Abstract

Sulfur mustard (bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide, SM) is a highly reactive bifunctional alkylating agent inducing edema, inflammation, and the formation of fluid-filled blisters in the skin. Medical countermeasures against SM-induced cutaneous injury have yet to be established. In the present studies, we tested a novel, bifunctional anti-inflammatory prodrug (NDH 4338) designed to target cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2), an enzyme that generates inflammatory eicosanoids, and acetylcholinesterase, an enzyme mediating activation of cholinergic inflammatory pathways in a model of SM-induced skin injury. Adult SKH-1 hairless male mice were exposed to SM using a dorsal skin vapor cup model. NDH 4338 was applied topically to the skin 24, 48, and 72 hr post-SM exposure. After 96 hr, SM was found to induce skin injury characterized by edema, epidermal hyperplasia, loss of the differentiation marker, keratin 10 (K10), upregulation of the skin wound marker keratin 6 (K6), disruption of the basement membrane anchoring protein laminin 322, and increased expression of epidermal COX2. NDH 4338 post-treatment reduced SM-induced dermal edema and enhanced skin re-epithelialization. This was associated with a reduction in COX2 expression, increased K10 expression in the suprabasal epidermis, and reduced expression of K6. NDH 4338 also restored basement membrane integrity, as evidenced by continuous expression of laminin 332 at the dermalepidermal junction. Taken together, these data indicate that a bifunctional anti-inflammatory prodrug stimulates repair of SM induced skin injury and may be useful as a medical countermeasure.

Keywords: skin, sulfur mustard, Non-steroid bifunctional anti-inflammatory and anticholinergic agent, wound repair

INTRODUCTION

Sulfur mustard (bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide, SM) is a highly toxic vesicant that can rapidly penetrate human skin and cause extensive chemical burns (Vogt et al., 1984; Shakarjian et al., 2010). As a reactive bifunctional alkylating agent, SM can form mono-adducts and cross-links with many nucleophilic components in cells including proteins, lipids, and DNA. This can result in prolonged inflammation and delayed wound repair (Papirmeister et al., 1985; Rowell et al., 2009). SM can also alkylate basement membrane components in the skin which disrupts the dermal-epidermal junction (DEJ), causing detachment of basal keratinocytes from the basement membrane (Monteiro-Riviere and Inman, 1997; Petrali and Oglesby-Megee, 1997; Monteiro-Riviere et al., 1999). Both apoptosis and necrosis of keratinocytes are thought to contribute to SM-induced skin vesication (Petrali and Oglesby-Megee, 1997; Rosenthal et al., 1998; Ruff and Dillman, 2007). Inflammatory cells and mediators are known to play a key role in the pathogenic response to SM (Casillas et al., 2000; Sabourin et al., 2000; Kehe et al., 2009). Thus, the development of anti-inflammatory drugs with multiple mechanisms of action which target inflammatory signaling pathways represents a novel strategy for limiting SM-induced injury and promoting wound repair.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most commonly used agents to suppress inflammation. One important NSAID target is cyclooxygenase (COX), a family of enzymes which catalyze the synthesis of eicosanoids (Katori and Majima, 2000). Previous studies have shown that COX2 knockout mice are protected from SM-induced acute skin injury and that COX2 inhibitors suppress SM toxicity, demonstrating the importance of this enzyme in SM-induced skin damage (Babin et al., 2000; Casillas et al., 2000; Wormser et al., 2004).Indomethacin was chosen because it had, in a pre-treatment based study, been reported to display modest edema-suppression in rodents exposed to sulfur mustard (Casillas et al., 2000). Also, in an earlier publication from our laboratory using a post-treatment assay, Indomethacin ranked better than Diclofenac, Ibuprofen, and S-Naproxen when incorporated into a prodrug, dually targeting inflammation and cholinergic dysfunction (Young et al., 2012).

Evidence also suggests that pro-inflammatory molecules generated following injury in the skin are regulated via cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathways (Kurzen et al., 2007). In this regard, cholinergic antagonists including acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEI) have been reported to be effective in suppressing inflammation (Tracey, 2007; Reale et al., 2009). The effects of AChEI on skin inflammation and injury are unknown and were investigated in the present studies. We selected 3,3-dimethyl-1-butanol because it has been reported to be a weak (Ki = 7.3 mM), reversible, noncompetitive inhibitor of AChE and can be incorporated into esters as a bioisostere for choline and activate the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (Cohen et al., 1985). We have previously shown that although the 3,3-dimethylbutyl moiety does confer anticholinergic activity, the IC50's (as AChEIs) varied from 0.51 micromolar to >2000 micromolar depending on the particular NSAID to which the 3,3-dimethylbutyl piece is conjugated (Young et al., 2010).

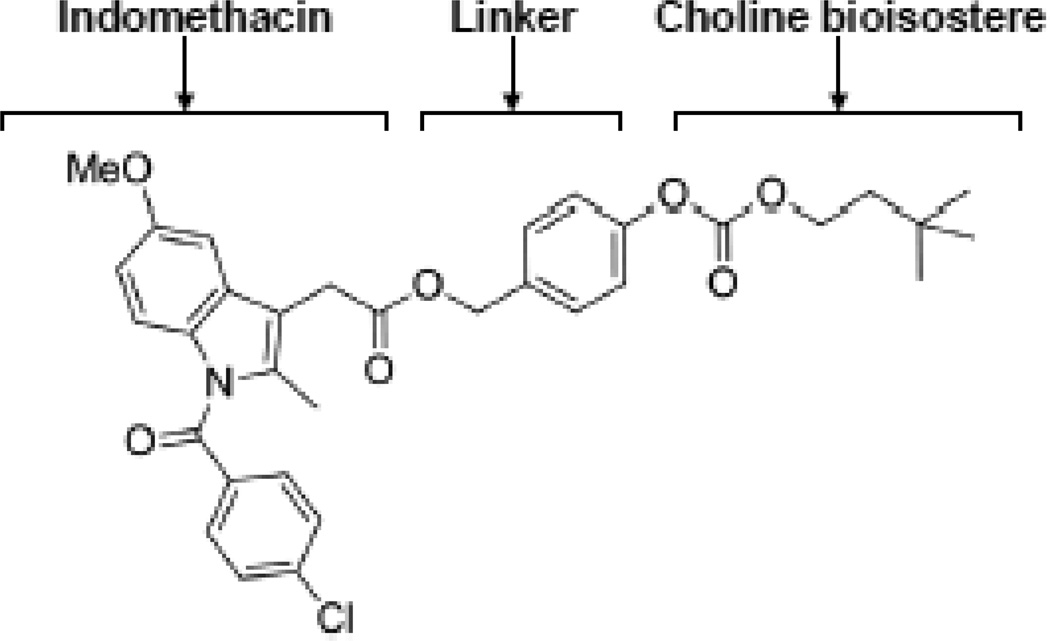

In these experiments, we utilized a prodrug consisting of an NSAID (indomethacin) and an AChEI (3, 3-dimethyl-1-butanol) (Young et al., 2010). Indomethacin is tethered by ester and carbonate linkages to 3, 3-dimethyl-1-butanol, an anti-cholinergic choline bioisostere (Figure 1). This compound, referred to as NDH 4338, possesses anti-inflammatory activity and is an AChEI inhibitor (Young et al., 2010; Young et al., 2012). In previous studies using the mouse ear vesicant model we demonstrated that NDH 4338 mitigated skin inflammation induced by the half mustard vesicant, 2-chloroetheyl ethyl sulfide (CEES) and was shown to reduce edema by over 90%, suggesting its use as a countermeasure against SM-induced skin injury (Young et al., 2010; Young et al., 2012). In the present studies we evaluated the efficacy of NDH 4338 against SM-induced skin injury using the hairless mouse skin model.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of the bifunctional anticholinergic NSAID compound NDH 4338. The drug combines two anti-inflammatory moieties (indomethacin and a choline bioisostere, 3,3-dimethyl-1-butanol), attached via an aromatic ester-carbonate linkage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and treatments

