Abstract

Introduction

The primary tumor site is unknown prior to treatment in approximately 20% of small bowel (SBNET) and pancreatic (PNET) neuroendocrine tumors despite extensive workup. It can be difficult to discern a PNET from an SBNET on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains, and thus more focused diagnostic tests are required. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and gene expression profiling are two methods used to identify the tissue of origin from biopsied metastases.

Methods

Tissue microarrays were created from surgical specimens and stained with up to 7 antibodies used in the NET-specific IHC algorithm. Expression of 4 genes for differentiating between PNETs and SBNETs was determined by qPCR and then used in a previously validated gene expression classifier (GEC) algorithm designed to determine the primary site from gastrointestinal (GI) NET metastases.

Results

The accuracy of the IHC algorithm in identifying the primary tumor site from a set of 37 metastases was 89.1%, with only 1 incorrect call. Three other samples were indeterminate due to pan-negative staining. The GEC’s accuracy in a set of 136 metastases was 94.1%. It identified the primary tumor site in all cases where IHC failed.

Conclusion

Performing IHC, followed by GEC for indeterminate cases, accurately identifies the primary site in SBNET and PNET metastases in virtually all patients.

INTRODUCTION

The average length of time between symptom onset to diagnosis of a neuroendocrine tumor (NET) is 9.2 years.(1) Often, the first signs of this neoplastic process are liver metastases detected by CT scan. Additional workup, including EGD, colonoscopy, and chest X-ray, can rule out the lungs, stomach, duodenum, colon and rectum as primary sites, but CT may fail to detect primaries in the pancreas or small bowel when they are small or suboptimally protocoled. Although one institutional study reported that 100% of metastasized PNETs (average size 7.98 cm) could be detected by CT,(2) a proportion of tumors ≤ 2 cm will have distant metastasis (9.1%) or nodal metastases (27%) and might not be seen by CT.(3) Distinguishing from which of these sites a NET originates is important, as surgical and medical treatments are different for PNETs versus SBNETs. For example, small bowel resection is generally less morbid than pancreatic resection. Also, everolimus, sunitinib, or cytotoxic chemotherapy are all therapeutic options in PNETs, but have not been proven beneficial in SBNETs.(4)

Histologic analysis by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of a biopsy of a metastasis is usually sufficient to make the diagnosis of a NET, but is inadequate to determine the specific organ from which it originated. One method to identify the primary site of origin is IHC, which takes advantage of unique protein expression patterns in each tumor type. IHC is useful in assigning the tissue derivation from which a metastasis originated in 75 to 85% of cases.(5-7) NETs are relatively rare and may be misclassified by IHC due to a lack of agreement on which IHC stains most appropriately define these tumors. A recently developed IHC algorithm may lead to greater diagnostic efficacy to determine the primary tumor site from well-differentiated NET metastases.(8)

Gene expression profiling is another useful method for determining the primary tumor sites from metastases. This method takes advantage of unique mRNA expression patterns in different tumors, and over the past few years, a handful of classifiers have become available commercially,(5, 9) though none are marketed specifically for neuroendocrine tumors. Our group recently created a GEC designed to distinguish PNET from SBNET metastases. The expression levels quantitated for 4 genes are applied in a multi-tiered algorithm, leading to a correct diagnosis in nearly 100% of cases.(10)

As an increasing number of organ-specific therapies become available to patients, there is greater urgency to solve the clinical problem of the NET of unknown primary. The advantages of IHC in this regard are its low cost, widespread availability, and applicability to formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. However, IHC’s utility may be incompletely realized in cases of rare diseases, as it requires nuanced application of a vast array of commercially available markers. Gene expression profiling has the potential for superior diagnostic accuracy(5, 6) but is limited to laboratories with quantitative PCR capabilities and is also more expensive than IHC. These two methods are well suited to be used in a complementary fashion to detect the unknown primary site in GI NETs, but no reports exist comparing the two techniques in this context. We set out to compare NET-specific GEC and IHC algorithms designed to distinguish SBNETs from PNETs in biopsied tissue.

