Abstract

Background

With the steady growth in Medicaid enrollment since the recent recession, concerns have been raised about care for newborns with complications. This paper uses all-payer administrative data from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), to examine trends from 2002 through 2009 in complicated newborn hospital stays, and explores the relationship between expected sources of payment and reasons for hospitalizations.

Methods

Trends in complicated newborn stays, expected sources of payment, costs, and length of stay were examined. A logistic regression was conducted to explore likely payer source for the most prevalent diagnoses in 2009.

Results

Complicated births and hospital discharges within 30 days of birth remained relatively constant between 2002 and 2009, but average costs per discharge increased substantially (p<.001 for trend). Most strikingly, over time, the proportion of complicated births billed to Medicaid increased, while the proportion paid by private payers decreased. Among complicated births, the most prevalent diagnoses were preterm birth/low birth weight (23%), respiratory distress (18%), and jaundice (10%). The top two diagnoses (41% of newborns) accounted for 61% of the aggregate cost. For infants with complications, those with Medicaid were more likely to be complicated due to preterm birth/low birth weight and respiratory distress, while those with private insurance were more likely to be complicated due to jaundice.

Conclusions

State Medicaid programs are paying for an increasing proportion of births and costly complicated births. Policies to prevent common birth complications have the potential to reduce costs for public programs and improve birth outcomes.

Keywords: complicated births, newborns, preterm birth, low birth weight, Medicaid, HCUP

Introduction

Complicated births are expensive and have long-term consequences for the health of both mothers and infants. Nationwide, maternal and perinatal complications are among the most prevalent diagnoses for women of childbearing age (Elixhauser & Wier, 2011, May; Martin, Hamilton, & Ventura, 2012; Wier & Andrews, 2011, March). Birth complications are an especially important area for Medicaid, in that two out of every three adult women Medicaid beneficiaries are of childbearing age (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2012, January), and about half of all Medicaid hospital stays are for pregnancy, childbirth, and newborns (Stranges, Ryan, & Elixhauser, 2011, January). Furthermore, Medicaid pays for approximately 45 percent of all births in the United States (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2012,June).

The high costs of complicated births result in expensive hospital stays (Wier & Andrews, 2011, March). A previous analysis of Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) data indicated that in 2006, hospital stays billed to Medicaid cost $22 billion for maternal conditions related to pregnancy and $19 billion for conditions related to the newborn. However, health care costs are not the only expenditures associated with birth complications; other non-healthcare related costs, such as overall loss in productivity, also add to the total burden of complicated births. The Institute of Medicine estimated that preterm births alone cost the United States $26.2 billion in 2005 when accounting for health care along with other costs (Behrman & Butler, 2007).

Moreover, the effects of poor birth outcomes extend beyond the neonatal period: they affect a child’s life course and health trajectory (Behrman & Butler, 2007; Wise, 2004) and are associated with lifelong conditions, including learning and behavioral problems, asthma, and increasing evidence of lifelong cardiovascular issues (McCormick, Litt, Smith, & Zupancic, 2011). This creates a significant financial burden on families who care for infants born with complications (Wise, 2004).

In response to the cost and high prevalence of poor birth outcomes—which are higher in the United States than other developed countries (IOM, 2013)—a number of initiatives have been launched by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and others aimed at improving birth outcomes (CMS, 2013; HRSA, 2013). In the future, it will be important to follow trends in complicated births to ascertain effects.

Limited studies exist on trends in hospital stays related to births in the U.S. In their analysis of HCUP data, Friedman et al. (2011) reported reductions in births overall, particularly births to adolescent mothers, but incidences and implications of trends in complicated births were not examined. Nor were trends in complications examined in the context of payer type or particular diagnoses. Other analyses examining complicated births have focused on maternal hospitalizations (Elixhauser & Wier, 2011, May) or on cross-sectional data (Elixhauser & Wier, 2011, May; Russell et al., 2007) and not on trends, expected payer sources, or implications for health care policy and spending.

This study is intended to fill gaps in prior research and to provide a baseline against which to evaluate the effects of recent efforts to improve birth outcomes. This baseline will be especially valuable given the expected growth of public coverage, both through Medicaid expansion and the subsidized coverage in the Insurance Exchanges (Kenney, Lynch, Cook, & Phong, 2010).

The purpose of this paper is two-fold. First, the paper examines overall trends in utilization, costs, and expected source of payment for complicated newborn hospital stays using all-payer discharge data from 2002 through 2009. Second, the paper provides an in-depth look at the most prevalent diagnoses for complicated newborn stays by expected payer type in 2009.