Male SKH-1 hairless mice (Charles River Laboratories, Portage, MI), 5–8 weeks of age (n = 6 mice per group), were exposed to SM or sham control for 6 min using a vapor cup dorsal skin model as previously described (Joseph et al., 2011). The SKH1 mice, used in the experiment, do have a normal coat of hair with normal appendages up to 10 days of age; after the first hair cycle, mature hair is lacking, although the appendages remain (Benavides et al., 2009). The dorsal skin of the mice was treated with vehicle (dimethyl isosorbide (DMI)/ethyl oleate (Croda, Inc., Edison, NJ)) or vehicle formulated with 1% NDH 4338 at 24, 48 and 72 hr post SM exposure. Mice were sacrificed 96 hr after SM, punch biopsies of exposed areas collected, and divided into 2 sections. Skin tissue was either embedded in Tissue Tek optimum cutting temperature medium (OCT, Sakura Finetek USA, Torrance, CA) and flash frozen for histology, or directly flash frozen for protein analyses. SM exposures were performed on anesthetized mice and were carried out at Battelle Biomedical Research Center, West Jefferson, OH, USA. All animal protocols were approved by the Battelle Memorial Institute animal care and use committee. SM was obtained from Edgewood Chemical Biological Center and was chemically analyzed to be 99% pure. NDH 4338, was synthesized as previously reported (Young et al., 2010).

Histology

Frozen sections (10 µm) were fixed in Pen-Fix fixative (Thermo Scientific, PA), and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Skin sections from three mice were evaluated for edema, necrosis and inflammation using an Olympus VS120 Virtual Scanning Microscopy System. To measure skin thickness, ten random sites from each skin section within the wounded area were assessed. The distance from the stratum corneum to the dermal-epidermal junction (DEJ) was measured as the epidermal thickness; and the distance from the DEJ to the striated muscle was measured as the dermal thickness. The mean was calculated and analyzed for significance at p<0.05 using the unpaired Student’s t test.

Western blotting

Frozen skin biopsies were pulverized using a GenoGrinder as previously reported (Chang et al., 2009). Tissue samples were lysed with RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 1% Na-deoxycholate and 0.1% SDS) and protein concentration determined using the BCA Protein Assay Reagent (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL). Pooled tissue lysates were analyzed on 7.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels and then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Life Sciences Group, Hercules, CA). The membranes were incubated with rabbit anti-COX2 polyclonal antibody (1:1,000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) overnight at 4oC, or rabbit anti-GAPDH polyclonal antibody (1:20,000, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by goat antirabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase antibody (1:6,000–1:20,000, BioRad, Hercules, CA). Proteins were detected by chemiluminescence using the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescence Substrate System (Pierce Chemical). GAPDH was used to ensure equal protein loading on the gels.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

Frozen sections (10 µm) were fixed in −20°C methanol for 5 min, washed in PBS, and incubated with normal donkey serum (NDS) or CASBLOCK (Invitrogen, San Francisco, CA) for 1 h at room temperature to block nonspecific binding. Rabbit anti-COX2 (1:200, Abcam), rabbit anti-matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) (1:1,000, Abcam), rabbit anti-laminin 332 (1:100, Abcam), rabbit anti-keratin 6 (K6) 1:1,000, Abcam), rabbit anti-keratin 10 (K10, 1:1,000, Covance, Princeton, NJ), rat anti-Ki67 (1:50, DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) antibodies or IgG controls, diluted in PBS containing /0.05% Tween-20 and 1.5% NDS, were incubated overnight at 4oC. Sections were then incubated for 1 h with either donkey anti-rabbit Dylight 549 (1:400, Jackson Immuno Inc., West Grove, PA) or donkey anti-rat Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1000, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) secondary antibodies. Tissue sections were then mounted in ProLong Gold with DAPI anti-fade reagent (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), coverslips applied and sections cured overnight. Sections were analyzed using a Leica TCS SP5 Confocal Microscope or a Zeiss 510 LSM Confocal Microscope. For immunofluorescence microscopic analysis, the parameters of expression pattern and staining intensity used to classify the reactions were scored as follows: 1 = no staining, 2 = light staining, 3 = moderate staining, 4 = intense staining. The mean of the scored data was calculated and analyzed for significance at p≤0.05 using the unpaired Student’s t test.