METHODS

Patients and Tissue Samples

This is a single institution, retrospective study. All patients were enrolled a under an Institutional Review Board-approved protocol from 2005 to 2013. Liver and lymph node metastases were collected at the time of surgery from SBNET or PNET patients. The primary tumor site was confirmed intraoperatively, and a total of 136 metastases were collected. These metastases included 97 from patients with SBNETs (38 hepatic, 59 lymph node metastases) and 39 from patients with PNETs (17 hepatic, 22 lymph node metastases). Tissues were stored at −20° C in RNAlater solution (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY).

Gene Expression Classifier

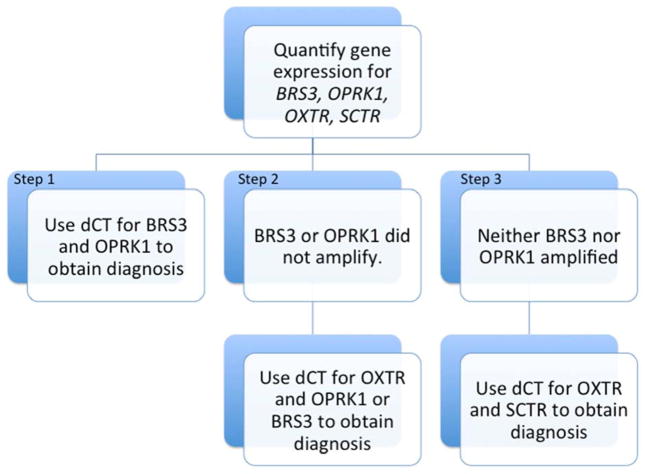

Total RNA was isolated from all 136 surgically excised metastases using the TRIzol method and reverse transcribed to cDNA (Life Technologies). The 4 genes used to distinguish SBNET from PNET primaries in the Gene Expression Classifier (GEC) are opioid receptor kappa-1 (OPRK1), secretin receptor (SCTR), bombesin-like receptor-3 (BRS3), and oxytocin receptor (OXTR). Expression levels for each of these genes were determined using quantitative PCR (qPCR). Reactions were performed in triplicate using Taqman primers and probes on the 7900 HT-Fast Analyzer platform (Life Technologies).(11) The mean expression for each gene was normalized to 2 internal control genes, polymerase (RNA) II polypeptide A (POLR2A) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), giving the CT (dCT). Each gene’s dCT was used to determine whether the metastasis originated from the pancreas or small bowel by the GEC formula as described (Figure 1).(10, 12)

Figure 1. Gene expression classifier for GI NETs of unknown origin.

Stepwise use of dCT obtained from the gene expression assays distinguishes SBNETs from PNETs in almost all cases. Most cases are resolved using only Step 1. Steps 2 or 3 need only be used if the tumor has low expression of the Step 1 genes. BRS3, bombesin-like receptor-3; OPRK1, opioid receptor kappa-1; OXTR, oxytocin receptor; SCTR, secretin receptor.(10, 12)

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue microarrays (TMAs) were constructed from formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded liver or lymph node metastases corresponding to 86 primary SBNETs and PNETs and 37 metastases. One millimeter cores of tumor were arrayed in triplicate for each sample.

IHC was performed in the Histology Research Laboratory using antibodies against caudal type homeobox 2 (CDX2), paired box gene 6 (PAX6), insulin gene enhancer binding protein Isl-1 (Islet 1), progesterone receptor (PR), prostatic acid phosphatase (PrAP), neuroendocrine secretory protein 55 (NESP55), and pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 (PDX1; Table 1). Staining was performed on 4 μm tissue sections, which were first deparaffinized, rehydrated, and subjected to heat-induced epitope retrieval in citrate buffer (pH 6). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide. After incubation with the primary antibody, the DAKO Envision Kit (Agilent Technologies, Dako, Denmark) was used for detection. Sections from colon (for CDX2), pancreas (PAX6, Islet 1, NESP55, PDX1), breast (PR), and prostate (PrAP) were used as positive controls. For negative controls, citrate buffer was substituted for the primary antibody.

Table 1.

