Abstract

Trillions of commensal bacteria cohabit our bodies to mutual benefit. In the past several years, it has become clear that the adaptive immune system is not ignorant of intestinal commensal bacteria, but is constantly interacting with them. For T cells, the response to commensal bacteria does not appear uniform, as certain commensal bacterial species appear to trigger effector T cells to reject and control them, whereas other species elicit Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells to accept and be tolerant of them. Here, we review our current knowledge of T cell differentiation in response to commensal bacteria, and how this process leads to immune homeostasis in the intestine.

Keywords: T cell, commensal, mucosa, Treg, effector cell, IgA, intestine, tolerance, inflammatory bowel disease

1. Introduction

The intestines are home to hundreds of commensal bacterial species that provide many benefits to the host, including important contributions to the metabolism of food [1]. However, as commensal bacteria are foreign to the host, they can trigger unwanted immune responses such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [2]. Yet, the gastrointestinal tract is also an important portal for bacterial infections. Thus, the immune system must protect against pathogenic bacteria while avoiding inappropriate immune responses to commensal bacteria.

In broad strokes, this balancing act is analogous to that employed by the immune system to protect against infections while avoiding autoimmunity. However, the mechanisms that prevent immune responses to self-antigens may not be applicable to commensal bacterial antigens. An important mechanism of self-tolerance is the purging of auto-reactive cells while they are still immature and unable to cause immunopathology For T cells, this occurs in the thymus, an organ that is far removed from the intestine. Gut antigens are therefore unlikely to be present in the thymus to induce tolerance, implying that different mechanisms are utilized to prevent unwanted T cell immune responses to commensal bacteria. Here, we will review our current understanding of T cell interactions with commensal bacteria that preserve immune homeostasis and avoid immunopathology.

2. Regulatory T cells play a crucial role in maintaining tolerance to commensal bacteria

Although the mucosal lining of the intestine provides an important protective barrier against commensal bacteria, it has become clear that this barrier is imperfect, resulting in a need for immune tolerance to gut antigens. One of the first clues came from early studies showing that a subset of CD4+ T cells [3], now known to be Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells, is required to prevent other CD4+ T cells from inducing colitis upon transfer into lymphopenic hosts (reviewed in [2, 4, 5]). Subsequent studies showed that commensal bacteria are important for driving intestinal pathology in the context of Treg cell deficiency For example, ablation of IL-2 leads to a loss of Treg cell number and function, which results in a variety of immunopathology [6]. However, only colitis is markedly reduced in germ-free (GF) IL-2-deficient mice [7–9]. Similarly, GF conditions limit colitis, but not other inflammatory manifestations, that arise with depletion of Foxp3+ cells in Foxp3DTR mice [10], or with T cell deletion of Uhrf1 (Ubiquitin-like, with pleckstrin-homology and RING-finger domains 1), an epigenetic regulator that facilitates colonic Treg proliferation and maturation [11]. As memory T cells from conventionally housed mice are more efficient at inducing colitis [12], these data suggest that Treg cells act to restrain normal effector responses to commensal bacteria. Thus, Treg cells are important in establishing a tolerogenic environment to maintain immune homeostasis to commensal bacteria in the intestine.

Substantial progress has been made in the past several years regarding the origin and specificity of Treg cells involved in intestinal tolerance. Although it is still debated [13], several lines of evidence suggest that colonic Treg cells arise primarily from peripheral Treg cell differentiation from naïve T cells (pTreg, [14, 15]), as opposed to arising from the thymus during T cell development (tTreg, [16, 17]). First, adoptive transfer of naïve T cells into normal hosts suggested that the intestines are sites that facilitate peripheral Treg cell selection [18]. Second, markers that may distinguish thymic Treg cells such as high expression of Helios or Neuropilin-1 (Nrp-1) imply that ~80% of colonic Treg cells arise from peripheral selection [19–21]. Third, one T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire study suggested that most colonic Treg TCRs do not facilitate thymic Treg cell selection [22]. Fourth, a study of Foxp3-deficient mice devoid of Treg cells revealed that adoptive transfer of natural Treg cells was not sufficient to restore immune homeostasis, and required transfer of Foxp3− cells capable of undergoing peripheral Treg cell selection [23]. Finally, studies of the Foxp3 locus revealed that mice deficient in conserved noncoding sequence-1 (CNS-1) had fewer Treg cells in the intestine, which was correlated with a defect in peripheral Treg cell selection [24, 25]. Taken together, these data support an important role for peripheral Treg cell selection in the gut.

However, other reports have argued against this interpretation. For example, the sensitivity and specificity of markers of thymic versus peripheral Treg cell selection such as Helios has been called into question [23, 26, 27]. Moreover, a different TCR repertoire study suggested that most colonic Treg cells are of thymic origin based on cross-referencing TCR sequences [28]. While future experiments are required to determine the exact proportions of pTreg versus tTreg in the colon, it is clear that the intestines are enriched in pTreg cells relative to other tissues in the body.

In regards to the antigen specificity of colonic Treg cells, recent studies suggest that they are often reactive to commensal bacteria. First, several studies reported that some, but not all, bacterial species can increase the frequency of Treg cells in the gut. For example, Clostridium clusters XIVa and IV [21, 29] or altered Schaedler flora (ASF) [30] introduced into GF mice markedly increased the frequency of colonic Treg cells. Lactobacillus reuteri [31] has also been associated with increased Treg cell percentage in the intestines. Second, analyses of TCR repertoires suggested that a substantial fraction and perhaps the majority of colonic Treg TCRs recognize commensal bacterial antigens. Since the TCR repertoire is extremely complex, mice with limited TCR repertoires were used to assess the colonic Treg TCR repertoire [22, 28]. In these studies, it was observed that colonic Treg cells utilized TCRs that were different than those used by Treg cells in other tissues or secondary lymphoid organs [22]. Further analysis of colonic Treg TCRs revealed direct recognition of antigens present in colonic contents, or in several cases, individual bacterial isolates [22, 28]. Consistent with TCR recognition of commensal bacterial antigens, antibiotic treatment could markedly change the colonic Treg repertoire [28], Taken together, this body of evidence strongly suggests that commensal bacteria routinely trigger antigen specific Treg cell responses.

