SUMMARY

Translational control of mRNAs allows for rapid and selective changes in synaptic protein expression, changes that are required for long-lasting plasticity and memory formation in the brain. Fragile X Related Protein 1 (FXR1P) is an RNA-binding protein that controls mRNA translation in non-neuronal cells and co-localizes with translational machinery in neurons. However, its neuronal mRNA targets and role in the brain are unknown. Here, we demonstrate that removal of FXR1P from the forebrain of postnatal mice selectively enhances long-term storage of spatial memories, hippocampal late-phase LTP (L-LTP) and de novo GluA2 synthesis. Furthermore, FXR1P binds specifically to the 5’UTR of GluA2 mRNA to repress translation and limit the amount of GluA2 incorporated at potentiated synapses. This study uncovers a new mechanism for regulating long-lasting synaptic plasticity and spatial memory formation and reveals an unexpected divergent role of FXR1P among Fragile X proteins in brain plasticity.

Keywords: synapse, plasticity, protein synthesis, mRNA translation, GluA2, Fragile X Proteins, L-LTP, memory, FXR1P, FMRP, FXR2P

INTRODUCTION

Memories are thought to be stored as long-lasting changes to the size, strength and number of synapses in neuronal networks (Govindarajan et al., 2006; Kessels and Malinow, 2009). These changes rely on new protein synthesis that occurs locally from translational machinery found in dendrites and at synapses (Schuman et al., 2006). This local protein synthesis is regulated through a combination of general translational control mechanisms, which act on all mRNAs, and gene-specific mechanisms, which act on specific subsets of mRNAs. Together, these mechanisms ensure that the correct proteins are synthesized in response to specific patterns of synaptic activity (Costa-Mattioli et al., 2009). Although several studies have shown that knocking-out components of the general translational control pathway alters, and even enhances, synaptic plasticity and memory (Costa-Mattioli et al., 2005, 2007; Kelleher et al., 2004), further elucidation of the role of gene-specific mechanisms in these processes is required.

In the brain, gene-specific mRNA translational control is achieved by a diverse array of neuronal RNA-binding proteins whose roles in long-term plasticity and memory storage remain largely unexplored (Doyle and Kiebler, 2011; Elvira et al., 2006; Kanai et al., 2004). One of these RNA-binding proteins, Fragile X Related Protein 1 (FXR1P), is related to Fragile X Related Protein 2 (FXR2P) and Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein (FMRP), two proteins known to function in synaptic plasticity and memory. While FXR1P can regulate protein synthesis in non-neuronal cells (Garnon et al., 2005; Vasudevan and Steitz, 2007), its role in mRNA translation and synaptic plasticity in neurons is unknown, largely related to the fact that complete loss of FXR1P in mice results in perinatal lethality (Mientjes et al., 2004). Our recent discovery that FXR1P co-localizes with translation machinery in dendrites and near a subset of dendritic spines (Cook et al., 2011) prompted us to investigate its function in brain development, plasticity and synaptic protein expression and to compare its role to FXR2P and FMRP.

To address the in vivo role of FXR1P in the brain, we conditionally deleted FXR1P from the postnatal forebrain of mice and found that loss of FXR1P specifically enhances hippocampal protein synthesis-dependent L-LTP, spatial memory, and expression of the AMPA receptor subunit GluA2. Furthermore, we show that FXR1P binds to GluA2 mRNA and represses its translation through a conserved GU-rich element in its 5'UTR. Interestingly, the ability of FXR1P to repress GluA2 synthesis is unique to FXR1P and is not a property of FXR2P or FMRP. Ultimately, the loss of FXR1P-mediated GluA2 repression heightens activity-dependent synaptic delivery of GluA2, increasing its incorporation at potentiated synapses. Thus, FXR1P has a critical role in limiting synaptic plasticity and memory storage in the brain, and has an unexpected divergent function among Fragile X proteins in these processes.

RESULTS

Characterization of FXR1P conditional knockout mice

To investigate the role of FXR1P in the brain, we genetically removed FXR1P from excitatory neurons in the forebrain of early postnatal mice using a floxed Fxr1 line combined with the αCaMKII-Cre T29-1 transgenic line (Sonner et al., 2005; Tsien et al., 1996). Using a fluorescent reporter line, we found that Cre-mediated recombination in CA1 cells started around postnatal day 12 and was nearly complete by postnatal day 60 (Figure S1A). Recombination was not seen in cerebellar and midbrain regions as reported (Sonner et al., 2005).

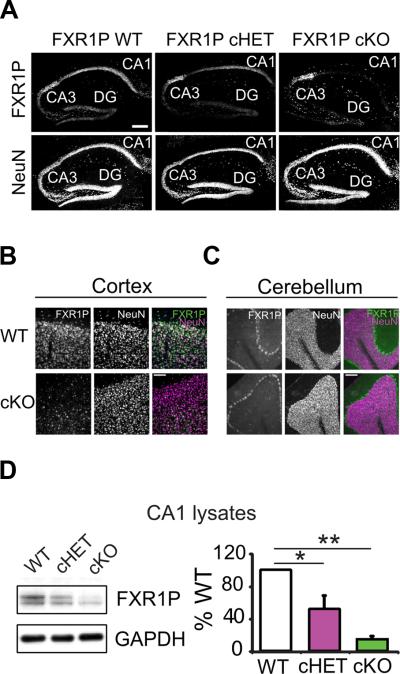

To verify Cre-mediated loss of FXR1P from CA1 cells, we labeled hippocampal sections from adult wild type (WT), FXR1P conditional heterozygous (cHET) and FXR1P conditional knockout (cKO) mice with FXR1P and NeuN antibodies. This revealed that FXR1P was lost from the majority of CA1 cells (Figure 1A). As expected, FXR1P was eliminated from many neurons in cortex, but maintained in cerebellar Purkinje cells (Figure 1B-C). Using protein lysates from area CA1, we found that FXR1P levels were reduced to 52% (cHET) and 15% (cKO) of WT levels (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Characterization of FXR1P cKO mice.

A. Hippocampal sections taken from postnatal day 60 WT, cHET and cKO mice labeled for FXR1P and NeuN. FXR1P is lost from CA1 cells in cHET and cKO mice (n=3 mice/genotype). Scale bar=200μm. B, C. FXR1P is lost from cortical neurons (B), but not cerebellar Purkinje cells (C). Scale bar=100μm. D. Western blots of CA1 lysates from WT, cHET and cKO mice. FXR1P is reduced in the cHET and cKO mice (one-way ANOVA, F(2, 6) =16.66, p=0.004, Tukey HSD post-hoc, p<0.05; 3 mice/genotype from 3 litters). Error bars show standard error. **p≤0.01 *p≤0.05. See also Figure S1.

Analysis of cKO mice showed that hippocampal anatomy was unperturbed by the loss of FXR1P. This was shown by labeling for neurons (NeuN) (Figure 1A), dendrites (MAP2), ribosomes (P0) and astrocytes (GFAP) (Figure S1B). No changes in these markers were observed, indicating that loss of FXR1P did not change overall cell morphology or organization. To determine if synapse density and morphology were changed, we labelled CA1 cells with DiI and analyzed spine density, size and shape in adult mice. This revealed that loss of FXR1P caused a 15% reduction in spine density and an 8% decrease in spine length, without changing head diameter or shape (Figure S1C-G). Thus, loss of FXR1P reduces spine density and length.

FXR1P cKO mice show enhanced long-term memory storage

To determine if loss of FXR1P alters behavior, we tested cKO mice on paradigms that assess basic motor/sensory function, anxiety, and learning and memory. cKO mice showed no deficits in motor/sensory function or anxiety, as tested using the open field test and light-dark box (Figure S2A-B). Both genotypes also performed equally well on strong and weak contextual fear conditioning paradigms (Figure S2C and not shown), and on the object recognition test (a test of working memory) (Figure S2D). These results suggest that basic motor/sensory function, anxiety, contextual fear memory and working memory are intact in cKO mice.

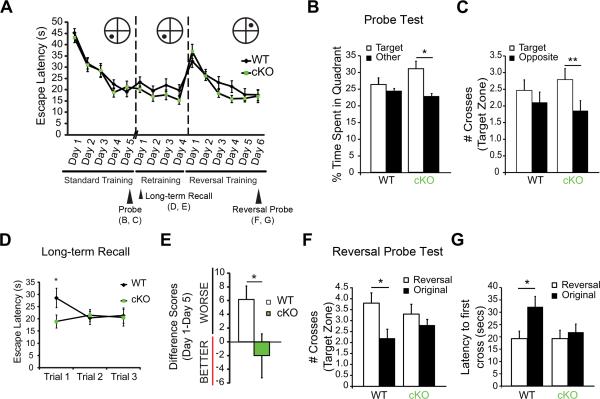

To test for a more specific role of FXR1P in spatial learning/memory, we used a modified Morris water maze paradigm that assesses learning, long-term memory storage, and behavioral flexibility (Figure 2A). WT and cKO mice performed equally well during the initial 5 training days (Figure 2A). However, during a probe trial administered 4 hours after the last training session, cKO mice spent more time in the target quadrant and showed a greater number of crosses of the target platform location, suggesting that they had acquired a better spatial memory of the platform location as compared to WT mice (Figure 2B-C).

