Abstract

Fanconi anemia (FA) is a rare autosomal recessive cancer-prone inherited bone marrow failure syndrome, due to mutations in 16 genes, whose protein products collaborate in a DNA repair pathway. The major complications are aplastic anemia, acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), and specific solid tumors. A severe subset, due to mutations in FANCD1/BRCA2, has a cumulative incidence of cancer of 97% by age 7 years; the cancers are AML, brain tumors, and Wilms tumor; several patients have multiple events. Patients with the other genotypes (FANCA through FANCQ) have cumulative risks of more than 50% of marrow failure, 20% of AML, and 30% of solid tumors (usually head and neck or gynecologic squamous cell carcinoma), by age 40, and they too are at risk of multiple adverse events. Hematopoietic stem cell transplant may cure AML and MDS, and preemptive transplant may be appropriate, but its use is a complicated decision.

Keywords: Fanconi anemia, leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, bone marrow failure, stem cell transplant

Introduction

Fanconi anemia (FA, MIM 607139) is one of the rare inherited bone marrow failure syndromes (IBMFS) with a very high cancer-predisposition, including leukemia. It is primarily autosomal recessive (except FANCB which is X-linked), due to mutations in more than 16 genes, whose gene products collaborate in a DNA repair pathway. The majority of known patients have a variety of physical anomalies, including short stature, café au lait spots and hyper/hypopigmentation, abnormal thumbs, absent radii, microcephaly, micro-ophthalmia, structural renal anomalies, and other findings. It was first described in 1927 by Dr Guido Fanconi, and more than 2000 cases have been reported in the literature. Many patients are recognized because of the development of aplastic anemia, which has a peak at around 7 years of age [1]. The age at diagnosis ranges from in utero to over 50 years, and includes adults with no physical findings who present with aplastic anemia, leukemia, or solid tumors; the number of undiagnosed adults who are spared these complications and lack birth defects is unknown. FA is one of several IBMFS, which share hematologic changes leading to the diagnosis, such as pancytopenia or single lineage cytopenias, very high risks of leukemia, primarily acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and extremely high risks of specific solid tumors. The molecular pathways are very different, however (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inherited bone marrow failure syndromes.

| Syndrome | Hematologya | Leukemia | Solid Tumors | Pathway |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fanconi anemia | Aplastic anemia | AMLb | SCCc | DNA repair |

| Dyskeratosis congenita | Aplastic anemia | AML | SCC | Telomere biology |

| Diamond-Blackfan anemia | Anemia | AML | Osteosarcomas | Ribosome biogenesis |

| Shwachman-Diamond syndrome | Neutropenia | AML | - | Ribosome biogenesis |

| Severe congenital neutropenia | Neutropenia | AML | - | Neutrophil differentiation |

| Amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia | Thrombocytopenia | AML | - | Mutations in thrombopoietin receptor |

| Thrombocytopenia absent radii | Thrombocytopenia | AML | - | exon-junction complex subunit Y14 at 1q21.1 |

At diagnosis.

Acute myeloid leukemia.

Squamous cell carcinomas, particularly head and neck and gynecologic. Adapted from [1].

Reprinted from Blood Reviews, Volume 24/Edition 3, Shimamura A, Alter BP, Pathophysiology and management of inherited bone marrow failure syndromes, Pages 101-22, 2010, with permission from Elsevier.

