Introduction

In the decade since the Human Genome Project was completed, the knowledge and technologies that this project enabled have led to a remarkable evolution in the way biorepositories are designed and operate. Early biobanks were often designed to facilitate the study of a single condition, while biobanks established in the last decade have more frequently been created with a broader research mission in mind.1 Accompanying this transition have come other changes in biobank practices, including the generation and storage of genome-scale sequencing data, frequent sharing of biosamples and data, pooling of resources among sample collections, and increased interest in returning genetic research results to sample donors.

As biorepository practices have become more complex, the task of developing appropriate informed consent practices has become more challenging. There are at least three reasons for this. First, the regulations that govern research with human subjects in the U.S., known collectively as the Common Rule, were written at a time when many of the recent innovations in biobank practices were not anticipated. Second, Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) are tasked with evaluating whether research studies meet both federal regulations and local standards for acceptable research, yet IRB members are often unfamiliar with the complexities of biobanks. Third, it can be quite challenging to explain these practices in informed consent documents in a way that is easy for potential research participants to read and understand.

Because of these challenges, several groups have developed practical guidance on informed consent. For example, the website of the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), Genome.gov, provides model informed consent language developed for genomic research studies, including biobanks.2 The NHGRI website also hosts a white paper developed by our group, the Electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE) Network.3 This document provides model language for informed consent documents that investigators may adapt for their own biorepository projects.

One limitation of these resources, however, is their focus on adult research participants. There are currently no similar resources that address the unique issues that arise for biorepositories that aim to collect samples from pediatric participants. This is an important gap in the literature, since the challenges associated with biobanking are magnified in the setting of pediatric research. The ability of children to engage in informed decision-making varies according to their developmental level, so parental permission is usually required for pediatric research participation. However, a parent’s permission for a child to participate in research is quite different from an adult’s consent for his or her own research participation. A parent’s decision must account for the best interests of the child, while at the same time balancing the future autonomy of the child and the needs of the family.

To be sure, there is a robust literature on these unique issues that arise in pediatric research,4,5 including a number of helpful papers that address pediatric biorepositories specifically.6,7 However, it can be difficult for investigators and IRB members to distill these empirical and analytical resources into concrete practices related to the informed consent process. This document is designed to address that need. Writing on behalf of the Consent, Education, Regulation, and Consultation (CERC) workgroup of the eMERGE Network, we provide pediatric-focused guidance for investigators and IRB members working in the U.S regulatory context on pediatric informed consent practices for biorepositories.

Methods

Investigators from eight eMERGE sites, including seven sites with direct experience obtaining informed consent for the inclusion of pediatric samples in biorepositories, collaborated on this project. The eMERGE Network is comprised of sites who have developed prospective biobanks that are linked with data derived from electronic health records. In order to collect the experience of these sites, investigators sent the first author (KB) IRB-approved informed consent and assent documents that were in active use for eMERGE-affiliated biorepositories during 2012, along with any ancillary protocols or documentation related to pediatric consent. In all, investigators submitted documents related to nine projects (one institution submitted documents relating to three independent biobanking projects).

The research team then conducted a qualitative, thematic analysis of the documents. Themes were developed through an iterative process that involved review of conceptual literature on pediatric issues in biobanking, discussion on site-specific experiences, and review and close reading of the available consent and assent documents. The full author team reached consensus on seven themes relevant to pediatric biobanking: permission from parents, assent from minors, co-consent from older adolescents, data sharing, return of results, recontacting participants, and retention of samples after the age of majority.

Codes were then developed for each theme through an iterative process that involved individual review of consent and assent documents, collation of proposed codes, and group discussion to reach consensus. Codes fell into two general categories. First, codes were developed to record whether each thematic issue was addressed in a given consent or assent document. For example, one code was developed to tag consent documents that explicitly mentioned data-sharing. A parallel set of codes recorded how those thematic issues were operationalized in the language of consent and assent documents. For example, the language mentioning data-sharing was categorized using a set of codes specifying which recipients of shared data were explicitly mentioned.