Data and Methods

Data Source

The data source is the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (HCUP, 2002–2009) for the 8 years 2002–2009. Each NIS contains approximately 8 million discharges, weighted to approximate 38 to 39 million discharges. Each discharge contains patient demographics, up to 15 International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnoses and procedures, Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRG) codes, total charges, length of stay, and expected payer source from billing or hospital discharge abstract data.

Variables and Data Definitions

The primary variables of interest for monitoring trends were complicated newborn stays, defined as hospital discharge records with an ICD-9-CM diagnosis indicating a complicated birth at delivery or a neonate admission to the hospital within 30 days after the birth (this does not include the birth event). Other variables of interest were expected primary payer, classified as private insurance, Medicaid, other types of insurance (including Medicare) or uninsured (self-pay, no charge); costs of complicated newborn stays; length of stay in the hospital; and most prevalent principal diagnosis. Total hospital charges were converted to costs using a year-specific HCUP Cost-to-Charge Ratio (HCUP, 2006–2009). Costs were adjusted to 2009 dollars using the overall consumer price index (CPI Inflation Calculator, 2013). Hospital length of stay is calculated by subtracting the hospital discharge date from the hospital admission date.

Additional covariates of interest in assessing expected payer for complicated newborn stays were infant’s gender race/ethnicity (Black, Hispanic, White, Other), community-level median household income based on the ZIP Code of the patient, location of residence, and hospital characteristics (ownership, region, teaching status, bed size, urban or rural location).

To further understand the types of complications that newborns experienced at birth or within 30 days of birth in 2009, all-listed ICD-9-CM diagnoses were classified into clinically meaningful categories using a modified version of the Clinical Classification Software (CCS) (HCUP CCS, 2009, December). The principal diagnosis was used, unless this diagnosis was not plausible as a reason for a complicated hospital stay, in which case the first clinically relevant diagnosis code was used. For example, if the principal diagnosis was “other perinatal conditions” the next diagnosis indicating a specific condition was used. See Appendix A for list of clinically meaningful categories through a modified CCS. The majority of stays were classifiable within the first four diagnoses.

Study Sample

The study sample for this analysis was created from HCUP NIS and comprised all complicated newborn stays drawing from approximately 4.2 million newborn discharge records per year, in years 2002–2009. Discharge records with missing information on length of stay (n=26 in 2009), diagnoses (n=172 in 2009), or discharge disposition (n=653 in 2009) were excluded. To reduce misclassification of births, discharge records with ungroupable DRGs, defined as a DRG=999 or missing (n=1,463 in 2009), were excluded; and to reduce double-counting of hospital stays (n=4,512 in 2009), discharge records with an indication of transfers to or from another hospital were also excluded. Less than 0.2 percent of encounters were excluded from each year.

Analysis

National estimates were calculated using HCUP-supplied weights, based on the NIS sampling frame. The unit of analysis is the hospital discharge (i.e., the hospital stay), not an infant. Trends from 2002–2009 were displayed graphically and significance of trend was ascertained through a chi-square test for trend (Snedecor & Cochran, 1989). To determine likely payer source in 2009, three logistic regression models were conducted for each of the three most prevalent diagnoses (preterm birth/low birth weight, respiratory distress, and jaundice). Presence of the diagnosis was the outcome variable, while the main predictor variable in each model was expected payer source (Medicaid, Private, or Uninsured). Odds ratios were adjusted for infant’s gender, race/ethnicity, community-level median household income, location of residence, and hospital characteristics.

Results

Overall Trends for Complicated Births

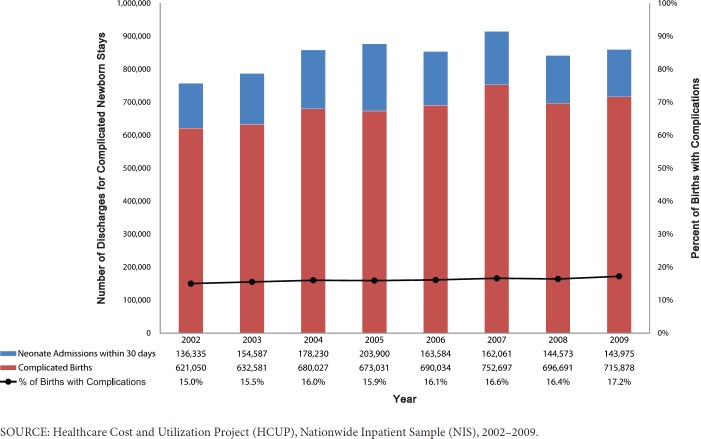

Exhibit 1 shows the number of complicated newborn stays split out by the total number of complicated births and the total number of neonate admissions within 30 days after the birth, and the percent of complicated births across all expected payers from 2002 to 2009, (P = .08 for trend). By 2009, there were 4,154,637 total births, and complicated newborn stays reached 859,853 (21% of all births). Of the complicated newborn stays, 143,975 (17%) were for neonate admissions within 30 days of birth.