RESULTS

Histopathology of mouse skin following exposure to SM

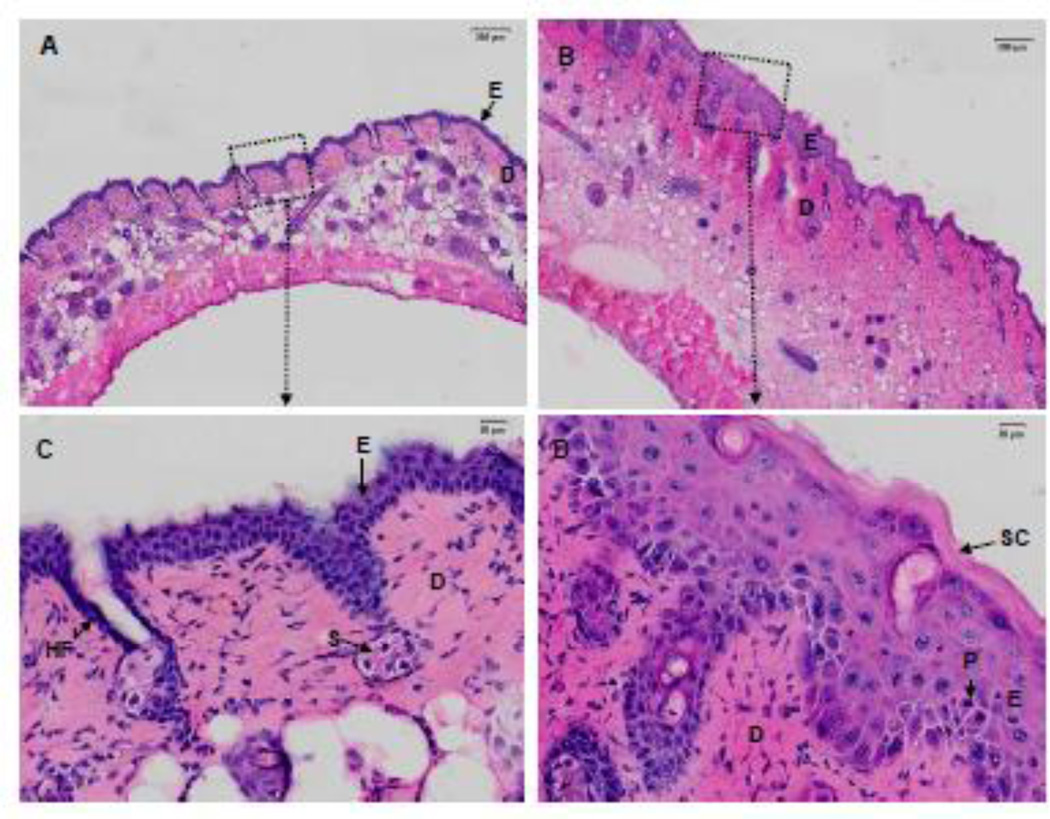

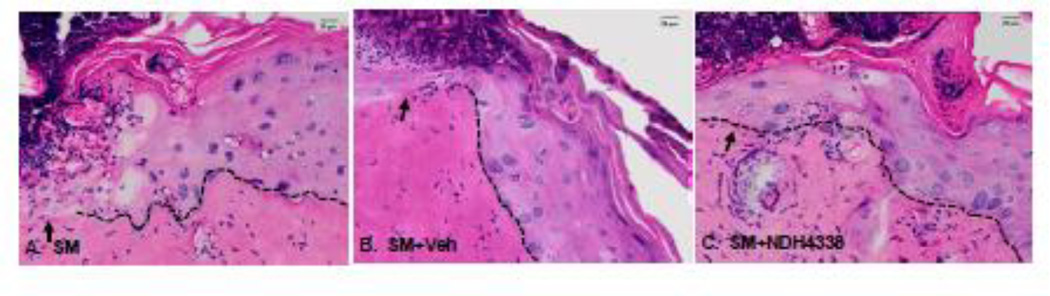

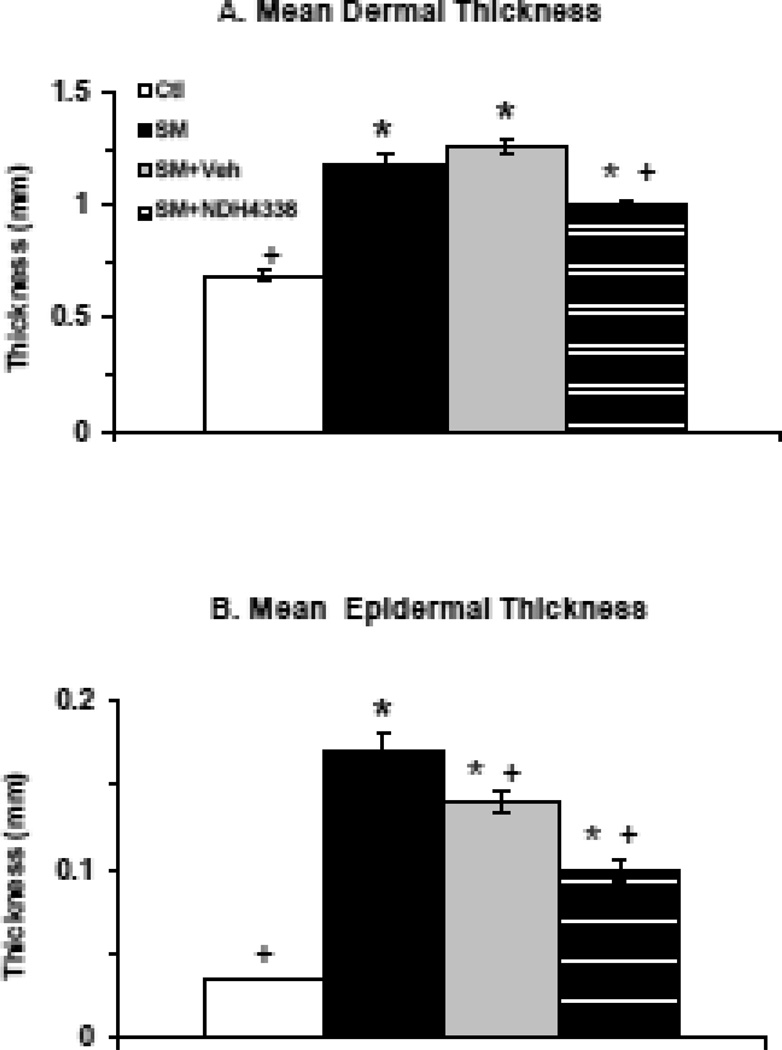

In initial studies we analyzed the effects of SM on skin histology. In control skin, the epidermis was about 3–4 layers thick, with a thin stratum corneum and a continuous sheet of cuboidal basal keratinocytes at the DEJ. The dermis was well organized with fibroblasts scattered throughout the tissue, sitting on a robust hypodermis and an intact muscular layer (Figures 2A, 2C). SM exposure resulted in marked histological changes in the skin. Epidermal hyperplasia with keratinocytes containing pseudoinclusions or pyknotic nuclei were observed (Figures 2B. 2D). In the dermis, edema was apparent, as well as hyperplastic epidermal appendages, inflammatory cells and hemorrhagic red blood cells. The stratum corneum was thickened with evidence of parakeratosis. Four days following SM-exposure, injury beneath the wound was apparent including loss of epithelium and increased numbers of inflammatory cells in the dermis (Figures 3A, 3B). Additionally, keratinocytes beneath the wound appeared disorganized. NDH 4338 treatment stimulated keratinocyte migration and nuclei were aligned in the direction of keratinocyte migration (Figure 3C). Following SM exposure, there was a 1.7-fold increase in dermal thickness and a 3.5-fold increase in epidermal thickness (Figure 4). NDH 4338 treatment decreased dermal and epidermal thickening by approximately one third. NDH 4338 also reduced SM-induced edema and epidermal hyperplasia (Figure 4). Vehicle alone also reduced epidermal thickness by approximately 10%.

Figure 2.

Structural changes in hairless mouse skin following exposure to SM. Histologic sections, prepared 4 days after exposure to air (Ctl) (panels A and C) or SM exposure (panels B and D), were stained with H&E. Panels A and B, scale bar = 200 µm; panels C and D, scale bar = 20 µm. Panels C and D are enlargements of the black dotted squares shown in panels A and B, respectively. dermis (D), epidermis (E), hair follicle (HF), pyknotic nuclei (P),sebaceous glands (S), stratum corneum (SC).

Figure 3.

Effects of NDH 4338 on SM-induced skin injury. Histological sections prepared 4 days after exposure to SM, SM plus vehicle, or SM plus NDH 4338, were stained with H&E. The dotted line denotes the dermal/epidermal junction. The arrow designates the leading edge of the migrating keratinocytes. Scale bar = 20 µm.

Figure 4.

Effects of SM exposure on skin thickness. Skin section, prepared 4 days after exposure to air (Ctl) or SM, were analyzed for dermal (panel A) and epidermal (panel B) thickness. Ctl (open bars), SM (black bars), SM plus vehicle (Veh)(gray bars), SM plus NDH 4338 (striped bars). Data are presented as the mean ± SE (n = 20), *p<0.001, compared to control tissues; +p<0.001, compared to SM exposed tissues.