These codes were structured into a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database that was used to summarize the characteristics of each consent and assent document. The first author performed the initial coding for all documents, and at least one of the investigators from each site reviewed these codes for accuracy. All disagreements were resolved by consensus between the first author and local site representatives, followed by a final review and consensus approval of the aggregate coding by the entire research team.

The research team then used investigator triangulation to analyze the results of the coding.8 Specifically, team members reviewed the aggregate results of the coding in order to identify potential conclusions about the results that could provide guidance for the development of future consent and assent documents. These initial conclusions were then refined through a process involving discussion on specific site experiences, review of available literature on related ethics or compliance issues, and analysis of relevant ethical or regulatory concepts. This triangulation process occurred over several conference calls and led to a final consensus on guidance for each of the ethical and regulatory issues reflected in the thematic coding.

Overarching Themes

Two overarching themes emerged as important to nearly every issue we examined: the evolving roles of parents and children in making decisions related to research participation as children mature, and the role of the IRB.

The Roles of the Parent(s) and Child

In broad terms, the Common Rule requires that the permission to enroll a minor in a research study must come from his or her parent or guardian. From a compliance perspective, minors cannot give consent until they reach the age of majority, which is usually eighteen years of age. At the same time, it is clear that children do not suddenly become fully mature adults at this age. The ability of children to participate in decisions, including those related to research participation, develops over a period of time with significant variation in its timing from child to child. From an ethics perspective, then, it is favorable to engage each child in the informed consent process in a way that is responsive to his or her current state of development. Legal authorization to participate still must come from a parent or guardian, but the duty to inform a child and to respect his or her concerns and preferences must be respected in proportion to his or her developing autonomy. The Common Rule requires that a child assent to research participation unless it can be appropriately waived or the child is not capable of providing it. This tension between the legal status of a minor and the duty to respect his or her developing ability to engage in an assent process is a key issue that informs every piece of guidance addressed in this document.

The Role of the IRB

The second overarching theme that emerged in our work was the important role IRBs play in decisions about the participation of children in biobanks. The guidance provided in this document is informed by our own experiences as investigators working with local IRBs to develop assent, consent, and parental permission procedures for biorepositories at each of the eight participating eMERGE institutions. While our experiences with our local IRBs varied significantly, we were able to identify a number of commonalities. For example, IRBs at the eMERGE sites often provided investigators with guidelines on pediatric-specific research issues, including specific age cutoffs for asking children to provide assent. Local IRBs also often required that certain blocks of language be included in every consent document. Some eMERGE investigators found these guidelines frustrating, since local IRB guidelines may differ from standards adopted elsewhere. More importantly, some investigators may desire to adopt practices that are more nuanced or more individualized than those recommended by the IRB.

This document is designed, in part, to address these challenges. In our experience IRB professionals and committee members are often responsive to respectful discussions about best practices related to informed consent, assent, and parental permission. We believe these discussions can be facilitated by practical guidance that reflects the practices of other institutions and the most up-to-date thinking about research ethics and compliance issues. While we anticipate that institutions will continue to find good reasons for doing things differently from the approach we propose here, we hope that this document will serve as a starting point for thoughtful local discussions on how best to protect children while developing biorepositories that could provide significant scientific utility.

Guidance

In the sections that follow, we present guidance on a number of pediatric-specific consent issues that arise frequently in the development of biorepositories. Because biorepository designs and local conditions vary, we have endeavored to provide broad guidance that is applicable in as many contexts as possible. Each piece of guidance is accompanied by a summary of the experiences of the eMERGE sites followed by a discussion of key issues.

Assent, Co-Consent, and Parental Permission

Guidance: Permission from one parent is adequate for a child’s participation in a biorepository

eMERGE Experience

All nine eMERGE projects examined by our group required the permission of only one parent.

Discussion

The Common Rule requires consent from both parents when the research planned is not expected to provide direct benefit to participating children, but confers a greater than minimal risk to them.9 Such studies are not generally allowed unless they are (1) likely to yield generalizable knowledge about the individual participant’s condition or (2) present an opportunity to “understand, prevent, or alleviate a serious problem affecting the health or welfare of children.”9 Studies of both types require the permission of both parents unless the child has just one parent or legal guardian.

