Abstract

Research shows that peer status in adolescence is positively associated with school achievement and adjustment. However, subculture theories of juvenile delinquency and school-based ethnographies suggest that (1) disadvantaged boys are often able to gain some forms of peer status through violence and (2) membership in violent groups undermines educational attainment. Building on these ideas, we use peer network data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) to examine whether peer status within highly violent groups increases male risks of high school dropout. Consistent with the subcultural argument, we find that disadvantaged boys with high status in violent groups are at much greater risks of high school dropout than other students.

Social scientists consistently find that peer acceptance, or sociometric status, is positively related to school achievement and adjustment during adolescence (Newcomb, Bukowski, and Pattee 1993; Rubin, Bukowski, and Parker 1998; Wentzel and Caldwell 1995; 1997). However, recent research also suggests that some aggressive, “antisocial,” boys are able to acquire prestige or notoriety in school-based peer networks, particularly in disadvantaged settings (Estell, Farmer, Pearl, Van Acker, and Rodkin 2003; Farmer, Estell, Leung, Trott, Bishop, and Cairns 2003; Luthar and McMahon 1996; Rodkin, Farmer, Pearl, and Acker 2000; Xie, Farmer, and Cairns 2003). The latter findings fit well with subculture theories of juvenile delinquency because they suggest that violence and aggression provide means for disadvantaged boys to earn respect, prove their masculinity, and meet peer expectations (Anderson 1999; Cloward and Ohlin 1960; Cohen 1955; Hagan 1993; MacLeod 1987; Messerschmidt 1993; Miller 1958; Shaw 1931; Thrasher 1927; Willis 1977; Wolfgang and Farracuti 1967). What remains unclear, however, is whether peer status within violent groups also compromises educational attainment. For some youth, status gained in violent groups may provide short-term benefits that fade with time and foreclose future opportunities for upward mobility. Prestige in an alternative status system could then be an important mechanism for understanding the links between childhood aggression and longer-term educational attainment (Cairns, Cairns, and Neckerman 1989; Ensminger and Slusarcick 1992; Moffitt et al. 2002).

In this study, we use peer network data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health) to investigate whether peer status within violent groups increases male risks of high school dropout. Drawing on subculture theories of delinquency, we test whether the relationship between peer status and male dropout varies by students’ socioeconomic backgrounds and peer contexts (Anderson 1999; Cohen 1955; MacLeod 1987; Willis 1977). Does prestige in an alternative status system encourage disadvantaged boys to exit school? Unlike previous research, we examine this question with measures of peer status collected directly from school-based friendships, thereby overcoming bias associated with self-reported popularity measures. This, along with Add Health’s detailed individual measures and longitudinal design, allow us to extend prior research and bridge central educational and criminological concepts.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

Sociologists have long studied the factors associated with high school dropout, such as family structure (Astone and McLanahan 1991; McNeal 1999), residential and school mobility (Astone and McLanahan 1994; South, Haynie, and Bose 2007), teenage work experiences (Lee and Staff 2007), extracurricular activities (McNeal 1995), and childhood academic engagement (Alexander, Entwisle, and Horsey 1997). Several studies have also looked at the relationship between peer status and school success, typically finding that students with high peer acceptance are more likely to get good grades and achieve greater educational attainment than less popular peers (Parker and Asher 1987). However, a review of the latter literature suggests that peer effects may vary by social context, and that not all friendships or peer connections contribute to school success

PEER STATUS AND HIGH SCHOOL DROPOUT

For many reasons, popular students should have lower risks of school dropout than their less-popular peers. Adolescents place primary importance on peer status during the high school years (Brown 2004). Popular youth may therefore enjoy school because it affords them opportunities to mingle with their friends and be seen as “cool.” The beneficial effects of popularity on school retention are likely to hold even for students with little interest in academic success. As Coleman (1961) found in his seminal study of adolescent culture, access to the “leading crowds” often hinges on non-scholastic criteria – such as physical attractiveness, athletic ability, or material possessions – that limit connections between popularity and academic achievement. It could therefore be the rewards of peer acceptance, and not teacher praise, good grades, or high expectations, that keep popular students involved in school. By contrast, youth who are disconnected from peers may have higher rates of school failure because they are less likely to (1) participate in classroom learning activities, teacher-initiated class requirements, and athletics or other extracurricular activities; (2) develop a positive identification with school; or (3) ask and receive help from teachers on homework and exams (Wetzel 1991). Although research shows that middle-school students who are neglected by peers frequently have good academic profiles (Wentzel and Asher 1995) and often gain friends as they move into high school (Kinney 1993), those who remain marginalized are likely to find school alienating and unpleasant. In support of the latter view, educational research has found that high school dropouts frequently report feelings of social isolation and a lack of belongingness prior to leaving school (Finn 1989).

There appears little disagreement that, in the aggregate, popularity is positively associated with school completion. For example, Farmer et al. (2003) recently found that adolescents who are rated as popular by teachers are more than twice as likely to graduate from high school as non-popular youth. The authors also found that the effect of popularity on high school completion is not conditioned by belonging to an aggressive peer group, such that popular youth are no more likely than unpopular youth to dropout if they belong to an aggressive group. However, Farmer et al. (2003) did not explore the potential conditional effects of social class on the relationship between aggression, popularity, and school dropout. Recent research suggests that the effects of peer status and violence may vary substantially by social context and students’ socioeconomic backgrounds. Research on urban and disadvantaged schools finds that many violent males are able to garner the respect of some peers while simultaneously being disliked by others (Luther and McMahon 1996; Rodkin, Farmer, Pearl, and Acker 2000; Xie, Cairns, and Cairns 1999; Xie, Farmer, and Cairns 2003). These “controversial” youth fit well with subculture theories of juvenile delinquency (Cohen 1955) and qualitative research of student oppositional cultures (Anderson 1999; MacLeod 1987; Willis 1977) because they suggest that violence can be a status resource for some disadvantaged males. Moreover, status gained in violent groups may provide a mechanism for school dropout only among poor males. To explore these ideas, we turn our attention to longstanding subcultural perspectives of crime and education.

DELINQUENT BOYS, PEER STATUS, AND HIGH SCHOOL DROPOUT

In Delinquent Boys, Cohen (1955) suggested that boys from lower-class families are unprepared to compete in an educational system oriented toward middle-class values. He argued that school failure and frustration motivate lower-class boys to join oppositional subcultures that embrace and reward violence and aggression. Within the delinquent subculture, violence is an achievable status criterion that delinquent boys use to flout conventional peers and teacher authority. Although not all lower-class boys join the oppositional subculture (e.g., college boys and corner boys), those who do are expected to seek status through violence, effectively ending their school careers and removing future opportunities for upward mobility.