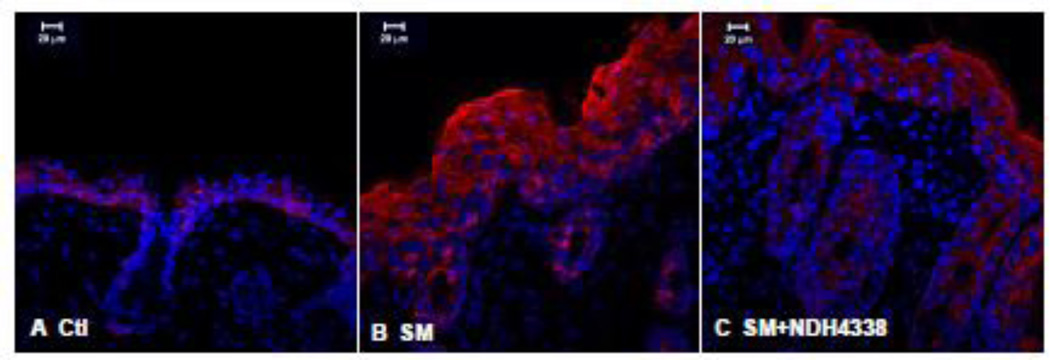

Effects of NDH 4338 on COX2 and MMP9 expression

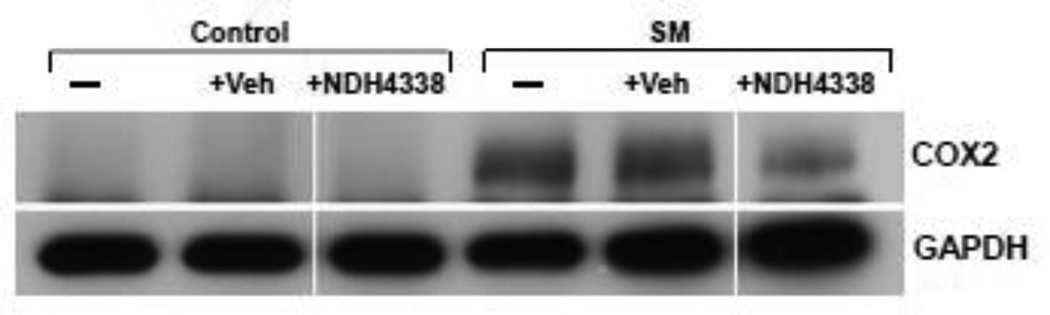

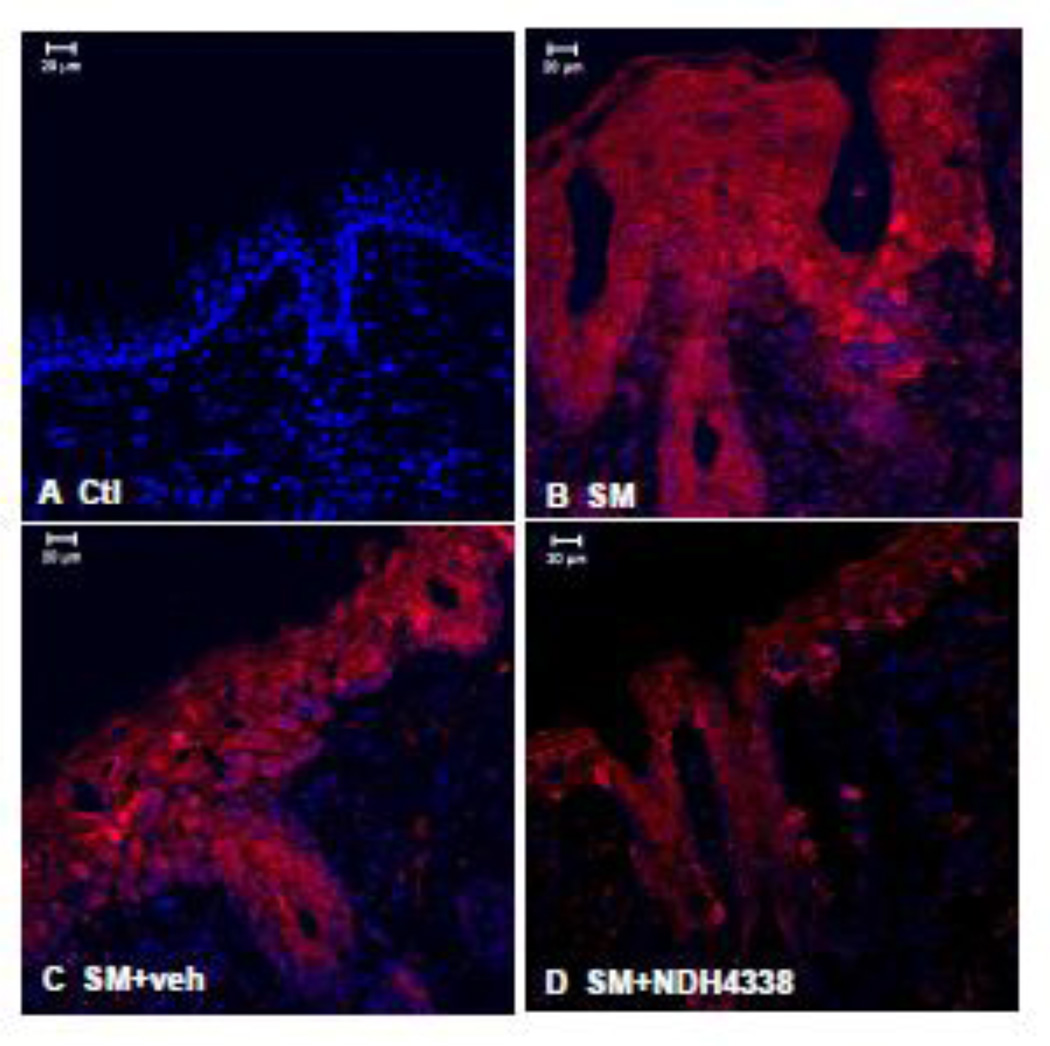

COX2 is the rate limiting enzyme in prostaglandin biosynthesis and a marker of skin inflammation (Lee et al., 2003). COX2 was not detected in control skin or control skin treated with either vehicle or NDH 4338 (Figure 5). SM was found to upregulate COX2 expression. NDH 4338 down regulated SM-induced COX2 expression (Figure 5). These data are consistent with immunohistochemical findings that COX2 was upregulated in epidermis and hair follicles of SM treated mice (Figure 6). NDH 4338 reduced SM-induced COX2 expression throughout the epidermis and dermal appendages. The immunofluorescence mean staining intensity and distribution pattern of COX2 expression in mouse skin also supported the western blot and immunofluorescent data, which showed a significant difference of COX2 expression in skin samples of control (1.3), SM exposed (3.7), and SM exposed plus NDH4338 treatment (2.3) based on 1 as no intensity and 4 as intense staining, as indicated in Table 1.

Figure 5.

Effects of NDH 4338 on SM-induced alterations in COX2 expression in mouse skin. Pooled samples from each group were analyzed by Western blotting using a COX2 antibody. Lane 1, untreated control; lane 2, vehicle alone; lane 3, NDH 4338 alone; lane 4, SM; lane 5, SM plus vehicle; lane 6, SM plus NDH 4338. GAPDH expression was used to ensure equal loading of proteins on the gels.

Figure 6.

Effects of NDH 4338 on SM-induced COX2 expression in mouse skin. COX2 was visualized by confocal microscopy using a secondary antibody conjugated to Dylight 549 (red). Control mouse skin (panel A), SM (panel B), SM plus vehicle control (panel C), and SM plus NDH 4338 (panel D). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (shown in blue), scale bar = 20 µm.

Table 1.

Immunofluorescence mean staining parameters in mouse skin.

| Treatment | COX2 | K10 | K6 | Laminin332 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n=8) | 1.3 ± 0.3+ | 3.7 ± 0.3+ | 2.0 ± 0.0+ | 2.0 ± 0.0+ |

| SM (n=10) | 3.7 ± 0.2* | 2.8 ± 0.2* | 3.9 ± 0.1* | 3.2 ± 0.2* |

| SM+NDH4338 (n=10) | 2.3 ± 0.2+ | 3.8 ± 0.2+ | 2.6 ± 0.2*+ | 2.3 ± 0.1+ |

Staining intensity: 1 = no staining, 2 = light staining, 3 = moderate staining, 4 = intense staining. Data are presented as the mean ± SE (n = 8–10),

p≤0.05, compared to control tissues;

p≤0.05, compared to SM exposed tissues.

MMP9 is a marker of extracellular matrix degradation known to play a role in SM-induced injury in mouse skin (Shakarjian et al., 2006). Immunofluorescence staining showed no MMP9 in control skin, but there was a strong induction of MMP9 in hyperplastic epidermis and hair follicles after SM exposure. MMP9 expression was also noted in the stratum spinosum and the basal layer (Figure 7). Following NDH 4338 treatment, a reduction in MMP9 expression was evident in the epidermis and dermal appendages.

Figure 7.

Effects of NDH 4338 on SM-induced MMP9 expression in mouse skin. MMP9 was visualized by confocal microscopy using a secondary antibody conjugated to Dylight 549 (red). Control mouse skin (panel A), SM (panel B), SM plus vehicle control (panel C), and SM plus NDH 4338 (panel D). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (shown in blue), scale bar = 20 µm.

