conical polystyrene tubes containing H2O. This allowed for the habituation to the sipper tubes used in the sucrose preference test. At 1000 hrs on day 1 of data collection, animals were deprived of liquid by removing the sipper tubes. Two hours later (i.e., 1200 hrs) mice were given the first 3d-EU injection or PBS, as well as two bottles containing plain H2O or a 1.5% sucrose solution. At 1700 hrs both bottles were weighed to assess fluid consumption. Both bottles were then filled with fresh H2O and animals were left undisturbed until the next assessment day. An additional time point was added to assess sucrose preference 24 hr following injections (i.e., 1200 hrs the following day) to evaluate any lingering effects that euflammation or acute administration of E.coli had. These procedures were repeated 2 additional days with all methodologies being the same, except the second and third 3d-EU injections were given on days 2 and 3 respectively. Control animals received a volume equivalent i.p. injection of 100 μl PBS at each corresponding E.coli injection and positive controls received PBS on day 1 and 2 and 100×107 E.coli the 3rd day. Bottles were alternated each day to avoid any learning/directional preference of the tube containing the sucrose solution.

2.6. Cell Isolation and Flow Cytometry

Twenty-four hours following the last injection time point, animals were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation and peritoneal cells, blood, and splenic tissues were removed, isolated, stained, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Whole blood was collected by cardiac heart puncture using 50 mM EDTA lined syringes and red blood cells (RBC) were then lysed in 1 ml/sample of room temperature RBC lysis buffer (0.16 M NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, and 0.13 mM EDTA) for 2.5 min. To obtain peritoneal cells, a 1 cm sub-diaphragmatic incision was made and the peritoneal cavity was washed and lavaged with 2 ml of sterile Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) following gentle agitation/massage. Spleens were removed and placed directly into 5 ml of HBSS. Following mechanical disruption of splenic tissue using a Model 80 Biomaster Stomacher (Seward, Riverview, FL), homogenized samples were filtered through a 70 μm nylon cell strainer, RBCs lysed, and remaining leukocytes were resuspended in FACS buffer (2% FBS in HBSS and 1 μg/ml sodium azide) until flow analyses began. Final cell counts were obtained using a Beckman Z2 Coulter Counter (Corixa, Seattle, WA). All solutions and tissue were kept on ice for the duration of extraction and processing.

To prevent non-specific binding, single cell suspensions of peritoneal cells, spleens, and blood were incubated in Fc-receptor block (i.e., anti-CD16/CD32; eBioscience, San Diego, CA) for 10 min. Each sample (i.e., 5×105 cells) was then incubated in 1 μl each of the appropriate fluorescently-labeled monocolonal antibodies (i.e., anti-CD11b, anti-CD86, anti-MHCII, anti-TLR4) or isotype control for 45 min. Following incubation, cells were washed and resuspended in FACS buffer until further analyses. Receptor expression was examined using a Becton-Dickinson FACSCaliber (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) four color cytometer and a total of 10,000 events were collected. Data analyses were performed using FlowJo software (Treestar; Ashland, OR) and nonspecific binding was gated on and eliminated by using nonspecific isotype-matched control antibodies.

2.7. RNA Isolation and qRT-PCR

To evaluate potential treatment-induced alterations in cytokine profiles, mRNA levels were determined in LPS stimulated peritoneal and blood leukocytes from experimental and control animals. Three hrs after the last injection time point, peritoneal cells were extracted similarly to methodology in Section 2.6, however, PBS was used instead of HBSS. In addition, whole blood was collected by cardiac puncture, RBCs were lysed, and remaining leukocytes were then washed using PBS. Peritoneal and blood leukocytes were then incubated in endotoxin free Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; 10% FBS, 5000 U/ml penicillin, 5000 μg/ml streptomycin) culture media supplemented with 10 ng/ml of LPS for 1 hr at 37 °C. Following LPS stimulation, cells were washed to remove the remaining endotoxin and then mechanically disrupted by sonication. Total RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent methodology (Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA) per manufacture’s protocol. Total RNA concentration and purity was determined by Nanodrop spectrophotometry (Denville; S. Plainfield, NJ) and subsequently reversed transcribed to cDNA using a Reverse Transcription Kit (Promega; Madison, WI). qRT-PCR was performed using Assay-on-Demand Gene Expression protocol as previously described (Tarr et al., 2011). The amount of specific mRNA present was determined by TaqMan™ probe and primer chemistry (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA) designed to specifically bind to reverse-transcribed genes of interest (i.e., IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα, and IL-10) and endogenous control (i.e., primer limited glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; GAPDH) cDNA. Fluorescence was determined on an ABI 7500 Real Time PCR Thermal Cycling system (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA). Data were analyzed using the comparative threshold cycle (Ct) method (i.e., 2−ΔΔCT) and results are expressed as fold difference from GAPDH normalized PBS treated controls (i.e., unstimulated, non-euflammatory animals) for each specific tissue type.

2.8. Total Peritoneal Cell Counts and Peritoneal Macrophage Phagocytosis Assay

Twenty-four hrs following the last corresponding euflammation injection, experimental and control animals were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation. Peritoneal cells were extracted by using 2.5 mls of DMEM culture media (described previously) to flush the peritoneal cavity of its contents. Peritoneal cells were spun down and resuspended in 500 μl of RBC lysis buffer for 2 min, washed, and resuspended DMEM culture media. Total peritoneal cells were counted and 1.0×106 cells were placed onto a sterile glass slide and the boundary of the media containing the cells was enclosed using a PAP pen. Slides containing cells were incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 2 hrs to allow for the attachment of adherent cells (i.e., primarily peritoneal macrophages). Following incubation, non-adherent cells were removed by gentle washing with 37 °C sterile PBS. One ml of DMEM media supplemented with 5% mouse serum (used to opsonize bacteria) and 10×107 GFP+ E.coli was added to glass slides containing adherent macrophages and incubated at 37 °C for 40 min. Cells were then washed with 37 °C sterile PBS 2X to remove extracellular E.coli, then incubated in 1 ml DMEM culture media containing 50 mg/ml gentamicin for 15 min at 37 °C to kill any remaining extracellular E.coli. Cells were subsequently washed and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. Slides were cover-slipped (Vectashield; Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA) and macrophages were examined at 20X magnification with a Leica DM 5000B microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc.; Buffalo Grove, IL) for their phagocytic activity. In all groups, the numbers of GFP+ E.coli per cell were counted (~40 macrophages) and phagocytic index for each treatment group was calculated using the following formula:

2.9. Airpouch E.coli Administration and Bactericidal Assay

Prior to E.coli subcutaneous (s.c.) infectious challenge, experimental and control animals were given a dorsal air pouch. Briefly, on day 1 mice were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane and a 1 cm2 area of their back was shaved. Subsequently, 1.5 ml of filtered air was injected s.c. using a 26 ½ gauge needle. On days 2 and 3, air pouches were maintained by injecting 0.5 ml of filtered air. This was to make sure that there was no shrinking of the pocket. Three day experimental treatments were started in conjunction with the administration and maintenance of the airpouch. On day 4 animals received intra-airpouch injections of GFP+ E.coli suspended in 100 μl of PBS. Control animals received a volume equivalent of PBS in both the peritoneal cavity and airpouch. Six hrs following the airpouch injection, open field activity was evaluated.

