Abstract

Background

Little is known about the diagnostic accuracy of Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria for critical illness among emergency department (ED) patients with and without infection. Our objective was to assess the diagnostic accuracy of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria for critical illness in ED patients.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study of ED patients at an urban academic hospital. Standardized chart abstraction was performed on a random sample of all adult ED medical patients admitted to the hospital during a 1-year period, excluding repeat visits, transfers, ED deaths, and primary surgical or psychiatric admissions. The binary composite outcome of critical illness was defined as ≥24 hours in intensive care or in-hospital death. Presumed infection was defined as receiving antibiotics within 48 hours of admission. SIRS criteria were calculated using ED triage vital signs and initial white blood cell count.

Results

We studied 1,152 patients; 39% had SIRS, 27% had presumed infection, and 23% had critical illness (2% had in-hospital mortality, 22% had ≥24 hours in intensive care). Of patients with SIRS, 38% had presumed infection. Of patients without SIRS, 21% had presumed infection. The sensitivity of SIRS criteria for critical illness was 52% (95% confidence interval [CI] 46%–58%) in all patients, 66% (95% CI 56%–75%) in patients with presumed infection, and 43% (95% CI 36%–51%) in patients without presumed infection.

Conclusions

SIRS at ED triage, as currently defined, has poor sensitivity for critical illness in medical patients admitted from the ED.

Keywords: systemic inflammatory response syndrome, critical illness, sensitivity and specificity, diagnosis, emergency medicine, sepsis

INTRODUCTION

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) is widely used as an early and objective indicator of acute systemic inflammation. SIRS plays a prominent role in identifying emergency department (ED) patients eligible both for research enrollment and for initiation of advanced therapies, such as early goal directed therapy in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock.1–4 Although SIRS is often thought to be a necessary precursor of sepsis syndromes, recent consensus statements on defining sepsis have largely moved away from including SIRS given its lack of specificity. In fact, non-infectious SIRS appears to occur nearly twice as often as infectious SIRS in hospitalized patients.5 However, limited literature suggests that both infectious SIRS and non-infectious SIRS may share the same pattern of mortality, as each entity progresses toward multi-organ dysfunction and multi-organ failure.5–7 This suggests that SIRS may be more appropriately viewed as simply an early marker of severe or critical illness, regardless of infectious or non-infectious etiology.

SIRS criteria were originally created as an early marker of sepsis, yet prior literature has shown that SIRS criteria have a disappointing sensitivity for identifying patients with sepsis.8–10 Despite these findings, SIRS criteria continue to be widely used to identify patients who need specialized, advanced therapies and as an entry point for large clinical trials in the ED.2, 11, 12 Additionally, SIRS is specifically included in 5 billable ICD-9-CM codes and at least 3 ICD-10-CM codes related to both infectious and non-infectious conditions.13, 14 To be valuable, SIRS criteria should ideally miss few severely ill or critically ill patients. However, little is known about the diagnostic accuracy of SIRS criteria for critical illness among ED patients with and without infection.15

We designed this study with two specific aims: (1) to describe the prevalence of SIRS criteria in ED patients admitted to the hospital; (2) to assess the sensitivity of SIRS criteria for identifying ED patients with critical illness, as measured by extended intensive care unit (ICU) stay or in-hospital death.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study of adult patients admitted to the hospital from the ED. This study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board and met criteria for waiver of informed consent.

Setting

Denver Health Medical Center is a 477-bed, urban, academic medical center for the city and county of Denver, Colorado. In 2009, the ED census was approximately 60,000 visits, with approximately 19% of patients admitted to the hospital and 3% admitted to the medical ICU.

Selection of Participants

We included all unique ED patients with age >18 years old who were admitted to the hospital’s medicine service. We excluded repeat visits by the same patient, patients transferred to or from another hospital, patients who died in the ED, and patients who were primary surgical (including trauma) or psychiatric admissions. Surgical patients were excluded given potential differences in the etiologies and outcomes compared to medical patients.

Outcomes

The primary binary composite outcome was a “critical illness,” defined as a stay in the ICU of 24 hours or longer or in-hospital death. The use of 24 hours or longer of ICU stay was to reduce misclassification secondary to bed shortages or brief observational stays. The two outcomes of ICU stay of 24 hours or longer and in-hospital death were also considered separately as secondary outcomes in limited analyses.

