Abstract

Background

There is a need to evaluate & implement cost-effective strategies to improve adherence to treatments in Coronary Heart Disease (CHD). There are no studies from Low Middle Income Countries (LMICs) evaluating trained Community Health Worker (CHW) based interventions for the secondary prevention of CHD.

Methods

We designed a hospital-based, open randomized trial of CHW based interventions versus standard care. Patients after an Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) were randomized to an intervention group (a CHW based intervention package, comprising education tools to enhance self-care and adherence, and regular follow-up by the CHW) or to standard care for 12 months during which study outcomes were recorded. The CHWs were trained over a period of 6 months. The primary outcome measure was medication adherence. The secondary outcomes were differences in adherence to lifestyle modification, physiological parameters (BP, body weight, BMI, heart rate, lipids) and major adverse cardiovascular events.

Results

We recruited 806 patients stabilized after an ACS from 14 hospitals in 13 Indian cities. The mean age was 56.4 (+/−11.32) and 17.2% were females. A high prevalence of risk factors -hypertension (43.4%), diabetes (31.9%), tobacco consumption (35.4%) and inadequate physical activity (70.5%) were documented. A little over half had ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI, 53.7%) and 46.3% had non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) or unstable angina.

Conclusion

The CHW interventions and training for SPREAD have been developed and adapted for local use. The results and experience of this study will be important to counter the burden of Cardiovascular Diseases (CVD) in LMICs.

Keywords: Community Health Workers (CHWs), Acute Coronary Syndromes, secondary prevention, randomized controlled trial

INTRODUCTION

Decline in Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) mortality in most high income countries are due to better acute treatments, therapies for secondary prevention and primary preventive measures (1). Important reasons for high mortality in India and other LMICs are the lack of adequate primary and secondary prevention strategies (2).

Smoking cessation, increased physical activity, better diets and reduced dietary fat, stress management and drug therapy that includes aspirin, statins, beta blockers and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) should be continued indefinitely for CHD patients (3,4). Improved adherence is associated with improved clinical outcomes (5). However, long-term persistence to secondary prevention therapies are low in most countries, especially in LMICs (6).

Studies have evaluated various complex interventions to improve adherence to drug therapies in CHD and other chronic diseases at the level of the community, health care providers or individual physicians and patients (7–9). Non-physician community health workers (CHW) have been successful in acute and chronic communicable diseases for prevention and treatment (10). One strategy to enhance treatment adherence could be to ensure regular patient follow up using trained health workers. Innovative strategies are required to ensure treatment adherence and enable better risk factor control. This study aims to assess if a trained & supervised CHW-based intervention, combining patient education and intensive follow-up can improve medium-term (one year) adherence to drug therapies and life-style modification in high-risk CHD patients.

METHODS

Study Design and Ethics Statement

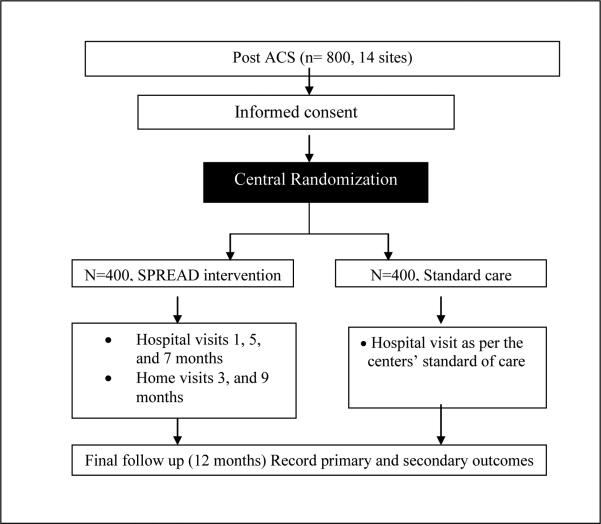

Secondary Prevention of CoRonary Events After Discharge from hospital (SPREAD) is a multicentre randomized controlled, parallel group open trial. Eligible patients are randomized equally in to interventional or control arms (Fig 1). The protocol was reviewed and approved by the National Heart, Lung & Blood Institute (NHLBI), the Indian Health Ministry Screening Committee (HMSC), the ethics committee of the Population Health Research Institute (PHRI), McMaster University, Canada and all the 14 participating centers. The informed consent forms were translated into 7 vernacular languages. All study personnel underwent National Institute of Health (NIH) Office of Human Subjects Research Protection training & certification before delegation into the study. The trial is registered with the Clinical Trials Registry of India (REF/2013/03/004737).