Exhibit 1. Total Hospital Discharges for Complicated Newborn Stays from 2002–2009.

Exhibit 2 displays trends by expected payer, showing that the proportion of complicated newborn stays billed to Medicaid increased between 2006 and 2009 (P<.001 for trend), while the proportion of these stays billed to private insurance decreased (P<.001 for trend). By 2009, the trend lines crossed and Medicaid was billed for a higher proportion of complicated newborn stays than private payers. There were far fewer uninsured complicated newborn stays than those billed to Medicaid or private payers and the proportion remained unchanged between 2002 and 2009.

Exhibit 2. Percent of Complicated Newborn Stays by Expected Payer Source from 2002–2009.

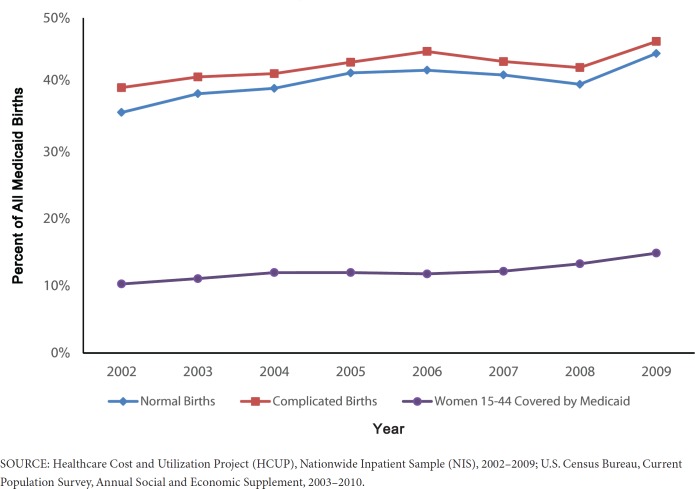

Exhibit 3 shows the proportion of normal (uncomplicated) Medicaid births, the proportion of complicated Medicaid births, and the proportion of women in the U.S. 15–44 years old who are covered by Medicaid. The proportion of normal and complicated births followed a similar projection over time, and there was an increase over time in the proportion of women 15–44 years old who were covered by Medicaid. This indicates that the increase in Medicaid complicated births may have been attributed to an increase in the overall births covered by Medicaid.

Exhibit 3. Maternal Medicaid Coverage and Stays Billed to Medicaid for Births.

Exhibit 4 shows that the average cost per stay for complicated newborn stays increased over this time period from $12,835 in 2002 to $13,232 in 2009 (P < 0.001 for trend). Exhibit 5 displays the average cost per stay by expected payer source illustrating that from 2002 through 2009, the cost for Medicaid is consistently higher than for private payers. In 2009, complicated newborn stays accounted for over $11 billion with Medicaid billed for $6 billion and private billed for $4.4 billion (data not shown).

Exhibit 4. Average Cost1 per Hospital Stay for Complicated Newborn Stays from 2002–2009.

Exhibit 5. Average Cost1 per Admission by Payer Source for Complicated Newborn Stays from 2002–2009.

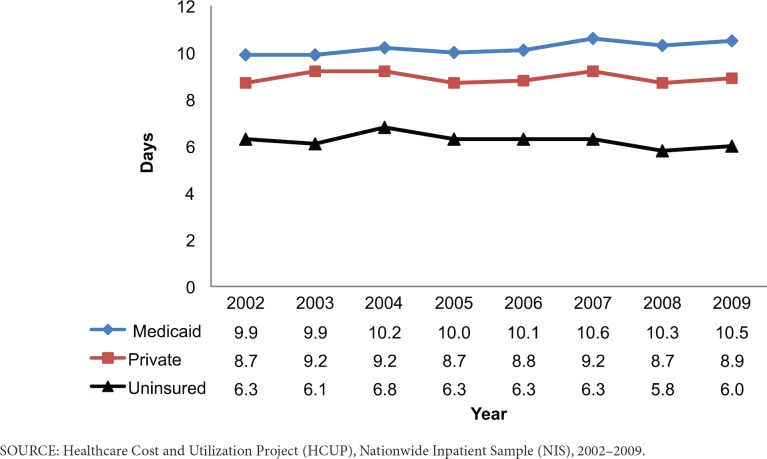

Exhibit 6 shows that the average length of stay was higher for complicated newborn stays billed to Medicaid than private insurance and considerably higher than for those uninsured for all years between 2002 and 2009. The average length of stay across all expected payers did not vary across the years (P = 0.37 for trend) (data not shown).