Figure 2. Loss of FXR1P enhances long-term memory and behavioral flexibility.

A. cKO mice perform similarly to WT mice in the learning trials of Morris water maze training (two-way mixed ANOVA (Genotype, Days), main effect Days, F(4, 208) =46.52, p<0.001), retraining (two-way mixed ANOVA (Genotype, Days), p>0.05) and reversal training (two-way mixed ANOVA (Genotype, Days), main effect Days, F(5, 180) =24.73, p<0.001). B, C. cKO mice perform better than WT mice on the probe test 4 hours after the third trial on training day 5. cKO mice spend more time in the target quadrant vs. the average of all other quadrants (two-tailed paired t-test, t(27)=2.73, p=0.01), whereas WT mice do not (two-tailed paired t-test, t(27)=0.6784, p=0.50) (B). cKO mice cross the platform in the target zone more frequently than the platform in the opposite zone (two-tailed paired t-test, t(27)=2.79, p=0.01), whereas WT mice do not (two-tailed paired t-test, t(27)=0.79, p=0.44) (C). D, E. cKO mice have enhanced ability to recall long-term memories 9 days after the original 5 training days. cKO are faster at locating the hidden platform on the first trial of the first day of re-training (two-tailed unpaired t-test, t(33)=2.01, p=0.05) (D). cKO mice performed equally well on the first day of retraining (average of three trials) compared to their performance on the last day of the original learning phase (average of 3 trials), whereas WT mice are slower (two-tailed unpaired t-test, t(31)=2.19, p=0.04) (E). F, G. cKO mice do not show a preference towards the new platform location in the reversal probe test. WT mice cross the new platform location more times than the old platform location during the probe test (two-tailed paired t-test, t(19)=2.49, p=0.02), whereas cKO do not (two-tailed paired t-test, t(19)=0.92, p=0.37) (F). WT mice display a shorter latency to first cross for the new platform location vs. the old platform location (two-tailed paired t-test, t(19)=2.40, p=0.03), whereas cKO mice show equivalent latency to first cross of the reversal and original platform locations (two-tailed paired t-test, t(19)=0.57, p=0.57) (G). Error bars show standard error. *p≤0.05, **p≤0.01. See also Figure S2.

Consistent with improved performance of cKO mice in the probe test, when mice were re-tested nine days later, cKO mice were faster than WT mice at locating the platform. This improved recall was demonstrated both by a reduction in escape latency during the first trial of re-training day 1 (Figure 2D) and by comparing differences in average performance of the mice on day 1 of the re-training versus day 5 of the original training (Figure 2E). Thus, cKO mice showed an enhanced ability to recall spatial memories.

Since disruption of general protein synthesis can alter behavioral flexibility in spatial memory tasks (Hoeffer et al., 2008), we tested if cKO mice can learn and remember a new platform location. Mice from both genotypes similarly learned the location of the new platform (Figure 2A). However, unlike WT mice, cKO mice failed to shift their preference to the new platform location during the reversal probe test (Figure 2F). Measuring the average latency to the first platform crossing further revealed that cKO mice showed equal latency to first cross of the original and reversal platform locations, unlike WT mice that immediately targeted the location of the reversal platform (Figure 2G). Interestingly, in contrast to other mouse mutants with disruptions in mRNA translation machinery, cKO mice did not display perseverative behavior during the learning phases or probe test (Hoeffer et al., 2008; Trinh et al., 2012), but in fact showed equal preference for the original and reversal platform locations. Together, the results indicate that FXR1P cKO mice have enhanced spatial memory without perseverative behaviors.

FXR1P cKO mice display a specific enhancement in late-phase LTP (L-LTP)

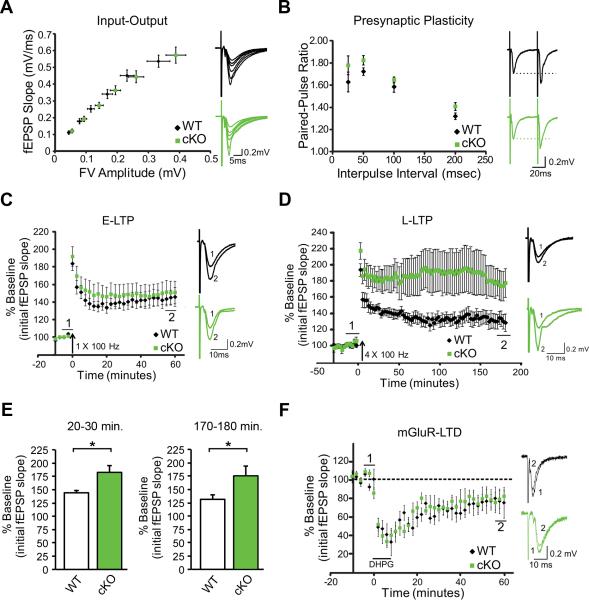

Alterations in spatial memory are associated with changes in the function and plasticity of excitatory synapses in hippocampal area CA1. To determine if cKO mice have altered synaptic function and plasticity that may affect learning and memory processes, we conducted a series of electrophysiology experiments. By recording field potentials in the stratum radiatum, we found no differences in the input-output relationship or paired-pulse ratio (a measure of presynaptic release probability (Dobrunz and Stevens, 1997) between genotypes (Figure 3A-B), indicating that cKO mice have normal basal synaptic strength and short-term plasticity, respectively.

Figure 3. FXR1P cKO mice show a specific enhancement in L-LTP.

A. Left Input-output curve showing synaptic responses upon increasing stimulation intensities for WT and cKO mice. Right Representative traces from WT and cKO mice. B. Left Paired-pulse facilitation (PPF) is normal in cKO mice (two-way mixed ANOVA, Genotype x Inter-stimulus interval, F(3,39) =0.44, p=0.73). Right Representative traces at a 50ms interval. C. Left E-LTP induced by a single train of high frequency stimulation (HFS: 1×100 Hz) is normal in cKO mice (n=8 mice, 9 slices, from 4 litters)(analysis at 50-60 minutes post-HFS, two-tailed unpaired t-test, t(15)=-0.38, p=0.71). Right Traces representing (1) 5 minutes of baseline immediately preceding HFS and (2) the period from 55-60 minutes post-LTP. D. Left Four trains of HFS delivered at 20s intervals (HFS: 4×100Hz) produce higher levels of potentiation in cKO animals (n=7 mice, 7 slices, from 5 litters) than WT animals. E. L-LTP, measured at 20-30 minutes and 170-180 minutes post-HFS, is greater in cKO (two-tailed unpaired t-tests, t(7)=2.65, p=0.03 and t(9)=2.24, p=0.05 respectively). Right Traces representing (1) 5 minutes of baseline immediately preceding HFS and (2) the period from 175-180 minutes post-LTP. F. Left mGluR-dependent LTD is unchanged in cKO mice (two-tailed, unpaired two-sample t-test, p=0.86). Right Traces representing (1) 5 minutes of baseline immediately preceding bath application of DHPG (100μM, 7-8 min) and (2) the period from 55-60 minutes post-DHPG administration. Error bars show standard error. Traces show an average of approximately 5-10 sweeps.

We next tested cKO slices for their ability to establish and maintain both protein-synthesis independent (E-LTP) and protein synthesis-dependent forms of synaptic plasticity (L-LTP, mGluR-LTD) (Kelleher et al., 2004). E-LTP was induced in WT and cKO slices using a single train of high frequency stimulation (HFS; 1×100 Hz). We found that E-LTP was similar in both genotypes (Figure 3C). However, upon L-LTP induction by delivering four trains of HFS separated by a 20s interval (4×100 Hz) (Scharf et al., 2002), we found that L-LTP was increased at both 20-30 minutes and 3 hours post-HFS in the cKO (Figure 3D-E). To test if the loss of FXR1P has a general effect on protein synthesis-dependent long-term plasticity, we tested for DHPG-induced mGluR-LTD (Huber et al., 2002). However, cKO mice showed normal mGluR-LTD (Figure 3F). Thus, loss of FXR1P specifically enhanced L-LTP, a form of plasticity dependent on new protein synthesis, without perturbing E-LTP or mGluR-dependent LTD.