Additionally, after assessment of behavior, animals receiving 100×107 CFUs of E.coli, 1 ml ddH2O was used to flush the airpouch followed by gentle massage. Lavage contents (i.e., cells and left over E.coli) were removed via syringe and diluted in Luria-Bertani (LB) agar containing antibiotic (20 μg/ml chloramphenicol in 6 mls agar). Samples were mixed well and poured into sterile 60 mm culture dishes. Bacteria cultures were incubated at 37 °C for 24 hrs and then bacterial colonies were counted. Data are represented in colony forming units (CFUs) to assess differences between treatment groups.

2.10. Corticosterone ELISA

Experimental and control injections were given at 1000 hrs each day. Two hrs following the last injection (i.e., 1200 hrs), 100 μls of whole blood was obtained by placement of a glass Pasteur pipette into the retro-orbital eye socket. This procedure was then repeated in a separate group of animals 8 hrs (i.e., 1800 hrs) following injections. Blood was then centrifuged 6000 RPM for 15 min at 4 °C to obtain serum. To determine corticosterone levels, a standard sandwich ELISA kit was used and protocols were followed as per manufacture’s protocol (Abcam; Cambridge, MA).

2.11. Statistical Procedures

Standard one-way ANOVAs were used to analyze data obtained from the time course study, where Time point was used as the between-subject variable. In addition, standard one-way ANOVAs were used to analyze data from food and water intake, and sucrose preference tests, where Day was used as the between subject variable for each of the treatment conditions (i.e., PBS, euflammation, and positive control). For flow cytometry, phagocytosis, open field, and bactericidal experiments after s.c. airpouch E.coli injections, standard one-way ANOVAs were used to analyze data and Euflammation Treatment was used as the between subjects variable. qRT-PCR data was analyzed using standard two-way ANOVAs with Euflammation Treatment and LPS Treatment as the between subject variables. Lastly, data from corticosterone experiments were analyzed using standard one-way ANOVAs and E.coli Treatment was used as the between subject variable. When appropriate, significant main and interaction effects were subjected to Fisher’s PLSD post hoc analyses for further comparison and to protect against type 1 errors when multiple comparisons were made (i.e., the ominous F-value was significant before comparisons were made). A two tailed alpha level of p≤0.05 was used as the criterion for the rejection of the null hypothesis. All data were analyzed using StatView statistical software (SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC). Results are reported as treatment means ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

3. RESULTS

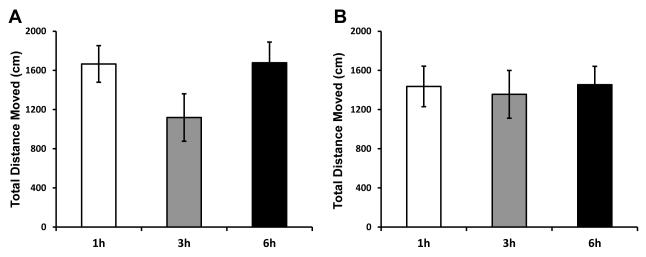

3.1. Maximal sickness behavior response time point was not altered by progressive euflammatory doses

First, to address the time for maximal sickness response, animals were given an acute i.p. injection of E.coli and were tested in the open field 1, 3, and 6 hrs post injection. Results indicate following E.coli injection there was a trend for a main effect of Time point (F(2,27)=2.21; p=0.13; Fig. 1A) for the total distance moved in the open field, however animals did show the greatest reduction in locomotor activity 3 hrs following infection compared to the 1 and 6 hr time point.

Figure 1. Time-course assessment of sickness behavior following a single bolus injection of E.coli or euflammation.

Mice were treated with a (A) single injection of 25×107 E.coli or (B) 3d-EU were tested for total distance moved in the open field 1, 3, or 6 hrs following their last injection. Bars represent group means ± SEM.

As a follow-up study, animals were given 3d-EU and tested in the open field to see whether progressive euflammatory doses altered the maximal sickness behavior response. Results show there was no main effect of Time point (F(2,22)=0.23; p=0.80; Fig. 1B) on the total distance moved in the open field. Although not significant, there was a minimal decrease in the total distance moved in the open field when animals were tested 3 hrs after E.coli injections.

3.2. Progressive euflammatory doses cause transient anorexia, adipsia, and anhedonia, but recovery is faster compared to animals given E.coli acutely

To assess additional other beneficial effects progressive euflammatory doses have on sickness behavioral measures other than decreased locomoter activity (Chen et al., 2013), food/water intake, as well as sucrose preference intake, was measured 5 and 24 hrs following the injection time point. Results show there was no main effect of Day in PBS treated animals for food (F(2,6)=0.05; p=0.95; Fig. 2A) or water (F(2,6)=0.58; p=0.59; Fig. 2C) intake at the 5 hr measurement time point. However, euflammatory animals showed significant main effects of Day for both food and water intake (F(2,6)=14.55; p≤0.005; F(2,6)=6.09; p≤0.05; respectively; Fig. 2A & C). Fisher’s PLSD post hoc analyses revealed that animals 5 hrs after receiving day 2′s euflammatory injection differed significantly from animals’ food (p≤0.01) and water (p≤0.05) intake 5 hrs following day 1 injections. These effects remained significant when comparing day 3′s assessment time point with day 1′s for both food and water intake (p’s≤0.05). These data indicate euflammatory E.coli injections induced sickness behavior, evidenced by decreased food and water consumption after the second and third euflammatory injection. There were no significant differences comparing day 2 and 3 assessment time point’s in euflammatory animals. Upon examination of animals that received a bolus injection of 100×107 E.coli on day 3 only (our positive control sickness behavior group), results show a significant main effect of Day for both food (F(2,6)=69.33; p≤0.0001; Fig. 2A) and water (F(2,6)=13.87; p≤0.01; Fig. 2C) intake 5 hrs following injections. As expected, Fisher’s PLSD showed that animals had a reduction in food intake following acute E.coli challenge on day 3 compared to both day 1 and 2′s PBS injections (p’s≤0.0001). These results were mirrored when assessing water intake (p’s≤0.01), revealing that our acute 100×107 E.coli injection induced robust sickness behavior. There were no differences between day 1 and day 2′s PBS treatments.