Methods and Measurements

We identified all ED patients who were admitted to the hospital from April 1, 2008 through March 31, 2009 using our hospital’s electronic data warehouse. Data were extracted from the data warehouse using a standard electronic query request carried out by the data warehouse team. Data obtained included age, gender, race/ethnicity, first reported white blood cell count (WBC) in the ED, first reported serum lactate concentration, ED disposition (defined as admission, discharge, left prior to final evaluation, left against medical advice, expired, transferred), hospital admission service, administration of antibiotics within 48 hours of admission, ICU length of stay, and in-hospital mortality. From the records obtained using the electronic query, we first excluded repeat visits, then further limited the dataset to patients admitted to the medicine service. A random sample of 1,225 unique patients was then selected for structured retrospective medical record review to obtain initial ED triage vital signs, which were not available from the electronic data warehouse.16–18 The target number of patients (1,225) was chosen to balance feasibility of chart review with an estimated sample size that would provide adequate precision around our estimates for the sensitivity of SIRS criteria for critical illness.

Three abstractors blinded to the purpose of the study were trained on consecutive blocks of 25 sample charts until an agreement of 100% was achieved before beginning independent chart review. Agreement during training was based on comparison with the primary investigator. All written documentation in past medical records are scanned and electronically stored in our hospital’s clinical repository, and thus chart abstraction was performed using this electronic interface. Chart abstraction focused only on data not available by electronic query, specifically triage vital signs (i.e., temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate) or first available vital signs if the triage report was not complete or missing. Data were entered directly into an electronic data collection instrument. After chart abstraction was completed, the primary investigator randomly selected 10% of abstracted charts and re-abstracted the same variables to assess inter-rater reliability. Of these re-abstracted charts, the absolute number of disagreements was determined in addition to potential reasons for the differences if they occurred. As SIRS criteria were the primary interest of abstraction, inter-rater agreement was tested using a weighted Kappa coefficient (Kappa >0.80 considered excellent agreement).19 If Kappa was less than excellent, all records were re-abstracted, and a structured adjudication process was used to reconcile discrepancies.

Data Management and Statistical Analyses

Data from the electronic query were merged with the data obtained from chart abstraction for analysis. Patients were stratified into “presumed infection” and “no presumed infection” groups, the former defined as having received antibiotics within 48 hours of admission. This definition was chosen as the best possible option to reflect the treating physician’s initial suspicion of infection, after considering that using confirmed cultures would significantly under-classify infectious etiologies, using ED charts may over-classify infectious etiologies, and using final discharge administrative codes may not accurately reflect initial infectious etiologies.7, 20–22 Patients with SIRS were defined as having 2 or more of the following 4 criteria met using ED triage vitals signs and the initial WBC: (1) temperature >38° C or <36° C; (2) heart rate >90 per minute; (3) respiratory rate >20 per minute; or (4) WBC >12,000 or <4,000/μL.3

Descriptive data were summarized using medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) or proportions and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), as appropriate. We compared proportions using a two-sample test of proportions or chi-square test, and we compared medians using Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Using the composite binary critical illness outcome, the diagnostic characteristics and associated 95% CIs of SIRS criteria were calculated, including sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratio of a positive test, and likelihood ratio of a negative test. The cutoff used to define a patient having SIRS was also varied from its original 2 or more SIRS criteria (i.e., from 1 or more criteria to 4 or more criteria) to determine the effect of such a change on diagnostic characteristics.

A small proportion of patients were missing some or all of the vital signs from the entire ED encounter. We decided in this situation to assume the specific SIRS criterion of interest was not met and to calculate the total SIRS criteria score using available information. We performed a sensitivity analysis to test this assumption by excluding these patients and re-analyzing the primary results. To assess inter-rater reliability of the data as mentioned above, the re-abstracted vital signs and original abstracted vital signs were first used to calculate respective total SIRS criteria scores, then these two scores were compared using a weighted Kappa coefficient. Excellent agreement for Kappa was defined as >0.80.19 Statistical significance was defined as p <0.05. All data analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) or Stata Version 10.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