Increased translation of GluA2 in FXR1P cKO mice

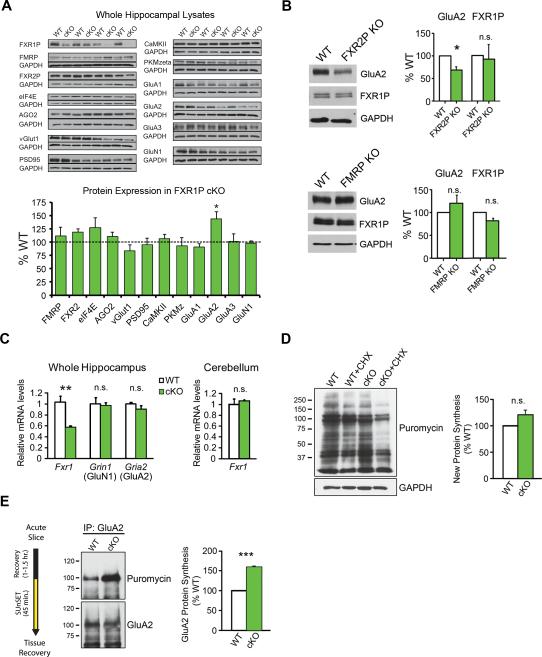

Since FXR1P is detected in polyribosome fractions in mouse brain and localized with translation machinery at or near spines in neurons (Cook et al., 2011) (Figure S3), we screened for changes in expression of molecules involved in protein translation and synaptic development/function in cKO mice. Importantly, probing hippocampal lysates showed that loss of FXR1P did not affect the levels of its paralogs FMRP or FXR2P (Figure 4A). Consistent with immunolabeling for ribosomal protein P0 (Figure S1B), we also did not see changes in expression of eIF4E, a cap-binding subunit of the eIF4F complex that recruits mRNA to the ribosome (Hershey et al., 2012), or Argonaute 2 (AGO2), a component of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). Neither Talin 2 nor desmoplakin, which are known to be altered in cardiac tissue of full FXR1P KO mice, were changed (Figure S4) (Whitman et al., 2011). Blotting for vGlut1, PSD95, αCaMKII, and PKMzeta showed that levels of these synaptic proteins were also unaltered in cKO mice (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Enhanced GluA2 translation in FXR1P cKO mice.

A. Top Analysis of Fragile X family proteins, molecules involved in protein synthesis, and synaptic proteins in WT and cKO mice (four pairs of animals). Most proteins are similarly expressed in both genotypes (two-tailed one-sample t-tests, p>0.05) with the exception of GluA2 (two-tailed one-sample t-test, p=0.02). Each blot was run 2-3X and values averaged. B. Top Blots of hippocampal lysates from WT and FXR2P KO mice showing levels of GluA2, FXR1P, and GAPDH. GluA2 is reduced (two-tailed, one-sample t-test, p=0.05; n=3 WT/3 FXR2P KO mice) and FXR1P is unchanged in FXR2P KO mice (two-tailed, one-sample t-test, p=0.26; n=3 WT/3 KO mice). Bottom Blots of hippocampal lysates from WT and FMRP KO mice showing levels of GluA2, FXR1P, and GAPDH. GluA2 and FXR1P are unchanged in FMRP KO mice (two-tailed, one-sample t-test, p>0.05; 3 WT/3 FMRP KO mice). C. qRT-PCR shows that Fxr1 mRNA levels are reduced in hippocampal lysates from FXR1P cKO mice (two-tailed, unpaired two-sample t-test, p=0.005; n=3 WT/4 cKO mice from 3 litters). The mRNA levels of Gria2 (GluA2) and Grin1 (GluN1) are unchanged (two-tailed, unpaired two-sample t-tests, p>0.05; n=3 WT/4 cKO mice). Fxr1 mRNA levels are unaltered in the cKO cerebellum (two-tailed, unpaired two-sample t-test, p>0.05; n=3 WT/3 cKO mice from 3 litters). D. Puromycin-labeled lysates from WT and cKO mice in the presence or absence of cycloheximide (CHX). No differences in overall puromycin labeling are detected between genotypes (p>0.05; 3 WT/3 cKO mice). E. IP for GluA2 shows increased puromycin-labeled GluA2 in slices from cKO mice, indicating enhanced GluA2 translation (p=0.002; 3 WT/3 cKO mice). Unless otherwise stated, statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed, one-sample t-tests. Error bars show standard error. ***p≤0.001, **p≤0.01, *p≤0.05, n.s.=not significant. See also Figures S3 and S4.

Intriguingly, loss of FXR1P resulted in a significant increase in expression of the AMPAR subunit GluA2. This increase was specific for GluA2 as no changes in the levels of GluA1, GluA3, or the NMDAR subunit GluN1 were found (Figure 4A). To determine if the FXR1P paralogs, FXR2P and FMRP, regulate GluA2 in a similar manner, we probed hippocampal lysates from FXR2P and FMRP KO mice. Unexpectedly, we observed a decrease in GluA2 in FXR2P KO mice that was not due to a compensatory change in FXR1P expression (Figure 4B). No alterations in GluA2 or FXR1P were detected in hippocampal lysates from FMRP KO mice (Figure 4B). These findings show that FXR1P reduces expression of GluA2 and indicates an intriguing divergence in the regulation of GluA2 by Fragile X-related proteins.

To determine if GluA2 upregulation in FXR1P cKO mice was due to a change in transcription/stability of GluA2 mRNA, we quantified GluA2 mRNA (Gria2) levels using real-time quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). As expected, Fxr1 mRNA levels were reduced by 50% in the hippocampus of cKO mice, but not the cerebellum, while equivalent levels of Gria2 (GluA2) and Grin1 (GluN1) mRNAs in cKO and WT mice were found (Figure 4C). This suggests that the elevation in GluA2 protein expression was not due to an increase in GluA2 mRNA transcription or stability.

To investigate if the increase in GluA2 in cKO mice was due to increased mRNA translation we used the SUnSET method (Schmidt et al., 2009). This method quantifies newly synthesized proteins by tagging them with puromycin. By quantifying total puromycin incorporation over a period of 45 minutes, we found no significant difference in global protein synthesis between genotypes (Figure 4D). However, immunoprecipitation (IP) of GluA2 and blotting for puromycin demonstrated a 59% increase in newly synthesized GluA2 in cKO mice (Figure 4E). This increase in GluA2 translation in cKO mice, without a concomitant change in GluA2 mRNA abundance, indicates that FXR1P represses (directly or indirectly) the translation of GluA2 mRNA in the brain.

FXR1P represses mRNA translation through a GU-rich element in the GluA2 5'UTR

The long isoforms of GluA2 mRNA, which account for at least half of the GluA2 transcripts across various regions of the rat brain, are translationally repressed by elements within their 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions (UTRs) (Irier et al., 2009). However the molecular events controlling this repression are unknown. To test if FXR1P is a mediator of GluA2 repression, we overexpressed FXR1P with eGFP reporter constructs containing either the 5’ or 3’UTR of GluA2 in 293T cells and monitored eGFP protein levels (La Via et al., 2013) (Figure 5A). While FXR1P had no effect on eGFP expression from a control construct (Figure 5B), it significantly reduced expression of eGFP when the construct contained the 5' but not 3'UTR of GluA2 (Figure 5C). qRT-PCR experiments found that FXR1P did not affect levels of mRNAs from 5’UTR and 3’UTR eGFP constructs (Figure S5), indicating that FXR1P specifically regulates translation of the GluA2 5’UTR reporter.

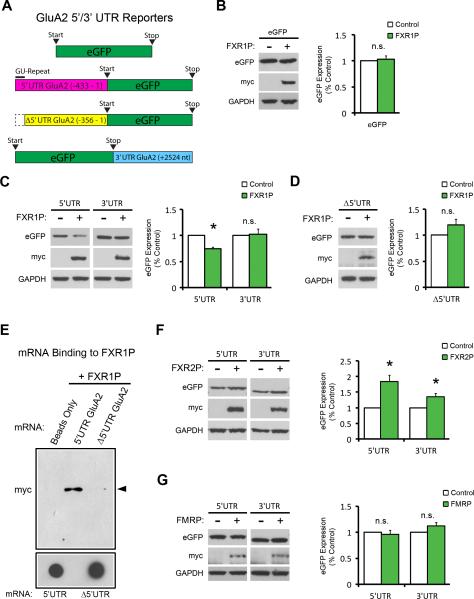

Figure 5. FXR1P represses translation through a GU-rich element in the GluA2 5’UTR.

A. Constructs used in GluA2 reporter assay; eGFP, eGFP with the GluA2 5’UTR (-433 to 1), eGFP with the 5’UTR GU-rich element removed (Δ5’UTR (-356 to 1)), and eGFP with the GluA2 3’UTR (+2524 nt). B. FXR1P does not affect expression of eGFP alone (p=0.62). C. FXR1P represses expression from the GluA2 5’UTR-eGFP (p=0.004) but not the GluA2 eGFP-3’UTR construct (p=0.84). D. Deletion of the GU-rich element relieves FXR1P-mediated repression. E. Loss of the GU-rich element prevents binding of FXR1P to the 5’UTR of GluA2. F. FXR2P increases eGFP expression from constructs containing either the GluA2 5’UTR (p=0.02) or 3’UTR (p=0.05). G. FMRP does not regulate expression from either construct (p>0.05). Analyses were performed using two-tailed, one-sample t-tests. n=3-4 separate cultures and transfections. Error bars show standard error. * p≤0.05, n.s.=not significant. See also Figure S5.

