Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the prevalence and risk of antenatal and postpartum mental disorders among obese and overweight women.

Data sources

Seven databases (including MEDLINE and ClinicalTrials.gov) were searched from inception to January 7, 2013, in addition to citation tracking, hand-searches and expert recommendations.

Methods of study selection

Studies were eligible if antenatal or postpartum mental disorders were assessed with diagnostic or screening tools among women who were obese or overweight at the start of pregnancy. Of the 4,687 screened articles, 62 met the inclusion criteria for the review. The selected studies included a total of 540,373 women.

Tabulation, integration, and results

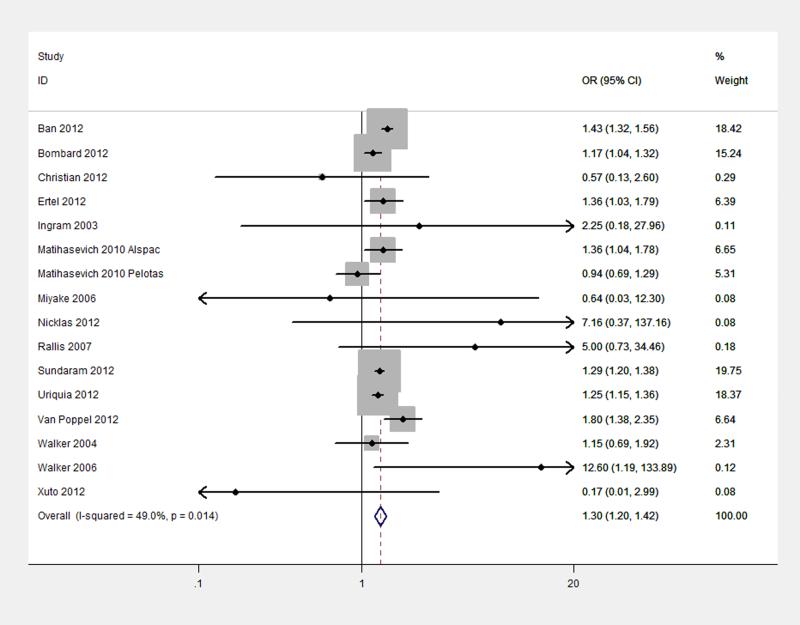

Unadjusted odds ratios were pooled using random-effects meta-analysis for antenatal depression (n=29), postpartum depression (n=16) and antenatal anxiety (n=10). Obese and overweight women had significantly higher odds of elevated depression symptoms than normal-weight women and higher median prevalence estimates. This was found both during pregnancy (obese OR 1.43, 95%CI 1.27-1.61, overweight OR 1.19, 95%CI 1.09-1.31; median prevalence: obese 33.0%, overweight 28.6%, normal-weight 22.6%) and postpartum (obese OR 1.30, 95%CI 1.20-1.42, overweight OR 1.09, 95%CI 1.05-1.13; median prevalence: obese 13.0%, overweight 11.8%, normal-weight 9.9%). Obese women also had higher odds of antenatal anxiety (OR 1.41, 95%CI 1.10-1.80). The few studies identified for postpartum anxiety (n=3), eating disorders (n=2) or serious mental illness (n=2) also suggested increased risk among obese women.

Conclusion

Healthcare providers should be aware that women who are obese when they become pregnant are more likely to experience elevated antenatal and postpartum depression symptoms than normal-weight women, with intermediate risks for overweight women.

Introduction

The proportion of women who are overweight (body mass index(BMI) 25-30 kg/m2) or obese (BMI>30 kg/m2) when they become pregnant is substantial and rapidly increasing; a recent study estimated that over 20% of US women are obese at the start of pregnancy.(1) High pre-pregnancy BMI, particularly obesity, increases the risk of numerous adverse maternal and fetal outcomes including preeclampsia, gestational diabetes and fetal death.(2) The impact of obesity on physical health during pregnancy has been studied extensively, while the relationship between obesity and maternal mental health has been largely neglected. Mental disorders are among the most common complications of pregnancy. The 12-month prevalence of any psychiatric illness among US women who have been pregnant in the past year has been estimated at 25.3%, ranging from 0.4% for psychotic disorders to roughly 13% for mood disorders.(3)

In non-pregnant adults, obesity is associated with mental disorders including depression,(4) binge eating disorder,(5) and bipolar disorder.(6) In a recent meta-analysis of longitudinal studies, obese women had 67% higher odds of developing depression at follow-up than normal-weight women (unadjusted odds ratio 1.67; 95% confidence interval 1.11-2.51).(4) The extent to which the relationship exists during pregnancy and postpartum is not clear; research in this area is limited and findings have been inconsistent with no meta-analyses to date.(7-9) This study aimed to address the evidence gap by conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate the prevalence and risk of antenatal and postpartum mental disorders in women who were known to be overweight or obese at the start of pregnancy, compared with normal-weight controls.

Methods

The review followed MOOSE guidelines and the protocol was registered with the prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO; registration number CRD42013003093).