The primary risk faced by biorepository participants is the disclosure of their private information to others. This risk is generally classified as minimal since it is similar to that encountered in routine clinical care. The return of genomic results may create additional risks for participants, but results should usually only be returned if they also carry the potential to provide direct benefit for participants. Given these features of biorepositories, the Common Rule allows the enrollment of pediatric participants with permission from just one parent. An ethical analysis supports this conclusion, since a requirement for permission from both parents is likely to hinder enrollment while providing no substantive improvement in the quality of the informed consent.4

Guidance: Developmentally appropriate explanations about biorepository participation are recommended for all children

eMERGE Experience

The projects analyzed by our working group depend primarily on the verbal explanations of study personnel adapted to the child’s developmental level, with all nine projects utilizing this approach. Seven projects also utilize assent documents which provide brief written information. None of the eMERGE projects examined use additional written materials such as pamphlets or multimedia tools to explain research procedures for children.

Discussion

Even children who are not being asked to provide assent deserve a developmentally appropriate explanation about the research process. The amount of information and level of detail used to describe participation in a biobank should be based primarily on a child’s developmental level,10 as assessed by the study personnel conducting the assent process. This assessment can be based on both input from the child’s parent or guardian and preliminary conversations with the child.

Children at earlier stages of development should at minimum receive an explanation about study procedures such as the blood draw or buccal swab. More mature children should receive a brief description of the aims of the biobank. Adolescents whose developmental level approaches that of young adults should receive essentially the same information as their parents.

These explanations can be provided in a range of formats, including verbal explanations, demonstrations by child-life experts, and written descriptions. When used, assent documents should be written at an appropriate readability level, but even then such language is only a starting point. Additional resources such as videos, comic books, or interactive websites may help to provide developmentally appropriate descriptions for children and adolescents enrolling in a biorepository. Since evidence on the effectiveness of these tools is currently incomplete, this is an area ripe for examination and empirical study in the setting of pediatric biobanks. We believe that, for the present, multimedia tools should be used primarily to facilitate interpersonal engagement and not replace it.

Guidance: In addition to developmentally appropriate explanations, some children should also be asked to provide assent. Requests for assent are appropriate once participants reach the developmental level similar to that of a typically-developing 7 to 10 year old, or when parents report that the child is mature enough to understand and participate in this process

eMERGE Experience

All nine eMERGE projects utilize assent in some form, with most using local guidelines based on age rather than developmental level. The starting age for requesting assent ranges from 7 to 12 years of age. Two projects require written assent, and two require only verbal assent. Five allow the use of either written or verbal assent, depending on the circumstances (i.e. the child’s developmental level). Written assent documents range from about 200 to 1200 words in length.

Discussion

Local IRBs often set guidelines for the use of verbal or written assent, and usually specify an age range for assent. However, we recommend going beyond chronologic age. Study personnel obtaining assent should consider each child’s developmental stage and cognitive ability to ensure that both explanations and the use of assent procedures are appropriate.11 These personnel should be trained to make a decision about when assent should be elicited based on observations or conversations with the child and the input of the parent or guardian, and to document their decision and rationale. In general, either written or verbal assent could be appropriate for biobank participation, depending on the child’s developmental level. Whenever a child’s assent is needed for enrollment, his or her choice to dissent should be respected. These issues are not significantly different from other types of research, so general resources on research assent and dissent can be helpful in this setting.4,12

Guidance: It may be advisable to engage more mature adolescents in a “co-consent” process rather than an assent process. This approach would be appropriate for adolescents who have reached a developmental level comparable to that of a typical 14 year old

eMERGE Experience

One project analyzed in our study provides a signature line on the consent document for older adolescents who are being asked to provide “co-consent.” Permission from a parent is also required.

Discussion

Adolescents in their late teen years are often mature enough to engage in “consent-like” conversations and to consider the risks and benefits of participation in the same way an adult would. Even though these young people are not legally authorized in most circumstances to provide consent for their research participation, from an ethical perspective it is appropriate to focus the informed consent process as much on the adolescents’ deliberative process as on their parent’s. This approach has several advantages. First, it reflects respect for the adolescent’s emerging autonomy.13 Second, the preferences expressed by a mature adolescent may provide guidance on how to manage her sample should investigators not be able to recontact her when she reaches the age of majority. We discuss this second issue below.