Dingledine and colleagues identified a GU-rich sequence within the 5’UTR of long isoforms of GluA2 mRNA that they termed the ‘translation suppression domain’. This sequence is predicted to form a stem-loop structure that suppresses GluA2 translation initiation (Myers et al., 2004). To determine if FXR1P uses this sequence to repress GluA2 translation, we deleted the GU-rich element from the 5'UTR and repeated the experiments above. Remarkably, loss of the GU-rich element prevented FXR1P from both repressing translation (Figure 5D) and binding to the GluA2 5’UTR (Figure 5E).

To understand if repression of GluA2 translation is specific for FXR1P, we repeated the experiments with FXR2P and FMRP. Surprisingly, we found that FXR2P enhanced eGFP levels when either the 5’ or 3’UTR was present (Figure 5F), while FMRP did not alter translation of eGFP (Figure 5G). These results agree with the FXR2P and FMRP KO data presented in Figure 4, suggesting that FXR1P represses while FXR2P promotes expression of GluA2. These results uncover a novel divergent role of FXR1P from FXR2P and FMRP in repressing GluA2 translation.

Basal surface levels of GluA2 in FXR1P cKO mice are unchanged

GluA2 is a transmembrane receptor that has functional properties at the cell surface. We next determined whether the overall increase in GluA2 expression in cKO mice caused a change in its surface level by performing surface biotinylation assays in hippocampal slices. Remarkably, the steady-state cell surface levels of GluA2 were similar between genotypes (Figure 6A), consistent with the unaltered AMPAR-mediated field potentials in cKO mice (Figure 3A). Together, these results indicate that cKO mice have normal basal surface levels of GluA2 and a potential increase in intracellular GluA2 receptor subunits.

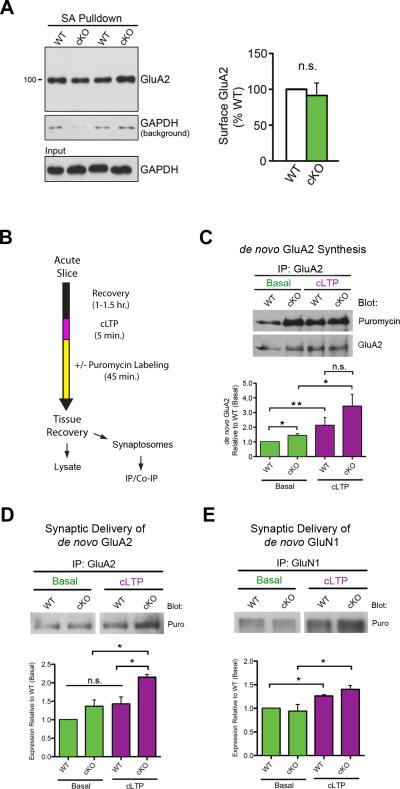

Figure 6. FXR1P controls activity-dependent synaptic delivery of GluA2.

A. Basal surface GluA2 levels are similar between genotypes (p=0.66; n=3 WT/3 cKO mice). Only low levels of GAPDH were biotinylated during the surface labeling process and purified with streptavidin (SA) beads (GAPDH background). B. Time course for cLTP experiments. C. cKO slices show increased basal de novo synthesis of GluA2 (p=0.04). Both WT and cKO slices increase GluA2 synthesis upon cLTP (WT: p=0.02 and cKO: p=0.05, two-tailed, unpaired two-sample t-test). D. cKO slices show increases in GluA2 synaptic delivery following cLTP (3 WT/3 cKO mice; p=0.01). E. GluN1 synaptic delivery is similar between genotypes (3 WT/3 cKO mice; p>0.05). Unless otherwise stated, statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed, one-sample t-tests. Error bars show standard error. **p≤0.01, *p≤0.05, n.s.=not significant. See also Figure S6.

Activity-dependent GluA2 synthesis is intact in FXR1P cKO mice

To determine if loss of FXR1P alters activity-driven increases in GluA2 translation seen during protein synthesis-dependent synaptic plasticity (Nayak et al., 1998), we subjected slices from both genotypes to forskolin-induced chemical LTP (cLTP; +forskolin, low Mg2+), a protocol which reliably induces long-lasting synaptic potentiation that occludes electrically-evoked L-LTP (Huang and Kandel, 1994; Otmakhov et al., 2004). As expected from other LTP studies, phosphorylation of serine 845 (pS845) on GluA1, a PKA phosphorylation site known to promote GluA1 trafficking to perisynaptic and extrasynaptic sites (Lee et al., 2000; Man et al., 2007; Oh et al., 2006), was significantly enhanced in WT and cKO slices upon cLTP (Figure S6A). Interestingly, we found that pS845 levels were significantly elevated in cKO slices even under basal conditions (Figure S6A). We next applied the SUnSET method to test whether cLTP-driven expression of de novo GluA2 was altered in cKO mice. Consistent with results in Figure 4E, cKO slices showed a basal increase in de novo GluA2 (Figure 6C). Despite this basal increase, we found that cLTP caused an increase in GluA2 synthesis in both WT and cKO slices, with post-cLTP de novo GluA2 levels similar between genotypes (Figure 6C). Control experiments showed that neither cLTP nor loss of FXR1P resulted in an unspecific change in protein synthesis as monitored by GAPDH production (Figure S6B). These results show that overall activity-dependent de novo GluA2 translation is not altered in cKO mice and unlikely to account for the differences in L-LTP.

Loss of FXR1P increases cLTP-driven synaptic incorporation of de novo GluA2

Despite increased steady-state GluA2 expression in the cKO, we failed to detect significant cLTP-induced differences between genotypes that may enhance L-LTP in cKO mice. This may be due to the fact that the experiments did not discriminate between subcellular compartments in neurons. To address this, we developed a method to investigate GluA2 expression at synapses using synaptosomal preparations (Figure S7A) combined with cLTP, SUnSET labeling and IP/co-IP techniques on acute slices. From our L-LTP and biochemistry results, we hypothesized that cKO mice would show enhanced cLTP-driven delivery of GluA2 subunits to synapses during an early stabilization phase of LTP (<1 hour). Thus, we tagged de novo translated GluA2 subunits with puromycin to monitor the translocation efficiency of GluA2 subunits to synapses. We found that newly synthesized GluA2 showed similar baseline incorporation into synapses in WT and cKO mice within 45 minutes (Figure 6D). This result corresponds well with our data indicating equal amounts of surface GluA2 in both genotypes under basal conditions (Figure 6A). However, de novo synthesized GluA2 subunits showed enhanced synaptic incorporation in cKO slices within 45 minutes following cLTP (Figure 6D). Enhanced synaptic GluA2 was corroborated by an increase in surface GluA2 in cKO slices upon cLTP (Figure S7B). This increase was specific to GluA2, as delivery of de novo GluN1 remained similar between genotypes (Figure 6E). Interestingly, we also found that in WT slices, FXR1P levels were significantly reduced from both crude and synaptic fractions 45 minutes following cLTP, suggesting that native FXR1P protein can be dynamically regulated in WT neurons by activity (Figure S7C-D). Altogether, the results indicate that FXR1P controls the amount of GluA2 subunits that are selectively mobilized to synapses upon long-lasting synaptic plasticity.

FXR1P controls AMPAR composition at potentiated synapses

GluA1 and GluA2 comprise the majority of AMPAR subunits at hippocampal synapses (~80%;(Lu et al., 2009)) and GluA2 synaptic incorporation is critical for L-LTP (Migues et al., 2010; Yao et al., 2008). Given the enhanced activity-dependent delivery of GluA2 to synapses in the absence of FXR1P, we investigated whether AMPAR composition was changed at synapses in cKO mice. To test this, we co-immunoprecipitated GluA2 and GluA1 subunits from synaptosomes (Kang et al., 2012). Under basal conditions, comparable amounts of GluA2 and GluA1-containing AMPARs were co-precipitated with GluA2 and GluA1, respectively. This suggests similar AMPAR composition at baseline in both genotypes (Figure 7A-B). However, following cLTP, significantly more GluA2 subunits co-precipitated with GluA2 in the cKO, as compared to WT, indicating that loss of FXR1P bolsters GluA2-GluA2 association (Figure 7A). The inverse case was found for GluA1 in the cKO, where IP of GluA1 resulted in less GluA1-containing AMPA receptors (Figure 7B). These changes were specific for AMPARs as GluN1-containing synaptic complexes were unaffected in cKO mice (Figure S7E). These results suggest that FXR1P favors an increase in GluA2 over GluA1 subunits at synapses in cKO mice following cLTP.