Although stemming from a markedly different theoretical tradition, Willis (1977) reached similar conclusions regarding the relationship between peer status, violence, and socioeconomic attainment (Davies 1999). In his theory of school resistance, Willis (1977) extended the work of critical education scholars (e.g. Bowles and Gintis 1976; Bourdieu and Passeron 1977) and asserted that many working-class boys actively draw on their cultural experiences to “see through” an educational system of dubious value for their future occupational expectations. Based on ethnographic research of English youth during the early 1970’s, Willis observed that many of the working-class boys in his sample (i.e., the “lads”) created a culture in which violence, and not school success, was the important criterion for peer status. Willis (1997) noted that “the fight is the moment when you are fully tested in the alternative culture. It is disastrous for your informal standing and masculine reputation if you refuse to fight, or perform very amateurishly…it is the not often tested ability to fight which valorizes status” (p. 35). Willis argued that peer status within the counter-school subculture helped to smooth the transition to an informal shop-floor culture similarly defined by aggressiveness, masculinity, and opposition to authority. Although many of the “lads” were eager to leave school early and pursue full-time manual labor, these youth later viewed education “retrospectively, and hopelessly, as the only escape” from their low-status jobs (Willis 1997; p. 107).

Ethnographic studies of U.S. youth similarly highlight the importance of violence as part of an alternative status system for disadvantaged boys who have little interest in school. For instance, in MacLeod’s (1987) Ain’t No Makin’ It, fighting ability was “the deciding factor for status demarcation within the group” of white, low-income boys comprising the “Hallway Hangers” (p. 27). For these boys, peer status in a violent group compensated for the belief that status would never be gained through education, especially given the limited prospects of good jobs in their neighborhoods. Many of the Hallway Hangers dropped out of high school because they believed “the possibility of upward social mobility is not worth the price of obedience, conformity, and investment of substantial amounts of time, energy, and work in school” (p. 104). Likewise, Anderson (1999) documented a similar relationship between peer status, violence, and high school dropout among poor African-American boys residing in low-income neighborhoods. Anderson observed that boys in these neighborhoods often gained peer status through violence or the display of a predisposition for violence (i.e., by following the code of the street). Adopting this violent street code not only leads to higher levels of victimization (Stewart, Schreck, and Simons 2006), but also provides an alternative source of peer status that pulls students away from school. As Anderson (1999) noted, “when students become convinced that they cannot receive their props from teachers and staff, they turn elsewhere, typically to the street, encouraging others to follow their lead” (p. 97).

SELF-SELECTION AND SPURIOUSNESS

School resistance and subcultural arguments rest on the idea that disadvantaged boys who adopt oppositional values are pulled out of school and into dead-end jobs or criminal lifestyles. Accordingly, status gained in the oppositional culture is expected to have direct effects on educational and occupational attainment. However, an alternative conception of this relationship is that both peer status and attainment are explained by stable underlying traits, such as a propensity toward aggression or anti-social personality disorder. Moffitt (1993), in her typological theory of delinquency, suggests that childhood neuropsychological deficits place a small number of youth on developmental pathways toward persistent offending and low conventional attainment. During adolescence, Moffitt (1993) argues that the precocious behaviors of these “life-course persistent” offenders are venerated by peers, making the early delinquent a social magnet and central actor in delinquent groups. However, it is early cognitive deficits, and not later delinquency or peer status, which cause persistent offender’s to have negative life outcomes. Discerning between this argument of a spurious relationship and the subcultural hypothesis will be a central focus of the current paper.

In summary, subculture theories and prior research suggest that boys from low socioeconomic backgrounds are expected to place greater value on violence than are other youth, particularly if they are doing poorly in school or if they have low educational expectations. By contrast, boys from more advantaged family backgrounds, are unlikely to resort to violence for increased peer status because such behaviors would undermine conventional attainment and are unnecessary for achieving valued gendered identities (Messerschmidt 1993). For boys from low-income families, blocked opportunities for achieving culturally valued masculine ideals (i.e., through educational and economic attainment) encourage alternative status criteria centered on oppositional and often violent behavior. Furthermore, we suspect that boys from low SES backgrounds are the most likely of any demographic group to drop out of school because only they have the opportunity to draw upon an alternative and oppositional status system. We test this idea with detailed data from a national sample of youth. In addition, we explore potential selection and spurious relationship arguments with strong controls for prior behavior and related individual characteristics.

DATA

We test our hypotheses using data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health). Add Health is a nationally representative longitudinal study of adolescents in grades 7 to 12. From 1994 to 2001, the study collected four waves of student data, with additional surveys administered to parents, siblings, and school administrators. In the current analyses, we rely on data from the first two student surveys (e.g. the in-school and first in-home interviews), collected in 1994–95, and the fourth survey, collected seven years later in 2001.

At the first wave, 80 high schools were selected with probabilities proportional to size. These schools were stratified by region, urbanicity, sector (private vs. public), percent white, and size. For those high schools not covering grades 7–12, a nearby middle school was also sampled, creating a final sample of 145 schools. In one class period during the fall of 1994, Add Health administered in-school surveys to all available students in each of the sampled schools. Approximately 80% of enrolled students (N=90,118) were surveyed. The questionnaire asked respondents about basic demographic and behavioral characteristics. Students also nominated their five best male and five best female friends. Sixteen schools had less than 50% of their enrolled students complete the nomination portion of the survey. These schools were not included in the analyses, leaving 75,871 students in 129 schools with valid network information. The nomination data allow for the construction of peer-reported network measures, thus avoiding possible measurement error resulting from self-reported friendship characteristics. Moreover, Add Health’s network items allow us to measure two concepts central to the study of youth subcultures and achievement – students’ social prominence and the violent behaviors of their friends.

Approximately six months after the in-school survey, Add Health selected a stratified subsample of students to complete a more extensive in-home interview. 14,396 students completed both the in-school and first in-home surveys. To ensure confidentiality, sensitive questions were administered using portable laptops and headphones. Seven years after the in-home survey, respondents were re-interviewed and asked questions about their educational and occupational attainment. 14,322 students completed the third in-home interview. Of these, 5,066 male respondents completed the in-school, first in-home, and third in-home questionnaires. We focus on males because the hypothesis derived from subculture theories applies only to males. We also include a weight provided by the Add Health researchers (Chantala and Tabor 1999) to adjust for sample attrition, stratification, and non-response among enrolled students during the in-school survey administration.

Of the 5,066 male respondents who were not lost to attrition, approximately 6 percent of students attended a school that did not complete the network portion of the interview and 786 students were missing information regarding their socioeconomic origins. Furthermore, one respondent did not report his educational attainment in adulthood. Of the remaining 4,032 male respondents, approximately 25% of these students were missing information on at least one of our predictor variables (e.g. race and ethnicity, family structure, grades, school effort, expectations, fighting, or standardized test scores). To assess whether missing data on these measures might affect our results, we examined if students with missing data had a higher rate of school dropout than those youth who were not missing information. The correlation between high school dropout and an indicator of missing data was modest but statistically significant (r = .14; p<.05).

To address potential bias resulting from missing data, we used multiple imputation techniques in the statistical package Stata (the ICE procedure) to regain a nationally representative sample of young adult males (Royston 2005). After imputation, our analysis sample included 5,065 males, 4,539 of which received at least one friendship nomination necessary for constructing measures of peer characteristics.

