Abstract

Objective

To report long-term mortality following oophorectomy or ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy in subgroups of women based on age at the time of surgery, use of estrogen therapy, presence of risk-factors for CHD and length of follow-up.

Methods

A prospective cohort study of 30,117 Nurses’ Health Study participants having a hysterectomy for benign disease Multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios [HR] for death from CHD, stroke, breast cancer, epithelial ovarian cancer, lung cancer, colorectal cancer, total cancer and all-causes were determined, comparing bilateral oophorectomy (n=16,914) with ovarian conservation (n=13,203).

Results

Over 28 years of follow-up, 16.8% of women with hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy died from all causes compared with 13.3% of women who had ovarian conservation (HR=1.13;95% confidence interval [CI] 1.06–1.21). Oophorectomy was associated with a lower risk of death from ovarian cancer (4v44) and prior to age 47.5 years a lower risk of death from breast cancer. However at no age was oophorectomy associated with a lower risk of other cause-specific or all-cause mortality. For women younger than 50 at the time of hysterectomy, bilateral oophorectomy was associated with significantly increased mortality in women who had never-used estrogen therapy, but not in past and current users: all-cause mortality (HR=1.41;95% CI, 1.04–1.92;Pinteraction=0.03); lung cancer mortality (HR=1.44;95% CI, 0.17–1.21;Pinteraction=0.02); and CHD mortality (HR=2.35;95% CI, 1.22–4.27;Pinteraction=0.02).

Conclusions

For women younger than 50 at the time of hysterectomy, bilateral oophorectomy was associated with significantly increased mortality in women who had never-used estrogen therapy. At no age was oophorectomy associated with increased overall survival.

INTRODUCTION

Each year approximately 610,000 US women have a hysterectomy for benign disease and 23% of women aged 40 to 44 years and 45% of women aged 45 to 49 years have concomitant elective oophorectomy in order to prevent the subsequent development of ovarian cancer. (1,2)

Bilateral oophorectomy, when compared with ovarian conservation, is associated with a decreased risk of ovarian cancer, but may increase risks of death from coronary heart disease (CHD) and all causes. (3,4) Although some studies are not consistent with these findings, they include small numbers of women, have short-term or delayed onset of follow-up or compared oophorectomy with natural menopause. (5,6)

The Nurses' Health Study (NHS) is an ongoing prospective observational study of women and health outcomes. In a previous investigation over 24 years of follow-up, we found that bilateral oophorectomy, compared with ovarian conservation, at time of hysterectomy was associated with a lower risk of incident ovarian and breast cancer, but a higher risk of incident CHD, stroke, lung cancer and total cancers, and mortality from all causes. (7)

In this further analysis of updated data from the NHS, we focused on all-cause and cause-specific mortality and addressed clinical issues raised by earlier publications. Specifically, we examined bilateral oophorectomy versus ovarian conservation in women age 60 or more and determined whether there was an age at which oophorectomy confers a survival benefit. We also conducted analyses in several subgroups of women who we hypothesized would experience a more elevated mortality after bilateral oophorectomy, including women who had a hysterectomy prior to age 50 who never used estrogen therapy; women with known risk factors for CVD; women with a family history of breast or ovarian cancer; and women who smoked. Finally, we examined CVD mortality associated with oophorectomy status in women who were observed for 15 years or longer following hysterectomy to ascertain if long-term follow-up is important for this research.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The NHS cohort includes 121,700 female registered nurses in the U.S. who were aged 30–55 years when they completed the initial mailed questionnaires in 1976. Participants provided detailed information about medical history and risk-factors for cancer, heart disease, and other diseases. Information has been updated on biennial follow-up questionnaires with response rates of approximately 90% for each cycle.(8) The cohort was relatively homogeneous with regard to education, socioeconomic status, and access to health-care. Race was self-reported: 94% white, 2% African-American, 1% Asian, 1% multiracial and 2% other.

