Abstract

Parvoviruses encode a small number of ancillary proteins that differ substantially between genera. Within the genus Protoparvovirus, minute virus of mice (MVM) encodes three isoforms of its ancillary protein NS2, while human bocavirus 1 (HBoV1), in the genus Bocaparvovirus, encodes an NP1 protein that is unrelated in primary sequence to MVM NS2. To search for functional overlap between NS2 and NP1, we generated murine A9 cell populations that inducibly express HBoV1 NP1. These were used to test whether NP1 expression could complement specific defects resulting from depletion of MVM NS2 isoforms. NP1 induction had little impact on cell viability or cell cycle progression in uninfected cells, and was unable to complement late defects in MVM virion production associated with low NS2 levels. However, NP1 did relocate to MVM replication centers, and supports both the normal expansion of these foci and overcomes the early paralysis of DNA replication in NS2-null infections.

Keywords: minute virus of mice (MVM), human bocavirus 1 (HBoV1), Parvovirus, non-structural proteins, NS2, NP1, functional complementation, DNA replication block

Introduction

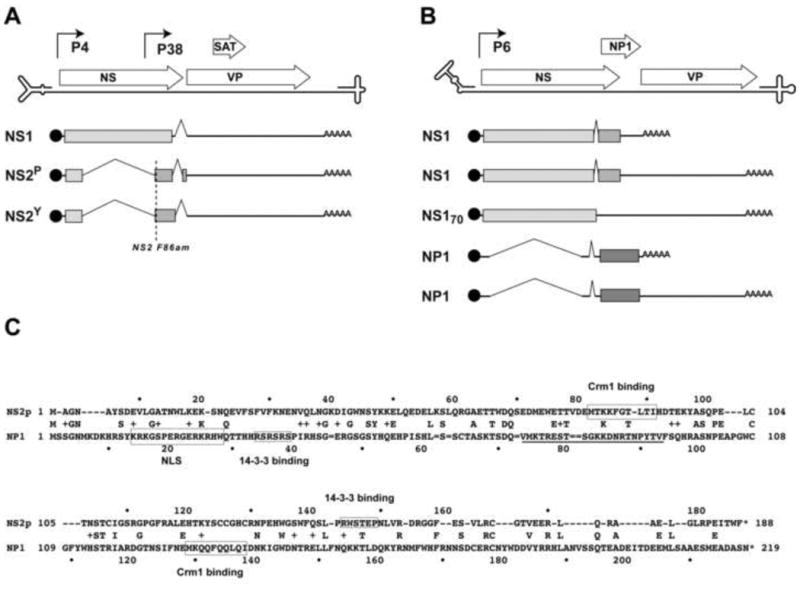

Viruses in the family Parvoviridae have a linear single-stranded DNA genome of around 5kb, with small self-priming hairpin telomeres. Their constrained size leads them to be genetically compact, using from one to three transcriptional promoters and one or two polyadenylation signals to coordinate expression from two genes clusters; a nonstructural (NS or rep) gene that encodes the viral replication initiator protein (NS1 or Rep), and a structural (VP or cap) gene that encodes two or more size variants of a single capsid protein. In addition, all viruses encode a few small ancillary proteins with disparate structures and functions, which are variably disposed throughout the genome (reviewed in Agbandje-McKenna and Kleinschmidt, 2011; Berns and Parrish, 2013; Cotmore and Tattersall, 2013; Halder et al., 2012). These ancillary species are typically conserved between viruses within each genus, but are widely divergent between genera as illustrated for minute virus of mice (MVM), a member of genus Protoparvovirus, and for human bocavirus-1 (HBoV-1), from the genus Bocaparvovirus, in Figs.1A and 1B respectively. Genus names used throughout this paper reflect a recent taxonomic revision in which parvoviruses that infect vertebrate hosts and together constitute the subfamily Parvovirinae are now divided between eight genera, all of which carry the infix “parvo” in their genus names, to clarify their family affiliation as discussed in Cotmore et al., (2013), and posted online at:- http://talk.ictvonline.org/files/ictv_official_taxonomy_updates_since_the_8th_report/m/vertebrate-official/4844.aspx.

Figure 1. Comparison of the coding strategies and sequences of MVM NS2 and HBoV1 NP1 proteins.

Panels A and B. The coding sequences of (A) MVM and (B) HBoV1 proteins and positions of the viral promoters are aligned above line diagrams of the single-stranded viral genomes, which terminate in folded hairpin structures, shown expanded ∼20-fold in scale relative to the coding regions. Below these, NS protein-encoding transcripts are indicated by lines. These express blocks of protein sequence encoded in separate reading frames, indicated by pale, medium and dark grey blocks. AAAAA = polyadenylation sites. “NS2-F86am” marks the position of a termination codon introduced into MVM that prevents stable expression of all NS2-encoding transcripts.

Panel C. The protein sequence of NS2P aligned above that of NP1. Positions of actual NS2 Crm1 and 14-3-3 binding sites and hypothetical NP1 binding sites for these proteins are shown boxed, together with the functional NP1 NLS sequence.

Due to their genetic minimalism, parvovirus DNA replication mechanisms rely predominantly on the synthetic machinery of their host cell, assisted and organized by the NS1 protein, while the ancillary proteins fulfill multiple variable functions during the viral life cycle, often serving, at least in part, to modulate the host environment. In the current study we asked to what extent replication defects that result from loss of the NS2 family of ancillary factors encoded by MVM, can be complemented in trans by expression of the very different HBoV1 NP1 protein. Viruses in these two genera are relatively close phylogenetically, and share the important characteristic of being heterotelomeric, meaning that the hairpin telomeres at the two ends of the genome are very different from each other. In MVM these disparate structures are known to be processed by different mechanisms and at different rates, adding a layer of complexity to the replication process that is not seen for homotelomeric parvoviruses, such as those from the Dependoparvovirus or Erythroparvovirus genera (Cotmore and Tattersall, 2013). Nevertheless, the analogous terminal hairpin sequences of MVM and HBoV1 are very different from each other (Huang et al., 2012), and this is mirrored by their widely disparate ancillary proteins. While both NP1 and NS2 are known to be required for the productive replication of their respective viruses (Chen et al, 2010; Cotmore et al, 1997; Lederman et al,1984; Neager et al, 1990; Neager et al, 1993; Sukhu et al, 2013;), they are encoded in different ways, and the proteins show no apparent protein sequence similarity to each other (Fig 1C), have very different turnover rates, and predominantly occupy different cellular compartments.

As seen in Fig 1A, MVM encodes two major forms of the ∼25kDa NS2 protein, called NS2P and NS2Y, generated by alternative splicing at a small centrally-positioned intron, which differ only in their extreme C-terminal hexapeptides (Morgan et al, 1986; Cotmore and Tattersall, 1990). While NS2 proteins are typically dispensable for productive viral replication in transformed human cell lines (Naeger et al, 1990), they are absolutely required in cells of the virus's normal murine host. These proteins all share a common N terminal domain of 84 amino acids with NS1, but are then spliced into a different open reading frame, as shown in Fig 1A. NS2P and NS2Y “isoforms” accumulate at a ratio of approximately 5:1 during infection, reflecting the stoichiometry of splice donor and acceptor site usage at this intron. NS2 isoforms are the most abundantly-expressed viral proteins during the first few hours after the cell enters S-phase (Ruiz et al, 2006), but both forms are subject to rapid proteosomal degradation (Miller and Pintel, 2001), resulting in a half-life of around 1h (Cotmore et al, 1990).

Mutant viruses that fail to stably express NS2 show a severe defect in viral DNA replication that restricts the accumulation of duplex replicative-form (RF) DNA intermediates to ∼5 % of wildtype levels. While the role of the NS2Y isoform remains uncertain, since mutant viruses that fail to express this species replicate like wildtype virus, mutants that lack NS2P initiate infection efficiently in A9 cells but viral DNA replication aborts early in the duplex amplification phase. This phenotype can be tracked by immunofluorescence microscopy, where it is seen to manifest between 6 and 12 hours into S-phase as a profound block to the normal progressive expansion of viral replication centers (Ruiz et al, 2006), known as autonomous parvovirus replication (APAR) bodies (Cziepluch et al, 2000). However, these structures apparently continue to sequester the same broad range of cellular replication and DNA damage-response proteins that accumulate during the early stages of wildtype infection (Ruiz et al 2011), and even low level expression of NS2P can drive infected cells through the block, suggesting that it involves a small number of NS2 targets or an enzymatic process. In this paper we refer to the ability to overcome this early duplex amplification block as the “critical early function” of NS2.