Sources

Five bibliographic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL and MIDRIS Maternal) were searched from inception to January 7th 2013 using OvidSP. The Cochrane Library and ClinicalTrials.gov were searched with the same date limits. Searches were conducted in English, using a combination of exploded Medical Subject Headings and text terms related to obesity, mental disorders, pregnancy and postpartum (see Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx). We also conducted forward and backward citation tracking, hand-searched key journals (Obstetrics and Gynecology; BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology; International Journal of Obesity, all from 1998 onwards) and obtained expert recommendations for additional relevant studies.

Study selection

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they assessed antenatal (at any point in pregnancy) or postpartum (within a year after delivery) mental disorders in women who were overweight or obese at the start of pregnancy. Studies were not eligible for the review if we were unable to extract or obtain data for overweight or obese women separately from normal-weight women. Data from studies with overweight or obese women only were used in the prevalence estimates but not for the evaluation of risk, which required normal-weight controls. Both diagnostic and screening measures for mental disorders were accepted, as were data extracted from routine records. Measures of stress, state anxiety or combined mental disorders were not eligible, nor were disorder classifications based entirely on medication status. Categorization of ‘pre-pregnancy’ overweight or obesity (based on measured or self-reported BMI) was accepted from within a year pre-pregnancy or during the first trimester, to prevent confounding by gestational weight gain. Only published, peer-reviewed English language papers were eligible. Data were accepted from cohort, case-control, cross-sectional and intervention studies (baseline data only).

All identified citations were downloaded to EndNote© software and titles and abstracts screened for relevance by one reviewer (EM). The full text versions of potentially relevant articles were obtained and assessed for eligibility. A second reviewer (CT) independently assessed the eligibility of 100 randomly selected citations and eligibility decisions were compared. Authors were contacted to determine whether identified conference papers or abstracts had been published in peer reviewed journals and raw data was requested if published studies did not presented information in the required format. Where duplicate publications were identified, the data based on the largest sample size was included. One reviewer (EM) extracted data on study characteristics and results using a piloted form. Two reviewers (EM and SA-W) independently assessed the quality of included studies (low, moderate or high) using a tool adapted from previous measures (see Appendix 2,available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx).(10,11) Discrepancies were resolved through discussion with the senior author (LH). Studies were assessed for risk of selection and measurement bias and those with high risk of bias in either area were defined as low quality and excluded from the meta-analysis. This included studies that used non-validated screening measures, studies which excluded women with a current or previous diagnosis of the mental disorder in question and case-control studies which selected participants on a characteristic likely to bias findings (e.g. preeclampsia, fetal mortality). Studies were defined as high quality if they had population-based samples and used either diagnostic measures of mental disorders or well-validated and widely used screening measures (such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale).

Studies were grouped by mental disorder and time period (antenatal or postpartum). Heterogeneity between studies was explored using the I2 statistic and pooled estimates were not calculated in cases of high heterogeneity (I2>90%). In all cases, heterogeneity was too large to pool prevalence data, therefore data from high quality studies were used to calculate median prevalence estimates (with interquartile range, IQR). Heterogeneity of odds ratios (OR) was low to moderate so pooled estimates with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were calculated for each disorder and time period using DerSimonian-Laird random-effects meta-analysis if sufficient studies were available.(12) Odds ratios for obese and overweight women were pooled separately, with normal-weight women as the reference group, and forest plots constructed. Studies which only provided combined data for overweight and obese women were excluded from the meta-analyses. Where significantly increased odds were found for both overweight and obese women separately, pooled estimates were calculated for the odds of the disorder in obese women using overweight women as the reference group, to investigate whether there was a dose-response relationship.

We performed sensitivity analyses (for example, including only high quality studies, studies using diagnostic measures or studies providing adjusted odds ratios) and influence analyses (removing each study in turn from the pooled estimates). Unless otherwise stated, these did not substantially alter findings. Publication bias was assessed through visual inspection of funnel plots and Peter’s test.(13) All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 12 (Stata Corp, Texas).

Results

A flow diagram of the study selection process is given in Figure 1. Overall 4,687 unique references were screened and the full texts of 571 potentially eligible studies were obtained. Of these, 509 were excluded (reasons for full text exclusions are given in Figure 1). In total 62 studies with 540,373 women were included in the review: 75,108 obese women, 126,990 overweight women and 337,533 normal-weight women (with 742 women in combined overweight and obese categories). The majority of studies were conducted in high-income countries with only nine from low- or middle-income countries (including a total of 614 obese women).(14-22) Five of these studies also focused on low income women within these countries (15-17,19,21). Of the studies in high-income countries, eight focused on low-income (23-27) or ethnic-minority women.(28-30) Timing of mental disorder assessment ranged between 10 and 36 weeks gestation and 1 week to 1 year postpartum.

Figure 1.

Study selection flow diagram.