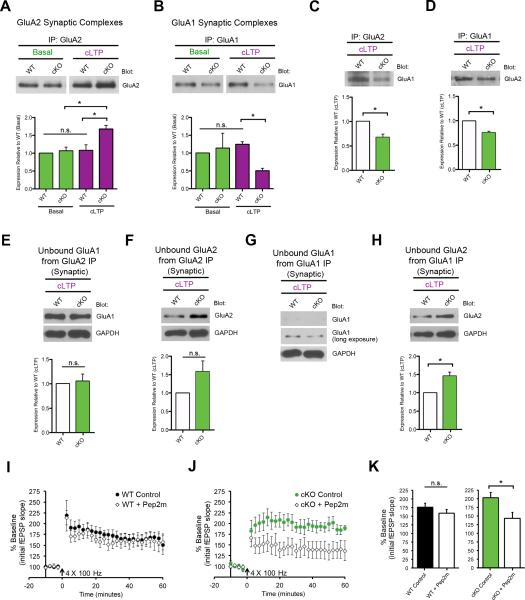

Figure 7. FXR1P controls activity-dependent AMPAR composition.

A. cKO slices show increases in GluA2-containing AMPARs at synapses following cLTP (3 WT/3 cKO mice; p=0.03). B. cKO slices show decreases in GluA1-containing AMPARs at synapses following cLTP (3 WT/3 cKO mice; p=0.002). C-D. cKO slices show decreases in association of GluA1 with GluA2 following cLTP in cKO slices (3 WT/3 cKO mice; p=0.04, p=0.01 respectively). E-H. Blotting unbound fractions from co-precipitations (C, D) show the amount of residual GluA1 and GluA2 molecules. I-J. cKO slices pre-incubated with myristoylated Pep2m show a significant reduction in potentiation at 20-30 minutes post L-LTP induction (WT (+/− pep2m): p=0.36, cKO (+/− pep2m): p=0.04, two-tailed unpaired t-tests). Unless otherwise stated statistical analyses were performed using two-tailed, one-sample t-tests *p≤0.05, n.s.=not significant. See also Figure S7.

To further dissect the composition of AMPARs at synapses in cKO mice following cLTP, we determined the relative amount of GluA1 co-associated with GluA2, and vice-versa, by either GluA2 IP and blotting for GluA1 or GluA1 IP and blotting for GluA2. Both IP combinations showed reduced association of GluA1 with GluA2 at synapses of cKO slices following cLTP (Figure 7C-D). To discriminate whether this reduced GluA1-GluA2 association was due to an enrichment of GluA2-GluA2 interactions and/or caused by a reduced amount of total synaptic GluA1, we probed unbound synaptic fractions following GluA1 or GluA2 IP (Sans et al., 2003). Blotting the unbound GluA2 IP fraction for GluA1 showed that GluA1 was not depleted from the input (Figure 7E), and in fact showed similar levels between genotypes. These results indicated that the cLTP-induced increase in GluA2-containing synaptic AMPARs in cKO slices was due to preferential GluA2-GluA2 associations. Importantly, blotting the unbound fraction for GluA2 showed that GluA2 was abundant in samples from both genotypes, confirming that the change in GluA2-GluA2 association following cLTP was not caused by an IP-mediated depletion of GluA2 from WT slices (Figure 7F). In contrast to these findings, GluA1 IP caused a depletion of GluA1 from the unbound fractions from inputs for both genotypes (Figure 7G). This suggests that the reduction in GluA2 co-precipitating with GluA1 (Figure 7D) is related to decreased GluA1-containing AMPARs at synapses in cKO slices upon cLTP. Blotting the GluA1 IP unbound fraction for GluA2 showed an increase in residual synaptic GluA2 from cKO slices (Figure 7H). These results demonstrate that FXR1P regulates GluA2 incorporation at potentiated synapses and controls activity-dependent changes in AMPAR composition.

Given these biochemical changes at cKO synapses, we sought to determine if increased trafficking/stabilization of GluA2-containing receptors to synapses contributes to elevated L-LTP (Figure 3D-E). To test this, we pre-incubated WT and cKO slices with myr-Pep2m, a cell-permeable peptide that blocks GluA2 subunit trafficking and stabilization at synapses by disrupting GluA2-NSF interactions (Nishimune et al., 1998; Yao et al., 2008) and repeated the L-LTP experiments. Remarkably, pre-incubation of slices with myr-Pep2m caused a significant reduction in L-LTP in cKO slices but not WT slices (Figure 7I-K). Thus, enhanced trafficking or stabilization of GluA2-containing receptors at synapses contributes to elevated L-LTP in cKO mice.

DISCUSSION

For long-term synaptic plasticity and memory formation to occur properly, new proteins must be synthesized in a temporally and spatially precise manner in response to specific patterns of activity, a process that is tightly controlled at the level of mRNA translation. We have identified the RNA-binding protein FXR1P as a key player in controlling specific aspects of synaptic protein expression, synaptic plasticity, and memory formation. Loss of FXR1P enhances synthesis of GluA2, increases delivery of GluA2 to potentiated synapses, heightens L-LTP, and improves long-term memory storage. Mechanistically, FXR1P utilizes the GU-rich element in the GluA2 5'UTR to repress translation. These findings define a novel molecular pathway that regulates distinct features of synaptic plasticity and cognitive function.

This study also addresses a long-standing issue in the protein translation field about how the three Fragile X protein family members (FMRP, FXR1P and FXR2P) functionally relate to each other (Bontekoe et al., 2002). All three proteins associate with polyribosomes and messenger ribonucleoprotein particles (mRNPs), are found at spines, and are expressed in similar patterns in the brain, presenting the question of whether they perform redundant functions (Cook et al., 2014; Tamanini et al., 1997, 2000). However, until now, nothing was known about the mRNA targets of FXR1P or its role in the brain. We provide several lines of evidence demonstrating the functional divergence of FXR1P with FMRP and FXR2P in synaptic plasticity, behavior, spine development and GluA2 translational control. First, whereas FMRP and FXR2P function predominantly in hippocampal mGluR-LTD (Zhang et al., 2009), FXR1P participates selectively in L-LTP. Second, FXR1P cKO mice display improved long-term spatial memory, while FMRP and FXR2P KO animals show memory impairments (Bontekoe et al., 2002; Kooy et al., 1996). Third, loss of FXR1P reduces spine density and spine size, whereas loss of FMRP increases spine density and length. Lastly, FXR1P represses whereas FXR2P enhances GluA2 translation, while FMRP has no major effect. Overall, our work reveals a unique function for FXR1P and offers a clear demonstration of the differential role of Fragile X proteins in brain plasticity. For future studies it may be of interest to explore the combinatorial role of this family of mRNA binding proteins in plasticity by using double cKO models of FXR1P/FMRP and FXR1P/FXR2P.

An intriguing finding is the specificity of the FXR1P cKO behavioral phenotype. While cKO mice perform normally on the majority of behavioral paradigms, they demonstrate a specific improvement in long-term spatial memory and alteration in behavioral flexibility. Most revealing is the observation that cKOs show greater long-term memory recall 9 days post-initial training and show similar preference for new and old platform locations during the reversal probe test, suggesting that cKO mice maintain stronger memories that allow them to keep multiple memories 'on-line' when performing a task. This phenotype is striking considering that mutant mice with alterations to general protein synthesis pathway components commonly show impairments in long-term memory (Costa-Mattioli et al., 2005, 2007; Kelleher et al., 2004) or, in some cases, increased perseverative behavior (Hoeffer et al., 2008; Trinh et al., 2012). The fact that cKO mice readily learn a new platform location suggests that they do not perseverate in this task, rather they maintain and retrieve multiple spatial memory traces and are able to more rapidly and efficiently shift between memory stores based on changing performance demands (i.e. platform removal during the reversal probe trial). By constraining the magnitude of long-lasting increases in synaptic strength, FXR1P may control the extent of information storage in brain circuits.

Remarkably, of the synaptic proteins we screened, FXR1P only affects the protein synthesis of GluA2. This is surprising in light of the fact that FMRP binds approximately 800 brain mRNAs (Darnell et al., 2011), associates with diverse RNA cargoes (Ascano et al., 2012; Miyashiro et al., 2003), and controls translation initiation of multiple targets through eIF4E (Napoli et al., 2008). Although we cannot rule out whether FXR1P regulates any other proteins, GluA2 is an interesting target since it is present at the majority of brain excitatory synapses, confers calcium impermeability to AMPARs, and is critical for long-lasting synaptic plasticity and spatial memories (Isaac et al., 2007; Migues et al., 2010; Yao et al., 2008). Furthermore, GluA2 is known to be regulated at the level of mRNA translation, although exactly how this is accomplished is unknown. Our results indicate that FXR1P binds and represses translation of transcripts with the long 5’UTR of GluA2 containing a GU-rich element that is predicted to form a stem-loop structure that interferes with translation initiation (Myers et al., 2004). Notably, this GU-rich repeat is present in human GluA2 transcripts, causing a 2.5 to 3-fold reduction in GluA2 translation efficiency (Myers et al., 2004). Translational control of GluA2 mRNA through the GU-rich sequence by FXR1P may be a conserved mechanism for carefully titrating the amount of long-lasting synaptic plasticity and memory storage in the brain.