However, mutants that are able to express low levels of NS2P are still severely impaired in their ability to expand through murine cells, requiring progressively higher, doses of NS2 to maximize the production of progeny virions. The roles played by NS2 in this late “progeny function” are complex, since it is required for both efficient capsid assembly, which is a pre-requisite for virion production, and for early virion release prior to cell lysis, which greatly enhances the rate at which virus spreads between cells. During infection all NS2 species appear predominantly cytoplasmic, in part due to interactions with the nuclear export factor, Crm1, as illustrated by the fact that leptomycin B, a Crm1 inhibitor, allows NS2 to accumulate in the nucleus (Bodendorf et al, 1999). In vitro NS2 binds with high “supraphysiological” affinity to Crm1 (Bodendorf et al 1999; Engelsma et al, 2008; Ohshima et al, 1999), but mutations that modify its Crm1-binding site (Miller and Pintel, 2002), or reduce it to one of physiologically-normal affinity (Eichwald et al, 2002; Engelsma et al, 2008), substantially impair progeny virus production. This implicates the NS2:Crm1 interaction in a late step(s) in virion production or in their subsequent export, perhaps via assembly of a tripartite (Crm1:NS2:virion) nuclear export complex, although such complexes have proven difficult to detect (Engelsma et al, 2008). Phosphorylated NS2 forms also interact with two members of the 14-3-3 family of proteins, which may promote their cytoplasmic retention, but this interaction is not essential for the MVM life cycle, at least in culture, because its disruption has little affect on progeny accumulation (Brockhaus et al, 1996; Nuesch 2005). As indicated in Fig 1C, possible consensus binding sites for 14-3-3 and Crm1 proteins are also present in NP1, but there is as yet no evidence that these sites are functional. However, NP1 does have a potent classical bipartite nuclear localization sequence (NLS) between residues 14-28, which may be embedded within a broader non-classical NLS (residues 7-50; Li Q. et al, 2013), and following both transfection and infection it is reported to accumulate predominantly in the nucleus (Lederman et al,1984; Chen et al, 2010; Sukhu et al, 2013), suggesting that any nuclear export motifs are conditional or of lesser affinity.

As seen in Fig 1B, HBoV1 encodes a single form of its ∼28kDa NP1 ancillary protein, from two similarly spliced mRNAs that are transcribed from the single P6 promoter, but are differentially polyadenylated at one of two possible sites. Transfection experiments with mutant viral genomes suggest that the NP1 proteins of both HBoV1 and minute virus of canines (MVC), a second bocaparvovirus, are required for efficient replicative form (RF) DNA amplification in their respective cells (Huang et al, 2012; Sun et al,2009 2009: Sukhu et al 2013), perhaps recapitulating the “critical early function” observed for NS2. Following transfection, RF replication defects resulting from null mutations in MVC NP1 could be partially rescued by co-expression of its own NP1 sequence in trans, or that from either HBoV1 or the type species of this genus, bovine parvovirus (BPV), which both show <47% identity to the MVC protein (Allander et al, 2005; Sun et al, 2009), indicating that the required activity is conserved between members of substantially disparate viral species, infecting very different host genera.

In addition, NS2 and NP1 both influence progeny virus production by controlling the availability of precursor capsids, although they achieve this in very different ways. Thus, during infection of murine cells MVM NS2 is required for efficient capsid accumulation, at least in part because it influences the efficiency with which VP precursors are assembled into particles (Cotmore et al, 1997), while in MVC infections NP1 expression allows read-through of the internal (proximal) polyadenylation site, which is required for the accumulation of viral mRNAs encoding the capsid gene (Sukhu et al, 2013). Although the mechanism controlling NP1-mediated suppression of this site remains uncertain, it is of particular interest because it represents the first example of a parvoviral ancillary protein being used to modulate RNA processing.

In the studies reported here we show that, despite the many apparent disparities between NS2 and NP1, induced expression of the HBoV1 NP1 protein in murine cells functionally complements a major defect resulting from the loss of NS2.

Results

Development of an inducible (tet-On) A9 cell line expressing HBoV1 NP1

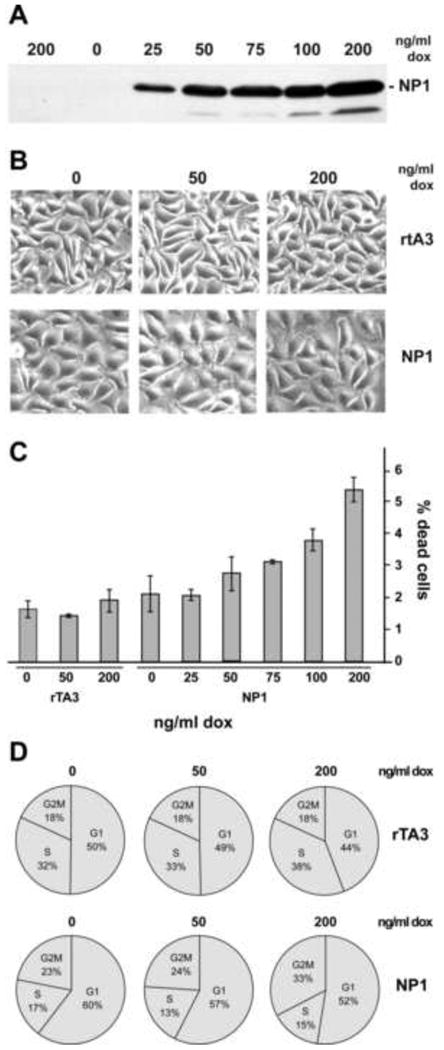

A non-clonal A9 cell population in which expression of the HBoV1 NP1 protein could be induced by exposure to the tetracycline analogue doxycycline (Dox) was created by sequential infection with two lentivirus vectors. The first allowed hygromycin selection for expression of the tetracycline-dependent repressor/transactivator mutant rtTA3 (pLenti-CMV-rtTA3-Hygro), creating the A9rtTA3 cell population, while the second allowed bleomycin/hygromycin double-selection for cells expressing the HBoV1 NP1 protein in the presence of Dox (pLV-tetO-NP1-Bleo), creating the A9-/+NP1 population, as detailed in the Methods section. When maintained in medium without Dox, rtTA3 binding to tetO is very low and NP1 expression is barely detectable, but addition of Dox at different concentrations from 25ng/ml to 200ng/ml led to the progressive accumulation of NP1, as assessed by Western analysis using a polyclonal rabbit serum specific for NP1 amino acids 76-91 (Fig 2A). In this Figure, NP1 expression is shown after induction for 40h, since this was the maximum period of sustained induction used in subsequent co-infection experiments. NP1 accumulation was apparent after exposure to the lowest Dox concentration (25ng/ml), and showed an approximately linear response to drug concentrations up to 75ng/ml, but a sub-linear response at higher concentrations.

Figure 2. Construction and characterization of an inducible (tet-On) A9 cell line expressing HBoV1 NP1 (A9-/+NP1).

Panel A. Kinetics of induction of NP1, as estimated by Western blotting, in the A9-/+NP1 cell line incubated with escalating doses of Dox for 40h. The left lane contains an extract of control A9rTA3 cells treated with the highest dose of dox.

Panel B. Effect of increasing doses of dox on the cellular morphology of A9 rTA3 and A9-/+NP1 cell lines.

Panel C. Cell viability of A9 rTA3 and A9-/+NP1 cell lines after treatment with different doses of dox for 40 h.

Panel D. Typical changes in cell cycle profile for A9 rTA3 and A9-/+NP1 cell lines following exposure to dox for 40 h.

Physiological changes associated with HBoV1 NP1 expression

Induced cells were first examined for signs of toxicity using phase contrast microscopy After 40h A9-/+NP1 cells induced with low doses of Dox (≤50ng/ml) were essentially indistinguishable from un-induced cells, and while slight swelling and increased ruffling was seen at higher doses, there was no overt toxicity (Fig 2B). Similarly, the percentage of dead cells, as assessed by flow cytometry using a Far red Live/Dead assay, was minimally influenced by NP1 induction even at the highest doses of Dox, (from 2.1% in the absence of induction, to 5.4% after exposure to 200ng/ml Dox for 40 hours), while at 50ng/ml and below no significant differences were observed (Fig 2C). Flow cytometry of propidium iodide stained cells revealed that the cell cycle profiles of uninduced A9rtTA3 and A9-/+NP1 cell populations were slightly different (Fig 2D), but within each population exposure to Dox had only minor effects. Thus, in both cells types exposure to Dox at 200ng/ml resulted in a slight reduction in the proportion of cells in G1, which in A9-/+NP1 cells correlated with an increase in cells at the G2/M boundary, but without any conspicuous effect on the percentage of cells in S-phase.

We also looked for evidence of induced DNA damage responses associated with NP1 expression. Infection with minute virus of canines (MVC), from the genus Bocaparvovirus, is known to activate the cellular Ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) pathway, and this has been shown to be essential for efficient viral DNA amplification (Luo et al, 2011). However, such activation appears to result from physical association of the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 (MRN) DNA damage sensor with replicating viral genomes, rather than from expression of the viral proteins (Lou et al, 2013). In accord with this observation, in the A9-/+NP1 population HBoV1 NP1 induction with the highest doses of Dox for 40 hours resulted in only slight (∼2-fold) increases in the accumulation of phosphorylated H2AX (γH2AX) and activated Ser1981-pATM (data not shown). Overall, we conclude that protracted incubation with high doses of Dox has a slight but detectable effect on cell physiology, but that exposure to 50ng/ml results in substantial NP1 induction without any significant effects on cell viability or cell cycle progression.

