SUMMARY

Exosomes are secreted by all cell types and contain proteins and nucleic acids. Here, we report that breast cancer associated exosomes contain microRNAs (miRNAs) associated with the RISC Loading Complex (RLC) and display cell-independent capacity to process precursor microRNAs (pre-miRNAs) into mature miRNAs. Pre-miRNAs, along with Dicer, AGO2, and TRBP, are present in exosomes of cancer cells. CD43 mediates the accumulation of Dicer specifically in cancer exosomes. Cancer exosomes mediate an efficient and rapid silencing of mRNAs to reprogram the target cell transcriptome. Exosomes derived from cells and sera of patients with breast cancer instigate non-tumorigenic epithelial cells to form tumors in a Dicer-dependent manner. These findings offer opportunities for the development of exosomes based biomarkers and therapies.

INTRODUCTION

Exosomes are nano-vesicles of 50–140 nm in size that contain proteins, mRNA, and microRNAs (miRNAs) protected by a lipid bilayer (Kahlert and Kalluri, 2013; Cocucci et al., 2009; Simons and Raposo, 2009; Simpson et al., 2008; Thery et al., 2002). Several recent studies demonstrated that exosomes are secreted by multiple cell types including cancer cells, stem cells, immune cells and neurons (Thery, 2011). Exosomes levels in the serum of breast cancer patients are generally higher when compared to normal subjects (Logozzi et al., 2009; Taylor and Gercel-Taylor, 2008; O’Brien et al., 2013).

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNAs of 18–24 nucleotides (nt) in length that control gene expression post-transcriptionally. They are synthesized via sequential actions of Drosha and Dicer endonucleases, and incorporate with the RNA induced silencing complex (RISC) to target mRNAs (Bartel, 2009; Maniataki and Mourelatos, 2005). RISC-loaded miRNAs bind in a sequence-specific manner to target mRNAs, initiating their repression through a combination of translational inhibition, RNA destabilization or through direct RISC-mediated mRNA cleavage (Ambros, 2004; Bartel, 2009; Filipowicz, 2005). For a miRNA to be functional and achieve efficient gene silencing, it must form a complex with the RLC (RISC-loading complex) proteins Dicer, TRBP, and AGO2. Within the RLC, Dicer and TRBP process precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs) after they emerge from the nucleus via exportin-5, to generate miRNAs and associate with AGO2. AGO2 bound to the mature miRNA constitutes the minimal RISC and may subsequently dissociate from Dicer and TRBP (Chendrimada et al., 2005; Gregory et al., 2005; Haase et al., 2005; MacRae et al., 2008; Maniataki and Mourelatos, 2005; Melo et al., 2009). Single-stranded miRNAs by themselves incorporate into RISC very poorly and therefore, cannot be efficiently directed to target mRNAs for post-transcriptional regulation (Tang, 2005; Thomson et al., 2013). Nonetheless, several reports suggest that miRNAs contained in exosomes can influence gene expression in target cells (Ismail et al., 2013; Kogure et al., 2011; Kosaka et al., 2013; Narayanan et al., 2013; Pegtel et al., 2010; Valadi et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2010). Drosha and Dicer are present in exosomes from cell culture supernatants from HIV-1 infected cells and HIV patient sera (Narayanan et al., 2013). Co-fractionation of Dicer, TRBP and AGO2 in late endosome/MVB (multivesicular body) is also observed (Shen et al., 2013). These studies reflect the need to evaluate the functional contribution of miRNA machinery proteins in exosomes and their role in tumor progression

RESULTS

Isolation and Identification of Exosomes

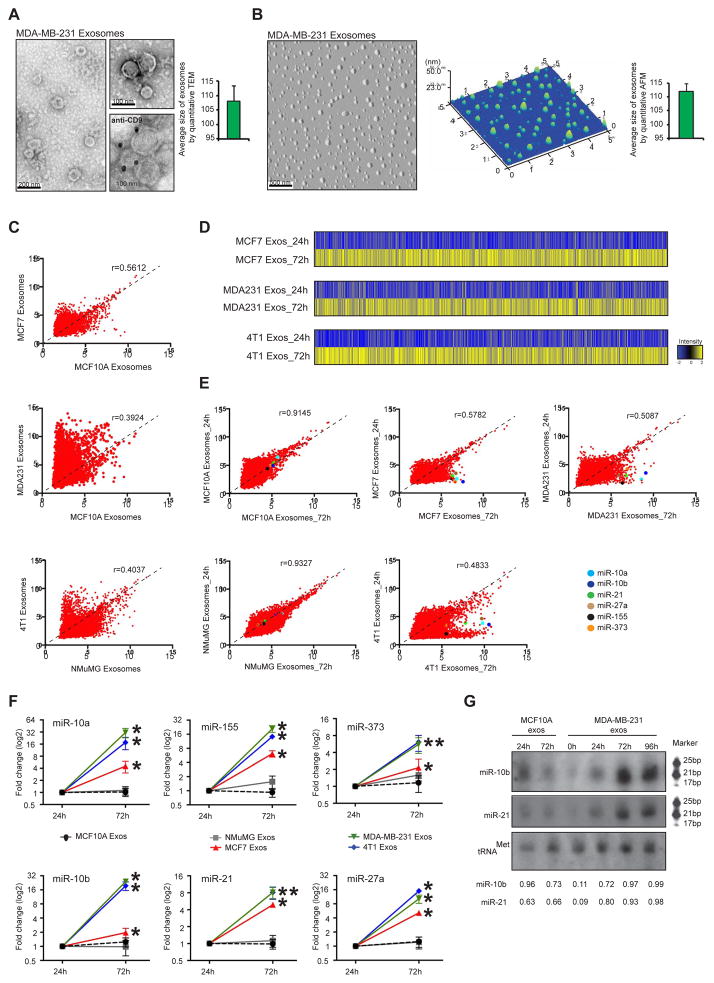

Exosomes from cancer cells (MDA-MB-231 triple negative human metastatic breast carcinoma, MCF7 human breast adenocarcinoma, 67NR mouse non-metastatic mammary carcinoma and 4T1 mouse metastatic mammary carcinoma) and control cells (MCF10A non-tumorigenic human mammary epithelial cells and NMuMG non-tumorigenic mouse mammary epithelial cells) were isolated using established ultracentrifugation methods (Figure S1A, see experimental procedures section) (Luga et al., 2012; Thery et al., 2006). The harvested exosomes were analyzed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM). Particles between 50–140 nm were identified (Figure 1A–B) (Thery et al., 2002). The average size observed in 112 captured images by TEM was 108±6 nm and by AFM was 112±5 nm (Figure 1A–B, graphs). The identity of the exosomes was confirmed through detection of TSG101, CD9 and CD63, three exosomes markers (Figure S1B) (Thery et al., 2006). The isolated exosomes were also positive for the CD9 marker by immunogold TEM (Figure 1A lower right panel). Exosomes coupled to latex beads were analyzed by flow cytometry, showing surface expression of CD9, flotillin1, CD63 and TSG101 the commonly used exosomes markers (Figure S1C). Light Scattering Spectroscopy (LSS) (Fang et al., 2007; Itzkan et al., 2007) was used to show that the isolated samples reveal a tight size distribution with a mode value peaking at 104 nm (Figure S1D). LSS also excluded potential microvesicles and bacterial or cellular debris contamination (Figure S1D). In agreement with LSS data, the NanoSight nanoparticle tracking analysis for MCF10A, MCF7, MDA-MB-231, 67NR, 4T1 and NMuMG exosomes revealed an average of the mode value of 103 ± 5 nm (Figure S1E). Based on LSS and NanoSight analysis, the most prevalent population of particles in solution ranged in size from 89 to 118 nm in diameter (Figure S1D–E). Colorimetric cell viability assay (MTT), terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay, flow cytometry analysis for Anexin V using propidium iodide and cytochrome C immunoblots (Figure S1F–I) were used to demonstrate the viability of cells prior to exosomes extraction to exclude apoptotic bodies or random cell debris. Exosomes isolated from cancer cells are collectively termed as cancer exosomes, whereas exosomes isolated from control cells are collectively termed normosomes.

Figure 1. Cancer exosomes become enriched in miRNAs.

(A) Transmission electron micrograph of MDA-MB-231 exosomes. Lower right image produced by immunogold of CD9 and TEM of MDA-MB-231 exosomes. Gold particles are depicted as black dots. Graph represents the average size of exosomes analyzed from 112 TEM pictures. (B) AFM image of MDA-MB-231 exosomes. Middle graph represents dispersion of particles in the coverslip with size range of exosomes. Right graph represents average size of exosomes analyzed from 26 AFM pictures. (C) Scattterplots of miRNAs expression assessed by miRNA array, in MCF-7, MCF10A, MDA-MB-231, 4T1 and NMuMG exosomes. Pearson correlation coefficient, r, is used as a measure of the strength of the linear relationship between 2 exosomes samples. (D) HeatMaps of miRNAs expression array of cancer exosomes cultured for 24 and 72 hr (MCF-7 exosomes cultured for 24 hr versus MCF-7 exosomes cultured for 72 hr; MDA-MB-231 exosomes cultured for 24 hr versus MDA-MB-231 exosomes cultured for 72 hr; and 4T1 exosomes cultured for 24 hr versus 4T1 exosomes culture for 72 hr) (see Extended Experimental Procedures). (E) Scattterplots of miRNAs expression assessed by miRNA array, in exosomes cultured for 24 versus 72 hr of MCF10A, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, NMuMG and 4T1 cells. Pearson correlation coefficient, r, is used as a measure of the strength of the linear relationship between the two exosomes samples. miR-10a, miR-10b, miR-21, miR-27b, miR-155 and miR-373 are color-coded and identified in the scatterplots. (F) MCF10A, NMuMG, MCF7, MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 exosomes were resuspended in DMEM media FBS-depleted and maintained in cell-free culture for 24 and 72 hr. After 24 and 72 hr, exosomes were recovered and 6 miRNAs were quantified by qPCR. The fold-change of each miRNA in exosomes after 72 hr cell-free culture was quantified relative to the same miRNA in exosomes after 24 hr cell-free culture. The plots represent the fold-change for the miRNAs in exosomes harvested after 72 hr compared to those harvested after 24 hr. (G) Northern blots of miR-10b and miR-21 from normosomes after 24 and 72 hr of cell-free culture and cancer exosomes without culture and with 24, 72 and 96 hr of cell-free culture. The tRNAMet was used as a loading control. Quantification was done using Image J software.

qPCR data represented are the result of 3 independent experiments each with 3 replicates and are represented as ± SEM. Significance was determined using t tests (*p<0.05). See also Figure S1, Tables S1–6.