NHS participants with a prior hysterectomy entered study follow-up in 1980, when information was available for all relevant risk factors. Other participants entered when they reported having a hysterectomy on the 1982 through 2006 questionnaires. Overall, 52,157 NHS participants reported having a hysterectomy without a diagnosis of gynecologic cancer. We excluded 9,380 women with a prior history of other cancers, coronary heart disease, stroke, or pulmonary embolus; 4,909 with unilateral or partial oophorectomy; 4,869 with unknown age at hysterectomy; 2,559 with unknown ovarian status at the time of hysterectomy; and 555 with oophorectomy before or after, rather than at the time of, hysterectomy. The remaining 30,117 women were included in the analysis; 16,914 (56.2%) had a hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy, and 13,203 (43.8%) had a hysterectomy with ovarian conservation. Submission of completed self-administered questionnaires was deemed to imply informed consent. The institutional review boards at John Wayne Cancer Institute at Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, California and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts approved this study.

NHS participants completed mailed, biennial follow-up questionnaires on which they reported age, age at hysterectomy, parental history of myocardial infarction before age 60, tubal ligation, parity, family history of breast cancer, family history of ovarian cancer, diabetes, high blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia, smoking status, duration of oral contraceptive use, use of estrogen therapy (ET), alcohol consumption, physical activity and aspirin use. Body mass index (BMI) from the initial 1976 questionnaire was used for the analysis. A validation study ascertained that self-report of oophorectomy was more than 90% accurate, as compared with medical records.(9) For ET use before 1976, age at initiation, doses, types and routes of administration could not be examined because they were not ascertained on early questionnaires. For all variables, missing information was separately noted.

We identified deaths using the National Death Index and by reports of next of kin which was more than 98% complete. (10) Date and cause of death were determined using death certificates, autopsy reports, and medical records. We assessed deaths due to the following conditions: CHD, stroke, breast cancer, epithelial ovarian cancer, lung cancer, colorectal cancer, total cancer and all-causes.

Women contributed person-time from the return of the 1980 questionnaire or a later questionnaire after incident hysterectomy and were censored at oophorectomy subsequent to hysterectomy, death, or the end of follow-up on June 1, 2008. We used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate hazard ratios [HR] and corresponding 95% confidence intervals [CI] comparing bilateral oophorectomy with ovarian conservation. Analyses were stratified by age and questionnaire cycle and were controlled for relevant risk-factors. We conducted modeling separately for three sub-cohorts based on age at hysterectomy: younger than 50 years, 50–59 years, and 60 years or older. For this and other stratified analyses, we used the significance of the interaction term between the exposure and the stratifying variable to test whether results were statistically different across strata (Pinteraction).

We were interested in potential confounding by diabetes, high blood pressure and hypercholesterolemia prior to hysterectomy. However, 47% of women had a hysterectomy before they entered the cohort in 1976 and we did not include these risk-factors in the primary models. In a sensitivity analysis, we included these factors reported in 1976 for women with hysterectomy prior to 1976 and, for women who had a hysterectomy after 1976 we used the status of these risk-factors just prior to surgery. Results of the sensitivity analysis were very similar to those reported in the primary models (data not shown).

We constructed models with age at hysterectomy as a continuous independent variable to examine if there was an age at which oophorectomy conferred survival benefit. For each outcome, linear and quadratic models were conducted and compared. In the linear model, age at hysterectomy was included with other covariates. In the quadratic model, a linear term and a quadratic term of age at hysterectomy were included. We performed a likelihood ratio test to determine if the quadratic model would be a better fit, and if so, the cutoff point at which age at hysterectomy conferred survival benefit was estimated. The cutoff point is the age that achieves the highest (for concave down shape) or lowest (for concave up shape) value of the quadratic equation.

We conducted several stratified analyses to assess the association between oophorectomy and mortality in targeted subgroups. In women who had a hysterectomy prior to age 50, we assessed all-cause and cause-specific mortality in relation to oophorectomy in women who never used ET and compared these results with those in past and current ET users. We also examined the risk of all-cause and CVD mortality associated with bilateral oophorectomy stratified by the presence of risk-factors for CVD: diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, current smoker, BMI > 30 in 1976, or parental history of MI before age 60. Women were considered high-risk if they had two or more risk-factors and low-risk if they had zero or one risk-factor. This analysis was limited to women who had a hysterectomy after entering the cohort in 1976 (n=16,395) for whom the presence of CVD risk factors could be ascertained at time of hysterectomy. Other stratified analyses were conducted by smoking status and by family history of breast or ovarian cancer.