During our study period, 10,358 patient visits were identified from the initial electronic query of the data warehouse representing all ED admitted patients. Of these, 7,573 were unique patients of which 4,910 were medicine service admissions. From this sample, 1,225 (25%) patients were randomly sampled for abstraction. Of these patients, 73 patients did not meet our inclusion or exclusion criteria (65 patients were discharged, left against medical advice, or left prior to admission, and 8 patients were transfers, deaths in the ED, or admissions to the operating room), leaving 1,152 unique adult patients for analysis. Fifty-three of 1,152 (5%) patients were missing at least 1 of the 4 SIRS criteria. Our composite binary critical illness outcome was present in 267 of 1,152 (23%; 95% CI 21%, 26%) patients. The components of our composite outcome are stratified in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of emergency department (ED) patients admitted to the medicine service overall and within the strata of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).a,b

| Variable | All patients (n = 1152) | Patients with SIRS (n = 446) | Patients without SIRS (n = 706) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | (%) | No. | (%) | No. | (%) | |

| Age, in years; median (IQR) | 52 | (43, 62) | 50 | (42, 60) | 53 | (44, 62) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Male gender | 667 | (58) | 275 | (62) | 392 | (56) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 463 | (40) | 184 | (41) | 279 | (40) |

| Hispanic | 410 | (36) | 156 | (35) | 254 | (36) |

| Black | 208 | (18) | 77 | (17) | 131 | (19) |

| Other | 27 | (2) | 13 | (3) | 14 | (2) |

| Missing | 44 | 16 | 28 | |||

| Presumed infectionc | 313 | (27) | 168 | (38) | 145 | (21) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Critical illness composite outcomed | 267 | (23) | 139 | (31) | 128 | (18) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| In-hospital mortality | 22 | (2) | 11 | (2) | 11 | (2) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| ICU admission from ED | 266 | (23) | 152 | (34) | 114 | (16) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| ICU admission during hospitalization | 329 | (29) | 174 | (39) | 155 | (22) |

| Days in ICU; median (IQR) | 1 | (1, 3) | 1 | (1, 3) | 1 | (1, 3) |

| Hours in ICU; median (IQR) | 45 | (25, 83) | 47 | (25, 92) | 43 | (26, 74) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| ICU admission with ≥ 24 hours stay | 257 | (22) | 134 | (30) | 123 | (17) |

| Days in ICU; median (IQR) | 2 | (1, 4) | 2 | (1, 4) | 2 | (1, 4) |

| Hours in ICU; median (IQR) | 58 | (38, 108) | 60 | (39, 115) | 54 | (38, 97) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Frequency of each individual SIRS criteria | ||||||

| Temperature criterion | 288 | (25) | 199 | (45) | 89 | (13) |

| Missing | 41 | 13 | 28 | |||

| Heart rate criterion | 596 | (52) | 385 | (86) | 211 | (30) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Respiratory rate criterion | 282 | (24) | 250 | (56) | 32 | (5) |

| Missing | 12 | 3 | 9 | |||

| White blood cell count criterion | 324 | (28) | 248 | (56) | 76 | (11) |

| Missing | 5 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Triage temperature (Celcius); median (IQR) | 36.5 | (36.1, 37.0) | 36.6 | (35.9, 37.3) | 36.4 | (36.2, 36.8) |

| Missing | 41 | 13 | 28 | |||

| Triage heart rate (beats per minute); median (IQR) | 92 | (78, 109) | 107 | (96, 123) | 84 | (73, 94) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Triage respiratory rate (breaths per minute); median (IQR) | 18 | (16, 20) | 22 | (18, 26) | 18 | (16, 20) |

| Missing | 12 | 3 | 9 | |||

| Initial ED white blood cell count (1000/μL); median (IQR) | 8.9 | (6.8, 11.9) | 11.8 | (7.4, 15.3) | 8.2 | (6.6, 10.3) |

| Missing | 5 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Initial ED serum lactate (mmol/L) | 1.7 | (1.2, 2.7) | 1.9 | (1.4, 3.1) | 1.5 | (1.0, 2.2) |

| Missing | 852 | 262 | 590 | |||

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; IQR, interquartile range; ICU, intensive care unit; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

SIRS was defined as 2 or more of the following: temperature >38° C or <36° C; heart rate >90 per minute; respiratory rate >20 per minute; or white blood cell count (WBC) >12,000 or <4,000/μL.

53 patients were missing 1 of the 4 SIRS criteria variables. All instances of missing criteria variables were assumed to not have met that specific SIRS criterion.

Presumed infection defined as having received antibiotics within 48 hours of admission.

Critical illness defined as ≥24 hours in the intensive care unit or in -hospital death.