Time course of NP1 expression

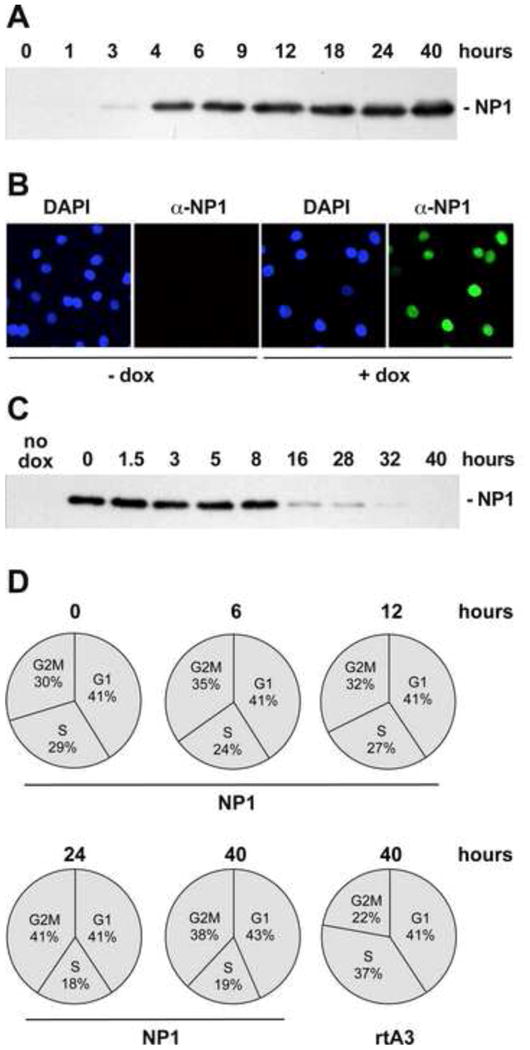

We next explored NP1 expression with time following Dox induction at 50ng/ml. As shown in Fig 3A, NP1 could be detected by western blotting after induction for 3 hours, and began to plateau after approximately 12 hours. The immunofluorescence staining analysis shown in Fig 3B revealed that >95% of these cells became rather uniformly positive for nuclear NP1 by 24 hours after the addition of Dox. In a second assay, cells were incubated with Dox for 24 hours and it was then removed, and the remaining NP1 levels monitored with time over the next 48h (Fig 3C). Under these conditions, NP1 levels remained steady for the first 8 hours, but then declined, giving a half life of between 8-16h. In induced A9-/+NP1 cells this half-life reflects the kinetics of repressor binding to the expression construct, together with the combined stability of the protein and its mRNA. Overall, this indicates that protein expression is stable for many hours following its induction, and suggests a protein half-life that is similar to the reported half-life of 6∼8 hours for the MVC NP1 protein observed during infection of WRD canine cells (Sukhu et al., 2013).

Figure 3. Time course of NP1 expression following addition of dox at 50 ng/ml, and its effect on cell cycle profiles of A9 rTA3 and A9-/+NP1 cell lines.

Panel A. Western blot analysis of whole cell lysates from A9-/+NP1 cells at different times after NP1 induction.

Panel B. Immunofluorescence images showing the nuclear localization of NP1 after induction with dox at 50 ng/ml for 24h.

Panel C. Kinetics of NP1 protein loss after removal of dox.

Panel D. Cell cycle profiles of A9rTA3 and A9-/+NP1 cell lines at different times after NP1 induction with 50 ng/ml dox.

Since productive infection with MVM requires cells to enter S-phase under their own cell cycle control, and we ultimately intended to infect induced cell populations with this virus, we also monitored cell cycle progression in A9-/+NP1 cells with time after NP1 induction. Flow cytometry of propidium iodide stained cells (Fig 3D), showed that induction with 50ng/ml of Dox for up to 12 hours had no detectable effect on cell cycle distribution, while sustained incubation for an additional 12-28 hours was associated with a limited reduction in the proportion of cells entering S-phase, from around ∼25% to ∼18%, and a coordinate increase in the proportion of cells in G2M, from ∼34% to ∼40%. Since MVM cell entry typically takes several hours (Farr et al, 2006), we concluded that if cells were induced with 50ng/ml Dox at the time of MVM infection, NP1 expression should be well established when infecting viruses reached the cell nucleus and initiated infection, but that such cells should enter S-phase with normal kinetics.

Relative NP1 and NS2 expression levels

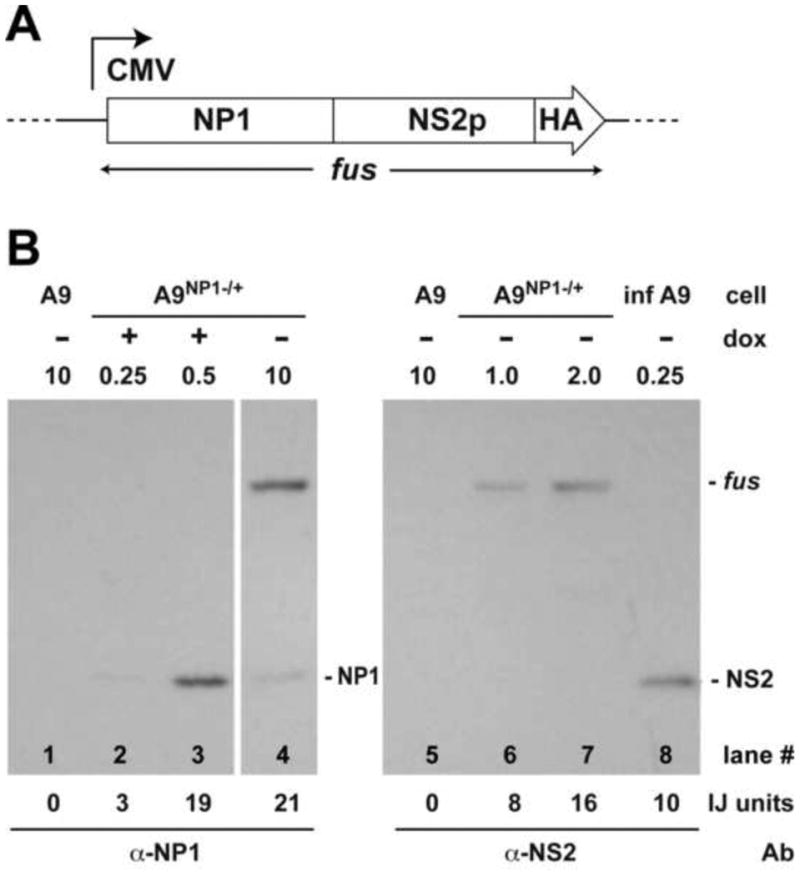

When A9-/+NP1 cells were induced for 24h with 50ng/ml Dox and examined by immunofluorescence microscopy, the great majority of cells showed evidence of nuclear NP1 expression, although the intensity varied somewhat from cell-to-cell (data not shown, re-examined in detail below). In order to estimate how NP1 expression levels compared, on a molar basis, to NS2 levels generated in such cells during infection, we created a CMV-driven NP1-NS2 fusion construct, shown in Fig 4A. Following transfection into the A9-/+NP1 population, cell extracts were prepared and their protein content quantified prior to Western analysis. Accumulation of the expressed ∼50kDa fusion protein was detected with rabbit antibodies directed against either NP1 or NS2 over a range of extract concentrations, and compared using Image J (IJ) software. Concentrations were then selected that gave staining within a linear range for each antibody. As illustrated in Fig 4B, lane 4, when stained with the anti-NP1 antibody, 10ug of one such extract gave 21 arbitrary IJ units (or 2.1 units per ug protein), while when stained with the NS2-specific antibody 1 or 2ug of the same extract (lanes 6 and 7) gave a fusion band of 8 and 16 IJ units respectively (or 8 IJ units per ug protein). Thus staining of the fusion protein with the NS2 antibody gave signals that were approximately 4x stronger than those obtained using anti-NP1.

Figure 4. Quantitative measurement of relative NP1 and NS2 expression levels.

Panel A. Schematic representation of the CMV-driven NP1-NS2-HA fusion construct.

Panel B. Western quantification of NP1 accrual relative to total NS2 accumulation 24h after infection with wild type MVMp. Lanes 1 and 5 contain 10ug of extract from untransfected A9 cells. The quantity of test extract (in ug protein) is indicated above each lane, in all cases adjusted to a total of 0.25ug with extract from uninfected A9s, as required. Lanes 2 and 3 contain extract (0.25ug and 0.5ug, respectively) from A9-/+NP1 cells after induction with 50 ng/ml of dox for 24 h. Lanes 4, 6 and 7 contain extract (10, 1 and 2ug, respectively) from uninduced A9-/+NP1 cells that had been transfected with the fusion construct described in panel A. Lane 8 contains 10ug of extract from A9 cells infected with MVMp for 24 h as described in material and method section. Lanes 1 to 4 were probed with a polyclonal antibody directed against NP1 residues 76-91, and lanes 5 to 8 with a rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against the N-terminal 84 amino acids of NS2. Image J (IJ) units are shown at the bottom of the figure. “fus” = NP1:NS2:HA fusion protein.

On the same membranes, NS2 levels induced in A9 cells 24h after infection with wildtype MVMp at an input multiplicity of 10,000 vg/cell were determined (lane 8), and the percentage of cells infected at this multiplicity determined by indirect immunofluorescence microscopy. When blots of these extracts were stained with anti-NS2 (lane 8) 0.25ug of extract gave 10 IJ units, but only 50% of these cells showed evidence of NS expression by immunofluorescence, meaning that 0.25ug from a fully infected cell population would be expected to yield ∼20 IJ units (or 80 IJ units per ug of extract). In contrast, 0.5ug of extract from A9 -/+NP1 cells that had been induced with 50ng/ml Dox for 24h (lane 3) stained with an intensity of 19 IJ units using the anti-NP1 antibody. Based on these values, and taking into account the 4x difference between the staining intensity of the antibodies per microgram of target protein, NP1 expression in 1ug of the induced A9-/+NP1 extract (38 units) would be equal to around 152 units of NS2 expression, which is approximately twice the 80 units of NS2 that would be expected from 1ug of 100% MVMp infected cell extract. This suggests that NP1 induction under these conditions is approximately equivalent on a molar basis to twice the level of NS2 expression seen per infected cell 24 hours post infection, and is likely to be within a physiological range for NP1 expression during HBoV1 infection. We use this level of Dox induction in all subsequent experiments.