Data Sharing

Guidance: The sharing of de-identified data is inherent in the scientific aims of biorepositories and is considered appropriate for pediatric biobanks. Potential participants should be provided with a general explanation of any plans to share samples or data, including the associated risks and benefits

eMERGE Experience

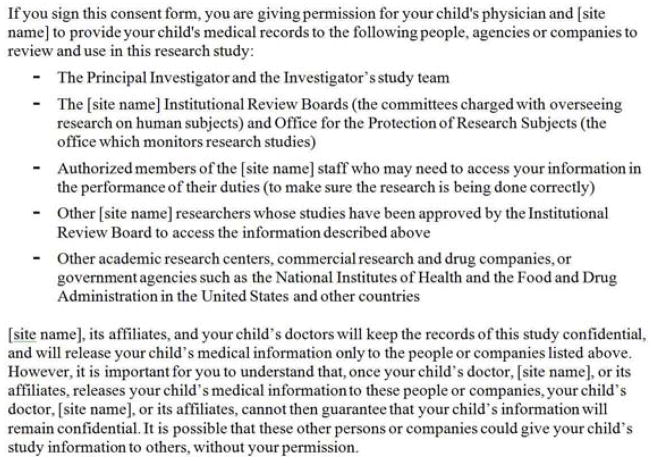

The data-sharing experiences of the eMERGE sites has been described in detail in a previous publication.14 Pediatric-specific consent documents from all nine eMERGE projects mention data-sharing. Four of these mention that data could be shared with both national databases, such as dbGaP, and with other research institutions (an example is provided in Figure 1). The consent documents from two projects mention only national databases as potential recipients of data, and one project’s consent document mentions only other research institutions as potential recipients. The consent documents for two projects ask parents to choose whether they wish for their child’s data to be shared.

Figure 1.

Explanation of data-sharing policy from the informed consent document for Project 9.

Discussion

The distinctions among identifying data, de-identified data, and anonymous data are key to the issue of data-sharing. In the U.S., most institutional biobanks retain data with identifiers but only share de-identified data. This is because the Privacy Rule portion of the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) restricts the distribution of identifying health information. The Privacy Rule does allow de-identified data to be shared and specifies the criteria that must be met in order for data to be considered de-identified for these purposes.15 Some research data, such as genetic markers, is clearly not anonymous even if it is de-identified according to the Privacy Rule.

Once de-identified data is shared outside the original institution it is not usually possible to retract it, even if the parent, or later the young adult who had participated in research as a child, wishes to withdraw from the biobank. One group of commentators has argued that for this reason, and because shared genetic data is not anonymous, data collected from children for population-based biobanks should not be shared until the child reaches adulthood and consents to data-sharing.16 While we agree that the genetic information of minors deserves careful protection, we do not agree that this protection needs to involve a delay in sharing data. There are numerous other ways to protect the confidentiality of pediatric participants, including through the use of data-use agreements and proper security measures.17 In addition, such constraints undermine the future health benefits for children that motivate the creation of biobanks.

Retaining Data and Samples Beyond the Age of Majority

Guidance: Each pediatric biorepository should develop a policy for how data and samples will be handled once a pediatric participant reaches the age of majority, and explain this policy in its consent document

eMERGE Experience

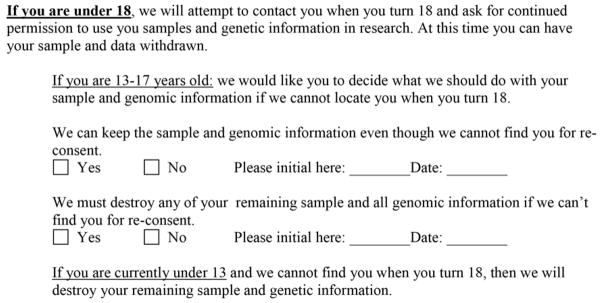

The policies of all nine eMERGE projects allow for data and samples to be retained once participants reach the age of majority. One project de-identifies all samples and data making re-contact potentially unnecessary. The remaining eight projects will attempt to re-contact participants when they reach the age of majority. These projects differ in their policies regarding participants who cannot be reached. Six projects plan to de-identify data from such participants, while one site plans to destroy their data. One project permits older adolescents to choose whether they wish for their samples to be de-identified or destroyed if they cannot be reached (Figure 2). Eight of the nine projects explain their retention policies in their consent documents.