Immunohistochemical stains used in the algorithm to distinguish SBNETs from PNETs.

| Protein | Description | GI Neuroendocrine Tumor Specificity | Antibody Clone | Vendor | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDX2 | TF active in tubal gut development and patterning; used as a (diagnostic) marker for tubal gut cancers | Small bowel (midgut), Appendix | CDX2-88 | Biogenex | 1:100 |

| PAX6 | TF active in islet development | Pancreas, Duodenum, Rectum | PAX6 | DSHB | 1:100 |

| Islet 1 | TF active in islet development | Pancreas, Duodenum, Rectum | 40.3A4 | DSHB | 1:200 |

| PrAP | Prostatic enzyme used as a marker for prostate cancer | Small bowel (midgut), Rectum | PASE/4LJ | Thermo Scientific | 1:12000 |

| PR | TF used as a marker for breast and gynecological cancers and as a predictive marker | Pancreas | 1A6 | EMD Millipore | 1:320 |

| NESP55 | Component of dense-core secretory granules | Pancreas, Duodenum, Appendix | Polyclonal | abcam | 1:2500 |

| PDX1 | TF active in islet development | Pancreas, Duodenum, Appendix, Rectum | EPR3358(2) | Epitomics | 1:4000 |

TF = transcription factor

A surgical pathologist (K.S.) constructed and analyzed all TMAs. As the tissue for the TMA is derived from a surgical paraffin block, it can potentially be identified as small bowel or pancreas by visual inspection. Thus, TMA construction and H-score assignment were not performed in a blinded fashion. Each tissue core was assessed for extent (% cells) and intensity (0, none; 1+, faint/barely perceptible; 2+, weak to moderate; 3+, strong) of staining for each of the 7 markers. These were combined into a modified H-score, which equals the sum of each intensity of staining (0-3) multiplied by the percent of cells displaying that degree of staining. H-scores range from 0-300.(13) For each case, overall H-scores for the 7 markers represent the mean of the H-scores for each of the 3 cores. The pathologist analyzing the TMAs assigned a study ID to each sample and created a data sheet that contained only the sample’s study ID and the associated H-scores for each marker.

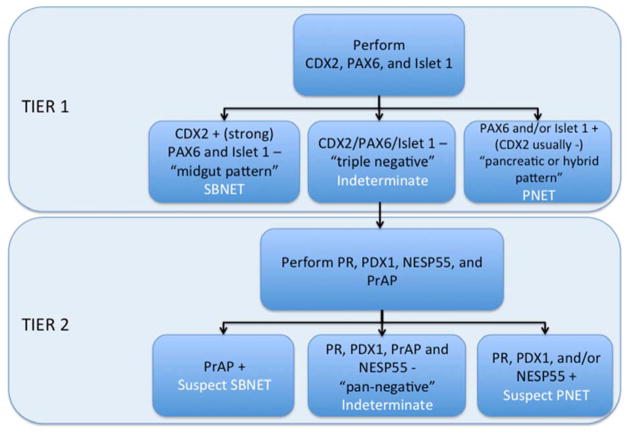

A second surgical pathologist (A.B.), blind to the primary site and any additional patient data, used the H-score results to assign the primary site to either the pancreas or small bowel. A two-tiered algorithm was used (Figure 2), with the first-tier markers CDX2, PAX6, and Islet 1, representing the fewest number required to distinguish PNETs from SBNETs. Tumors with strong, diffuse CDX2 expression (H-score ≥50, but typically 200-300) accompanied by absent expression of PAX6 and Islet 1 were classified as SBNETs (“midgut pattern”). Cases with any expression (typically in the 100-300 H-score range) of PAX6 and/or Islet 1 were classified as PNETs; these tumors were usually CDX2-negative (“pancreatic pattern”), though some co-expressed CDX2 (“hybrid pattern”). For tumors with weak to no CDX2 expression (H-scores <50, though usually 0) and no PAX6 or Islet 1 expression (“triple-negative pattern”), second-tier markers were relied upon to assign the primary site. In this context, cases with any PR, NESP55, or PDX1 staining were classified as PNETs, while those with PrAP expression were classified as SBNETs. For tumors negative for all 7 markers (“pan-negative pattern”), the site of origin was considered indeterminate.