Effects of NP1 induction on MVM replication centers

The cellular location of NP1 was monitored following Dox induction of uninfected A9-/+NP1 cells by immunofluorescence microscopy. As indicated previously, although staining intensities varied, NP1 expression was apparent in most cells, generally exhibiting a diffuse nuclear distribution that was interrupted by a small number (∼2-4) of more intense foci, as illustrated in Fig, 5A, top panel. These foci typically co-localized with gaps in DAPI staining, suggesting that they might correspond to nucleoli. This localization was confirmed by immunofluorescent staining for fibrillarin, a highly conserved protein associated with small nucleolar RNAs (Westendorf et al,1998).

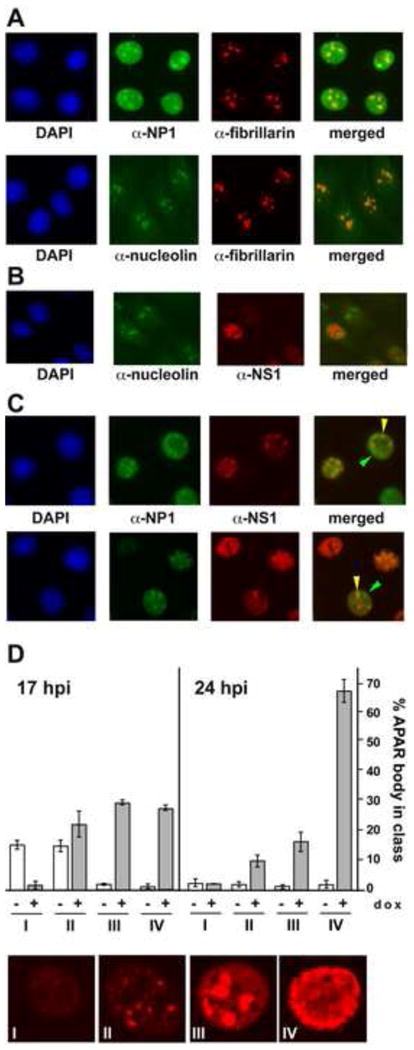

Figure 5. Nuclear and nucleolar localization of NP1.

Panel A. After induction of A9-/+NP1 cells with 50 ng/ml dox for 24h, NP1 shows a diffuse nuclear distribution, interrupted by discrete foci that colocalize with fibrillarin as detected by staining with mAb 72B9, and thus correspond to nucleoli (upper panel). To confirm this localization, mAb 72B9 staining is shown to colocalize with nucleolin in uninduced A9-/+NP1 cells (lower panel).

Panel B. The MVM nonstructural protein NS1 is specifically excluded from nucleoli during infection.

Panel C. Distribution of NP1 foci following infection with wild type MVMp. During single round infections with MVMp, NP1 is relocated from many, but not all, nucleoli, and progressively colocalizes with NS1 in developing MVM replication foci, known as APAR bodies. Green arrowheads indicate NP1 still localized in nucleoli, whereas yellow arrowheads indicate NP1 that has relocalized to APAR bodies.

Panel D. Histograms showing the percentages of NP1 negative and NP1 positive APAR bodies present 17 and 24h after infection with MVM. At each time point 250 APAR bodies were scored both for NP1 and for their stage in APAR development, from stages I to IV (examples of each stage are shown at the bottom of panel D). Plotted data was from two independent experiments.

Nucleoli also showed punctate staining in these cells with rabbit antibodies specific for the major nucleolar phosphoprotein, nucleolin, which co-localized with fibrillarin (Fig 5A, lower panel). Following infection with MVMp, NP1 and NS1 distribution in induced A9-/+NP1 cells was then compared using anti-nucleolin antibodies to identify nucleoli. It has previously been shown that at around six hours into S-phase, viral DNA replication first becomes apparent in distinct viral replication centers, called Autonomous Parvovirus-associated Replication (APAR) bodies (Cziepluch et al, 2000; Ruiz et al, 2006). As seen in Fig 5B, in A9-/+NP1 cells nucleoli, stained for nucleolin, were quite separate from these NS1 containing APAR bodies, but during MVM infection NP1 was progressively lost from many nucleoli and began instead to colocalize with NS1 in APAR foci, as illustrated in Fig 5C.

Progressive changes in MVM NS1 distribution in infected A9 cell nuclei with time in S-phase have been described in detail (Ruiz et al, 2011). That study identified a series of stages, designated I to IV, with NS1 first emerging as a large number of small faint speckles that were spread throughout the nucleus but absent from nucleoli (class I). As NS1 expression intensified, the protein appeared to accumulate, staining more intensely in a limited number of (<∼10) larger foci that occupied around half of the nuclear space (class II), and then coalesced into 2-4 progressively larger foci (class III), before spreading through the entire nucleoplasm (Class IV). APAR bodies correspond to classes II and III in this scheme, and are fairly short lived in wild type infections, remaining as discrete foci for just a few hours (Ihalainen et al., 2007; Ihalainen et al., 2009). To monitor the progressive redistribution of NP1 with time during infection, individual APAR foci in cells that were double positives for NS1 and NP1 expression, were ranked according to their APAR class, as illustrated by the higher-power micrographs shown in Fig 5D, and scored for the presence or absence of NP1, as detailed in the histogram. This shows that at the first time point (17h post infection), most class I foci and around 40% of class II foci lacked NP1, but that as APAR bodies matured most of them became NP1 positive, and this accumulation was even more apparent at later times post infection. These observations suggest that NP1 forms specific interactions that cause it to relocate to the sites of early viral DNA replication.

As shown in Fig 5D and Fig 6A upper panel, the smaller APAR foci are typically short-lived in wildtype infections, and progress rapidly to type IV. In contrast, in cells infected with the NS2-null mutant F86am, they generally fail to progress beyond the class II amplification stage, as seen in the absence of Dox induction in Fig 6B, upper panel. The F86am mutant has a single amber termination codon replacing the phenylalanine at residue 86 in NS2, but rather than inducing premature termination of the polypeptide, this nonsense mutation stops the detectable accumulation of all NS2 species, likely because the splicing pattern required to express the mutated central exon is suppressed, as shown for some other NS2 nonsense mutants (Gersappe et al, 1999). When used to infect A9 cells, F86am exhibits the severe early defect in duplex DNA amplification and the deficiency in capsid assembly and accumulation discussed earlier (Cotmore et al 1997). However, as seen in Fig 6B, lower panel, NP1 induction was able to rescue the impaired maturation of APAR foci in many of the F86am-infected cells, causing their NS1 expression profiles to progress to classes III and IV. Quantifying this data, by classifying and counting individual cells (Fig 6C), revealed that the class IV NS1-staining pattern was observed in <5% of uninduced F86am-infected cells, but in ∼40 % of cells following NP1 induction, which is close to the ∼50% involvement seen in control MVM wildtype infections. Notably, as observed in the wildtype infection, NS1 and NP1 effectively colocalized in class II and III foci in the F86am infections, placing NP1 in close proximity to the replicating viral DNA. Overall, we conclude that NP1 expression in F86-am NS2-null infections allows greatly enhanced APAR development, which in a wildtype infection would normally be associated with progressive duplex DNA amplification.

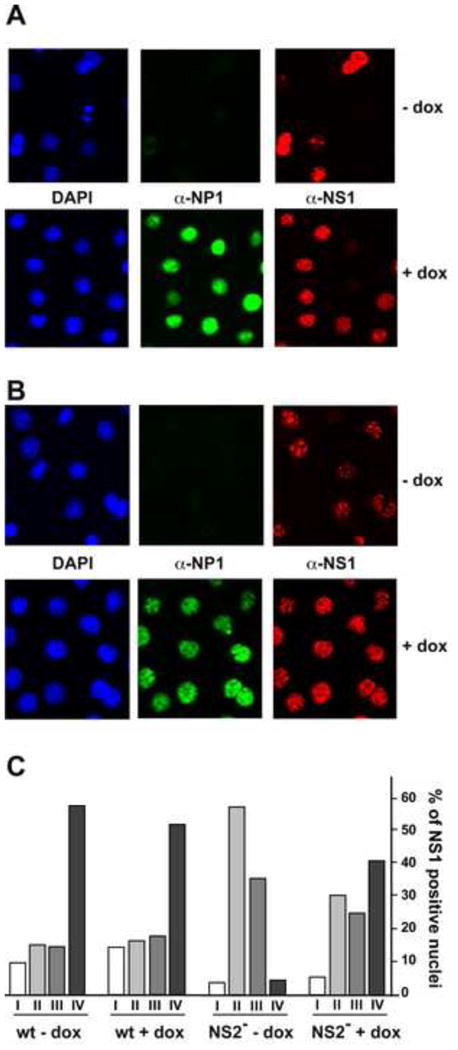

Figure 6. NP1 expression rescues APAR body maturation in cells infected with an F86am (NS2null) mutant of MVMp.

Panel A. Patterns of NP1 expression and APAR body maturation in A9-/+NP1 cells infected with wild type MVMp in absence or presence of dox.

Panel B. Patterns of APAR body maturation in A9-/+NP1 cells infected with the F86am (NS2null) mutant. In the absence of NP1 expression (upper panel), APAR maturation becomes progressively paralyzed at stages II or III. Expression of NP1 partially rescues this phenotype, allowing progression to stage IV (lower panel).

Panel C. Histogram to quantify differences in APAR body maturation following NP1 induction. Cells from infections shown in panels A and B (1200 per infection) were scored for the developmental stage their APAR foci.