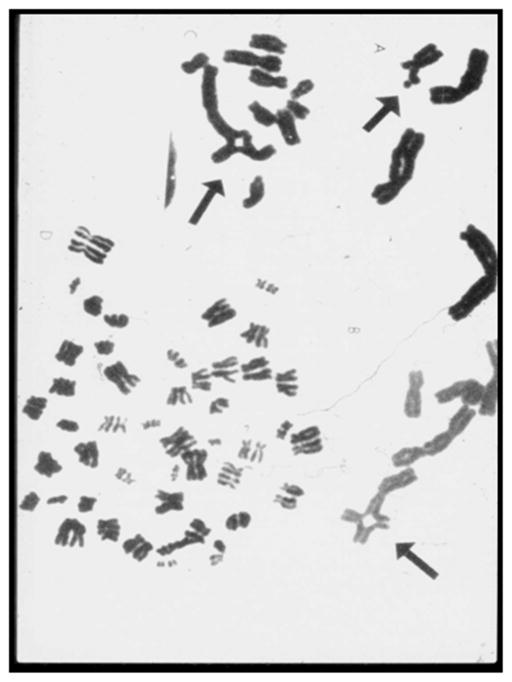

The usual diagnostic test for FA involves detection of an increased amount of chromosomal breakage in peripheral blood T lymphocytes cultured with a clastogenic agent such as diepoxybutyrate or mitomycin C (Fig. 1). This widely used labor intensive assay is very sensitive and specific. The only limitation is the identification of patients with hematopoietic somatic mosaicism, in whom a hematopoietic stem cell may have undergone a genetic correction by several mechanisms (eg, gene conversion), leading to marrow and blood cells that have a selective growth advantage. Testing of skin fibroblasts may be required if there is insufficient chromosomal breakage to clearly diagnose FA but it is suspected clinically [2].

Figure 1.

Chromosome breakage. Metaphases from blood T-lymphocytes following culture with phytohemagglutinin and a DNA crosslinking agent such as diepoxybutante or mitmycin C. Figure shows breaks, gaps, rearrangements and endoreduplications.

Genetics

There are 16 known FA genes, of which FANCA is the most frequent, followed by FANCC and FANCG; FANCB is a rare X-linked recessive gene, while all the others are autosomal recessive (Fig. 2). The FA/BRCA2 DNA repair pathway begins when DNA damage occurs. The genes for FANCA, FANCB, FANCC, FANCE, FANCF, FANCG, FANCL, and FANCM are activated, produce RNA, which then leads to proteins that combine into the core complex (Fig. 3). This complex is necessary for the ubiquitination of the FANCD2 and FANCI proteins, which form the ID complex, which then permits DNA repair foci to form, including the downstream gene products, J/BRIP1, D1/BRCA2, N/PALB2, O/RAD51C, P/SLX4, and Q/ERCC4 [3]. Biallelic mutations in any of these genes prevent the repair pathway from operating. Patients with biallelic mutations in FANCD1/BRCA2 have a unique phenotype and cancer risk (see below).

Figure 2.

Fanconi anemia genes, indicating the majority are FANCA, followed by FANCC and FANCG, and others less frequent. The ones marked with an asterisk are associated with breast cancer in heterozygotes, and FA when mutations occur in both alleles. Adapted from Leiden Open Variation Database, http://chromium.liacs.nl/LOVD2/FANC/home.php.

Figure 3.

FA/BRCA DNA damage response pathway. Following DNA damage, the proteins represented by A, B, C, E, F, G, L and M form the core complex, which is required for ubiquitination of the I and D2 proteins, which are in turn required for the downstream complex of D2-ubi, I-ubi, and D1/BRCA2, J/BRIP1, N/PALB2, BRCA1, O/RAD51C, P/SLX4, Q/ERCC4, and BRCA1 to form DNA repair foci. Only BRCA1 has not yet been proven to be a Fanconi gene. Adapted from Shimamura and Alter [1].

Reprinted from Blood Reviews, Volume 24/Edition 3, Shimamura A, Alter BP, Pathophysiology and management of inherited bone marrow failure syndromes, Pages 101-22, 2010, with permission from Elsevier.

Leukemia and solid Tumors

More than 400 among over 2000 cases with FA were reported to have some type of malignancy (Fig. 4). There were 188 leukemias and 286 solid tumors described in 413 patients by the end of 2012; 47 had 2–4 cancers. Eighty-four percent of the leukemias were AML, which is more typical of adults than children, where acute lymphoblastic leukemia is much more common. The most frequent solid tumors were head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), among untransplanted patients as well as those who had received a hematopoietic stem cell transplant. The next most frequent tumors were liver, brain, vulvar SCC, and Wilms tumor. Many of the brain and Wilms tumors were in patients whose genotypes were unknown at the time, but might have been FANCD1/BRCA2 (see below).

