Abstract

Rationale

Chronic low-grade inflammation involving adipose tissue likely contributes to the metabolic consequences of obesity. The cytokine IL-33 and its receptor ST2 are expressed in adipose tissue but their role in adipose tissue inflammation during obesity is unclear.

Objective

To examine the functional role of IL-33 in adipose tissues, and investigate the effects on adipose tissue inflammation and obesity in vivo.

Methods and Results

We demonstrate that treatment of adipose tissue cultures in vitro with IL-33 induced production of Th2 cytokines (IL-5, IL-13, IL-10), and reduced expression of adipogenic and metabolic genes. Administration of recombinant IL-33 to genetically obese diabetic (ob/ob) mice led to reduced adiposity, reduced fasting glucose and improved glucose and insulin tolerance. IL-33 also induced accumulation of Th2 cells in adipose tissue and polarization of adipose tissue macrophages towards an M2 alternatively activated phenotype (CD206+), a lineage associated with protection against obesity-related metabolic events. Furthermore, mice lacking endogenous ST2 fed HFD had increased body weight and fat mass, impaired insulin secretion and glucose regulation compared to WT controls fed HFD.

Conclusions

In conclusion, IL-33 may play a protective role in the development of adipose tissue inflammation during obesity.

Keywords: obesity, inflammation, diabetes mellitus, interleukins

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a consequence of many complex factors, including increased calorie consumption and reduced physical activity. Many studies also implicate chronic low grade inflammation in the interplay between obesity and metabolic complications [reviewed in 1]. During obesity white adipose tissue (WAT) is infiltrated by immune cells, such as macrophages and T cells 2-4, which along with the adipocytes themselves secrete a variety of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [reviewed in 5]. Recent studies demonstrate that the infiltrating T cells display a Th1 pattern of activation with enhanced IFNγ production 6, and that an imbalance may exist in obese adipose between dominant Th1 responses and reduced Treg or Th2 responses 7-9. This in turn leads to macrophage recruitment and a switch from a protective alternatively activated (M2) macrophage to a classically activated (M1) pro-inflammatory phenotype 7, 10.

Several observations indicate a role for the interleukin (IL)-1 family of cytokines in obesity. IL-1 inhibits adipocyte differentiation, stimulation of lipolysis, and induces the development of an insulin resistant phenotype 11. Adipocytes also produce IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) and levels of IL-1Ra are strongly elevated in the serum of obese patients and highly correlated with insulin resistance 12. IL-18 concentrations are increased in serum of individuals with obesity and type 2 diabetes 13, but absence of IL-18 or IL-18R or the over-expression of IL-18 binding protein in genetically modified mice, leads to abnormalities characteristic of the metabolic syndrome 14. Furthermore, inhibition of IL-1 associated pathways in patients with diabetes improved glycemia and beta-cell secretory function and reduced markers of systemic inflammation 15, 16. These findings highlight the therapeutic potential of targeting IL-1 family of cytokines in type 2 diabetes.

IL-33 is a newly identified member of the IL-1 cytokine family that induces production of Th2 cytokines 17, by interacting with a heterodimeric receptor comprising ST2 and IL-1 Receptor Accessory Protein (IL-1Racp) 18. The ST2 gene encodes 2 protein isoforms: ST2L, a trans-membrane receptor, and a secreted soluble ST2 (sST2) form which can serve as a decoy receptor for IL-33. Several lines of evidence suggest a role for the IL-33/ST2 pathway in cardiovascular biology. Serum elevations of sST2 predict mortality and heart failure in patients with acute myocardial infarction 19, 20. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that the IL-33/ST2 pathway has a protective role in the progression of atherosclerosis via the induction of Th2 cytokines and anti-oxLDL antibodies 21. More recently, IL-33 and ST2 were shown to be expressed in human adipose tissue 22.

In this study we show that IL-33 has clear protective effects against obesity and type 2 diabetes. IL-33 induced Th2 cytokines in WAT and the polarization of WAT macrophages towards an M2 alternatively activated phenotype with reduced adipose mass and fasting glucose. Taken together these results demonstrate a novel protective role for IL-33/ST2 during obesity and suggest that induction of Th2 cytokines and alternative macrophage polarization by manipulating IL-33 expression may be a useful therapeutic strategy for treating or preventing type 2 diabetes in obese patients.

RESULTS

IL-33 induced Th2 cytokines and chemokines in WAT cultures in vitro

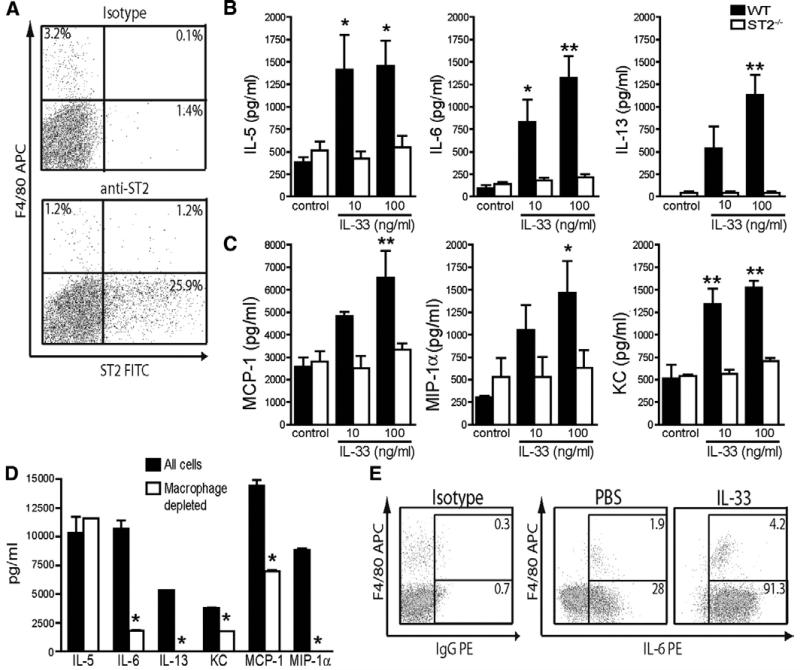

To establish the cellular localization of ST2 expression in WAT we carried out flow cytometric double immunostaining of collagenase digested murine epididymal stromal vascular fraction (SVF) cells. Both F4/80+ macrophages and F4/80− cells expressed ST2 (Figure 1A), indicating the potential for multiple cell types in WAT to respond to IL-33. We then examined the effect of IL-33 treatment on cytokine and chemokine secretion from murine SVF cells cultured from epididymal WAT (eWAT) of WT and ST2−/− mice in vitro. Addition of IL-33 to SVF cultures from WT but not ST2−/− mice induced secretion of the cytokines IL-5, IL-6, IL-13 (Figure 1B) and chemokines MCP-1, MIP-1α and KC (Figure 1C). Macrophage depletion markedly reduced, but did not abolish, IL-33-induced expression of IL-6, MCP-1 and KC (Figure 1D). However, IL-33-induced expression of IL-13 and MIP-1α were completely abolished by macrophage depletion. In contrast, IL-5 expression was unaffected by macrophage depletion. Intracellular staining in IL-33-treated SVF cultures demonstrated IL-6 expression in both F4/80+ and F4/80− cells (Figure 1E). These studies indicate that IL-33 can act on both macrophages and other F4/80− cells in the SVF (eg pre-adipocytes) to induce cytokine and chemokine production.