An overview of included studies is given in Table 1; several studies provided data for more than one mental disorder or time period. All individual study characteristics and results are given in the included studies table (see Appendix 3 online at http://links.lww.com/xxx). The systematic review identified 39 studies examining antenatal depression,(7-9,14-18,23,24,28-56) of which 29 were eligible for the meta-analysis.(7,8,14-16,24,28,29,33-53) The majority of these studies identified women with elevated depression symptoms using the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (n=15; 13 with a cut-off ≥16, one with a cut-off ≥17 and one used the short-form CESD with a cut-off of ≥11) or the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (n=5; four used the cut-off ≥13, one used a Chinese translation with a validated cut-off ≥10). The median prevalence of elevated depression symptoms was highest in obese women (33.0%) and lowest in normal-weight women (22.6%) based on the seven high-quality studies.(16,48-53) Median prevalence and interquartile range estimates are given in Table 2. As shown in Table 3, obese women had significantly higher odds of antenatal depression than normal-weight controls (see Figure 2), as did overweight women. Obese women also had significantly elevated odds of depression when compared with overweight women as the reference group, providing evidence of a dose-response relationship. There was no evidence of publication bias for studies on antenatal depression or for any of the other meta-analyses conducted. In sensitivity analyses, pooled effect sizes increased when only high quality studies were included for both obese (OR 1.59, 95%CI 1.32-1.91) and overweight women (OR 1.41, 95%CI 1.28-1.54) compared with normal weight controls. Removing studies with obesity-related health exclusion criteria (e.g. history of diabetes) from the meta-analysis also increased effect sizes for obese women (OR: 1.56, 95%CI 1.44-1.69). There were insufficient studies using diagnostic measures or presenting adjusted odds ratios to pool this data; however both studies using diagnostic measures of depression (16,57) found higher odds among obese women, and the single study providing adjusted odds ratios showed that the association between obesity and depression remained significant after adjusting for maternal ethnicity.(37)

Table 1. Summary of Included Study Characteristics.

| All included studies |

Antenatal depression |

Postpartum depression |

Antenatal anxiety |

Postpartum anxiety |

Antenatal eating disorders |

Antenatal serious mental illness |

Postpartum serious mental illness |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of studies * | 62 | 39 | 23 | 16 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Region | ||||||||

| North America | 35 | 22 | 11 | 6 | - | - | - | - |

| Europe | 14 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Australasia | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - |

| South America | 6 | 3 | 2 | 3 | - | - | - | - |

| Asia | 5 | 3 | 2 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Study design | ||||||||

| Prospective cohort study | 38 | 24 | 16 | 9 | 2 | 1 | - | - |

| Retrospective cohort study | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | - | 2 | 1 |

| Cross sectional study | 12 | 5 | 5 | 2 | - | 1 | - | - |

| Case control study | 4 | 4 | - | 2 | - | - | - | - |

| Trial (baseline) | 5 | 5 | - | 2 | - | - | - | - |

| Sample size | ||||||||

| <50 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | - | - | - | - |

| 50-500 | 28 | 18 | 10 | 5 | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| >500 | 29 | 17 | 11 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| BMI | ||||||||

| Measured in first trimester | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Extracted from records | 9 | 7 | 2 | 4 | 1 | - | 2 | 1 |

| Pre-pregnancy weight reported in pregnancy | 37 | 28 | 9 | 11 | 2 | 2 | - | - |

| Pre-pregnancy weight reported postpartum | 11 | 1 | 10 | - | - | - | - | - |

| BMI categories | ||||||||

| Institute of Medicine (2009) † | 50 | 32 | 20 | 11 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Institute of Medicine (1990) ‡ | 8 | 4 | 3 | 3 | - | - | - | - |

| Other | 4 | 3 | - | 2 | - | - | - | - |

| Mental disorder assessment | ||||||||

| Diagnostic measure | 2 | 2 | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Extracted from records | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | - | 2 | 1 |

| Screening measure | 56 | 34 | 22 | 13 | 2 | 2 | - | - |

Many studies included data for more than one disorder or time period

Institute of Medicine 2009 categories: normal weight 18.5-25kg/m2; overweight 25-30kg/m2; obese >30kg/m2

Institute of Medicine 1990 categories: normal weight 19.8-26kg/m2; overweight 26-29kg/m2; obese>29kg/m2

Table 2. Median Prevalence and Interquartile Range for Antenatal and Postpartum Depression.

| Median Prevalence (%) | Interquartile Range (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Antenatal depression | ||

| Obese | 33.0 | 11.2-42.0 |

| Overweight | 28.6 | 12.4-36.6 |

| Normal weight | 22.6 | 9.5-27.9 |

| Postpartum depression | ||

| Obese | 13.0 | 12.2-14.1 |

| Overweight | 11.8 | 9.6-13.5 |

| Normal weight | 9.9 | 9.3-14.0 |

Table 3. Unadjusted pooled odds ratios.

| Reference Group | Pooled Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Intervals | P | Heterogeneity I2 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antenatal depression | |||||

| Obese | Normal weight | 1.43 | 1.27-1.61 | <0.001 | 44.4 |

| Overweight | Normal weight | 1.19 | 1.09-1.31 | <0.001 | 32.1 |

| Obese | Overweight | 1.21 | 1.06-1.37 | <0.001 | 33.6 |

| Postpartum depression | |||||

| Obese | Normal weight | 1.30 | 1.20-1.42 | <0.001 | 49.0 |

| Overweight | Normal weight | 1.09 | 1.05-1.13 | <0.001 | 0.0 |

| Obese | Overweight | 1.20 | 1.13-1.27 | <0.001 | 9.7 |

| Antenatal anxiety | |||||

| Obese | Normal weight | 1.41 | 1.10-1.80 | 0.006 | 60.7 |

| Overweight | Normal weight | 1.10 | 0.98-1.23 | 0.094 | 0.0 |

Figure 2.