Exhibit 6. Average Length of Stay for Complicated Newborn Stays by Payer Source from 2002–2009.

Leading Diagnoses for Complicated Newborn Stays in 2009

In 2009, the study sample included 859,853 complicated newborn stays, of which 143,975 (17%) were for admissions within 30 days of birth. Exhibit 7 displays the top ten most prevalent diagnoses in 2009 associated with complicated newborn stays, which accounted for 75% of all of the discharges and 82% of the costs. The top diagnosis was preterm birth/low birth weight (23%), followed by respiratory distress (18%) and jaundice (10%). Preterm birth/low birth weight accounted for 33% of the aggregate costs with a mean length of stay of 14.2 days. Respiratory distress accounted for 28% of the aggregate cost with a similar length of stay of 14.1 days. Taken together, preterm birth/low birth weight and respiratory distress accounted for 41% of the newborns and 61% of the aggregate costs with almost the same mean length of stay of about 14 days. While jaundice ranked third, it accounted for only 3% of the costs and had a mean length of stay of 3.9 days. Although the top three diagnoses were the same for overall discharges for complicated births and admissions within 30 days of birth, the rankings were different. The highest proportion of admissions within 30 days of birth was for jaundice (25%), followed by respiratory distress (14%) and preterm birth/low birth weight (11%;(data not shown).

Exhibit 7. Ranking of Diagnoses for Complicated Newborn Stays Using the Clinical Classification System (CSS), 2009.

| Total Complicated Newborn Stays in 2009 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCS Diagnostic Category: Principal Diagnosis (or next best) | N | % of All Complicated Birth | Rank | Mean Total Cost | Aggregate Cost | % Aggregate Cost | Mean LOS(in days) | |

| Total Discharges for Complicated Newborn Stays | 859,853 | — | — | $13,232 | $11,188,787,072 | — | 9.6 | |

| Preterm (<37 weeks), low birth weight (<2,500 grams) | 197,165 | 22.9% | 1 | $18,788 | $3,630,809,634 | 32.5% | 14.2 | |

| Respiratory Distress and other respiratory distress and other respiratory conditions during the perinatal period | 157,790 | 18.4% | 2 | $20,318 | $3,166,371,489 | 28.3% | 14.1 | |

| Hemolytic jaundice and other congenital conditions. | 89,304 | 10.4% | 3 | $3,967 | $338,732,114 | 3.0% | 3.9 | |

| Polyhydramnios and other problems of the amniotic cavity | 42,913 | 5.0% | 4 | $3,561 | $150,341,223 | 1.3% | 3.7 | |

| Septicemia | 40,068 | 4.7% | 5 | $15,003 | $595,305,073 | 5.3% | 10.5 | |

| Cardiac and Circulatory Congenital Anomalies | 28,435 | 3.3% | 6 | $27,378 | $755,139,353 | 6.7% | 11.9 | |

| Other Congenital Anomalies | 25,095 | 2.9% | 7 | $10,190 | $247,883,874 | 2.2% | 6.2 | |

| Maternal Disorders Affecting the Newborn | 22,617 | 2.6% | 8 | $3,486 | $77,480,876 | 0.7% | 4.3 | |

| Other endocrine disorders | 20,478 | 2.4% | 9 | $6,217 | $124,381,404 | 1.1% | 5.8 | |

| Temperature Regulation | 20,103 | 2.3% | 10 | $3,460 | $68,317,541 | 0.6% | 3.5 | |

| Top 10 | 643,968 | 74.9% | — | $11,237 | $9,154,762,581 | 81.8% | 7.8 | |

SOURCE: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), 2002–2009.

A logistic regression model was used to determine the likely payer source for hospital stays related to one of the top three diagnoses, after adjusting for patient and hospital characteristics. Hospital stays for preterm birth/low birth weight were more likely to be billed to Medicaid compared to private insurance, (OR = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.27, 1.70), as were hospitals stays for respiratory distress (OR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.08, 1.57). However, hospital stays for jaundice were less likely to be billed to Medicaid compared to private insurance (OR =0.86, 95% CI: 0.77, 0.96), see Exhibit 8.