Autopsy studies suggest that following oophorectomy, cardiovascular disease (CVD) takes approximately 15 years to develop. (11) Therefore, prolonged follow-up would be necessary to detect an association with increased CVD mortality. We conducted a subset analysis of women who had 15 or more years of follow-up subsequent to their hysterectomy. We excluded women who died (n=835) or had CVD outcome (n=519) within 15 years of surgery and women who had less than 15 years of follow-up after hysterectomy (n=5,421). Within this subgroup, we compared women with bilateral oophorectomy (n=13,118) with those who had ovarian conservation (n=10,093). All data transformations and statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2. (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). All P values were based on two-tailed tests with significance of 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics stratified by age at hysterectomy (<50, 50–59, 60 or older) and oophorectomy status are presented in Table 1. Most characteristics were similar across strata. Data were missing for <5% of participants for all variables except duration of ET use, alcohol consumption, and aspirin use.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristicsa of the study population by age at hysterectomy and oophorectomy status

| Age at Hysterectomy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 50 y | 50–59 y | ≥ 60 y | ||||

| Ovarian Conservation (n=10,147) |

Bilateral Oophorectomy (n=10,947) |

Ovarian Conservation (n=1,746) |

Bilateral Oophorectomy (n=4,495) |

Ovarian Conservation (n=1,310) |

Bilateral Oophorectomy (n=1,472) |

|

| Age, y | 47.8 | 49.1 | 56.1 | 55.2 | 68.5 | 67.6 |

| Age at hysterectomy, y | 39.6 | 42.4 | 54.1 | 53.0 | 67.5 | 66.5 |

| Diabetesb, % | 2.1 | 2.6 | 3.6 | 2.8 | 5.0 | 5.7 |

| High blood pressureb, % | 12.9 | 16.9 | 22.5 | 24.7 | 44.3 | 42.8 |

| Hypercholesterolemiab, % | 4.1 | 6.4 | 15.3 | 18.4 | 51.9 | 55.0 |

| Tubal ligation, % | 9.4 | 11.9 | 17.7 | 21.9 | 13.6 | 16.8 |

| Family history: | ||||||

| MI before age 60, % | 17.9 | 17.2 | 15.6 | 16.1 | 13.9 | 15.0 |

| Breast cancer, % | 18.8 | 17.6 | 21.0 | 18.7 | 20.1 | 19.0 |

| Ovarian cancer, % | 4.9 | 5.1 | 5.8 | 5.9 | 4.5 | 6.4 |

| BMI in 1976 (kg/m2): | ||||||

| < 25, % | 70.4 | 69.0 | 70.5 | 70.3 | 69.1 | 75.2 |

| 25–29.9, % | 21.1 | 21.2 | 22.1 | 20.8 | 21.8 | 18.1 |

| ≥ 30, % | 7.6 | 8.8 | 6.7 | 7.7 | 7.9 | 5.9 |

| Smoking status: | ||||||

| Past smoker, % | 27.5 | 28.6 | 33.3 | 37.2 | 45.5 | 43.4 |

| Current smoker, % | 25.9 | 24.8 | 15.6 | 12.8 | 6.6 | 6.3 |

| Estrogen therapy use: | ||||||

| Past or current user, % | 30.2 | 77.0 | 56.7 | 80.5 | 68.5 | 80.6 |

| Duration of use, y | 4.8 | 4.4 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 5.7 | 7.8 |

| Oral contraceptive use: | ||||||

| Past user, % | 51.6 | 46.7 | 42.4 | 50.7 | 38.2 | 46.3 |

| Duration of past use, y | 3.5 | 3.3 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 4.4 |

| Parous, % | 93.8 | 88.2 | 94.4 | 93.2 | 93.8 | 93.3 |

| Parityc | 3.3 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 3.3 |

| Physical activity, h/wk | 3.0 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 2.8 |

| Alcohol: | ||||||

| Drinkers, % | 59.3 | 52.7 | 56.6 | 57.3 | 51.9 | 53.0 |

| Current drinkers, g/d | 9.4 | 8.8 | 9.6 | 9.1 | 8.7 | 10.2 |

| Aspirin use: | ||||||

| Current user, % | 35.5 | 33.5 | 33.6 | 34.5 | 32.4 | 34.6 |

| Duration of use, y | 16.7 | 16.1 | 16.4 | 16.8 | 21.5 | 23.1 |

MI, myocardial infarction; BMI, body mass index

Values are means and percentages within the strata. Unless otherwise noted, data are from the 1980 questionnaire for women with prevalent hysterectomy or from the most recent questionnaire at the time of incident hysterectomy (1982–2006).