Figure 4.

The types and frequencies of cancer in FA reported in the literature from 1927 through 2012. There were 188 cases of leukemia, of which 84% were acute myeloid leukemia, and 286 solid tumors, in 413 of 2190 people with FA. Forty-seven had 2–4 cancers.

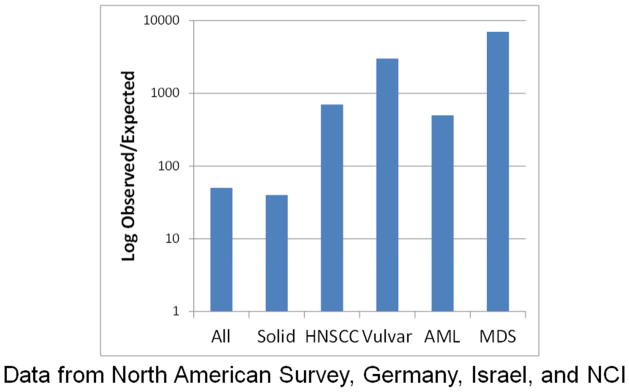

The relative risk of cancer in FA is exceedingly high, when compared with the incidences expected in the general population. We combined data from four independent FA cohorts for our analyses [4–7], and found that the observed to expected ratio of all cancers including leukemia was 48 after adjustment for age, sex, and birth cohort. Solid tumors had a relative risk of 38-, HNSCC 600-, AML 700-, vulvar SCC 3000-, and MDS 6000-fold (Fig. 5). These enormously high numbers are due to the cancers in FA occurring at much younger ages than in the general population. The peak hazard rate for severe bone marrow failure (BMF) was 5% per year at age 6.7 years, after which the annual hazard declined substantially, while the hazard for AML rose after age 10 and then plateaued in the 20- and 30-year-old patients, and the hazard for solid tumors increased after age 10 in a more than linear manner, exceeding 10% per year by age 40 (Fig. 6) [4]. MDS was analyzed separately, since it does not compete with solid tumors, and may follow BMF or precede AML; the hazard rate reached around 1% per year starting at age 10 and then plateaued, and the cumulative incidence was 40% by age 50 (data not shown). The cumulative incidence of each of the adverse events as the first event in a competing risk analysis was 60% for BMF, 15% for AML, and >20% for solid tumors, with no plateau for the latter (Fig. 6). Thus, FA in general is an extremely cancer-prone syndrome. Leukemia has been managed with chemotherapy followed by hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, with improving results over time [8]. However, solid tumors are more complicated and the prognosis less optimistic, since the major management strategy is surgery, and recurrences are frequent.

Figure 5.

The relative risk of cancer compared with the general population (using SEER data) in a combination of four independent cohorts. The Y axis shows the observed/expected ratio on a log scale. The risk of any cancer was ~50-fold, solid tumors ~40-fold, HNSCC ~550-fold, vulvar 3000-fold, AML 700-fold, and MDS 6600-fold. Data from [4–7].

Figure 6.

Annual hazard rate and cumulative incidence of competing adverse events by age in patients with Fanconi Anaemia (FA). Adverse events are severe bone marrow failure (BMF, blue), leukemia (AML, black), or solid tumors (ST, red). Results are combined from the cohorts cited in Figure 5. Left, Annual hazard rate in percent per year. Right, cumulative incidence by age (cumulative percentage experiencing each event as initial cause of failure) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) (shaded areas). From Alter et al [4].

Reprinted from Alter BP, Giri N, Savage SA, et al. Malignancies and survival patterns in the National Cancer Institute inherited bone marrow failure syndromes cohort study. Br J Haematol 2010;150:179–188, with permission from John Wiley and Sons.