Cancer exosomes are specifically enriched in miRNAs

The global miRNA content of cancer exosomes and normosomes was investigated. A low correlation between the levels of expression of miRNAs in normosomes and cancer exosomes was observed (MCF10A vs MCF-7:r=0.56; MCF10A vs MDA-MB-231:r=0.39 and NMuMG vs 4T1:r=0.40) (Figure 1C), while correlation levels among normosomes and among cancer exosomes was generally higher despite their species differences (MCF10A vs NMuMG (normal exosomes):r=0.83; MDA-MB-231 vs 4T1:r=0.64; MDA-MB-231 vs MCF7:r=0.52 and MFC7 vs 4T1:r=0.55). We observed an overall enrichment of miRNAs in cancer exosomes (MCF7, MDA-MB-231 and 4T1) when compared with normosomes (MCF10A and NMuMG) (Figure 1C; Table S1–3). Interestingly, breast cancer exosomes derived from metastatic breast cancer cells, MDA-MB-231 and 4T1, show higher enrichment in miRNAs when compared to breast cancer exosomes derived from non-metastatic breast cancer cells, MCF7 (Figure 1C; Table S1–3). Enrichment of miRNAs in MDA-MB-231, MCF7 and 4T1 exosomes was not a mere reflection of an increase in total miRNAs in cancer cells, since these cancer cells actually exhibited a lower amount of total small RNAs when compared to non-tumorigenic cells (Figure S2A). MCF7, MDA-MB-231 and 4T1-derived exosomes exhibit an enrichment of miRNAs when compared to cells of origin (MCF7 exos vs MCF7 cells r=0.566; MDA-MB-231 exos vs MDA-MB-231 cells r=0.574; and 4T1 exos vs 4T1 cells 4=0.644). While MCF10A and NMuMG-derived exosomes reveal lower amounts of miRNAs when compared to the cells (MCF10A exos vs MCF10A cells r=0.425; NMuMG exos vs NMuMG cells r=0.4283) (Figure S2B).

We used a cell-free culture system to determine the expression of miRNAs in exosomes at different time points of culture. Purified exosomes were placed in FBS-depleted culture media and incubated for 24 and 72 hr at 37°C (see experimental procedures section in supplemental information for details). After the incubation period, exosomes were profiled by miRNA expression arrays (Figure 1D–E). Cancer exosomes cultured for 72 hr showed an enrichment of miRNAs when compared to cancer exosomes cultured for 24 hr (Figure 1D; Tables S4–6). On the contrary, normosomes did not show significant differences in miRNAs expression after 72 hr of culture (MCF10A:r=0.9145; NMuMG:r=0.9327; MCF7:r=0.5782; MDA-MB-231:r=0.5087; 4T1:r=0.4833; Figure 1E).

As proof of concept, a set of miRNAs (miR-10a, miR-10b, miR-21, miR-27a, miR-155 and miR-373) that were increased in cancer exosomes after 72h of culture were used for further analysis (Figure 1E). This set was selected because they were significantly up-regulated after 72 hr of culture and each has been extensively implicated in cancer progression (Figure S2C; see color-coded miRNAs in scatterplots; Tables S4–6). A striking up-regulation of the 6 analyzed miRNAs was observed exclusively in cancer exosomes cultured for 72 hr when compared to cancer exosomes cultured for 24 hr, with an average fold-change of 17.6 for MDA-MB-231-derived exosomes, 4.5 for MCF-7-exosomes and 13.2 for 4T1-derived cancer exosomes. (Figure 1F). In contrast, the miRNA content of normosomes was not significantly affected over time (Figure 1F).

When the miRNA content of MDA-MB-231, MCF-7 and 4T1 cancer exosomes was compared to that of normosomes from MCF10A and NMuMG cells, an enrichment was observed in all 6 miRNAs in cancer exosomes cultured for 24 hr with an average fold-change of 2.7, 1.7 and 2.0, respectively (Figure S2D). At the 72 hr time point, an average fold-change of 30, 4.5 and 18.2 was detected in the 6 miRNAs in MDA-MB231, MCF-7 and 4T1 derived cancer exosomes, respectively, when compared to MCF10A and NMuMG derived normosomes (Figure S2D). Northern blots confirmed the up-regulation of miR-10b and miR-21 exclusively in cancer exosomes, lending additional support to the miRNA array expression data and the qPCR analyses (Figure 1G).

Cancer exosomes contain pre-miRNAs and the core RLC proteins

The data suggested active miRNA biogenesis in exosomes. Therefore, the potential presence of pre-miRNAs in normosomes and cancer exosomes was explored. Cell-free culture of exosomes 24 or 72 hr after their isolation was performed and the exosomes subjected to RNAse treatment for the depletion of any possible extra-exosomal RNA. This was followed by the detection of the 6 pre-miRNAs in the exosomes corresponding to the mature miRNAs previously evaluated (Figure S2E).

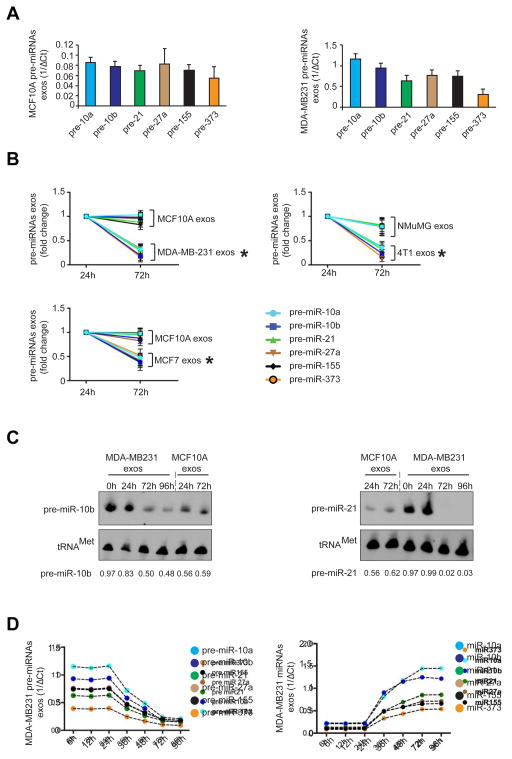

All 6 pre-miRNAs analyzed were present in exosomes (normosomes and cancer exosomes) (Figure 2A; Figure S2E). A significant down-regulation of pre-miRNAs was observed in cancer exosomes cultured for 72 hr when compared to cancer exosomes cultured for 24 hr. No variation of pre-miRNAs was observed in normosomes (Figure 2B). Down-regulation of pre-miRNAs in cancer exosomes was further confirmed by Northern blot for pre-miR10b and pre-miR21 (Figure 2C). Next, a time-course analysis of pre-miRNAs and miRNAs in exosomes was performed. We cultured isolated cancer exosomes for 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 72, 96 hr and observed that the levels of the 6 pre-miRNAs were inversely proportional to their respective miRNAs (Figure 2D). Mature miRNAs increased in quantity between 24 and 72 hr of culture, after which they reached a plateau (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Cancer exosomes get depleted of pre-miRNAs.

(A) Six pre-miRNAs were quantified by qPCR of MCF10A and MDA-MB231 exosomes. The inverse of the ΔCt value for each pre-miRNA was plotted. (B) Cancer exosomes and normosomes were resuspended in DMEM media depleted of FBS and maintained for 24 and 72 hr in cell-free culture conditions. After 24 and 72 hr exosomes were extracted and 6 pre-miRNAs were quantified by qPCR. Graphs show fold-change of each pre-miRNA in MCF10A and MDA-MB231 exosomes after 72 hr of cell-free culture relative to 24 hr cell-free culture. (C) Northern blots of pre-miR-10b and pre-miR-21 using MCF10A normosomes after 24 and 72 hr of cell-free culture, and MDA-MB231 cancer exosomes with 0, 24, 72 and 96 hr of cell-free culture. The tRNAMet was used as a loading control. Quantification was done using Image J software. (D) Pre-miRNAs (left graph) and mature miRNAs (right graph) of cancer exosomes (MDA-MB231) were quantified after 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 72 and 96 hr of cell-free culture conditions. The inverse of the ΔCt value for each pre-miRNA (left graph) and miRNA (right graph) at different time points was plotted.

The data presented are the result of 3 independent experiments each with 3 replicates and are represented as ± SEM; significance was determined using t tests (*p<0.05). Northern blots were performed once to validate qPCR and miRNAs array data. See also Figure S2.

To understand why the processing of pre-miRNAs in cultured exosomes is delayed by 24 hr, we monitored miR-21 and miR-155 in MDA-MB-231 cells that were silenced for exportin-5 (XPO5) (Figure S2F). XPO5 is responsible for the transport of pre-miRNAs from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (Yi et al., 2003). Silencing XPO5 prevents the flow of pre-miRNAs from the nucleus to the cytoplasm allowing for an evaluation of cytoplasmic pre-miRNA processing (Figure S2F–G). MicroRNA-21 and -155 were monitored in MDA-MB-231siXPO5 cells before and after centrifugation (Figure S2G), which occurred at 4°C for 3 hr to mimic the conditions of exosomes isolation (see experimental procedures section in supplemental information). Both miR-21 and miR-155 present a lag phase of processing in centrifuged cells (Figure S2G). For the cells to accomplish a 2 fold increase of miR-21, 8 hr are enough while centrifuged cells take about 24 hr for the same fold increase (Figure S2G). The same holds true for mir-155 that takes about 10 hr to reach 2 fold increase while centrifuged cells take 27 hr for the same fold increase (Figure S2G). Therefore, exosomes require a certain period of acclimatization that is already expected for recovery of enzymatic activities in cultured cells after tissue culture passage.

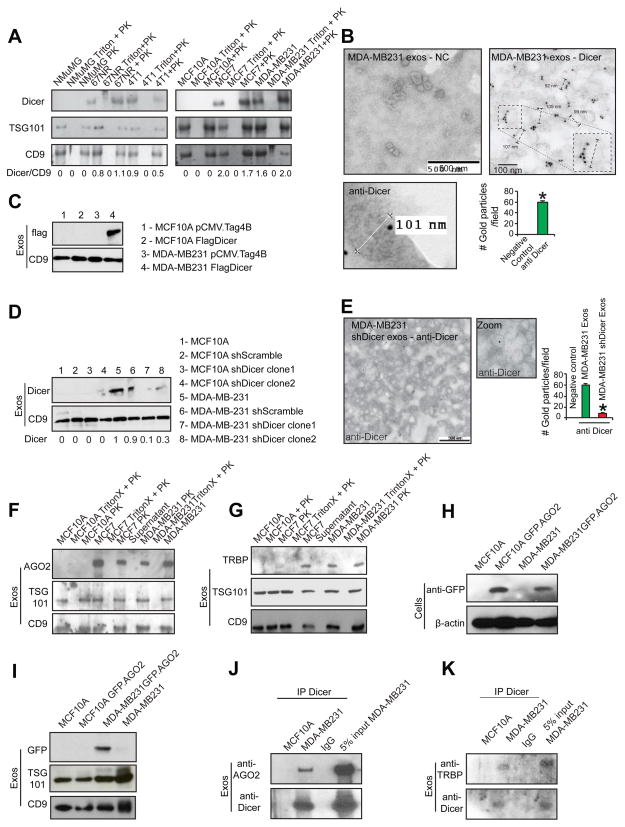

MicroRNA biogenesis requires key protein components of the RLC, Dicer, TRBP, and AGO2 (Chendrimada et al., 2005). Dicer and TRBP form a complex that stabilizes Dicer, while AGO2 is recruited later in the biogenesis pathway for strand selection and the RNA unwinding process (Chendrimada et al., 2005). Dicer was detected in exosomes derived from MCF7, MDA-MB231, 67NR, and 4T1 cells (Figure 3A–B; Figure S3A). All exosomes preparations were treated with proteinase K before exosomal protein extraction, as previously described (Montecalvo et al., 2012) (Figure 3A–B; Figure S3A). Dicer was not detected in normosomes produced by MCF10A and NMuMG cells (Figure 3A; Figure S3A). Immunogold labeling of exosomes using TEM confirmed that Dicer was present in cancer exosomes, but not in normosomes (Figure 3B; Figure S3B). The use of an anti-GFP antibody as negative control failed to detect any gold particles by immunogold TEM (Figure S3C).