3. Mechanisms that facilitate Treg cell selection in the gut

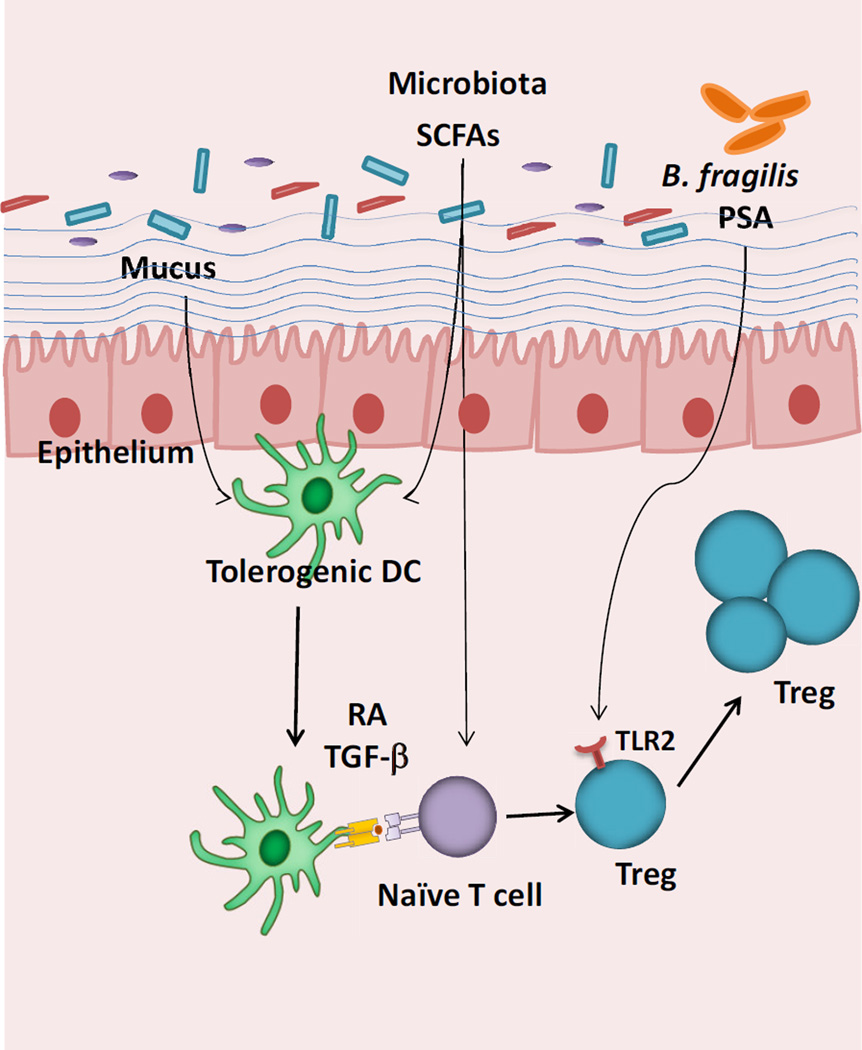

The enhancement in peripheral Treg cell selection to commensal bacteria may result from a number of mechanisms (Fig. 1). First, antigen presenting cell (APC) subsets in the intestine such as CD103+ dendritic cells (DCs) have been reported to favor Treg cell selection, as they express higher levels of retinal dehydrogenase (RALDH) to produce the vitamin A metabolite retinoic acid (RA) [18, 32, 33]. RA may inhibit effector cell cytokine production [34], as well as act directly on T cells [35] to promote Treg cell selection. Moreover, CD103+ DCs can generate transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) that acts in concert with RA to induce Treg cells [36]. Finally, it has been reported that these DC functions may be related to WNT/β-catenin signals that are delivered to intestinal, but not splenic DCs [37].

Figure 1. Mechanisms that facilitate Treg cell selection in the gut.

Commensal bacteria can promote the induction of Treg cells via direct sensing of microbial products through TLRs or metabolites such as SCFAs. Commensals or SCFAs can also induce tolerogenic DCs that favor Treg cell differentiation through the production of RA and TGF-β. Mucus and intestinal WNT can also trigger a β-catenin dependent tolerogenic program in DCs. The sites of interactions are not specified in this Figure, but may be in the mesenteric lymph nodes.

What might be the signals localized to the gut that promote these DCs to facilitate Treg cell selection? One recent report suggested that mucus from the intestinal lumen itself can activate tolerogenic pathways in DCs by triggering WNT signaling via β-catenin [38]. Mucus triggered WNT-signaling might be predicted to affect only the subset of DCs close to the mucosal surface. However, a TCF reporter of WNT signaling suggests that intestinal DCs receive a fairly uniform degree of WNT signaling [37]. Future studies are required to address the relative contributions of mucus versus other sources of WNT signaling in intestinal DCs.

Another potential intestinal signal for Treg cell selection may come from the microbiota itself. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) arising from bacterial fermentation can act on DCs to promote tolerance [39–41]. SCFAs may also act directly on T cells themselves to promote colonic Treg cell expansion [42]. Another bacterial product that can affect Treg cells is polysaccharide A (PSA) from Bacteroides fragilis (B. fragilis), which triggers toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 on Treg cells to induce IL-10 production [43]. Thus, commensal bacteria themselves provide potent signals that are interpreted by the intestinal immune system to facilitate tolerance.

4. Effector cell generation to commensal bacteria

Despite the plethora of intestinal factors that favor Treg cell differentiation or expansion, Treg cells represent only 20–40% of CD4+ T cells in the colon. Effector cells therefore represent the dominant T cell population within the intestine during homeostasis [44, 45]. The generation of effecter T cell subsets in the intestine has been associated with signals derived from commensal bacteria, as GF mice harbor fewer Th1 and Th17 cells compared to conventionally housed mice [12, 46]. Also, DNA from gut bacteria plays an important role in the induction of gut resident Th1 and Th17 cells at steady state through the engagement of TLR9 [47]. Thus, the generation of intestinal effector T cell population is clearly influenced by the commensal bacteria.

It is less clear, however, whether intestinal effector T cells recognize commensal bacterial antigens. Indirect support comes from the observation that effector T cells induced in the presence of commensal bacteria are more efficient at inducing colitis than cells from GF mice [12]. However, this does not necessarily mean that effector cells are specific to commensal bacteria, as bacterial products may also cause antigen-non-specific changes in the environment that affect T cell trafficking, differentiation, and function. Direct support for commensal-specific effector cell generation comes from murine studies of Th17 cells, which were shown to be critically dependent on a single bacterial species-segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB) [48]. SFB is a spore-forming Gram-positive anaerobe residing primarily in the terminal ileum that makes intimate interaction with the mucosal barrier through tight attachments to epithelial cells. This interaction is a unique feature of SFB compared with other commensal bacteria that may underlie its ability to elicit Th17 cells. Recently, it was shown that the majority of Th17 cells are specific to SFB antigens [49, 50], suggesting that SFB provides both the dominant T cell epitopes as well as signals that facilitate Th17 differentiation. Thus, both Treg and effector cells can be elicited to commensal bacteria.

5. Effector versus regulatory T cell selection

The induction of both Treg and effector cells by commensal bacteria raises a fundamental question as to how the immune system determines Treg versus effector cell selection to bacterial antigens. Available data suggests that this is not a stochastic process, but may be instructed by specific bacterial species. For example, Th17 selection to SFB is not accompanied by Treg selection, as SFB-specific TCR transgenic cells become mostly RORγt+ and not Foxp3+ cells [49]. Similarly, it has been reported that CD44hi effector T cells utilize different TCRs than Treg cells [22], indicating cell-fate determination based on TCR specificity.

The usage of different TCRs between Treg and effector cells could suggest that a biophysical property of TCR interaction with peptide:MHC, such as affinity or the amount of antigen, may determine peripheral T cell selection [51, 52]. In addition, recent studies indicate that environmental factors contribute to peripheral T cell differentiation to commensal bacteria. For example, SFB-specific TCR transgenic cells undergo Th1, and not Th17, development when their cognate antigen is expressed by Listeria and not SFB [49]. Moreover, TCR transgenic cells specific for the commensal CBir1 flagellin antigen adopt a Th1 phenotype upon infection with Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii), but a Th17 phenotype after dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) injury [53]. Although studies of Treg versus effector cell differentiation to commensal bacteria are currently unavailable, OT-II TCR transgenic cells undergo peripheral Treg cell development in response to oral feeding of cognate antigen [18, 54], whereas they undergo effector cell generation in the context of infection [55]. Therefore, TCR affinity for antigen, antigen dose, and the cytokine milieu may all contribute to the signals that direct T cell lineage commitment.