MEASURES

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for our measures before and after multiple imputation. We impute values into five datasets, with all independent and dependent measures included in the imputation procedure (Rubin 1996).1 An advantage of the ICE procedure is that it uses an iterative multivariable regression algorithm that detects the distributions of model variables and applies the appropriate regression technique (e.g. OLS, logistic, or ordered logistic) in calculating imputed values. This switching algorithm limits occasions where imputed values fall outside of the range of observed values and are in the same metric. Looking at Table 1, we see that variable means and standard deviations are not substantially different between the observed and imputed datasets.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Males

| Variable | Description | Observed Data | Imputed Data | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | N | Mean | SD | ||

| High School Dropout | Binary measure of failure to receive a high school diploma | 5,065 | .16 | 5,065 | .16 | ||

| Sociodemographic Variables | |||||||

| Grade level | Grade level in 1994 | 5,031 | 9.65 | 1.61 | 5,065 | 9.65 | 1.61 |

| Hispanic | Dummy variable for Hispanic origin | 5,065 | .19 | 5,065 | .19 | ||

| Black | Dummy variable for black race | 5,065 | .20 | 5,065 | .20 | ||

| Asian | Dummy variable for Asian ancestry | 5,065 | .11 | 5,065 | .11 | ||

| Intact family | Dummy variable indicating residing with both biological parents | 4,852 | .74 | 5,065 | .74 | ||

| Low parent education | Both parents lack education beyond the high school level | 4,280 | .37 | 5,065 | .40 | ||

| Individual Characteristics | |||||||

| Fighting | Number of fights over the last year | 4,525 | .98 | 1.20 | 5,065 | .97 | 1.20 |

| Grades | Mean GPA in four subjects | 4,431 | 2.73 | .81 | 5,065 | 2.72 | .81 |

| Middle-Class Expectations | Response to the question, “What do you think are the chances you will have a middle-class family income by age 30?” | 4,587 | 5.11 | 2.34 | 5,065 | 5.06 | 2.34 |

| School Effort | Response to the question, “How hard do you try to do your school work well?” | 4,823 | 3.16 | .71 | 5,065 | 3.17 | .71 |

| Athlete | Respondent participated in a sport during the prior year | 5,065 | .62 | 5,065 | .62 | ||

| Picture Vocabulary Score | Standardized score on Peabody-revised picture vocabulary test | 4,809 | 101.20 | 14.69 | 5,065 | 101.16 | 14.69 |

| Peer Network Characteristics | |||||||

| Peer Status | Number of friendship nominations received from students in school or sister school | 4,756 | 4.26 | 3.78 | 5,065 | 4.28 | 3.78 |

| Friends’ GPA | Friends’ GPA in four subjects (mean) | 4,147 | 2.81 | .58 | 5,065 | 2.79 | .58 |

| Friends’ Fighting | Number of fights by friends (mean) | 4,149 | .75 | .70 | 5,065 | .75 | .70 |

| Friends’ Middle-Class Expectations | Friends’ expected middle-class family income (mean) | 4,207 | 5.09 | 1.52 | 5,065 | 5.06 | 1.50 |

EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT

Our primary outcome variable indicates whether respondents dropped out of high school prior to earning a diploma. Students who later received a Graduate Equivalency Degree (GED) were coded as having dropped out of high school.2 The dropout variable is taken from the 2001 survey, providing adequate time for the 1994 cohort to graduate. As shown in Table 1, the mean number of Add Health students who dropped out was approximately 16 percent. The nationwide “status” dropout rate, excluding youth who later received GED credentials, for males aged 16–24 in 1994 was 12.3 percent (U.S. Department of Education 2006).

Although we are primarily interested in predictions of high school dropout, we also assessed educational attainment using measures of years of education (ranging from 7 to 22 years) and receipt of a four-year baccalaureate degree (coded 1=BA/BS degree recipient; 0=no degree). Again, to provide adequate time for college graduation, these alternative measures of educational attainment were constructed only for youth who were juniors or seniors in high school at the first wave of data collection. We derived the college graduation and years of education measures from the 2001 follow-up survey.

PEER NETWORK CHARACTERISTICS

Our key predictor variables are adolescent peer status and friends’ violence, grades, and income expectations. During the in-school survey (1994), students in the sampled schools nominated their five best male and five best female friends. Peer status is measured as the total number of friendship nominations that an individual receives from other students in the high school or associated middle school (Wasserman and Faust 1994). This measure is an ego-centric count measure of received friendship nominations ranging from 0 to 30 with the average popularity equaling 5 nominations.3 Boys with no received friendship nominations (N=526) lacked values for friends’ characteristics and were excluded from the descriptive statistics and analyses of the subcultural hypothesis.

The characteristics of friends are measured from the average values of an item across all students in an individuals’ receive network. The measure of friends’ violence thus captures the average level of violence among an individual’s friends with possible values ranging from 0, when none of the respondent’s friends report fighting, to 4, when all friends report getting into 7 or more fights in the last year. We also include measures of friends’ grades and middle-class aspirations. The measure of friends’ grades is the average GPA of the respondent’s friends (based on a four-point scale ranging from 1, “D or lower,” to 4, “A”). The measure of friends’ income expectations indicates the average response of the respondent’s friends to the question: “what do you think are the chances you will have a middle-class family income by age 30?” (based on a nine-point scale ranging from “no chance” to “it will happen”). Higher scores indicate that most of the respondent’s friends expect to earn a middle-class income in adulthood.

INDIVIDUAL CHARACTERISTICS

To gain leverage on potential sources of spuriousness, we include indicators of the respondent’s prior violence, school performance, income expectations, school effort, academic ability, and athletic participation. The respondent’s frequency of fighting in the prior year is measured on a 4-point ordinal scale ranging from “none” to “more than seven times.” Grades indicate the average of student-reported GPAs in four subjects – math, English, social studies, and science. Similar to the network data, this measure is based on a four-point scale ranging from 1, “D or lower,” to 4 “A”. Middle-class income expectations refer to the chances the respondent believes that he will have a “middle-class” family income by age 30 (coded on a nine-point scale ranging from 1, “no chance,” to 9, “it will happen”). School effort indicates how hard the respondent tries to do their school work well (coded on a four-point scale from 1, “I never try at all,” to 4, “I try very hard to do my best”). Add Health investigators measured academic aptitude with a vocabulary test in the first in-home interview (1995). Respondents completed a picture vocabulary test (abridged Peabody-revised) in which students selected an illustration that best matched a word spoken by the interviewer. Results were standardized by age and provide an instrument with consistent properties (Dunn and Dunn 1981). Finally, we include a measure of whether the respondent participated in a sport during the prior year (e.g., baseball/softball, basketball, field hockey, football, ice hockey, soccer, swimming, tennis, track, volleyball, wrestling, and other sports). Research finds that athletic participation is positively associated with peer status (Coleman 1961; Holland and Andre 1994) and negatively associated with high school dropout (McNeal 1995). These relationships may confound any association between violence, peer status, and dropout, making it necessary to control for athletics in our analyses.

SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC VARIABLES

Our final set of measures captures students’ family and background characteristics. We measure the respondent’s socioeconomic origins from two student-reported items of mother’s and father’s educational attainment in 1994. Each parent had educational values ranging from 1, indicating less-than high school education, to 5, indicating education beyond a four-year degree. To indicate low parent education, we take the highest of the mother’s and father’s educational attainment and create a binary variable coded as 1 if neither parent had pursued schooling beyond high school, and 0 otherwise. As shown in Table 1, approximately 40 percent of the boys come from families where neither parent is educated beyond a high school level.