HBoV1 NP1 partially complements replication defects in MVMp NS2-mutants

We then used the NS2-null F86am mutant to ask if NP1-induction can substitute for NS2 during early stages in infection. To explore NP1 complementation under conditions of less extreme NS2 deficiency we also used the mutants P-Y+ and PloY-, which allow limited accumulation of specific NS2 isoforms (Ruiz et al, 2006). During wildtype MVMp infections, NS2P and NS2Y are expressed at an approximately 5:1 ratio, but in the P-Y+ mutant the major isoform fails to accumulate, and the minor form, NS2Y, remains expressed at its normal levels. In contrast, with the PloY- mutant, NS2Y accumulation is lost and NS2p expression is restricted by a mutation that impairs the efficiency of the large NS2 splice.

In these experiments, we coordinately induced NP1 expression in asynchronous populations of A9-/+NP1 cells with 50 ng/ml Dox and infected the cultures with wildtype or mutant MVM particles at an input multiplicity of 10,000 vg/cell. After allowing time for viral penetration, neuraminidase-containing medium was added to restrict infection to a single round, and cells were harvested 24 hours post infection. Western transfers (Fig 7A) showed that infection with wildtype or mutant viruses had little, if any, effect on NP1 accumulation and, as expected, NS2 was not detected in infections with the NS2-F86am mutant. While NP1 induction did result in a slight (∼10-20%) reduction in wildtype levels of NS1 and NS2 accumulation (Fig 7A, lanes 3-4), it had no effect on the more restricted NS2 accumulation seen for P-Y+ and PloY- mutants, and it marginally enhanced NS1 levels resulting from all mutant infections. Probing with isoform-specific antibodies and phosphoimager quantification confirmed that only NS2Y was expressed in cells infected with the P-Y+ mutant, and that its accumulation was substantially restricted relative to the total NS2 levels seen for wildtype virus, while infections with the PloY- mutant only supported NS2P expression, which accumulated to around 10% of wildtype levels.

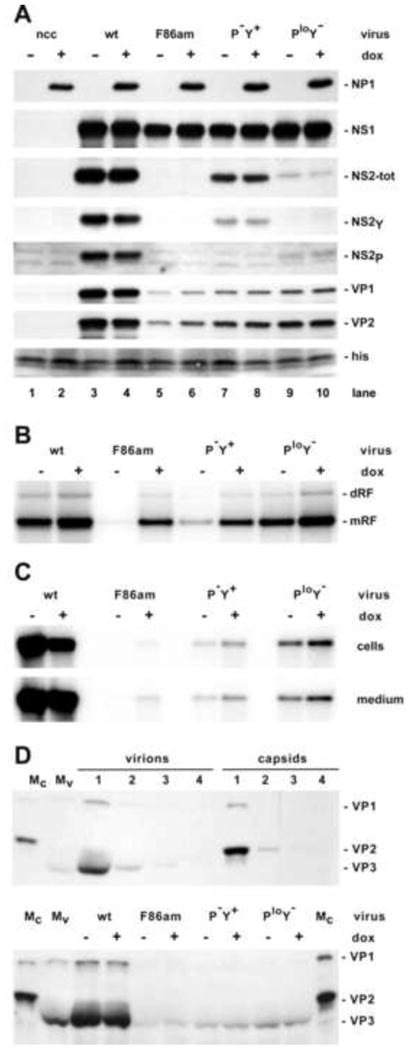

Figure 7. Effects of NP1 expression on the course of A9-/+NP1 infections with MVMp wild type and NS2 dosage mutants.

Panel A. Western blots showing the accumulation of viral proteins after infection with wildtype and NS2-mutant MVMp viruses in presence or absence of dox, as indicated above the blot. NS2-tot denotes all forms of NS2; his indicates the position of histones, used as a loading control, following detection with Ponceau Red.

Panel B. Duplex intracellular replicative-form (RF) viral DNA generated in single round infections in absence or presence of NP1 expression, analyzed by Southern transfer after electrophoresis through a non-denaturing gel. Monomer (mRF) and dimer (dRF) duplex intermediates are indicated.

Panel C. Cell number-matched samples of nuclease-protected virion DNA from cell pellets (upper panel) and culture medium (lower panel), analyzed by Southern blotting after electrophoresis through denaturing gels.

Panel D. Gradient profile analysis of viral particles released into the culture medium of A9-/+NP1 cells infected with wildtype and NS2 mutant MVMp. In the upper panel a western blot shows VP species present in fractions 1-4 of analytical iodixanol step gradients used to sediment trypsin-digested full virions and empty MVM capsids. Since trypsin cleaves VP2 to VP3 in full virions, but not in empty particles, this analysis shows that both types of particle sediment into fraction 1 of the gradients. The lower panel shows VP proteins recovered in fraction 1 of equivalent gradients used to sediment particles recovered in the cell culture medium following trypsinization of A9-/+NP1 cells infected with wildtype and mutant virions that had been cultured in the presence or absence of dox, as indicated. Mc and Mv denote empty and full particles used as marker proteins.

In the absence of NP1, capsid protein accumulation for F86-am infections was limited to around 10% of wildtype levels, as expected, while the progressive increases in NS2 expression seen for the P-Y+ and PloY- mutants were associated with increases in capsid accumulation to ∼20-40% of wildtype levels. While sole expression of NS2Y by the former mutant correlated with a small increase in capsid protein accumulation (∼20% of wildtype), expression of NS2P alone by the PloY- mutant, even at much lower copy number, resulted in slightly more effective capsid protein accretion (< 30%), indicating that on a molar basis the NS2P isoform is substantially better able to promote capsid protein production and/or accumulation. Nevertheless, VP accumulation in all NS2 mutants was substantially impaired relative to wildtype, and NP1 expression, which under the conditions used here should result in NP1 accumulation to approximately twice the concentration of NS2 in the wildtype infection, had a negligible impact on the defect. We conclude that the dosage-dependent role played by NS2P in capsid protein accumulation cannot be complemented in trans by NP1. Since capsid quantitation by western analysis measures both assembled and unassembled VP proteins, this defect likely reflects their failure to assemble into particles, which leads to poor VP accumulation since unassembled proteins turn-over more rapidly than intact capsids (Cotmore et al, 1997).

In contrast, coincident expression of NP1 had a major affect on the early duplex DNA amplification block observed for the F86am NS2-null mutant (Fig 7B). In this case, RF accumulation in the F86am infection was rescued to around 65% of the level seen with wildtype virus in the absence of NP1. While RF accumulation was also substantially (∼20%) enhanced in the wildtype infection by NP1 induction, this may in part reflect a reduction in single-strand encapsidation since progeny virion accumulation was impaired in this group, as shown below (Fig 7C). Similarly, NP1 expression enhanced RF accumulation in all mutant infections, although on a molar basis its effects were not as potent as those of NS2P, which supported infection to ∼90% of wildtype levels when expressed at just ∼10% of its normal concentration. Overall, this data provides an explanation for the enhanced APAR maturation seen in the presence of NP1, and shows that NP1 can efficiently complement the early critical function performed by NS2. Thus, without having any conspicuous sequence homology, elements in NP1 are functionally homologous to NS2.

Progeny single-strand DNA production is difficult to quantify in neutral gels because it migrates as a broad diffuse band. To overcome this problem we used a packaging assay in which extracts were extensively nucleased to destroy non-encapsidated DNA before the single-strands were released, and these were then quantified as single bands following migration through denaturing alkaline gels and Southern transfer. Using this approach, single-strand accumulation in the cell pellet and medium were assessed 40 hours after infection, with and without Dox addition (Fig 7C). Virion accumulation was extensive in both cells and medium from wildtype infections, with the latter being predominantly due to early virion release, since cell death remained limited at this time, as detailed below. In contrast, encapsidated DNA was rare in cells and medium from F86am NS2-null infections, very slightly more abundant in samples from P-Y+ infections, and present in approximately NS2 dosage-dependent levels in the PloY- infection. However, NP1 expression had a relatively minimal influence of these levels. Thus for each mutant, virion production was severely impaired relative to RF amplification or even capsid protein accumulation, but NP1 was unable to complement this defect. Inefficient capsid assembly, as likely occurs under these conditions, typically leads to a deficiency of virion production more profound than that predicted from VP protein accumulation, as measured by western blot, since only intact particles are able to support packaging.

By 40h post infection >50% of the protected virion DNA generated by wildtype infections had been released into the medium both with and without NP1 (Fig 7C). To ascertain the extent to which this virus was released by directed transport rather than cell lysis, we performed the capsid analysis shown in Fig 7D. This assay relied upon the fact that the trypsin used to harvest infected cells also digested VP2 N-termini exposed at the surface of full virions, but not empty particles, creating the VP3 form. Using small iodixanol step gradients and centrifugation conditions designed to deliver both full and empty particles into the first (bottom) gradient fraction, we monitored virion and empty particle accumulation by Western transfer using antibodies directed against denatured capsids, scoring for the presence of VP2 versus the N-terminally proteolysed VP3 form. As shown in Fig 7D, upper panel, reconstructions using purified full and empty particles showed that more than 90% of both types of particle sedimented into the first fraction, and could be readily identified by the size of their predominant VP2/3 species. When used to analyze medium from infected cells (Fig 7D, lower panel), the majority of particles from all samples contained predominantly VP3, indicating that full virions were preferentially released from these cultures and suggesting that cell lysis, which leads to the release of both full and empty particles, was as yet negligible. This analysis also confirmed that capsid release from cells infected with NS2 mutants was minimal compared to wildtype infections (<5%), support the contention that overall VP accumulation was impaired in all mutants, and recapitulating the virion DNA disparity seen between these infections by Southern analysis (Fig 7C).