Figure 3. Cancer exosomes contain RLC proteins.

(A) Immunoblot of Dicer in exosomes harvested from: NMuMG, MCF10A, MCF7, MDA-MB-231, 67NR and 4T1 cells. Controls used were: exosomes treated with TritonX followed by proteinase K treatment (Triton + PK); and exosomes treated with proteinase K (PK). Immunoblots for TSG101 (second row) and CD9 (third row) are shown. Quantification is the ratio of Dicer and CD9 intensity bands as quantified by Image J software. (B) TEM of immunogold of Dicer in MDA-MB-231 exosomes. Right image contains zoomed inset to show labeling in one exosomes with diameter of 103 nm. Left bottom image is digitally zoomed from a new independent image of the extraction. Negative control (NC) refers to secondary antibody. Gold particles are depicted as black dots. Right lower graph represents the average number of gold dots in 10 different fields of each of the two samples on the top. (C) Immunoblot for flag (upper panel) in MCF10A and MDA-MB231 exosomes harvested from cells transfected with empty vector (pCMV-Tag4B; first and third lanes respectively) and Flag-Dicer vector (second and fourth lanes). CD9 immunoblot was used as a loading control (lower panel). (D) Immunoblot for Dicer in exosomes extracted from MCF10A and MDA-MB231 parental cells and cells transfected with shScramble and shDicer plasmids (upper blot). CD9 immunoblot was used as a loading control (lower blot). Immunoblot quantification was done using Image J software. (E) TEM of immunogold of Dicer in cancer exosomes derived from MDA-MB231shDicer cells. Gold particles are depicted as black dots. Right graph represents the average number of gold dots in 10 different fields of the same sample. (F) Immunoblot of AGO2 in exosomes harvested from MCF7, MDA-MB231 and MCF10A cells. Controls used were: exosomes treated with Triton X followed by proteinase K (Triton X + PK); exosomes treated with proteinase k (PK); and supernatant after ultracentrifugation to harvest exosomes (Supernatant). Immunoblots of TSG101 (second row) and CD9 (third row) are shown. (G) Immunoblot of TRBP in exosomes harvested from MCF7, MDA-MB231 and MCF10A cells. The controls used were: exosomes treated with Triton X followed by proteinase K (Triton X + PK); exosomes treated with proteinase K (PK); and supernatant after ultracentrifugation to harvest exosomes (Supernatant). TSG101 (second row) and CD9 (third row) immunoblots were used as exosomes markers. (H) Immunoblot of GFP in MCF10A and MDA-MB231 cells transfected with GFP-AGO2 plasmid (upper panel). Beta actin was used as loading control (lower panel). (I) Immunoblot of GFP antibody in exosomes extracted from MCF10A and MDA-MB231 cells transfected with GFP-AGO2 plasmid (upper panel). TSG101 (middle panel) and CD9 (lower panel) were used as loading controls. (J) Immunoblot of AGO2 in exosomal proteins extracted from MCF10A and MDA-MB231 cells immunoprecipitated with Dicer antibody or IgG (upper panel). 5% of the lysate input of MDA-MB-231 exosomes was used as control. Immunoblot of Dicer was used as control for immunoprecipitation (lower panel). (K) Immunoblot of TRBP antibody in exosomal proteins extracted from MCF10A and MDA-MB231 cells immunoprecipitated with Dicer antibody or IgG (upper panel). Lysate input of MDA-MB-231 exosomes (5%) was used as control. Immunoblot of Dicer was used as control for immunoprecipitation (lower panel).

Data are represented as meanlot of See also Figure S3.

Dicer was overexpressed with an N-terminal Flag tag in MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure S3D). Immunoblot and confocal microscopy localized the Flag-Dicer protein specifically to cancer exosomes (Figure 3C; Figure S3D–E). In addition, Dicer expression was decreased via stable expression of two short-hairpin constructs in MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 cells (Figure S3F–G). Exosomes derived from MDA-MB-231shDicer cells contained significantly less Dicer compared to shScramble or parental MDA-MB-231 cells as determined by immunoblot and immunogold TEM (Figure 3D–E). Dicer was not detected in normosomes derived from MCF10AshDicer cells (Figure 3D).

RLC proteins, AGO2, and TRBP, were also present in cancer exosomes, but not in normosomes (Figure 3F–G). Exosomes were extracted from MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with a GFP-tagged AGO2 (Figure 3H). The presence of GFP-AGO2 was detected in exosomes extracted from MDA-MB-231-GFP-AGO2 cells (Figure 3I). Dicer immunoprecipitation revealed that AGO2 binds to Dicer in cancer exosomes, while both are undetectable in normosomes (Figure 3J). TRBP functions as a key partner of Dicer protein and aids in its stability and in its pre-miRNA cleavage activity (Chendrimada et al., 2005; Melo et al., 2009). Dicer immunoprecipitation revealed the presence of Dicer/TRBP complex in cancer exosomes, but not in normosomes (Figure 3K).

Multivesicular bodies (MVBs) are cellular organelles that contain endosomes that are released as exosomes upon fusion with the plasma membrane (Pant et al., 2012). We compared the cellular distribution of Dicer in conjunction with markers of MVBs and exosomes biogenesis pathway. Hrs and BiG2 are early endosome markers and TSG101 is a marker for MVBs (Razi and Futter, 2006; Shin et al., 2004). Dicer co-localized with Hrs, BiG2 and TSG101 in MDA-MB231 and 4T1 cells (Figure S3H). Exogenously delivered N-rhodamine-labelled phosphotidylethanolamine (NRhPE) is taken up by cells and retained within MVBs (Sherer et al., 2003). Dicer labeling in MDA-MB-231 cells co-localized with NRhPE in MVBs (Figure S3H). This data is in agreement with previous observations were Dicer, TRBP and AGO2 appeared in late endosomes/MVB fractions in co-fractionation analysis (Shen et al., 2013). In contrast, there was no co-localization of Dicer with Hrs, BiG2, TSG101, or NRhPE in MCF10A cells (Figure S3H). Further, HRS, TSG101 and BIG2 genes were silenced using two different siRNAs and shRNAs in MDA-MB-231 and MCF10A cells, and Dicer protein expression was evaluated (Figure S3I). Silencing HRS, BIG2, and TSG101 impaired MVBs formation and led to significant down-regulation of exosomes production (Figure S3J). Increased Dicer protein was observed in the nucleus and cytoplasm, including MVBs, of MDA-MB-231 cells with siHRS, shBIG2 or siTSG101 (Figure S3K). Silencing of HRS, BIG2, or TSG101 genes in MCF10A cells did not alter Dicer protein expression or cellular localization (Figure S3K).

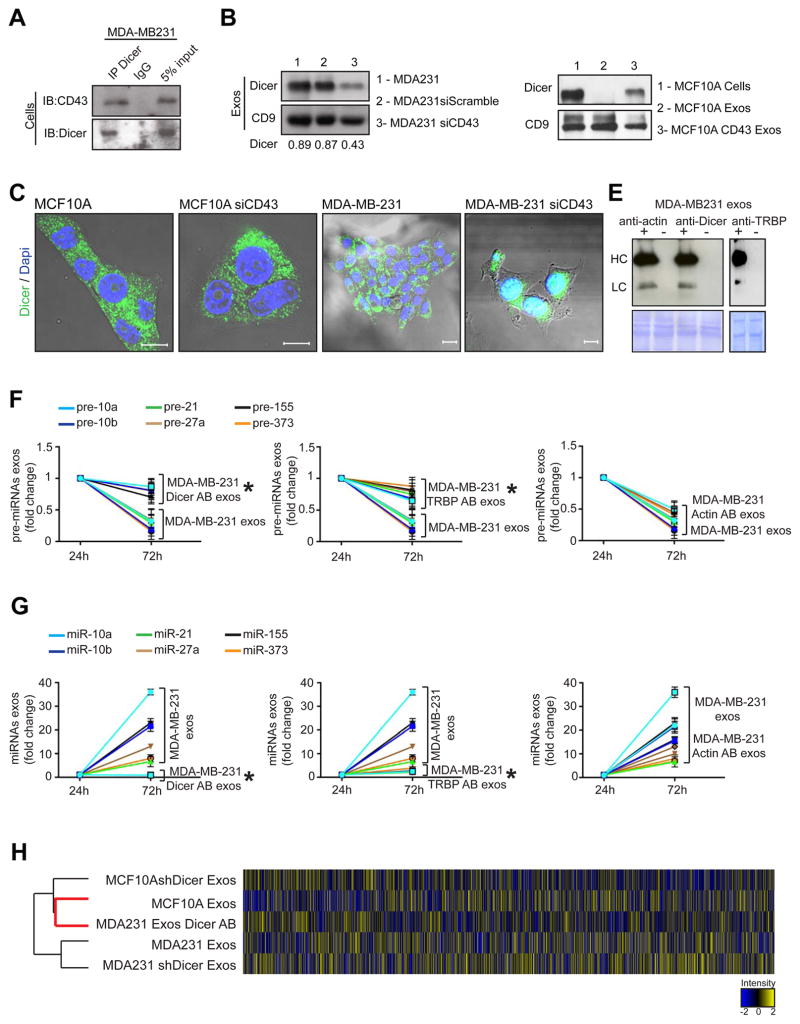

Recently, a variety of plasma membrane anchor proteins, such as CD43, were speculated as likely mediators of protein transport into MVBs and exosomes (Shen et al., 2011). CD43 is predominantly a leukocyte transmembrane sialoglycoprotein, which is aberrantly expressed highly in the cytoplasm of breast cancer cells but not in normal epithelial cells (Tuccillo et al., 2014). CD43 is also detected in many solid tumors including breast cancer, and correlates with cancer progression and metastasis (Tuccillo et al., 2014). We demonstrate that Dicer immunoprecipitates with CD43 in MDA-MB231 cells (Figure 4A). When CD43 is silenced using siRNA in MCF10A and MDA-MB231 cells, Dicer levels significantly decrease in cancer exosomes and reveal an increased nuclear and cytoplasmic accumulation of Dicer protein (Figure 4B–C). When CD43 is overexpressed in MCF10A cells (MCF10A-CD43 cells) Dicer is detected in normosomes (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Cancer exosomes process pre-miRNAs to generate mature miRNAs.