Pooled odds of antenatal depression in obese women compared with normal weight controls. OR: odds ratio, CI: confidence interval.

The systematic review identified 23 studies that assessed postpartum depression (19,20,22,25-27,36,38,42,50,51,55,58-67) of which 16 were included in the meta-analysis.(20,22,26,27,36,38,42,50,51,58-63) Again, the majority of these studies used the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (n=5; all with a cut-off ≥16) or the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (n=6; four with a cut-off ≥13, one with a cut-off ≥10 and one Japanese translation with a validated cut-off ≥9). Based on five high quality studies,(22,50,51,63) the median prevalence of elevated postpartum depression symptoms ranged from 13.0% for obese women to 9.9% for normal-weight women (see Table 2).

As shown in Table 3, significantly higher odds of postpartum depression were found for both obese (see Figure 3) and overweight women compared with normal-weight controls. Obese women also had significantly increased odds of postpartum depression when compared with overweight controls, again giving evidence of a dose-response relationship. Heterogeneity and confidence intervals for overweight women increased in size when only the five high-quality studies were included in sensitivity analyses (OR: 1.08, 95%CI: 0.97-1.21). No studies used diagnostic measures for postpartum depression. One study eligible for the meta-analysis presented adjusted data and found no significant association between obesity and depression after extensive adjustment for confounding (including age, ethnicity, education, maternal morbidities, smoking and alcohol use, birth-weight and breastfeeding practice).(62) The review identified 16 studies that assessed antenatal anxiety, (9,16,18,21,31,32,38,39,42,47,48,52,54,68-70) including 10 that were eligible for the meta-analysis.(16,38,39,42,47,48,52,68-70) The majority of these studies (n=7) used the trait subscale or complete scale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (cut-offs between ≥40 and ≥45; one paper used the 10-item version of the trait subscale with the cut-off >20 (75th percentile)). In the one high quality study identified, conducted with low-income women in Brazil, the prevalence of anxiety disorders was 35.0% in obese women, 35.7% in overweight women and 31.0% in normal-weight women.(16) There were significantly higher odds of elevated anxiety among obese than normal-weight women (see Figure 4) but the effect was not significant comparing overweight and normal-weight women (data shown in Table 3). In sensitivity analyses, the odds ratio for overweight women increased following the exclusion of studies with obesity-related health exclusion criteria (OR: 1.13, 95%CI 1.00-1.27). One study used a diagnostic measure of anxiety and found that obese and overweight women both had higher odds of antenatal anxiety than normal-weight women, although neither effect was significant.(16) No studies presented adjusted odds ratios.

Figure 3.

Pooled odds of postpartum depression in obese women compared with normal weight controls. OR: odds ratio, CI: confidence interval.

Figure 4.

Pooled odds of antenatal anxiety in obese women compared with normal weight controls. OR: odds ratio, CI: confidence interval.

Three studies examining postpartum anxiety were identified.(38,42,47) Median prevalence estimates were not calculated as there were no high quality studies. In the individual studies, elevated anxiety symptom prevalence estimates for obese women varied from 4.7% (4.0% for overweight women and 4.2% for normal-weight women; using UK primary care records)(42) to 33.3% (13.3% for overweight women and 16.4% in normal-weight women; based on the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory).(38) There were insufficient data to perform a meta-analysis however individual study findings showed higher odds of postpartum anxiety in obese women than normal-weight controls (although this was only significant in one study). There was no evidence of elevated odds for overweight women.

Antenatal binge eating disorder was examined in two European studies using screening measures.(71,72) Both studies found the highest prevalence among obese women (3.8%;(71) 6.5%)(72) and the lowest in normal-weight women (1.0%;(71) 4.2%),(72) although the increased risk for obese women was significant in one study only.(72) Both studies also estimated the prevalence of antenatal bulimia nervosa; one found no cases among normal weight, overweight or obese women,(71) and the other found a prevalence of 0.29% in obese women, 0.17% in overweight women and 0.26% in normal-weight women.(72) No studies examining postpartum eating disorders were identified.