Figure 2. IHC algorithm for GI NETs of unknown origin.

First tier stains: CDX2, caudal type homeobox 2; PAX6, paired box gene 6; Islet 1, insulin gene enhancer binding protein Isl-1. Second tier stains: PR, progesterone receptor; PDX1, pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1; NESP55, neuroendocrine secretory protein 55; PrAP, prostatic acid phosphatase.

RESULTS

Gene Expression Classifier

All 136 metastases were analyzed using the GEC. As long as a dCT for BRS3 and OPRK1 are available for a sample, the GEC will assign either small bowel or pancreas as the tissue of origin. If one of these genes does not amplify (meaning expression is undetectable), the GEC uses the dCT of OXTR with the gene that did amplify (of BRS3 or OPRK1) to classify the metastasis. In cases where neither BRS3 nor OPRK1 amplifies, the dCT of OXTR and SCTR are used to distinguish between pancreas and small bowel tissue. Overall, the GEC correctly classified 128 (94.1%) of the 136 metastases. The GEC was more successful classifying metastases of small bowel origin, and assigning 94 of 97 (96.9%) correctly. Of the 39 PNET metastases tested, 34 (87.2%) were correctly assigned (Table 2).(12)

Table 2.

Gene expression classifier results in 136 metastases.(12)

| SBNET metastases (n = 97) | PNET metastases (n = 39) | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall correct | 94 (96.9%) | 34 (87.2%) |

| Correct using 1st step* of algorithm only | 88 (93.6%) | 29 (85.3%) |

| Correct, but requiring 2nd† or 3rd‡ step of algorithm | 6 (6.3%) | 5 (14.7%) |

| Incorrect | 3 (3.1%) | 5 (12.8%) |

| Indeterminate | 0 | 0 |

dCT for BRS3 and OPRK1

dCT for OXTR and BRS3 or OPRK1

dCT for OXTR and SCTR

Regardless of which step of the algorithm assigns the primary site, if dCTs are entered for a set of genes, the formula will output either SBNET or PNET. It will not return an indeterminate result. Incorrectly assigned metastases display gene expression patterns consistent with the other primary type,(14) and the GEC therefore does not indicate which primary site assignments might be incorrect, but rather makes all calls with equal confidence.

Immunohistochemistry

IHC was performed on a group of 123 SBNETs and PNETs: 86 primaries and 37 metastases. This method correctly classified 83 of 86 (96.5%) primary tumors, including all 41 (100%) PNETs and 42 of 45 (93.3%) SBNETs (Table 3). For the primary PNETs, 38 were classified by the first tier of the algorithm, with 34 “pancreatic pattern” and 4 “hybrid pattern” tumors. Three tumors were “triple negative” but were correctly classified based on expression of PDX1 and/or NESP55. For the SBNET primaries, 41 were correctly classified based on “midgut-pattern” staining. There were 4 “triple-negative” tumors. One was correctly classified based on expression of the second-tier marker PrAP, one was incorrectly classified as PNET based on weak PDX1 expression, and 2 were “pan-negative” and thus considered indeterminate.

Table 3.

Immunohistochemistry results in 86 primary and 37 metastatic SBNETs and PNETs

| SBNET primaries (n = 45) | PNET primaries (n = 41) | SBNET metastases (n = 27) | PNET metastases (n = 10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall correct | 42 (93.3%) | 41 (100%) | 23 (85.2%) | 10 (100%) |

| Correct using 1st tier stains only* | 41 (97.6%) | 38 (92.7%) | 22 (95.7%) | 8 (80.0%) |

| Correct, but requiring 2nd tier stains† | 1 (2.4%) | 3 (7.3%) | 1 (4.3%) | 2 (20.0%) |

| Incorrect | 1 (2.2%) | 0 | 1 (3.7%) | 0 |

| Indeterminate‡ | 2 (4.4%) | 0 | 3 (11.1%) | 0 |

1st tier stains: CDX2, PAX6, Islet 1

2nd tier stains: PR, NESP55, PDX1, and PrAP

Indeterminate samples are negative for all stains.