When examining food and water intake data 24 hrs following day 1, 2, and 3′s injection, interesting results emerged. Not surprising, data show, as in the 5 hr post PBS treatment time points, there were no significant main effects of Day for either food (F(2,6)=2.87; p=0.13; Fig. 2B) or water (F(2,6)=2.19; p=0.19; Fig. 2D) intake 24 hrs after PBS injections. When examining food and water intake data from animals that received euflammatory injections 24 hrs prior, results showed that there was a main effect of Day for food intake (F(2,6)=46.57; p≤0.0005; Fig. 2B); however, interestingly the main effect on water intake went away between the 5 hr assessment and 24 hr assessment time points (F(2,6)=2.64; p=0.15; Fig. 2D). Fisher’s PLSD post hoc analyses revealed that animals 24 hrs after receiving day 3′s euflammatory injection significantly differed in food intake compared to euflammatory animals 24 hrs after days 1 and 2 assessment (p’s≤0.0005). These data show that 24 hrs after the last injection was enough time to reduce the euflammatory-induced impact on food and water intake. Lastly, when looking at food and water intake in the animals 24 hrs after receiving an acute injection of E.coli, data revealed significant main effects of Day for food (F(2,6)=194.41; p≤0.0001; Fig. 2B) and water (F(2,6)=156.98; p≤0.0001; Fig. 2D) intake. Fisher’s PLSD post hoc analyses revealed, as in the 5 hr assessment time point, animals 24 hr post-acute 100×107 E.coli injection on day 3′s time point differed significantly from day 1 and 2′s 24 hr post PBS injection time points for both food and water intake (p’s≤0.0001), indicating that for both food and water intake, acute E.coli treated animals maintained decreased consumption 24 hrs after injections

Data show in the sucrose preference test there was no significant main effect of Day for PBS or euflammation treated animals for the percentage of sucrose solution consumed at the 5 hr time point (F(2,12)=1.80; p=0.21; (F(2,12)=0.99; p=0.40; respectively; Fig. 3A). However in the animals that received an acute single dose of 100×107 E.coli, there was a significant main effect of Day for the percentage of sucrose solution consumed at the 5 hr time point (F(2,12)=15.86; p≤0.001; Fig. 3A). Although there was no main effect of Day, there was an overall reduction in sucrose preference compared to the PBS treated animals, similar to the positive control at the 5 hr time point. Fisher’s PLSD post hoc analyses revealed that animals receiving an acute dose 100×107 E.coli on day 3 differed significantly compared to day 1 and 2′s assessment of sucrose consumption following PBS injections at the 5 hr time point (p’s≤0.005), indicating that E.coli at this dose level was able to induce anhedonia in the sucrose preference test 5 hrs after E.coli injections.

The 24 hr results for the sucrose preference test indicate a significant main effect of Day for PBS F(2,12)=10.57; p<0.005; Fig. 3B) for the percentage of sucrose solution consumed at the 24 hr time point, however, the euflammation treated animals was not significant at this time point (F(2,9)=0.99; p=0.23; Fig. 3B). There were no statistical differences between PBS and euflammatory animals. However, in the animals that received an acute single dose of 100×107 E.coli, there was a significant main effect of Day for the percentage of sucrose solution consumed at the 24 hr time point (F(2,9)=9.18; p≤0.01; Fig. 3B). Fisher’s PLSD post hoc analyses revealed that animals receiving an acute dose 100×107 E.coli on day 3 differed significantly compared to day 1 and 2′s assessment of sucrose consumption following PBS injections at the 24 hr time point (p’s≤0.01), indicating that E.coli at this dose level was able to induce anhedonia in the sucrose preference test 24 hrs after E.coli injections.

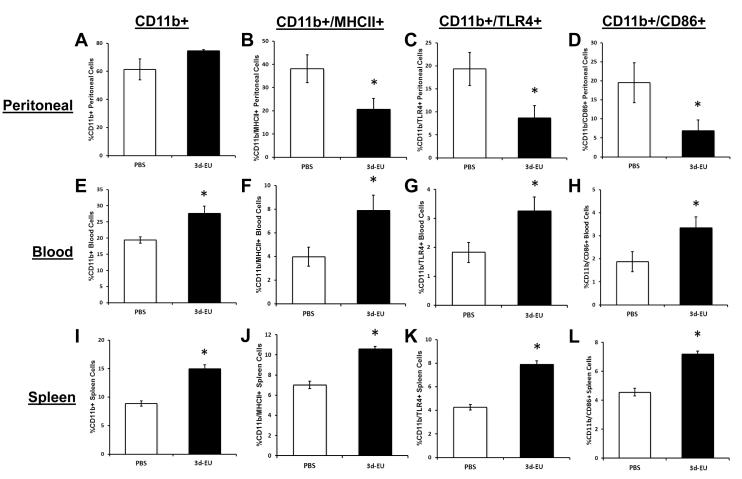

3.3. Progressive euflammatory doses decrease the activation status of CD11b+ cells inside the EIL and increase the activation status of CD11b+ cells outside the EIL

To evaluate if there were any differential effects that progressive euflammatory doses have on CD11b+ cells activation status inside and outside the EIL, blood, spleen and peritoneal leukocytes were taken from 3d-EU and PBS treated animals and were evaluated by flow cytometry. Flow cytometric analyses of cells obtained from the peritoneal cavity (inside EIL) show a trend for main effect of Euflammation Treatment on the percent CD11b+ cells (F(1,11)=3.72; p=0.08; Fig. 4A), although there was a trend that the 3d-EU animals having a greater number of CD11b+ cells compared to controls. However, after examination of activation markers on CD11b+ cells, significant main effects of Euflammation Treatment were found where CD11b+/MHCII+ (F(1,11)=5.35; p≤0.05; Fig. 4B), CD11b+/TLR4+ (F(1,11)=5.79; p≤0.05; Fig. 4C), and CD11b+/CD86+ (F(1,11)=4.87; p≤0.05; Fig. 4D) peritoneal cells were decreased in 3d-EU animals compared to PBS-treated controls.

Figure 4. Phenotypic alterations in CD11b+ cells inside and outside of the euflammatory induction locus.

Mice were treated with PBS all days or 3d-EU. Twenty-four hours following the last injection, percent CD11b+, CD11b+/MHCII+, CD11b+/TLR4+, and CD11b+/CD86+ cells were measured in peritoneal (A-D), blood (E-H), and splenic (I-L) cells. Bars represent group means ± SEM. * represents significant difference between 3d-EU and PBS-treated animals (p’s≤0.05).

Flow cytometric results for blood leukocytes (outside EIL) indicated significant main effects of Euflammation Treatment on the percentage of CD11b+ (F(1,10)=11.76; p≤0.01; Fig. 4E), CD11b+/MHCII+ (F(1,10)=6.71; p≤0.05; Fig. 4F), CD11b+/TLR4+ (F(1,10)=5.70; p≤0.05; Fig. 4G), and CD11b+/CD86+ (F(1,11)=5.15; p≤0.05; Fig. 4H), showing that 3d-EU increased the percentage and activation status of CD11b+ in the blood. Flow results for splenic leukocytes (outside EIL) showed, as it was in the blood, significant main effects of Euflammation Treatment on the percentage of CD11b+ (F(1,12)=230.05; p≤0.0001; Fig. 4I), CD11b+/MHCII+ (F(1,12)=67.08; p≤0.0001; Fig. 4J), CD11b+/TLR4+ (F(1,12)=88.58; p≤0.0001; Fig. 4K), and CD11b+/CD86+ (F(1,12)=59.97; p≤0.0001; Fig. 4L) derived splenocytes, showing that 3d-EU increased the percentage and activation status of CD11b+ in the spleen.