As noted above, many of the delinquent subculture theorists predict that boys from lower class backgrounds (and not necessarily boys whose parents have low levels of education) are most likely to gain peer status through their aggressive behavior. In the Add Health study, respondents were asked about their parents’ occupation, but unfortunately we could not use this information to accurately construct measures of social class origins. Respondents were asked to pick among fifteen occupational categories that “come closest to describing the mother’s or the father’s job.” The occupational categories were crude (based on a fifteen-point scale ranging from homemaker to professional worker); the percentage of missing values on parent’s job were high; and four times as many respondents were unsure of their mother’s occupation as their mother’s highest level of schooling. The high numbers of missing values, coding ambiguity, potential measurement error, and non-linearities between constructed occupational scales and the outcome reduced our confidence in using these measures in our analyses.

The parents of the Add Health respondents were also asked to report their highest level of education (but not their occupations if they were currently employed). The primary reason we did not use parent-reported educational attainment is that over 15 percent of parents did not complete the parent survey. Furthermore, in analyses not shown, we found that the correlation between the mother-reported educational measure and the student-reported measure of mother’s education was .846.4

We included the respondents’ grade level in 1994 as a predictor variable because students in the lower grades were at risk of dropout for more years than students in higher grades.4 We created dummy variables for race and ethnic background from the in-home surveys. Respondents were allowed to mark more than one racial category, but were then asked which category best describes their racial background. We thus were able to create mutually exclusive dummy variables for Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, and non-Hispanic Asian. Non-Hispanic whites and “Other Race” (the latter consisting of less than 3 percent of the sample) are the reference category for our analyses. Intact family is generated from respondents’ reports that they resided with both their biological mother and biological father in 1994.

RESULTS

Add Health’s stratified sampling design necessitates adjustments to correct for correlated error structures and to gain population estimates. Correlated errors result from students in the same schools being more similar than students in dissimilar schools. Failure to correct for this correlation will result in inefficient parameter estimates. In addition, Add Health’s oversamples of racial, ethnic, disabled, and sibling students results in a non-representative sample of American adolescents. To regain population estimates and correct for the correlated error structure, we estimated all of our models using the SURVEY commands in Stata 8 (StataCorp 2003). This methodology relies on post-sampling weights and the hierarchical structure of the data to provide population estimates with unbiased standard errors.

We present the empirical findings in three parts. First, we estimate logistic regression models to assess whether boys with (more) friends are less likely to drop out of high school than boys who have no friends. Second, to examine whether the effects of peer status differed across friendship networks, we create a product term of the peer status measure and the measures of friends’ violence. We use this term in logistic regression models to examine whether peer status has differential impacts on the risk of high school dropout across varying levels of friends’ violence. We also estimate these models separately for youth from high and low SES backgrounds (based on their parents’ highest educational degree). Finally, we estimate OLS and logistic regression models to examine whether friends’ violence conditions the effect of peer-status on longer-term educational attainment (e.g., years of schooling and 4-year college graduation). These models are restricted to boys who were in the 11th and 12th grades during the first year of survey administration. We also estimated the latter models separately for boys from high and low SES backgrounds.

PEER STATUS AND HIGH SCHOOL DROPOUT

Our first goal is to document the positive relationship between peer status and male high school completion. Table 2 presents logistic regression estimates for the effects of peer status and other explanatory variables on male high school dropout. The reference category for the peer status dummy variables is males with no friendship nominations. As shown in Table 2, peer status has a negative and monotonic effect on high school dropout. Youth with greater numbers of friendship nominations are significantly less likely to drop out of high school than are youth with no nominations or only 1–2 nominations. The odds of dropout are lowest for the most popular youth (who received seven or more friendship nominations). Thus, in keeping with the findings of most prior research, our measure of peer status has a positive association with educational attainment. We also find that boys from non-intact families and whose parents had a high school degree or less are more likely to drop out of high school than are boys from more advantaged backgrounds.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Estimates Predicting Male High School Dropout

| Peer Status (vs. no friends) | b | (SE) | exp(b) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 friends | −.027 | (.204) | .97 |

| 3–6 friends | −.383 * | (.191) | .68 |

| 7 or more friends | −.613 ** | (.225) | .54 |

| Sociodemographic Variables | |||

| Grade level | −.273 *** | (.039) | .76 |

| Hispanic | .318 | (.166) | 1.37 |

| Black | .242 | (.196) | 1.27 |

| Asian | −.012 | (.276) | .99 |

| Intact family | −.512 *** | (.121) | .60 |

| Low parent education | .902 *** | (.141) | 2.46 |

| Intercept | 1.009 * | (.453) | |

| Sample size | 5,065 | ||

Note.

p <.001,

p <.01,

p <.05

PEER STATUS, VIOLENCE, AND HIGH SCHOOL DROPOUT

Next, we assess whether status in violent networks affects the odds of high school dropout. As Table 3 indicates, peer status is associated with lower chances of high school dropout for popular boys (Model 1), even after controlling for race and ethnicity, socioeconomic background, family structure, and grade level. Note also that our sample size decreases by 526 students who had no peer friendship nominations (from 5,065 to 4,539).

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Estimates Predicting High School Dropout Among Males with Friends

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Socioeconomic Origins | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Parent Education | High Parent Education | |||||||||||

| Model 3a | Model 3b | |||||||||||

| b | (SE) | b | (SE) | b | (SE) | b | (SE) | exp(b) | b | (SE) | exp(b) | |

| Peer Network Characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Peer Status | −.073 *** | (.018) | −.053 * | (.020) | −.093 * | (.035) | −.166 * | (.072) | .85 | −.018 | (.050) | .98 |

| Friends’ GPA | −.250 * | (.117) | −.248 * | (.117) | −.241 | (.169) | .79 | −.295 | (.203) | .74 | ||

| Friends’ Fighting | .127 | (.089) | −.007 | (.128) | −.224 | (.172) | .80 | .274 | (.201) | 1.31 | ||

| Friends’ Middle-Class Expectations | .000 | (.039) | −.001 | (.040) | .021 | (.060) | 1.02 | −.039 | (.060) | .96 | ||

| Peer Status * Friends’ Fighting | .046 | (.031) | .119 * | (.054) | 1.13 | −.049 | (.051) | .95 | ||||

| Sociodemographic Variables | ||||||||||||

| Grade Level | −.264 *** | (.040) | −.280 *** | (.042) | −.274 *** | (.042) | −.308 *** | (.056) | .73 | −.226 ** | (.068) | .80 |

| Hispanic | .275 | (.182) | −.041 | (.181) | −.044 | (.181) | .102 | (.239) | 1.11 | −.477 | (.383) | .62 |

| Black | .229 | (.193) | −.188 | (.197) | −.195 | (.196) | −.206 | (.284) | .81 | −.212 | (.315) | .81 |

| Asian | .036 | (.306) | .130 | (.352) | .123 | (.352) | .061 | (.473) | 1.06 | .176 | (.442) | 1.19 |

| Intact Family | −.571 *** | (.114) | −.370 ** | (.120) | −.371 ** | (.120) | −.540 ** | (.186) | .58 | −.191 | (.229) | .83 |