Status reported in 1976 for women with prevalent hysterectomy or from the most recent questionnaire at the time of incident hysterectomy (1978–2006)

Number of children among parous women

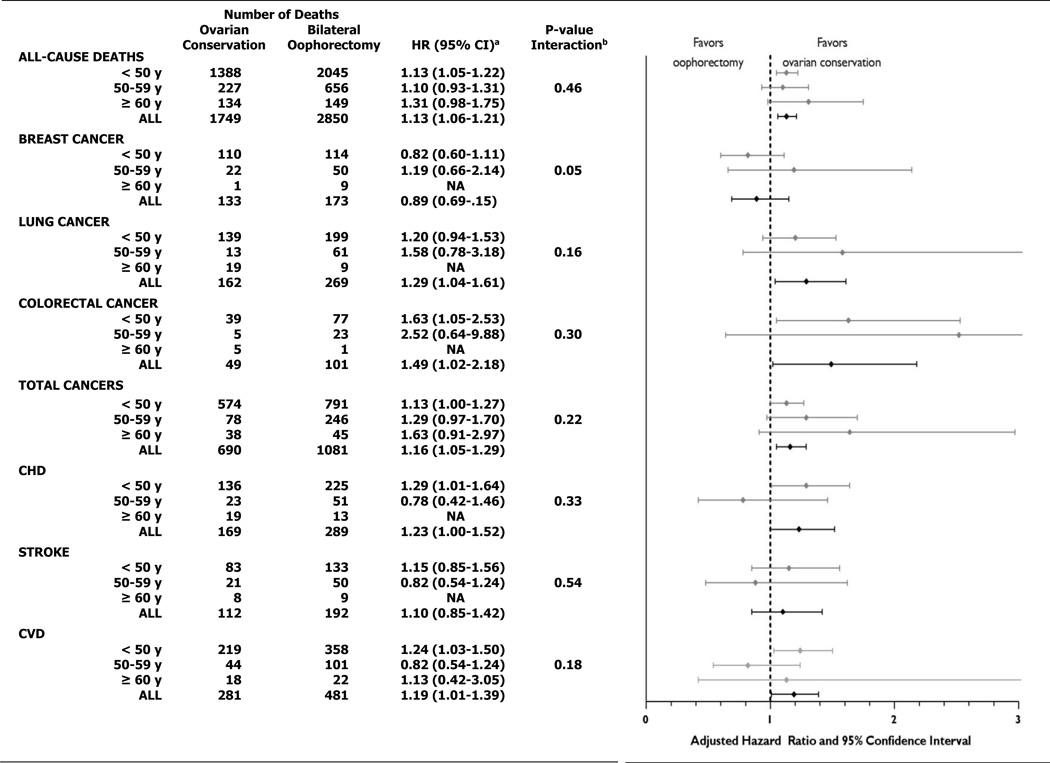

In the analysis of all women with hysterectomy (Figure 1), 2850 (16.8%) women with bilateral oophorectomy died from all causes compared with 1749 (13.2%) women who had ovarian conservation. Forty-four women with ovarian conservation and four with oophorectomy died from ovarian cancer over 28 years of follow-up (HR=0.06;95%CI, 0.02–0.17). Oophorectomy was associated with higher mortality from CHD (multivariable hazard ratios [HR] HR=1.23;95% confidence interval[CI], 1.00–1.52), lung cancer (HR=1.29;95%CI, 1.04–1.61), colorectal cancer (HR=1.49;95%CI, 1.02–2.18), total cancers (HR=1.16;95%CI, 1.05–1.29) and all-causes (HR=1.13;95% CI, 1.06–1.21). Results were not statistically different for any of the mortality outcomes when stratified by age at hysterectomy. Though there were insufficient numbers to analyze some cause-specific deaths in women age 60 and older, risk estimates associated with bilateral oophorectomy remained elevated for all-cause, total cancer, and CVD mortality in these older women. Among women with hysterectomy before age 50, oophorectomy was associated with significant increases in risk of deaths from CHD, colorectal cancer, total cancers, and all-causes.