(A) Immunoblot for CD43 and Dicer in MDA-MB-231 cell lysates immunoprecipitated with Dicer antibody and IgG. (B) Immunoblot of Dicer in MDA-MB-231siCD43 exosomes. CD9 was used as a loading control and quantification achieved by Image J software. (C) Dicer expression in MCF10A and MDA-MB-231 cells (first and third panels) compared to MCF10A and MDA-MB231siCD43 cells (second and fourth panels). Scale bars 20 μm (two left images) and 10 μm (two right images). (D) Immunoblot of Dicer in MCF10A exosomes (2), exosomes derived from MCF10A cells overexpressing CD43 (3) and MCF10A cells (1). CD9 was used as a loading control. (E) Immunoblot using anti-rabbit and anti-mouse secondary antibody to detect heavy chain (HC) and light chain (LC) primary Dicer, Actin or TRBP antibodies electroporated in exosomes of MDA-MB231 cells. Electroporated exosomes without antibody derived from MDA-MB231 cells were used as negative control. Proteinase K treatments were performed after electroporation. (F) MDA-MB-231 exosomes were harvested in quadruplicate. Samples were electroporated with anti-Dicer, anti-actin, or anti-TRBP antibodies. The 3 samples plus control were left in cell-free culture conditions (FBS-depleted) for 24 and 72 hr. After 24 and 72 hr exosomes were extracted and the 6 pre-miRNAs were quantified by qPCR. The fold-change of each pre-miRNA in exosomes after 72 hr cell-free culture was quantified relative to the same pre-miRNA in exosomes after 24 hr cell-free culture in each sample. The graphical plots represent the fold change of the 6 pre-miRNAs. (G) MDA-MB-231 exosomes were harvested in quadruplicate. Samples were electroporated with anti-Dicer, anti-actin, or anti-TRBP antibodies. The 3 samples plus control were left in cell-free culture conditions (FBS-depleted) for 24 and 72 hr. After 24 and 72 hr exosomes were extracted once again and the 6 miRNAs were quantified by qPCR. The fold-change of each miRNA in exosomes after 72 hr cell-free culture was quantified relative to the same miRNA in exosomes after 24 hr cell-free culture in each sample. The graphical plots are a representation of the fold change of the six miRNAs. (H) HeatMap of miRNAs array MDA-MB-231 exos, exosomes electroporated with Dicer Antibody (MDA231 exos Dicer AB), MCF10A exosomes, MDA-MB-231 shDicer Exosomes and MCF10AshDicer Exosomes. An average of duplicates is represented for each sample.

The qPCR data are the result of 3 independent experiments each with 3 replicates and are represented as ± SEM; significance was determined using t tests (*p<0.05). See also Figure S4 and Table S7.

Cancer exosomes process pre-miRNAs to generate mature miRNAs

Next, we examined the ability of RLC proteins in cancer exosomes to generate mature miRNA. Exosomes with suppressed Dicer levels were extracted from the MCF10AshDicer, MDA-MB-231shDicer and 4T1shDicer cells (Figure S4A). The capacity to generate exosomes was not altered upon Dicer down-regulation in cells (Figure S4B). Dicer-suppressed exosomes did not show any significant changes in pre-miRNAs and miRNAs content at 24 72 hr of culture (Figure S4C). Next, anti-Dicer and anti-TRBP antibodies were delivered into cancer exosomes by electroporation, and compared to cancer exosomes and normosomes electroporated with an anti-actin control antibody. The exosomes were treated with proteinase K after electroporation to eliminate the possibility of antibodies associated with outer surface of exosomes (Figure 4E). Cancer exosomes electroporated with the control anti-actin antibody showed the same variations in pre-miRNA and miRNA levels as previously mentioned (Figure 4F–G). However, in cancer exosomes with anti-Dicer and anti-TRBP antibody, insignificant changes in the levels of pre-miRNA and miRNA were observed with time, suggesting an inhibition of pre-miRNA processing (Figure 4F–G). Total miRNA content was also assessed by miRNA expression array analysis of MDA-MB-231 exosomes (MDA231 Exos), anti-Dicer antibody electroporated MDA-MB-231 exosomes (MDA231 Exos Dicer AB), MDA231 shDicer Exos, MCF10AshDicer Exos and MCF10A Exosomes after 72 hr of cell-free culture (Figure 4H). The total miRNA content of cancer exosomes with anti-Dicer antibody more closely resembled MCF10A normosomes (r=0.94) when compared to cancer exosomes (r=0.67) (Figure 4H). When comparing cancer exosomes with cancer exosomes containing anti-Dicer antibody, 198 differentially expressed miRNAs were observed, 48% of which were significantly down-regulated (Table S7). Further data mining showed that 19% of miRNAs were oncogenic, while only 1% possessed tumor-suppressive properties (Figure S4E; Table S7).

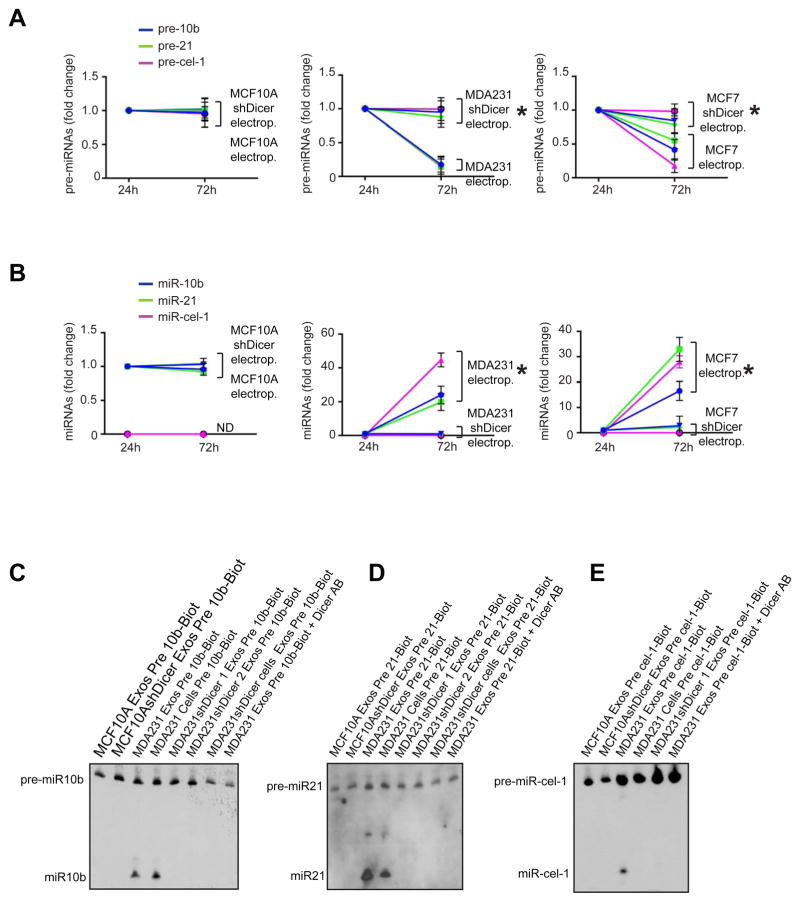

To further confirm the specific pre-miRNA processing capability of cancer exosomes, synthetic pre-miRNAs -10b and -21, as well as the C.elegans precursor pre-cel-1 pre-miRNA, were electroporated into exosomes (Figure S5A). We observed significant down-regulation of the pre-miRNAs and up-regulation of their respective miRNAs in cancer exosomes after 72 hr culture (Figure 5A–B). Cancer exosomes derived from shDicer cells did not reveal a difference in pre-miRNA content after 72 hr culture (Figure 5A). Additionally, pre-miR-10b, -21 and –cel-1 were internally labeled with biotin-deoxythymidine (dT). The dT-modified pre-miRNAs were processed into mature miRNAs when transfected into MCF10A cells (Figure S5B–C). The modified pre-miRNAs were used in ‘dicing’ assays to show that Dicer-containing cancer exosomes were specifically capable of processing pre-miRNA and generate miRNAs (Figure 5C–E).

Figure 5. Cancer exosomes process pre-miRNAs to generate mature miRNAs.

(A) Synthetic pre-miRNAs -10b, -21 and –cel-1 were electroporated into exosomes from MCF10A (MCF10A electrop.), MCF10AshDicer (MCF10AshDicer electrop.), MDA-MB231 (MDA-MB231 electrop.), MDA-MB231shDicer (MDA-MB231shDicer electrop.), MCF-7 (MCF7 electrop.) and MCF-7shDicer (MCF7 shDicer electrop.) cells. Exosomes were recovered after cell-free culture conditions (FBS-depleted) for 72 hr. Pre-miR-10b, -21 and –cel-1 were quantified by qPCR before and after 72 hr of electroporation and culture. The plots represent the fold-change of pre-miR-10b, -21 and –cel-1 72 hr after electroporation relative to 24 hr after electroporation. (B) Synthetic pre-miRNAs -10b, -21 and –cel-1 were electroporated into exosomes harvested from the same cells as in (A). Exosomes were recovered after cell-free culture conditions (FBS-depleted) for 72 hr. MiR-10b, -21 and –cel-1 were quantified by qPCR before and after 72 hr of electroporation and culture. Plots represent the fold-change of miR-10b, -21 and cel-1 72 hr after electroporation relative to 24 hr after electroporation. (C) Northern blot without detection probe, using samples from dicing assay. Synthetic pre-miR-10b internally labeled with biotin was used for the dicing assay. Samples used were MCF10A, MCF10AshDicer, MDA-MB231 exosomes, MDA-MB231shDicer clone1 and clone2 exosomes, MDA-MB231shDicer cells and MDA-MB231 exosomes electroporated with Dicer antibody. (D) Northern blot without detection probe, using samples from dicing assay. Synthetic pre-miR-21 internally labeled with biotin was used for the dicing assay. Samples used were MCF10A, MCF10AshDicer, MDA-MB231 exosomes, MDA-MB231shDicer clone1 and clone2 exosomes, MDA-MB231shDicer cells and MDA-MB231 exosomes electroporated with Dicer antibody. (E) Northern blot without detection probe using samples from dicing assay. Synthetic pre-cel-miR-1 internally labeled with biotin was used for the dicing assay. Samples used were the same ones as in (D).

The qPCR data are the result of 3 independent experiments each with 3 replicates and are represented as ± SEM. See also Figure S5.