| Low Parent Education | .848 *** | (.144) | .435 * | (.155) | .429 * | (.155) | ||||||

| Individual Characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Fighting | .176 ** | (.055) | .176 ** | (.054) | .157 | (.080) | 1.17 | .219 ** | (.076) | 1.24 | ||

| Grades | −.715 *** | (.103) | −.711 *** | (.104) | −.860 *** | (.178) | .42 | −.568 ** | (.186) | .57 | ||

| Middle-Class Expectations | −.024 | (.027) | −.022 | (.027) | −.013 | (.041) | .99 | −.035 | (.041) | .97 | ||

| School Effort | −.245 * | (.092) | −.242 * | (.092) | −.180 | (.148) | .83 | −.310 * | (.136) | .73 | ||

| Athlete | −.491 *** | (.128) | −.489 *** | (.130) | −.651 ** | (.193) | .52 | −.276 | (.227) | .76 | ||

| Picture Vocabulary Score | −.029 *** | (.006) | −.029 *** | (.006) | −.028 *** | (.007) | .97 | −.032 ** | (.009) | .97 | ||

| Intercept | 1.026 * | (.432) | 7.506 *** | (.970) | 7.542 *** | (.974) | 8.571 | (1.156) | 7.166 *** | (1.452) | ||

| Sample size | 4,539 | 4,539 | 4,539 | 1,787 | 2,752 | |||||||

Note .

p <.001,

p <.01,

p <.05

Model 2 includes measures of the respondent’s grades, middle-class aspirations, school effort, ability, athletic participation, fighting, and measures of friends’ fighting, grades, and aspirations. Not surprisingly, youth who have high grades and test scores, who play sports, and who give effort in the classroom are more likely to graduate from high school than youth who have lower grades and test scores, who do not play sports, and who give little effort in the classroom. Middle-class income expectations are unrelated to high school dropout, which is also not surprising given that most youth today expect to earn a college degree and many youth aspire to work in a professional job in adulthood (Schneider and Stevenson 1999). Overall, the behavior and attitudes of the boys’ friends also have little effect on their own chances of high school completion. We therefore find no evidence that, in the aggregate, boys who are embedded in violent social networks are more likely to drop out of school.

In Model 3, we include a product term capturing the interaction of friends’ fighting with peer status to assess whether peer status in violent crowds affects the chances of high school dropout. The interaction effect of friends’ violence * peer status is statistically non-significant. However, subculture theorists and prior research suggest that boys from disadvantaged backgrounds are the most likely to derive peer status within violent groups (e.g., Cohen 1955; Willis 1977). To test this conditional expectation, we estimate Model 3 for boys from families with high and low levels of parental education. As shown in Model 3a, among boys from low educated families, the effect of peer acceptance on high school dropout is conditioned by friends’ violence. Even after we control for self-reported fighting and prior school success, we find that peer status within a group of violent friends increases the risk of high school dropout for low SES males. The interaction effect is statistically non-significant for boys from more educated families (Model 3b).6

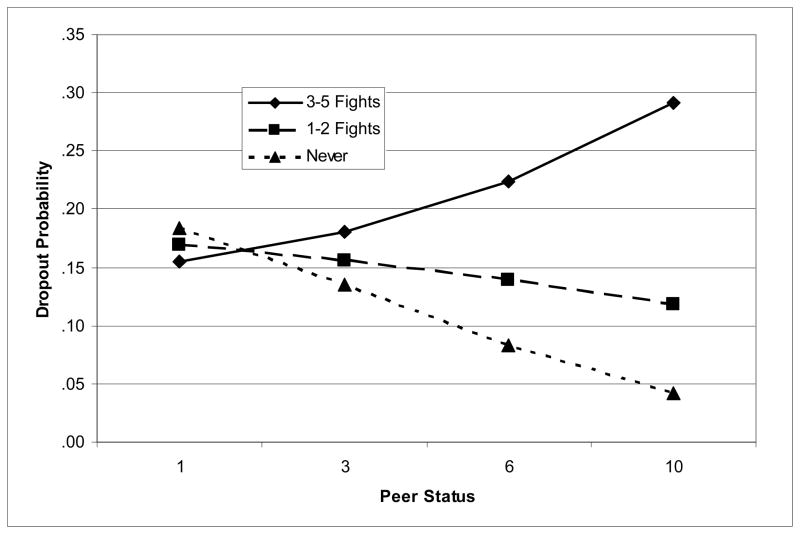

To assess the magnitude of this effect, Figure 1 presents predicted probabilities of high school dropout for low SES males (based on Model 3a). The values of friends fighting and peer status were allowed to vary while the other covariates are set to their mean values. As shown in Figure 1, popular and disadvantaged youth with non-violent friends are especially unlikely to drop out of high school. By contrast, peer acceptance within a violent group (where friends fight an average of 3–4 times in the past year) dramatically increases the likelihood of high school dropout.7 Popular and disadvantaged male students embedded in highly violent peer groups have a 30% probability of dropping out of high school, which is more than twice the national average.8

Figure 1.

Predicted Probability of High School Dropout among Low SES Males by Peer Status and Friends’ Violence

PEER STATUS, VIOLENCE, AND EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT

To test the robustness of our results, we next examine two additional outcomes measured in 2001: years of schooling and whether the respondents completed a four-year college degree. Again, we restricted these analyses to older respondents in our sample (i.e., respondents who were in the 11th or 12th grade during the first wave of data collection). Table 4 presents ordinary least squares regression estimates for models predicting years of schooling and logistic regression parameters for models predicting college graduation. As shown in Table 4, peer acceptance within a group of violent friends diminishes years of schooling and reduces the chances of college completion only among low SES males. For boys from high SES background, the interaction effect is statistically non-significant. These findings provide further evidence that low SES boys who derive status from violent subgroups jeopardize their educational futures and this effect persists into young adulthood.

Table 4.

OLS and Logistic Regression Estimates Predicting Educational Attainment Among Males with Friends (11th and 12th Grade Cohort Only)

| Predictor Variables | Outcome 1: Years of Education

|

Outcome 2: College Graduation

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a Low Parent Education | Model 1b High Parent Education | Model 2a Low Parent Education | Model 2b High Parent Education | |||||||

| b | (SE) | b | (SE) | b | (SE) | exp(b) | b | (SE) | exp(b) | |

| Peer Network Characteristics | ||||||||||

| Peer Status | .135 * | (.059) | .078 | (.039) | .237* | (.113) | 1.27 | .176** | (.060) | 1.19 |

| Friends’ GPA | .099 | (.192) | .342 | (.197) | .323 | (.578) | 1.38 | .281 | (.291) | 1.32 |

| Friends’ Fighting | .256 | (.254) | −.136 | (.205) | 1.089* | (.522) | 2.97 | −.013 | (.477) | .99 |

| Friends’ Class Expectations | .058 | (.062) | .176 * | (.079) | .233 | (.201) | 1.26 | .321* | (.113) | 1.38 |

| Peer Status * Friends’ Fighting | −.133 * | (.065) | −.029 | (.042) | −.290* | (.135) | .75 | −.097 | (.087) | .91 |