However, Fig 7C also shows that approximately 50% of the total virions were exported from all infected cells, irrespective of how many virions were generated by each mutant. Thus the analyses provide no evidence that the virion export mechanism is defective in NS2 restricted infections, or that NP1 can influence this process. Thus in the current experiments virion production, rather than export, was most severely impacted by low NS2 levels. However, it remains possible that so few virions are produced in the mutant infections that they fail to overwhelm the cell's basal export capacity, and so do not recapitulate the extensive requirement for NS2:Crm1-mediated virion export discussed above.

Overall, we conclude that NP1 expression substantially rescues NS2-null infections from a profound early DNA amplification block, but fails to complement later defects in capsid accumulation and progeny virus production that result from inadequate levels of NS2.

Discussion

In this paper we demonstrate that the HBoV1 NP1 protein can be conditionally expressed in a non-clonal population of murine A9 cells without evoking major changes in cell cycle control or cell death. Thus, although HBoV1 NP1 has been reported to induce apoptosis following transfection into HeLa cells (Sun et al, 2013), this is not observed in many other cell types (Sun et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2010) or following NP1 induction in this study, and may reflect a unique interaction with HeLa cells, perhaps involving their transforming papilloma virus proteins (DeFilippis et al, 2003).

However, despite its conspicuous lack of homology with the multifunctional MVM NS2 proteins, we show that inducible expression of NP1 during infection with MVM NS2 mutants effectively rescues an early and extreme defect in viral duplex DNA amplification associated with the NS2-null phenotype, although it cannot substitute for NS2P in later, dosage-dependent, role(s) played by this protein in progeny virion production. Following its induced expression in A9 cells, NP1 predominantly accumulates in the nucleus, adopting both a nucleoplasmic and nucleolar distribution that has not been reported previously. However, during infection with wildtype or NS2 mutant MVM, NP1 is progressively withdrawn from most nucleoli and begins to co-localize with NS1 in developing viral replication foci. How the assembly of such foci is initiated, and how their many constituent proteins are recruited remain poorly understood, but this translocation would position NP1 in close proximity to the replicating viral DNA. In NS2-null mutant infection this event coincides with the ability of NP1 to rescue APAR body maturation from stage II to stage IV foci and to substantially evade the shutdown of viral replication. The molecular basis for this early block and how it is subverted by NS2 remain to be determined, but the block occurs soon after the initiation of viral DNA amplification, at a time when direct competition for cellular resources appears unlikely. This timing suggests that it may well be a response to replicating nuclear DNA. and its induction should result in changes in the way the infected cell responds to experimental stimuli, as recently reported, for example, for IL-6 expression in response to poly I-C stimulation (Mattei et al. 2013), or Chk1 activation in response hydroxyurea treatment (Adeyemi and Pintel, 2014a). Overall, plausible explanations include failure to evade aspects of the induced DNA damage response (Adeyemi et al, 2010; Ruiz et al, 2011), failure to subvert the cell cycle (Adeyemi and Pintel, 2014b: Cotmore and Tattersall, 2013), or the induction of an innate antiviral response to replicating viral DNA, which NS2P, and by extension NP1, would be able to suppress. This latter mechanism is supported by the finding that HBoV1 replicates in polarized primary human airway epithelia (Huang et al, 2012; Deng et al., 2013), which in vivo are highly exposed to inhaled respiratory microbes and may be particularly well equipped to resist them.

In contrast, NP1 shows no evidence of complementing either of the subsequent capsid accumulation or virion release defects that perturb progeny virion production in the restricted low-NS2 phenotype. The high levels of NS2P required for efficient capsid assembly suggests that stoichiometric interactions between NS2 and either a cellular intermediary or the capsid precursors are required. However, it is remarkable that capsid assembly is so dependent upon NS2 during infection of A9 cells, since VP proteins are readily assembled into particles without this ancillary protein during infection of transformed human cells, or even when VP2 is expressed on its own in insect cells. Possibly NS2, or a factor that it recruits, is required to perform a chaperone-like function, as demonstrated for the assembly-activating protein, AAP, encoded by the related adeno-associated viruses (AAV). In AAV this protein is located within the capsid gene, expressed from the same mRNA as VP2, and targets VP proteins to the nucleoli, where it interacts with their C-termini, inducing a conformational shift that appears to promote particle assembly (Naumer et al, 2012; Sonntag et al, 2010). A small alternatively translated (SAT) protein is encoded in a similar position in the protoparvovirus porcine parvovirus, and is known to affect the rate at which infections spread through culture (Zadori et al, 2005). However, SAT does not appear to be directly homologous to AAP, and nonsense mutations inserted into the equivalent sequence in MVM do not prevent capsid assembly (our unpublished results), so that it is not clear how this sequence functions.

Alternatively, NS2, or a factor that it recruits, may serve a critical transport function that impinges on capsid assembly, removing assembly inhibitors from the nucleus or promoting the influx of required factors that would otherwise by exported by cellular mechanisms. Thus, the cellular export factor Crm1, which binds NS2 with supraphysiological affinity, might mediate such assembly functions in addition to its proposed direct role in early virion export (Eichwald et al, 2002; Miller and Pintel, 2002; Engelsma et al, 2008). This interpretation is supported by in vivo selection studies in which mutations in a region of NS2 that is immediately C-terminal to its Crm1 binding site, further enhanced NS2:Crm1 interactions, leading to conspicuous Crm1 accumulation in the cytoplasm and early and enhanced virion production rather than specifically facilitated viral egress from the cell (Lopez-Bueno et al., 2004). When one such mutation was introduced into an MVM genome that gave low NS2 accumulation levels when transfected into A9 cells, the mutation allowed progeny single-strand DNA replication, which suggests that it enhanced availability of competent capsids (Choi et al, 2005). While not measured in this earlier study, the severe defect in capsid accumulation seen in the present studies indicates that this is likely to be the major late defect in NS2-low infections, and suggests that high levels of nuclear Crm1 may constitute a dosage-dependent block to particle assembly and accumulation. Preliminary studies indicate that expression of high levels of NP1 in A9-/+NP1 cells, has no conspicuous effect on the distribution of Crm1 (data not shown). Further studies will be required to elucidate the mechanism underlying late defects in NS2-low infections, but the present studies indicate that HBoV1 NP1 does not complement this aspect of the complex phenotype exhibited by MVM mutants defective in the expression of NS2.

Materials and Methods

Constructs

pLV-tetO-NP1

Nucleic acids from a respiratory specimen positive for HBoV1 by PCR were extracted with the QIAamp nucleic acid purification kit (Qiagen). The coding sequence for HBoV1 NP1 was amplified using HotStarTaq DNA polymerase (Qiagen), with primers based on the HBoV ST2 sequence (GenBank accession number DQ000496), and cloned into the expression plasmid pcDNA3.1. The insert was sequenced to confirm that it corresponded exactly to ST2. This coding sequence was then used to replace the SOX2 gene in the EcoRI site of Addgene plasmid 19765, pLVtetO-SOX2 (Stadtfeld et al, 2008).

NP1-NS2p-HA fusion construct

First, a cDNA sequence encoding the MVMp NS2p protein with a C-terminal HA-tag was generated using a PCR primer encoding the HA-tag and Platinum Pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). This was cloned between the Hind III and Xba I sites in the pCDNA3.1 polylinker, generating an intermediate construct called pCDNA3 NS2p-HA. The coding sequence of HBoV1 NP1 was then amplified using primers based on the HBoV ST2 sequence and cloned into the Hind III site immediately upstream of NS2 in pCDNA3 NS2p-HA, generating pCDNA3.1 NP1- NS2p-HA.

Cells and viruses

The prototype strain of MVM (MVMp, GenBank accession number J02275) and its NS2 mutant derivatives F86-am, P-Y+, and PloY- (Ruiz et al, 2006) were propagated in the SV40-transformed newborn human kidney cell line 324K. Viral stocks were purified by centrifugation through iodixanol (Optiprep, Axis-Shield, Oslo, Norway) step gradients, as previously described (D'Abramo et al, 2005) and quantified by Southern blot against known amounts of genome-length viral DNA.

HEK293T cells maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics were used for packaging lentiviral particles as described at the Addgene web site: http://www.addgene.org/tools/protocols/plko/. Briefly, lentiviruses used to deliver the mutant Tet-ON (rtTA) version of the tetracycline repressor were generated by cotransfecting 293T cells with Addgene plasmid 26730: pLenti CMV rtTA3 Hygro (w785-1) (from Eric Campeau, http://www.addgene.org/26730/) and a packaging system that includes Addgene plasmid 12260: psPAX2 from Didier Trono (https://www.addgene.org/12260), and Addgene plasmid 8454: pCMV-VSV-G (Stewart et al, 2003), using X-tremeGENE 9 DNA transfection reagent (Roche). Infectious particles containing pLV-tetO-NP1 were created using the same packaging system. After 48h, virus-containing supernatants were removed, filtered through a 0.45μM PVDF filter (Millipore), and lentiviral particles were concentrated using Lenti-Xtm Concentrator from Clontech, as described by the manufacturer.

The intermediate A9rtTA3 cell line is a multiclonal population of murine A9 ouabr11 cells constitutively expressing the CMV-driven rtTA3 regulatory protein (Markusic et al, 2005), generated by infection with lentivirus particles carrying pLenti CMV rtTA3 Hygro, obtained from Addgene and selected in medium containing 0.5 mg/ml Hygromycin. The A9-/+NP1 multiclonal cell line, capable of inducibly expressing the HBoV1 NP1 protein under tetracycline control, was created by infecting A9rtTA3 cells with a lentivirus carrying pLV-tetO-NP1 Bleo, and selected with both 0.5 mg/ml Hygromycin and 80 μg/ml Bleomycin. NP1 expression was induced as required by adding the tetracycline analogue doxycycline (Dox) to the media.