Innate stimulators from commensal bacteria may direct T cell differentiation via selective activation of cytokine production from APCs by TLRs, which are important sensors that recognize conserved molecular motifs on bacteria. TLRs have been suggested to promote pro-inflammatory effector responses. For instance, mice deficient in MyD88 (Myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88), an important signaling component for many TLRs, are relatively resistant to intestinal inflammation resulting from Treg cell [56] or IL-10 [57] deficiency. Consistent with these observations, TLR9 sensing of commensal DNA has been suggested to favor intestinal effector (Th1/Th17) rather than Treg development [47]. However, a role for TLRs in Treg selection has also been suggested. TLR2 signaling has been reported to induce IL-10 and RA to promote Treg cell selection [58]. DNA of the probiotic Lactobacillus species is enriched in suppressive motifs that signal through TLR9 to prevent DC activation and maintain Treg-cell conversion during inflammation [59]. Moreover, B. fragilis PSA can trigger TLR2 signaling on Treg cells to induce IL-10 expression and promote tolerance [43]. One explanation for some of these contrasting reports is that TLRs are found on many cell types and contribute to facets of intestinal homeostasis not directly related to T cell differentiation signals, including epithelial integrity [60]. Thus, while it is likely that TLRs play an important role in T cell responses to commensal bacteria, their precise function in determining peripheral T cell differentiation to specific bacterial species remains to be determined.

APC subsets have also been implicated in Treg versus effecter cell determination [61, 62]. Lamina propria DC subsets may provide different cytokine environments that favor Treg versus Th17 selection. As discussed above, CD103+ DCs have been suggested to favor Treg cell selection via production of RA and TGFp [18, 32, 33]. Interestingly, the CD11b+ subset of CD103+ DCs have been found to be potent producers of IL-6 and IL-23 that favor Th17 differentiation [47, 63, 64]. Consistent with these observations, genetic depletion of the CD103+CD11b+ DC subset showed a decrease in Th17 cells [64–66], whereas depletion of both CD11b+ and CD11b subsets of CD103+ DCs were required to see a decrease in the number of Treg cells [65]. However, it is unclear whether the impact on the number of Th17 versus Treg cells is related to specific response to bacteria species or global effects on the overall cytokine environment, as the decreased number of Th17 cells was independent of MHC II expression on the CD103+CD11b+ cells [65].

Other types of APC have also been described to be involved in gut homeostasis [67]. Macrophages, perhaps via cytokine production, can affect the regulatory to effector cell balance in the gut [68, 69]. Recently, another cell type in addition to the traditional APCs (DCs and macrophages) has been suggested to perform an antigen presenting role in the gut. Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) were recently shown to express MHC II and negatively regulate CD4+ T cell responses [70]. However, instead of inducing Treg cells, it was suggested that ILC antigen presentation inhibits the differentiation of effector T cells via an unknown mechanism.

In summary, there are many parameters that can control T cell differentiation to commensal bacteria. There are global factors such as SCFAs, WNT, TGFp, and RA that favor Treg cell selection. There are local factors such as TLR ligands, access to mucus, and different APC subsets that differentially favor Treg versus effector cell selection. Moreover, it is possible that some global factors are also modulated at the local level, and vice versa. Anatomic factors, such as small intestine versus colon may also play a role by affecting the resident bacterial constituents (e.g. SFB is mostly ileal), mucus amount and composition, mucosal barrier function, and APC types. Thus, much remains to be discovered regarding how individual commensal bacterial species trigger the specific mechanisms that determine Treg versus effector T cell differentiation.

6. Effector versus regulatory T cell function during homeostasis

During homeostasis, both regulatory and effector T cells with differing antigen specificities are generated to commensal bacteria. While thymically-derived Treg cells are likely to be involved at some level in intestinal tolerance to commensal bacteria [28], their functional role has not been clearly established. However, the importance of peripheral Treg cell selection in maintaining tolerance to commensal bacteria is supported by the aforementioned studies of T cell transfers into Foxp3-deficient mice [23], as well as studies of CNS-1-deficiency in the Foxp3 locus [24].

By contrast, the role of effector T cells in gut homeostasis to commensal bacteria has been more difficult to demonstrate. One hypothesis is that effector T cells represent an active immune response against certain commensal bacterial species. For example, it has been shown that CD4 T cells are required in the regulation of IgA production, and thus indirectly prevent bacterial translocation in mice lacking junctional adhesion molecule A (JAM-A, encoded by F11r) [71]. Similarly, the aberrant expansion of SFB in IgA deficient mice suggests that adaptive immunity can restrain certain commensal bacteria [72]. Other examples come from studies of innate cells, where depletion of ILCs revealed a marked dissemination and systemic infection of commensal bacteria Alcaligenes [73]. Furthermore, absence of T-bet, a transcription factor important for Th1 type responses, in innate cells in T and B cell-deficient mice results in loss of commensal bacterial control and inflammation [74]. However, T-bet deficiency in mice with T and B cells does not result in spontaneous colitis [74]. Similarly, spontaneous pathology has not been reported for mice deficient in the signature Th17 cytokine, IL-17 [75] or transcription factor RORγt [76]. Thus, effector T cells, perhaps via induction of IgA, may act to constrain certain species, but do not appear required for preventing large scale invasion by commensal bacteria during homeostasis.

Another possibility is that effector T cells have no major role in homeostasis, and are byproducts of an immune system that cannot perfectly determine whether each bacterial epitope is associated with a benign versus pathogenic bacteria [77, 78]. This is reminiscent of the observation that some self-reactive cells do escape thymic tolerance mechanisms that induce deletion or tTreg cell selection. While these autoreactive escapees of thymic selection appear quiescent during homeostasis, their pathogenic potential can be revealed after adoptive transfer into lymphopenic hosts [79] or Treg cell depletion [80].

A third possibility is that effector T cells to commensal bacteria exist to prime the immune system against pathogens. For example, mice harboring SFB are more resistant to Citrobacter Rodentium infection [48]. However, it remains possible that commensal bacteria can influence ILCs or other innate immune cells in addition to altering the effector T cell population. Thus, a clear role for commensal bacteria-specific effector T cells during homeostasis remains to be established.

7. T/B collaboration in response to commensal bacteria

The data discussed above suggests that both effector and regulatory T cells routinely interact with commensal bacteria under homeostatic conditions [45]. Similarly, the B cell arm of the adaptive immune system has also been found to interact with commensal bacteria during homeostasis [81, 82], with the majority of B cells in gut associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) directed towards bacterial antigens [83]. As suggested by a study of a commensal species Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron [84], IgA may limit the ability of commensal bacteria to trigger an inflammatory response.

Although T cell help is not essential for IgA class switching in the intestines [85], it appears that the paradigm of T cell help for B cells is applicable to intestinal IgA production during homeostatic conditions, as the presence of T cells is important for generating somatic hypermutation [86]. Moreover, TCR transgenic cells specific to a commensal bacterial flagellin antigen CBir1 induce IgA to that antigen [87]. Thus, these data suggests that commensal bacterial antigens are presented to both the B and T cell arms of the adaptive immune system during homeostasis.

One interesting observation from the TCR transgenic experiments was that depletion of Treg cell using anti-CD25 lead to a decrease in anti-CBir1 IgA, suggesting that Treg cells provide help for B cells [87]. Foxp3+ Treg cells have been reported to convert to follicular B helper T cells (Tfh) in lymphopenic settings [88]. However, an alternative possibility is that CD25 depletion may also affect effector cells. Additionally, Treg cells have also been reported to convert into follicular regulatory T cells (Tfr) [89, 90], which lack CD40L expression and instead secrete IL-10 and may act to inhibit, rather than provide, T:B collaboration. Thus, it remains unclear whether Treg cells, perhaps via transdifferentiation into other T cell subsets, provide T cell help for B cells.

Th17 cells appear to be an important source of B cell help, as large numbers of both antigen specific and nonspecific Th17 cells were reported to migrate to B cell germinal centers in the diffuse lamina propria during SFB colonization[91]. Other groups utilized cell fate reporters have shown that Th17 cells can also convert to Tfh cells in the gut [92]. However, as Th17 cells have not been reported to be readily induced to bacterial species other than SFB, the mechanism of T cell help for IgA class switching and affinity maturation that react to the rest of the microbiota remains unclear.