Cancer exosomes induce tumor formation in a Dicer-dependent manner

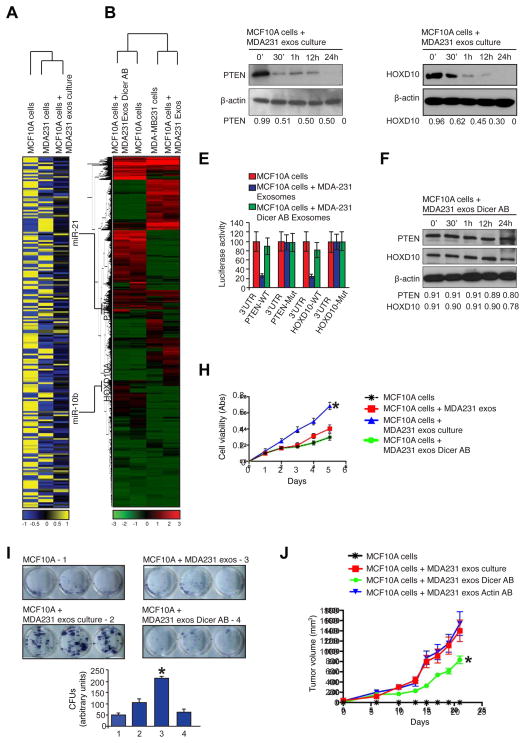

MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with CD63-GFP, an exosomes marker (Escola et al., 1998). MDA-MB-231 cells with CD63-GFP were used to isolate GFP+ cancer exosomes, which were subsequently incubated with MCF10A cells. Fluorescence NanoSight detected green exosomes from MDA-MB231-CD63-GFP cells (Figure S6A). The green CD63-GFP+ cancer exosomes entered MCF10A cells and localized in the cytoplasm (Figure S6B). Using miRNA expression arrays, we show that MCF10A cells co-incubated with MDA-MB-231-derived cancer exosomes acquire a distinct miRNA expression profile (Figure 6A). mRNA expression profiling reveals pronounced global transcriptome changes in MCF10A cells treated with cancer exosomes compared to MCF10A cells treated with cancer exosomes with Dicer antibody (MCF10A cells + MDA-MB-231 Exos Dicer AB; Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Cancer exosomes induce transcriptome alterations in recipient cells and tumor formation in a Dicer-dependent manner.

(A) HeatMap of miRNA expression array of MDA-MB231 cells, MCF10A cells and MCF10A cells treated with MDA-MB231 exosomes. An intensity key is given below the HeatMap. Each sample is represented as an average of the duplicates. (B) HeatMap of mRNA expression arrays representing gene abundance. The samples used were MCF10A cells treated with MDA-MB231 exosomes electroporated with Dicer antibody, MCF10A cells, MDA-MB231 cells and MCF10A cells exposed to MDA-MB231 exosomes. An intensity key is given below the HeatMap. (C) Immunoblot of PTEN in protein extracts of MCF10A cells treated for 0, 30 min, 1, 12 and 24 hr with MDA-MB231 cancer exosomes after cell-free culture. Beta actin was used as a loading control. (D) Immunoblot of HOXD10 antibody in protein extracts of MCF10A cells treated for 0, 30 min, 1, 12 and 24 h with MDA-MB231 cancer exosomes after cell-free culture conditions. Beta actin was used as a loading control. (E) Graph showing luciferase reporter activity in MCF10A cells transiently transfected with 3′UTR-PTEN-WT, 3′UTR-PTEN-Mut, 3′UTR-HOXD10-WT and 3′UTR-HOXD10-Mut and treated with MDA-MB231 exosomes. (F) Immunoblot of PTEN (upper panel) and HOXD10 (middle panel) in protein extracts from MCF10A cells treated for 0, 30 min, 1, 12 and 24 hr with MDA-MB-231 exosomes electroporated with Dicer antibody after cell-free culture conditions. Beta actin was used as a loading control. (G) MTT assay during 5 days of culture of MCF10A cells, MCF10A cells treated with MDA-MB231 exosomes with no cell-free culture time, MCF10A cells treated with MDA-MB231 exosomes with cell-free culture time and MCF10A cells treated with MDA-MB231 exosomes electroporated with Dicer antibody with cell-free culture time; significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc analysis (* p=0.0027). (H) The colony formation assay shows formation of colonies in culture plate and labeled with MTT reagent after 8 days MCF10A cells culture, MCF10A cells treated with MDA-MB231 exosomes with no cell-free culture time, MCF10A cells treated with MDA-MB231 exosomes with cell-free culture time and MCF10A cells treated with MDA-MB231 exosomes electroporated with Dicer antibody with cell-free culture time. Lower graph show quantification of colonies (CFUs – colony forming units). Significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc analysis (*p=0.0003) (I) MCF10A cells, MCF10A cells exposed to MDA-MB-231 cancer exosomes, MCF10A cells exposed to MDA-MB231 cancer exosomes electroporated with Dicer antibody and MCF10A cells exposed to MDA-MB231 cancer exosomes electroporated with Actin antibody were orthotopically injected into the mammary pads of athymic nude mice (n=8 per group). Graph depicts tumor volume with respect to time; significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc analysis (*p=0.005).

Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S6.

A cross-comparison analysis of the miRNA and mRNA expression profiles of MCF10A cells exposed to MDA-MB-231 cancer exosomes and parental MCF10A cells revealed a correlation between 108 of the up-regulated miRNAs and a down-regulation of their mRNA targets (Figure 6A–B). For example, miRNA-21 and -10b were up-regulated (4.6 and 2.3 fold, respectively) in cancer exosomes-treated MCF10A cells. MicroRNA-21 and -10b have been implicated in breast cancer progression and metastasis (Ma et al., 2007; Yan et al., 2011). As shown earlier, miR-21 and -10b are synthesized in cancer exosomes from their pre-miRNAs (Figure 1F-G; Figure 2C–D). PTEN and HOXD10 are known targets for miR-21 and miR-10b, respectively, and both genes were suppressed in the expression array analysis of MCF10A cells treated with cancer exosomes when compared to control MCF10A cells (Figure 6B). Immunoblots of PTEN and HOXD10 showed they were suppressed in MCF10A cells exposed to cancer exosomes (Figure 6C–D). MCF10A cells were transiently transfected with luciferase reporters containing the WT 3′UTR of PTEN or HOXD10 genes that are capable of binding miR-21 and miR-10b. Mutant 3′UTR of PTEN or HOXD10 vectors were used as controls. A decrease in luciferase reporter activity was seen in MCF10A cells incubated with cancer exosomes, confirming functional delivery of miRNAs from cancer exosomes to recipient cells (Figure 6E). PTEN and HOXD10 protein levels were evaluated in MCF10A cells incubated with cancer exosomes at different time points. A significant decrease was detected in PTEN and HOXD10 protein immediately after treating the cells with 72 hr cultured cancer exosomes (Figure 6C–D). PTEN and HOXD10 protein levels changed minimally in MCF10A cells treated with freshly isolated cancer exosomes, suggesting that sufficient concentration of the mature miRNAs is not present at this time point (Figure S6C–D). MCF10A cells treated with 72 hr-cultured cancer exosomes with Dicer antibody revealed an insignificant down-regulation of PTEN and HOXD10 (Figure 6F). Additionally, processing of miR-15 in cells, a miRNA not detected in MDA-MB231-derived cancer exosomes, was not altered due to treatment of MCF10A cells with MDA-MB-231 exosomes containing Dicer antibody (Figure S6E). Some reports show down-regulation of miRNA targets in cells incubated with exosomes without a need for culture (Kosaka et al., 2013; Narayanan et al., 2013; Pegtel et al., 2010). MiR-182-5p is one of the miRNAs up-regulated in MCF10A cells upon cancer exosomes incubation. SMAD4, a miR-182-5p target (Hirata et al., 2012), is one of the genes down-regulated upon cancer exosomes treatment of MCF10A cells (Figure S6F). Up-regulation of miR-182-5p in cancer exosomes during the culture period was not observed and pre-miR182-5p was not detected in cancer exosomes (Figure S6G). Therefore, cancer exosomes also pack mature miRNAs without the need for processing pre-miRs. If such mature miRs are present in stoichiometric amounts, they may be able to regulate gene expression of recipient cells, as shown previously (Ismail et al., 2013; Kogure et al., 2011; Kosaka et al., 2013; Narayanan et al., 2013; Pegtel et al., 2010; Valadi et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2010).

Cell viability and proliferation of MCF10A cells treated with 72 hr cultured cancer exosomes was increased, which was not observed when freshly isolated cancer exosomes were used (Figure 6G). No changes were seen after incubation of MCF10A cells with cancer exosomes containing Dicer antibodies (Figure 6G). The same held true for the colony formation capacity of MCF10A cells treated with cancer exosomes (Figure 6H).

To address the functional ‘oncogenic potential’ of MCF10A and MCF10A cells with prior exposure to cancer exosomes (MCF10A cells + MDA231 exos culture), we implanted the cells into the mammary fat pads of female nu/nu mice. Similar to results previously published, MCF10A cells did not form tumors in nude mice (Mavel et al., 2002; Thery et al., 2002) (Figure 6I). MCF10A cells co-injected with cancer exosomes formed tumors, whereas MCF10A cells co-injected with cancer exosomes containing Dicer antibody (but not control anti-actin antibodies) showed a significant reduction in tumor growth (Figure 6I; Figure S6H). These results suggest that Dicer in cancer exosomes contributes to oncogenic conversion of MCF10A cells (Figure 6G–I).

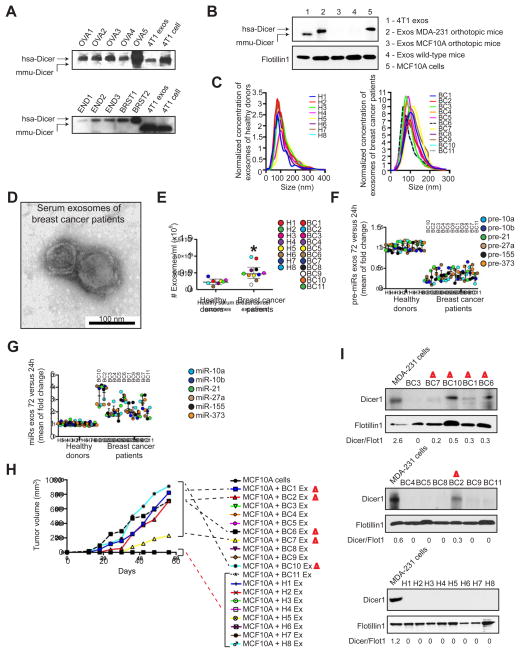

Serum exosomes from cancer patients contain Dicer and process pre-miRNAs to generate mature miRNAs

Freshly isolated human primary ovarian, breast, and endometrial tumor fragments were orthotopically grafted onto the appropriate organs of female athymic nu/nu mice (Figure S7A–B) and serum exosomes from these mice were evaluated by TEM (Figure S7C). Size exclusion immunoblot of the exosomes extracts demonstrated the existence of Dicer exclusively of human origin in the purified exosomes (hsa-Dicer) (Figure 7A; Figure S7D). Protein extracts from 4T1-derived exosomes were used as controls to show that Dicer of mouse origin exhibited a different molecular size (mmu-Dicer) (Figure 7A). Additionally, serum exosomes from nude mice orthotopically injected with MDA-MB-231 cells or MCF10A cells show Dicer protein of human origin in MDA-MB-231-injected mice while no protein is detected in serum exosomes of MCF10A-injected mice or non-injected mice (Figure 7B). This strongly supports the fact that Dicer in exosomes is exclusively originated from the human cancer epithelial cells injected into mice.

Figure 7. Serum from breast cancer patients contain Dicer and process pre-miRNAs.