Thirty-three of 37 (89.1%) metastases were classified correctly. Again, IHC was 100% accurate in the PNETs (10 of 10). Eight of these tumors demonstrated “pancreatic-pattern” staining, while the other 2 were initially “triple negative.” These were correctly assigned based on PR expression in one and NESP55 and PDX1 expression in the other. Twenty-three of 27 (85.1%) SBNET metastases were classified correctly. Twenty-two showed “midgut-pattern” staining; 1 additional case was correctly classified based on PrAP expression. One case was incorrectly classified based on strong PR staining in the face of weak CDX2 staining (H-score of 33.3). The other 3 cases were “pan-negative” and classified as indeterminate.

Comparison of GEC vs. IHC in a set of common NET metastases

The NET-specific GEC and IHC were tested head-to-head in a subset of 27 liver and lymph node metastases (derived from 24 SBNETs and 3 PNETs) where there were data from both methods. Fifteen of the 27 samples were taken from liver metastases and 12 from nodal tissue. The individuals analyzing the GEC and IHC results were blinded to the tissue type from which the metastasis originated.

The GEC correctly identified the primary tumor site in 26 of 27 cases (96.2%). The single misclassified case was a liver metastasis originating from the small bowel that had been incorrectly assigned as pancreas. This sample was correctly classified by IHC, as it stained strongly for CDX2. IHC assigned 23 of 27 (85.2%) metastases correctly. Of the 4 missed calls, 1 was incorrectly called a PNET when it originated from the small bowel, and the other 3 were considered indeterminate as they were “pan-negative.” All 3 indeterminate cases originated from the small bowel and were correctly classified by the GEC.

DISCUSSION

The primary site of metastatic NETs may go undetected in up to 20% of cases, despite extensive work-up including imaging and endoscopy.(2) Identification of the primary tumor site allows for better surgical planning and use of targeted medical treatments. Resection of the primary, even in the presence of hepatic metastases, translates into improved overall survival.(15) Diagnosis of the primary site relies on biopsies of metastases, which in the case of PNETs and SBNETs, is most frequently obtained from the liver or lymph nodes. Percutaneous biopsies rarely result in much more than a few square millimeters of tissue, thus a good diagnostic method should require only small amounts of tissue. Ideally, the method used to evaluate the tissue should also be low cost, easy to execute and interpret, and be accurate.

IHC has been the most reliable and widely utilized method for determining the primary site from metastases for many years. Reports on its accuracy for assigning the tissue of origin in unknown primary tumors range from 75 to 85%.(5-7) This is lower than the rate in our study, explained by the fact that previous studies using IHC were in metastases that could have originated from more than 20 different tumor types, making the choice of markers difficult, even when performed by very experienced pathologists. In a more focused context, IHC performs with higher accuracy, is extremely low in cost, and requires very little tissue.

Gene expression profiling of cancers of unknown origin has become more popular in recent years, although only 2 tests are currently commercially available. These classifiers have consistently claimed greater accuracy in identifying cancer types (80 to 90%) when compared to IHC,(5, 6) but suffer from high cost and require the shipment of precious tissue to commercial labs. Attempting to replicate the type of gene expression analysis used by these commercial profilers would be difficult for most research labs, since these tests amplify more than 90 and up to 2000 genes for every sample. One of the commercially available tests was recently examined in a group of 75 NETs and correctly identified the tumors as NETs in 99% of cases. It assigned the correct NET subtype in 95% of cases. For instance, it will identify a NET as ‘GI’, but does not specify from which portion of the alimentary tract the tumor derives (e.g. duodenum, jejunoileum, gastric or colorectal).(9) While this profiler performed well in NETs, it is inefficient if the diagnosis of a NET is already suspected, as the entire panel of 92 genes is amplified for every sample, even though only a small subset of the genes tested actually contribute to NET identification.