Two studies were identified examining serious mental illness.(42,73) One high quality study that used linked Swedish health registers estimated the lifetime prevalence of bipolar disorder among pregnant women as 0.42% for obese women, 0.30% for overweight women and 0.21% for normal-weight women, with the odds of bipolar disorder significantly higher for both obese and overweight women compared with normal weight controls.(73) The other study,(42) which used UK primary care records, estimated the period prevalence of serious mental illness (bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders) during pregnancy as 0.21%, 0.09% and 0.13% for obese, overweight and normal-weight women respectively. The estimated prevalence in the first 9 months postpartum was 0.23% for both obese and overweight woman and 0.19% among normal-weight women. No effects were significant.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis found that women who are obese when they become pregnant have significantly higher odds of elevated depression symptoms than normal-weight women in both the antenatal and postpartum periods (43% and 30% increased odds respectively), with intermediate risks for overweight women. Obese women also had higher odds of elevated anxiety during pregnancy than normal-weight women. There was some evidence of an increased risk of other mental disorders among obese women including postpartum anxiety, binge eating disorder and bipolar disorder; however there were insufficient studies to draw conclusions about these diagnoses.

This review provides a comprehensive summary of previous literature on the association between pre-pregnancy obesity and mental disorders during pregnancy and postpartum. Extensive contact with study authors to obtain raw data enabled the inclusion of studies that had not previously used their data to assess the relationship between pre-pregnancy obesity and mental disorders. Low quality studies were excluded from the meta-analysis and findings were robust to sensitivity and influence analyses, increasing our confidence in the conclusions. Dose-response relationships were found between BMI category and both antenatal and postpartum depression, which also supports the hypothesized relationship between increased BMI and risk of depression.

The review had a number of limitations, including the widespread use of self-reported height and weight in the included studies which may lead to BMI misclassification. However, studies have shown that the vast majority of women are assigned to the correct pre-pregnancy BMI category based on self-reported weight,(74) and that symptoms of depression or binge eating disorder do not affect the accuracy of self-reported BMI.(75) Very few studies used diagnostic measures of mental disorders so our findings refer to individuals with elevated symptoms not diagnostic cases; nevertheless the conclusions are important as elevated but sub-clinical symptoms are associated with adverse outcomes during pregnancy and postpartum. Only studies using validated scales were included in the meta-analyses but further validations for specific populations (such as women in early pregnancy) are needed. Studies used a number of different screening measures and cut-offs which will have contributed to the heterogeneity in prevalence estimates, however this allowed a large number of studies to be included which is a strength of this review. Only published studies were eligible which ensures the quality associated with peer-review but can lead to bias; however, funnel plots for the included studies showed no evidence of publication bias. Finally, few studies were carried out in low- and middle income countries which reduces generalizability, as does the inclusion of only English language papers due to limited resources.

Our results are in-keeping with a substantial body of research showing increased risk of mental disorders among non-pregnant obese women.(4-6) Some researchers have suggested that high BMI and depression may not be associated during pregnancy because excess weight is viewed less negatively at this time,(7) but this hypothesis is not supported by our findings. Weight stigmatization can be present throughout the childbearing period and other factors such as physical ill health and poor diet may contribute to the effect of obesity on mental disorders.(4) Pregnancy-related factors (such as gestational diabetes or backache) could also play a role in the association. In addition, the reverse causal pathway may be important as women with a history of depression could have gained weight prior to pregnancy. A number of factors have been suggested to explain the increased risk of weight gain among women with mental disorders, for example the obesogenic effects of several antipsychotics and antidepressant medications.(76) Confounding factors such as low socioeconomic status, which are associated with both pre-pregnancy obesity and mental illness, may also account at least in part for the associations observed. A limitation of our review is that only non-adjusted pooled summary statistics could be calculated as very few studies presented adjusted estimates. One included study found no association between obesity and postpartum depression after extensive adjustment for confounders, but further investigation of this is needed.

Although our review cannot provide causal inferences, the identification of the increased prevalence and risk of antenatal and postpartum mental disorders among obese (and overweight) women has important implications for clinical care and future research. Both obesity and mental illness during pregnancy are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, and their co-morbid impact may lead to a particularly high risk group. Recent research has found that women with antenatal depression have higher risks of gestational diabetes and preeclampsia than women without depression,(17,77) but these findings need to be replicated in subgroups of obese women. In addition, behavioral change interventions for obese pregnant or postpartum women (e.g. improving diet, increasing physical activity) may need to be tailored for women with poor mental health.(78) Based on our findings in this review, around one third of obese pregnant women have elevated symptoms of depression and the impact of this on health behaviors and behavior change needs to be evaluated in future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This review was carried out as part of a PhD studentship funded by the Medical Research Council and Tommy’s Charity. This report is independent research supported through salary support to Louise Howard by the National Institute for Health Research NIHR Research Professorship NIHR-RP-R3-12-011 and the NIHR Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health.

The authors thank the authors of included articles who provided additional data and Clare Taylor for her assistance in study screening.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Presented at the UK and Ireland Marcé Society meeting (London, September 19, 2013).