Figure 2.

Options for retaining samples after participant reaches the age of majority from the informed consent document of Project 7.

Discussion

Generally speaking, there are at least two decisions that biobanks need to make when it comes to developing a policy for the management of data and samples from participants who have reached the age of majority. They must first decide whether the biorepository will attempt to recontact young adults in order to obtain their consent to continued use of data and samples. Recontact is preferable in many circumstances, since this approach affirms the importance of first-person consent. However, this principle must be balanced with the feasibility and cost of such an effort. For example, recontact would probably not be required, either from an ethical or a compliance perspective, in cases where a biorepository had so many participants that recontacting them would be unfeasible.

Since it is inevitable with either policy that at least some participants will not be reached, biobanks must also decide how to handle data and samples from participants who are not recontacted. In our sample, the most common policy is to de-identify data and samples from participants who are not recontacted. We believe this approach is relatively uncontroversial, especially since the Office of Human Research Protections has released a guidance document clarifying that research with de-identified data and samples is considered non-human subjects research and does not require informed consent.18 This approach is also likely to be acceptable to most biobank participants.19

There are other options, however. In certain circumstances, identified data may be used for research even if the participant cannot be contacted. Even though the use of identified data for research generally requires explicit informed consent, the Common Rule allows IRBs to waive this requirement in specific circumstances, such as when “the research could not practicably be carried out without the waiver.”20 In order to meet this criterion, biobanks would need to demonstrate to the IRB that the scientific aims of the biobank can be achieved only if data and samples remain associated with identifiers.

A final option is to destroy the biosamples and research data collected from participants who cannot be reached when they reach the age of majority. This approach was required by the IRB at one of our sites. We do not recommend this approach, however, because it is likely to compromise the scientific aims of any pediatric biobank that is unable to recontact a large proportion of its participants and because other privacy protections are available. As we observed earlier, less restrictive approaches to protecting participants’ privacy are well received by most biobank participants.19

Return of Genetic Research Results

Guidance: Given the wide range of biorepository designs, scientific aims, and institutional capacities, and in light of the current lack of professional consensus about whether and how to return genetic research results, it is acceptable for a biorepository to return results or to not return results to pediatric participants and their parents

eMERGE Experience

Of the nine projects included in our analysis, two do not mention return of results in the consent document, two state that results will not be returned to participants, and five state that research results might be returned to participants. The assent document for only one project mentions return of research results; this document is from one of the sites that does not plan to return results. The relevant language from each of these consent documents, and one assent document, is listed in the Supplementary Table. Among the five projects returning results, the details provided in the consent document vary widely. Three projects provide relatively brief information focused on informing participants that they may be contacted if a useful genetic result is identified. Two projects provide more detailed information, including information on how returnable results will be identified and how results will be communicated to participants. None of the projects we reviewed include the explicit criteria that will be used for evaluating whether a result should be returned. The two projects that provide detailed information instead focus on the procedure that will be used to review results and identify which will be returned, including a description of the committee that will make such decisions.

Discussion

Biorepositories raise a distinctive set of challenges for returning genetic research results to participants. For example, research performed using biorepository data is often conducted by investigators far removed from the participants themselves. For this reason, it can be difficult for investigators to evaluate whether a participant would want to know a result. Similarly, research with children raises its own distinctive set of challenges for returning research results. Consider, for example, that a current policy statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) advises against testing children for certain adult-onset genetic conditions, a policy relevant to deciding which genetic research results should be considered for return to a pediatric research participant.21–23 In contrast, a policy statement from a different committee of the ACMG proposes that potential benefit to parents is a compelling reason to return incidental findings for certain adult-onset conditions.23,24 It is clear, then, that the already complex issue of whether and when to return research results is made even more complex in the setting of pediatric biobanking.