Our group previously designed and validated a GEC to distinguish PNETs from SBNETs in cases where a GI NET is suspected and other NET sites (lung, stomach, duodenum, colon, rectum) have been ruled out. This GEC performed with 94% overall accuracy, and uses at most 4 genes (plus 2 controls) to distinguish between potential primary sites.(10, 12) This more focused approach means that it requires less tissue, fewer expensive reagents, and less interpretation to arrive at a diagnosis than other gene profilers. A limitation of the GEC is that it is optimally performed using tissue preserved in RNAlater or flash frozen immediately after collection, and requires expertise that may only be available in well-developed Molecular Pathology or research laboratories.

This is the first study comparing the accuracy and utility of IHC and GEC algorithms specifically designed to identify the primary site from metastases of suspected GI NETs. Both methods had high accuracy, although each performed best in a particular subtype of NET. The IHC algorithm was best at identifying PNETs, and did so with 100% accuracy. This method’s relative difficulty with SBNETs occurred most frequently when metastases failed to stain with any of the first or second tier markers (“pan-negative”), resulting in an indeterminate classification. Notably, of all of the NETs tested, only SBNETs displayed this “pan-negative” staining pattern. Going forward, this pattern could be used to suggest a small bowel primary. Doing so would increase the IHC algorithm’s accuracy in SBNET metastases to 96% and its overall accuracy in metastases to 97%. Regardless of whether pan-negative specimens are assumed to be SBNETs, the weak or absent staining in indeterminate metastases readily identifies difficult-to-classify specimens, which could benefit from a complementary classification method. The GEC performed best in SBNET metastases with an accuracy of 97%, but its accuracy decreased to 87% in PNET metastases. In the majority of cases, it was able to identify these primary sites using the expression of only two genes, BRS3 and OPRK1. Interestingly, in all cases where a metastasis was incorrectly classified by either IHC or the GEC, it was correctly classified by the other method.

One weakness of the study was that the IHC algorithm was tested on fewer metastases than the GEC. The IHC algorithm was designed and tested on tissue microarrays that were constructed over a 2-year period from patients that were operated upon during the early years of this series. These TMAs were constructed with an emphasis on inclusion of primary tumors, and not as many metastases were included. Future studies will further evaluate the entire group of metastases using this IHC panel, but these additional TMAs will take some time to produce.

The best use of these two GI NET-specific methods is in a sequential, complementary fashion. IHC is inexpensive, familiar, and available at most surgical centers. We propose our IHC algorithm as an excellent first-choice method when facing a NET of unknown primary site. In the rare instances in which the IHC staining pattern is weak or indeterminate, this indicates a difficult-to-classify metastasis in which a complementary diagnostic test would be helpful. Our GEC is well-suited as this next-line test, as it requires only a small number of genes per sample, demonstrates high overall accuracy, and performs best in SBNETs, the site most commonly indeterminate by IHC. By solving the problem of knowing where the primary NET originated, patients can be correctly assigned to receive targeted therapies proven to be useful for these sites, or assigned to appropriate clinical trials. Implementing this simple and practical approach as outlined should help to eliminate the dilemma of the unknown primary in all but the most difficult cases.

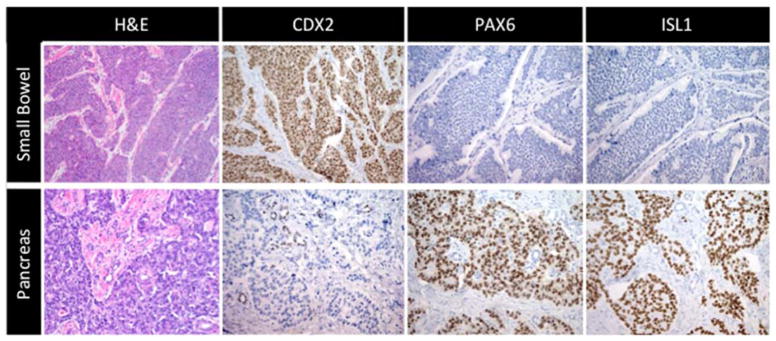

Figure 3. IHC expression patterns for SBNETs and PNETs.