References

- 1.Fisher S, Kim S, Sharma A, Rochat R, Morrow B. Is Obesity Still Increasing among Pregnant Women? Prepregnancy Obesity Trends in 20 States, 2003-2009. Prev Med. 2013;56(6):272–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sebire NJ, Jolly M, Harris J, Wadsworth J, Joffe M, Beard R, et al. Maternal obesity and pregnancy outcome: a study of 287,213 pregnancies in London. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(8):1175. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vesga-Lopez O, Blanco C, Keyes K, Olfson M, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):805. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, Stijnen T, Cuijpers P, Penninx BW, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):220. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Chiu WT, Deitz AC, Hudson JI, Shahly V, et al. The Prevalence and Correlates of Binge Eating Disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73(9):904–14. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldstein BI, Liu SM, Zivkovic N, Schaffer A, Chien LC, Blanco C. The burden of obesity among adults with bipolar disorder in the United States. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13(4):387–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00932.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter AS, Baker CW, Brownell KD. Body mass index, eating attitudes, and symptoms of depression and anxiety in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(2):264–70. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200003000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodnar LM, Wisner KL, Moses-Kolko E, Sit DK, Hanusa BH. Prepregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain, and the likelihood of major depressive disorder during pregnancy. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009 Sep;70(9):1290–6. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claesson IM, Josefsson A, Sydsjo G. Prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms among obese pregnant and postpartum women: an intervention study. BMC public health. 2010;10:766. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–84. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loney P, Chambers L, Bennett K, Roberts J, Stratford P. Critical appraisal of the health research literature: prevalence or incidence of a health problem. Chronic Dis Can. 1998;19:170–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, Abrams KR, Rushton L. Comparison of two methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295(6):676–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.6.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J, Mao J, Du Y, et al. Health-related quality of life among pregnant women with and without depression in Hubei, China. Matern Child Health J. 2012 Oct;16(7):1355–63. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0900-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lukose A, Ramthal A, Thomas T, Bosch R, Kurpad AV, Duggan C, et al. Nutritional factors associated with antenatal depressive symptoms in the early stage of pregnancy among urban south indian women. Matern Child Health J. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1249-2. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soares RM, Antunes Nunes MA, Schmidt MI, Giacomello A, Manzolli P, Camey S, et al. Inappropriate eating behaviors during pregnancy: Prevalence and associated factors among pregnant women attending primary care in Southern Brazil. Int J Eat Disord. 2009 Jul;42(5):387–93. doi: 10.1002/eat.20643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiu C, Sanchez SE, Lam N, Garcia P, Williams MA. Associations of depression and depressive symptoms with preeclampsia: results from a Peruvian case-control study. BMC Women’s Health. 2007;7(1):15. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Paz NC, Sanchez SE, Huaman LE, Chang GD, Pacora PN, Garcia PJ, et al. Risk of placental abruption in relation to maternal depressive, anxiety and stress symptoms. J Affect Disord. 2011;130(1):280–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Da Rocha CM, Kac G. High dietary ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 polyunsaturated acids during pregnancy and prevalence of post-partum depression. Matern Child Nutr. 2012;8(1):36–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2010.00256.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xuto P, Sinsuksai N, Piaseu N, Nityasuddhi D, Phupong V. A Causal Model of Postpartum Weight Retention among Thais. Pac Rim Int J Nurs Res Thail. 2012;16(1):48–63. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rondo PHC, Souza MR, Moraes F, Nogueira F. Relationship between nutritional and psychological status of pregnant adolescents and non-adolescents in Brazil. J Health Popul Nutr. 2004;22(1):34–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matijasevich A, Golding J, Smith GD, Santos IS, Barros AJ, Victora CG. Differentials and income-related inequalities in maternal depression during the first two years after childbirth: birth cohort studies from Brazil and the UK. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2009;5(12) doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-5-12. doi: 10.1186/745-0179-5-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carlosh K, Allen S, Dalton WT, III, Bailey BA. Weight concern, body image, and compensatory behaviors in rural pregnant smokers: A preliminary investigation. [References] Journal of Rural Mental Health. 2011;35(1):17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fowles ER, Timmerman GM, Bryant M, Kim S. Eating at fast-food restaurants and dietary quality in low-income pregnant women. West J Nurs Res. 2011;33(5):630–51. doi: 10.1177/0193945910389083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tenfelde S, Finnegan L, Hill P. Predictors of breastfeeding exclusivity and duration in a sample of WIC participants. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2011;40(2):179–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2011.01224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walker LO, Freeland-Graves JH, Milani T, George G, Hanss-Nuss H, Kim M, et al. Weight and Behavioral and Psychosocial Factors Among Ethnically Diverse, Low-Income Women After Childbirth: II. Trends and Correlates. Women Health. 2004;40(2):19–34. doi: 10.1300/J013v40n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker LO, Sterling BS, Kim M, Arheart KL, Timmerman GM. Trajectory of weight changes in the first 6 weeks postpartum. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35(4):472–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allison KC, Wrotniak BH, Paré E, Sarwer DB. Psychosocial Characteristics and Gestational Weight Change among Overweight, African American Pregnant Women. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/878607. Article ID 878607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiely M, El-Mohandes A, Gantz M, Chowdhury D, Thornberry J, El-Khorazaty M. Understanding the Association of Biomedical, Psychosocial and Behavioral Risks with Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Among African-Americans in Washington, DC. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:85–95. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0856-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruiz RJ, Marti CN, Pickler R, Murphey C, Wommack J, Brown CEL. Acculturation, depressive symptoms, estriol, progesterone, and preterm birth in Hispanic women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(1):57–67. doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0258-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azar R, Singer S. Maternal prenatal state anxiety symptoms and birth weight: A pilot study. Cent Eur J Med. 2012;7(6):747–52. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kothari CL, Wendt A, Liggins O, et al. Assessing maternal risk for fetal-infant mortality: a population-based study to prioritize risk reduction in a healthy start community. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(1):68–76. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0561-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kabir K, Sheeder J, Stevens-Simon C. Depression, Weight Gain, and Low Birth Weight Adolescent Delivery: Do Somatic Symptoms Strengthen Or Weaken the Relationship? J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2008;21(6):335–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gould Rothberg BE, Magriples U, Kershaw TS, Rising SS, Ickovics JR. Gestational weight gain and subsequent postpartum weight loss among young, low-income, ethnic minority women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(1):52.e1–.