The current iteration of the eMERGE Network was designed, in part, to explore how research results generated through biorepositories could be returned to participants and their medical providers. Institutions both interested and equipped to address the relevant challenges are overrepresented in our group. We recognize, however, that not all institutions pursuing the development of a biorepository will be interested in, or capable of, returning research results. In fact, it is possible that at some institutions the development of an otherwise valuable biorepository could be significantly impeded if an infrastructure for returning research results were required.

Given this set of considerations, we consider it acceptable for pediatric biobanks to be designed to return results or to not return results, although we acknowledge that there is no consensus on this matter.25–28 Institutions considering the development of a biobank that will include samples from children should carefully consider the potential benefits and opportunity costs associated with returning results, and develop a policy that is acceptable to local stakeholders. Whatever the policy developed, it is important that parents being asked to consent to their child’s participation be provided with a clear and understandable explanation of these plans.

Guidance: Biobanks choosing to return results should take individual participant preferences into account. These preferences may be elicited at the time of informed consent and/or during a later interaction. When an adolescent is mature enough to weigh the relevant risks and benefits, most results should only be returned when both the adolescent and his or her parents agree that they want to receive it

eMERGE Experience

Of the five consent documents that state results could be returned, two ask parents to record a preference about receiving research results. In both cases the consent document asks the parent only to accept or decline potential return of results, but both mention later opportunities to accept or decline specific results. None of the assent or consent documents directly elicit the preferences of the pediatric participant. However, one project describes a website that will allow children 13–17 years of age to set their preferences for return of research results along with their parents.29 Although not described in its consent document, this project plans to return results only when both the adolescent and the parent agree to receive the result.

Discussion

The classification of results as “returnable” should be based on the consensus of national and local experts, as well as the priorities and resources of the local biorepository. The decision to actually return such a result to an individual participant, however, should be based whenever possible on the participant’s preferences. Ideally, these preferences will be elicited prospectively. For example, some biorepositories utilize online tools that allow participants to record and change their preferences over time.29,30 Others simply ask participants to record an “all or nothing” preference at the time of enrollment.

The challenge of eliciting participant preferences is particularly complex in the setting of pediatric biobanks because investigators must account for both the preferences of the parent and those of the pediatric participant.31 When it comes to decisions about receiving results for less-mature children, the parent’s preferences are determinative. Due to the complex issues and discussions surrounding returning results, it would be inappropriate to ask the children for their preferences until they are mature enough to understand the relevant implications. When a child is mature enough to weigh the risks and benefits of receiving research results, however, his or her preferences and those of the parent should both be elicited.

When both preferences are elicited, conflicts are inevitable. When an adolescent is mature enough to weigh the risks and benefits of receiving research results, the adolescent’s preferences should be taken into account, and may even outweigh the parent’s preferences. In most cases, however, it would still be advisable to return a result only when both the parent and the adolescent agree that the result is wanted.26

The authors of a recent recommendation document from the ACMG argued that in the setting of clinical testing certain secondary findings should be returned even if the patient or parent have declined to receive this information.24 However, this particular recommendation was met with significant opposition,32–35 and was recently withdrawn by the ACMG.36 In addition, ethically relevant differences exist between research and clinical care. In light of this, it remains unresolved whether there are circumstances when research results should be returned when either the parent or the adolescent have declined to receive them.

Limitations

Our group reflects the experiences of a relatively small number of sites. We acknowledge that our experience may not be representative of other investigators who have worked with IRBs and other stakeholders on local biorepositories. We also expect that some experts will interpret the relevant issues differently. Given these limitations, we have declined to label these proposals as “recommendations” or even “guidelines,” but instead consider our proposal to provide “guidance.” We believe our guidance carries the limited authority that arises from our real-world experience implementing biorepositories in diverse institutions across the country.

Conclusions

We hope this guidance, based on the experience of nine biobanks at eMERGE sites, will facilitate the collaborative work of local stakeholders, including investigators and IRB members, seeking to develop effective informed consent processes for new pediatric biobanks. Through this work, stakeholders have the opportunity not only to contribute to new discoveries in pediatrics, but also to help find better solutions to the challenges we have discussed. As this guidance document demonstrates, much work remains. A remarkable amount of diversity remains in the way biobanks handle samples from participants who have reached the age of majority, and significant debate remains on how best to return genomic research results, if at all.