Figure 1. Multivariable-adjusteda risks of all-cause and cause-specific deaths for women with bilateral oophorectomy compared with ovarian conservation at time of hysterectomy, stratified by age at hysterectomy.

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; NA, not analyzed due to small numbers

a All models were adjusted for age, age at hysterectomy, body mass index in 1976, smoking status, use of estrogen therapy, past duration of oral contraceptive use, parity, physical activity, alcohol intake and aspirin use. In addition, all-cause death models were adjusted for family history of myocardial infarction before age 60, tubal ligation and family history of breast cancer; breast cancer models were adjusted for tubal ligation and family history of breast cancer; total cancer models were adjusted for tubal ligation; and CHD, stroke and CVD models were adjusted for family history of myocardial infarction before age 60.

b p-value for interaction between oophorectomy status and age at hysterectomy

The median year from study entry to all-cause death is 18.9 and 19.7 for women with ovarian conservation and both ovaries removed respectively. The median year from study entry to all-cause death for all deceased women (n=4,599) is 19.4.

Multivariable analyses comparing models using either linear or linear plus quadratic terms for age at hysterectomy found that oophorectomy prior to age 47.5 years was associated with a lower risk of death from breast cancer (p=0.048). However, similar comparisons for death from coronary heart disease, stroke, lung cancer, colorectal cancer total cancers and all-cause mortality did not demonstrate any age at which oophorectomy was associated with increased survival. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Multivariable-adjusted analyses of all-cause and cause-specific mortality in relation to oophorectomy status, comparing models using either linear or linear+quadratic terms for age at hysterectomy

| Chi-square statistica |

p-value | Age at hysterectomy at which oophorectomy would lower risk |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause death | 0.01 | 0.915 | |