Figure 1. IL-33 induces Th2 cytokines and chemokines in both macrophages and adipocytes in WAT cultures.

Epididymal fat pads from 10 age-matched male BALB/c WT (filled bars) and BALB/c × ST2−/− (open bars) mice were pooled, dissected and separated into mature adipocyte and SVF populations. (A) Expression of ST2 by FACS in SVF cells from BALB/c mice stained with anti-F4/80 and either isotype control or anti-ST2 mAbs. SVF cells were then cultured for 7 days ± IL-33 (10-100 ng/ml). (A) Cytokines and (B) chemokines in cell supernatants (all pg/ml) collected on day 7 were measured by Luminex assay. Data shown are Means ± SEM, n=4-5 independent experiments. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001 One-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post test comparing all values to respective control column or students unpaired t test. Cells with or without macrophages depleted (by F4/80+ cell sorting) were then cultured for 7 days ± IL-33 (10 ng/ml) and (C) cytokines and chemokines measured on day 7 were measured by Luminex assay, or (D) intracellular cytokine staining for IL-6 in day 7 SVF cells re-stimulated with PMA/Ionomycin/GolgiPlug. Numbers indicate mean % of CD45+ cells. Data are Means ± SEM, n=2-3 independent experiments. * p<0.05 students unpaired t test.

IL-33 induces changes in lipid storage and expression of metabolic genes in WAT cultures in vitro

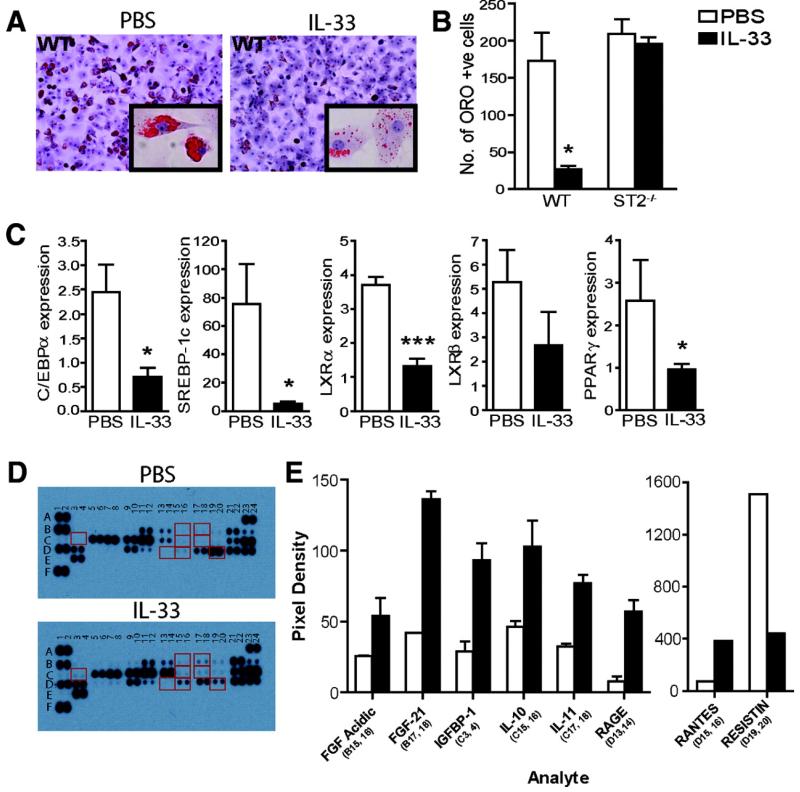

In order to further investigate the mechanisms of action of IL-33 in WAT we examined the effect of IL-33 on adipocyte differentiation in vitro. Addition of IL-33 for 7 days during the differentiation process of murine SVF cells significantly inhibited lipid accumulation (ORO staining) (Figure 2A), and this effect was absent in cells from ST2−/− mice (Figure 2B). IL-33-treatment also reduced the mRNA expression of C/EBPα, SBRBP-1c, LXRα, LXRβ, and PPARγ, all associated with lipid metabolism and adipogenesis (Figure 2C). Furthermore, we used a mouse proteome array to simultaneously examine the expression of 38 obesity-related proteins in the supernatants of IL-33-treated (100 ng/ml) SVF cultured cells (Figure 2D-E). The expression of molecules shown to be protective against obesity such as FGF-acidic, FGF-21, IGFBP-1, IL-10, IL-11, and RAGE 23-26, were >2 fold increased by IL-33, while expression of Resistin, which induces insulin resistance 27, was <2 fold decreased by IL-33. Taken together these results indicate that IL-33 has potent effects on adipocyte differentiation and expression of metabolic genes and adipokine proteins in SVF cultures and support a role for IL-33 in the metabolic regulation of WAT.

Figure 2. IL-33 induces changes in lipid storage and expression of metabolic genes in WAT cultures in vitro.

SVF cells from BALB/c WT or BALB/c ST2−/− mice were cultured for 7 days ± PBS (open bars) or IL-33 (100 ng/ml, filled bars). (A) Oil Red O (ORO) staining for lipid storage analysis (20× magnification, inset 40×), and (B) mean number of ORO+ cells quantified (counted from 5 randomly selected microscope fields on duplicate slides) (n=3). (C) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of total RNA extracted on day 7 for expression of adipogenic and metabolic genes compared to TBP endogenous control. (D-E) Mouse obesity array on SVF supernatants. Representative membrane images (D), and quantification of mean spot pixel density for genes >2 fold up- or down-regulated (E). Data are Means ± SEM, n=3-5 independent experiments. p<0.05, *** p<0.001 students unpaired t test.