(A) Immunoblot of Dicer and protein extracts from serum exosomes harvested from mice xenografted with human tumors. OVA1-5 are human ovary xenografts; END1-3 are human endometrial xenografts; and BRST1 and 2 are human breast xenografts. 4T1 exosomes and cells were used as controls for murine Dicer. hsa-Dicer represents human Dicer molecular weight and mmu-Dicer represents murine Dicer molecular weight. See Figure S7D (B) Immunoblot of Dicer, that recognizes human and mouse Dicer, and protein extracts from serum exosomes harvested from mice orthotopically implanted with MDA-MB-231 cells or MCF10A cells. 4T1 exosomes and MCF10A cells were used as controls for murine and human Dicer, respectively. hsa-Dicer represents human Dicer molecular weight and mmu-Dicer represents murine Dicer molecular weight. (C) NanoSight shows size distribution of exosomes extracted from the serum of 8 healthy donors (left graph) and 11 breast cancer patients (right graph). Concentration of samples was standardized to better show size. (D) TEM of exosomes harvested from the serum of breast cancer patients (100 μl of serum). (E) Concentration of exosomes from the serum of 8 healthy donors and 11 breast cancer patients assessed by NanoSight. Significance was determined using T test (*p=0.012). (F) Exosomes were harvested from fresh serum of 8 healthy donors and 11 breast cancer patients. The extracted samples were left in cell-free culture conditions for 24 and 72 hr. After 24 and 72 hr, exosomes were recovered and 6 pre-miRNAs were quantified by qPCR. The fold-change of each pre-miRNA in exosomes after 72 hr cell-free culture was quantified relative to the same pre-miRNA in exosomes after 24 hr cell-free culture in each sample. The graphical dot plots represent an average fold-change for the pre-miRNAs in 72 hr exosomes relative to 24 hr exosomes. (100 μl of serum) (G) Exosomes were harvested from fresh serum of 8 healthy donors and 11 breast cancer patients. The extracted samples were left in cell-free culture conditions for 24 and 72 hr. After 24 and 72 hr, exosomes were recovered and 6 miRNAs were quantified by qPCR. The fold-change of each miRNA in exosomes after 72 hr cell-free culture was quantified relative to the same miRNA in exosomes after 24 hr cell-free culture in each sample. The graphical dot plots represent an average fold-change for the miRNAs in 72 hr exosomes relative to 24 hr exosomes. Both panels F and G are the result of three independent qPCRs each with three replicates. (100 μl of serum) (H) MCF10A cells, MCF10A cells mixed with exosomes from healthy donors (H1-8) and MCF10A cells mixed with exosomes from breast cancer patients (BC1-11) were orthotopically injected into the mammary pads of athymic nude mice. The number of exosomes used was calculated per body weight. Samples that have not formed a tumor appear overlapped in the x-axis of the graph. Exosomes alone were injected in all cases. This graph depicts tumor volume with respect to time. (n=2 per sample) (I) Immunoblots of Dicer in protein extracts from the serum exosomes harvested the 11 breast cancer patients and 8 healthy donors using Flotillin1 blot as loading control. Quantification was done using Image J software. Samples highlighted in the immunoblot are the ones that showed tumor formation when injected with MCF10A cells in nude mice (panel H).

Data are represented as mean ± SEM. See also Figure S7.

Next, 100 μl of fresh serum samples were used to isolate exosomes from 8 healthy individuals (H) and 11 patients with breast carcinoma (BC) (Figure 7C). Exosomes were 100 nm (average of the mode for the size distributions) and their lipid bilayer membranes were identified by TEM (Figure 7C–D). Serum of breast cancer patients contained significantly more exosomes when compared to serum of healthy donors (Figure 7E). When equal number of exosomes were placed in culture for 24 and 72 hr, the 6 pre-miRNAs (vide supra) were found to be down-regulated exclusively in breast cancer patients and their respective mature miRNAs were up-regulated after 72 hr of culture (Figure 7F–G). Next, exosomes alone or combined with MCF10A cells were injected orthotopically in the mammary fat pad of female nu/nu mice. We noted that 5 out of 11 serum exosomes induced MCF10A cells to form tumors (Figure 7H). In contrast, when exosomes from healthy donors were combined with MCF10A cells or administered alone, tumors were not detected (Figure 7H). Interestingly, exosomes that formed tumors were also shown to have the highest increase in the amount of mature miRNAs after 72 hr culture (Figure 7F–G). Exosomes from serum of breast cancer patients and healthy donors were analyzed for Dicer expression. Dicer protein in exosomes was observed mainly in breast cancer samples that formed tumors in nude mice when co-injected with MCF10A cells and not in exosomes from serum of healthy individuals (Figure 7I).

DISCUSSION

The functional role of miRNAs associated with exosomes in cancer progression is largely unknown. Many studies suggest the presence of miRNAs in exosomes and speculated on their function (Valadi et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2010). Given that miRNAs need to be present in a stoichiometric concentration for appropriate silencing of mRNA targets, it seems unlikely that exosomes in circulation would provide sufficient concentrations of mature miRNAs to repress the target transcriptome. The processing of the pre-miRNAs originated from exosomes in the recipient cells is an unlikely event because miRNA biogenesis in recipient cells is rate-limiting not only due to the total amount of pre-miRNAs available for processing in the receiving cell, but also due to rate-limiting amounts of required enzymes. Therefore, it is more efficient to have mature miRNAs entering recipient cells for direct alteration of gene expression post-transcriptionally without having to go through a processing pathway. We demonstrated that inhibiting the action of Dicer in cancer exosomes significantly impairs tumor growth in recipient cells, suggesting that miRNA biogenesis in exosomes contributes to cancer progression.

Recent studies show that melanoma-derived exosomes play a role in metastasis (Peinado et al., 2012). Exosomes derived from fibroblasts play a role in the migration of breast cancer cells (Luga et al., 2012). Exosomes derived from cancer cells have a pro-tumorigenic role associated with the transfer of mRNA and pro-angiogenic proteins (Luga et al., 2012; Peinado et al., 2012; Skog et al., 2008). Exosomes derived from cancer cells can also contribute to a horizontal transfer of oncogenes, such as EGFRvIII (Al-Nedawi et al., 2008). Our study demonstrates that cancer exosomes mediate significant transcriptome alterations in target cells via RISC-associated miRNAs. A myriad of biological processes in the target cells are affected by exosomes that induce proliferation and have the potential to convert non-tumorigenic cells into tumor-forming cells. Nonetheless, the potential in vivo effect of cancer exosomes on recipient cells likely depends on several other environmental parameters and accessibility barriers. Collectively, this study unravels the possible role cancer exosomes play in inducing an oncogenic “field effect” that further subjugates adjacent normal cells to participate in cancer development and progression. This study does not indicate that such field effect is systemic; therefore additional studies may be required to address such implications.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES SUMMARY

Exosomes were purified from cells cultured in exosomes-depleted FBS, using sequential centrifugations to discard dead cells and cellular debris. All exosomes samples were subjected to a PBS washing step followed by ultracentrifugation. This was followed by filtration of the supernatant with 0.2 μm filters and ultracentrifugation for 2 hr, as previously described (Li et al., 2012; Luga et al., 2012). Exosomes used for RNA extraction were treated with Proteinase K and RNase prior to lysis of exosomes. Exosomes for protein extraction were treated with Proteinase K and Urea/SDS lysis buffer.

Human Samples

Human serum samples were obtained from the MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) through appropriate informed consents after approval by the institutional review board (IRB). The IRB protocol numbers are: 04-0657 and 04-0698. The primary tumor specimens were obtained at the Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge (L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain). The Institutional Review Board approved the study. Written informed consent was collected from patients (see Supplemental Information).

Animal Studies

All mice were housed under standard housing conditions at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) and IDIBELL animal facilities. All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the BIDMC, MDACC and the Spanish Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees (see Supplemental Information).

Statistical Analysis

Error bars indicate ±SEM between biological replicates. Technical as well as biological triplicates of each experiment were performed. Statistical significance was determined using t tests, except for multiple-group comparisons, for which significance was determined using one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc analysis with GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software). A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Pearson correlation coefficient (r value) was calculated assuming linear relationship between variables.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1, Related to Figure 1. Cancer exosomes become enriched in miRNAs

(A) Photograph of PKH26 stained exosomes, at the bottom of the ultracentrifugation tube. (B) Immunoblot for exosomes markers TSG101, CD9 and CD63. Exosomes extracts were treated with triton X + proteinase K or proteinase K alone. (C) Flow cytometry analysis using exosomes markers TSG101, CD9, flotillin-1 and CD63 antibodies of MDA-MB231-derived exosomes coupled to 0.4 μm beads. Negative control corresponds to secondary conjugated antibody. (D) Sizing exosomes with Light Scattering Spectroscopy (LSS). Schematic representation of experimental system used to collect LSS spectra (left image). Calibration of the system was done using signals from phosphate buffered saline (PBS) suspensions of glass microspheres with nominal diameters of 24 nm and 100 nm and polystyrene microspheres with nominal diameters of 119 nm, 175 nm, 356 nm and 457 nm. The experimental spectra and resulting fits are shown in the top graph for glass microspheres with nominal diameter of 100 nm and polystyrene microspheres with nominal diameter of 356 nm. Bottom graph represents the size measurement of a PBS suspension of MDA-MB-231 cancer exosomes. Inset shows same graph with a scale up to 10 μm to exclude potential contamination of our exosomes preparations with cells and cellular debris. (E) Exosomes size distribution-using NanoSight. The graph represents the size distribution of particles in solution showing an average of the mode size for all exosomes represented (MDA-MB-231, 4T1, MCF-7, MCF10A, NMuMG and 67NR) of 105 nm and also showing no peaks at larger sizes. (F) Cell viability measured by MTT assay during 5 days of culture of MCF10A, NMuMG, MDA-MB231 and 4T1 cells. Experiment was performed every cell passage to assure good culture conditions. (G) Confocal microscopy showing TUNEL assay. Left panels cells are labeled in red using phalloidin and are negative for TUNEL. Right panels shows positive controls of cells for TUNEL treated with etoposide, a known apoptotic drug. Scale bars represent 20μm. (H) Flow cytometry analysis for propidium iodide (PI) and Anexin V of MDA-MB231 and 4T1 cells. MDA-MB231 cells treated with etoposide were used as a positive control for apoptosis. (I) Immunoblot analysis of cytochrome C in exosomes using MDA-MB231 cells as a positive control and TSG101 as a loading control for exosomes.

The FACs, LSS, NanoSight, MTT, TUNEL data presented in this figure are the result of three independent experiments each with three replicates, and are represented as ± SEM. Table S1, related to Figure 1, miRNAs profiling of MCF10A and MCF7 exosomes. Provided as an Excel file. Table S2, related to Figure 1, differentially expressed miRNAs between MCF10A and MDA-MB-231-derived exosomes. Provided as an Excel file. Table S3, related to Figure 1, miRNAs expression profiling of NMuMG and 4T1 exosomes. Provided as an Excel file. Table S4, related to Figure 1, miRNAs expression profiling of MCF7 exosomes culture for 72 hr versus MCF7 exosomes cultured for 24 hr. Provided as an Excel file. Table S5, related to Figure 1, miRNAs expression profiling of MDA-MB-231 exosomes culture for 72 hr versus MDA-MB-231 exosomes cultured for 24 hr. Provided as an Excel file. Table S6, related to Figure 1, miRNAs expression profiling of 4T1 exosomes culture for 72 hr versus 4T1 exosomes cultured for 24 hr. Provided as an Excel file.