Effects of NDH 4338 on markers of wound repair

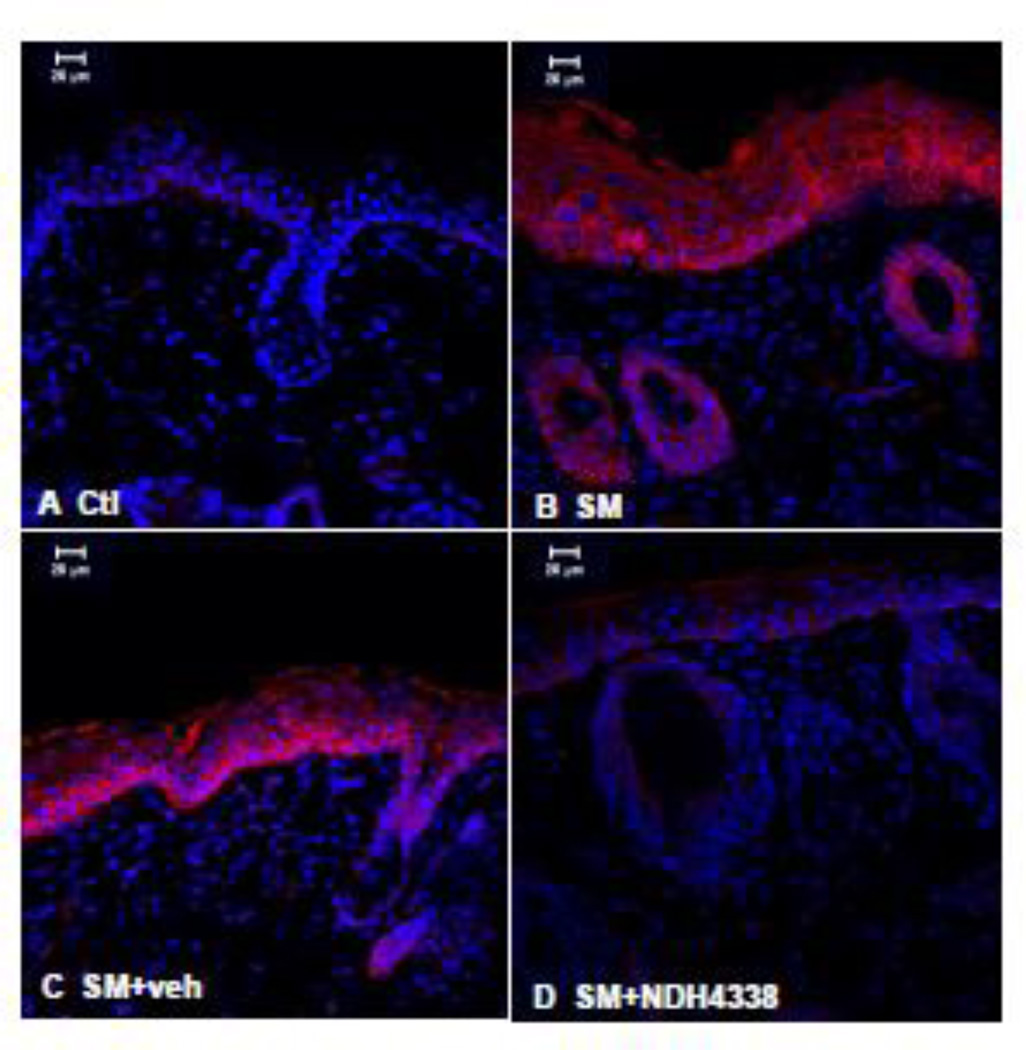

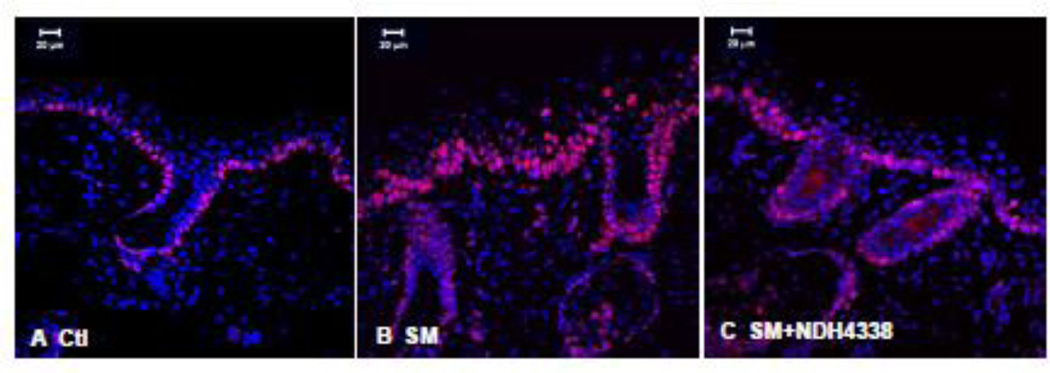

Suprabasal differentiating keratinocytes are known to express K10 (Fuchs, 1990). We found that K10 expression in control tissue was evident in keratinocytes in suprabasal layers and in the stratum corneum, but not in basal keratinocytes or in sebaceous glands and hair follicles of hairless mouse skin (Figure 8). SM upregulated K10 expression in hyperplastic epidermis and dermal appendages. Following NDH 4338 treatment, increased K10 expression was noted throughout the suprabasal layers of the epidermis, as well as the dermal appendages. The immunofluorescence mean staining parameters of K10 staining showed scores of 3.7, 2.8, and 3.8, in skin samples of control, SM exposed,and SM exposed plus NDH4338 treatment, respectively, based on 1 as no expression and 4 as intense staining (Table1).

Figure 8.

Effects of NDH 4338 on SM-induced alterations in K10 expression in mouse skin. K10 was visualized by confocal microscopy using a secondary antibody conjugated to Dylight 549 (red). Control mouse skin (panel A), SM (panel B), SM plus vehicle control (panel C), and SM plus NDH 4338 (panel D). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (shown in blue), scale bar = 20 µm.

K6, a mediator of epithelial wound repair and cell migration, was constitutively expressed at low levels in control skin (Figure 9). Four days post SM exposure, an increase in K6 expression was evident throughout the hyperplastic suprabasal epidermis. NDH 4338 decreased K6 expression (Figure 9). Evaluation of the immunofluorescence mean staining intensity indicated a significant difference of K6 expression in skin samples for control (2.0), SM exposed (3.9), and SM exposed plus NDH4338 treatment (2.6), as shown in Table 1.

Figure 9.

Effects of NDH 4338 on SM-induced alterations in K6 expression in mouse skin. K6 was visualized by confocal microscopy using a secondary antibody conjugated to Dylight 549 (red). Control mouse skin (panel A), SM (panel B), SM plus vehicle control (panel C), and SM plus NDH 4338 (panel D). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (shown in blue), scale bar = 20 µm.

Ki67 is a nuclear protein expressed in proliferating cells in response to injury (Freedberg et al., 2001). In control skin, only basal keratinocytes were found to express Ki67 (Figure 10). Following SM exposure, increased numbers of suprabasal keratinocytes in the hyperplastic epithelium and the dermal appendages expressed Ki67. In addition, Ki67 positive cells, which are likely inflammatory cells, were evident in the dermis (Figure 10). NDH 4338 treatment reduced the number of suprabasal and follicular cells expressing Ki67.

Figure 10.

Effects of NDH 4338 on SM-induced alterations in Ki67 expression in mouse skin. Ki67 was visualized by confocal microscopy using a secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (shown in red). Control mouse skin (panel A), SM (panel B), SM plus vehicle control (panel C), and SM plus NDH 4338 (panel D). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (shown in blue), scale bar = 20 µm.