The effect of exogenous IL-33 on metabolic parameters in vivo

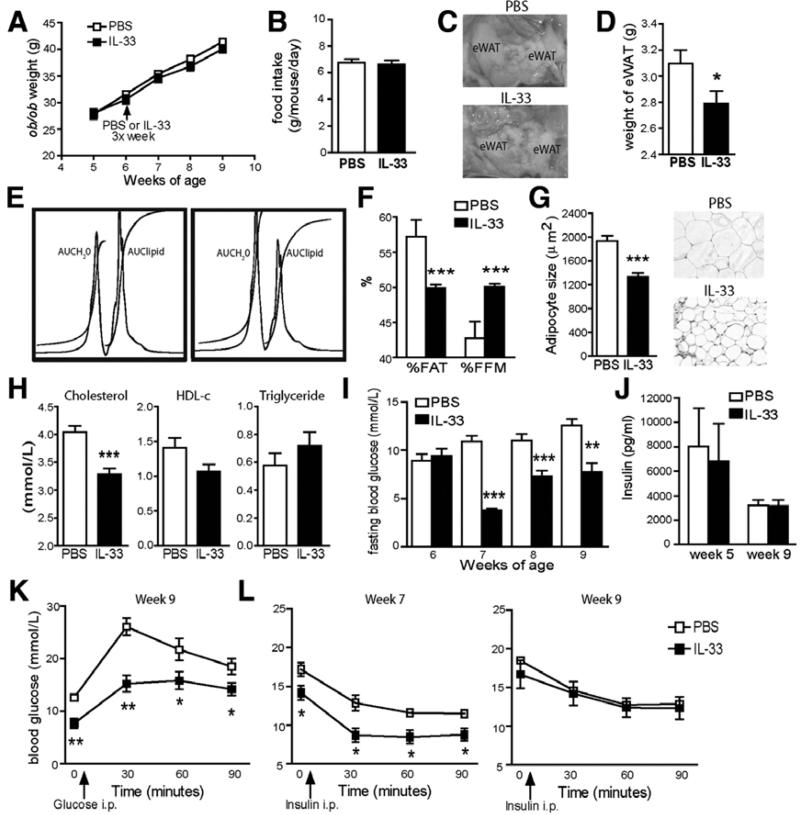

To directly investigate the effect of IL-33 on obesity in vivo, we treated spontaneously obese (ob/ob) mice with PBS or recombinant IL-33. IL-33 did not affect the final body weight of ob/ob mice (Figure 3A, PBS treated, 41.4 ± 0.7 g vs. IL-33-treated, 40.1 ± 0.7 g) or food intake (Figure 3B), but eWAT weight was decreased by 9.9% (Figure 3C-D). Furthermore, IL-33-treated mice displayed a 13% decrease in body fat (AUClipid) and a 17% increase in fat free mass (FFM, AUCH2O), compared to PBS-treated controls (Figure 3E-F) by magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) analysis. Mean adipocyte size in eWAT was reduced in IL-33-treated ob/ob mice (Figure 3G, PBS treated, 1935 ± 90 μm2 vs. IL-33-treated, 1335 ± 68 μm2; p<0.001). In addition, IL-33-treatment significantly reduced total serum cholesterol (4.0 ± 0.1 vs. 3.3 ± 0.1 mmol/L), but did not affect HDL-c (1.4 ± 0.1 vs. 1.1 ± 0.1 mmol/L), or triglyceride (0.6 ± 0.1 vs. 0.7 ± 0.1 mmol/L) concentrations (Figure 3H).

Figure 3. IL-33 induces changes in adiposity and metabolic parameters in vivo.

Ob/ob mice were treated with PBS (open symbols/bars) or IL-33 (filled symbols/bars) 3x/week for 3 weeks. (A) Body weight (g). (B) Food intake (g/mouse/day). (C) Representative epididymal fat pad (eWAT) images, and (D) eWAT weights. (E) Representative proton whole body MRS spectra and analysis (n=6) showing areas under the curve (AUC) for water (H2O) and lipid peaks, and (F) Percentages of body fat (%FAT) and fat free mass by MRS (%FFM). (G) Mean adipocyte size expressed in μm2 and representative histology of eWAT stained with hematoxylin and eosin (original magnification 20×). (H) Total serum cholesterol, HDL-c and triglyceride levels (mmol/L). (I) Weekly blood fasting glucose levels (mmol/L) after 16 hr overnight fast. (J) Fasting serum insulin levels (pg/ml) after 16 hr overnight fast at week 5 and 9. (K) Glucose and (L) insulin tolerance tests at week 7 or 9 in ob/ob mice. Data are Means ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments, n=10 mice/group. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001 students unpaired t test.

Weekly analysis of fasting blood glucose levels in IL-33-treated ob/ob mice demonstrated lower levels than the PBS-treated controls (Figure 3I). Surprisingly though, no significant difference in serum insulin levels was found (Figure 3J), suggesting that insulin secretion was not altered by IL-33, nor responsible for the lowered fasting glucose levels. IL-33-treated mice also showed significantly lower glucose levels after a glucose load (Figure 3K). In order to investigate whether altered insulin sensitivity explains the changes in glucose levels and tolerance we carried out an insulin tolerance test in the mice at week 7 and 9. Improved insulin sensitivity was found in IL-33-treated mice at week 7 but not at week 9 (Figure 3L), when perhaps some tolerance to the effects of IL-33 were evident.

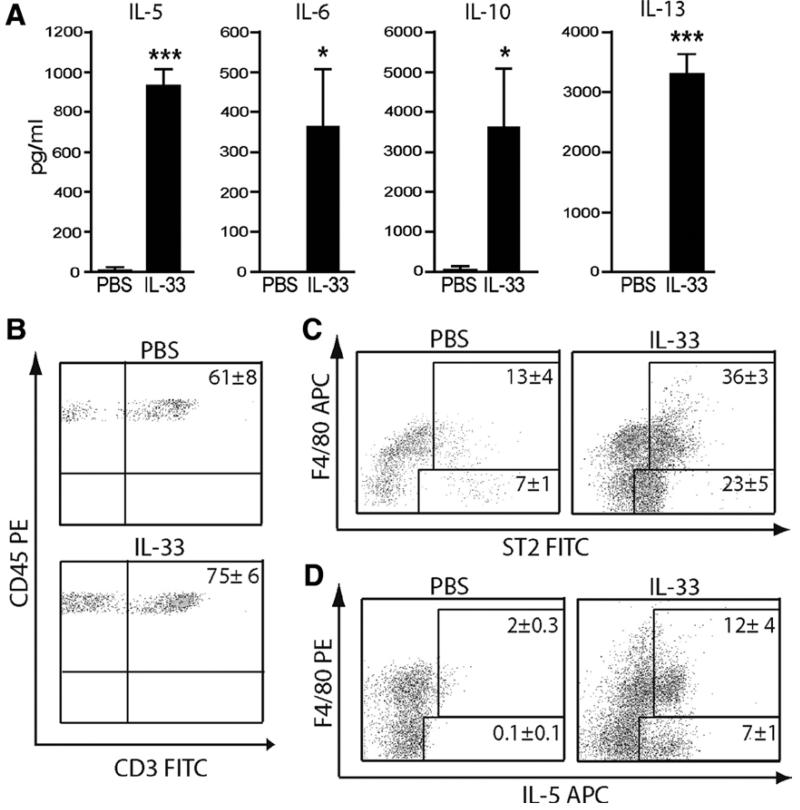

IL-33 induces accumulation of Th2 cytokines in serum and Th2 cells in WAT

We analyzed changes in circulating cytokines and adipokines following IL-33 treatment in serum of ob/ob mice. IL-33-treated mice produced markedly more IL-5, IL-6, IL-10 and IL-13 (Figure 4A) than PBS-treated mice, but no significant change in TNFα, MCP-1, Resistin or tPAI-1 (data not shown). Furthermore, given the large increase in the chemokines MCP-1, MIP1α and KC released by IL-33-treated SVF cultures we assessed inflammatory cell infiltration into eWAT from PBS vs. IL-33-treated ob/ob mice using the markers CD45 (pan-leukocytes) and F4/80 (macrophages). IL-33 induced the accumulation of CD45+F4/80− cells in eWAT. Further analysis revealed these cells to be 75% CD3+ T cells (Figure 4B). CD3+ T cells were also found in eWAT of PBS-treated mice but at a lower frequency (61%). Expression of ST2, a marker for a subpopulation of Th2 cells 28, was increased in both CD45+F480+ cells and in CD45+F480− cells (75% of which are CD3+) (Figure 4C), indicating that IL-33-treament has induced local accumulation of Th2 cells. Consistent with this, eWAT from IL-33-treated ob/ob mice contained more IL-5-producing CD45+F4/80− and CD45+F4/80+ SVF cells than those from PBS-treated mice (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. IL-33 induces accumulation of Th2 cytokines in serum and Th2 cells in WAT.