8. Are adaptive immune responses to commensal bacteria dynamically regulated?

An intriguing observation regarding IgA produced in response to commensal bacteria is that it appears to be dynamically regulated [93]. While colonization of GF mice with one species resulted in a specific and long-lived IgA response, this response was lost with the addition of other commensals. Moreover, repeated exposure to the commensal did not result in the booster effect that might be expected based on the classic immunization paradigm. These data suggest that IgA responses to commensal bacteria may not fit the pattern of classic long lived plasma cells that can last the life of an individual, but rather are dynamically regulated by the current commensal bacterial population.

Indeed, there are other peculiarities of the GALT B cell biology that distinguishes the IgA response from a typical systemic B cell response. For example, mucosal associated IgA plasma cells do not seem to home to the bone marrow (BM), and are instead retained in the gut, where APRIL- (a proliferation inducing ligand) secreting neutrophils have been suggested to aid in B cell maintenance and survival [94]. Additionally, gut IgA plasma cells, unlike BM plasma cells, retain functional B cell receptors on their surface [95], which may provide survival signals in lieu of BM stroma-derived cytokines. Whether these differences in IgA B cell biology account for the dynamic nature of IgA responses to commensals is unclear.

An intriguing question is whether all adaptive immune responses to commensal bacteria are dynamic and relatively short lived. Treg cells have been suggested to be regulated by the amount of self-antigens, as the Treg TCR repertoire changes with the anatomic location of secondary lymphoid organs [96, 97]. Similarly, the number of small intestinal Th17 cells has been shown to decrease when the mice are treated with vancomycin, an antibiotic that kills SFB [98]. When SFB is reintroduced, Th17 numbers go up, consistent with dynamic regulation of the T cell population. These observations in Treg and Th17 cells support the notion that continual competition for antigen may drive the intestinal immune system. This does not preclude the possibility that T cell memory can co-exist with dynamic regulation, as strong responses may elicit memory in the effector [53, 99] and regulatory T cell population [100].

In addition to the provision of antigens that maintain T cell “fitness”, commensal bacteria may also tune the T cell population through other factors. For example, it has been shown that commensal bacteria-stmulated IL-23 [101] and IL-15 [102] promote inflammatory T cell responses. Similarly, RA was required to elicit proinflammatory T cell responses to infection and mucosal vaccination [103]. In addition, IL-12 can enhance the antigen responsiveness of T cells to sustain an ongoing autoimmune responses [104]. Finally, mice with intestinal epithelial cell-specific deficiency of caspase-8 or FADD (Fas-Associated protein with Death Domain) have been shown to spontaneously develop terminal ileitis or colitis associated with loss of Paneth cell and epithelial cell necrosis [105, 106]. In these mice, commensal bacteria-induced TNF-α trigger the programmed necrosis of intestinal epithelial cells which drives the inflammatory response and epithelial inflammation. In aggregate, these data suggest that the T cell population is also dynamically tuned by antigen-independent factors elicited by commensal bacteria.

Why might dynamic regulation of adaptive immunity to commensal bacteria occur? One possibility is that pathogenic bacteria are encountered episodically, requiring memory, whereas commensal bacteria are always in contact with the host. A dynamically regulated Treg cell population would be tuned to the current commensal microbiota and be more responsive to a large influx of commensal antigens from mucosal injury, thereby limiting effector T cell activation and excessive inflammation. By contrast, bacteria that are new to the intestinal tract would not trigger pre-existing Treg or effector T cells, but require de novo selection of effector versus regulatory T cell responses. This would allow more rapid effector responses to pathogens and limit the buildup of effector T cells responsive to commensal bacteria that might trigger IBD. Future experiments are required to address the conjecture that T cell responses to commensal bacteria are amnestic and dynamically regulated by clonal competition for antigen.

9. How is tolerance to commensal bacteria broken?

For most individuals, tolerance to commensal bacteria remains intact throughout their lifetime. However, approximately 0.44 % of individuals break tolerance and develop IBD [107]. Genome wide association studies (GWAS) have clearly identified a number of genetic risk factors for IBD that affect intestinal epithelial function, general immune regulation, and innate immune function [108, 109]. Defects in non-T cell related genes may increase bacterial translocation or outgrowth, triggering an inflammatory response from otherwise normal T cells. Defects in T cell related genes, such as HLA, suggest that T cell interactions with commensal bacteria may also be abnormal in IBD [108]. Thus, breakage in T cell tolerance to commensal bacteria could include a primary T cell defect or arise secondary to other perturbations of intestinal immune homeostasis.

In addition to genetic factors, an intriguing question is whether environmental insults can break tolerance. This is suggested by the observation that IBD is increasing in geographic areas such as North America [107]. An increased risk of IBD has also been associated with recent gastrointestinal infections [110]. While commensal bacterial exposure during mucosal breaches may be reduced by a containment structure referred to as intraluminal cast comprised of monocytes and neutrophils [111], intestinal infections can expose the immune system to a variety of commensal bacteria [112]. Moreover, gut infections are associated with dysbiosis with significant shifts in microbiota composition. For example, γ-proteobacteria can become dominant due to their ability to thrive under inflammatory condition [113, 114]. Thus, infection may result in the exposure to the immune system of previously encountered commensals as well as those that typically do not have access during homeostasis.

A recent study convincingly showed that exposure of commensals to the immune system can occur during mucosal breaches [53]. They used CBir TCR transgenic T cells that recognize flagellin expressed by certain commensals including the Clostridium cluster XIV class of bacteria. Interestingly, these T cells typically possess a naïve phenotype during homeostasis, suggesting that they are not routinely exposed to antigen. However, barrier breach results in their development into Th1 cells during a highly Th1 polarizing T. gondii infection, or Th17 cells after DSS administration. These T cells persist long term in both the intestinal and secondary lymphoid tissues, and respond like memory T cells upon rechallenge. Although physical segregation between the microbiota and immune system is rapidly restored after resolution of infection, the long-term presence of commensal-specific memory T cells may fundamentally alter the balance of tolerance. One could speculate that over time, multiple infections may lead to the expansion of commensal-bacteria reactive effector T cells, potentially leading to a feed-forward loop in which these T cells can themselves overwhelm Treg cells and cause enough inflammation to lead to barrier breach and further antigen presentation [115]. This could create a chronic and self-sustaining inflammatory state, perhaps culminating in IBD.

And yet, intestinal infections associated with diarrhea are common and often do not trigger IBD [110, 116]. Nor do other intestinal disorders such as diverticulitis or appendicitis that might be predicted to result in increased exposure to commensal bacteria. Perhaps the experience with CBir is not representative of most T cell responses during infection as its antigen is not constitutively presented to the immune system. Antigens that are constitutively presented may have already triggered the appropriate effector or regulatory T cell response. Additionally, the CBir antigen is flagellin, a TLR5 ligand, and may not be representative of most commensal bacterial ligands. Thus, it remains unclear the extent that infection or other injuries that result in mucosal barrier breakdown affects the balance between effector and regulatory T cell responses to commensal bacteria.