Interestingly, a basal increase in GluA2 mRNA translation in FXR1P cKO mice is not accompanied by baseline increases in its surface levels, synaptic incorporation, or synaptic transmission. This indicates that neurons in cKO mice have a larger internal reserve of GluA2 that is specifically mobilized to synapses during protein synthesis-dependent plasticity such as L-LTP. Baseline phosphorylation of GluA1 S845, but not total levels of GluA1, is also enhanced in cKO mice. The reason underlying this modification is unclear. However, as pS845 promotes trafficking of GluA1-containing AMPARs to extrasynaptic and perisynaptic sites, this alteration in cKO mice may further promote the exchange of GluA2 for GluA1 at synapses and increase the ability of GluA2-containing AMPARs to compete for synaptic territory during L-LTP. Remarkably, the enhancement in synaptic strength in the cKO mice is only revealed by a strong stimulus that elicits protein synthesis-dependent L-LTP, and not by a stimulus that promotes E-LTP. Thus, the activity-dependent production or modification of facilitatory proteins is still required to mobilize the reserve pool of GluA2 to synapses. Furthermore, elevations in L-LTP in cKO mice can be suppressed by blocking GluA2 trafficking or stabilization at the synapse with myr-Pep2m, a peptide which blocks GluA2-NSF interactions. This result further supports the increased role played by GluA2-containing receptors in L-LTP. The increased size of the GluA2 reserve pool in cKO mice may enable more rapid stabilization of L-LTP and better maintenance of memories (Kelz et al., 1999; Migues et al., 2010; Yao et al., 2008). These findings are in alignment with discoveries showing that the size of the AMPAR reserve pool is important for LTP (Granger et al., 2013) and provide the first in vivo demonstration of an endogenous GluA2 gain-of-function effect on synaptic properties. Interestingly, single-nucleotide polymorphisms in glutamate receptor interacting protein 1 (GRIP1) that promote GluA2 surface stabilization in neurons are associated with autism (Mejias et al., 2011), further implicating synaptic GluA2 levels in regulating cognitive function. Future studies need to dissect the molecular network surrounding FXR1P and further understand its role in modifying brain plasticity states.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

Experiments were approved by the Montreal General Hospital FACC and followed guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care. Both male and female mice were used for experiments. All mice were kept on a standard 12 hr light:dark cycle and socially housed (2-5 animals per cage).

FXR1P conditional knockout mice

Floxed Fxr1 mice (Fragile-X Mutant Mouse Facility, Baylor College of Medicine) were crossed into the αCaMKII-Cre T29-1 Cre-recombinase driver line (The Jackson Laboratory) (Sonner et al., 2005; Tsien et al., 1996). Experimental animals were generated by crossing αCaMKII-Cre tg/tg; Fxr1 fl/+ mice with Fxr1 fl/+ mice to generate αCaMKII-Cre tg/+; Fxr1 fl/fl (FXR1P cKO), αCaMKII-Cre tg/+; Fxr1 fl/+ (FXR1P cHET) and αCaMKII-Cre tg/+; Fxr1 +/+ (WT). These lines were backcrossed into C57BL/6 for at least 10 generations. To track cells which have undergone Cre-mediated recombination, we crossed αCaMKII-Cre tg/tg; Fxr1 fl/+ mice with the mTom/mGFP reporter line (The Jackson Laboratory) (Muzumdar et al., 2007). The reporter line was backcrossed into a C57BL/6 background for at least five generations.

FMRP and FXR2P knockout mice

Whole hippocampal tissue from C57BL/6 background Fmr1 KO and Fxr2 KO adult mice (>7 weeks) was received from the David L. Nelson laboratory. Lysates were prepared and processed for Western blotting as previously described (Cook et al., 2011).

Plasmids

5’UTR (-433-1) and 3’UTR (+2524nt) GluA2 eGFP constructs were described previously (La Via et al., 2013). The 5’UTR GU mutant (deletion of 65 bases from −429 to −365 containing the GU-repeat region) was generated using the existing restriction sites BssHII and NheI as described in (Irier et al., 2009).

Immunohistochemistry, DiI labeling of CA1 dendrites, and imaging

Perfusion, cryostat sectioning and imaging were performed as previously described (Cook et al., 2011). See Supplemental Information section for details on DiI labeling and antibodies.

Whole hippocampal and CA1 lysates and Western blotting

Whole hippocampal and CA1 lysates were prepared and processed for blotting as previously described (Cook et al., 2011). See Supplemental Information for details on antibodies used.

Polysome fractionation

Experiments were performed as previously described on mice aged 13-16 weeks old (Gandin et al., 2014). EDTA (200μg/ml) was added to the lysis buffer to disrupt polysomes.

Behavior

Behavioral assessments were performed between 9:00 am-3:00 pm on 2-6 month old mice and conducted by an investigator blind to genotype. A period of acclimatization to the environment (10-15 minutes) preceded all experiments. Four separate cohorts of mice were tested on the Morris water maze, object recognition test and fear conditioning tests (in that order), with at least 72 hours between the beginning and end of each new paradigm. Mice from cohorts 3 & 4 were subsequently used in field recording experiments. Mice that were tested in the open field as well as in the dark-light box test were allowed at least 1 week between the two behavioral paradigms. Besides the differences in behavioral phenotypes reported in Figure 2, no other phenotypic changes were observed. See Supplemental Information section for additional details regarding each of the behavioral paradigms used.

Electrophysiology

Standard procedures were used for fEPSP recordings. Mice (5-9 months old; used previously in behavioral testing) were anesthetized using isoflurane and quickly decapitated. The whole brain was immersed in ice-cold ACSF (in mM): NaCl 124, KCl 3, NaH2PO4 1.25, CaCl2 2, MgSO4 1, NaHCO3 26, D-Glucose 10 and saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2. Coronal slices with a thickness of 300-400μm were cut using a Leica VT1200S and transferred to a submersion chamber containing regular ACSF at a temperature of 32-37°C for 25-30 minutes after which the chamber was placed on the bench at room temperature. Slices were allowed to recover in the submersion chamber for at least four hours (Sajikumar et al., 2005). After the recovery period, slices were transferred to a submersion chamber mounted on an electrophysiology rig, perfused with regular ACSF (3 ml/min) and maintained at 28-31°C. Field synaptic responses were evoked by stimulating Schaffer collaterals with 0.1 ms pulses delivered at 0.033-0.067 Hz and recorded extracellularly in CA1 stratum radiatum. Input-output curves were generated by stimulating with different intensities (n=18 WT mice from 11 litters, n=19 cKO mice from 11 litters). For all subsequent experiments, stimulation intensity was set to elicit a fEPSP with a slope that was approximately 40% of maximum obtained slope. Paired-pulse facilitation was determined by delivering pulses at varying inter-pulse intervals (n=7 WT mice from 6 litters, n=8 cKO mice from 6 litters). E-LTP was induced with a single train of high frequency stimulation (1 × 100 Hz) using baseline stimulation intensity (n=10 mice, 12 slices, from 5 litters). L-LTP was induced using four trains of high frequency stimulation with a 20 second interval (4×100 Hz) using baseline stimulation intensity (n=7 mice, 7 slices, from 5 litters). For mGluR-LTD induction, slices from mice aged 5-9 weeks were perfused for 7-8 minutes with DHPG (100μM) and the initial stimulation was kept at 0.5 mV (n=4 mice, 8 slices for WT; n=6 mice, 8 slices for cKO). For GluA2-NSF disruption experiments, slices from mice aged 3.5 to 6 months were incubated for at least 1 hour with myristoylated-pep2m (100 μM; Tocris) in ACSF prior to switching to normal ACSF for baseline recordings and L-LTP (n=5 mice, 5 slices for WT Control; n=4 mice, 7 slices for WT pep2m, n=4 mice, 5 slices cKO Control; n=5 mice, 5 slices for cKO pep2m). To reduce the possibility of rundown of basal responses by pep2m, test stimulations were given every 15 seconds as done previously (Yao et al., 2008).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

Standard methods were used for qRT-PCR. More information on qRT-PCR can be found in the Supplemental Information section.

GluA2 reporter assays and FXR1P binding to the GluA2 5'UTR

For information on these assays see Supplemental Information section.