(A) Circulating cytokines in serum of ob/ob mice treated with PBS or IL-33. (B-D) Epididymal fat pads from ob/ob mice treated with PBS or IL-33 were collagenase digested for SVF cell isolation and analyzed by FACS. Representative plots show that the majority of CD45+F480− cells are CD3+ T cells (B) and express ST2 (C). Intracellular cytokine staining for IL-5 in SVF cells re-stimulated with PMA/Ionomycin/GolgiPlug (D). All representative plots shown are gated on CD45+ and the numbers indicate mean % of CD45+ positive cells ± St. Dev. in each gate (n=6). Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments.

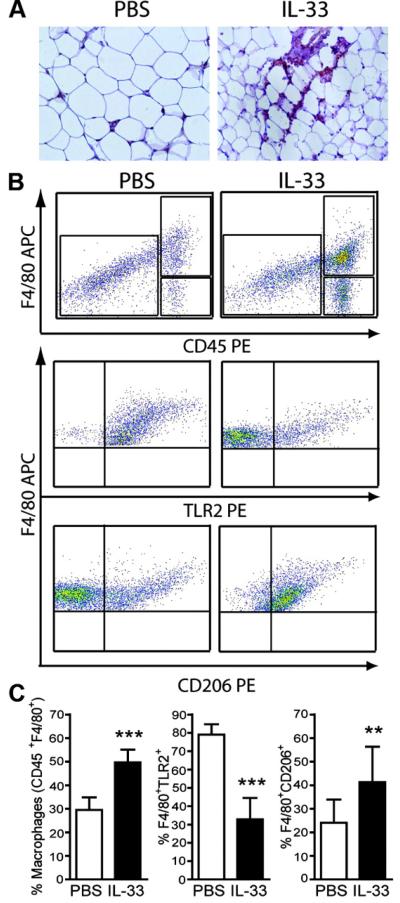

Accumulation of alternatively activated macrophages (M2) in WAT of mice treated with IL-33

Immunohistochemistry on eWAT sections taken from IL-33-treated ob/ob mice demonstrated F4/80+ cells accumulating in clusters around adipocytes (Figure 5A). CD45+F4/80+ SVF cells were significantly increased in IL-33-treated mice compared to PBS-treated mice (Figure 5B-C). To investigate the phenotype of these macrophages, we stained CD45+F4/80+ cells with TLR2 (M1 marker) and CD206 (mannose receptor, M2 marker) antibodies. As shown in Figures 5B and C, PBS-treated ob/ob mice contained a higher frequency of TLR2+ macrophage and lower percent of CD206+ macrophages. In contrast, IL-33-treated ob/ob mice contained a higher frequency of CD206+ macrophages but lower percent of TLR2+ macrophages. Taken together these results suggest that IL-33 treatment increases the accumulation of macrophages in WAT and has substantial influence over their polarization towards an M2 phenotype.

Figure 5. IL-33 induces accumulation of alternatively activated (M2) macrophages in WAT.

Epididymal fat pads from ob/ob mice treated with PBS (open bars) or IL-33 (filled bars) were either formalin fixed and embedded in paraffin wax for immunohistochemistry or collagenase digested for SVF cell isolation and analyzed by FACS. (A) Representative photomicrographs of F4/80+ macrophages (brown) in eWAT (original magnification 40×). (B) Representative FACS plots of CD45+F4/80+ cells in eWAT with subsequent gating showing TLR2 marker expression of classically activated (M1) macrophages and the CD206 marker of alternatively activated (M2) macrophages. (C) Quantification of the % CD45+F4/80+ macrophage cells, and the % of those cells expressing either TLR2 or CD206, in eWAT. Data are Means ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments, n=8-10 mice/group. ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001 students unpaired t test vs. respective control.

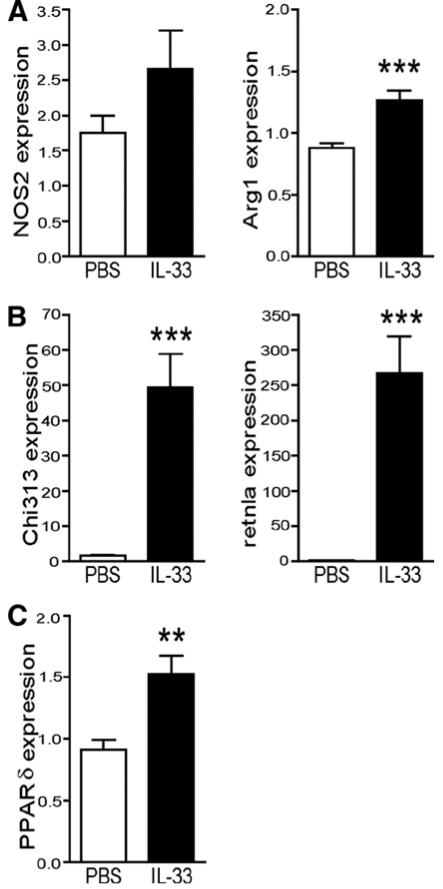

Expression of hepatic M2 macrophage genes in mice treated with IL-33

We examined the metabolic changes and gene expression in the liver of obese mice treated with IL-33. IL-33 treatment did not affect liver weight (3.6 ± 0.2 vs 3.3 ± 0.2 g), serum levels of the aminotransferase enzymes AST (285.8 ± 30.4 vs. 279.6 ± 33.6 U/L) or ALT (27.6 ± 12.0 vs. 28.2 ± 6.4 U/L), or liver histology (data not shown). Additionally, expression of the phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PCK-1) gene, involved in gluconeogenesis in liver, was not altered by IL-33-treatment (mean expression, 1.22 ± 0.08 vs. 1.25 ± 0.09), indicating that down-regulation of PCK-1 is not likely responsible for the glucose lowering actions of IL-33. However, we did not investigate the expression of other genes involved in gluconeogenesis (e.g. glucose-6-phosphatase) and could not exclude that their expression was altered in response to IL-33. Expression levels of SREBP-1c, FAS, LXRα, LXRβ and PGC-1α, were similar in PBS and IL-33-treated mice (data not shown). In contrast, IL-33 strongly enhanced the mRNA expression of M2 markers in liver, including L-Arginase (Arg1), Ym1 (Chi313), RELM/Fizz (retnla) with no significant change in expression of NOS2 (a M1 marker) (Figure 6A-B). Furthermore, expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-δ, associated with M2 macrophage polarization 29, was increased in livers of IL-33-treated mice (Figure 6C). Consistent with the findings in WAT, these results suggest that IL-33 also increases polarization of liver macrophages/Kupffer cells towards an M2 phenotype.

Figure 6. IL-33 induces expression of M2 macrophage genes in liver.

Ob/ob mice were treated with PBS (open bars) or IL-33 (filled bars) 3×/week for 3 weeks, and then sacrificed and liver removed for subsequent quantitative RT-PCR analysis of total RNA extracted for expression of (A) NOS2 and Arg1, (B) Chi313 and retnla and (C) PPARγ. Data are mean gene expression ± SEM compared to TBP endogenous control pooled from 2 independent experiments, n=10 mice/group. ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001 students unpaired t test.