Exhibit 8. Expected Payer Source of Hospital Stays for Three Prevalent Diagnoses, Adjusting for Patient and Hospital Characteristics,1 2009.

| Model 1: Preterm, Low Birth Weight | Model 2: Respiratory Distress and Other Respiratory Conditions | Model 3: Hemolytic Jaundice | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | ||

| Expected Payer (ref: Private) | ||||||||

| Medicaid | 1.47 | (1.27,1.70) | 1.31 | (1.08,1.57) | 0.86 | (0.77,0.96) | ||

| Other | 1.84 | (1.17,2.91) | 1.78 | (1.26,2.51) | 0.80 | (0.58,1.11) | ||

| Uninsured | 0.91 | (0.62,1.34) | 1.02 | (0.68,1.54) | 1.15 | (0.93,1.42) | ||

| Gender (ref: Male) | ||||||||

| Female | 1.03 | (0.97,1.10) | 0.88 | (0.82,0.94) | 0.91 | (0.86,0.96) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity (ref: White) | ||||||||

| Black | 0.87 | (0.65,1.15) | 0.49 | (0.37,0.65) | 0.42 | (0.33,0.53) | ||

| Hispanic | 0.95 | (0.70,1.28) | 0.86 | (0.67,1.09) | 1.26 | (1.06,1.48) | ||

| Other | 1.00 | (0.74,1.33) | 0.99 | (0.67,1.46) | 1.61 | (1.39,1.87) | ||

| Missing | 3.14 | (1.66,5.95) | 1.13 | (0.69,1.85) | 0.94 | (0.73,1.21) | ||

| Community-Level Median Household Income (ref: $67,000+) | ||||||||

| < $40,999 | 1.22 | (0.90,1.65) | 1.72 | (1.21,2.44) | 0.80 | (0.63,1.03) | ||

| $41,000–$50,999 | 1.08 | (0.79,1.46) | 1.39 | (1.01,1.92) | 0.82 | (0.66,1.01) | ||

| $51,000–$66,999 | 0.98 | (0.76,1.25) | 1.25 | (0.95,1.64) | 0.81 | (0.66,0.99) | ||

| Patient location (ref: large metropolitan) | ||||||||

| Small metropolitan | 1.58 | (0.85,2.93) | 1.76 | (1.11,2.79) | 1.09 | (0.85,1.39) | ||

| Micropolitan | 3.16 | (2.11,4.75) | 5.15 | (3.38,7.85) | 0.88 | (0.68,1.13) | ||

| Non-micropolitan, non-metropolitan | 2.27 | (1.23,4.18) | 5.13 | (3.35,7.86) | 0.86 | (0.65,1.14) | ||

NOTE:

Models adjusted for the following hospital characteristics: ownership, region, teaching status, bedsize and urban/rural location.

Discussion

This is the first study, to our knowledge, that examined recent trends in complicated newborn hospital stays and expected payer source. Over the eight-year period examined, Medicaid was billed for an increasing number and proportion of complicated newborn hospital stays, and the cost of those stays rose over time. This information has important implications for both the Medicaid program and the establishment of health insurance exchanges under the ACA.

Private payers were billed for more complicated newborn stays than Medicaid from 2002 until 2006, when the trend lines converged for the following three years (2007–2009). In 2009, Medicaid was billed for slightly more complicated newborn stays than private payers. This is consistent with another study showing that Medicaid was the most likely payer for preterm birth/low birth weight complications in 2007 (Russell et al., 2007). The findings are also consistent with other Medicaid trends showing dramatic growth in Medicaid enrollment since the recession of 2007, as millions of individuals lost jobs and employer-sponsored private coverage (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2011, February), and the the proportion of births paid for by Medicaid grew (Stranges et al., 2011, January). Both complicated and normal births paid by Medicaid increased over time, indicating Medicaid in general has been paying for more overall births, likely due to an increase in Medicaid enrollment of women of reproductive age (15–44 years). The trend indicates that Medicaid may assume responsibility for a growing number of both normal and complicated newborn stays in future years.