Figure S2, Related to Figure 2. Cancer exosomes get depleted of pre-miRNAs

(A) Bioanalyzer graphical representation depicted in fluorescence units (FU) per nucleotides (nt) (graphs) of the RNA content of human mammary MCF10A (non-tumorigenic) and MDA-MB231 (breast cancer) cell lines; and gel images (right image) of the RNA of MDA-MB-231, MCF7, 4T1, MCF10A and NMuMG cell lines (B) Scatterplots derived from miRNA array data comparing exosomes with cells of origin. Pearson correlation coefficient, r, is used as a measure of the strength of the linear relationship between the two samples. (C) Table with miRNAs IDs used for the study and references that demonstrate their role in cancer. (D) Exosomes harvested from 4T1, MCF-7, MDA-MB231, MCF10A and NMuMG cells were resuspended in DMEM media FBS-depleted and maintained in cell-free culture conditions for 24 and 72h. After 24 and 72h exosomes were recovered and 6 miRNAs were quantified by qPCR. Graphs show the fold change of each miRNA in cancer exosomes after cell-free culture for 24 and 72 hr relative to normosomes after 24 and 72 hr of cell-free culture, respectively. (E) Six pre-miRNAs corresponding to the mature miRNAs previously quantified were quantified by qPCR in NMuMG, 4T1 and MCF-7 exosomes. The inverse of the ΔCt value for each pre-miRNA was plotted. (F) XPO5 mRNA expression in MDA-MB231 cells with two transiently transfected siRNAs targeting XPO5 compared as a fold change to control cells. (G) MDA-MB231 cells were transfected with XPO5 siRNA constructs and miR-21 and miR155 expression was assessed at several time points 12 hr post-transfection (0, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 72 and 96 hr). As a comparison to show the effect of long centrifugation time periods MDA-MB231 cells transfected with XPO5 siRNA constructs were centrifuged at 4°C for 3 hr and put back in culture. MiR-21 and miR155 expression was assessed at several time points post-centrifugation (0, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 72 and 96 hr). Processing of pre-miR21 to miR-21 or pre-miR155 to miR-155 is delayed in centrifuged cells as a two fold in the respective miRNAs is delayed by at least 16 hr.

The qPCR data presented in this figure are the result of three independent experiments each with three replicates, and are represented as ± SEM.; significance was determined using T test (*p<0.05).

Figure S3, Related to Figure 3. Cancer exosomes contain RLC proteins

(A) Immunoblot of Dicer in 4T1, MDA-MB231 and MCF-7 exosomes. MCF10A cell lysate was used as a positive control and MCF10A exosomes as a negative control. (B) Transmission electron micrograph image produced by immunogold labeling using anti-Dicer antibody and negative control in MCF10A cells-derived exosomes. Negative control is secondary antibody. (C) Transmission electron micrograph image produced by immunogold labeling using anti-GFP antibody MDA-MB231-derived exosomes. (D) Immunoblot using anti-flag antibody (upper panel) in MCF10A and MDA-MB231 cells transfected with empty vector (pCMV-Tag4B; first and third lanes respectively) and Flag-Dicer vector (second and fourth lanes). Beta actin immunoblot was used as a loading control (lower panel). (E) Confocal microscopy images of exosomes harvested from normosomes (MCF10A upper panels) and cancer exosomes (MDA-MB231 lower panels) from cells transfected with Flag-Dicer. Immunodetection of Flag (first column; green staining) and CD9 (second column; red) proteins were performed and merged images show co-localization of Flag-Dicer and CD9 cancer exosomes (right lower panel; inset indicates zoomed image). (F) Immunoblot using anti-Dicer antibody (upper panel) in MCF10A, MCF10AshScramble and MCF10AshDicer clones 1 and 2, respectively (MCF10AshDicer clone1 and MCF10AshDicer clone2) cells. Beta actin immunoblot was used as a loading control (lower panel). (G) Immunoblot using anti-Dicer antibody (upper panel) in MDA-MB231, MDA-MB231shScramble and MDA-MB231shDicer clones 1 and 2 cells. Beta actin immunoblot was used as a loading control (lower panel). (H) Confocal microscopy images after immunocytochemistry for Dicer; early endosomes/MVBs components, Hrs and BiG2; late endosomes components, TSG101; in MCF10A, MDA-MB-231 and 4T1 cells and MVBs marker, NRhPE in MCF10A and MDA-MB231 cells. Side graph of images represents the percentage of orange pixels in the image as quantified using image J software. Transmitted light was used to show the cells. (I) Hrs, TSG101 and BiG2 mRNA expression transfected with two different siRNAs for Hrs and TSG101 and two different sh clones for BiG2. (J) NanoSight particle tracking analysis of MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-231siScramble, MDA-MB-231shSramble, MDA-MB-231siTSG101, -siHrs and shBiG2-derived exosomes showing down regulation of exosomes number in Hrs, TSG101 and BiG2 down regulated cells and the exosomes expected size distribution. (K) Confocal microscopy images after immunocytochemistry for Dicer in MCF10A and MDA-MB231 cells: transfected with siHrs (third column), shBiG2 (fourth column), and siTSG101 (last column). Controls of cells transfected with Scramble siRNA are shown in the second panels. Last row shows Dicer in green and multivesicular markers in red. Insets are zoomed images to show co-localization.

The qPCR data and the data presented in panels B, E, H, I and J of this figure are the result of three independent experiments, each with three replicates and are represented as ± SEM; significance was determined using T test (*p<0.05).

Figure S4, Related to Figure 4. Cancer exosomes process pre-miRNAs to generate mature miRNAs

(A) Immunoblot using anti-Dicer antibody in 4T1, 4T1shScramble and 4T1shDicer cells and exosomes harvested from 4T1 (4T1 exos) and 4T1shDicer (4T1shDicer exos) cells (upper blot). GADPH immunoblot was used as loading control (lower blot). Quantification was done using Image J software. (B) Nanosight analysis of exosomes derived from MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-231shScramble, MDA-MB-231shDicer, 4T1, 4T1shScramble, 4T1shDicer, MCF10A, MCF10AshScramble and MCF10AshDicer cells show no significant differences in size distribution or concentration of exosomes derived from parental cells or Dicer depleted cells. (C) Exosomes were harvested from MCF10A cells, MCF10A shScramble cells, MCF10A shDicer cells, MDA-MB-231 cells, MDA-MB-231 shScramble cells, MDA-MB-231shDicer cells, 4T1, 4T1shScramble and 4T1shDicer cells and maintained under cell-free culture conditions for 24 and 72 hr. After 24 and 72 hr, exosomes were extracted again and 6 pre-miRNAs (see Figure S2C) were quantified by qPCR. Graphs show the fold change of each pre-miRNA in the different exosomes after 72 hr of cell-free culture relative to 24 hr cell-free culture. (D) Exosomes were harvested from MCF10A cells, MCF10A shScramble cells, MCF10A shDicer cells, MDA-MB-231 cells, MDA-MB-231 shScramble cells, MDA-MB-231shDicer cells, 4T1, 4T1shScramble and 4T1shDicer cells and maintained under cell-free culture conditions for 24 and 72 hr. After 24 and 72 hr, exosomes were extracted again and 6 miRNAs (see Figure S2C) were quantified by qPCR. Graphs show the fold change of each miRNA in the different exosomes after 72 hr of cell-free culture relative to 24 hr cell-free culture. (E) Graphical representation of the categories (Oncogenic, Tumor Suppressor and Non-determined related to Cancer) of the down regulated miRNAs in MDA-MB231 exosomes electroporated with Dicer (MDA-MB231 exos Dicer AB) compared to MDA-MB231 exosomes (MDA-MB231 exos). MicroRNAs were attributed to each category based on literature. The qPCR and NanoSight presented data in this figure are the result of three independent experiments each with three replicates and are represented as ± SEM. Table S7, related to Figure 4, differentially expressed miRNAs between MDA-MB-231 exosomes and MDA-MB-231 exosomes with Dicer antibody. Provided as an Excel file.

Figure S5, Related to Figure 5. Cancer exosomes process pre-miRNAs to generate mature miRNAs

(A) Exosomes were harvested from MCF10A, MCF10AshDicer, MDA-MB231, MDA-MB231shDicer, MCF7 and MCF-7shDicer cells and electroporated with synthetic pre-miRNA-10b, -21 and –cel-1. Each pre-miRNA was quantified by qPCR in the electroporated exosomes and represented as a fold change relative to exosomes that were electroporated with electroporation buffer only. (B) Dot blot of biotin internally labeled pre-miR-21, -10b and –cel-1 (left blot). Confocal microscopy images of biotin in MCF10A cells transfected with biotin internally labeled pre-miR-21 (first row), -10b (second row) and –cel-1 (third row). Scale bars correspond to 10, 20 and 20 μm, respectively. (C) miR-10b, -21 and –cel-1 expression analysis of MCF10A cells transfected with pre-miR-10b, -21 and –cel-1. Each bar represents the fold change of the transfected cells compared to non-transfected.

UT- Non-transfected; T – Transfected. The presented data in this figure are the result of three independent experiments each with three replicates and are represented as ± SEM.

Figure S6, Related to Figure 6. Cancer exosomes induce transcriptome alterations in recipient cells and tumor formation in a Dicer-dependent manner

(A) NanoSight particle tracking analysis of exosomes derived from MDA-MB231 CD63-GFP cells. Black line represents a measure of total exosomes population and green line depicts the population of exosomes that is labeled with CD63-GFP using the NanoSight equipped with a 488 nm laser beam. (B) Confocal microscopy images of MCF10A cells treated with MDA-MB231 non-labeled exosomes (upper panels) and 100 μg/mL MDA-MB231 CD63GFP exosomes (lower panels). Scale bars are 50 μm. (C) Immunoblot using anti-PTEN antibody and protein extracts of MCF10A cells treated for 0, 30 min, 1, 12 and 24 hr with MDA-MB231 oncosomes freshly extracted. Beta actin was used as a loading control. (D) Immunoblot using anti-HOXD10 antibody and protein extracts of MCF10A cells treated for 0, 30 min, 1, 12 and 24 hr with MDA-MB231 oncosomes freshly extracted. Beta actin was used as a loading control. (E) MCF10A cells were transfected with siRNA for XPO5 to down regulate the flow of pre-miRNAs into the cytoplasm from the nucleus. The processing of pre-miR15 was assessed measuring the levels of miR-15 over time (6h, 12h, 24h, 36h and 48h) in MCF10AsiXPO5 cells and MCF10AsiXPO5 cells treated with MDA-MB231 exosomes with and without Dicer antibody. No significant changes were denoted. (F) Immunoblot using anti-Smad4 antibody (upper panel) and protein extracts of MCF10A cells and MCF10A cells treated with MDA-MB231 exosomes with anti-miR-182-5p and MDA-MB231 exosomes with no cell-free culture time. Beta actin was used as a loading control. (G) miR182-5p expression was monitored in MDA-MB231 derived exosomes over time (0, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 72 and 96 hr). Each bar represents the fold change of each time point compared to 0h. No significant differences were noted. (H) Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining of tumors arising from MCF10A cells co-injected into nude mice with MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-231-Dicer AB-derived exosomes (scale bars represent 100μm). Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

Figure S7, Related to Figure 7. Serum from breast cancer patients contain Dicer and process pre-miRNAs

(A) Representative photos from orthotopic xenografts derived from fragments of fresh primary human ovary, endometrial and breast tumors in nude mice. (B) Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining of ovary, endometrial and breast cancer orthotopic xenografts. (C) Transmission electron micrograph of serum exosomes harvested from mice with orthotopic tumor xenografts. (D) Comassie staining of membranes of immunoblots depicted in Figure 7A. Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining of tumors arising from MCF10A cells co-injected into nude mice with exosomes derived from breast cancer patients.