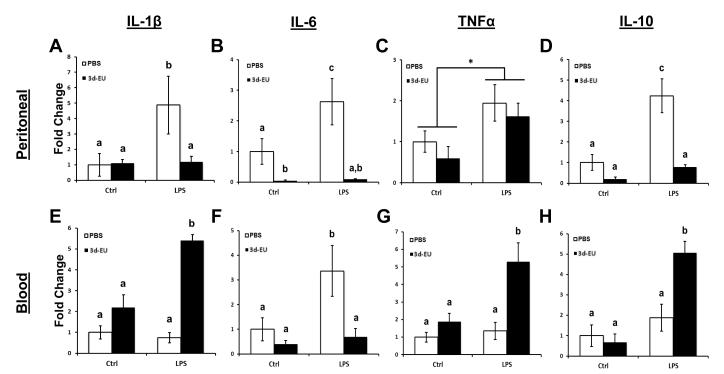

3.4. Progressive euflammatory doses decrease leukocyte cytokine mRNA expression inside the EIL and increase leukocyte cytokine mRNA expression outside the EIL following LPS stimulation

To assess whether euflammation altered cytokine mRNA expression upon stimulation, inside and outside the EIL, 3d-EU and PBS treated animal’s peritoneal and blood leukocytes were removed and stimulated with LPS. Results show a significant main effect of LPS Treatment (F(1,15)=9.48; p≤0.01; Fig. 5A) and Euflammation Treatment (F(1,15)=9.91; p≤0.01; Fig. 5A) for IL-1β, indicating that LPS treatment significantly increased and 3d-EU significantly decreased IL-1β mRNA expression in peritoneal leukocytes (i.e., inside EIL) compared to their respective controls. Additionally, a significant LPS Treatment × Euflammation Treatment interaction was apparent (F(1,15)=7.51; p≤0.05; Fig. 5A). Fisher’s PLSD post hoc analyses revealed LPS stimulated peritoneal leukocytes from non-euflammatory animals had a significant increase in IL-1β mRNA expression compared to cells from PBS and 3d-EU animals receiving just media (p’s≤0.05). Interestingly, 3d-EU animals’ peritoneal leukocytes that received LPS stimulation had a significant reduction in IL-1β mRNA expression compared to the non-euflammatory animal cells receiving LPS (p≤0.01).

Figure 5. qRT-PCR analyses of IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα, and IL-10 mRNA levels in leukocytes, inside and outside of the euflammatory induction locus.

Mice were treated with PBS all days or 3d-EU. Three hours following the last injection time point, peritoneal and blood leukocytes were isolated and incubated with 10 ng/ml of LPS. After stimulation, cells were processed for mRNA quantification of IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα, and IL-10 in peritoneal (A-D) and blood leukocytes (E-H). Bars represent group means ± SEM. Means with different letters (a, b, c) are significantly different from one another (p’s≤0.05). * represents a main effect of LPS Treatment regardless of euflammation treatment.

As for IL-6 mRNA expression in peritoneal cells, data showed significant main effect of LPS Treatment (F(1,17)=8.89; p≤0.01; Fig. 5B) and Euflammatory Treatment (F(1,17)=42.03; p≤0.0001; Fig. 5B), where once again LPS stimulation increased and 3d-EU decreased expression of IL-6 mRNA in peritoneal leukocytes compared to their respective controls. Furthermore, data showed a significant LPS Treatment × Euflammation Treatment interaction effect (F(1,17)=10.27; p≤0.005; Fig. 5B) for IL-6 mRNA expression in peritoneal leukocytes. Fisher’s PLSD post hoc analyses indicated that, as it was for IL-1β mRNA, LPS stimulated peritoneal leukocytes from non- euflammatory animals had a significant increase in IL-6 mRNA expression compared to cells from PBS and 3d-EU animals receiving just media (p’s≤0.05). Furthermore, peritoneal leukocytes from 3d-EU animals receiving media stimulation had a significant decrease in IL-6 mRNA expression compared to media stimulated non-euflammatory control cells (p≤0.05). Additionally, peritoneal leukocytes from 3d-EU animals stimulated with LPS had a significant reduction in IL-6 mRNA expression compared to cells from non-euflammatory control animals receiving LPS (p≤0.001).

Examination of TNFα mRNA expression in peritoneal leukocytes revealed a significant main effect of LPS Treatment (F(1,19)=8.12; p≤0.01; Fig. 5C) where LPS-treated peritoneal leukocytes had an increased mRNA expression compared to media-treated control cells. There were no main effects of Euflammation Treatment or LPS Treatment × Euflammation Treatment interaction effects on TNFα mRNA expression.

Lastly, IL-10 mRNA expression was examined in peritoneal leukocytes from PBS and 3d-EU treated animals. Results showed significant main effects of LPS Treatment (F(1,22)=18.73; p≤0.0005; Fig. 5D) and Euflammation Treatment (F(1,22)=33.09; p≤0.0001; Fig. 5D) for IL-10, indicating that LPS treatment significantly increased and 3d-EU significantly decreased IL-10 mRNA expression in peritoneal leukocytes compared to their respective control cells. Furthermore, data indicated a significant LPS Treatment × Euflammation Treatment interaction effect (F(1,22)=11.66; p≤0.005; Fig. 5D). Fisher’s PLSD post hoc analyses revealed, as it was for IL-1β and IL-6 mRNA, peritoneal leukocytes from non-euflammatory animals stimulated with LPS had a significant increase in IL-10 mRNA expression compared to PBS and 3d-EU animals’ peritoneal leukocytes receiving just media (p’s≤0.01). Moreover, LPS stimulated peritoneal leukocytes from 3d-EU animals had a significant reduction compared to non-euflammatory peritoneal leukocytes receiving LPS (p≤0.0001).

Results from qRT-PCR IL-1β mRNA expression in blood derived leukocytes showed a significant main effect of LPS Treatment (F(1,17)=6.11; p≤0.05; Fig. 5E), indicating that LPS treatment significantly increased IL-1β mRNA expression compared to media treatment in blood leukocytes (i.e., outside EIL). Additionally, there was a significant main effect of Euflammation Treatment (F(1,17)=33.62; p≤0.0001; Fig. 5E), showing that 3d-EU significantly increased IL-1β mRNA expression compared to non-euflammatory controls in blood leukocytes (opposite of peritoneal leukocytes in the EIL). Moreover, data showed a significant LPS Treatment × Euflammation Treatment interaction effect (F(1,17)=9.00; p≤0.01; Fig. 5E). Fisher’s PLSD post hoc analyses revealed LPS stimulated blood leukocytes from 3d-EU animals had a significant increase in IL-1β mRNA compared to all other groups (p’s≤0.05). No other groups differed.

Somewhat surprising, expression of IL-6 mRNA did not follow a similar pattern as IL-1β, but rather expression looked similar to IL-6 mRNA expression in peritoneal leukocytes. Results showed significant main effect of LPS Treatment (F(1,17)=9.78; p≤0.01; Fig. 5F) and Euflammatory Treatment (F(1,17)=12.66; p≤0.005; Fig. 5F), where LPS treatment increased and 3d-EU decreased expression of IL-6 mRNA in blood leukocytes. Moreover, data showed a significant LPS Treatment × Euflammation Treatment interaction effect (F(1,17)=5.02; p≤0.05; Fig. 5F) in blood leukocytes. Fisher’s PLSD post hoc analyses revealed blood leukocytes from non-euflammatory animals stimulated with LPS had a significant increase in IL-6 compared to all other groups (p’s≤0.05). No other differences between groups were found.