At the same time that Medicaid’s share of births and complicated newborn stays was rising, the cost of those stays was growing as well. From 2002 to 2009, the average cost per admission of a complicated newborn stay rose from $10,763 to $13,232, an increase of 23% after adjusting for inflation. By 2009, aggregate costs for complicated newborn stays totaled over $11 billion, of which Medicaid was bearing $6 billion of those costs. Overall, the average length of stay and the cost per admission for the uninsured was lower than for those covered by Medicaid or private insurance. This is likely because those without insurance may use fewer health care services within a given admission due to the high out-of-pocket expenses. Because the eligibility thresholds are generous for pregnant women, most low-income pregnant women would be on Medicaid or may be enrolled in Medicaid while in the hospital.

The rising number of complicated newborn stays, largely comprised of infants with preterm birth/low birth weight and respiratory distress, highlights a critical need to improve prenatal and maternal health. This is necessary both to improve birth outcomes and to control the rapidly rising costs associated with complicated newborn stays. Efforts to prevent preterm birth and low birth weight would likely have implications for reducing admissions for respiratory distress. As a result, the prevention of preterm birth and low birth weight presents a major opportunity to secure a substantial return on investment by improving maternal and infant health and reducing costs throughout the health care system, but particularly for the Medicaid program. Similarly, these findings have important implications for the policies and programs that serve children with special needs due to their birth related complications.

Over the past five years, a number of programs have been created to improve birth outcomes and reduce infant mortality, both in the aggregate and targeted at specific risk factors. Many of these efforts are described below.

Among the earliest of these efforts was the March of Dimes Healthy Babies Are Worth the Wait campaign focusing on the elimination of elective deliveries before 39 weeks gestation, which are associated with poorer birth outcomes (Clark et al, 2009).

In 2011, the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) issued a national challenge to reduce preterm birth by 8 percent by 2014, which was accepted by all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico.

In 2012, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) launched the Strong Start initiative, a two-pronged effort to reduce early elective deliveries by distributing information cobranded by the March of Dimes and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and to improve birth outcomes by funding over $40 million in grants to test promising practices in prenatal care.

In 2012, HRSA established a Collaborative Improvement and Innovation Network (COIIN) for state officials to pursue specific strategies to reduce infant mortality, including many efforts consistent with the goals of the ASTHO challenge.

The National Governors Association similarly funded four states through a Learning Network on Improving Birth Outcomes to engage in concerted efforts to meet the ASTHO challenge.

The Medicaid medical directors are also engaged in a separate learning network effort on early elective deliveries to link datasets in order to relate a mother’s health and health care outcomes, pre-birth to birth, to subsequent health outcomes and costs for the infant.

This strong interest in improving perinatal health and birth outcomes is driven by a clear recognition that the costs of complicated births have significant implications for public health spending in both public and private programs. By 2011, Medicaid had covered 45 percent of all births nationwide and over 60 percent of births in six states (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2012, January). With the full implementation of the ACA, however, the number of births that are publicly subsidized will increase dramatically, either through Medicaid or through public subsidies to women in the health insurance exchanges.

There is also some evidence to suggest, however, that the universal availability of coverage will lead to more access to a regular source of care and preventive services for non-pregnant, low income women of childbearing age, most of whom are currently ineligible for Medicaid (Pellegrini & Garro, 2013, February 22). The ACA requires group health plans to provide a range of preventive services, including many services that fall under preconception and interconception care (ACA, 2010) that can play a key role in promoting wellness for mothers and risk reduction strategies for women at high risk for poor birth outcomes (Lu, 2007; Lu et al., 2006). It is possible that such care will lead to improved preconception and interconception health, resulting in women being healthier when they become pregnant. Reductions in risk factors (such as tobacco use) and more consistent access to preventive strategies (such as antenatal steroids for women with a prior preterm birth) could lead to a reduction in complicated births, with associated savings for all payers.

This study made important new contributions, but it also had limitations. First, maternal-child linkages are not possible with the HCUP NIS, and we are missing key maternal factors that may influence complicated births, such as maternal age, race/ethnicity, education, smoking status, pregnancy and birth history, and type of delivery among others. Second, important clinical details to determine the severity of conditions are lacking in administrative billing data. Third, the infant’s race/ethnicity was missing in about 25% of the cases. However, this variable was only to determine relationships in this analysis and not for point estimates. Fourth, because the analysis relied on billing or hospital discharge abstract data, only expected payer source, and not actual insurance coverage, could be identified. Finally, discharges billed to the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) may be not be consistently classified as a specific payer group: discharges billed to CHIP may be classified as Medicaid, private, or other insurance, depending on the structure of the state CHIP program.