10. Summary

Recent work has demonstrated that the adaptive immune system has continuous interactions with commensal bacteria to induce both regulatory and effector T cells that promote tolerance and immunity, respectively The differences in the Treg versus effector cell TCR repertoires suggest that these T cell populations perform unique functions to maintain host health. However, many questions remain. What are the mechanisms by which the immune system determines regulatory versus effector cell differentiation? How is this affected by infections or other diseases of the intestinal tract? What is the role of effector cells in maintaining a healthy immune environment? Addressing these questions is of considerable interest to understanding the fundamental immunologic question of how we establish immune tolerance to foreign antigens, but also raises the possibility that such knowledge may be useful for the treatment or prevention of IBD or other allergic and autoimmune diseases of the intestines.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Teresa Ai and Ben Solomon (all Wash. U.) for critical comments. C.S.H. is supported by grants from NIAID, NIDDK, CCFA, and Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brestoff JR, Artis D. Commensal bacteria at the interface of host metabolism and the immune system. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:676–684. doi: 10.1038/ni.2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Intestinal homeostasis and its breakdown in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nature10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powrie F, Mason D. OX-22high CD4+ T cells induce wasting disease with multiple organ pathology: prevention by the OX-22low subset. J Exp Med. 1990;172:1701–1708. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.6.1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wing K, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells exert checks and balances on self tolerance and autoimmunity. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:7–13. doi: 10.1038/ni.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Josefowicz SZ, Lu LF, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T Cells: Mechanisms of Differentiation and Function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012 doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malek TR. The biology of interleukin-2. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:453–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Contractor NV, Bassiri H, Reya T, Park AY, Baumgart DC, Wasik MA, Emerson SG, Carding SR. Lymphoid hyperplasia , autoimmunity, and compromised intestinal intraepithelial lymphocyte development in colitis-free gnotobiotic IL-2-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1998;160:385–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schultz M, Tonkonogy SL, Sellon RK, Veltkamp C, Godfrey VL, Kwon J, Grenther WB, Balish E, Horak I, Sartor RB. IL-2-deficient mice raised under germfree conditions develop delayed mild focal intestinal inflammation. The American journal of physiology. 1999;276:G1461–G1472. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.6.G1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadlack B, Merz H, Schorle H, Schimpl A, Feller AC, Horak I. Ulcerative colitis-like disease in mice with a disrupted interleukin-2 gene. Cell. 1993;75:253–261. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80067-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chinen T, Volchkov PY, Chervonsky AV, Rudensky AY. A critical role for regulatory T cell-mediated control of inflammation in the absence of commensal microbiota. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2323–2330. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Obata Y, Furusawa Y, Endo TA, Sharif J, Takahashi D, Atarashi K, Nakayama M, Onawa S, Fujimura Y, Takahashi M, Ikawa T, Otsubo T, Kawamura YI, Dohi T, Tajima S, Masumoto H, Ohara O, Honda K, Hori S, Ohno H, Koseki H, Hase K. The epigenetic regulator Uhrf1 facilitates the proliferation and maturation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:571–579. doi: 10.1038/ni.2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asseman C, Read S, Powrie F. Colitogenic Th1 cells are present in the antigen-experienced T cell pool in normal mice: control by CD4+ regulatory T cells and IL-10. J Immunol. 2003;171:971–978. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ai TL, Solomon BD, Hsieh CS. T-cell selection and intestinal homeostasis. Immunol Rev. 2014;259:60–74. doi: 10.1111/imr.12171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yadav M, Stephan S, Bluestone JA. Peripherally induced tregs - role in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity. Frontiers in immunology. 2013;4:232. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bilate AM, Lafaille JJ. Induced CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in immune tolerance. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:733–758. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klein L, Jovanovic K. Regulatory T cell lineage commitment in the thymus. Semin Immunol. 2011;23:401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh CS, Lee HM, Lio CW. Selection of regulatory T cells in the thymus. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:157–167. doi: 10.1038/nri3155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun CM, Hall JA, Blank RB, Bouladoux N, Oukka M, Mora JR, Belkaid Y. Small intestine lamina propria dendritic cells promote de novo generation of Foxp3 T reg cells via retinoic acid. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1775–1785. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thornton AM, Korty PE, Tran DQ, Wohlfert EA, Murray PE, Belkaid Y, Shevach EM. Expression of Helios, an Ikaros transcription factor family member, differentiates thymic-derived from peripherally induced Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:3433–3441. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiss JM, Bilate AM, Gobert M, Ding Y, Curotto de Lafaille MA, Parkhurst CN, Xiong H, Dolpady J, Frey AB, Ruocco MG, Yang Y, Floess S, Huehn J, Oh S, Li MO, Niec RE, Rudensky AY, Dustin ML, Littman DR, Lafaille JJ. Neuropilin 1 is expressed on thymus-derived natural regulatory T cells, but not mucosa-generated induced Foxp3+ T reg cells. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1723–1742. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120914. S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Shima T, Imaoka A, Kuwahara T, Momose Y, Cheng G, Yamasaki S, Saito T, Ohba Y, Taniguchi T, Takeda K, Hori S, Ivanov II, Umesaki Y, Itoh K, Honda K. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science. 2011;331:337–341. doi: 10.1126/science.1198469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lathrop SK, Bloom SM, Rao SM, Nutsch K, Lio CW, Santacruz N, Peterson DA, Stappenbeck TS, Hsieh CS. Peripheral education of the immune system by colonic commensal microbiota. Nature. 2011;478:250–254. doi: 10.1038/nature10434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haribhai D, Williams JB, Jia S, Nickerson D, Schmitt EG, Edwards B, Ziegelbauer J, Yassai M, Li SH, Relland LM, Wise PM, Chen A, Zheng YQ, Simpson PM, Gorski J, Salzman NH, Hessner MJ, Chatila TA, Williams CB. A requisite role for induced regulatory T cells in tolerance based on expanding antigen receptor diversity. Immunity. 2011;35:109–122. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Josefowicz SZ, Niec RE, Kim HY, Treuting P, Chinen T, Zheng Y, Umetsu DT, Rudensky AY. Extrathymically generated regulatory T cells control mucosal TH2 inflammation. Nature. 2012;482:395–399. doi: 10.1038/nature10772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng Y, Chaudhry A, Kas A, deRoos P, Kim JM, Chu TT, Corcoran L, Treuting P, Klein U, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T-cell suppressor program co-opts transcription factor IRF4 to control T(H)2 responses. Nature. 2009;458:351–6. doi: 10.1038/nature07674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gottschalk RA, Corse E, Allison JP. Expression of Helios in peripherally induced Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2012;188:976–980. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akimova T, Beier UH, Wang L, Levine MH, Hancock WW. Helios expression is a marker of T cell activation and proliferation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24226. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cebula A, Seweryn M, Rempala GA, Pabla SS, McIndoe RA, Denning TL, Bry L, Kraj P, Kisielow P, Ignatowicz L. Thymus-derived regulatory T cells contribute to tolerance to commensal microbiota. Nature. 