| Sociodemographic Variables | ||||||||||

| Grade Level | −.125 | (.190) | .230 | (.161) | −.164 | (.327) | .85 | .294 | (.247) | 1.34 |

| Hispanic | .353 | (.268) | .116 | (.308) | −.451 | (.482) | .64 | .077 | (.382) | 1.08 |

| Black | .108 | (.296) | −.222 | (.274) | .549 | (.596) | 1.73 | .083 | (.347) | 1.09 |

| Asian | 1.151 | (.661) | .483 | (.339) | 1.919* | (.767) | 6.82 | −.132 | (.609) | .88 |

| Intact Family | −.267 | (.195) | .277 | (.213) | .044 | (.403) | 1.04 | .238 | (.369) | 1.27 |

| Individual Characteristics | ||||||||||

| Fighting | −.125 | (.086) | −.199 ** | (.073) | −.361 | (.282) | .70 | −.185 | (.120) | .83 |

| Grades | .422 ** | (.130) | .820 *** | (.134) | .585 | (.337) | 1.79 | 1.087*** | (.220) | 2.96 |

| Middle-Class Expectations | .053 | (.062) | .005 | (.042) | .027 | (.122) | 1.03 | −.035 | (.056) | .97 |

| School Effort | .124 | (.185) | .091 | (.118) | .649 | (.472) | 1.91 | .402 | (.212) | 1.50 |

| Althlete | .380 * | (.190) | .401 | (.205) | .786 | (.434) | 2.19 | .703* | (.347) | 2.02 |

| Picture Vocabulary Score | .028 *** | (.006) | .028 *** | (.006) | .033* | (.015) | 1.03 | .042** | (.013) | 1.04 |

| Intercept | 9.105 *** | (2.380) | 3.705 | (2.053) | −10.883* | (4.577) | −16.844*** | (3.978) | ||

| Sample size | 608 | 982 | 608 | 982 | ||||||

Note.

p <.001,

p <.01,

p <.05

DISCUSSION

Although sociologists have theorized about delinquent subcultures for the better part of a century, relatively little quantitative research has addressed some of these authors’ core hypotheses. In this study, results suggest that disadvantaged boys who are popular in violent groups are much more likely than other youth to drop out of high school. We find that peer acceptance generally holds a negative association with school dropout, but that acceptance in violent groups compromises the socioeconomic attainment of disadvantaged boys. Consistent with subculture perspectives, our findings suggest that peer status in “bad” crowds provides an additional force pulling poor young males away from school.

To this point, we have limited our discussion of the conditional effects of race. Several theorists rely on the subculture of violence thesis to explain black male violence, peer status, and subsequent attainment, particularly in urban settings (Anderson 1999). According to Ogbu’s (2003) oppositional culture theory, high achieving black students may have lower peer status among black peers because they are labeled as “acting white.” For young black males, violence then becomes an attractive means of rejecting white society and commanding peer respect, while simultaneously pulling them from conventional pathways (Anderson 1999; McCall 1994; Wolfgang and Ferracuti 1967). In analyses not shown, we tested this hypothesis by restricting our models to low SES youth and examining whether the effect of peer status and friends’ violence on high school dropout varied by race and ethnicity. Similar to other studies (Cao, Adams, and Jensen 1997; Heimer 1997; Markowitz and Felson 1998), we find little support for the black subculture of violence thesis. Among low SES youth, the effect of peer status and friends’ violence on dropout is stronger among black males than white and Hispanic males, but the differences in the effects were not statistically significant (z-statistic between black and Hispanic males = .98; z-statistic between black and white males = 1.22). Thus, low SES black males who gained prestige within violent groups were not significantly more likely than other low SES males to drop out of high school.

Interestingly, our results also suggest that the relationship between individual violence and high school dropout varies by socioeconomic background. We found that self-reported fighting increased the chances of high school dropout only among boys from more advantaged backgrounds. A likely explanation for this lies in the non-normative quality of violence in high SES peer groups. Absent social support for violent behavior (Kreager forthcoming), aggressive high-SES youth are likely to be alienated within school-based peer networks, increasing their risks of school dropout. By contrast, low SES boys are likely to find more opportunities for peer acceptance in violent groups. For poor males, it is the status gained in the violent subculture, and not necessarily their own violence, that places them at greater risk of school dropout. This argument is consistent with ethnographic studies that connect socioeconomic background with low-attaining and violent “rebellious” or “burnout” peer groups (Eckert 1989; Lesko 1988; Coleman 1961; Eder 1985; Brantlinger 1993; Schwartz 1987; Hollingshead 1949).

Although peer status in violent crowds increases the risk of high school dropout for low SES males, we did not find similar conditioning effects for friends’ school performance or aspirations. In an unlisted reduced-form model, we found a significant interactive effect of peer status and friends’ grades on low-SES male dropout, such that poor males with achieving friends are likely to stay in school. However, this effect becomes statistically non-significant when we include the students’ own grades, expectations, and test scores. Our findings therefore suggest that individual, rather than group, characteristics explain why popular students in high achieving groups are unlikely to exit school early. Popular and overachieving males are likely to stay in school regardless of their socioeconomic background or friends’ behaviors. However, for low-SES males in violent groups, popularity increases the risks of dropout independent of their prior attributes or violent behavior.

Because we were interested in testing the subculture of violence hypothesis for male educational attainment, we restricted our analyses to male samples. However, future research of female peer status and attainment may identify important gender differences. As authors such as Anderson (1999) and Steffensmeier and Allan (1996) note, the individual characteristics associated with female peer acceptance may differ substantially by SES. Just as exaggerated forms of masculinity are thought to bring social rewards for some low SES males, exaggerated forms of femininity – such as early childbearing or heightened sexuality – may be alternative sources of prestige for some low SES females. Although it is beyond the scope of this paper, future research using the Add Health dataset could address how peer status and disadvantage relate to female attainment.

Although our findings are strong and robust to alternative model specifications, they are qualified by two data limitations. First, our analyses cannot fully identify the causal ordering of our observed relationships. Cohen (1955) suggested that low SES males first do poorly in school and then turn to violent subcultures as alternative sources of peer status. Lacking childhood information, we are unable to discern whether poor school performance precedes or follows entry into violent groups. Future research examining within-individual changes in school performance, violence, and peer status, beginning in early childhood and extending into late adolescence, may help researchers better understand the causal ordering of school failure and violence.

Second, we cannot completely rule out spuriousness resulting from unobserved population heterogeneity. Popular youth are commonly described as mature, independent, self-confident, cooperative, cautious, and helpful (Coie et al. 1990; Newcomb et al. 1993; Rubin et al. 1998). These “pro-social” traits could explain both greater peer acceptance and the desire to complete high school. Similarly, a propensity toward violence, low cognitive ability, or anti-social personality may explain why low SES boys are able to gain status in violent groups and choose to exit school early. Although we included measures of prior violence, academic ability, school grades, expectations, and athletic participation as predictors of high school dropout, and were encouraged by the robustness of our observed interaction effect, unobserved heterogeneity may still be a threat to our causal inferences. Again, the use of panel data to examine within-individual changes in peer status, aggression, and achievement over time would control for time-stable individual differences and eliminate primary sources of spuriousness.