Figure 1.

Study flow-chart

Setting

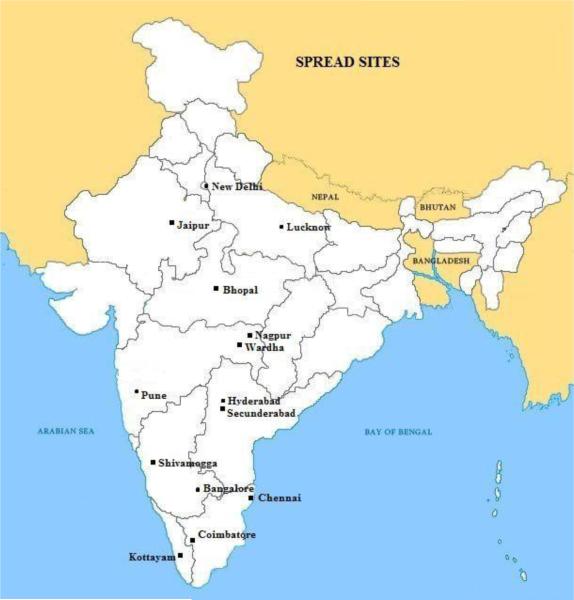

In 2008 the UnitedHealth Group and NHLBI of the National Institutes of Health (NIH, USA) established a global network of Centers of Excellence (CoE) to help combat chronic diseases in developing countries (11). St John's Medical College and Research Institute, Bangalore, India, is one of the eleven centers partnering with McMaster University, Canada as the developed country partner. SPREAD was conducted at 14 hospitals across India. Nine of these are private hospitals, one a government hospital and four are not-for-profit. 12 of these are PCI enabled and 2 are not PCI enabled hospitals. Geographic distribution of these hospitals is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Map of India showing location of the study sites

Participants

Consecutive patients admitted with a clinical diagnosis of ACS (standard definitions used) aged > 18 years were identified. We included patients being discharged who broadly consented to study procedures (details below).

We excluded those living more than 120 kms (75 miles) away or not expected to survive the study duration of one year (complications of ACS such as heart failure or other terminal illnesses).

Study personnel

At each participating centre, CHWs were trained and supervised by a SPREAD Project Officer (SPO), who in turn was overseen by the Principal Investigator.

SPREAD Project Officer (SPO)

The SPO had a health sciences background with at least one year's experience of running other clinical trials. The SPO was responsible for overall coordination and supervising the activities of the CHW, randomizing patients and managing data.

Community health worker (CHW)

The CHW had 12th grade education, good communication skills in vernacular languages, some knowledge of English and had familiarity with a hospital setting. The CHW interacted only with patients in the SPREAD Intervention Group (SIG).

Intervention Tools

We developed and adapted tools to encourage patient self-care and enhance adherence to treatments. The patient diary contained information on ischemic heart disease, its risk factors, treatments, the importance of treatment compliance and sections for documenting the patients’ risk factors and targets to be attained at subsequent follow up visits. The VIsual Tool for Adherence (VITA) is a calendar check list for the four important medications, on which participants mark every time they take their dose. The tool serves as a reminder and to record medication intake.