| Breast cancer | 3.90 | 0.048 | 47.5 |

| Lung cancer | 0.79 | 0.375 | |

| Colorectal cancer | 0.12 | 0.724 | |

| Total cancer | 0.80 | 0.372 | |

| Coronary heart disease | 1.73 | 0.188 | |

| Stroke | 0.12 | 0.727 |

from likelihood ratio test comparing linear versus quadratic models

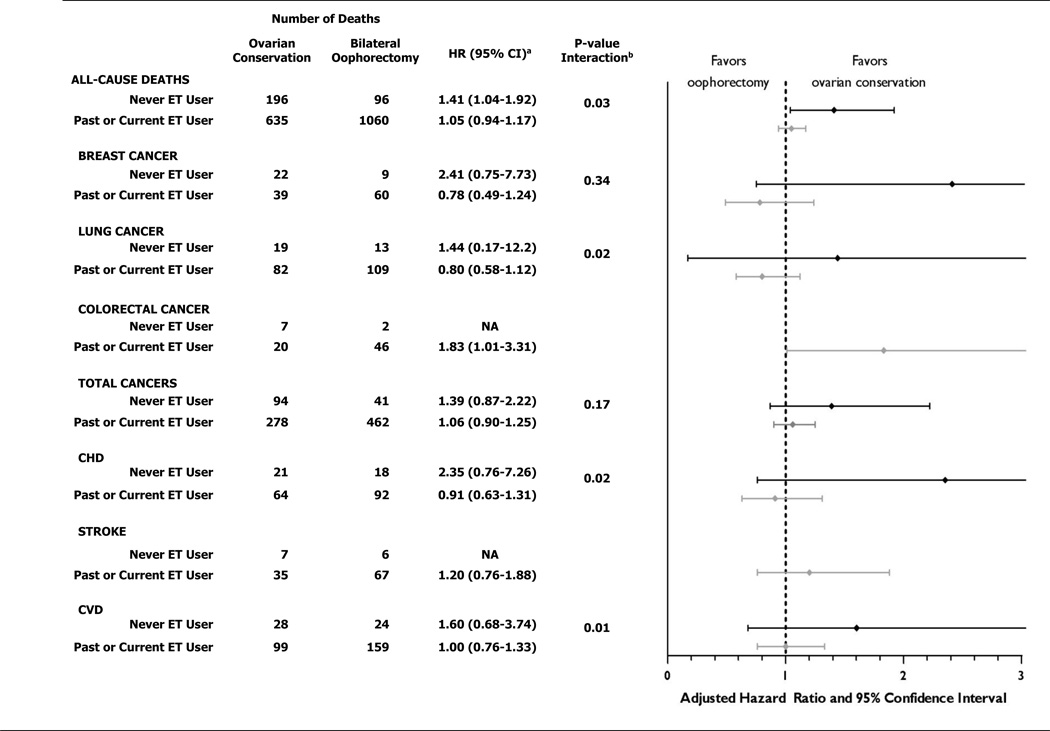

For women younger than 50 at time of hysterectomy, bilateral oophorectomy was associated with significantly increased all-cause mortality in women who had never used ET (HR=1.41;95% CI, 1.04–1.92, number needed to harm [NNH]=8) but not in women who were past or current ET users (HR=1.05; 95% CI, 0.94–1.17). The results in these two categories of ET use were statistically different (Pinteraction=0.03). A statistical difference in results by ET use, with higher risk in the never-users, was also observed for lung cancer mortality (Pinteraction=0.02); and CHD mortality (Pinteraction=0.02). (Figure 2). Number need to harm for lung cancer deaths was 50 and for CHD deaths was 33.

Figure 2. Multivariable-adjusteda risks of all-cause and cause-specific deaths for women with bilateral oophorectomy compared with ovarian conservation at time of hysterectomy before age 50, stratified by use of estrogen therapy.

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ET, estrogen therapy; CHD, coronary heart disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; NA, not analyzed due to small numbers

a see footnote "a" in Figure 1

b p-value for interaction between oophorectomy status and use of estrogen therapy

In the 16,395 women who had a hysterectomy after entering the cohort in 1976 and for whom CVD risk factors were queried, oophorectomy was associated with an increased risk of CVD mortality in the low-risk (HR=1.80; 95%CI, 0.87–3.71), but not in the high-risk women (HR=0.90;95%CI, 0.59–1.38). However, power was low to determine that these risks were statistically different (Pinteraction=0.22). Results were similar for all-cause mortality. In other stratified analyses, all-cause mortality associated with oophorectomy did not differ by smoking status among all women in the study population. However, in the subgroup of women with hysterectomy before age 50 who never used ET, risk was highly elevated in the never-smokers (HR=3.09; 95% CI 1.38–6.44), moderately elevated in the former-smokers (HR=1.83, 95% CI 0.93–3.59), and not elevated in the current-smokers (HR=0.98; 95% CI 0.22–4.35) (Pinteraction=0.18). In a separate analysis, neither total mortality nor breast cancer mortality associated with oophorectomy differed for women with or without a family history of ovarian or breast cancer (in mother or sister). However, our statistical power to evaluate mortality outcomes in high-risk women with a strong family history of these cancers was limited.

To determine whether prolonged follow-up is needed to observe an increase in CVD or all-cause mortality associated with bilateral oophorectomy, we examined women alive and free of CVD 15 years after hysterectomy (n=23,244). Eighty percent of CVD deaths and 80% of all deaths occurred 15 or more years after hysterectomy. For these women, oophorectomy was associated with a higher risk of death from all-causes (HR=1.09; 95%CI, 1.01–1.17) and CVD (HR=1.14, 95% CI 0.95–1.37), similar to what was reported in Figure 1 for the full study population.

Discussion

In this large, prospective cohort of over 30,000 women followed for 28 years, we found that at no age was there an overall survival benefit associated with bilateral oophorectomy compared with ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease. Our analysis of the cohort, including 1,379 additional deaths subsequent to the 2009 NHS publication, found that at the time of hysterectomy bilateral oophorectomy was associated with a marked reduction in mortality from ovarian cancer and a lower risk of mortality from breast cancer when oophorectomy was performed before age 47.5. Among the 30,117 study participants followed over 28 years, 44 women with ovarian conservation and 4 with oophorectomy died from ovarian cancer. However, these risks were overshadowed by the significantly increased risks of dying from other causes: a 23% increase in CHD mortality, a 29% increase in lung cancer mortality, a 49% increase in colorectal cancer mortality and a 13% increase in all-cause mortality.