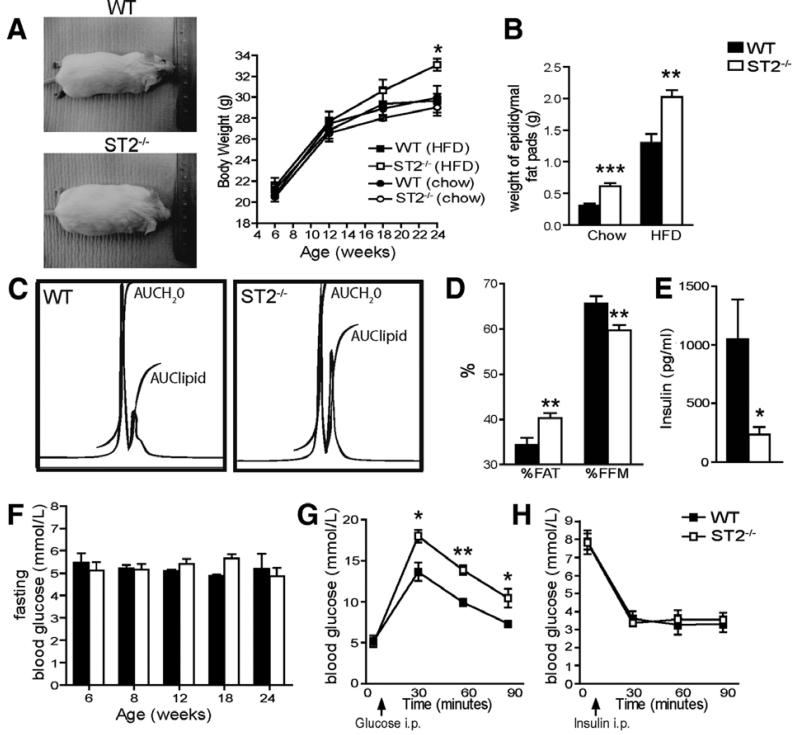

Endogenous ST2 regulates body weight, adipose tissue and glucose homeostasis

To investigate the physiological significance of basal endogenous IL-33/ST2 signaling in metabolism we measured metabolic parameters, body weight/composition of WT and ST2−/− mice over 24 weeks of feeding either normal diet or HFD. On normal diet body weight of ST2−/− mice was similar to that of the WT mice (Figure 7A). Mice on the BALB/c background are generally resistant to diet-induced obesity; however, at 24 weeks of age body weight of ST2−/− mice fed HFD was increased by on average 11.5% compared to WT controls (Figure 7A, p<0.05). Furthermore, weight of eWAT was increased in ST2−/− mice fed either HFD (2.0 vs. 1.3g, p<0.01) or normal diet (0.62 vs. 0.31g, p<0.0001) when compared to WT controls (Figure 7B). ST2−/− mice displayed a 17% increase in % body fat (AUClipid) and a 9% decrease in FFM (AUCH2O), compared to WT controls (Figure 7C-D) fed HFD at 24 weeks of age. However, serum total cholesterol, triglycerides and HDL cholesterol were not different between WT and ST2−/− mice (data not shown).

Figure 7. Endogenous ST2 affects body weight, adipose tissue and glucose homeostasis.

WT or ST2−/− mice were fed either normal diet or HFD for 24 weeks. (A) Representative WT and ST2−/− mice photographed at 24 weeks of age and body weight (g) of the mice over 24 weeks. (B) eWAT weights from WT and ST2−/− mice at 24 weeks of age. (C) Representative proton whole body MRS spectra and analysis of HFD-fed WT and ST2−/− mice at 24 weeks of age showing area under the curve (AUC) for water (H2O) and lipid peaks and (D) percentages of body fat (%FAT) and fat free mass by MRS (%FFM). (E) Fasting serum insulin levels (pg/ml) at week 24. (F) Fortnightly blood fasting glucose levels (mmol/L). Glucose (G) and insulin (H) tolerance tests in 24 week old HFD-fed WT and ST2−/− mice (n=5). Data are Means ± SEM pooled from 2 independent experiments, n=8-9 mice/group. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001 students unpaired t test.

In order to investigate whether the obese phenotype in ST2−/− mice fed HFD is mediated through effects on glucose homeostasis we measured fasting insulin and glucose. Fasting serum insulin concentration was significantly lower at 24 weeks compared to WT controls (Figure 7E), but fasting glucose levels, measured every 2 weeks, were not different between ST2−/− mice and WT controls (Figure 7F). However, at 24 weeks ST2−/− mice were more hyperglycaemic in response to intraperitoneal glucose than WT controls (Figure 7G), but insulin responsiveness was not different (Figure 7H). These results suggest that ST2−/− mice are not insulin resistant but may have impaired pancreatic insulin production in response to glucose overload. Taken together, these data demonstrate that ST2 signaling appears to play some role in controlling body weight gain, and the regulation of WAT and glucose homeostasis.

DISCUSSION

In this paper we show for the first time that IL-33 treatment can modulate cytokine production and macrophage phenotype in WAT and liver, and induce protective effects on body composition and glucose homeostasis.

While IL-33 has already been shown to be expressed in adipose tissue 22, the cellular source of IL-33 in adipose tissue is still unclear. However, recent studies have shown endothelial cells express IL-33 as a vascular alarmin 30, and macrophages and fibroblasts in other tissues express IL-33 (Ref. 31, 32). Therefore, multiple cell types in adipose tissue have the potential to produce IL-33. Treatment of ob/ob mice with IL-33 led to production of strong Th2 responses in WAT. Our findings agree with Kang et al who have previously demonstrated that adipocytes can produce the Th2 cytokines, IL-4 and IL-13 (Ref. 33), which led to alternative activation of macrophages. Furthermore, recent work suggests that during obesity a relatively constant pool of Th2 fat-associated T cells fail to limit an expanding Th1 pool of pro-inflammatory cells and that Th2 cells exert protective functions in insulin resistance 8. In addition, a recent study has documented the existence of a new population of cells, termed ‘natural helper cells’, in fat which are ST2 positive, respond to IL-33 and produce large amounts of Th2 cytokines 34, though the role of these cells in obesity is not yet known. Therefore, IL-33 may exert its protective effects via an expansion of a Th2 pool of fat-associated T cells or natural helper cells and increased production of Th2 cytokines.