2013;497:258–262. doi: 10.1038/nature12079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Oshima K, Suda W, Nagano Y, Nishikawa H, Fukuda S, Saito T, Narushima S, Hase K, Kim S, Fritz JV, Wilmes P, Ueha S, Matsushima K, Ohno H, Olle B, Sakaguchi S, Taniguchi T, Morita H, Hattori M, Honda K. Treg induction by a rationally selected mixture of Clostridia strains from the human microbiota. Nature. 2013;500:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature12331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geuking MB, Cahenzli J, Lawson MA, Ng DC, Slack E, Hapfelmeier S, McCoy KD, Macpherson AJ. Intestinal bacterial colonization induces mutualistic regulatory T cell responses. Immunity. 2011;34:794–806. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Livingston M, Loach D, Wilson M, Tannock GW, Baird M. Gut commensal Lactobacillus reuteri 100-23 stimulates an immunoregulatory response. Immunology and cell biology. 2010;88:99–102. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mucida D, Park Y, Kim G, Turovskaya O, Scott I, Kronenberg M, Cheroutre H. Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science. 2007;317:256–260. doi: 10.1126/science.1145697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benson MJ, Pino-Lagos K, Rosemblatt M, Noelle RJ. All-trans retinoic acid mediates enhanced T reg cell growth, differentiation, and gut homing in the face of high levels of co-stimulation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1765–1774. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hill JA, Hall JA, Sun CM, Cai Q, Ghyselinck N, Chambon P, Belkaid Y, Mathis D, Benoist C. Retinoic acid enhances Foxp3 induction indirectly by relieving inhibition from CD4+CD44hi Cells. Immunity. 2008;29:758–770. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nolting J, Daniel C, Reuter S, Stuelten C, Li P, Sucov H, Kim BG, Letterio JJ, Kretschmer K, Kim HJ, von Boehmer H. Retinoic acid can enhance conversion of naive into regulatory T cells independently of secreted cytokines. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2131–2139. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Carcamo CV, Hall J, Sun CM, Belkaid Y, Powrie F. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1757–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manicassamy S, Reizis B, Ravindran R, Nakaya H, Salazar-Gonzalez RM, Wang YC, Pulendran B. Activation of beta-catenin in dendritic cells regulates immunity versus tolerance in the intestine. Science. 2010;329:849–853. doi: 10.1126/science.1188510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shan M, Gentile M, Yeiser JR, Walland AC, Bornstein VU, Chen K, He B, Cassis L, Bigas A, Cols M, Comerma L, Huang B, Blander JM, Xiong H, Mayer L, Berin C, Augenlicht LH, Velcich A, Cerutti A. Mucus enhances gut homeostasis and oral tolerance by delivering immunoregulatory signals. Science. 2013;342:447–453. doi: 10.1126/science.1237910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arpaia N, Campbell C, Fan X, Dikiy S, van der Veeken J, Deroos P, Liu H, Cross JR, Pfeffer K, Coffer PJ, Rudensky AY. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature12726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, Endo TA, Nakato G, Takahashi D, Nakanishi Y, Uetake C, Kato K, Kato T, Takahashi M, Fukuda NN, Murakami S, Miyauchi E, Hino S, Atarashi K, Onawa S, Fujimura Y, Lockett T, Clarke JM, Topping DL, Tomita M, Hori S, Ohara O, Morita T, Koseki H, Kikuchi J, Honda K, Hase K, Ohno H. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nature12721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh N, Gurav A, Sivaprakasam S, Brady E, Padia R, Shi H, Thangaraju M, Prasad PD, Manicassamy S, Munn DH, Lee JR, Offermanns S, Ganapathy V. Activation of Gpr109a, receptor for niacin and the commensal metabolite butyrate, suppresses colonic inflammation and carcinogenesis. Immunity. 2014;40:128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Bohlooly YM, Glickman JN, Garrett WS. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science. 2013;341:569–573. doi: 10.1126/science.1241165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Round JL, Lee SM, Li J, Tran G, Jabri B, Chatila TA, Mazmanian SK. The Toll-like receptor 2 pathway establishes colonization by a commensal of the human microbiota. Science. 2011;332:974–977. doi: 10.1126/science.1206095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maynard CL, Weaver CT. Intestinal effector T cells in health and disease. Immunity. 2009;31:389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Belkaid Y, Hand TW. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell. 2014;157:121–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Niess JH, Leithauser F, Adler G, Reimann J. Commensal gut flora drives the expansion of proinflammatory CD4 T cells in the colonic lamina propria under normal and inflammatory conditions. J Immunol. 2008;180:559–568. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hall JA, Bouladoux N, Sun CM, Wohlfert EA, Blank RB, Zhu Q, Grigg ME, Berzofsky JA, Belkaid Y. Commensal DNA limits regulatory T cell conversion and is a natural adjuvant of intestinal immune responses. Immunity. 2008;29:637–649. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ivanov II, Atarashi K, Manel N, Brodie EL, Shima T, Karaoz U, Wei D, Goldfarb KC, Santee CA, Lynch SV, Tanoue T, Imaoka A, Itoh K, Takeda K, Umesaki Y, Honda K, Littman DR. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell. 2009;139:485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang Y, Torchinsky MB, Gobert M, Xiong H, Xu M, Linehan JL, Alonzo F, Ng C, Chen A, Lin X, Sczesnak A, Liao JJ, Torres VJ, Jenkins MK, Lafaille JJ, Littman DR. Focused specificity of intestinal T17 cells towards commensal bacterial antigens. Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nature13279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goto Y, Panea C, Nakato G, Cebula A, Lee C, Diez MG, Laufer TM, Ignatowicz L, Ivanov II. Segmented filamentous bacteria antigens presented by intestinal dendritic cells drive mucosal th17 cell differentiation. Immunity. 2014;40:594–607. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gottschalk RA, Corse E, Allison JP. TCR ligand density and affinity determine peripheral induction of Foxp3 in vivo. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1701–1711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Turner MS, Kane LP, Morel PA. Dominant role of antigen dose in CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cell induction and expansion. J Immunol. 2009;183:4895–4903. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hand TW, Dos Santos LM, Bouladoux N, Molloy MJ, Pagan AJ, Pepper M, Maynard CL, Elson CO, 3rd, Belkaid Y. Acute gastrointestinal infection induces long-lived microbiota-specific T cell responses. Science. 2012;337:1553–1556. doi: 10.1126/science.1220961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hadis U, Wahl B, Schulz O, Hardtke-Wolenski M, Schippers A, Wagner N, Muller W, Sparwasser T, Forster R, Pabst O. Intestinal tolerance requires gut homing and expansion of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in the lamina propria. Immunity. 2011;34:237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shiomi H, Masuda A, Nishiumi S, Nishida M, Takagawa T, Shiomi Y, Kutsumi H, Blumberg RS, Azuma T, Yoshida M. Gamma interferon produced by antigen-specific CD4+ T cells regulates the mucosal immune responses to Citrobacter rodentium infection. Infect Immun. 2010;78:2653–2666. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01343-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rivas MN, Koh YT, Chen A, Nguyen A, Lee YH, Lawson G, Chatila TA. MyD88 is critically involved in immune tolerance breakdown at environmental interfaces of Foxp3-deficient mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012;122:1933–1947. doi: 10.1172/JCI40591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Hao L, Medzhitov R. Role of Toll-like Receptors in Spontaneous Commensal-Dependent Colitis. Immunity. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Manicassamy S, Ravindran R, Deng J, Oluoch H, Denning TL, Kasturi SP, Rosenthal KM, Evavold BD, Pulendran B. Toll-like receptor 2-dependent induction of vitamin A-metabolizing enzymes in dendritic cells promotes T regulatory responses and inhibits autoimmunity. Nature medicine. 2009;15:401–409. doi: 10.1038/nm.1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bouladoux N, Hall JA, Grainger JR, dos Santos LM, Kann MG, Nagarajan V, Verthelyi D, Belkaid Y. Regulatory role of suppressive motifs from commensal DNA. Mucosal Immunol. 