Descriptive Characteristics of Patients

Of the 1,152 patients, 298 (26%) patients had no SIRS criteria; 408 (35%) had 1 criterion; 291 (25%) had 2 criteria; 120 (10%) had 3 criteria; and 35 (3%) had 4 criteria. The heart rate criterion was by far the most common of the SIRS criteria met (Table 1). Overall, 446 patients (39%; 95% CI 36%, 42%) had SIRS (At least 2 individual criteria present).

When examining the strata of patients with and without SIRS, presumed infection was present more often in patients with SIRS than those without SIRS (difference 17%; 95% CI 12%, 23%). Patients with SIRS had a higher proportion of ≥24 hours stay in the ICU (difference 13%; 95% CI 8%, 18%) and composite binary critical illness outcome (difference 13%; 95% CI 8%, 18%). Age and gender were statistically different, but not race/ethnicity (p=0.007, p=0.04, p=0.67, respectively); however, these differences appeared small clinically.

Patients with presumed infection were found to have a higher proportion of critical illness compared to those without presumed infection both overall and within the subgroup of those patients with SIRS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Outcomes for emergency department (ED) patients admitted to the medicine service with presumed infection compared to those without presumed infection.a

| Variable | Patients with presumed infection | Patients without presumed infection | Percent Difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | (%) | No. | (%) | % | 95% CI | |

| All patients (n = 1152) | (n = 313) | (n = 839) | ||||

| Composite binary critical illness outcomed | 103 | (33) | 164 | (20) | 13 | 8, 19 |

| In-hospital deaths | 11 | (4) | 11 | (1) | 2 | 0, 4 |

| ≥24 hours stay in the ICU | 98 | (31) | 159 | (19) | 12 | 7, 18 |

| Patients with SIRS (n = 446)b, c | (n = 168) | (n = 278) | ||||

| Composite binary critical illness outcomed | 68 | (40) | 71 | (26) | 15 | 6, 24 |

| In-hospital deaths | 7 | (4) | 4 | (1) | 3 | −1, 6 |

| ≥24 hours stay in the ICU | 65 | (39) | 69 | (25) | 14 | 5, 23 |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

Presumed infection defined as having received antibiotics within 48 hours of admission.

SIRS was defined as 2 or more of the following: temperature >38° C or <36° C; heart rate >90 per minute; respiratory rate >20 per minute; or white blood cell count (WBC) >12,000 or <4,000/μL.

53 patients were missing 1 of the 4 SIRS criteria variables. All instances of missing criteria variables were assumed to not have met that specific SIRS criterion.

Critical illness defined as ≥24 hours in the intensive care unit or in -hospital death.

Sensitivity of SIRS

The highest sensitivity, regardless of presumed infection, was attained when only 1 or more SIRS criteria was used as a cutoff (Table 3), and this sensitivity dropped substantially if the standard definition for SIRS of 2 or more SIRS criteria was used. Additionally, using the standard definition for SIRS, sensitivity was significantly higher in patients with presumed infection than in patients without presumed infection.

Table 3.

Diagnostic characteristics of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteriaa,b for critical illness in admitted emergency department (ED) patients; n = 1152.c

| Sn (%) | 95% CI (%) | Sp (%) | 95% CI (%) | LR+ | 95% CI | LR− | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (n = 1152) | ||||||||

| ≥1 SIRS criteria | 85 | 80, 89 | 29 | 26, 32 | 1.2 | 1.1, 1.3 | 0.5 | 0.4, 0.7 |

| ≥ 2 SIRS criteriad | 52 | 46, 58 | 65 | 62, 68 | 1.5 | 1.3, 1.7 | 0.7 | 0.6, 0.8 |

| ≥3 SIRS criteria | 22 | 17, 27 | 89 | 87, 91 | 2.0 | 1.5, 2.7 | 0.9 | 0.8, 0.9 |

| 4 SIRS criteria | 5 | 3, 9 | 98 | 96, 99 | 2.2 | 1.1, 4.3 | 1.0 | 0.9, 1.0 |

| Patients with presumed infection (n = 313)e | ||||||||

| ≥1 SIRS criteria | 90 | 83, 95 | 19 | 14, 25 | 1.1 | 1.0, 1.2 | 0.5 | 0.3, 1.0 |

| ≥2 SIRS criteriad | 66 | 56, 75 | 52 | 45, 59 | 1.4 | 1.1, 1.7 | 0.6 | 0.5, 0.9 |