The significance of raised systemic levels of IL-6 in obesity is controversial. In humans, blood levels of IL-6 are elevated in obesity and correlate with adiposity and insulin resistance 35. However, our results show that IL-33 has beneficial effects on metabolism despite an increase in circulating IL-6. It has previously been shown in mice that absence of IL-6 led to maturity onset obesity though a central action 36. Furthermore, infusion of IL-6 in mice affected adipose insulin sensitivity but did not affect systemic glucose tolerance test or HOMA index 37. Therefore, the effects of IL-6 in the context of metabolism may be species-dependent. In addition, IL-33 induced expression of several chemokines in WAT and an increase in the proportion of infiltrating macrophages into WAT of obese mice. While MCP-1 is reported to recruit M1 macrophages and have detrimental effects on obesity and metabolism 38, the IL-33-induced macrophages did not have a classical pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype. It is possible that M1 macrophages were recruited which then switched to an M2 upon encountering an IL-33-driven local Th2 environment in WAT. Consistent with this notion, IL-33 increased expression of M2 markers (CD206, Arginase 1, Ym1/chitinase 3-like 3 and FIZZ/RELM, IL-10, and PPARδ) in adipose tissue and liver. Two recent studies document that PPARδ plays a key role in alternative activation of resident macrophages in WAT and liver 29, 33. Furthermore, deletion of PPARδ in macrophages led to impaired glucose tolerance and exacerbation of insulin resistance. In liver, Odegaard et al demonstrated that PPARδ is critical for maintaining an M2 phenotype of Kupffer cells and this leads to hepatic dysfunction and insulin resistance 29. Alternatively activated M2 macrophages can regulate insulin resistance through the production of IL-10. This IL-10 can reverse the pro-inflammatory cytokine-induced activation of serine kinases, which phosphorylate IRS-1, thus inhibiting the action of insulin 1, 10. It is thus likely that one of the mechanisms by which IL-33 treatment induces protective effects is by promoting Th2 cytokine synthesis leading to the preferential differentiation of M2 macrophages in both adipose and liver.

Investigation of the metabolic phenotype of ST2−/− mice demonstrated that these mice have enhanced weight gain (11.5%) at 24 weeks of age on HFD, and had more adipose tissue compared to WT controls, indicating a mature onset of obesity. However, the obese phenotype of the ST2−/− mice may not be a severe as that seen with other cytokine/cytokine receptor knock out mice, especially as the ST2 phenotype was only seen with high fat feeding. On normal diet IL-18−/− mice were 18.5% heavier at 6 months 14, and both IL-1R1−/− and IL-6−/− mice displayed weight deviation from WT at 5-6 months of age with 20% weight difference by 9 months 36, 39. This comparatively smaller effect in the ST2−/− mice may be a result of their BALB/c background, known to be more obesity resistant than the C57BL/6 background.

In summary, we report a novel function for IL-33 in obesity which is likely to be through the induction of the Th2 cytokines IL-5 and IL-13 which in turn can skew macrophages in adipose and liver from an M1 to M2 phenotype, and hence reduce the chronic inflammatory response associated with obesity. Many questions now arise from this work. IL-33 appears to have catabolic effects and experiments should be carried out to assess its effects on activity levels and energy expenditure, substrate utilization and metabolic rate. In addition, while we have clearly focused on the role of secreted IL-33 the nuclear expression of IL-33 in adipose may also indicate a separate function that is not dependent on its secretion. Further studies to address these points will allow a better understanding of the complex role of the role of IL-1 family cytokines in insulin resistance and obesity.

METHODS

Glucose (GTT) and insulin tolerance tests (ITT)

Both GTT and ITT were carried out 1 day prior to cull of mice. Briefly, mice were fasted for 16 hrs (GTT) or 4hrs (ITT) injected intraperitoneally with filter-sterilized 2 g/kg glucose in 0.9% NaCl (GTT) or with insulin (0.75 U/kg, Sigma) in 25mM Hepes (ITT). A tail vein blood sample was taken before the injection and 30, 60, and 90 minutes after the injection for determination of blood glucose using the Accu-chek Compact test strips (Roche Diagnostics). GTT and ITT were performed on different sets of mice to prevent unnecessary repetitive stress that could interfere with measurements.

Stromal vascular fraction (SVF) cell isolation

Epididymal white adipose tissue (eWAT) from mice was excised and collagenase (C6885, Sigma) digested for 30 minutes at 37°C with shaking. Cells were filtered through a 100 μm filter and then spun at 300 g for 5 minutes to separate floating mature adipocytes from the SVF pellet. Cells were then cultured in 6-well plates (Corning) in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 4 mM L-glutamine, 5 μg/ml insulin, 25 μg/ml sodium ascorbate, 10 mM Hepes, 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin for up to 8 days. After 24 hours any non-adherent cells (e.g. T cells) were removed. Analysis of the cellular composition of these cultures by FACS and immunocytochemistry at day 7 demonstrated no T cells (CD45+CD3+), no endothelial cells (CD31+), 3% macrophages (CD45+F4/80+), and 97% adipocyte-like cells (CD45−, vacuolated, ORO+ lipid-droplet containing).

Analysis of cytokines and adipokines in cell supernatants

Supernatants were collected at various time points after addition of IL-33 (10-100ng/ml) and analyzed on a 20-plex mouse cytokine assay (Biosource) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, or by a Mouse Obesity Proteome Array (R&D Systems). For protein array supernatants were added to a membrane spotted with antibodies against 38 obesity-related proteins and following the addition of Streptavidin-HRP and chemiluminescence detections reagents the membrane was developed on X-ray film and quantitated by scanning on a transmission-mode scanner and analyzing the array image file using Quantity One® analysis software (Bio-Rad).

Flow cytometry and cell sorting

For flow cytometry and cell sorting by FACS Aria (BD Biosciences), SVF cells were resuspended in FACS buffer (PBS, 2% FCS, 2mm EDTA). Cells were incubated with Fc Block (BD Biosciences) for 15 minutes prior to staining with various conjugated antibodies or isotype controls: F4/80-APC (eBioscience), CD45-PE, CD3-FITC (both BD Biosciences), CD206-PE (Serotec), TLR2-PE (eBioscience), or ST2-FITC (MD Biosciences). For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were stimulated for 4 hours with PMA (50 ng/ml, Sigma) and Ionomycin (500 ng/ml, Sigma) in the presence of Golgi-Plug (1 mg/ml, BD Biosciences). The cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained with anti-F4/80 and anti-IL-5 or anti-IL-6 (BD Biosciences). For macrophage depletion experiments CD45+F4/80+ macrophages were positively selected on the FACS Aria. Macrophage depleted populations were confirmed to contain < 1% CD45+F4/80+ cells prior to further experiments.

Oil Red O Staining

Cells were grown in culture slides and then fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin followed by incubation with newly filtered Oil Red O (ORO) staining solution (60 mls of saturated ORO/isopropanol solution was mixed with 40 mls of a 1% dextrin solution). The mean number of ORO positive cells in 5 randomly chosen microscope fields per slide was calculated using Scion Image software (Scion Corporation).

Morphometric and immunohistochemical analysis of WAT

For morphometric analysis 5 μm sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded eWAT were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Forty adipocytes were randomly chosen in each section and the mean adipocyte size was determined using Scion Image software at ×20 magnification. Immunohistochemical staining was performed using molecule-specific and isotype-control antibodies as negative controls: anti-mouse F4/80 (Clone CI:A3-1, Serotec) for macrophages; anti-mouse ST2 (MD Biosciences); anti-mouse IL-33 (R&D Systems); anti-human IL-33 (Axxora, NESSY-1); anti-human ST2L (MAB10041, R&D Systems). Staining was visualized using biotinylated secondary antibodies and detection with the ABC/DAB system or Avidin FITC (Vector).