SUnSET labeling of newly synthesized proteins and immunoprecipitation assays

Adult mice (>12 weeks) were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane in an enclosed chamber and decapitated. The brain was quickly removed and immersed in ice-cold ACSF containing the following (in mM): 119 CholineCl, 2.5 KCl, 4.3 MgSO4, 1.0 NaH2PO4, 1.0 CaCl2, 1.30 Na-Ascorbate, 11 Glucose, and 26.2 NaHCO3, continuously bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2, pH 7.4. Coronal slices (400μm) containing the hippocampus were obtained using a vibratome. Slices (3-4 per condition) were recovered at room temperature for 1–1.5 hrs in oxygenated ACSF with the following composition (in mM): 119 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.3 MgSO4, 1.0 NaH2PO4, 2.5 CaCl2, 11 glucose, and 26.2 NaHCO3, pH 7.4. Surface sensing of translation (SUnSET; (Schmidt et al., 2009)) was then used to probe for newly synthesized proteins. Briefly, slices were incubated with puromycin (5 μg/ml) for 45 min. Control slices were incubated first with cycloheximide (CHX) (C7698 Sigma-Aldrich; 20 μg/ml) for 30 min and then with puromycin plus cycloheximide for 45 min. Following the incubation, the tissue was snap frozen using either dry ice or liquid nitrogen. Tissue was then lysed (RIPA lysis buffer) and prepared for Western blot or immunoprecipitation with GluA2 antibodies. GluA2 immunoprecipitates were blotted for puromycin and stripped and reprobed for GluA2. The level of puromycin-labeled GluA2 was normalized to the amount of immunoprecipitated GluA2. For the synaptic GluA1/GluA2 AMPA receptor complex analysis, after puromycin incubation, tissue was lysed in Syn-PER Synaptic Protein extraction Reagent (Thermo Scientific #87793) and the synaptosomal fraction was extracted as per supplier's directions. Following synaptosomal purification, co-immunoprecipitation experiments for GluA1 and GluA2 were carried out using a previously published protocol (Kang et al., 2012). Co-immunoprecipitated lysate, as well as the unbound fraction from the co-immunoprecipitation, were blotted for GluA2 and GluA1 using anti-GluA2 and anti-GluA1 antibodies.

Chemical LTP

cLTP methods were adapted from previously published studies (Huang and Kandel, 1994; Otmakhov et al., 2004). Briefly, coronal slices prepared as mentioned above were incubated for 5 min in oxygenated ACSF (low Mg2+, 0.13 mM) with forskolin (F6886 Sigma-Aldrich; 50μM dissolved in DMSO). Slices were then transferred into oxygenated ACSF containing puromycin (P8833 Sigma-Aldrich; 5μg/ml) and incubated for 45 min. For the control group, slices were incubated with DMSO (50μM) in regular ACSF for 5 min, then incubated in puromycin for 45 min. Slices were then processed for Western blotting or immunoprecipitation as described above.

Surface biotinylation assays

To investigate cell surface expression of GluA2, transverse hippocampal sections (300μm) were obtained using a tissue chopper from adult mice (>8 weeks). The sections were incubated with biotin (1mg/ml in PBS) solution for 30-40 min at 4°C and then homogenized with lysis buffer (PBS/0.1%SDS/10%Glycerol). Upon homogenization the lysate was incubated with streptavidin beads (50μl/sample pre-washed with PBS) for 1hr and then prepared for Western blotting. For the activity-dependent surface GluA2 receptor analysis, after cLTP induction, tissue was incubated at 4°C in bubbling ACSF with biotin for 45 min. The tissue was then snap frozen using dry ice, lysed, and incubated with streptavidin beads (50μl/sample pre-washed with PBS) for 1hr and then prepared for Western blotting.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using R (http://www.R-project.org) with the following packages: Reshape, Hmisc, gplots, plotrix and ezANOVA or Microsoft Excel. α=0.05 was chosen for statistical significance. Tests used are noted in figure legends. Analyses have been collapsed across sex to reflect the fact that preliminary ANOVAs demonstrated no sex effect. All graphs were created using R or Microsoft Excel.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP111152 and MOP123390 to K.K.M.) and the National Institutes of Health (1R21DA026053-01 to K.K.M. and D.S.). I.T. is a CIHR Young Investigator Award and FRQ-S (subvention Établissement de jeunes chercheurs) recipient. D.C. was supported through Doctoral Awards from CIHR and FRSQ. E.N. and H.F.A. were supported by awards from the Integrated Program in Neuroscience and Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, respectively. The authors thank Dr. E. Khandjian (Laval U.) for the FXR1P antibody, P. Thandapani for help with the mRNA binding studies, and E.M. Charbonneau for expert technical work on the behavioral studies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.C, E.N and K.K.M designed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. D.C. established the FXR1P cKO line and performed experiments and analyzed data for Figs. 1-3, Suppl. Figs. 1-2. E.N. performed experiments and analyzed data for Figs. 4, 6-7, Suppl. Figs. 3, 4, 6, and 7.