Fortunately, each new institution that pursues the development of a pediatric biobank will generate its own experience with addressing these challenges. We encourage these sites to engage in conversations with their local stakeholders and share their experiences through public venues. The more such experiences are shared, as we have done in this article, the closer we will come to realizing consensus on many of these difficult issues. Perhaps one day we will even be able to agree on best practices. For now, our challenge is to continue our work to find consent procedures that make discovering new knowledge possible, while at the same addressing the practical needs of pediatric participants and their families and protecting the privacy and developing autonomy of pediatric participants.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table: Language describing plans related to returning research results from seven eMERGE projects.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ingrid Holm and Maureen Smith, who co-chair the Consent, Education, Regulation and Consultation (CERC) Workgroup of the eMERGE Network, of which this manuscript is a product. We would also like to thank Rosetta Chiavacci, Nicole Lockhart, and Paul Croarkin who contributed to this project, as well as Brandy Mapes, Lauren Melancon, and Andy Faucett. The eMERGE Network was initiated and funded by NHGRI through the following grants: U01HG006828 (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center/Boston Children’s Hospital); U01HG006830 (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia); U01HG006389 (Essentia Institute of Rural Health); U01HG006382 (Geisinger Clinic); U01HG006375 (Group Health Cooperative); U01HG006379 (Mayo Clinic); U01HG006380 (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai); U01HG006388 (Northwestern University); U01HG006378 (Vanderbilt University); and U01HG006385 (Vanderbilt University serving as the Coordinating Center).

Abbreviations

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- ACMG

American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics

- CERC

Consent, Education, Regulation, and Consultation

- dbGAP

Database of Genotypes and Phenotypes

- eMERGE

Electronic Medical Records and Genomics Network

- HIPAA

Health Information Portability and Accountability Act

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- NHGRI

National Human Genome Research Institute

- REDCap

Research Electronic Data Capture

Footnotes

Disclosure:

The authors report that they have no commercial association or other financial interest that might pose or create a conflict of interest with information presented in this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Henderson GE, Cadigan RJ, Edwards TP, et al. Characterizing biobank organizations in the U.S.: results from a national survey. Genome medicine. 2013 Jan 25;5(1):3. doi: 10.1186/gm407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. [Accessed July 2, 2013];Informed Consent Elements Tailored to Genomics Research. http://www.genome.gov/27026589.

- 3.Beskow LM, Clayton EW, Eisenberg L, et al. Model Consent Language. The Electronic Medical Records and Genomics (eMERGE) Network Consent & Community Consultation Workgroup Informed Consent Task Force; 2009. pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross LF. Informed consent in pediatric research. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics. 2004 Fall;13(4):346–358. doi: 10.1017/s0963180104134063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wendler DS. Assent in paediatric research: theoretical and practical considerations. Journal of medical ethics. 2006;32(4):229–234. doi: 10.1136/jme.2004.011114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hens K, Nys H, Cassiman JJ, Dierickx K. Biological sample collections from minors for genetic research: a systematic review of guidelines and position papers. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2009 Aug;17(8):979–990. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hens K, Van El CE, Borry P, et al. Developing a policy for paediatric biobanks: principles for good practice. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2013 Jan;21(1):2–7. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denzin NK. The research act in sociology: a theoretical introduction to sociological methods. London: Butterworths; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Additional Protections for Children Involved as Subjects in Research. 2002. 45 CFR 46.406 and 46.407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilfond BS, Diekema DS. Engaging children in genomics research: decoding the meaning of assent in research. Genetics in Medicine. 2012 Apr;14(4):437–443. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joffe S, Fernandez CV, Pentz RD, et al. Involving children with cancer in decision-making about research participation. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2006;149(6):862–868. e861. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.AAP Committee on Bioethics. Informed Consent, Parental Permission, and Assent in Pediatric Practice. Pediatrics. 1995;95(2):314–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broome ME, Kodish E, Geller G, Siminoff LA. Children in research: new perspectives and practices for informed consent. IRB: Ethics and Human Research. 2003 Sep-Oct;(Suppl 25 5):S20–S23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGuire AL, Basford M, Dressler LG, et al. Ethical and practical challenges of sharing data from genome-wide association studies: the eMERGE Consortium experience. Genome research. 2011;21(7):1001–1007. doi: 10.1101/gr.120329.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Other requirements relating to uses and disclosures of protected health information. 2002. 45 CFR 164.514. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurwitz D, Fortier I, Lunshof JE, Knoppers BM. Research ethics. Children and population biobanks. Science. 2009 Aug 14;325(5942):818–819. doi: 10.1126/science.1173284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brothers KB, Clayton EW. Biobanks: Too Long to Wait for Consent. Science. 2009;326(5954):798. doi: 10.1126/science.326_798a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.OHRP. Guidance on Research Involving Coded Private Information or Biological Specimens. Rockville, MD: Office of Human Research Protections; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldenberg AJ, Hull SC, Botkin JR, Wilfond BS. Pediatric biobanks: approaching informed consent for continuing research after children grow up. Journal of Pediatrics. 2009 Oct;155(4):578–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. General Requirements for Informed Consent. 2002. 45 CFR 46.116(d) [Google Scholar]