| ≥3 SIRS criteria | 27 | 19, 37 | 77 | 71, 83 | 1.2 | 0.8, 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.8, 1.1 |

| 4 SIRS criteria | 7 | 3, 14 | 94 | 90, 97 | 1.2 | 0.5, 2.9 | 1.0 | 0.9, 1.1 |

| Patients without presumed infection (n = 839)e | ||||||||

| ≥1 SIRS criteria | 81 | 74, 87 | 32 | 29, 36 | 1.2 | 1.1, 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.4, 0.8 |

| ≥2 SIRS criteriad | 43 | 36, 51 | 69 | 66, 73 | 1.4 | 1.2, 1.7 | 0.8 | 0.7, 0.9 |

| ≥3 SIRS criteria | 18 | 13, 25 | 93 | 91, 95 | 2.5 | 1.7, 3.8 | 0.9 | 0.8, 1.0 |

| 4 SIRS criteria | 4 | 2, 9 | 99 | 98, 99 | 3.2 | 1.2, 8.5 | 1.0 | 0.9, 1.0 |

Abbreviations: SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; ED, emergency department; Sn, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; CI, confidence interval; LR, likelihood ratio.

SIRS was defined as 2 or more of the following: temperature >38° C or <36° C; heart rate >90 per minute; respiratory rate >20 per minute; or white blood cell count (WBC) >12,000 or <4,000/μL.

53 patients were missing 1 of the 4 SIRS criteria variables. All instances of missing criteria variables were assumed to not have met that specific SIRS criterion.

Critical illness defined as ≥24 hours in the intensive care unit or in hospital death.

The results are bolded for the original SIRS criteria cutoff defined as 2 or more SIRS criteria.

Presumed infection defined as having received antibiotics within 48 hours of admission.

Table 4 presents all possible SIRS criteria score combinations. Descriptively, the two most common combinations meeting SIRS criteria were heart rate plus respiratory rate criterion and heart rate plus WBC criterion. As for diagnostic characteristics, of patients with critical illness, the most common combinations were heart rate criterion alone, no criteria at all, or heart rate plus respiratory rate criterion.

Table 4.

Frequency of all possible combinations of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria and the diagnostic characteristics for critical illness in admitted emergency department (ED) patients, n = 1152.a,b,c

| All patients

|

Measures of accuracy

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1152 | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Temperature criterion | Heart rate criterion | Respiratory rate criterion | WBC criterion | No. | (%) | Sn (%) | 95 % CI (%) | Sp (%) | 95% CI (%) | |

| - | - | - | - | 29 8 |

26 | 15 | 11, 20 | 71 | 68, 74 | |

| X | - | - | - | 89 | 8 | 5 | 3, 9 | 92 | 89, 93 | |

| - | X | - | - | 21 1 |

18 | 17 | 13, 22 | 81 | 79, 84 | |

| - | - | X | - | 32 | 3 | 2 | 1, 4 | 97 | 96, 98 | |

| - | - | - | X | 76 | 7 | 9 | 6, 13 | 94 | 92, 95 | |

|

| ||||||||||

|

SIRS |

X | X | - | - | 54 | 5 | 5 | 3, 9 | 95 | 94, 97 |

| X | - | X | - | 17 | 1 | 0 | 0, 1 | 98 | 97, 99 | |

| X | - | - | X | 22 | 2 | 2 | 1, 5 | 98 | 97, 99 | |

| - | X | X | - | 97 | 8 | 14 | 10, 19 | 93 | 91, 95 | |

| - | X | - | X | 87 | 8 | 8 | 5, 12 | 93 | 91, 94 | |

| - | - | X | X | 14 | 1 | 1 | 0, 3 | 99 | 98, 99 | |

| X | X | X | - | 30 | 3 | 4 | 2, 7 | 98 | 97, 99 | |

| X | X | - | X | 33 | 3 | 4 | 2, 8 | 98 | 96, 99 | |

| X | - | X | X | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0, 3 | 99 | 99, 100 | |

| - | X | X | X | 49 | 4 | 7 | 5, 11 | 97 | 95, 98 | |

| X | X | X | X | 35 | 3 | 5 | 3, 9 | 98 | 96, 99 | |

Abbreviations: SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; ED, emergency department; WBC, white blood cell count; Sn, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; CI, confidence interval.