Similar to IL-1β mRNA expression in blood leukocytes, data revealed significant main effects of LPS Treatment (F(1,19)=8.81; p≤0.01; Fig. 5G) and Euflammation Treatment (F(1,19)=10.94; p≤0.005; Fig. 5G) for TNFα, indicating that LPS and 3d-EU treatment significantly increased TNFα mRNA expression compared to controls in blood leukocytes. Additionally, a significant LPS Treatment × Euflammation Treatment interaction was apparent (F(1,19)=4.30; p≤0.05; Fig. 5G). Fisher’s PLSD post hoc analyses revealed LPS stimulated blood leukocytes from 3d-EU animals had a significant increase in TNFα mRNA expression compared to all other groups (p’s≤0.05). No other groups differed. Finally, IL-10 mRNA was assessed in blood leukocytes.

Comparable to IL-1β and TNFα mRNA expression in the blood, data revealed a significant main effect of LPS Treatment (F(1,20)=5.73; p≤0.05; Fig. 5H) and a trending Euflammation Treatment effect (F(1,20)=1.52; p=0.23; Fig. 5H) for IL-10, where LPS and 3d-EU treatment increased IL-10 mRNA expression compared to their respective controls in blood leukocytes. Additionally, a significant LPS Treatment × Euflammation Treatment effect was apparent (F(1,20)=4.30; p≤0.05; Fig. 5H). Fisher’s PLSD post hoc analyses revealed LPS stimulated blood leukocytes from 3d-EU animals had a significant increase in IL-10 mRNA compared to all other groups (p’s≤0.05). No other groups differed.

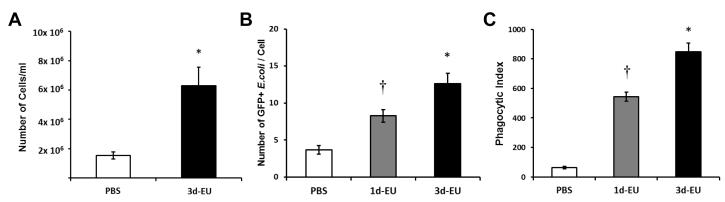

3.5. Progressive euflammatory doses peritoneal macrophage number and phagocytic activity inside the EIL

To assess phagocytic capabilities of peritoneal macrophages inside the EIL, cells were extracted from 1d-EU, 3d-EU, and PBS treated animals and were cultured ex vivo with GFP+ E.coli. First, data revealed there was a significant main effect of Euflammation Treatment for the number of cells per ml in the peritoneal cavity (F(1,8)=14.02; p≤0.01; Fig. 6A), showing euflammation-treated animals had a significantly greater number of total peritoneal cells than PBS-treated controls. Furthermore, when examining peritoneal macrophages following GFP+ E.coli stimulation, data showed a main effect of Euflammation Treatment (F(2,111)=19.45; p≤0.0001; Fig. 6B) on the number of GFP+ E.coli engulfed by each macrophage. Fisher’s PLSD post hoc analyses revealed peritoneal macrophages from 1d-EU animals had a significantly increased number of GFP+ E.coli compared to PBS-treated controls and a significantly decreased number of GFP+ E.coli compared to 3d-EU animals (p’s≤0.005). Additionally, a significant increase in the number of phagocytized GFP+ E.coli was found in 3d-EU animals compared to PBS controls (p≤0.0001). Lastly, a main effect of Euflammation Treatment (F(2,42)=41.50; p≤0.001; Fig. 6C) on the phagocytic index was evident. Fisher’s PLSD post hoc analyses revealed, similar to the number of GFP+ E.coli per cell, 1d-EU animals differed significantly compared to 3d-EU or PBS controls (p’s≤0.0001). Moreover, significant differences were found between 3d-EU animals and PBS controls (p≤0.0001).

Figure 6. Peritoneal macrophage phagocytic potential following euflammation.

Mice were treated with PBS all days, 1d-EU, or 3d-EU. Twenty-four hrs after the last injection animals were euthanized and peritoneal macrophages were harvested by lavage. Cells were then placed on glass slides, incubated with 10×107 GFP+ E.coli, and assessed for overall appearance of phagocytic capabilities. The total number of peritoneal cells per ml following PBS all days or 3d-EU (A), along with the number of GFP+ E.coli per cell (B), and phagocytic index (C) following PBS all days, 1d-EU, or 3d-EU was assessed. Bars represent group means ± SEM. † represents significant differences between 1d-EU and all other groups (p’s≤0.05). * represents significant differences between 3d-EU and all other groups (p’s≤0.05).

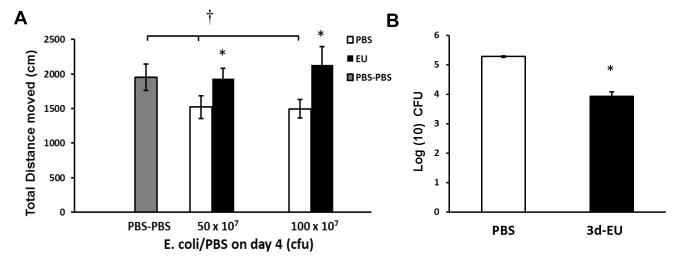

3.6. Progressive euflammatory doses attenuate locomoter deficits and increases bactericidal activity following intra-airpouch E.coli administration outside the EIL

Assessment of the potential amelioration of airpouch-induced (outside EIL) sickness behavior and bactericidal effects were investigated in 3d-EU animals. As expected, there was a significant main effect of E.coli Treatment (F(2,20)=4.47; p≤0.05; Fig. 7A) on the total distance moved in the open field, indicating that intra-airpouch injections of E.coli overall induced locomoter deficits in the open field. Fisher’s PLSD post hoc analyses revealed, animals given intra-airpouch injections of 50×107 or 100×107 E.coli after PBS i.p., had significant reductions in the total distance moved compared to animals receiving PBS i.p. and intra-airpouch (p’s≤0.05). In addition, results indicated a significant main effect of Euflammation Treatment on the total distance moved in animals receiving airpouch injections of both 50×107 (F(1,17)=5.72; p≤0.05; Fig. 7A) and 100×107 E.coli (F(1,10)=4.96; p≤0.05; Fig. 7A), showing that 3d-EU blocked peripheral E.coli-induced locomoter deficits in open field at these dose levels. Furthermore, analysis of intra-airpouch bactericidal activity revealed a significant main effect of Euflammation Treatment (F(1,4)=81.01; p≤0.001; Fig. 7B), where 3d-EU-treated animals had a decreased number of bacterial colonies 6 hrs after receiving 100×107 E.coli intra-airpouch injections compared to PBS-treated controls.

Figure 7. Open field activity and bactericidal activity following intraperitoneal euflammation induction and bolus subcutaneous air pouch E.coli administration.