2012;5:623–634. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Coombes JL, Powrie F. Dendritic cells in intestinal immune regulation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:435–446. doi: 10.1038/nri2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grainger JR, Askenase MH, Guimont-Desrochers F, da Fonseca DM, Belkaid Y. Contextual functions of antigen-presenting cells in the gastrointestinal tract. Immunol Rev. 2014;259:75–87. doi: 10.1111/imr.12167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kinnebrew MA, Buffie CG, Diehl GE, Zenewicz LA, Leiner I, Hohl TM, Flavell RA, Littman DR, Pamer EG. Interleukin 23 production by intestinal CD103(+)CD11b(+) dendritic cells in response to bacterial flagellin enhances mucosal innate immune defense. Immunity. 2012;36:276–287. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Satpathy AT, Briseno CG, Lee JS, Ng D, Manieri NA, Kc W, Wu X, Thomas SR, Lee WL, Turkoz M, McDonald KG, Meredith MM, Song C, Guidos CJ, Newberry RD, Ouyang W, Murphy TL, Stappenbeck TS, Gommerman JL, Nussenzweig MC, Colonna M, Kopan R, Murphy KM. Notch2-dependent classical dendritic cells orchestrate intestinal immunity to attaching-and-effacing bacterial pathogens. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:937–948. doi: 10.1038/ni.2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Welty NE, Staley C, Ghilardi N, Sadowsky MJ, Igyarto BZ, Kaplan DH. Intestinal lamina propria dendritic cells maintain T cell homeostasis but do not affect commensalism. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2011–2024. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lewis KL, Caton ML, Bogunovic M, Greter M, Grajkowska LT, Ng D, Klinakis A, Charo IF, Jung S, Gommerman JL, Ivanov II, Liu K, Merad M, Reizis B. Notch2 receptor signaling controls functional differentiation of dendritic cells in the spleen and intestine. Immunity. 2011;35:780–791. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Farache J, Zigmond E, Shakhar G, Jung S. Contributions of dendritic cells and macrophages to intestinal homeostasis and immune defense. Immunology and cell biology. 2013;91:232–239. doi: 10.1038/icb.2012.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shouval DS, Biswas A, Goettel JA, McCann K, Conaway E, Redhu NS, Mascanfroni ID, Al Adham Z, Lavoie S, Ibourk M, Nguyen DD, Samsom JN, Escher JC, Somech R, Weiss B, Beier R, Conklin LS, Ebens CL, Santos FG, Ferreira AR, Sherlock M, Bhan AK, Muller W, Mora JR, Quintana FJ, Klein C, Muise AM, Horwitz BH, Snapper SB. Interleukin-10 Receptor Signaling in Innate Immune Cells Regulates Mucosal Immune Tolerance and Anti-Inflammatory Macrophage Function. Immunity. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mortha A, Chudnovskiy A, Hashimoto D, Bogunovic M, Spencer SP, Belkaid Y, Merad M. Microbiota-dependent crosstalk between macrophages and ILC3 promotes intestinal homeostasis. Science. 2014;343:1249288. doi: 10.1126/science.1249288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hepworth MR, Monticelli LA, Fung TC, Ziegler CG, Grunberg S, Sinha R, Mantegazza AR, Ma HL, Crawford A, Angelosanto JM, Wherry EJ, Koni PA, Bushman FD, Elson CO, Eberl G, Artis D, Sonnenberg GF. Innate lymphoid cells regulate CD4+ T-cell responses to intestinal commensal bacteria. Nature. 2013;498:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature12240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Khounlotham M, Kim W, Peatman E, Nava P, Medina-Contreras O, Addis C, Koch S, Fournier B, Nusrat A, Denning TL, Parkos CA. Compromised intestinal epithelial barrier induces adaptive immune compensation that protects from colitis. Immunity. 2012;37:563–573. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Suzuki K, Meek B, Doi Y, Muramatsu M, Chiba T, Honjo T, Fagarasan S. Aberrant expansion of segmented filamentous bacteria in IgA-deficient gut. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:1981–1986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307317101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sonnenberg GF, Monticelli LA, Alenghat T, Fung TC, Hutnick NA, Kunisawa J, Shibata N, Grunberg S, Sinha R, Zahm AM, Tardif MR, Sathaliyawala T, Kubota M, Farber DL, Collman RG, Shaked A, Fouser LA, Weiner DB, Tessier PA, Friedman JR, Kiyono H, Bushman FD, Chang KM, Artis D. Innate lymphoid cells promote anatomical containment of lymphoid-resident commensal bacteria. Science. 2012;336:1321–1325. doi: 10.1126/science.1222551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Garrett WS, Lord GM, Punit S, Lugo-Villarino G, Mazmanian SK, Ito S, Glickman JN, Glimcher LH. Communicable ulcerative colitis induced by T-bet deficiency in the innate immune system. Cell. 2007;131:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mangan PR, Harrington LE, O’Quinn DB, Helms WS, Bullard DC, Elson CO, Hatton RD, Wahl SM, Schoeb TR, Weaver CT. Transforming growth factor-beta induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature. 2006;441:231–234. doi: 10.1038/nature04754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou L, Tadokoro CE, Lepelley A, Lafaille JJ, Cua DJ, Littman DR. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wick EC, Sears CL. Bacteroides spp. and diarrhea. Current opinion in infectious diseases. 2010;23:470–474. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833da1eb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen K, McAleer JP, Lin Y, Paterson DL, Zheng M, Alcorn JF, Weaver CT, Kolls JK. Th17 cells mediate clade-specific, serotype-independent mucosal immunity. Immunity. 2011;35:997–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25) Journal of Immunology. 1995;155:1151–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim JM, Rasmussen JP, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells prevent catastrophic autoimmunity throughout the lifespan of mice. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:191–197. doi: 10.1038/ni1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Macpherson AJ, McCoy KD. Stratification and compartmentalisation of immunoglobulin responses to commensal intestinal microbes. Semin Immunol. 2013;25:358–363. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zimmermann K, Haas A, Oxenius A. Systemic antibody responses to gut microbes in health and disease. Gut microbes. 2012;3:42–47. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Benckert J, Schmolka N, Kreschel C, Zoller MJ, Sturm A, Wiedenmann B, Wardemann H. The majority of intestinal IgA+ and IgG+ plasmablasts in the human gut are antigen-specific. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:1946–1955. doi: 10.1172/JCI44447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Peterson DA, McNulty NP, Guruge JL, Gordon JI. IgA response to symbiotic bacteria as a mediator of gut homeostasis. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:328–339. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Macpherson AJ, Gatto D, Sainsbury E, Harriman GR, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. A primitive T cell-independent mechanism of intestinal mucosal IgA responses to commensal bacteria. Science. 2000;288:2222–2226. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5474.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lindner C, Wahl B, Fohse L, Suerbaum S, Macpherson AJ, Prinz I, Pabst O. Age, microbiota, and T cells shape diverse individual IgA repertoires in the intestine. J Exp Med. 2012;209:365–377. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cong Y, Feng T, Fujihashi K, Schoeb TR, Elson CO. A dominant, coordinated T regulatory cell-IgA response to the intestinal microbiota. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:19256–19261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812681106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tsuji M, Komatsu N, Kawamoto S, Suzuki K, Kanagawa O, Honjo T, Hori S, Fagarasan S. Preferential generation of follicular B helper T cells from Foxp3+ T cells in gut Peyer’s patches. Science. 2009;323:1488–1492. doi: 10.1126/science.1169152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Linterman MA, Pierson W, Lee SK, Kallies A, Kawamoto S, Rayner TF, Srivastava M, Divekar DP, Beaton L, Hogan JJ, Fagarasan S, Liston A, Smith KG, Vinuesa CG. Foxp3+ follicular regulatory T cells control the germina l center response. Nature medicine. 2011;17:975–982. doi: 10.1038/nm.2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chung Y, Tanaka S, Chu F, Nurieva RI, Martinez GJ, Rawal S, Wang YH, Lim H, Reynolds JM, Zhou XH, Fan HM, Liu ZM, Neelapu SS, Dong C. Follicular regulatory T cells expressing Foxp3 and Bcl-6 suppress germinal center reactions. Nature medicine. 