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christian LM, Franco A, Glaser R, Iams JD. Depressive symptoms are associated with elevated serum proinflammatory cytokines among pregnant women. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23(6):750–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christian LM, Iams JD, Porter K, Glaser R. Epstein-Barr virus reactivation during pregnancy and postpartum: Effects of race and racial discrimination. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(8):1280–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gavin AR, Holzman C, Siefert K, Tian Y. Maternal depressive symptoms, depression, and psychiatric medication use in relation to risk of preterm delivery. Womens Health Issues. 2009;19(5):325–34. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rallis S, Skouteris H, Wertheim EH, Paxton SJ. Predictors of body image during the first year postpartum:a prospective study. Women Health. 2007;45(1):87–104. doi: 10.1300/J013v45n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voegtline KM, Costigan KA, Kivlighan KT, Laudenslager ML, Henderson JL, DiPietro JA. Concurrent levels of maternal salivary cortisol are unrelated to self-reported psychological measures in low-risk pregnant women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16(2):101–8. doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0321-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Latendresse G, Ruiz RJ, Wong B. Psychological distress and SSRI use predict variation in inflammatory cytokines during pregnancy. Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2013;3:184–91. doi: 10.4236/ojog.2013.31A034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cassidy-Bushrow AE, Peters RM, Johnson DA, Li J, Rao DS. Vitamin D Nutritional Status and Antenatal Depressive Symptoms in African American Women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21(11):1189–95. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ban L, Gibson JE, West J, Fiaschi L, Oates MR, Tata LJ. Impact of socioeconomic deprivation on maternal perinatal mental illnesses presenting to UK general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2012 Oct;62(603):e671–e8. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X656801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown SJ, McDonald EA, Krastev AH. Fear of an intimate partner and women’s health in early pregnancy: findings from the Maternal Health Study. Birth. 2008;35(4):293–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2008.00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyake Y, Tanaka K, Okubo H, Sasaki S, Arakawa M. Fish and fat intake and prevalence of depressive symptoms during pregnancy in Japan: Baseline data from the Kyushu Okinawa Maternal and Child Health Study. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(5):572–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rauff EL, Downs DS. Mediating effects of body image satisfaction on exercise behavior, depressive symptoms, and gestational weight gain in pregnancy. nn Behav Med. 2011;42(3):381–90. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9300-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haeri S, Johnson N, Baker AM, et al. Maternal depression and Epstein-Barr virus reactivation in early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):862–6. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820f3a30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Micali N, Simonoff E, Treasure J. Pregnancy and post-partum depression and anxiety in a longitudinal general population cohort: The effect of eating disorders and past depression. J Affect Disord. 2011;131(1-3):150–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dayan J, Creveuil C, Herlicoviez M, et al. Role of anxiety and depression in the onset of spontaneous preterm labor. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155(4):293–301. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Demissie Z, Siega-Riz AM, Evenson KR, Herring AH, Dole N, Gaynes BN. Physical activity and depressive symptoms among pregnant women: The PIN3 study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14(2):145–57. doi: 10.1007/s00737-010-0193-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Poppel MN, Hartman MA, Hosper K, et al. Ethnic differences in weight retention after pregnancy: the ABCD study. Eur J Public Health. 2012;22(6):874–9. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ertel KA, Kleinman K, Van Rossem L, Sagiv S, Tiemeier H, Hofman A, et al. Maternal perinatal depression is not independently associated with child body mass index in the generation r study: Methods and missing data matter. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(12):1300–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kovacs FM, Garcia E, Royuela A, Gonzalez L, Abraira V. Prevalence and factors associated with low back pain and pelvic girdle pain during pregnancy: A multicenter study conducted in the spanish national health service. Spine. 2012;37(17):1516–33. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31824dcb74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li D, Liu L, Odouli R. Presence of depressive symptoms during early pregnancy and the risk of preterm delivery: A prospective cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(1):146–53. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bogaerts A, Devlieger R, Nuyts E, Witters I, Gyselaers W, Van den Bergh B. Effects of lifestyle intervention in obese pregnant women on gestational weight gain and mental health: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Obes. 2013;37(6):814–21. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ertel KA, Koenen KC, Rich-Edwards JW, et al. Antenatal and postpartum depressive symptoms are differentially associated with early childhood weight and adiposity. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2010;24(2):179–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2010.01098.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ibanez G, Charles M-A, Forhan A, Magnin G, Thiebaugeorges O, Kaminski M, et al. Depression and anxiety in women during pregnancy and neonatal outcome: Data from the EDEN mother-child cohort. Early Hum Dev. 2012;88(8):643–9. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bodnar LM, Wisner KL, Moses-Kolko E, Sit DK, Hanusa BH. Prepregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain, and the likelihood of major depressive disorder during pregnancy. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2009 Sep;70(9):1290–6. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bombard J, Dietz P, Galavotti C, England L, Tong V, Hayes D, et al. Chronic Diseases and Related Risk Factors among Low-Income Mothers. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(1):60–71. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ingram JC, Greenwood RJ, Woolridge MW. Hormonal predictors of postnatal depression at 6 months in breastfeeding women. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2003;21(1):61–8. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miyake Y, Sasaki S, Yokoyama T, et al. Risk of postpartum depression in relation to dietary fish and fat intake in Japan: the Osaka Maternal and Child Health Study. Psychol Med. 2006;36(12):1727–35. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nicklas JM, Miller LJ, Zera CA, Davis RB, Levkoff SE, Seely EW. Factors Associated with Depressive Symptoms in the Early Postpartum Period Among Women with Recent Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Matern Child Health J. 2012 Nov 3; doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1180-y. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sundaram S, Harman J, Peoples-Sheps M, Hall A, Simpson S. Obesity and Postpartum Depression: Does Prenatal Care Utilization Make a Difference? Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(3):656–67. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0808-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Urquia ML, O’Campo PJ, Heaman MI. Revisiting the immigrant paradox in reproductive health: The roles of duration of residence and ethnicity. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(10):1610–21. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chatzi L, Melaki V, Sarri K, Apostolaki I, Roumeliotaki T, Georgiou V, et al. Dietary patterns during pregnancy and the risk of postpartum depression: the mother-child ‘Rhea’ cohort in Crete, Greece. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(9):1663–70. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010003629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dotlic J, Terzic M, Babic D, Vasiljevic N, Janosevic S, Janosevic L, et al. The influence of body mass index on the perceived quality of life during pregnancy. Appl Res Qual Life. 2013 DOI 10.1007/s11482-013-9224-z. [Google Scholar]