REFERENCES

- Ascano M, Mukherjee N, Bandaru P, Miller JB, Nusbaum JD, Corcoran DL, Langlois C, Munschauer M, Dewell S, Hafner M, et al. FMRP targets distinct mRNA sequence elements to regulate protein expression. Nature. 2012;492:382–386. doi: 10.1038/nature11737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontekoe CJM, McIlwain KL, Nieuwenhuizen IM, Yuva-Paylor L. a, Nellis A, Willemsen R, Fang Z, Kirkpatrick L, Bakker CE, McAninch R, et al. Knockout mouse model for Fxr2: a model for mental retardation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:487–498. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.5.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D, Sanchez-Carbente M. del R., Lachance C, Radzioch D, Tremblay S, Khandjian EW, DesGroseillers L, Murai KK. Fragile X related protein 1 clusters with ribosomes and messenger RNAs at a subset of dendritic spines in the mouse hippocampus. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook D, Nuro E, Murai KK. Increasing our understanding of human cognition through the study of Fragile X Syndrome. Dev. Neurobiol. 2014;74:147–177. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mattioli M, Gobert D, Harding H, Herdy B, Azzi M, Bruno M, Bidinosti M, Ben Mamou C, Marcinkiewicz E, Yoshida M, et al. Translational control of hippocampal synaptic plasticity and memory by the eIF2alpha kinase GCN2. Nature. 2005;436:1166–1173. doi: 10.1038/nature03897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mattioli M, Gobert D, Stern E, Gamache K, Colina R, Cuello C, Sossin W, Kaufman R, Pelletier J, Rosenblum K, et al. eIF2alpha phosphorylation bidirectionally regulates the switch from short- to long-term synaptic plasticity and memory. Cell. 2007;129:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mattioli M, Sossin WS, Klann E, Sonenberg N. Translational control of long-lasting synaptic plasticity and memory. Neuron. 2009;61:10–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JC, Van Driesche SJ, Zhang C, Hung KYS, Mele A, Fraser CE, Stone EF, Chen C, Fak JJ, Chi SW, et al. FMRP stalls ribosomal translocation on mRNAs linked to synaptic function and autism. Cell. 2011;146:247–261. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrunz LE, Stevens CF. Heterogeneity of release probability, facilitation, and depletion at central synapses. Neuron. 1997;18:995–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle M, Kiebler MA. Mechanisms of dendritic mRNA transport and its role in synaptic tagging. EMBO J. 2011;30:3540–3552. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elvira G, Wasiak S, Blandford V, Tong X-K, Serrano A, Fan X, del Rayo Sánchez-Carbente M, Servant F, Bell AW, Boismenu D, et al. Characterization of an RNA granule from developing brain. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2006;5:635–651. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500255-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandin V, Sikström K, Alain T, Morita M, McLaughlan S, Larsson O, Topisirovic I. Polysome fractionation and analysis of mammalian translatomes on a genome-wide scale. J. Vis. Exp. 2014 doi: 10.3791/51455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnon J, Lachance C, Di Marco S, Hel Z, Marion D, Ruiz MC, Newkirk MM, Khandjian EW, Radzioch D. Fragile X-related protein FXR1P regulates proinflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor expression at the post-transcriptional level. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:5750–5763. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401988200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajan A, Kelleher RJ, Tonegawa S. A clustered plasticity model of long-term memory engrams. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;7:575–583. doi: 10.1038/nrn1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger AJ, Shi Y, Lu W, Cerpas M, Nicoll RA. LTP requires a reserve pool of glutamate receptors independent of subunit type. Nature. 2013;493:495–500. doi: 10.1038/nature11775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershey JWB, Sonenberg N, Mathews MB. Principles of translational control: an overview. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012;4 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeffer CA, Tang W, Wong H, Santillan A, Patterson RJ, Martinez L. a, Tejada-Simon MV, Paylor R, Hamilton SL, Klann E. Removal of FKBP12 enhances mTOR Raptor interactions, LTP, memory, and perseverative/repetitive behavior. Neuron. 2008;60:832–845. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YY, Kandel ER. Recruitment of long-lasting and protein kinase A-dependent long-term potentiation in the CA1 region of hippocampus requires repeated tetanization. Learn. Mem. 1994;1:74–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber KM, Gallagher SM, Warren ST, Bear MF. Altered synaptic plasticity in a mouse model of fragile X mental retardation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:7746–7750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122205699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irier HA, Quan Y, Yoo J, Dingledine R. Control of glutamate receptor 2 (GluR2) translational initiation by its alternative 3’ untranslated regions. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009;76:1145–1149. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.060343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac JTR, Ashby MC, McBain CJ. The role of the GluR2 subunit in AMPA receptor function and synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2007;54:859–871. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai Y, Dohmae N, Hirokawa N. Kinesin transports RNA: isolation and characterization of an RNA-transporting granule. Neuron. 2004;43:513–525. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M-G, Nuriya M, Guo Y, Martindale KD, Lee DZ, Huganir RL. Proteomic analysis of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate receptor complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:28632–28645. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.336644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher RJ, Govindarajan A, Jung H-Y, Kang H, Tonegawa S. Translational control by MAPK signaling in long-term synaptic plasticity and memory. Cell. 2004;116:467–479. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelz MB, Chen J, Carlezon WA, Whisler K, Gilden L, Beckmann AM, Steffen C, Zhang YJ, Marotti L, Self DW, et al. Expression of the transcription factor deltaFosB in the brain controls sensitivity to cocaine. Nature. 1999;401:272–276. doi: 10.1038/45790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels HW, Malinow R. Synaptic AMPA receptor plasticity and behavior. Neuron. 2009;61:340–350. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooy RF, D'Hooge R, Reyniers E, Bakker CE, Nagels G, De Boulle K, Storm K, Clincke G, De Deyn PP, Oostra B. a, et al. Transgenic mouse model for the fragile X syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1996;64:241–245. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960809)64:2<241::AID-AJMG1>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HK, Barbarosie M, Kameyama K, Bear MF, Huganir RL. Regulation of distinct AMPA receptor phosphorylation sites during bidirectional synaptic plasticity. Nature. 2000;405:955–959. doi: 10.1038/35016089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Shi Y, Jackson AC, Bjorgan K, During MJ, Sprengel R, Seeburg PH, Nicoll R. a. Subunit composition of synaptic AMPA receptors revealed by a single-cell genetic approach. Neuron. 2009;62:254–268. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Man H-Y, Sekine-Aizawa Y, Huganir RL. Regulation of {alpha}-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor trafficking through PKA phosphorylation of the Glu receptor 1 subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:3579–3584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611698104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejias R, Adamczyk A, Anggono V, Niranjan T, Thomas GM, Sharma K, Skinner C, Schwartz CE, Stevenson RE, Fallin MD, et al. Gain-of-function glutamate receptor interacting protein 1 variants alter GluA2 recycling and surface distribution in patients with autism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:4920–4925. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102233108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mientjes EJ, Willemsen R, Kirkpatrick LL, Nieuwenhuizen IM, Hoogeveen-Westerveld M, Verweij M, Reis S, Bardoni B, Hoogeveen AT, Oostra B, et al. Fxr1 knockout mice show a striated muscle phenotype: implications for Fxr1p function in vivo. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2004;13:1291–1302. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migues PV, Hardt O, Wu DC, Gamache K, Sacktor TC, Wang YT, Nader K. PKMzeta maintains memories by regulating GluR2-dependent AMPA receptor trafficking. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:630–634. doi: 10.1038/nn.2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashiro KY, Beckel-Mitchener A, Purk TP, Becker KG, Barret T, Liu L, Carbonetto S, Weiler IJ, Greenough WT, Eberwine J. RNA cargoes associating with FMRP reveal deficits in cellular functioning in Fmr1 null mice. Neuron. 2003;37:417–431. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, Li L, Luo L. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis. 2007;45:593–605. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers SJ, Huang Y, Genetta T, Dingledine R. Inhibition of glutamate receptor 2 translation by a polymorphic repeat sequence in the 5’-untranslated leaders. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:3489–3499. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4127-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napoli I, Mercaldo V, Boyl PP, Eleuteri B, Zalfa F, De Rubeis S, Di Marino D, Mohr E, Massimi M, Falconi M, et al. The fragile X syndrome protein represses activity-dependent translation through CYFIP1, a new 4E-BP. Cell. 2008;134:1042–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak A, Zastrow DJ, Lickteig R, Zahniser NR, Browning MD, Essen V. Maintenance of late-phase LTP is accompanied by PKA-dependent increase in AMPA receptor synthesis. Nature. 1998;394:680–683. doi: 10.1038/29305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimune a, Isaac JT, Molnar E, Noel J, Nash SR, Tagaya M, Collingridge GL, Nakanishi S, Henley JM. NSF binding to GluR2 regulates synaptic transmission. Neuron. 1998;21:87–97. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80517-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh MC, Derkach VA, Guire ES, Soderling TR. Extrasynaptic membrane trafficking regulated by GluR1 serine 845 phosphorylation primes AMPA receptors for long-term potentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:752–758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otmakhov N, Tao-Cheng J-H, Carpenter S, Asrican B, Dosemeci A, Reese TS, Lisman J. Persistent accumulation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in dendritic spines after induction of NMDA receptor-dependent chemical long-term potentiation. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:9324–9331. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2350-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajikumar S, Navakkode S, Frey JU. Protein synthesis-dependent long-term functional plasticity: methods and techniques. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2005;15:607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sans N, Vissel B, Petralia RS, Wang Y-X, Chang K, Royle G. a, Wang C-Y, O'Gorman S, Heinemann SF, Wenthold RJ. Aberrant formation of glutamate receptor complexes in hippocampal neurons of mice lacking the GluR2 AMPA receptor subunit. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:9367–9373. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-28-09367.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf MT, Woo NH, Lattal KM, Young JZ, Nguyen PV, Abel T. Protein Synthesis Is Required for the Enhancement of Long-Term Potentiation and Long-Term Memory by Spaced Training. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;87:2770–2777. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.87.6.2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt EK, Clavarino G, Ceppi M, Pierre P. SUnSET, a nonradioactive method to monitor protein synthesis. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:275–277. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuman EM, Dynes JL, Steward O. Synaptic regulation of translation of dendritic mRNAs. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:7143–7146. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1796-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonner JM, Cascio M, Xing Y, Fanselow MS, Kralic JE, Morrow AL, Korpi ER, Hardy S, Sloat B, Eger EI, et al. Alpha 1 subunit-containing GABA type A receptors in forebrain contribute to the effect of inhaled anesthetics on conditioned fear. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005;68:61–68. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.009936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamanini F, Willemsen R, van Unen L, Bontekoe C, Galjaard H, Oostra B. a, Hoogeveen a T. Differential expression of FMR1, FXR1 and FXR2 proteins in human brain and testis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1997;6:1315–1322. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.8.1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamanini F, Kirkpatrick LL, Schonkeren J, van Unen L, Bontekoe C, Bakker C, Nelson DL, Galjaard H, Oostra B. a, Hoogeveen a T. The fragile X-related proteins FXR1P and FXR2P contain a functional nucleolar-targeting signal equivalent to the HIV-1 regulatory proteins. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:1487–1493. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.10.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinh MA, Kaphzan H, Wek RC, Pierre P, Cavener DR, Klann E. Brain-Specific Disruption of the eIF2α Kinase PERK Decreases ATF4 Expression and Impairs Behavioral Flexibility. Cell Rep. 2012;1:676–688. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien JZ, Chen DF, Gerber D, Tom C, Mercer EH, Anderson DJ, Mayford M, Kandel ER, Tonegawa S. Subregion- and cell type-restricted gene knockout in mouse brain. Cell. 1996;87:1317–1326. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81826-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan S, Steitz JA. AU-rich-element-mediated upregulation of translation by FXR1 and Argonaute 2. Cell. 2007;128:1105–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Via L, Bonini D, Russo I, Orlandi C, Barlati S, Barbon A. Modulation of dendritic AMPA receptor mRNA trafficking by RNA splicing and editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:617–631. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitman SA, Cover C, Yu L, Nelson DL, Zarnescu DC, Gregorio CC. Desmoplakin and talin2 are novel mRNA targets of fragile X-related protein-1 in cardiac muscle. Circ. Res. 2011;109:262–271. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.244244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Kelly MT, Sajikumar S, Serrano P, Tian D, Bergold PJ, Frey JU, Sacktor TC. PKM zeta maintains late long-term potentiation by N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor/GluR2-dependent trafficking of postsynaptic AMPA receptors. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:7820–7827. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0223-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Hou L, Klann E, Nelson DL. Altered hippocampal synaptic plasticity in the FMR1 gene family knockout mouse models. J. Neurophysiol. 2009;101:2572–2580. doi: 10.1152/jn.90558.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.