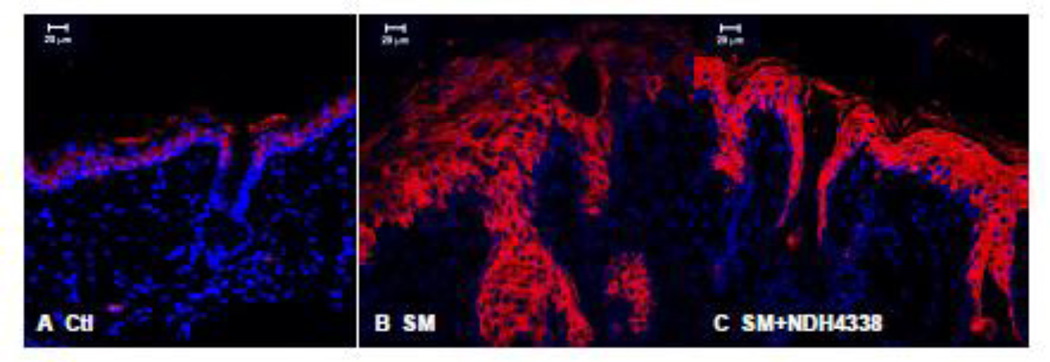

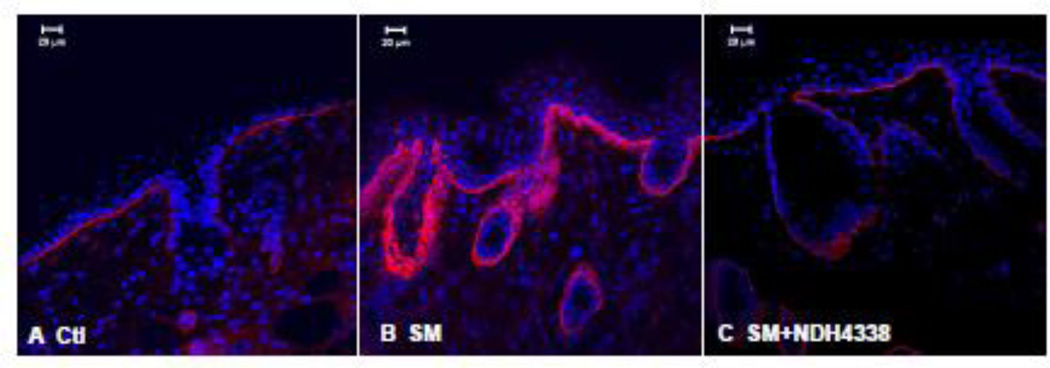

Laminin 332 is an essential anchoring glycoprotein found in the basement membrane of epithelial tissues; it is important in attaching basal keratinocytes to the dermis. In control skin laminin 332 was expressed as a continuous sheet beneath basal keratinocytes and lining the sebaceous glands and hair follicles (Figure 11). Treatment of mice with SM resulted in increased laminin 332 expression which appeared in thicker multilayered sheets. Laminin 332 expression was also prominent around dermal appendages including sebaceous glands and hair follicles. NDH 4338 mitigated this response in the basement membrane. The immunofluorescence mean intensity parameter analysis showed no significant difference between controls (2.0) and NDH4338 treated samples (2.3). SM injured skin had mean immunofluorescence intensity value of 3.2 (Table 1).

Figure 11.

Effects of NDH 4338 on SM-induced expression of laminin 332 in mouse skin. Laminin 332 was visualized by confocal microscopy using a secondary antibody conjugated to Dylight 549 (red). Control mouse skin (panel A), SM (panel B), SM plus vehicle control (panel C), and SM plus NDH 4338 (panel D). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (shown in blue), scale bar = 20 µm.

DISCUSSION

NDH 4338 is a bifunctional NSAID-AChEI anti-inflammatory compound designed to target SM-induced cutaneous injury by inhibiting AChE and releasing an NSAID in vivo (Young et al., 2012). The NSAID moiety, indomethacin, is a non-selective COX inhibitor, which has been shown to display limited efficacy against SM in the mouse ear vesicant model (MEVM) (Casillas et al., 2000). In porcine skin, indomethacin reduces COX-2 mediated PGE2 production, which may contribute to its protective activity against SM-induced inflammation (Zhang et al., 1995). The inclusion of an anti-cholinergic drug in NDH 4338 was based on recent studies showing the potential usefulness of targeting non-neuronal cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathways for the treatment of skin diseases and vesicant-induced blisters (Grando et al., 1993; Kurzen et al., 2007; Tracey, 2007; Curtis and Radek, 2012). The neurotransmitter, acetylcholine and cholinergic enzymes are produced by keratinocytes and infiltrating leukocytes during inflammatory responses; the skin cholinergic system is thought to regulate keratinocyte proliferation, differentiation, adhesion, and migration (Grando, 1997; Kurzen et al., 2007). NDH 4338 was first reported to show efficacy against half mustard-induced edema in the mouse ear vesicant model (Young et al., 2010; Young et al., 2012). The present studies demonstrate that NDH 4338 can also protect, at least in part, the dorsal skin of hairless mice from SM-induced injury; these findings suggest that NDH 4338 may be useful as a countermeasure against vesicant-induced skin injury.

By generating PGE2, COX2 functions as a pro-inflammatory protein in SM-induced cutaneous injury (Yourick et al., 1995; Babin et al., 2000; Casillas et al., 2000; Wormser et al., 2004;Joseph et al., 2011). Previous studies have shown that SM induces the release of arachidonic acid and metabolites including prostaglandins in human keratinocytes and a mouse neuroblastoma-rat glioma hybrid cell line (Ray et al., 1995; Lefkowitz and Smith, 2002). Using a skin construct model, Black et al (2010) also showed increased COX2 and prostaglandin production after exposure to the half mustard, CEES. In mouse skin, SM has also been shown to induce COX2 in keratinocytes, hair follicles, dermal fibroblasts, and inflammatory cells near wound edges (Wormser et al., 2004; Joseph et al., 2011). The present studies show that 4 days post SM exposure, COX2 is upregulated in mouse dorsal skin. COX2 is known to play a critical role in skin inflammation. Signaling via PGE2 and its receptor induces vascular hyperpermeability and dermal edema (Rundhaug and Fischer, 2008; Zanoni et al., 2012; Morimoto et al., 2014). Our findings that inhibition of COX2 by NDH 4338 was associated with reduced edema and inflammation are consistent with a role for prostaglandins in vesicantinduced skin injury.

SM-induced toxicity is associated with reduced adhesion of basal keratinocytes and detachment of these cells from the basement membrane zone (Ruhl et al., 1994; Graham et al., 2005; Saladi et al., 2006). Epidermal keratins are essential for maintaining skin integrity including basal keratinocyte adhesion; mutations in epidermal keratins result in perturbation of filament assembly, which can lead to skin blistering diseases (Fuchs, 1995; Uitto et al., 2007). In vitro studies have shown that mustard vesicants induce aggregation of keratins 5 and 14; this can alter keratin filament assembly and contribute to keratinocyte detachment from the basement membrane (Dillman et al., 2003; Hess and FitzGerald, 2007). Previous studies reported a significant reduction in expression of K10 in SM treated mouse skin 3 days post exposure, and increased K10 expression in the hyperplastic epidermis 14 days post exposure (Joseph et al.,2011). Similarly, we found reduced expression of K10 in the suprabasal layer of hyperplastic epidermis 4 days after SM exposure; this was blocked by NDH 4338 indicating wound repair. The wound marker, K6, was also strongly expressed in SM exposed skin at this time. NDH 4338 caused a reduction of K6 in treated mouse skin providing additional support for enhanced wound repair. Moreover, the strong signal for Ki67 in SM exposed skin indicates keratinocyte hyperproliferation in both suprabasal and basal layers in response to injury; Ki67 positive cells were restricted to basal keratinocytes in SM injured skin after NDH 4338 treatment. This observation is similar to the reduction of Ki67 expression observed after closure of excisional wounds (Usui et al., 2005). These observations indicate that NDH 4338 promotes wound healing and keratinocyte differentiation.