Mice were treated with PBS all days or 3d-EU. Twenty-four hrs later, intra-air pouch injections of PBS, 50×107 or 100×107 CFUs of E.coli were given. Six hrs following airpouch injections, animals were assessed for open field activity (A). In addition, airpouch lavage samples were taken from both PBS-treated and 3d-EU animals and assessed for bactericidal activity 24 hrs after plating (B). Bars represent group means ± SEM. † represents significant differences between PBS-PBS treated animals and animals that received i.p. PBS injections followed by intra-airpouch injections of 50×107 and 100×107 CFUs of E.coli (p’s≤0.05). * represents significant differences between euflammation and PBS-treated animals (p’s≤0.05).

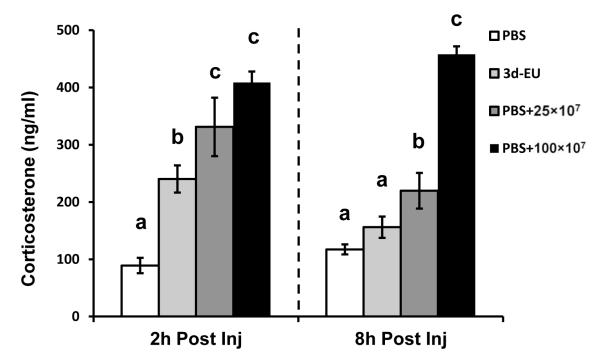

3.7. Progressive euflammatory doses attenuate serum corticosterone production 2 and 8 hrs post injection compared to animals given E.coli acutely

The possible amelioration of HPA-axis reactivity by progressive euflammatory doses was measured 2 and 8 hrs following the last treatment injection. Results showed that 2 hrs post injection there was a significant main effect of E.coli Treatment (F(3,12)=20.21; p≤0.0001; Fig. 8). Fisher’s PLSD post hoc analyses revealed that 2 hrs post injection, 3d-EU animals had a significant increase in the amount of corticosterone compared to PBS animals (p≤0.0005); however, it was significantly less than animals that received a single injection of 25×107 or 100×107 of E.coli (p’s≤0.05). Additionally, as predicted, animals receiving either dose of acute E.coli had an increase in corticosterone compared to PBS animals (p’s≤0.001). Results for corticosterone concentrations 8 hrs following injection also showed a significant main effect of E.coli Treatment (F(3,12)=59.91; p≤0.001; Fig. 8). Fisher’s PLSD post hoc analyses revealed that 8 hrs post final injection, 3d-EU animals did not have a significant increase in corticosterone compared to PBS controls (p=0.11); however, animals that received a single injection of 25×107 or 100×107 of E.coli did (p’s≤0.0005). In addition, animals receiving 100×107 E.coli had an increased corticosterone level compared to animals receiving 25×107 (p≤0.0001), unlike the 2 hr time point.

Figure 8. Serum levels of corticosterone following euflammation induction and single bolus E.coli administration.

Mice were treated with PBS all days, 3d-EU, or a single bolus injection of 25×107 or 100×107 CFUs of E.coli after 2 days or PBS injections. Mouse serum was assessed for corticosterone levels at 2 and 8 hrs post final injection. Bars represent group means ± SEM. Means with different letters (a, b, c) are significantly different from one another (p’s≤0.05).

4. DISCUSSION

The ability for the immune system to alter its activation kinetics to protect against future insults has been extensively studied. The best understood mechanism is how vaccination can strengthen adaptive immunity. In this regard, prior exposures to a specific non-pathogenic antigen allows the host to produce long-term memory in T and B cells, such that future encounter with the same antigen causes accelerated and amplified defense against the pathogens having the same antigen (Watson and Viner, 2011). Different from adaptive immunity, innate immune responses are typically stimulated by pathogen-associated molecular pattern molecules (PAMPs) which are some of the common structural molecules on various groups of pathogens. LPS, for example, is one of the PAMPs of the gram negative bacteria. Recent studies have revealed that the innate immune system is also plastic: prior exposure to PAMPs could generate a short-term innate memory (trained immunity) which might last for days to months (Netea, 2013), or it could lead to endotoxin tolerance (Biswas and Lopez-Collazo, 2009). The adaptive value of ET is the prevention of hyper-inflammation which causes tissue damage by reducing the production of inflammatory cytokines in response to the stimulation from PAMPs. A prior activation of the innate immune response by a large, but sub-lethal, dose of LPS is the procedure to generate ET or LPS-preconditioning. It has been shown LPS pre-conditioning can ameliorate subsequent sepsis (Shi et al., 2011), myocardial inflammation (Neviere et al., 1999), cerebral ischemia (Vartanian et al., 2011), excitotoxic brain damage (Orio et al., 2007), hepatic ischemia (Sano et al., 2011), and fever (Ivanov et al., 2000). The drawback of LPS preconditioning is that the LPS pretreatment itself can be harmful because it can cause significant sickness behavior (Kelley et al., 2003) and prolonged detrimental effects to the central nervous system (Qin et al., 2007). Trained immunity, on the other hand, is an adaptive change in innate immunity to enhance its activity against pathogens. Trained immunity is associated with increased activity of the innate immune cells to PAMPs (Locati et al., 2013).

Our previous results showed that low doses of E.coli that does not cause sickness behavior in the open field prior to a higher dose of E.coli, ameliorates the sickness behavior that would otherwise have been caused by high dose E.coli 3 hrs after injection (Chen et al., 2013). These findings led us to investigate whether innate immune system can be trained in this specific manner to more effectively combat a subsequent inflammatory stimulation without the induction of overt sickness behavior. Critical initial experiments were conducted to verify that the 3 hr time point after the i.p. E.coli injection is the peak sickness behavior response time and this peak response time does not shift after animals received multiple i.p. E.coli injections on subsequent days. Indeed, the present results showed that after receiving a single 25×107 E.coli injection, 3 hrs was the time point that the maximal locomotor deficit in the open field occurred. Additionally, it was shown that prior exposure to sub-threshold E.coli for 2 days did not alter or shift the time point of maximal response on the third day (i.e., euflammation ameliorated the sickness response at the 3hr time point and no sickness behavior was apparent at the 1 or 6 hr time point). These data confirm measuring sickness behavior responses 3 hrs post i.p. E.coli injection was the appropriate assessment time point, and the absence of locomotor deficit after the progressive increases in E.coli on subsequent days was not due to a shift in the peak response time.

Beyond overt sickness behavior such as locomotor deficits and piloerection (Chen Q, 2013), which were absent in 3d-EU, peripheral inflammation is known to cause other more subtle sickness behaviors such as anhedonia (Borowski et al., 1998), anorexia (Riediger et al., 2010), and adipsia (Andonova et al., 1998). As a measure of anorexia and adipsia, food and water intake was measured 5 and 24 hrs following either PBS, 3d-EU, or acute E.coli administration. In the current study, food and water consumption in euflammatory animals were significantly decreased after day 2 and 3′s injection at the 5 hr time point, however not to the degree as animals receiving one acute injection without any prior exposure. It is important to note after examination of food/water intake 24 hrs after the last injection, reductions found after 5 hrs in euflammatory animals were completely or largely recovered, whereas animals that received acute E.coli injections still showed a robust decrease in food and water consumption. In the current study the sucrose preference test was used as a measure of anhedonia. Progressive euflammatory injections reduced the overall preference to the sucrose solution compared to control animals; however the progressive increase in doses did not alter consumption between treatment days and was similar to the consumption of animals receiving an acute injection of E.coli. As it was for food and water intake, assessment of sucrose preference at the 24 hr time point showed 3d-EU animals recovered their preference for the sucrose solution, whereas animals that received acute injections had lingering anhedonic behavior. Overall, data from food/water intake and sucrose preference studies show although euflammation causes slight transient non-overt sickness behavior at the 5 hr assessment time point, these effects largely went away 24 hrs later.