2011;17:983–988. doi: 10.1038/nm.2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lecuyer E, Rakotobe S, Lengline-Garnier H, Lebreton C, Picard M, Juste C, Fritzen R, Eberl G, McCoy KD, Macpherson AJ, Reynaud CA, Cerf-Bensussan N, Gaboriau-Routhiau V. Segmented filamentous bacterium uses secondary and tertiary lymphoid tissues to induce gut IgA and specific T helper 17 cell responses. Immunity. 2014;40:608–620. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hirota K, Turner JE, Villa M, Duarte JH, Demengeot J, Steinmetz OM, Stockinger B. Plasticity of Th17 cells in Peyer’s patches is responsible for the induction of T cell-dependent IgA responses. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:372–379. doi: 10.1038/ni.2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hapfelmeier S, Lawson MA, Slack E, Kirundi JK, Stoel M, Heikenwalder M, Cahenzli J, Velykoredko Y, Balmer ML, Endt K, Geuking MB, Curtiss R, 3rd, McCoy KD, Macpherson AJ. Reversible microbial colonization of germ-free mice reveals the dynamics of IgA immune responses. Science. 2010;328:1705–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1188454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Huard B, McKee T, Bosshard C, Durual S, Matthes T, Myit S, Donze O, Frossard C, Chizzolini C, Favre C, Zubler R, Guyot JP, Schneider P, Roosnek E. APRIL secreted by neutrophils binds to heparan sulfate proteoglycans to create plasma cell niches in human mucosa. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118:2887–2895. doi: 10.1172/JCI33760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pinto D, Montani E, Bolli M, Garavaglia G, Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A, Jarrossay D. A functional BCR in human IgA and IgM plasma cells. Blood. 2013;121:4110–4114. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-459289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lathrop SK, Santacruz NA, Pham D, Luo J, Hsieh CS. Antigen-specific peripheral shaping of the natural regulatory T cell population. J Exp Med. 2008;205:3105–3117. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Samy ET, Setiady YY, Ohno K, Pramoonjago P, Sharp C, Tung KS. The role of physiological self-antigen in the acquisition and maintenance of regulatory T-cell function. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:170–184. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ivanov II, Frutos Rde L, Manel N, Yoshinaga K, Rifkin DB, Sartor RB, Finlay BB, Littman DR. Specific microbiota direct the differentiation of IL-17-producing T-helper cells in the mucosa of the small intestine. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:337–349. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Spahn TW, Ross M, von Eiff C, Maaser C, Spieker T, Kannengiesser K, Domschke W, Kucharzik T. CD4+ T cells transfer resistance against Citrobacter rodentium-induced infectious colitis by induction of Th 1 immunity. Scandinavian journal of immunology. 2008;67:238–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.02063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rosenblum MD, Gratz IK, Paw JS, Lee K, Marshak-Rothstein A, Abbas AK. Response to self antigen imprints regulatory memory in tissues. Nature. 2011;480:538–542. doi: 10.1038/nature10664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ahern PP, Schiering C, Buonocore S, McGeachy MJ, Cua DJ, Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Interleukin-23 drives intestinal inflammation through direct activity on T cells. Immunity. 2010;33:279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.DePaolo RW, Abadie V, Tang F, Fehlner-Peach H, Hall JA, Wang W, Marietta EV, Kasarda DD, Waldmann TA, Murray JA, Semrad C, Kupfer SS, Belkaid Y, Guandalini S, Jabri B. Co-adjuvant effects of retinoic acid and IL-15 induce inflammatory immunity to dietary antigens. Nature. 2011;471:220–224. doi: 10.1038/nature09849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hall JA, Cannons JL, Grainger JR, Dos Santos LM, Hand TW, Naik S, Wohlfert EA, Chou DB, Oldenhove G, Robinson M, Grigg ME, Kastenmayer R, Schwartzberg PL, Belkaid Y. Essential role for retinoic acid in the promotion of CD4(+) T cell effector responses via retinoic acid receptor alpha. Immunity. 2011;34:435–447. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chappert P, Bouladoux N, Naik S, Schwartz RH. Specific gut commensal flora locally alters T cell tuning to endogenous ligands. Immunity. 2013;38:1198–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gunther C, Martini E, Wittkopf N, Amann K, Weigmann B, Neumann H, Waldner MJ, Hedrick SM, Tenzer S, Neurath MF, Becker C. Caspase-8 regulates TNF-alpha-induced epithelial necroptosis and terminal ileitis. Nature. 2011;477:335–339. doi: 10.1038/nature10400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Welz PS, Wullaert A, Vlantis K, Kondylis V, Fernandez-Majada V, Ermolaeva M, Kirsch P, Sterner-Kock A, van Loo G, Pasparakis M. FADD prevents RIP3-mediated epithelial cell necrosis and chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2011;477:330–334. doi: 10.1038/nature10273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, Ollendorf D, Bousvaros A, Grand RJ, Finkelstein JA. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2007;5:1424–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, Hui KY, Lee JC, Schumm LP, Sharma Y, Anderson CA, Essers J, Mitrovic M, Ning K, Cleynen I, Theatre E, Spain SL, Raychaudhuri S, Goyette P, Wei Z, Abraham C, Achkar JP, Ahmad T, Amininejad L, Ananthakrishnan AN, Andersen V, Andrews JM, Baidoo L, Balschun T, Bampton PA, Bitton A, Boucher G, Brand S, Buning C, Cohain A, Cichon SD, Amato M, De Jong D, Devaney KL, Dubinsky M, Edwards C, Ellinghaus D, Ferguson LR, Franchimont D, Fransen K, Gearry R, Georges M, Gieger C, Glas J, Haritunians T, Hart A, Hawkey C, Hedl M, Hu X, Karlsen TH, Kupcinskas L, Kugathasan S, Latiano A, Laukens D, Lawrance IC, Lees CW, Louis E, Mahy G, Mansfield J, Morgan AR, Mowat C, Newman W, Palmieri O, Ponsioen CY, Potocnik U, Prescott NJ, Regueiro M, Rotter JI, Russell RK, Sanderson JD, Sans M, Satsangi J, Schreiber S, Simms LA, Sventoraityte J, Targan SR, Taylor KD, Tremelling M, Verspaget HW, De Vos M, Wijmenga C, Wilson DC, Winkelmann J, Xavier RJ, Zeissig S, Zhang B, Zhang CK, Zhao H, International IBDGC, Silverberg MS, Annese V, Hakonarson H, Brant SR, Radford-Smith G, Mathew CG, Rioux JD, et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491:119–24. doi: 10.1038/nature11582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Khor B, Gardet A, Xavier RJ. Genetics and pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:307–317. doi: 10.1038/nature10209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Irving PM, Gibson PR. Infections and IBD. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:18–27. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Molloy MJ, Grainger JR, Bouladoux N, Hand TW, Koo LY, Naik S, Quinones M, Dzutsev AK, Gao JL, Trinchieri G, Murphy PM, Belkaid Y. Intraluminal containment of commensal outgrowth in the gut during infection-induced dysbiosis. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:318–328. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Brenchley JM, Douek DC. Microbial translocation across the GI tract. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:149–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Raetz M, Hwang SH, Wilhelm CL, Kirkland D, Benson A, Sturge CR, Mirpuri J, Vaishnava S, Hou B, Defranco AL, Gilpin CJ, Hooper LV, Yarovinsky F. Parasite-induced TH1 cells and intestinal dysbiosis cooperate in IFN-gamma-dependent elimination of Paneth cells. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:136–142. doi: 10.1038/ni.2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Winter SE, Winter MG, Xavier MN, Thiennimitr P, Poon V, Keestra AM, Laughlin RC, Gomez G, Wu J, Lawhon SD, Popova IE, Parikh SJ, Adams LG, Tsolis RM, Stewart VJ, Baumler AJ. Host-derived nitrate boosts growth of E. coli in the inflamed gut. Science. 2013;339:708–711. doi: 10.1126/science.1232467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Belkaid Y, Bouladoux N, Hand TW. Effector and memory T cell responses to commensal bacteria. Trends in immunology. 2013;34:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Vernacchio L, Vezina RM, Mitchell AA, Lesko SM, Plaut AG, Acheson DW. Diarrhea in American infants and young children in the community setting: incidence, clinical presentation and microbiology. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2006;25:2–7. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000195623.57945.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]