One of the most visible characteristics of SM-induced human cutaneous lesions is severe blister formation resulting from the separation of the epidermis from the dermis (Smith et al., 1995). Earlier work on the cutaneous genetic blistering disease, epidermolysis bullosa, showed that this is due to mutations in the adhesive basement membrane glycoprotein, laminin 332 (Nakano et al., 2002). SM has also been shown to cause microvesication in mouse skin, with focal epidermal staining of laminin, resulting from the separation of the DEJ. This suggests a precise cleavage plane of the DEJ within the lamina lucida (Monteiro-Riviere and Inman, 1995). Laminin 332 has been reported to be upregulated and expressed at the migrating leading edge of SM wounded mouse skin (Chang et al., 2009). Since laminin 332 is an essential anchoring filament attaching basal keratinocytes to the basement membrane in the lamina lucida, we analyzed its expression as a marker for basement membrane zone wound repair. We found thick multilayered expression of laminin 332 in the basement membrane zone, and more focal staining around edematous dermal appendages in SM-injured skin. These data are consistent with studies showing a multilayered and partly disrupted laminin 332 sheet in aged, sun-exposed injury, and in UV-irradiated skin models (Pageon et al., 2007; Ogura et al., 2008). MMPs are key effectors of extracellular matrix remodeling and are thought to contribute to the impairment of the basement membrane and degradation of its components including laminin 332, and type IV and VII collagens during injury (Ogura et al., 2008). In this regard, inhibition of MMPs and other proteinases enhances basement membrane formation in UVB irradiated human skin and human skin construct models (Fisher et al., 1996; Ogura et al., 2008; Amano, 2009). Our studies showed that laminin 332 was more organized in NDH 4338 treated skin indicating reduced damage to the basement membrane zone. We also observed reduced expression of MMP9 in NDH 4338 treated SM injured skin. Consistent with previous findings (Vogt et al., 1984; Shakarjian et al., 2010), these data suggest that MMP9 plays a role in SM-induced basement membrane restoration after NDH 4338 treatment.

Inflammation is a complex process involving many cell types, cytokines, chemokines, proteases, and other factors that mediate wound repair. Our data show that NDH 4338 improves wound repair following SM-induced skin injury. Wound repair was evident by the reduction of skin edema, enhanced skin re-epithelialization, a fully differentiated epidermis, and a well-structured basement membrane zone following NDH 4338 treatment of SM wounded skin. This was associated with reduced expression of COX2 and MMP9. Additional studies will help to further characterize the anti-inflammatory mechanism of action of NDH 4338 and its effects on wound repair in the SM induced skin injury model.

Highlights.

Bifunctional anti-inflammatory prodrug (NDH4338) tested on SM exposed mouse skin.

The prodrug NDH4338 was designed to target COX2 and acetylcholinesterase.

The application of NDH4338 improved cutaneous wound repair after SM induced injury.

NDH4338 treatment demonstrated a reduction in COX2 expression on SM injured skin.

Changes of skin repair markers are associated with NDH4438 treatment on SM injury.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the CounterACT Program, National Institutes of Health Office of the Director (NIH OD), and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), grant number U54AR055073. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the federal government. This work was also supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants P30ES005022, and R01EY09056. Appreciation is extended to Linda Everett of EOHSI for editorial assistance.