Training for study staff

The SPOs underwent a three day training at the NCO (St. John's, Bangalore). They provided inputs to finalize the 8-volume CHW training manual which was then translated into 6 vernacular languages. They also learnt to train and monitor the activities of the CHWs. The SPOs trained the CHWs at their site over 6 months. The CHWs were trained to form a rapport with the patient and caregiver, take history, measure blood pressure, waist to hip ratio, BMI and pulse rate. They were trained to refer to the PI or SPO if they identified ‘danger symptoms/ signs’ or uncontrolled risk factors. Pocket manuals contained a description of the cut-offs for these risk factors. They were also trained to counsel patients on medications and lifestyle modification and to identify barriers to adherence and offer mutually developed strategies. Pre and post-tests evaluated the knowledge gained. The CHWs and SPOs came to the NCO for final training and evaluation. This was done in small groups and by region to facilitate training in 2 to 3 regional languages each. At this training, we evaluated the knowledge and ability of the team to carry out activities. About 6 months after trial initiation at all sites, we held refresher training for the SPOs and CHWs for 2 days to facilitate knowledge exchange between different teams and to reinforce skills.

Evaluation of CHWs

We evaluated the performance of health workers centrally in two ways during the course of the study. One, by assessing randomly selected completed health workers forms sent to the NCO. Scores were assigned to key activities performed, and CHWs who scored < 75% were retrained over telephone by central SPREAD project officers and reassessed. Two, by structured telephone interviews with SPOs and CHWs to assess their knowledge and skills.

Informed consent

The site Principal Investigator and the SPO obtained informed consent from study subjects after explaining trial procedures. For those who could not provide written consent a witnessed verbal consent and thumb impression was obtained. The informed consent form (ICF) was prepared in English and translated into seven local languages.

Randomization

Patients were randomized centrally into either the interventional or the standard care arm with equal allocation ratio. The randomization was stratified by centre and using permuted variable block sizes of 4 and 6. The CHW was not involved in patient screening, informed consent or randomization, to ensure patients in the standard care group did not come in contact with the health worker.

Procedure in the intervention arm

At discharge, the Principal Investigator (PI), SPO and CHW explained the interventions and follow-up schedule. The CHW then explained secondary prevention strategies (medications and life style modification and its importance) and trained on using the tools. Importantly, the CHW builds a good relationship with the patient and caregivers at discharge.

At hospital visits (1, 5 and 7 months) the CHW assessed risk factors, reviewed key investigations, set targets for life style modifications and collected medication adherence data. If needed, the CHW consulted the SPO or the PI to consider changes in medication and to address the barriers to adherence the patient may have.

Home visits (3 & 9 months) were fixed at a mutually convenient time when the patient's family was at home. At home visits, CHWs collected basic clinical data, reviewed risk factors and medication adherence. Towards the end of the home visit, the CHW called the SPO to review the patient's status. If necessary the PI is contacted and modification to drugs or life style are suggested. Barriers to adherence were inquired for and strategies were provided.

At final visit (12 months), in addition to usual activity during hospital visit the CHW informed that it was the last visit for the study. The CHW would provide a summary of the patient's status and performance for adherence to medication and life style modifications. The patient is then referred to the PI and SPO for future management. In-between visits patients were encouraged to call the CHW for any health related matters. The CHW provided advice in consultation with the SPO or PI.

Assessment of Adherence to Medications

We used an adherence score, percentage of the doses taken of that prescribed - for estimating medication adherence. The adherence scores were calculated for – Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone System (RAAS) blockers, beta blockers, aspirin, non-aspirin antiplatelets and statins based for the month prior to the follow up visit based on patient self report. A ‘composite adherence score’ indicating the mean of the adherence scores of individual classes were calculated by the database. At follow up visits, the 8-item modified Morisky's medication adherence scale (12) was also used to assess the patient's adherence to medications. Whenever medications were prematurely stopped, particularly due to patient decision, the reasons for non-adherence were elicited.