Despite limitations, the results of this study shed light on important trends in complicated newborn outcomes and costs, especially for Medicaid. Policies to prevent high-cost birth complications have the potential for both improving birth outcomes and reducing costs. As a major payer of birth hospitalizations, Medicaid has the potential to drive quality improvement efforts that aim to improve birth outcomes and affect deliveries that are funded through private mechanisms as well.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the HCUP Partner organizations that participated in the HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) (www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/hcupdatapartners.jsp).

Appendix A. Classification Identification of Clinically Meaningful Categories Through A Modified CCS.

| ICD-9-CM Diagnosis Code | Original CCS | Modified CCS |

|---|---|---|

| 040.41, 771.83 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 3: Bacterial infection |

| 771.0 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 7: Viral infection |

| 771.1–771.8, 771.89 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 8: Other infections |

| 775.3 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 48: Thyroid disorders |

| 775.1 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 49: Diabetes mellitus without complications |

| 772.5, 775.6 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 51: Other endocrine disorders |

| 779.34, 783.0 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 52: Nutritional deficiencies |

| 775.5 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 55: Fluid and electrolyte disorders |

| 775.4, 775.7–775.9, 775.81,775.89, 766.0, 766.1, 783.6 | 224: Other perinatal conditions 259: Residual codes |

58: Other nutritional, endocrine, and metabolic disorders |

| 776.5, 776.6, 772.0 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 59: Deficiency and other anemia |

| 772.8, 772.9, 776.0-776.4, 776.7–776.9 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 62: Coagulation and hemorrhagic disorders |

| 790.91–790.99, 790.6, 790.9 | 259: Residual codes | 64: Other hematologic conditions |

| 779.2 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 82: Paralysis |

| 779.0 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 83: Epilepsy; convulsions |

| 779.1 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 84: Headache, including migraine |

| 775.2 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 95: Other nervous system disorders |

| 779.81, 779.82 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 106: Cardiac dysrhytmias |

| 779.85 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 107: Cardiac arrest and ventricular fibrillation |

| 772.2 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 109: Acute cerebrovascular disease |

| 772.1, 772.10–772.14 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 117: Other circulatory disease |

| 777.1, 777.2 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 145: Intestinal obstruction with hernia |

| 772.4 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 153: Gastrointestinal hemorrhage |

| 777.4–777.6, 777.50–777.53, 777.8, 777.9, 780.94 | 224: Other perinatal conditions 259: Residual codes |

155: Other gastrointestinal disorders |

| 771.82 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 159: Urinary tract infection |

| 761.4 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 180: Ectopic pregnancy |

| 762.0–762.3 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 182: Hemorrhage during pregnancy; abruption placenta; placenta previa |

| 761.7, 763.0–763.1 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 187: Malposition, malpresentation |

| 761.3, 762.7–762.9, 779.89 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 191: Polyhydramnios and other problems with amniotic fluid |

| 762.4–762.6, 779.83, 772.3 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 192: Umbilical cord complications |

| 763.2 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 194: Forceps delivery |

| 761.0,761.5,761.6,761.8,761.9, 763.3–763.9, 763.81–763.89 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 195: Other complications of birth; puerperium affecting management ofthe mother |

| 772.6, 782.9 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 200: Other skin disorders |

| 770.81–770.84, 770.89, 770.0–770.8, 770.87, 770.9 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 221: Respiratory distress syndrome |

| 779.82, 796.5, 796.6, 776.21, 776.22, 770.10–770.18, 770.85, 770.86, 766.2 | 224: Other perinatal conditions 259: Residual codes |

224: Other perinatal conditions |

| 777.3, 779.32, 779.33, 779.3, 779.31 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 250: Nausea and vomiting |

| 799.23 | 259: Residual codes | 656: Impulse control disorders, NEC |

| 799.24, 799.25, 799.29 | 259: Residual codes | 657: Mood disorders |

| 760.0–760.9, 760.61–760.64, 760.70–760.79, 775.0 | 224: Other perinatal conditions | 950: Maternal disorders affecting newborn |

| 307.40–307.49, 327.00, 327.01, 327.51, 327.59, 327.8, 327.09–327.29, 327.40–327.49, 780.02, 780.50–780.59, 780.1 | 259: Residual codes 224: Other perinatal conditions |

951: Sleep disorders |

| 790.91, 780.92, 780.95, 780.7, 799.2, 799.21, 799.22 | 224: Other perinatal conditions 252: Malaise and faigue 259: Residual codes |