NP1 expression and viral infection

A9rtTA3 or A9-/+ NP1 cells were seeded at 25% confluence and mock-induced or induced with Dox at the concentrations and for the times indicated in the text. When indicated, virus infections with wild type or NS2 mutant MVMp where initiated at the time of Dox induction by addition of 10,000 viral genome equivalents per cell (vge/cell) in DMEM containing 1% fetal bovine serum and 20 mM HEPES, plus or minus Dox, under single round of infection conditions (Li L. et al, 2013). Briefly, 4h post infection (pi) viral inocula were removed, and the cultures incubated for 2 h with fresh medium (+/- Dox) containing 0.04 units per ml of neuraminidase (Clostridium perfringens, type V; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to remove surface virus, after which the medium was replaced with fresh neuraminidase-containing medium (+/- Dox) to prevent subsequent re-entry of recycled virus. Cells were harvested with trypsin 24h pi, collected by centrifugation, and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline containing EDTA-free Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Branchburg, NJ). Cells from each plate were divided into aliquots to allow differential processing for viral protein expression and DNA replication, as indicated below.

Western transfers

Cells were suspended in 1x lysis buffer (2%SDS, 10% glycerol, 62.5 mM Tris-HCI, pH 6.8, containing EDTA-free Complete protease inhibitor and Phos STOP, phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche), boiled for 10 min and stored at -80°C. Protein concentrations were determined using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific), and 20 μg aliquots (with added dyes and 100 mM DTT) were boiled for 10 min and loaded onto 4-20 % Mini-Protean TGX gels (Bio-Rad). Separated proteins were transfered electrophoretically to Immuno-Blot polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad), stained with Ponceau Red, and probed with rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against the following: 1) a peptide that corresponds to residues 76 to 91 from HBoV1 NP1; 2) the common N-terminal 84 amino acids shared by MVM NS1 and NS2; 3) a peptide called “allo-p” that recapitulates residues 311 to 327 in MVMp VP2. After incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG, bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence using standard procedures.

Cell cycle distribution and detection of live and dead cells

A9rtTA3 or A9-/+ NP1 cells were induced with Dox concentrations between 0-200 ng/ml and for 24 or 40 hours, as indicated, recovered by trypsinization and washed with cold PBS. For propridium iodide staining, cells were fixed by ethanol addition while vortexing, pelleted, resuspended in PBS containing 0.5 mM EDTA and 1 mg/ml heat inactivated RNAse A (American Bioanalytical) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Propidium iodide (Sigma -P4170) was added to a final concentration of 0.05 mg/ml and samples were analyzed on FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). Cell death was also quantified by flow cytometry, using a LIVE/DEAD Fixable Far Red Dead Cell Staining Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol and analysed by FACSCalibur.

Analysis of duplex viral DNA

Viral DNA was isolated as described previously (Cotmore and Tattersall, 2011). Briefly, cells were harvested with trypsin, resuspended in 10 mM Tris-HCI (pH 7.5) containing 10 mM NaCI and 4% NP-40 and flash frozen. These samples were later extracted by mixing with an equal volume of 50 mM Tris-HCI; 20 mM EDTA; 2% SDS at room temperature, and adjusted to final buffer conditions of 50 mM Tris-HCI; 15 mM EDTA; 0.5 % SDS; 1% NP-40; 200 mM NaCI before addition of proteinase K (to 250 ug/ml). Samples were incubated at 45°C for 2 h, 60°C for 30 min, and gradual cooling to room temperature overnight. DNA was isolated from aliquots of these samples using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and analyzed following electrophoresis through neutral agarose gel by Southern transfer, quantified using a Typhoon Trio variable-mode phosphorimager (GE Healthcare) with ImageQuant software.

Analysis of packaged viral DNA

For analysis of progeny virion DNA, both cells and medium were harvested at 40h pi following growth under single round infection conditions. Briefly, cells were harvested by trypsinization, recombined with the culture medium, which was then pelleted by centrifugation, allowing the clarified medium and cells to be recovered and processed separately. Cell pellets were resuspended in TE 8.7 (50 mM Tris-HCI, 0.5mM EDTA, pH 8.7), virus released by 3 cycles of freezing and thawing, and the extracts clarified by centrifugation. The resulting cell extract and cell-equivalent samples of culture medium were then digested with micrococcal nuclease and proteinase K, and analyzed on denaturing agarose gel as described previously (Farr and Tattersall, 2004).

Recovery of trypsin digested viral particles from culture medium

As described in the previous section, cells were recovered by trypsinization 40h pi and added back into their culture medium. Cells were then pelleted by centrifugation, and the supernate (4.5ml) underlayed with 0.5ml of 15% iodixanol in TE8.7, followed by 0.3ml of 55% iodixanol in PBS containing 5mm potassium chloride and 1mm magnesium chloride (PBSkm), to create two-step iodixanol gradients. These were centrifuged at 35,000 rpm in a Beckman SW50.1 rotor for 6h, and 200ul fractions collected from the bottom of each tube. For test samples, 10ul of fraction 1 from each group was subjected to electrophoresis through a 10% polyacrylamide discontinuous SDS gel, transferred to PVDF membranes and probed with the anti-allo-p antibody, which recognizes a linear sequence present in both VP1 and VP2.

Immunofluorescence microscopy. Assessing APAR bodies maturation

A9-/+ NP1 cells seeded at 20% confluence on Teflon coated spot-slides were induced with Dox and/or infected with virus using the single round infection conditions described previously. Cells were fixed with 2.5 % paraformaldehyde at various times pi, as indicated, permeabilized with 0.1 % Triton X-100, and incubated with a murine monclonal antibody (mAb) CE10 that recognizes NS1 (the kind gift of Carol Astell; Yeung et al,1991), an anti-fibrillarin mAb 72B9 (the kind gift of Susan Baserga; Westendorf et al, 1998), polyclonal rabbit antibodies to nucleolin (Antibody Verify), or rabbit antibodies to HboV1 NP1 residues 76 to 91, followed by DyLight 594 Goat anti mouse IgG or DyLight 488 Goat anti rabbit IgG (BioLegend) and DAPI. Images were acquired using standardized exposures on a Zeiss Imager M2 AX10 epifluorescence microscope fitted with an AxioCamMRm digital camera driven by AxioVision 4. 8. 1 software. To assess APAR body maturation or to score NP1 redistribution to APAR foci, 1000 cells from random camera shots were collected and the nature of the APAR compartment assessed by countingagainst published examples (Ruiz et al, 2011).

Highlights.

Protoparvoviruses and bocaviruses encode ancillary proteins unrelated in protein sequence

Murine cells that inducibly expressed HBoV1 NP1 were infected with an NS2-null MVM mutant

NP1 was recruited to MVM replication foci in NS2-null infections and rescued viral DNA replication

NP1 expression was unable to complement late defects in NS2-null MVM virion production