Assessing adherence to life style modification

We used patient self reports & primary caregiver reports to assess tobacco and alcohol consumption. At the final follow up visit, patients categorized as ‘current’ consumers were reclassified as ‘former’ consumers if they quit tobacco at least ≥ 1 month prior to the final visit. Exercise was classified as none, sedentary (< 30 minutes, < 3 days/ week), moderate (> 30 minutes, 3-4 times/ week) and intense (> 30 minutes 6-7 times/ week). Diet was assessed using a simple 5-point questionnaire and a score was computed. This simplified questionnaire was created for ease of use by the CHW. The questionnaire included elements on weekly consumption of vegetables and fruits, whole grain and high fiber foods, sweets, refined grains, deep fried and salty foods and red meat. A maximum score of 5 indicated a healthy diet, while a minimum score of 0 indicated an unhealthy diet.

Process in the Standard Care Group

Patients in the standard care group were followed up as per their treating physician's discretion. The CHW was not aware of these patients and did not come in contact with them at any point of time. At these follow up visits the SPO collected data on clinical status. At the end of 12 months, the SPO actively followed up patients and collected data on medication and lifestyle adherence for the last one month and recorded clinical events over the last one year.

Assessing the acceptability of interventions

We will conduct a mixed methods study at the end of the trial. Among randomly selected patients (20% at each site) we will assess their overall experience and use of the tools and among CHWs to assess the acceptability of the tools and study procedures.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome is the difference in adherence levels to evidence based medications for the secondary prevention of CHD at one year. The secondary outcomes are differences in lifestyle factors (diet, exercise, tobacco & alcohol use), clinical outcomes –physiological parameters (blood pressure, body weight, BMI, heart rate and lipids) and clinical events – the composite of cardiovascular deaths, non-fatal strokes and myocardial infarctions.

Study quality and data management

Trained staff from the NCO conducted at least one on-site monitoring visit at all sites. In addition, monitors whenever possible directly verified the CHW's activities at the visit. The CHW collected data from patients in the intervention arm on a simple form that is translated in the local language that the patient also understands. The SPO used this form to fill data on to the online CRFs. Quality control reports for incomplete and inconsistent data are generated online and the SPO resolved these queries.

Sample size and statistical analysis

We assumed an average adherence percentage to prescribed medications for secondary prevention of CHD at one year to be 60% (SD 49.0%). In the intervention group, we assumed adherence to improve by 10%. With these assumptions 400 patients per group will have 90% power to detect a difference of 10%. An attrition rate of 10% was accounted for. Patients will be classified as adherent if the composite percentage adherence is ≥80%. We will compare the difference in the proportion of patients’ adherent to evidence based medications and lifestyle modification parameters between the 2 groups using Chi squared test.

As there are multiple follow-ups in the intervention group, Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) will be carried out in this group to identify potential baseline predictors of adherence. We will compare time to discontinuation of recommended therapy between intervention and standard care groups using Kaplan-Meier analysis and log rank test. Patients lost to follow up will be right censored in the KM analysis. We will identify demographic and clinical predictors for time to discontinuation of treatments using Cox regression. All testing will be done at 0.05 level of significance and is set for two-tailed tests. The analysis will be done on an intention to treat basis. We will use SAS version 9.1.3 for analysis.

STUDY PROGRESS & PRELIMINARY RESULTS

We recruited 806 patients from 14 sites between July 2011 and June 2012. The trial completed follow up of all patients by the end of June 2013 with 98% patients in both the groups completing follow up. During the course of the study, 21 CHWs were identified and appointed at the 14 centers. Three sites that recruited more than 80 participants identified and trained an additional CHW.

The mean age of participants is 56.4 (+/−11.32) and 17.2% are females. Most patients (58.2%) are from urban areas. Two thirds (66.0%) are from lower middle or poor social economic classes. There is a high prevalence of risk factors in the study population – hypertension (43.4%), diabetes (31.9%), tobacco consumption (35.4%), inadequate physical activity (70.5%) and consumption of unhealthy diet (51.2%). History of prior drug use for CVD risk factors was as follows: antiplatelets 17.6%, antihypertensives 38.3% and antidiabetics 26.2%. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Patient demographics, risk factors for coronary heart disease and medication history

| Variable | Overall N (%) | Intervention N (%) | Standard care N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 806 | 405 (50.2) | 401 (49.8) | |