Although data limitations somewhat reduce our confidence in causal statements, the data also make it likely that our findings are somewhat conservative. We derive our measures of peer status and friendship characteristics solely from the nominations of enrolled and attending students, meaning that dropouts, skippers, and friends outside of school did not contribute values to the network items. It is likely that violent groups would include a disproportionate percentage of these absent students. Moreover, popular youth in violent groups may derive much of their status from older dropouts and skipping students, which in turn could further increase their own chances of school dropout. We thus suspect that information gathered for out-of-school friends would strengthen the conditional effect of violent group contexts on the peer status-dropout relationship.

Along with analyzing out-of-school networks, future research should also examine the effects of adolescent friendship characteristics and status on adult occupational outcomes. Hagan (1991), using a longitudinal sample of Canadian youth, found that lower-class boys who identified with a subculture of delinquency attained lower prestige jobs in adulthood than boys whose subcultural preferences were not centered on violence, vandalism, and theft. By contrast, boys from high SES families who favored a party subculture (e.g., going to parties, driving around in cars, drinking alcohol) were likely to attain high prestige jobs in adulthood. The fourth wave of data collection from the Add Health study will allow researchers to explore these relationships with the same network measures used in this paper. As the Add Health respondents move into adult careers, future research can assess whether peer status (and especially peer status within drinking crowds) affects occupational outcomes (Hagan 1991: p. 579).

In sum, our study finds that disadvantaged boys who gain prestige in violent crowds are at increased risk of early school exit; these delinquent boys become “too cool for school.” As long as socioeconomic status and violence remain correlated, disadvantaged youth will have greater exposure to violence as a status tool than their more advantaged peers. This alternative status hierarchy, in turn, can contribute to enduring inequalities in educational attainment.

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris, and funded by a grant P01-HD31921 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 17 other agencies. We thank Richard Felson, George Farkas, and Nathan Walters for their helpful comments. Special acknowledgment is due to Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Persons interested in obtaining data files from Add Health should contact Add Health, Carolina Population Center, 123 W. Franklin Street, Chapel Hill, NC 27516-2524.

Footnotes

We use the PASSIVE command in the ICE procedure to ensure that interaction terms are excluded from the component variables’ imputation (Royston 2005).

Research shows that GED holders differ from permanent high school dropouts in that they obtain more years of school (Cameron and Heckman 1993). In analyses not shown, our substantive findings remained the same when GED holders were not coded as high school dropouts.

There are other ways to look at the relationship between friendships, violence, and educational attainment. One could examine peer violence in reciprocated nominations, which may better capture “objective” friendships. However, it is likely that violent youth draw prestige and respect from peers that they do not like or respect. Consistent with this point, in supplemental analyses we found that although violent males had similar received friendship nominations as non-violent males, violent males had significantly lower reciprocated friendship nominations than non-violent males (t-test = −6.068; p < .001). One could also measure the peer violence of a student’s “sent” friendship network, or network of desired friendships. It could be that youth who desire to be part of a “bad” crowd, but are not necessarily accepted by that group, are more likely than other youth to drop out of high school. However, this idea is inconsistent with subculture perspectives, as peer acceptance within violent groups is the key mechanism pulling youth away from school.

It is noteworthy that our results did not substantively change when we used the parent’s report of his or her highest level of schooling to measure socioeconomic background (results not shown).

Age could accomplish a similar goal, but may miss students who are older or younger than other students of similar grade level. Collinearity makes it inappropriate to simultaneously include age and grade level in our models. However, replacing grade level with age did not alter our pattern of results.

We also estimated Model 3 separately for each level of parent’s education. We found that the interaction effect (i.e., peer status * friends’ violence) was fairly monotonic with respect to parents’ education, but differences were greatest between males from less than college-educated parents and males from parents with at least some college education. The estimated interaction coefficient of peer status * friends’ violence for each value of parent(s) highest education were as follows: Less than High School Degree (b = .197); High School Graduate (b = .112); Some College (b = −.014); College Graduate or Higher (b = −.054).

Willis (1977) contends that working-class class boys often try to establish themselves in paid work as they pull themselves away from school. Research shows that early work experiences, especially those considered intensive in nature, increase the likelihood of high school dropout (Lee and Staff 2007). In supplemental analyses we did not find that intensive work (coded as more than 20 hours per week) predicted high school dropout among males from low SES backgrounds, nor did it mediate the interaction effect of peer status * friends’ violence.

In analyses not shown we estimated an interaction between peer status, friends’ fighting, and respondents’ level of fighting. This four-way interaction effect was statistically non-significant. However, youth who are the most violent in delinquent groups are not the most popular. Youth who are unpredictable and engage in indiscriminate violence (i.e., the “hard-knocks”) are often marginalized within violent groups of boys (Messerschmidt 1993; Willis 1977; Sanchez-Jankowski 1991).

References

- Alexander Karl L, Entwisle Doris R, Horsey Carrie S. From First Grade Forward: Early Foundations of High School Dropout. Sociology of Education. 1997;70:87–107. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson Elijah. Code of the Street: Decency, Violence, and the Moral Life of the Inner City. New York: W. W. Norton and Company; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Astone Nan M, McLanahan Sara S. Family Structure, Parental Practices, and High School Completion. American Sociological Review. 1991;56:309–320. [Google Scholar]

- Astone Nan M, McLanahan Sara S. Family Structure, Residential Mobility, and School Dropout: A Research Note. Demography. 1994;31:575–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantlinger Ellen A. The Politics of Social Class in Secondary School: Views of Affluent and Impoverished Youth. New York: Teachers College Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Brown B Bradford. Adolescents’ Relationships with Peers. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. Hoboken, N.J: John Wiley and Sons; 2004. pp. 363–394. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu Pierre, Passeron Jean-Claude. Reproduction in Education, Society, and Culture. London: Sage; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles Samuel, Gintis Herbert. Schooling in Capitalist America. New York: Basic Books; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns Robert B, Cairns Beverly D, Neckerman Holly J. Early School Dropout: Configurations and Determinants. Child Development. 1989;60:1437–1452. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1989.tb04015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron Stephen V, Heckman James J. The Nonequivalence of High School Equivalents. Journal of Labor Economics. 1993;11:1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Cao Liqun, Adams Anthony, Jensen Vickie J. A Test of the Black Subculture of Violence Thesis: A Research Note. Criminology. 1997;35:367–379. [Google Scholar]

- Chantala Kim, Tabor Joyce. Strategies to Perform a Design-Based Analysis using the Add Health Data. 1999 URL: http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/files/weight1.pdf.