One ready explanation for the observed reduction in sickness behavior in euflammatory animals is the possibility that ET was developed after repeated E.coli exposure. Previous studies showed repeated exposure to bacteria or endotoxin causes changes in the phenotype of myeloid cells such that these innate immune cells will respond to subsequent bacterial or endotoxin challenge with reduced production of inflammatory cytokines but increased production of anti-inflammatory cytokines (Biswas and Lopez-Collazo, 2009). In addition, ET myeloid cells typically express reduced innate immune activation markers including MHCII, TLR4 and CD86. We therefore examined whether these phenotypic changes in myeloid cells (CD11b+) occurred in the present study. Indeed, significant reductions in the percentages of CD11b+/MHCII+, CD11b+/TLR4+, and CD11b+/CD86+ cells were found in the peritoneal cavity indicating and ET phenotype (i.e., inside the EIL). Interestingly, the opposite phenotype changes were found in blood and spleen leukocytes (i.e., outside the EIL) showing 3d-EU increased the percentage of CD11b+, CD11b+/MHCII+, CD11b+/TLR4+, and CD11b+/CD86+ cells, indicating a more reactive phenotype might surround the EIL. We then examined ex vivo cytokine response to LPS stimulation in peritoneal and blood leukocytes from control and 3d-EU animals. IL-1β, IL-6, TNFα, and IL-10 mRNA were all up-regulated in non-euflammatory LPS-treated peritoneal cells compared to controls. LPS stimulation failed to induce significant production of IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 mRNA, but induced significant production of TNFα mRNA in peritoneal cells from 3d-EU animals. This pattern of cytokine profile is partially consistent with the ET phenotype because the more typical ET phenotype would show reduced TNFα and increased IL-10 mRNA expression upon LPS challenge (Locati et al., 2013). Examination of cytokine responses in blood leukocytes outside the EIL provides further evidence that euflammation is not simply a model of ET. Blood cells extracted from 3d-EU animals and then stimulated with LPS had increased production of IL-1β, TNFα, and IL-10 mRNA compared to all other groups. Thus, euflammation induction resulted in the elicitation a partial ET phenotype inside EIL along with activated innate immune cells outside the EIL, similarly to a trained immunity phenotype. Interestingly, ex vivo IL-6 induction by LPS in 3d-EU blood cells was significantly reduced. Research has indicated IL-6 is capable of acting as a paracrine hormone, playing an important role as an inducer of neuroinflammation and sickness behavior (Damm et al., 2011). It is possible that diminished IL-6 production in the blood cells also contributed to the absence of overt sickness behavior during euflammation. The differential phenotypic and cytokine production from innate immune cells comparing cells within the EIL and outside the EIL highlight the protective duality of euflammation, ET-like mechanisms and trained immunity respectively. Of note, to confirm that bacteria did not translocate outside the EIL causing these effects, livers, blood, and spleens were extracted from 3d-EU animals, cultured, and examined for bacterial colony formation. Results indicate no bacteria were present in tissues outside the EIL, supporting our notion of a distinct division between compartments (data not shown).

Knowing there are differential phenotypic and cytokine expression changes between leukocytes inside and outside the EIL, we next examined if there were corresponding functional changes after 1d-EU and 3d-EU induction. Along with increased total number of peritoneal cells extracted, data showed a clear increase in the number of phagocytized GFP+ E.coli per cell and this translated into an increased phagocytic index. Moreover, phagocytic capabilities increased in conjunction with the number of euflammatory doses animals received. These increases in phagocytic responses to E.coli administration show similarities to previous ET studies using high dose LPS as a pretreatment (Shi et al., 2011; Wheeler et al., 2008); however, to date these novel results show sub-threshold doses of E.coli are capable of exerting similar effects as ET without the induction of overt sickness behavior.

Examination of the sickness behavior response to E.coli administered outside EIL produced unexpected results. Because innate immune cells outside the EIL displayed an activated phenotype, we thought increased sickness behavior might be evident if E.coli were injected outside EIL. Surprisingly, 3d-EU was able to successfully counteract open field locomotor deficits following a subcutaneous airpouch injection of 50×107 and 100×107 E.coli. In addition, the ability for 3d-EU animals to successfully eliminate bacteria in the airpouch was enhanced compared to PBS-treated animals. It is possible that outside EIL, increased bacterial clearance resulted in rapid removal of inflammagens such that induction of sickness behavior was also minimized. It should be noted that increased bactericidal activity has been demonstrated in both ET leukocytes (tolerant) and trained immune cells (activated) in previous studies. In ET cells, increased expression of CD64 was linked to a more effective phagocytosis (Biswas and Lopez-Collazo, 2009), whereas in trained immunity, increased expression of TLRs were linked with the more efficient bacterial clearance (Locati et al., 2013). In light of the increases of CD11b+/TLR4+ cells in the blood and spleen, it can be reasonably postulated that euflammation causes trained immunity outside the EIL. Thus a global sickness-free state can be maintained in euflammatory animals, although different host defense mechanisms might be employed to defend inflammatory challenges inside and outside EIL.

Lastly, we examined the neuroendocrine aspect of the euflammation. We show 3d-EU does in fact cause a reduction in corticosterone production at the 2 hr time point after injection compared to non-euflammatory animals receiving an acute dose of 25×107 or 100×107 E.coli. Moreover, 3d-EU animals recovered by the 8 hr time point to levels similar to PBS-treated animals, whereas the corticosterone levels in animals receiving the acute doses of E.coli remained elevated compared to both 3d-EU and PBS-treated animals. Therefore, although euflammation induced transient HPA-axis activation, the effect was small and euflammatory animals were able to recover quicker. Taken together with the results from our air pouch study indicating 3d-EU was able to eradicated bacteria better, and the importance of corticosterone mediated behavioral deficits, it is possible that euflammation ameliorated the bacterial challenge-induced signal to the CNS thus causing diminished sickness behaviors. Although this is one possibility, it has yet to be fully explored.