| Age | Mean (SD) | 56.4 (11.32) | 55.9 (11.43) | 56.9 (11.2) |

| Gender | Male | 667 (82.8) | 334 (82.5) | 333 (83.0) |

| Female | 139 (17.2) | 71 (17.5) | 68 (17.0) | |

| Education | None | 98 (12.2) | 45 (11.1) | 53 (13.2) |

| Any school | 412 (51.1) | 205 (50.6) | 207 (51.6) | |

| University/Higher | 296 (36.7) | 155 (38.3) | 141 (35.2) | |

| Area of Residence | Urban | 469 (58.2) | 237 (58.5) | 232 (57.9) |

| Rural | 196 (24.3) | 103 (25.4) | 93 (23.2) | |

| Semi Urban | 141 (17.5) | 65 (16.0) | 76 (19.0) | |

| Socio Economic Status | Rich | 10 (1.2) | 4 (1.0) | 6 (1.5) |

| Upper middle | 264 (32.8) | 135 (33.3) | 129 (32.2) | |

| Lower middle | 459 (56.9) | 235 (58.0) | 224 (55.9) | |

| Poor | 73 (9.1) | 31 (7.7) | 42 (10.5) | |

| Lifestyle | ||||

| Tobacco Use | Never | 441 (54.7) | 227 (56.0) | 214 (53.4) |

| Former | 80 (9.9) | 40 (9.9) | 40 (10.0) | |

| Current | 285 (35.4) | 138 (34.1) | 147 (36.7) | |

| Passive exposure to Tobacco smoke | 163 (20.2) | 85 (21.0) | 78 (19.5) | |

| Deep fried food or red meats > 3/ week | 413 (51.2) | 190 (46.9) | 223 (55.6) | |

| Salty foods or fast foods > 3/ week | 367 (45.5) | 167 (41.2) | 200 (49.9) | |

| Sugary drinks or sweets > 3/ week | 293 (36.4) | 139 (34.3) | 154 (38.4) | |

| Whole grains/ high fiber foods < 5/week | 495 (61.4) | 252 (62.2) | 243 (60.6) | |

| Fruits or vegetables <5 per week | 477 (59.2) | 234 (57.8) | 243 (60.6) | |

| Physical Activity | None | 265 (32.9) | 127 (31.4) | 138 (34.4) |

| Sedentary | 303 (37.6) | 153 (37.8) | 150 (37.4) | |

| Moderate | 192 (23.8) | 102 (25.2) | 90 (22.4) | |

| Intense | 46 (5.7) | 23 (5.7) | 23 (5.7) | |

| Current alcohol consumption | 155 (19.2) | 80 (19.8) | 75 (18.7) | |

| Risk Factors | ||||

| Hypertension | 350 (43.4) | 174 (43.0) | 176 (43.9) | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 257 (31.9) | 130 (32.1) | 127 (31.7) | |

| Dyslipidemia | 53 (6.6) | 34 (8.4) | 19 (4.7) | |

| TIA/CVA | 22 (2.7) | 9 (2.2) | 13 (3.2) | |

| Family history of premature CAD | 99 (12.3) | 55 (13.6) | 44 (11.0) | |

| Medication History (Drugs taken for a month prior to hospitalization) | ||||

| Anti Hypertensive | 309 (38.3) | 151 (37.3) | 158 (39.4) | |

| Antidiabetics | 211 (26.2) | 110 (27.2) | 101 (25.2) | |

| Adherence Pattern before hospitalization | ||||

| Patient required to take any medication daily in the last one month prior to the event | 429 (53.2) | 215 (53.1) | 214 (53.4) | |

| Forgot to take medication > once a week | 128 (29.8) | 68 (31.6) | 60 (28.0) | |

| Stopped medication on his/her own | 62 (14.5) | 41 (19.1) | 21 (9.8) | |

| Takes medication on time | 305 (71.1) | 147 (68.4) | 158 (73.8) | |

The mean BP is 124.7/78.2±18.26; waist to hip ratio is 1.0±0.11 and BMI 25.2±4.02. A little over half had ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI, 53.7%) and 46.3% had non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) or unstable angina (Table 2). At discharge the prescription rates of evidence-based medications for secondary prevention were satisfactory and most patients received advice on the importance of medication adherence and lifestyle modification (Table 3).