HBoV1 NP1 therefore complements one essential function of MVM NS2

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants CA029303 and AI026109 from the National Institutes of Health. The flow cytometry core facility used in this publication was supported, in part, by CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR000142 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adeyemi RO, Landry S, Davis ME, Weitzman MD, Pintel DJ. Parvovirus minute virus of mice induces a DNA damage response that facilitates viral replication. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001141. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeyemi RO, Pintel DJ. The ATR signaling pathway is disabled during infection by the parvovirus minute virus of mice. J Virol JVI.01412-14. 2014a doi: 10.1128/JVI.01412-14. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeyemi RO, Pintel DJ. Parvovirus-induced depletion of cyclin B1 prevents mitotic entry of infected cells. PLoS Pathog. 2014b Jan;10(1):e1003891. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allander T, Tammi MT, Eriksson M, Bjerkner A, Tiveljung-Lindell A, Andersson B. Cloning of a human parvovirus by molecular screening of respiratory tract samples. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12891–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504666102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agbandje-McKenna M, Kleinschmidt J. AAV capsid structure and cell interactions. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;807:47–92. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-370-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berns KI, Parrish CR. In: Parvoviridae, in Fields Virology. 6th. Knipe DM, Howley P, editors. Lippincot Williams and Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bodendorf U, Cziepluch C, Jauniaux J, Rommelaere J, Salome N. Nuclear export factor CRM1 interacts with nonstructural proteins NS2 from parvovirus minute virus of mice. J Virol. 1999;73:7769–7779. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.9.7769-7779.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockhaus K, Plaza S, Pintel DJ, Rommelaere J, Salome N. Nonstructural proteins NS2 of minute virus of mice associate in vivo with 14-3-3 protein family members. J Virol. 1996;70:7527–7534. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7527-7534.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AY, Cheng F, Lou S, Luo Y, Liu Z, Delwart E, Pintel DJ, Qiu J. Characterization of the gene expression profile of human bocavirus. Virology. 2010;403:145–54. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi EY, Newman AE, Burger L, Pintel D. Replication of Minute Virus of Mice DNA Is critically dependent on accumulated levels of NS2. J Virol. 2005;79:12375–81. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.19.12375-12381.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotmore SF, Tattersall P. Alternate splicing in a parvoviral nonstructural gene links a common amino-terminal sequence to downstream domains, which confer radically different localization and turnover characteristics. Virology. 1990;177:477–487. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90512-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotmore SF, D'Abramo AM, Carbonell LF, Bratton J, Tattersall P. The NS2 polypeptide of parvovirus MVM is required for capsid assembly in murine cells. Virology. 1997;231:267–280. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotmore SF, Tattersall P. Mutations at the base of the icosahedral five-fold cylinders of minute virus of mice induce 3′-to-5′ genome uncoating and critically impair entry functions. J Virol. 2011;86:69–80. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06119-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotmore SF, Tattersall P. Parvovirus diversity and DNA damage responses. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2013 Feb 1;5(2) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012989. pii: a012989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotmore SF, Agbandje-McKenna M, Chiorini JA, Mukha DV, Pintel DJ, Qiu J, Soderlund-Venermo M, Tattersall P, Tijssen P, Gatherer D, Davison AJ. The family Parvoviridae. Arch Virol. 2013;159:1239–47. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1914-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cziepluch C, Lampel S, Grewenig A, Grund C, Lichter P, Rommelaere J. H-1 parvovirus-associated replication bodies: A distinct virus-induced nuclear structure. J Virol. 2000;74:4807–4815. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.10.4807-4815.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Abramo AM, Ali AA, Wang F, Cotmore SF, Tattersall P. Host range mutants of minute virus of mice with a single amino acid change require additional silent mutations that regulate NS2 accumulation. Virology. 2005;340:143–154. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFilippis RA, Goodwin EC, Wu L, DiMaio D. Endogenous human papillomavirus E6 and E7 proteins differentially regulate proliferation, senescence, and apoptosis in HeLa cervical carcinoma cells. J Virol. 2003;77:1551–63. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1551-1563.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, Yan Z, Luo Y, Xu J, Cheng F, Li Y, Engelhardt JF, Qiu J. In vitro modeling of human bocavirus 1 infection of polarized primary human airway epithelia. J Virol. 2013;87:4097. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03132-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichwald V, Daeffler L, Klein M, Rommelaere J, Salome N. The NS2 proteins of parvovirus minute virus of mice are required for efficient nuclear egress of progeny virions in mouse cells. J Virol. 2002;76:10307–10319. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10307-10319.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelsma D, Valle N, Fish A, Salome N, Almendral JM, Fornerod M. A supraphysiological nuclear export signal is required for parvovirus nuclear export. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:2544–2552. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-01-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr GA, Tattersall P. A conserved leucine that constricts the pore through the capsid fivefold cylinder plays a central role in parvoviral infection. Virology. 2004;323:243–256. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr GA, Cotmore SF, Tattersall P. VP2 cleavage and the leucine ring at the base of the fivefold cylinder control pH-dependent externalization of both the VP1 N terminus and the genome of minute virus of mice. J Virol. 2006;80:161–71. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.1.161-171.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gersappe A, Burger L, Pintel DJ. A premature termination codon in either exon of minute virus of mice P4 promoter-generated pre-mRNA can inhibit nuclear splicing of the intervening intron in an open reading frame-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22452–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder S, Ng R, Agbandje-McKenna M. Parvoviruses: structure and infection. Future Virol. 2012;7:253–78. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q, Deng X, Yan Z, Cheng F, Luo Y, Shen W, Lei- Butters DCM, Chen AY, Li Y, Tang L, Söderlund-Venermo M, Engelhardt JF, Qiu J. Establishment of a reverse genetic system for studying human bocavirus in human airway epithelia. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002899. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihalainen TO, Niskanen EA, Jylhävä J, Paloheimo O, Dross N, Smolander H, Langowski J, Timonen J, Vihinen-Ranta M. Parvovirus induced alterations in nuclear architecture and dynamics. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihalainen TO, Niskanen EA, Jylhävä J, Turpeinen T, Rinne J, Timonen J, Vihinen-Ranta M. Dynamics and interactions of parvoviral NS1 protein in the nucleus. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9:1946–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederman M, Patton JT, Stout ER, Bates RC. Virally coded noncapsid protein associated with bovine parvovirus infection. J Virol. 1984;49:315–8. doi: 10.1128/jvi.49.2.315-318.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Zhang Z, Zheng Z, Ke X, Luo H, Hu Q, Wang H. Identification and characterization of complex dual nuclear localization signals in human bocavirus NP1. J Gen Virol. 2013;94:1335–1342. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.047530-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Cotmore SF, Tattersall P. Maintenance of the flip sequence orientation of the ears in the parvoviral left-end hairpin is a nonessential consequence of the critical asymmetry in the hairpin stem. J Virol. 2012;86:12187–12197. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01450-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Bueno A, Valle N, Gallego JM, Pérez J, Almendral JM. Enhanced cytoplasmic sequestration of the nuclear export receptor CRM1 by NS2 mutations developed in the host regulates parvovirus fitness. J Virol. 2004;78:10674–84. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10674-10684.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Chen AY, Qiu J. Bocavirus infection induces a DNA damage response that facilitates viral DNA replication and mediates cell death. J Virol. 2011;85:133–45. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01534-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Deng X, Cheng F, Li Y, Qiu J. SMC1-mediated intra-S-phase arrest facilitates bocavirus DNA replication. J Virol. 2013;87:4017–32. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03396-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markusic D, Oude-Elferinc R, Das AT, Berkhout B, Seppen J. Comparison of single regulated lentiviral vectors with rtTA expression driven by an autoregulatory loop or a constitutive promoter. Nuc Acids Res. 2005;33:e63. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattei LM, Cotmore SF, Tattersall P, Iwasaki A. Parvovirus evades interferon- dependent viral control in primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Virology. 2013;442:20–27. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CL, Pintel DJ. The NS2 protein generated by the parvovirus minute virus of mice is degraded by the proteasome in a manner independent of ubiquitin chain elongation or activation. Virology. 2001;285:346–55. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CL, Pintel DJ. Interaction between parvovirus NS2 protein and nuclear export factor Crm1 is important for viral egress from the nucleus of murine cells. J Virol. 2002;76:3257–3266. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.7.3257-3266.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan WR, Ward DC. Three splicing patterns are used to excise the small intron common to all minute virus of mice RNAs. J Virol. 1986;60:1170–1174. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.3.1170-1174.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumer M, Sonntag F, Schmidt K, Nieto K, Panke C, Davey NE, Popa-Wagner R, Kleinschmidt JA. Properties of the adeno-associated virus assembly-activating protein. J Virol. 2012;86:13038–48. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01675-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neager LK, Cater J, Pintel DJ. The small nonstructural protein (NS2) of the parvovirus minute virus of mice is required for efficient DNA replication and infectious virus production in a cell- type-specific manner. J Virol. 1990;64:6166–6175. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.12.6166-6175.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neager LK, Salome N, Pintel DJ. NS2 is required for efficient translation of viral mRNA in minute virus of mice-infected murine cells. J Virol. 1993;67:1034–1043. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.1034-1043.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuesch JPF. Regulation of non-structural protein functions by differential synthesis, modification and trafficking. Chapter 19. In: Kerr J, Cotmore SF, Bloom ME, Linden RM, Parish CR, editors. Parvoviruses. Hodder Arnold; London: 2005. pp. 275–289. [Google Scholar]

- Ohshima T, Nakajiama T, Oishi T, Imamoto N, Yoneda Y, Fukamizu A, Yagami K. CRM1 mediates nuclear export of nonstructural protein 2 from parvovirus minute virus of mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;264:144–150. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Z, D'Abramo A, Tattersall P. Differential roles for the C-terminal hexapeptide of NS2 splice variants during MVM infection of murine cells. Virology. 2006;349:382–395. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Z, Mihaylov IS, Cotmore SF, Tattersall P. Recruitment of DNA replication and damage response proteins to viral replication centers during infection with NS2 mutants of Minute Virus of Mice (MVM) Virology. 2011;410:375–84. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag F, Schmidt K, Kleinschmidt JA. A viral assembly factor promotes AAV2 capsid formation in the nucleolus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:10220–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001673107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadtfeld M, Maherali N, Breault D, Hochedlinger K. Defining molecular cornerstones during fibroblast to iPS cell reprogramming in mouse. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:230–240. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SA, Dykxhoorn DM, Palliser D, Mizuno H, Yu EY, An DS, Sabatini DM, Chen IS, Hahn WC, Sharp PA, Weinberg RA, Novina CD. Lentivirus-delivered stable gene silencing by RNAi in primary cells. RNA. 2003;4:493–501. doi: 10.1261/rna.2192803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhu L, Fasina O, Burger L, Rai A, Qiu J, Pintel DJ. Characterization of the nonstructural proteins of the bocavirus minute virus of canines. J Virol. 2013;87:1098–104. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02627-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B, Cai Y, Li Y, Li J, Liu K, Li Y, Yang Y. The nonstructural protein NP1 of human bocavirus 1 induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in Hela cells. Virology. 2013;440:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.02.013. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Chen AY, Cheng F, Guan W, Johnson FB, Qiu J. Molecular characterization of infectious clones of the minute virus of canines reveals unique features of bocaviruses. J Virol. 2009;83:3956–67. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02569-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerndorf JM, Konstantinov KN, Wormsley S, Shu MD, Matsumoto-Taniura N, Pirollet F, Klier FG, Gerace L, Baserga SJ. M phase phosphoprotein 10 is a human U3 small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein component. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;9:437–49. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.2.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung DE, Brown GW, Ta P, Russnak RH, Wilson G, Clark-Lewis I, Astell CR. Monoclonal antibodies to the major nonstructural nuclear protein of minute virus of mice. Virology. 1991;181:35–45. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90467-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zadori Z, Szelei J, Tijssen P. SAT: a late NS protein of porcine parvovirus. J Virol. 2005;79:13129–38. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.20.13129-13138.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taxonomy of the family Parvoviridae. http://talk.ictvonline.org/files/ictv_official_taxonomy_updates_since_the_8th_report/m/vertebrate-official/4844.aspx.