SIGNIFICANCE.

Breast cancer cells secrete exosomes with specific capacity for cell-independent miRNA biogenesis while normal cells lack this ability. Exosomes derived from cancer cells and serum from patients with breast cancer contain the RISC loading complex proteins, Dicer, TRBP, and AGO2, which process pre-miRNAs into mature miRNAs. Cancer exosomes alter the transcriptome of target cells in a Dicer-dependent manner, which stimulate non-tumorigenic epithelial cells to form tumors. This study identifies a mechanism whereby cancer cells impart an oncogenic field effect by manipulating the surrounding cells via exosomes. Presence of Dicer in exosomes may serve as biomarker for detection of cancer.

Acknowledgments

This work was primarily supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (R. K.). Sonia A. Melo is a Human Frontiers Science Program (HFSP) fellow. L.Q., E.V. and L.T.P. were supported by NSF grants EFRI-1240410, CBET-0922876 and CBET-1144025 and NIH grants R01 EB003472 and R01 EB006462. G. A. C is the Alan M. Gewirtz Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Scholar. He is also supported as a Fellow at The University of Texas MD Anderson Research Trust, as a University of Texas System Regents Research Scholar and by the CLL Global Research Foundation. Work in Dr. Calin’s laboratory is supported in part by the NIH/NCI grants 1UH2TR00943-01 and 1R01 CA182905-01. R. K. is also supported by NIH Grants CA-163191, CA-155370, CA-151925, DK 081576, and DK 055001. We thank Dr. Carolyn Hall for providing us access to the human serum samples.

Footnotes

Accession number

The microarray data are deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus under the accession number GSE60716.

Detailed descriptions of all the methods used in the manuscript are listed in the Supplemental Information file.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS S.A.M. designed and carried out most of the experiments and wrote the manuscript; H.S. performed in vivo mice xenograft experiments of Figure 7; J.T.O. carried out the in vivo mice xenograft experiments of Figure 6; N.K selected positive clones for shBiG2 silencing and did qPCR analysis of BiG2 and Dicer; A.V and A.V carried out human orthotopic implantations in nude mice and collected the tumors; L.Q, E.V and L.T.P carried out LSS experiment; C.A.M carried out mRNA arrays bioinformatic analysis; A.L. provide breast cancer serum samples and helped with patient analysis; C.I performed miRNA array analysis of the data; G. A. C helped with miRNA array analysis and revised the manuscript; R.K conceptually designed and supervised the project and wrote the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Al-Nedawi K, Meehan B, Micallef J, Lhotak V, May L, Guha A, Rak J. Intercellular transfer of the oncogenic receptor EGFRvIII by microvesicles derived from tumour cells. Nature cell biology. 2008;10:619–624. doi: 10.1038/ncb1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chendrimada TP, Gregory RI, Kumaraswamy E, Norman J, Cooch N, Nishikura K, Shiekhattar R. TRBP recruits the Dicer complex to Ago2 for microRNA processing and gene silencing. Nature. 2005;436:740–744. doi: 10.1038/nature03868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocucci E, Racchetti G, Meldolesi J. Shedding microvesicles: artefacts no more. Trends in cell biology. 2009;19:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escola JM, Kleijmeer MJ, Stoorvogel W, Griffith JM, Yoshie O, Geuze HJ. Selective enrichment of tetraspan proteins on the internal vesicles of multivesicular endosomes and on exosomes secreted by human B-lymphocytes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:20121–20127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang H, Qiu L, Vitkin E, Zaman MM, Andersson C, Salahuddin S, Kimerer LM, Cipolloni PB, Modell MD, Turner BS, et al. Confocal light absorption and scattering spectroscopic microscopy. Applied optics. 2007;46:1760–1769. doi: 10.1364/ao.46.001760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipowicz W. RNAi: the nuts and bolts of the RISC machine. Cell. 2005;122:17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory RI, Chendrimada TP, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. Human RISC couples microRNA biogenesis and posttranscriptional gene silencing. Cell. 2005;123:631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grelier G, Voirin N, Ay AS, Cox DG, Chabaud S, Treilleux I, Leon-Goddard S, Rimokh R, Mikaelian I, Venoux C, et al. Prognostic value of Dicer expression in human breast cancers and association with the mesenchymal phenotype. British journal of cancer. 2009;101:673–683. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase AD, Jaskiewicz L, Zhang H, Laine S, Sack R, Gatignol A, Filipowicz W. TRBP, a regulator of cellular PKR and HIV-1 virus expression, interacts with Dicer and functions in RNA silencing. EMBO reports. 2005;6:961–967. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata H, Ueno K, Shahryari V, Tanaka Y, Tabatabai ZL, Hinoda Y, Dahiya R. Oncogenic miRNA-182-5p targets Smad4 and RECK in human bladder cancer. PloS one. 2012;7:e51056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail N, Wang Y, Dakhlallah D, Moldovan L, Agarwal K, Batte K, Shah P, Wisler J, Eubank TD, Tridandapani S, et al. Macrophage microvesicles induce macrophage differentiation and miR-223 transfer. Blood. 2013;121:984–995. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-374793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzkan I, Qiu L, Fang H, Zaman MM, Vitkin E, Ghiran IC, Salahuddin S, Modell M, Andersson C, Kimerer LM, et al. Confocal light absorption and scattering spectroscopic microscopy monitors organelles in live cells with no exogenous labels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:17255–17260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708669104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlert C, Kalluri R. Exosomes in tumor microenvironment influence cancer progression and metastasis. J Mol Med (Berl) 2013;91:431–437. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1020-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogure T, Lin WL, Yan IK, Braconi C, Patel T. Intercellular nanovesicle-mediated microRNA transfer: a mechanism of environmental modulation of hepatocellular cancer cell growth. Hepatology. 2011;54:1237–1248. doi: 10.1002/hep.24504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaka N, Iguchi H, Hagiwara K, Yoshioka Y, Takeshita F, Ochiya T. Neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2)-dependent exosomal transfer of angiogenic microRNAs regulate cancer cell metastasis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:10849–10859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.446831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Zhu D, Huang L, Zhang J, Bian Z, Chen X, Liu Y, Zhang CY, Zen K. Argonaute 2 complexes selectively protect the circulating microRNAs in cell-secreted microvesicles. PloS one. 2012;7:e46957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logozzi M, De Milito A, Lugini L, Borghi M, Calabro L, Spada M, Perdicchio M, Marino ML, Federici C, Iessi E, et al. High levels of exosomes expressing CD63 and caveolin-1 in plasma of melanoma patients. PloS one. 2009;4:e5219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Lamb J, Peck D, Sweet-Cordero A, Ebert BL, Mak RH, Ferrando AA, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005;435:834–838. doi: 10.1038/nature03702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luga V, Zhang L, Viloria-Petit AM, Ogunjimi AA, Inanlou MR, Chiu E, Buchanan M, Hosein AN, Basik M, Wrana JL. Exosomes Mediate Stromal Mobilization of Autocrine Wnt-PCP Signaling in Breast Cancer Cell Migration. Cell. 2012;151:1542–1556. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Teruya-Feldstein J, Weinberg RA. Tumour invasion and metastasis initiated by microRNA-10b in breast cancer. Nature. 2007;449:682–688. doi: 10.1038/nature06174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacRae IJ, Ma E, Zhou M, Robinson CV, Doudna JA. In vitro reconstitution of the human RISC-loading complex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:512–517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710869105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniataki E, Mourelatos Z. A human, ATP-independent, RISC assembly machine fueled by pre-miRNA. Genes & development. 2005;19:2979–2990. doi: 10.1101/gad.1384005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martello G, Rosato A, Ferrari F, Manfrin A, Cordenonsi M, Dupont S, Enzo E, Guzzardo V, Rondina M, Spruce T, et al. A MicroRNA targeting dicer for metastasis control. Cell. 2010;141:1195–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavel S, Thery I, Gueiffier A. Synthesis of imidazo[2,1-a]phthalazines, potential inhibitors of p38 MAP kinase. Prediction of binding affinities of protein ligands. Arch Pharm (Weinheim) 2002;335:7–14. doi: 10.1002/1521-4184(200201)335:1<7::aid-ardp7>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo S, Villanueva A, Moutinho C, Davalos V, Spizzo R, Ivan C, Rossi S, Setien F, Casanovas O, Simo-Riudalbas L, et al. Small molecule enoxacin is a cancer-specific growth inhibitor that acts by enhancing TAR RNA-binding protein 2-mediated microRNA processing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:4394–4399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014720108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo SA, Moutinho C, Ropero S, Calin GA, Rossi S, Spizzo R, Fernandez AF, Davalos V, Villanueva A, Montoya G, et al. A genetic defect in exportin-5 traps precursor microRNAs in the nucleus of cancer cells. Cancer cell. 2010;18:303–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo SA, Ropero S, Moutinho C, Aaltonen LA, Yamamoto H, Calin GA, Rossi S, Fernandez AF, Carneiro F, Oliveira C, et al. A TARBP2 mutation in human cancer impairs microRNA processing and DICER1 function. Nature genetics. 2009;41:365–370. doi: 10.1038/ng.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Mirantes C, Eritja N, Dosil MA, Santacana M, Pallares J, Gatius S, Bergada L, Maiques O, Matias-Guiu X, Dolcet X. An inducible knockout mouse to model the cell-autonomous role of PTEN in initiating endometrial, prostate and thyroid neoplasias. Disease models & mechanisms. 2013;6:710–720. doi: 10.1242/dmm.011445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montecalvo A, Larregina AT, Shufesky WJ, Stolz DB, Sullivan ML, Karlsson JM, Baty CJ, Gibson GA, Erdos G, Wang Z, et al. Mechanism of transfer of functional microRNAs between mouse dendritic cells via exosomes. Blood. 2012;119:756–766. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-338004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan A, Iordanskiy S, Das R, Van Duyne R, Santos S, Jaworski E, Guendel I, Sampey G, Dalby E, Iglesias-Ussel M, et al. Exosomes derived from HIV-1-infected cells contain trans-activation response element RNA. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:20014–20033. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.438895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]