Table 2.

Baseline physical examination parameters, diagnosis and in-hospital treatments

| Variable | Intervention N = 405 | Standard care N = 401 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time (hours) - Symptom onset to hospital | Median (Q1-Q3) | 6.0 (2.2-26.0) | 6.3 (2.5-27.5) |

| Physical Examination | |||

| Systolic BP | Mean (SD) | 124.1 (17.94) | 125.3 (18.59) |

| Diastolic BP | Mean (SD) | 78.0 (9.66) | 78.4 (10.33) |

| Waist to Hip Ratio | Mean (SD) | 1.0 (0.07) | 1.0 (0.13) |

| Body Mass Index | Mean (SD) | 25.3 (4.20) | 25.0 (3.83) |

| Diagnosis and in hospital treatment | |||

| Diagnosis | UA | 123 (30.4) | 107 (26.7) |

| NSTEMI | 68 (16.8) | 75 (18.7) | |

| STEMI | 214 (52.8) | 219 (54.6) | |

| Treatment in Hospital | Thrombolysed (STEMI) | 117 (54.7) | 117 (53.4) |

| Coronary Intervention | 235 (58.0) | 240 (59.9) | |

| Medically Managed | 170 (42.0) | 161 (40.1) | |

| Coronary Intervention | PCI | 225 (55.6) | 222 (55.4) |

| CABG | 10 (2.5) | 18 (4.5) |

Table 3.

Patient counseling and medications at discharge

| Variable | Intervention N = 405 | Standard care N = 401 |

|---|---|---|

| Counseling | ||

| Medication adherence | 399 (98.5) | 396 (98.8) |

| Tobacco (n=365) | 170 (95.5) | 176 (94.1) |

| Diet | 401 (99.0) | 397 (99.0) |

| Physical Exercise | 400 (98.8) | 391 (97.5) |

| Alcohol Intake (n=154) | 75 (93.8) | 73 (97.3) |

| Discharge Medications | ||

| Anti Platelet1† | 395 (97.5) | 392 (97.8) |

| Anti Platelet2‡ | 317 (78.3) | 324 (80.8) |

| Dual Antiplatelets | 314 (77.5) | 324 (80.8) |

| Anticoagulant | 8 (2.0) | 4 (1.0) |

| ACE Inhibitor | 263 (64.9) | 239 (59.6) |

| ARB | 25 (6.2) | 33 (8.2) |

| Beta Blocker | 274 (67.7) | 281 (70.1) |

| Lipid Lowering | 385 (95.1) | 377 (94.0) |

Aspirin

Clopidogrel/ Prasugrel/ Ticagrelor

DISCUSSION

Baseline data indicate that the ACS population is younger as compared to Western counterparts. There is a high prevalence of risky lifestyle behavior, with prevalence rates higher than those reported in WHO PREMISE (13). A large proportion of patients had STEMI with median time from symptom onset to hospital arrival of 6.2 hours, similar to patients in the CREATE registry (14). The prescription rates of RAAS blockers, beta blockers, statins and anti-platelet agents were satisfactory at discharge.

Interventions that enlist ancillary health care providers such as pharmacists, behavioral specialists, and nursing staff can improve adherence. Clinic based intervention by a nurse practitioner in the EUROACTION cluster randomized trial in patients with known CHD showed a significant decrease in smoking and greater use of statins in the intensive care group at 12 months (15). There are limited studies even in high-income countries evaluating CHW based interventions following an acute coronary event. RCTs have evaluated interventions in a hospital setting on reducing CVD risk factors using CHWs and mobile health tools (16–18) and reported improvements in risk factors. The COACH trial (19) among 525 patients with documented cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, or hypertension evaluating a nurse practitioner/ health worker based intervention, demonstrated improved risk factors and quality of life at one year. The ProActive Heart trial (20) on 430 patients with an MI using telephone based reminders showed no change in health status compared to usual care, and reported that the cost of these interventions were high.