In summary, the current studies provide significant evidence that euflammation can provide protective effects within the EIL through mechanisms similar to ET; however, euflammatory effects outside the EIL were similar to those seen in trained immunity. Overall, euflammation provides a novel and robust global defense to subsequent inflammatory stimuli without inducting overt sickness behavior. Training for stronger innate immunity faces two obstacles: 1) insufficient stimulation strength may not induce activation of innate immune cells to confer future resistance to infectious challenge, whereas over stimulation, such as those used in the induction of ET, might cause initial hyper-inflammation and later immune paralysis (Lin et al., 2007), 2) due to the shorter memory of the innate immune system, training innate immunity may require repeated priming to achieve better outcomes. In this regard, the euflammatory procedure used in the present study could be a very useful innate immune training regimen. By stipulating the euflammatory strength as the maximal dose of E.coli that does not cause overt sickness behavior, both insufficient and over stimulation can be avoided. By the reiterative stimulation process using progressively higher doses (due to the upshift of MEP) of E.coli in the succeeding days, repeated, but escalating induction of high euflammatory states can be efficiently obtained. It is possible this procedure could lead to enhanced innate immune fitness.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in full by the NIH grants: RO1AI-076926 to NQ and College of Dentistry Intramural Seed Grant Program at the Ohio State University to AJT.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement: All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aderem A, Underhill DM. Mechanisms of phagocytosis in macrophages. Annual review of immunology. 1999;17:593–623. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albiger B, Dahlberg S, Henriques-Normark B, Normark S. Role of the innate immune system in host defence against bacterial infections: focus on the Toll-like receptors. Journal of internal medicine. 2007;261:511–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andonova M, Goundasheva D, Georgiev P, Ivanov V. Effects of indomethacin on lipopolysaccharide-induced plasma PGE2 concentrations and clinical pathological disorders in experimental endotoxemia. Veterinary and human toxicology. 1998;40:14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett SV, Clark IA. Inflammatory fatigue and sickness behaviour - lessons for the diagnosis and management of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Affect Disord. 2012;141:130–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas SK, Lopez-Collazo E. Endotoxin tolerance: new mechanisms, molecules and clinical significance. Trends in immunology. 2009;30:475–487. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowski T, Kokkinidis L, Merali Z, Anisman H. Lipopolysaccharide, central in vivo biogenic amine variations, and anhedonia. Neuroreport. 1998;9:3797–3802. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199812010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Tarr AJ, Liu X, Wang Y, Reed NS, Demarsh CP, Sheridan JF, Quan N. Controlled progressive innate immune stimulation regimen prevents the induction of sickness behavior in the open field test. Journal of inflammation research. 2013;6:91–98. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S45111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damm J, Luheshi GN, Gerstberger R, Roth J, Rummel C. Spatiotemporal nuclear factor interleukin-6 expression in the rat brain during lipopolysaccharide-induced fever is linked to sustained hypothalamic inflammatory target gene induction. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2011;519:480–505. doi: 10.1002/cne.22529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan MP, Quan N, Subramanian SV, Strauch AR, Gajendrareddy PK, Marucha PT. Impaired wound contraction and delayed myofibroblast differentiation in restraint-stressed mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov AI, Kulchitsky VA, Sugimoto N, Simons CT, Romanovsky AA. Does the formation of lipopolysaccharide tolerance require intact vagal innervation of the liver? Auton Neurosci. 2000;85:111–118. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(00)00229-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley KW, Bluthe RM, Dantzer R, Zhou JH, Shen WH, Johnson RW, Broussard SR. Cytokine-induced sickness behavior. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2003;17(Suppl 1):S112–118. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00077-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhans W. Signals generating anorexia during acute illness. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2007;66:321–330. doi: 10.1017/S0029665107005587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence T. The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2009;1:a001651. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CY, Tsai IF, Ho YP, Huang CT, Lin YC, Lin CJ, Tseng SC, Lin WP, Chen WT, Sheen IS. Endotoxemia contributes to the immune paralysis in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2007;46:816–826. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locati M, Mantovani A, Sica A. Macrophage activation and polarization as an adaptive component of innate immunity. Advances in immunology. 2013;120:163–184. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-417028-5.00006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netea MG. Training innate immunity: the changing concept of immunological memory in innate host defence. Eur J Clin Invest. 2013;43:881–884. doi: 10.1111/eci.12132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neviere RR, Cepinskas G, Madorin WS, Hoque N, Karmazyn M, Sibbald WJ, Kvietys PR. LPS pretreatment ameliorates peritonitis-induced myocardial inflammation and dysfunction: role of myocytes. The American journal of physiology. 1999;277:H885–892. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.3.H885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orio M, Kunz A, Kawano T, Anrather J, Zhou P, Iadecola C. Lipopolysaccharide induces early tolerance to excitotoxicity via nitric oxide and cGMP. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2007;38:2812–2817. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.486837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, Wu X, Block ML, Liu Y, Breese GR, Hong JS, Knapp DJ, Crews FT. Systemic LPS causes chronic neuroinflammation and progressive neurodegeneration. Glia. 2007;55:453–462. doi: 10.1002/glia.20467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riediger T, Cordani C, Potes CS, Lutz TA. Involvement of nitric oxide in lipopolysaccharide induced anorexia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;97:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar A, Gonzalez-Rivera BL, Redus L, Parrott JM, O’Connor JC. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase mediates anhedonia and anxiety-like behaviors caused by peripheral lipopolysaccharide immune challenge. Horm Behav. 2012;62:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano T, Izuishi K, Hossain MA, Inoue T, Kakinoki K, Hagiike M, Okano K, Masaki T, Suzuki Y. Hepatic preconditioning using lipopolysaccharide: association with specific negative regulators of the Toll-like receptor 4 signaling pathway. Transplantation. 2011;91:1082–1089. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31821457cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi DW, Zhang J, Jiang HN, Tong CY, Gu GR, Ji Y, Summah H, Qu JM. LPS pretreatment ameliorates multiple organ injuries and improves survival in a murine model of polymicrobial sepsis. Inflammation research : official journal of the European Histamine Research Society … [et al.] 2011;60:841–849. doi: 10.1007/s00011-011-0342-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer C, Kress M. Recent findings on how proinflammatory cytokines cause pain: peripheral mechanisms in inflammatory and neuropathic hyperalgesia. Neurosci Lett. 2004;361:184–187. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarr AJ, Chen Q, Wang Y, Sheridan JF, Quan N. Neural and behavioral responses to low-grade inflammation. Behav Brain Res. 2012;235:334–341. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarr AJ, McLinden KA, Kranjac D, Kohman RA, Amaral W, Boehm GW. The effects of age on lipopolysaccharide-induced cognitive deficits and interleukin-1beta expression. Behavioural brain research. 2011;217:481–485. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian KB, Stevens SL, Marsh BJ, Williams-Karnesky R, Lessov NS, Stenzel-Poore MP. LPS preconditioning redirects TLR signaling following stroke: TRIF-IRF3 plays a seminal role in mediating tolerance to ischemic injury. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2011;8:140. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson B, Viner K. How the immune response to vaccines is created, maintained and measured: addressing patient questions about vaccination. Primary care. 2011;38:581–593. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei XQ, Charles IG, Smith A, Ure J, Feng GJ, Huang FP, Xu D, Muller W, Moncada S, Liew FY. Altered immune responses in mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase. Nature. 1995;375:408–411. doi: 10.1038/375408a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DS, Lahni PM, Denenberg AG, Poynter SE, Wong HR, Cook JA, Zingarelli B. Induction of endotoxin tolerance enhances bacterial clearance and survival in murine polymicrobial sepsis. Shock. 2008;30:267–273. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e318162c190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimomra ZR, Porterfield VM, Camp RM, Johnson JD. Time-dependent mediators of HPA axis activation following live Escherichia coli. American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology. 2011;301:R1648–1657. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00301.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]