Additionally, we found that oophorectomy before age 50 in women who never used ET was associated with a 41% increased risk of all-cause mortality. Women who were past or current users of ET did not demonstrate this increased risk. An analysis of the term of interaction confirmed these findings (Pinteraction=0.03). Lung cancer and CVD mortality were also elevated only in the women who never used ET. These findings suggest that ET may ameliorate the increased mortality risks associated with bilateral oophorectomy in younger women.(12)

The finding that oophorectomy did not increase the risks of CVD or all-cause mortality in women with known risk factors for CVD was unexpected and suggests that oophorectomy may not modify the substantial risks these women already incur. However, oophorectomy did increase the risks of CVD and all-cause mortality in low-risk women, suggesting that oophorectomy may have a greater impact on otherwise healthy women. Similarly, for women who never smoked and never used ET, oophorectomy before age 50 was associated with a 200% increase in mortality. We did not find this increased risk in current smokers, possibly because oophorectomy may not modify the established high risk of CVD that is already present among smokers.

That oophorectomy may be associated with increased risk of colorectal cancer is biologically plausible. Estrogen receptors are present in human colorectal tissues and physiological levels of estrogen stimulate humoral and cell-mediated immune response. (13, 14) We continue to find an association of oophorectomy with lung cancer in the NHS cohort. Although our earlier findings on oophorectomy and increased risk of incident lung cancer were unexpected, other studies subsequently found a similar association. (7,15,16) These observations that oophorectomy may affect lung cancer risk merit further investigation.

Our study has a number of strengths. The large size of our study cohort (30,117 women) and long-term follow-up (28 years) are important advantages over other observational studies. The finding in our study that 80% of both CVD deaths and all deaths occurred 15 or more years after hysterectomy points out that prolonged follow-up is essential to observing the effect of oophorectomy on mortality. Study entry of our participants at young ages (range 30 to 55 at NHS enrollment) took place many years before most of the deaths due to conditions of interest. Other strengths include our prospective cohort study design, very high follow-up rate, adjudicated and blinded assessment of all reported deaths, and multivariable analyses to correct for many known risk-factors for the outcomes studied. Additionally, statistical differences between strata were assessed using the significance of interaction term (Pinteraction) which considers the relationship among three or more variables when the simultaneous influence of two variables on a third is not additive.

We acknowledge several limitations of our study. The study is observational and the reasons why women chose oophorectomy/ovarian conservation or ET-use/no ET-use are not known. Differences in the use of medications such as statins, dietary factors, and environmental exposures may have differed by treatment group. However, most baseline characteristics were similar for the two groups, including many known risk-factors for conditions studied. Lastly, our study population was mostly white and our findings may not apply to other ethnic groups.

While our findings suggest that estrogen therapy ameliorates the elevated risks of all-cause and CVD mortality associated with oophorectomy before age 50, the number of women currently taking estrogen continues to decline following the Women’s Health Initiative. (19) Therefore, a strategy of performing oophorectomy and prescribing estrogen after surgery is not likely to be successful. Alough challenging, a prospective trial, randomized to oophorectomy or ovarian conservation with prolonged follow-up, is needed to confirm our findings. Lacking such a trial, high-quality observational studies provide a valuable method to evaluate these associations.

At the time of hysterectomy, women with known high-penetrance susceptibility genes for ovarian and breast cancer (BRCA, Lynch) should strongly consider oophorectomy because the life-time risk of ovarian cancer is high.(20) In contrast, approximately 300,000 US women without these mutations, and many more world-wide, have bilateral oophorectomy at the time of hysterectomy for benign disease every year. Consequently, the association of oophorectomy with increased mortality in the overall population has substantial public health implications.

Acknowledgments

Study funding: NIH grant for data collection and cohort maintenance for NHS: CA87969 and HL34594 from the National Institutes of Health; study grants from Ethicon, Inc and Partnership for Health Analytic Research. Ethicon, Inc. had no role in the design and conduct of the study. Dr. Michael Broder is President of Partnership for Health Analytic Research and was involved in the study design, data analysis and editing of the manuscript. Eunice Chang is a biostatistician at Partnership for Health Analytic Research and was involved in data analysis.

Footnotes

Study design: Parker, Broder, Feskanich, Manson. Data acquisition and analysis: Chang, Feskanich. Data interpretation: Feskanich, Manson, Parker, Broder, Farquhar. Preparation and revision of manuscript: Parker, Manson, Feskanich, Broder, Berek, Farquhar, Shoupe.