Our study has some strengths and limitations. This is the first study in a LMIC setting evaluating CHW based interventions in CHD with tools that were developed in-house and adapted for local settings. Trial sites were distributed across the country and comprised of different types of hospitals. Training manuals and intervention tools were developed with inputs from site staff that would use them. While the ideal design is a cluster randomized trial, we used the individual patient randomized design for logistic reasons. This may have resulted in some contamination of interventions. Being an open trial, the Hawthorne effect is a possibility, which can reduce the treatment effect. The intervention contains many components. These components are delivered as an interventional package. It is therefore not possible to assess the impact of each component on outcomes. Though we have designed the trial to avoid contamination by minimizing the chance of any contact between the CHW and patients in the control group, the possibility of some contamination occurring cannot be ruled out.

The duration of follow up is one year and this period is likely to show modest benefits of the interventions on medication and lifestyle adherence. If the interventions prove to be beneficial on these outcomes, we can assume a beneficial effect on long-term clinical end points. This study is not powered to show an effect on clinical outcomes. Future studies in this area must employ robust cluster randomized controlled designs to evaluate multi-pronged approaches combining health worker based strategies equipped with mobile health technologies with longer term follow ups to evaluate the impact of these interventions on clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgements

This project has been funded in part with federal funds from the United States National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under Contract no. HHSN268200900025C. This project has also been funded in part by the United Health group. This work has been presented at the European Society of Cardiology conference 2013, Amsterdam and published as a conference abstract in the European Heart Journal. We acknowledge all community health workers, project officers, study coordinators from the Division of Clinical Research & Training, St. John's Research Institute and database team members for helping with the conduct of the study. The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, all study analyses, the drafting and editing of the manuscript and its final contents.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dr. Deepak Y Kamath, Division of Clinical Research & Training St. John's Research Institute, Bengaluru, India..

Dr. Denis Xavier, Division of Clinical Research & Training St. John's Research Institute Opp. Koramangala BDA Complex, Koramangala, Bengaluru, India – 560034 denis@sjri.res.in Ph. No: +91-80-49466140 Fax. No: +91-80-49467090.

Dr. Rajeev Gupta, Department Internal Medicine Fortis Escorts Hospital, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India.

Dr. P.J. Devereaux, Department of Medicine Division of Cardiology & Department of Clinical Epidemiology & Biostatistics McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Dr. Alben Sigamani, Division of Clinical Research & Training St. John's Research Institute, Bengaluru, India.

Dr. Tanvir Hussain, General Internal Medicine & CVD fellow Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, United States..

Dr Sowmya Umesh, Department of Medicine St. John's Medical College & Hospital, Bengaluru, India.

Ms. Freeda Xavier, Division of Clinical Research & Training St. John's Research Institute, Bengaluru, India.

Ms. Preeti Girish, Division of Clinical Research & Training St. John's Research Institute, Bengaluru, India.

Nisha George, Statistician, Division of Clinical Research & Training St. John's Research Institute, Bengaluru, India.

Dr. Tinku Thomas, Department of Biostatistics St. John's Medical College, Bengaluru, India.

Dr. N. Chidambaram, Department of Medicine Rajah Muthiah Medical College, Annamalainagar, Tamil Nadu, India.

Dr. Rajnish Joshi, Department of Internal Medicine All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Bhopal, India.

Dr. Prem Pais, Division of Clinical Research & Training St. John's Research Institute, Bengaluru, India.

Dr. Salim Yusuf, Executive Director, Population Health Research Institute Heart & Stroke Foundation/ Marion W. Burke Chair in Cardiovascular Diseases McMaster University, Hamilton Health Sciences, Ontario, Canada..