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA from eWAT and liver was prepared by tissue homogenization in 1 ml of Qiazol (Qiagen) or Trizol (Invitrogen) respectively. Gene expression was analyzed on the Applied Biosystems ABI7900HT machine with SDS 2.2 software. Gene expression was normalized to TATA binding protein (TBP) using Assays on Demand and QPCR master mix (Applied Biosystems). The following TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) were used: TBP (Mm00446973_m1), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 (PCK1, Mm00440636_m1), CAAT enhancer–binding protein-α (C/EBP-α, Mm01265914_s1), peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ and δ (PPAR-γ/δ, Mm01184322_m1 and Mm01305434_m1), peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ co-activator 1α (PGC-1α, Mm00447183_m1), liver X receptors α- and β (LXRα and β, Mm00443454_m1 and Mm00437262_m1), fatty acid synthase (FAS, Mm00662319_m1), sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c, Mm01138344_m1), ATP-binding cassette transporter-1 (ABCA-1, Mm00442646_m1), arginase 1 (ARG1, Mm00475988_m1), resistin-like molecule/found in inflammatory zone (retnla, RELM/FIZZ, Mm00445109_m1), inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS2, Mm01309897_m1v) and Ym1/chitinase 3-like 3 (Chi3l3, Mm00657889_mH).

Serum Analysis

Total serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels (mmol/L) were measured by enzymatic assay (Roche Diagnostics). Serum cytokines were analyzed in a 20-plex mouse cytokine assay (Biosource), and metabolic and hormonal patterns were analyzed using the mouse adipocyte kit (Insulin, Resistin, tPAI-1) (Millipore) on the Bio-Plex 100 system (Bio-Rad).

Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS)

Mice underwent whole body MRS on a 7T Bruker Biospec system (Bruker Biospec, Karlsruhe, Germany), using a 15cm diameter proton birdcage radio frequency coil, for both transmitting and receiving at the proton resonance of 300MHz. The large RF coil ensured the B1 field was uniform over the whole mouse, thus giving uniform signal detection. The free induction decay was detected following a 75μs RF pulse, and 4 signal averages taken (Repetition time Tr= 15s, 50kHz sweep width, 8192 point digitization). The resultant signal was then Fourier transformed and phased automatically to give the proton spectra (Paravision 4.0, Bruker, Germany). At 7Tesla the water and lipid resonances of the whole body MRS spectra are well separated allowing the areas under the curve (AUC) to be obtained by simple integration. The AUC of the water peak (AUCH2O) was determined over a 3000Hz range below the relative minimum cutoff, and the AUC of the lipid peak over a 3000Hz range above the relative minimum cutoff. These AUC’s were then used to determine percentages of body fat (%FAT) and fat free mass by MRS (%FFM).

Novelty and Significance section.

What is known?

Chronic low-grade inflammation involving cytokines in adipose tissue may contribute to the metabolic consequences of obesity

What new information does this article contribute?

This is the first report that the new cytokine IL-33 has protective effects in adipose tissue inflammation and obesity

Novelty and Significance

The novel IL-1 family cytokine IL-33 and its receptor ST2 are expressed in adipose tissue but their role in adipose tissue inflammation during obesity is unclear. Here, we show that treatment of genetically obese diabetic (ob/ob) mice with recombinant IL-33 led to reduced adiposity, reduced fasting glucose and improved glucose and insulin tolerance, and induction of protective Th2 cytokines and M2 macrophages in adipose tissue. Furthermore, mice lacking endogenous ST2 have increased body weight and fat mass, impaired insulin secretion and glucose regulation. This is the first report that the cytokine IL-33 has key protective metabolic effects and manipulation of IL-33 expression in adipose tissue may be a useful therapeutic strategy for treating or preventing type 2 diabetes in obese patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank R Spooner for serum measurements; L Gallagher, C McCabe, and J Mullin for MRS analysis; and A Gilmour for cell sorting.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

AM Miller is supported by a BHF Intermediate Basic Science Research Fellowship (FS/08/035/25309). AJ Hueber is supported by a German research foundation (DFG) fellowship. We received financial support from the Medical Research Council UK, the Wellcome Trust and the British Heart Foundation.