Contributor Information

William H. Parker, John Wayne Cancer Institute, Santa Monica, CA, wparker@ucla.edu.

Diane Feskanich, Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston MA, diane.feskanich@channing.harvard.edu.

Michael S. Broder, Partnership for Health Analytic Research, LLC, Beverly Hills, CA, mbroder@PHARLLC.com.

Eunice Chang, Partnership for Health Analytic Research, LLC, Beverly Hills, CA, echang@pharllc.com.

Donna Shoupe, Keck School of Medicine at the University, of Southern California, shoupe@usc.edu.

Cynthia M. Farquhar, University of Auckland, Auckland, NZ, C.farquhar@auckland.ac.nz.

Jonathan S. Berek, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Director, Stanford Women's Cancer Center, Stanford Cancer Institute, jberek@stanford.edu.

JoAnn E. Manson, Division of Preventive Medicine Brigham, and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Mass. jmanson@rics.bwh.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Jamieson DJ, Morrow B, Podgornik MN, Brett KM, Marchbanks PA. Inpatient hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 2000–2004. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:34.e1–37.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asante A, Whiteman MK, Kulkarni A, Cox S, Marchbanks PA, Jamieson DJ. Elective oophorectomy in the United States: trends and in-hospital complications, 1998–2006. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1088–1095. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f5ec9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colditz GA, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Speizer FE, Hennekens CH. Menopause and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1105–1110. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704303161801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rocca WA, Grossardt BR, de Andrade M, Malkasian GD, Melton LJ., 3rd Survival patterns after oophorectomy in premenopausal women: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:821–828. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70869-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacoby VL, Grady D, Wactawski-Wende J, Manson JE, Allison MA, Kuppermann M, Sarto GE, Robbins J, Phillips L, Martin LW, O'Sullivan MJ, Jackson R, Rodabough RJ, Stefanick ML. Oophorectomy vs ovarian conservation with hysterectomy: cardiovascular disease, hip fracture, and cancer in the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:760–768. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duan L, Xu X, Koebnick C, Lacey JV, Jr, Sullivan-Halley J, Templeman C, Marshall SF, Neuhausen SL, Ursin G, Bernstein L, Henderson KD. Bilateral oophorectomy is not associated with increased mortality: the California Teachers Study. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker WH, Broder MS, Chang E, Feskanich D, Farquhar C, Liu Z, Shoupe D, Berek JS, Hankinson S, Manson JE. Ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy and long-term health outcomes in the nurses' health study. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:1027–1037. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a11c64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colditz GA, Manson JE, Hankinson SE. The Nurses' Health Study: 20 year contribution to the understanding of health among women. J Womens Health. 1997;6:49–62. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1997.6.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colditz G, Stampfer M, Willett W, Stason W, Rosner B, Hennekens C, et al. Reproducibility and validity of self-reported menopausal status in a prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;126:319–325. doi: 10.1093/aje/126.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Speizer FE, et al. Test of the National Death Index. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;119:837–839. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parrish HM, Carr CA, Hall DG, King TM. Time interval from castration in premenopausal women to development of excessive coronary atherosclerosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1967;99:155–162. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(67)90314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rivera CM, Grossardt BR, Rhodes DJ, et al. Increased cardiovascular mortality after early bilateral oophorectomy. Menopause. 2009;16:15–23. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31818888f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison JD, Watson S, Morris DL. The effect of sex hormones and tamoxifen on the growth of human gastric and colorectal cancer cell lines. Cancer. 1989;63:2148–2151. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890601)63:11<2148::aid-cncr2820631113>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovacs EJ, Messingham KA, Gregory MS. Estrogen regulation of immune responses after injury. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;193:129–135. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brinton LA, Gierach GL, Andaya A, Park Y, Schatzkin A, Hollenbeck AR, Spitz MR. Reproductive and hormonal factors and lung cancer risk in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:900–911. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koushik A, Parent ME, Siemiatycki J. Characteristics of menstruation and pregnancy and the risk of lung cancer in women. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2428–2433. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sprague BL, Trentham-Dietz A, Cronin KA. A sustained decline in postmenopausal hormone use: results from the national health and nutrition examination survey, 1999–2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:595–603. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318265df42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gayther SA, Pharoah PD. The inherited genetics of ovarian and endometrial cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]