REFERENCES

- 1.Kahn R, Robertson RM, Smith RED. The impact of prevention on reducing the burden of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2008;372:576–85. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.190186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beaglehole R, Epping-Jordan J, Patel V, Chopra M, Ebrahim S, Kidd M, et al. Improving the prevention and management of chronic disease in low-income and middle-income countries: a priority for primary health care. Lancet. 2008;372:940–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61404-X. Available from: PM:18790317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith SC, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, Braun LT, Creager MA, Franklin BA, Gibbons RJ, Grundy SM, Hiratzka LF, Jones DW, Lloyd-Jones DM, Minissian M, Mosca L, Peterson ED, Sacco RL, Spertus J, Sein JHTK. AHA/ACC secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2432–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease - Guidelines for assessment and management of cardiovascular risk. Geneva: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choudhry NK, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Lee JL, Brennan TA, Reisman L, Toscano M, Levin R, Matlin OS, Antman EMSW. Untangling the relationship between medication adherence and post-myocardial infarction outcomes. AHJ. 2014;167(1):51–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yusuf S, Islam S, Chow CK, Rangarajan S, Dagenais G, Diaz R, et al. Use of secondary prevention drugs for cardiovascular disease in the community in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (the PURE Study): a prospective epidemiological survey. The Lancet. 2011:1231–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDonald HP, Garg AX, Haynes RB. Interventions to enhance patient adherence to medication prescriptions: scientific review. JAMA. 2002;288:2868–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kripalani S, Yao X, Haynes RB. Interventions to enhance medication adherence in chronic medical conditions: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:540–50. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Auer R, Gaume J, Rodondi N, Cornuz J, Ghali WA. Efficacy of in-hospital multidimensional interventions of secondary prevention after acute coronary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2008;117:3109–17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.748095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization . Community health workers in healthcare. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.UnitedHealth National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Centres of Excellence Global response to noncommunicable disease. BMJ Br Med J. 2011;342:d3823. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24:67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendis S, Abegunde D, Yusuf S, Ebrahim S, Shaper G, Ghannem H, et al. WHO study on Prevention of REcurrences of Myocardial Infarction and StrokE (WHO-PREMISE). Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:820–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xavier D, Pais P, Devereaux PJ, Xie C, Prabhakaran D, Reddy KS, et al. Treatment and outcomes of acute coronary syndromes in India (CREATE): a prospective analysis of registry data. Lancet. 2008;371:1435–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60623-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wood D, Kotseva K, Connolly S, Jennings C, Mead A, Jones J, et al. Nurse-coordinated multidisciplinary, family-based cardiovascular disease prevention programme (EUROACTION) for patients with coronary heart disease and asymptomatic individuals at high risk of cardiovascular disease: a paired, cluster-randomised controlle. Lancet. 2008;371:1999–2012. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60868-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krieger J, Collier C, Song L, Martin D. Linking community-based blood pressure measurement to clinical care: a randomized controlled trial of outreach and tracking by community health workers. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:856–61. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.6.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krantz MJ, Coronel SM, Whitley EM, Dale R, Yost J, Estacio RO. Effectiveness of a community health worker cardiovascular risk reduction program in public health and health care settings. Am J Public Health [Internet] 2013;103:e19–27. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitley EM, Main DS, McGloin J, Hanratty R. Reaching individuals at risk for cardiovascular disease through community outreach in Colorado. Prev Med. 2011;52:84–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen JK, Dennison-Himmelfarb CR, Szanton SL, Bone L, Hill MN, Levine DM, et al. Community Outreach and Cardiovascular Health (COACH) Trial: A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Nurse Practitioner/Community Health Worker Cardiovascular Disease Risk Reduction in Urban Community Health Centers. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2011:595–602. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.961573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turkstra E, Hawkes AL, Oldenburg B, Scuffham P a. Cost-effectiveness of a coronary heart disease secondary prevention program in patients with myocardial infarction: results from a randomised controlled trial (ProActive Heart). BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013;13:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-13-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]