IHC results for H&E, and first-tier markers CDX2, PAX6, and ISL1. Top panels represent typical results found in SBNETs, and lower panels in PNETs.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH 5T32#CA148062-04 (JEM, SKS).

Monoclonal antibodies to PAX6 and Islet 1 (clone 40.3A4), developed by Atsushi Kawakami (Tokyo Institute of Technology) and Thomas M. Jessell/Susan Brenner-Morton (Columbia University), respectively, were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, created by the NICHD of the NIH and maintained at The University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City, IA 52242

Footnotes

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest

This work was presented at the 2014 meeting of the American Association of Endocrine Surgeons in Boston, MA.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Vinik AI, Silva MP, Woltering EA, Go VLW, Warner R, Caplin M. Biochemical Testing for Neuroendocrine Tumors. Pancreas. 2009;38:876–89. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181bc0e77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang SC, Parekh JR, Zuraek MB, Venook AP, Bergsland EK, Warren RS, et al. Identification of unknown primary tumors in patients with neuroendocrine liver metastases. Arch Surg. 2010;145:276–80. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuo EJ, Salem RR. Population-level analysis of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors 2 cm or less in size. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:2815–21. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao JC, Shah MH, Ito T, Lombard Bohas C, Wolin EM, Van Cutsem E, et al. Everolimus of Advanced Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. NEJM. 2011;364:514–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Handorf CR, Kulkarni A, Grenert JP, Weiss LM, Rogers WM, Kim OS, et al. A Multicenter Study Directly Comparing the Diagnostic Accuracy of Gene Expression Profiling and Immunohistochemistry for Primary Site Identification in Metastatic Tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1067–75. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31828309c4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiss LM, Chu P, Schroeder BE, Singh V, Zhang Y, Erlander MG, et al. Blinded comparator study of immunohistochemical analysis versus a 92-gene cancer classifier in the diagnosis of the primary site in metastatic tumors. JMD. 2013;15:263–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greco FA, Lennington WJ, Spigel DR, Hainsworth JD. Molecular profiling diagnosis in unknown primary cancer: accuracy and ability to complement standard pathology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:782–90. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellizzi AM. Assigning Site of Origin in Metastatic Neuroendocrine Neoplasms: A Clinically Significant Application of Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry. Adv Anat Pathol. 2013;20:285–314. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3182a2dc67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerr SE, Schnabel CA, Sullivan PS, Zhang Y, Huang VJ, Erlander MG, et al. A 92-gene cancer classifier predicts the site of origin for neuroendocrine tumors. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:44–54. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherman SK, Carr JC, Wang D, O’Dorisio MS, O’Dorisio TM, Howe JR. Gene Expression in Neuroendocrine Tumor Liver Metastases Accurately Distinguishes between Pancreas and Small Bowel Primary Tumors. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217:S129. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherman SK, Carr JC, Wang D, O’Dorisio MS, O’Dorisio TM, Howe JR. Gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor (GIPR) is a promising target for imaging and therapy in neuroendocrine tumors. Surgery. 2013;154:1206–13. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.04.052. discussion 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherman SK, Maxwell JE, Carr JC, Wang D, Bellizzi AM, O’Dorisio MS, et al. Gene expression accurately distinguishes liver metastases of small bowel and pancreas neuroendocrine tumors. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10585-014-9681-2. Submitted to Modern Pathology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Budwit-Novotny DA, McCarty KS, Cox EB, Soper JT, Mutch DG, Creasman WT, et al. Immunohistochemical analyses of estrogen receptor in endometrial adenocarcinoma using a monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res. 1986;46:5419–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carr JC, Sherman SK, Wang D, O’Dorisio MS, O’Dorisio TM, Howe JR. Overexpression of Membrane Proteins in Primary and Metastatic Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors. Annals of surgical oncology. 2013 doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3318-6. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Givi B, Pommier SJ, Thompson AK, Diggs BS, Pommier RF. Operative resection of primary carcinoid neoplasms in patients with liver metastases yields significantly better survival. Surgery. 2006;140:891–7. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2006.07.033. discussion 7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]