SIRS was defined as 2 or more of the following: temperature >38° C or <36° C; heart rate >90 per minute; respiratory rate >20 per minute; or white blood cell count (WBC) >12,000 or <4,000/μL.

53 patients were missing 1 of the 4 SIRS criteria variables. All instances of missing criteria variables were assumed to not have met that specific SIRS criterion.

Critical illness defined as ≥24 hours in the intensive care unit or in-hospital death.

Inter-Rater Agreement and Sensitivity Analysis

Re-abstraction was performed on 120 randomly selected patients from our study sample and, when comparing calculated SIRS criteria, showed a weighted Kappa of 0.99 (95% CI 0.98–1.00). Only 2 of 120 (2%) records had errors in abstraction, and both involved misinterpretation of the written text. Fifty-three patients had 1 or more missing components of SIRS criteria, and these were assumed to have not met SIRS criteria in the primary analyses. We performed a sensitivity analysis by excluding these 53 patients and found no substantial change in the results of our diagnostic characteristics. When we changed all instances of missing criteria to positive criteria, we noted small but non-significant increases in the sensitivity and decreases in the specificity of all cutoffs of SIRS criteria.

DISCUSSION

Our results showed that despite being common among ED adult patients admitted to the medicine service, presence of SIRS criteria during ED triage has poor sensitivity for detecting critical illness, regardless of whether presumed infection is present or absent. SIRS criteria continues to serve an important role in the inclusion criteria for multicenter ED and critical care research trials and also for selecting patients appropriate for advanced therapies in sepsis.1–4 Yet, our results call into question the continued role SIRS criteria plays as an early screening tool for severely ill patients in the ED.

We found very limited prior research that examined the sensitivity of SIRS in the ED setting, all of which focused mainly on the ability of SIRS criteria to identify patients with suspected infection.8–10 However, since suspected infection is often an independent clinical criteria for advanced therapies like early goal directed therapy,1 we examined instead the role SIRS criteria would have in screening for patients who have critical illness. Our results would suggest that hospitals using SIRS criteria to identify patients with potential critical illness may miss up to 54% of all critically ill patients and up to 44% of critically ill patients in those with presumed infection. These results are dramatically different from prior opinions in the literature that suggest SIRS criteria are highly sensitive.23, 24 Although it remains unstudied, these patients who are critically ill but do not meet SIRS criteria may also benefit from advanced ED therapeutic strategies. We also noted that when SIRS was defined with a modified cutoff of 1 or more, the sensitivity dramatically increased, regardless of presumed infection. Whether the expected drop in specificity using this modified cutoff is acceptable remains debatable.

Our results also showed that of admitted ED patients with SIRS, only 38% had presumed infection, which is similar to prior reports using inpatient records.5, 7 Prior studies have suggested that non-infectious SIRS may share the same mortality as infectious SIRS.5–7 However, our results show that patients with infectious SIRS may in fact have a higher likelihood of critical illness. Our findings are tempered by the fact that prior literature defined infection as culture-confirmed infectious etiology whereas we used a definition of “presumed infection.” Additionally, prior literature compared mortality across the spectrum of SIRS, SIRS with multi-organ dysfunction, and SIRS with multi-organ failure,5–7 thus similarities in mortality may ultimately be present in our patients if we examine these categories separately.

Our study is likely generalizable to most large urban medical centers with similar populations; however, our results would benefit from further validation at another site. We believe that in its present state, SIRS criteria as a screening tool is limited in the ED setting; yet, with further refinement or modification it may continue to serve an important role in the future both clinically and for research enrollment. Another option would be to abandon SIRS criteria and derive empirically a novel early ED screening tool that can be used to identify potentially critically ill patients generally or within the subset of patients with suspected infection.

LIMITATIONS

This study was limited by the use of retrospective data as potentially important data elements may be missing or incorrectly documented. Our definition of “presumed infection” may be subject to misclassification bias; however, this is true of most sepsis studies, which attempt to define an infectious etiology based on retrospectively available data.7, 15, 21 Our definition of “critical illness” may also be subject to misclassification bias. For example, a patient’s ICU stay may be prolonged due to logistical delays in transferring out of the ICU, unrelated to illness severity. Also, a patient’s prolonged ICU stay may be unrelated to the initial ED problem and instead related to complications that developed during hospitalization.