FANCD1/BRCA2

Patients with biallelic mutations in FANCD1/BRCA2 are a special subset with unique genotype/phenotype/outcome associations [9,10]. Their physical anomalies often include many of the following: short stature, microcephaly, micro-ophthalmia, abnormal thumbs and/or radii, café au lait spots, hyper-and hypopigmented skin, imperforate anus, structural renal anomalies, and congenital heart disease; many of the features of these patients are included in the VATER association acronym [11]. The patients have very high risks of development of malignancies (Fig. 7). Leukemia, primarily AML, was reported in 17 of 36 patients, with a cumulative incidence of about 80% by age 10 years. The 6 children with a unique site for their mutation in BRCA2, namely IVS7, all developed leukemia before age 3, a very strong example of genotype/cancer association, although those with other mutations were also at a high risk of leukemia. Sixteen patients had brain tumors by age 5, including all 7 with one mutated allele 886delGT. Wilms tumor was the next most frequent type of cancer, reported in 8 patients, all by age 5. Overall 22 patients had solid tumors, of whom 9 had at least two malignancies (solid tumor and/or leukemia), and the cumulative incidence of any malignancy was 97% by age 7 years.

Figure 7.

Outcomes in patients with FA due to mutations in FANCD1/BRCA2. (A) Probability of any type of leukemia. (B) Probability of a brain tumor, associated with a mutation in 886delGT compared with other mutations. The relative hazard due to 886delGT is 4 (CI 2 – 12). (C) Probability of any solid tumor. (D) Probability of leukemia associated with a mutation in IVS7 compared with other mutations. The relative hazard due to IVS7 is 4 (CI 1.3 – 13). (E) Probability of Wilms tumor. (F) Probability of any cancer is 97% by age 7 years. Adapted and updated from Alter et al [9,10].

Reproduced from J Med Genet, Alter BP, Rosenberg PS, Brody LC, volume 44, pages 1–9, 2007, with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Comparison of FANCD1/BRCA2 and other FA patients

The major adverse events are similar in all types of FA, but the frequencies and ages differ substantially (Table 2). Almost all of those with FANCD1/BRCA2 have one or more cancers before age 7, either leukemia, brain tumor, Wilms tumor, or combinations, and very few develop severe bone marrow failure. More than half of the other patients with FA develop severe bone marrow failure, as well as solid tumors (30%) and/or leukemia (20%) by age 40–50 years. However, at least 10% and perhaps more whom we have not identified, do not develop these complications.

Table 2.

Comparison of patients with FANCD1/BRCA2 and other mutations.

| Adverse Event | FANCD1/BRCA2 | Other Genes |

|---|---|---|

| By age, years | 7 | 40 |

| Leukemia | 50% | 20% |

| Solid Tumor | 80% | 30% |

| Any Cancer | 97% | 50% |

| Severe bone marrow failure | <5% | 50% |

| No adverse event | <5% | <10% |

Management of bone marrow

The community of FA physicians has agreed on consensus guidelines for treatment of hematologic disease, namely marrow failure with hemoglobin <8 g/dL, platelets <30,000/mm3, absolute neutrophil count < 500/mm3, or overt leukemia with blasts in the blood or >20% in the marrow, or MDS with dyspoieses and cytopenias [12]. However, they have not fully addressed the concept of preemptive transplant, to preclude the development of leukemia or MDS. Patients with FA with the highest risks of AML or MDS may be identified as those with mutations in FANCD1/BRCA2, but may also have mutations in any of the other 15 FA genes, and the transplant decision may depend on different criteria. The definition of MDS in adults according to the World Health Organization usually involves hypercellular marrow, often with specific cytogenetic clones that have variable prognostic significance, dysplasia in one or more lineages, and an increased risk of AML. MDS in pediatrics (not necessarily FA) is most commonly refractory cytopenia of childhood (RCC), with hypocellular marrow, monosomy 7 the most frequent clone, and dyspoiesis in at least 10% of cells in one or more lineages, or “any” dyspoiesis in two or more lineages [13,14]. The FA scientific community has not fully clarified the criteria for transplant before MDS or AML, although those events increase the risk of a poor transplant outcome.