Abbreviation List

- AChEI

acetylcholinesterase inhibitor

- CEES

2-chloroetheyl ethyl sulfide

- COX2

cyclooxygenase 2

- DEJ

dermal-epidermal junction

- K6

keratin 6

- K10

keratin 10

- LM332

laminin 332

- MMP9

Matrix Metalloproteinase 9

- NSAID

Non-steroidal anti-inflamma drug

- SM

sulfur mustard

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Amano S. Possible involvement of basement membrane damage in skin photoaging. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2009;14:2–7. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2009.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babin MC, Ricketts K, Skvorak JP, Gazaway M, Mitcheltree LW, Casillas RP. Systemic administration of candidate antivesicants to protect against topically applied sulfur mustard in the mouse ear vesicant model (MEVM) J Appl Toxicol. 2000;20(Suppl 1):S141–S144. doi: 10.1002/1099-1263(200012)20:1+<::aid-jat666>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benavides F, Oberyszyn TM, VanBuskirk AM, Reeve VE, Kusewitt DF. The hairless mouse in skin research. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;53:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black AT, Joseph LB, Casillas RP, Heck DE, Gerecke DR, Sinko PJ, Laskin DL, Laskin JD. Role of MAP kinases in regulating expression of antioxidants and inflammatory mediators in mouse keratinocytes following exposure to the half mustard, 2-chloroethyl ethyl sulfide. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;245:352–360. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casillas RP, Kiser RC, Truxall JA, Singer AW, Shumaker SM, Niemuth NA, Ricketts KM, Mitcheltree LW, Castrejon LR, Blank JA. Therapeutic approaches to dermatotoxicity by sulfur mustard. I. Modulaton of sulfur mustard-induced cutaneous injury in the mouse ear vesicant model. J Appl Toxicol. 2000;20(Suppl 1):S145–S151. doi: 10.1002/1099-1263(200012)20:1+<::aid-jat665>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YC, Sabourin CL, Lu SE, Sasaki T, Svoboda KK, Gordon MK, Riley DJ, Casillas RP, Gerecke DR. Upregulation of gamma-2 laminin-332 in the mouse ear vesicant wound model. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2009;23:172–184. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SG, Chishti SB, Elkind JL, Reese H, Cohen JB. Effects of charge, volume, and surface on binding of inhibitor and substrate moieties to acetylcholinesterase. J Med Chem. 1985;28:1309–1313. doi: 10.1021/jm00147a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis BJ, Radek KA. Cholinergic regulation of keratinocyte innate immunity and permeability barrier integrity: new perspectives in epidermal immunity and disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:28–42. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillman JF, 3rd, McGary KL, Schlager JJ. Sulfur mustard induces the formation of keratin aggregates in human epidermal keratinocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2003;193:228–236. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher GJ, Datta SC, Talwar HS, Wang ZQ, Varani J, Kang S, Voorhees JJ. Molecular basis of sun-induced premature skin ageing and retinoid antagonism. Nature. 1996;379:335–339. doi: 10.1038/379335a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedberg IM, Tomic-Canic M, Komine M, Blumenberg M. Keratins and the keratinocyte activation cycle. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:633–640. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E. Epidermal differentiation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1990;2:1028–1035. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(90)90152-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs E. Keratins and the skin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:123–153. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.001011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JS, Chilcott RP, Rice P, Milner SM, Hurst CG, Maliner BI. Wound healing of cutaneous sulfur mustard injuries: strategies for the development of improved therapies. J Burns Wounds. 2005;4:e1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grando SA. Biological functions of keratinocyte cholinergic receptors. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1997;2:41–48. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.1997.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grando SA, Kist DA, Qi M, Dahl MV. Human keratinocytes synthesize, secrete, and degrade acetylcholine. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:32–36. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12358588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess JF, FitzGerald PG. Treatment of keratin intermediate filaments with sulfur mustard analogs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;359:616–621. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph LB, Gerecke DR, Heck DE, Black AT, Sinko PJ, Cervelli JA, Casillas RP, Babin MC, Laskin DL, Laskin JD. Structural changes in the skin of hairless mice following exposure to sulfur mustard correlate with inflammation and DNA damage. Exp Mol Pathol. 2011;91:515–527. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katori M, Majima M. Cyclooxygenase-2: its rich diversity of roles and possible application of its selective inhibitors. Inflamm Res. 2000;49:367–392. doi: 10.1007/s000110050605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehe K, Balszuweit F, Steinritz D, Thiermann H. Molecular toxicology of sulfur mustard-induced cutaneous inflammation and blistering. Toxicology. 2009;263:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurzen H, Wessler I, Kirkpatrick CJ, Kawashima K, Grando SA. The non-neuronal cholinergic system of human skin. Horm Metab Res. 2007;39:125–135. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-961816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JL, Mukhtar H, Bickers DR, Kopelovich L, Athar M. Cyclooxygenases in the skin: pharmacological and toxicological implications. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2003;192:294–306. doi: 10.1016/s0041-008x(03)00301-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz LJ, Smith WJ. Sulfur mustard-induced arachidonic acid release is mediated by phospholipase D in human keratinocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;295:1062–1067. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00811-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro-Riviere NA, Inman AO. Indirect immunohistochemistry and immunoelectron microscopy distribution of eight epidermal-dermal junction epitopes in the pig and in isolated perfused skin treated with bis (2-chloroethyl) sulfide. Toxicol Pathol. 1995;23:313–325. doi: 10.1177/019262339502300308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro-Riviere NA, Inman AO. Ultrastructural characterization of sulfur mustardinduced vesication in isolated perfused porcine skin. Microsc Res Tech. 1997;37:229–241. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19970501)37:3<229::AID-JEMT8>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro-Riviere NA, Inman AO, Babin MC, Casillas RP. Immunohistochemical characterization of the basement membrane epitopes in bis(2-chloroethyl) sulfide-induced toxicity in mouse ear skin. J Appl Toxicol. 1999;19:313–328. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1263(199909/10)19:5<313::aid-jat582>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto K, Shirata N, Taketomi Y, Tsuchiya S, Segi-Nishida E, Inazumi T, Kabashima K, Tanaka S, Murakami M, Narumiya S, Sugimoto Y. Prostaglandin E2-EP3 Signaling Induces Inflammatory Swelling by Mast Cell Activation. J Immunol. 2014;192:1130–1137. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano A, Chao SC, Pulkkinen L, Murrell D, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Pfendner E, Uitto J. Laminin 5 mutations in junctional epidermolysis bullosa: molecular basis of Herlitz vs. non-Herlitz phenotypes. Hum Genet. 2002;110:41–51. doi: 10.1007/s00439-001-0630-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura Y, Matsunaga Y, Nishiyama T, Amano S. Plasmin induces degradation and dysfunction of laminin 332 (laminin 5) and impaired assembly of basement membrane at the dermal-epidermal junction. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:49–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pageon H, Bakala H, Monnier VM, Asselineau D. Collagen glycation triggers the formation of aged skin in vitro. Eur J Dermatol. 2007;17:12–20. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2007.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papirmeister B, Gross CL, Meier HL, Petrali JP, Johnson JB. Molecular basis for mustard-induced vesication. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1985;5:S134–S149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrali JP, Oglesby-Megee S. Toxicity of mustard gas skin lesions. Microsc Res Tech. 1997;37:221–228. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19970501)37:3<221::AID-JEMT7>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray R, Legere RH, Majerus BJ, Petrali JP. Sulfur mustard-induced increase in intracellular free calcium level and arachidonic acid release from cell membrane. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1995;131:44–52. doi: 10.1006/taap.1995.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reale M, Greig NH, Kamal MA. Peripheral chemo-cytokine profiles in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2009;9:1229–1241. doi: 10.2174/138955709789055199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal DS, Simbulan-Rosenthal CM, Iyer S, Spoonde A, Smith W, Ray R, Smulson ME. Sulfur mustard induces markers of terminal differentiation and apoptosis in keratinocytes via a Ca2+calmodulin and caspase-dependent pathway. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:64–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell M, Kehe K, Balszuweit F, Thiermann H. The chronic effects of sulfur mustard exposure. Toxicology. 2009;263:9–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruff AL, Dillman JF. Signaling molecules in sulfur mustard-induced cutaneous injury. Eplasty. 2007;8:e2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhl CM, Park SJ, Danisa O, Morgan RF, Papirmeister B, Sidell FR, Edlich RF, Anthony LS, Himel HN. A serious skin sulfur mustard burn from an artillery shell. J Emerg Med. 1994;12:159–166. doi: 10.1016/0736-4679(94)90693-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rundhaug JE, Fischer SM. Cyclo-oxygenase-2 plays a critical role in UV-induced skin carcinogenesis. Photochem Photobiol. 2008;84:322–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabourin CL, Petrali JP, Casillas RP. Alterations in inflammatory cytokine gene expression in sulfur mustard-exposed mouse skin. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2000;14:291–302. doi: 10.1002/1099-0461(2000)14:6<291::AID-JBT1>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saladi RN, Smith E, Persaud AN. Mustard: a potential agent of chemical warfare and terrorism. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2005.01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakarjian MP, Bhatt P, Gordon MK, Chang YC, Casbohm SL, Rudge TL, Kiser RC, Sabourin CL, Casillas RP, Ohman-Strickland P, Riley DJ, Gerecke DR. Preferential expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in mouse skin after sulfur mustard exposure. J Appl Toxicol. 2006;26:239–246. doi: 10.1002/jat.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakarjian MP, Heck DE, Gray JP, Sinko PJ, Gordon MK, Casillas RP, Heindel ND, Gerecke DR, Laskin DL, Laskin JD. Mechanisms mediating the vesicant actions of sulfur mustard after cutaneous exposure. Toxicol Sci. 2010;114:5–19. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KJ, Hurst CG, Moeller RB, Skelton HG, Sidell FR. Sulfur mustard: its continuing threat as a chemical warfare agent, the cutaneous lesions induced, progress in understanding its mechanism of action, its long-term health effects, and new developments for protection and therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:765–776. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)91457-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracey KJ. Physiology and immunology of the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:289–296. doi: 10.1172/JCI30555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uitto J, Richard G, McGrath JA. Diseases of epidermal keratins and their linker proteins. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:1995–2009. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui ML, Underwood RA, Mansbridge JN, Muffley LA, Carter WG, Olerud JE. Morphological evidence for the role of suprabasal keratinocytes in wound reepithelialization. Wound Repair Regen. 2005;13:468–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2005.00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt RF, Jr, Dannenberg AM, Jr, Schofield BH, Hynes NA, Papirmeister B. Pathogenesis of skin lesions caused by sulfur mustard. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1984;4:S71–S83. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(84)90139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wormser U, Langenbach R, Peddada S, Sintov A, Brodsky B, Nyska A. Reduced sulfur mustard-induced skin toxicity in cyclooxygenase-2 knockout and celecoxib-treated mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;200:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young S, Fabio K, Guillon C, Mohanta P, Halton TA, Heck DE, Flowers RA, 2nd, Laskin JD, Heindel ND. Peripheral site acetylcholinesterase inhibitors targeting both inflammation and cholinergic dysfunction. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:2987–2990. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.02.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SC, Fabio KM, Huang MT, Saxena J, Harman MP, Guillon CD, Vetrano AM, Heck DE, Flowers RA, 2nd, Heindel ND, Laskin JD. Investigation of anticholinergic and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory prodrugs which reduce chemically induced skin inflammation. J Appl Toxicol. 2012;32:135–141. doi: 10.1002/jat.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yourick JJ, Dawson JS, Mitcheltree LW. Reduction of erythema in hairless guinea pigs after cutaneous sulfur mustard vapor exposure by pretreatment with niacinamide, promethazine and indomethacin. J Appl Toxicol. 1995;15:133–138. doi: 10.1002/jat.2550150213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanoni I, Ostuni R, Barresi S, Di Gioia M, Broggi A, Costa B, Marzi R, Granucci F. CD14 and NFAT mediate lipopolysaccharide-induced skin edema formation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1747–1757. doi: 10.1172/JCI60688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Riviere JE, Monteiro-Riviere NA. Evaluation of protective effects of sodium thiosulfate, cysteine, niacinamide and indomethacin on sulfur mustard-treated isolated perfused porcine skin. Chem Biol Interact. 1995;96:249–262. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(94)03596-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]