Non-standard abbreviations and acronyms

- ABCA-1

ATP-binding cassette transporter-1

- ARG1

Arginase 1

- C/EBP-α

CAAT enhancer–binding protein-α

- FAS

Fatty acid synthase

- FFM

Fat free mass

- HFD

High fat diet

- IL-33

Interleukin-33

- LXR

Liver X receptor

- NOS2

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- ORO

Oil red O

- PCK-1

phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1

- PPAR

Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor

- retnla

resistin-like molecule/found in inflammatory zone

- SREBP-1c

Sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c

- sST2

Soluble ST2

- SVF

Stromal vascular fraction

- TBP

Tata binding protein

- WAT

White adipose tissue

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW., Jr. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1796–1808. doi: 10.1172/JCI19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu H, Ghosh S, Perrard XD, Feng L, Garcia GE, Perrard JL, Sweeney JF, Peterson LE, Chan L, Smith CW, Ballantyne CM. T-cell accumulation and regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted upregulation in adipose tissue in obesity. Circulation. 2007;115:1029–1038. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.638379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kintscher U, Hartge M, Hess K, Foryst-Ludwig A, Clemenz M, Wabitsch M, Fischer-Posovszky P, Barth TF, Dragun D, Skurk T, Hauner H, Bluher M, Unger T, Wolf AM, Knippschild U, Hombach V, Marx N. T-lymphocyte infiltration in visceral adipose tissue: a primary event in adipose tissue inflammation and the development of obesity-mediated insulin resistance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1304–1310. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.165100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lago F, Dieguez C, Gomez-Reino J, Gualillo O. Adipokines as emerging mediators of immune response and inflammation. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2007;3:716–724. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rocha VZ, Folco EJ, Sukhova G, Shimizu K, Gotsman I, Vernon AH, Libby P. Interferon-gamma, a Th1 cytokine, regulates fat inflammation: a role for adaptive immunity in obesity. Circ Res. 2008;103:467–476. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.177105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishimura S, Manabe I, Nagasaki M, Eto K, Yamashita H, Ohsugi M, Otsu M, Hara K, Ueki K, Sugiura S, Yoshimura K, Kadowaki T, Nagai R. CD8+ effector T cells contribute to macrophage recruitment and adipose tissue inflammation in obesity. Nat Med. 2009;15:914–920. doi: 10.1038/nm.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winer S, Chan Y, Paltser G, Truong D, Tsui H, Bahrami J, Dorfman R, Wang Y, Zielenski J, Mastronardi F, Maezawa Y, Drucker DJ, Engleman E, Winer D, Dosch HM. Normalization of obesity-associated insulin resistance through immunotherapy. Nat Med. 2009;15:921–929. doi: 10.1038/nm.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feuerer M, Herrero L, Cipolletta D, Naaz A, Wong J, Nayer A, Lee J, Goldfine AB, Benoist C, Shoelson S, Mathis D. Lean, but not obese, fat is enriched for a unique population of regulatory T cells that affect metabolic parameters. Nat Med. 2009;15:930–939. doi: 10.1038/nm.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lumeng CN, Bodzin JL, Saltiel AR. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:175–184. doi: 10.1172/JCI29881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lagathu C, Yvan-Charvet L, Bastard JP, Maachi M, Quignard-Boulange A, Capeau J, Caron M. Long-term treatment with interleukin-1beta induces insulin resistance in murine and human adipocytes. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2162–2173. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0335-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meier CA, Bobbioni E, Gabay C, Assimacopoulos-Jeannet F, Golay A, Dayer JM. IL-1 receptor antagonist serum levels are increased in human obesity: a possible link to the resistance to leptin? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1184–1188. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.3.8351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moriwaki Y, Yamamoto T, Shibutani Y, Aoki E, Tsutsumi Z, Takahashi S, Okamura H, Koga M, Fukuchi M, Hada T. Elevated levels of interleukin-18 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in serum of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: relationship with diabetic nephropathy. Metabolism. 2003;52:605–608. doi: 10.1053/meta.2003.50096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Netea MG, Joosten LA, Lewis E, Jensen DR, Voshol PJ, Kullberg BJ, Tack CJ, van Krieken H, Kim SH, Stalenhoef AF, van de Loo FA, Verschueren I, Pulawa L, Akira S, Eckel RH, Dinarello CA, van den Berg W, van der Meer JW. Deficiency of interleukin-18 in mice leads to hyperphagia, obesity and insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2006;12:650–656. doi: 10.1038/nm1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larsen CM, Faulenbach M, Vaag A, Volund A, Ehses JA, Seifert B, Mandrup-Poulsen T, Donath MY. Interleukin-1-receptor antagonist in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1517–1526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsen CM, Faulenbach M, Vaag A, Ehses JA, Donath MY, Mandrup-Poulsen T. Sustained Effects of Interleukin-1-Receptor Antagonist Treatment in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2009 doi: 10.2337/dc09-0533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, Song Y, Murphy E, McClanahan TK, Zurawski G, Moshrefi M, Qin J, Li X, Gorman DM, Bazan JF, Kastelein RA. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity. 2005;23:479–490. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chackerian AA, Oldham ER, Murphy EE, Schmitz J, Pflanz S, Kastelein RA. IL-1 receptor accessory protein and ST2 comprise the IL-33 receptor complex. J Immunol. 2007;179:2551–2555. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weinberg EO, Shimpo M, De Keulenaer GW, MacGillivray C, Tominaga S, Solomon SD, Rouleau JL, Lee RT. Expression and regulation of ST2, an interleukin-1 receptor family member, in cardiomyocytes and myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002;106:2961–2966. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000038705.69871.D9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weinberg EO, Shimpo M, Hurwitz S, Tominaga S, Rouleau JL, Lee RT. Identification of serum soluble ST2 receptor as a novel heart failure biomarker. Circulation. 2003;107:721–726. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000047274.66749.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller AM, Xu D, Asquith DL, Denby L, Li Y, Sattar N, Baker AH, McInnes IB, Liew FY. IL-33 reduces the development of atherosclerosis. J Exp Med. 2008;205:339–346. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wood IS, Wang B, Trayhurn P. IL-33, a recently identified interleukin-1 gene family member, is expressed in human adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;384:105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.04.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kharitonenkov A, Shiyanova TL, Koester A, Ford AM, Micanovic R, Galbreath EJ, Sandusky GE, Hammond LJ, Moyers JS, Owens RA, Gromada J, Brozinick JT, Hawkins ED, Wroblewski VJ, Li DS, Mehrbod F, Jaskunas SR, Shanafelt AB. FGF-21 as a novel metabolic regulator. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1627–1635. doi: 10.1172/JCI23606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tenney R, Stansfield K, Pekala PH. Interleukin 11 signaling in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2005;202:160–166. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamagishi S, Nakamura K, Matsui T. Regulation of advanced glycation end product (AGE)-receptor (RAGE) system by PPAR-gamma agonists and its implication in cardiovascular disease. Pharmacol Res. 2009;60:174–178. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wheatcroft SB, Kearney MT. IGF-dependent and IGF-independent actions of IGF-binding protein-1 and -2: implications for metabolic homeostasis. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steppan CM, Bailey ST, Bhat S, Brown EJ, Banerjee RR, Wright CM, Patel HR, Ahima RS, Lazar MA. The hormone resistin links obesity to diabetes. Nature. 2001;409:307–312. doi: 10.1038/35053000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu D, Chan WL, Leung BP, Huang F, Wheeler R, Piedrafita D, Robinson JH, Liew FY. Selective expression of a stable cell surface molecule on type 2 but not type 1 helper T cells. J Exp Med. 1998;187:787–794. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.5.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Odegaard JI, Ricardo-Gonzalez RR, Red Eagle A, Vats D, Morel CR, Goforth MH, Subramanian V, Mukundan L, Ferrante AW, Chawla A. Alternative M2 activation of Kupffer cells by PPARdelta ameliorates obesity-induced insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2008;7:496–507. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moussion C, Ortega N, Girard JP. The IL-1-like cytokine IL-33 is constitutively expressed in the nucleus of endothelial cells and epithelial cells in vivo: a novel ‘alarmin’? PLoS One. 2008;3:e3331. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohno T, Oboki K, Kajiwara N, Morii E, Aozasa K, Flavell RA, Okumura K, Saito H, Nakae S. Caspase-1, caspase-8, and calpain are dispensable for IL-33 release by macrophages. J Immunol. 2009;183:7890–7897. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanada S, Hakuno D, Higgins LJ, Schreiter ER, McKenzie AN, Lee RT. IL-33 and ST2 comprise a critical biomechanically induced and cardioprotective signaling system. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1538–1549. doi: 10.1172/JCI30634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang K, Reilly SM, Karabacak V, Gangl MR, Fitzgerald K, Hatano B, Lee CH. Adipocyte-derived Th2 cytokines and myeloid PPARdelta regulate macrophage polarization and insulin sensitivity. Cell Metab. 2008;7:485–495. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moro K, Yamada T, Tanabe M, Takeuchi T, Ikawa T, Kawamoto H, Furusawa J, Ohtani M, Fujii H, Koyasu S. Innate production of T(H)2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-Kit(+)Sca-1(+) lymphoid cells. Nature. 2010;463:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature08636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bastard JP, Jardel C, Bruckert E, Blondy P, Capeau J, Laville M, Vidal H, Hainque B. Elevated levels of interleukin 6 are reduced in serum and subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese women after weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:3338–3342. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.9.6839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wallenius V, Wallenius K, Ahren B, Rudling M, Carlsten H, Dickson SL, Ohlsson C, Jansson JO. Interleukin-6-deficient mice develop mature-onset obesity. Nat Med. 2002;8:75–79. doi: 10.1038/nm0102-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sultan A, Strodthoff D, Robertson AK, Paulsson-Berne G, Fauconnier J, Parini P, Ryden M, Thierry-Mieg N, Johansson ME, Chibalin AV, Zierath JR, Arner P, Hansson GK. T cell-mediated inflammation in adipose tissue does not cause insulin resistance in hyperlipidemic mice. Circ Res. 2009;104:961–968. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.190280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanda H, Tateya S, Tamori Y, Kotani K, Hiasa K, Kitazawa R, Kitazawa S, Miyachi H, Maeda S, Egashira K, Kasuga M. MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1494–1505. doi: 10.1172/JCI26498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia MC, Wernstedt I, Berndtsson A, Enge M, Bell M, Hultgren O, Horn M, Ahren B, Enerback S, Ohlsson C, Wallenius V, Jansson JO. Mature-onset obesity in interleukin-1 receptor I knockout mice. Diabetes. 2006;55:1205–1213. doi: 10.2337/db05-1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]