952: Excessive fussiness |

| 778.0–778.9, 780.64, 780.65, 780.99, 782.8 | 224: Other perinatal conditions 259: Residual codes |

953: Temperature regulation |

| 779.9, 798.0–798.2, 789.9, 799.3 | 224: Other perinatal conditions 259: Residual codes |

954: Sudden infant death and debility |

| 780.9, 780.93, 780.96, 780.97, 781.5, 781.6, 782.3, 782.61, 782.62, 784.2, 790.1, 792.9, 793.2, 793.9, 793.99, 794.9, 795.4, 795.81, 795.82, 795.89, 796.3, 796.4, 796.5, 796.9, 799.89, 799.9 | 259: Residual codes | 955: Other signs and symptoms |

SOURCE: ICD-9-CM Diagnoses and Clinical Classification Software (CCS).

References

- ACA. Group Health Plans and Health Insurance Issuers Relating to Coverage of Preventive Services. Department of Health and Human Services 45 CFR Part 147. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 2010.

- Behrman RE, Butler AS. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, The National Academies Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark SL, Miller DD, Belfort MA, Dildy GA, Frye DK, Meyers JA. Neonatal and Maternal Outcomes Associated with Elective Term Delivery. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;200(2):156.e1–156.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CMS. Strong Start for Mothers and Newborns Initiative: General Information. 2013 Retrieved from http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/strong-start/

- Inflation Calculator, C. P. I. Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm.

- Elixhauser A, Wier LM. Complicating Conditions of Pregnancy and Childbirth, 2008 (HCUP Statistical Brief #113) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. May, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman B, Berdahl T, Simpson LA, McCormick MC, Owens PL, Andrews R, Romano PS. Annual Report on Health Care for Children and Youth in the United States: Focus on Trends in Hospital Use and Quality. Academy of Pediatrics. 2011;11(4):263–279. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HCUP. Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2002–2009. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HCUP. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Cost-to-Charge Ratio Files (CCR) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2006–2009. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/state/costtocharge.jsp. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HCUP CCS. [Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Clinical Classification Software (CSS)] Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2009. Dec, Retrieved from http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- HRSA. Collaborative Improvement & Innovation Network to Reduce Infant Mortality. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration; 2013. Retrieved from http://mchb.hrsa.gov/infantmortality/coiin/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- IOM. U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Washington, DC: National Research Council and Institute of Medicine; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid Facts. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2012. Jun, Medicaid Enrollment: June 2011 Data Snapshot. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid’s Role for Women Across the Lifespan: Current Issues and the Impact of the Affordable Care Act. The Kaiser Family Foundation; 2012. Jan, [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid Facts. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2011. Feb, Medicaid spending growth and the great recession: 2007–2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kenney GM, Lynch V, Cook A, Phong S. Who and Where Are the Children Yet to Enroll in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program? [pii] Health Affairs (Project Hope) 2010;29(10):1920–1929. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu MC. Recommendations for Preconception Care. American Family Physician. 2007;76(3):397–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu MC, Kotelchuck M, Culhane JF, Hobel CJ, Klerman LV, Thorp JM., Jr Preconception Care Between Pregnancies: The Content of Internatal Care. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2006;10(1) Suppl:107–122. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0118-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ. Births: Final Data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2012;61(1):1–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick MC, Litt JS, Smith VC, Zupancic JA. Prematurity: An Overview and Public Health Implications. Annual Review of Public Health. 2011;32:367–379. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090810-182459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini C, Garro N. Medicaid Expansion: Benefits for Women of Childbearing Age and Their Children. Health Affairs Blog. 2013 Feb 22; Retrieved from http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2013/02/22/medicaid-expansion-benefits-for-women-of-childbearing-age-and-their-children/

- Russell RB, Green NS, Steiner CA, Miekle S, Howse JL, Poschman K, … Petrini JR. Cost of Hospitalization for Preterm and Low Birth Weight Infants in the United States. Pediatrics. 2007;120(1) doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical Methods. 8. Iowa State University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Stranges E, Ryan K, Elixhauser A. Medicaid hospitalizations, 2008 (HCUP Statistical Brief #104) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. Jan, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Survey. Annual Social Economic Supplement 2003–2010. https://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/publications/pubs-cps.html.

- Wier LM, Andrews RM. The National Hospital Bill: The Most Expensive Conditions by Payer, 2008 (HCUP Brief #107) Rockille, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. Mar, [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise PH. The Transformation of Child Health in the United States. Health Affairs. 2004;23(5):9–25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.5.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]