Our classification of SIRS criteria was limited somewhat by using only triage vital signs. It is possible that when using all ED vital signs, the diagnostic accuracy and associations with outcome would be significantly different. However, our intent was to determine how effective SIRS criteria were as an early screening tool, and the use of other ED vital signs would diminish this intent. We recognize that temperature could have been measured using multiple methods (i.e., rectal, oral, axilla) and that fever follows an undulating pattern, therefore the lack of fever in some patients could simply represent misclassification.

Given that certain data elements in our study required clinical judgment (e.g., ICU length of stay, administration of antibiotics, decision to admit to ward or ICU), we recognize that SIRS criteria may have biased our results through incorporation bias.25 The likely effect of such bias would be an overestimation of accuracy that could bias our results away from the null hypothesis.25, 26 We could not determine the extent of such bias in our study; however, at our institution, SIRS criteria is not part of any defined clinical guideline for administration of antibiotics, admission, or ICU management except as part of our guideline for patients with severe sepsis and septic shock.1

We chose to include only patients admitted from the ED, therefore, our results may be different when applied to a generalized ED population in which disposition has not yet been decided. However, adding discharged patients we assume would simply improve our specificity (as we assume most would not have critical illness and more would likely not have SIRS), but would have minimal impact on sensitivity (again most would not have critical illness).

As we did not perform follow-up on patients discharged from the hospital, it is possible that patients who were discharged became critically ill or died. While this is likely to represent a small proportion of our sample population, we were unable to determine this information in this study, and it could lead to misclassification of our outcome.

CONCLUSION

SIRS at ED triage, as it is currently defined, has poor sensitivity for critical illness in medical patients. Refinement, modification, or even abandonment of the SIRS criteria is potentially necessary to effectively capture critically ill patients with or without presumed infection in clinical practice or in future ED or critical care research trials.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Liao was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (F32 HS018123) and Dr. Haukoos was supported by the AHRQ (K02 HS017526).

FUNDING SOURCES

The research conducted in this study was not supported by any funding.

APPENDIX

This Appendix includes figures to provide additional descriptive representation of our data. Figure A is a set of scatterplots of “Days in Intensive Care Unit” on the y-axis and each of the 4 systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria on the x-axis. We chose to use days in intensive care unit instead of hours in intensive care unit as the range of hours created too large of a range, limiting utility of the scatterplot. We also truncated 4 observations that exceeded 30 days and reclassified them at 30 days to again limit the range of the y-axis. Two white blood cell count values were deleted from the graph as they were extreme values (403,000 per mcL and 732,000 per mcL) and would again significantly skew the scatterplot. Data were jiggled near zero (between 0 and 0.5) to show better where zero data were clustering.

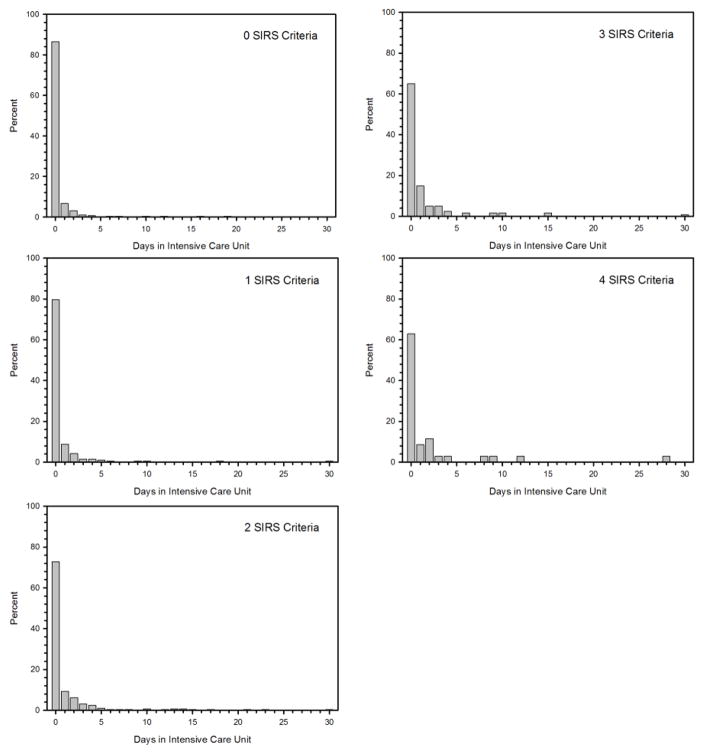

Figure B is a set of histograms for days in intensive care unit stratified by number of SIRS criteria along its interval range from 0 to 4. Again we truncated 4 observations that exceeded 30 days and reclassified them at 30 days to limit the range of the x-axis.