- Cloward Richard A, Ohlin Lloyd E. Delinquency and Opportunity: A Theory of Delinquent Gangs. Glencoe, IL: The Free Press; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Coie John D, Dodge Kenneth A, Kupersmidt JB. Peer Group Behavior and Social Status. In: Asher SR, Coie JD, editors. Peer Rejection in Childhood. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 17–59. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Albert K. Delinquent Boys: The Culture of the Gang. New York: The Free Press; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman James S. The Adolescent Society: The Social Life of the Teenager and Its Impact on Education. New York: Free Press; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Davies Scott. Subcultural Explanations and Interpretations of School Deviance. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1999;4:191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn L Michelle, Dunn Lloyd M. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test - Revised Edition. Circle Hills, MN: American Guidance Services; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert Donna J. Jocks and Burnouts: Social Categories and Identity in the High School. New York, NY: Teachers College Press, Columbia; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Eder Donna. The Cycle of Popularity: Interpersonal Relations among Female Adolescents. Sociology of Education. 1985;58:154–165. [Google Scholar]

- Ensminger Margaret E, Slusarcick Anita L. Paths to High School Graduation or Dropout: A Longitudinal Study of a First-Grade Cohort. Sociology of Education. 1992;65:95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Estell David B, Farmer Thomas W, Pearl Ruth, Van Acker Richard, Rodkin Philip C. Heterogeneity in the Relationship between Popularity and Aggression: Individual, Group, and Classroom Influences. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2003;101: 75–85. doi: 10.1002/cd.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer Thomas W, Estell David B, Leung Man-Chi, Trott Hollister, Bishop Jennifer, Cairns Beverly D. Individual Characteristics, Early Adolescent Peer Affiliations, and School Dropout: An Examination of Aggressive and Popular Group Types. Journal of School Psychology. 2003;41:217–232. [Google Scholar]

- Finn Jeremy D. Withdrawing from School. Review of Educational Research. 1989;59:117–142. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan John. Destiny and Drift: Subcultural Preferences, Status Attainment, and the Risks and Rewards of Youth. American Sociological Review. 1991;56:567–582. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan John. The Social Embeddedness of Crime and Unemployment. Criminology. 1993;31:465–490. [Google Scholar]

- Hanushek Eric A, Kain John F, Markman Jacob M, Rivkin Steven G. Does Peer Ability Affect Student Achievement? Journal of Applied Economics. 2003;18:527–544. [Google Scholar]

- Heimer Karen. Socioeconomic Status, Subcultural Definitions, and Violent Delinquency. Social Forces. 1997;75:799–833. [Google Scholar]

- Holland Alyce, Andre Thomas. Athletic Participation and the Social Status of Adolescent Males and Females. Youth and Society. 1994;25:388–407. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead August B. Elmtown’s Youth: The Impact of Social Classes on Adolescents. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Kinney David A. From Nerds to Normals: The Recovery of Identity among Adolescents from Middle School to High School. Sociology of Education. 1993;66:21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kreager Derek A. Peer Acceptance and Adolescent Delinquency. Criminology Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Jennifer C, Staff Jeremy. When Work Matters: The Varying Impact of Adolescent Work Intensity on High School Drop-out. Sociology of Education. 2007;80:158–178. [Google Scholar]

- Lesko Nancy. Symbolizing Society: Stories, Rites, and Structure in Catholic High School. Philadelphia: Falmer; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Luther Suniya S, McMahon Thomas J. Peer Reputation Among Inner-City Adolescents: Structure and Correlates. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1996;6:581–603. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod Jay. Ain’t No Makin It: Leveled Aspirations in a Low-Income Neighborhood. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz Fred E, Felson Richard B. Social Demographic Differences in Attitudes and Violence. Criminology. 1998;36:117–138. [Google Scholar]

- McNeal Ralph B., Jr Extracurricular Activities and High School Dropouts. Sociology of Education. 1995;68:62–80. [Google Scholar]

- McNeal Ralph B., Jr Parental Involvement as Social Capital: Differential Effectiveness on Science Achievement, Truancy, and Dropping Out. Social Forces. 1999;78:117–144. [Google Scholar]

- Messerschmidt James W. Masculinities and Crime. Lanham, MA: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Walter B. Lower Class Culture as a Generating Milieu of Gang Delinquency. Journal of Social Issues. 1958;14:5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt Terrie E. Adolescence-Limited and Life-Course-Persistent Antisocial Behavior: A Developmental Taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt Terrie E, Caspi Avshalom, Harrington Honalee, Milne Barry J. Males on the Life-Course-Persistent and Adolescence-Limited Antisocial Pathways: Follow-Up at Age 26 Years. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:179–207. doi: 10.1017/s0954579402001104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb Andrew F, Bukowski William M, Pattee Linda. Children’s Peer Relations: A Meta-Analytic Review of Popular, Rejected, Neglected, Controversial, and Average Sociometric Status. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:99–128. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbu John U. Black American Students in an Affluent Suburb: A Study of Academic Disengagement. Mahweh, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Parker Jeffrey G, Asher Steven R. Peer relations and Later Personal Adjustment: Are Low-Accepted Children at Risk? Psychological Bulletin. 1987;102:357–89. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.102.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodkin Philip C, Farmer Thomas W, Pearl Ruth, Van Acker Richard. Heterogeniety of Popular Boys: Antisocial and Prosocial Configurations. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:14–24. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.36.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royston Patrick. Multiple Imputation of Missing Values: Update. The Stata Journal. 2005;5:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin Donald. Multiple Imputation After 18+ Years. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1996;91:473–489. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin Kenneth H, Bulkowski William M, Parker Jeffrey G. Peer Interactions, Relationships, and Groups. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology, Volume 3, Social, Emotional and Personality Development. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 217–252. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Jankowski Martin. Islands in the Street: Ganges and American Urban Society. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider Barbara, Stevenson David. The Ambitious Generation: America’s Teenagers, Motivated but Directionless. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz G. Beyond Conformity or Rebellion: Youth and Authority in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw Clifford T. The Natural History of a Delinquent. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1931. [Google Scholar]

- South Scott J, Haynie Dana L, Bose Sunita. Student Mobility and School Dropout. Social Science Research. 2007;36:68–94. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 8.0. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Steffensmeier Darrell, Allan Emilie. Gender and Crime: Toward a Gendered Theory of Female Offending. Annual Review of Sociology. 1996;22:459–488. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart Eric A, Schreck Christopher J, Simons Ronald L. I Ain’t Gonna Let No One Disrespect Me” Does the Code of the Street Reduce or Increase Violent Victimization among African American Adolescents? Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2006;43:427–458. [Google Scholar]

- Thrasher Frederic M. The Gang: A Study of 1,313 Gangs in Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1927. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. Digest of Education Statistics, 2005. National Center for Education Statistics; Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman Stanley, Faust Katherine. Social Network Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel Kathryn R, Asher Steven R. The Academic Lives of Neglected, Rejected, Popular, and Controversial Children. Child Development. 1995;66:754–763. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel Kathryn R, Caldwell Kathryn. Friendships, Peer Acceptance, and Group Membership: Relations to Academic Achievement in Middle School. Child Development. 1997;68: 1198–1209. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis Paul. Learning to Labor: How Working Class Kids Get Working Class Jobs. New York: Columbia University Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfgang Marvin E, Ferracuti Franco. The Subculture of Violence: Towards an Integrated Theory in Criminology. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Xie Hongling, Farmer Thomas W, Cairns Beverly D. Different Forms of Aggression Among Inner-City African American Children: Gender, Configurations, and School Social Networks. Journal of School Psychology. 2003;41:355–375. [Google Scholar]

- Xie Hongling, Cairns Robert B, Cairns Beverly D. Social Networks and Configurations in Inner-City Schools: Aggression, Popularity, and Implications for Students with EBD. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 1999;7:147–155. [Google Scholar]