- 21.AAP Committee on Bioethics, AAP Committee on Genetics, ACMG Social Ethical and Legal Issues Committee. . Ethical and Policy Issues in Genetic Testing and Screening of Children. Pediatrics. 2013 Mar 1;131(3):620–622. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ross LF, Saal HM, David KL, Anderson RR. Technical report: Ethical and policy issues in genetic testing and screening of children. Genetics in Medicine. 2013;15(3):234–245. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clayton EW. Addressing the Ethical Challenges in Genetic Testing and Sequencing of Children. American Journal of Bioethics. 2013;14(3):3–9. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2013.879945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green RC, Berg JS, Grody WW, et al. ACMG recommendations for reporting of incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genetics in Medicine. 2013;15(7):565–574. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bledsoe MJ, Grizzle WE, Clark BJ, Zeps N. Practical implementation issues and challenges for biobanks in the return of individual research results. Genetics in Medicine. 2012 Apr;14(4):478–483. doi: 10.1038/gim.2011.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues. Anticipate and Communicate: Ethical Management of Incidental and Secondary Findings in the Clinical, Research, and Direct-to-Consumer Contexts. Washington, D.C: 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clayton EW, McGuire AL. The legal risks of returning results of genomics research. Genetics in Medicine. 2012 Apr;14(4):473–477. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolf SM, Crock BN, Van Ness B, et al. Managing incidental findings and research results in genomic research involving biobanks and archived data sets. Genetics in Medicine. 2012;14(4):361–384. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohane IS, Mandl KD, Taylor PL, Holm IA, Nigrin DJ, Kunkel LM. Reestablishing the Researcher-Patient Compact. Science. 2007 May 11;316(5826):836–837. doi: 10.1126/science.1135489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.My46. [Accessed 7/12/2012];2012 https://www.my46.org/

- 31.Avard D, Senecal K, Madadi P, Sinnett D. Pediatric research and the return of individual research results. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2011 Winter;39(4):593–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2011.00626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ross LF, Rothstein MA, Clayton EW. Mandatory extended searches in all genome sequencing: “incidental findings,” patient autonomy, and shared decision making. JAMA. 2013 Jul 24;310(4):367–368. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.41700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ross LF, Rothstein MA, Clayton EW. Premature guidance about whole-genome sequencing. Personalized Medicine. 2013 Aug 1;10(6) doi: 10.2217/pme.13.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klitzman R, Appelbaum PS, Chung W. Return of secondary genomic findings vs patient autonomy: implications for medical care. JAMA. 2013 Jul 24;310(4):369–370. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.41709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holtzman NA. ACMG recommendations on incidental findings are flawed scientifically and ethically. Genetics in Medicine. 2013 Sep;15(9):750–751. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. [Accessed April 9, 2014];ACMG Updates Recommendation on “Opt Out” for Genome Sequencing Return of Results. 2014 https://www.acmg.net/docs/Release_ACMGUpdatesRecommendations_final.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table: Language describing plans related to returning research results from seven eMERGE projects.