Figure A.

Scatterplots of days in intensive care unit and each of the 4 individual systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria.

Figure B.

Histograms of days in intensive care unit and total systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria along its interval range from 0 to 4.

Footnotes

Presentations: Oral presentation at the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Western Regional Annual Meeting, Keystone, CO, February 2011. Poster presentation at the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Annual Meeting, Boston, MA, June 2011. Oral presentation as a Masters capstone project at University of Colorado Denver, Aurora, CO, July 2011.

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Liao was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (F32 HS018123) and Dr. Haukoos was supported by the AHRQ (K02 HS017526).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones AE, Shapiro NI, Trzeciak S, Arnold RC, Claremont HA, Kline JA. Lactate clearance vs central venous oxygen saturation as goals of early sepsis therapy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2010;303:739–46. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Conference: definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:864–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernard GR, Vincent JL, Laterre PF, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:699–709. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103083441001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brun-Buisson C. The epidemiology of the systemic inflammatory response. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26 (Suppl 1):S64–74. doi: 10.1007/s001340051121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dulhunty JM, Lipman J, Finfer S. Does severe non-infectious SIRS differ from severe sepsis?: Results from a multi-centre Australian and New Zealand intensive care unit study. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:1654–61. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rangel-Frausto MS, Pittet D, Costigan M, Hwang T, Davis CS, Wenzel RP. The natural history of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). A prospective study. JAMA. 1995;273:117–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaimes F, Garces J, Cuervo J, et al. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) to identify infected patients in the emergency room. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1368–71. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1874-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones GR, Lowes JA. The systemic inflammatory response syndrome as a predictor of bacteraemia and outcome from sepsis. QJM. 1996;89:515–22. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/89.7.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meurer WJ, Smith BL, Losman ED, et al. Real-time identification of serious infection in geriatric patients using clinical information system surveillance. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:40–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perman SM, Chang AM, Hollander JE, et al. Relationship between B-type natriuretic peptide and adverse outcome in patients with clinical evidence of sepsis presenting to the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:219–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russell JA, Walley KR, Singer J, et al. Vasopressin versus norepinephrine infusion in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:877–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Medical Association. ICD-9-CM, 1996 : international classification of diseases, 9th revision, clinical modification : volumes 1 and 2, color-coded, illustrated ICD-9 CM codes. Dover, DE: American Medical Association; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buck CJ American Medical Association. 2010 ICD-10-CM draft. St. Louis, Mo: Saunders Elsevier; 2010. Standard ed. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shapiro N, Howell MD, Bates DW, Angus DC, Ngo L, Talmor D. The association of sepsis syndrome and organ dysfunction with mortality in emergency department patients with suspected infection. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:583–90. 90 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilbert EH, Lowenstein SR, Koziol-McLain J, Barta DC, Steiner J. Chart reviews in emergency medicine research: Where are the methods? Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27:305–8. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowenstein SR. Medical record reviews in emergency medicine: the blessing and the curse. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45:452–5. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Worster A, Haines T. Advanced statistics: understanding medical record review (MRR) studies. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:187–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med. 2005;37:360–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shapiro NI, Wolfe RE, Moore RB, Smith E, Burdick E, Bates DW. Mortality in Emergency Department Sepsis (MEDS) score: a prospectively derived and validated clinical prediction rule. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:670–5. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000054867.01688.D1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pittet D, Rangel-Frausto S, Li N, et al. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome, sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock: incidence, morbidities and outcomes in surgical ICU patients. Intensive Care Med. 1995;21:302–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01705408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1250–6. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000050454.01978.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brivet FG, Jacobs FM, Prat D. How “Dear SIRS” and MEDS can help for ED triage. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2715. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181847421. author reply -6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vincent JL. Dear SIRS, I’m sorry to say that I don’t like you. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:372–4. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199702000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Worster A, Carpenter C. Incorporation bias in studies of diagnostic tests: how to avoid being biased about bias. CJEM. 2008;10:174–5. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500009891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mower WR. Evaluating bias and variability in diagnostic test reports. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:85–91. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70422-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]