- 66.LaCoursiere DY, Barrett-Connor E, O’Hara MW, et al. The association between prepregnancy obesity and screening positive for postpartum depression. BJOG. 2010;117(8):1011–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.LaCoursiere D, Baksh L, Bloebaum L, Varner MW. Maternal Body Mass Index and Self-Reported Postpartum Depressive Symptoms. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(4):385–90. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harville EW, Savitz DA, Dole N, Herring AH, Thorp JM. Stress questionnaires and stress biomarkers during pregnancy. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18(9):1425–33. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dipietro JA, Millet S, Costigan KA, et al. Psychosocial influences on weight gain attitudes and behaviors during pregnancy. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003 Oct;103(10):1314–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(03)01070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Catov JM, Abatemarco DJ, Markovic N, Roberts JM. Anxiety and Optimism Associated with Gestational Age at Birth and Fetal Growth. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(5):758–64. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0513-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Easter A, Bye A, Taborelli E, Corfield F, Schmidt U, Treasure J, et al. Recognising the Symptoms: How Common Are Eating Disorders in Pregnancy? Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2013;21(4):340–4. doi: 10.1002/erv.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bulik CM, Von Holle A, Hamer R, Berg CK, Torgersen L, Magnus P, et al. Patterns of remission, continuation, and incidence of broadly defined eating disorders during early pregnancy in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa) Psychol Med. 2007;37(8):1109. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Boden R, Lundgren M, Brandt L, et al. Antipsychotics during pregnancy: relation to fetal and maternal metabolic effects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(1):715–21. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Holland E, Simas TAM, Curiale DKD, Liao X, Waring ME. Self-reported Pre-pregnancy Weight Versus Weight Measured at First Prenatal Visit: Effects on Categorization of Pre-pregnancy Body Mass Index. Matern Child Health J. 2012 Dec 18; doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1210-9. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.White MA, Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Accuracy of self-reported weight and height in binge eating disorder: misreport is not related to psychological factors. Obesity. 2009;18(6):1266–9. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zimmermann U, Kraus T, Himmerich H, Schuld A, Pollmächer T. Epidemiology, implications and mechanisms underlying drug-induced weight gain in psychiatric patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37(3):193–220. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(03)00018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bowers K, Laughon SK, Kim S, Mumford SL, Brite J, Kiely M, et al. The Association between a Medical History of Depression and Gestational Diabetes in a Large Multi-ethnic Cohort in the United States. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/ppe.12057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Linde J, Jeffery R, Levy R, Sherwood N, Utter J, Pronk N, et al. Binge eating disorder, weight control self-efficacy, and depression in overweight men and women. Int J Obes. 2004;28(3):418–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.