The decision to perform a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (SCT) is not clearcut, and requires shared decision making between physicians and families. The components of the decision include information regarding the risk of not surviving the procedure, the possibility of post-SCT complications, which could include graft-versus-host disease, immune dysfunction, and endocrine disorders, as well as subsequent development of solid tumors. These tumors could be the ones that occur with very high frequency in patients with FANCD1/BRCA2 and are independent of transplant, or HNSCC for which the very high risk in patients with FA is even higher after SCT [9,15]. A recent survey of parents of participants in the Fanconi Anemia Research Fund registry indicated that the decision is not easy, associated with uncertainty due to the indeterminacy of the outcome risks, as well as ambiguity of the risk estimates related to conflicting evidence, conflicting opinions, and lack of information. Families seek expert opinions, but may delegate the ultimate decision to their physicians [16]. It must be emphasized, however, that almost half of the patients with FA may never need a transplant, and a challenge for the physicians is to identify those patients.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the patients who participate in the National Cancer Institute inherited bone marrow failure syndromes (IBMFS) cohort, to the physicians who referred the patients, and to our colleagues in the Clinical Genetics Branch of the NCI and the subspecialty clinics at the National Institutes of Health for their evaluations of the patients. We thank Lisa Leathwood, RN; Ann Carr, MS, CGC; Maureen Risch, RN; and the other members of the IBMFS team at Westat, Inc. for their extensive efforts. This work was supported in part by the Intramural Program of the National Institutes of Health and the National Cancer Institute and by contracts N02-CP-11019, N02-CP-65504, and N02-CP-65501.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Shimamura A, Alter BP. Pathophysiology and management of inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Blood Rev. 2010;24:101–22. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alter BP, Joenje H, Oostra AB, Pals G. Fanconi anemia: adult head and neck cancer and hematopoietic mosaicism. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131:635–9. doi: 10.1001/archotol.131.7.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grompe M, van de Vrugt HJ. The Fanconi family adds a fraternal twin. Dev Cell. 2007;12:661–2. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alter BP, Giri N, Savage SA, Peters JA, Loud JT, Leathwood L, et al. Malignancies and survival patterns in the National Cancer Institute inherited bone marrow failure syndromes cohort study. Br J Haematol. 2010;150:179–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08212.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenberg PS, Greene MH, Alter BP. Cancer incidence in persons with Fanconi anemia. Blood. 2003;101:822–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenberg PS, Alter BP, Ebell W. Cancer Risks in Fanconi Anemia: Experience of the German Fanconi Anemia (GEFA) Registry. Haematologica. 2007;93:511–7. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tamary H, Nishri D, Yacobovich J, Zilber R, Dgany O, Krasnov T, et al. Frequency and natural history of inherited bone marrow failure syndromes: the Israeli Inherited Bone Marrow Failure Registry. Haematologica. 2010;95:1300–7. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.018119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell R, Wagner JE, Hirsch B, DeFor TE, Zierhut H, MacMillan ML. Haematopoietic cell transplantation for acute leukaemia and advanced myelodysplastic syndrome in Fanconi anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2014;164:384–95. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alter BP, Rosenberg PS, Brody LC. Clinical and molecular features associated with biallelic mutations in FANCD1/BRCA2. J Med Genet. 2007;44:1–9. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.043257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alter BP. The association between FANCD1/BRCA2 mutations and leukemia. Br J Haematol. 2006;133:446–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alter BP, Rosenberg PS. VACTERL-H Association and Fanconi Anemia. Mol Syndromol. 2013;4:87–93. doi: 10.1159/000346035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management, 2008. 3. Eugene, OR: Fanconi Anemia Research Fund, Inc; 2008. Fanconi Anemia. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, Brunning RD, Borowitz MJ, Porwit A, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009;114(5):937–51. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baumann I, Niemeyer CM, Bennett JM, Shann . Childhood myelodysplastic syndrome. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, et al., editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: IARC; 2008. pp. 104–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenberg PS, Socie G, Alter BP, Gluckman E. Risk of head and neck squamous cell cancer and death in patients with Fanconi Anemia who did and did not receive transplants. Blood. 2005;105:67–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton JG, Hutson SP, Moser RP, Kobrin SC, Frohnmayer AE, Alter BP, et al. Sources of uncertainty and their association with medical decision making: exploring mechanisms in Fanconi anemia. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(2):204–16. doi: 10.1007/s12160-013-9507-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]